2. Material and Methods

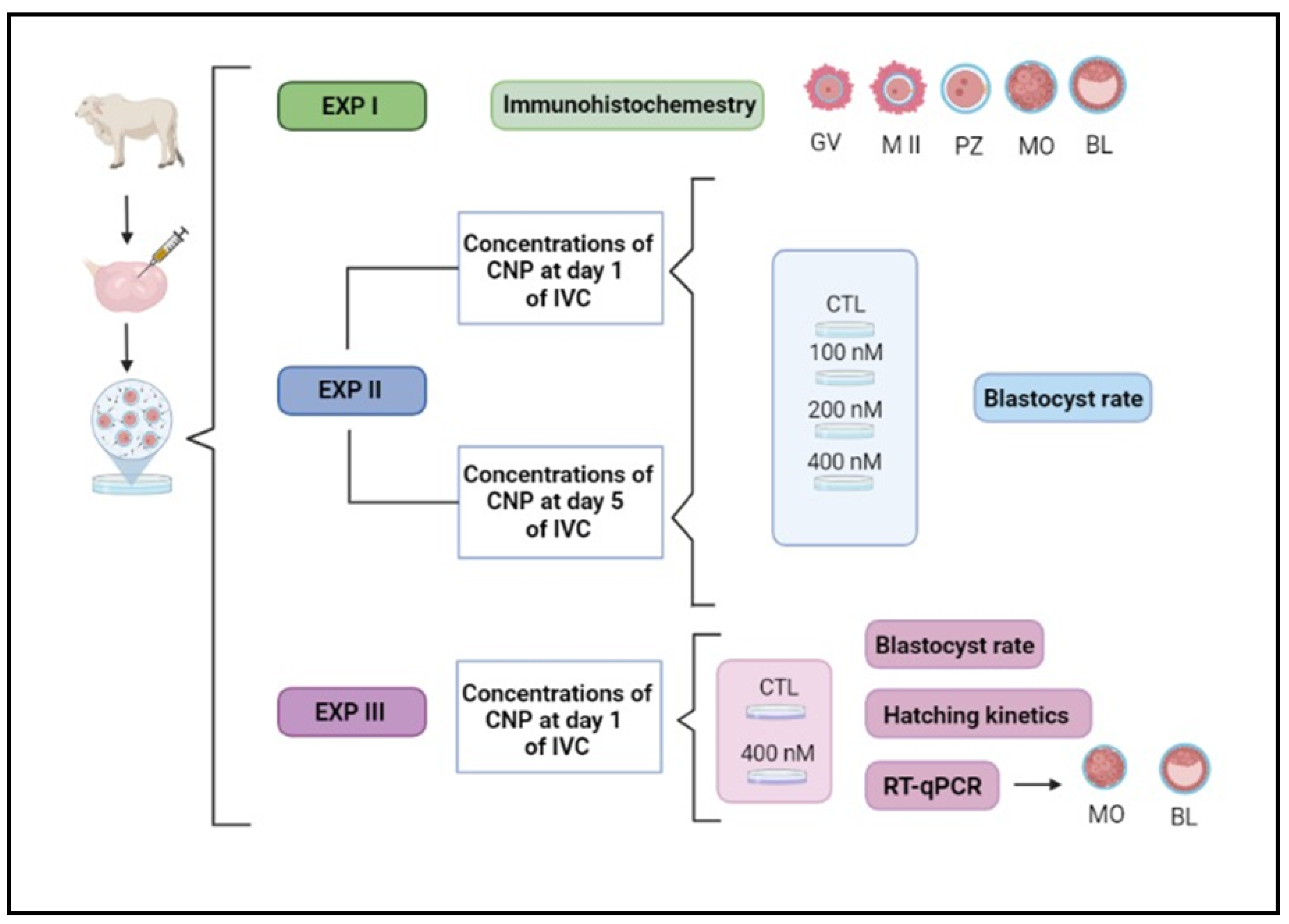

All animal procedures were approved by the Ethics and Animal Handling Committee of the São Paulo State University (UNESP), Botucatu, São Paulo, Brazil, certificate #1180. The experimental design performed in our study is illustrated below (

Figure 1).

2.1. In Vitro Production of Embryos

Ovaries from a commercial slaughterhouse, from bovine females with a predominantly

Bos taurus indicus phenotype of the Nellore breed were collected, packaged, and transported to the laboratory in 0.9% saline solution between 30 and 35ºC. Follicles with a diameter of 2–8 mm were aspirated with hypodermic needles (30x8; 21G) attached to 10 mL syringes for the recovery of

cumulus-oocyte complexes (COCs), with a maximum interval - between the arrival of the ovaries from the slaughterhouse and the end of aspiration – of four hours. Only COCs of qualities I and II were used, and the classification was performed conforming previous studies [

10,

11].

2.2. In Vitro Maturation

Previously to in vitro maturation (IVM), COCs were washed three times in TCM-HEPES 199 supplemented with 10% (v/v) fetal bovine serum, (FBS), 0.20 nM sodium pyruvate and 83.4 mg /mL of gentamicin (ABS Global Brasil®, Mogi Mirim, São Paulo, Brazil). The COCs were matured in drops of 100 mL of TCM-199 medium bicarbonate supplemented with 10% (v/v) fetal bovine serum (FBS), and 50 μg of gentamycin/mL (ABS Global Brasil®, Mogi Mirim, São Paulo, Brazil) and incubated for 24 h in an environment with maximum humidity, 38.5°C and 20% O2.

2.3. In Vitro Fertilization

Finishing the previous step, the COCs were washed in HEPES-buffered TCM-199 medium and transferred to 100 mL droplets of the fertilization medium that consisted of Tris-buffered medium (TBM) supplemented with 8 mg/mL fatty acid-free bovine serum albumin (BSA) and 1 mM glutamine (ABS Global Brasil®, Mogi Mirim, São Paulo, Brazil). For fertilization in drops of 100 µL, semen from a single Nellore bull was used (Adamo Fiv Kubera; Code 011NE03127, register ACF 3522, Alta Genetics), which was previously validated. The cryopreserved semen was heated at 36°C for 30 seconds. Sperm selection was performed by Percoll gradient (ABS Global Brasil®; Percoll 45% in the upper part and 90% in the lower) by centrifugation (12,100 g, for 5 minutes), the supernatant (600 µL) was discarded, and the sperm pellet resuspended in 300 µL of fertilization medium and homogenized. The semen was centrifuged again (8,127 g, for 2 minutes) and, after discarding the supernatant, the sperm concentration was adjusted to obtain a final concentration of 1x106 motile spermatozoa in each drop containing 20 COCs. They were co-incubated for 20 to 22 hours in an environment with maximum humidity, 20% O2, and 38.5° C. The day of insemination was considered day zero (D0).

2.4. In Vitro Culture

For in vitro culture, presumptive zygotes were subjected to the removal of cumulus cells by successive pipetting and then incubated in SOF (Synthetic Oviduct Fluid) medium supplemented with 8 mg/mL fatty acid-free BSA (ABS Global Brasil®, Mogi Mirim, São Paulo, Brazil) under mineral oil under the same temperature and gaseous atmospheric condition used in the previous steps. On the first day of culture (D1) or four days later (D5) the structures were divided into experimental groups: control (without the addition of CNP) and CNP groups (C-type natriuretic peptide, Sigma–Aldrich /St. Louis, MO, United States). On D3, 50% of the culture media volume was replaced by fresh media (1st feeding) and the same occurred on D5 (50% of the culture media volume was replaced with fresh SOF medium supplemented with glucose; 2nd feeding). During culture, blastocyst (D7) and hatching (D7, D8 and D9) rates were evaluated.

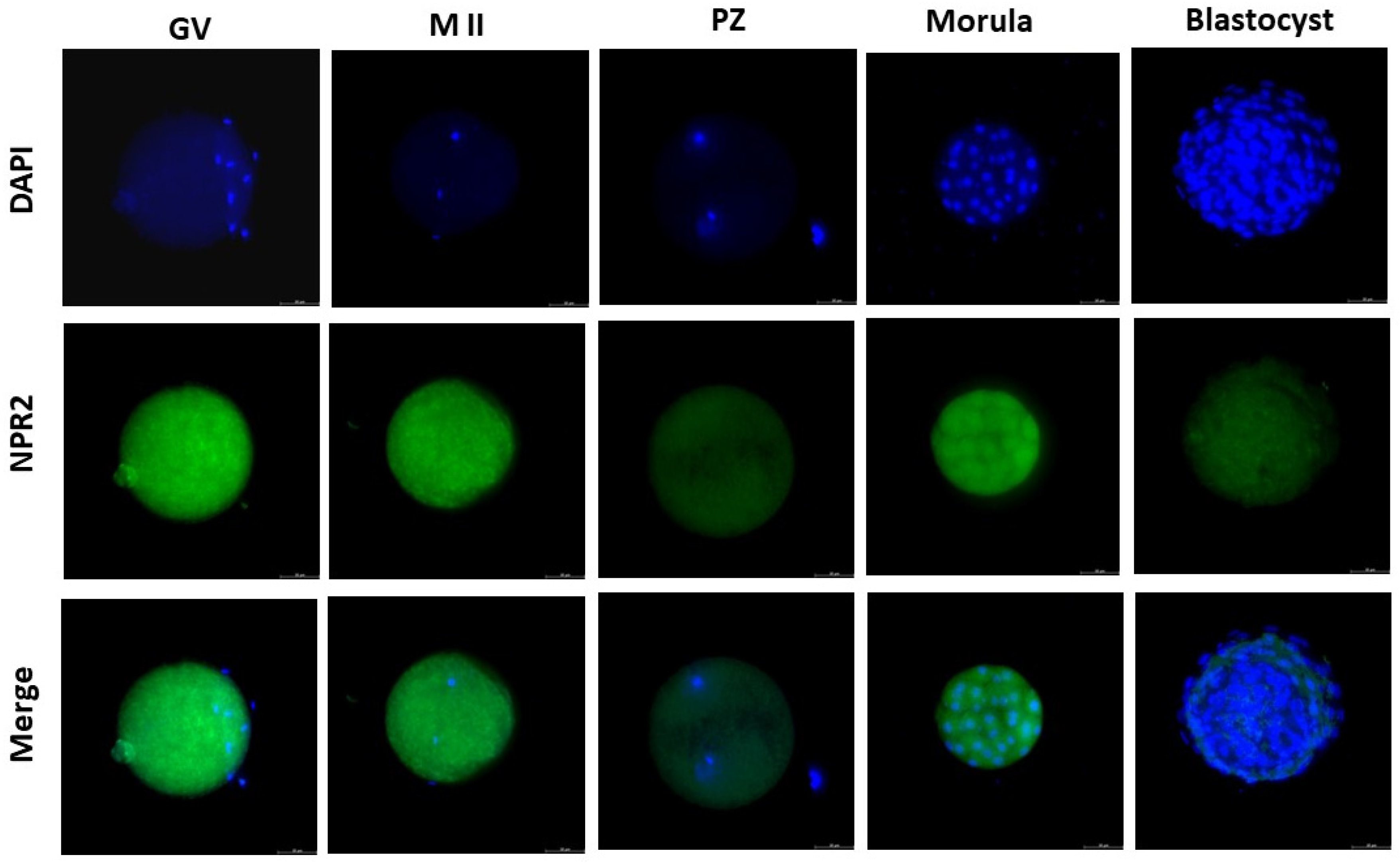

2.5. Experiment I – Detection and Quantification of CNP Receptor

The presence of the CNP receptor (NPR2) in germinal vesicle (GV) and metaphase II (MII) stages oocytes, presumptive zygote (PZ), morula (MO), and blastocyst (BL) was evaluated by immunocytochemistry. For this, the collected oocytes and embryos (N=10 cell/stage) were washed three times with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) and fixed immediately in 4% paraformaldehyde for 20 min. After fixation, the oocytes and embryos were incubated with the primary antibody against NPR2 (HPA011977 Sigma-Aldrich; [

6]) diluted 1:100 overnight at 4 °C. Subsequently, oocytes and embryos were washed with PBS, incubated with anti-rabbit secondary antibody (Invitrogen) diluted 1:200 for 1 h at 37 °C and nuclei were stained with 4ʹ, 6-diamidino- 2-phenylindole (DAPI; Sigma-Aldrich) for 5 min. The fluorescent signals were examined using a Leica fluorescence optical microscope (Leica – THUNDER) and analyzed by densitometric analysis using ImageJ (Version 1.53). The intensity of DAPI and NPR2 is presented as the mean of the fluorescence intensity in arbitrary units.

2.6. Experiment II – Dose-Response with Different CNP Concentrations and CNP Activity Moment Effects on the Embryo Production Rate

Initially, two experiments were carried out to test some concentrations (groups control group and with 100, 200 and 400 nM of CNP) on the embryotoxicity; and, to test the inclusion of CNP in the IVC, at the beginning of culture (D1) or on D5 of IVC. The blastocyst rate of the treated groups was compared to the control and a statistical decrease on the rate would be a indicative of morphological embryotoxicity whereas a complete blockage of blastocyst production should be considerate a lethal CNP concentration [

12,

13].

2.7. Experiment III – Blastocyst Rate and Abundance of Target Transcripts in Embryos Produced under CNP Co-Culture

After obtained data from Experiment II, the highest concentration used (400 nM) was not morphologically embryotoxic. Therefore, we used this concentration of CNP from the first day of the IVC (D1) and evaluated the impact on blastocyst production and hatching rate. Furthermore, we evaluated the abundance of transcripts concerning competence and quality (apoptosis, oxidative stress, proliferation and differentiation) and lipid metabolism in morula (D5) and hatched blastocyst (D7 and D8) from the control group (without CNP) and the group treated with 400 nM CNP.

2.8. Reverse Transcription and Quantitative Polymerase Chain Reaction (RT-qPCR)

2.8.1. RNA Isolation and Reverse Transcription

Total RNA from morula (5 morulas/group in 4 replicates) and hatched blastocysts (3 embryos/group in 4 replicates) was extracted using the PicoPure RNA Isolation kit (Life Technologies, Foster City, CA, United States) following the manufacturer’s protocol. Extracted RNA was stored at -80°C until further analysis by qPCR. RNA concentration was quantified using a spectrophotometer (Nanodrop, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, United States). cDNA synthesis was performed using a High-Capacity Reverse Transcription kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, United States), following the manufacturer’s instructions. All samples were treated with DNase according to the manufacturer’s instructions before reverse transcription.

2.8.2. Pre-Amplification and qPCR

Gene expression analyses of bovine morulas and blastocysts were performed independently using Applied Biosystems

TM TaqMan

©R Assays specific for

B. taurus and based on Fontes et al. [

14]. We analyzed the abundance of 52 transcripts using a panel of genes formatted to investigate embryonic competence and quality (apoptosis, oxidative stress, proliferation, and differentiation) and lipid metabolism in a microfluidic platform (

Supplementary Table S1 describing all the genes and their signaling pathways). Before qPCR thermal cycling, each sample was subjected to a sequence-specific preamplification process as follows: 1.25 mL assay mix (TaqMan

©R Assay was pooled to a final concentration of 0.2× for each of the 52 assays), 2.5 mL TaqMan PreAmp Master Mix (Applied Biosystems, #4391128), and 1.25 mL cDNA (5 ng/mL). The reactions were activated at 95°C for 10 min, followed by denaturation at 95°C for 15 s, annealing, and amplification at 0°C for 4 min for 14 cycles. These preamplified products were diluted fivefold (morula and blastocysts) prior to qPCR analysis. Assays and preamplified samples were transferred to an integrated fluidic circuit plate. For gene expression analysis, the sample solution preparation consisted of 2.25 mL cDNA (preamplified products), 2.5 mL of TaqMan Universal PCR Master Mix (2×, Applied Biosystems), and 0.25 mL of 20× GE Sample Loading Reagent (Fluidigm, South San Francisco, CA, United States); the assay solution included 2.5 mL 20× TaqMan Gene Expression Assay (Applied Biosystems) and 2.5 mL of 2× Assay Loading Reagent (Fluidigm). The 96.96 Dynamic Array

TM Integrated Fluidic Circuits (Fluidigm) chip was used for data collection. After priming, the chip was loaded with 5 mL each of the assay solutions and each sample solution and loaded into an automated controller that prepares the nanoliter-scale reactions. The qPCR thermal cycling was performed in the Biomark HD System (Fluidigm), which involved one stage of Thermal Mix (50°C for 2 min, 70°C for 20 min, and 25°C for 10 min) followed by a hot start stage (50°C for 2 min and 95°C for 10 min), 40 cycles of denaturation (95°C for 15 s), primer annealing, and extension (both at 60°C for 60 s).

2.9. Statistical Analysis

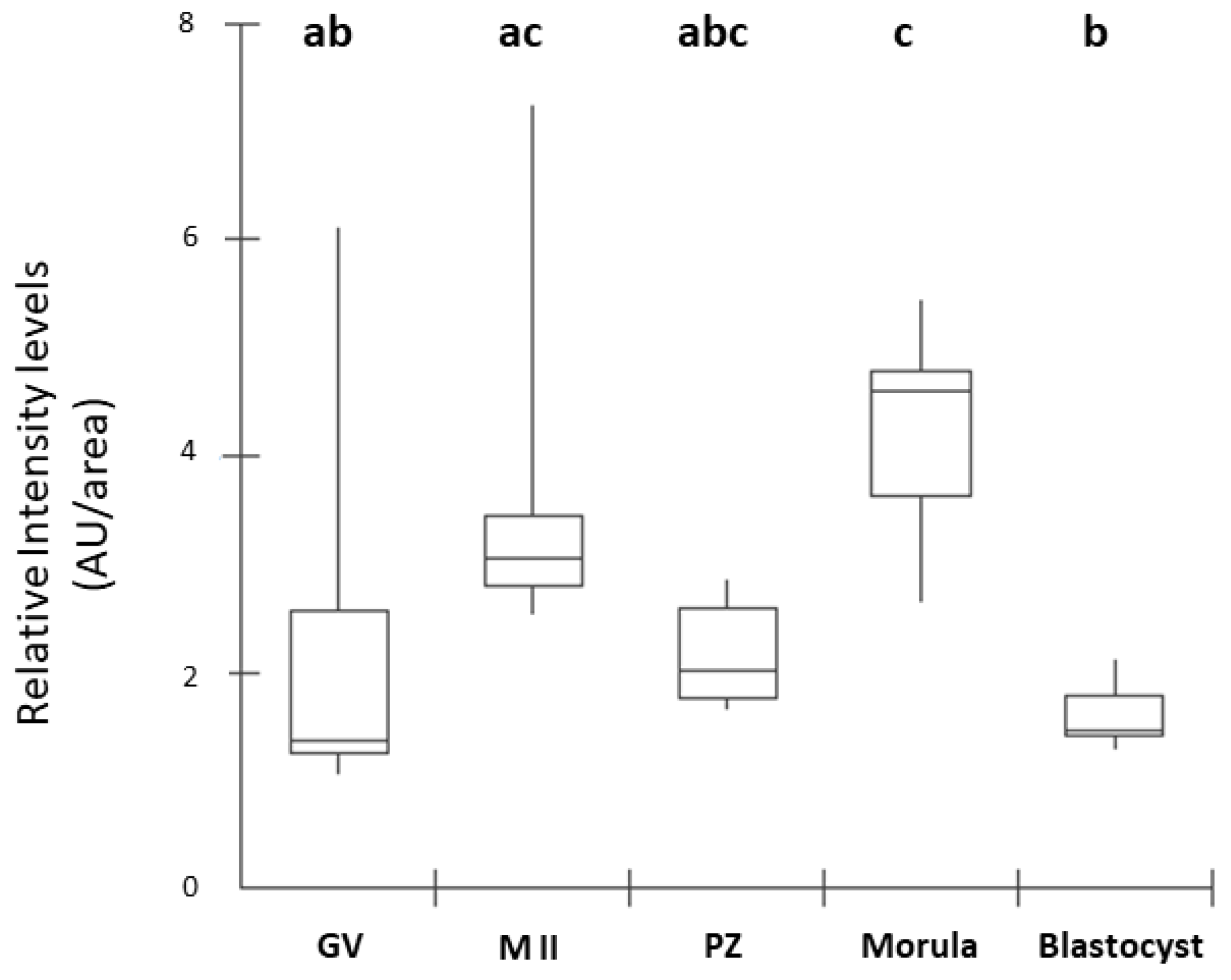

To estimate the fluorescence intensity (Experiment I), the results were evaluated regarding the data distribution, being non-parametric data, thus the Kruskal-Wallis test was used followed by the

post hoc Dunn test. The blastocyst rate was evaluated and the hatching kinetic were tested for normal distribution. Data normality was assessed using the Shapiro-Wilk tests. If the data had a normal distribution, Tukey’s test or one-way ANOVA was applied. If they were non-parametric, data transformation (Log10) was applied or the non-parametric Mann-Whitney test was applied. Data are presented as mean values and standard error of the mean (SEM) or median, 1sd, and 3rd interquartiles. In Experiment II, five replicates/group were performed and Experiment III was performed with eight replicates/group (for blastocyst rate). All of the above analyzes were performed with SigmaStat 4.0 software. Moderate statistical significance (

i.e., an indicative of biological effect) was determined based on 0.01 < P-value ≤ 0.08, while strong significance was considered when P-value ≤ 0.01. Quantitative PCR data were assessed using the ∆Cq values relative to the geometric mean of the best reference genes among the 52-gene set,

i.e.,

GAPDH, and

ACTB. Fold-changes (FC) were calculated using the 2

−∆Cq method [

15]. All analyses were performed using SigmaStat 4.0 and MetaboAnalyst 6.0. The evaluation of the transcripts was initially performed with the univariate statistical analysis method, using FC, T-test. In a second moment, we analyzed the data by multivariate methods, considering a non-supervised cluster analysis heatmap using the Euclidian/average linkage algorithm, Principal Component Analysis (PCA) and Partial Least Squares- Discriminant Analysis (PLS-DA) and their variations. Differences with probabilities less than

P < 0.05, and/or FC ˃1.5 were considered significant.

4. Discussion

To our knowledge, this study is the first to detect and quantify the NPR2 (CNP receptor) in bovine pre-implantation embryos. Our results supported the hypothesis that the use of CNP in the culture of bovine embryos would alter the embryonic metabolism - sustained by data from our group that observed changed transcript abundance in embryos submitted to 100 nM of CNP from day 5 of the IVC [

7].

In addition, the use of 400 nM of CNP in IVC, although no strong statistical difference in production rate was observed, showed more promising results in blastocyst production when compared to the control (46.1 ± 7.8 vs. 32.8 ± 14.2, respectively;

Table 1). Moreover, changes in the abundance of some transcripts related to lipid metabolism, embryonic development, and oxidative stress, were observed in morula and blastocyst treated with CNP, reinforcing that that molecule possess an active effect on the in vitro culture.

NPR2, when activated by CNP binding, triggers a guanylyl cyclase domain, which generates cGMP. This process causes the elevation of cGMP and transferred through gap junctions from

cumulus cells to oocytes, induces an inhibitory action on phosphodiesterase 3A (PDE3A), maintaining high cAMP concentrations in oocytes, and blocking meiosis resumption [

16]. In our study, the presence of NPR2 was observed in all stages of embryonic development analyzed. The detection of NPR2 in oocytes (GV and MII stages) and presumptive zygotes was similarly expressed and quantified. In blastocysts, there was a pronounced decrease in the number of receptors compared to the morula, as equally described by Xi et al. [

6] in mouse embryos. In cattle, the presence of NPR2 was observed in oocytes at the germinal vesicle stage in the membrane and, after the resumption of meiosis, there was a decrease in receptor detection in matured oocytes in metaphase II [

8]. Thus, our results corroborate those findings by Xi et al. [

6] in mice.

Exogenous CNP utilization in pre-IVM and IVM has been a routine for years, with different concentrations and in several species: 100 nM in cattle [

3,

5,

17] 100 nM, 500 nM in murine [

6,

18], 100 nM in cats [

19], 150 ng/mL in goats [

20]. However, the relationship between CNP and the embryo has few reports in the literature [

5,

6,

7]. Most importantly, when looking for its use in the in vitro culture (IVC) step, there is only one study with bovine species [

7].

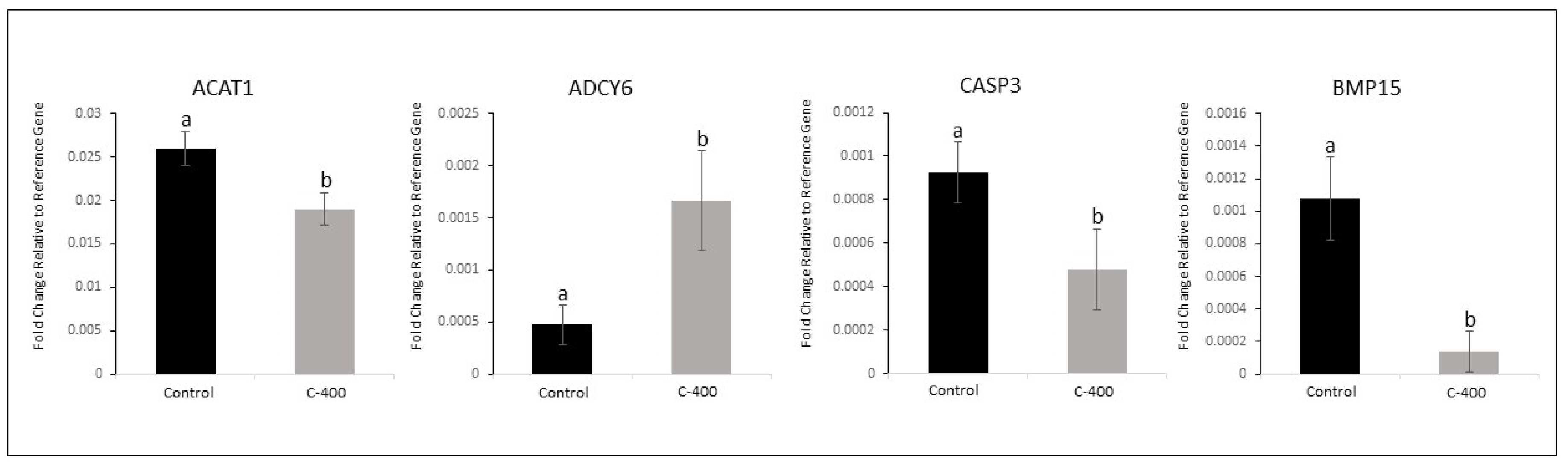

In this context, we supported the hypothesis that the use of CNP in the culture of bovine embryos would alter embryonic metabolism. It was possible to observe changes in the abundance of some transcripts related to lipid metabolism, embryonic development and oxidative processes stress, in morula and blastocysts treated with CNP. These results support and corroborate the study previously published by our group, which observed changes in the abundance of transcripts in embryos subjected to 100 nM CNP from day 5 of IVC [

7]. Moreover, in morula, the Adenylyl cyclase type 6 –

ADCY6 (

P=0.057) gene was upregulated, and the Bone morphogenic protein 15

BMP15 (

P= 0.013), Acetyl-CoA acetyltransferase 1 -

ACAT1 (

P= 0.040), and Caspase 3 -

CASP3 (

P=0.082) genes were downregulated. Further, a total of 12 transcriptions in morula presented a variation if considered a

FC ˃1.5.

The

ADCY6 gene encodes a member of the adenylyl cyclase family of proteins that are required for the synthesis of cyclic AMP [

21]. Adenylyl cyclase is reported to present in 13- to 16-day-old bovine embryos and has been reported to modulate cAMP and cGMP concentrations - which determines the rapid proliferation of embryonic cells or even signaling to the endometrium [

22]. In the present study, detection of the NPR2 with its potential activity (derived of the modulation observed when the ligand -

i.e., CNP – was added to the IVC medium) in a cellular compartment other than the

cumulus cells, assumes a natural function for the NPR2/CNP complex also in pre-implantation embryos, at least in bovine and murine species. It was inferred that the elevation of

ADCY6 transcript abundance occurred due to exposure of morula to CNP, ultimately triggering greater conversion of ATP to cAMP.

In mammals,

BMP15 is related to oocyte maturation and also in cholesterol biosynthesis, improving oocyte competence and embryonic development in cattle [

23,

24]. The

BMP15 transcript was relatively elevated in morula that did not receive CNP treatment. Several studies have reported an increase in the

BMP15 transcript during maturation in oocytes from buffaloes, dogs, and cows [

24,

25,

26]. Furthermore, the metabolic pathways of

cumulus cells, particularly glycolysis and cholesterol biosynthesis, are highly affected when there is a mutation in the

BMP15 gene [

27]. Thus, we infer that CNP could be reducing

BMP15 expression by modulating cholesterol biosynthesis through cGMP elevations. This hypothesis is because that the CNP treatment did not decrease blastocyst production and hatching rates and did not increase transcripts negatively related to embryonic quality. Also, oocyte maturation, where the role of

BMP15 is more associated, has not been tested and therefore the role of

BMP15 in the IVC of embryos is an important point highlighted by this study.

A reduction in the abundance of

ACAT1 transcript was observed in CNP-treated morula.

ACAT1 promote free cholesterol to be esterified into cholesterol esters [

28]. In our study, however, we inferred that the reduction of

ACAT1 transcript may have been caused by CNP which modulated the metabolism of some lipid classes, reducing some cholesterol esters.

Another important point was that CNP-treated morula tended to lower concentrations of

CASP3 transcripts. This gene is directly linked with the cell death program, that is, the apoptosis [

29].

CASP3, in oocytes, is associated with low competence and death of the oocyte [

10,

30]. In this context, Kaihola et al. [

31] showed that in secretomes from high-quality blastocysts, the levels of

CASP3 were significantly lower than in embryos that became arrested, and low-quality blastocysts.

Several studies have demonstrated the interference of CNP in the apoptosis process. In a study with porcine COCs, the DNA damage was dramatically decreased due to CNP exposure at different concentrations and for 24 h. Also, CNP exposure significantly downregulated pro-apoptotic genes,

i.e.,

BAX,

CASP3,

C-MYC, and

P53 [

32]. Moreover, on average,

cumulus cell layers of human COCs cultured for 24 h in prematuration culture (PMC) supplemented with CNP showed a very low degree of caspase-3/7 activation [

33]. In addition, Zhang et al. [

34] observed a decrease in the proportion of DNA-fragmented nuclei in blastocysts from sheep oocytes pre-treated with 200 nM CNP for 4 h followed by 24 h IVM, compared with blastocysts from conventional 24, 26, or 28 h IVM.

Furthermore, initial studies suggest that mitochondria play a central role in apoptosis [

35], and after their injury, there is a loss of mitochondrial membrane potential and release of factors such as the apoptosis initiation factor and cytochrome C. Released of cytochrome C activates Caspase-9, which then activates effector caspases such as

CASP3 [

29]. Thus, we inferred that the reduction in the abundance of

CASP3 transcript, observed in the CNP treated group, potentially made possible the morula to have fewer damage associated with cell death.

In addition, in blastocysts treated with CNP, it was possible to observe a reduction, when evaluating the fold change, of targets related to predict embryo quality, lipid metabolism, fatty acid biosynthesis, elongation, endoplasmic reticulum action, synthesis steroid hormones, and catalyzes cholesterol cleavage

(BDNF, NLRP5, AGPAT9, ELOVL1, ELOVL4, IGFBP4 and

FDX1 transcripts). An indication of the decrease in the abundance of the

AGPAT9 transcript was observed in blastocysts treated with CNP.

AGPAT9 has been identified as a key regulator of lipid accumulation in adipocytes [

36], suggesting that this may be a biomarker for lipid droplet content in the embryo. In theory, with the reduction in the abundance of

AGPAT9 and other targets, blastocysts cultured with CNP should have a lower lipid content, however, based on the results presented we were unable to measure its content or lipid profile. Thus, further studies are needed regarding embryonic metabolism, in order to understand what are the real changes caused by the inclusion of CNP.

The family of elongases of very long-chain fatty acids (

ELOVL) are enzymes responsible for the condensation reaction necessary for the biosynthesis of long-chain fatty acids (FA). Increased

ELOVL1 expression is directly involved in the elongation of saturated and monounsaturated FA [

37]. The

ELOVL4 is an elongase responsible for the biosynthesis of very long chain (VLC, ≥C28) saturated (VLC-SFA) and polyunsaturated (VLC-PUFA) fatty acids [

38]. It is known that FA are mainly stored as triacyl glycerides (TAGs; main lipid class found in the cytoplasm of mammalian cells) and enclosed in lipid droplets [

39]. Also, their presence may be a compromising factor in cryopreservation processes, increasing risks of cellular injuries [

7]. In our results, we showed that

ELOVL4 was upregulated - considering the fold change - therefore, CNP treatment may have potentiated the biosynthesis of long-chain acids. However, we did not observe a reduction in the embryo production rate of CNP-treated embryos. Concomitantly, it was observed that control blastocysts (without CNP treatment) had a greater abundance of pro-apoptotic and apoptosis-related transcripts (

BID and

CASP3) than those that received CNP. This fact may suggest a potential protective effect of CNP on cell metabolism in bovine embryos during IVC.

In summary, this study detected and quantified the NPR2 (CNP receptor) for the first time, at least to our knowledge, in the pre-implantation stages of the in vitro produced bovine embryo. Furthermore, it was determined that the use of CNP at a higher concentration, than that described in the literature, may alter embryonic metabolism based on the abundance of some target transcripts. Also, that CNP concentration was not harm when embryo production rate was observed. Finally, in vivo, functional tests will be able to better investigate whether those alterations found in this study could be translated into better reproductive performance by embryos treated with CNP in the IVC.

Figure 1.

Illustrative experimental design. IVC, in vitro culture; EXP, experiment; GV, germinal vesicle; MII, metaphase II; PZ, presumptive zygotes; MO, morula; BL, blastocyst; CTL, control group; CNP, group treated with C-type natriuretic peptide.

Figure 1.

Illustrative experimental design. IVC, in vitro culture; EXP, experiment; GV, germinal vesicle; MII, metaphase II; PZ, presumptive zygotes; MO, morula; BL, blastocyst; CTL, control group; CNP, group treated with C-type natriuretic peptide.

Figure 2.

NPR2 localization in bovine oocytes and pre-implantation stage embryos. The green color indicates NPR2 staining, and the blue color indicates nuclear staining (DAPI). NPR2 protein was expressed in bovine oocytes and embryos at all stages. GV, germinal vesicle; M II, metaphase II; PZ, presumptive zygotes; Morula, morula stage; Blastocyst, blastocyst stage. Bar = 50 µm.

Figure 2.

NPR2 localization in bovine oocytes and pre-implantation stage embryos. The green color indicates NPR2 staining, and the blue color indicates nuclear staining (DAPI). NPR2 protein was expressed in bovine oocytes and embryos at all stages. GV, germinal vesicle; M II, metaphase II; PZ, presumptive zygotes; Morula, morula stage; Blastocyst, blastocyst stage. Bar = 50 µm.

Figure 3.

Box Plot of fluorescence intensity of NPR2 in oocytes and preimplantation stage embryos. Results are presented as the median and 1º and 3º interquartile intervals of five replicates/stage using 8 structures in total. Different letters above each box represent significant differences (P ≤ 0.05). GV, germinal vesicle; M II, metaphase II; PZ, presumptive zygotes; Morula, morula stage; Blastocyst, blastocyst stage. AU, arbitrary units.

Figure 3.

Box Plot of fluorescence intensity of NPR2 in oocytes and preimplantation stage embryos. Results are presented as the median and 1º and 3º interquartile intervals of five replicates/stage using 8 structures in total. Different letters above each box represent significant differences (P ≤ 0.05). GV, germinal vesicle; M II, metaphase II; PZ, presumptive zygotes; Morula, morula stage; Blastocyst, blastocyst stage. AU, arbitrary units.

Figure 4.

Effect of CNP treatment in IVC on differential gene expression in morula. Data represent the fold change of relative target abundance related to the reference gene. Downregulated transcription ACAT1 (P= 0.040), CASP3 (P=0.082) and BMP15 (P=0.013); and upregulated transcription ADCY6 (P= 0.057) with the addition of CNP (400 nM) on the D1 of culture. Results are represented by least-squares means ± SEM of four replicates/group. Different letters above each bar represent significant differences (P ≤ 0.08). Control (no treatment) and C-400 (400 nM of CNP).

Figure 4.

Effect of CNP treatment in IVC on differential gene expression in morula. Data represent the fold change of relative target abundance related to the reference gene. Downregulated transcription ACAT1 (P= 0.040), CASP3 (P=0.082) and BMP15 (P=0.013); and upregulated transcription ADCY6 (P= 0.057) with the addition of CNP (400 nM) on the D1 of culture. Results are represented by least-squares means ± SEM of four replicates/group. Different letters above each bar represent significant differences (P ≤ 0.08). Control (no treatment) and C-400 (400 nM of CNP).

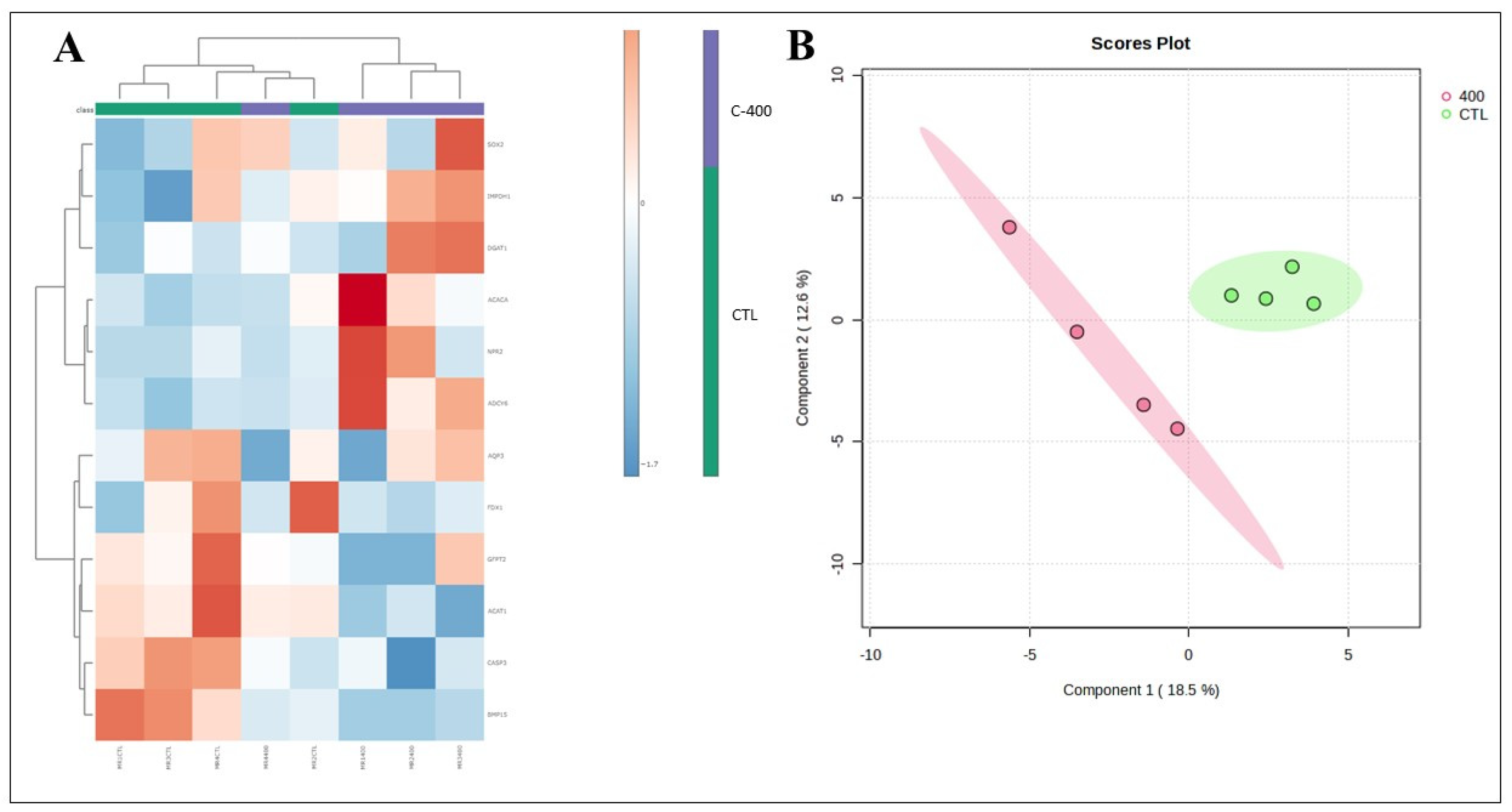

Figure 5.

- Multivariate analysis plots of the abundance of transcripts derived from untreated (control) and CNP-treated morula. (A) Cluster analysis heatmap showing transcriptional profiles abundance in only 12 genes most impacted from morula treated with 400 nM CNP and the control group. (B) 2D PLS-DA discrimination score plot between groups (5 morulas/group in 4 replicates).

Figure 5.

- Multivariate analysis plots of the abundance of transcripts derived from untreated (control) and CNP-treated morula. (A) Cluster analysis heatmap showing transcriptional profiles abundance in only 12 genes most impacted from morula treated with 400 nM CNP and the control group. (B) 2D PLS-DA discrimination score plot between groups (5 morulas/group in 4 replicates).

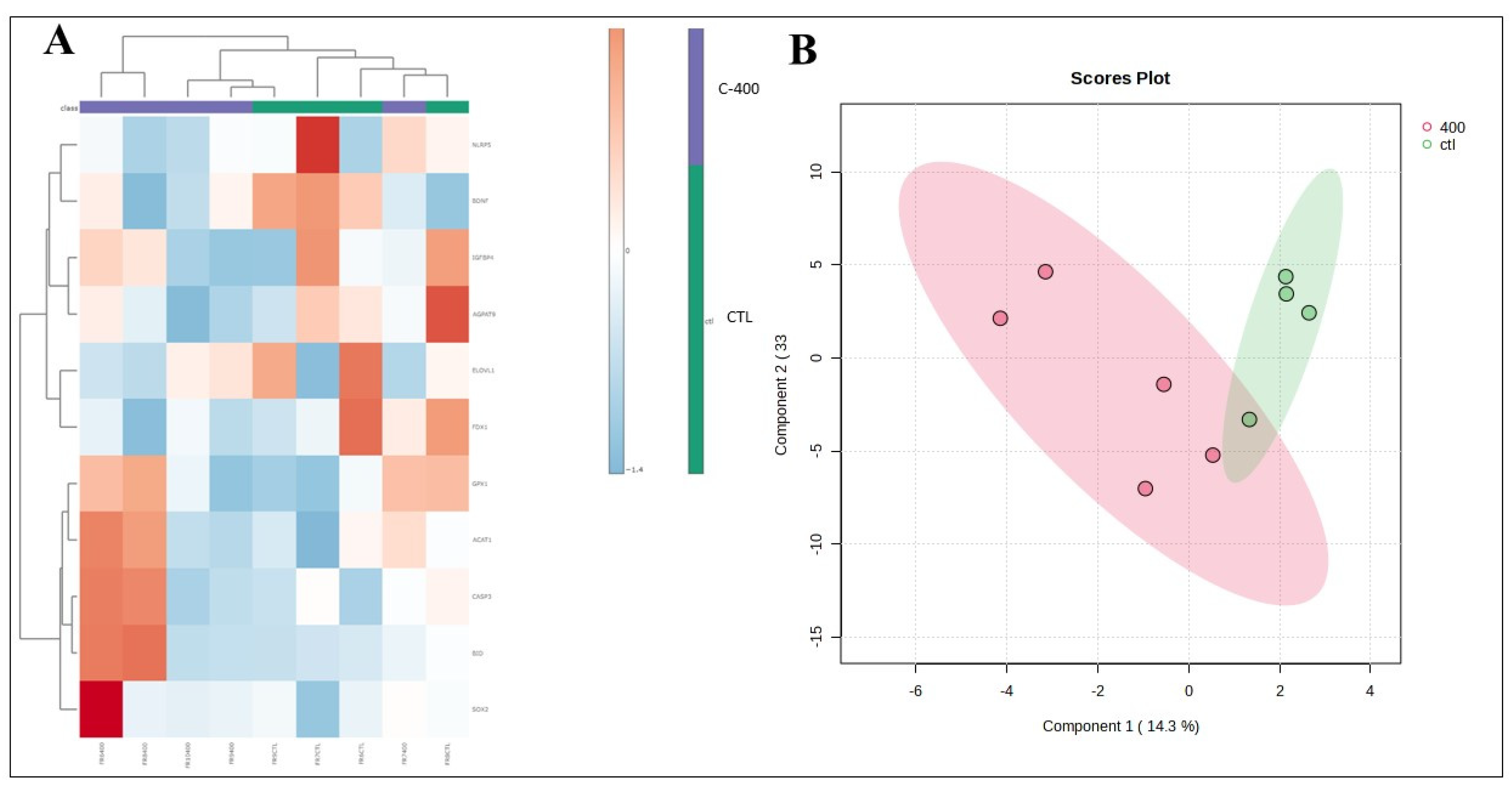

Figure 6.

- Multivariate analysis plots of the abundance of transcripts derived from untreated (control) and CNP-treated blastocyst. (A) Cluster analysis heatmap showing transcriptional profiles abundance in only 11 genes most impacted from blastocyst treated with 400 nM CNP and the control group. (B) 2D PLS-DA discrimination score plot between groups (3 embryos/group in 4 replicates).

Figure 6.

- Multivariate analysis plots of the abundance of transcripts derived from untreated (control) and CNP-treated blastocyst. (A) Cluster analysis heatmap showing transcriptional profiles abundance in only 11 genes most impacted from blastocyst treated with 400 nM CNP and the control group. (B) 2D PLS-DA discrimination score plot between groups (3 embryos/group in 4 replicates).

Table 1.

- Rate of in vitro produced bovine blastocyst supplemented with different concentrations of CNP from Day 1 (D1) of IVC.

Table 1.

- Rate of in vitro produced bovine blastocyst supplemented with different concentrations of CNP from Day 1 (D1) of IVC.

| Group |

Cumulus-oocyte complexes |

PZ |

Blastocyst |

| N |

N |

N (% mean ± SEM) |

| Control |

91 |

90 |

29 (32.81 ± 14.24) |

| C-100 |

87 |

87 |

30 (34.14 ± 5.61) |

| C-200 |

94 |

93 |

33 (35.45 ± 5.06) |

| C-400 |

90 |

88 |

41 (46.09 ± 7.76) |

| P-value |

- |

- |

0.082 |

Table 2.

– Rate of in vitro produced bovine blastocyst supplemented with different concentrations of CNP from Day 5 (D5) of IVC.

Table 2.

– Rate of in vitro produced bovine blastocyst supplemented with different concentrations of CNP from Day 5 (D5) of IVC.

| Group |

Cumulus-oocyte complexes |

PZ |

Blastocyst |

| N |

N |

N (% mean ± SEM) |

| Control |

182 |

180 |

60 (32.41 ± 5.45) |

| C-100 |

184 |

181 |

52 (28.62 ± 12.52) |

| C-200 |

186 |

183 |

48 (26.33 ± 5.64) |

| C-400 |

184 |

183 |

55 (29.17 ± 8.94) |

| P-value |

- |

- |

0.743 |

Table 3.

- Evaluation of blastocyst rate (D7) and hatching kinetic (D7, D8, and D9) of embryos cultured with or without of CNP (when added on Day 1 of culture).

Table 3.

- Evaluation of blastocyst rate (D7) and hatching kinetic (D7, D8, and D9) of embryos cultured with or without of CNP (when added on Day 1 of culture).

| Group |

PZ |

Blastocyst rate |

Hatched blastocyst D7 |

Hatched blastocyst D8 |

Hatched blastocyst D9 |

Total hatched blastocyst |

| N |

N (% mean ± SEM) |

N [% median (1st, 3rd)]* |

N (% mean ± SEM) |

N (% mean ± SEM) |

N (% mean ± SEM) |

| Control |

979 |

332 (34.13 ± 2.11) |

4 [0.98 (0.00, 2.11)] |

84 (25.76 ± 4.96) |

62 (17.88 ± 2.75) |

150 (44.80 ± 5.51) |

| C-400 |

1026 |

331 (32.55 ± 1.14) |

3 [0.00 (0.00, 1.06)] |

71 (20.58 ± 3.79) |

68 (20.00 ± 2.09) |

142 (41.34 ± 5.34) |

|

P-value |

- |

0.52 |

0.57 |

0.42 |

0.55 |

0.66 |

Table 4.

Upregulated and downregulated transcription observed in morula stage after treatment with CNP. The relative abundance of transcripts was selected based on the Fold change analysis (with a magnitude greater than 1.5 time, that is, with a threshold > 1.5). The values shown were calculated as the ratio of the control group to the treated group.

Table 4.

Upregulated and downregulated transcription observed in morula stage after treatment with CNP. The relative abundance of transcripts was selected based on the Fold change analysis (with a magnitude greater than 1.5 time, that is, with a threshold > 1.5). The values shown were calculated as the ratio of the control group to the treated group.

| |

Gene Symbol |

Definition |

Fold Change |

| |

IMPDH1 |

GTP / cGMP |

0.663 |

| |

CD40 |

Apoptosis |

0.627 |

| Upregulated |

ADCY6 |

cAMP / Meiotic arrest |

0.303 |

| |

ELF5 |

Cell differentiation / trophectoderm |

0.199 |

| |

NPR2 |

cGMP / Meiotic arrest |

0.190 |

| |

BMP15 |

Oocyte maturation / follicular development |

7.008 |

| |

FSHR |

Follicle stimulating hormone receptor / gonad development |

3.246 |

| |

NRP2 |

Cell survival / follicular development |

1.908 |

| Downregulated |

NANOG |

Pluripotency (ICM/TE) / when overexpressed, promotes cells to enter the S phase and proliferation |

1.878 |

| |

GFPT2 |

Oxidative stress |

1.866 |

| |

CASP3 |

Apoptosis |

1.835 |

| |

HSPA1A |

Cell survival / facilitates DNA repair |

1.579 |

| |

|

|

|

Table 5.

- Upregulated and downregulated transcription observed in blastocyst stage after treatment with CNP. The relative abundance of transcripts was selected based on the Fold change analysis (with a magnitude greater than 1.5 time, that is, with a threshold > 1.5). The values shown were calculated as the ratio of the control group to the treated group.

Table 5.

- Upregulated and downregulated transcription observed in blastocyst stage after treatment with CNP. The relative abundance of transcripts was selected based on the Fold change analysis (with a magnitude greater than 1.5 time, that is, with a threshold > 1.5). The values shown were calculated as the ratio of the control group to the treated group.

| |

Gene Symbol |

Definition |

Fold Change |

| |

HSPA5 |

Folding and assembly of proteins in the endoplasmic reticulum / degradation of misfolded proteins |

0.637 |

| Upregulated |

SOX2 |

Pluripotency/chromatin binding/DNA methylation |

0.571 |

| |

CASP3 |

Apoptosis |

0.513 |

| |

BID |

Apoptosis/Pro-Apoptotic |

0.408 |

| |

BDNF |

Supporting meiotic progression |

1.966 |

| |

NLRP5 |

maternal oocyte protein / required for normal early embryogenesis |

1.868 |

| |

AGPAT9 |

Predict embryo quality/Lipid metabolism |

1.794 |

| Downregulated |

IGFBP4 |

Either inhibit or stimulate the growth promoting effects of the IGFs |

1.700 |

| |

ELOVL4 |

Fatty acid biosynthesis, elongation, endoplasmic reticulum |

1.725 |

| |

ELOVL1 |

Fatty acid biosynthesis, elongation, endoplasmic reticulum |

1.670 |

| |

FDX1 |

Synthesis steroid hormones/ catalyzes cholesterol cleavage |

1.533 |