Submitted:

06 September 2024

Posted:

09 September 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- Materials and structural design: Optimizing the materials of the acoustic resonator and internal components can enhance the durability and efficiency of the thermoacoustic cooler. This involves studies on composite materials, aerogels [17], thermal conductivity, mechanical resistance, and durability under operating conditions [12]–[14].

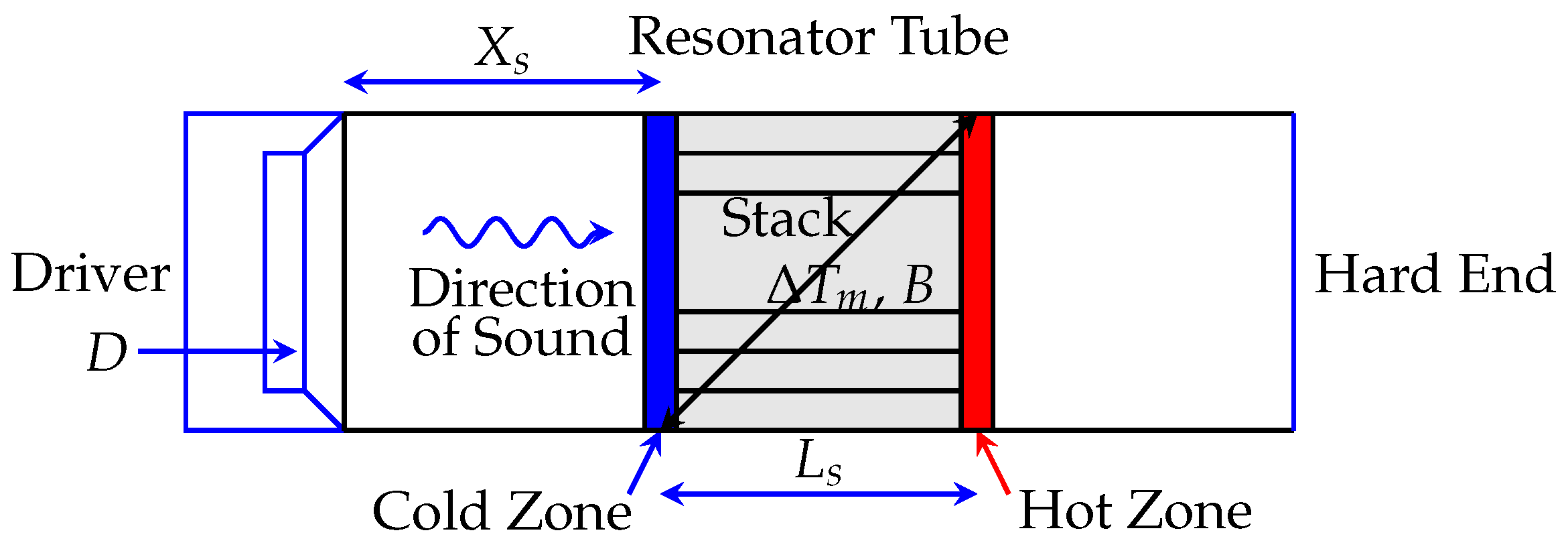

- Acoustics and vibrations: Since thermoacoustic refrigerators use sound waves to generate pressure changes and thus cooling, they can be studied from the perspective of acoustics and vibrations. This includes optimizing acoustic resonator geometry and system design to maximize acoustic-to-thermal energy transfer efficiency [9,10,15,16,20].

- Control and electronics: Electronic control of the thermoacoustic cycle can be crucial to optimize the stability and performance of the refrigerator. Control algorithms, temperature and pressure sensors, and the integration of electronic components can be studied to improve system accuracy and efficiency. [18]

2. Methods

2.1. COP Estimation for Thermoacoustic Devices

- is the angular frequency of the sound wave, is the design frequency.

- , K and are the viscosity, density, thermal conductivity, and isobaric specific heat of the gas respectively.

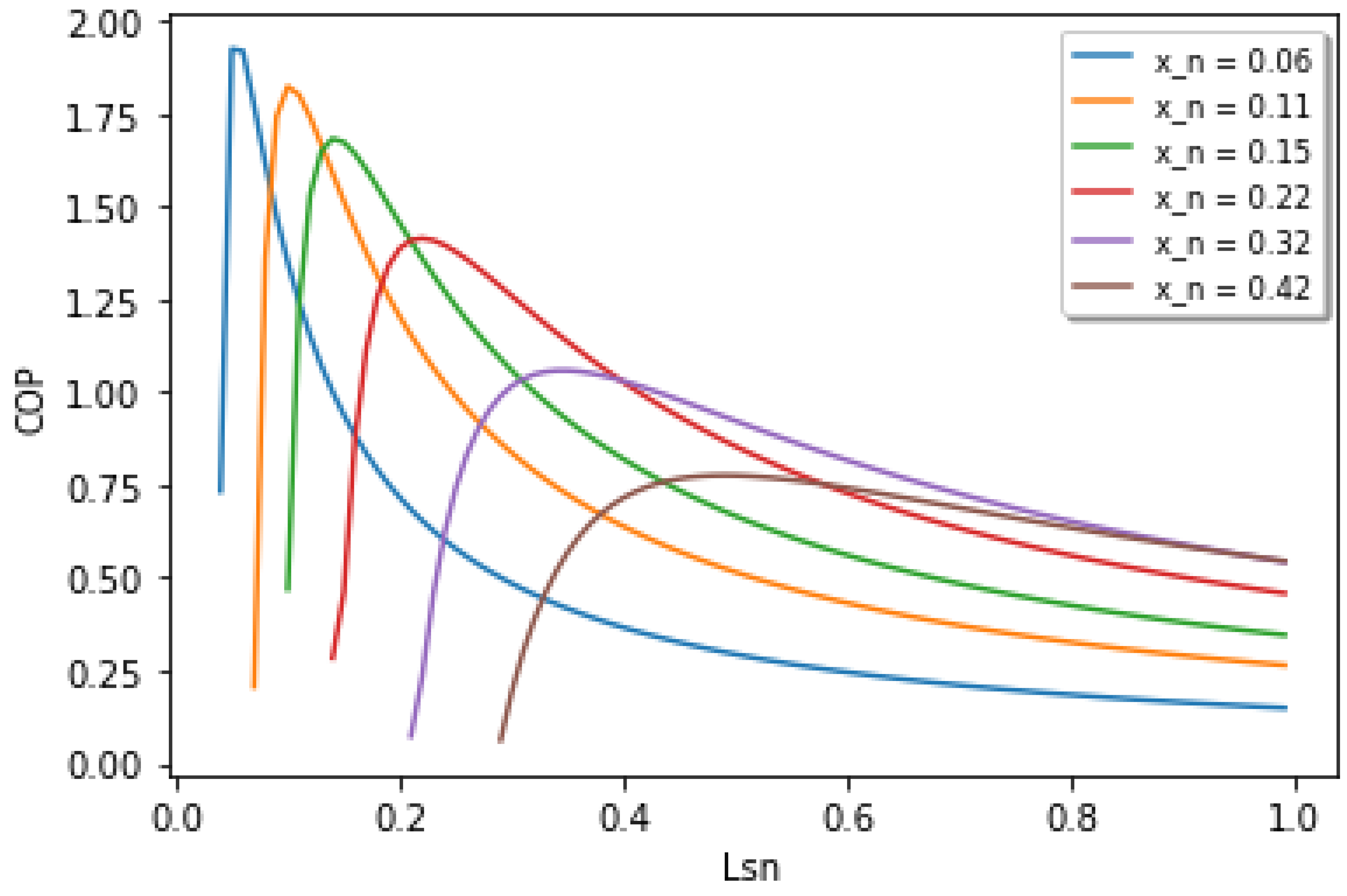

The dimensionless cooling power obtained from similitude and the acoustic power , where is the mean pressure; a is the sound velocity, and A is the cross-sectional area of the stack proposed by [19] are mentioned by Tijani et al. [10] that rewrites and in dimensionless form by using dimensionless parameters as:The equations which are important to thermoacoustics (continuity, motion, and heat transfer) are rewritten in dimensionless form, verifying that the list of dimensionless variables obtained from similitude is complete.

2.2. Design of Experiments (DOE)

- Determine the optimal condition within a specified range.

- Assess the contribution of individual factors and their interactions.

- Predict the response under optimal conditions.

- Planning stage

- Analysis stage

- Results stage

3. Results

- Establish the orthogonal design to determine the of a thermoacoustic cooling system, as outlined by Tijani [10].

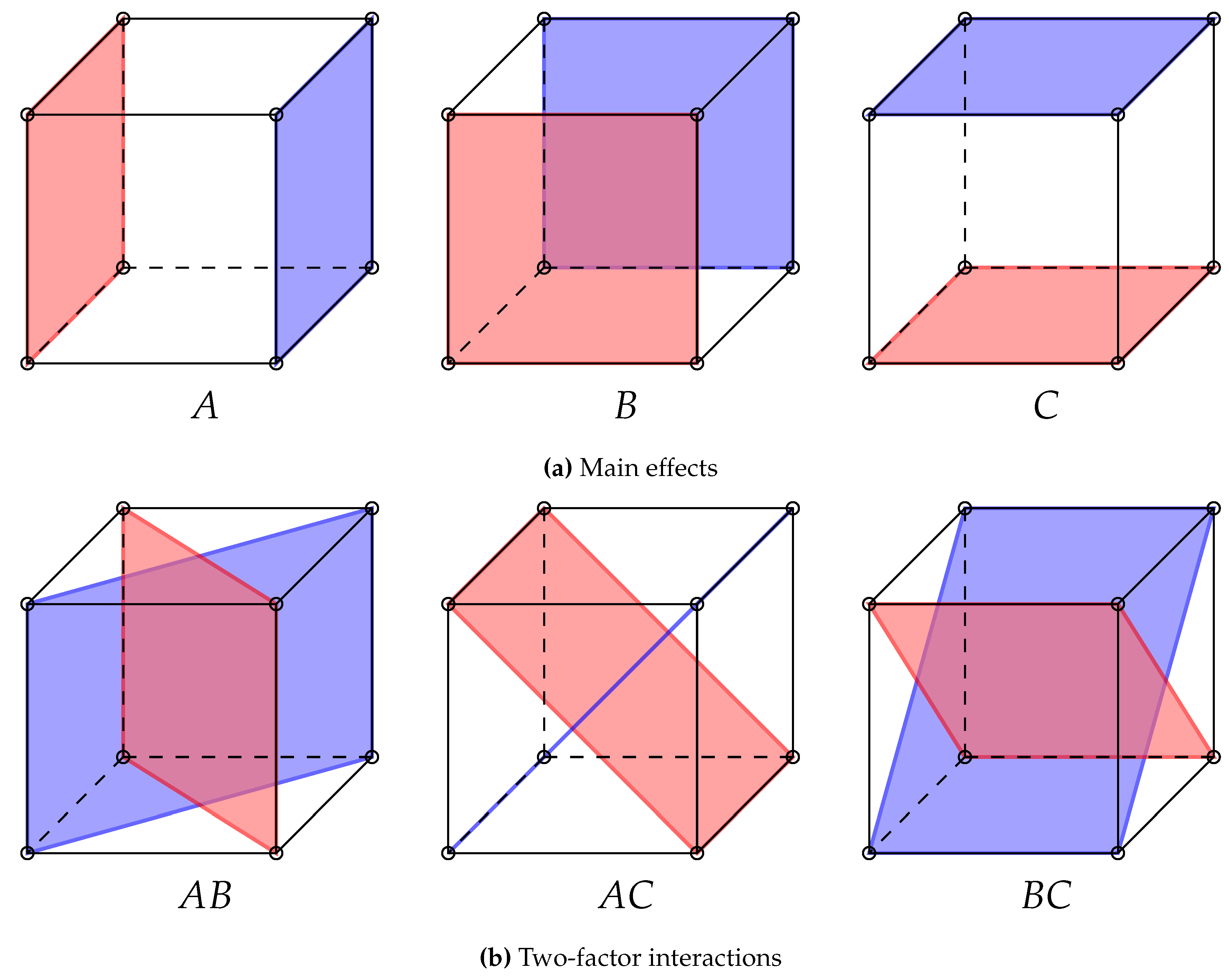

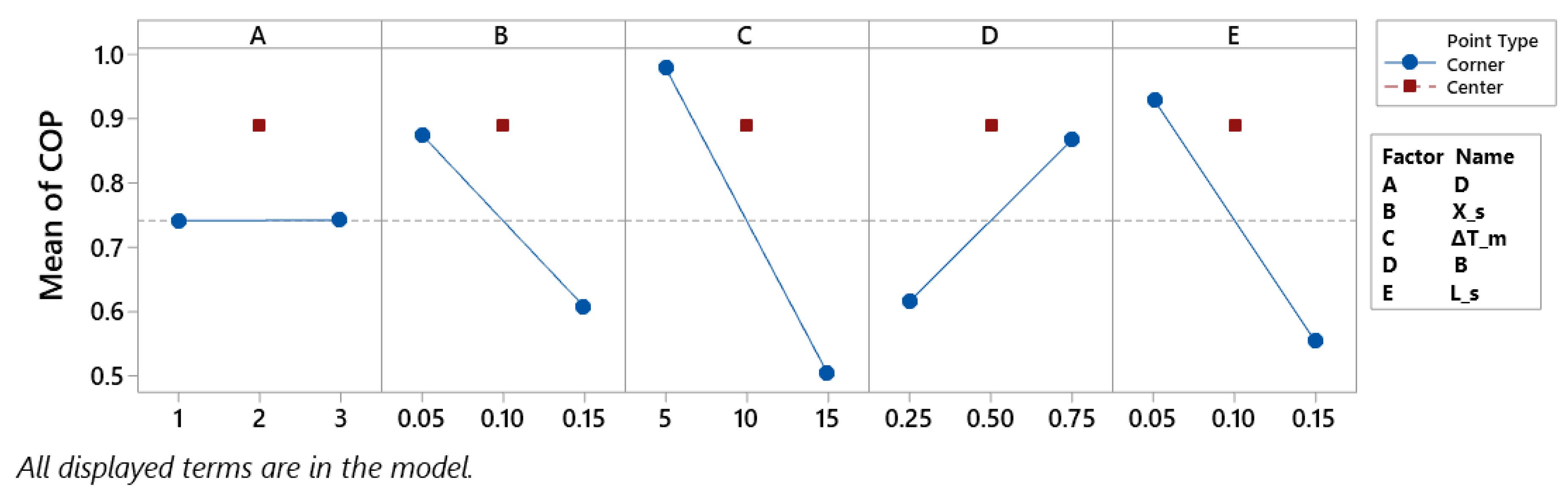

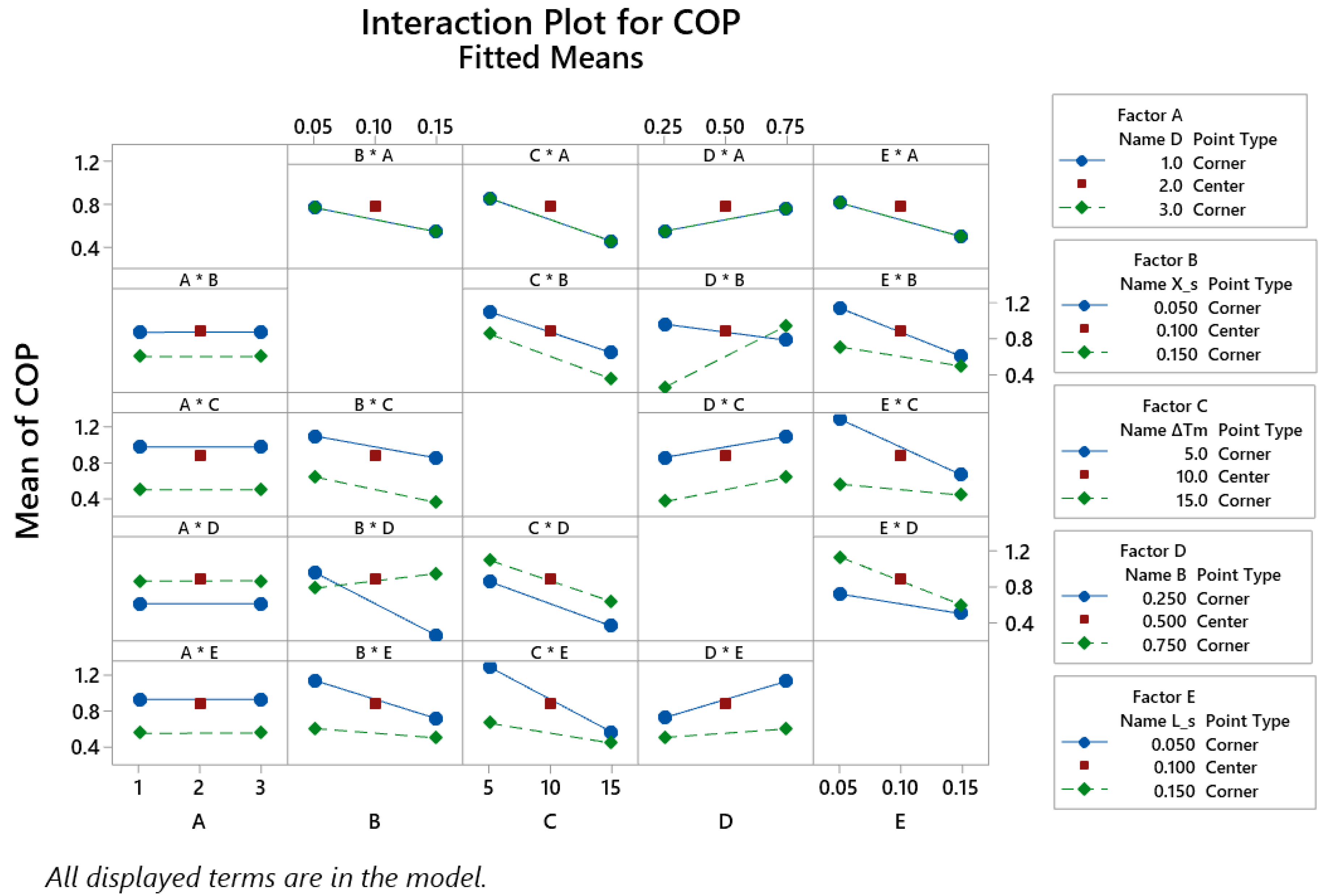

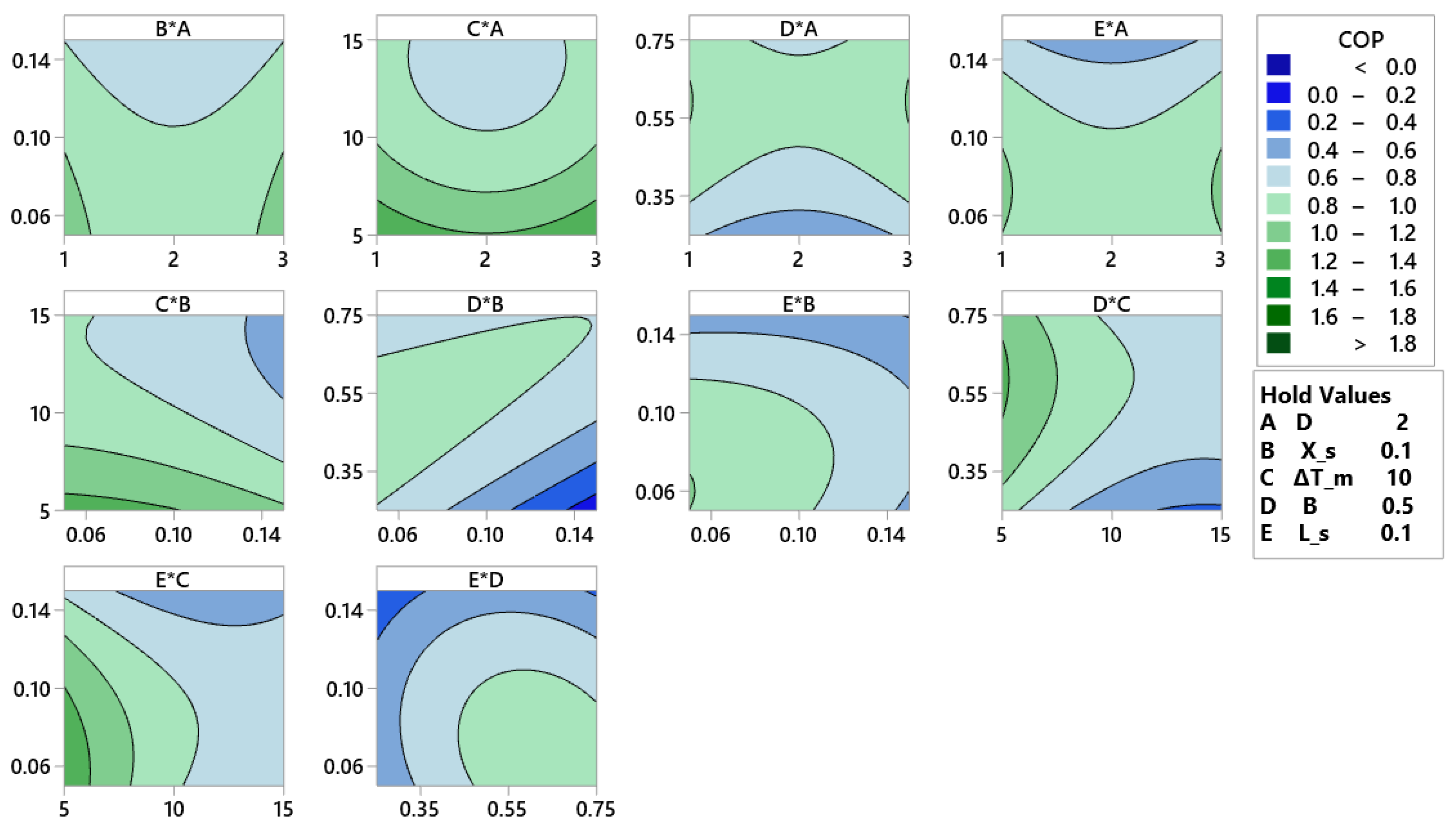

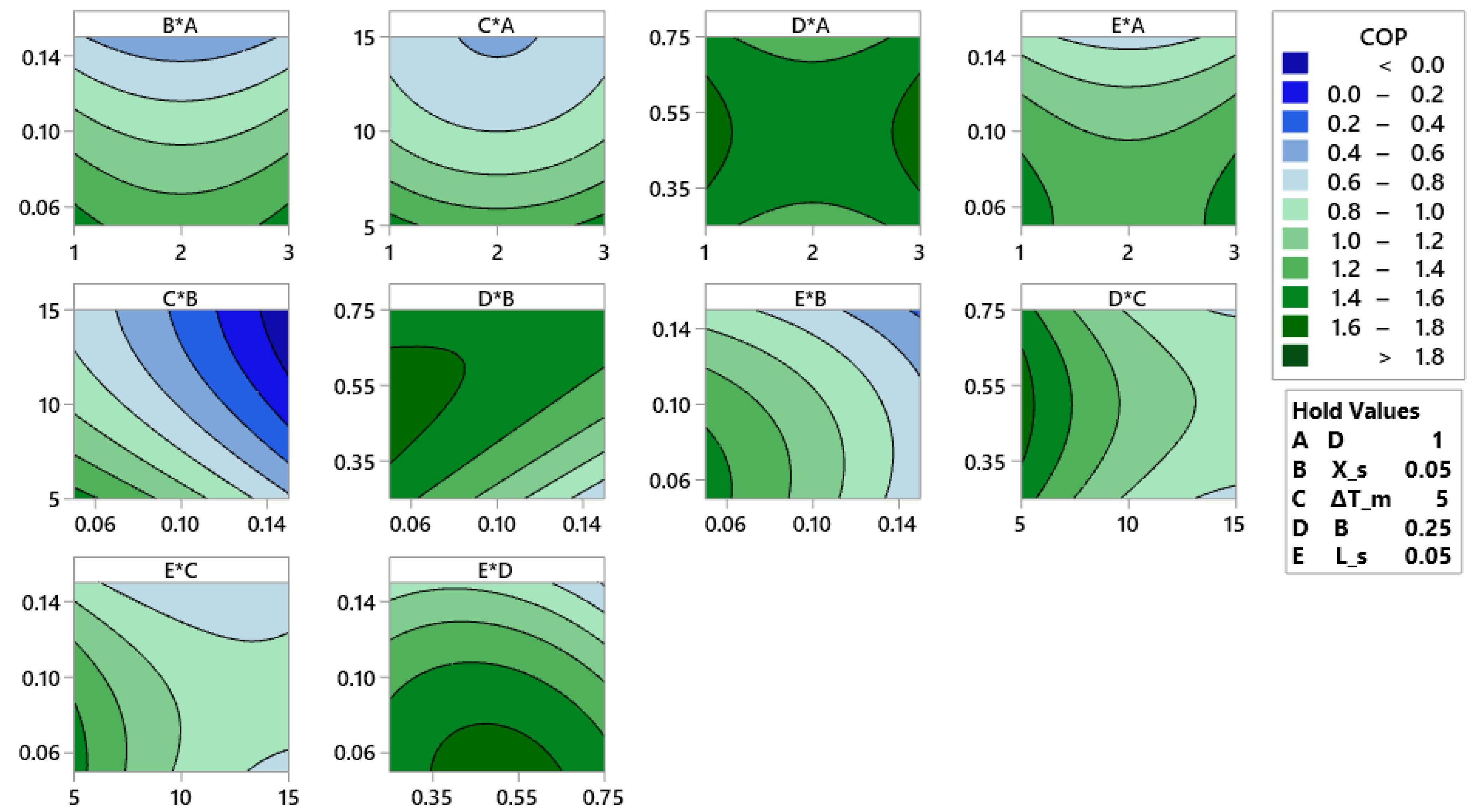

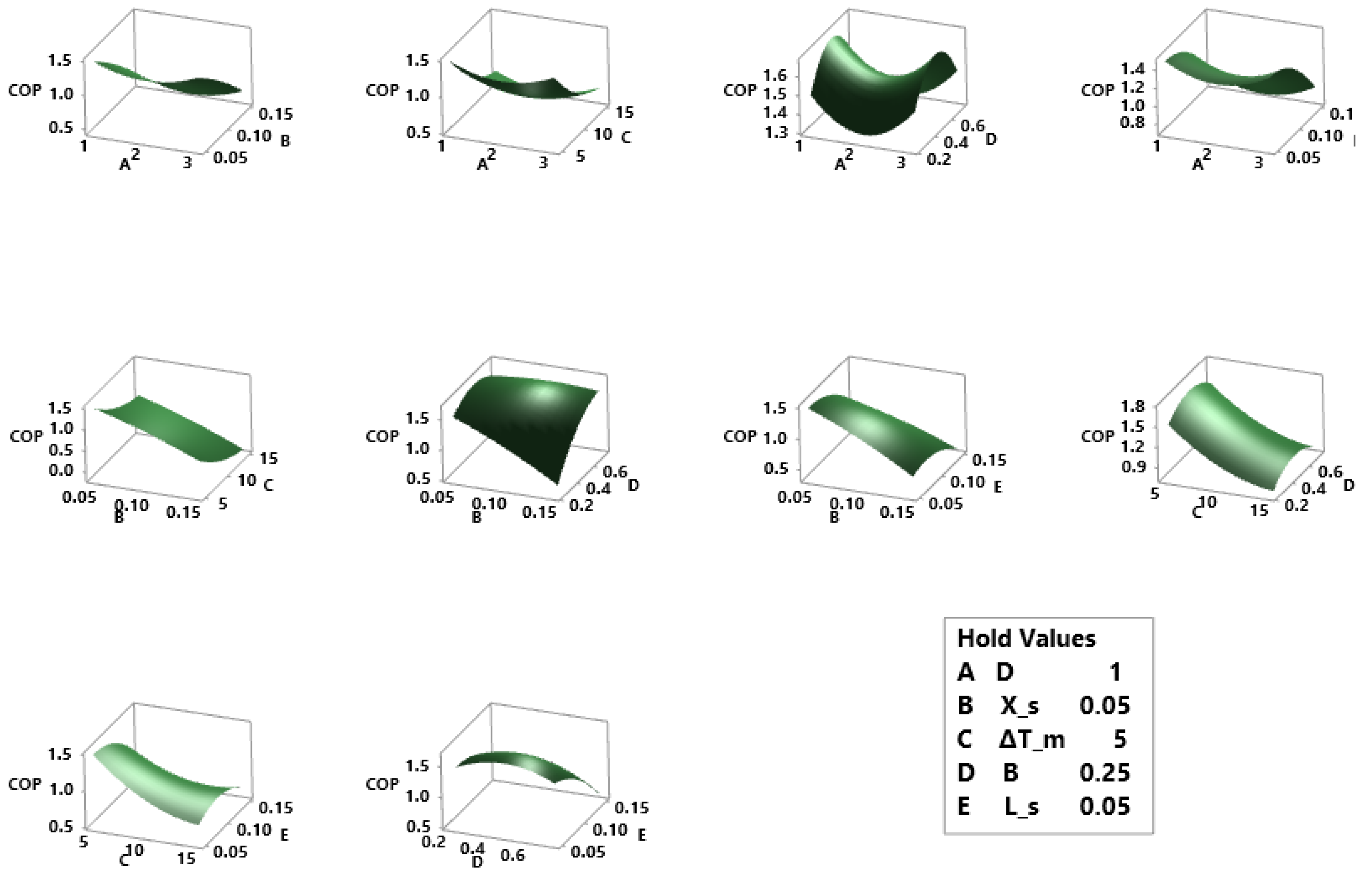

- Perform Pearson analysis: Assess main and interactions effects, Pareto chart, cube plots, contours, and surfaces plots.

- Conduct ANOVA analysis and develop transfer function.

3.1. COP’s Orthogonal Array

3.2. Pearson Analysis

3.3. COP’s ANOVA Analysis

[24]. For this model, the R-Sq value is 100.00%, accounting for up to 4-Way Interactions, reflecting a high degree of variability in the data based on the factors and their interactions as demostrated by the values obtained in the previous subsection.The influence of these interactions can be visualize using the coefficient of determination R-Sq, which represents the ratio of the variation explained by the model to the total variation. An R-Sq value close to one indicates a better-fitting model

3.3.1. Transfer Function of the ’s response

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MDPI | Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute |

| DOAJ | Directory of open access journals |

| COPR | Performance relative to Carnot |

| Notation | Definition | Units | Numerical |

| Value | |||

| Geometrical parameters | |||

| Resonator length | m | 0.7 | |

| S | Resonator section area | 7.854 × | |

| Stack length | m | 0.1 | |

| 2 ×l | Stack-plate thickness | m | 1.6 × |

| 2 × | Fluid layer thickness | m | 4.8 × |

| Thermo-physical properties of the working gas | |||

| Density | 1.2 | ||

| a | Adiabatic speed of sound | 344 | |

| K | Thermal conductivity | 2.55 × | |

| Specific heat coefficient | 0.244 | ||

| per unit of mass | |||

| Shear viscosity coefficient | 1.82 × | ||

| Operational parameters | |||

| Average pressure | 1.013 × | ||

| Average Temperature | °K | 298 | |

| f | Frequency | Hz | 122.85 |

References

- Peng, Y; Feng, H. and Mao, X. Optimization of Standing-Wave Thermoacoustic Refrigerator Stack Using Genetic Algorithm International, Journal of Refrigeration 2018, 92, pp. 246–255. [CrossRef]

- Minner, B. L.; Braun, J. E. and Mongeau, L. Optimizing the Design of a Thermoacoustic Refrigerator International Refrigeration and Air Conditioning Conference. 1996, Paper 343 pp. 315–322.

- Babaei, H.; Siddiqui, K. Design and optimization of thermoacoustic devices, Energy Conversion and Management 2008 Volume 49, Issue 12, pp. 3585-3598, ISSN 0196-8904. [CrossRef]

- Wetzel, M. and Herman, C. Design optimization of thermoacoustic refrigerators International Journal of Refrigeration 1997 Volume 20, Issue 1, pp. 3-21, ISSN 0140-7007. [CrossRef]

- Poignand, G.; Lihoreau, B.; Lotton, P.; Gaviot, E.; Bruneau, M.; Gusev, V; Optimal acoustic fields in compact thermoacoustic refrigerators, Applied Acoustics 2007 Volume 68, Issue 6, pp. 642-659, ISSN 0003-682X. [CrossRef]

- Tartibu L.K., Sun B., Kaunda M.A.E., Optimal Design of A Standing Wave Thermoacoustic Refrigerator Using GAMS Procedia Computer Science, 2015 Volume 62, pp. 611-618, ISSN 1877-0509. [CrossRef]

- Ong, J.Y.; King, Y.J.; Saw, L.H. and Theng, K.K. Optimization of the Design Parameter for Standing Wave Thermoacoustic Refrigerator using Genetic Algorithm IOP Conf. Ser.: Earth Environ. Sci 2019 268 012021. [CrossRef]

- Wu, F.; Wu, C.; Guo, F.; Li, Q.; Chen, L. Optimization of a Thermoacoustic Engine with a Complex Heat Transfer Exponent. Entropy 2003, 5, 444-451. [CrossRef]

- Tijani, M.E.H. Loudspeaker-driven thermo-acoustic refrigeration, PhD. TUE. Netherlands, 10th September 2001; ISBN 90-386-1829-8.

- Tijani M.E.H., Zeegers J.C.H., de Waele, A.T.A.M. Design of thermoacoustic refrigerators Cryogenics 2002 Volume 42, Issue 1, pp. 49-57, ISSN 0011-2275.

- Channarong, W. and Kriengkrai, A. The impact of the resonance tube on performance of a thermoacoustic stack Frontiers in Heat and Mass Transfer 2012 2(4), pp. 1-8. [CrossRef]

- Doutres, O.; Salissou, Y.; Atalla, N. and Panneton R. Evaluation of the acoustic and non-acoustic properties of sound absorbing materials using a three-microphone impedance tube Applied Acoustics, 2010 71(6), pp. 506-509. [CrossRef]

- Kidner, M.R.F. and Hansen, C.H. A comparison and review of theories of the acoustics of porous materials International Journal of Acoustics and Vibration 2008 13(3), pp. 112-119.

- R.A. Scott. The propagation of sound between walls of porous materials Proceedings of the Physical Society, 1946 58 pp. 358-368. [CrossRef]

- Los Alamos National Laboratories. DeltaEC: Design environment for low-amplitude thermoacoustic energy conversion. Software, http://www.lanl.gov/thermoacoustics/DeltaEC.html, 20 August 2024. version 6.3b11 (Windows, 18-Feb-12).

- Desai, A.B., Desai, K.P., Naik, H.B. and Atrey, M.D. Optimization of thermoacoustic engine driven thermoacoustic refrigerator using response surface methodology IOP Conf. Ser.: Mater. Sci. Eng 2017 171 012132. [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Rahman, E.; Kwon, Y.; Symko, O.G.; Investigation of stack materials for miniature thermoacoustic engines J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2001, 110 5 Supplement: 2677. [CrossRef]

- Patronis, E. T. Jr. The Electronics Handbook, 2nd ed. Edited by Whitaker J.C, Publisher: CRC Press, Taylor and Francis Group, Boca Raton, 2005, chapter 1.3 pp. 20-30. ISBN 9781315220703.

- Olson, J.R.; Swift, G.W. Similitude in thermoacoustic J Acoust. Soc. Am. 1994 95:3 pp.1405–1412. [CrossRef]

- Howard, C.; Cazzolato, B. Acoustic Analyses Using MATLAB and ANSYS Software. The University of Adelaide. Dataset, 1st ed., Publisher: CRC Press, Boca Raton, 2014, ISBN 9780429069642.

- Montgomery, D. C., Design and analysis of experiments, 10th ed. Publisher: John Wiley & Sons, USA. 2019, ISBN: 978-1-119-49244-3.

- Minitab 19 Statistical Software, 2010, Computer software, State Collage, PA:Minitab, Inc. www.minitab.com.

- Python 3.6 Software, https://docs.python.org/3/license.html 2001-2024, 20 August 2024, Python Software Foundation License Version 2.

- Peredo Fuentes, H. Model reduction of components and assemblies made of composite materials as part of complex technical systems to simulate the overall dynamic behaviour PhD. TU-Berlin. Germany, 30th December 2017. [CrossRef]

- Piccolo, A. Study of Standing-Wave Thermoacoustic Electricity Generators for Low-Power Applications. Appl. Sci. 2018, 8, 287. [CrossRef]

| 1 | The main effect of a factor can be thought of as the difference between the average response at the low level minus the average response at the high level [22]. |

| 2 | The denotes the measure of central tendency, representing the mean or average of all population values [22]. |

| 3 | The indicates the measure of dispersion or variability. Smaller values suggest that the population are closely clustered around the mean [22]. |

| 4 | Aliasing refers to confounding effects in the design that makes it imposible to estimate certain effects separately [22]. |

| 5 | The Pearson correlation provides a range of values from to , where a value of 0 indicates no linear relationship between the variables. A correlation of represents a perfect negative linear relationship and indicates a perfect positive linear relationship [22]. |

| 6 | A Pareto Chart of the Standardized Effects visually displays the magnitude of the effects of different factors or variables on a response variable in a systematic manner. It combines the principles of Pareto analysis (where factors are ranked by their impact) with statistical methods for analyzing experimental results [22]. |

| Parameters | Definitions |

|---|---|

| Operational | Drive ratio D= |

| parameters | Dimensionless cooling power |

| Dimensionless acoustic power | |

| Dimensionless temperature difference | |

| Gas | Prandtl number =( |

| parameters | Dimensionless thermal penetration depth |

| Dimensionless viscous penetration depth | |

| Ratio of isobaric to isochoric specific heats | |

| Geometrical | Dimensionless stack length |

| parameters | Dimensionless stack position |

| Blockage Ratio |

| Factor | Name | Level | Units |

| Low - High | |||

| A | Drive Ratio (D) | - + | N/A |

| B | Dimensionless Stack Position () | - + | N/A |

| C | Dimensionless Temperature () | - + | N/A |

| D | Blocking Ratio (B) | - + | N/A |

| E | Dimensionless regenerator length () | - + | N/A |

| Factors | |||||||||

| A | B | C | D | E | AB | AC | BC | ABC | |

| Run | |||||||||

| 1 | - | - | - | - | - | + | + | + | - |

| 2 | + | - | - | - | - | - | - | + | + |

| 3 | - | + | - | - | - | - | + | - | + |

| 4 | + | + | - | - | - | + | - | - | - |

| 5 | - | - | + | - | - | + | - | - | + |

| 6 | + | - | + | - | - | - | + | - | - |

| 7 | - | + | + | - | - | - | - | + | - |

| 8 | + | + | + | - | - | + | + | + | + |

| 9 | - | - | - | + | - | + | + | + | - |

| 10 | + | - | - | + | - | - | - | + | + |

| 11 | - | + | - | + | - | - | + | - | + |

| 12 | + | + | - | + | - | + | - | - | - |

| 13 | + | - | + | + | - | + | - | - | + |

| 14 | - | - | + | + | - | - | + | - | - |

| 15 | + | + | + | + | - | - | - | + | - |

| 16 | - | + | + | + | - | + | + | + | + |

| 17 | - | - | - | - | + | + | + | + | - |

| 18 | + | - | - | - | + | - | - | + | + |

| 19 | - | + | - | - | + | - | + | - | + |

| 20 | + | + | - | - | + | + | - | - | - |

| 21 | - | - | + | - | + | + | - | - | + |

| 22 | + | - | + | - | + | - | + | - | - |

| 23 | - | + | + | - | + | - | - | + | - |

| 24 | + | + | + | - | + | + | + | + | + |

| 25 | - | - | - | + | + | + | + | + | - |

| 26 | + | - | - | + | + | - | - | + | + |

| 27 | - | + | - | + | + | - | + | - | + |

| 28 | + | + | - | + | + | + | - | - | - |

| 29 | + | - | + | + | + | + | - | - | + |

| 30 | - | - | + | + | + | - | + | - | - |

| 31 | + | + | + | + | + | - | - | + | - |

| 32 | - | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

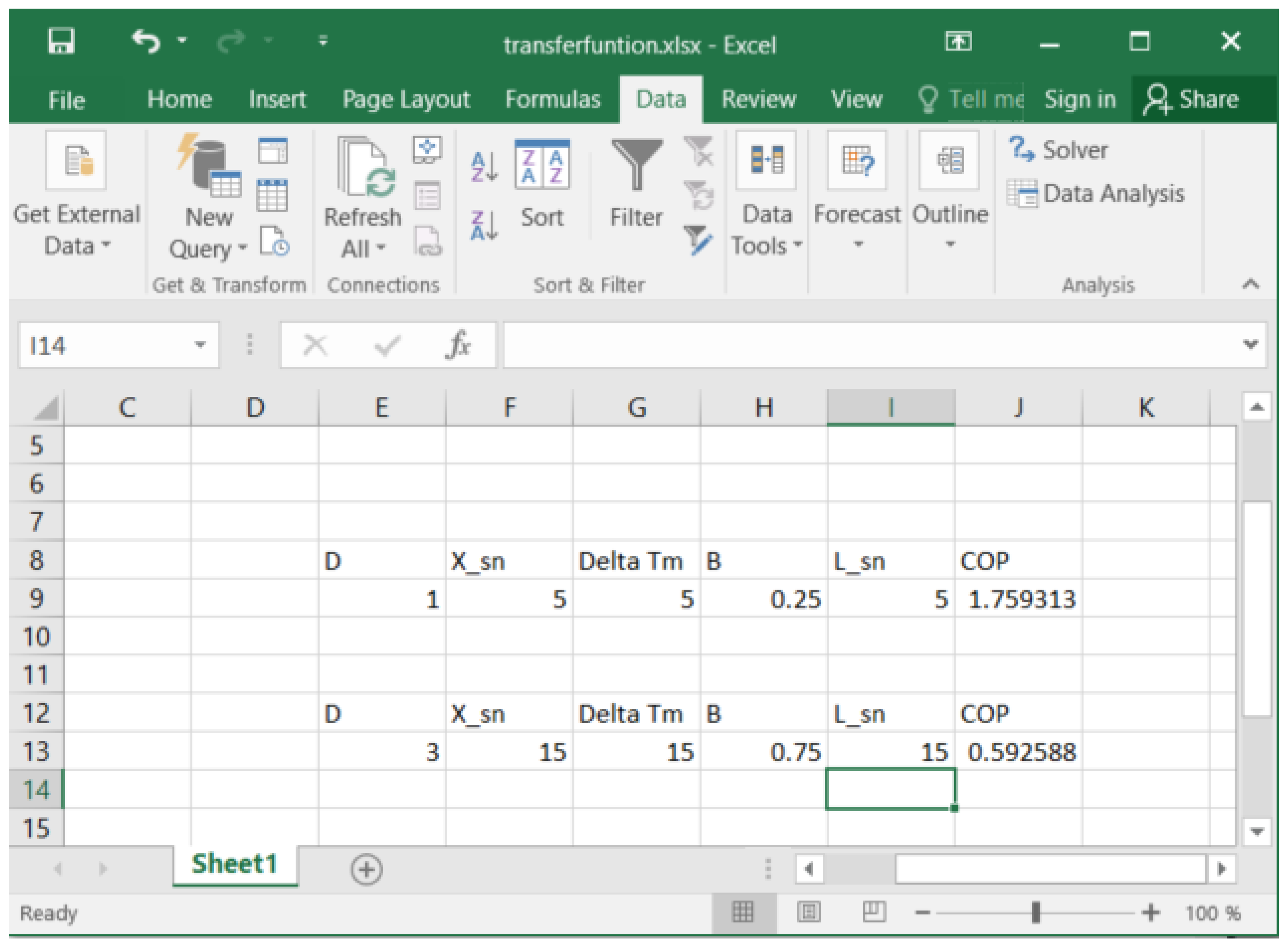

| Factor | Name | Level | Units |

| Low - High | |||

| A | Drive Ratio (D) | 1 3 | % |

| B | Stack Position () | 0.05 0.15 | m |

| C | Temperature () | 5 15 | °K |

| D | Blocking Ratio (B) | 0.25 0.75 | N/A |

| E | Regenerator length () | 0.05 0.15 | m |

| Factors | A | B | C | D | E | |

| Name | D | B | ||||

| Units | % | m | °K | N/A | m | |

| Run | ||||||

| 15 | 1 | 0.15 | 15 | 0.75 | 0.05 | 0.59 |

| 30 | 3 | 0.05 | 15 | 0.75 | 0.15 | 0.45 |

| 25 | 1 | 0.05 | 5 | 0.75 | 0.15 | 0.48 |

| 10 | 3 | 0.05 | 5 | 0.75 | 0.05 | 1.28 |

| 16 | 3 | 0.15 | 15 | 0.75 | 0.05 | 0.59 |

| 27 | 1 | 0.15 | 5 | 0.75 | 0.15 | 0.88 |

| 3 | 1 | 0.15 | 5 | 0.25 | 0.05 | 0.40 |

| 21 | 1 | 0.05 | 15 | 0.25 | 0.15 | 0.60 |

| 19 | 1 | 0.15 | 5 | 0.25 | 0.15 | 0.40 |

| 1 | 1 | 0.05 | 5 | 0.25 | 0.05 | 1.76 |

| 11 | 1 | 0.15 | 5 | 0.75 | 0.05 | 1.74 |

| 8 | 3 | 0.15 | 15 | 0.25 | 0.05 | 0.13 |

| 26 | 3 | 0.05 | 5 | 0.75 | 0.15 | 0.49 |

| 12 | 3 | 0.15 | 5 | 0.75 | 0.05 | 1.74 |

| 13 | 1 | 0.05 | 15 | 0.75 | 0.05 | 0.93 |

| 23 | 1 | 0.15 | 15 | 0.25 | 0.15 | 0.13 |

| 29 | 1 | 0.05 | 15 | 0.75 | 0.15 | 0.45 |

| 22 | 3 | 0.05 | 15 | 0.25 | 0.15 | 0.60 |

| 28 | 3 | 0.15 | 5 | 0.75 | 0.15 | 0.89 |

| 17 | 1 | 0.05 | 5 | 0.25 | 0.15 | 0.89 |

| 4 | 3 | 0.15 | 5 | 0.25 | 0.05 | 0.40 |

| 18 | 3 | 0.05 | 5 | 0.25 | 0.15 | 0.89 |

| 14 | 3 | 0.05 | 15 | 0.75 | 0.05 | 0.93 |

| 2 | 3 | 0.05 | 5 | 0.25 | 0.05 | 1.76 |

| 6 | 3 | 0.05 | 15 | 0.25 | 0.05 | 0.61 |

| 5 | 1 | 0.05 | 15 | 0.25 | 0.05 | 0.61 |

| 32 | 3 | 0.15 | 15 | 0.75 | 0.15 | 0.58 |

| 7 | 1 | 0.15 | 15 | 0.25 | 0.05 | 0.13 |

| 33 | 2 | 0.10 | 10 | 0.50 | 0.10 | 0.89 |

| 9 | 1 | 0.05 | 5 | 0.75 | 0.05 | 1.28 |

| 20 | 3 | 0.15 | 5 | 0.25 | 0.15 | 0.40 |

| 31 | 1 | 0.15 | 15 | 0.75 | 0.15 | 0.59 |

| 24 | 3 | 0.15 | 15 | 0.25 | 0.15 | 0.13 |

| Source | DF | Seq SS | Contribution | Adj SS | Adj MS | F-Value | P-Value | Coeff. |

| Model | 31 | 7.25978 | 100.00% | 7.25978 | 0.23419 | 74939.71 | 0.003 | 5.5922 |

| Linear | 5 | 4.04327 | 55.69% | 4.04327 | 0.80865 | 258769.00 | 0.001 | |

| D | 1 | 0.00000 | 0.00% | 0.00000 | 0.00000 | 1.00 | 0.500 | 0.00656 |

| 1 | 0.57513 | 7.92% | 0.57513 | 0.57513 | 184041.00 | 0.001 | 0.41781 | |

| 1 | 1.81928 | 25.06% | 1.81928 | 1.81928 | 582169.00 | 0.001 | 0.33544 | |

| B | 1 | 0.51258 | 7.06% | 0.51258 | 0.51258 | 164025.00 | 0.002 | 5.5487 |

| 1 | 1.13628 | 15.65% | 1.13628 | 1.13628 | 363609.00 | 0.001 | 0.25144 | |

| 2-Way Interactions | 10 | 2.41728 | 33.30% | 2.41728 | 0.24173 | 77353.00 | 0.003 | |

| D* | 1 | 0.00000 | 0.00% | 0.00000 | 0.00000 | 1.00 | 0.500 | 0.000438 |

| D* | 1 | 0.00003 | 0.00% | 0.00003 | 0.00003 | 9.00 | 0.205 | 0.000563 |

| 1 | 0.00000 | 0.00% | 0.00000 | 0.00000 | 1.00 | 0.500 | 0.01625 | |

| 1 | 0.00000 | 0.00% | 0.00000 | 0.00000 | 1.00 | 0.500 | 0.000813 | |

| * | 1 | 0.00340 | 0.05% | 0.00340 | 0.00340 | 1089.00 | 0.019 | 0.024912 |

| *B | 1 | 1.49213 | 20.55% | 1.49213 | 1.49213 | 477481.00 | 0.001 | 0.69325 |

| * | 1 | 0.20963 | 2.89% | 0.20963 | 0.20963 | 67081.00 | 0.002 | 0.021062 |

| *B | 1 | 0.00263 | 0.04% | 0.00263 | 0.00263 | 841.00 | 0.022 | 0.44975 |

| * | 1 | 0.51258 | 7.06% | 0.51258 | 0.51258 | 164025.00 | 0.002 | 0.018988 |

| 1 | 0.19688 | 2.71% | 0.19688 | 0.19688 | 63001.00 | 0.003 | 0.22775 | |

| 3-Way Interactions | 10 | 0.53458 | 7.36% | 0.53458 | 0.05346 | 17106.60 | 0.006 | |

| D** | 1 | 0.00000 | 0.00% | 0.00000 | 0.00000 | 1.00 | 0.500 | 0.000038 |

| D**B | 1 | 0.00000 | 0.00% | 0.00000 | 0.00000 | 1.00 | 0.500 | 0.000750 |

| D** | 1 | 0.00000 | 0.00% | 0.00000 | 0.00000 | 1.00 | 0.500 | 0.000038 |

| D**B | 1 | 0.00003 | 0.00% | 0.00003 | 0.00003 | 9.00 | 0.205 | 0.001250 |

| D** | 1 | 0.00003 | 0.00% | 0.00003 | 0.00003 | 9.00 | 0.205 | 0.000062 |

| D*B* | 1 | 0.00000 | 0.00% | 0.00000 | 0.00000 | 1.00 | 0.500 | 0.002250 |

| **B | 1 | 0.48265 | 6.65% | 0.48265 | 0.48265 | 154449.00 | 0.002 | 0.047450 |

| **Ls | 1 | 0.01320 | 0.18% | 0.01320 | 0.01320 | 4225.00 | 0.010 | 0.001553 |

| *B* | 1 | 0.02703 | 0.37% | 0.02703 | 0.02703 | 8649.00 | 0.007 | 0.032450 |

| *B* | 1 | 0.01163 | 0.16% | 0.01163 | 0.01163 | 3721.00 | 0.010 | 0.024550 |

| 4-Way Interactions | 5 | 0.24329 | 3.35% | 0.24329 | 0.04866 | 15570.60 | 0.006 | |

| D***B | 1 | 0.00000 | 0.00% | 0.00000 | 0.00000 | 1.00 | 0.500 | 0.00005 |

| D*** | 1 | 0.00000 | 0.00% | 0.00000 | 0.00000 | 1.00 | 0.500 | 0.000002 |

| D**B* | 1 | 0.00000 | 0.00% | 0.00000 | 0.00000 | 1.00 | 0.500 | 0.000050 |

| D**B* | 1 | 0.00003 | 0.00% | 0.00003 | 0.00003 | 9.00 | 0.205 | 0.000150 |

| X**B* | 1 | 0.24325 | 3.35% | 0.24325 | 0.24325 | 77841.00 | 0.002 | 0.002790 |

| Curvature | 1 | 0.02137 | 0.29% | 0.02137 | 0.02137 | 6837.12 | 0.008 | 0.14844 |

| Error | 1 | 0.00000 | 0.00% | 0.00000 | 0.00000 | |||

| Total | 32 | 7.25979 | 100.00% |

- Note: DF, degree of freedom, Seq SS, Sequential SUM of squares,

- Adj SS, Adjust sum of squares, Adj MS, Adjust mean of squares,

- F=F-value, P=P-value, Coeff= Uncoded Coefficients

- S=0.0017678, R-Sq= 100.00 %, R-Sq(Adj) = 100.00%

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).