Submitted:

09 September 2024

Posted:

10 September 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design, Population, and Sampling

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Variables and Data Collection Instruments

2.3.1. Dependent Variable

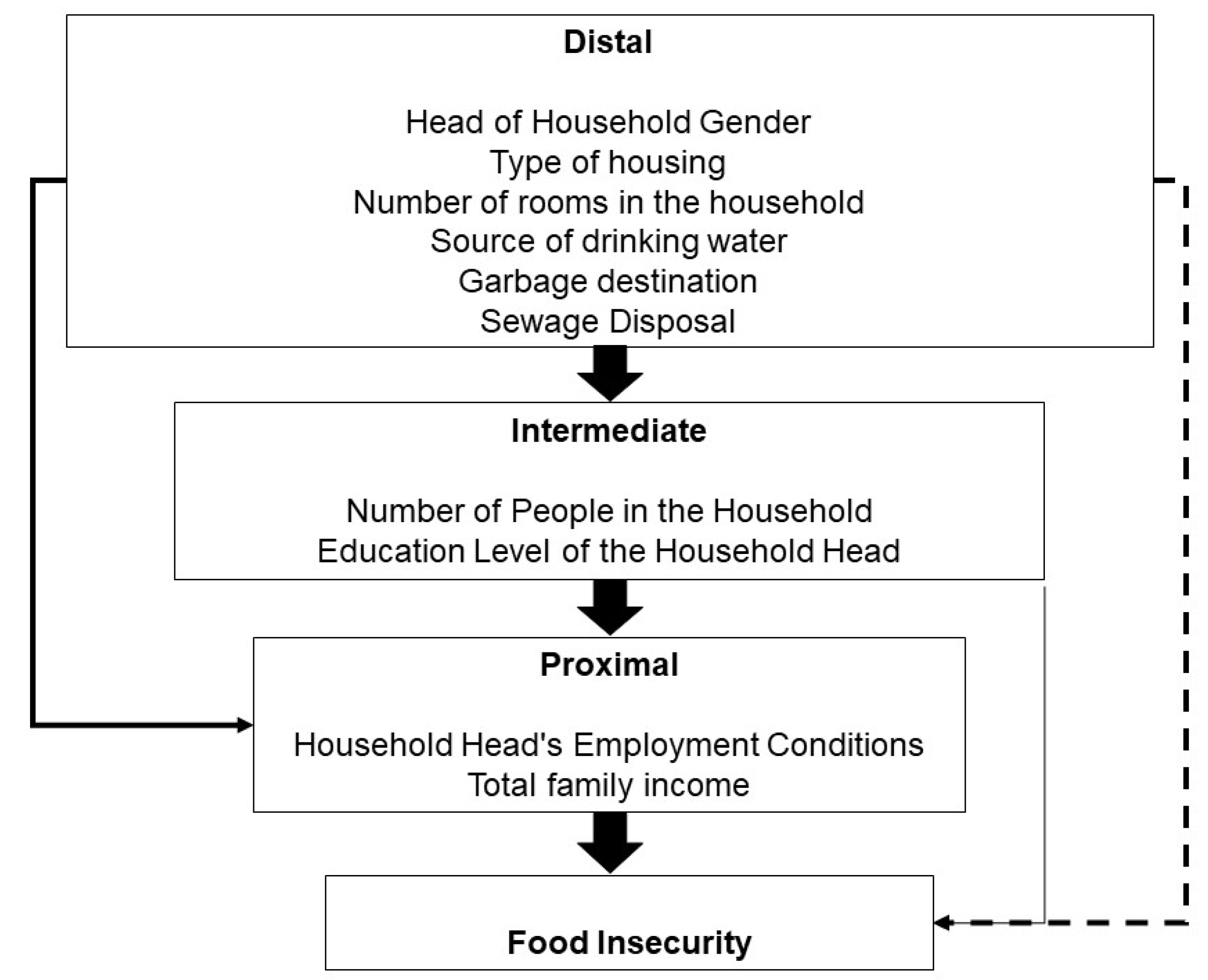

2.3.2. Independent Variables

2.4. Data Processing and Analysis

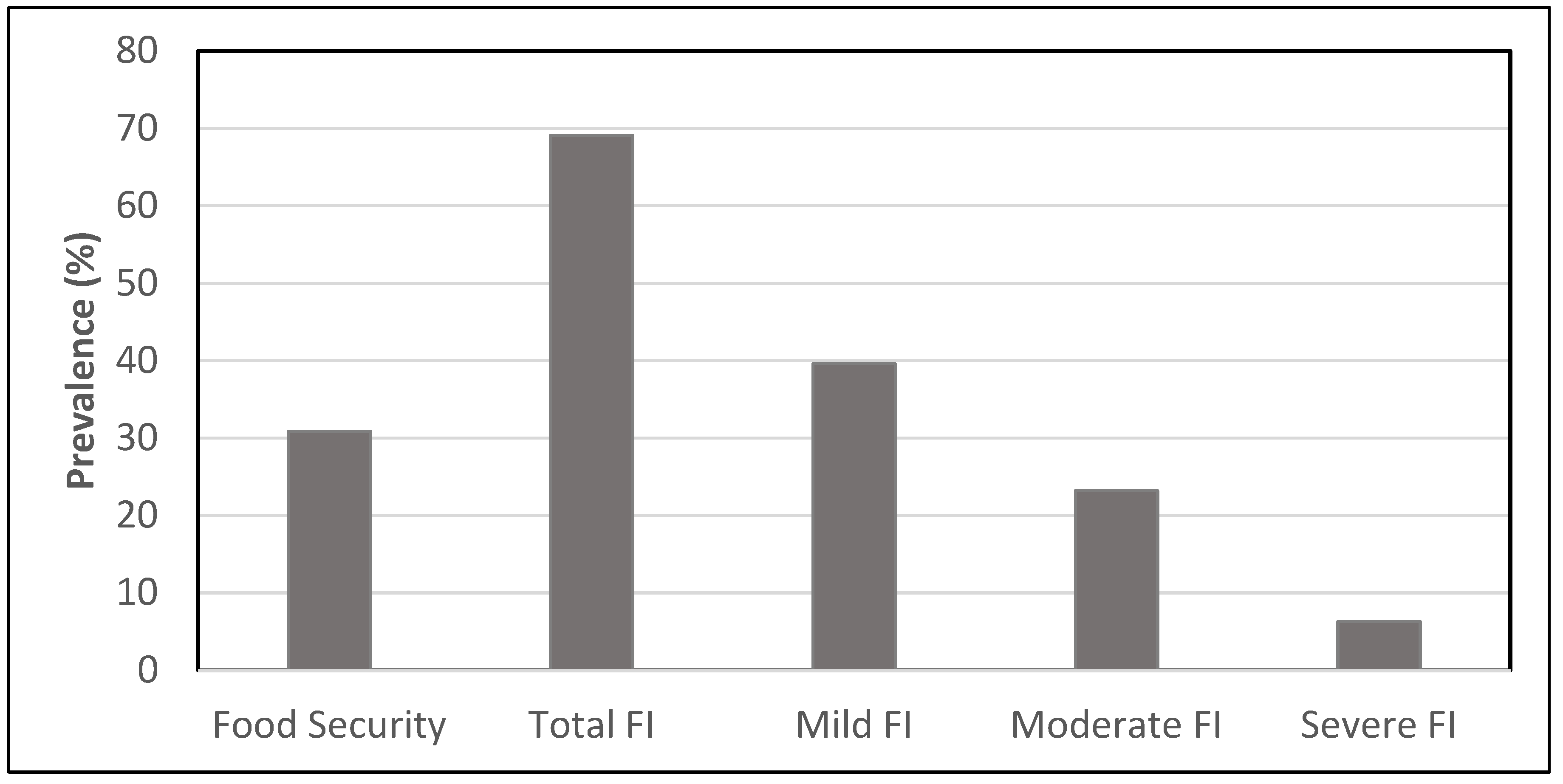

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest:The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

| BFP | Bolsa Família Program |

| DOHaD | Developmental Origins of Health and Disease |

| EBIA | Brazilian Food Insecurity Scale |

| ENSSAIA | Study on Nutrition, Health, and Food Security of Indigenous Peoples in the State of Alagoas |

| FAO | Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations |

| FI | Food insecurity |

| FS | Food security |

| MSFI | The sum of moderate and severe food insecurity |

| NMW | National Minimum Wage |

| PR | Prevalence ratio |

| 95%CI | 95% confidence interval |

References

- Bezerra, M.S.; Jacob, M.C.M.; Ferreira, M.A.F.; Vale, D.; Mirabal, I.R.B.; Lyra, C.O. Insegurança alimentar e nutricional no Brasil e sua correlação com indicadores de vulnerabilidade. Ciência & Saúde Coletiva 2020, 25, 3833–3846. [Google Scholar]

- Brasil. Lei nº 11.346, de 15 de setembro de 2006. Cria o Sistema Nacional de Segurança Alimentar e Nutricional-SISAN com vistas em assegurar o direito humano à alimentação adequada e dá outras providências. Diário Oficial da União 2006, 143, 1–2. [Google Scholar]

- IBGE. Censo Demográfico 2022: Indígenas: primeiros resultados do universo. Rio de Janeiro, 2023.

- Jorge, C.A.S.; Souza, M.C.C. Insegurança Alimentar entre famílias indígenas de Dourados, Mato Grosso do Sul, Brasil. Saúde Coletiva (Barueri) 2023, 13, 13337–13356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, T.M.G.; Magalhães, S.M.; Nazareno, E. Estado do conhecimento sobre história da alimentação indígena no Brasil. História: Questões & Debates 2020, 68. [Google Scholar]

- Segall-Corrêa, A.M.; Marín-Leon, L.; Amaral Azevedo, M.M.; Ferreira, M.B.R.; Gruppi, D.R.; Camargo, D.F.; Toledo Vianna, R.P.; Pérez-Escamilla, R. The Brazilian food security scale for indigenous Guarani households: development and validation. Food Security 2018, 10, 1547–1559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira, J.L.G. Povoamentos: ocupação e espoliação. In Alagoas: a herança indígena, Arapiraca: EdUneal, 2015.

- Alagoas. Estudo sobre as Comunidades Indígenas de Alagoas. Maceió, 2017; p 27.

- Segall-Corrêa, A.M.; Marin-León, L.; Melgar-Quiñonez, H.; Pérez-Escamilla, R. Refinement of the Brazilian household food insecurity measurement scale: recommendation for a 14-item EBIA. Revista de Nutrição 2014, 27, 241–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fávaro, T.; Ribas, D.L.B.; Zorzatto, J.R.; Segall-Corrêa, A.M.; Panigassi, G. Segurança alimentar em famílias indígenas terena, Mato Grosso do Sul, Brasil. Cadernos de Saúde Pública 2007, 23, 785–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. The state of food security and nutrition in the world 2019: safeguarding against economic slowdowns and downturns; Food & Agriculture Org.: 2019; Vol. 2019.

- Victora, C.G.; Huttly, S.R.; Fuchs, S.C.; Olinto, M.T. The role of conceptual frameworks in epidemiological analysis: a hierarchical approach. International journal of epidemiology 1997, 26, 224–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brasil. Resolução nº 304 de 09 de agosto de 2000. Aprova Normas para Pesquisas Envolvendo Seres Humanos – Área de Povos Indígenas. Diário Oficial da União 2000.

- Brasil. Resolução Nº 466, de 12 de dezembro de 2012. Aprova diretrizes e normas regulamentadoras de pesquisas envolvendo seres humanos. Diário Oficial da União. 2012.

- Brasil. Resolução Nº 510, de 07 de abril de 2016. Dispõe sobre as normas aplicáveis a pesquisas em Ciências Humanas e Sociais cujos procedimentos metodológicos envolvam a utilização de dados diretamente obtidos com os participantes ou de informações identificáveis ou que possam acarretar riscos maiores do que os existentes na vida cotidiana. Diário Oficial da União 2016.

- Borges, M.F.S.O.; Silva, I.F.d.; Koifman, R. Histórico social, demográfico e de saúde dos povos indígenas do estado do Acre, Brasil. Ciência & Saúde Coletiva 2020, 25, 2237–2246. [Google Scholar]

- Laschefski, K.A.; Zhouri, A. Povos indígenas, comunidades tradicionais e meio ambiente a" questão territorial" e o novo desenvolvimentismo no Brasil. Terra Livre 2019, 1, 278–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baccarin, J.G.; Delgrossi, M.; Magro, J.P. Insegurança Alimentar e Nutricional no Brasil: Tendências e estimativas recentes. Instituto Fome Zero 2024, 26. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2021: Transforming food systems for food security, improved nutrition and affordable healthy diets for all; Food & Agriculture Org.: 2021; Vol. 2021.

- IBGE. Pesquisa de Orçamentos Familiares 2017-2018: Análise da Segurança Alimentar no Brasil. Rio de Janeiro: IBGE, Coordenação de Trabalho e Rendimento, 2020. Availabe online: https://biblioteca.ibge.gov.br/visualizacao/livros/liv101749.pdf (Accessed on September 7th, 2024).

- IBGE. 10,3 milhões de pessoas moram em domicílios com insegurança alimentar grave. Availabe online: https://agenciadenoticias.ibge.gov.br/agencia-noticias/2012-agencia-de-noticias/noticias/28903-10-3-milhoes-de-pessoas-moram-em-domicilios-com-inseguranca-alimentar-grave (accessed on March 30th, 2024).

- Santos, L.A.; Ferreira, A.A.; Pérez-Escamilla, R.; Sabino, L.L.; Oliveira, L.G.; Salles-Costa, R. Interseções de gênero e raça/cor em insegurança alimentar nos domicílios das diferentes regiões do Brasil. Cadernos de Saúde Pública 2023, 38, e00130422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lignani, J.d.B.; Palmeira, P.d.A.; Antunes, M.M.L.; Salles-Costa, R. Relação entre indicadores sociais e insegurança alimentar: uma revisão sistemática. Revista Brasileira de Epidemiologia 2020, 23, e200068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pedraza, D.F. Insegurança alimentar e nutricional de famílias com crianças menores de cinco anos da Região Metropolitana de João Pessoa, Paraíba, Brasil. Ciência & Saúde Coletiva 2021, 26, 1511–1520. [Google Scholar]

- Raupp, L.; Cunha, G.M.; Fávaro, T.R.; Santos, R.V. Condições sanitárias entre domicílios indígenas e não indígenas no Brasil de acordo com os Censos nacionais de 2000 e 2010. Ciência & Saúde Coletiva 2020, 25, 3753–3763. [Google Scholar]

- Raupp, L.; Fávaro, T.R.; Cunha, G.M.; Santos, R.V. Condições de saneamento e desigualdades de cor/raça no Brasil urbano: uma análise com foco na população indígena com base no Censo Demográfico de 2010. Revista Brasileira de Epidemiologia 2017, 20, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coutinho, G.R.; Santos, S.M.C.; Gama, C.M.; Silva, S.O.; Santos, M.E.P.; Silva, N.J. Fatores demográficos e socioambientais associados à insegurança alimentar domiciliar nos diferentes territórios da cidade de Salvador, Bahia, Brasil. Cadernos de Saúde Pública 2022, 38, e00280821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schott, E.; Rezende, F.A.C.; Priore, S.E.; Ribeiro, A.Q.; Franceschini, S.C.C. Fatores associados à insegurança alimentar em domicílios da área urbana do estado do Tocantins, Região Norte do Brasil. Revista Brasileira de Epidemiologia 2020, 23, e200096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares, G.H.; Mota, J.M.S.; Mialhe, F.L.; Biazevic, M.G.H.; Araújo, M.E.; Michel-Crosato, E. Insegurança alimentar domiciliar, cárie dentária e qualidade de vida relacionada à saúde bucal em Indígenas adultos brasileiros. Ciência & Saúde Coletiva 2021, 26, 1489–1500. [Google Scholar]

- Brito, A.P.; Lima, V.N.; Rêgo, A.S.; Dias, L.P.P.; Silva, J.D.; Carvalho, W.R.C.; Barbosa, J.M.A. Fatores associados à Insegurança Alimentar e Nutricional em comunidade carente. Revista Brasileira em Promoção da Saúde 2020, 33, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morais, D.C.; Lopes, S.O.; Priore, S.E. Indicadores de avaliação da Insegurança Alimentar e Nutricional e fatores associados: revisão sistemática. Ciência & Saúde Coletiva 2020, 25, 2687–2700. [Google Scholar]

- Observatório Brasileiro das Desigualdades. Taxa de extrema pobreza no Brasil cai 40% entre 2022 e 2023. Observatório Brasileiro das Desigualdades 2023.

- Ferreira, H.S.; Junior, A.F.S.X.; Assuncao, M.L.; Uchôa, T.C.C.; Lira-Neto, A.B.; Nakano, R.P. Developmental origins of health and disease: a new approach for the identification of adults who suffered undernutrition in early life. Diabetes, metabolic syndrome and obesity: targets and therapy 2018, 543-551.

- Silva, D.A.; Thoma, M.E.; Anderson, E.A.; Kim, J. Infant sex-specific associations between prenatal food insecurity and low birthweight: a multistate analysis. The Journal of Nutrition 2022, 152, 1538–1548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Region | Municipality | Ethnicity | Village |

|---|---|---|---|

| Agreste Region | Traipu | Aconã | Aconã |

| São Sebastião | Karapotó | Fazenda Terra Nova | |

| Plaki-ô | |||

| Campo Grande, Feira Grande |

Tingui-Botó | Tingui-Botó | |

| Olho D’Água do Meio | |||

| Alto Sertão Region | Água Branca | Kalankó | Januária |

| Lajedo do Couro | |||

| Sítio Gregório | |||

| Inhapi | Koiunpanká | Baixa do Galo | |

| Roçado | |||

| Baixa Fresca | |||

| Pariconha | Geripankó | Ouricuri | |

| Figueiredo | |||

| Moxotó | |||

| Serra do Engenho | |||

| Aratikun | |||

| Pariconha | Karuazu | Tanque | |

| Campinhos | |||

| Pariconha | Katokinn | Katokinn | |

| Baixo São Francisco Region | São Brás, Porto Real do Colégio | Kariri-Xokó | Kariri-Xokó |

| Planalto da Borborema Region | Palmeira dos Índios | Xucuru-Kariri | Fazenda do Canto |

| Boqueirão | |||

| Mata da Cafuna | |||

| Cafurna de Baixo | |||

| Serra da Capela | |||

| Serra do Amaro | |||

| Coité | |||

| Riacho Fundo | |||

| Serra dos Quilombos Region | Colônia Leopoldina, Joaquim Gomes, Matriz de Camaragibe, Novo Lino |

Wassú | Cocal |

| TOTAL | 11 | 29 | |

| Variable/Category | Total n (%) |

Presence of FI¹ n (%) |

Crude PR (CI 95%) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | ||||

| Head of Household Gender | ||||

| Male | 705 (55.51) | 177 (25.11) | 1 | - |

| Female | 565 (44.49) | 197 (34.87) | 1.39 (1.17-1.65) | < 0.001 |

| Number of People in the Household | ||||

| ≤ 4 | 960 (75.59) | 271 (28.23) | 1 | - |

| > 4 | 310 (24.41) | 103 (33.23) | 1.18 (0.97-1.41) | 0.088 |

| Socioeconomics | ||||

| Education Level of the Household Head (in completed years of schooling) | ||||

| ≥ 9 | 415 (32.68) | 76 (18.31) | 1 | - |

| 5 a 8 anos | 263 (20.71) | 84 (31.94) | 1.74 (1.33-2.28) | < 0.001 |

| ≤ 4 | 592 (46.61) | 214 (36.15) | 1.97 (1.57-2.48) | < 0.001 |

| Household Head's Employment Conditions | ||||

| Formal employment | 156 (12.31) | 19 (12.18) | 1 | - |

| Informal employment | 472 (37.25) | 126 (26.69) | 2.19 (1.40-3.42) | 0.001 |

| Retired | 296 (23.36) | 96 (32.43) | 2.66 (1.69-4.18) | < 0.001 |

| Unemployed | 343 (27.07) | 132 (38.48) | 3.16 (2.03-4.19) | < 0.001 |

| Total Family Income (in number of national minimum wages) | ||||

| > 2 | 272 (21.42) | 39 (14.34) | 1 | - |

| > 1 a 2 | 443 (34.88) | 128 (28.89) | 2.02 (1.46-2.79) | < 0.001 |

| 0 a 1 | 555 (43.70) | 207 (37.30) | 2.60 (1.91-3.55) | < 0.001 |

| Family receiving assistance from the Bolsa Família Program | ||||

| No | 541 (42.60) | 136 (25.14) | 1 | - |

| Yes | 729 (57.40) | 238 (32.65) | 1.30 (1.08-1.55) | 0.004 |

| Environmental | ||||

| Type of Housing | ||||

| Masonry | 1233 (97.09) | 352 (28.55) | 1 | - |

| Mud/Wood | 37 (2.91) | 22 (59.46) | 2.08 (1.57-2.76) | < 0.001 |

| Number of Rooms in the Household | ||||

| > 4 | 1133(89.21) | 312 (27.54) | 1 | - |

| ≤ 4 | 137 (10.79) | 62 (45.26) | 1.64 (1.34-2.01) | < 0.001 |

| Source of Drinking Water | ||||

| Adequate² | 662 (52.13) | 188 (28.40) | 1 | - |

| Inadequate | 608 (47.87) | 186 (30.59) | 1.08 (0.91-1.28) | 0.392 |

| Garbage Destination | ||||

| Public collection | 1014(79.84) | 287 (28.30) | 1 | - |

| Other³ | 256 (20.16) | 87 (33.98) | 1.20 (0.99-1.46) | 0.069 |

| Sewage Disposal⁴ | ||||

| Adequate | 485 (38.19) | 126 (25.98) | 1 | - |

| Inadequate | 785 (61.81) | 248 (31.59) | 1.22 (1.01-1.46) | 0.035 |

| Variables | Distal Level | Intermediate Level | Proximal Level | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PR (CI 95%) |

p-valor | PR (CI 95%) |

p-valor | PR (CI 95%) |

p-value | |

| Head of Household Gender | ||||||

| Male | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Female | 1.38 (1.16-1.63) |

< 0.001 |

1.44 (1.23-1.71) |

< 0.001 |

1.26 (1.04-1.51) |

0.016 |

| Type of Housing | ||||||

| Masonry | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Mud/Wood | 1.69 (1.25-2.28) |

0.001 |

1.56 (1.13-2.15) |

0.007 |

1.53 (1.12-2.10) |

0.008 |

| Number of Rooms in the Residence | ||||||

| > 4 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| ≤ 4 | 1.47 (1.18-1.84) |

0.001 |

1.48 (1.17-1.86) |

0.001 |

1.29 (1.02-1.63) |

0.031 |

| Garbage Destination | ||||||

| Public collection | 1 | |||||

| Others¹ | 1.10 (0.88-1.36) |

0.397 |

||||

| Sewage Disposal ² | ||||||

| Adequate | 1 | |||||

| Inadequate | 1.14 (0.94-1.37) |

0.174 |

||||

| Number of People in the Household | ||||||

| ≤ 4 | 1 | |||||

| > 4 | 1.15 (0.96-1.38) |

0.133 |

||||

| Education Level of the Household Head (in completed years of schooling) | ||||||

| ≥ 9 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| 5 a 8 | 1.80 (1.38-2.34) |

< 0.001 |

1.55 (1.19-2.01) |

0.001 |

||

| ≤ 4 | 2.02 (1.61-2.53) |

< 0.001 |

1.78 (1.40-2.26) |

< 0.001 |

||

| Household Head's Employment Conditions | ||||||

| Formal employment | 1 | |||||

| Informal employment | 1.43 (0.91-2.22) |

0.112 |

||||

| Retired | 1.73 (1.10-2.73) |

0.018 |

||||

| Unemployed | 1.62 (1.03-2.54) |

0.036 |

||||

| Total Family Income (in number of national minimum wages)3 | ||||||

| > 2 | 1 | |||||

| > 1 a ≤ 2 | 1.69 (1.22-2.33) |

0.001 | ||||

| ≤ 1 | 2.00 (1.44-2.76) |

< 0.001 |

||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).