Submitted:

06 September 2024

Posted:

09 September 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

Theoretical Framework and Hypothesis

2. Method

2.1. Data Collection and Sample

2.2. Instruments

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics

3.2. Moderation Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusion and Practical Implications

6. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Teresi, M.; Pietroni, D.D.; Barattucci, M.; Giannella, V.A.; Pagliaro, S. Ethical Climate(s), Organizational Identification, and Employees’ Behavior. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elçi, M.; Karabay, M.E.; Akyüz, B. Investigating the Mediating Effect of Ethical Climate on Organizational Justice and Burnout: A Study on Financial Sector. Procedia - Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 207, 587–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elçi, M.; Alpkan, L. The Impact of Perceived Organizational Ethical Climate on Work Satisfaction. J. Bus. Ethic- 2009, 84, 297–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borrelli, I.; Rossi, M.F.; Melcore, G.; Perrotta, A.; Santoro, P.E.; Gualano, M.R.; Moscato, U. WORKPLACE ETHICAL CLIMATE AND WORKERS' BURNOUT: A SYSTEMATIC REVIEW. 2023, 20, 405–414. [CrossRef]

- Tehranineshat, B.; Torabizadeh, C.; Bijani, M. A study of the relationship between professional values and ethical climate and nurses' professional quality of life in Iran. Int. J. Nurs. Sci. 2020, 7, 313–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asgari, S.; Shafipour, V.; Taraghi, Z.; Yazdani-Charati, J. Relationship between moral distress and ethical climate with job satisfaction in nurses. Nurs. Ethic- 2019, 26, 346–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okpara, J.O.; Wynn, P. The impact of ethical climate on job satisfaction, and commitment in Nigeria. J. Manag. Dev. 2008, 27, 935–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sillero, A.S.; Margañon, R.A.; Moreno-Segura, N.; Carrasco, J.J.; Atef, H.; Margañon, S.A.; Marques-Sule, E. Physiotherapists’ Ethical Climate and Work Satisfaction: A STROBE-Compliant Cross-Sectional Study. Healthcare 2023, 11, 2631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayub, A.; Khan, A.J.; Ahmed, T.; Ansari, M.A.A. Examining the Relationship between Ethical Climate and Burnout Using Role Stress Theory. Rev. Educ. Adm. LAW 2022, 5, 01–09. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivaz, M.; Asadi, F.; Mansouri, P. Assessment of the Relationship between Nurses’ Perception of Ethical Climate and Job Burnout in Intensive Care Units. Investig. Y Educ. En Enfermeria 2020, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleh, T.A.; Sarwar, A.; Islam, A.; Mohiuddin, M.; Su, Z. Effects of Leader Conscientiousness and Ethical Leadership on Employee Turnover Intention: The Mediating Role of Individual Ethical Climate and Emotional Exhaustion. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Heal. 2022, 19, 8959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atabay, G.; Çangarli, B.G. ; Penbek,. Impact of ethical climate on moral distress revisited. Nurs. Ethic- 2015, 22, 103–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, N.; Wu, Y.-K. Work-Related Stress and Psychological Distress among Law Enforcement Officers: The Carolina Blue Project. Healthcare 2024, 12, 688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noh, Y.G.; Kim, S.Y. Factors of Hospital Ethical Climate among Hospital Nurses in Korea: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Healthcare 2024, 12, 372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dzeng, E.; Curtis, J.R. Understanding ethical climate, moral distress, and burnout: a novel tool and a conceptual framework. BMJ Qual. Saf. 2018, 27, 766–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maslach, C.; Schaufeli, W.B.; Leiter, M.P. Job Burnout. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2001, 52, 397–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Victor, B.; Cullen, J.B. The Organizational Bases of Ethical Work Climates. Adm. Sci. Q. 1988, 33, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santiago-Torner, C. Ethical Climate and Creativity: The Moderating Role of Work Autonomy and the Mediator Role of Intrinsic Motivation. Cuad. De Gest. 2023, 23, 93–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.; He, X. Role Stress, Job Autonomy, and Burnout: The Mediating Effect of Job Satisfaction among Social Workers in China. J. Soc. Serv. Res. 2022, 48, 365–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farfán, J.; Peña, M.; Fernández-Salinero, S.; Topa, G. The Moderating Role of Extroversion and Neuroticism in the Relationship between Autonomy at Work, Burnout, and Job Satisfaction. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Heal. 2020, 17, 8166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E. Job demands–resources theory: Taking stock and looking forward. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2017, 22, 273–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubicek, B.; Paškvan, M.; Bunner, J. The Bright and Dark Sides of Job Autonomy. In Job Demands in a Changing World of Work; Korunka, C., Kubicek, B., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 45–63. [Google Scholar]

- Ter Hoeven, C.L.; van Zoonen, W.; Fonner, K.L. The practical paradox of technology: The influence of communication technology use on employee burnout and engagement. Commun. Monogr. 2016, 83, 239–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fastje, F.; Mesmer-Magnus, J.; Guidice, R.; Andrews, M.C. Employee burnout: the dark side of performance-driven work climates. J. Organ. Eff. People Perform. 2023, 10, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. Research on intrinsic and extrinsic motivation is alive, well, and reshaping 21st-century management approaches: Brief reply to Locke and Schattke (2019). Motiv. Sci. 2019, 5, 291–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Zapata, O.; Pascual, A.S.; Álvarez-Hernández, G.; Collado, C.C. Knowledge work intensification and self-management: the autonomy paradox. Work. Organ. Labour Glob. 2016, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gössling, T. The Price of Morality. An Analysis of Personality, Moral Behaviour, and Social Rules in Economic Terms. J. Bus. Ethic- 2003, 45, 121–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E.L.; Olafsen, A.H.; Ryan, R.M. Self-Determination Theory in Work Organizations: The State of a Science. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 2017, 4, 19–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinibutun, S.R.; Kuzey, C.; Dinc, M.S. The Effect of Organizational Climate on Faculty Burnout at State and Private Universities: A Comparative Analysis. SAGE Open 2020, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borry, E.L. Ethical climate and rule bending: how organizational norms contribute to unintended rule consequences. Public Adm. 2017, 95, 78–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLinton, S.S.; Jamieson, S.D.; Tuckey, M.R.; Dollard, M.F.; Owen, M.S. Evidence for a Negative Loss Spiral between Co-Worker Social Support and Burnout: Can Psychosocial Safety Climate Break the Cycle? Healthcare 2023, 11, 3168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindeberg, S.I.; Rosvall, M.; Choi, B.; Canivet, C.; Isacsson, S.-O.; Karasek, R.; Östergren, P.-O. Psychosocial working conditions and exhaustion in a working population sample of Swedish middle-aged men and women. Eur. J. Public Heal. 2011, 21, 190–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kammeyer-Mueller, J.D.; Simon, L.S.; Rich, B.L. The Psychic Cost of Doing Wrong: Ethical Conflict, Divestiture Socialization, and Emotional Exhaustion. Journal of Managemen. J. Manag. 2012, 38, 784–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Besser-Jones, L. Personal Integrity, Morality and Psychological Well-Being: Justifying the Demands of Morality. 2008, 5, 361–383. [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S. E. , & Lilly, R. S. ( 21(2), 128–148. [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S.E.; Halbesleben, J.; Neveu, J.-P.; Westman, M. Conservation of Resources in the Organizational Context: The Reality of Resources and Their Consequences. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 2018, 5, 103–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luna, D.; Figuerola-Escoto, R.P.; Sienra-Monge, J.J.L.; Hernández-Roque, A.; Soria-Magaña, A.; Hernández-Corral, S.; Toledano-Toledano, F. Burnout and Its Relationship with Work Engagement in Healthcare Professionals: A Latent Profile Analysis Approach. Healthcare 2023, 11, 3042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johlke, M.C.; Iyer, R. A model of retail job characteristics, employee role ambiguity, external customer mind-set, and sales performance. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2013, 20, 58–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazmanian, M.; Orlikowski, W.J.; Yates, J. The Autonomy Paradox: The Implications of Mobile Email Devices for Knowledge Professionals. Organ. Sci. 2013, 24, 1337–1357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shevchuk, A.; Strebkov, D.; Davis, S.N.; Shevchuk, A.; Strebkov, D.; Davis, S.N. The Autonomy Paradox: How Night Work Undermines Subjective Well-Being of Internet-Based Freelancers. ILR Rev. 2019, 72, 75–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulki, J.P.; Jaramillo, J.F.; Locander, W.B. Effect of Ethical Climate on Turnover Intention: Linking Attitudinal- and Stress Theory. J. Bus. Ethic- 2008, 78, 559–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, N.; Ryan, R.M. Self-Determination Theory. In Development of Self-Determination Through the Life-Course; Wehmeyer, M.L., Shogren, K.A., Little, T.D., Lopez, S.J., Eds.; Springer Science and Business Media LLC: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2017; pp. 47–54. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. Intrinsic and Extrinsic Motivations: Classic Definitions and New Directions. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 2000, 25, 54–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernet, C.; Austin, S.; Trépanier, S.-G.; Dussault, M. How do job characteristics contribute to burnout? Exploring the distinct mediating roles of perceived autonomy, competence, and relatedness. Eur. J. Work. Organ. Psychol. 2013, 22, 123–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edú-Valsania, S.; Laguía, A.; Moriano, J.A. Burnout: A Review of Theory and Measurement. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Heal. 2022, 19, 1780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brislin, R. W. (1980). Cross-Cultural Research Methods. In Environment and Culture (pp. 47–82). Springer US. [CrossRef]

- Vargas, C.; Cañadas, G.A.; Aguayo, R.; Fernández, R.; de la Fuente, E.I. Which occupational risk factors are associated with burnout in nursing? A meta-analytic study. Int. J. Clin. Heal. Psychol. 2014, 14, 28–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artz, B.; Kaya, I.; Kaya, O. Gender role perspectives and job burnout. Rev. Econ. Househ. 2022, 20, 447–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cullen, J.B.; Parboteeah, K.P.; Victor, B. The Effects of Ethical Climates on Organizational Commitment: A Two-Study Analysis. J. Bus. Ethic- 2003, 46, 127–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonett, D.G.; Wright, T.A. Cronbach's alpha reliability: Interval estimation, hypothesis testing, and sample size planning. J. Organ. Behav. 2015, 36, 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagozzi, R.P.; Yi, Y.; Nassen, K.D. Representation of measurement error in marketing variables: Review of approaches and extension to three-facet designs. J. Econ. 1998, 89, 393–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, W. W. (1998). The partial least squares approach to structural equation modeling. In Modern Methods for Business Research (pp. 295–358). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Spreitzer, G.M. Psychological Empowerment in the Workplace: Dimensions, Measurement, and Validation. Acad. Manag. J. 1995, 38, 1442–1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santiago-Torner, C. (2023d). Curvilinear relationship between ethical leadership and creativity within the Colombian electricity sector. The mediating role of work autonomy, affective commitment, and intrinsic motivation. Revista iberoamericana de estudios de desarrollo= Iberoamerican journal of development studies 2023, 12, 74–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W. B. , Leiter, M. P., Maslach, C. Y., & Jackson, S. E. (1996). Maslach Burnout Inventory - General Survey. En C. Maslach, S.E. Jackson y M.P. Leiter (Eds.) The Maslach Burnout Inven - tory-Test Manual (3rd ed.) Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press. Consulting Psychologists Press.

- Santiago Torner, C. (2023c). Teleworking and emotional exhaustion in the Colombian electricity sector: The mediating role of affective commitment and the moderating role of creativity. Intangible Capital 2023, 19, 207–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santiago-Torner, C. Creativity and Emotional Exhaustion in Virtual Work Environments: The Ambiguous Role of Work Autonomy. Eur. J. Investig. Heal. Psychol. Educ. 2024, 14, 2087–2100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salanova, M.; Schaufeli, W.B. Exposure to information technology and its relation to burnout. Behav. Inf. Technol. 2000, 19, 385–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F. Partial, conditional, and moderated moderated mediation: Quantification, inference, and interpretation. Commun. Monogr. 2018, 85, 4–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguinis, H.; Edwards, J.R.; Bradley, K.J. Improving Our Understanding of Moderation and Mediation in Strategic Management Research. Organ. Res. Methods 2017, 20, 665–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J. F. , Ringle, C. M., Sarstedt, M. PLS-SEM: Indeed, a Silver Bullet. Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice 2011, 19, 139–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error: Algebra and statistics. Struct. Equ. MODELS 1981, 18, 382–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernuzzi, C.; Setti, I.; Maffoni, M.; Sommovigo, V. From moral distress to burnout through work-family conflict: the protective role of resilience and positive refocusing. Ethic- Behav. 2021, 32, 578–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, S.-C.S.; Liang, S.-G. When do subordinates' emotion-regulation strategies matter? Abusive supervision, subordinates' emotional exhaustion, and work withdrawal. Leadersh. Q. 2013, 24, 125–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vardaman, J.M.; Gondo, M.B.; Allen, D.G. Ethical climate and pro-social rule breaking in the workplace. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2014, 24, 108–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potard, C.; Landais, C. Relationships between frustration intolerance beliefs, cognitive emotion regulation strategies and burnout among geriatric nurses and care assistants. Geriatr. Nurs. 2021, 42, 700–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santiago-Torner, C.; Tarrats-Pons, E.; Corral-Marfil, J.-A. Effects of Intensity of Teleworking and Creative Demands on the Cynicism Dimension of Job Burnout. Empl. Responsib. Rights J. 2023, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brenkert, G.G. Innovation, rule breaking and the ethics of entrepreneurship. J. Bus. Ventur. 2009, 24, 448–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerdenitsch, C.; Kubicek, B.; Korunka, C. Control in Flexible Working Arrangements. J. Pers. Psychol. 2015, 14, 61–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torner, C.S. Clima ético egoísta y el teletrabajo en el sector eléctrico colombiano. El papel moderador del liderazgo ético. Acta Colomb. De Psicol. 2023, 26, 169–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santiago-Torner, C.; Corral-Marfil, J.-A.; Tarrats-Pons, E. Relationship between Personal Ethics and Burnout: The Unexpected Influence of Affective Commitment. Adm. Sci. 2024, 14, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karasek, R.A., Jr. Job Demands, Job Decision Latitude, and Mental Strain: Implications for Job Redesign. Adm. Sci. Q. 1979, 24, 285–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, T.W.H.; Feldman, D.C. The Moderating Effects of Age in the Relationships of Job Autonomy to Work Outcomes. Work. Aging Retire. 2015, 1, 64–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeuge, A.; Lemmer, K.; Klesel, M.; Kordyaka, B.; Jahn, K.; Niehaves, B. To be or not to be stressed: Designing autonomy to reduce stress at work. Work 2023, 75, 1199–1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taranu, S.M.; Ilie, A.C.; Turcu, A.-M.; Stefaniu, R.; Sandu, I.A.; Pislaru, A.I.; Alexa, I.D.; Sandu, C.A.; Rotaru, T.-S.; Alexa-Stratulat, T. Factors Associated with Burnout in Healthcare Professionals. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Heal. 2022, 19, 14701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pyhältö, K.; Pietarinen, J.; Haverinen, K.; Tikkanen, L.; Soini, T. Teacher burnout profiles and proactive strategies. Eur. J. Psychol. Educ. 2021, 36, 219–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otto, M.C.; Hoefsmit, N.; van Ruysseveldt, J.; van Dam, K. Exploring Proactive Behaviors of Employees in the Prevention of Burnout. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Heal. 2019, 16, 3849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palupi, R.; Findyartini, A. The relationship between gender and coping mechanisms with burnout events in first-year medical students. Korean J. Med Educ. 2019, 31, 331–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Purvanova, R.K.; Muros, J.P. Gender differences in burnout: A meta-analysis. J. Vocat. Behav. 2010, 77, 168–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Constructs | M | SD | Skewness | Kurtosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ethical Climate of Principles (ECP) | 49.94 | 2.43 | -0.24 | 1.28 |

| Work Autonomy (WA) | 1.91 | 2.54 | -0.33 | 1.27 |

| Emotional Exhaustion (EE) | 23.11 | 2.56 | -0.40 | 1.25 |

| Depersonalization (DE) | 20.97 | 3.60 | -0.44 | 1.32 |

| Constructs | N | G | SE | ECP | WA | EE | DE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender (G) | 1 | x | |||||

| Seniority (SE) | 1 | 0.04 | x | ||||

| Ethical Climate of Princ. (ECP) | 11 | 0.08 | 0.04 | 0.72 | |||

| Work Autonomy (WA) | 3 | 0.04 | 0.12* | 0.24* | 0.89 | ||

| Emotional Exhaustion (EE) | 5 | 0.03 | 0.13* | 0.16* | 0.20* | 0.82 | |

| Depersonalization (DE) | 4 | 0.04 | 0.07 | 0.23* | 0.14* | 0.59* | 0.81 |

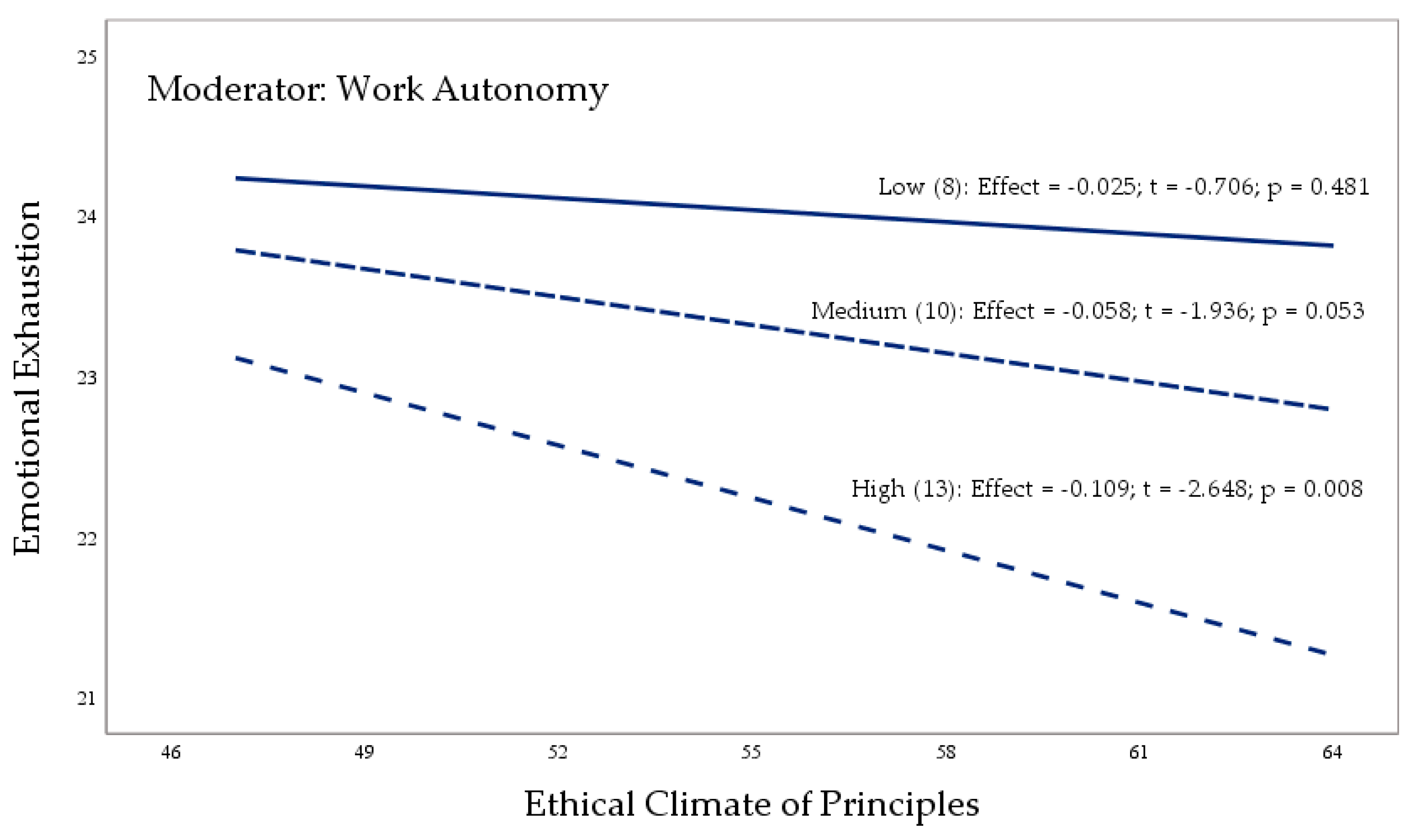

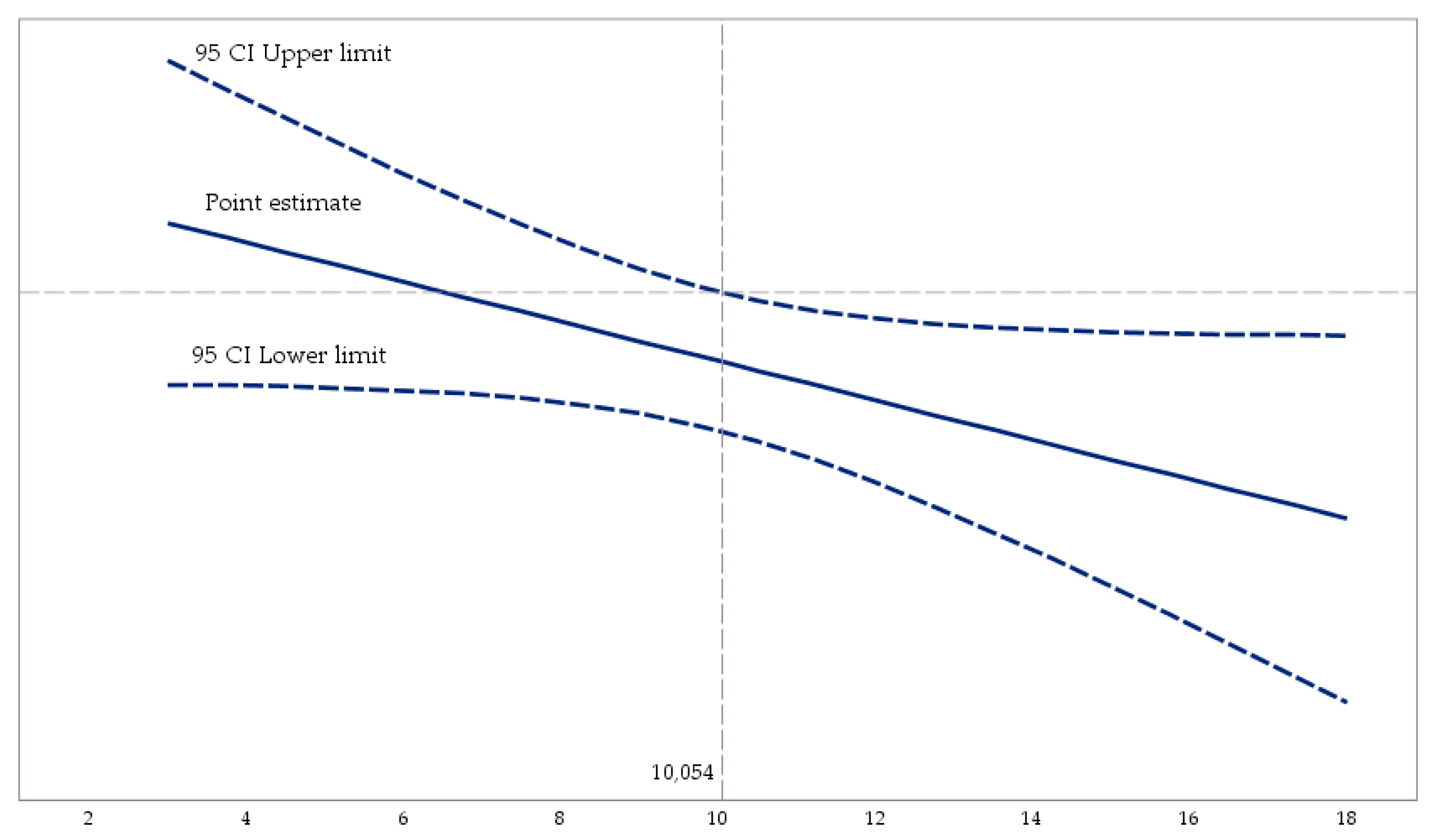

| Effect | Route | β | p | t | SE | LLCI | ULCI | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ECP on EE | a1i | 0.11 | 0.01 | 5.16 | 0.15 | 0.15 | 0.69 | ||

| WA on EE | a2i | 0.57 | 0.01 | 5.32 | 0.25 | 0.12 | 0.63 | ||

| ECP x WA on EE | a3i | -0.02 | 0.01 | -3.62 | 0.05 | -0.05 | -0.01 | ||

| Covariable S | 0.42 | 0.01 | 3.02 | 0.14 | 0.15 | 0.69 | |||

| Covariable G | 0.09 | 0.86 | 0.18 | 0.12 | -0.94 | 1.12 | |||

| Moderation WA (ECP -EE) | Low (8) | -0.03 | 0.48 | -0.71 | .003 | -0.09 | 0.04 | ||

| Med. (10) | -0.06 | 0.05 | -1.94 | .003 | -0.12 | 0.01 | |||

| High (13) | -0.11 | 0.01 | -2.65 | .004 | -0.19 | -0.03 | |||

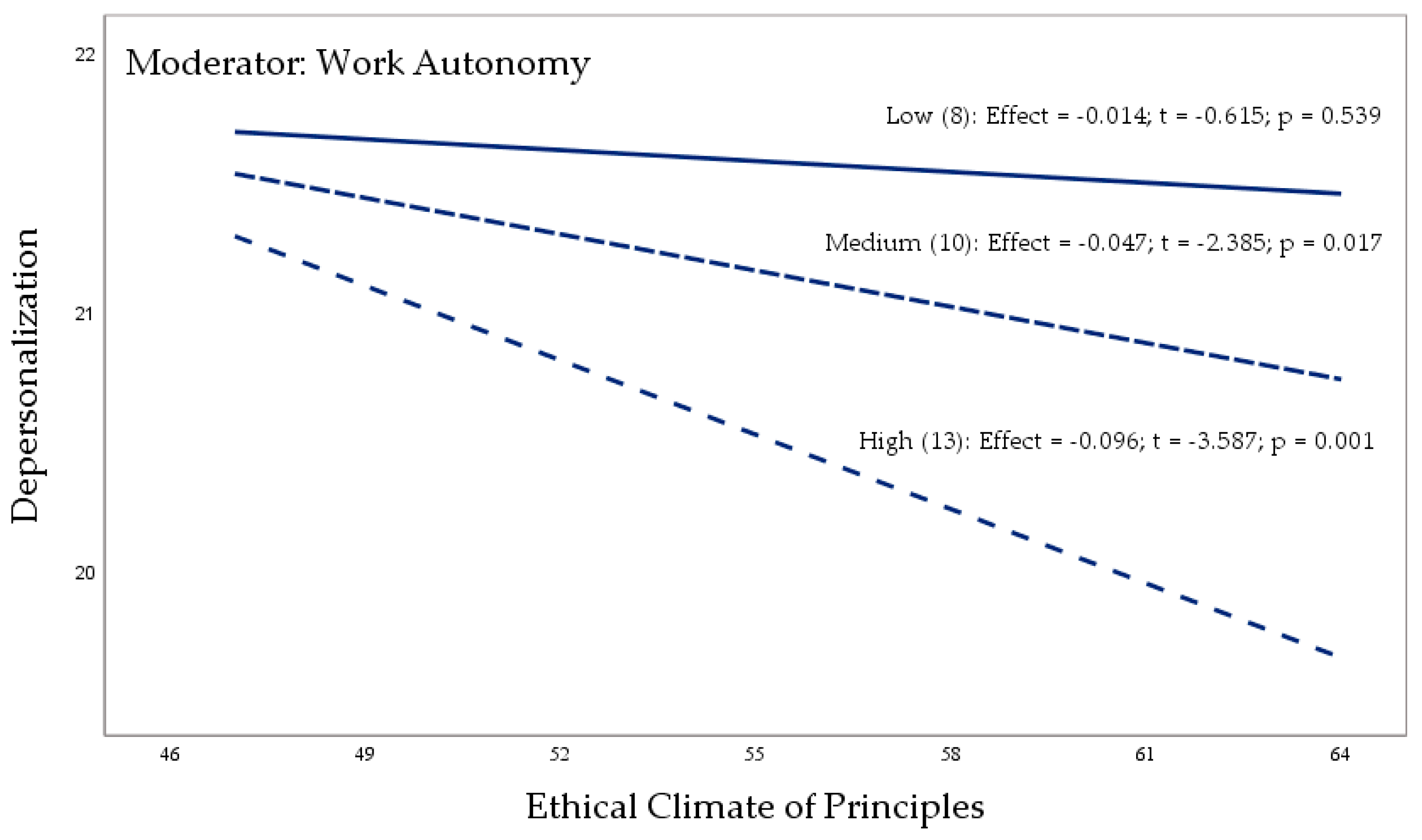

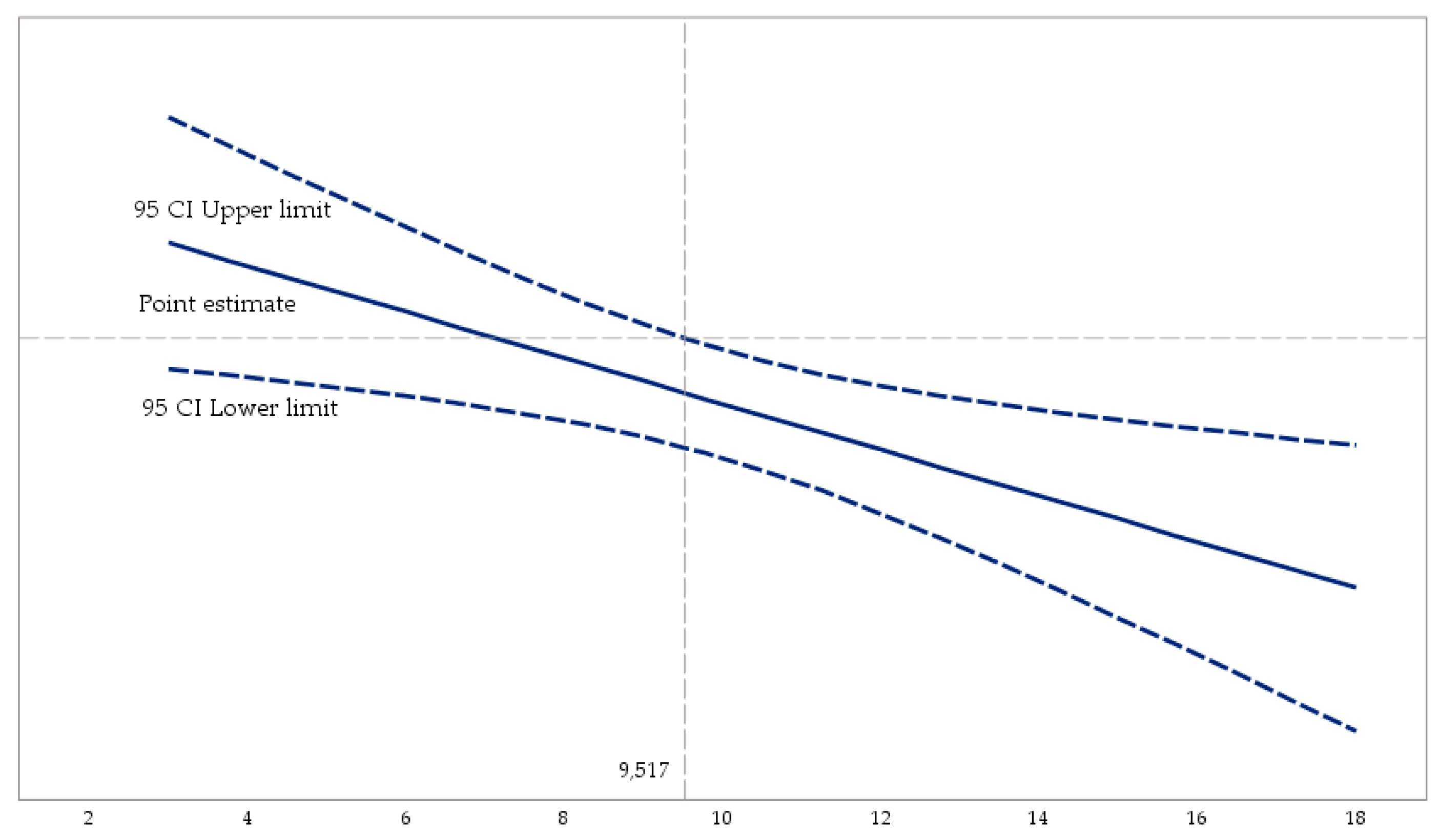

| Effect | Route | β | p | t | SE | LLCI | ULCI | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ECP on DE | a1i | 0.12 | 0.01 | 5.34 | 0.17 | 0.23 | 0.79 | ||

| WA on DE | a2i | 0.69 | 0.01 | 4.72 | 0.35 | 0.01 | 1.37 | ||

| ECP x WA on DE | a3i | -0.02 | 0.01 | -2.75 | 0.04 | -0.03 | -0.01 | ||

| Covariable S | 0.16 | 0.08 | 1.75 | 0.09 | -0.02 | 0.34 | |||

| Covariable G | 0.13 | 0.71 | 0.37 | 0.34 | -0.94 | 1.12 | |||

| Moderation WA (ECP - DE) | Low (8) | -0.01 | 0.54 | -0.61 | .002 | -0.06 | 0.03 | ||

| Med. (10) | -0.05 | 0.02 | -2.38 | .002 | -0.08 | -0.01 | |||

| High (13) | -0.10 | 0.01 | -3.59 | .003 | -0.15 | -0.04 | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).