Submitted:

09 September 2024

Posted:

10 September 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Subjects, Blood Collection, and Processing

2.2. Endogenous DNase Activity Assay

2.3. Specimen Treatment

2.4. DNA Extraction

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

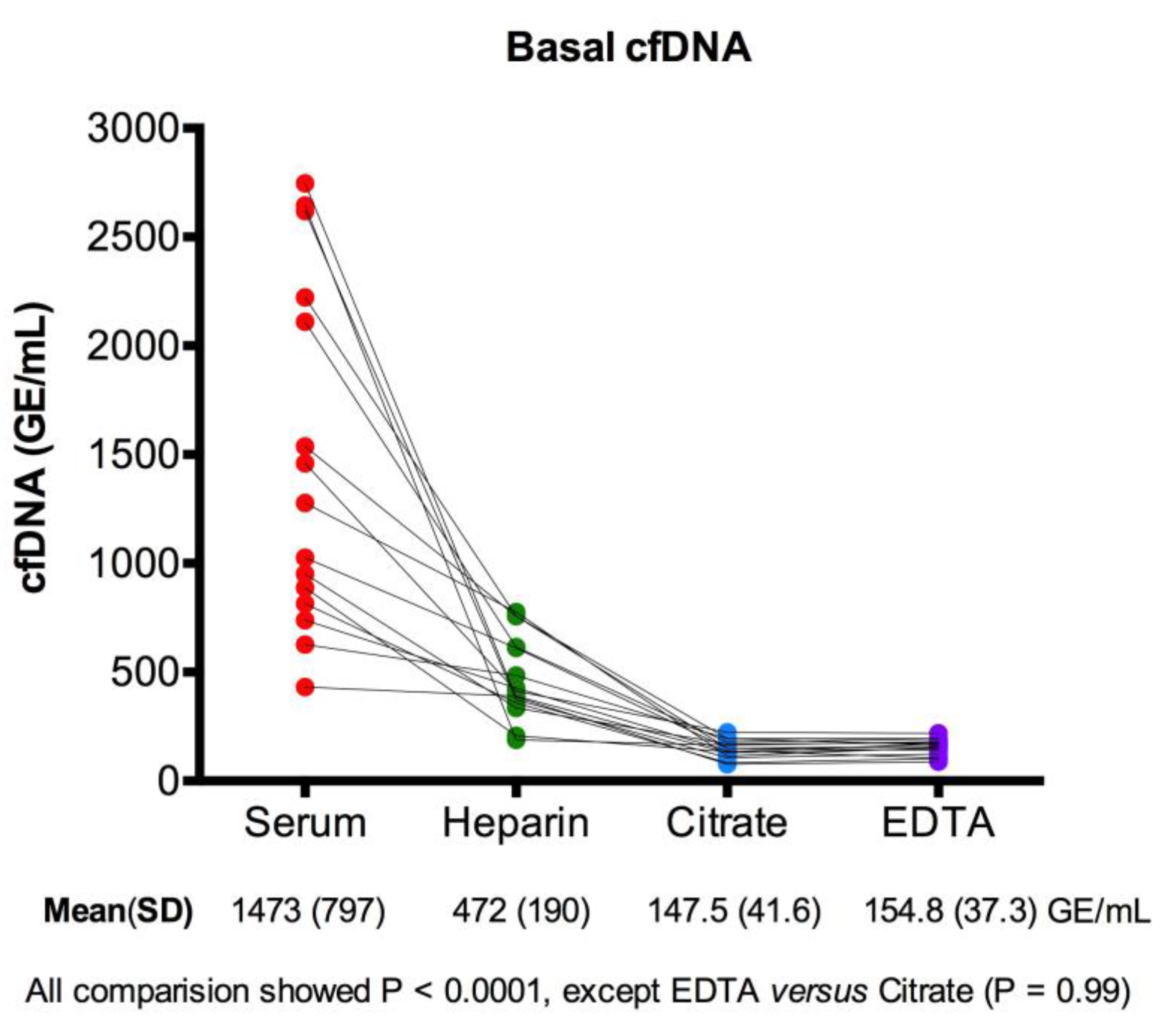

3.1. Basal cfDNA Yields in Serum, Heparin-Plasma, Citrate-Plasma, and EDTA-Plasma

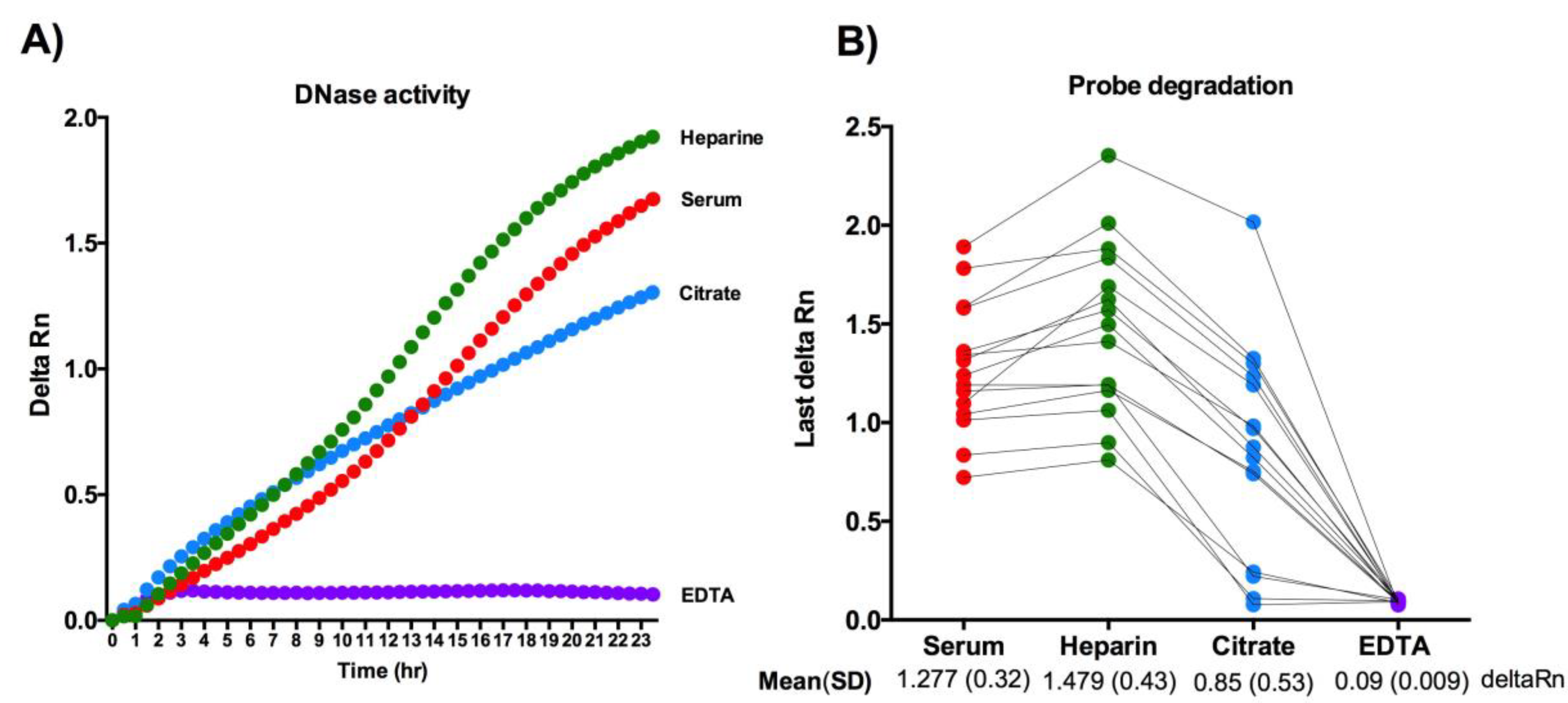

3.2. Direct Measurement of the Endogenous DNase Activity in Serum, Heparin-Plasma, Citrate-Plasma, and EDTA-Plasma

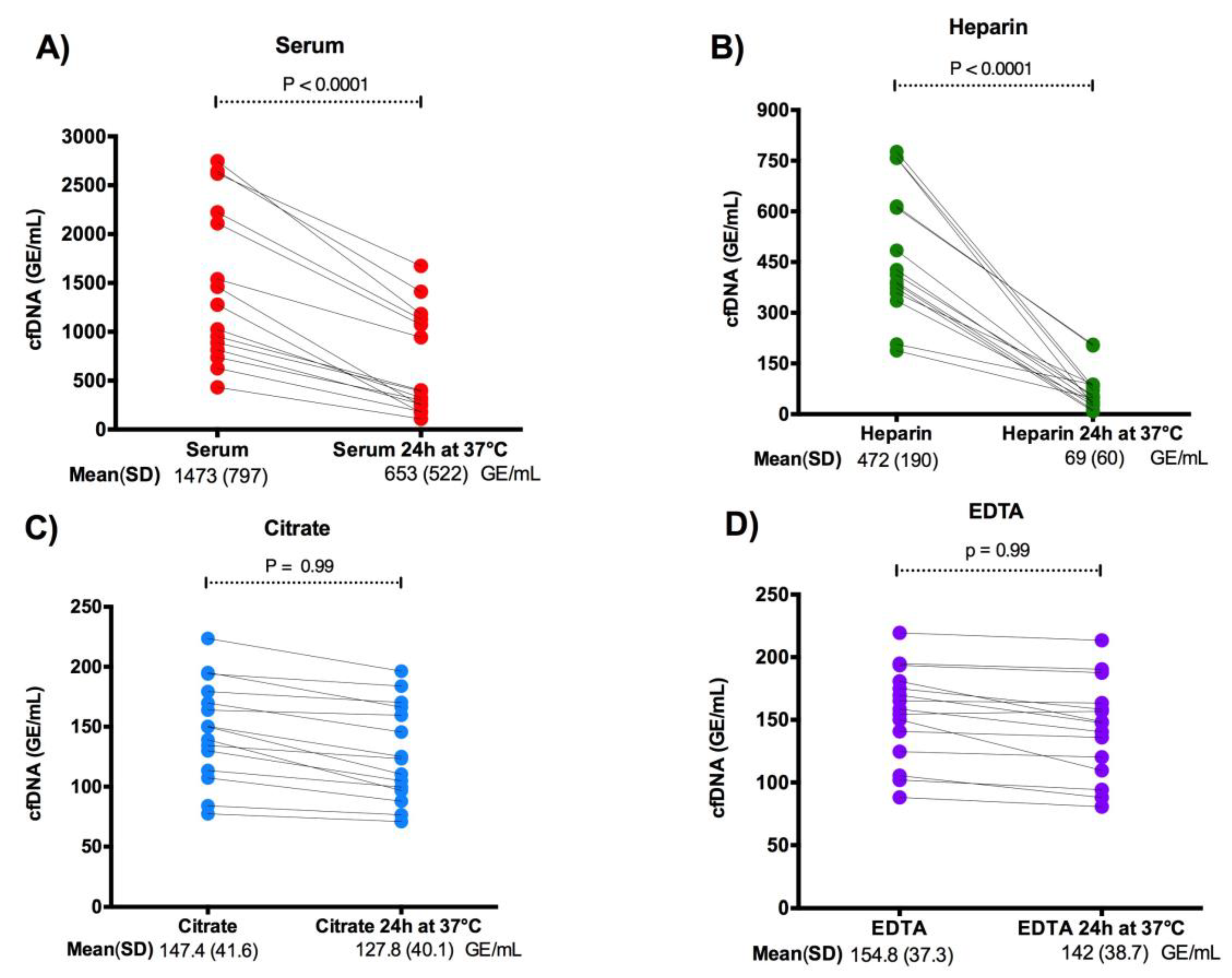

3.3. Effect of Endogenous DNase Activity on cfDNA Levels in Plasma and Serum

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Stewart, C.M.; Kothari, P.D.; Mouliere, F.; Mair, R.; Somnay, S.; Benayed, R.; Zehir, A.; Weigelt, B.; Dawson, S.-J.; Arcila, M.E.; et al. The Value of Cell-Free DNA for Molecular Pathology. J Pathol 2018, 244, 616–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De, S. Signatures Beyond Oncogenic Mutations in Cell-Free DNA Sequencing for Non-Invasive, Early Detection of Cancer. Front Genet 2021, 12, 759832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dudley, J.C.; Diehn, M. Detection and Diagnostic Utilization of Cellular and Cell-Free Tumor DNA. Annu Rev Pathol 2021, 16, 199–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sherwood, K.; Weimer, E.T. Characteristics, Properties, and Potential Applications of Circulating Cell-Free Dna in Clinical Diagnostics: A Focus on Transplantation. J Immunol Methods 2018, 463, 27–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szilágyi, M.; Pös, O.; Márton, É.; Buglyó, G.; Soltész, B.; Keserű, J.; Penyige, A.; Szemes, T.; Nagy, B. Circulating Cell-Free Nucleic Acids: Main Characteristics and Clinical Application. Int J Mol Sci 2020, 21, 6827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, H.; Pan, M.; Zhou, Z.; Chen, C.; Xing, X.; Cheng, S.; Zhang, S.; Zheng, H.; Qian, K. The Impact of Preanalytical Variables on the Analysis of Cell-Free DNA from Blood and Urine Samples. Front Cell Dev Biol 2024, 12, 1385041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ungerer, V.; Bronkhorst, A.J.; Holdenrieder, S. Preanalytical Variables That Affect the Outcome of Cell-Free DNA Measurements. Crit Rev Clin Lab Sci 2020, 57, 484–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medina Diaz, I.; Nocon, A.; Mehnert, D.H.; Fredebohm, J.; Diehl, F.; Holtrup, F. Performance of Streck cfDNA Blood Collection Tubes for Liquid Biopsy Testing. PLoS One 2016, 11, e0166354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barra, G.B.; Santa Rita, T.H.; de Almeida Vasques, J.; Chianca, C.F.; Nery, L.F.A.; Santana Soares Costa, S. EDTA-Mediated Inhibition of DNases Protects Circulating Cell-Free DNA from Ex Vivo Degradation in Blood Samples. Clin Biochem 2015, 48, 976–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toro, P.V.; Erlanger, B.; Beaver, J.A.; Cochran, R.L.; VanDenBerg, D.A.; Yakim, E.; Cravero, K.; Chu, D.; Zabransky, D.J.; Wong, H.Y.; et al. Comparison of Cell Stabilizing Blood Collection Tubes for Circulating Plasma Tumor DNA. Clin Biochem 2015, 48, 993–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, B.; Reinicke, D.; Reindl, I.; Bork, I.; Wollschläger, B.; Lambrecht, N.; Fleischhacker, M. Liquid Biopsy - Performance of the PAXgene® Blood ccfDNA Tubes for the Isolation and Characterization of Cell-Free Plasma DNA from Tumor Patients. Clin Chim Acta 2017, 469, 94–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merker, J.D.; Oxnard, G.R.; Compton, C.; Diehn, M.; Hurley, P.; Lazar, A.J.; Lindeman, N.; Lockwood, C.M.; Rai, A.J.; Schilsky, R.L.; et al. Circulating Tumor DNA Analysis in Patients With Cancer: American Society of Clinical Oncology and College of American Pathologists Joint Review. J Clin Oncol 2018, 36, 1631–1641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, F.C.K.; Sun, K.; Jiang, P.; Cheng, Y.K.Y.; Chan, K.C.A.; Leung, T.Y.; Chiu, R.W.K.; Lo, Y.M.D. Cell-Free DNA in Maternal Plasma and Serum: A Comparison of Quantity, Quality and Tissue Origin Using Genomic and Epigenomic Approaches. Clin Biochem 2016, 49, 1379–1386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vignoli, A.; Tenori, L.; Morsiani, C.; Turano, P.; Capri, M.; Luchinat, C. Serum or Plasma (and Which Plasma), That Is the Question. J Proteome Res 2022, 21, 1061–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayala-Lopez, N.; Conklin, S.E.; Tenney, B.J.; Ness, M.; Marzinke, M.A. Comparative Evaluation of Blood Collection Tubes for Clinical Chemistry Analysis. Clin Chim Acta 2021, 520, 118–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, Y.M.; Tein, M.S.; Lau, T.K.; Haines, C.J.; Leung, T.N.; Poon, P.M.; Wainscoat, J.S.; Johnson, P.J.; Chang, A.M.; Hjelm, N.M. Quantitative Analysis of Fetal DNA in Maternal Plasma and Serum: Implications for Noninvasive Prenatal Diagnosis. Am J Hum Genet 1998, 62, 768–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bustin, S.A.; Benes, V.; Garson, J.A.; Hellemans, J.; Huggett, J.; Kubista, M.; Mueller, R.; Nolan, T.; Pfaffl, M.W.; Shipley, G.L.; et al. The MIQE Guidelines: Minimum Information for Publication of Quantitative Real-Time PCR Experiments. Clin Chem 2009, 55, 611–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivancic-Jelecki, J.; Brgles, M.; Santak, M.; Forcic, D. Isolation of Cell-Free DNA from Plasma by Chromatography on Short Monolithic Columns and Quantification of Non-Apoptotic Fragments by Real-Time Polymerase Chain Reaction. J Chromatogr A 2009, 1216, 2717–2724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima-Oliveira, G.; Brennan-Bourdon, L.M.; Varela, B.; Arredondo, M.E.; Aranda, E.; Flores, S.; Ochoa, P. Clot Activators and Anticoagulant Additives for Blood Collection. A Critical Review on Behalf of COLABIOCLI WG-PRE-LATAM. Crit Rev Clin Lab Sci 2021, 58, 207–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adachi, I.; Iwaki, H.; Adachi, H.; Ueno, M.; Horikoshi, I. Heparin-Induced Leukocyte Lysis in Vitro. J Pharmacobiodyn 1986, 9, 207–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lelliott, P.M.; Momota, M.; Shibahara, T.; Lee, M.S.J.; Smith, N.I.; Ishii, K.J.; Coban, C. Heparin Induces Neutrophil Elastase-Dependent Vital and Lytic NET Formation. Int Immunol 2020, 32, 359–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Z.; Fasco, M.J.; Kaminsky, L.S. Optimization of Dnase I Removal of Contaminating DNA from RNA for Use in Quantitative RNA-PCR. Biotechniques 1996, 20, 1012–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guéroult, M.; Picot, D.; Abi-Ghanem, J.; Hartmann, B.; Baaden, M. How Cations Can Assist DNase I in DNA Binding and Hydrolysis. PLoS Comput Biol 2010, 6, e1001000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barra, G. Blood Nucleases Affecting Circulating DNA in Serum and Plasma. In Cell-Free Circulating DNA; WORLD SCIENTIFIC, 2022; pp. 175–208 ISBN 9789811244674.

- Barra, G.B.; Santa Rita, T.H.; Jácomo, R.H.; Nery, L.F.A. Sodium Citrate at 8% Is Equivalent to EDTA as Anticoagulant of Choice for Circulation Cell-Free DNA Analysis: Low Contamination by Blood Cells Genomic DNA and Inhibition of Blood Nulcease Activity. In Proceedings of the Clinical Chemistry; Chicago, July 6 2014; Vol. 60, p. S190.

- Sato, A.; Nakashima, C.; Abe, T.; Kato, J.; Hirai, M.; Nakamura, T.; Komiya, K.; Kimura, S.; Sueoka, E.; Sueoka-Aragane, N. Investigation of Appropriate Pre-Analytical Procedure for Circulating Free DNA from Liquid Biopsy. Oncotarget 2018, 9, 31904–31914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dinsdale, R.J.; Hazeldine, J.; Al Tarrah, K.; Hampson, P.; Devi, A.; Ermogenous, C.; Bamford, A.L.; Bishop, J.; Watts, S.; Kirkman, E.; et al. Dysregulation of the Actin Scavenging System and Inhibition of DNase Activity Following Severe Thermal Injury. Br J Surg 2020, 107, 391–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Vries, J.C.; Barendrecht, A.D.; Clark, C.C.; Urbanus, R.T.; Boross, P.; de Maat, S.; Maas, C. Heparin Forms Polymers with Cell-Free DNA Which Elongate Under Shear in Flowing Blood. Sci Rep 2019, 9, 18316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohrabipour, S.; Muniz, V.S.; Sharma, N.; Dwivedi, D.J.; Liaw, P.C. Mechanistic Studies of DNase I Activity: Impact of Heparin Variants and PAD4. Shock 2021, 56, 975–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holodniy, M.; Kim, S.; Katzenstein, D.; Konrad, M.; Groves, E.; Merigan, T.C. Inhibition of Human Immunodeficiency Virus Gene Amplification by Heparin. J Clin Microbiol 1991, 29, 676–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sefrioui, D.; Beaussire, L.; Clatot, F.; Delacour, J.; Perdrix, A.; Frebourg, T.; Michel, P.; Di Fiore, F.; Sarafan-Vasseur, N. Heparinase Enables Reliable Quantification of Circulating Tumor DNA from Heparinized Plasma Samples by Droplet Digital PCR. Clin Chim Acta 2017, 472, 75–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, N.; Sasaki, A.; Mikami, M.; Nishiyama, M.; Akaishi, R.; Wada, S.; Ozawa, N.; Sago, H. Nonreportable Rates and Cell-Free DNA Profiles in Noninvasive Prenatal Testing among Women with Heparin Treatment. Prenat Diagn 2020, 40, 838–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wardrop, J.; Dharajiya, N.; Boomer, T.; McCullough, R.; Monroe, T.; Khanna, A. Low Molecular Weight Heparin and Noninvasive Prenatal Testing [22C]. Obstetrics & Gynecology 2016, 127, 32S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nitsche, J.F.; Lovell, D.; Stephens, N.; Conrad, S.; Bebeau, K.; Brost, B.C. The Effects of Heparin, Aspirin, and Maternal Clinical Factors on the Rate of Nonreportable Cell-Free DNA Results: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Am J Obstet Gynecol MFM 2023, 5, 100846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wardrop, J.; Dharajiya, N.; Boomer, T.; McCullough, R.; Monroe, T.; Khanna, A. Low Molecular Weight Heparin and Noninvasive Prenatal Testing [22C]. Obstetrics & Gynecology 2016, 127, 32S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nitsche, J.F.; Lovell, D.; Stephens, N.; Conrad, S.; Bebeau, K.; Brost, B.C. The Effects of Heparin, Aspirin, and Maternal Clinical Factors on the Rate of Nonreportable Cell-Free DNA Results: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Am J Obstet Gynecol MFM 2023, 5, 100846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).