1. Introduction

1.1. Pain in the Face, Head and Neck

The assessment and treatment of chronic pain arising from facial, head, and anterior cervical structures is particularly challenging; this can be explained by the multiple possible sources of pain and their complex neural interconnexions. The complexity of managing chronic pain in these patients is matched by its broad range of differential diagnoses that must be considered, including cranio-mandibular disorders, headaches, facial neuralgias, and head and neck cancers[

1].A multidisciplinary approach to assess and manage these chronic pain syndromes may facilitate an accurate diagnostic and successful selection of analgesic treatment.

1.2. Anesthetic Blocks for Chronic Pain Management

Despite clinical recommendations, the mainstream management of chronic pain remains centered around long-term pharmacological options, including opioids. In these cases, guidelines emphasize the necessity of a multidisciplinary approach to assessment and management in order to achieve better outcomes and prevent adverse consequences owing to the prolonged use of systemic medication[

2].

Among the recommended opioid-sparing multidisciplinary approaches, interventional pain procedures may be considered in cases when the pain is restricted to a confined anatomical area potentially innervated by a few well identifiable nerve structures. Regional blocks can be effective in the management of pain because they interrupt nociceptive flow from its source, hence helping not only with the diagnosis, but also the management of this pain[

3]

.The superficial cervical plexus block (SCPB) is a relatively simple anesthetic technique used in various head and neck surgeries that interrupts the sensory message from selected anatomical areas of the face, the head and the anterior aspect of the neck[

4]. Its indications and effectiveness for the management of chronic pain are poorly described.

1.2. Purpose of This Study

The purpose of our study was to present a cohesive analysis combining our clinical experience with the SCPB in chronic pain management and a narrative review of existing literature on the topic. We aimed to integrate our own clinical findings with a comprehensive review of scientific data regarding the indications and outcomes of SCPB for pain management, offering a more thorough understanding of SCPB’s effectiveness and applications.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Literature Review

We conducted an exhaustive literature search in PubMed, Scopus, and Embase (Elsevier) for articles and reviews published in English with the following keywords: “pain”, “chronic pain”, “acute pain”, “head and neck pain”, “cancer pain”, “interventional pain”, “pain management” and “superficial cervical plexus block”.

2.2. Case Series

2.2.1. Patient Population and Data Collection

Our institution's ethics board approved this research, which is a retrospective chart review conducted at a single center by a single physician. The study involves patients from the Alan Edwards Pain Management Unit and the Cancer Pain Clinic at McGill University Health Centre who received one or more SCPBs for managing their chronic pain

The charts analyzed were selected from the interventional list of the attending physician (JP) who performed these procedures. The cases included patients who received an SCPB for chronic pain management since 2020.

Data collected from patients’ electronic medical records included sex and age, pain diagnosis, pre-procedure pain severity, pharmacological analgesic modalities, block specifics, complications, perceived benefits, post-block treatment modalities. We also documented the need for repeated blocks.

2.2.2. Superficial Cervical Plexus Block Technique

All procedures were performed in our institution’s interventional rooms and all patients were discharged home after their procedure. Before a block, patients were briefly interviewed to review their case, re-explain the procedure, address questions and obtain written informed consent. The technique was done under sterile conditions with ultrasound (US) guidance and the patients laying in a lateral decubitus or supine position, fully monitored (a more detailed description of the block technique is provided in the brief narrative review below).

3. Brief Narrative Literature Review

3.1. Anatomical Description

The cervical nerve plexus originates from the ventral rami of nerve roots C1 to C4 to produce deep and superficial branches. Deep muscular branches supply the infra-hyoid and sub-occipital muscles of the neck as well as the diaphragm through the phrenic nerve. The superficial (or cutaneous) branches split off externally to the prevertebral fascia [

4]; to emerge near the midpoint of the posterior border of the sternocleidomastoid muscle (SCM) and fan out into 4 individual nerves. The first and most rostral is the lesser occipital nerve (LON) supplying the skin of the upper neck and retro-auricular scalp. The great auricular nerve (GAN) supplies the ante-auricular lateral aspect of the face. The transverse cervical nerve (TCN) supplies the skin of the anterior triangle of the neck. The supraclavicular nerve (SCN) supplies the skin over the clavicle, as well as the lateral neck, the shoulder and the upper pectoral region [

5].

3.2. Indications for SCPB for Acute and Chronic Pain

The superficial cervical plexus block (SCPB) is a commonly performed anesthetic technique for surgical procedures such as carotid endarterectomies, thyroidectomies, parathyroidectomies and clavicle fracture repairs [

6,

7,

8]. However, the usage and effectiveness of SCPB in the context of pain management has almost exclusively been reported in case reports and short case-series.

For the sole purpose of pain relief, our literature review found that the SCPB seems to mostly be performed in the emergency department and the most frequent indication for this procedure is the management of acute clavicular fracture pain [

9,

10,

11]. Other conditions that have benefitted from the SCPB in an emergent context include paracervical muscle spasms, rotator cuff injuries, acromioclavicular joint separations, radicular or neuropathic neck pain as well as acute herpes zoster pain [

9,

12,

13,

14].

For the management of chronic pain, the indications found in the literature include chronic post-whiplash headaches, post-herpetic neuralgia as well as referred somatic cervical pain [

15,

16,

17,

18]. Other possible indications for SCPB for chronic pain management are not well-documented. However, it is worth noting that the block and neurolysis of selected terminal branches of the SCP, specifically the LON and the GAN, have been thoroughly described[

19,

20].

In the context of cancer-related procedures, the use of the SCPB has shown promise in various surgical interventions, including unilateral thyroid lobectomies and tracheal dissections for thyroid cancer, as well as mastectomies for breast cancer; its application has demonstrated effectiveness in reducing the need for post-operative analgesia and enhancing the quality of recovery[

21,

22,

23]. However, the literature on the use of SCPB for chronic, cancer-related pain is notably limited. One case report by Kim H.

et al. describes the usage of the SCPB in the relief of a brain cancer metastasis-related cervicogenic headache; in this case, the mass was situated in the left anterior neck and, after the procedure, this patient’s pain subsided for a week before there was a need for an additional block[

24]. Additionally, in a study by Nasir

et al., a cohort of patients with head and neck cancer who presented with neuropathic pain arising from the three trigeminal nerve divisions or from the SCP received interventional treatments (such as trigeminal blocks or SCPBs); the authors reported successful pain management in 85% of these cases[

25].

3.3. Technical Description

The patient lies either on a lateral decubitus or supine with the head turned contralateral to the side of the block. Due to the vital importance of neighboring anatomical structures, it is recommended US guidance to identify the target, navigate the needle and control the spread of the injectate [

4,

6]. It is worth noting that studies have shown that there is no significant difference in success rate between landmark-based and US-guided techniques in terms of short-term anesthetic results [

26]. However, in the field of interventional pain medicine, authors recommend US guidance to increase anatomical accuracy by using the least amount of local anesthetics[

4,

6].

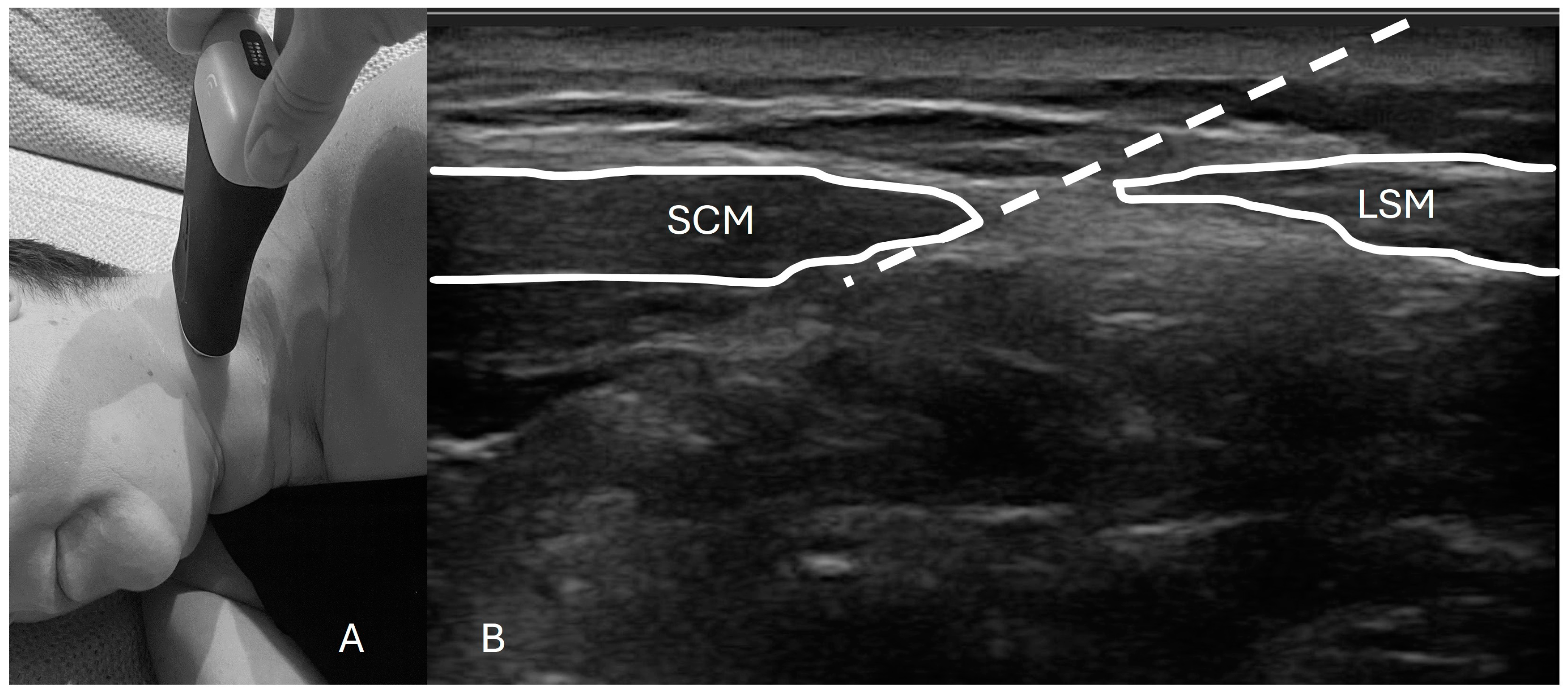

To perform this technique, one must first identify the posterior border of the sternocleidomastoid (SCM) muscle extending from the mastoid process (most cranial insertion of the SCM) all the way down to the lateral projection of the C6 vertebrae. The US probe should provide an axial cut of the neck at the midpoint of the line of the SCM to a height close to the cricoid cartilage. With an “in-plane” approach, the needle is inserted and lands no more than 1 to 2 cm antero-medially under the SCM (

Figure 1). After negative aspiration, a volume of local anesthetics is deployed underneath the SCM anterior to the levator scapulae muscle while being careful not to pierce through the prevertebral fascia[

4,

6].

Figure 1 shows an example of a typical setup for this procedure.

Our literature review found that the most commonly used local anesthetic was bupivacaine at various concentrations (0.25 and 0.5%) [

4,

9,

10,

11,

15]; ropivacaine and levobupivacaine are also used[

4,

12,

16,

17]. Some authors even utilize lidocaine despite its theoretically short-lasting effects[

13,

14,

15]. In some cases, adjuvants were added to prolong the effect, such as epinephrine, triamcinolone and methylprednisolone [

9,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17]. Regardless of the type of local anesthetic used, the vast majority of volumes injected seem to vary between 5 to 10 mL, with only very few cases of injecting slightly less than 5 mL or between 10 and 15 mL[

4,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

15,

16,

17].

3.4. Contraindications, Side Effects and Potential Complications

The are very few specific contraindications for the SCPB. The most frequently mentioned ones concern either patients with paralysis of the contralateral phrenic nerve and diaphragm, patients with previous neck procedures including surgery or radiation or patients with an infection at the planned injection site[

4,

6].

The potential complications associated with the SCPB procedure are also relatively infrequent. Most of the reported complications can be attributed to the spread of the injectate into deep cervical plexuses and surrounding nerves. Paralysis of the ipsilateral phrenic nerve is the one most commonly reported[

4]. There is also a possibility of recurrent laryngeal nerve paresis, deep cervical and even brachial plexus blockade as well as accessory nerve dysfunction, all of which can cause weakness in the associated muscles[

6]. There is one case report of temporary ipsilateral Horner’s syndrome after an SCPB that self-resolved after 90 minutes; in this report, some basic recommendations were suggested to avoid complications such as limiting the anesthetic volumes while ensuring appropriate needle placement and avoiding excessively deep needle insertion[

11].

US-guided techniques represent a more secure option than the landmark-guided intervention if the goal is to avoid complications, especially if the physician is less familiar with the procedure. Other potential complications include infection, hematoma, accidental jugular vein or carotid artery puncture as well as local anesthetic systemic toxicity if the anesthetic enters the bloodstream[

6].

4. Clinical Results

4.1. Overview

Fourteen charts were identified for further analysis. Demographic data, diagnosis and details about the cases and the procedures can be found in

Table 1 and

Table 2. 43% of our patients received a SCPB for the treatment of chronic pain caused by head and neck cancer or its treatment.

4.2. Case Characteristics

4.2.1. Pain Distribution and Intensity

The pain distribution of patients undergoing the procedure corresponded to one or more of the four superficial branches of the SCP: the great auricular nerve (GAN), lesser occipital nerve (LON), transverse cervical nerve (TCN), and supraclavicular nerve (SCN). A description of the anatomical areas supplied by each of these nerves is available in the literature review above. Among the patients treated, the most targeted areas were the ones supplied by the TCN (8 cases) and the GAN (7 cases). The least commonly targeted areas were the ones supplied by the LON (2 cases) and the SCN (2 cases).

Among patients with cancer-related pain, the most frequent painful area was the one supplied by the TCN (5 out of 6 cases). In contrast, among non-cancer patients, the most frequent painful area was the one supplied by the GAN (4 out of 8 cases).

All patients reported at least moderate baseline pain on a scale including the options of no pain, mild pain, moderate pain or severe pain; this equates to a score over 4 out of 10 on a numerical rating scale.

4.2.2. Procedure Specifics

The main local anesthetic used was bupivacaine (10/14 cases) and the most frequent volume used was 5 mL (11/14 cases), which is on the lower end of the usual volume range used for this type of procedure.

4.2.3. Outcomes

After the procedure, two patients from the non-cancer pain clinic were lost to follow-up; for analytical purposes, these cases were considered negative outcomes. Additionally, two other patients—one from the cancer pain clinic and one from the non-cancer pain clinic—reported a lack of effect and the procedure was deemed to have failed. Overall, 10 of the 14 cases (71%) reported satisfactory pain relief at their follow-up visit, with these outcomes being equally distributed between the cancer clinic and the non-cancer clinic patients. There was no meaningful difference between the targeted nerve in successful cases versus those that failed. 4 cases among the 10 that reported successful pain relief requested repeated procedures. No immediate or long-term complications were documented for any of our cases.

Of the total 12 patients that were not lost to follow-up, 6 people saw their pharmacological treatments after the block remain unchanged, while 3 saw the intensity of their analgesic treatment decrease and 3 others saw it increase. Specifically, out of the 10 participants reporting positive outcomes, the post-block pharmacological treatment decreased in 3, decreased in 3 and remained unchanged in 4 participants.

5. Discussion

This retrospective study examines a small clinical sample of patients undergoing a specific interventional technique for managing chronic pain of various etiologies. Although the preliminary results suggest apparent efficacy and safety, the research lacks sufficient rigor to provide robust scientific evidence. The study has several weaknesses: the sample size is too small to draw reliable analytical conclusions; data were collected retrospectively from patient charts, raising concerns about data accuracy and interpretation; outcomes were not compared to a control group that did not receive the procedure, making it difficult to assess whether SCPB is more effective than alternative treatments; and the data only offers a snapshot of outcomes immediately or shortly after the procedure, with no information on the long-term duration and quality of the analgesic effect.

Although it is difficult to make any meaningful conclusions from our data, this research remains valuable for several reasons. First, the technique is both easy to perform and safe. Second, interventional options serve as valid adjuncts for managing particularly challenging, drug-resistant chronic pain syndromes. Lastly, addressing drug-resistant cancer pain requires exploring any available effective alternatives to achieve effective and prolonged pain relief.

It is important to highlight the value of minimally invasive interventional techniques as adjuvants to multidisciplinary pain strategies. In patients presenting with cancer-related symptoms, the negative impact that pain can have on patient’s quality of life and even their overall survival is well documented[

27].

The SCPB for chronic pain management can be performed as an outpatient procedure, requiring only a short period of post-procedural observation. This block can be carried out in any clinical setting, provided that basic safety precautions are followed to ensure the well-being and comfort of both patients and clinicians. The necessary equipment is relatively ubiquitous and inexpensive, including basic sterile materials, local anesthetics, and a portable ultrasound scanner.

Patients often experience immediate pain relief from the SCPB, which confirms the procedure’s effectiveness and helps to reassure them that the targeted nerve plays a role in their chronic pain. This quick relief can also boost their overall confidence in the treatment, potentially enhancing their perception of its benefits, especially in the case of repeated block administrations. As a result, many patients choose to reduce or stop using other systemic pain medications. The reduction in medication and the decrease in pain contribute to a better overall quality of life and greater satisfaction with the treatment.

In conclusion, while this article does not significantly strengthen the scientific evidence supporting the use of SCPB for chronic pain management, it does show that the procedure was safe and effective for our specific group of patients with moderate to severe pain. To further validate our hypothesis that the SCPB may be a viable and potentially superior alternative to systemic medications for managing severe, drug-resistant pain in the anterior neck and head—particularly in patients with chronic conditions such as cancer—more rigorous, comparative studies are needed.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.Z. and J.P.; methodology, J.Z. and J.P.; validation, J.Z. and J.P..; formal analysis, J.Z.; investigation, J.Z.; data curation, J.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, J.Z.; writing—review and editing, J.Z. and J.P.; visualization, J.Z.; supervision, J.P.; project administration, J.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Ethics Committee of the McGill University Health Centre Research Institute or MUHC-RI (protocol code 2024-7388).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author due to patient privacy concerns.

Acknowledgments

The clinical, academic and research activities of the Pain Department with the McGill University Health Centre are generously supported by the Louise and Alan Edward Foundation.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Cooper BC, Cooper DL. Multidisciplinary approach to the differential diagnosis of facial, head and neck pain. J Prosthet Dent. Jul 1991;66(1):72-8. [CrossRef]

- The Lancet Regional H-A. Opioid crisis: addiction, overprescription, and insufficient primary prevention. Lancet Reg Health Am. Jul 2023;23:100557. [CrossRef]

- Mehio AK, Shah SK. Alleviating head and neck pain. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. Feb 2009;42(1):143-59, x. [CrossRef]

- Sarkar AK, O’Connor CM, Goldstein RB. Superficial Cervical Plexus Nerve Block. Bedside Pain Management Interventions. 2022:271-279:chap Chapter 29.

- Glenesk NL, Kortz MW, Lopez PP. Anatomy, Head and Neck, Posterior Cervical Nerve Plexus. StatPearls. 2023.

- Hipskind JE, Ahmed AA. Cervical Plexus Block. StatPearls. 2023.

- Woldegerima YB, Hailekiros AG, Fitiwi GL. The analgesic efficacy of bilateral superficial cervical plexus block for thyroid surgery under general anesthesia: a prospective cohort study. BMC Res Notes. Jan 28 2020;13(1):42. [CrossRef]

- Baran O, Kir B, Ates I, Sahin A, Uzturk A. Combined supraclavicular and superficial cervical plexus block for clavicle surgery. Korean J Anesthesiol. Feb 2020;73(1):67-70. [CrossRef]

- Ho B, De Paoli M. Use of Ultrasound-Guided Superficial Cervical Plexus Block for Pain Management in the Emergency Department. J Emerg Med. Jul 2018;55(1):87-95. [CrossRef]

- Herring AA, Stone MB, Frenkel O, Chipman A, Nagdev AD. The ultrasound-guided superficial cervical plexus block for anesthesia and analgesia in emergency care settings. Am J Emerg Med. Sep 2012;30(7):1263-7. [CrossRef]

- Flores S, Riguzzi C, Herring AA, Nagdev A. Horner's Syndrome after Superficial Cervical Plexus Block. West J Emerg Med. May 2015;16(3):428-31. [CrossRef]

- Shin HY, Kim DS, Kim SS. Superficial cervical plexus block for management of herpes zoster neuralgia in the C3 dermatome: a case report. J Med Case Rep. Feb 19 2014;8:59. [CrossRef]

- Lee H, Jeon Y. Treatment of herpes zoster with ultrasound-guided superficial cervical plexus block. J Dent Anesth Pain Med. Dec 2015;15(4):247-249. [CrossRef]

- Park KB. Superficial Cervical Plexus Block for Acute Herpes Zoster at C3-4 Dermatome. Keimyung Med J. 12 2015;34(2):152-156.

- James A, Niraj G. Intermediate Cervical Plexus Block: A Novel Intervention in the Management of Refractory Chronic Neck and Upper Back Pain Following Whiplash Injury: A Case Report. A A Pract. Apr 2020;14(6):e01197. [CrossRef]

- Thapa D, Ahuja V, Dhiman D. Role of superficial cervical plexus block in somatic referred cervical spine pain. Indian J Anaesth. Dec 2017;61(12):1012-1014. [CrossRef]

- Roelands S, Lebrun C, Soetens F. Ultrasound-guided superficial cervical plexus block in the treatment of post-herpetic neuralgia. Pain Pract. Mar 2022;22(3):414-415. [CrossRef]

- Niraj G. Intermediate cervical plexus block in the management of treatment resistant chronic cluster headache following whiplash trauma in three patients: a case series. Scand J Pain. Jan 27 2023;23(1):208-212. [CrossRef]

- Rawner E, Irwin DM, Trescot AM. Lesser Occipital Nerve Entrapment. Peripheral Nerve Entrapments. 2016:149-158:chap Chapter 18.

- Benton L, Trescot AM. Great Auricular/Posterior Auricular Nerve Entrapment. Peripheral Nerve Entrapments. 2016:117-126:chap Chapter 16.

- Yao Y, Lin C, He Q, Gao H, Jin L, Zheng X. Ultrasound-guided bilateral superficial cervical plexus blocks enhance the quality of recovery in patients undergoing thyroid cancer surgery: A randomized controlled trial. J Clin Anesth. May 2020;61:109651. [CrossRef]

- Cho AR, Kim HK, Lee EA, Lee DH. Airway management in a patient with severe tracheal stenosis: bilateral superficial cervical plexus block with dexmedetomidine sedation. J Anesth. Apr 2015;29(2):292-4. [CrossRef]

- Li NL, Yu BL, Hung CF. Paravertebral Block Plus Thoracic Wall Block versus Paravertebral Block Alone for Analgesia of Modified Radical Mastectomy: A Retrospective Cohort Study. PLoS One. 2016;11(11):e0166227. [CrossRef]

- Kim HH, Kim YC, Park YH, et al. Cervicogenic headache arising from hidden metastasis to cervical lymph node adjacent to the superficial cervical plexus -A case report. Korean J Anesthesiol. Feb 2011;60(2):134-7. [CrossRef]

- Nasir KS, Hafeez H, Jamshed A, Hussain RT. Effectiveness of Nerve Blocks for the Management of Head and Neck Cancer Associated Neuropathic Pain Disorders; a Retrospective Study. J Cancer Allied Spec. 2020;6(2):e367. [CrossRef]

- Tran DQ, Dugani S, Finlayson RJ. A randomized comparison between ultrasound-guided and landmark-based superficial cervical plexus block. Reg Anesth Pain Med. Nov-Dec 2010;35(6):539-43. [CrossRef]

- Zylla D, Steele G, Gupta P. A systematic review of the impact of pain on overall survival in patients with cancer. Support Care Cancer. May 2017;25(5):1687-1698. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).