1. Introduction

Metagenomics studies are culture-independent approaches that improve our understanding of the composition, structure, and genomics of microbial communities in sediments associated with natural or contaminated water bodies. Also, metagenomics is key to gain insights on the role of microorganisms in ecosystem services, on their adaptive strategies and metabolic capabilities to colonize environments under extreme physical and chemical conditions and acquire useful genetic information on members of microbial communities [

1,

2].

The Atacama Desert is known as a territory under polyextreme environmental conditions where life is mostly restricted by two major natural factors: desiccation and solar radiation; however, this dryland is a biodiversity hotspot with genetic richness that includes prokaryotic and eukaryotic life forms adapted to life-limiting environmental conditions [

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8]. Rivers, lakes, and ponds in the Atacama Desert, where liquid water is not a limiting factor, are proper habitats for life. Most of these water bodies are found at the pre-Andean and Andean territories where precipitations are 50-fold higher than those at the Atacama hyper arid core [

9,

10]. In those territories, the water chemistry of surface and ground waters is influenced by active and regular volcanism, weather regimes and water-rock-soil interactions [

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16]. Under such influence, the hydrochemistry of water bodies impact on the abundance and diversity of microbial communities, favoring the colonization of microbes having adequate adaptive solutions. Amuyo Ponds (AP) in northern Chile are an example of such situation. They are three colored ponds (Yellow Pond, Red Pond, and Green Pond) located at 3,700 m above sea level, at the Arica and Parinacota Region, in northern Chile. They have geothermal origins, their waters are rich in arsenic, boron, and other dissolved salts, and drain into the Caritaya River, a main affluent for the Caritaya Dam, within the Camarones Basin [

13,

16,

17]. Substantial hydrogeochemical studies have been conducted at AP, but limited biological information is available. Previous reports showed the presence of amphipods and microbial mats at small saline pools around the ponds [

17] and bacteria have also been isolated to evaluate their agricultural potential [

18].

Thus, AP are geothermal habitats colonized by a partially known microbiome enduring the prevailing extreme physical and chemical environmental conditions. Comparing the hydrochemical composition [

17,

18], AP sediments are a more challenging environment for microbial life than Amuyo waters. Then, we report the first metagenomics insight on microbial composition and diversity in AP sediments, showing a highly diverse microbial life dominated by members of the Bacteria domain, a much lower presence of member from the Archaea and Eukarya domains, and a large viral presence. We also report examples of putative functional capabilities and metagenome-assembled genomes (MAG) of selected microorganisms and viruses. Preliminary reports on metagenomics analyses on Amuyo Ponds sediments and metal resistance were presented at the XIV Workshop CeBiB: Genomics, Bioinformatics and Metabolic Engineering for Biotechnological Applications, during December 6-8, 2021, at Santa Cruz, Chile, and November 29-30, 2022, at Santiago, Chile.

2. Materials and Methods

Site description. Yellow Pond (YP; 19°03′25″S, 69°15′12″W), Red Pond (RP; 19°03′28″S, 69°15′10″W), and Green Pond (GP; 19°03′31″S, 69°15′11″W) are three hydrothermal colored ponds located at 3,700 m above sea level, at the Arica and Parinacota Region, in northern Chile. Based on Amuyo Ponds images from Google Earth Pro (accessed and analyzed on October, 2021) the closest distances of YP, RP, or GP to the Caritaya River margin are 40 m, 120 m, and 215 m, respectively; and the closest distance among them are 40 m (RP to GP), 60 m (RP to YP), and 175 m (YP to GP) (

Figure 1). Collection of sediment samples was conducted during December 2013 at each Amuyo Pond, at a depth of 10-15 cm, and refrigerated until used (

Figure 2).

DNA extraction, sequencing, and metagenomics analyses. Total DNA from the upper 2-cm sediment layer (1 g) was extracted using the Ultraclean DNA extraction kit (MO BIO Laboratories Inc., Carlsbad, CA, USA), following the protocol provided by the manufacturer. Quality and DNA concentrations were evaluated by gel electrophoresis and UV/Vis spectroscopy (NanoDrop ND-1000, Peq-lab, Erlangen, Germany). The DNA was sequenced at the Greehey Children’s Cancer Research Institute Next Generation Sequencing Facility, UT Health Science Center, University of Texas System, San Antonio, TX, USA. Sequencing was achieved using the Illumina HiSeq technology with pair end reads, with an average read length of 100 bp, with good quality scores, as evaluated by the FastQC program (version 0.10.0). The sequencing produced a total of 76,170,294 reads, after QC. Sequencing reads are available at the Sequence Read Archive (SRA) with accession numbers SRR30290574; SRR30505203; and SRR30505202.

Bioinformatic Analysis. The metagenomic sequences were submitted to the Rapid Annotation using Subsystems Technology for Metagenomes (MG-RAST) web server [

19] for a taxonomic and functional assignment using default parameters. In addition, metagenomic assembly was done using MEGAHIT assembler v.1.2.9 [

20], and binning was conducted using the PATRIC web server (21]. The complete genome was annotated using Rapid Annotations using Subsystem Technology (RAST) server version 4.0. In addition, in-house BLAST analysis was done against customized metal resistance genes databases.

3. Results

On the microbiome and virome of Amuyo Ponds sediments.

Comparative statistics of the sequences post QC are shown in

Table 1. GP, YP, and RP sediments accounted for nearly 23, 25.5, and 27.5 million sequences, respectively. Sequences from GP and RP sediments showed similar GC% (57 %), while a higher percentage was observed in YP sediment (62%). Post QC sediment sequences were dominated by bacterial sequences in all Amuyo Ponds, providing an insight on their microbial community composition and diversity (

Table 2). Other minor sequences were related to viruses and the Eukarya and Archaea domains.

After metagenomics analyses, the relative abundance for major bacterial classes in Amuyo sediments was Gammaproteobacteria > Betaproteobacteria > Alphaproteobacteria > Bacilli. Genus Pseudomonas was more abundant in GP and YP sediments, while genera Pseudomonas, Aeromonas, and Shewanella were enriched in RP sediments (

Figure 3). Archaeal sequences were more abundant in RP sediments, but all three sediments showed similar composition and were enriched with sequences belonging to the classes Archaeoglobi (phylum Euryarchaeota) and Halobacteria (phylum Euryarchaeota) (

Figure 3). Also, the most abundant Fungi sequences in Amuyo sediments belonged to the classes Blastocladiomycetes (phylum Blastocladiomycota), Eurotiomycetes (phylum Ascomycota) and Saccharomycetes (phylum Ascomycota), with an interesting genus diversity (Gibberella, Neosartoria, and Scizosaccharomices, among them) (

Figure 3).

The archaeal community in AP sediments was found to be enriched in methanogens (

Figure 3.B.2). Genus Methanosarcina (Euryarcheota phylum) is a highly efficient methane producers and was most abundant, suggesting that members of the Amuyo microbial community may be considered new models to inquire into methanogenesis and methanotrophic cycles in such anoxic environment. Also, metagenomic sequences retrieved from AP sediments showed diversity and major relative abundance on fungal genera Gibberella, Neosartorya, Schizosaccharomyces, Aspergillus, and Saccharomyces in all three ponds sediments (

Figure 3.C2).

The substantial number of microbial sequences obtained from the metagenomic analyses of AP sediments and the proximity among Amuyo Ponds afford an insight on microbial distribution in each pond but also on the common sequences among each other (

Figure 4). More than 800 bacterial genera were shared among AP sediments, but a lower and distinct number can be assigned to each pond: 17, 23, and 44 genera for YP, RP, and GP, respectively. Additionally, 4, 9, and 29 bacterial genera were found to be shared between sediments from YP and RP, YP and GP, and GP and RP, respectively.

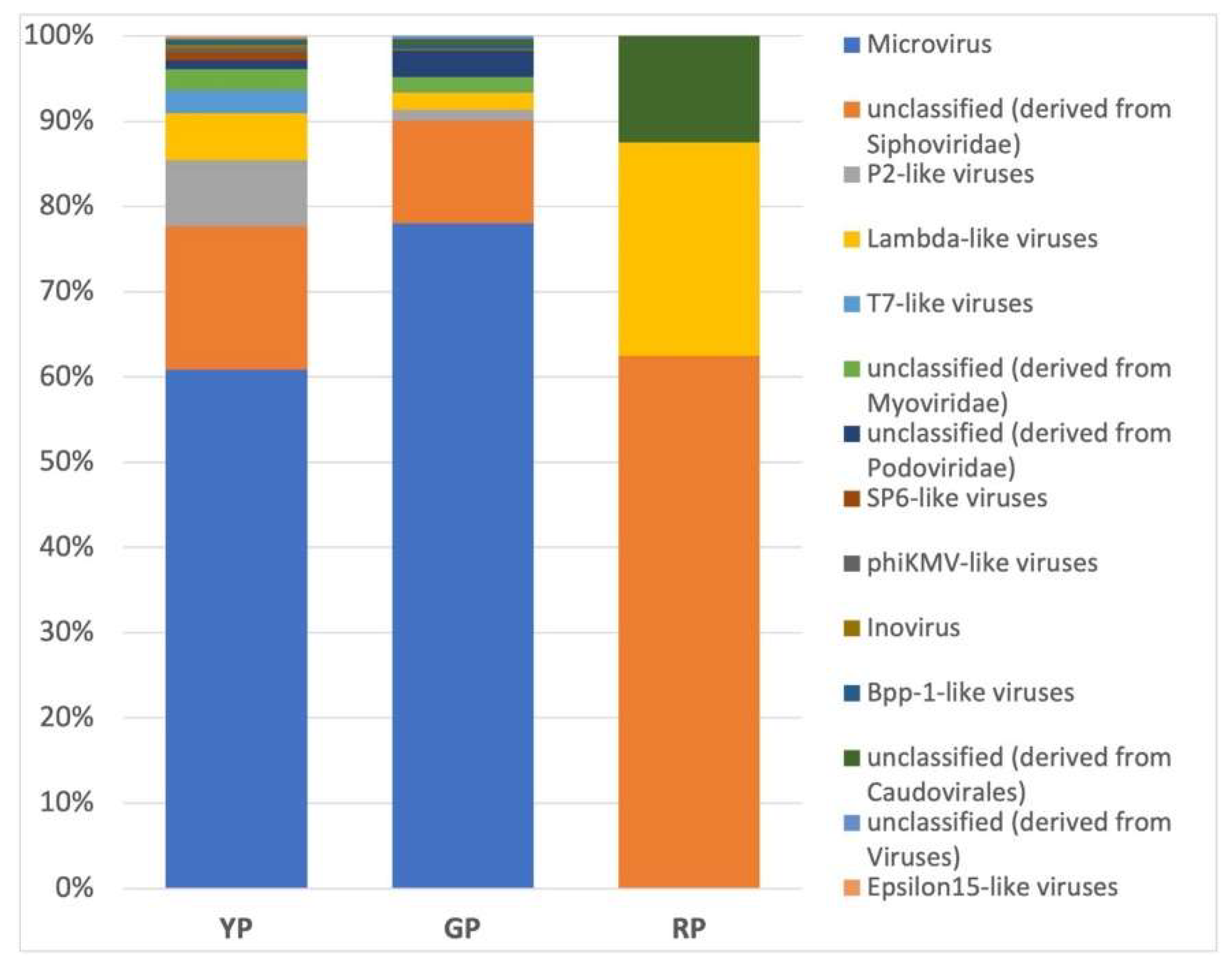

A diverse set of metagenomics sequences related to a metavirome present at the AP sediments is shown in

Figure 5. Unclassified phages derived from the Siphoviridae family were most abundant in YP and GP sediments, while P2-like viruses (family Myoviridae) were enriched in RP sediments. This is a first insight on viruses from these conspicuous hydrothermal habitats and poses questions on their molecular structure and on the interaction between Amuyo viruses and their hosts.

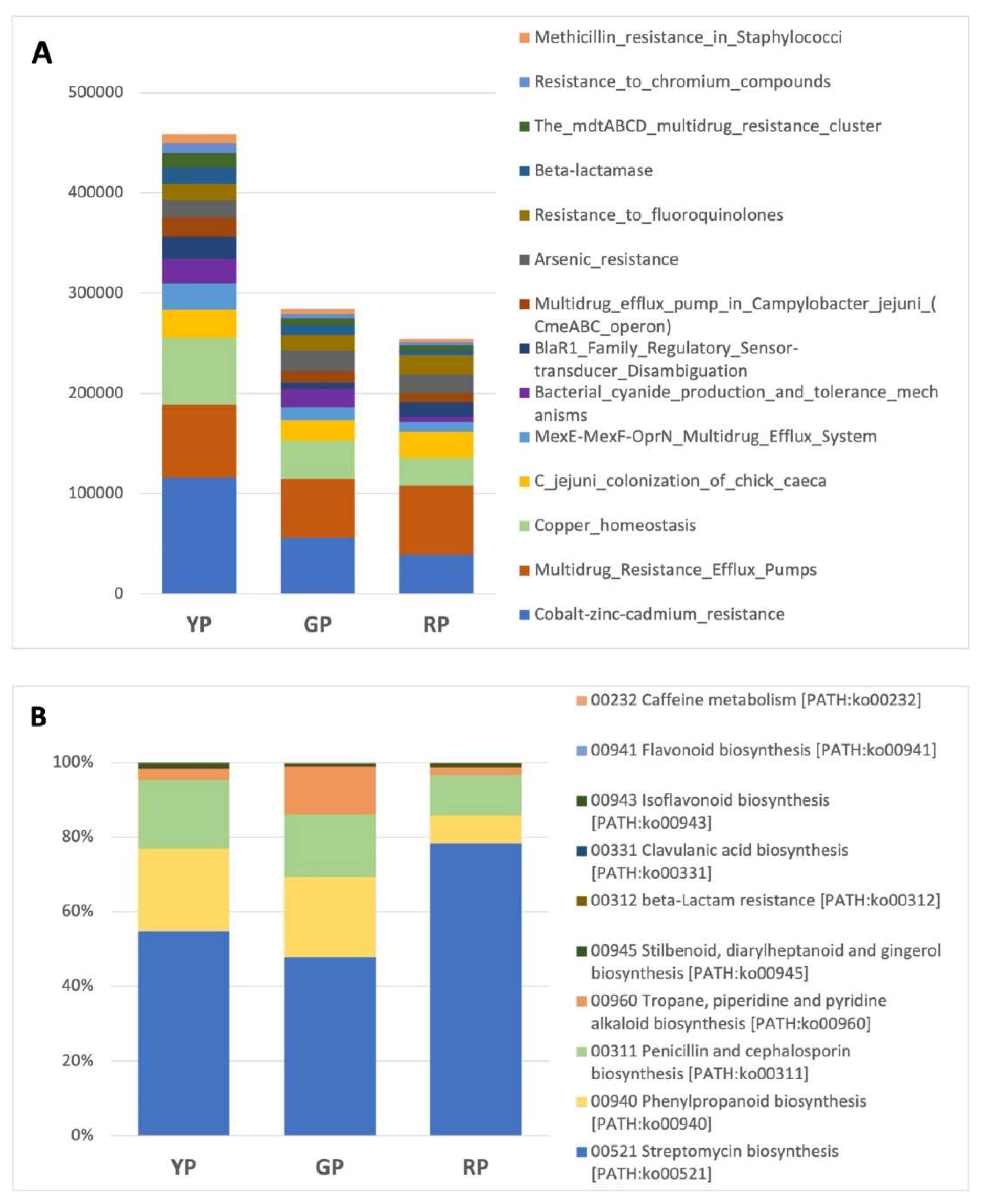

Putative metabolic capabilities were inferred from Amuyo sediment sequences (

Figure 6). RP sediments rendered a higher number of predicted functions, most probably due to its larger post QC sequences. As an example, a partial list of putative genes related to virulence and defense genes, and biosynthesis of secondary metabolites, are shown in

Figure 5A and B. Among them, genes associated to metal resistance (Zn, Hg, Co, Cd), fluoroquinolones, and to cupper homeostasis were observed. Putative genes for the biosynthesis of Streptomycin, Penicillin, and cephalosporin were also detected.

Metagenome-assembled genomes (MAG) for Amuyo sediments.

Table 3 shows thirteen constructed bacterial MAG with completeness and error percentages. Pseudomonas MAG was obtained from sequences retrieved from the three Amuyo sediments. Assembly of MAG for Stenotrophomonas, Achromobacter, and Thalassospira was achieved with sequences from YP sediments. Azoarcus MAG was reconstructed from sequences obtained at GP and RP sediments. The Bacillus MAG was prepared with sequences from YP and RP, while sequences for Anaerobacillus MAG and Aeromonas MAG came from RP and GP sediments, respectively. Most reconstructed bacterial MAGs showed over 95% completion with less than 5% error.

Also, fourteen virus MAG were assembled from Amuyo sediment sequences (

Table 4), including completeness and error percentages. MAG for Bacillus phage in YP sediments, Bacteriophage Lily plus Rhizobium phage RR1-B in GP sediments, and Circular genetic element sp. in RP sediments were identified among them. Most viral MAGs showed over 90% completion with less than 10% error.

4. Discussion

Metagenomics as a culture-independent approach provides evidence on the presence and partial identification of life forms in their habitats; also, metagenomics contributes to inform on new genetic resources, adaptive strategies, functional capabilities, biosynthetic pathways, and may allow genome reconstructions [

1,

2,

8,

22,

23].

The presence of a microbiota containing extremophiles and extreme-tolerant microorganisms has been extensively reported during the last two decades at the hyper arid Atacama Desert [

8,

18,

24,

25,

26]. Geosites (lakes, geysers, volcanoes) at high altitude in the Andes Mountains are rich in microbial life under geological, hydrochemical, climatic, and volcanic influences. The Andean Lirima hydrothermal ecosystem with reductive sediments (-250 to -3020 mV) hosts a diversity of thermophilic and anaerobic archaeal taxa, phototrophic bacteria, Firmicutes, and Gammaproteobacteria, whose composition and abundance was mostly dependent on temperature gradients; the presence of Chloroflexi as a core microbial group in this hydrothermal system suggests that photoautotrophic carbon fixation is a key process [

27]. Comparatively, this phylum is absent in Amuyo Ponds sediments. Additionally, sediments from Santa Rosa and mats from Laguna Verde, two saline lakes located over 3,700 m of altitude at the Andes Mountains, showed high differences on bacterial diversity and richness, based on pyrosequencing; Bacteroidetes and Proteobacteria phyla were most abundant and similar in both lakes, but sequences for the phylum Bacteroidetes was twice as higher in sediments than in mat samples [

28]. A similar study compared the composition of microbial communities in sediments and mats at two geothermal hot springs from Yellowstone and Iceland finding sequences related to the Archaea and Bacteria domains, including many different microorganisms, but similar community structure in both hot springs [

29]. A phylogenetic study carried out with sinter samples from El Taito Geyser Field at the Andes highlands demonstrated that Firmicutes (Bacillales plus Clostridiales orders) and Proteobacteria phyla accounted for near 70% of total bacterial reads and 22% of the total sequences were assigned to Actinobacteria, Bacteroidetes, and Cyanobacteria, while the recovered archaeal sequences were less than 2% of total sequences, including Euryarchaeota and Crenarchaeota (Halobacteria and Thermoproteia), suggesting the presence of halophilic or methanogenic/methanotrophic archaea [

30]. Thus, differences in microbial composition among aquatic systems in northern Chile stress the importance of understanding the impact of environmental factors (climate, geology, and geochemistry) on adaptive microbial strategies.

The microbial composition and diversity in geothermal aquatic systems in Atacama has been reported, e.g., Sanchez-Garcia et al. [

30], Podar et al. [

29], Muñoz-Torres et al. [

18], Valenzuela et al. [

31]. Among these polyextreme habitats in northern Chile, three colored high-altitude Andean ponds in northern Chile, the Amuyo Ponds, are an example of such geosites; they are geothermal habitats colonized by a partially explored microbiome enduring the prevailing extreme physical and chemical environmental conditions. Their waters have geothermal origins, are rich in arsenic, boron, and other dissolved salts, with drainage into Caritaya River, at the Camarones Basin. Cornejo et al. [

14] have conducted an annual, bi-monthly monitoring on the hydrogeochemistry of AP, showing stable pH (7.3-7.7), water temperatures (23-31°C), arsenic (14-19 mg L-1) and boron (300 mg L-1) contents, with Na+ and Cl- as dominant ions. Additional information on YP, RP, and GP indicated depths of 6.5, 11.0, and 3.5 m, surface temperature of 25, 24.5, and 33°C, and maximum depth temperature of 28, 57, and 33°C, respectively; positive oxidation-reduction potential (93-284 mV) was measured in all tested samples, with a reductive zone at the ponds lower sediments [

13,

14,

16,

17]. Comparatively, boron content was similar among the water and sediment samples, excepting higher boron content in RP waters; all AP sediment showed greater arsenic, Fe, Zn, Mn, and Cu concentrations than their corresponding waters samples, and nitrate was found in limited supply, from zero to micromolar concentrations [

18]. Under such geohydrochemical considerations on AP, biological information is lacking and limited to observations of amphipods and microbial mats at small saline pools around the ponds [

17]. Also, fifteen isolates were recovered from Amuyo samples [

18]: fourteen were assigned to the Proteobacteria phylum (12 at the Gammaproteobacteria and two to Alphaproteobacteria genera) and one to the Bacillota phylum (Bacilli).

Altogether, high altitude ponds, lakes, and geysers are sources of a rich microbial composition, providing multiple lines of research on microbial ecology and on the influence of geohydrochemical factors on biodiversity and evolution. In this context, Amuyo Ponds is a novel geosite worth exploring on its microbial diversity. To contribute on learning about the barely known AP microbial richness, our culture-independent approach identified Proteobacteria as the most abundant bacterial phylum in AP sediments. Sediments from YG and GP were enriched in Gammaproteobacteria, with Pseudomonas as the major genus, while genera Aeromonas and Shewanella were abundant in RP sediments, resembling the results reported by Muñoz-Torres et al. [

18] from Amuyo water samples. Then, the metagenomics approach on Amuyo sediments provided novel information: (a) on the presence of fungal genus diversity from the phyla Blastocladiomycota and Ascomycota; (b) on the virome diversity, particularly from the Siphoviridae family and P2-like viruses, opening the possibility to inquire on bacterial and archaeal host assignments and on the presence of haloviruses, among others [

32]; and (c) on the abundant presence of methanogenic archaea (Euryarchaeota phylum) in all AP sediments. .

Archaeal methanogenesis occurs in anoxic and reductive environments, and proper substrates for methane production come from anaerobic degradation of organic matter by an accompanying microflora [

33]. Both processes, methanogenesis and methanotrophy may be present at the anoxic/oxic layers of Amuyo sediments, where the presence of methanogens and the proteobacterial communities (enrichment in sequences from Archaeoglobi and Halobacteria) was confirmed by the metagenomics data. Thus, Amuyo Ponds at the Andes highlands represent a new natural model for methane budget evaluation.

Compiled information on Atacama Desert viruses provides insights on their presence, locations, abundance, diversity, and genetic complexity. Metagenomic sequences abundance of mycobacteriophages, gordoniaphages, and streptomycophages in Atacama soils showed positive correlation with the presence of their corresponding hosts [

34]. In addition, Hwang et al. [

35] have proposed a mutualistic model for host-virus interactions at the driest Atacama core where microbial cells would provide protection to viruses who in turn would supply extremotolerance genes to their hosts. It is expected that microbiome and virome at highly saline niches contain salt-adapted microorganisms and viruses [

2,

32]. Putative cyanophages and Nanohaloarchaea viruses were detected in halite samples from Salar Grande, and thirty reconstructed haloviruses genomes were lytic viruses, having dominant head-tail structures, resembling findings from other hypersaline environments [

36]. More recently, Uritskiy et al. [

26] reported the presence, diversity, and infective activity of halophilic viruses with transcriptional activity in such salt nodules; the halite virome included members of the families Myoviridae, Siphoviridae, Podoviridae and Haloviruses, and the archaeal virus families Pleolipoviridae and Sphaerolipoviridae. The viral families Siphoviridae, Myoviridae, and Podoviridae were identified in endolithic communities colonizing calcite or ignimbrite, while gypsum bear the Siphoviridae and Myoviridae families, all showing auxiliary metabolic genes; archaeal Haloviruses were only identified in the ignimbrite metagenomes [

37]. Then, diversity and genetic complexity of viromes from microbial consortia inhabiting endolithic substrates, soils, and Amuyo sediments, are now available to seek similarities and differences at niches along the Atacama Desert, allocated at distant emplacements and under different geochemical and climatic influences. .

Figure 1.

Proximity of Amuyo Ponds to Caritaya River, Camarones Basin, Region of Arica y Parinacota, in northern Chile. YP, RP, and GP correspond to yellow, red and green ponds, respectively. (Image obtained from Google Earth Pro, accessed in April 2024).

Figure 1.

Proximity of Amuyo Ponds to Caritaya River, Camarones Basin, Region of Arica y Parinacota, in northern Chile. YP, RP, and GP correspond to yellow, red and green ponds, respectively. (Image obtained from Google Earth Pro, accessed in April 2024).

Figure 2.

View of Amuyo sites where sediments were sampled at an approximate depth of 10-15 cm (A: Red Pond; B: Green Pond; C: Yellow Pond).

Figure 2.

View of Amuyo sites where sediments were sampled at an approximate depth of 10-15 cm (A: Red Pond; B: Green Pond; C: Yellow Pond).

Figure 3.

Relative abundance of classes (A.1, B.1, C.1) and genera (A.2, B.2, C.2) for Bacteria, Archaea, and Fungi, respectively, in sediments from Amuyo Ponds.

Figure 3.

Relative abundance of classes (A.1, B.1, C.1) and genera (A.2, B.2, C.2) for Bacteria, Archaea, and Fungi, respectively, in sediments from Amuyo Ponds.

Figure 4.

Venn diagram showing the distribution of bacterial genera in Amuyo Ponds sediments. A total of 813 genera were detected by metagenomic analyses, while 17, 44, and 23 genera were assigned to Yellow, Green, and Red Ponds, respectively. Shared bacterial genera were 4, 9, and 29 between Yellow and Red Ponds, Yellow and Green Ponds, and Green and Red Ponds, respectively.

Figure 4.

Venn diagram showing the distribution of bacterial genera in Amuyo Ponds sediments. A total of 813 genera were detected by metagenomic analyses, while 17, 44, and 23 genera were assigned to Yellow, Green, and Red Ponds, respectively. Shared bacterial genera were 4, 9, and 29 between Yellow and Red Ponds, Yellow and Green Ponds, and Green and Red Ponds, respectively.

Figure 5.

Relative abundance of virus genera in sediments from Amuyo Ponds.

Figure 5.

Relative abundance of virus genera in sediments from Amuyo Ponds.

Figure 6.

Presence of putative bacterial genes for virulence and defense (A) and biosynthesis of secondary metabolites (B) at Amuyo Ponds sediments.

Figure 6.

Presence of putative bacterial genes for virulence and defense (A) and biosynthesis of secondary metabolites (B) at Amuyo Ponds sediments.

Table 1.

Comparative sequencing statistics after metagenomic analyses of Amuyo Ponds sediments.

Table 1.

Comparative sequencing statistics after metagenomic analyses of Amuyo Ponds sediments.

| Pond |

Sequences post QC |

GC % |

Predicted function |

| GREEN |

23,128,825 |

57 ± 10 |

8,268,056 |

| YELLOW |

25,535,805 |

62 ± 7 |

7,424,754 |

| RED |

27,505,664 |

57 ± 12 |

10,157,651 |

Table 2.

Domain-related sequence abundance in sediments from Amuyo Ponds.

Table 2.

Domain-related sequence abundance in sediments from Amuyo Ponds.

| DOMAIN |

GREEN POND |

YELLOW POND |

RED POND |

| BACTERIA |

99,52% |

99,71% |

99,38% |

| ARCHAEA |

00,08% |

00,03% |

00,13% |

| EUKARYA |

00,28% |

00,11% |

00,26% |

| VIRUS |

00,10% |

00,11% |

00,17% |

| OTHERS |

00,05% |

00,01% |

00,07% |

Table 3.

Metagenome-assembled bacterial genomes from Amuyo Ponds sediments. .

Table 3.

Metagenome-assembled bacterial genomes from Amuyo Ponds sediments. .

| Pond |

Genus |

Completeness (%) |

Error (%) |

| Yellow |

Stenotrophomonas |

100 |

0 |

| Achromobacter |

100 |

1 |

| Pseudomonas |

95 |

2 |

| Bacillus |

98 |

2 |

| Thalassospira |

99 |

2 |

| Green |

Azoarcus |

100 |

4 |

| Pseudomonas |

100 |

6.1 |

| Aeromonas |

100 |

5 |

| Red |

Azoarcus |

100 |

4 |

| Anaerobacillus |

92 |

3 |

| Pseudomonas |

91 |

4 |

| Pseudomonas |

99 |

11 |

| Bacillus |

94 |

16 |

Table 4.

Metagenome-assembled viral genomes from Amuyo Ponds sediments. .

Table 4.

Metagenome-assembled viral genomes from Amuyo Ponds sediments. .

| Pond |

Virus |

Completeness (%) |

Error (%) |

| YP |

Bacillus phage |

101.58 |

2.07 |

| NA |

100 |

4 |

| NA |

100 |

7.78 |

| NA |

95.82 |

9.69 |

| NA |

92.68 |

8.4 |

| GP |

NA |

102.08 |

3.78 |

| Bacteriophage Lily |

100 |

5.98 |

| NA |

100 |

3.7 |

| NA |

100 |

2.7 |

| NA |

100 |

5.57 |

|

Rhizobium phage RR1-B |

90.21 |

2.16 |

| RP |

Circular genetic element sp |

100 |

8.48 |

| NA |

98.6 |

9.69 |

| NA |

90.41 |

1.29 |