1. Introduction

The World Health Organization (WHO) defines multimorbidity as "the presence of two or more health conditions" [

1]. This phenomenon presents a growing global challenge with substantial effects on individuals, families, healthcare systems, and society. In socioeconomically disadvantaged communities, multimorbidity occurs a decade earlier and is associated with premature death, poorer function and quality of life, depression, polypharmacy, and increased demand for medical care [

2]. It is estimated that caring for patients with multimorbidity accounts for 78% of healthcare expenditures in the US [

3]. A study of Medicare beneficiaries revealed that 64% of individuals had two or more conditions and 24% had four or more health conditions [

4]. Regarding its impact on cancer, multimorbidity delays diagnosis, reduces the likelihood of implementing curative treatment, results in a higher rate of complications, and decreases quality of life and survival [

5].

Genitourinary cancer (GUC), which includes prostate, kidney, bladder, and testicular neoplasms, is common, with detection increasing with age [

6]. By 2020, prostate cancer was the second most common cancer worldwide (307 per 100,000), and bladder cancer was the thirteenth (56 per 100,000) [

7]. In Chile, prostate cancer is the most frequent malignant neoplasm in men (23.9%). Kidney cancer ranked seventh, while testicular cancer was the sixth most diagnosed cancer in men [

8]. Additionally, GUC carries a high financial burden. For example, the global cost of bladder cancer in the US was

$5 billion in 2020 [

9]. Thus, it is crucial to understand the extent of multimorbidity in GUC and its clinical and financial impacts.

The objective of this study was to characterize multimorbidity and determine the most clinically and financially impactful combinations of comorbidities in patients with GUC in Chile.

2. Material and Methods

This was a descriptive, retrospective population-based study of patients with GUC, evaluating comorbidities and their respective costs for the National Health Fund (FONASA) in Chile. FONASA is the public agency managing state health funds for its beneficiary population, which represents 79.6% of the population (87.8% in individuals >65 years) (12). The diagnosis-related groups (DRG) databases include all hospital events in the country's 68 public health centers of medium and high complexity. This information includes the data through which FONASA estimates the cost and payment mechanism for each hospital event for the public health system's population. The DRG-based payment mechanism accounts for 70% of FONASA's total expenditure [

10,

11].

Official FONASA DRG databases for the years 2019-2021, encompassing 4,028,597 hospitalization events, were used. The DRG databases include hospitalizations of the population exclusively belonging to the public health system. All patients with bladder cancer (BC) (ICD-10 C67), prostate cancer (PC) (ICD-10 C61), testicular cancer (TC) (ICD-10 C62), and kidney cancer (KC) (ICD-10 C64) were included, corresponding to 25,358 individuals with GUC. The most prevalent comorbidities were analyzed. The cost associated with FONASA was calculated by multiplying the base price of each hospital by the DRG weight for each hospitalization [

10,

11]. The variable "type of admission" was used to define records corresponding to emergency or elective admissions. The variable “Severity” was used to determine the severity of the hospitalization event, and is determined by how deviate of the normal course of the disease was [

10,

11]. The information used corresponded to official secondary data sources. Individuals' identities are encrypted with a code (ID), thus not violating the requirements outlined by Law 19.628 on the protection of private life and the use of sensitive data in Chile.

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS v29.0.0. Continuous variables were analyzed using Mann-Whitney U tests due to their non-normal distribution, as verified by the Shapiro-Wilk test. Categorical variables were analyzed using Chi-square tests. A p-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

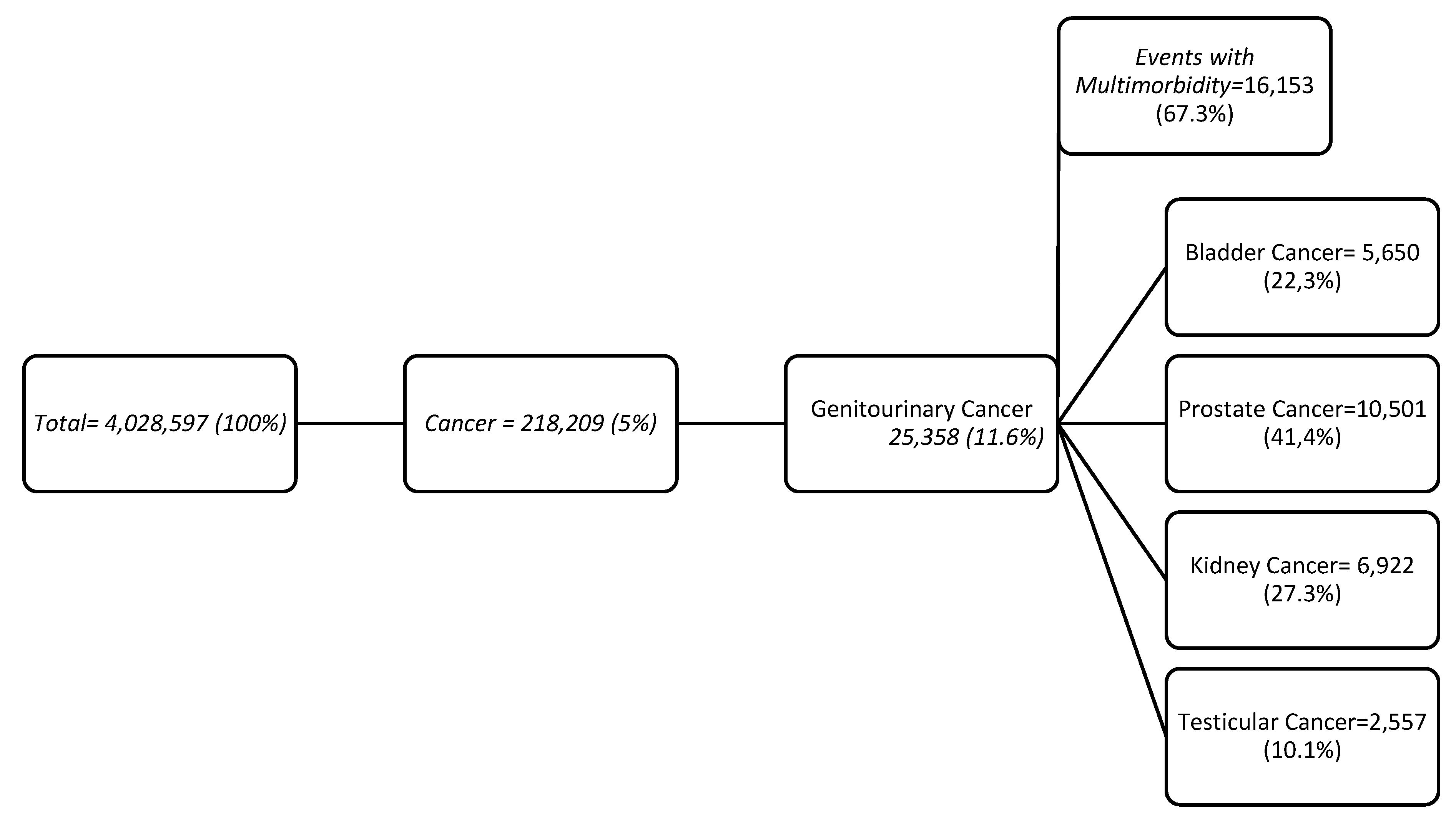

Of the total hospital events (n=4,028,597), 5% were related to cancer (n=218,209), of which 11.6% were GUC (n=25,358), representing a total of 18,792 patients. Multimorbidity was present in 67.3% of patients (two or more comorbidities) (

Figure 1).

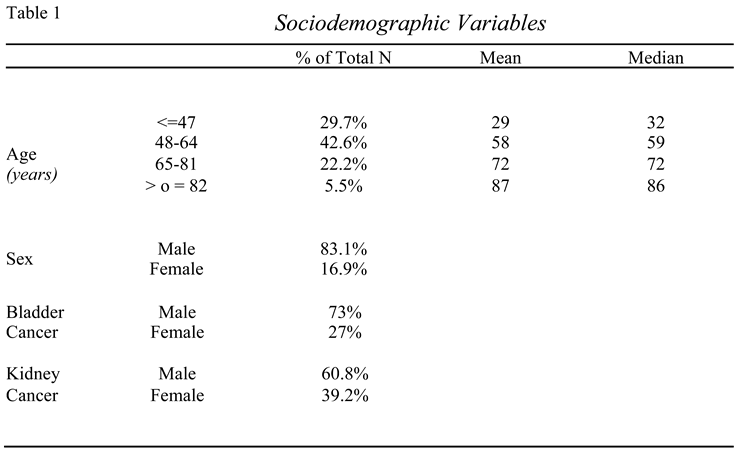

A significant proportion of patients (72.5%) were within working age. In terms of gender, all tumor types were predominantly male, reaching 73.9% in bladder cancer and 63.6% in kidney cancer. Sociodemographic variables are listed in Table 1.

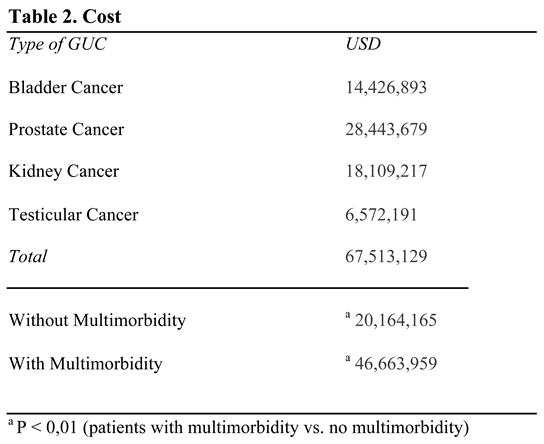

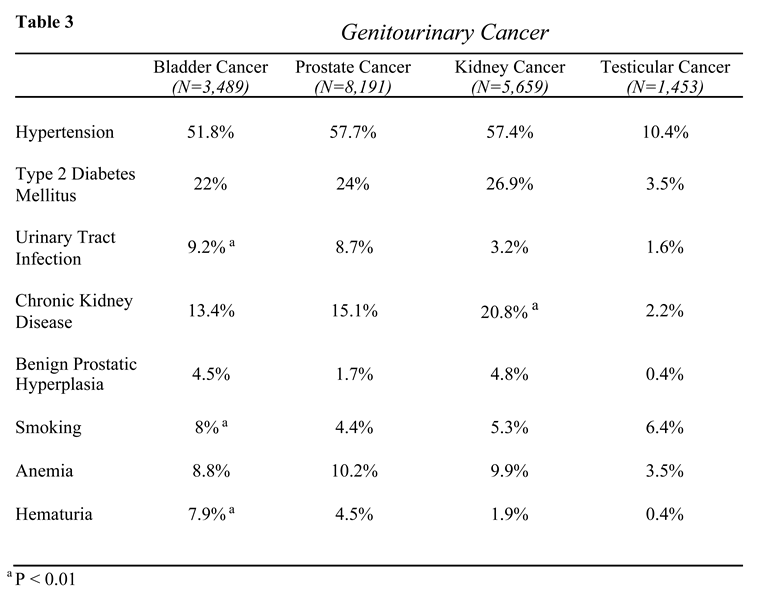

The total cost of GUC was $67,513,129 USD. Patients with multimorbidity accounted for 69.1% of the total cost. The cost descriptions in USD are detailed in Table 2. The most frequent comorbidities were hypertension (HTN) (43.9%) and type 2 diabetes mellitus (DM2) (19%). The most prevalent combined comorbidities were hypertension with diabetes mellitus (13.4%) and hypertension with chronic kidney disease (CKD) (6.9%). The comorbidities by type of GUC and their distribution are listed in Table 3.

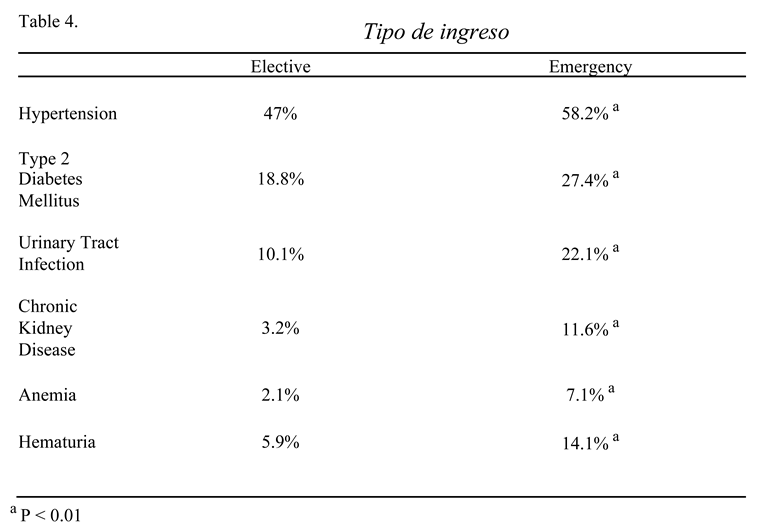

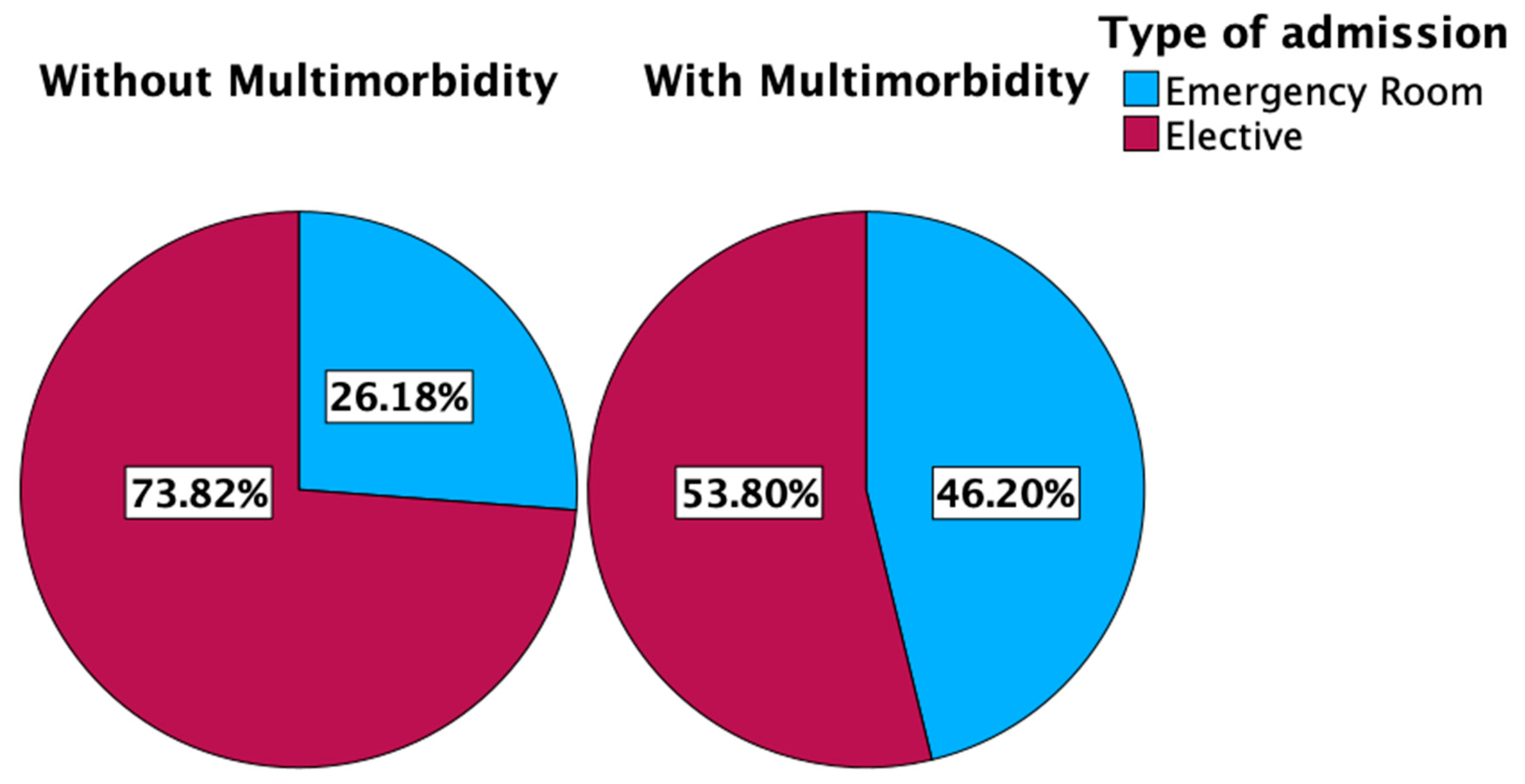

Most patients were admitted electively (60.3%), while 39.7% were admitted through the emergency room (ER). The differences between the main comorbidities are detailed in Table 4. The prevalence of comorbidities by admission type is detailed in

Figure 2.

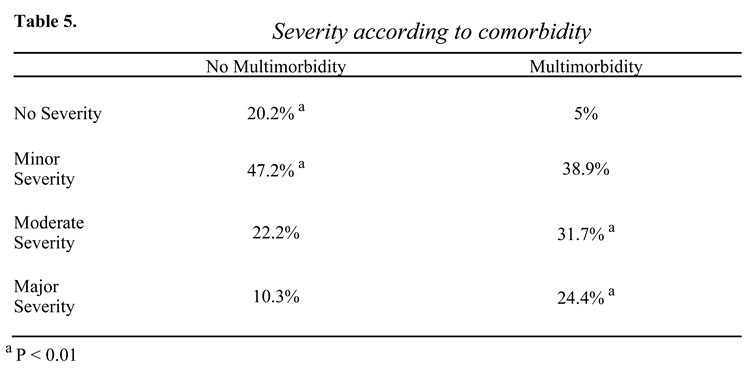

Patients with multimorbidity had a 56.1% rate of moderate/major severity hospitalizations, while those without multimorbidity had a 32.5% rate, with in-hospital mortality of 7.5% for the former and 3.7% for the latter (P<0.001). Additionally, only 5% of patients with multimorbidity had a hospitalization without severity. The severity details are shown in Table 5.

Finally, the mean length of stay was 5 days for patients without multimorbidity (DS= 7) and a total of 26,752 bed-days, being significantly higher for those with multimorbidity (mean=8 days; DS= 12; bed-day =89,960; P<0.001).

4. Discussion

This study represents the first attempt to graphically depict the impact of multimorbidity on hospitalizations in genitourinary cancer (GUC). Our results indicate that patients with multimorbidity have significantly higher hospital mortality (7.5% vs. 3.7%; P<0.001), a greater proportion of emergency admissions (46.2% vs. 26.2%; P<0.001), and longer hospital stays (8 vs. 5 days). These findings underline the substantial impact of multimorbidity on the management and outcomes of GUC, a trend that has been increasingly recognized in global oncology practice [

4,

5].

Our descriptive, population-based study is grounded in the analysis of the FONASA DRG database, which aggregates information from 70% of hospital discharges in Chile [

10,

11]. This extensive dataset allows for a comprehensive examination of the healthcare burden associated with GUC and multimorbidity within the Chilean public health system, revealing demographic patterns consistent with the WHO Global Cancer Observatory records [

12], such as the higher prevalence of GUC among males and individuals aged 65 to 81 years [

7].

Our series revealed a higher comorbidity rate in prostate cancer patients compared to the literature. A recent retrospective study in the US analyzed the relationship of comorbidity with prostate cancer, concluding that 51% had at least one associated disease, with hypertension being the most prevalent (42%), followed by hypercholesterolemia (24%) and diabetes mellitus (12%) [

5]. Our findings suggest that the burden of comorbidities in Chilean patients may be higher, potentially influenced by health access, lifestyle factors, and socioeconomic conditions.

The impact of comorbidities on early detection and treatment is particularly profound in prostate cancer, where older age correlates with a higher likelihood of comorbid conditions [

4]. Previous data emphasize that comorbidities can delay diagnosis and reduce the likelihood of receiving curative treatment, especially in resource-limited settings [

5,

13,

14,

15]. The lower influence of comorbidities on treatment decisions in high-volume centers further emphasizes the role of healthcare infrastructure in managing these complex cases [

16].

A high prevalence of multimorbidity is associated with lower quality of life and lower socioeconomic status [

17], making it important to recognize patients at risk for multimorbidity to implement interventions that improve clinical outcomes. In our series, 67.3% had multimorbidity, with poorer clinical outcomes. Prevention and identification programs focusing on multimorbidity could be key to enhancing GUC treatment outcomes in Chile, where healthcare resources are often constrained. Future research should continue to explore the intricate relationships between multimorbidity, cancer outcomes, and healthcare costs, with an emphasis on developing cost-effective, integrated care models tailored to different healthcare settings [

9].

Several factors must be considered when interpreting the results. The analysis is based on data from the FONASA DRG database, which is comprehensive, yet limited to the public healthcare system. As such, the findings might not be fully generalizable to patients receiving care in the private system, where different resources and demographics may influence outcomes. Nonetheless, since FONASA covers a significant portion of the population, particularly among the elderly and socioeconomically disadvantaged, the study provides an important perspective on the public health challenges in Chile. The descriptive and retrospective nature of the study, which relies on existing administrative data, presents additional considerations. While this approach allows for the inclusion of a large, representative sample, it also introduces potential limitations in the accuracy and completeness of comorbidity records. Misclassification or underreporting of conditions may affect the observed associations between multimorbidity and hospital outcomes. Moreover, the focus on hospitalizations may omit crucial aspects of patient care managed in outpatient settings, where many chronic conditions are treated. This focus could result in an underestimation of the true burden of multimorbidity on the healthcare system, as the study does not capture the full continuum of care required by these patients. Finally, while the study identifies significant associations between multimorbidity and adverse in-hospital outcomes, it does not explore the causal mechanisms underlying these relationships.

5. Conclusions

Multimorbidity in genitourinary cancer has a high prevalence and is associated with increased length of stay, costs, and mortality. This highlights the need for additional efforts to identify and manage this phenomenon.

Conflicts of Interest

We declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Le The World Health Report 2008-Primary Healthcare: How Wide Is the Gap between Its Agenda and Implementation in 12 High-Income Health Systems?; 2012; Vol. 7;.

- Skou, S.T.; Mair, F.S.; Fortin, M.; Guthrie, B.; Nunes, B.P.; Miranda, J.J.; Boyd, C.M.; Pati, S.; Mtenga, S.; Smith, S.M. Multimorbidity. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2022, 8. [CrossRef]

- Vogeli, C.; Shields, A.E.; Lee, T.A.; Gibson, T.B.; Marder, W.D.; Weiss, K.B.; Blumenthal, D. Multiple Chronic Conditions: Prevalence, Health Consequences, and Implications for Quality, Care Management, and Costs. In Proceedings of the Journal of General Internal Medicine; December 2007; Vol. 22, pp. 391–395.

- Ritchie, C.S.; Kvale, E.; Fisch, M.J. Multimorbidity: An Issue of Growing Importance for Oncologists. J Oncol Pract 2011, 7, 371–374.

- Sarfati, D.; Koczwara, B.; Jackson, C. The Impact of Comorbidity on Cancer and Its Treatment. CA Cancer J Clin 2016, 66, 337–350. [CrossRef]

- Raghavan, D.; Skinner, E. Genitourinary Cancer in the Elderly. Semin Oncol 2004, 31, 249–263. [CrossRef]

- Ferlay, J.; Colombet, M.; Soerjomataram, I.; Parkin, D.M.; Piñeros, M.; Znaor, A.; Bray, F. Cancer Statistics for the Year 2020: An Overview. Int J Cancer 2021, 149, 778–789. [CrossRef]

- Parra-Soto, S.; Petermann-Rocha, F.; Martínez-Sanguinetti, M.A.; Leiva-Ordeñez, A.M.; Troncoso-Pantoja, C.; Ulloa, N.; Diaz-Martínez, X.; Celis-Morales, C.; Parra-Soto, S.; Petermann-Rocha, F.; et al. Cáncer En Chile y En El Mundo: Una Mirada Actual y Su Futuro Escenario Epidemiológico. Rev Med Chil 2020, 148, 1489–1495. [CrossRef]

- Yeung, C.; Dinh, T.; Lee, J. The Health Economics of Bladder Cancer: An Updated Review of the Published Literature. Pharmacoeconomics 2014, 32, 1093–1104. [CrossRef]

- 2023; 10. FONASA NOTA METODOLÓGICA Indicadores Panel FONASA; 2023;

- FONASA Base de Datos GRD FONASA.

- Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Laversanne, M.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A.; Bray, F. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J Clin 2021, 71, 209–249. [CrossRef]

- Koppie, T.M.; Serio, A.M.; Vickers, A.J.; Vora, K.; Dalbagni, G.; Donat, S.M.; Herr, H.W.; Bochner, B.H. Age-Adjusted Charlson Comorbidity Score Is Associated with Treatment Decisions and Clinical Outcomes for Patients Undergoing Radical Cystectomy for Bladder Cancer. Cancer 2008, 112, 2384–2392. [CrossRef]

- Lee, L.; Cheung, W.Y.; Atkinson, E.; Krzyzanowska, M.K. Impact of Comorbidity on Chemotherapy Use and Outcomes in Solid Tumors: A Systematic Review. Journal of Clinical Oncology 2011, 29, 106–117.

- Xiao, H.; Tan, F.; Goovaerts, P.; Adunlin, G.; Ali, A.A.; Gwede, C.K.; Huang, Y. Impact of Comorbidities on Prostate Cancer Stage at Diagnosis in Florida. Am J Mens Health 2016, 10, 285–295. [CrossRef]

- Post, P.N.; Kil, P.J.M.; Hendrikx § ¶, A.J.M.; Janssen-Heijnen, M.L.G.; Crommelin, M.A.; Coebergh, J.W.W. Comorbidity in Patients with Prostate Cancer and Its Relevance to Treatment Choice; 1999; Vol. 84;.

- Ahmad, T.A.; Gopal, D.P.; Chelala, C.; Zm, A.; Ullah, D.; Taylor, S.J. Review Article Multimorbidity in People Living with and beyond Cancer: A Scoping Review. Am J Cancer Res 2023, 13, 4346–4365.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).