Submitted:

04 September 2024

Posted:

05 September 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. High-Throughput Screening of the Maybridge HitFinderTM Chemical Library Identified Novel HsrA Ligands

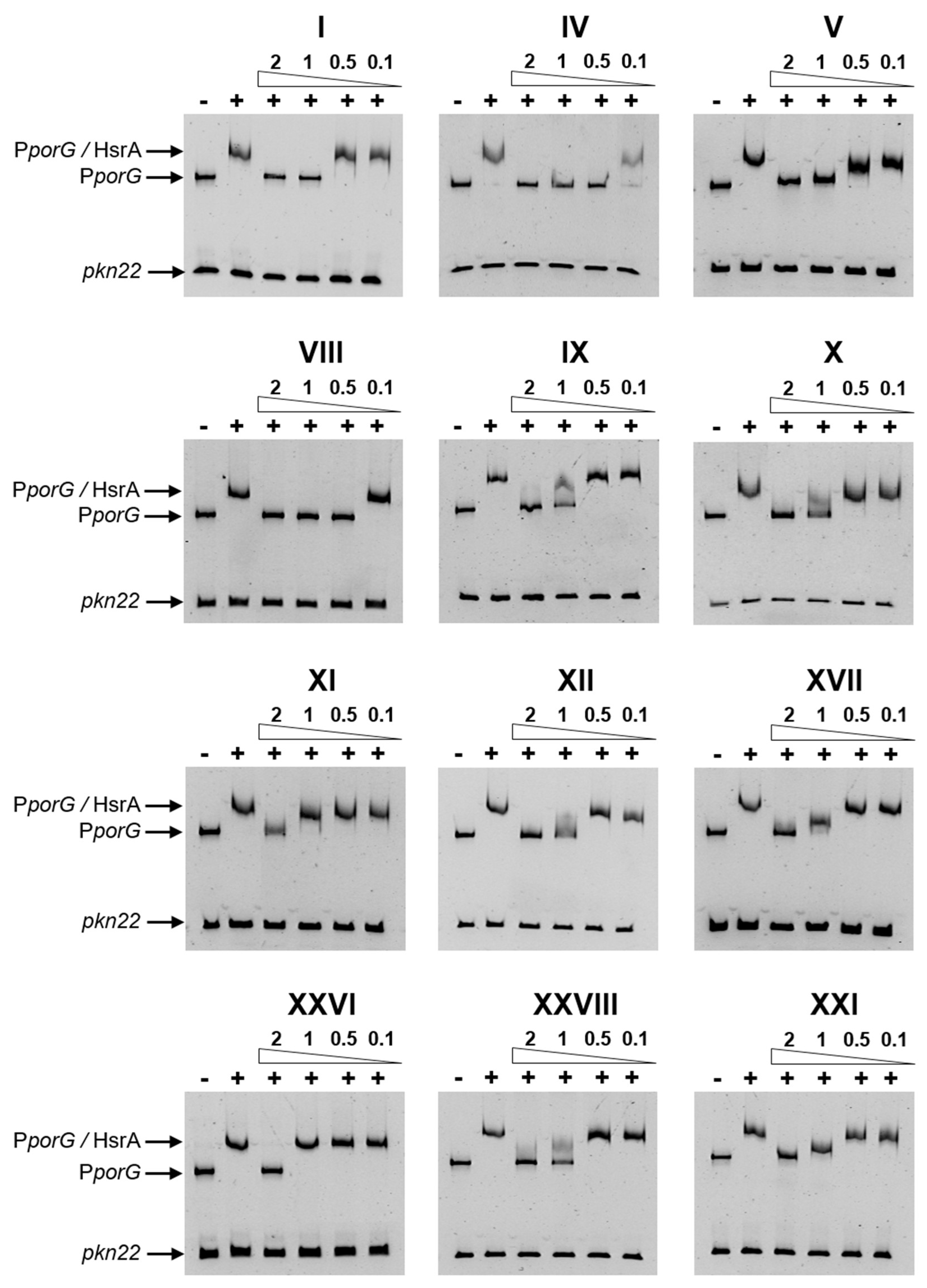

2.2. Several Drug-like Ligands of HsrA Inhibited Its DNA Binding Activity In Vitro

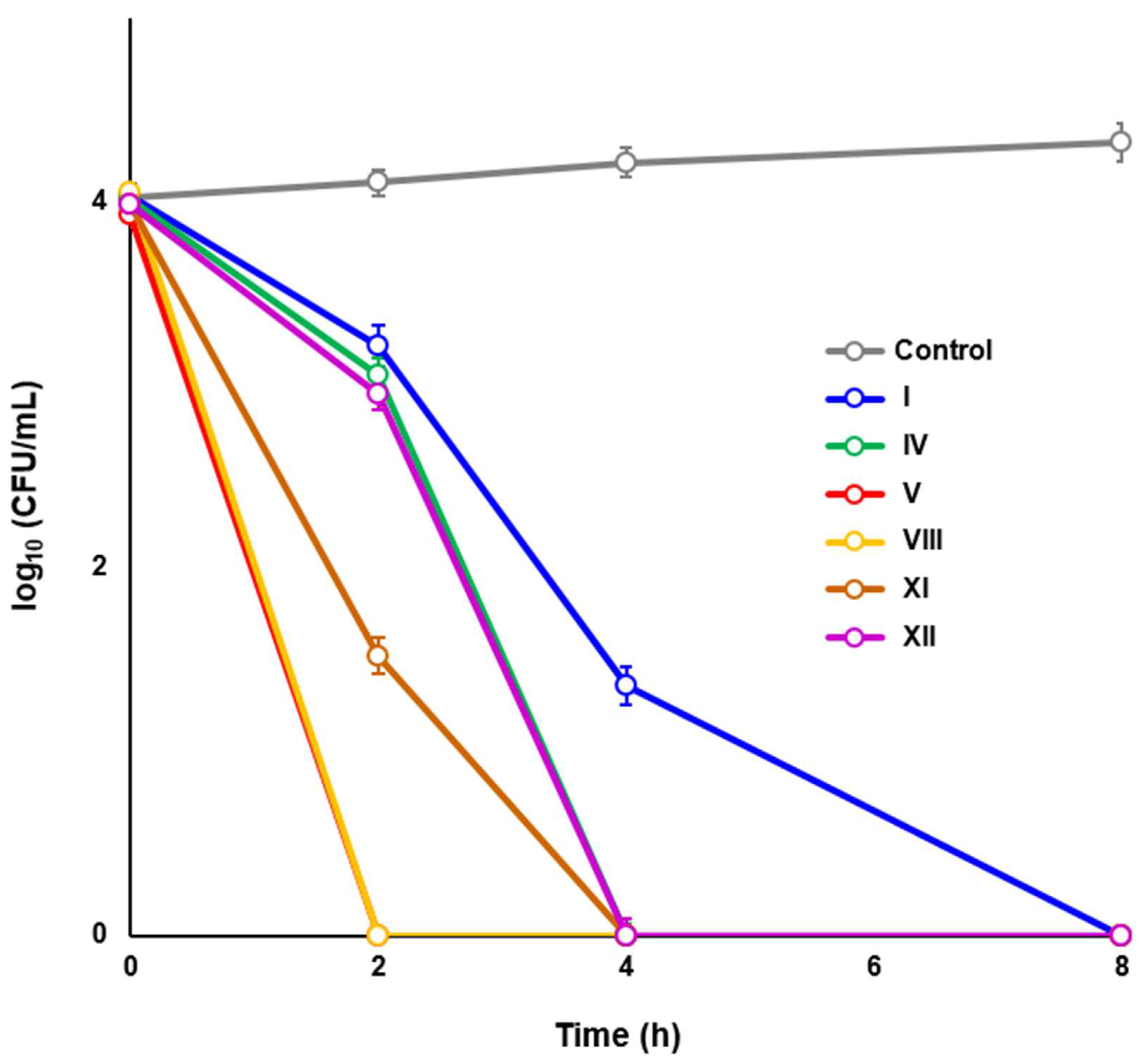

2.3. Novel HsrA Inhibitors Exhibited Potent Bactericidal Effects against H. pylori

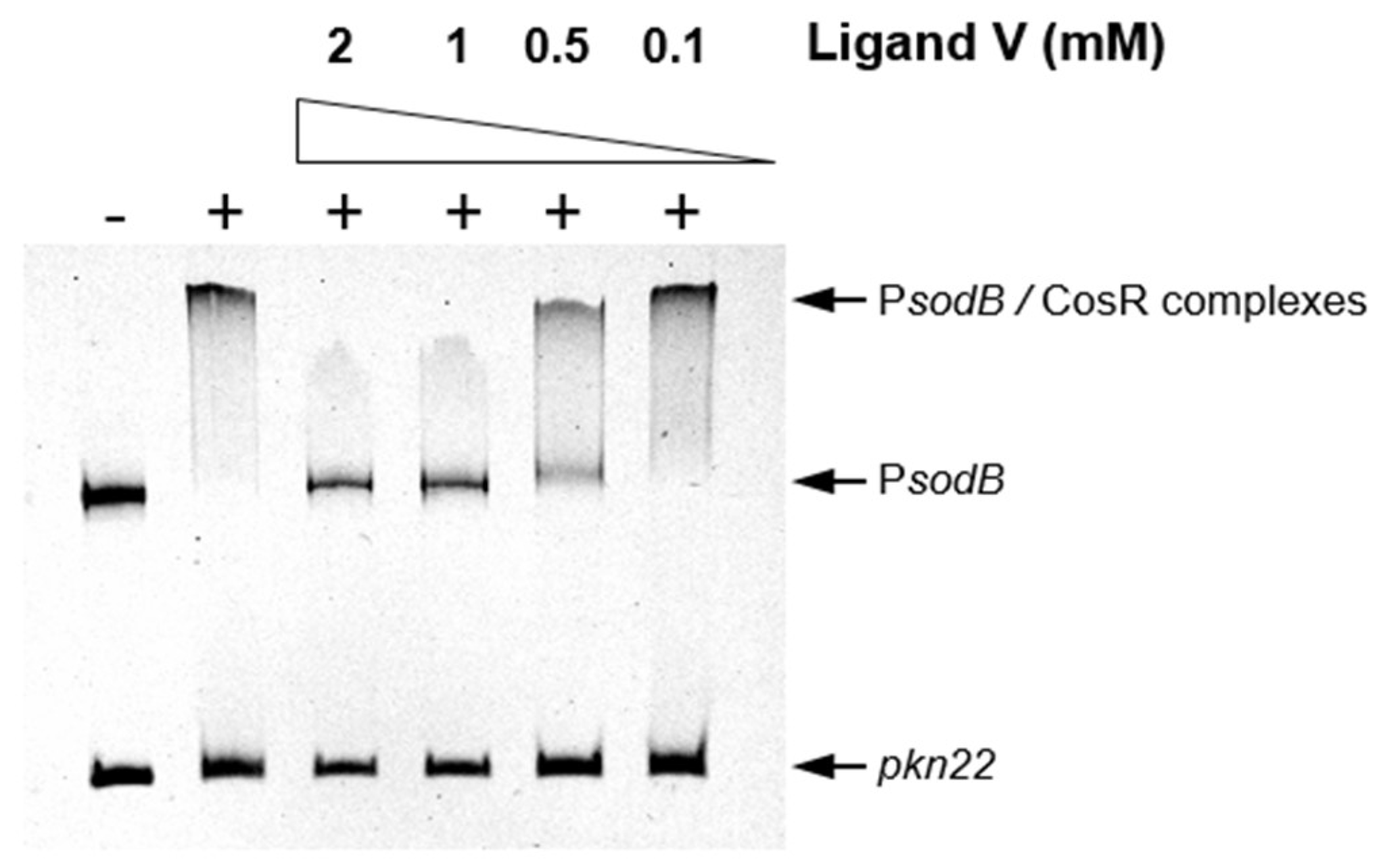

2.4. An HsrA Bactericidal Inhibitor Bound the HsrA Orthologue Protein CosR and Exhibited Strong Bactericidal Effect against C. jejuni

2.5. HsrA Bactericidal Inhibitors Exhibited Low Antimicrobial Actions against Gram-Positive and Gram-Negative Species of Human Microbiota

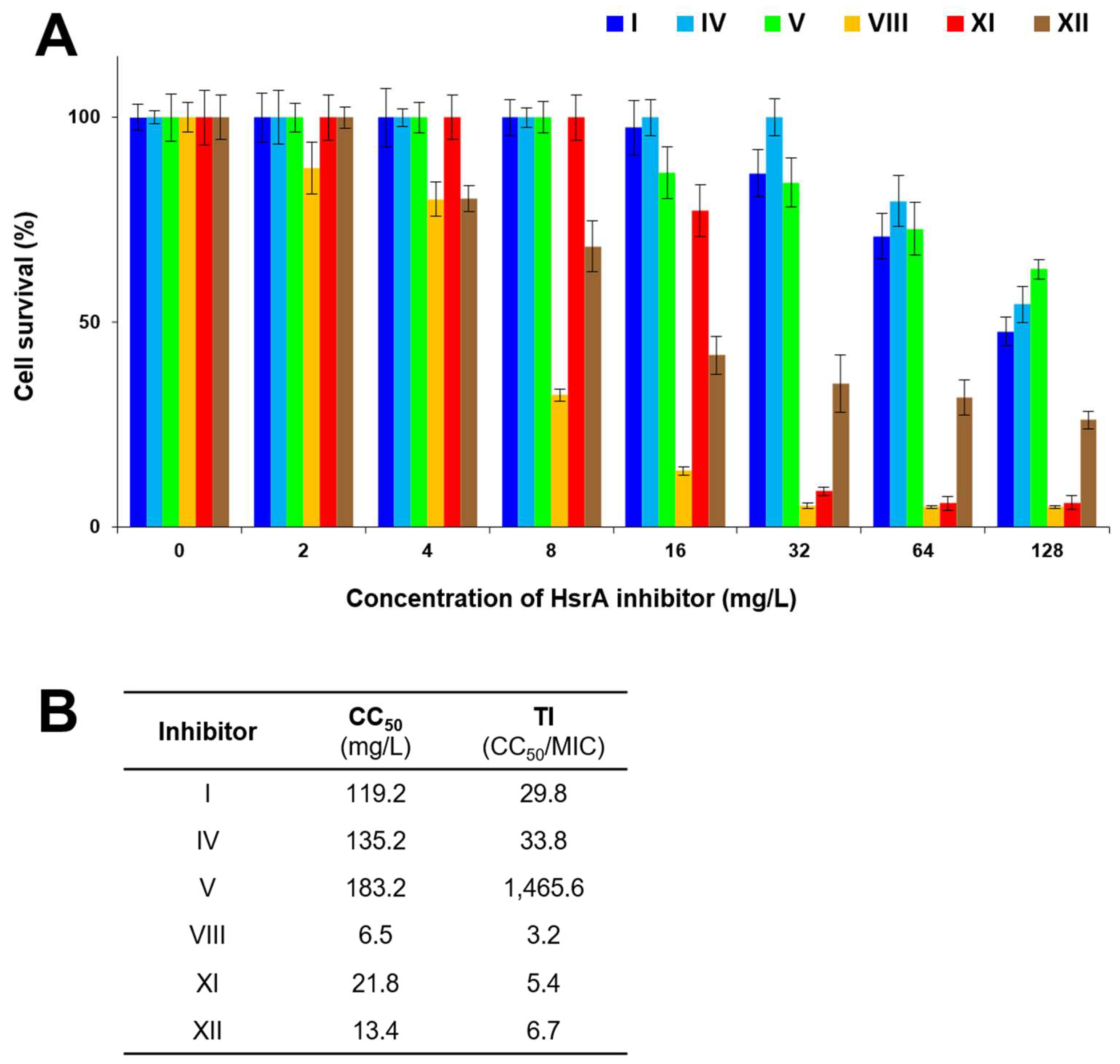

2.6. Cytotoxicity and Therapeutic Index

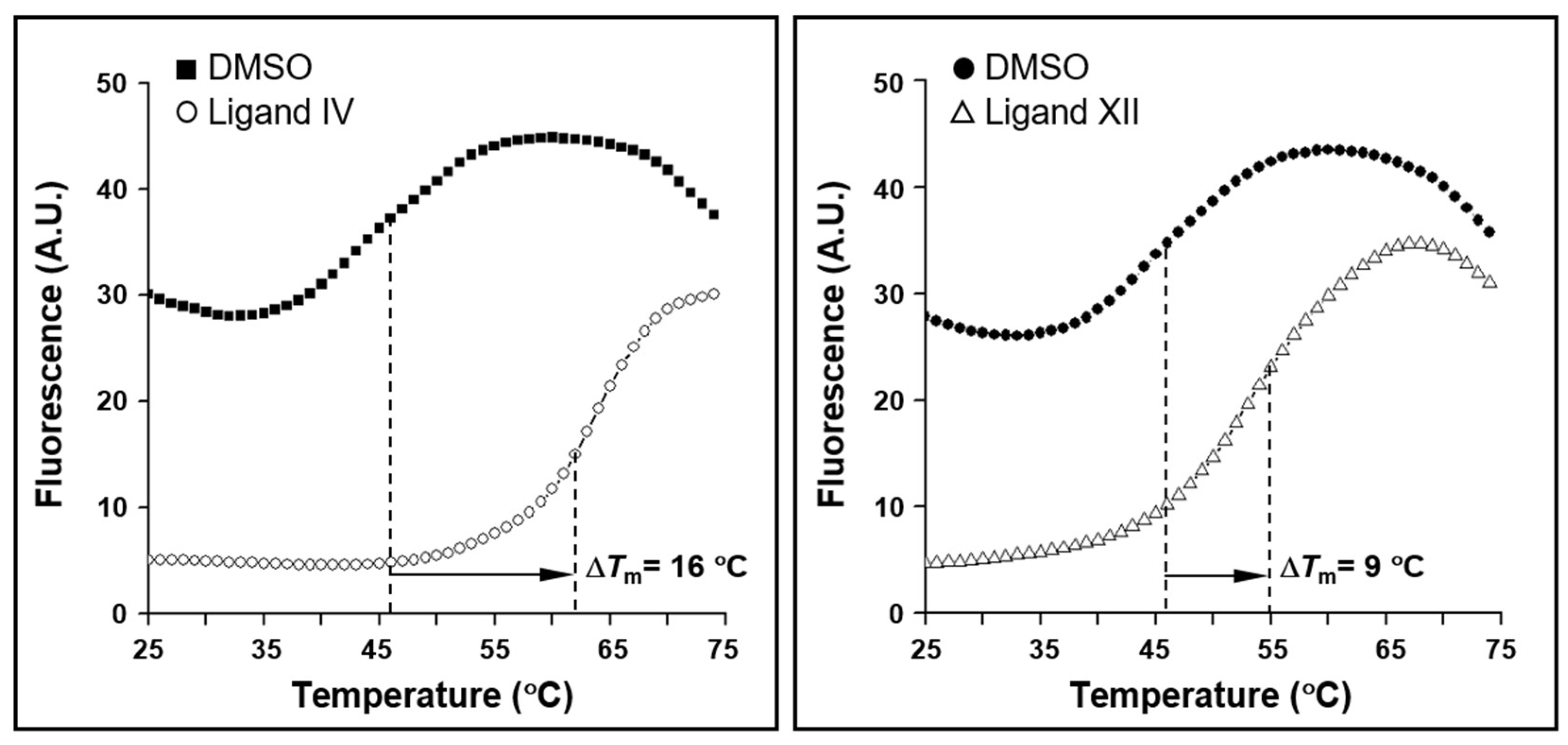

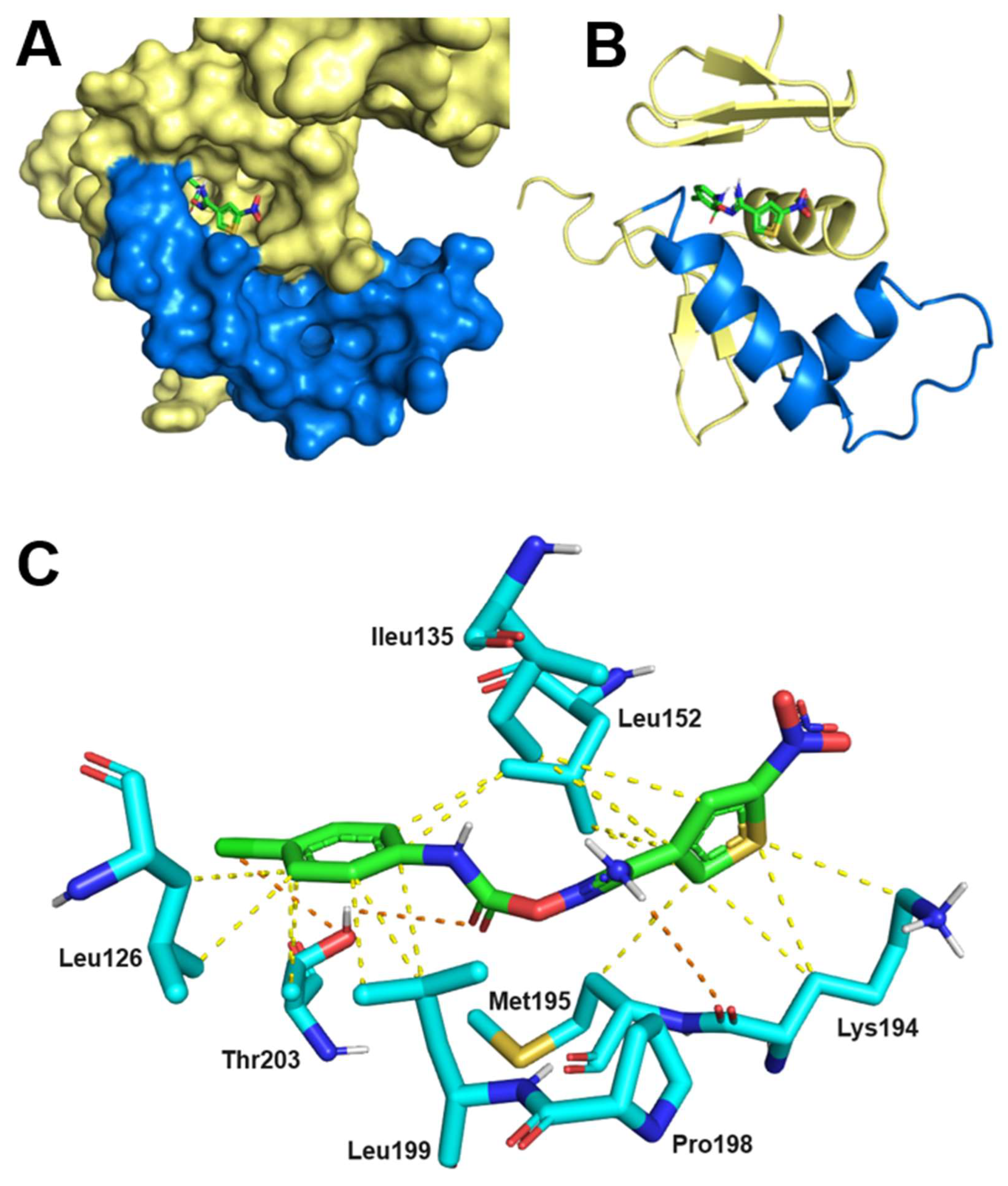

2.7. Thermodynamics and Predicted Models of HsrA-Inhibitor Interactions

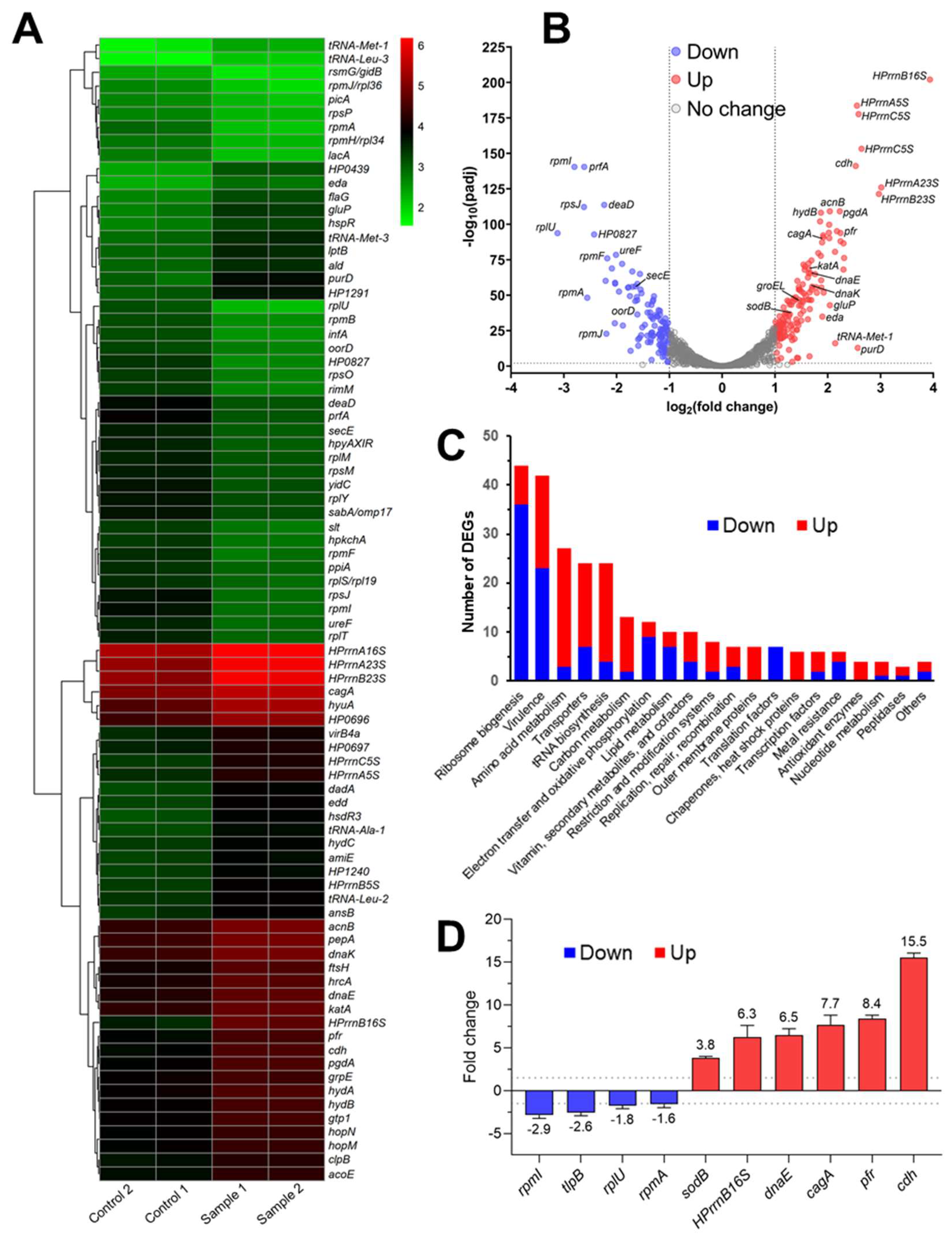

2.8. In Vivo Inhibition of HsrA Uncovered New Insights into the Essential Role of this Orphan Response Regulator

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Bacterial Strains and Culture Conditions

4.2. Chemicals

4.3. Recombinant Expression and Purification of Response Regulators

4.4. High-Throughput Screening

4.5. Electrophoretic Mobility Shift Assays

4.6. Minimal Inhibitory and Bactericidal Concentrations

4.7. Time-Kill Kinetic Assays

4.8. Checkerboard Assays

4.9. In Vivo Inhibition of HsrA

4.10. RNA Sequencing

4.11. Quantitative Real-Time PCR

4.12. Cytotoxicity and Therapeutic Index

4.13. Isothermal Titration Calorimetry

4.14. Molecular Docking

5. Patents

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Oren, A.; Garrity, G.M. Valid publication of the names of forty-two phyla of prokaryotes. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 2021, 71, 005056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusters, J.G.; van Vliet, A.H.; Kuipers, E.J. Pathogenesis of Helicobacter pylori infection. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2006, 19, 449–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamaoka, Y. Mechanisms of disease: Helicobacter pylori virulence factors. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2010, 7, 629–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franceschi, F.; Covino, M.; Roubaud Baudron, C. Review: Helicobacter pylori and extragastric diseases. Helicobacter 2019, 24 Suppl 1, e12636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooi, J.K.Y.; Lai, W.Y.; Ng, W.K.; Suen, M.M.Y.; Underwood, F.E.; Tanyingoh, D.; Malfertheiner, P.; Graham, D.Y.; Wong, V.W.S.; Wu, J.C.Y.; et al. Global prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection: systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastroenterology 2017, 153, 420–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wroblewski, L.E.; Peek, R.M., Jr.; Wilson, K.T. Helicobacter pylori and gastric cancer: factors that modulate disease risk. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2010, 23, 713–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moss, S.F. The clinical evidence linking Helicobacter pylori to gastric cancer. Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol 2017, 3, 183–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC). Schistosomes, liver flukes and Helicobacter pylori. IARC Monogr Eval Carcinog Risks Hum 1994, 61, 1–241. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, Y.; Zhang, M.; Lu, B.; Dai, J. Helicobacter pylori and antibiotic resistance, a continuing and intractable problem. Helicobacter 2016, 21, 349–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tshibangu-Kabamba, E.; Yamaoka, Y. Helicobacter pylori infection and antibiotic resistance - from biology to clinical implications. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2021, 18, 613–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, S.C.; Iyer, P.G.; Moss, S.F. AGA clinical practice update on the management of refractory Helicobacter pylori infection: expert review. Gastroenterology 2021, 160, 1831–1841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malfertheiner, P.; Megraud, F.; Rokkas, T.; Gisbert, J.P.; Liou, J.M.; Schulz, C.; Gasbarrini, A.; Hunt, R.H.; Leja, M.; O'Morain, C.; et al. Management of Helicobacter pylori infection: the Maastricht VI/Florence consensus report. Gut 2022, 71, 1724–1762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gisbert, J.P.; Alcedo, J.; Amador, J.; Bujanda, L.; Calvet, X.; Castro-Fernandez, M.; Fernandez-Salazar, L.; Gene, E.; Lanas, A.; Lucendo, A.J.; et al. V Spanish Consensus Conference on Helicobacter pylori infection treatment. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2022, 45, 392–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salcedo, J.A.; Al-Kawas, F. Treatment of Helicobacter pylori infection. Arch. Intern. Med. 1998, 158, 842–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arslan, N.; Yilmaz, O.; Demiray-Gurbuz, E. Importance of antimicrobial susceptibility testing for the management of eradication in Helicobacter pylori infection. World J Gastroenterol 2017, 23, 2854–2869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Yang, T.; Tang, H.; Tang, X.; Shen, Y.; Benghezal, M.; Tay, A.; Marshall, B. Helicobacter pylori infection is an infectious disease and the empiric therapy paradigm should be changed. Precis Clin Med 2019, 2, 77–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Megraud, F.; Bruyndonckx, R.; Coenen, S.; Wittkop, L.; Huang, T.D.; Hoebeke, M.; Benejat, L.; Lehours, P.; Goossens, H.; Glupczynski, Y.; et al. Helicobacter pylori resistance to antibiotics in Europe in 2018 and its relationship to antibiotic consumption in the community. Gut 2021, 70, 1815–1822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Francesco, V.; Zullo, A.; Manta, R.; Gatta, L.; Fiorini, G.; Saracino, I.M.; Vaira, D. Helicobacter pylori eradication following first-line treatment failure in Europe: What, how and when chose among different standard regimens? A systematic review. Eur. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2021, 33, e66–e70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savoldi, A.; Carrara, E.; Graham, D.Y.; Conti, M.; Tacconelli, E. Prevalence of antibiotic resistance in Helicobacter pylori: a systematic review and meta-analysis in World Health Organization regions. Gastroenterology 2018, 155, 1372–1382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sukri, A.; Hanafiah, A.; Yusoff, H.; Shamsul Nizam, N.A.; Nameyrra, Z.; Wong, Z.; Raja Ali, R.A. Multidrug-resistant Helicobacter pylori strains: a five-year surveillance study and its genome characteristics. Antibiotics (Basel) 2022, 11, 1391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, J.J.C.; Navarro, M.; Sawyer, K.; Elfanagely, Y.; Moss, S.F. Helicobacter pylori antibiotic resistance in the United States between 2011 and 2021: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2022, 117, 1221–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.E.; Park, M.I.; Park, S.J.; Moon, W.; Choi, Y.J.; Cheon, J.H.; Kwon, H.J.; Ku, K.H.; Yoo, C.H.; Kim, J.H.; et al. Trends in Helicobacter pylori eradication rates by first-line triple therapy and related factors in eradication therapy. Korean J. Intern. Med. 2015, 30, 801–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boyanova, L.; Evstatiev, I.; Yordanov, D.; Markovska, R.; Mitov, I. Three unsuccessful treatments of Helicobacter pylori infection by a highly virulent strain with quadruple antibiotic resistance. Folia Microbiol. (Praha) 2016, 61, 307–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tacconelli, E.; Carrara, E.; Savoldi, A.; Harbarth, S.; Mendelson, M.; Monnet, D.L.; Pulcini, C.; Kahlmeter, G.; Kluytmans, J.; Carmeli, Y.; et al. Discovery, research, and development of new antibiotics: the WHO priority list of antibiotic-resistant bacteria and tuberculosis. Lancet Infect Dis 2018, 18, 318–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, P.I.; Pan, C.Y.; Kao, J.Y.; Tsay, F.W.; Peng, N.J.; Kao, S.S.; Wang, H.M.; Tsai, T.J.; Wu, D.C.; Chen, C.L.; et al. Helicobacter pylori eradication with bismuth quadruple therapy leads to dysbiosis of gut microbiota with an increased relative abundance of Proteobacteria and decreased relative abundances of Bacteroidetes and Actinobacteria. Helicobacter 2018, 23, e12498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liou, J.M.; Chen, C.C.; Chang, C.M.; Fang, Y.J.; Bair, M.J.; Chen, P.Y.; Chang, C.Y.; Hsu, Y.C.; Chen, M.J.; Chen, C.C.; et al. Long-term changes of gut microbiota, antibiotic resistance, and metabolic parameters after Helicobacter pylori eradication: a multicentre, open-label, randomised trial. Lancet Infect Dis 2019, 19, 1109–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Q.; Shao, X.; Shen, R.; Chen, D.; Shen, J. Changes in the human gut microbiota composition caused by Helicobacter pylori eradication therapy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Helicobacter 2020, 25, e12713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Y.; Ye, Z.; Wang, Y.; Huang, Z.; Zheng, C.; Shi, J.; Tang, W.; Zhang, P.; Wang, S.; Huang, Y. Long-term changes in the gut microbiota after triple therapy, sequential therapy, bismuth quadruple therapy and concomitant therapy for Helicobacter pylori eradication in Chinese children. Helicobacter 2021, 26, e12809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trifan, A.; Girleanu, I.; Cojocariu, C.; Sfarti, C.; Singeap, A.M.; Dorobat, C.; Grigore, L.; Stanciu, C. Pseudomembranous colitis associated with a triple therapy for Helicobacter pylori eradication. World J Gastroenterol 2013, 19, 7476–7479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, S.; Chinda, D.; Yamai, K.; Satake, R.; Soma, Y.; Shimoyama, T.; Fukuda, S. A case of severe pseudomembranous colitis diagnosed by colonoscopy after Helicobacter pylori eradication. Clin J Gastroenterol 2014, 7, 247–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nei, T.; Hagiwara, J.; Takiguchi, T.; Yokobori, S.; Shiei, K.; Yokota, H.; Senoh, M.; Kato, H. Fatal fulminant Clostridioides difficile colitis caused by Helicobacter pylori eradication therapy; a case report. J Infect Chemother 2020, 26, 305–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hiraki, M.; Suzuki, R.; Tanaka, N.; Fukunaga, H.; Kinoshita, Y.; Kimura, H.; Tsutsui, S.; Murata, M.; Morita, S. Community-acquired fulminant Clostridioides (Clostridium) difficile infection by ribotype 027 isolate in Japan: a case report. Surg Case Rep 2021, 7, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melander, R.J.; Zurawski, D.V.; Melander, C. Narrow-spectrum antibacterial agents. Medchemcomm 2018, 9, 12–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spaulding, C.N.; Klein, R.D.; Schreiber, H.L.t.; Janetka, J.W.; Hultgren, S.J. Precision antimicrobial therapeutics: the path of least resistance? NPJ Biofilms Microbiomes 2018, 4, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alm, R.A.; Lahiri, S.D. Narrow-spectrum antibacterial agents-benefits and challenges. Antibiotics (Basel) 2020, 9, 418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, X.; Landick, R.; Campbell, E.A. A roadmap for designing narrow-spectrum antibiotics targeting bacterial pathogens. Microb Cell 2022, 9, 136–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diamantis, S.; Retur, N.; Bertrand, B.; Lieutier-Colas, F.; Carenco, P.; Mondain, V.; On Behalf Of Promise Professional Community Network On Antimicrobial, R. The production of antibiotics must be reoriented: repositioning old narrow-spectrum antibiotics, developing new microbiome-sparing antibiotics. Antibiotics (Basel) 2022, 11, 924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De la Fuente-Nunez, C.; Torres, M.D.; Mojica, F.J.; Lu, T.K. Next-generation precision antimicrobials: towards personalized treatment of infectious diseases. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2017, 37, 95–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paharik, A.E.; Schreiber, H.L.t.; Spaulding, C.N.; Dodson, K.W.; Hultgren, S.J. Narrowing the spectrum: the new frontier of precision antimicrobials. Genome Med 2017, 9, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, A.; Salillas, S.; Velázquez-Campoy, A.; Espinosa Angarica, V.; Fillat, M.F.; Sancho, J.; Lanas, Á. Identifying potential novel drugs against Helicobacter pylori by targeting the essential response regulator HsrA. Sci Rep 2019, 9, 11294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, A.; Casado, J.; Chueca, E.; Salillas, S.; Velázquez-Campoy, A.; Espinosa Angarica, V.; Benejat, L.; Guignard, J.; Giese, A.; Sancho, J.; et al. Repurposing dihydropyridines for treatment of Helicobacter pylori infection. Pharmaceutics 2019, 11, 681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- González, A.; Casado, J.; Gündüz, M.G.; Santos, B.; Velázquez-Campoy, A.; Sarasa-Buisan, C.; Fillat, M.F.; Montes, M.; Piazuelo, E.; Lanas, Á. 1,4-Dihydropyridine as a promising scaffold for novel antimicrobials against Helicobacter pylori. Front Microbiol 2022, 13, 874709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.M.; Hong, E.; Jeon, B.Y.; Kim, D.U.; Byun, J.S.; Lee, W.; Cho, H.S. Crystallization and preliminary X-ray crystallographic study of HP1043, a Helicobacter pylori orphan response regulator. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2006, 1764, 989–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casado, J.; Lanas, A.; González, A. Two-component regulatory systems in Helicobacter pylori and Campylobacter jejuni: Attractive targets for novel antibacterial drugs. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2022, 12, 977944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muller, S.; Pflock, M.; Schar, J.; Kennard, S.; Beier, D. Regulation of expression of atypical orphan response regulators of Helicobacter pylori. Microbiol. Res. 2007, 162, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delany, I.; Spohn, G.; Rappuoli, R.; Scarlato, V. Growth phase-dependent regulation of target gene promoters for binding of the essential orphan response regulator HP1043 of Helicobacter pylori. J. Bacteriol. 2002, 184, 4800–4810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olekhnovich, I.N.; Vitko, S.; Chertihin, O.; Hontecillas, R.; Viladomiu, M.; Bassaganya-Riera, J.; Hoffman, P.S. Mutations to essential orphan response regulator HP1043 of Helicobacter pylori result in growth-stage regulatory defects. Infect. Immun. 2013, 81, 1439–1449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olekhnovich, I.N.; Vitko, S.; Valliere, M.; Hoffman, P.S. Response to metronidazole and oxidative stress is mediated through homeostatic regulator HsrA (HP1043) in Helicobacter pylori. J. Bacteriol. 2014, 196, 729–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelliciari, S.; Pinatel, E.; Vannini, A.; Peano, C.; Puccio, S.; De Bellis, G.; Danielli, A.; Scarlato, V.; Roncarati, D. Insight into the essential role of the Helicobacter pylori HP1043 orphan response regulator: genome-wide identification and characterization of the DNA-binding sites. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 41063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beier, D.; Frank, R. Molecular characterization of two-component systems of Helicobacter pylori. J. Bacteriol. 2000, 182, 2068–2076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDaniel, T.K.; Dewalt, K.C.; Salama, N.R.; Falkow, S. New approaches for validation of lethal phenotypes and genetic reversion in Helicobacter pylori. Helicobacter 2001, 6, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lipinski, C.A.; Lombardo, F.; Dominy, B.W.; Feeney, P.J. Experimental and computational approaches to estimate solubility and permeability in drug discovery and development settings. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 2001, 46, 3–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lipinski, C.A. Lead- and drug-like compounds: the rule-of-five revolution. Drug Discov Today Technol 2004, 1, 337–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cremades, N.; Velázquez-Campoy, A.; Martínez-Júlvez, M.; Neira, J.L.; Pérez-Dorado, I.; Hermoso, J.; Jiménez, P.; Lanas, A.; Hoffman, P.S.; Sancho, J. Discovery of specific flavodoxin inhibitors as potential therapeutic agents against Helicobacter pylori infection. ACS Chem Biol 2009, 4, 928–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomb, J.F.; White, O.; Kerlavage, A.R.; Clayton, R.A.; Sutton, G.G.; Fleischmann, R.D.; Ketchum, K.A.; Klenk, H.P.; Gill, S.; Dougherty, B.A.; et al. The complete genome sequence of the gastric pathogen Helicobacter pylori. Nature 1997, 388, 539–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wuchty, S.; Muller, S.A.; Caufield, J.H.; Hauser, R.; Aloy, P.; Kalkhof, S.; Uetz, P. Proteome data improves protein function prediction in the interactome of Helicobacter pylori. Mol Cell Proteomics 2018, 17, 961–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velayudhan, J.; Hughes, N.J.; McColm, A.A.; Bagshaw, J.; Clayton, C.L.; Andrews, S.C.; Kelly, D.J. Iron acquisition and virulence in Helicobacter pylori: a major role for FeoB, a high-affinity ferrous iron transporter. Mol. Microbiol. 2000, 37, 274–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wai, S.N.; Nakayama, K.; Umene, K.; Moriya, T.; Amako, K. Construction of a ferritin-deficient mutant of Campylobacter jejuni: contribution of ferritin to iron storage and protection against oxidative stress. Mol. Microbiol. 1996, 20, 1127–1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waidner, B.; Greiner, S.; Odenbreit, S.; Kavermann, H.; Velayudhan, J.; Stahler, F.; Guhl, J.; Bisse, E.; van Vliet, A.H.; Andrews, S.C.; et al. Essential role of ferritin Pfr in Helicobacter pylori iron metabolism and gastric colonization. Infect. Immun. 2002, 70, 3923–3929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olczak, A.A.; Olson, J.W.; Maier, R.J. Oxidative-stress resistance mutants of Helicobacter pylori. J. Bacteriol. 2002, 184, 3186–3193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Hong, Y.; Olczak, A.; Maier, S.E.; Maier, R.J. Dual roles of Helicobacter pylori NapA in inducing and combating oxidative stress. Infect. Immun. 2006, 74, 6839–6846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Choi, H.; Leung, K.; Jiang, F.; Graham, D.Y.; Leung, W.K. Global prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection between 1980 and 2022: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol 2023, 8, 553–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.C.; Malfertheiner, P.; Yu, H.T.; Kuo, C.L.; Chang, Y.Y.; Meng, F.T.; Wu, Y.X.; Hsiao, J.L.; Chen, M.J.; Lin, K.P.; et al. Global prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection and incidence of gastric cancer between 1980 and 2022. Gastroenterology 2024, 166, 605–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morgan, E.; Arnold, M.; Camargo, M.C.; Gini, A.; Kunzmann, A.T.; Matsuda, T.; Meheus, F.; Verhoeven, R.H.A.; Vignat, J.; Laversanne, M.; et al. The current and future incidence and mortality of gastric cancer in 185 countries, 2020-40: A population-based modelling study. EClinicalMedicine 2022, 47, 101404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiang, T.H.; Chang, W.J.; Chen, S.L.; Yen, A.M.; Fann, J.C.; Chiu, S.Y.; Chen, Y.R.; Chuang, S.L.; Shieh, C.F.; Liu, C.Y.; et al. Mass eradication of Helicobacter pylori to reduce gastric cancer incidence and mortality: a long-term cohort study on Matsu Islands. Gut 2021, 70, 243–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, L.; Chen, Y.; Chen, F.; Tao, T.; Hu, Z.; Wang, J.; You, J.; Wong, B.C.Y.; Chen, J.; Ye, W. Effect of Helicobacter pylori eradication on gastric cancer prevention: updated report from a randomized controlled trial with 26.5 years of follow-up. Gastroenterology 2022, 163, 154–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.C.; Chiang, T.H.; Chou, C.K.; Tu, Y.K.; Liao, W.C.; Wu, M.S.; Graham, D.Y. Association between Helicobacter pylori eradication and gastric cancer incidence: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastroenterology 2016, 150, 1113–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyanova, L.; Hadzhiyski, P.; Gergova, R.; Markovska, R. Evolution of Helicobacter pylori resistance to antibiotics: a topic of increasing concern. Antibiotics (Basel) 2023, 12, 332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Guo, Q.; Yuan, Y.; Gong, Y. The antibiotic resistance of Helicobacter pylori to five antibiotics and influencing factors in an area of China with a high risk of gastric cancer. BMC Microbiol 2019, 19, 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, A.; Casado, J.; Lanas, A. Fighting the antibiotic crisis: flavonoids as promising antibacterial drugs against Helicobacter pylori infection. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2021, 11, 709749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, D.G.; May-Dracka, T.L.; Gagnon, M.M.; Tommasi, R. Trends and exceptions of physical properties on antibacterial activity for Gram-positive and Gram-negative pathogens. J. Med. Chem. 2014, 57, 10144–10161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolaric, A.; Kokot, M.; Hrast, M.; Weiss, M.; Zdovc, I.; Trontelj, J.; Zakelj, S.; Anderluh, M.; Minovski, N. A Fine-tuned lipophilicity/hydrophilicity ratio governs antibacterial potency and selectivity of bifurcated halogen bond-forming NBTIs. Antibiotics (Basel) 2021, 10, 862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kokot, M.; Weiss, M.; Zdovc, I.; Hrast, M.; Anderluh, M.; Minovski, N. Structurally optimized potent dual-targeting NBTI antibacterials with an enhanced bifurcated halogen-bonding propensity. ACS Med Chem Lett 2021, 12, 1478–1485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leus, I.V.; Adamiak, J.; Chandar, B.; Bonifay, V.; Zhao, S.; Walker, S.S.; Squadroni, B.; Balibar, C.J.; Kinarivala, N.; Standke, L.C.; et al. Functional diversity of Gram-negative permeability barriers reflected in antibacterial activities and intracellular accumulation of antibiotics. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2023, 67, e0137722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Surivet, J.P.; Zumbrunn, C.; Bruyere, T.; Bur, D.; Kohl, C.; Locher, H.H.; Seiler, P.; Ertel, E.A.; Hess, P.; Enderlin-Paput, M.; et al. Synthesis and characterization of tetrahydropyran-based bacterial topoisomerase inhibitors with antibacterial activity against Gram-negative bacteria. J. Med. Chem. 2017, 60, 3776–3794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blair, J.M.; Richmond, G.E.; Piddock, L.J. Multidrug efflux pumps in Gram-negative bacteria and their role in antibiotic resistance. Future Microbiol 2014, 9, 1165–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfaray, R.I.; Saruuljavkhlan, B.; Fauzia, K.A.; Torres, R.C.; Thorell, K.; Dewi, S.R.; Kryukov, K.A.; Matsumoto, T.; Akada, J.; Vilaichone, R.K.; et al. Global antimicrobial resistance gene study of Helicobacter pylori: comparison of detection tools, ARG and efflux pump gene analysis, worldwide epidemiological distribution, and information related to the antimicrobial-resistant phenotype. Antibiotics (Basel) 2023, 12, 1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Igwaran, A.; Okoh, A.I. Human campylobacteriosis: A public health concern of global importance. Heliyon 2019, 5, e02814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Facciola, A.; Riso, R.; Avventuroso, E.; Visalli, G.; Delia, S.A.; Lagana, P. Campylobacter: from microbiology to prevention. J Prev Med Hyg 2017, 58, E79–E92. [Google Scholar]

- Thepault, A.; Rose, V.; Queguiner, M.; Chemaly, M.; Rivoal, K. Dogs and cats: reservoirs for highly diverse Campylobacter jejuni and a potential source of human exposure. Animals (Basel) 2020, 10, 838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allos, B.M. Campylobacter jejuni infections: update on emerging issues and trends. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2001, 32, 1201–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Same, R.G.; Tamma, P.D. Campylobacter infections in children. Pediatr. Rev. 2018, 39, 533–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mizuno, S.; Yokoyama, K.; Nukada, T.; Ikeda, Y.; Hara, S. Campylobacter jejuni bacteremia in the term infant a rare cause of neonatal hematochezia. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 2022, 41, e156–e157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mearelli, F.; Casarsa, C.; Breglia, A.; Biolo, G. Septic shock with multi organ failure due to fluoroquinolones resistant Campylobacter jejuni. Am J Case Rep 2017, 18, 972–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eiland, L.S.; Jenkins, L.S. Optimal treatment of Campylobacter dysentery. J Pediatr Pharmacol Ther 2008, 13, 170–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luangtongkum, T.; Jeon, B.; Han, J.; Plummer, P.; Logue, C.M.; Zhang, Q. Antibiotic resistance in Campylobacter: emergence, transmission and persistence. Future Microbiol 2009, 4, 189–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolinger, H.; Kathariou, S. The current state of macrolide resistance in Campylobacter spp.: trends and impacts of resistance mechanisms. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2017, 83, e00416–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portes, A.B.; Panzenhagen, P.; Pereira Dos Santos, A.M.; Junior, C.A.C. Antibiotic resistance in Campylobacter: a systematic review of South American isolates. Antibiotics (Basel) 2023, 12, 548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDermott, P.F.; Bodeis, S.M.; Aarestrup, F.M.; Brown, S.; Traczewski, M.; Fedorka-Cray, P.; Wallace, M.; Critchley, I.A.; Thornsberry, C.; Graff, S.; et al. Development of a standardized susceptibility test for Campylobacter with quality-control ranges for ciprofloxacin, doxycycline, erythromycin, gentamicin, and meropenem. Microb Drug Resist 2004, 10, 124–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, S.; Kim, M.; Ryu, S.; Jeon, B. Regulation of oxidative stress response by CosR, an essential response regulator in Campylobacter jejuni. PLoS One 2011, 6, e22300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, S.; Zhang, Q.; Ryu, S.; Jeon, B. Transcriptional regulation of the CmeABC multidrug efflux pump and the KatA catalase by CosR in Campylobacter jejuni. J. Bacteriol. 2012, 194, 6883–6891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grinnage-Pulley, T.; Mu, Y.; Dai, L.; Zhang, Q. Dual repression of the multidrug efflux pump CmeABC by CosR and CmeR in Campylobacter jejuni. Front Microbiol 2016, 7, 1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, M.; Hwang, S.; Ryu, S.; Jeon, B. CosR regulation of perR transcription for the control of oxidative stress defense in Campylobacter jejuni. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaczanowska, M.; Ryden-Aulin, M. Ribosome biogenesis and the translation process in Escherichia coli. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2007, 71, 477–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stokes, J.M.; Selin, C.; Cardona, S.T.; Brown, E.D. Chemical inhibition of bacterial ribosome biogenesis shows efficacy in a worm infection model. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2015, 59, 2918–2920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farha, M.A.; Verschoor, C.P.; Bowdish, D.; Brown, E.D. Collapsing the proton motive force to identify synergistic combinations against Staphylococcus aureus. Chem. Biol. 2013, 20, 1168–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berube, B.J.; Parish, T. Combinations of respiratory chain inhibitors have enhanced bactericidal activity against Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2018, 62, e01677–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashyap, D.R.; Kuzma, M.; Kowalczyk, D.A.; Gupta, D.; Dziarski, R. Bactericidal peptidoglycan recognition protein induces oxidative stress in Escherichia coli through a block in respiratory chain and increase in central carbon catabolism. Mol. Microbiol. 2017, 105, 755–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stohl, E.A.; Criss, A.K.; Seifert, H.S. The transcriptome response of Neisseria gonorrhoeae to hydrogen peroxide reveals genes with previously uncharacterized roles in oxidative damage protection. Mol. Microbiol. 2005, 58, 520–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Deng, K.; Zaremba, S.; Deng, X.; Lin, C.; Wang, Q.; Tortorello, M.L.; Zhang, W. Transcriptomic response of Escherichia coli O157:H7 to oxidative stress. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2009, 75, 6110–6123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Committee for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST) of the European Society for Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases (ESCMID). EUCAST Discussion Document E. Dis 5.1: Determination of minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) of antibacterial agents by broth dilution. Clin Microbiol Infec 2003, 9, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Bolger, A.M.; Lohse, M.; Usadel, B. Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 2114–2120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Langmead, B.; Salzberg, S.L. Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nat Methods 2012, 9, 357–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liao, Y.; Smyth, G.K.; Shi, W. featureCounts: an efficient general purpose program for assigning sequence reads to genomic features. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 923–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Love, M.I.; Huber, W.; Anders, S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol 2014, 15, 550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livak, K.J.; Schmittgen, T.D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods 2001, 25, 402–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Amsterdam, K.; van Vliet, A.H.; Kusters, J.G.; Feller, M.; Dankert, J.; van der Ende, A. Induced Helicobacter pylori vacuolating cytotoxin VacA expression after initial colonisation of human gastric epithelial cells. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 2003, 39, 251–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitucha, M.; Wos, M.; Miazga-Karska, M.; Klimek, K.; Miroslaw, B.; Pachuta-Stec, A.; Gladysz, A.; Ginalska, G. Synthesis, antibacterial and antiproliferative potential of some new 1-pyridinecarbonyl-4-substituted thiosemicarbazide derivatives. Med Chem Res 2016, 25, 1666–1677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trott, O.; Olson, A.J. AutoDock Vina: improving the speed and accuracy of docking with a new scoring function, efficient optimization, and multithreading. J Comput Chem 2010, 31, 455–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labbe, C.M.; Pencheva, T.; Jereva, D.; Desvillechabrol, D.; Becot, J.; Villoutreix, B.O.; Pajeva, I.; Miteva, M.A. AMMOS2: a web server for protein-ligand-water complexes refinement via molecular mechanics. Nucleic Acids Res 2017, 45, W350–W355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forli, S.; Huey, R.; Pique, M.E.; Sanner, M.F.; Goodsell, D.S.; Olson, A.J. Computational protein-ligand docking and virtual drug screening with the AutoDock suite. Nat Protoc 2016, 11, 905–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

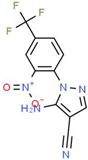

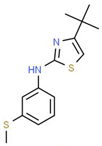

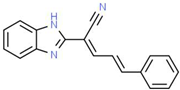

| Ligand | Chemical structure | Formula | Molecular Weight (Da) | log P1 | H-bond donors | H-bond acceptors | Lipinski violations | TPSA (Å)2 | Rotatable bonds | Log D3 |

| I |  |

C11H6F3N5O2 | 297.19 | 1.56 | 1 | 7 | 0 | 113.45 | 3 | 2.26 |

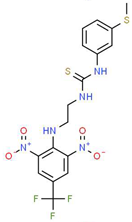

| IV |  |

C17H16F3N5O4S2 | 475.47 | 3.08 | 3 | 7 | 0 | 185.12 | 11 | 4.97 |

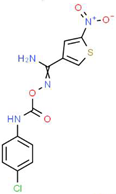

| V |  |

C12H9ClN4O4S | 340.74 | 1.99 | 2 | 5 | 0 | 150.77 | 6 | 2.92 |

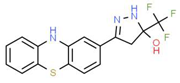

| VIII |  |

C16H12F3N3OS | 351.35 | 3.50 | 3 | 5 | 0 | 81.95 | 2 | 3.60 |

| XI |  |

C14H18N2S2 | 278.44 | 4.18 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 78.46 | 4 | 4.77 |

| XII |  |

C18H13N3 | 271.32 | 3.53 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 52.47 | 3 | 3.79 |

| Inhibitor or drug | MIC (MBC), mg/L | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

H. pylori ATCC 700392 (26695) |

H. pylori

ATCC 43504 (MTZ-R) |

H. pylori

ATCC 700684 (CLR-R) |

H. pylori

Donostia 2 (LVX-R) |

|

| I | 4 (4) | 1 (1) | 4 (4) | 2 (2) |

| IV | 2 (4) | 2 (4) | 4 (4) | 4 (4) |

| V | 0.063 (0.125) | 0.125 (0.125) | 0.031 (0.031) | 0.125 (0.125) |

| VIII | 1 (2) | 1 (2) | 1 (2) | 2 (2) |

| IX | 8 (16) | 4 (8) | 4 (8) | 8 (16) |

| X | 8 (16) | 8 (8) | 8 (8) | 8 (16) |

| XI | 4 (4) | 2 (4) | 2 (4) | 2 (4) |

| XII | 2 (2) | 0.5 (0.5) | 0.5 (0.5) | 1 (1) |

| XVII | 16 (16) | 4 (8) | 8 (8) | 8 (8) |

| XXVI | 16 (16) | 8 (8) | 8 (8) | 8 (16) |

| XXVIII | 32 (64) | 16 (16) | 32 (32) | 32 (32) |

| XXXI | > 64 (> 64) | 64 (64) | > 64 (> 64) | > 64 (> 64) |

| MTZ | 1 (2) | 64 (128) | 1 (2) | 8 (8) |

| CLR | < 0.03 (< 0.03) | < 0.03 (< 0.03) | 16 (32) | < 0.03 (< 0.03) |

| LVX | 0.12 (0.12) | 0.5 (0.5) | 0.12 (0.12) | 16 (32) |

| Antibiotic1 | HsrA inhibitor | FICantibiotic | FICinhibitor | FICI2 | Interaction3 |

| CLR | I | 1 | 1 | 2 | neutral |

| IV | 1 | 1 | 2 | neutral | |

| V | 0.5 | 0.06 | 0.56 | additive | |

| VIII | 0.5 | 0.03 | 0.53 | additive | |

| XI | 0.25 | 0.5 | 0.75 | additive | |

| XII | 0.25 | 0.5 | 0.75 | additive | |

| MTZ | I | 0.125 | 0.5 | 0.625 | additive |

| IV | 1 | 1 | 2 | neutral | |

| V | 0.125 | 0.5 | 0.625 | additive | |

| VIII | 0.5 | 0.125 | 0.625 | additive | |

| XI | 0.5 | 0.063 | 0.563 | additive | |

| XII | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.5 | synergism | |

| LVX | I | 1 | 1 | 2 | neutral |

| IV | 1 | 1 | 2 | neutral | |

| V | 1 | 1 | 2 | neutral | |

| VIII | 1 | 1 | 2 | neutral | |

| XI | 1 | 1 | 2 | neutral | |

| XII | 0.5 | 0.5 | 1 | neutral |

| Inhibitor or drug | MIC (MBC), mg/L | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

C. jejuni

ATCC 33560 |

E. coli

ATCC 25922 |

K. pneumoniae ATCC 700603 |

E. faecalis

ATCC 29212 |

S. aureus

ATCC 29213 |

S. epidermidis

ATCC 12228 |

S. agalactiae

ATCC 12386 |

|

| I | 32 (32) | >64 (>64) | >64 (>64) | >64 (>64) | >64 (>64) | >64 (>64) | 32 (64) |

| IV | 64 (>64) | >64 (>64) | >64 (>64) | >64 (>64) | >64 (>64) | >64 (>64) | >64 (>64) |

| V | 0.25 (0.5) | >64 (>64) | >64 (>64) | >64 (>64) | >64 (>64) | >64 (>64) | >64 (>64) |

| VIII | 16 (32) | >64 (>64) | >64 (>64) | 64 (64) | 16 (32) | 4 (4) | 16 (32) |

| XI | >64 (>64) | >64 (>64) | >64 (>64) | 64 (64) | 16 (32) | 16 (64) | 8 (8) |

| XII | 64 (>64) | >64 (>64) | >64 (>64) | >64 (>64) | >64 (>64) | >64 (>64) | >64 (>64) |

| LVX | < 0.12 (< 0.12) | N.D. | 0.5 (0.5) | N.D. | N.D. | N.D. | N.D. |

| AMP | N.D. | 4 (4) | N.D. | 4 (4) | 2 (4) | 4 (4) | 0.25 (0.5) |

| Inhibitor | ITC1 | Molecular Docking2 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n |

Kd (μM) |

ΔH (kcal/mol) |

ΔG (kcal/mol) |

Interacting Residues | |

| I | 1.0 | 13 | –1.2 | –6.7 | I121, I123, L126, I135, L152, L155, A156, R159, M195, L199, T203 |

| IV | 0.9 | 3.9 | –1.6 | –7.4 | I135, V142, V144, K145, G146, P148, L152, K194, P198 |

| V | 1.0 | 13 | –1.9 | –6.7 | L126, I135, L152, K194, M195, P198, L199, T203 |

| VIII | 0.9 | 10 | 0.8 | –6.8 | V144, K145, G146, F149, L152, I191, K194, M195 |

| XI | 1.1 | 49 | –3.1 | –5.9 | I123, I128, L152, R159, D160, M195, L199, T203, C215, Y216 |

| XII | 1.0 | 43 | 0.8 | –6.0 | I123, L126, I128, I135, L152, M195, P198, L199, T203 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).