Submitted:

05 September 2024

Posted:

05 September 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

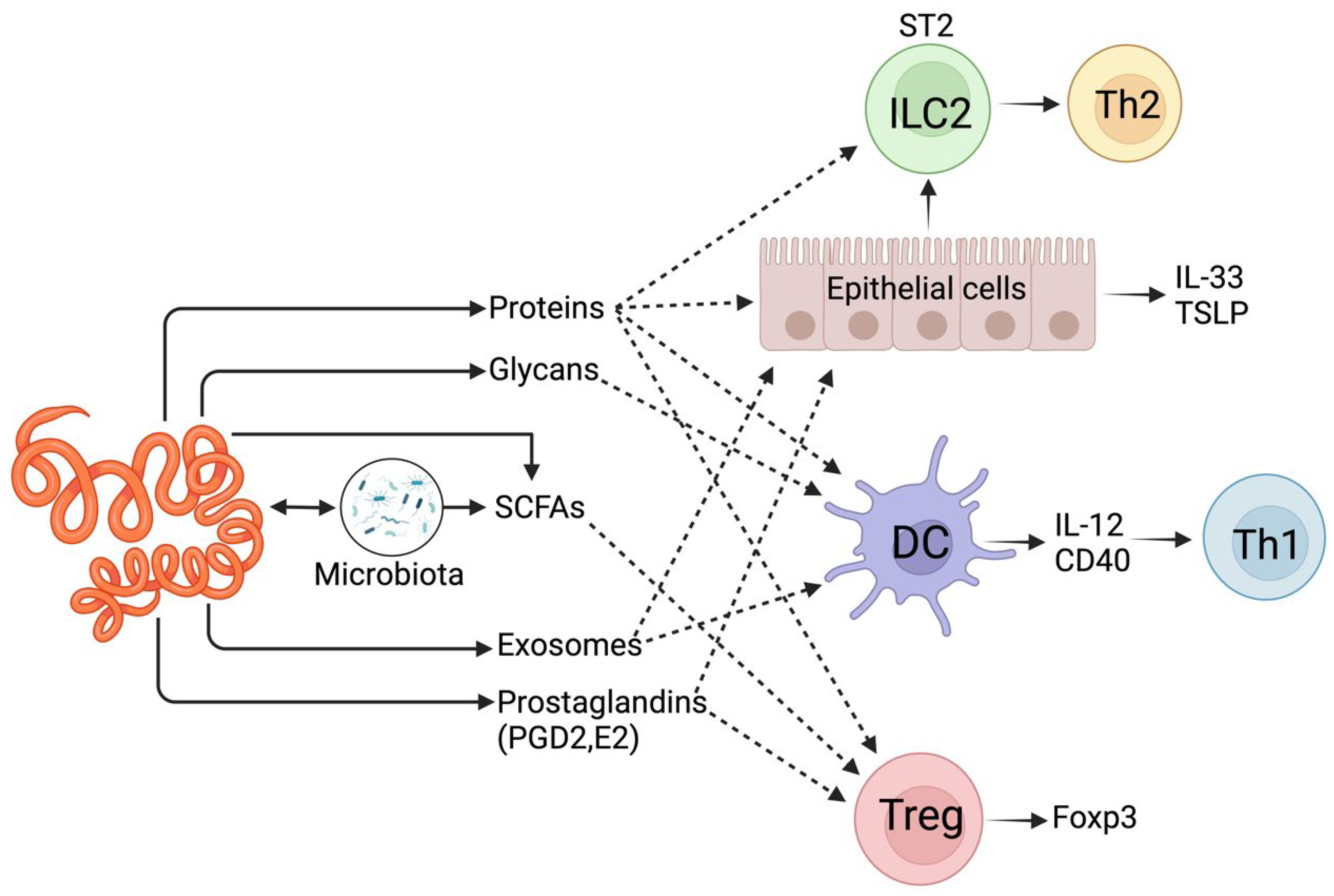

2. Gastrointestinal Parasite Interaction with Animal Hosts Using Small Molecules

3. Metabolomic Techniques Used for Studying GIP Isolated from Animal Hosts

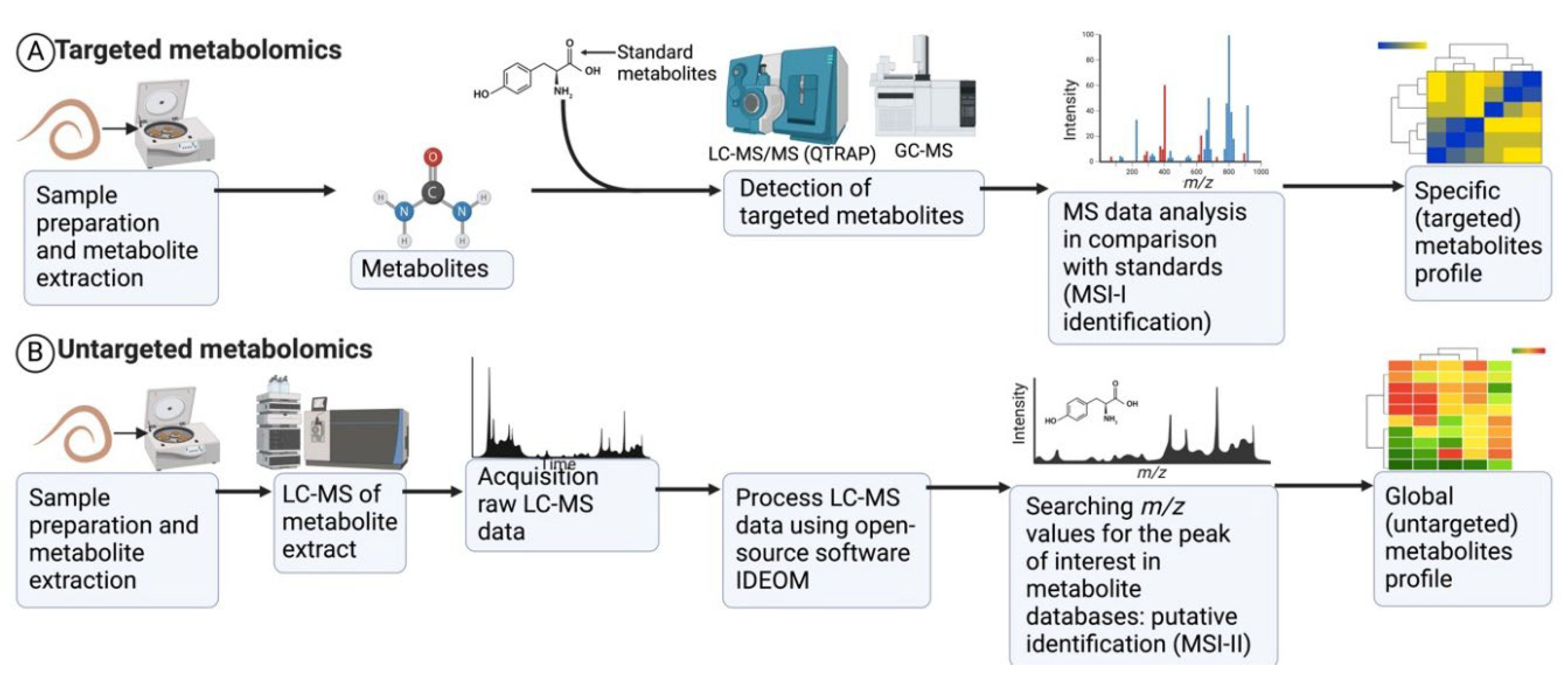

4. Different Metabolomics Study Approaches and Metabolite Identification Levels

4.1. Approaches

4.2. Metabolite Databases and Metabolite Identification Levels

4.2.1. Metabolite Databases

4.2.2. Metabolite Identification Levels

5. Artificial Intelligence (AI)-Assisted Software and Statistical Tools for Metabolomics Data Analysis

6. Conclusions

Informed Consent Statement: Not applicable.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zakeri, A.; Hansen, E.P.; Andersen, S.D.; Williams, A.R.; Nejsum, P. Immunomodulation by helminths: Intracellular pathways and extracellular vesicles. Front Immunol 2018, 9, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gowda, G.A.N.; Zhang, S.; Gu, H.; Asiago, V.; Shanaiah, N.; Raftery, D. Metabolomics-based methods for early disease diagnostics. Expert Review of Molecular Diagnostics 2008, 8, 617–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez de Souza, L.; Alseekh, S.; Scossa, F.; Fernie, A.R. Ultra-high-performance liquid chromatography high-resolution mass spectrometry variants for metabolomics research. Nat Methods 2021, 18, 733–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryan, S.M.; Eichenberger, R.M.; Ruscher, R.; Giacomin, P.R.; Loukas, A. Harnessing helminth-driven immunoregulation in the search for novel therapeutic modalities. PLoS Pathog 2020, 16, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yeshi, K.; Ruscher, R.; Loukas, A.; Wangchuk, P. Immunomodulatory and biological properties of helminth-derived small molecules: Potential applications in diagnostics and therapeutics. Frontiers in Parasitology 2022, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeshi, K.; Ruscher, R.; Hunter, L.; Daly, N.L.; Loukas, A.; Wangchuk, P. Revisiting inflammatory bowel disease: pathology, treatments, challenges and emerging therapeutics including drug leads from natural products. J Clin Med 2020, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preidis, G.A.; Hotez, P.J. The newest ″omics″–metagenomics and metabolomics–enter the battle against the neglected tropical diseases. PLoS Neglected Trop. Dis. 2015, 9, e0003382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newgard, C.B. Metabolomics and Metabolic Diseases: Where Do We Stand? Cell Metab 2017, 25, 43–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrick, L.M.; Shomron, N. AI/ML-driven advances in untargeted metabolomics and exposomics for biomedical applications. Cell Rep Phys Sci 2022, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galal, A.; Talal, M.; Moustafa, A. Applications of machine learning in metabolomics: Disease modeling and classification. Front Genet 2022, 13, 1017340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhall, D.; Kaur, R.; Juneja, M. Machine learning: A review of the algorithms and its applications. In Proceedings of the ICRIC 2019; 2020; pp. 47–63. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.D.; Xue, C.; Kolachalama, V.B.; Donald, W.A. Interpretable Machine Learning on Metabolomics Data Reveals Biomarkers for Parkinson’s Disease. ACS Central Science 2023, 9, 1035–1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loke, P.; Harris, N.L. Networking between helminths, microbes, and mammals. Cell Host Microbe 2023, 31, 464–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hotez, P.J.; Brindley, P.J.; Bethony, J.M.; King, C.H.; Pearce, E.J.; Jacobson, J. Helminth infections: the great neglected tropical diseases. J Clin Invest 2008, 118, 1311–1321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arpaia, N.; Campbell, C.; Fan, X.; Dikiy, S.; van der Veeken, J.; deRoos, P.; Liu, H.; Cross, J.R.; Pfeffer, K.; Coffer, P.J.; Rudensky, A.Y. Metabolites produced by commensal bacteria promote peripheral regulatory T-cell generation. Nature 2013, 504, 451–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslowski, K.M.; Vieira, A.T.; Ng, A.; Kranich, J.; Sierro, F.; Di, Y.; Schilter, H.C.; Rolph, M.S.; Mackay, F.; Artis, D.; et al. Regulation of inflammatory responses by gut microbiota and chemoattractant receptor GPR43. Nature 2009, 461, 1282–1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trompette, A.; Gollwitzer, E.S.; Yadava, K.; Sichelstiel, A.K.; Sprenger, N.; Ngom-Bru, C.; Blanchard, C.; Junt, T.; Nicod, L.P.; Harris, N.L.; Marsland, B.J. Gut microbiota metabolism of dietary fiber influences allergic airway disease and hematopoiesis. Nat Med 2014, 20, 159–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tielens, A.G.M.; van Grinsven, K.W.A.; Henze, K.; van Hellemond, J.J.; Martin, W. Acetate formation in the energy metabolism of parasitic helminths and protists. Int. J. Parasitol. 2010, 40, 387–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaiss, Mario M. ; Rapin, A.; Lebon, L.; Dubey, Lalit K.; Mosconi, I.; Sarter, K.; Piersigilli, A.; Menin, L.; Walker, Alan W.; Rougemont, J.; et al. The Intestinal Microbiota Contributes to the Ability of Helminths to Modulate Allergic Inflammation. Immunity 2015, 43, 998–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, P.F. Aspects of helminth metabolism. Parasitology 1982, 84, 177–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wangchuk, P.; Kouremenos, K.; Eichenberger, R.M.; Pearson, M.; Susianto, A.; Wishart, D.S.; McConville, M.J.; Loukas, A. Metabolomic profiling of the excretory-secretory products of hookworm and whipworm. Metabolomics 2019, 15, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.X.; Buhlmann, J.E.; Weller, P.F. Release of prostaglandin E2bymicrofilariae of Wuchereria bancrofti and Brugia malayi. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 1992, 46, 520–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brattig, N.W.; Schwohl, A.; Rickert, R.; Büttner, D.W. The filarial parasite Onchocerca volvulus generates the lipid mediator prostaglandin E2. Microbes Infect. 2006, 8, 873–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramaswamy, K.; Kumar, P.; He, Y.-X. A Role for Parasite-Induced PGE2 in IL-10-Mediated Host Immunoregulation by Skin Stage Schistosomula of Schistosoma mansoni1. The Journal of Immunology 2000, 165, 4567–4574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ofir-Birin, Y.; Regev-Rudzki, N. Extracellular vesicles in parasite survival. Science 2019, 363, 817–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, L.; Liu, J.; Cheng, G. Role of microRNAs in schistosomes and schistosomiasis. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2014, 4, 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rochat, B. Proposed confidence scale and ID score in the identification of known-unknown compounds using high resolution MS data. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 2017, 28, 709–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gika, H.G.; Theodoridis, G.A.; Plumb, R.S.; Wilson, I.D. Current practice of liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry in metabolomics and metabonomics. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2014, 87, 12–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cajka, T.; Vaclavikova, M.; Dzuman, Z.; Vaclavik, L.; Ovesna, J.; Hajslova, J. Rapid LC-MS-based metabolomics method to study the Fusarium infection of barley. J. Sep. Sci. 2014, 37, 912–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pezzatti, J.; Boccard, J.; Codesido, S.; Gagnebin, Y.; Joshi, A.; Picard, D.; Gonzalez-Ruiz, V.; Rudaz, S. Implementation of liquid chromatography-high resolution mass spectrometry methods for untargeted metabolomic analyses of biological samples: A tutorial. Anal Chim Acta 2020, 1105, 28–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, M.S.; de Oliveira, D.N.; de Oliveira, R.N.; Allegretti, S.M.; Catharino, R.R. Screening the life cycle of Schistosoma mansoni using high-resolution mass spectrometry. Anal Chim Acta 2014, 845, 62–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plumb, R.; Castro-Perez, J.; Granger, J.; Beattie, I.; Joncour, K.; Wright, A. Ultra-performance liquid chromatography coupled to quadrupole-orthogonal time-of-flight mass spectrometry. Rapid Commun Mass Spectrom 2004, 18, 2331–2337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeshi, K.; Creek, D.J.; Anderson, D.; Ritmejerytė, E.; Becker, L.; Loukas, A.; Wangchuk, P. Metabolomes and lipidomes of the infective stages of the gastrointestinal nematodes, Nippostrongylus brasiliensis and Trichuris muris. Metabolites 2020, 10, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wangchuk, P.; Kouremenos, K.; Eichenberger, R.M.; Pearson, M.; Susianto, A.; Wishart, D.S.; McConville, M.J.; Loukas, A. Metabolomic profiling of the excretory-secretory products of hookworm and whipworm. Metabolomics 2019, 15, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shulaev, V. Metabolomics technology and bioinformatics. Brief Bioinform 2006, 7, 128–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dettmer, K.; Aronov, P.A.; Hammock, B.D. Mass spectrometry-based metabolomics. Mass Spectrom Rev 2007, 6, 51–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunn, W.B. Current trends and future requirements for the mass spectrometric investigation of microbial, mammalian and plant metabolomes. Phys Biol 2008, 5, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, Z.; Huhman, D.V.; Sumner, L.W. Mass spectrometry strategies in metabolomics. J Biol Chem 2011, 286, 25435–25442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ginger, C.D.; Fairbairn, D. Lipid metabolism in helminth parasites. I. The lipids of Hymenolepis diminuta (cestoda). J Parasitol 1966, 52, 1086–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadjsombati, M.S.; McGinty, J.W.; Lyons-Cohen, M.R.; Jaffe, J.B.; DiPeso, L.; Schneider, C.; Miller, C.N.; Pollack, J.L.; Nagana Gowda, G.A.; Fontana, M.F.; et al. Detection of succinate by intestinal tuft cells triggers a type 2 innate immune circuit. Immunity 2018, 49, 33–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitman, J.D.; Sakanari, J.A.; Mitreva, M. Areas of metabolomic exploration for helminth infections. ACS Infect Dis 2021, 7, 206–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokova, D.; Mayboroda, O.A. Twenty Years on: Metabolomics in helminth research. Trends Parasitol 2019, 35, 282–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferreira, M.S.; de Oliveira, D.N.; de Oliveira, R.N.; Allegretti, S.M.; Vercesi, A.E.; Catharino, R.R. Mass spectrometry imaging: a new vision in differentiating Schistosoma mansoni strains. J Mass Spectrom 2014, 49, 86–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, M.S.; de Oliveira, R.N.; de Oliveira, D.N.; Esteves, C.Z.; Allegretti, S.M.; Catharino, R.R. Revealing praziquantel molecular targets using mass spectrometry imaging: an expeditious approach applied to Schistosoma mansoni. Int J Parasitol 2015, 45, 385–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadesch, P.; Quack, T.; Gerbig, S.; Grevelding, C.G.; Spengler, B. Tissue- and sex-specific lipidomic analysis of Schistosoma mansoni using high-resolution atmospheric pressure scanning microprobe matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization mass spectrometry imaging. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2020, 14, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nielen, M.W. MALDI time-of-flight mass spectrometry of synthetic polymers. Mass Spectrom Rev 1999, 18, 309–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Winefordner, J.D.E. MALDI mass spectrometry for synthetic polymer analysis. chemical analysis: a eeries of monographs on analytical chemistry and its applications, John Wiley & Sons, Inc, Hoboken, New Jersey, USA. 2009.

- Khalil, S.M.; Pretzel, J.; Becker, K.; Spengler, B. High-resolution AP-SMALDI mass spectrometry imaging of Drosophila melanogaster. Int J Mass Spectrom 2017, 416, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liigand, P.; Kaupmees, K.; Haav, K.; Liigand, J.; Leito, I.; Girod, M.; Antoine, R.; Kruve, A. Think Negative: Finding the best electrospray ionization/MS mode for your analyte. Anal Chem 2017, 89, 5665–5668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cech, N.B.; Enke, C.G. Practical implications of some recent studies in electrospray ionization fundamentals. Mass Spectrom Rev 2001, 20, 362–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, R.B. Electrospray and MALDI Mass Spectrometry: fundamentals, instrumentation, practicalities, and biological applications; Wiley: Hoboken. 2010.

- Giera, M.; Kaisar, M.M.M.; Derks, R.J.E.; Steenvoorden, E.; Kruize, Y.C.M.; Hokke, C.H.; Yazdanbakhsh, M.; Everts, B. The Schistosoma mansoni lipidome: Leads for immunomodulation. Anal Chim Acta 2018, 1037, 107–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangmee, S.; Adisakwattana, P.; Tipthara, P.; Simanon, N.; Sonthayanon, P.; Reamtong, O. Lipid profile of Trichinella papuae muscle-stage larvae. Sci Rep 2020, 10, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Nie, S.; Ma, G.; Korhonen, P.K.; Koehler, A.V.; Ang, C.S.; Reid, G.E.; Williamson, N.A.; Gasser, R.B. The developmental lipidome of Haemonchus contortus. Int J Parasitol 2018, 48, 887–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wangchuk, P.; Lavers, O.; Wishart, D.S.; Loukas, A. Excretory/secretory metabolome of the zoonotic roundworm parasite Toxocara canis. Biomolecules 2020, 10, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wangchuk, P.; Shepherd, C.; Constantinoiu, C.; Ryan, R.Y.M.; Kouremenos, K.A.; Becker, L.; Jones, L.; Buitrago, G.; Giacomin, P.; Wilson, D.; et al. Hookworm-derived metabolites suppress pathology in a mouse model of colitis and inhibit secretion of key inflammatory cytokines in primary human leukocytes. Infect. Immun. 2019, 87, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, T.; Nie, S.; Ma, G.; Vlaminck, J.; Geldhof, P.; Williamson, N.A.; Reid, G.E.; Gasser, R.B. Quantitative lipidomic analysis of Ascaris suum. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2020, 14, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greichus, A.; Greichus, Y.A. Chemical composition and volatile fatty acid production of male Ascaris lumbricoides before and after starvation. Exp Parasitol 1966, 19, 85–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melo, C.F.; Esteves, C.Z.; de Oliveira, R.N.; Guerreiro, T.M.; de Oliveira, D.N.; Lima, E.O.; Mine, J.C.; Allegretti, S.M.; Catharino, R.R. Early developmental stages of Ascaris lumbricoides featured by high-resolution mass spectrometry. Parasitol Res 2016, 115, 4107–4114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, V.P.; Selkirk, M.E.; Gounaris, K. Identification and composition of lipid classes in surface and somatic preparationss of adult Brugia malayi. Mol Biochem Parasitol 1996, 78, 105–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, A.-C.; Willenberg, I.; Springer, A.; Schebb, N.H.; Steinberg, P.; Strube, C. Fatty acid composition of free-living and parasitic stages of the bovine lungworm Dictyocaulus viviparus. Mol Biochem Parasitol 2017, 216, 39–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wangchuk, P.; Constantinoiu, C.; Eichenberger, R.M.; Field, M.; Loukas, A. Characterization of tapeworm metabolites and their reported biological activities. Molecules 2019, 24, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritler, D.; Rufener, R.; Li, J.V.; Kämpfer, U.; Müller, J.; Bühr, C.; Schürch, S.; Lundström-Stadelmann, B. In vitro metabolomic footprint of the Echinococcu multilocularis metacestode. Sci Rep. [CrossRef]

- Wangchuk, P.; Anderson, D.; Yeshi, K.; Loukas, A. Identification of small molecules of the infective stage of human hookworm using LCMS-based metabolomics and lipidomics protocols. ACS Infect Dis 2021, 7, 3264–3276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Zhang, M.; Ding, X.; Yang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Fan, Y.; Dai, Y.; Wang, J. Mining anti-Inflammation molecules from Nippostrongylus brasiliensis-derived products through the metabolomics approach. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2021, 11, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joachim, A.; Ryll, M.; Daugschies, A. Fatty acid patterns of different stages of Oesophagostomum dentatum and Oesophagostomum quadrispinulatum as revealed by gas chromatography. Int J Parasitol 2000, 30, 819–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Retra, K.; deWalick, S.; Schmitz, M.; Yazdanbakhsh, M.; Tielens, A.G.; Brouwers, J.F.; van Hellemond, J.J. The tegumental surface membranes of Schistosoma mansoni are enriched in parasite-specific phospholipid species. Int J Parasitol 2015, 45, 629–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Minematsu, T.; Yamazaki, S.; Uji, Y.; Okabe, H.; Korenaga, M.; Tada, I. Analysis of polyunsaturated fatty acid composition of Strongyloides ratti in relation to development. J Helminthol 1990, 64, 303–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Learmonth, M.P.; Euerby, M.R.; Jacobs, D.E.; Gibbons, W.A. Metabolite mapping of Toxocara canis using one- and two-dimensional proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Mol Biochem Parasitol 1987, 25, 293–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiehn, O. Metabolomics—The link between genotypes and phenotypes. Plant Mol Biol 2002, 48, 155–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, L.P.; Northen, T.R. Exometabolomics and MSI: deconstructing how cells interact to transform their small molecule environment. Curr Opin Biotechnol 2015, 34, 209–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mapelli, V.; Olsson, L.; Nielsen, J. Metabolic footprinting in microbiology: methods and applications in functional genomics and biotechnology. Trends in Biotechnology 2008, 26, 490–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribbenstedt, A.; Ziarrusta, H.; Benskin, J.P. Development, characterization and comparisons of targeted and non-targeted metabolomics methods. PLoS One 2018, 13, e0207082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, A.; Creek, D.J. Using the IDEOM Workflow for LCMS-Based Metabolomics Studies of Drug Mechanisms. Methods Mol Biol 2020, 2104, 419–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creek, D.J.; Jankevics, A.; Burgess, K.E.; Breitling, R.; Barrett, M.P. IDEOM: An Excel interface for analysis of LC-MS-based metabolomics data. Bioinformatics 2012, 28, 1048–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creek, D.J.; Jankevics, A.; Burgess, K.E.; Breitling, R.; Barrett, M.P. IDEOM: an Excel interface for analysis of LC-MS-based metabolomics data. Bioinformatics 2012, 28, 1048–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pluskal, T.; Castillo, S.; Villar-Briones, A.; Oresic, M. MZmine 2: modular framework for processing, visualizing, and analyzing mass spectrometry-based molecular profile data. BMC Bioinformatics 2010, 11, 395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lommen, A. MetAlign: interface-driven, versatile metabolomics tool for hyphenated full-scan mass spectrometry data preprocessing. Anal Chem 2009, 81, 3079–3086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsugawa, H.; Cajka, T.; Kind, T.; Ma, Y.; Higgins, B.; Ikeda, K.; Kanazawa, M.; VanderGheynst, J.; Fiehn, O.; Arita, M. MS-DIAL: data-independent MS/MS deconvolution for comprehensive metabolome analysis. Nat Methods 2015, 12, 523–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers, O.D.; Sumner, S.J.; Li, S.; Barnes, S.; Du, X. Detailed Investigation and Comparison of the XCMS and MZmine 2 Chromatogram Construction and Chromatographic Peak Detection Methods for Preprocessing Mass Spectrometry Metabolomics Data. Anal Chem 2017, 89, 8689–8695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahieu, N.G.; Patti, G.J. Systems-Level Annotation of a Metabolomics Data Set Reduces 25 000 Features to Fewer than 1000 Unique Metabolites. Anal Chem 2017, 89, 10397–10406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pirttilä, K.; Balgoma, D.; Rainer, J.; Pettersson, C.; Hedeland, M.; Brunius, C. Comprehensive Peak Characterization (CPC) in Untargeted LC-MS Analysis. Metabolites 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chetnik, K.; Petrick, L.; Pandey, G. MetaClean: a machine learning-based classifier for reduced false positive peak detection in untargeted LC-MS metabolomics data. Metabolomics 2020, 16, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gloaguen, Y.; Kirwan, J.A.; Beule, D. Deep Learning-Assisted Peak Curation for Large-Scale LC-MS Metabolomics. Anal Chem 2022, 94, 4930–4937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jirayupat, C.; Nagashima, K.; Hosomi, T.; Takahashi, T.; Tanaka, W.; Samransuksamer, B.; Zhang, G.; Liu, J.; Kanai, M.; Yanagida, T. Image Processing and Machine Learning for Automated Identification of Chemo-/Biomarkers in Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry. Anal Chem 2021, 93, 14708–14715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dunn, W.B.; Broadhurst, D.I.; Atherton, H.J.; Goodacre, R.; Griffin, J.L. Systems level studies of mammalian metabolomes: the roles of mass spectrometry and nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Chem Soc Rev 2011, 40, 387–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wishart, D.S.; Tzur, D.; Knox, C.; Eisner, R.; Guo, A.C.; Young, N.; Cheng, D.; Jewell, K.; Arndt, D.; Sawhney, S.; et al. HMDB: the Human Metabolome Database. Nucleic Acids Res 2007, 35, D521–D526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horai, H.; Arita, M.; Kanaya, S.; Nihei, Y.; Ikeda, T.; Suwa, K.; Ojima, Y.; Tanaka, K.; Tanaka, S.; Aoshima, K.; et al. MassBank: a public repository for sharing mass spectral data for life sciences. J Mass Spectrom 2010, 45, 703–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, J.; Guijas, C.; Benton, H.P.; Warth, B.; Siuzdak, G. METLIN MS(2) molecular standards database: a broad chemical and biological resource. Nat Methods 2020, 17, 953–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aron, A.T.; Gentry, E.C.; McPhail, K.L.; Nothias, L.F.; Nothias-Esposito, M.; Bouslimani, A.; Petras, D.; Gauglitz, J.M.; Sikora, N.; Vargas, F.; et al. Reproducible molecular networking of untargeted mass spectrometry data using GNPS. Nat Protoc 2020, 15, 1954–1991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karp, P.D.; Riley, M.; Paley, S.M.; Pellegrini-Toole, A. The MetaCyc Database. Nucleic Acids Res 2002, 30, 59–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misra, B.B. New software tools, databases, and resources in metabolomics: updates from 2020. Metabolomics 2021, 17, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wishart, D.S.; Jewison, T.; Guo, A.C.; Wilson, M.; Knox, C.; Liu, Y.; Djoumbou, Y.; Mandal, R.; Aziat, F.; Dong, E.; et al. HMDB 3.0--The human metabolome database in 2013. Nucleic Acids Res 2013, 41, D801–D807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, C.A.O.M., G. Want, E.J.; Want, E.J.; Qin, C.; Trauger, S.A.; Brandon, T.R.; Custodio, D.E.; Abagyan, R.; Siuzdak, G. METLIN: a metabolite mass spectral database. Ther Drug Monit 2005, 27, 747–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, J.; Guijas, C.; Benton, H.P.; Warth, B.; Siuzdak, G. METLIN MS2 molecular standards database: A broad chemical and biological resource. Nat Methods 2020, 17, 953–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marco-Ramell, A.; Palau-Rodriguez, M.; Alay, A.; Tulipani, S.; Urpi-Sarda, M.; Sanchez-Pla, A.; Andres-Lacueva, C. Evaluation and comparison of bioinformatic tools for the enrichment analysis of metabolomics data. BMC Bioinformatics 2018, 19, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanehisa, M.; Goto, S. KEGG: Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes. Nucleic Acids Res 2000, 28, 27–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altman, T.; Travers, M.; Kothari, A.; Caspi, R.; Karp, P.D. A systematic comparison of the MetaCyc and KEGG pathway databases. BMC Bioinformatics.

- Yanshole, V.V.; Melnikov, A.D.; Yanshole, L.V.; Zelentsova, E.A.; Snytnikova, O.A.; Osik, N.A.; Fomenko, M.V.; Savina, E.D.; Kalinina, A.V.; Sharshov, K.A.; et al. Animal Metabolite Database: Metabolite Concentrations in Animal Tissues and Convenient Comparison of Quantitative Metabolomic Data. Metabolites 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldansaz, S.A.; Guo, A.C.; Sajed, T.; Steele, M.A.; Plastow, G.S.; Wishart, D.S. Livestock metabolomics and the livestock metabolome: A systematic review. PLOS ONE 2017, 12, e0177675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fiehn, O.; Robertson, D.; Griffin, J.; van der Werf, M.; Nikolau, B.; Morrison, N.; Sumner, L.W.; Goodacre, R.; Hardy, N.W.; Taylor, C.; et al. The metabolomics standards initiative (MSI). Metabolomics 2007, 3, 175–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumner, L.W.; Amberg, A.; Barrett, D.; Beale, M.H.; Beger, R.; Daykin, C.A.; Fan, T.W.; Fiehn, O.; Goodacre, R.; Griffin, J.L.; et al. Proposed minimum reporting standards for chemical analysis Chemical Analysis Working Group (CAWG) Metabolomics Standards Initiative (MSI). Metabolomics 2007, 3, 211–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salek, R.M.; Steinbeck, C.; Viant, M.R.; Goodacre, R.; Dunn, W.B. The role of reporting standards for metabolite annotation and identification in metabolomic studies. Gigascience, :13.

- Schymanski, E.L.; Jeon, J.; Gulde, R.; Fenner, K.; Ruff, M.; Singer, H.P.; Hollender, J. Identifying small molecules via high resolution mass spectrometry: Communicating confidence. Environ Sci Technol 2014, 48, 2097–2098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spicer, R.; Salek, R.M.; Moreno, P.; Canueto, D.; Steinbeck, C. Navigating freely-available software tools for metabolomics analysis. Metabolomics 2017, 13, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clasquin, M.F.; Melamud, E.; Rabinowitz, J.D. LC-MS data processing with MAVEN: a metabolomic analysis and visualization engine. Curr Protoc Bioinformatics, :11.

- Pluskal, T.; Castillo, S.; Villar-Briones, A.; Orešič, M. MZmine 2: modular framework for processing, visualizing, and analyzing mass spectrometry-based molecular profile data. BMC Bioinformatics.

- Kessler, N.; Neuweger, H.; Bonte, A.; Langenkämper, G.; Niehaus, K.; Nattkemper, T.W.; Goesmann, A. MeltDB 2.0-advances of the metabolomics software system. Bioinformatics 2013, 29, 2452–2459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armitage, E.G.; Godzien, J.; Alonso-Herranz, V.; López-Gonzálvez, Á.; Barbas, C. Missing value imputation strategies for metabolomics data. Electrophoresis 2015, 36, 3050–3060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xia, J.; Sinelnikov, I.V.; Han, B.; Wishart, D.S. MetaboAnalyst 3.0—making metabolomics more meaningful. Nucleic Acids Res 2015, 43, W251–W257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Helminth species and family | Life cycle stage | Host | Sample analyzed | Study approach | Metabolite types | MSI identification level | Analytical instruments/platforms used | Databases/software used | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ancylostoma caninum (Ancylostomatidae) | Adult | Dog | SE, ESP | Targeted | Polar metabolites & lipids | Level 1 | GC-MS & LC-MS |

Database: MAML Software: Agilent MassHunter (v.7); MetaboAnalyst (v.3.0) |

[56] |

| Ascaris suum (Ascarididae) | L3, L4, adult | Swine | SE | Untargeted | Lipids | Level 2 | UHPLC-MS/MS | Database: LipidSearch (v.4.2.23) | [57] |

| Ascaris lumbricoides (Ascarididae) | Adult | Human and swine | ESP | Targeted | Lipids | Level 1 | GLC | Lipids were identified by matching retention times with standards | [58] |

| Eggs, L1, L3 | SE | Fingerprint | Biomarkers (pheromones/steroidal prohormones) | Level 2 | HRMS |

Database: Lipid MAPS; HMDB (v 3.6); METLIN Software: MetaboAnalyst (v.3.0) |

[59] | ||

| Brugia malayi (Onchocercidae) | Adult | Dogs and wild felids | Cuticle | Targeted | Lipids | Level 1 | TLC & GC | Lipids were identified by matching retention times with standards | [60] |

| Dictyocaulus viviparus (Dictyocaulidae) | Eggs, L1-L3, preadult, adult | Cattle | SE | Targeted | Lipids | Level 1 | GC | Lipids were identified matching retention times with standards Software: Chem Station B.01.03. |

[61] |

| Dipylidium caninum (Dipylidiidae) | Adult | Dog | ESP | Targeted | Polar metabolites & lipids | Level 1 | GC-MS |

Database: MHL; KEGG; NIST library; MAML Software: MetaboAnalyst (v.4.0) |

[62] |

| Echinococcus multilocularis (Taeniidae) | Larval metacestode | Fox | CS | Untargeted | Polar metabolites | Level 1 | 1H NMR |

Database: HMDB Software: Chenomx NMR Suit (v 8.2); STOCSY |

[63] |

| Haemonchus contortus (Trichostrongylidae) | Eggs, L3, xL3, L4, adult | Goats and sheep | SE | Untargeted | Lipids | Level 2 | UHPLC-ESI(+)-MS/MS-Orbitrap |

Database: LipidSearch (v.4.1.30 SPI) Software: R package |

[54] |

|

Hymenolepis diminuta (Hymenolepididae) |

Infective stage | Rodents (rats) | SE | Targeted | Lipids | Level 1 | TLC, CC, & GLC | NA | [39] |

| Necator americanus (Ancylostomatidae) | L3 | Human | SE, ESP | Untargeted | Polar metabolites | Level 1 | Q-Exactive Orbitrap & MS/HPLC |

Database: KEGG; MetaCyc; CTS; Lipid MAPS; PubChem; HMDB Software: IDEOM; MetaboAnalyst (v.3.0) |

[64] |

| Lipids | Level 2 | ||||||||

| Nippostrongylus brasiliensis (Heligmonellidae) | Adult | Rodents (rats) | ESP | Targeted | Polar metabolites & lipids | Level 1 | 1H NMR |

Database: GenBank; NCBI GEO Software: STAR; Chenomx NMR Suite (v.5.1) |

[40] |

| L3 | SE, ESP | Untargeted | Polar metabolites | Level 1 | Q-Exactive Orbitrap & MS/HPLC |

Database: KEGG, MetaCyc; Lipid MAPS; PubChem CID; HMDB; CTS Software: IDEOM; MetaboAnalyst (v.3.0) |

[33,34] |

||

| Lipids | Level 2 | ||||||||

| Adult | ESP | Targeted | Polar metabolites & lipids | Level 1 | GC-MS |

Database: MAML; MHL; KEGG Software: Agilent MassHunter (v.7) |

|||

| Adult | ESP | Untargeted | Polar metabolites | Level 1 | UHPLC-MS |

Database: HMDB; PubChem CID Software: XCMS; MetaboAnalyst; R package |

[65] | ||

| Intestinal content | |||||||||

| Oesophagostomum dentatum; O. quadrispinulatum (Strongylidae) | L3, L4, adult | Common livestock (goats, sheep, and swine) | SE | Untargeted | Lipids | Level 1 | GC |

Lipids identification: Matching retention times with standards Software: MIDI system package (v. 3.30) |

[66] |

| Schistosoma mansoni (Schistosomatidae) | Adult | Human | SE | Targeted | Lipids | Level 1 | MALDI MSI (+) |

Database: METLIN; Lipid MAPS Software: Uscrambler (v.9.7); Mass Frontier (v.6.0) |

[43] |

| Eggs, miracidia, cercariae | SE | Untargeted | Lipids | Level 2 | ESI(+)-HRMS |

Database: Lipid MAPS; METLIN Software: Unscrambler (v.9.7) |

[31] | ||

| Adult | SE | Untargeted | Lipids | Level 2 | MALDI-MSI(+) |

Database: Lipid MAPS; METLIN Software: Unscrambler (v.9.7) |

[44] | ||

| Adult | TS | Targeted | Lipids | Level 2 | HPLC-MS (Sciex 4000QTRAP) | Lipids were identified by universal HPLC-MS method Software: Markerview (v.1.0) |

[67] | ||

| Eggs, cercariae, adult | SE, ESP | Targeted | Lipids | Level 2 | LC-MS/MS (QTrap) (ESI-) |

Software: LipidBlast; FiehnO lipid database in MS-DIAL (v2.74) Software: R package |

[52] | ||

| Targeted | Lipids | GC-MS | |||||||

| Targeted | Lipids | LC-MS/MS (QToF) (ESI+) | |||||||

| Adult | SE | Untargeted | Lipids | Level 2 | AP-SMALDI MSI |

Database: SwissLipids; LipidMatch (v2.0.2) Software: Lipid Data Analyzer (v2.6.2) |

[45] | ||

| Strongyloides ratti (Strongylidae) | L1, L3, free-living | Rodent (rats) | SE | Targeted | Lipids | Level 1 | GC-MS | Lipids were identified by matching retention times with standards. | [68] |

| Trichuris muris (Trichuridae) | Embryonated eggs | Rodents (mice) | SE | Untargeted | Polar metabolites | Level 1 | Q-Exactive Orbitrap & MS/HPLC |

Database: KEGG; MetaCyc; Lipid MAPS; PubChem CID; HMDB; CTS Software: IDEOM; MetaboAnalyst (v.3.0) |

[33] |

| Lipids | Level 2 | ||||||||

| Adult | ESP | Targeted | Polar metabolites & lipids | Level 1 | GC-MS |

Database: MAML; MHL; KEGG Software: Agilent MassHunter (v.7); MetaboAnalyst (v.3.0) |

[21] | ||

| Trichinella papuae (Tricinellidae) | L1 (muscle-stage) | Swine | SE | Untargeted | Lipids | Level 2 | ESI(+/-) UPLC-MS/MS |

Database: Lipid MAPS; LipidBlast Software: Progenesis QI (v.2.1; QuickGO |

[53] |

| Toxocara canis (Toxocaridae) | Adult | Dog | ESP | Targeted | Polar metabolites & lipids | Level 1 | GC-MS & LC-MS |

Database: Agilent MassHunter (v.7); MAML Software: MetaboAnalyst (v.3.0) |

[55] |

| Adult | SE | Untargeted | Polar metabolites & lipids | Level 1 | 1H NMR | NA | [69] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).