1. Introduction

The person-centered maternity care allows a positive experience during pregnancy, childbirth and postpartum, claiming women’s participation, evaluation, and intervention of their needs [

1,

2]. During obstetrical healthcare, the resources of the women to cope could collapse by physical, and psychosocial changes of motherhood [

3]. The processes involved in the maternity healthcare is essential to improve health outcomes, since facilitates the women adherence to clinical recommendations [

4,

5]. For women, the lack of knowledge about their sexual and reproductive rights, and rights as users of health service, increase the risk to acquire a passive role during maternity and experience situations that affect their integrity and lost autonomy [

6]. For the adaptation and well-being to motherhood, it is essential that woman receive and perceive social support from partner, family, and friends, health professional and her employer, emotional and procedural resources, physical care, and information [

3,

7]. In addition, the cognitive clarity and confidence to solve the demands of the motherhood are important considerations, since it has been related to greater adaptation to maternity [

8]. The coping to motherhood and empowerment of the woman during the healthcare process is also influenced by its resilience [

3,

9], affectivity [

10,

11] and beliefs [

12].

The healthcare providers would apply evaluation tools to assess the women knowledge related their rights and social, economic, emotional, and motivational resources. This will contribute to increase the positive experience in the health assistance. The recommendations in clinical evaluation consider guidelines for resolutions of the psychosocial issues and early prevention of health problems [

9]. Therefore, the healthcare providers can apply tools about coping strategies [

13], social support [

14], work-home interactions [

15], parenting stress [

16], among others. However, a simple application screening to identify the psychosocial needs would be suitable. In the obstetric context, the Prenatal Biomedical Risk Scale [

17], approaches the psychosocial resources from social support and mood, but does not assess other variables such as motivation, work conflicts and economic problems.

Considering the scarcity of tools that assess women’s knowledge of their healthcare rights during the entire maternity period (pregnancy, labor and postpartum) and the importance of evaluating women’s resources to face motherhood, this study aims to development and validate new tools regarding to the women’s knowledge of obstetric healthcare rights (MatCODE) and the perception of resource scarcity (MatER) during pregnancy, labor and early postpartum in the Spanish context.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethical Aspect

This study was approved by the Research Ethics Committees of Universidad Autónoma de Madrid (Madrid, Spain; Ref.: CEI-112-2199, January 22, 2021). All women willing to participate were given an online information sheet, describing the aims of the study, and the informed consent form was signed in each case. Data collection was anonymous, and databases were blinded. In addition, this study is adhered to the guidelines Standards for the Reporting of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies (STARD) [

18] for assessment scale protocols.

2.2. Questionnaire Development: Items Generation and Scale Construction

The new questionnaires were generated to report relevant statements to focus on women’s knowledge of obstetric healthcare rights (MatCODE) and perception of resource scarcity (MatER) during pregnancy, labor and early postpartum. In both questionnaires, items were generated from a review of literature [

9] and discussion with maternity experts to enhance content validity. Drawing from previous clinical experiences in providing maternity healthcare of the researchers, were identified 11 items for MatCODE and 9 items for MatER. Items for the questionnaires were scored on 5-point Likert scale, ranging in MatCODE from 1 = Strongly disagree to 5 = Strongly agree, and in MatER from 0 = Never to 4 = Always.

2.3. Expert Panel Review for Face and Content Validation

It was procedure to the content validation by expert judgement, and evaluation of face validity in a pilot cohort on a target population to assess the understandability of the questionnaires.

Content validity through judgment by a panel of 5 experts with more than ten years of experience in maternity research (a man and a woman clinical psychology, a woman midwifery, a man medical physiology and a woman obstetrician), who were selected to obtain different point-of-views on the methodological issues. These experts were not part of the item’s generation and scale construction. The experts independently assessed the readability, understanding, clarity of MatCODE and MatER. They also assessed the format of the questionnaires and whether an item evaluated what it was intended to evaluate and the importance of that item in the construct. Each judge assessed the content validity of each item and the instructions with a scale of 1 to 5 (from low to high degree of pertinent/relevant) based on three criteria (min = 3; max = 15); 1) the language clarity (if the semantic and syntactic rules of the item is comprehensive); 2) the relevance (if the item is important to quantity the objective of the instrument); and 3) the coherence (if the item is related to the research dimension). Based on the experts’ scores, for every item was calculated a content validity index (CVI-i), and Aiken’s V coefficient [

19]. This coefficient quantifies the relevance of each item regarding to language clarity, relevance and coherence domains based on the ratings of experts. The coefficient can have values between 0 and 1. The closer the value to 1, the greater validity [

20]. Thus, the value 1 is the highest possible value and indicates perfect agreement among the experts. In groups of 5 experts, total agreement is needed for the item to be valid. To assume as adequate the value of the coefficient should be >0.8 [

21]. In addition, the universal-CVI (UA-CVI) was calculated (proportion of items on a scale that achieves rating of 14 or 15 from all the experts) [

22].

The face validity was performed in a target cohort to assess the understandability and acceptability of the items. This pilot test was carried out in 27 women, selected by non-probabilistic sampling at the discretion of the research team. This pre-test cohort should meet the study’s inclusion criteria (>18 years; to have a labor or C-section in the last three years; to have received healthcare for the last pregnancy, labor and early postpartum; to have been assisted in Spain; and good comprehension of the Spanish). Women were asked to assess the understandability of the questionnaires and to suggest changes if they deemed it appropriate, and therefore, the women could contact the research team to improve their understanding of the items. Additionally, the final version of the scale was evaluated with INFLESZ, a Spanish validated tool used to evaluate text readability and easy reading by users of healthcare services (

https://legible.es/blog/escala-inflesz/). It is based on Szigriszt Pazos’ perspicuity value as: 0-40, very difficult; 40-55, moderately difficult; 55-65, average difficulty; 65-80, easy; and 80-100, very easy [

23].

2.4. Construct Validation Using Factorial Analysis

A cross-sectional study was designed to assess construct validity, reliability, divergent validity against the resilience scale (RS-14), the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS), and the Maternity Beliefs Scale (MBS), and known-groups validation.

Women participants were selected by a non-probability sampling procedure. According to the theory of factor analysis, there must be at least 15 observations per item in the analyzed tool [

24,

25]. Selection of the sample was done through the research group’s social networks. This technique has demonstrated an adequate recruitment response in other studies [

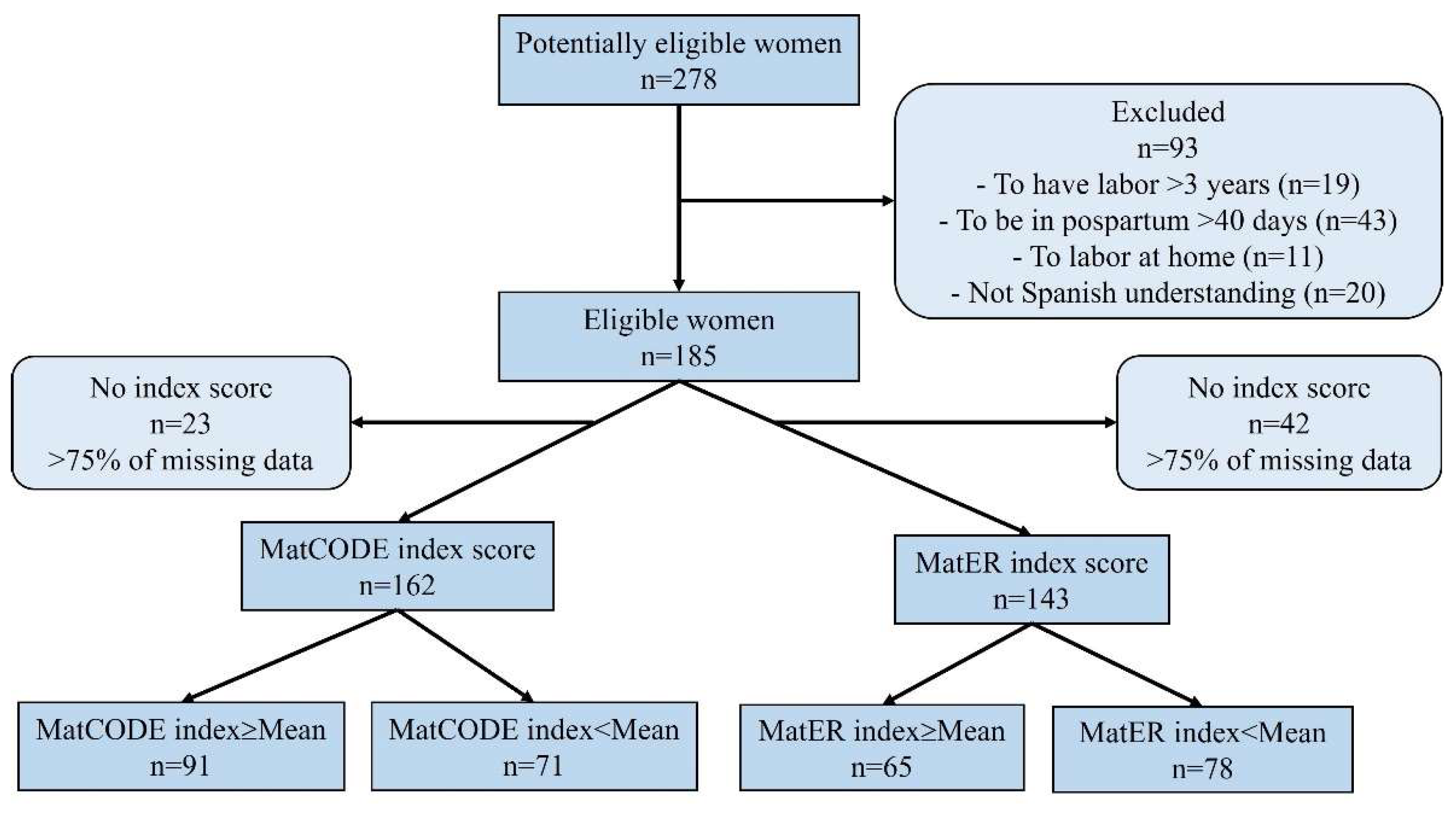

26]. In the recruitment, 278 women were contacted. Inclusion and exclusion criteria were applied to the women contacted. The inclusion criteria were as follows: >18 years, having vaginal labor or C-section in the last three years, have received healthcare for the last pregnancy, labor and early postpartum (up to 40 days after labor), and good Spanish language understanding. The exclusion criteria were inability to read/write in Spanish and home birth. Of the 278 women contacted, 185 met the inclusion and exclusion criteria. In the follow data analysis, it was considered withdrawal criteria (incorrect questionnaire, <75% of missing data, and participant’s desire to leave the study). Finally, the sample was consisted in 162 for MatCODE (withdrawal = 12.4%), and 143 for MatER (withdrawal = 22.7%). Adapted to STARD guidelines, a diagram of women through the study was reported in

Figure 1.

Data were collected from 1 September 2021 to 30 November 2023. A self-administered online tool was prepared by Qualtrics (

https://www.qualtrics.com/es/; accessed on 15 July 2021). Firstly, it was obtained sociodemographic and obstetric variables, and validated psychometric test and, secondly the MatCODE and MatER questionnaires.

The variables collected in the first part were age (years), education level, civil status (single/unmarried vs any type of relationship), employ status (active working vs unemployed), number of deliveries, type of last labor (vaginal vs C-section), if the last pregnancy was planned or desired (yes/no), use of assisted reproduction techniques (yes/no), multiple pregnancy (yes/no), gestational age in the last pregnancy (weeks), prematurity labor (<37 weeks of gestation), last labor by lithotomy (yes/no), presentation of a birth plan (yes/no) and adverse outcomes (yes/no) during pregnancy, labor or early postpartum.

The second part included: 1) the MatCODE questionnaire, a new tool designed to assess the level of knowledge that women have of their healthcare rights during pregnancy, labor or postpartum. The MatCODE is a 11-item scale scored in a Likert-type format from 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree. Higher score in MatCODE would indicate a greater awareness of their healthcare rights. 2) the MatER questionnaire, a new tool designed to assess the woman’s perception has/had of her pregnancy, labor, or early postpartum resources. The MatER is a 9-item scale scored in a Likert-type format from 0 = never to 4 = always. Higher score in MatER would indicate a lower perception of resources of the woman. The Spanish version of questionnaires can be found in the appendix A (MatCODE) and appendix B (MatER).

To assess divergent validity, women responded to 1) the Resilience scale (RS-14) [

27]. This scale asses the ability to cope with daily difficulties. It was used the 14-items version. The higher score, the greater the woman’s ability to cope with the problems of everyday life. Other studies reported a Cronbach`s α coefficient of 0.88. 2) The Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS) [

28]. The most widely used scales to measure emotion. This scale used 20 items, with 10 items measuring positive affect (e.g., excited, inspired) and 10 items measuring negative affect (e.g., upset, afraid). For the positive score (PANAS+), a higher score indicates more of a positive affect. For the negative score (PANAS-), a lower score indicates less of a negative affect. The PANAS obtained a Cronbach`s α coefficient scores ranging from 0.86 to 0.90 for the positive dimension (PANAS+) and 0.84 to 0.87 for the negative dimension (PANAS-) [

29]. 3) The Maternity Beliefs Scale (MBS). This scale identifies specific beliefs that women has related to maternity, based on the Rational Emotive Behavior Theory. The MBS has 13 items, clustered in 2 subscales: maternity as a sense of life (MBS-life) and maternity as a social duty (MBS-social). The higher score, the higher the woman’s belief in the indicated domain. The global Cronbach`s α coefficient was 0.93, being MBS-life = 0.92 and MBS-social = 0.83 [

30].

2.5. Data Analysis

A descriptive analysis of the variables and the items was conducted. Qualitative variables were expressed in relative frequencies (%); quantitative variables were expressed in mean ± standard error of mean (SEM). Symmetry and kurtosis were calculated for each item. In addition, the Relative Difficulty Indexes (RDI) and the normed Measure of Sampling Adequacy (MSA) values were calculated [

31]. The RDI evaluates the position of the items, nearly 75% of item values should fall between 0.40 and 0.60. Lower MSA values indicates that item randomly behaves, being 0.50 the cut-off limit (inappropriate item with non-discrimination) [

31].

Construct validity by factor analysis. The suitability of data for a factor analysis was assessed with the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin index (KMO) and Bartlett’s statistic. The KMO ≥ 0.75 was considered adequate and P ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant for Bartlett’s statistic. A confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was carried out based on the dimensional model obtained.

Following the González-de la Torre et al. approach [

22], the suitability of the factorial solution was assessed by the Root Mean Square of Residuals (RMSR; values < 0.08 is generally considered a good fit) [

32] and associated Kelley´s criterion [

33]. The Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA; values < 0.05 were considered a good fit and between 0.05 and 0.08 were considered a reasonable fit) [

32], the estimated Non-Centrality Parameter (NCP) and associated p-value (P), testing value large correspond to non-central distribution. The Non-Normed Fit Index (NNFI), the Comparative Fit Index (CFI), and the Adjusted Goodness-of-Fit Index (AGFI). NNFI and CFI values ≥ 0.95 and AGFI values > 0.90 were considered a good fit of the model [

24]. The Common part Accounted for (CAF) by a common factor model that expresses the extent to which the common variance in the data is captured in the common factor model [

34]. If CAF value is close to 0 means that more factors should be extracted. The Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC; degree of parsimony index), being lower values better fit. The Weighted Root Mean Square Residual (WRMR), values < 1.0 have been recommended to represent good fit [

35].

The matrix rotation of the items was applied in all solutions by a Promax oblique rotation. The number of factors to be retained was established through a parallel analysis, and the communality of the item was calculated. The 95% confidence intervals [95%CI] were calculated for the item scores and the model measures. To evaluate the dimensionality, the Unidimensional Congruence (UniCo), Explained Common Variance (ECV) and Mean of Item Residual Absolute Loadings (MIREAL) indices were used [

36]. The UniCo > 0.95, the ECV > 0.85 and the MIREAL < 0.30 indicated that the data could be considered as essentially unidimensional.

Construct validity by Rasch model. The MatCODE score was adapted from a 1–5 range to a 0–4 range, while MatER showed already this codification. Items’ fit was estimated by outfit Unweighted Mean Square fit statistic (UMS) and infit Weighted Mean Square Fit statistic (WMS). Fit index between 0.8 and 1.2 were considered as a good fit, while values between 0.5 and 1.5 were considered acceptable [

37]. The quality was established by the reliability (measure to order items’ difficulty), being desirable values > 0.7. In addition, to stablish the reliability of MatCODE and MatER, the Alpha (α) and Omega (ω) coefficients were calculated. The divergent analysis explores correlations between the MatCODE and MatER with related psychometric variables. Firstly, the global MatCODE and MatER scores were calculated by sum the Liker scores. Secondly, validated psychometric scales and MatCODE and MatER global score were standardized, and then, the Spearman´s correlation coefficient (ρ) was used, considering statistical correlation P < 0.05.

Known-groups validation. To explore the association between the different variables and the MatCODE and MatER global score, an inferential analysis was conducted, comparing groups of women likely to have experienced obstetric vulnerability according to several aspects described in the literature [

9]. The non-parametric Mann–Whitney U test was used to compare groups. The P ≤ 0.05 were considered statistically significant. The effect size was calculated using the Hedges’ g.

2.5.1. Statistical Software

The descriptive and inferential analyses were performed using R software within the RStudio interface (version 2022.07.1+554, 2022, R Core Team, Vienna, Austria) using

rio,

dplyr,

compareGroups,

devtools,

psych [

38] and

lavaan [

39] packages. For reliability was also used

eRm [

40] and

TAM [

41] packages. In addition, the factor analysis and index evaluation were carried out with the free software FACTOR

© Release version 12.04.05 ×64 bits (

https://psico.fcep.urv.cat/utilitats/factor/Download.html).

3. Results

3.1. Content Validity

All items in both questionnaires (MatCODE and MatER) received CVI-i > 0.80 values. The

Table S1 shows the scores assigned to each item by the experts, as well as the CVI-i values. In MatCODE, the UA-CVI was 54.5%, and in MatER was 77.8%.

Pilot cohort did not report difficulties in understanding any of the items. Therefore, item modifications were not introduced. According to INFLESZ, the perspicuity for MatCODE was 56.59 and for MatER was 57.85, both in an average of difficulty to read, which corresponds to a text with a normal level of readability.

3.2. Descriptive Analysis of Sample and Items

The women age was 28.5 ± 0.47 years (range: 18-42 years), being 89 (54.6%) primiparous, and 74 (45.4%) multiparous. Regarding the education level, 9 (5.5%) had primary education, 77 (47.2%) had secondary education and 77 (47.2%) had completed university studies. The 29 (17.8%) of the women was unmarried/single, being 134 (82.2%) married or with any type of sentimental relationship. Related to employ situation, 90 (55.2%) of the women was actively working and 73 (44.8%) was unemployed.

The last pregnancy was planned in the 86 (52.8%) of the women, and it was desirable in the 125 (76.7%). The gestational age was 38.7 ± 0.12 weeks (range: 29-41.5 weeks), being premature labor 29 (17.8%) cases. The women who were performed C-section in any gestation was 79 (48.5%), and who had assisted reproduction techniques were 7 (4.3%), being multiple pregnancy 3 (1.8%) cases. The lithotomy delivery position was performed in 139 (85.3%) cases.

The pregnancy complications were presented in 52 (31.9%) women, complications during labor in 28 (17.2%) and during early postpartum period in 26 (16.0%). Finally, women were asked if they had presented a birth plan and, if the plan had been observed. Many of the women (160; 98.8%) did not present a birth plan.

Regarding the MatCODE and MatER questionnaire responses, the

Table 1 shows a descriptive analysis, the symmetry and kurtosis of the items. In MatCODE, the RDI were >0.60 indicating a normal-range test and optimal pool of items. In addition, the normed MSA values were >0.50 suggesting that the item measure the same domain as the item pool. In MatER, the RDI ranges between 0.20 to 0.40 indicating that several items are placed in the extreme quartiles. The normed MSA were >0.50 and item measure the same domain.

3.3. Construct Validity by Factor Analysis

3.3.1. Confirmatory Factor Analysis

A confirmatory factor analysis was performed based on the proposed 11-item MatCODE questionnaire and 9-items MatER questionnaire (correlation matrices are showed in the

Figure S1). In MatCODE, the KMO and Bartlett’s statistic indicated an acceptable fit of the sample (KMO = 0.901 [0.827; 0.915]; P < 0.001 Bartlett´s test). The one-factor solution showed 65.1% explained variance, indicating a single-factor result in the parallel analysis. In MatER, the KMO and Barlett`s test showed a good fit (KMO = 0.842 [0.718; 0.850]; P < 0.001 Barlett´s test). Also, the one-factor solution showed 37.9% explained variance.

The robust goodness of fit values for MatCODE model were the RMSEA = 0.113 [0.105; 0.122], with an estimated NCP = 17.710 (P = 0.930); the NNFI = 0.966 [0.956; 0.972], the CFI = 0.973 [0.965; 0.977] and the BIC = 246.199 [238.344; 257.125]. Additionally, in the distribution of residuals, the RMSR yielded a value of 0.080 [0.05; 0.10], being Kelley’s criterion for an acceptable model = 0.079. The WRMR was 0.096 [0.05; 0.13], below 1.0 being considered good fit model. The AGFI was 0.987 [0.957; 0.994], and the CAF was 0.432.

The robust goodness of fit for MatER were the RMSEA = 0.067 [0.063; 0.072], with an estimated NCP = 9.585 (P = 0.843); the NNFI = 0.949 [0.896; 0.982], the CFI = 0.962 [0.922; 0.987] and the BIC = 133.484 [130.534; 137.375]. Additionally, in the distribution of residuals, the RMSR yielded a value of 0.093 [0.08; 0.09], being Kelley’s criterion for an acceptable model = 0.084. The WRMR was 0.094 [0.08; 0.09], being considered good fit model. The AGFI was 0.982 [0.940; 0.982], and the CAF was 0.498.

3.3.2. Exploratory Factor Analysis

For MatCODE, the Unidimensionality assessment showed UniCo = 0.987 [0.973; 0.997], ECV = 0.896 [0.848; 0.936] and MIREAL = 0.242 [0.174; 0.299]. For MatER, the values were UniCo = 0.945 [0.913; 0.981], ECV = 0.793 [0.728; 0.850] and MIREAL = 0.187 [0.176; 0.184]. These results supported the one-dimensionality of the scales. The results of the factor loadings for each item and its commonality can be seen in

Table 2.

In MatCODE, the reliability of items was 0.832, and in the MatER was 0.711, which indicated acceptable reliability. The overall reliability was explored by the omega (ω) and Cronbach’s alpha (α) coefficients. In MatCODE was ω = 0.95 and α = 0.94 [0.93; 0.96] and in MatER was ω = 0.79 and α = 0.78 [0.73; 0.83]. The infit WMS and outfit UMS values were showed in

Table 3. Infit WMS values indicated good or acceptable fit for all items except item 9 for MatCODE and item 5 for MatER. Outfit UMS values showed acceptable fit for all items in MatCODE. Item 5 for MatER obtained also higher UMS score. The removal of item 5 from MatER did not modify the divergent analysis (

Table S2) and known-groups validation (

Table S3).

3.4. Divergent Validity

The total score in the resilience scale, PANAS+ and PANAS- and MBS-life and MBS-social is reported in

Table 4. MatCODE and MatER show significantly negative correlation (ρ = -0.20 [-0.35; -0.03]; P = 0.019). In addition, the MatCODE and MatER scores show positive and negative correlations with resilience score, respectively. Similarly, significant correlations were showed with PANAS+. In addition, MatER, but not MatCODE, show positive correlations with PANAS-. Although, MBS-life score did not show any statistical correlation with MatCODE and MatER; MatCODE, but not MatER, shown statistically negative correlation with MBS-social dimension (

Table 4).

3.5. The Known-Groups Validation

The total MatCODE (range: 11-55) and MatER (range: 0-36) scores are calculated by adding individual item scores. The mean score recorded in the sample for the MatCODE was 47.10 ± 0.67 (Min = 11; Max = 55), and for the MatER was 10.60 ± 0.55 (Min = 0; Max = 30).

The MatER score, but not MatCODE, was significantly negative correlated with age (ρ = -0.169; P = 0.044). The MatCODE and MatER scores were not significantly different between primiparous and multiparous women, employ situation and complications during pregnancy and last labor. However, MatCODE and MatER scores were statistically different between women who desired the pregnancy, and MatER score also was different between women who planned pregnancy and developed postpartum complications (

Table 5).

4. Discussion

Given the importance of supporting women in their journey to motherhood, it is crucial to assess healthcare rights and perceptions of resources during maternity. To this end, both the MatCODE and MatER tools were contextually validated. Equally questionnaires passed through the psychometric characteristic steps to guarantee their reliability. According to Pedrosa et al. recommendations [

42], the content validity carried out by interdisciplinary experts with several years of experience, representatives of both sexes, who did not participate in the design of the questionnaires, allowing a comprehensive and objective analysis of the tools. In addition, the content validity showed consistency and representativeness of the items with the aim that tools assessment. CVi-I was used for maintaining the outcomes with Aiken’s V coefficient because it is acceptable for processes in which there are less than six experts [

42]. Thus, through the comparison of these measures, estimation of agreement was verified without the effect of the number of experts. Furthermore, face validity reinforced the acceptance of the items with a slightly improvement in the semantics of the items, which gives the validity of tools by other process [

43].

The divergent validity of MatCODE showed consistence with previous findings on the knowledge with empowerment and self-esteem [

8,

44]. The positive affective effects and greater adaptative capacity in the face of adversity are expected. Furthermore, according to the conception of maternity as a social duty, where the identity of motherhood passes through a paternalist perspective and being woman a passive subject [

12], can be consistent with MatCODE scores. A woman who conceives in this way of motherhood may be less aware of their health rights and oppositely decrease its empowerment. Similar to MatER, where higher score means fewer resources, its negative correlations suggest that lower resources the greater risk of affective vulnerability [

45]. The variables assessment of both questionnaires demonstrated an association with components that identify psychosocial vulnerability during maternity.

The factor analysis confirms unifactorial design of both questionnaires. This analysis revealed a greater explanatory variance for MatCODE, demonstrating the robustness of its items in representing the studied construct. The results related to MatER may be attributed to a lower representativeness of resource differences (presence or absence) within the women, potentially due to the reduced sample size. The items functioned as dependent factors that explain the latent variable of the questionnaires. Both questionnaires had an adequate model fit. However, the item 5 of MatER showed low saturation of the construct. Similarly, in the Rasch analysis was demonstrated tendency towards randomness. According to Lloret-Segura et al., these items should be modified or eliminated for the final proposal of questionnaire [

25]. However, our results did not show any change in the validation analyses by removing it. This may be because the whole model showed good robustness indices in the exploratory and confirmatory analysis. In addition, and similar to other authors, the known-groups validation showed that younger age [

46] an unplanned pregnancy [

47], and obstetrical complications [

48] were associated with increase of perceived difficulties in coping to maternity, specifically in psychosocial resources.

When there is an unplanned pregnancy, women may have greater difficulty to accept motherhood. According to Martínez-Galiano & Delgado-Rodríguez [

44], the participation of the woman in aspects related to her gestational health depends directly on her awareness of the event. Therefore, it is likely that a woman has less awareness in an unplanned pregnancy and, therefore, less acceptance, generating a greater negative attitude and low participation in her healthcare.

In summary, both new questionnaires, MatCODE and MatER, are valid and reliable assessment tools for Spanish context, which can be useful for complement screening and psychosocial monitoring during pregnancy, childbirth and postpartum. This would impact to the improve of women’s well-being and the person-centered maternity healthcare, since it contributes to individual profiling of the psychosocial needs and guide the care to prevent health issues. Specific, the questionnaires afford women to identify limited resources for coping the changes of motherhood (MatER), and the needs for education in rights and empowerment in the healthcare process (MatCODE). The questionnaires are complementary, and therefore, they can integrate an analysis with other components that also affect women’s well-being, such as obstetric conditions [

49], mental history, or lifestyles [

45], among others. Besides, if the score of the questionnaires indicates any need of psychosocial intervention, the recommendation would be to extend the assessment with other tool such as a clinical interview or tests for identified risk variables.

The limitation of the study could be considered the small sample size and the restriction in the Spanish-context, suggesting validation in other sociocultural contexts with larger samples. This in coherence to Lloret-Segura et al., in which the number of elements analyzed, and the communality indicate the need for a larger sample [

25]. Since the variables evaluated with MatCODE and MatER have a psychosocial focus, they may depend on sociocultural components, it is important to delimited them in the analysis of future psychometric research.

5. Conclusions

During maternity, coping and suitable support are importance to fit the women for motherhood social roles. The healthcare providers need tools to assess health rights and women perception of resources to apply adequate intervention. MatCODE and MatER are tools with adequate psychometric properties, reliable and useful for measuring women’s knowledge about their healthcare rights and perception of resources during maternity in Spanish-speaking context. Additionally, the questionnaires are easy to complete by the women and to extract the scores by health staffing. MatCODE and MatER can guide to the healthcare providers on psychosocial intervention for better fit outcomes during maternity. It would be useful to validate these tools in other cultural contexts and their relationship with obstetric violence.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org, Figure S1: Pearson´s correlation coefficients of the items from the questionnaires focus on women’s knowledge of obstetric healthcare rights (MatCODE) and perception of resource scarcity (MatER) during pregnancy, labor and early postpartum; Table S1: Expert´s scores, content validity index and Aiken’s V coefficient in each item and global for MatCODE and MatER questionaries; Table S2: The divergent analysis removing item 5 from MatER; Table S3: The known-groups validation removing item 5 from MatER.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.S.S.-F., M.A.S. and D.R.-C.; methodology, C.S.S.-F., M.A.S.; software, D.R.-C.; validation, C.S.S.-F., E.G. and D.R.-C.; formal analysis, D.R.-C.; investigation, C.S.S.-F., M.A.S. and D.R.-C.; resources, E.G., and D.R.-C.; data curation, C.S.S.-F.; writing—original draft preparation, C.S.S.-F. and M.d.l.C.; writing—review and editing, S.M.A., E.G. and D.R.-C.; visualization, D.R.-C.; supervision, M.d.l.C., S.M.A. and D.R.-C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Universidad Autónoma de Madrid (protocol code CEI-112-2199, approved on 22 January 2021).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/

Supplementary Materials, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors express their thank to all the women who selflessly answered the applications.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Appendix A

Spanish version of women’s knowledge of obstetric healthcare rights questionnaire (MatCODE).

Escala de conocimiento de la mujer sobre sus derechos de atención obstétrico-ginecológica.

A continuación, se describen sentimientos, formas de pensar o actuar como usuaria de los servicios de salud. Siguiendo la escala de respuesta, marque con una «X» qué grado de acuerdo o en desacuerdo está con las situaciones que se plantean sobre el proceso de atención médica durante su último embarazo, parto y postparto inmediato (hasta 40 días después el parto).

1 = Totalmente en desacuerdo; 2 = En desacuerdo; 3 = Ligeramente en desacuerdo; 4 = De acuerdo; 5 = Totalmente de acuerdo.

| |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

| 1. Sentirse capacitada para solicitar la atención en servicios sanitarios según su necesidad. |

|

|

|

|

|

| 2. Tomar decisiones libremente, sobre qué instituciones y profesionales de salud la atienden, y del curso y tipos de cuidados y tratamientos. |

|

|

|

|

|

| 3. Solicitar información detallada sobre su estado de salud y el de sus hijos. |

|

|

|

|

|

| 4. Expresar libremente al personal sanitario sus creencias, sentimientos, dudas y necesidades. |

|

|

|

|

|

| 5. Solicitar una atención médica honesta, respetuosa y amable. |

|

|

|

|

|

| 6. Pedir la privacidad de su cuerpo. |

|

|

|

|

|

| 7. Solicitar la confidencialidad de su información íntima e historia clínica. |

|

|

|

|

|

| 8. Pedir establecer el contacto piel con piel inmediato con el recién nacido. |

|

|

|

|

|

| 9. Solicitar acompañamiento familiar y/o social durante el proceso de atención médica, incluyendo el parto o la cesárea. |

|

|

|

|

|

| 10. Pedir una atención médica no discriminatoria por razones sociales, políticas, religiosas, económicas, educativas, de orientación sexual, u otras. |

|

|

|

|

|

| 11. Solicitar el cumplimiento de los derechos que posee como ser humano. |

|

|

|

|

|

Appendix B

Spanish version of women´s perception of resource scarcity (MatER).

Escala de conocimiento de la mujer sobre sus derechos de atención obstétrico-ginecológica.

A continuación, se describen situaciones que una mujer puede presentar durante su embarazo, parto y postparto inmediato (hasta 40 días después el parto). Siguiendo la escala de respuesta, marque con una «X» la frecuencia con la que presentó la situación mencionada.

0 = Nunca; 1 = Casi nunca; 2 = Alguna vez; 3 = Casi siempre; 4 = Siempre.

| |

0 |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

| 1. Presenté dificultades económicas. |

|

|

|

|

|

| 2. Tuve problemas en mi trabajo. |

|

|

|

|

|

| 3. Estuve desmotivada por los cambios que conllevaría la maternidad. |

|

|

|

|

|

| 4. Estuve insatisfecha con el apoyo recibido por mis familiares y conocidos. |

|

|

|

|

|

| 5. El apoyo recibido de mi pareja/padre/progenitor de mi(s) bebé(s) fue escaso. |

|

|

|

|

|

| 6. Presenté dificultades para mantener mis actividades de ocio, entretenimiento o deporte. |

|

|

|

|

|

| 7. Mi salud se deterioró y/o fue inestable. |

|

|

|

|

|

| 8. Tuve cambios bruscos en mi estado de ánimo. |

|

|

|

|

|

| 9. Tuve dificultad para atender y analizar con claridad las situaciones frente a las que debía tomar una decisión. |

|

|

|

|

|

References

- Castellano Bentancur, G.; Aleman Riganti, A.; Nion Celio, S.; Sosa, S.; Verges, M. Humanization of Health Care, Rocha Public Maternity Hospital, 2014-2016. Uruguayan J Nurs 2022, 17, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sudhinaraset, M.; Giessler, K.; Nakphong, M.K.; Roy, K.P.; Sahu, A.B.; Sharma, K.; Montagu, D.; Green, C. Can Changes to Improve Person-Centred Maternity Care Be Spread across Public Health Facilities in Uttar Pradesh, India? Sex Reprod Health Matters 2021, 29, 394–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osorio Castaño, J.H.; Calderón Bejarano, H.; Noguera Ortiz, N.Y. Becoming a Mother and Preparation for Motherhood. An Exploratory Qualitative Study. Nursing Research: Image and Development 2023, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Añel Rodríguez, R.M.; Aibar Remón, C.; Martín Rodríguez, M.D. La Participación Del Paciente En Su Seguridad. Aten Primaria 2021, 53, 102215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steetskamp, J.; Treiber, L.; Roedel, A.; Thimmel, V.; Hasenburg, A.; Skala, C. Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder Following Childbirth: Prevalence and Associated Factors—a Prospective Cohort Study. Arch Gynecol Obstet 2022, 306, 1531–1537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jardim, D.M.B.; Modena, C.M. Obstetric Violence in the Daily Routine of Care and Its Characteristics. Rev Lat Am Enfermagem 2018, 26, e3069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Fernández, R.; Rodríguez-Llagüerri, S.; Presado, M.H.; Baixinho, C.L.; Martín-Vázquez, C.; Liebana-Presa, C. Autoeficacia En La Lactancia Materna y Apoyo Social: Un Estudio de Revisión Sistemática. New Trends in Qualitative Research 2023, 18, e875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristensen, I.H.; Simonsen, M.; Trillingsgaard, T.; Pontoppidan, M.; Kronborg, H. First-Time Mothers’ Confidence Mood and Stress in the First Months Postpartum. A Cohort Study. Sexual & Reproductive Healthcare 2018, 17, 43–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva-Fernandez, C.S.; de la Calle, M.; Arribas, S.M.; Garrosa, E.; Ramiro-Cortijo, D. Factors Associated with Obstetric Violence Implicated in the Development of Postpartum Depression and Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder: A Systematic Review. Nurs Rep 2023, 13, 1553–1576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galvan, T.; Hurwich-Reiss, E.; Watamura, S.E. Latina Mothers’ Mental Health: An Examination of Its Relation to Parenting and Material Resources. Fam Process 2022, 61, 1646–1662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCauley, M.; White, S.; Bar-Zeev, S.; Godia, P.; Mittal, P.; Zafar, S.; van den Broek, N. Physical Morbidity and Psychological and Social Comorbidities at Five Stages during Pregnancy and after Childbirth: A Multicountry Cross-Sectional Survey. BMJ Open 2022, 12, e050287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Obregón, N.; Armenta Hurtarte, C.; Harari, D.; Ortíz-Izquierdo, R. Maternidad Cuestionada: Diferencias Sobre Las Creencias Hacia La Maternidad En Mujeres. Rev Psi 2020, 19, 104–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tous-Pallarés, J.; Espinoza-Díaz, I.M.; Lucas-Mangas, S.; Valdivieso-León, L.; del Rosario Gómez-Romero, M. CSI-SF: Psychometric Properties of Spanish Version of the Coping Strategies Inventory - Short Form. Anales de Psicología 2022, 38, 85–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellón Saameño, J.A.; Delgado Sánchez, A.; Luna del Castillo, J.D.; Lardelli Claret, P. Validity and Reliability of the Apgar-Family Questionnaire on Family Function. Atención primaria: Publicación oficial de la Sociedad Española de Familia y Comunitaria 1996, 18, 289–296. [Google Scholar]

- Moreno Jiménez, B.; Sanz Vergel, A.I.; Rodríguez Muñoz, A.; Geurts, S. Propiedades Psicométricas de La Versión Española Del Cuestionario de Interacción Trabajo-Familia (SWING). Psicothema 2009, 21, 331–337. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Rivas, G.R.; Arruabarrena, I.; de Paúl, J. Parenting Stress Index-Short Form: Psychometric Properties of the Spanish Version in Mothers of Children Aged 0 to 8 Years. Psychosocial Intervention 2020, 30, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrera, J.A.; Salmerón, B.; Hurtado, H. Prenatal Biopsychosocial Risk Assessment and Low Birthweight. Soc Sci Med 1997, 44, 1107–1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bossuyt, P.M.; Reitsma, J.B.; Bruns, D.E.; Gatsonis, C.A.; Glasziou, P.P.; Irwig, L.; Lijmer, J.G.; Moher, D.; Rennie, D.; De Vet, H.C.; Kressel, H.Y. STARD 2015: An Updated List of Essential Items for Reporting Diagnostic Accuracy Studies. BMJ 2015, 351–h5527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aiken, L.R. Three Coefficients for Analyzing the Reliability and Validity of Ratings. Educ Psychol Meas 1985, 45, 131–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escurra Mayaute, L.M. Cuantificación de La Validez de Contenido Por Criterio de Jueces. Revista de Psicología 1969, 6, 103–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penfield, R.D.; Giacobbi, P.R., Jr. Applying a Score Confidence Interval to Aiken’s Item Content-Relevance Index. Meas Phys Educ Exerc Sci 2004, 8, 213–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-de la Torre, H.; González-Artero, P.N.; Muñoz de León-Ortega, D.; Lancha-de la Cruz, M.R.; Verdú-Soriano, J. Cultural Adaptation, Validation and Evaluation of the Psychometric Properties of an Obstetric Violence Scale in the Spanish Context. Nurs Rep 2023, 13, 1368–1387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrio-Cantalejo, I.M.; Simón-Lorda, P.; Melguizo, M.; Escalona, I.; Marijuán, M.I.; Hernando, P. Validation of the INFLESZ Scale to Evaluate Readability of Texts Aimed at the Patient. Anales Sis San Navarra 2008, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrando, P.J.; Lorenzo-Seva, U.; Hernández-Dorado, A.; Muñiz, J. Decalogue for the Factor Analysis of Test Items. Psicothema 2022, 34, 7–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lloret-Segura, S.; Ferreres-Traver, A.; Hernández-Baeza, A.; Tomás-Marco, I. Exploratory Item Factor Analysis: A Practical Guide Revised and Updated. Anal. Psicol. 2014, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gila-Díaz, A.; Witte Castro, A.; Herranz Carrillo, G.; Singh, P.; Yakah, W.; Arribas, S.M.; Ramiro-Cortijo, D. Assessment of Adherence to the Healthy Food Pyramid in Pregnant and Lactating Women. Nutrients 2021, 13, 2372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damásio, B.F.; Borsa, J.C.; da Silva, J.P. 14-Item Resilience Scale (RS-14): Psychometric Properties of the Brazilian Version. J Nurs Meas 2011, 19, 131–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watson, D.; Clark, L.A.; Tellegen, A. Development and Validation of Brief Measures of Positive and Negative Affect: The PANAS Scales. J Pers Soc Psychol 1988, 54, 1063–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magyar-Moe, J.L. Positive Psychological Tests and Measures. In Therapist’s Guide to Positive Psychological Interventions; Elsevier, 2009; pp. 43–72. [Google Scholar]

- González, C.; Calleja, N.; Bravo, C.; Meléndez, J. Escala de Creencias Sobre La Maternidad: Construcción y Validación En Mujeres Mexicanas. Revista Iberoamericana de Diagnóstico y Evaluación – e Avaliação Psicológica 2019, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenzo-Seva, U.; Ferrando, P.J. MSA: The Forgotten Index for Identifying Inappropriate Items before Computing Exploratory Item Factor Analysis. Methodology 2021, 17, 296–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finch, W.H. Using Fit Statistic Differences to Determine the Optimal Number of Factors to Retain in an Exploratory Factor Analysis. Educ Psychol Meas 2020, 80, 217–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelley, T.L. Essential Traits of Mental Life, Harvard Studies in Education, 1st ed.; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1935; Volume 26. [Google Scholar]

- Lorenzo-Seva, U.; Timmerman, M.E.; Kiers, H.A.L. The Hull Method for Selecting the Number of Common Factors. Multivariate Behav Res 2011, 46, 340–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiStefano, C.; Liu, J.; Jiang, N.; Shi, D. Examination of the Weighted Root Mean Square Residual: Evidence for Trustworthiness? Struct Equ Modeling 2018, 25, 453–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrando, P.J.; Lorenzo-Seva, U. Assessing the Quality and Appropriateness of Factor Solutions and Factor Score Estimates in Exploratory Item Factor Analysis. Educ Psychol Meas 2018, 78, 762–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bond, T.G.; Fox, C.M. Applying the Rasch Model, 2nd ed.; Psychology Press, 2013; ISBN 9781135602659. [Google Scholar]

- Revelle, W. Psych: Procedures for Psychological, Psychometric, and Personality Research 2024.

- Rosseel, Y. Lavaan: An R Package for Structural Equation Modeling. J Stat Soft 2012, 48, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mair, P.; Hatzinger, R. Extended Rasch Modeling: The ERm Package for the Application of IRT Models in R. J Stat Softw 2007, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robitzscha, A.; Kiefer, T.; Wu, M. TAM: Test Analysis Modules 2024.

- Pedrosa, I.; Suárez-Álvarez, J.; García-Cueto, E. Evidencias Sobre La Validez de Contenido: Avances Teóricos y Métodos Para Su Estimación [Content Validity Evidences: Theoretical Advances and Estimation Methods]. Acción Psicológica 2014, 10, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merino-Soto, C. Coeficientes V de Aiken: Diferencias En Los Juicios de Validez de Contenido. MHSalud: Revista en Ciencias del Movimiento Humano y Salud 2023, 20, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Galiano, J.M.; Delgado-Rodríguez, M. The Relegated Goal of Health Institutions: Sexual and Reproductive Health. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2021, 18, 1767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balanta Gonzaliaz, L.M.; Gaitán Gómez, O.L.; Oñmedo Caicedo, L.V.; Ocoro Vergara, J.A. Modifiable Risk Factors in Pregnant Women for the Development of Mental Disorders: Integrative Reviews. Cuidarte 2023, 12. [Google Scholar]

- Kimberley Lissette, M.; Huamán Santos, R.A.; Espinoza Rojas, R. Factors Associated with Post-Delivery Complications, According to the Demographic and Family Health Survey, Perú - 2019-2020. Revista de la Facultad de Medicina Humana 2023, 23, 61–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chilipio Chiclla, M.A.; Santillán Árias, J.P. Non-Planned Pregnancy as a Risk Factor for Late Start and Abandonment of Prenatal Care. Rev. Int. Salud Materno Fetal 2019, 4, 3–9. [Google Scholar]

- Genchi-Gallardo, F.J.; Juárez, S.; Solano-González, N.L.; Rios-Rivera, C.E.; Paredes-Solís, S.; Andersson, N. Prevalence of Postpartum Depression and Its Associated Factors in Users of a Public Hospital at Acapulco, Guerrero, Mexico. Ginecol Obstet Mex 2021, 89, 927–936. [Google Scholar]

- Ramiro-Cortijo, D.; Herrera, T.; Rodríguez-Rodríguez, P.; López De Pablo, Á.L.; De La Calle, M.; López-Giménez, M.R.; Mora-Urda, A.I.; Gutiérrez-Arzapalo, P.Y.; Gómez-Rioja, R.; Aguilera, Y.; et al. Maternal Plasma Antioxidant Status in the First Trimester of Pregnancy and Development of Obstetric Complications. Placenta 2016, 47, 37–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).