Submitted:

04 September 2024

Posted:

06 September 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

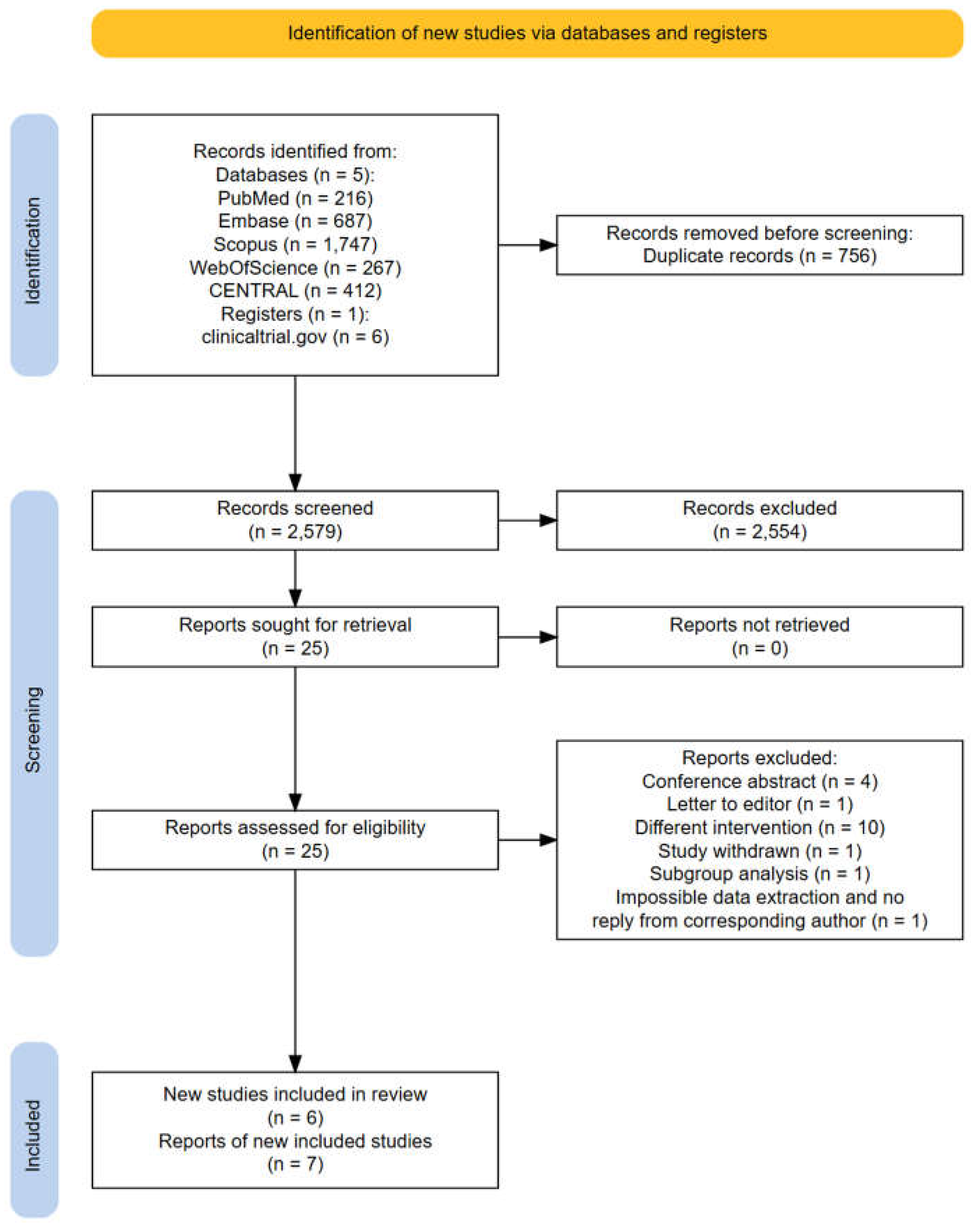

2.1. Search Strategy and Selection Criteria

2.2. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of the Studies Included in this Meta-Analysis

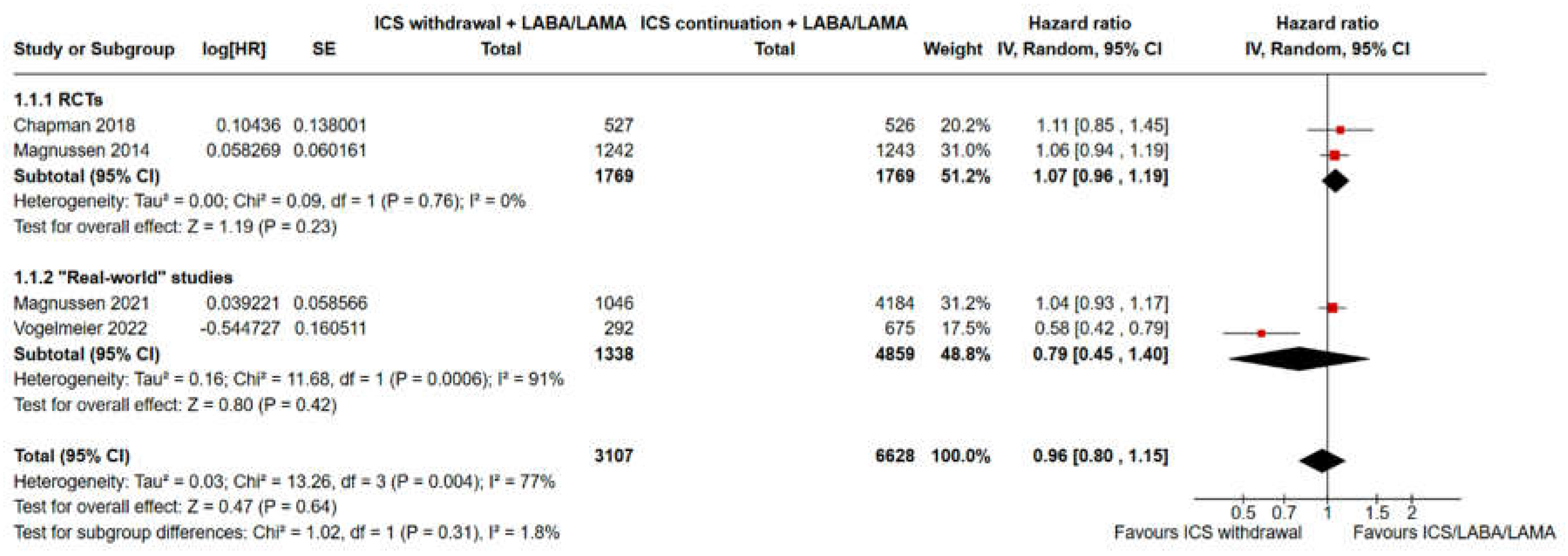

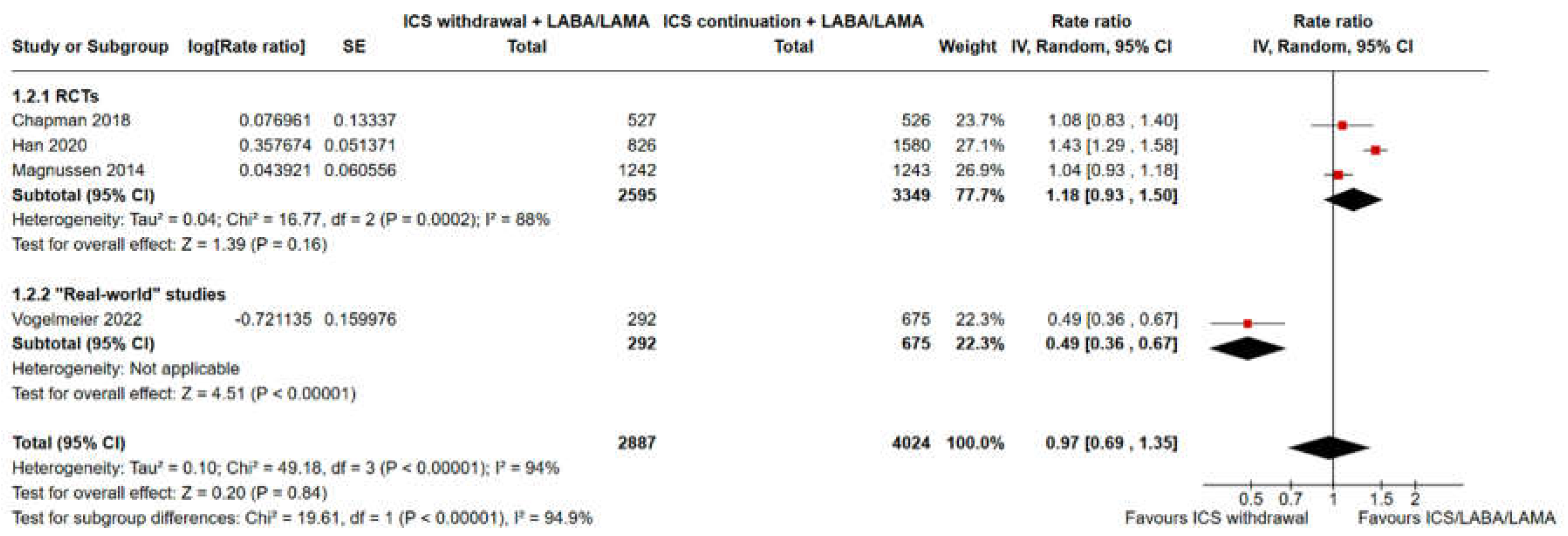

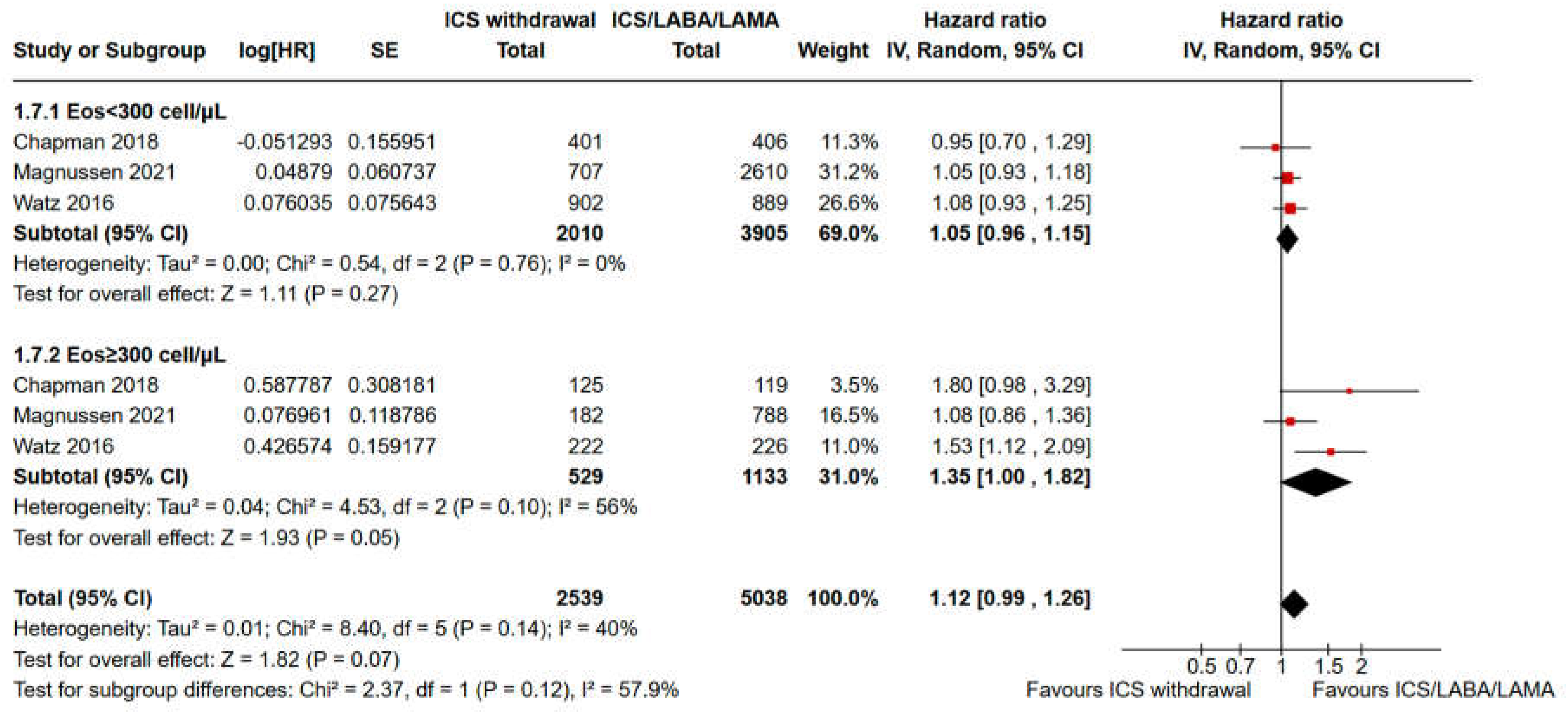

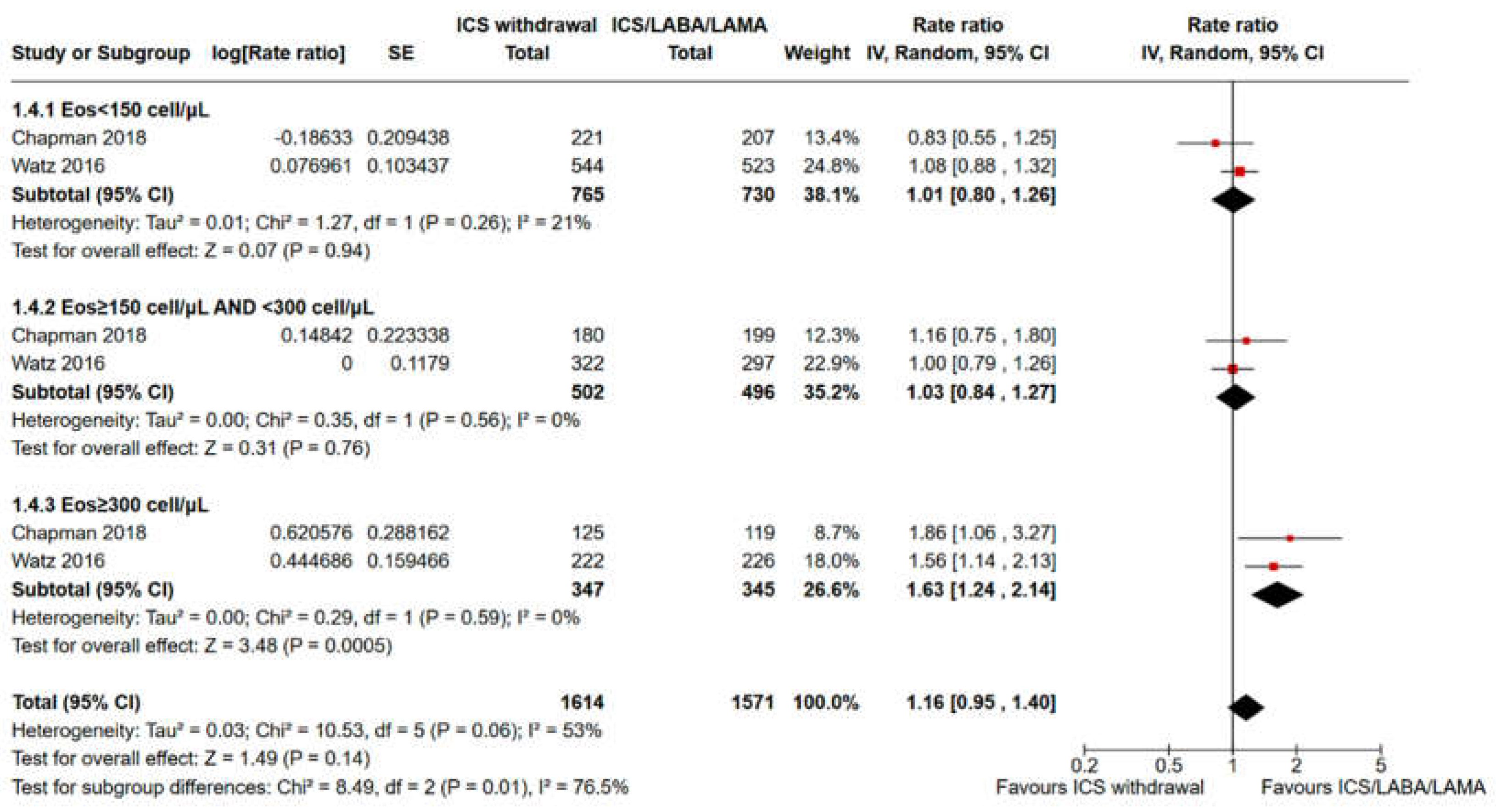

3.2. Pooled Analysis of Time to the First Moderate or Severe Exacerbation and Event Rate for ICS Withdrawal Compared with Continuation of Triple Therapy

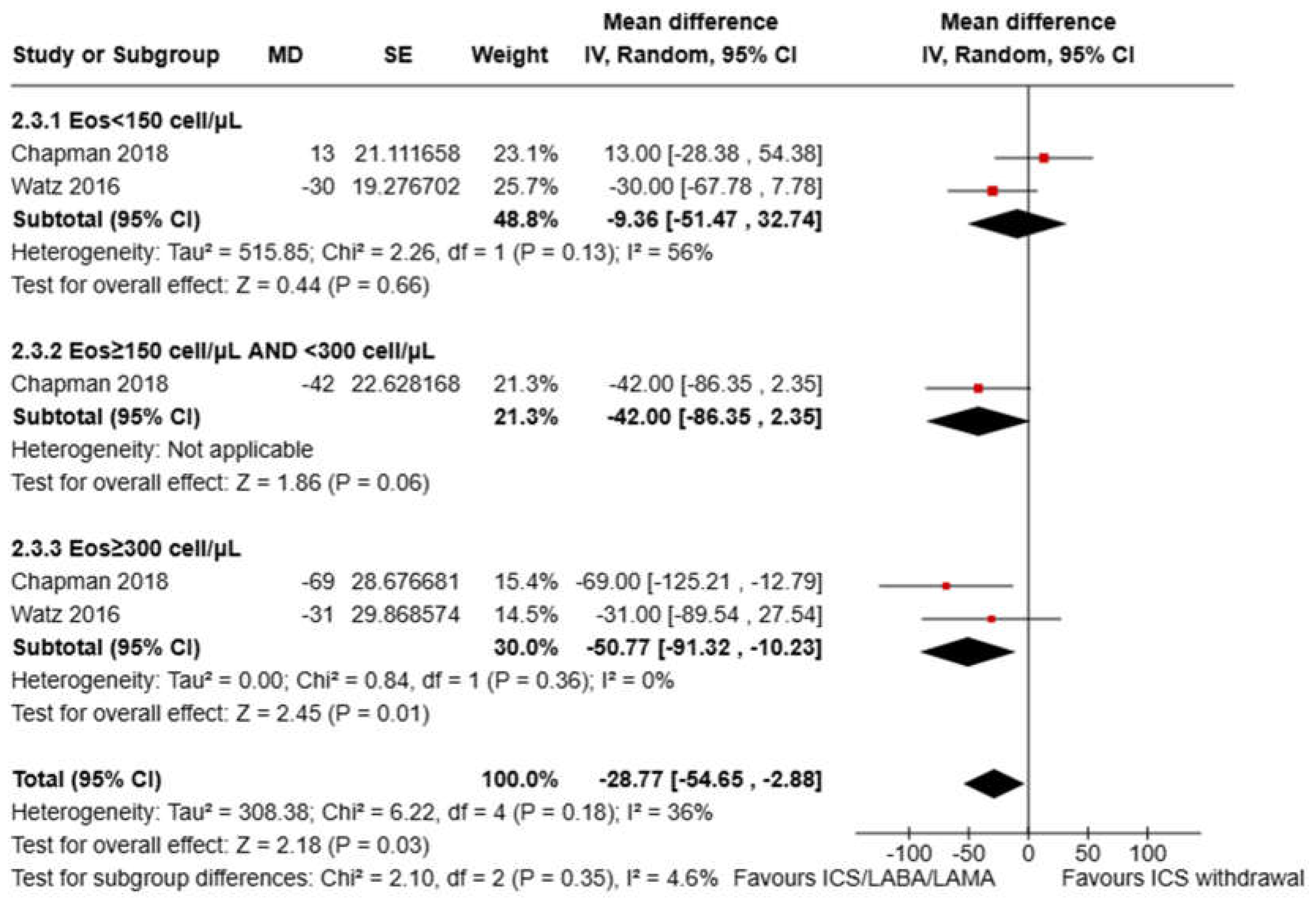

3.3. Pooled Analysis of FEV1 Variation

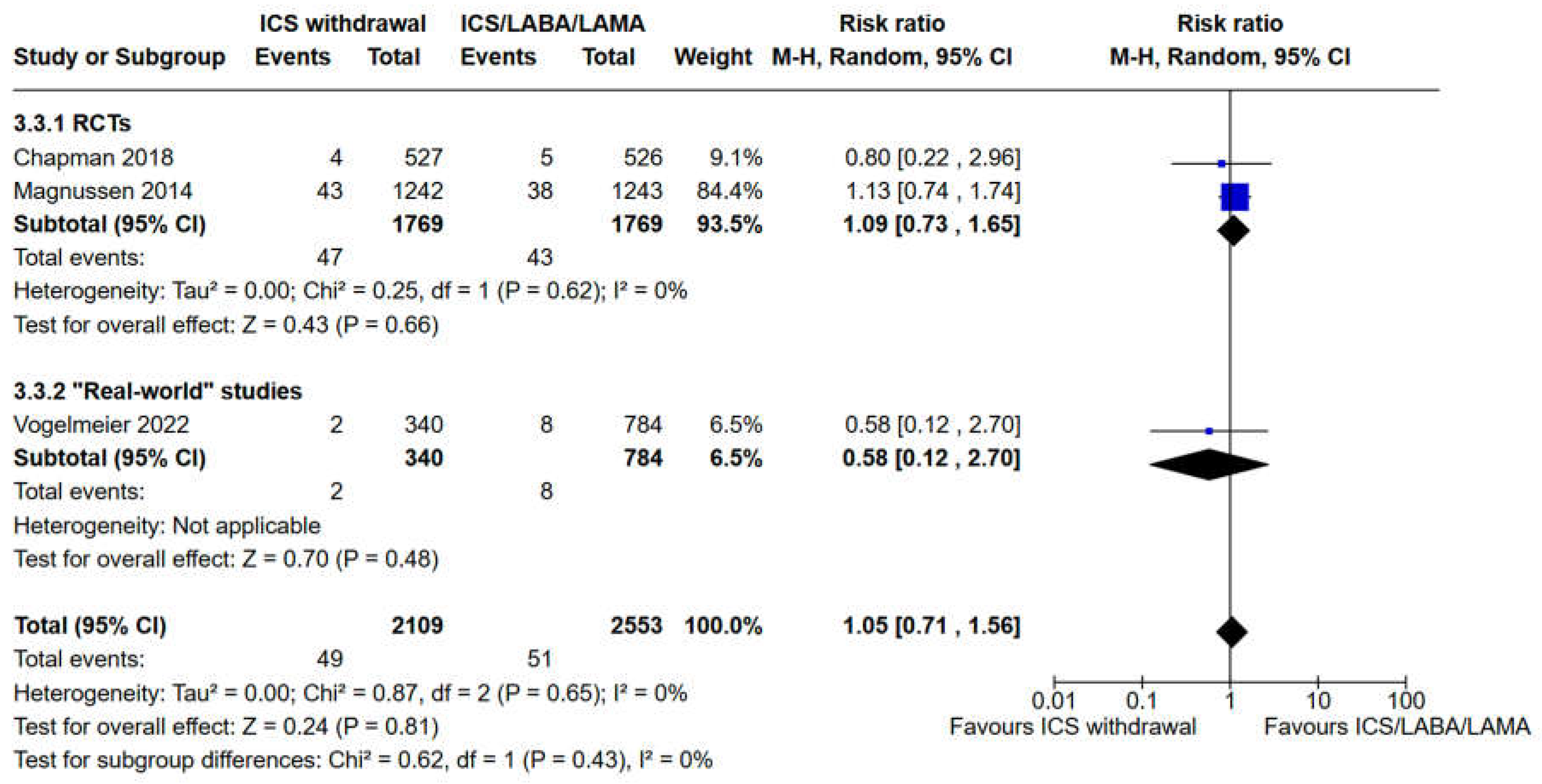

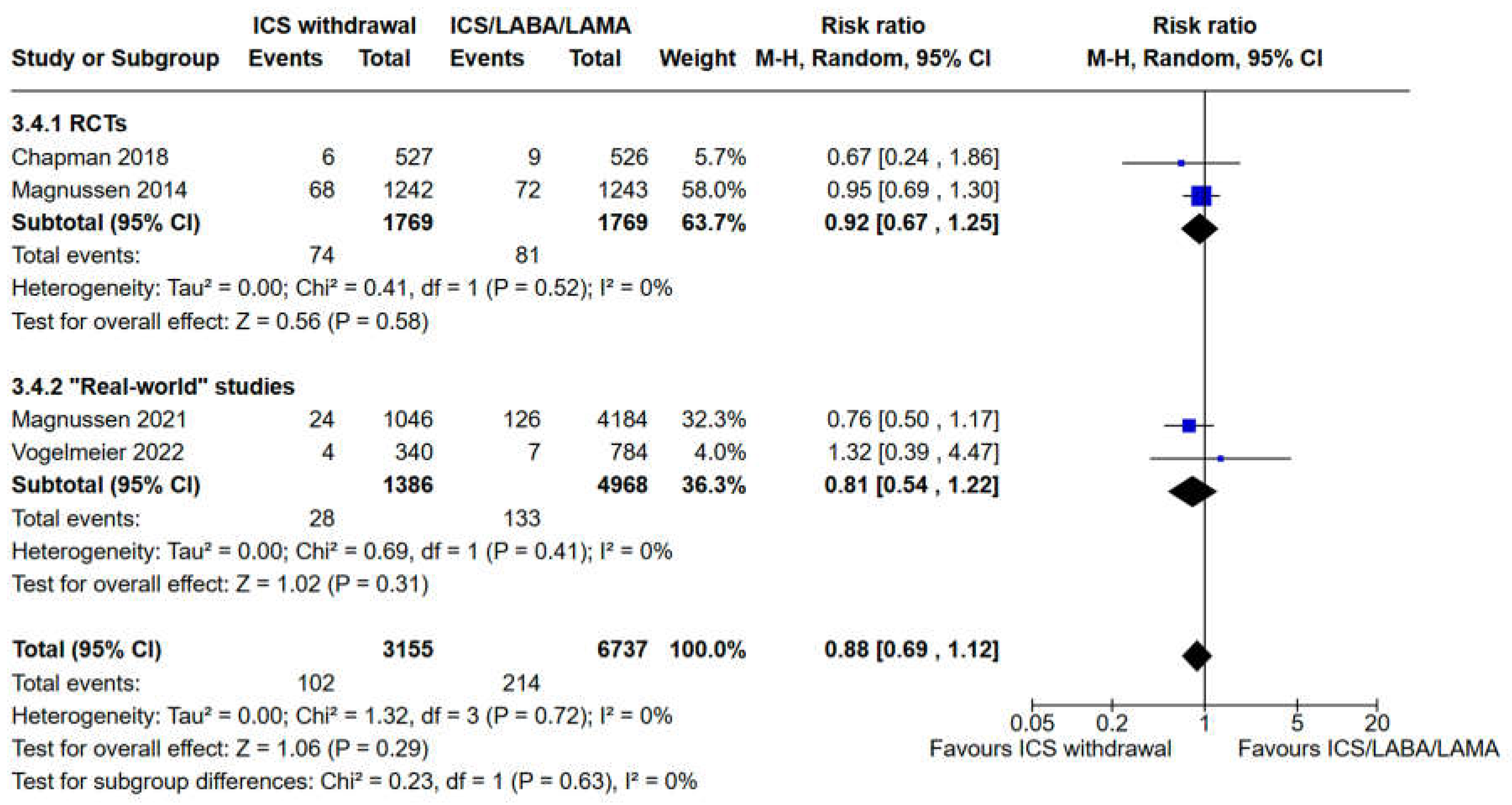

3.3. Evaluation of Safety Outcomes: Risk of Pneumonia and All Cause Mortality

3.4. Sensitivity Analyses and Risk of Bias Assessment

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- 2024 GOLD Report Available online: https://goldcopd.org/2024-gold-report/ (accessed on 17 April 2024).

- Nici, L.; Mammen, M.J.; Charbek, E.; Alexander, P.E.; Au, D.H.; Boyd, C.M.; Criner, G.J.; Donaldson, G.C.; Dreher, M.; Fan, V.S.; et al. Pharmacologic Management of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. An Official American Thoracic Society Clinical Practice Guideline. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care. Med. 2020, 201, e56–e69, doi:10.1164/rccm.202003-0625ST. [CrossRef]

- Rabe, K.F.; Martinez, F.J.; Ferguson, G.T.; Wang, C.; Singh, D.; Wedzicha, J.A.; Trivedi, R.; St Rose, E.; Ballal, S.; McLaren, J.; et al. Triple Inhaled Therapy at Two Glucocorticoid Doses in Moderate-to-Very-Severe COPD. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 383, 35–48, doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1916046. [CrossRef]

- Lipson, D.A.; Barnhart, F.; Brealey, N.; Brooks, J.; Criner, G.J.; Day, N.C.; Dransfield, M.T.; Halpin, D.M.G.; Han, M.K.; Jones, C.E.; et al. Once-Daily Single-Inhaler Triple versus Dual Therapy in Patients with COPD. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 378, 1671–1680, doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1713901. [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, G.T.; Rabe, K.F.; Martinez, F.J.; Fabbri, L.M.; Wang, C.; Ichinose, M.; Bourne, E.; Ballal, S.; Darken, P.; DeAngelis, K.; et al. Triple Therapy with Budesonide/Glycopyrrolate/Formoterol Fumarate with Co-Suspension Delivery Technology versus Dual Therapies in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (KRONOS): A Double-Blind, Parallel-Group, Multicentre, Phase 3 Randomised Controlled Trial. Lancet Respir. Med. 2018, 6, 747–758, doi:10.1016/S2213-2600(18)30327-8. [CrossRef]

- Papi, A.; Vestbo, J.; Fabbri, L.; Corradi, M.; Prunier, H.; Cohuet, G.; Guasconi, A.; Montagna, I.; Vezzoli, S.; Petruzzelli, S.; et al. Extrafine Inhaled Triple Therapy versus Dual Bronchodilator Therapy in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (TRIBUTE): A Double-Blind, Parallel Group, Randomised Controlled Trial. Lancet. 2018, 391, 1076–1084, doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30206-X. [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Zhu, J.; Liu, Y.; Lai, W.; Lin, C.; Qiu, K.; Wu, J.; Yao, W. Triple Therapy in the Management of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. BMJ. 2018, 363, k4388, doi:10.1136/bmj.k4388. [CrossRef]

- Calzetta, L.; Matera, M.G.; Braido, F.; Contoli, M.; Corsico, A.; Di Marco, F.; Santus, P.; Scichilone, N.; Cazzola, M.; Rogliani, P. Withdrawal of Inhaled Corticosteroids in COPD: A Meta-Analysis. Pulm. Pharmacol. Ther. 2017, 45, 148–158, doi:10.1016/j.pupt.2017.06.002. [CrossRef]

- Suissa, S.; Dell’Aniello, S.; Ernst, P. Single-Inhaler Triple versus Dual Bronchodilator Therapy in COPD: Real-World Comparative Effectiveness and Safety. Int. J. Chron. Obstruct. Pulmon. Dis. 2022, 17, 1975–1986, doi:10.2147/COPD.S378486. [CrossRef]

- Suissa, S.; Dell’Aniello, S.; Ernst, P. Triple Inhaler versus Dual Bronchodilator Therapy in COPD: Real-World Effectiveness on Mortality. COPD 2022, 19, 1–9, doi:10.1080/15412555.2021.1977789. [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G.; PRISMA Group Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. BMJ 2009, 339, b2535, doi:10.1136/bmj.b2535. [CrossRef]

- Sterne, J.A.C.; Savović, J.; Page, M.J.; Elbers, R.G.; Blencowe, N.S.; Boutron, I.; Cates, C.J.; Cheng, H.-Y.; Corbett, M.S.; Eldridge, S.M.; et al. RoB 2: A Revised Tool for Assessing Risk of Bias in Randomised Trials. BMJ 2019, 366, l4898, doi:10.1136/bmj.l4898. [CrossRef]

- Sterne, J.A.; Hernán, M.A.; Reeves, B.C.; Savović, J.; Berkman, N.D.; Viswanathan, M.; Henry, D.; Altman, D.G.; Ansari, M.T.; Boutron, I.; et al. ROBINS-I: A Tool for Assessing Risk of Bias in Non-Randomised Studies of Interventions. BMJ 2016, 355, i4919, doi:10.1136/bmj.i4919. [CrossRef]

- Miller, R.G. The Jackknife--A Review. Biometrika 1974, 61, 1–15, doi:10.2307/2334280. [CrossRef]

- Magnussen, H.; Disse, B.; Rodriguez-Roisin, R.; Kirsten, A.; Watz, H.; Tetzlaff, K.; Towse, L.; Finnigan, H.; Dahl, R.; Decramer, M.; et al. Withdrawal of Inhaled Glucocorticoids and Exacerbations of COPD. New. Engl. J. Med. 2014, 371, 1285–1294, doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1407154. [CrossRef]

- Watz, H.; Tetzlaff, K.; Wouters, E.F.M.; Kirsten, A.; Magnussen, H.; Rodriguez-Roisin, R.; Vogelmeier, C.; Fabbri, L.M.; Chanez, P.; Dahl, R.; et al. Blood Eosinophil Count and Exacerbations in Severe Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease after Withdrawal of Inhaled Corticosteroids: A Post-Hoc Analysis of the WISDOM Trial. Lancet Respir. Med. 2016, 4, 390–398, doi:10.1016/S2213-2600(16)00100-4. [CrossRef]

- Han, M.; Criner, G.; Dransfield, M.; Halpin, D.; Jones, C.; Kilbride, S.; Lange, P.; Lettis, S.; Lipson, D.; Lomas, D.; et al. The Effect of Inhaled Corticosteroid Withdrawal and Baseline Inhaled Treatment on Exacerbations in the IMPACT Study A Randomized, Double-Blind, Multicenter Clinical Trial. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care. Med. 2020, 202, 1237–1243, doi:10.1164/rccm.201912-2478OC. [CrossRef]

- Chapman, K.R.; Hurst, J.R.; Frent, S.-M.; Larbig, M.; Fogel, R.; Guerin, T.; Banerji, D.; Patalano, F.; Goyal, P.; Pfister, P.; et al. Long-Term Triple Therapy De-Escalation to Indacaterol/Glycopyrronium in Patients with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (SUNSET): A Randomized, Double-Blind, Triple-Dummy Clinical Trial. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care. Med. 2018, 198, 329–339, doi:10.1164/rccm.201803-0405OC. [CrossRef]

- Whittaker, H.; Wing, K.; Douglas, I.; Kiddle, S.; Quint, J. Inhaled Corticosteroid Withdrawal and Change in Lung Function in Primary Care Patients with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease in England. Ann. Am. Thorac. Soc. 2022, 19, 1834–1841, doi:10.1513/AnnalsATS.202111-1238OC. [CrossRef]

- Vogelmeier, C.; Worth, H.; Buhl, R.; Criée, C.; Gückel, E.; Kardos, P. Impact of Switching from Triple Therapy to Dual Bronchodilation in COPD: The DACCORD “real World” Study. Respir. Res. 2022, 23, doi:10.1186/s12931-022-02037-2. [CrossRef]

- Magnussen, H.; Lucas, S.; Lapperre, T.; Quint, J.; Dandurand, R.; Roche, N.; Papi, A.; Price, D.; Miravitlles, M.; REG Withdrawal of Inhaled Corticosteroids versus Continuation of Triple Therapy in Patients with COPD in Real Life: Observational Comparative Effectiveness Study. Respir. Res. 2021, 22, doi:10.1186/s12931-021-01615-0. [CrossRef]

- Koarai, A.; Yamada, M.; Ichikawa, T.; Fujino, N.; Kawayama, T.; Sugiura, H. Triple versus LAMA/LABA Combination Therapy for Patients with COPD: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Respir. Res. 2021, 22, doi:10.1186/s12931-021-01777-x. [CrossRef]

- Bjermer, L.H.; Boucot, I.H.; Vogelmeier, C.F.; Maltais, F.; Jones, P.W.; Tombs, L.; Compton, C.; Lipson, D.A.; Kerwin, E.M. Efficacy and Safety of Umeclidinium/Vilanterol in Current and Former Smokers with COPD: A Prespecified Analysis of The EMAX Trial. Adv. Ther. 2021, 38, 4815–4835, doi:10.1007/s12325-021-01855-y. [CrossRef]

- Cho, E.E.; Gershon, A.S. Single vs Multiple Inhaler Triple Therapy in the COPD Population. CHEST 2022, 162, 947–948, doi:10.1016/j.chest.2022.09.004. [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, G.T.; Brown, N.; Compton, C.; Corbridge, T.C.; Dorais, K.; Fogarty, C.; Harvey, C.; Kaisermann, M.C.; Lipson, D.A.; Martin, N.; et al. Once-Daily Single-Inhaler versus Twice-Daily Multiple-Inhaler Triple Therapy in Patients with COPD: Lung Function and Health Status Results from Two Replicate Randomized Controlled Trials. Respir. Res. 2020, 21, doi:10.1186/s12931-020-01360-w. [CrossRef]

- Buhl, R.; Criée, C.-P.; Kardos, P.; Vogelmeier, C.; Lossi, N.; Mailänder, C.; Worth, H. A Year in the Life of German Patients with COPD: The DACCORD Observational Study. Int. J. Chron. Obstruct. Pulmon. Dis.2016, 11, 1639–1646, doi:10.2147/COPD.S112110. [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Hong, Y.; Rhee, C.; Choi, H.; Kim, K.; Ha Yoo, K.; Jung, K.; Park, J. The Impact of Inhaled Corticosteroids on the Prognosis of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Int. J. Chron. Obstruct. Pulmon. Dis. 2023, 18, 733–743, doi:10.2147/COPD.S388367. [CrossRef]

- Agusti, A.; Fabbri, L.M.; Singh, D.; Vestbo, J.; Celli, B.; Franssen, F.M.E.; Rabe, K.F.; Papi, A. Inhaled Corticosteroids in COPD: Friend or Foe? Eur. Respir. J. 2018, 52, doi:10.1183/13993003.01219-2018. [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Restrepo, M.I.; Fine, M.J.; V. Pugh, M.J.; Anzueto, A.; Metersky, M.L.; Nakashima, B.; Good, C.; Mortensen, E.M. Observational Study of Inhaled Corticosteroids on Outcomes for COPD Patients with Pneumonia. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2011, 184, 312–316, doi:10.1164/rccm.201012-2070OC. [CrossRef]

- Singanayagam, A.; Chalmers, J.D.; Akram, A.R.; Hill, A.T. Impact of Inhaled Corticosteroid Use on Outcome in COPD Patients Admitted with Pneumonia. Eur. Respir. J. 2011, 38, 36–41, doi:10.1183/09031936.00077010. [CrossRef]

- Harries, T.H.; Gilworth, G.; Corrigan, C.J.; Murphy, P.B.; Hart, N.; Thomas, M.; White, P.T. Inhaled Corticosteroids Prescribed for Copd Patients with Mild or Moderate Airflow Limitation: Who Warrants a Trial of Withdrawal? Int. J. COPD 2019, 14, 3063–3066, doi:10.2147/COPD.S238239. [CrossRef]

- Calverley, P.M.A. Minimal Clinically Important Difference - Exacerbations of COPD. COPD. 2005, 2, 143–148. doi: 10.1081/copd-200050647. [CrossRef]

- Jones, P.W.; Beeh, K.M.; Chapman, K.R.; Decramer, M.; Mahler, D.A.; Wedzicha, J.A. Minimal Clinically Important Differences in Pharmacological Trials. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2014, 189, 250–255, doi:10.1164/rccm.201310-1863PP. [CrossRef]

- Maselli, D.J.; Hanania, N.A. Management of Asthma COPD Overlap. Ann. Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2019, 123, 335–344, doi:10.1016/j.anai.2019.07.021. [CrossRef]

- Demarche, S.F.; Schleich, F.N.; Henket, M.A.; Paulus, V.A.; Van Hees, T.J.; Louis, R.E. Effectiveness of Inhaled Corticosteroids in Real Life on Clinical Outcomes, Sputum Cells and Systemic Inflammation in Asthmatics: A Retrospective Cohort Study in a Secondary Care Centre. BMJ Open. 2017, 7, doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2017-018186. [CrossRef]

- Miravitlles, M.; Auladell-Rispau, A.; Monteagudo, M.; Vázquez-Niebla, J.C.; Mohammed, J.; Nuñez, A.; Urrútia, G. Systematic Review on Long-Term Adverse Effects of Inhaled Corticosteroids in the Treatment of COPD. Eur. Respir. Rev. 2021, 30, doi:10.1183/16000617.0075-2021. [CrossRef]

- GOLD-2019-v1.7-FINAL-14Nov2018-WMS.Pdf.

- Pascoe, S.; Locantore, N.; Dransfield, M.T.; Barnes, N.C.; Pavord, I.D. Blood Eosinophil Counts, Exacerbations, and Response to the Addition of Inhaled Fluticasone Furoate to Vilanterol in Patients with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease: A Secondary Analysis of Data from Two Parallel Randomised Controlled Trials. Lancet Respir. Med. 2015, 3, 435–442, doi:10.1016/S2213-2600(15)00106-X. [CrossRef]

- Bafadhel, M.; Peterson, S.; De Blas, M.A.; Calverley, P.M.; Rennard, S.I.; Richter, K.; Fagerås, M. Predictors of Exacerbation Risk and Response to Budesonide in Patients with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease: A Post-Hoc Analysis of Three Randomised Trials. Lancet Respir. Med. 2018, 6, 117–126, doi:10.1016/S2213-2600(18)30006-7. [CrossRef]

- Roche, N.; Chapman, K.R.; Vogelmeier, C.F.; Herth, F.J.F.; Thach, C.; Fogel, R.; Olsson, P.; Patalano, F.; Banerji, D.; Wedzicha, J.A. Blood Eosinophils and Response to Maintenance Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Treatment. Data from the FLAME Trial. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2017, 195, 1189–1197, doi:10.1164/rccm.201701-0193OC. [CrossRef]

- Wedzicha, J.A.; Banerji, D.; Chapman, K.R.; Vestbo, J.; Roche, N.; Ayers, R.T.; Thach, C.; Fogel, R.; Patalano, F.; Vogelmeier, C.F. Indacaterol-Glycopyrronium versus Salmeterol-Fluticasone for COPD. New Engl. J. Med. 2016, 374, 2222–2234, doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1516385. [CrossRef]

- Chalmers, J.D.; Laska, I.F.; Franssen, F.M.E.; Janssens, W.; Pavord, I.; Rigau, D.; McDonnell, M.J.; Roche, N.; Sin, D.D.; Stolz, D.; et al. Withdrawal of Inhaled Corticosteroids in COPD: A European Respiratory Society Guideline. Eur. Respir. J. 2020, 55, doi:10.1183/13993003.00351-2020. [CrossRef]

|

Study Duration (weeks) |

52 weeks | 52 weeks | 24 weeks | 52 weeks | 52 weeks | At least six months |

| Postbronchodilator FEV1 (% predicted) | 34,2±11,0 | N/A | 56,6±9,97 | 54,8±22,2 | 60,5±23,7 | N/A |

| Current Smoker (%) | 66,6 | N/A | N/A | 34,7 | 31,13 | 50,5 |

|

Male (%) |

82,5 | N/A | 70,6 | 55,4 | 57,7 | 61,2 |

|

Age (mean±SD) |

63,8±8,5 | N/A | 65,3±7,80 | 70,8±9,9 | 69,13±9,42 | 67,9±9,1 |

| Asthma | History: not reported; Current: Excluded; |

History: Included; Current: Excluded; |

History: Excluded; Current: Excluded; |

History: Included; Current: Included; |

History: Excluded; Current: Excluded; |

History: not reported; Current: Excluded; |

|

History of Exacerba-tion |

≥1 AE in the 12 months before screening |

≥1 AE in the 12 months before screening | ≤1 moderate or severe AE in the previous year |

N/A | N/A | Same as WISDOM; |

|

Patients Characteri- stics |

40 years old with FEV1<50% and FVC<70% | 40 years old with FEV1<50% and ≥1 moderate or severe AE or 50%≤FEV1<80% and ≥ 2 moderate or ≥ 1 severe AE | 40 years old with moderate to severe COPD | 40 years old with COPD | 40 years old with COPD | Same as WISDOM; |

| Control Group | Tiotropium 18µg OD Salmeterol 50µg BID (Separate inhalers) |

Umeclidinium 62,5µg Vilanterol 25µg OD (Fixed inhaler) |

Glycopyrronium 50µg OD Indacaterol 110µg BID (Separate inhalers) |

LABA/LAMA | LABA/LAMA | LABA/LAMA |

| Intervention | Tiotropium 18µg OD Salmeterol 50µg BID Formoterol 500µg BID (Separate inhalers) |

Fluticasone furoate 100µg Umeclidinium 62,5µg Vilanterol 25µg OD (Fixed inhaler) |

Fluticasone furoate 500µg BID Tiotropium 18µg OD Salmeterol 50µg BID (Separate inhalers) |

ICS/LABA/LAMA | ICS/LABA/LAMA | ICS/LABA/LAMA |

|

Total population (n) |

2485 | 2406 | 1053 | 5230 | 1124 | 6008 |

| Design | RCT | RCT | RCT | Non-RCT | Non-RCT | Non-RCT |

| Identifier | WISDOM, NCT00975195 | IMPACT, NCT02164513 | SUNSET, NCT02603393 | EUPAS30851 | DACCORD EUPAS4207 | N/A |

| 1st Author, year, Ref | Magnussen, 2014 Watz, 2016 [15,16] |

Han, 2020 [17] | Chapman, 2018 [18] | Magnussen, 2021 [21] | Vogelmaier, 2022 [20] | Whittaker, 2022 [19] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).