Submitted:

04 September 2024

Posted:

04 September 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Materials

2.2.1. Demographics Information

2.2.2. Pet Bereavement Questionnaire (PBQ) – Chinese Version

2.2.3. Depression Subscale of Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale (DASS-21) - Chinese Version

2.2.4. Inventory of Complicated Grief (ICG) - Chinese Version

2.3. Translation and Adaptation Procedure

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Demographics

3.2. Validity

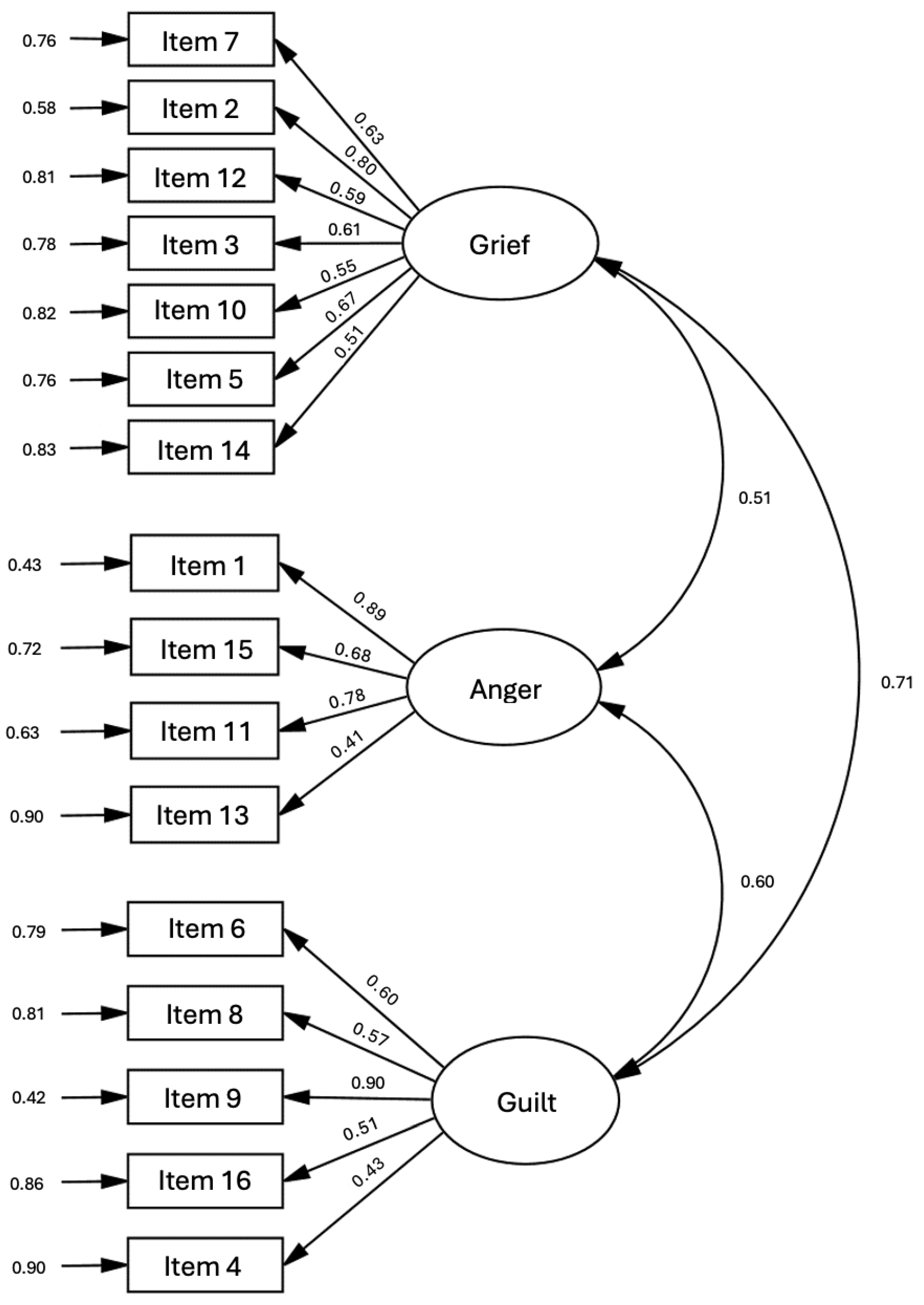

3.2.1. Construct Validity

3.2.2. Concurrent Validity

3.3. Reliability

3.3.1. Internal Consistency Reliability

3.3.2. Split Half Reliability

3.3. The Relationship between PBQ and Demographic Variables

4. Discussion

4.1. Interpretation of Results

4.2. Limitations

4.3. Implications

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- China Pet Market. China pet population and ownership 2022 update. 2022.

- Petfair. Southeast Asia pet market overview. 2024.

- Wu, P.-H. Number of pet dogs and cats increases. Taipei Times Jun 03, 2024 2024.

- Census and Statistics Department. Thematic Household Survey Report No,66. 2019, 63-80.

- Chu, A.; Fong, B.Y.F. Pet ownership and social wellness of elderly. In Ageing with dignity in Hong Kong and Asia: Holistic and humanistic care; Springer: 2022; pp. 289-304.

- Tan, J.S.Q.; Fung, W.; Tan, B.S.W.; Low, J.Y.; Syn, N.L.; Goh, Y.X.; Pang, J. Association between pet ownership and physical activity and mental health during the COVID-19 “circuit breaker” in Singapore. One Health 2021, 13, 100343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- RTHK. Hong Kong Connection Pet Companion 2023.

- Smith, N. Taiwan’s birth rate sinks to alarming low as pampered pets replace babies. The Telegraph 22 February 2022 2022.

- Chan, H.W.; Wong, D.F.K. Effects of Companion Dogs on Adult Attachment, Emotion Regulation, and Mental Wellbeing in Hong Kong. society & animals 2022, 30, 668–688. [Google Scholar]

- Wong, P.W.; Yu, R.W.; Ngai, J.T. Companion animal ownership and human well-being in a metropolis—the case of Hong Kong. International journal of environmental research and public health 2019, 16, 1729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, L.; Madresh, E.A. Romantic partners and four-legged friends: An extension of attachment theory to relationships with pets. Anthrozoös 2008, 21, 43–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Cepero, J.; Ferrer, M.; Mori, M.; Español, A. Companion animal bereavement: Psychometric properties of the Spanish version of the Pet Bereavement Questionnaire. Death Studies 2024, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerwolls, M.K.; Labott, S.M. Adjustment to the death of a companion animal. Anthrozoös 1994, 7, 172–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordan, A.; Vonk, J. No Loss of Support if Attached: Attachment Not Pet Type Predicts Grief, Loss Sharing, and Perceived Support. Anthrozoös 2024, 1-18.

- Habarth, J.; Bussolari, C.; Gomez, R.; Carmack, B.J.; Ronen, R.; Field, N.P.; Packman, W. Continuing bonds and psychosocial functioning in a recently bereaved pet loss sample. Anthrozoös 2017, 30, 651–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adrian, J.A.L.; Stitt, A. Pet loss, complicated grief, and post-traumatic stress disorder in Hawaii. Anthrozoös 2017, 30, 123–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.A. Does the DSM-5 grief disorder apply to owners of deceased pets? A psychometric study of impairment during pet loss. Psychiatry Research 2020, 285, 112800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Packman, W.; Carmack, B.J.; Katz, R.; Carlos, F.; Field, N.P.; Landers, C. Online survey as empathic bridging for the disenfranchised grief of pet loss. OMEGA-Journal of Death and Dying 2014, 69, 333–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, R.M.; Royal, K.D.; Gruen, M.E. A literature review: Pet bereavement and coping mechanisms. Journal of Applied Animal Welfare Science 2023, 26, 285–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, N.; Smith, K.V.; Stelzer, E.; Maercker, A.; Xi, J.; Killikelly, C. How the bereaved behave: a cross-cultural study of emotional display behaviours and rules. Cognition and Emotion 2023, 37, 1023–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, P.W.; Lau, K.C.; Liu, L.L.; Yuen, G.S.; Wing-Lok, P. Beyond recovery: Understanding the postbereavement growth from companion animal loss. OMEGA-Journal of Death and Dying 2017, 75, 103–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunt, M.; Padilla, Y. Development of the pet bereavement questionnaire. Anthrozoös 2006, 19, 308–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uccheddu, S.; De Cataldo, L.; Albertini, M.; Coren, S.; Da Graça Pereira, G.; Haverbeke, A.; Mills, D.S.; Pierantoni, L.; Riemer, S.; Ronconi, L. Pet humanisation and related grief: Development and validation of a structured questionnaire instrument to evaluate grief in people who have lost a companion dog. Animals 2019, 9, 933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yüksel, Ö.; Apak, B.; Demirci, Ö. Turkish version of the Pet Bereavement Questionnaire: Validity, reliability and psychometric properties. Death studies 2023, 47, 130–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, I.; Jólluskin, G.; Vilhena, E.; Byrne, A. Adaptation of the Pet Bereavement Questionnaire for European Portuguese Speakers. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2022, 20, 534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ADMCF. Hong Kong’s Invisible Pets. 2022.

- Lovibond, P.F.; Lovibond, S.H. The structure of negative emotional states: Comparison of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS) with the Beck Depression and Anxiety Inventories. Behaviour research and therapy 1995, 33, 335–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moussa, M.T.; Lovibond, P.F.; Laube, R. Psychometric properties of a Chinese version of the 21-item depression anxiety stress scales (DASS21). Sydney, NSW: Transcultural Mental Health Centre. Cumberland Hospital 2001.

- Prigerson, H.G.; Maciejewski, P.K.; Reynolds III, C.F.; Bierhals, A.J.; Newsom, J.T.; Fasiczka, A.; Frank, E.; Doman, J.; Miller, M. Inventory of Complicated Grief: a scale to measure maladaptive symptoms of loss. Psychiatry research 1995, 59, 65–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Prigerson, H.G. Assessment and associated features of prolonged grief disorder among Chinese bereaved individuals. Comprehensive Psychiatry 2016, 66, 9–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brislin, R.W. Back-translation for cross-cultural research. Journal of cross-cultural psychology 1970, 1, 185–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.; W.C., B.; B.J., B.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis., 7th ed.; Pearson: New York 2010.

- Byrne, B.M. Structural equation modeling with AMOS, EQS, and LISREL: Comparative approaches to testing for the factorial validity of a measuring instrument. International journal of testing 2001, 1, 55–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.; Black, W.; Babin, B.; Anderson, R.; Tatham, R. Multivariate Data Analysis 6th ed.; Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Prentice Hall: 2006.

- Wheaton, B.; Muthen, B.; Alwin, D.F.; Summers, G.F. Assessing reliability and stability in panel models. Sociological methodology 1977, 8, 84–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zasloff, R.L. Measuring attachment to companion animals: a dog is not a cat is not a bird. Applied Animal Behaviour Science 1996, 47, 43–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zilcha-Mano, S.; Mikulincer, M.; Shaver, P.R. An attachment perspective on human–pet relationships: Conceptualization and assessment of pet attachment orientations. Journal of Research in Personality 2011, 45, 345–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wrobel, T.A.; Dye, A.L. Grieving pet death: Normative, gender, and attachment issues. OMEGA-Journal of Death and Dying 2003, 47, 385–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubler-Ross, E.; Kessler, D. On grief and grieving: Finding the meaning of grief through the five stages of loss; Simon and Schuster: 2005.

- Shear, M.K.; Simon, N.; Wall, M.; Zisook, S.; Neimeyer, R.; Duan, N.; Reynolds, C.; Lebowitz, B.; Sung, S.; Ghesquiere, A. Complicated grief and related bereavement issues for DSM-5. Depression and anxiety 2011, 28, 103–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, S.M.Y.; Chan, I.S.F.; Ma, E.P.W.; Field, N.P. Continuing Bonds, Attachment Style, and Adjustment in the Conjugal Bereavement Among Hong Kong Chinese. Death Studies 2013, 37, 248–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H. Anger-expression avoidance in organizations in China: the role of social face. 2009.

- Erikson, E.H. Identity and the life cycle; WW Norton & company: 1994.

- Chen, Q.; Flaherty, J.H.; Guo, J.H.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, X.M.; Hu, X.Y. Attitudes of older Chinese patients toward death and dying. Journal of Palliative Medicine 2017, 20, 1389–1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, H.; Jin, Y.; Liu, R.; Zhang, Q.; Su, Z.; Ungvari, G.S.; Tang, Y.-L.; Ng, C.H.; Li, X.-H.; Xiang, Y.-T. Global prevalence of depression in older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis of epidemiological surveys. Asian journal of psychiatry 2023, 80, 103417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cowling, D.M.; Isenstein, S.G.; Schneider, M.S. When the bond breaks: Variables associated with grief following companion animal loss. Anthrozoös 2020, 33, 693–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koyasu, H.; Kikusui, T.; Takagi, S.; Nagasawa, M. The gaze communications between dogs/cats and humans: Recent research review and future directions. Frontiers in psychology 2020, 11, 613512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palagi, E.; Nicotra, V.; Cordoni, G. Rapid mimicry and emotional contagion in domestic dogs. Royal Society open science 2015, 2, 150505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brumett, A. When a pet goes missing: An exploratory study on ambiguous pet loss. Palo Alto University, 2023.

- Testoni, I.; De Cataldo, L.; Ronconi, L.; Colombo, E.S.; Stefanini, C.; Dal Zotto, B.; Zamperini, A. Pet grief: Tools to assess owners’ bereavement and veterinary communication skills. Animals 2019, 9, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cleary, M.; West, S.; Thapa, D.K.; Westman, M.; Vesk, K.; Kornhaber, R. Grieving the loss of a pet: A qualitative systematic review. Death studies 2022, 46, 2167–2178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnard-Nguyen, S.; Breit, M.; Anderson, K.A.; Nielsen, J. Pet loss and grief: Identifying at-risk pet owners during the euthanasia process. Anthrozoös 2016, 29, 421–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerrigan, L. Anticipating grief–the role of pre-euthanasia discussions. The Veterinary Nurse 2014, 5, 236–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matte, A.R.; Khosa, D.K.; Coe, J.B.; Meehan, M.; Niel, L. Exploring pet owners’ experiences and self-reported satisfaction and grief following companion animal euthanasia. Veterinary Record 2020, 187, e122–e122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Field, N.P.; Orsini, L.; Gavish, R.; Packman, W. Role of attachment in response to pet loss. Death studies 2009, 33, 334–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, C.L.J.; Chan, K.C. An Exploratory Study on the Grieving of the Bereaved Father in Hong Kong–from Grief Support Workers’ Perspective. In Proceedings of the RAIS Conference Proceedings 2022-2023; 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Li, T.; Wang, S.-W.; Zhou, J.-J.; Ren, Q.-Z.; Gao, Y.-L. Assessment and predictors of grief reactions among bereaved Chinese adults. Journal of palliative medicine 2018, 21, 1265–1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bussolari, C.J.; Habarth, J.; Katz, R.; Phillips, S.; Carmack, B.; Packman, W. The euthanasia decision-making process: A qualitative exploration of bereaved companion animal owners. Bereavement Care 2018, 37, 101–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Age | Total (n = 246) | % |

| 18-25 | 66 | 26.8 |

| 26-35 | 80 | 32.5 |

| 36-45 | 46 | 18.7 |

| 46-60 | 41 | 16.7 |

| 61 - 70 | 8 | 3.3 |

| 71 or above | 0 | 0 |

| Missing | 5 | 2 |

| Education Level | ||

| No Formal Education | 2 | 0.8 |

| Primary school or below | 2 | 0.8 |

| Junior secondary (Form 1 to Form 3) | 17 | 6.9 |

| Senior secondary (Form 4 to Form 7) / Hong Kong Diploma of Secondary Education | 36 | 14.6 |

| Non-degree courses (including Certificate / Diploma / Higher Diploma / Associate Degree / Yi Jin Diploma) | 28 | 11.4 |

| Bachelor's degree | 88 | 35.8 |

| Master's degree or above | 73 | 29.7 |

| Race | ||

| Chinese | 244 | 99.2 |

| Non-Chinese Asian | 2 | 0.8 |

| White | 0 | 0 |

| Black or African American | 0 | 0 |

| Other | 0 | 0 |

| Occupation | ||

| Student | 21 | 8.5 |

| Full-time | 170 | 69.1 |

| Part-time | 23 | 9.3 |

| Retired | 11 | 4.5 |

| Housewife | 11 | 4.5 |

| Unemployed / Job-seeking | 9 | 3.7 |

| Other | 1 | 00.4 |

| Marital Status | ||

| Single, without a partner | 58 | 23.6 |

| Single, with a partner | 61 | 24.8 |

| Cohabiting | 25 | 10.2 |

| Married | 92 | 37.4 |

| Divorced/Separated | 8 | 3.3 |

| Widowed | 2 | 0.8 |

| Personal monthly income | ||

| No income | 45 | 18.3 |

| Receiving Comprehensive Social Security Assistance (CSSA) | 2 | 0.8 |

| HKD $9,999 or below | 8 | 3.3 |

| HKD $10,000 to $19,999 | 40 | 16.3 |

| HKD $20,000 to $29,999 | 54 | 22.0 |

| HKD $30,000 to $39,999 | 32 | 13.0 |

| HKD $40,000 to $49,999 | 22 | 8.9 |

| HKD $50,000 to $59,999 | 14 | 5.7 |

| HKD $60,000 to $69,999 | 10 | 4.1 |

| HKD $70,000 to $79,999 | 3 | 1.2 |

| HKD $80,000 to $89,999 | 2 | 0.8 |

| HKD $100,000 or above | 1 | 0.4 |

| How many kids do you have? | ||

| 0 | 165 | 67.1 |

| 1 | 40 | 16.3 |

| 2 | 38 | 15.4 |

| 3 | 2 | 0.8 |

| 4 | 1 | 0.4 |

| 5 or above | 0 | 0 |

| Family members living with you (excluding yourself) | ||

| 0 | 26 | 10.6 |

| 1 | 74 | 30.1 |

| 2 | 65 | 26.4 |

| 3 | 50 | 20.3 |

| 4 | 21 | 8.5 |

| 5 or above | 10 | 4.1 |

| Do you currently have any pets? | ||

| Yes | 145 | 58.9 |

| No | 101 | 41.1 |

| How many pets have you ever had (including both current and past pets)? | ||

| 1 | 68 | 27.6 |

| 2 | 58 | 23.6 |

| 3 | 34 | 13.8 |

| 4 | 18 | 7.3 |

| 5 or above | 68 | 27.6 |

| How long has it been since your pet passed away? | ||

| 1–6 months | 40 | 16.3 |

| 7–12 months | 22 | 8.9 |

| 13–18 months | 32 | 13.0 |

| 19–24 months | 32 | 13.0 |

| Over 24 months | 115 | 46.7 |

| Missing values | 5 | 2.0 |

| Type of pet lost | ||

| Cat | 75 | 30.5 |

| Dog | 110 | 44.7 |

| Hamster | 18 | 7.3 |

| Rabbit | 12 | 4.9 |

| Bird | 8 | 3.3 |

| Lizard | 4 | 1.6 |

| Other (e.g., Turtle, snail, snake, fish, Guinea Pig, frog, Totoro) | 14 | 5.7 |

| Missing | 5 | 2.0 |

| Cause of pet's death | ||

| Medical negligence or complications after treatment | 28 | 11.4 |

| Health issues related to old age | 163 | 66.3 |

| Poisoning/attack | 10 | 4.1 |

| Accident | 13 | 5.3 |

| Unknown | 24 | 9.8 |

| Missing values | 8 | 3.3 |

| Have you ever euthanized your pet? | ||

| Yes | 95 | 38.6 |

| No | 143 | 58.1 |

| Missing | 8 | 3.3 |

| Item | Factors Communities | |||

| Grief | Anger | Guilt | ||

| 7 | I miss my pet enormously. 我非常想念我的寵物。 |

0.81 | ||

| 2 | I am very upset about my pet’s death. 我對寵物的離世感到非常痛心。 |

0.79 | ||

| 12 | I am very sad about the death of my pet. 我對寵物的離世感到非常悲傷。 |

0.75 | ||

| 3 | My life feels empty without my pet. 失去寵物後,我感到生活變得空虛。 |

0.70 | ||

| 10 | I cry when I think about my pet. 當我想起我的寵物時,我會哭泣。 |

0.61 | ||

| 5 | I feel lonely without my pet. 失去寵物後,我感到非常孤獨。 |

0.60 | ||

| 14 | Memories of my pet’s last moments haunt me. 我對憶起寵物臨終前的最後片段感到非常煎熬。 |

0.54 | ||

| 1 | I feel angry at the veterinarian for not being able to save my pet. 我對獸醫無法救活我的寵物而感到憤怒。 |

0.84 | ||

| 15 | I’ll never get over the loss of my pet. 我永遠無法走出失去寵物的陰影。 |

0.70 | ||

| 11 | I am angry at other people for contributing to the death of my pet. 我對其他人有份造成我寵物的死亡而感到憤怒。 |

0.63 | ||

| 13 | I am angry at my friends/family for not being more helpful. 我對我的朋友/家人沒有提供更多的幫助而感到憤怒。 |

0.56 | ||

| 6 | I should have known that something bad could have happened to my pet. 我本應可以察覺我的寵物可能會發生不好的事情。 |

0.73 | ||

| 8 | I feel very guilty for not taking care better care of my pet. 我對於未能給予我的寵物更好的照顧而感到非常內疚。 |

0.68 | ||

| 9 | I feel bad that I didn’t do more to save my pet. 我對於我沒有做更多的事情來拯救我的寵物而感到遺憾。 |

0.63 | ||

| 16 | I wish I had shown my pet more love. 我希望我能對我的寵物表現出更多的愛。 |

0.60 | ||

| 4 | I have had nightmares about my pet’s death. 我曾經做過關於我寵物離世的噩夢。 |

0.43 | ||

| Cumulative Explained Variance Ratio | 23% | 46% | 63% | |

| χ²/df | CFI | NFI | GFI | RMSEA | AIC | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | 3.93 | 0.86 | 0.82 | 0.81 | 0.09 | 389.09 |

| Model 2 | 2.26 | 0.94 | 0.90 | 0.92 | 0.05 | 298.50 |

| Measures | Total PBQ | Grief | Guilt | Anger |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ICG | 0.78** | 0.70** | 0.62** | 0.73** |

| DASS Depression | 0.71** | 0.62** | 0.59** | 0.68** |

| Total PBQ | - | 0.92** | 0.88** | 0.81** |

| Grief | 0.92** | - | 0.71** | 0.62** |

| Guilt | 0.88** | 0.71** | - | 0.61** |

| Anger | 0.81* | 0.62** | 0.61** | - |

| Items | Item-total Correlation | Cronbach's alpha value when the item is deleted | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | I feel angry at the veterinarian for not being able to save my pet. 我對獸醫無法救活我的寵物而感到憤怒。 |

0.53 | 0.92 |

| 2 | I am very upset about my pet’s death. 我對寵物的離世感到非常痛心。 |

0.52 | 0.92 |

| 3 | My life feels empty without my pet. 失去寵物後,我感到生活變得空虛。 |

0.69 | 0.92 |

| 4 | I have had nightmares about my pet’s death. 我曾經做過關於我寵物離世的噩夢。 |

0.46 | 0.92 |

| 5 | I feel lonely without my pet. 失去寵物後,我感到非常孤獨。 |

0.75 | 0.91 |

| 6 | I should have known that something bad could have happened to my pet. 我本應可以察覺我的寵物可能會發生不好的事情。 |

0.48 | 0.92 |

| 7 | I miss my pet enormously. 我非常想念我的寵物。 |

0.57 | 0.92 |

| 8 | I feel very guilty for not taking care better care of my pet. 我對於未能給予我的寵物更好的照顧而感到非常內疚。 |

0.71 | 0.91 |

| 9 | I feel bad that I didn’t do more to save my pet. 我對於我沒有做更多的事情來拯救我的寵物而感到遺憾。 |

0.73 | 0.91 |

| 10 | I cry when I think about my pet. 當我想起我的寵物時,我會哭泣。 |

0.70 | 0.91 |

| 11 | I am angry at other people for contributing to the death of my pet. 我對其他人有份造成我寵物的死亡而感到憤怒。 |

0.53 | 0.92 |

| 12 | I am very sad about the death of my pet. 我對寵物的離世感到非常悲傷。 |

0.70 | 0.91 |

| 13 | I am angry at my friends/family for not being more helpful. 我對我的朋友/家人沒有提供更多的幫助而感到憤怒。 |

0.48 | 0.92 |

| 14 | Memories of my pet’s last moments haunt me. 我對憶起寵物臨終前的最後片段感到非常煎熬。 |

0.74 | 0.91 |

| 15 | I’ll never get over the loss of my pet. 我永遠無法走出失去寵物的陰影。 |

0.74 | 0.91 |

| 16 | I wish I had shown my pet more love. 我希望我能對我的寵物表現出更多的愛。 |

0.56 | 0.92 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).