1. Uncertainty in Dementia and Research

Dementia is a general term used to describe a decline in cognitive function severe enough to interfere with daily life, including but not limited to Alzheimer’s disease. Common symptoms include problems with remembering, speaking and thinking that over time progress into having difficulties with everyday activities that result in the need for dedicated care. Of a progressive nature and currently without a cure, dementia challenges society at several levels, presenting an unmet clinical need and demanding support for the communities grappling with it. (World Health Organization, 2017, Anon, 2021)

On the one hand, living with dementia has been described as “being entangled in uncertainty and isolation’’ (van Wijngaarden et al., 2018). Reaching a diagnosis is hard and the progression of the disease at the individual level, difficult to predict (Anon, 2023; Verdi et al., 2021). These feelings of uncertainty and isolation commonly result from the pressure to quickly adapt to new ways of living that can be met with a sense of lack of control (Riley, Burgener & Buckwalter, 2014; Bjørkløf et al., 2019). On the other hand, academic research is a competitive environment with pervasive uncertainty manifested in various forms, including the precariousness of grants and funding as well as job insecurity. This uncertainty can lead to feelings of inadequacy, undermining researchers’ mental wellbeing and their capacity for decision-making and task management (Butler-Rees & Robinson, 2020; Sigl, 2016). Such emotional and psychological burdens can precipitate stress, anxiety, and a sense of isolation—making a parallel of entangled uncertainty in academic and caregiving environments.

Compounding this issue is a widespread social stigma associated with expressing uncertainties, particularly in the domains of dementia caregiving and research. This stigma stems from multiple sources, including the pressure to project a facade of competence and control, guilt, and the fear of being perceived as weak or burdensome (Lawton et al., 1991; Pristavec, 2019) . As a result, valuable opportunities for support and collaboration may be overlooked, further exacerbating the challenges faced by researchers and caregivers alike. Addressing this stigma and finding strategies to manage uncertainty could yield significant benefits in career identity and, generally, life (Rosa et al., 2010; Tebb & Jivanjee, 2000) .

By fostering an environment where uncertainties can be openly discussed and shared, we pave the way for more supportive, resilient research and caregiving communities. We argue that the exchange of knowledge—where every person’s insight is regarded as equally valuable— is a pivotal element in the journey toward understanding and addressing these multifaceted challenges. It represents a systematic approach to sharing insights, research findings, and practical strategies among scientists, healthcare professionals, people with lived experience, and caregivers. This collaborative exchange fosters a deeper understanding of dementia from multiple perspectives, bridging gaps between theory and practice. Combined with participatory co-creation and creative tools, knowledge exchange initiatives can create a fertile ground for conversations around difficult issues such as uncertainty management and resilience building in non-hierarchical, safe spaces.

The Genesis of Ebb&Flow

The beginning of Ebb&Flow traces back to the Trellis:Arbor programme, an initiative designed to foster an interdisciplinary approach to creative research, and to create a physical and intellectual space for the development of meaningful artistic and academic collaborations. Artists and researchers at UCL Queen Square Institute of Neurology, UK Dementia Research Institute and UCLH National Hospital of Neurology and Neurosurgery are paired together to spark new and interesting collaborations. During the programme, artists and researchers are encouraged to form a working and creative relationship in which information and research is shared; gaining an insight into each other’s worlds and collaborating to co-create new work which explores a topic of mutual interest and the artist’s practice. The final manifestation of the working collaboration is not restricted in medium or form.

Objectives

Ebb&Flow was born from this interaction, between two dementia researchers and one artist, and set forth with several key objectives:

Create a humanspace: a safe ground to understand the experience of uncertainty experienced by the people with lived experience of dementia, carers, artists and researchers. We wanted to explore different ways of dealing with uncertainty and to exchange methodologies by co-creating honest interactive playful material and by creating meaningful ways to bring these groups together.

Foster Empathy: In our first interactions, the artist was intrigued by the lack of the researcher’s interaction with people with lived experience of the disease they investigate. The benefits of such interaction are perhaps more obvious for a clinical researcher, similar to a clinician-patient interaction, but less evident for the rally of basic scientists. Through creative collaboration, the project then set out to cultivate and re-spark empathy, enabling artists, scientists, caregivers and people with lived experience of dementia to connect emotionally, and not only intellectually, through the exploration of the presence and meaning of uncertainty in their lives.

Empower Expression: Through the reflection of our experiences, we felt that uncertainty can sometimes be met with rigidness and resistance. We were curious what it would be like to embrace it, make it visible and open a dialogue with uncertainty, exploring its potential to foster connection and flow.

We hoped that the proposed exploration of this element would have a direct impact on the individuals affected by dementia and their carers (directly or indirectly), providing a platform for voice and self-expression, challenging the silence surrounding the condition. Equally, that it would have an impact on the artist’s and researcher’s work and their environment, thereby creating spaces for interaction and connection we would collectively learn how to be empowered in uncertainty, resilience and vulnerability.

2. Participatory Co-Creation

EBB&FLOW emerged as an arts-based participatory approach aiming to foster a collaborative exchange of knowledge between artists, researchers, people with a lived experience of dementia and their carers. Our goal was to delve into the complexities of uncertainty and the challenges it presents in these three different contexts.

What we will attempt to share below is an honest version of some parts of the journey we took. Retrospectively, it is curious to see how each part and person was integral to the whole and a vital ingredient in where we ended up. Even though the methods are presented here in a linear manner, the truth of the process was everything but. We went in circles and spirals, creating and destroying almost weekly (not to say daily). Uncertainty was our collaborator, almost another living being, taking part in this project. Its ever presence was described by more than one of the advisors of the project.

By encouraging ourselves and others to give uncertainty a seat and make it a space at the table (quite a big uncomfortable one at times). And even though it was sometimes difficult, we learned to welcome it, in all its shades and pointy angles. We learned to let go of expectations and preconceived ideas, to open up to the ebbs and flow our minds to the magic of co-creation and trusting the process, which is still working our way through all of us. We just needed to learn to trust her ebbs and flows.

Purpose-Based Recruitment Process—A Participatory, Co-Created, Meaningful Space

An Advisory Group

Crucial to the essence of our project was the close collaboration with a team of eight advisors, comprising four pairs of caregivers and individuals with lived experience of dementia. From the start, it was vital that our work resonated deeply and meaningfully with the people we invited to co-create the project with. We involved these advisors right from the start, ensuring that their insights guided us in a direction that truly mattered and in a way that was accessible and mindful to the complex experience of dementia.

We initially planned to recruit two or three people to this group. To reach out to relevant networks, we contacted the Rare Dementia Support (RDS) group at University College London (UCL) which provides specialised social, emotional, and practical support for those facing rare dementia diagnoses.. They included a recruitment call in their communications to the members. We also filmed a short video of 10 minutes explaining the project, which was projected in their support group sessions. Lastly, we were invited to present the project at one in-person carers meeting held in London. We created a dedicated e-mail address for the project and also provided a phone number they could call to.

Four pairs of people with lived experience and their primary caregivers (in this case, their partners) reached out. We held an informative session, after which they all expressed their wish to participate in the project. This was many more than we had imagined but each voice felt important so we adapted the project to accommodate all eight. We budgeted an honorarium fee of £100 for their time commitment, which was paid out at the end of the project on their request as vouchers.

Through monthly virtual meetings designed around the principles of co-creation and participatory sense-making (De Jaegher & Di Paolo, 2007), we sought to understand their experiences and perspectives, crafting a project that was not only informed but actively shaped by those who lived with dementia every day.

People with Lived Experience of Dementia

Besides the advisory group, we also visited an RDS support group over the course of the project. We conducted three visits with this group, roughly timed to the beginning, middle, and end of the Ebb&Flow commission. Besides recruiting participants in the project, we used these opportunities to share the evolution of the project and to gather feedback. In each of these meetings we actively participated in the sessions, experiencing firsthand the impact and importance of these communities.

Recruitment of Researchers

The participation of researchers in this project was one of the main pillars and motivations for the inception of EBB&FLOW. To reach out to scientists, we used word-of-mouth to our own networks within the Institute of Neurology. We also publicised the project over seminars and departmental meetings we attended, and shared a dedicated recruitment call for researchers in social networks including Instagram, LinkedIn and private Microsoft Teams groups.

Recruitment of Artists

As a science-art collaboration, the artistic contributions to our project were brought to life by a number of artists, who shared an interest in exploring the theme of uncertainty which is inherently embedded in arts practice. These artists, recruited through personal networks and online platforms including Instagram, contributed their unique perspective, adding a depth and richness to our collective community

The essence of this transdisciplinary(Galvin, Valois & Zweig, 2014) project was to facilitate a richer dialogue between all parts, making the invisible interconnectedness visible through the network of community and shared experience in addressing the challenges of dementia. Ultimately, we wished to foster a space for connection, understanding, and support.

Thirty-eight participants joined EBB&FLOW, with different levels of involvement in the project. We imagined these as layers forming a ripple, expanding from the centre core team to the edges the wider audience that we hoped the project could end up reaching (see

Figure 1).

In total, we held approximately 10 virtual meetings and 2 in-person meetings. During these, we would start having a quick check-in with everyone. Followed by a creative invitation to share. Then, we would update the team with the progress in the project and future directions. We would open the conversation to receive feedback and other comments or ideas. We summarised the key takeaway points to address and scheduled a new session for a month later.

The smallest ripple was us three. Then immediately after, a bigger ripple containing the advisory group. Some of the participants seemed more acquainted with research methods and/or co-creation of a project. Others felt more adrift. In feedback gathered after the end of the project, one of the carers in the group commented on how being part of this activity was a way to gain confidence:

“For me, someone whose lack of experience is quite overwhelming at times has frequently held me back from trying so many things. I like to be given clear and strict instructions to follow. I felt completely adrift. What had I said yes to? (...) Over three months I learnt not to be afraid of the unknown.”

One of the couples in the advisory group commented on the value of self-expression and how the project created an outlet to open up conversations about their situation with other people who were not engaging in conversations about their experience with dementia before:

“Helped to articulate the thoughts we were living in—made it more open…”

The advisors were active co-creators of the projects, having an important influence on how the project was designed. They were particularly influential in guiding the elements of the project that we present below and enabled us to understand that the invitation needed to be accessible and easy to achieve with and on a phone. They also requested a mixture of online and in person opportunities and invited exploration of the value of words and images as means of expression.

3. Harvesting the Space: Outcomes and Reflections

Figure 2.

Flowchart summarising the stages of the project, activities and who was involved.

Figure 2.

Flowchart summarising the stages of the project, activities and who was involved.

The Log

In Ebb&Flow, we used the sea as a metaphor for uncertainty. A timeless symbol of the unknown, the sea not only symbolises uncertainty due to its vast, unpredictable nature and the dangers it presents, but it also embodies a sense of awe and opens a realm of endless possibilities. This duality mirrors the human experience where uncertainty, though often daunting, also brings the exhilaration of limitless possibilities and the chance for exploration and growth.

All 38 participants were invited into a WhatsApp community, where each member had a private chat with the core team, their personal ‘logbook’. This logbook concept drew inspiration from mariners who chronicle their daily sea voyages. In this digital logbook, participants were encouraged to record entries weekly reflecting their experiences of uncertainty over the course of three months.

To encourage this reflection and report in a creative manner, we created a community group chat where participants could receive notifications, but only we as administrators could post messages.

Every week, on Thursdays at 12:01, the melody of the shipping forecast was broadcasted, accompanied by a collection of words used in the shipping forecast (see

Figure 3) to communicate the weather conditions. Participants were invited to submit an image, audio or video and to pair with their selected words or a short piece of writing. This practice aimed to encourage and aid participants to express themselves through the use of metaphor using language typically reserved for weather forecasting. Metaphors serve as powerful tools for expression and communication, helping individuals to articulate complex emotions and ideas in a more relatable and vivid manner. They bridge abstract concepts with familiar experiences, enhancing understanding and emotional connection (Thibodeau, Matlock & Flusberg, 2019). As Ellen Y Siegelman writes in

Metaphor and meaning in Psychotherapy: “‘What gives metaphor its usefulness is the possibility of bridging or generalising so that thought can cover a larger domain than originally. But what gives metaphor its vividness and resonance is its connection with the world of sensed and felt experience” (Siegelman, 1993).

One of the advisors shared how the process of choosing words enabled her for the first time to assess how her husband was really feeling and to begin to understand that he was at times more content than she imagined him to be.

“I printed out the list of words which had been sent to my WhatsApp. I showed the list to Ian and asked if there were any words, which summed up his mood. After slow consideration, he said good, smooth, rising. Calm. I absolutely couldn’t believe it. I was staggered and so happy”

Since the project was happening mostly online and was a self-directed task, the advisors suggested that a

daily prompt would support a feeling of being interconnected and part of a whole for the duration of the project, as well as a gentle reminder to record in their logbooks. In the administrator-run chat, we circulated a curated selection of evocative daily prompts in the form of images and short texts sourced from art archives, art and science studies, literature and music. Some examples of these prompts can be seen in

Figure 4.

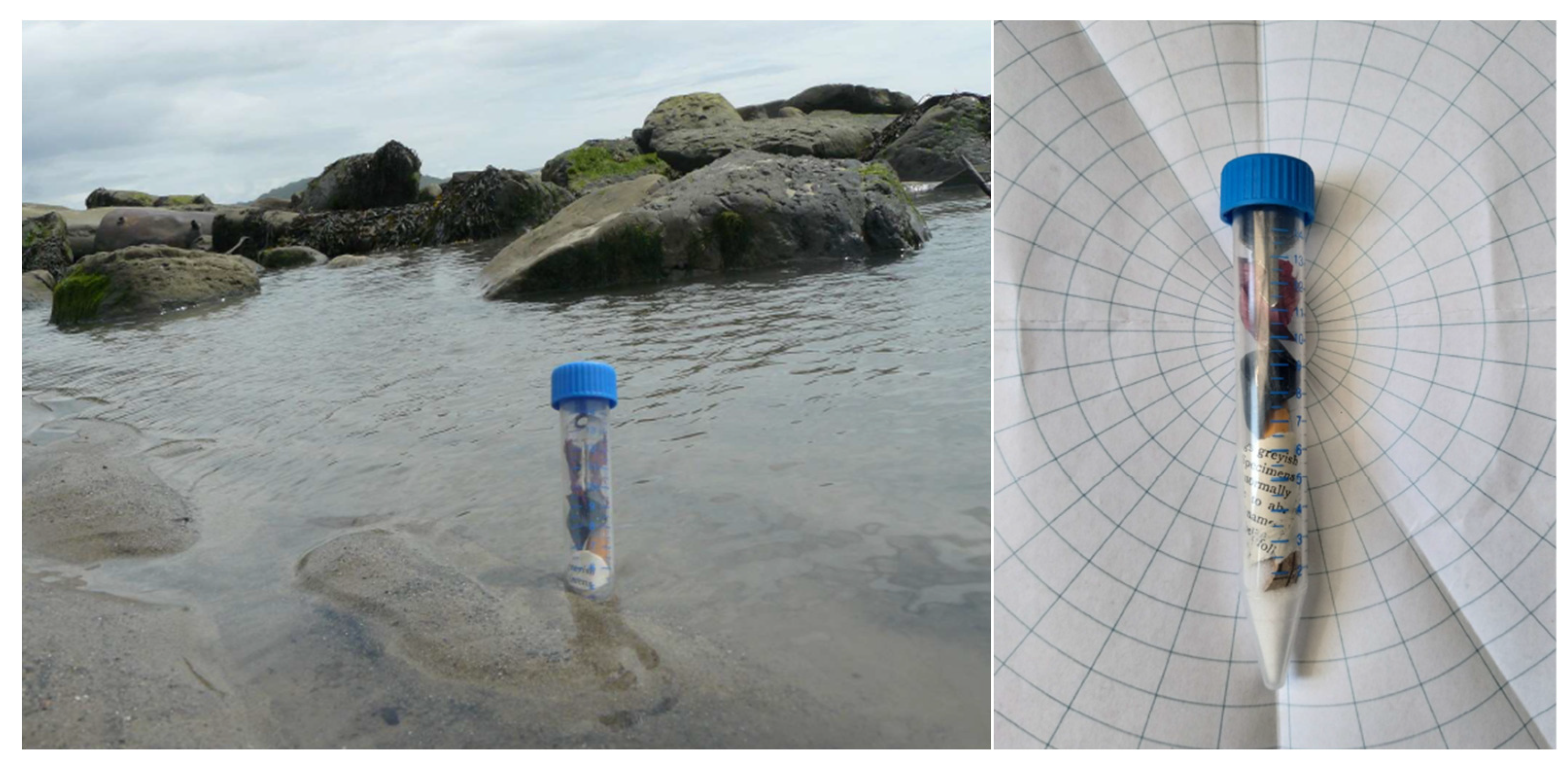

Each month the log book was live when participants received a package through mail (see

Figure 5). These parcels contained materials intended to enrich their involvement and foster deeper connections with the themes explored in their logbooks. Sourced from everyday life, the artists’ studio and the laboratory, they allowed us to represent the intersections of these different worlds in a material way. Some examples of these materials were jay cloths, petri dishes, pipettes, pigments, paper boats, circuit boards, test tubes, string, soap bubbles and dice.

The daily prompts and parcels had a significant impact on some of the participants. We can see examples of this in the feedback we received (see an example below), including specific entries inspired by our daily prompts (

Figure 6) and a particular creation by one of the advisors using the physical materials sent in the mail (

Figure 7). However, other participants did not respond to the prompts directly or use the materials provided in the parcels. Participation in these activities was not mandatory, reflecting different levels of engagement and interaction with the project.

“The first images I created were inspired by some, uh, pictures sent out by the project team, which were of some various sort of artists working on a beach with sculptures of, uh, sort of sea creatures. And that inspired me to use that as the input into the artificial intelligence program to generate some new images.”

“Mysterious figures on the beach. How do we make sense of a picture or life where the meaning is obscure. What are the people doing there, is this a dream? Am I in the picture or am I the observer, passive in the face of this strangeness There is an unstated tension rasping at very being, tearing at every fibre I struggle to understand and make sense of it all”

Thematic Analysis

In the final phase of our project, we aimed to integrate quantitative methods with qualitative insights by conducting a thematic analysis of all the word entries from participants. The themes were identified through a combination of methods: inductive, where themes were interpreted directly from the text; deductive, involving predefined themes based on prior knowledge, such as expected descriptions of dementia symptoms from people with lived experience; semantic, which involved the literal evaluation of the text; and latent, which focused on analysing the subtext and implicit meanings. Here, we summarise the main themes and provide examples of entries for each category.

Everyday uncertainty. This theme encompasses self-reflection, sharing overwhelming feelings, contentment, excitement, and reflections on one’s ability to predict and react to future uncertainties.

“How to hold

Too much information

When it’s an unwieldy liquid

Seeping it’s own logic through the strata of porous beings who are already 70% water”

“Today I am afloat, enjoying the gentle breeze and the light summer rain following a turbulent yet rewarding spell. I see days of tranquil waters and gentle light ahead”

- 2.

How Dementia Manifests, including the increasing difficulty of everyday activities with the onset of dementia, feelings of isolation related to caregiving, guilt during care-free moments, and uncertainty about predicting and reacting to future events. It features poetic descriptions of dementia symptoms (memory loss, confusion, speech impairment) and the caregiver’s emotions (patience, compassion).

“The tide has tumbled and tossed all his thoughts randomly along the shoreline of today. Tomorrow another tide will throw them up into a different pattern, where we must gather them up to untangle the threads, with patience and understanding”

- 3.

Uncertainty in Academic Research. This theme covers concerns about experiments, funding, career prospects, and manuscripts, feelings of being unproductive or lost due to excessive focus on minor details, and reflections on the opportunities brought by.

“The calm and lightness of getting a piece of work finished and submitted is a nice moment of reflection. But accompanied by uncertainty because the future of the work is now in others hands…”

- 4.

Coping Mechanisms. This category highlights strategies such as keeping the big picture in mind, valuing small actions, interactions with pets, and taking time off.

“The ripple effects of small things can be extraordinary”

“... just roll with the flow wherever it goes even if it rolls out of here.”

- 5.

Self-Reflection, including descriptions of space and behaviours, explaining emotional states using metaphorical language.

“Time slowly unfolding -shapes and shadows that come and go—my “ebb and flow” The stillness of movement -the silence of the roar!”

“Slowly and steadily without force the accordion gently begins its maiden rise and fall.”

“I dreamt.

My dreams always ask myself what I’m doing with my life and why I’m so unhappy

And then I wake up feeling fine and full up with fun things to do

Afloat in a wash of wishes”

“We are as one with the sea. We have our moments of calm and our storms. Like us the sea can be angry and destructive, wild and yet beautiful. Pleasant and calming. We are as one with the sea.”

The semantic analysis of

Figure 8, based on this thematic coding, reveals that the most common words were related to the sea, as well as concepts of time, feelings, and the future (notice the outstanding frequency of the auxiliary verb to indicate future tense “will”). This observation is intriguing because it suggests that participants did frequently use sea metaphors to articulate their thoughts and emotions. Additionally, there is a significant expression of uncertainty about the future. Interestingly, the sentiment score analysis indicates a skew towards positive words rather than negative ones, suggesting an overall positive sentiment trend to uncertainty, which might be contrary to initial expectations. The sentiment scores were calculated using the TextBlob library, which assigns a polarity score to each text entry ranging from -1 (very negative) to 1 (very positive), based on the presence and context of positive and negative words. While these analyses are not intended to be robust scientific evaluations, they represent a curious and playful use of research methodologies, providing an interesting perspective on participants’ reflections and emotional expressions in their logbook entries.

The Card Deck

In an effort to transform and share the materials gathered over the three-month period into a dynamic, interactive experience, we envisioned the creation of a collaborative card deck. The idea was to co-create a resource that could be used by all participants and a wider audience to inspire conversations surrounding uncertainty, drawing inspiration from innovative card decks like those from The School of Life and others such as artist’s Brian Eno and Peter Schmidt’s Oblique Strategies. Lucy the artist on the project has a deep fascination with cards and uses them a lot in her creative and therapeutic practice. Exploring their potential to open up alternative ways of thinking and feeling. She has a personal collection of artist decks and has made decks previously in her collaborative work. Card decks have previously demonstrated significant effectiveness in cognitive-behavioural therapy (Almeida et al., 2023), and as conversational tools for patients in palliative care, facilitating communication between patients and medical staff (Olsson Möller et al., 2022). Our aspiration was that this card deck would not only serve as an engaging tool but also as a meaningful platform for individuals to connect, share, and reflect on their unique experiences with uncertainty

The development process—Ossa printing with advisors

To develop the aesthetic of our card deck, we organised a collaborative session at the Ossa Prints studio in October 2023. This event brought together our advisors and team members for an immersive experience in the art of printing. It offered a unique opportunity for everyone to meet in person, engage with the letterpress printing process, and interact with the words and themes that had been central to our project (see

Figure 9 for some examples of the process).

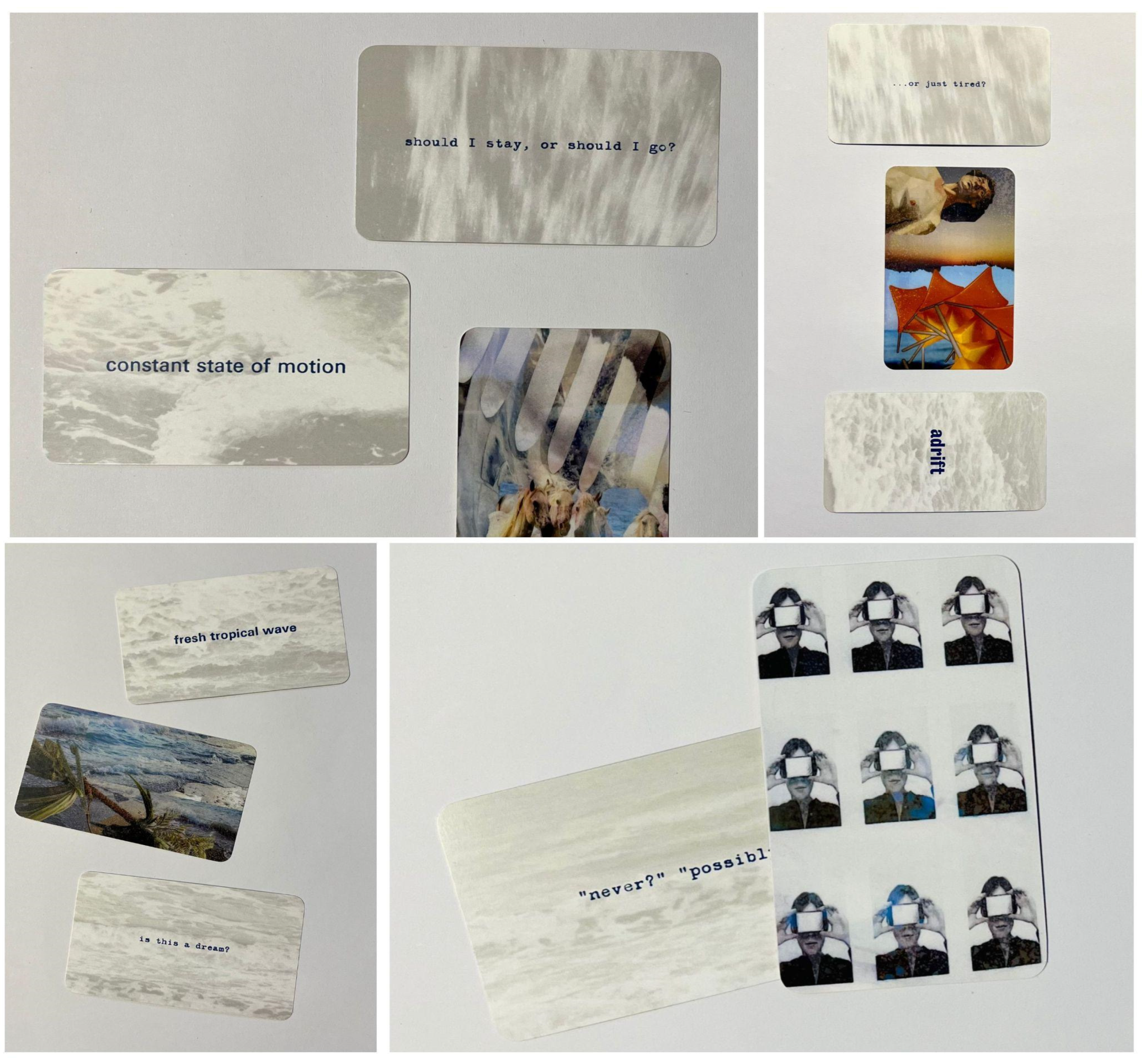

The resulting card deck. Over the course of the three-month journey, we amassed a diverse collection of contributions, including text entries, photographs, and videos. In collaboration with Ossa Prints, we decided to create two distinct card decks: one featuring words and the other showcasing images. Included in the card deck set was a triangular dice and a pamphlet, the latter providing detailed information about the project and the significance of the elements within the card decks. This thoughtful combination of words, images, and interactive components was designed to enhance the experience of exploring and discussing the themes central to our project.

One of the beautiful outcomes of this day was from one of our advisors who experiences Posterior Cortical Atrophy, a rare dementia that affects spatial orientation, as part of their condition. As she placed the letters in the print press they became jumbled. The result was the perfect front cover for the bag for the deck and something we could not have foreseen or imagined. See

Figure 10 for an image of the card deck at a glance.

The Card Deck in Action

Our card deck was brought to life in an interactive session at St. George’s. Participants engaged in the game at the end of their meeting, which fostered meaningful conversations and connections. We also use the card deck all together at the final event explained below, where attendees experienced them for the first time in person. This session highlighted the deck’s potential as a tool for dialogue and reflection in a group setting.

We have received informal feedback from participants of the project of their experience with the card deck:

“I played the deck with my partner and it asked us so many questions, mostly about how often image, text and emotion mis-register. We also treated it like our own tarot deck. Usually I am quite sceptical of tarot, even though I enjoy it, but working with a language/cosmology that we didn’t already know made us more poetic and abstract, so it was more of a prompt to talk.”

“As a scientist, I’ve found myself grappling with the uncertainties of daily life, often reaching for three cards in the evening.”

In

Figure 11, a few example of card deck throws are shown.

Final Exhibition and Sharing Event

To culminate the year’s project, we planned a collaborative sharing event, to be hosted in UCL. This gathering was designed to celebrate and showcase the rich tapestry of inspirations and experiences gathered throughout the year. Rather than an exhibition, our intention was to create a space where the creative, insightful and personal journeys of all participants could be shared, appreciated, and reflected upon. We wanted to highlight the process rather than the card deck as a material outcome of the project.

Figure 12.

The card deck in use at the final event.

Figure 12.

The card deck in use at the final event.

The culmination event marked the end of our transformative journey with the Ebb&Flow project. This event was not only a celebration but also an integral part of our research outcomes, providing a platform for participants to share and reflect on their experiences.

Overview of the Event

The event commenced with a segment dedicated to the genesis of the Ebb&Flow project. This part of the program, titled “Origin Tales,” offered attendees an in-depth look into the initial conceptualization and developmental phases of the project. It highlighted the journey from the initial idea to the creation of the card deck, underscoring the transformative nature of this endeavour and how embracing uncertainty was embedded in the process from the start.

Following the opening segment, the event transitioned into “Shared Narratives.” This was a crucial aspect of the results, as participants who had been part of the Ebb&Flow journey shared their personal experiences. They recounted their involvement in the project, the impact it had on them, and presented some of the artworks that were a direct result of their participation. This session provided valuable insights into the effectiveness and impact of the project on its participants.

“Over three months I learnt not to be afraid of the unknown.”

Uncharted territory

What’s coming up?

Are we prepared?

How do we prepare?

Can we ever be prepared?

The event concluded with a social gathering. This part of the event was characterised by an informal setting with refreshments, facilitating open conversations among participants, researchers, and guests. This session was intended to be a celebration of the successful completion of the project and to serve as an opportunity for people to meet in person, share experiences and feedback, enriching our understanding of the project’s impact. After three months sharing online together, finally being in person was hugely emotional. The sense of connectedness that had webbed between us all was palpable. The depth of the sharing, the shared human difficulties, the gratefulness of the space. We were there, together, and that was what mattered at that moment.

This project did not end in this event, its tentacles keep weaving their way through the participants. For example one of the advisors has taken on the challenge of turning the images and text from the decks into a quilt; another person who attended the event has feedback that they have been using the cards in the work in care homes; one of the artists shared this with us.

I played the deck with my partner and it asked us so many questions, mostly about how often image, text and emotion mis-register. We also treated it like our own tarot deck. Usually I am quite sceptical of tarot, even though I enjoy it, but working with a language/cosmology that we didn’t already know made us more poetic and abstract, so it was more of a prompt to talk.

4. Final Insights: Navigating Uncertainty Together

Ebb&Flow was a year-long knowledge exchange project part of the Trellis:Arbor initiative at University College London. The Trellis:Arbor commission paired artists and researchers, bringing numerous benefits on multiple levels. For the institution, this enhances its relationship with the community and fulfils its responsibility to communicate and engage with the public, especially when traditional channels might not be the most effective. For researchers, it provided an opportunity to creatively explore their subjects beyond technical expertise. Engaging in creative activities has been shown to positively impact researchers’ well-being, productivity, engagement, and motivation. It is important to note that researchers often face mental health issues, and engaging in creative activities and meaningful dialogues beyond the academic environment can be beneficial (Leckey, 2011; Shukla et al., n.d.; Ozbay et al., 2007)

In particular, Ebb&Flow responded to the challenges posed by the role of uncertainty into the careers and lives of creatives, scientists and people with lived experience of dementia. We created a project focused on creating, caring and giving visibility to the process of not knowing what is going to happen next—how will we shape our careers, if our experiments are going to work, what is the next stage of the disease, how will I take care of my lover’s needs.

We used the popular idiom ebb and flow to name the project. It alludes to the movement of the tides, borrowed to describe constant fluctuations in life. When searched for synonyms, uncertainty mostly returns adjectives with negative connotations: concern, confusion, ambiguity, ambivalence and anxiety come up as strong matches. The next synonyms include words such as mystification. Defined as a state of doubt about the future, or about what is the right thing to do, it might seem fitting to attach to the word a ghastly feeling. Yet, ebb and flow also alludes to something that changes in a regular and repeated way. Being fluctuating the constant, repeating itself to infinity, what keeps us from feeling grounded in the certainty of its existence? The sea embodies a sense of awe and a realm of endless possibilities which we found fitting to challenge to usual discourse on uncertainty. Just as the open sea stretches beyond the horizon, offering a multitude of paths and discoveries, uncertainty in life opens the door to numerous opportunities and potential.

With its inherent presence in all research processes, being it in a creative or a scientific industry, what is the role of mystification in the day-to-day activities of the ones who perform research? and who are these researchers—is there a meaningful difference to draw in the human experience of uncertainty between a life science researcher or an artist? What about the ecologies constructed around a diagnosis of dementia?

With Ebb&Flow, we aimed to create exploratory grounds of creativity without a utilitarian lens, emphasising that creativity for its own sake is valuable. Serendipitously, we found that an alternative creative approach to research can be highly beneficial. For instance, we found that the forecast words helped one carer understand the emotions of their partner diagnosed with dementia, which were not apparent and had caused anxiety and stress. By choosing words linked to positive emotions, they felt relieved and reduced their anxiety about their partner’s apparent inner turmoil. We believe that creating meaningful exchanges between researchers and people living with or affected by dementia increases awareness of the disease’s experience and the research being conducted. These exchanges can be emotionally powerful, motivate interest in research, and inspire researchers to push toward their goals.

A key finding from our work is the undeniable importance of personal expression in both the study and care of dementia. During our project we saw that allowing space for personal stories and artistic expression lead to deeper empathy and understanding. This aspect of the project was particularly powerful, revealing how personal narratives can illuminate the often-overshadowed subjective experiences of those living with dementia.

We particularly highlight the role of support groups such as Rare Dementia Support in providing access to public engagement and involvement activities, creating a needed bridge between the higher education institution and the communities it serves. Their participation also underscored the invaluable role that such support groups play in enhancing the lives of patients and their families.

As we continue to explore and implement knowledge exchange and co-creation initiatives, it becomes increasingly clear that these approaches hold significant potential to transform our understanding and management of dementia. By fostering an environment where uncertainty is acknowledged and shared experiences are valued, we can cultivate resilience, inspire innovation, and move closer to a future where the impact of dementia on individuals and society is minimised. Through these collaborative efforts, we not only enhance the quality of care and support for those affected by dementia but also contribute to the broader goal of finding effective treatments and exploring ways to live well with dementia by challenging stereotypes

As researchers many times we are working in our ‘workshop’, excluded from reality and the lived experience of the real world. We look at cell cultures, or numbers on a screen, forgetting that behind those, there are real life stories, there are emotions, suffering, joy, there is a face and love and grief surrounding every one of these abstractions we see in the lab. Engagement in this project brought us closer to the realities of dementia. This closeness enriched our understanding and provided a nuanced perspective of the condition. We experienced firsthand the complexities and challenges faced by individuals with dementia, which has been instrumental in shaping our approach to future dementia research. Lack of confidence and self-reflection might represent roadblocks to dealing with uncertainty in research. In our experience, participating in these sorts of projects can build resilience in the researcher by providing a safe space to explore such feelings, finding support and finding routines or tools to provide emotional control. Equally, co-creation projects like Ebb&Flow can challenge the common idea of researchers as strange people in white lab coats that are somehow in another sphere and impossible to reach and talk to. We wanted to bring that bridge closer, to all be a part of the same project, to bring us both down to the real work, to Earth.

From an artistic perspective, this project was an exploration into what can be opened by working at the intersection of art, science and lived experience. The artistic process allowed for a creative exploration of diverse experiences, offering space for expression and understanding. highlighted the potential of art as a powerful tool for communication and empathy—a safe space for experiencing uncertainty, in something that does not have the consequences of other actions in common life, might open up possibilities for other rituals, views, stories to be inspired by.

Participant feedback was mostly positive and insightful. Many expressed that the project provided them with a valuable outlet for expression and connection. Particularly from carers sharing how it supported them to really understand how their partner felt and to offer an alternative voice.

Ebb&Flow offered visibility to processes of dealing otherwise often overlooked or lived in silence. By placing them in the centre, any feeling was valued as equal to any other more commonly accepted feelings. By sharing them in a collective centre, opening the personal to the communal acted as a step out of a comfort zone that might not be as comfortable any longer. A chance to dare and find commonalities, or otherwise be challenged into different ways of working.

A remarkable aspect of this project was the immense amount of love and care observed and experienced within the dementia community. This observation is not just heartwarming but also an essential component of understanding and supporting those with dementia. It speaks to the need for compassionate approaches in both research and care, emphasising that beyond scientific understanding, the human element remains central to effectively addressing dementia.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the invaluable collaboration with Ossa Prints for their collaboration on the card deck, and to Nicolas Franky and Tommaso Olivero for their support. We are deeply thankful to our advisors for their unwavering support, guidance, creativity, and contributions to the logbooks: Alison Gilderdale, Charlie Gilderdale, Caroline Russell, Ian Russell, Dianne Turner, Ian Turner, Linda Watts, and Stephen Watts. We extend our heartfelt thanks to all the artists, researchers, individuals with lived experience of dementia, and carers who contributed to the logbooks. We also acknowledge the other supporters who helped us along the way, including Rare Dementia Support Groups, Nikki Zimmermann & The St George’s YOD Support Group, Seb Crutch, Emilie Brotherhood, Olivia Wood & The RDS Focus Group, Zoe Maxwell, and all the attendees who shared with us. Lastly, we would like to recognize that Ebb&Flow was a UCL Trellis Arbor Commission 2023.

References

- Almeida, V.P. de, Oliveira, M.S. de, Moraes, A. dos S., Padovani, R. da C. & Caranti, D.A. (2023) Healthy Lifestyle Deck of cards as a tool for cognitive-behavioral therapy in adults with obesity. Estudos de Psicologia (Campinas). 40, e210162. [CrossRef]

- Anon (2023) How to get a dementia diagnosis. 18 August 2023. nhs.uk. https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/dementia/symptoms-and-diagnosis/diagnosis/ [Accessed: 15 June 2024].

- Anon (2021) The progression, signs and stages of dementia | Alzheimer’s Society. 24 February 2021. https://www.alzheimers.org.uk/about-dementia/symptoms-and-diagnosis/how-dementia-progresses/progression-stages-dementia [Accessed: 15 June 2024].

- Bjørkløf, G.H., Helvik, A.-S., Ibsen, T.L., Telenius, E.W., Grov, E.K. & Eriksen, S. (2019) Balancing the struggle to live with dementia: a systematic meta-synthesis of coping. BMC Geriatrics. 19, 295. [CrossRef]

- Butler-Rees, A. & Robinson, N. (2020) Encountering precarity, uncertainty and everyday anxiety as part of the postgraduate research journey. Emotion, Space and Society. 37, 100743. [CrossRef]

- De Jaegher, H. & Di Paolo, E. (2007) Participatory sense-making. Phenomenology and the Cognitive Sciences. 6 (4), 485–507. [CrossRef]

- Galvin, J.E., Valois, L. & Zweig, Y. (2014) Collaborative Transdisciplinary Team Approach for Dementia Care. Neurodegenerative Disease Management. 4 (6), 455–469. [CrossRef]

- Lawton, M.P., Moss, M., Kleban, M.H., Glicksman, A. & Rovine, M. (1991) A two-factor model of caregiving appraisal and psychological well-being. Journal of Gerontology. 46 (4), P181-189. [CrossRef]

- Leckey, J. (2011) The therapeutic effectiveness of creative activities on mental well-being: a systematic review of the literature. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing. 18 (6), 501–509. [CrossRef]

- Olsson Möller, U., Beck, I., Fürst, C.J. & H Rasmussen, B. (2022) A Reduced Deck of Conversation Cards of Wishes and Priorities of Patients in Palliative Care. Journal of hospice and palliative nursing: JHPN: the official journal of the Hospice and Palliative Nurses Association. 24 (3), 175–180. [CrossRef]

- Ozbay, F., Johnson, D.C., Dimoulas, E., Morgan, C.A., Charney, D. & Southwick, S. (2007) Social Support and Resilience to Stress. Psychiatry (Edgmont). 4 (5), 35–40.

- Pristavec, T. (2019) The Burden and Benefits of Caregiving: A Latent Class Analysis. The Gerontologist. 59 (6), 1078–1091. [CrossRef]

- Riley, R.J., Burgener, S. & Buckwalter, K.C. (2014) Anxiety and Stigma in Dementia: A Threat to Aging in Place. The Nursing clinics of North America. 49 (2), 213–231. [CrossRef]

- Rosa, E., Lussignoli, G., Sabbatini, F., Chiappa, A., Cesare, S.D., Lamanna, L. & Zanetti, O. (2010) Needs of caregivers of the patients with dementia. Archives of gerontology and geriatrics. 51 1, 54–58. [CrossRef]

- Shukla, A., Choudhari, S.G., Gaidhane, A.M. & Quazi Syed, Z. (n.d.) Role of Art Therapy in the Promotion of Mental Health: A Critical Review. Cureus. 14 (8), e28026. [CrossRef]

- Siegelman, E.Y. (1993) Google-Books-ID: 1iAVHW7axY0C. Metaphor and Meaning in Psychotherapy. Guilford Press.

- Sigl, L. (2016) On the Tacit Governance of Research by Uncertainty: How Early Stage Researchers Contribute to the Governance of Life Science Research. Science, Technology, & Human Values. 41 (3), 347–374. [CrossRef]

- Tebb, S. & Jivanjee, P. (2000) Caregiver Isolation: An Ecological Model. Journal of Gerontological Social Work. 34 (2), 51–72. [CrossRef]

- Thibodeau, P.H., Matlock, T. & Flusberg, S.J. (2019) The role of metaphor in communication and thought. Language and Linguistics Compass. 13 (5), e12327. [CrossRef]

- Verdi, S., Marquand, A.F., Schott, J.M. & Cole, J.H. (2021) Beyond the average patient: how neuroimaging models can address heterogeneity in dementia. Brain. 144 (10), 2946–2953. [CrossRef]

- van Wijngaarden, E., van der Wedden, H., Henning, Z., Komen, R. & The, A.-M. (2018) Entangled in uncertainty: The experience of living with dementia from the perspective of family caregivers. PloS One. 13 (6), e0198034. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization (2017) Global action plan on the public health response to dementia 2017–2025. Geneva, World Health Organization. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/259615.

Figure 1.

Schematic representing the organisation of EBB&FLOW into several layers expanding from the most involved (core team of the commission and the advisory group) to the participants in the EBB&FLOW activities, including the Rare Dementia Support groups we interacted with to play with the concepts of the project and gather feedback (“Support groups”), the researchers, artists and people living with dementia (PLwD) that participated throughout and ending with the wider reach of the project and its legacy. Photo credit: Travis Leery from Unsplash.

Figure 1.

Schematic representing the organisation of EBB&FLOW into several layers expanding from the most involved (core team of the commission and the advisory group) to the participants in the EBB&FLOW activities, including the Rare Dementia Support groups we interacted with to play with the concepts of the project and gather feedback (“Support groups”), the researchers, artists and people living with dementia (PLwD) that participated throughout and ending with the wider reach of the project and its legacy. Photo credit: Travis Leery from Unsplash.

Figure 3.

Collection of words sourced from weather and shipping forecasts used as prompts for the Ebb&Flow log activity.

Figure 3.

Collection of words sourced from weather and shipping forecasts used as prompts for the Ebb&Flow log activity.

Figure 4.

Screenshots of the Community Logbook—Examples of daily prompts.

Figure 4.

Screenshots of the Community Logbook—Examples of daily prompts.

Figure 5.

Monthly parcels we sent to the participants.

Figure 5.

Monthly parcels we sent to the participants.

Figure 6.

A) Daily prompt in WhatsApp community displaying Heidi Bucher’s son Mayo and husband, Carl Bucher, activating the Bodyshell sculptures Poma and Frilla (1972, extracted from book Heidi Bucher: Metamorphosis). B) Image generated by participant of the logbook in response to the daily prompt in A using a generative AI tool. “(...) it seemed to fit with the whole idea of caring for someone and the help you get is very limited from the state. So you are on your own. So it felt like you could easily represent that (...) with people wandering on a sort of desolated beach.”

Figure 6.

A) Daily prompt in WhatsApp community displaying Heidi Bucher’s son Mayo and husband, Carl Bucher, activating the Bodyshell sculptures Poma and Frilla (1972, extracted from book Heidi Bucher: Metamorphosis). B) Image generated by participant of the logbook in response to the daily prompt in A using a generative AI tool. “(...) it seemed to fit with the whole idea of caring for someone and the help you get is very limited from the state. So you are on your own. So it felt like you could easily represent that (...) with people wandering on a sort of desolated beach.”

Figure 7.

The vial of loss. For one advisor the physical materials sent in the mail enabled him to assemble a vial of matter that spoke profoundly to the things his wife had lost since she developed a rare form of dementia called Posterior Cortical Atrophy (PCA). They then took this vial to a favourite beach spot of theirs. Briefly, the vial contained salt—symbolises the salary my wife lost when she decided she could no longer work; cork—representing the loss of enjoying wine, as it doesn’t work well with the various medications; torn page—symbolises the loss of enjoying a good book or reading a menu. In the beginning the words on the page dissolve and rearrange themselves, the mind skips lines. One or two words will stand out on the page and the rest don’t register, making reading impossible; broken pencil—representing the loss of writing; rubber—symbolises the loss of driving as she gave up her license; onion skin—represents the inability to cook as the condition progressed the controls on the hob, oven and microwave became more difficult to use; key—symbolises the loss of freedom.

Figure 7.

The vial of loss. For one advisor the physical materials sent in the mail enabled him to assemble a vial of matter that spoke profoundly to the things his wife had lost since she developed a rare form of dementia called Posterior Cortical Atrophy (PCA). They then took this vial to a favourite beach spot of theirs. Briefly, the vial contained salt—symbolises the salary my wife lost when she decided she could no longer work; cork—representing the loss of enjoying wine, as it doesn’t work well with the various medications; torn page—symbolises the loss of enjoying a good book or reading a menu. In the beginning the words on the page dissolve and rearrange themselves, the mind skips lines. One or two words will stand out on the page and the rest don’t register, making reading impossible; broken pencil—representing the loss of writing; rubber—symbolises the loss of driving as she gave up her license; onion skin—represents the inability to cook as the condition progressed the controls on the hob, oven and microwave became more difficult to use; key—symbolises the loss of freedom.

Figure 8.

Light touch analysis was conducted on the text submitted in the logbook entries. The word cloud on the left displays the most frequently used words across all participants’ entries, providing a visual representation of prevalent themes and topics. The figure on the right illustrates the distribution of sentiment scores. In this analysis, a sentiment score of zero indicates a neutral tone, positive numbers correspond to positive emotions, and negative numbers are associated with typically negative emotions.

Figure 8.

Light touch analysis was conducted on the text submitted in the logbook entries. The word cloud on the left displays the most frequently used words across all participants’ entries, providing a visual representation of prevalent themes and topics. The figure on the right illustrates the distribution of sentiment scores. In this analysis, a sentiment score of zero indicates a neutral tone, positive numbers correspond to positive emotions, and negative numbers are associated with typically negative emotions.

Figure 9.

Examples of the prints we did together with the advisors at Ossa Pints.

Figure 9.

Examples of the prints we did together with the advisors at Ossa Pints.

Figure 10.

The Card deck.

Figure 10.

The Card deck.

Figure 11.

Examples of the car decks throws. We proposed different ways of playing with the decks, such as picking one card from each deck and reflecting, picking two cards from each deck to create a poem, song, dance, or noise, picking three cards from each deck to choose a beginning, middle, and end to tell a story, and picking four cards from each deck to arrange them in a shape. While at the same time, we also encourage to intuit one’s own unique rituals and ways to play the cards, which can be used alone or with others.

Figure 11.

Examples of the car decks throws. We proposed different ways of playing with the decks, such as picking one card from each deck and reflecting, picking two cards from each deck to create a poem, song, dance, or noise, picking three cards from each deck to choose a beginning, middle, and end to tell a story, and picking four cards from each deck to arrange them in a shape. While at the same time, we also encourage to intuit one’s own unique rituals and ways to play the cards, which can be used alone or with others.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).