Submitted:

05 September 2024

Posted:

06 September 2024

You are already at the latest version

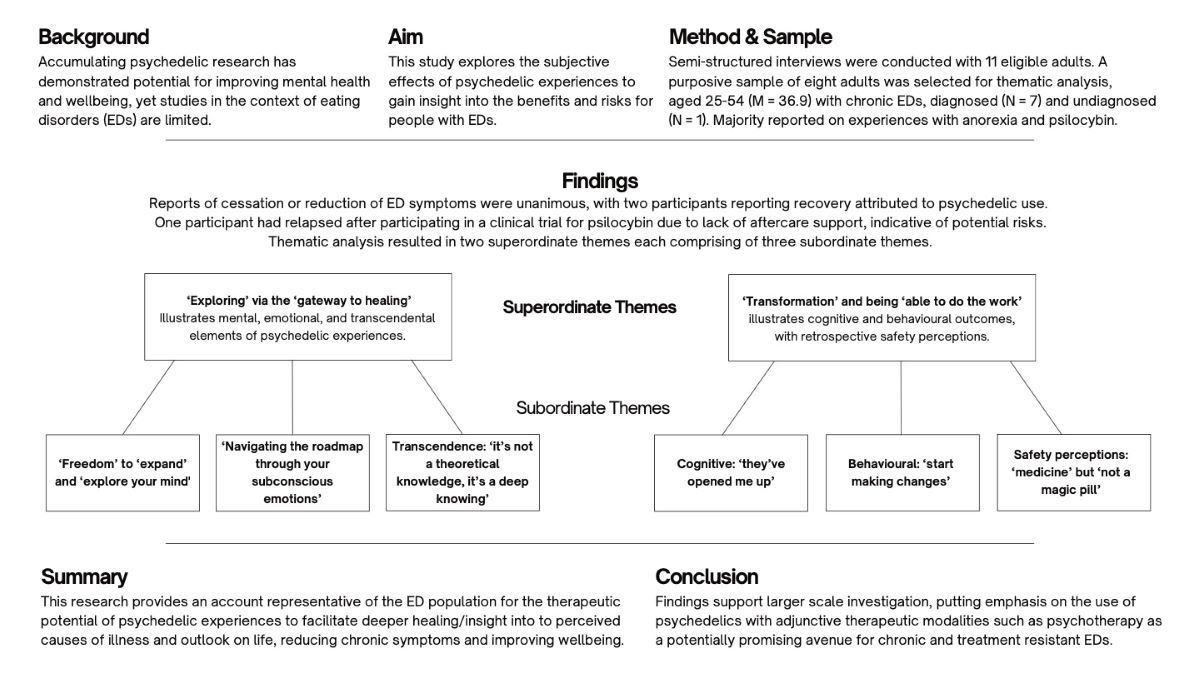

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Eating Disorders

2.2. Theoretical Underpinning

2.3. Treatments

2.4. Psychedelics

2.5. Theoretical Underpinning

2.6. Risks of Harm/Adverse Effects

3. Psychedelics and Eating Disorders

4. Aims

5. Method

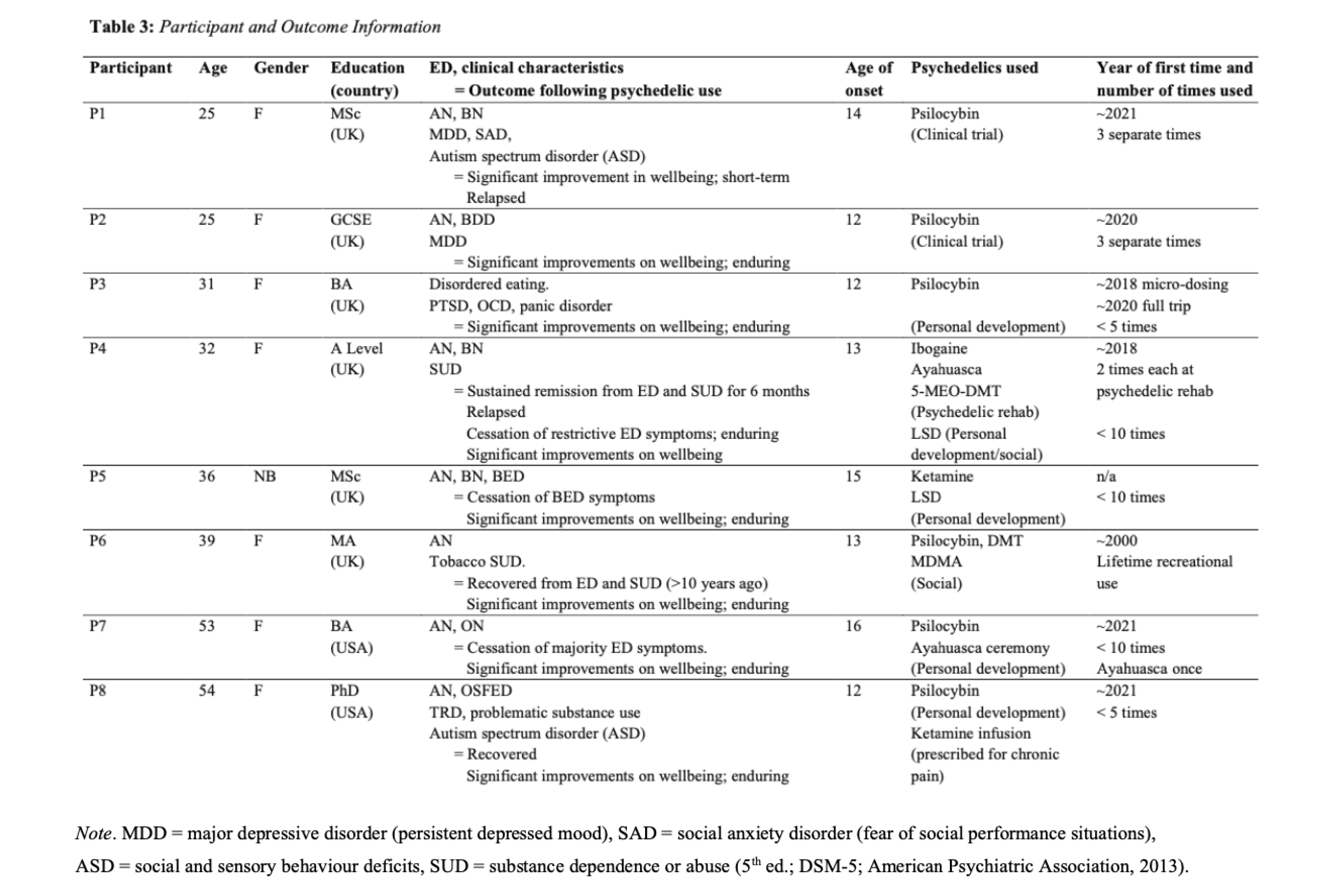

5.1. Sampling: Recruitment and Participants

5.2. Data Collection: Semi-Structured Interview and Procedure

5.3. Design: Qualitative Analysis

5.4. Ethics Commentary

5.5. Results and Discussion

5.6. Superordinate Theme 1

Exploring via ‘the Gateway to Healing’

“Until you’ve actually tried them, you don’t really understand like, how life changing it can be and how it can free your mind to kind of see other possibilities and other pathways that you could choose to reinforce if you wanted to. So, like, once I had my first couple of psychedelic experiences, I got excited about what I might be able to do with it.” (P5)

“...my brain was a lot more open and available to think, and, there was more possibility and hope” (P1)

“...these are concepts I’ve been working on my whole life, but I’ve not been able to put into practice... So, I think that when I took the psilocybin, I was able to put into practice all the work that I’ve been doing. I realised that it wasn’t for nothing, it wasn’t lost, and that I was working, I was fighting like hell. And um, psilocybin opened the door.” (P8)

5.7. Subordinate Theme 1. ‘Freedom’ to ‘Expand’ and ‘Explore Your Mind’

“They help me realise why I’m having these urges, why I’m feeling that way. But also showed me that the eating disorder is part of something bigger, something deeper, which I need to go back and look at.” (P3)

“... I could focus my mind, which was brand new to me. I could choose, if I didn't want to think about something, I could just let it go. It, it was brilliant... That’s what I noticed first. That I could observe my thoughts, and see what was going on in my mind...

I could not before, I could know what I was thinking, but wasn’t able to... Place myself, like see myself as the observer, other than the person wrapped up in the thoughts. And I thought, wow, so this is how I’m thinking... And most importantly without judgement, my judgements, criticisms, self-criticisms... Just turned into real curiosity and wonder... And admiration for how truly, sneaky my mind is.” (P8)

“...I noticed with the muscle clenching, when I relaxed, and noticed it was clenching, I realised it was me clenching it? So, I could relax... As soon as I realised that, and I relaxed, that sort of went? Almost made me realise a lot of the pressure, I think, kind of indicated to me a lot of the pressure is my own doing... And it’s my own tension, it’s like... Yeah, like just, under my control? If that makes sense. Like I’m doing all the pressure, if I relax into things, and just, loosen up a bit, things get easier...”

“It was weird. And it felt bad, like awkward and silly, but it got easier and... They were doing it as well, and it felt kind of alright by the end... Just like, trying things and... Tryna get out of this... Control... and everything.” (P1)

“I really got to explore something that was usually a very scary, threatening, complicated... Stressful thing in my life, in a totally new way and developing my relationship to it” (P5)

5.8. Subordinate Theme 2. ‘Navigating the Roadmap through Your Subconscious Emotion’

“I was able to heal, a lot of the childhood trauma that led to the eating disorder, and... Understand, where it originated ... I just, was able to go back to being a child... Um, being traumatised by my mum, and, able to see her as a little girl, being traumatised by her mum. So, I was able to understand that this is generational trauma... And, I was able to just forgive, so much of that, and release it. And, I was angry, I was angry, a lot. And, and I took that anger out on myself, by, just punishing myself. But I don’t have any anger about that, anymore.” (P7)

“You know, making poor choices because I, I didn’t have any self-confidence, I had no self-esteem, I had no self-worth. And, it helped me to... Find, those parts of me that are there, and embrace them. And, love myself, more fully” (P7)

“Another thing was, if you don’t mind me sharing, when I was younger, I had an abortion. Um, and I was still holding on to the pain of that, that I didn’t, sorry *crying* I didn’t know that I was holding on to? Uh, and I forgave myself, during that trip. Which was very beautiful... I think, it just brings about more love. And therefore, you start to see the fears and illusions etc... To be honest, to summarise, I think it brings you closer to yourself... It helps you, love yourself, which then helps you love everyone else around you” (P3)

“... wave after wave, as I fell into the grief, and I'm crying, I also accessed this profound love. And I realise that it's like the same thing. I'm grieving because I love, and then I felt elated and joy, gratitude, incredible gratitude. And just the gratitude in the surprise, wonder, ah, that holy cow, this is what I've been avoiding my whole life... Grieving.

And grief, surrender, letting go of what I thought was, true? It’s really a jumping off point, it’s really um, terrifying, and I was afraid of the pain of it, and I didn’t want to let go. I guess. It felt like I was letting go of the person... But. I found that when I let go of things... I was present. And my presence enabled me to... Well, my presence enabled everything.” (P8)

5.9. Subordinate Theme 3. Transcendence: ‘it’s Not a Theoretical Knowledge, It’s a Deep Knowing’

“... they’re also really, like fun, and... Put you back in touch with what’s really, really beautiful about the world and people, and can be an incredibly moving, kind of connecting thing” (P5)

“...when you know that, all your, like your problems kind of pale into insignificance... A little bit, or they get put into perspective... A bit more... Like let go. Chill out, I’m self-sufficient, I’ll be fine whatever happens. I have so much life left, so make the most of it, don’t die early because of bulimia. I’m human, I don’t need perfection.” (P4)

“I think, its... To do with, joy, and... There’s so much, I think, it’s to do with the feeling of um... Life is so big, and I am so small, like, the things that I think really matter, don’t matter? Like, what I look like in a pair of jeans or like, if I’ve eaten like x, y, and z today... Like those things really don’t fucking matter in comparison to like the... Largeness of the universe, and the part that I have to play in it, and what matters is... Relationship, and connection, and... Making meaning of the things that happen to us... And I felt as though... That place, will always be there for me, but I still have work to do here... and that’s okay?” (P2)

“I think it was me, being able to understand that my experience of men has been, the ego aspect of men, and, this just showed me that you know, they have a higher self too, this isn’t who they really are? Um, and that they are shaped by a society that diminishes women, and... I don’t know, just helped me to... Forgive that. You know, to forgive the abuse that I’ve suffered, because ultimately, it’s all led me to this... This healing journey...

And, there’s just not, there’s just not a reality that I want to live in where I can’t forgive people. I don’t want to hold on to... Anger, and resentment, and, I think by, yes, castrating them and giving their heart back, was... A way for me to... Acknowledge that they are better than the person that they are in this lifetime.” (P7)

5.10. Superordinate Theme 2

“...working with the medicine has really helped me a lot to release that (trauma), and I honestly feel better than I have... Since, before I can remember... Physically, mentally, emotionally, just all of it.”

“You still have to... Integrate those lessons, and... Catch yourself when you’re falling back into old negative thinking patterns, but it has certainly been a catalyst... To a deeper kind of heeling than I have ever experienced before, through any kinds of conventional methods” (P7)

“...My life has meaning. I connected with meaning that there was meaning even in my suffering itself, I think this was probably the most significant factor... I saw that I really needed to change. And what I didn't realise was, how much I would change. I'm not that person anymore. I see a thread to that person, but I cannot. I can't go back. Like I'm not worried that my depression or my eating disorder will remerge because I feel like I can't even find those pathways.” (P8)

5.11. Subordinate Theme 1. Cognitive: ‘They’ve Opened Me Up’

“They give me hope, which when... I’ve been struggling with addictions and bulimia for, so long, like hope, is... So cool to have, and is so important. Because, before I tried psychedelics, I was just hopeless, like I had no hope, I wanted to die, I really didn’t give a shit. And now, like, they’ve opened my life up, they’ve opened me up spiritually, which is incredibly important. They give me hope that one day recovery, like I know, that one day I will recover. And, they’ve also, given me a lot of really cool friends. Which is great. So, yeah, I’m very, very grateful.” (P4)

“I think for the first time, everything else in my brain got shut off, and I got to just actually just be there and feel it, and I think that sensation is sort of what motivates me in that, I sort of know what it feels like... Before, because I’d never felt like that, it was like not plausible, it was incomprehensible... And because I was allowed to have a taste of it, I now feel like I have something to work towards, whereas before it felt like impossible.” (P2)

“Seeing that I have changed over time is really encouraging and encourages you to carry on trying because you know that like, even if progress is going to be slow, it does happen if you work at it, because when you've never experienced that kind of change before then it feels impossible. Because it's so relentless sometimes the thoughts so, the urges....” (P5)

“Acid kind of..., sort of gave me permission to just like, be at home in my body, appreciate like, looking after myself and feeding myself and, it's hard to put into words, but you’re really kind of confronted by what you are... Which is a creature, like this weird, complicated, miraculous thing that that needs to absorb stuff from other stuff to exist” (P5)

“My thoughts are not obsessive. And if they do get obsessive, I notice it. And I’m like oh... that’s interesting... wonderfully interesting. And then I move on... It’s... The ability to notice, it’s a DBT skill, notice, describe and participate... I would practice the skills, but they just didn’t click in a way that seemed like they should be... And I wasn’t present, I was avoiding. Yeah, I have to be present to experience, you have to be present to observe, and to participate... And I didn’t know how to bring myself present, I did everything I could think of.” (P8)

5.12. Subordinate Theme 2. Behavioural: ‘Start Making Changes’

“... not just having the experience with psilocybin, but putting it into practice, in their lives. Start making changes, do a lot of writing, figure out what you need to transform and um the psilocybin will help the person to do that, and to be just completely honest. With themselves. I know that when it becomes chronic it’s learned, and you can unlearn it” (P8)

“After that journey, I just noticed that... Some of my compulsive um, symptoms, had dramatically reduced, as far as just obsessing about my weight...

...there were times when I would weigh myself 20, times a day *laughs* and that just seemed to... Kind of, evaporate. The need, to do that just, really was greatly diminished... So, I continued, using psilocybin mushrooms from then, about 7 times, and I had just... Been able to get to the point where I don’t weigh myself at all... Anymore.” (P7)

“I started getting involved with like, I went to Breaking Convention, and a couple of psychedelic meetups, and it was just like, eye opening, like it was a whole new world... I started volunteering for Psycare, and felt like I had found my tribe. Like, for the first time, in a long time. And my symptoms were just fine, I was completely normal... It was beyond, like words. I couldn’t even, like I’d never had that before. I was just absolutely okay?” (P4)

“... normally my body will feel quite stressed, and I’m rushing around, finding it quite hard to stay grounded, and... Connected, in the moment... But now, I just don’t put much drama into, like oh no, it has to be perfect, or has to be at a certain time, like I’m a lot more flexible with my food.”

“...after having this experience with my eating disorder, and being sort of more withdrawn from my creativity and my creative voice, it really connected me to that voice. And, profoundly changed um... The direction of my artwork? For quite some time, I didn’t really have the words, you know, to sort of, to really go into that process deeply, or. It didn’t flow as naturally, let’s put it that way. And it just seemed like um... Yeah, the dots were... Connected... I guess when I was battling with it, my perception was sort of more, um, introverted I guess, and then sort of expanded with the use, with the help of psychedelics” (P6)

5.13. Subordinate Theme 3. Safety Perceptions: ‘Medicine’ but ‘Not a Magic Pill’

“…they mean… Healing. And they mean, medicine, and they mean connection, and they mean… Hope, and for me they feel like… A gift, that’s given to us? By like, the earth, and… I think, there’s danger of, putting all our hopes and dreams in the basket of like, if I eat this mushroom then my life is going to be like sorted and I’m gonna have no problems ever again… I think that is not what they’re there for, and I think they’re there to allow us to see some, the possibility. See possibility where we couldn’t see it before. Um, so I’d try not to put them on a pedestal, but um, I think they’re fucking cool.” (P2)

“The caution would be, make sure you do your research, and be with people that, you know you can trust… Um, and if somebody has severe mental or psychological problems, they need to work with a therapist or a doctor to make sure they’re gonna be safe doing that...” (P7)

“If I’m going to do psychedelics on my own at home, I’ll still get lessons, but it will be more spiritual lessons, or reflective lessons around my life, but my eating disorder is still… The symptoms will still be there. You know, even though I’ll have more knowledge… There symptoms will still be there. Whereas when I go to psychedelic rehab, the symptoms are reduced, and I get more knowledge. Just cause everything’s more intense in there” (P4)

“…it didn’t feel like I was working on, it felt like I should’ve been working on problems and thinking… Like, new ways to behave and… Putting things into action, cause I felt really… Yeah just open to things and more… Like my brain was a lot more active and hopeful and stuff. But I didn’t know what to do with that, and then it sort of trailed off… and… It just feels, I feel almost worse now… Cause I feel really disappointed.” (P1)

“So, if people take a psychedelic and think, oh I’m gonna be cured, then they’re in for a very rude awakening, because that’s not the way it works. You have to be determined to commitment. Determined to work hard.” (P3)

6. Summary

7. Limitations

8. Conclusions

9. Reflexivity Statement

References

- Abramowitz, J.S.; Reuman, L. Obsessive compulsive disorder. Encyclopedia of personality and individual differences 2020, 3304–3306. [Google Scholar]

- Aday, J.S.; Mitzkovitz, C.M.; Bloesch, E.K.; Davoli, C.C.; Davis, A.K. Long term effects of psychedelic drugs: A systematic review. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews 2020, 113, 179–189. [Google Scholar]

- Ahn, J.; Lee, J.H.; Jung, Y.C. Predictors of suicide attempts in individuals with eating disorders. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior 2019, 49, 789–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alonso, J.F.; Romero, S.; Mañanas M, À.; Riba, J. Serotonergic psychedelics temporarily modify information transfer in humans. International Journal of Neuropsychopharmacology 2015, 18, pyv039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Psychiatric Association (2013). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th edn. American Psychiatric Association, Washington.

- American Psychiatric Association (2013). Highlights of Changes from DSM-IV-TR to DSM 5. In Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association.

- Anderson, C.B.; Carter, F.A.; McIntosh, V.V.; Joyce, P.R.; Bulik, C.M. Self harm and suicide attempts in individuals with bulimia nervosa. Eating Disorders 2002, 10, 227–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andersen, K.A.; Carhart-Harris, R.; Nutt, D.J.; Erritzoe, D. Therapeutic effects of classic serotonergic psychedelics: A systematic review of modern-era clinical studies. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 2021, 143, 101–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, R. Intuitive inquiry: Inviting transformation and breakthrough insights in qualitative research. Qualitative Psychology 2019, 6, 312–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arcelus, J.; Mitchell, A.J.; Wales, J.; Nielsen, S. Mortality rates in patients with anorexia nervosa and other eating disorders: a meta-analysis of 36 studies. Archives of general psychiatry 2011, 68, 724–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artin, H.; Zisook, S.; Ramanathan, D. How do serotonergic psychedelics treat depression: The potential role of neuroplasticity. World Journal of Psychiatry 2021, 11, 201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baer, R.A.; Smith, G.T.; Hopkins, J.; Krietemeyer, J.; Toney, L. Using self-report assessment methods to explore facets of mindfulness. Assessment 2006, 13, 27–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beating Eating Disorders (BEAT) (2019). Lives at risk: The state of NHS adult community eating disorder services in England. Beating Eating Disorders (BEAT) & Maudsley Charity. https://beat.contentfiles.net/media/documents/lives-at-risk.pdf.

- Ben-Porath, D.; Duthu, F.; Luo, T.; Gonidakis, F.; Compte, E.J.; Wisniewski, L. Dialectical behavioral therapy: an update and review of the existing treatment models adapted for adults with eating disorders. Eating Disorders 2020, 28, 101–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berkman, N.D.; Lohr, K.N.; Bulik, C.M. Outcomes of eating disorders: a systematic review of the literature. international Journal of Eating disorders 2007, 40, 293–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bingham, A.J.; Witkowsky, P. (2022). Deductive and inductive approaches to qualitative data analysis. In C. Vanover, P. Mihas, & J. Saldaña (Eds.), Analyzing and interpreting qualitative data: After the interview (pp. 133-146). SAGE Publications.

- Bjornsson, A.S.; Didie, E.R.; Phillips, K.A. Body dysmorphic disorder. Dialogues in clinical neuroscience. 2022, 12, 221–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bodell, L.P.; Joiner, T.E.; Keel, P.K. Comorbidity-independent risk for suicidality increases with bulimia nervosa but not with anorexia nervosa. Journal of psychiatric research 2013, 47, 617–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bratland-Sanda, S.; Sundgot-Borgen, J. Eating disorders in athletes: overview of prevalence, risk factors and recommendations for prevention and treatment. European journal of sport science 2013, 13, 499–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative research in psychology 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Conceptual and design thinking for thematic analysis. Qualitative Psychology 2022, 9, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breeksema, J.J.; Niemeijer, A.R.; Krediet, E.; Vermetten, E.; Schoevers, R.A. Psychedelic treatments for psychiatric disorders: a systematic review and thematic synthesis of patient experiences in qualitative studies. CNS drugs 2020, 34, 925–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brewerton, T.D. Eating disorders, trauma, and comorbidity: Focus on PTSD. Eating disorders 2007, 15, 285–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brewerton, T.D.; Wang, J.B.; Lafrance, A.; Pamplin, C.; Mithoefer, M.; Yazar-Klosinki, B.; Doblin, R. MDMA-assisted therapy significantly reduces eating disorder symptoms in a randomized placebo-controlled trial of adults with severe PTSD. Journal of Psychiatric Research 2022, 149, 128–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, T.A.; Wisniewski, L.; Anderson, L.K. Dialectical behavior therapy for eating disorders: State of the research and new directions. Eating Disorders 2020, 28, 97–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Callon, C.; Williams, M.; Lafrance, A. “Meeting the Medicine Halfway”: Ayahuasca Ceremony Leaders’ Perspectives on Preparation and Integration Practices for Participants. Journal of Humanistic Psychology 2021, 00221678211043300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, K.; Peebles, R. Eating disorders in children and adolescents: state of the art review. Pediatrics 2014, 134, 582–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carhart-Harris, R.L.; Bolstridge, M.; Rucker, J.; et al. (2016) Psilocybin with psychological support for treatment-resistant depression: an open-label feasibility study. Lancet Psychiatry. 2016, 3, 619–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carhart-Harris, R.L.; Bolstridge, M.; Day CM, J.; Rucker, J.; Watts, R.; Erritzoe, D.E. , .. & Nutt, D.J. Psilocybin with psychological support for treatment-resistant depression: six-month follow-up. Psychopharmacology 2018, 235, 399–408. [Google Scholar]

- Carhart-Harris, R.L.; Erritzoe, D.; Haijen EC, H.M.; Kaelen, M.; Watts, R. Psychedelics and connectedness. Psychopharmacology 2018, 235, 547–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carhart-Harris, R.L.; Erritzoe, D.; Williams, T.; et al. (2012) Neural correlates of the psychedelic state as determined by fMRI studies with psilocybin. Proc Natl Acad SciUSA. 2012, 109, 2138–2143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carhart-Harris, R.L.; Friston, K. REBUS and the anarchic brain: toward a unified model of the brain action of psychedelics. Pharmacological reviews 2019, 71, 316–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carhart-Harris, R.; Giribaldi, B.; Watts, R.; Baker-Jones, M.; Murphy-Beiner, A.; Murphy, R. ,... & Nutt, D.J. Trial of psilocybin versus escitalopram for depression. New England Journal of Medicine 2021, 384, 1402–1411. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Carhart-Harris, R.L.; Goodwin, G.M. The therapeutic potential of psychedelic drugs: past, present, and future. Neuropsychopharmacology 2017, 42, 2105–2113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carhart-Harris, R.L.; Leech, R.; Hellyer, P.J.; Shanahan, M.; Feilding, A.; Tagliazucchi, E. ,... & Nutt, D. The entropic brain: a theory of conscious states informed by neuroimaging research with psychedelic drugs. Frontiers in human neuroscience 2014, 20. [Google Scholar]

- Carhart-Harris, R.L.; Nutt, D.J. (2017) Serotonin and brain function: a tale of two receptors. J Psychopharmacol. 2017, 31, 1091–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carhart-Harris, R.L.; Roseman, L.; Bolstridge, M.; Demetriou, L.; Pannekoek, J.N.; Wall, M.B. ,... & Nutt, D.J. Psilocybin for treatment-resistant depression: fMRI measured brain mechanisms. Scientific reports 2017, 7, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Cervinka, R.; Röderer, K.; Hefler, E. Are nature lovers happy? On various indicators of well-being and connectedness with nature. Journal of health psychology 2012, 17, 379–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cipriani, A.; Furukawa, T.A.; Salanti, G.; Chaimani, A.; Atkinson, L.Z.; Ogawa, Y. ,... & Geddes, J. R. Comparative efficacy and acceptability of 21 antidepressant drugs for the acute treatment of adults with major depressive disorder: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Focus 2018, 16, 420–429. [Google Scholar]

- Close, J.B.; Bornemann, J.; Piggin, M.; Jayacodi, S.; Luan, L.X.; Carhart-Harris, R. , & Spriggs, M. J. Co-design of guidance for Patient and Public Involvement in Psychedelic Research. Frontiers in Psychiatry 2021, 1696. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper, Z.; Allen, E.; Bailey-Straebler, S.; Basden, S.; Murphy, R.; O’Connor, M.E.; Fairburn, C.G. Predictors and moderators of response to enhanced cognitive behaviour therapy and interpersonal psychotherapy for the treatment of eating disorders. Behaviour Research and Therapy 2016, 84, 9–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuerva, K.; Spirou, D.; Cuerva, A.; Delaquis, C.; Raman, J. Perspectives and preliminary experiences of psychedelics for the treatment of eating disorders: A systematic scoping review. European Eating Disorders Review. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahlenburg, S.C.; Gleaves, D.H.; Hutchinson, A.D. Treatment outcome research of enhanced cognitive behaviour therapy for eating disorders: a systematic review with narrative and meta-analytic synthesis. Eating Disorders 2019, 27, 482–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, A.K.; Barrett, F.S.; Griffiths, R.R. Psychological flexibility mediates the relations between acute psychedelic effects and subjective decreases in depression and anxiety. Journal of contextual behavioral science 2020, 15, 39–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, L.E.; Attia, E. (2019) Recent advances in therapies for eating disorders. F1000Research. [CrossRef]

- Daws, R.E.; Timmermann, C.; Giribaldi, B.; Sexton, J.D.; Wall, M.B.; Erritzoe, D. ,... & Carhart-Harris, R. Increased global integration in the brain after psilocybin therapy for depression. Nature medicine 2022, 28, 844–851. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Dessain, A.; Bentley, J.; Treasure, J.; Schmidt, U.; Himmerich, H. Patients’ and Carers’ perspectives of psychopharmacological interventions targeting anorexia nervosa symptoms. Anorexia and Bulimia Nervosa 2019, 103. [Google Scholar]

- De Vos, C.M.; Mason, N.L.; Kuypers, K.P. Psychedelics and neuroplasticity: a systematic review unraveling the biological underpinnings of psychedelics. Frontiers in psychiatry 2021, 1575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Domínguez-Clavé, E.; Soler, J.; Elices, M.; Franquesa, A.; Álvarez, E.; Pascual, J.C. Ayahuasca may help to improve self-compassion and self-criticism capacities. Human Psychopharmacology: Clinical and Experimental 2022, 37, e2807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dos Santos, R.G.; Osorio, F.L.; Crippa JA, S.; Hallak, J.E. Classical hallucinogens and neuroimaging: A systematic review of human studies: Hallucinogens and neuroimaging. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews 2016, 71, 715–728. [Google Scholar]

- Drummond, E.; McCulloch, W.; Knudsen, G.M.; Barrett, F.S.; Doss, M.K.; Carhart-Harris, R.L. ,... & Fisher, P.M. Psychedelic resting-state neuroimaging: a review and perspective on balancing replication and novel analyses. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews 2022, 104689. [Google Scholar]

- Dunn, T.M.; Bratman, S. On orthorexia nervosa: A review of the literature and proposed diagnostic criteria. Eating Behaviors 2016, 21, 11–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyck, E.; Elcock, C. Reframing bummer trips: scientific and cultural explanations to adverse reactions to psychedelic drug use. The Social History of Alcohol and Drugs 2020, 34, 271–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eskander, N.; Limbana, T.; Khan, F. Psychiatric comorbidities and the risk of suicide in obsessive-compulsive and body dysmorphic disorder. Cureus 2020, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Espel, H.M.; Goldstein, S.P.; Manasse, S.M.; Juarascio, A.S. Experiential acceptance, motivation for recovery, and treatment outcome in eating disorders. Eating and Weight Disorders-Studies on Anorexia, Bulimia and Obesity 2016, 21, 205–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fairburn, C.G.; Cooper, Z.; Shafran, R. Cognitive behaviour therapy for eating disorders: A “transdiagnostic” theory and treatment. Behaviour research and therapy 2003, 41, 509–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fassino, S.; Pierò, A. , … & Tomba, E. Factors associated with dropout from treatment for eating disorders: a comprehensive literature review. BMC Psychiatry 2009, 9, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flanagan, T.W.; Nichols, C.D. Psychedelics as anti-inflammatory agents. International Review of Psychiatry 2018, 30, 363–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foldi, C.J.; Liknaitzky, P.; Williams, M.; Oldfield, B.J. Rethinking therapeutic strategies for anorexia nervosa: insights from psychedelic medicine and animal models. Frontiers in Neuroscience 2020, 14, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frank GK, W. Altered brain reward circuits in eating disorders: chicken or egg? Current Psychiatry Reports 2013, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank, G.K.; Shott, M.E.; DeGuzman, M.C. The Neurobiology of eating disorders. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America 2019, 28, 629–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frost, R.O.; DiBartolo, P.M. (2002). Perfectionism, anxiety, and obsessive-compulsive disorder. In G. L. Flett & P. L. Hewitt (Eds.), Perfectionism: Theory, research, and treatment (pp. 341–371). American Psychological Association. [CrossRef]

- Galmiche, M.; Déchelotte, P.; Lambert, G.; Tavolacci, M.P. Prevalence of eating disorders over the 2000–2018 period: a systematic literature review. The American journal of clinical nutrition 2019, 109, 1402–1413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galvão-Coelho, N.L.; Marx, W.; Gonzalez, M.; Sinclair, J.; de Manincor, M.; Perkins, D.; Sarris, J. Classic serotonergic psychedelics for mood and depressive symptoms: a meta-analysis of mood disorder patients and healthy participants. Psychopharmacology 2021, 238, 341–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, H.; Puramat, P.; Patel, P.; Gill, B.; Marks, C.A.; Rodrigues, N.B. ,... & McIntyre, R.S. The Effects of Psilocybin in Adults with Major Depressive Disorder and The General Population. Psychiatry Research 2022, 114577. [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths, R.R.; Hurwitz, E.S.; Davis, A.K.; Johnson, M.W.; Jesse, R. Survey of subjective" God encounter experiences": Comparisons among naturally occurring experiences and those occasioned by the classic psychedelics psilocybin, LSD, ayahuasca, or DMT. PloS one 2019, 14, e0214377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Griffiths, R.R.; Johnson, M.W.; Carducci, M.A.; Umbricht, A.; Richards, W.A.; Richards, B.D. ,... & Klinedinst, M.A. Psilocybin produces substantial and sustained decreases in depression and anxiety in patients with life-threatening cancer: A randomized double-blind trial. Journal of psychopharmacology 2016, 30, 1181–1197. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Griffiths, R.R.; Richards, W.A.; Johnson, M.W.; McCann, U.D.; Jesse, R. Mystical-type experiences occasioned by psilocybin mediate the attribution of personal meaning and spiritual significance 14 months later. Journal of psychopharmacology 2008, 22, 621–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Griffiths, R.R.; Richards, W.A.; McCann, U.; Jesse, R. Psilocybin can occasion mystical-type experiences having substantial and sustained personal meaning and spiritual significance. Psychopharmacology 2006, 187, 268–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harding, F.; Seynaeve, M.; Keeler, J.; Himmerich, H.; Treasure, J.; Kan, C. Perspectives on psychedelic treatment and research in eating disorders: a web-based questionnaire study of people with eating disorders. Journal of integrative neuroscience 2021, 20, 551–560. [Google Scholar]

- Hartogsohn, I. The meaning-enhancing properties of psychedelics and their mediator role in psychedelic therapy, spirituality, and creativity. Frontiers in neuroscience 2018, 12, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendricks, P.S. Awe: A putative mechanism underlying the effects of classic psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy. International Review of Psychiatry 2018, 30, 331–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendricks, P.S.; Copes, H.; Family, N.; Williams, L.T.; Luke, D.; Raz, S. Perceptions of safety, subjective effects, and beliefs about the clinical utility of lysergic acid diethylamide in healthy participants within a novel intervention paradigm: Qualitative results from a proof-of-concept study. Journal of Psychopharmacology 2022, 36, 337–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Himmerich, H.; Bentley, J.; Kan, C.; Treasure, J. Genetic risk factors for eating disorders: an update and insights into pathophysiology. Therapeutic advances in psychopharmacology 2019, 9, 2045125318814734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Himmerich, H.; Kan, C.; Au, K.; Treasure, J. Pharmacological treatment of eating disorders, comorbid mental health problems, malnutrition and physical health consequences. Pharmacology & therapeutics 2021, 217, 107667. [Google Scholar]

- Himmerich, H.; Treasure, J. Psychopharmacological advances in eating disorders. Expert review of clinical pharmacology 2018, 11, 95–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoek, H.W. Incidence, prevalence and mortality of anorexia nervosa and other eating disorders. Current opinion in psychiatry 2006, 19, 389–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hudson, J.I.; Hiripi, E.; Pope Jr, H.G.; Kessler, R.C. The prevalence and correlates of eating disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Biological psychiatry 2007, 61, 348–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Insel, T.; Cuthbert, B.; Garvey, M.; Heinssen, R.; Pine, D.S.; Quinn, K. ,... & Wang, P. Research domain criteria (RDoC): toward a new classification framework for research on mental disorders. American Journal of psychiatry 2010, 167, 748–751. [Google Scholar]

- Ioannidis, J. Effectiveness of antidepressants: an evidence myth constructed from a thousand randomized trials? Philosophy, Ethics, and Humanities in Medicine 2008, 3, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, M.W.; Garcia-Romeu, A.; Griffiths, R.R. Long-term follow-up of psilocybin-facilitated smoking cessation. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse 2017, 43, 55–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, M.W.; Hendricks, P.S.; Barrett, F.S.; Griffiths, R.R. Classic psychedelics: An integrative review of epidemiology, therapeutics, mystical experience, and brain network function. Pharmacology & therapeutics 2019, 197, 83–102. [Google Scholar]

- Jungaberle, H.; Thal, S.; Zeuch, A.; Rougemont-Bücking, A.; von Heyden, M.; Aicher, H.; Scheidegger, M. Positive psychology in the investigation of psychedelics and entactogens: A critical review. Neuropharmacology 2018, 142, 179–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabat-Zinn, J. Mindfulness-based interventions in context: Past, present, and future. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice 2003, 10, 144–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karjalainen, L.; Gillberg, C.; Råstam, M.; Wentz, E. Eating disorders and eating pathology in young adult and adult patients with ESSENCE. Comprehensive Psychiatry 2016, 66, 79–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, J.R.; Gillan, C.M.; Prenderville, J.; Harkin, A.; Clarke, G.; O'Keane, V. Psychedelic therapy's Transdiagnostic effects: A Research Domain Criteria (RDoC) Systems Perspective. Frontiers in Psychiatry 2021, 2295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knudsen, G.M. Sustained effects of single doses of classical psychedelics in humans. Neuropsychopharmacology 2022, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koning, E.; Brietzke, E. Psilocybin-Assisted Psychotherapy as a Potential Treatment for Eating Disorders: a Narrative Review of Preliminary Evidence. Trends in Psychiatry and Psychotherapy. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krebs, T.S.; Johansen P, Ø. Psychedelics and mental health: a population study. PloS one 2013, 8, e63972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreplin, U.; Farias, M.; Brazil, I.A. The limited prosocial effects of meditation: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Scientific reports 2018, 8, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lafrance, A.; Loizaga-Velder, A.; Fletcher, J.; Renelli, M.; Files, N.; Tupper, K.W. Nourishing the spirit: exploratory research on ayahuasca experiences along the continuum of recovery from eating disorders. Journal of psychoactive drugs 2017, 49, 427–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lafrance, A.; Strahan, E.; Bird, B.M.; St Pierre, M.; Walsh, Z. Classic Psychedelic Use and Mechanisms of Mental Health: Exploring the Mediating Roles of Spirituality and Emotion Processing on Symptoms of Anxiety, Depressed Mood, and Disordered Eating in a Community Sample. Journal of Humanistic Psychology 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebedev, A.V.; Lövdén, M.; Rosenthal, G.; Feilding, A.; Nutt, D.J.; Carhart-Harris, R.L. Finding the self by losing the self: Neural correlates of ego-dissolution under psilocybin. Human brain mapping 2015, 36, 3137–3153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leichsenring, F.; Luyten, P.; Hilsenroth, M.J.; Abbass, A.; Barber, J.P.; Keefe, J.R.; Leweke, F.; Rabung, S.; Steinert, C. Psychodynamic therapy meets evidence-based medicine: a systematic review using updated criteria. The Lancet Psychiatry 2015, 2, 648–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levitt, H.M.; Bamberg, M.; Creswell, J.W.; Frost, D.M.; Josselson, R.; Suárez-Orozco, C. Journal article reporting standards for qualitative primary, qualitative meta analytic, and mixed methods research in psychology: The APA Publications and Communications Board task force report. American Psychologist 2018, 73, 26–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linardon, J.; Fairburn, C.G.; Fitzsimmons-Craft, E.E.; Wilfley, D.E.; Brennan, L. The empirical status of the third-wave behaviour therapies for the treatment of eating disorders: A systematic review. Clinical psychology review 2017, 58, 125–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Linardon, J.; Hindle, A.; Brennan, L. Dropout from cognitive-behavioral therapy for eating disorders: A meta-analysis of randomized, controlled trials. International Journal of Eating Disorders 2018, 51, 381–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luoma, J.B.; Chwyl, C.; Bathje, G.J.; Davis, A.K.; Lancelotta, R. A meta analysis of placebo-controlled trials of psychedelic-assisted therapy. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs 2020, 52, 289–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ly, C.; Greb, A.C.; Cameron, L.P.; Wong, J.M.; Barragan, E.V.; Wilson, P.C. ,... & Olson, D. E. Psychedelics promote structural and functional neural plasticity. Cell reports 2018, 23, 3170–3182. [Google Scholar]

- Machek, S.B. Psychedelics: Overlooked Clinical Tools with Unexplored Ergogenic Potential. Journal of Exercise and Nutrition 2019, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Malcolm, B.; Thomas, K. Serotonin toxicity of serotonergic psychedelics. Psychopharmacology 2021, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McElroy, S.L.; Guerdjikova, A.I.; Mori, N.; Keck, P.E. Psychopharmacologic treatment of eating disorders: emerging findings. Current Psychiatry Reports 2015, 17, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michael, P.; Luke, D.; Robinson, O. An encounter with the other: A thematic and content analysis of DMT experiences from a naturalistic field study. Frontiers in psychology 2021, 5731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millière, R.; Carhart-Harris, R.L.; Roseman, L.; Trautwein, F.M.; Berkovich-Ohana, A. Psychedelics, meditation, and self-consciousness. Frontiers in psychology 2018, 9, 1475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mind. Treatment and support for eating problems. https://www.mind.org.uk/information-support/types-of-mental-healthproblems/eating-problems/treatment-support/ 2021.

- Moessner, M.; Bauer, S. (2017). Maximizing the public health impact of eating disorder services: a simulation study. International Journal of Eating Disorders 2021, 50, 1378–1384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monge, M.C.; Forman, S.F.; McKenzie, N.M.; Rosen, D.S.; Mammel, K.A.; Callahan S, T. ,... & Woods, E.R. Use of psychopharmacologic medications in adolescents with restrictive eating disorders: analysis of data from the National Eating Disorder Quality Improvement Collaborative. Journal of Adolescent Health 2015, 57, 66–72. [Google Scholar]

- Monteleone, A.M.; Pellegrino, F.; Croatto, G.; Carfagno, M.; Hilbert, A.; Treasure, J.; Wade, T.; Bulik, C.M.; Zipfel, S.; Hay, P.; Schmidt, U.; Castellini, G.; Favaro, A.; Fernandez-Aranda, F.; Shin, J.I.; Voderholzer, U.; Ricca, V.; Moretti, D.; Busatta, D. ,... Solmi, M. Treatment of eating disorders: A systematic meta-review of meta-analyses and network meta-analyses. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews 2022, 142, 104857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreton, S.G.; Burden-Hill, A.; Menzies, R.E. Reduced death anxiety and obsessive beliefs as mediators of the therapeutic effects of psychedelics on obsessive compulsive disorder symptomology. Clinical Psychologist 2022, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, R.; Kettner, H.; Zeifman, R.; Giribaldi, B.; Kartner, L.; Martell, J.; Read, T.; Murphy-Beiner, A.; Baker-Jones, M.; Nutt, D.; Erritzoe, D.; Watts, R.; Carhart-Harris, R. Therapeutic Alliance and Rapport Modulate Responses to Psilocybin Assisted Therapy for Depression. Frontiers in pharmacology 2022, 12, 788155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murphy-Beiner, A. , & Soar, K. Ayahuasca’s ‘afterglow’: improved mindfulness and cognitive flexibility in ayahuasca drinkers. Psychopharmacology 2020, 237, 1161–1169. [Google Scholar]

- Muttoni, S.; Ardissino, M.; John, C. Classical psychedelics for the treatment of depression and anxiety: A systematic review. Journal of affective disorders 2019, 258, 11–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Library of Medicine (U.S.). (2019, August). Effects of Psilocybin in Anorexia Nervosa. Identifier NCT04052568. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04052568.

- National Library of Medicine (U.S.). (2021, May). Psilocybin as a Treatment for Anorexia Nervosa: A Pilot Study. Identifier NCT04505189. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04505189.

- National Library of Medicine (U.S.). (2022, August). Efficacy and Safety of COMP360 Psilocybin Therapy in Anorexia Nervosa: A Proof-Of-Concept Study. Identifier NCT05481736. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT05481736.

- Nichols, D.E. Psychedelics. Pharmacological reviews 2016, 68, 264–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nichols, D.E.; Johnson, M.W.; Nichols, C.D. Psychedelics as medicines: an emerging new paradigm. Clinical Pharmacology & Therapeutics 2017, 101, 209–219. [Google Scholar]

- Nutt, D. Illegal drugs laws: clearing a 50-year-old obstacle to research. PLoS biology 2015, 13, e1002047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nutt, D. Psychedelic drugs—a new era in psychiatry? Dialogues in clinical neuroscience. 2022, 21, 139–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nutt, D.; Carhart-Harris, R. The current status of psychedelics in psychiatry. JAMA psychiatry 2021, 78, 121–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nutt, D.; Erritzoe, D.; Carhart-Harris, R. Psychedelic psychiatry’s brave new world. Cell 2020, 181, 24–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olson, D.E. The subjective effects of psychedelics may not be necessary for their enduring therapeutic effects. ACS Pharm Trans Sci 2020, 4, 563–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ona, G. Inside bad trips: Exploring extra-pharmacological factors. Journal of Psychedelic Studies 2018, 2, 53–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orłowski, P.; Ruban, A.; Szczypiński, J.; Hobot, J.; Bielecki, M.; Bola, M. Naturalistic use of psychedelics is related to emotional reactivity and self consciousness: The mediating role of ego-dissolution and mystical experiences. Journal of Psychopharmacology 2022, 02698811221089034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parliament Publications. House of Commons Public Administration and Constitutional Affairs Committee. (2019). Ignoring the Alarms follow-up: Too many avoidable deaths from eating disorders (Seventeenth Report of Session 2017–19). https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm201719/cmselect/cmpubadm/855/855.pdf.

- Patton, M.Q. (2002). Qualitative research & evaluation methods. SAGE Publications.

- Preller, K.H.; Vollenweider, F.X. Phenomenology, structure, and dynamic of psychedelic states. Behavioral neurobiology of psychedelic drugs 2016, 221–256. [Google Scholar]

- Pisetsky, E.M.; Thornton, L.M.; Lichtenstein, P.; Pedersen, N.L.; Bulik, C.M. Suicide attempts in women with eating disorders. Journal of abnormal psychology 2013, 122, 1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reiff, C.M.; Richman, E.E.; Nemeroff, C.B.; Carpenter, L.L.; Widge, A.S.; Rodriguez C, I. ,... & Work Group on Biomarkers and Novel Treatments, a Division of the American Psychiatric Association Council of Research. Psychedelics and psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy. American Journal of Psychiatry 2020, 177, 391–410. [Google Scholar]

- Renelli, M.; Fletcher, J.; Loizaga-Velder, A.; Files, N.; Tupper, K.; Lafrance, A. (2018). Ayahuasca and the healing of eating disorders. In Embodiment and eating disorders (pp. 214-230). Routledge.

- Renell, M.; Fletcher, J.; Tupper, K.W.; Files, N.; Loizaga-Velder, A.; Lafrance, A. An exploratory study of experiences with conventional eating disorder treatment and ceremonial ayahuasca for the healing of eating disorders. Eating and Weight Disorders-Studies on Anorexia,Bulimia and Obesity 2020, 25, 437–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renelli, M.; Fletcher, J.; Tupper, K.W.; Files, N.; Loizaga-Velder, A.; Lafrance, A. An exploratory study of experiences with conventional eating disorder treatment and ceremonial ayahuasca for the healing of eating disorders. Eating and Weight Disorders-Studies on Anorexia, Bulimia and Obesity 2018, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renelli, M.; Fletcher, J.; Tupper, K.W.; Files, N.; Loizaga-Velder, A.; Lafrance, A. An exploratory study of experiences with conventional eating disorder treatment and ceremonial ayahuasca for the healing of eating disorders. Eating and Weight Disorders-Studies on Anorexia, Bulimia and Obesity 2020, 25, 437–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rome, E.S.; Ammerman, S. Medical complications of eating disorders: an update. Journal of adolescent health 2003, 33, 418–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romeo, B.; Hermand, M.; Pétillion, A.; Karila, L.; Benyamina, A. Clinical and biological predictors of psychedelic response in the treatment of psychiatric and addictive disorders: A systematic review. Journal of Psychiatric Research 2021, 137, 273–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romeo, B.; Karila, L.; Martelli, C.; Benyamina, A. Efficacy of psychedelic treatments on depressive symptoms: A meta-analysis. Journal of Psychopharmacology 2020, 34, 1079–1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Root, T.L.; Pisetsky, E.M.; Thornton, L.; Lichtenstein, P.; Pedersen, N.L.; Bulik, C. Patterns of co-morbidity of eating disorders and substance use in Swedish females. Psychological medicine 2010, 40, 105–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roseman, L.; Haijen, E.; Idialu-Ikato, K.; Kaelen, M.; Watts, R.; Carhart-Harris, R. Emotional breakthrough and psychedelics: validation of the emotional breakthrough inventory. Journal of Psychopharmacology 2019, 33, 1076–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roseman, L.; Nutt, D.J.; Carhart-Harris, R.L. Quality of acute psychedelic experience predicts therapeutic efficacy of psilocybin for treatment-resistant depression. Frontiers in pharmacology 2018, 8, 974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, S.; Bossis, A.; Guss, J.; Agin-Liebes, G.; Malone, T.; Cohen, B. ,... & Schmidt, B.L. Rapid and sustained symptom reduction following psilocybin treatment for anxiety and depression in patients with life-threatening cancer: a randomized controlled trial. Journal of psychopharmacology 2016, 30, 1165–1180. [Google Scholar]

- Rucker, J.J.; Iliff, J.; Nutt, D.J. Psychiatry & the psychedelic drugs. Past, present & future. Neuropharmacology 2018, 142, 200–218. [Google Scholar]

- Rucker, J.J.; Marwood, L.; Ajantaival RL, J.; Bird, C.; Eriksson, H.; Harrison, J. ,... & Young, A. H. The effects of psilocybin on cognitive and emotional functions in healthy participants: results from a phase 1, randomised, placebo-controlled trial involving simultaneous psilocybin administration and preparation. Journal of Psychopharmacology 2019, 02698811211064720. [Google Scholar]

- Schenberg, E.E. Psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy: a paradigm shift in psychiatric research and development. Frontiers in pharmacology 2018, 9, 733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schimmel, N.; Breeksema, J.J.; Smith-Apeldoorn, S.Y.; Veraart, J.; van den Brink, W.; Schoevers, R.A. Psychedelics for the treatment of depression, anxiety, and existential distress in patients with a terminal illness: a systematic review. Psychopharmacology 2021, 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Schlag, A.K.; Aday, J.; Salam, I.; Neill, J.C.; Nutt, D.J. Adverse effects of psychedelics: From anecdotes and misinformation to systematic science. Journal of Psychopharmacology 2022, 36, 258–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmidt, U.; Adan, R.; Böhm, I.; Campbell, I.C.; Dingemans, A.; Ehrlich, S. ,... & Zipfel, S. Eating disorders: the big issue. The Lancet Psychiatry 2016, 3, 313–315. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Shalev, A.; Liberzon, I.; Marmar, C. Post-traumatic stress disorder. New England journal of medicine 2017, 376, 2459–2469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smink, F.R.; van Hoeken, D.; Hoek, H.W. Epidemiology, course, and outcome of eating disorders. Current opinion in psychiatry 2013, 26, 543–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Södersten, P.; Bergh, C.; Leon, M.; Brodin, U.; Zandian, M. Cognitive behavior therapy for eating disorders versus normalization of eating behavior. Physiology & behavior 2017, 174, 178–190. [Google Scholar]

- Solmi, M.; Monaco, F.; Højlund, M.; Monteleone, A.M.; Trott, M.; Firth, J.; Carfagno, M.; Eaton, M.; De Toffol, M.; Vergine, M.; Meneguzzo, P.; Collantoni, E.; Gallicchio, D.; Stubbs, B.; Girardi, A.; Busetto, P.; Favaro, A.; Carvalho, A.F.; Steinhausen, H.; Correll, C.U. Outcomes in people with eating disorders: a transdiagnostic and disorder-specific systematic review, meta-analysis and multivariable meta-regression analysis. World Psychiatry 2024, 23, 124–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solmi, M.; Wade, T.D.; Byrne, S.; Del Giovane, C.; Fairburn, C.G.; Ostinelli, E.G.; De Crescenzo, F.; Johnson, C.; Schmidt, U.; Treasure, J.; Favaro, A.; Zipfel, S.; Cipriani, A. Comparative efficacy and acceptability of psychological interventions for the treatment of adult outpatients with anorexia nervosa: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. The Lancet Psychiatry 2021, 8, 215–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spence, S.; Courbasson, C. The role of emotional dysregulation in concurrent eating disorders and substance use disorders. Eating behaviors 2012, 13, 382–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spriggs, M.J.; Douglass, H.M.; Park, R.J.; Read, T.; Danby, J.L.; de Magalhães, F.J. ,... & Carhart-Harris, R. L. Study Protocol for “Psilocybin as a Treatment for Anorexia Nervosa: A Pilot Study”. Frontiers in Psychiatry 2021, 1770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spriggs, M.J.; Kettner, H.; Carhart-Harris, R.L. Positive effects of psychedelics on depression and wellbeing scores in individuals reporting an eating disorder. Eat Weight Disord 2021, 26, 1265–1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Streatfeild, J.; Hickson, J.; Austin, S.B.; Hutcheson, R.; Kandel, J.S.; Lampert, J.G. ,... & Pezzullo, L. Social and economic cost of eating disorders in the United States: Evidence to inform policy action. International Journal of Eating Disorders 2021, 54, 851–868. [Google Scholar]

- Strober, M.; Johnson, C. The need for complex ideas in anorexia nervosa: Why biology, environment, and psyche all matter, why therapists make mistakes, and why clinical benchmarks are needed for managing weight correction. The International Journal of Eating Disorders 2012, 45, 155–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Svaldi, J.; Griepenstroh, J.; Tuschen-Caffier, B.; Ehring, T. Emotion regulation deficits in eating disorders: A marker of eating pathology or general psychopathology? Psychiatry Research 2012, 197, 103–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, P.J.; Johnson, M.W.; Timmermann, C.; Watts, R.; Erritzoe, D.; Douglass, H. ,... & Carhart-Harris, R. L. Psychedelics and health behaviour change. Journal of Psychopharmacology 2022, 36, 12–19. [Google Scholar]

- Tupper, K.W.; Wood, E.; Yensen, R.; Johnson, M.W. Psychedelic medicine: a re emerging therapeutic paradigm. Cmaj 2015, 187, 1054–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uthaug, M.V.; Van Oorsouw, K.; Kuypers KP, C.; Van Boxtel, M.; Broers, N.J.; Mason, N.L. ,... & Ramaekers, J. G. Sub-acute and long-term effects of ayahuasca on affect and cognitive thinking style and their association with ego dissolution. Psychopharmacology 2018, 235, 2979–2989. [Google Scholar]

- Uthaug, M.V.; Lancelotta, R.; Van Oorsouw, K.; Kuypers KP, C.; Mason, N.; Rak, J. ,... & Ramaekers, J. G. A single inhalation of vapor from dried toad secretion containing 5-methoxy-N, N-dimethyltryptamine (5-MeO-DMT) in a naturalistic setting is related to sustained enhancement of satisfaction with life, mindfulness related capacities, and a decrement of psychopathological symptoms. Psychopharmacology 2019, 236, 2653–2666. [Google Scholar]

- Vaismoradi, M.; Jones, J.; Turunen, H.; Snelgrove, S. Theme development in qualitative content analysis and thematic analysis. Journal of Nursing Education and Practice 2016, 6, 100–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Eeden, A.E.; van Hoeken, D.; Hoek, H.W. Incidence, prevalence and mortality of anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa. Current Opinion in Psychiatry 2021, 34, 515–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Hoeken, D.; Hoek, H.W. Review of the burden of eating disorders: mortality, disability, costs, quality of life, and family burden. Current opinion in psychiatry 2020, 33, 521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargas, M.V.; Meyer, R.; Avanes, A.A.; Rus, M.; Olson, D.E. Psychedelics and other psychoplastogens for treating mental illness. Frontiers in Psychiatry 2021, 1691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vollenweider, F.X.; Preller, K.H. Psychedelic drugs: neurobiology and potential for treatment of psychiatric disorders. Nature Reviews Neuroscience 2020, 21, 611–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waller, G. Recent advances in psychological therapies for eating disorders. F1000 Research 2016, 5, 702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treasure, J.; Cardi, V.; Leppanen, J.; Turton, R. New treatment approaches for severe and enduring eating disorders. Physiology & Behavior, 2015; 152(Pt B), 456–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watts, R.; Day, C.; Krzanowski, J.; Nutt, D.; Carhart-Harris, R. Patients’ accounts of increased “connectedness” and “acceptance” after psilocybin for treatment-resistant depression. Journal of humanistic psychology 2017, 57, 520–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wheeler, S.W.; Dyer, N.L. A systematic review of psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy for mental health: An evaluation of the current wave of research and suggestions for the future. Psychology of Consciousness: Theory, Research, and Practice 2020, 7, 279–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, M.; Crotty, S.; Callon, C.; Lafrance, A. Ceremony Leaders’ Perspectives on the Good, the Bad, and the Ugly of Ayahuasca Drinking in Ceremonial Contexts. The Journal 2022, 54, 142. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, M.; Miller, A.K.; Lafrance, A. Ayahuasca ceremony leaders’ perspectives on special considerations for eating disorders. Eating Disorders 2023, 32, 120–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, T.G.; Grilo, C.M.; Vitousek, K.M. Psychological treatment of eating disorders. American Psychologist 2007, 62, 199–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, D.; Wang, K.; Wei, D.; Chen, Q.; Du, X.; Yang, J.; Qiu, J. Perfectionism mediated the relationship between brain structure variation and negative emotion in a nonclinical sample. Cognitive, Affective, & Behavioral Neuroscience 2017, 17, 211–223. [Google Scholar]

- Yaden, D.B.; Griffiths, R.R. The subjective effects of psychedelics are necessary for their enduring therapeutic effects. ACS Pharmacology & Translational Science 2020, 4, 568–572. [Google Scholar]

- Zeifman, R.; Spriggs, M.J.; Kettner, H.; Lyons, T.; Rosas, F.; Mediano, P. ,...Carhart-Harris, R. (2022, July 7). From Relaxed Beliefs Under Psychedelics (REBUS) to Revised Beliefs After Psychedelics (REBAS): Preliminary Development of the RElaxed Beliefs Questionnaire (REB-Q). [CrossRef]

- Zimmerman, J.; Fisher, M. Avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder (ARFID). Current problems in pediatric and adolescent health care 2017, 47, 95–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Substance | Derivation or chemical analogues | General effects and properties | Potential harms* | Potential therapeutic use |

| LSD | Ergot fungus (Claviceps purpurea); morning glory (Turbina corymbosa); Hawaiian baby woodrose (Argyreia nervosa) - sources of ergine or lysergic acid amide | - 5-HT2A (serotonin) agonist of pyramidal neurons - Dizziness, weakness, tremors, paresthesia - Altered consciousness (visions, auditory distortions, ideations) - Altered mood (happy, sad, fearful, irritable) - Distorted sense of space, time |

- Psychosis - Hallucinogen persisting perception disorder |

- Addiction (e.g., alcohol) - Anxiety associated with terminal illness |

| Psilocybin | Psilocybe and other genera of mushroom (various species) | - 5-HT2A (serotonin) agonist of pyramidal neurons - Dizziness, weakness, tremors, paresthesia - Altered consciousness (visions, auditory distortions, ideations) - Altered mood (happy, sad, fearful, irritable) - Distorted sense of space, time |

- Psychosis - Hallucinogen persisting perception disorder |

- Addiction (e.g., tobacco, alcohol) - Anxiety associated with terminal illness |

| Ayahuasca brew (admixtures contain DMT) | Chacruna leaf (Psychotria viridis); Chagropanga vine (Diplopterys cabrerana); ayahuasca vine (Banisteriopsis caapi); assorted other admixture plants | - 5-HT2A (serotonin) agonist of pyramidal neurons - Dizziness, weakness, tremors, paresthesia - Nausea, emesis - Altered consciousness (visions, auditory distortions, ideations) - Altered mood (happy, sad, fearful, irritable) - Distorted sense of space, time |

- Psychosis - Serotonin syndrome and other dangers from medication interactions due to monoamine oxidase inhibitory activity |

- Addiction (alcohol, cocaine, tobacco) - Depression, anxiety |

| Mescaline | Peyote cactus (Lophophora williamsii); San Pedro cactus (Echinopsis pachanoi) | - 5-HT2A (serotonin) agonist of pyramidal neurons - Dizziness, weakness, tremors, paresthesia - Altered consciousness (visions, auditory distortions, ideations) - Altered mood (happy, sad, fearful, irritable) - Distorted sense of space, time |

- Psychosis | - Addiction (alcohol) |

| MDMA | Sassafras tree (Sassafras albidum) - source of safrole, precursor chemical | - Serotonin, dopamine and noradrenaline agonist - Euphoria - Arousal - Perceptual alteration - Enhanced empathy and sociability |

- Potential neurocognitive deficits (e.g. memory impairment) - Sleep disruption - Short-term depression |

- PTSD |

| Note: DMT = dimethyltryptamine, LSD = lysergic acid dimethylamide, MDMA = Methylenedioxymethamphetamine, PTSD = posttraumatic stress disorder. *Potential harms identified here are associated with unsupervised uses of psychedelic substances (often in the context of polysubstance use); current clinical studies on psychedelic agents have not reported such chronic adverse sequelae. Potential therapeutic uses are identified based on evidence from past (i.e., 1950s-1960s) and current research of psychedelic drugs. | ||||

| M (SD) | Range | N (%) | |

| Age | 36.9 (11.33) | 25-54 | 8 |

| Gender | |||

| Female | 7 (87.5%) | ||

| Non-binary (NB) | 1 (12.5%) | ||

| Education (highest level completed) | |||

| GCSEs | 1 (12.5%) | ||

| A level | 1 (12.5%) | ||

| Undergraduate degree | 2 (25%) | ||

| Postgraduate degree | 4 (50%) | ||

| Eating disorder (multiple diagnosis) | |||

| Anorexia nervosa | 7 (87.5%) | ||

| Bulimia nervosa | 2 (25%) | ||

| Other specified feeding or eating disorder | 1 (12.5%) | ||

| Orthorexia nervosa | 1 (12.5%) | ||

| Binge eating disorder | 1 (12.5%) | ||

| Disordered eating | 1 (12.5%) |

|

| Superordinate themes | Subordinate themes |

|---|---|

| ‘Exploring’ via ‘the gateway to healing’ |

‘Freedom’ to ‘expand’ and ‘explore your mind' |

| ‘Navigating the roadmap through your subconscious emotions’ | |

| Transcendence: ‘it’s not a theoretical knowledge, it’s a deep knowing’ | |

| ‘Transformation’ and being ‘able to do the work’ |

Cognitive: ‘they’ve opened me up’ |

| Behavioural: ‘start making changes’ | |

| Safety perceptions: ‘medicine’ but ‘not a magic pill’ |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).