1. Introduction

Self-esteem is a psychological concept that has been the subject of study since 1890, when William James introduced it. The most common definition is that of Rosenberg (RSE) [

1], who describes it as the attitude a person has towards themselves, whether positive or negative. Self-esteem has been researched in various areas of psychology. In the clinical field, it has been found to be related to mental health and lower levels of depression [

2]. In positive psychology, it has been linked to resilience and life satisfaction [

3]. In the military context, an adequate level of self-esteem is crucial for combatants to successfully face survival situations [

4]. Burger and Bachmann [

5] highlight that living in hostile environments characterized by violence can harm self-esteem, while a warm and safe environment strengthens it. Developing social skills in military personnel could be beneficial, as these are closely related to self-esteem and physical activity [

6], which could enhance their professional effectiveness and personal well-being. Self-esteem also acts as a protective factor against stress in combat; military personnel with high self-esteem tend to use healthy strategies to manage stress [

7] and have self-confidence [

8].

A study by Lee et al. [

9] examined the relationship between post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), stress, depression, self-esteem, and impulsivity. The results showed that PTSD is positively related to depression, stress, and impulsivity, while it has a negative relationship with self-esteem. In turn, self-esteem is closely related to resilience, as a positive attitude towards oneself facilitates adaptation to the environment, which in turn increases an individual's ability to cope with pressures in various situations [

10]. Thus, adequate self-esteem acts as a protective factor that enhances effectiveness in managing such circumstances [

11].

Currently, several instruments have been developed to measure self-esteem. Some of the most notable are the

Coopersmith Self-Esteem Inventory [

12], the

Collective Self-Esteem Scale by Diener et al. [

13], and the

Single-Item Self-Esteem Scale [

14]. However, the most widely used scale is the

Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (RSE) [

1], which consists of 10 items that assess positive or negative self-evaluation. In Latin America, adaptations of this scale have primarily focused on adolescents [

15], with few studies directed at adults. In this regard, validation studies have presented methodological limitations that raise doubts about their results. In exploratory factor analysis (EFA), many studies [

16,

17,

18] used the Little Jiffy method, which does not account for measurement error, potentially leading to an overestimation of factor loadings and explained variance [

19]. Additionally, reliability is estimated using Cronbach's alpha and McDonald's omega. Alpha requires meeting assumptions such as tau-equivalence and unidimensionality of the instrument [

20], as well as continuous variables with interval measurement [

21]. On the other hand, omega requires factor loadings obtained from a confirmatory factor analysis [

22].

Finally, the factor structure of the RSE is a subject of debate, with positions considering it to be either bidimensional or unidimensional. A meta-analysis suggests a two-factor structure, composed of positive and negative items [

23], which has also been supported by confirmatory factor analyses [

24]. The negative wording of some items may contribute to the emergence of a new dimension [

25]. Additionally, a method effect associated with negative items has been identified [

26]. However, this effect persists in the RSE despite the efforts made to address it.

1.1. The present Study

Based on the above, the present study aims to evaluate the validity based on internal structure from the perspective of Classical Test Theory (CTT) and Item Response Theory (IRT), in order to obtain evidence of validity related to other variables and to estimate the reliability of the RSE in military personnel of the Spanish Army.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Procedures

The sample consisted of 584 soldiers from the Spanish Army (4.5% officers, 17.5% non-commissioned officers, and 78% professional troops and sailors), with an average age of 33.17 years (SD = 7.38), ranging from 18 to 66 years. Regarding gender, 87.70% (n = 511) were men, while 12.30% (n = 72) were women. Specifically, the sample belonged to the same barracks, composed of both operational units and support units. The study sample was extracted through non-probabilistic intentional sampling.

The present study has a quantitative approach and presents an instrumental design, as the objectives are oriented towards evaluating the psychometric properties of a measurement instrument [

27].

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Central Defense Hospital (Approval Code: 51117). Once this permission was obtained, the purpose of the study was communicated to the military authorities stationed at the King Alfonso XIII Legion Brigade (BRLIEG, Almería), specifically to the Honorable Colonel Chief of the Alvarez de Sotomayor Services Unit (Chief of the Barracks) and to the Excellency General (Chief of BRILEG). Subsequently, after receiving authorization for the research from these officials, several meetings were held with leaders of different Units to inform them about the objectives of the research, ensuring them that data confidentiality would be maintained. During these meetings, a work schedule was developed indicating the day each Unit (both operational and support units) was to participate. In this regard, prior to participation in the study, participants were informed about its objective and voluntary nature, both verbally and in writing, outlining the procedure for participation, anonymous treatment, and data confidentiality, adhering to ethical research standards as established by the Helsinki Declaration [

28], which guarantees the following criteria: a) Confidentiality of collected data and its exclusive use for research purposes; b) Anonymity of data; c) Professional secrecy in data collection.

After being informed, each participant was then given a questionnaire individually, which was placed in an envelope that they were required to return sealed in its respective envelope after completing it. This process took an average time of 25-30 minutes.

2.1. Instruments

First, an ad hoc questionnaire was used to collect sociodemographic data (age and gender). First, the authors developed a booklet containing already validated instruments along with an ad hoc questionnaire that collected sociodemographic aspects of the participants (gender and age). To assess self-esteem, the RSE [

1] was used. This instrument is made up of 10 items with four response options (Strongly agree: 4; Agree: 3; Disagree: 2; Strongly disagree: 1). As for the reliability properties, the author of the scale found a reliability of

α = .75 [

1]. In this study it presents an

α = .80 (ɷ = .81). For resilience, the

Resilience Scale (RS) developed by Wagnild and Young [

29] was used. It is one of the few reliable and valid psychometric tools for assessing levels of psychosocial adaptation to significant life events [

30]. The RS consists of 25 items with a

Likert response format that ranges from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). In terms of reliability, studies such as the one conducted by Dias et al. [

31] report an alpha coefficient of

α = .72. Meanwhile, Wagnild and Young [

29] found even greater reliability, with an

α = .90. In this study the SR presents an

α = . 92 (ω = .93).

2.4. Data Analysis

First, the database was cleaned by removing outlier data. Next, descriptive analyses of mean, standard deviation, as well as skewness (As) and kurtosis (Ku) were estimated, with values considered acceptable when As < ±2 and Ku < ±7 [

32]. Subsequently, confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was conducted using the Diagonally Weighted Least Squares with Mean and Variance corrected (WLSMV) estimator, as the data were ordinal [

33]. For model evaluation, the fit indices used were chi-square (

χ2), Comparative Fit Index (CFI), Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI), Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA), and Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR). Cut-off points for evaluating the fit indices were considered based on Hu and Bentler's proposal: CFI > .95, TLI > .95, RMSEA < .08, SRMR < .08 [

34]. Regarding validity related to other variables, the structural equation modeling (SEM) approach was employed to evaluate the relationship between self-esteem and resilience. For this purpose, the WLSMV estimator was used due to the ordinal nature of the data, and the evaluation was conducted using the same values as in the CFA. For Item Response Theory (IRT), a Graded Response Model (GRM) [

35] was utilized, specifically an extension of the two-parameter logistic model (2-PLM) for ordered polytomous items [

36]. For each item, two types of parameters were estimated: a) discrimination and b) difficulty. The discrimination parameter determines the slope at which responses to the items change based on the level of the latent trait, while the item difficulty parameters determine how much of the latent trait is required for an item to be answered.

Descriptive data and reliability were calculated using SPSS statistical software version 25.0 [

37], and confirmatory factor analyses were performed with AMOS software version 24.0 [

38].

2.5. Revision, Translation, and Adaptation to the Military Context

Since the instrument was created for a different population, a process of translation, adaptation, and standardization was necessary to achieve content validity. The items were first translated into Spanish by a native translator (back-translation), considering four criteria [

39]:

1. The cultural context in which the adaptation will take place.

2. Technical aspects of the development and adaptation of the test.

3. Test administration.

4. Interpretation of the scores.

Subsequently, a military member from one of the participating units at the Almeria garrison verified the items to ensure that the questions were relevant to military personnel.

2.6. Content Validation

For content validity, expert judgment was used, which is a useful validation method for verifying the reliability of a survey [

40]. Of the total number of experts, two were from the University of La Rioja and were specialists in testing and psychometrics, while the other two were military personnel belonging to the officer corps, with more than ten years of experience.

3. Results

Firstly, in

Table 1, it can be seen that the average score of the 10 items ranges from 2.91 (

SD = 1.37) to 3.59 (

SD = .69). Additionally, the skewness and kurtosis indicate that all items have adequate values (As < ±2; Ku < ±7), according to the criteria set by Finney and DiStefano [

32].

3.1. Evidence Based on Internal Structure

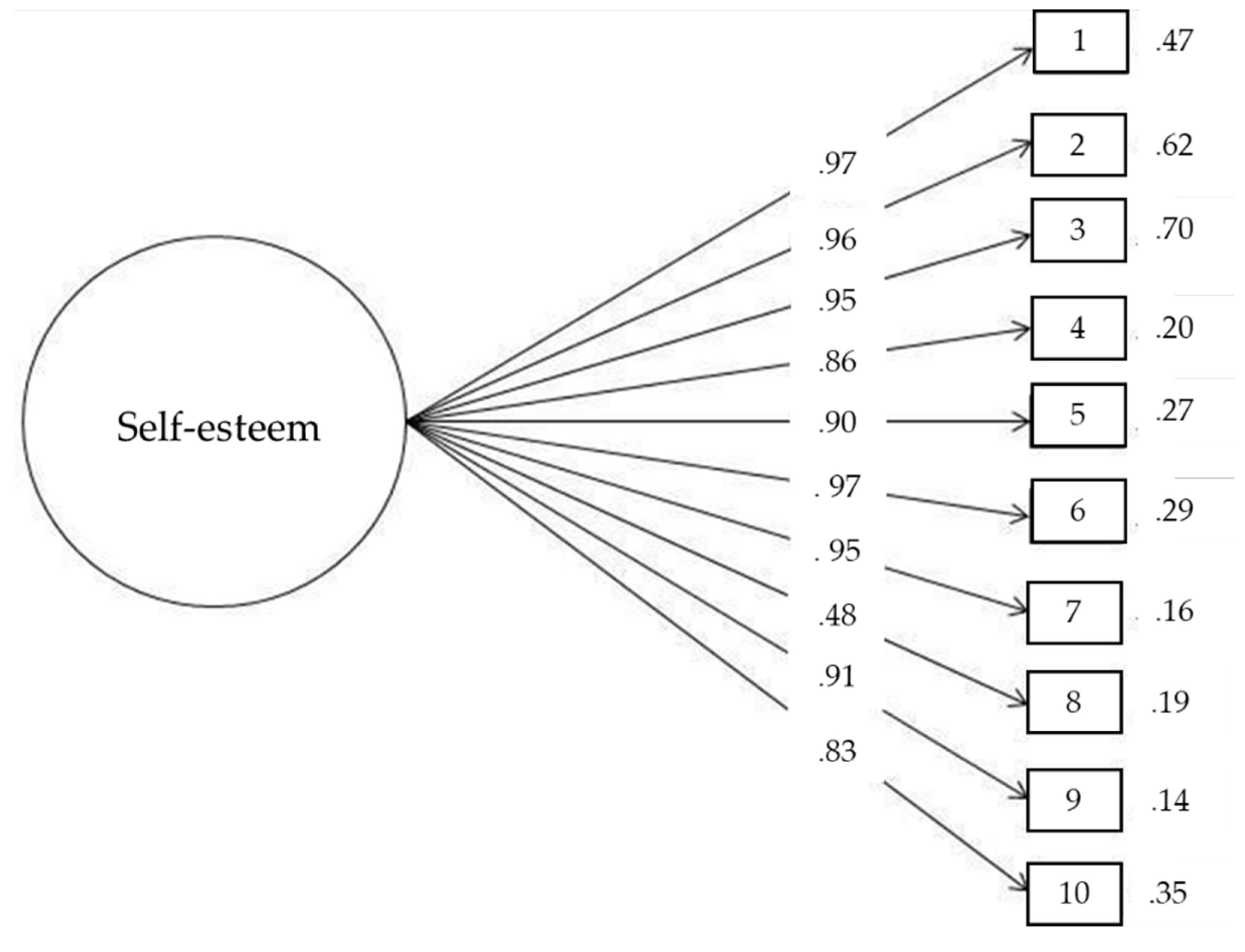

Regarding the factorial structure with a general factor, the confirmatory factor analysis demonstrated fit indices (

χ2 = 118.18, df = 26,

p < .001, CFI = .94, TLI = .91, RMSEA = .07, 90% CI [.064, .093], SRMR = .05), and the factor loadings of the items were above .95 (

Figure 1).

3.2. Validity Based on the Relationship with Other Variables

To obtain evidence of validity related to other variables, a model was developed using the SEM approach to evaluate the relationships between the RSE and the variable resilience. The results show that the proposed model demonstrates adequate values in the fit indices (χ2 = 1202.36, df = 525, p < .001, CFI = .92, TLI = .91, RMSEA = .047, 90% CI [.44, .51], SRMR = .05). Additionally, the items showed appropriate values in representing the measurement variables. Regarding the relationship values, positive correlations were found between self-esteem and resilience (.30; p < .01).

3.3. Item Response Theory model: Graded Response Model

The results found in the confirmatory factor analysis support the two main assumptions: the existence of unidimensionality and, consequently, local independence. Therefore, a graded response model (GRM) was used, specifically an extension of the two-parameter logistic model (2-PLM) for ordered polytomous items.

Table 2 shows that all items have discrimination parameters above the value of 1, which is generally considered good discrimination [

36]. Regarding the difficulty parameters, all threshold estimates increased monotonically. That is, a greater presence of the latent trait is required to respond to the higher response categories.

3.4. Reliability

In the study, the scale demonstrates adequate indices of internal consistency (ɷ = .81; α = .80).

Finally, the structure of the self-esteem scale items is presented in this work, as shown in the following (see

Appendix I).

4. Discussion

The present research aimed to evaluate the validity based on internal structure from the perspective of CTT and IRT, in order to obtain evidence of validity based on the relationship with other variables and to estimate the reliability of the RSE in military personnel of the Spanish Army. Regarding the internal structure of the model, it is evident that most fit indices are adequate for the unidimensional model (CFI = .94, TLI = .91, RMSEA = .07, SRMR = .05). These results align with the study by Vilca et al. [

42], which reported a unidimensional structure in another line of research. The results are similar to those found in previous studies that identify a good fit for the unidimensional model [

43,

44,

45]. Regarding reliability, an adequate value was obtained using Cronbach's alpha coefficient (α = .80), similar to that found in previous studies with university students [

17,

45,

46,

47,

48]. Additionally, an adequate value was evidenced in the omega coefficient (ɷ = .81). This result is also similar to those found in other studies [

49,

50].

Regarding validity based on the relationship with other constructs, it was evidenced that self-esteem is related to resilience [

3]. On the other hand, authors such as Diener [

13] explain that individuals with a positive self-perception have greater confidence in pursuing their current and future projects, resulting in a more meaningful life. Additionally, this result is similar to those found in other studies [

51,

52]. Furthermore, the relationship between self-esteem and depression, anxiety, and stress [

53] can be explained from the theoretical perspective of self-esteem, as developing high self-esteem leads to better self-acceptance, self-confidence, and self-efficacy, which are protective factors that reduce levels of depression, anxiety, and stress that an individual may experience. There are also various studies supporting the positive influence of self-esteem on these variables [

1,

54,

55].

On the other hand, regarding the IRT models, optimal values were found in the discrimination parameters. Such findings indicate that these items are more precise indicators for evaluating the construct. This allows respondents to have greater ease in differentiating their choice of response alternatives based on the presence of the latent trait. Concerning the difficulty parameter, it was found that a greater presence of the latent trait is necessary to choose the higher response categories. Additionally, regarding the TIC, it was identified that the scale is useful and reliable for recognizing university students with low levels of self-esteem.

However, despite the results obtained, this study reveals some limitations. First, a purposive sampling was conducted, which does not allow for the generalization of the results to other contexts within the Army, such as the Navy or the Air Force. Additionally, reliability was not assessed through a test-retest method, which would help identify whether there are variations in scores over time.

Finally, this study demonstrates that the new self-esteem scale, called the Rosenberg-Jose Gabriel Army Self-Esteem Scale (RSE-JGA), exhibits adequate psychometric properties. Additionally, support was provided for the unidimensional structure from both a CTT and IRT perspective, and it was reported that this new scale has validity evidence based on its relationship with resilience, a relevant variable for successfully coping with adverse situations throughout a military career. Furthermore, it shows an adequate reliability value.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, the RSE-JGA demonstrates adequate psychometric properties of validity and reliability in military personnel of the Spanish Army. This provides a useful and relevant measure for assessing self-evaluation in the military context.

Author Contributions

J.G.S.S. and S.S.R. contributed to analyzed the data and interpreted data and J.G.S.S. wrote the manuscript. J.G.S.S. and S.S.R. edited this manuscript. J.G.S.S. is responsible for the overall project. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Central Defense Hospital (Approval Code: 51117).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the research can be requested from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our gratitude to all the staff of the King Alfonso XIII Legion Brigade (Almería) for their interest in participating, as well as to the Ethics Committee of the Central Defense Hospital for approving this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A. Item Composition of the Validated Instrument

| |

Nunca me pasa |

A veces me pasa |

Casi siempre me pasa |

Siempre me pasa |

| 1. Me siento una persona tan valiosa como las otras. |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

| 2. En general, me inclino a pensar que soy un fracasado. |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

| 3. Creo que tengo algunas cualidades buenas. |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

| 4. Soy capaz de hacer las cosas tan bien como los demás. |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

| 5. Creo que no tengo mucho de lo que estar orgulloso. |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

| 6. Tengo una actitud positiva hacia mí mismo. |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

| 7. En general, me siento satisfecho conmigo mismo. |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

| 8. Me gustaría tener más respeto por mi mismo. |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

| 9. Realmente me siento inútil en algunas ocasiones. |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

| 10. A veces pienso que no sirvo para nada. |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

References

- Rosenberg, M. Society and the adolescent self-image; Princeton University Press, 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, C.-C. Self-esteem and depression as mediators of the effects of gratitude on suicidal ideation among Taiwanese college students. Omega (Westport). 2021, 84, 399–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, A.; Kumar, S.; Lindinger-Sternart, S. Self-esteem and life satisfaction among university students of Eastern Uttar Pradesh of India: A demographical perspective. Ind J Posit Psychol. 2018, 9, 382–386. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez, J.A. Aspectos psicológicos de la supervivencia en operaciones militares. Sanid Mil. 2011, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burger, C.; Bachmann, L. Perpetration and victimization in offline and cyber contexts: A variable and person oriented examination of associations and differences regarding domain-specific self-esteem and school adjustment. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021, 18, 10429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koszałka-Silska, A.; Korcz, A.; Wiza, A. Correlates of social competences among Polish adolescents: Physical activity, self-esteem, participation in sports and screen time. Sustainability. 2021, 13, 13845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyun, S.; Ku, X.; Lee, H.; Kang, S.; Lee, B. The effect of self-esteem on combat stress in engagement: An XR simulator study. Pers Individ Dif. 2022, 193, 111609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bsharat, F. Relationship between emotional intelligence and self-esteem among nursing students. SAGE Open Nurs. 2024, 10, 23779608241252248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.E.; Choi, B.; Lee, Y.; Kim, K.M.; Kim, D.; Park, T.W.; Lim, M.H. The relationship between posttraumatic embitterment disorder and stress, depression, self- esteem, impulsiveness, and suicidal ideation in Korea soldiers in the local area. J Korean Med Sci. 2023, 38, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González ALópez, N.I.; Domínguez A del, C.; Valdez, J.L. Autoestima como mediador entre Afecto positivo-negativo y resiliencia en niños. Acta Univ [Internet]. 2017, 27, 88–94. [Google Scholar]

- Yetim, O. Examining the relationships between stressful life event, resilience, self-esteem, trauma, and psychiatric symptoms in Syrian migrant adolescents living in Turkey. Int J Adolesc Youth. 2022, 27, 221–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coopersmith, S.W.H.; Diener, E.; Emmons, R.A.; Larsem, R.J.; Griffin, S. The Satisfaction With Life Scale. J Pers Assess. 1967, 49, 71–5. [Google Scholar]

- Diener, E.; Emmons, R.A.; Larsen, R.J.; Griffin, S. The satisfaction with life scale. J Pers Assess. 1985, 49, 71–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robins, R.W.; Hendin, H.M.; Trzesniewski, K.H. Measuring global self-esteem: Construct validation of a Single-item measure and the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale. Pers Soc Psychol Bull. 2001, 27, 151–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, G.D.; Alfaro, A.L. Validación de la escala de autoestima de Rosenberg en estudiantes paceños. Fides et Ratio. 2019, 17, 83–99. [Google Scholar]

- Góngora, V.C.; Casullo, M.M. Validación de la escala de autoestima de Rosenberg en población general y en población clínica de la Ciudad de Buenos Aires. Rev Iberoam Diagn Eval - Aval Psicol. 2009; 1, 179–194. [Google Scholar]

- Hutz, C.S.; Zanon, C. Revisão da adaptação, validação e normatização da escala de autoestima de Rosenberg. Rev Aval Psicol. 2011, 10, 41–49. [Google Scholar]

- Rojas-Barahona, C.A.; Zegers, P.B.; Förster, M.C.E. La escala de autoestima de Rosenberg: Validación para Chile en una muestra de jóvenes adultos, adultos y adultos mayores. Rev Med Chil. 2009, 137, 791–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrando, P.J.; Anguiano-Carrasco, C. El análisis factorial como técnica de investigación en psicología. Pap psicól. 2010, 31, 18–33. [Google Scholar]

- Tavakol, M.; Dennick, R. Making sense of Cronbach’s alpha. Int J Med Educ. 2011, 2, 53–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elosua Oliden, P.; Zumbo, B.D. Coeficientes de fiabilidad para escalas de respuesta categórica ordenada. Psicothema. 2008, 20, 896–901. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Viladrich, C.; Angulo-Brunet, A.; Doval, E. Un viaje alrededor de alfa y omega para estimar la fiabilidad de consistencia interna. An Psicol. 2017, 33, 755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.; Dong, N. Factor structures of the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale: A meta-analysis of pattern matrices. Eur J Psychol Assess. 2012, 28, 132–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michaelides, M.P.; Koutsogiorgi, C.; Panayiotou, G. Method effects on an adaptation of the Rosenberg self-esteem scale in Greek and the role of personality traits. J Pers Assess. 2016, 98, 178–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DiStefano, C.; Motl, R.W. Further investigating method effects associated with negatively worded items on self-report surveys. Struct Equ Modeling. 2006, 13, 440–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Lima, T.J.S.; de Souza, L.E.C. Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale: Method effect and gender invariance. Psico-USF. 2019, 24, 517–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ato, M.; López-García, J.J.; Benavente, A. Un sistema de clasificación de los diseños de investigación en psicología. An Psicol. 2013, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rennie, D. Trial registration: A great idea switches from ignored to irresistible. JAMA. 2004, 292, 1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagnild, G.M.; Young, H.M. Development and psychometric evaluation of the Resilience Scale. J Nurs Meas. 1993, 1, 165–1678. [Google Scholar]

- Heilemann, M.V.; Lee, K.; Kury, F.S. Psychometric properties of the Spanish version of the Resilience Scale. J Nurs Meas. 2003, 11, 61–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, C.M.; Saraiva, A.; Faísca, L. Treino da resistência psicológica na recruta Militar em Portugal: O papel da coesão militar, da estima de si e da ansiedade na resiliência. Av Psicol Latinoam. 2017, 35, 317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finney, S.J.; Distefano, C. Nonnormal and categorical data in structural equation modeling. En: En GR, Hancock RO, editores. Structural equation modeling: a second course. Connecticut: Information Age Publishing; 2006. p. 269–314.

- Brown, T.A. Confirmatory factor analysis for applied research, second edition. 2a ed. Nueva York, NY, Estados Unidos de América: Guilford Publications; 2015.

- Hu, L.-T.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct Equ Modeling. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samejima, F. Graded response model. En: Handbook of Modern Item Response Theory. New York, NY: Springer New York; 1997. p. 85–100.

- Hambleton, R.K.; Van Der Linden, W.J.; Wells, C.S. IRT models for the analysis of polytomously scored data: Brief and selected history of model building advances. En Handbook of polytomous item response theory models. 2010, 21–42. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, A.F. Beyond baron and Kenny: Statistical mediation analysis in the new millennium. Commun Monogr. 2009, 76, 408–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F. An introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: a regression-based approach; The Guilford Press, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Martín-Arribas, M.C. Diseño y validación de cuestionarios. Matron Profes. 2004, 5, 23–29. [Google Scholar]

- Escobar-Pérez, J.; Cuervo-Martínez, A. Validez de contenido y juicio de expertos: Una aproximación a su utilización. Av Med. 2008, 6, 27–36. [Google Scholar]

- Martín-Arribas, M.C. Diseño y validación de cuestionarios. Matro Profes. 2004, 5, 23–29. [Google Scholar]

- Vilca, L.W.; Travezaño-Cabrera, A.; Santos-Garcia, S. Escala de autoestima de Rosenberg (EAR): Análisis de la estructura factorial y propuesta de una nueva versión de solo ítems positivos. Rev Electron Investig Psicoeduc Psigopedag. 2022, 20, 225–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín-Albo, J.; Núñez, J.L.; Navarro, J.G.; Grijalvo, F. The Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale: Translation and validation in university students. Span J Psychol. 2007, 10, 458–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pullmann, H.; Allik, J. The Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale: its dimensionality, stability and personality correlates in Estonian. Pers Individ Dif. 2000, 28, 701–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tinakon, W.; Nahathai, W. A comparison of reliability and construct validity between the original and revised versions of the Rosenberg self-esteem scale. Psychiatry Investig. 2012, 9, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceballos Ospino, G.A.; Paba Barbosa, C.; Suescún, J.; Oviedo, H.C.; Herazo, E.; Campo Arias, A. Validez y dimensionalidad de la escala de autoestima de Rosenberg en estudiantes universitarios. Pensam Psicol. 2017, 15, 29–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cárdenas, D.J.; Cárdenas, S.J.; Villagrán, K.L.; Guzmán, B.Q. Validez de la Escala de Autoestima de Rosenberg en universitarios de la Ciudad de México. Rev Latinoam Med Conduct/Lat Am J Behav Med [Internet]. 2015, 5, 18–22. [Google Scholar]

- Kielkiewicz, K.; Mathúna, C.Ó.; McLaughlin, C. Construct validity and dimensionality of the Rosenberg self-esteem scale and its association with spiritual values within Irish population. J Relig Health. 2020, 59, 381–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Travezaño-Cabrera, A.; Santos-Garcia, S.; Vilca, L.W. Escala de autoestima de Rosenberg-P (EAR-P) en universitarios: Nuevas evidencias psicométricas de su estructura interna. Interdiscip Rev Psicol Cienc Afines [Internet]. Disponible en:. 2024, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ventura-León, J.; Caycho-Rodriguez, T.; Barboza-Palomino, M. Evidencias psicométricas de la escala de autoestima de Rosenberg en adolecentes limeños. Interam J Psychol, 2018, 52, 44–60. [Google Scholar]

- Agberotimi, S.F.; Oduaran, C. Moderating effect of self-esteem on the relationship between optimism and life satisfaction in final year university students. Glob J Health Sci. 2020, 12, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saadat, M.; Ghasemzadeh, A.; Soleimani, M. Self-esteem in Iranian university students and its relationship with academic achievement. Procedia Soc Behav Sci. 2012, 31, 10–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Zhang, X.; Gao, Y.; Xiao, Q. Social anxiety and problematic social network site use: The sequential mediating role of self-esteem and self-concept clarity. J Psychol Afr. 2024, 34, 114–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyseni, Z.; Hoxha, L. Self-esteem, study skills, self-concept, social support, psychological distress, and coping mechanism effects on test anxiety and academic performance. Health Psychol Open. 2018, 5, 205510291879996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurtović, A.; Vuković, I.; Gajić, M. The effect of locus of control on university students’ mental health: Possible mediation through self-esteem and coping. J Psychol. 2018, 152, 341–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).