1. Introduction

University students face various academic, financial, and social challenges that can negative affect their physical health, academic success, and quality of life [

1]. However, physical activity can be an important ally in improving students' health. The health benefits of physical activity are recognized and consolidated in scientific literature. Physical activity is an important factor in the prevention and control of cardiovascular diseases [

2], type 2 diabetes [

3], obesity [

4] and certain cancers [

5]. Furthermore, physical activity can also produce positive mental health outcomes, including preventing cognitive decline [

6] and reducing depressive symptoms and anxiety levels [

7]. Physical activity also improves muscle strength [

8] and contributes to the prevention of osteoporosis [

9]. However, despite the health benefits of daily physical activity, young Europeans are not physically active enough to benefit their health [

10]. On the other hand, three or more hours per day of sedentary behavior was associated with increased mortality risk, except in the most physically active individuals. In these individuals, an increased risk of mortality was found when they sat for five or more hours a day [

11].

It is possible to verify that previous studies have been concerned with assessing the level of self-reported physical activity of Polish university students [

12] and using accelerometry [

13]. Furthermore, other investigations have focused on analyzing the factors determining physical activity and sedentary behavior in Spanish university students [

14]. It is also possible to verify that other studies aimed at the association between vigorous physical activity and different psychosocial variables of university students [

15]. In the same sense, it is also possible to verify studies that aimed to analyze the role of sports practice in the quality of life of university student-athletes [

16]. In another dimension, other investigations objectively measured sedentary behavior and physical activity levels of university students between 18 and 20 years of age. They verified the relationship between these variables and body mass index [

17]. Despite these important contributions, a limitation of most previous studies is the failure to characterize the specific physical activity behaviors that university students prefer or habitually engage in. Furthermore, to the best of our knowledge, the study of non-sedentary behavior habits of university students also appears to be scarce.

It is important to remember that physical activity and sedentary behavior can be described through many activities carried out in multiple contexts and, potentially, with different determining factors and health outcomes [

18,

19]. In this sense, it is also essential to know population trends when choosing these activities [

20]. Knowing the physical activity behaviors of university students from different from different European countries could be important for developing potential strategies to promote daily physical activity for health. Therefore, this study aims to describe and compare the levels of physical activity, preferences for leisure-time physical activity and, the frequency of non-sedentary behaviors of Portuguese, Italian, and Spanish students attending, respectively, higher education in Portugal, in Italy, and Spain. Based on the evidence in the literature and our experience, the main hypothesis of this study is that higher education students frequently engage in sedentary behavior, despite compliance with international recommendations. In comparisons between countries, we may find some differences, possibly due to different policies and investments in each country.

2. Methods

The most used type of investigation in this area is a cross-sectional study based on epidemiological studies in which factors and effects are observed at the same historical moment [

21]. To minimize possible errors in the analysis and interpretation of the results obtained, we used the quantitative method [

22], which uses statistical techniques to quantify data collection and processing.

2.1. Participants

A non-probabilistic sample of Portuguese, Italian, and Spanish students was selected through a sampling strategy in two phases. The first stage of the sampling process was based on the selection of Portuguese, Spanish, and Italian higher education institutions stratified by the regions of the three countries. The second stage of the sampling strategy was based on the selection of students enrolled in different higher education institutions, according to the different scientific areas of higher education courses. The selection of participants was carried out in successive recruitment phases in order to use the updated lists of students enrolled in the different courses of the three different countries. In this sense, the aim was to recruit students with Portuguese, Spanish, and Italian nationality, aged 18 or over, who attend higher education courses from different scientific areas taught by public higher education institutions, such as universities and polytechnics institutes, from different regions of Portugal, Spain, and Italy.

Table 1.

Sample characteristics regarding to gender, age and degree.

Table 1.

Sample characteristics regarding to gender, age and degree.

| Characteristics |

Total |

Portugal |

Spain |

Italy |

|

N (%) |

1354 (100) |

385 (28) |

571 (43) |

398 (29) |

|

Gender, N (%), (IC95%) |

|

|

|

|

| Female |

815 (60.2) (57.5-62.9) |

227(59) (51.4-61.0) |

409 (71.6) (68.3-75.5) |

189 (47.5) (42.7-52.3) |

| Male |

530 (39.1) (36.5-41.9) |

164 (42.6) (37.9-47.8) |

158 (27.7) (23.8-31.2) |

208 (52.3) (47.5-57.0) |

| Diverse |

9 (0.7) (0.3-1.1) |

4 (1.0) (0.3-2.1) |

4 (0.7) (0.2-1.6) |

1 (0.2) (0-0.8) |

|

Age, range, years (mean±SD, Median) |

17-35 (21.2 ± 2.9; 21.0) |

17-35 (20.9 ± 2.9; 20.0) |

17-35 (20.6 ± 2.9; 20.0) |

19-34 (22.3 ± 2.7; 22.0) |

|

Degree, N (%), (IC95%) |

|

|

|

|

| Bachelor |

1237 (91.4) (89.9-92.8) |

317 (82.3) (78.7-86.0) |

529 (92.6) (90.5-94.9) |

391 (98.2) (97-99.2) |

| Master |

78 (5.8) (4.4-7.0) |

39 (10.1) (7.3-13.0) |

37 (6.5) (4.4-8.6) |

2 (0.5) (0-1.3) |

| Other |

39 (2.9) (2.0-3.8) |

29 (7.5) (5.2-10.1) |

5 (0.9) (0.2-1.8) |

5 (1.3) (0.3-2.5) |

Sub-Elite

Amateur |

39

16 |

25,36 ± 4,83

22,01 ± 3,55 |

72,56 ± 7,99

72,96 ± 15,61 |

1,73 ± 0,05

1,76 ± 0,07 |

Thirteen hundred and fifty-four (1354) Portuguese, Italian, and Spanish students who attended universities in Portugal, Italy, and Spain participated in this study. Of this total, 385 subjects studied in higher education institutions in Portugal (average age 20.9±2.9), 398 studied in higher education institutions in Italy (average age 22.3±2.7), and 571 studied in higher education institutions in Spain (average age 20.6±2.9).

2.2. Instruments

The short version of the International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ) was applied, validated and translated into Italian [

23], Portuguese [

24] and Spanish [

25]. This instrument makes it possible to standardize measures related to health and the assessment of physical activity behaviors of the population, in different countries and in different sociocultural contexts [

20]. The short version of the IPAQ was used because it is a questionnaire that is easier, faster, and more viable to complete in studies involving a large number of participants [

26]. Using the IPAQ scoring protocol, it was possible to estimate total weekly physical activity by evaluating the time spent at each intensity of activity with its estimated metabolic equivalent energy expenditure [

24]. According to the IPAQ results, students can be classified as low active, moderately active, or highly active (

http://www.ipaq.ki.se). Moderately active means individuals achieved at least 600 metabolic equivalent minutes per week. High means that individuals achieved at least 3000 metabolic equivalent minutes per week. Low activity indicates that individuals do not meet the “moderately” or “high” criteria. Participants in the present study also answered whether they regularly engage in physical activities in their free time. If the answer was “Yes,” they listed these activities and the weekly frequency and number of minutes per day they dedicate to carrying out each physical activity mentioned.

2.3. Procedures

Formal and institutional contact was made with Higher Education institutions, presenting the study's objectives and requesting authorization. Before data collection, all subjects were presented with the study in question, its objectives, and the procedures to be followed. An anamnesis form and an informed consent form were sent to each subject to conduct the evaluations, with all ethical principles, international norms, and standards related to the Declaration of Helsinki and the Convention on Human Rights being respected and preserved [

27]. All assessments were carried out by sending questionnaires via email to the subjects. The study was approved by the ethics committee (opinion no. 58 CE-IPCB/2021).

2.4. Statistical Analyses

2.4.1. Preliminary Analysis

An inspection of the data revealed no missing values or univariate outliers. A priori power analysis through G∗Power (3.1.9.7) and one-way ANOVA was used as an alternative for the Kruskal-Wallis test as a non-parametric test [

28] to determine the required sample size considering the following input parameters:(effect size f = 0.25; α err prob = 0.01; statistical power = 0.95). The required sample size was 1008 (336 for each group), which was respected in the present study.

2.4.2. Main Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were performed for all analyzed variables, including mean and standard deviation. Then, a Kolmogorov-Smirnov (n > 50) was performed to analyze data distribution, considering p > 0.05 as a normal distribution [

29]. All data variables analyzed present a non-normal distribution. A Kruskal-Wallis was used to verify differences between groups) Moreover, a post-hoc pairwise comparison for groups that have present statistical differences. Finally, an effect size (Cohen d) analysis was used to determine the magnitude of the effect, and the following cut-off values were considered–0.2, trivial; 0.21–0.6, small; 0.61–1.2, moderate; 1.21–2.0, big; and >2.0, very big [

30]. The effect size was calculated using the eta square value (η2) [

31]. All statistical analysis was performed using SPSS software v. 29.0 (IBM, Chicago, IL, United States), and the significance level was set at p ≤ 0.05 to reject the null hypothesis [

29,

32].

3. Results

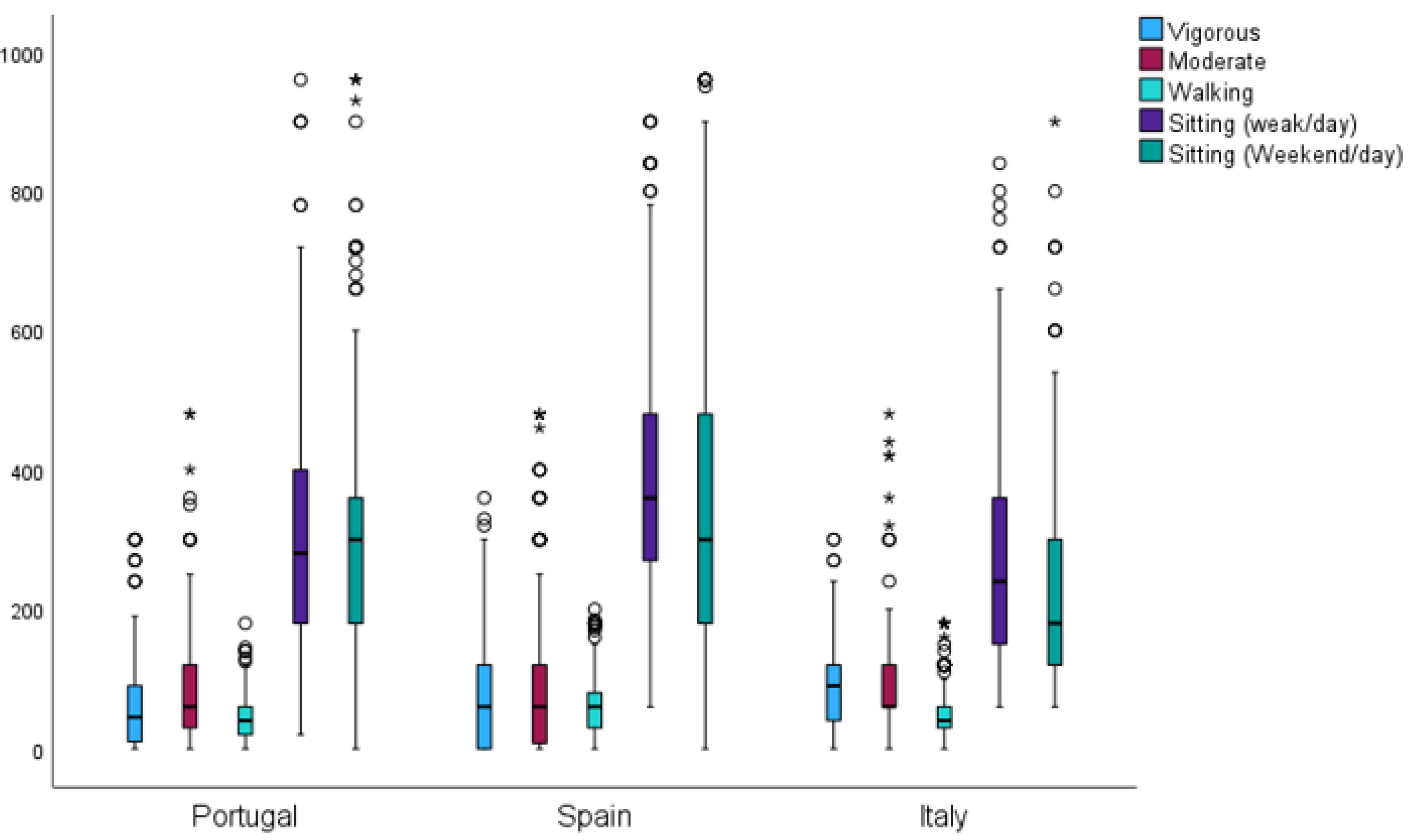

Table 2 shows the differences in the studied variables between the three groups (Portugal, Spain, and Italy) regarding Physical Activity and sedentary time. Differences between groups (p ≤ 0.05) were found in all variables studied.

Regarding post hoc pairwise comparison for groups, differences were found in all variables studied (p ≤ 0.05), except moderate physical activity (p=.525) and vigorous physical activity (p=.075) between Portugal and Spain.

Figure 1 shows variance analyses of the time spent on different behaviors in the three countries studied.

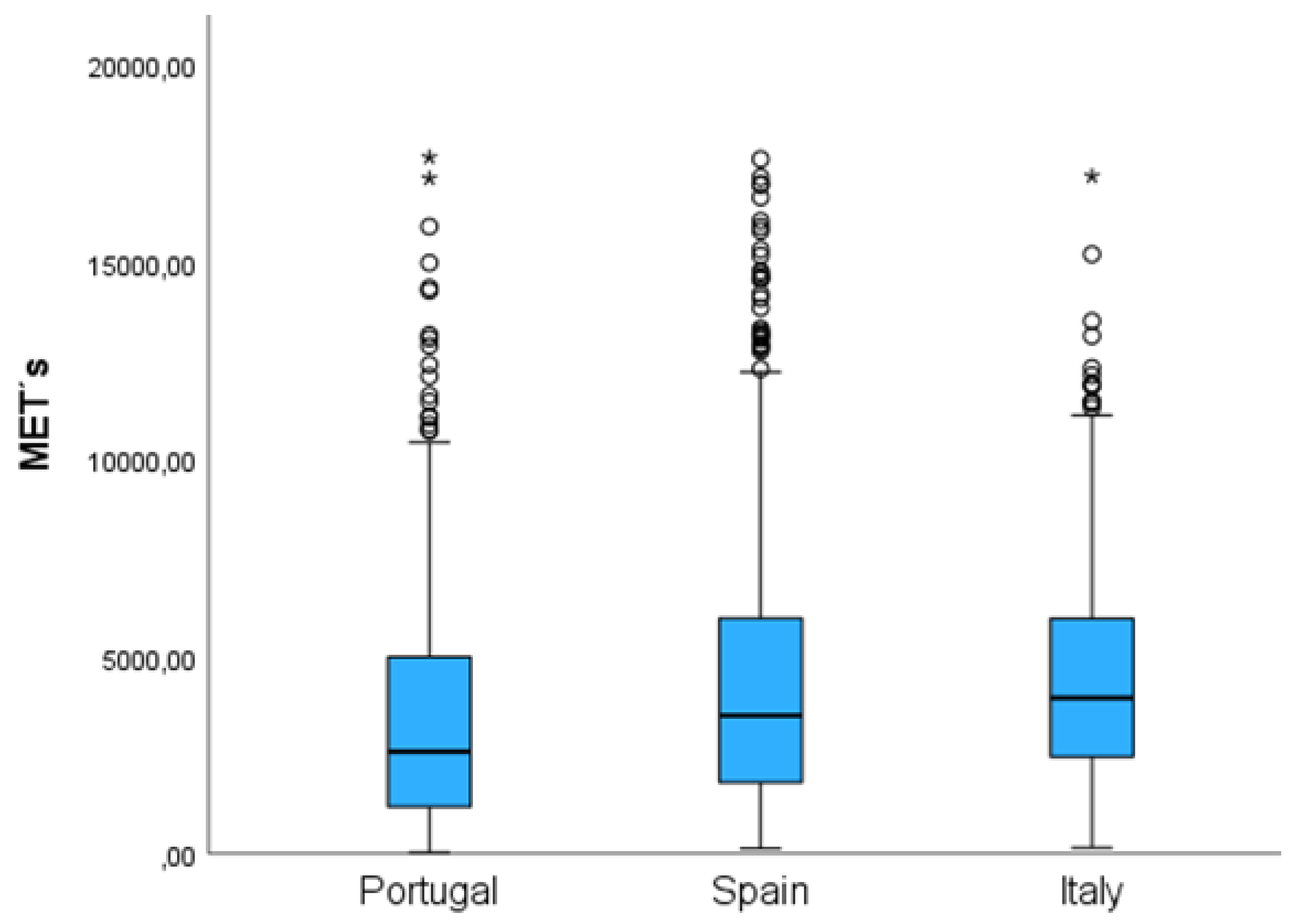

Figure 2 shows the variance analyses related to the Metabolic Equivalent of the Task of which country. We found differences between Portugal and Spain (p<.001, η2=0.021, Effect Size=0.293) and Portugal and Italy (p <.001, η2=0.051, Effect Size=0.461).

4. Discussion

The objective of the present research was to describe and compare the levels of physical activity, preferences for leisure-time physical activity, and frequency of non-sedentary behaviors of Portuguese, Italian, and Spanish students attending higher education in Portugal, Italy, and Spain, respectively.

The findings of the present study show an interaction effect between country and sedentary, with the highest levels of sedentary lifestyles found among Spanish students, followed by the Portuguese and, lastly, the Italians. However, people studying in Portugal spent the most time sitting during one working day compared with Poland and Belarus students [

33]. These data are different to those collected in the Eurobarometer 2022 [

10] in which 40% of Italian citizens claimed to spend at least 330 minutes per day (five and a half hour) doing sedentary activities, 34% in the case of the Spanish and 29% in the case of the Portuguese. These data are quite worrisome since an increased mortality risk was found when they sat for five or more hours a day [

11].

Regarding physical activity levels, Spanish students perform more minutes of low and moderate activity than Italian and Portuguese students. Italians are the ones who perform more vigorous activity. It is also observed that Portuguese people practice the least number of minutes of physical activity at all levels. According to The World Health Organization (WHO), adults do at least 150 min per week of moderate-intensity aerobic physical activity, or at least 75 min of vigorous-intensity aerobic physical activity throughout the week, or an equivalent combination of moderate and vigorous-intensity activities [

34].

According to Burton et al. [

35] university students typically report low levels of physical activity due, among other factors, to a greater demand on time for study. A study conducted in Spain with 3. 060 university students concluded that more than 60% of the students did not meet the minimum levels of physical activity recommended by the WHO [

36] in other study only 58% of Spanish students reached the recommendations established by the WHO [

37]. Another research conducted in Poland, Portugal and Belarus with a total of 1.136 university students showed that the dominant level of activity was at a vigorous physical activity level, 58.5% of the surveyed men and 46.2% of the surveyed women [

33]. However, the results show a higher compliance with WHO recommendations compared to the results obtained in a recent systematic review with meta-analysis carried out in 32 countries, where the percentage of adherence to these international recommendations is 17.12% in adults (which is the population sector in which university students are found) and 19.74% in adolescents [

38].

In this line of research, the study conducted by Dabrowska-Galas et al. [

12] with a total of 300 university students found that 98% of the physical therapist students claimed that they were physically active before starting university. In the same way, an insufficient level was recorded among 12.6% of male university students and 16.7% of female university students from Poland, Portugal and Belarus [

33].

We present, as suggestions for future investigations, the possibility of using less subjective instruments, which can provide more objective data and lead to more specific conclusions. In addition to the indicators assessed, eating habits and some body composition indicators can also be assessed to complement these analyses. Also, see the possibility of involving more countries in comparative studies of this nature.

Regarding the practical implications of this study, we consider it to be another modest contribution to demonstrating the evidence pointing to the sense that the young adult population (higher education students) presents worryingly low values of physical activity and worryingly high values concerning sedentary behaviors. This could be another contribution so that public policies can direct greater attention and investment to this problem, which is emerging, as well as universities being able to rethink their internal organization around enabling their students to spend more time dedicated to active behaviors and minimize sedentary behaviors, both in teaching activities and in other academic activities. The promotion of physical-sports activities that help to increase the weekly physical activity time, even if at the beginning it still does not reach the minimum required, can be a good start and, undoubtedly, much better than the scarce physical activity shown in the results.

5. Conclusions

Spanish students engage in more low and moderate intensity exercise, while Italian students spend more time in vigorous physical activity. All three populations meet the WHO's minimum recommended activity levels. The study finds that Spanish students are the most sedentary, followed by Portuguese and then Italian students. Analysis between weekdays and weekends shows Italian students are consistently the least sedentary. High sedentary behavior is likely linked to the nature of university life, involving extensive sitting for lectures and study. It is crucial for universities to create opportunities for students to increase physical activity, countering sedentary time and promoting long-term healthy lifestyles.

Author Contributions

R.P. worked on Conceptualization, Formal Analysis, Methodology, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. A.R. worked on Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal Analysis, Methodology, Supervision, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. I.S. worked on Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. M.C. worked on Conceptualization, Formal Analysis, Supervision, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. N.B. worked on Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal Analysis, Methodology, Supervision, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. D.B-G worked on Conceptualization, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Methodology. M.E. worked on writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. M.R. worked on Project administration, Resources, Writing – review & editing. P.D-M. worked on Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of Instituto Politécnico de Castelo Branco (opinion no. 58 CE-IPCB/2021).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are only available upon request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy issues.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Bruffaerts, R.; Mortier, P.; Kiekens, G.; Auerbach, R.P.; Cuijpers, P.; Demyttenaere, K.; Green, J.G.; Nock, M.K.; Kessler, R.C. Mental Health Problems in College Freshmen: Prevalence and Academic Functioning. J Affect Disord 2018, 225, 97–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Myers, J.; Kokkinos, P.; Nyelin, E. Physical Activity, Cardiorespiratory Fitness, and the Metabolic Syndrome. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rhodes, R.E.; Janssen, I.; Bredin, S.S.D.; Warburton, D.E.R.; Bauman, A. Physical Activity: Health Impact, Prevalence, Correlates and Interventions. Psychol Health 2017, 32, 942–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jakicic, J.M.; Davis, K.K. Obesity and Physical Activity. Psychiatric Clinics of North America 2011, 34, 829–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mctiernan, A.; Fridenreich, C.M.; Katzmarkzyk, P.T.; Powell, K.E.; Macko, R.; Buchner, D.; Pescatello, L.S.; Bloodgood, B.; Tennant, B.; Vaux-bjerke, A.; George, S.M.; Troiano, R.P.; Piercy, K.L. Physical Activity in Cancer Prevention and Survival: A Systematic Review. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2019, 51, 1252–1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guure, C.B.; Ibrahim, N.A.; Adam, M.B.; Said, S.M. Impact of Physical Activity on Cognitive Decline, Dementia, and Its Subtypes: Meta-Analysis of Prospective Studies. Biomed Res Int 2017, 2017, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, R.L.; Babic, M.J.; Parker, P.D.; Lubans, D.R.; Astell-Burt, T.; Lonsdale, C. Domain-Specific Physical Activity and Mental Health: A Meta-Analysis. Am J Prev Med 2017, 52, 653–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leblanc, A.; Taylor, B.A.; Thompson, P.D.; Capizzi, J.A.; Clarkson, P.M.; Michael White, C.; Pescatello, L.S. Relationships between Physical Activity and Muscular Strength among Healthy Adults across the Lifespan. Springerplus 2015, 4, 557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ocarino, N.M.; Marubayashi, U.; Cardoso, T.G.S.; Guimarães, C.V.; Silva, A.E.; Tôrres, R.C.S.; Serakides, R. Physical Activity in Osteopenia Treatment Improved the Mass of Bones Directly and Indirectly Submitted to Mechanical Impact. J Musculoskelet Neuronal Interact 2007, 7, 84–93. [Google Scholar]

- Commission, E. Special Eurobarometer 472: Sport and Physical Activity. https://sport.ec.europa.eu/sites/default/files/special-eurobarometer-472_en.pdf (accessed 2024-05-08).

- Ekelund, U.; Steene-Johannessen, J.; Brown, W.J.; Fagerland, M.W.; Owen, N.; Powell, K.E.; Bauman, A.; Lee, I.-M. Does Physical Activity Attenuate, or Even Eliminate, the Detrimental Association of Sitting Time with Mortality? A Harmonised Meta-Analysis of Data from More than 1 Million Men and Women. The Lancet 2016, 388, 1302–1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dąbrowska-Galas, M.; Plinta, R.; Dąbrowska, J.; Skrzypulec-Plinta, V. Physical Activity in Students of the Medical University of Silesia in Poland. Phys Ther 2013, 93, 384–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Downs, A.; Van Hoomissen, J.; Lafrenz, A.; Julka, D.L. Accelerometer-Measured Versus Self-Reported Physical Activity in College Students: Implications for Research and Practice. Journal of American College Health 2014, 62, 204–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carballo-Fazanes, A.; Rico-Díaz, J.; Barcala-Furelos, R.; Rey, E.; Rodríguez-Fernández, J.E.; Varela-Casal, C.; Abelairas-Gómez, C. Physical Activity Habits and Determinants, Sedentary Behaviour and Lifestyle in University Students. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020, 17, 3272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- VanKim, N.A.; Nelson, T.F. Vigorous Physical Activity, Mental Health, Perceived Stress, and Socializing among College Students. American Journal of Health Promotion 2013, 28, 7–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Snedden, T.R.; Scerpella, J.; Kliethermes, S.A.; Norman, R.S.; Blyholder, L.; Sanfilippo, J.; McGuine, T.A.; Heiderscheit, B. Sport and Physical Activity Level Impacts Health-Related Quality of Life Among Collegiate Students. American Journal of Health Promotion 2019, 33, 675–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, N.E.; Sirard, J.R.; Kulbok, P.A.; DeBoer, M.D.; Erickson, J.M. Sedentary Behavior and Physical Activity of Young Adult University Students. Res Nurs Health 2018, 41, 30–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sallis, J.F.; Cervero, R.B.; Ascher, W.; Henderson, K.A.; Kraft, M.K.; Kerr, J. An Ecological Approach to Creating Active Living Communities. Annu Rev Public Health 2006, 27, 297–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owen, N.; Sugiyama, T.; Eakin, E.E.; Gardiner, P.A.; Tremblay, M.S.; Sallis, J.F. Adults’ Sedentary Behavior. Am J Prev Med 2011, 41, 189–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, P.J.; Marques, A.; Lopes, C.; Sardinha, L.B.; Mota, J.A. Prevalence and Preferences of Self-Reported Physical Activity and Nonsedentary Behaviors in Portuguese Adults. J Phys Act Health 2019, 16, 251–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rouquayrol, Z. Epidemiologia & Saúde; Medsi Editora Médica e Científica Ltda, Ed.; Rio de Janeiro, 1994.

- Diehl, A.A.; Tatim, D.C. Pesquisa Em Ciências Sociais Aplicadas: Métodos e Técnicas.; Prentice Hall, Ed.; São Paulo, 2004.

- Mannocci, A.; Thiene, D.D.; Cimmuto, A.D.; Masala, D.; Vito, E.; Torre, G. International Physical Activity Questionnaire: Validation and Assessment in an Italian Sample. Italian Journal of Public Health 2010, 7, 369–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craig, C.L.; Marshall, A.L.; Sjöström, M.; Bauman, A.E.; Booth, M.L.; Aainsworth, B.E.; Pratt, M.; Ekelund, U.; Yngve, A.; Sallis, J.F.; Oja, P. International Physical Activity Questionnaire: 12-Country Reliability and Validity. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2003, 35, 1381–1395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Román Viñas, B.; Ribas Barba, L.; Ngo, J.; Serra Majem, L. Validación En Población Catalana Del Cuestionario Internacional de Actividad Física. Gac Sanit 2013, 27, 254–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bauman, A.; Bull, F.; Chey, T.; Craig, C.L.; Ainsworth, B.E.; Sallis, J.F.; Bowles, H.R.; Hagstromer, M.; Sjostrom, M.; Pratt, M.; Group, I. The International Prevalence Study on Physical Activity: Results from 20 Countries. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity 2009, 6, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki. JAMA 2013, 310, 2191. [CrossRef]

- Faul, F.; Erdfelder, E.; Lang, A.-G.; Buchner, A. G*Power 3: A Flexible Statistical Power Analysis Program for the Social, Behavioral, and Biomedical Sciences. Behav Res Methods 2007, 39, 175–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.; Babin, B.; Anderson, R.; Black, W. Multivariate Data Analysis, 8th ed.; 2019.

- Hopkins, W.G.; Marshall, S.W.; Batterham, A.M.; Hanin, J. Progressive Statistics for Studies in Sports Medicine and Exercise Science. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2009, 41, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenhard, W.; Lenhard, A. Computation of Effect Sizes.

- Ho, R. Handbook of Univariate and Multivariate Data Analysis with IBM SPSS, 2nd Edition.; Chapman and Hall/CRC, 2013. [CrossRef]

- Król, M.; Latosiewicz, R.; Marques Brás, R.; Barkow, W.; Zuzda, J. Level of Physical Activity of Students in Poland, Portugal and Belarus. Annals of Agricultural and Environmental Medicine 2022, 29, 126–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bull, F.C.; Al-Ansari, S.S.; Biddle, S.; Borodulin, K.; Buman, M.P.; Cardon, G.; Carty, C.; Chaput, J.-P.; Chastin, S.; Chou, R.; Dempsey, P.C.; DiPietro, L.; Ekelund, U.; Firth, J.; Friedenreich, C.M.; Garcia, L.; Gichu, M.; Jago, R.; Katzmarzyk, P.T.; Lambert, E.; Leitzmann, M.; Milton, K.; Ortega, F.B.; Ranasinghe, C.; Stamatakis, E.; Tiedemann, A.; Troiano, R.P.; van der Ploeg, H.P.; Wari, V.; Willumsen, J.F. World Health Organization 2020 Guidelines on Physical Activity and Sedentary Behaviour. Br J Sports Med 2020, 54, 1451–1462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burton, N.W.; Barber, B.L.; Khan, A. A Qualitative Study of Barriers and Enablers of Physical Activity among Female Emirati University Students. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2021, 18, 3380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espada, M.; Romero-Parra, N.; Bores-García, D.; Delfa-De La Morena, J.M. Gender Differences in University Students’ Levels of Physical Activity and Motivations to Engage in Physical Activity. Educ Sci (Basel) 2023, 13, 340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sevil Serrano, J.; Práxedes Pizarro, A.; Zaragoza Casterad, J.; Del Villar Álvarez, F.; García-González, L. Barreras Percibidas Para La Práctica de Actividad Física En Estudiantes Universitarios. Diferencias Por Género y Niveles de Actividad Física. Universitas Psychologica 2017, 16, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Hermoso, A.; López-Gil, J.F.; Ramírez-Vélez, R.; Alonso-Martínez, A.M.; Izquierdo, M.; Ezzatvar, Y. Adherence to Aerobic and Muscle-Strengthening Activities Guidelines: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of 3.3 Million Participants across 32 Countries. Br J Sports Med 2023, 57, 225–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).