1. Introduction

Freudenberger first described the term burnout in 1981 as a process characterized by losing energy and feeling overwhelmed due to an individual’s dedication to completing a task or job. This phenomenon can impact a person’s attitude, perception, and judgment.[

1] Symptoms vary from physical to mental to emotional, altering the person’s behavior.

Currently, the World Health Organization defines burnout as an occupational phenomenon rather than a medical condition, and it includes it in the 11th revision of the International Classification of Diseases.[

2] The three main dimensions that characterize this phenomenon are the feelings of exhaustion, negativism, or cynicism related to the job and the lack of professional efficacy[

3] (

Figure 1). Several different tools have been designed to measure these dimensions, but the Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI) is the gold standard for assessing burnout[

2,

4]. This 22-item tool evaluates the feelings or emotions of the participant on a 7-point Likert scale. Still, two determining questions related to emotional exhaustion and depersonalization exhibit the highest factor able to predict the risk of burnout in medical professionals.[

5,

6,

7]

The Medscape Lifestyle Report registered a 51% burnout rate among physicians in the United States in 2017.[

8] In 2018, the prevalence of burnout in U.S. nurses was 31.5%.[

9] The 2021 Medscape National Physicians Burnout and Suicide Report stated that burnout is still at critical levels compared to the previous year, with 42% of 12.000 US physicians feeling burnout and 13% having suicidal thoughts.[

10,

11] Evidence shows these rates increased, especially after the COVID-19 pandemic. This increase is directly related to the enormous workload and stressful situations that healthcare providers have been subjected to, leading to a higher risk of burnout.[

12,

13]

Fortunately, the use of telemedicine has helped mitigate these adverse effects. For example, recent research about telemedicine during the COVID-19 pandemic has reported a decrease in burnout symptoms in one-third of the responding physicians.[

14]

Advanced Care at Home (ACH) is a new program offered by the Mayo Clinic that provides high-quality healthcare technology to patients in the comfort of their homes. Since the well-being of healthcare workers is an essential key to delivering high-quality patient care,[

15] we hypothesize that providers who supply care to patients from the ACH program exhibit lower levels of burnout. Therefore, this study aimed to determine the levels of burnout in the physicians and nurse practitioners working with ACH by analyzing the outcomes obtained from a quarterly survey applied during the first three quarters of the program.

2. Methods

All the providers (physicians and nurse practitioners) working in ACH at Mayo Clinic were asked to voluntarily complete a 16-question anonymous survey distributed via email every 3 to 4 months since the program started. The survey was not focused on evaluating the risk of burnout; instead, it contained questions using Likert-like scale choices relating to the overall experience working with ACH (

Table 1).

Considering the paper published by West et al.[

5] in 2009, a single item from the MBI can be utilized to stratify the risk when the entire survey cannot be applied, but its combination with other factors allows for a comprehensive evaluation of the participants. (

Table 2) Therefore, we selected ten questions from the original survey that evaluated the three dimensions that define burnout according to our criteria (

Table 3).

The single-question assessment for emotional exhaustion (“I feel burned out from my work”) supported by West et al.[

5] was selected as the question derived from MBI (

Table 2). The answer options included: (1) strongly agree, (2) somewhat agree, (3) neither agree nor disagree, (4) somewhat disagree, (5) strongly disagree, or (1) always, (2) most of the time, (3) about half the time, (4) sometimes, (5) never. Incomplete surveys were excluded. The data collected was analyzed using frequency distribution and percentages.

3. Results

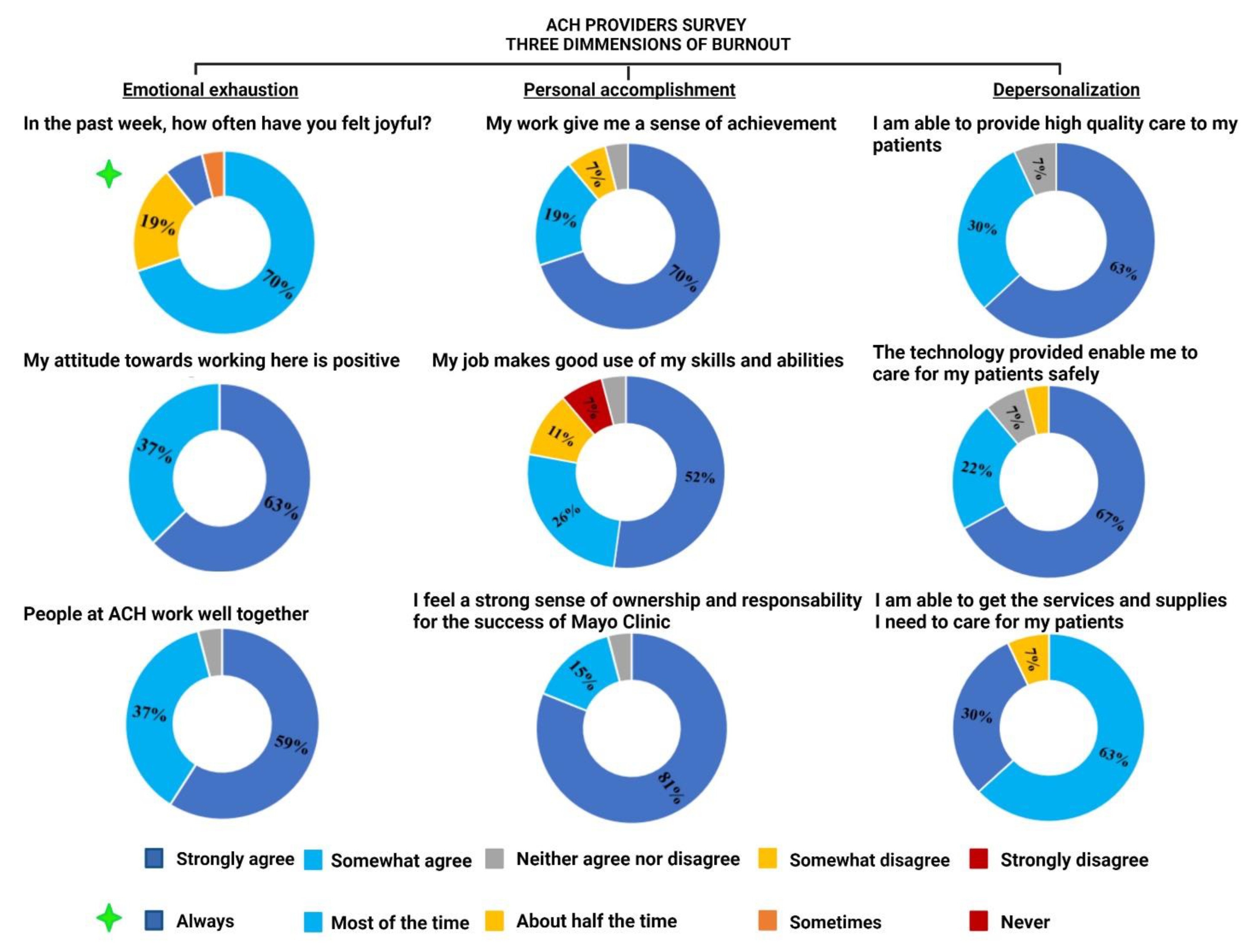

From July 2020 to April 2021, three quarterly surveys were sent to the ACH providers. A total of 27 providers, including both physicians and nurse practitioners, answered it. The response rate reported in the first, second, and third quarters was 38%, 23%, and 66%, respectively. The answers compiled over the three quarters showed that out of the ten questions selected to evaluate the likelihood of burnout in the participants, nine were answered satisfactorily with “strongly agree” or “somewhat agree” by more than 75% of the providers, as shown in

Figure 2.

The unique question with different answer options measured how often the participants felt joyful in the week before the survey was applied, and 77% of them stated “always” or “most of the time.”

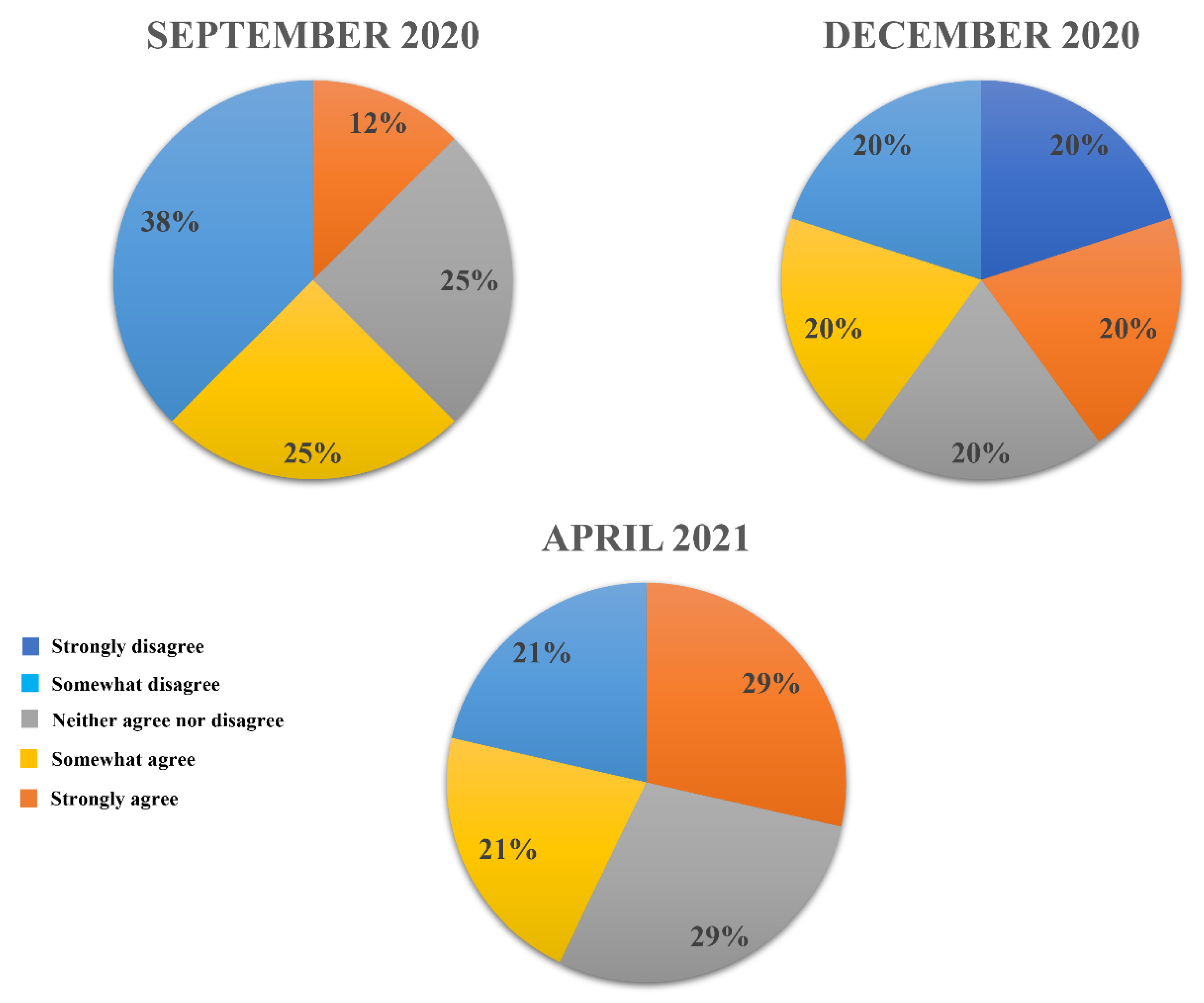

The single question used to measure emotional exhaustion taken from the MBI was, “I feel burned out from my work.” As is shown in

Figure 3, the most selected option by 40% or more of the providers during the three quarterly surveys was “strongly disagree” or “somewhat disagree.” Between 20% to 29% of the participants kept a neutral position, “neither agree nor disagree,” in each of the three surveys, and 12% to 29% of the respondents “somewhat agreed.” In December 2020, 20% “strongly agreed” to feeling burnout from their work, with none strongly agreeing in the following two surveys.

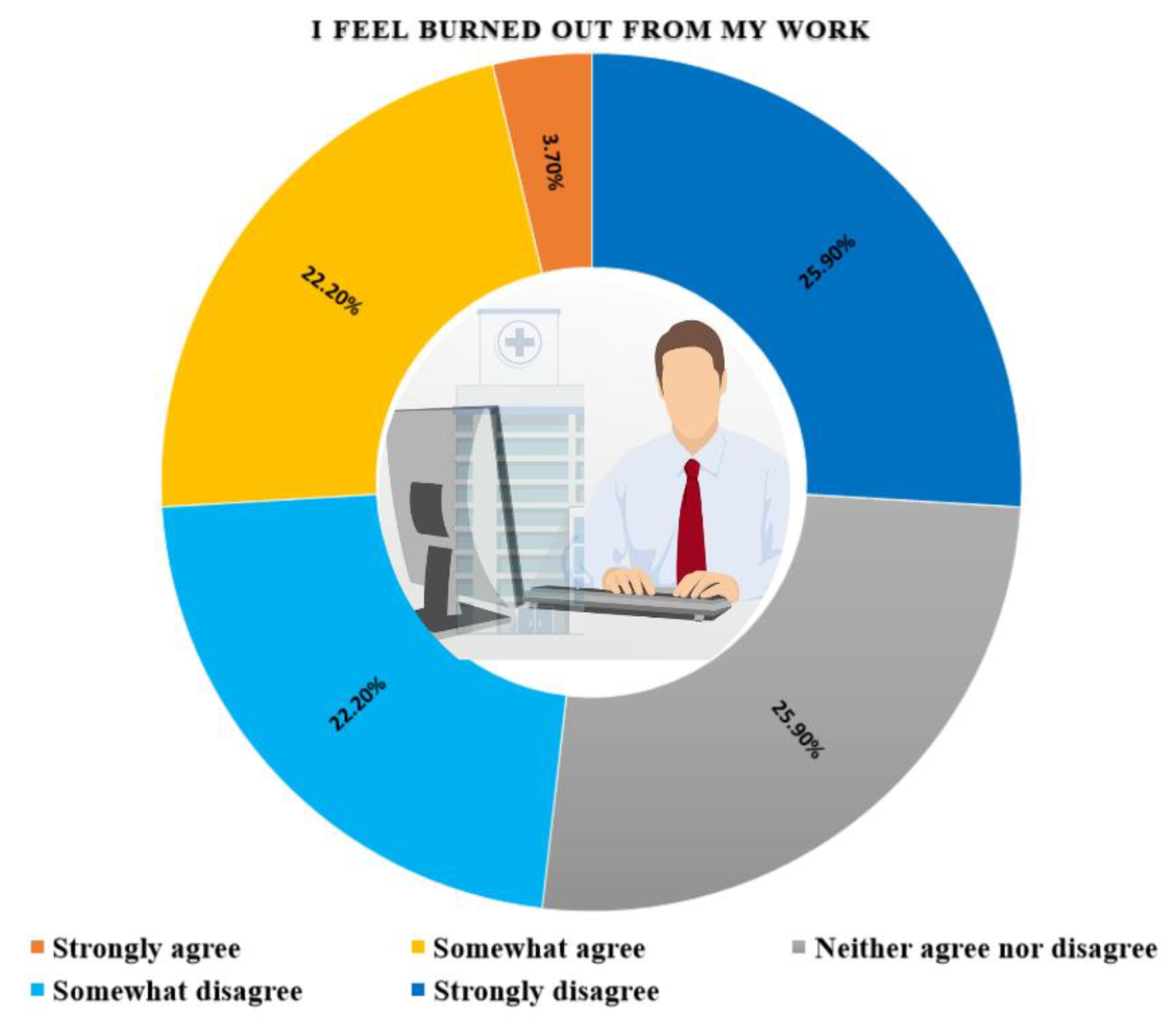

The sum of the answers to the question evaluating emotional exhaustion is presented in

Figure 4. Seven of the providers (26%) maintained a neutral stance. Thirteen of the 27 providers (48%) strongly or somewhat disagree with feeling emotionally exhausted from their work when participating in ACH. On the other hand, less than 4% (1 participant) “strongly agreed” to feeling burned out from work.

4. Discussion

The results obtained from this study confirm that physicians and nurse practitioners delivering care through the ACH program at Mayo Clinic have a low risk of burnout. The three main evaluated dimensions demonstrated low levels of emotional exhaustion and depersonalization and a high grade of personal achievement.

Nearly 80% of the providers agreed or somewhat agreed to feeling a sense of accomplishment in their work and feeling that their job makes good use of skills and abilities. Additionally, 89-96% of the participants agreed or somewhat agreed to feel a strong sense of ownership and responsibility for Mayo Clinic’s success and that using ACH allows them to provide high-quality care, along with the technology, services, and supplies necessary for patient safety. These might be translated as low levels of depersonalization since the providers have empathy and interest in the patient’s care. Furthermore, the emotional exhaustion assessment showed that almost 100% of the respondents agreed or somewhat agreed that they have a positive attitude toward working with ACH and that people at ACH work well together. 77% reported feeling joyful always or most of the time in the past week, and only 26% stated feeling burnout from work. These results indicate a low grade of emotional exhaustion.

Healthcare providers’ burnout plays a fundamental role in the quality of care delivered to patients.[

16] A direct correlation exists between the level of burnout and both a reduced empathy for patients and an increase in the number of medical errors.[

17,

18,

19] Consequently, offering poor quality care leads to decreased patient satisfaction, which negatively influences the provider’s well-being and becomes a vicious circle affecting both the patient’s and the provider’s lives.[

20,

21] This confirms that considerable efforts must be made to identify any signs or symptoms of burnout, implement strategies to avoid its adverse effects and promote the provider’s well-being in the healthcare system.

Several researchers have recognized the Maslach Burnout Inventory as the most validated tool to assess burnout.[

4] The frequency with which people report feelings or emotions over time gives a score, with higher values in questions related to depersonalization and emotional exhaustion and lower values in personal accomplishment signifying burnout.[

5] Since 2009, two items extracted from the original MBI version have been utilized to evaluate burnout in medical professionals, mainly when the entire questionnaire cannot be applied, showing reliable results that counter the limitations associated with the length of this instrument. Incorporating one of these two items into a general medical employee survey might provide accurate information about the risk of burnout in the participants and determine if an in-depth assessment of this topic is needed. The survey applied to the ACH providers sought to evaluate the general experience of the physicians and nurse practitioners working with a relatively new health delivery system offered by the Mayo Clinic. The item extracted from the MBI used to measure burnout included the emotional exhaustion question (“I feel burned out from my work”).

ACH has emerged as a new alternative to delivering patient care using real-time video/audio connections and remote patient monitoring with mobile health tools and devices. Since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, the use of telemedicine in the health system has had an exponential development.[

22,

23] Providers report a vast range of benefits from this new approach, which include improvements in the patient’s ability to access care by avoiding long travels, traffic issues, or needing to find a ride.[

24] Additionally, more frequent follow-up appointments can be made, especially with patients with chronic conditions. Telehealth facilitates assessment of the patient’s home, looking for safety hazards, and also may show a patient’s support system. Finally, medication reconciliation is more manageable to conduct through the use of telehealth systems.[

24,

25]

Conversely to all these positive providers’ perspectives, some barriers associated with the use of telehealth can contribute to an increased risk of healthcare provider burnout. These challenges include the lack of video visit training, low previous technical knowledge, slight technology familiarity, and electronic health record documentation burden that potentially increases the healthcare worker’s demands, affecting the personal achievement domain.[

26,

27]

On the other hand, ACH demonstrated a high level of personal accomplishment, with 89% of the participants strongly or somewhat agreeing that their work gives them a sense of achievement. Similarly, Malouff et al.[

14] reported an improvement in burnout symptoms in approximately one-third of the physicians who answered a survey evaluating physicians’ satisfaction with telemedicine during the COVID-19 pandemic. Additionally, telemedicine has been shown to diminish burnout as it gives more flexibility to the provider’s schedule, giving them more time to enjoy with family and friends and practice hobbies that contribute to creating a work-life balance.[

28]

Several negative consequences can be attributed to the presence of burnout in healthcare providers, starting from a decrease in the quality of patient care to a significant increase in healthcare costs.[

15] Since burnout is a preventable and reversible syndrome, basic knowledge about it is vital. The prompt identification of any signs and symptoms would help to implement strategies to guarantee the well-being of the providers, promoting an effective telehealth service.[

29,

30] Considering the provider’s opinion through a continuous evaluation is the clue to maintaining a well-functioning healthcare system.

Because ACH is listed as a new care delivery model, little to no evidence has been found evaluating the risk of burnout in providers assigned to programs similar to this. In 2019, a pilot randomized control trial that included eight participants was reported by Pian et al.[

31] They evaluated burnout of staff involved in a home hospital pilot program, finding 0% of burnout. A median overall satisfaction with hospital at home was 4.5/5.0, with 50% of the participants preferring the program instead of their standard clinical setting. The lack of a control arm and the sample size in this study make it difficult to generalize its results. Similar limitations are reported in this study. The small sample size and the response rate decrease the power of the study. Thus, categorizing the survey questions to evaluate the main domains associated with burnout represents a high grade of subjectivity based on the authors’ perspectives and interpretation of the results in a descriptive survey-based study, resulting in a source of bias. Finally, different from the original MBI, which uses a 7-points Likert scale, the answer options were described in a 5-options agreement Likert scale, which can interfere with the analysis of the results.

5. Conclusion

Burnout is a preventable and reversible syndrome. After this survey analysis, low levels of provider burnout have been reported in the ACH program at Mayo Clinic. With the accelerated spread of technology in new forms of healthcare delivery, evaluating professional and personal burdens is mandatory to understand providers’ perspectives, feelings, emotions, and preoccupations to maintain healthcare workers’ well-being. Implementing the innovative ACH program has proven to positively impact the provider’s well-being, with more than 70% of physicians and nurse practitioners feeling joyful in their jobs.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.J.M., A.J.F., K.M., C.A.G.C.; Methodology, K.M., C.A.G.C.; Software, K.M., S.P, S.A.H.; Formal analysis, K.M., C.A.G.C., S.P., S.B., A.G.; Validation, All authors; Investigation, K.M., S.B., C.A.G.C., S.A.H., A.G.; Data curation, K.M., C.A.G.C; Writing - original draft, K.M., C.A.G.C.; Writing - review and editing, All authors; Supervision, M.J.M, A.J.F.; Project Administration, M.J.M, A.J.F.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Freudenberger, HJ. The issues of staff burnout in therapeutic communities. J Psychoactive Drugs 1986, 18, 247–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adlakha, D. Burned Out: Workplace Policies and Practices Can Tackle Occupational Burnout. Workplace Health Saf 2019, 67, 531–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maslach C, Leiter MP. Understanding the burnout experience: Recent research and its implications for psychiatry. World Psychiatry 2016, 15, 103–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maslach C, Jackson SE, Leiter MP. In Maslach burnout inventory: Scarecrow Education; 1997.

- West CP, Dyrbye LN, Sloan JA, Shanafelt TD. Single item measures of emotional exhaustion and depersonalization are useful for assessing burnout in medical professionals. J Gen Intern Med 2009, 24, 1318–1321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West CP, Dyrbye LN, Satele DV, Sloan JA, Shanafelt TD. Concurrent validity of single-item measures of emotional exhaustion and depersonalization in burnout assessment. J Gen Intern Med 2012, 27, 1445–1452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howell TG, Mylod DE, Lee TH, Shanafelt T, Prissel P. Physician Burnout, Resilience, and Patient Experience in a Community Practice: Correlations and the Central Role of Activation. J Patient Exp 2020, 7, 1491–1500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reith, TP. Burnout in United States Healthcare Professionals: A Narrative Review. Cureus 2018, 10, e3681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah MK, Gandrakota N, Cimiotti JP, Ghose N, Moore M, Ali MK. Prevalence of and Factors Associated With Nurse Burnout in the US. JAMA Network Open 2021, 4, e2036469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leslie, K. ‘Death by 1000 Cuts’: Medscape National Physician Burnout & Suicide Report 2021. 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Yates, SW. Physician Stress and Burnout. Am J Med 2020, 133, 160–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, J. The Exacerbation of Burnout During COVID-19: A Major Concern for Nurse Safety. J Perianesth Nurs 2020, 35, 439–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raudenská J, Steinerová V, Javůrková A; et al. Occupational burnout syndrome and post-traumatic stress among healthcare professionals during the novel coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. Best Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol 2020, 34, 553–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malouff TD, TerKonda SP, Knight D; et al. Physician Satisfaction with Telemedicine during the COVID-19 Pandemic: The Mayo Clinic Florida Experience. Mayo Clin Proc Innov Qual Outcomes 2021.

- Patel RS, Bachu R, Adikey A, Malik M, Shah M. Factors Related to Physician Burnout and Its Consequences: A Review. Behav Sci (Basel) 2018, 8, 98.

- Tawfik DS, Scheid A, Profit J; et al. Evidence Relating Health Care Provider Burnout and Quality of Care: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med 2019, 171, 555–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas MR, Dyrbye LN, Huntington JL; et al. How do distress and well-being relate to medical student empathy? A multicenter study. J Gen Intern Med 2007, 22, 177–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- West CP, Huschka MM, Novotny PJ; et al. Association of perceived medical errors with resident distress and empathy: A prospective longitudinal study. Jama 2006, 296, 1071–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanafelt TD, Balch CM, Bechamps G; et al. Burnout and medical errors among American surgeons. Ann Surg 2010, 251, 995–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling EJ, Shanafelt TD, Singer SJ. Understanding memorably negative provider care delivery experiences: Why patient experiences matter for providers. Healthc (Amst) 2021, 9, 100544. [Google Scholar]

- Van Gerven E, Vander Elst T, Vandenbroeck S; et al. Increased Risk of Burnout for Physicians and Nurses Involved in a Patient Safety Incident. Med Care 2016, 54, 937–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keesara S, Jonas A, Schulman K. Covid-19 and Health Care’s Digital Revolution. N Engl J Med 2020, 382, e82. [Google Scholar]

- Shachar C, Engel J, Elwyn G. Implications for Telehealth in a Postpandemic Future: Regulatory and Privacy Issues. Jama 2020, 323, 2375–2376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen M, Waller M, Pandya A, Portnoy J. A Review of Patient and Provider Satisfaction with Telemedicine. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep 2020, 20, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez T, Anaya YB, Shih KJ, Tarn DM. A Qualitative Study of Primary Care Physicians’ Experiences With Telemedicine During COVID-19. J Am Board Fam Med 2021, 34, S61–S70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkureishi MA, Choo Z-Y, Lenti G; et al. Clinician Perspectives on Telemedicine: Observational Cross-sectional Study. JMIR human factors 2021, 8, e29690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melnick ER, Harry E, Sinsky CA; et al. Perceived Electronic Health Record Usability as a Predictor of Task Load and Burnout Among US Physicians: Mediation Analysis. J Med Internet Res 2020, 22, e23382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakagawa K, Yellowlees P. Inter-generational effects of technology: Why millennial physicians may be less at risk for burnout than baby boomers. Current psychiatry reports 2020, 22, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Shanafelt T, Trockel M, Ripp J, Murphy ML, Sandborg C, Bohman B. Building a Program on Well-Being: Key Design Considerations to Meet the Unique Needs of Each Organization. Acad Med 2019, 94, 156–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West CP, Dyrbye LN, Rabatin JT; et al. Intervention to promote physician well-being, job satisfaction, and professionalism: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med 2014, 174, 527–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pian J, Cannon B, Schnipper JL, Levine DM. Burnout Among Staff in a Home Hospital Pilot. J Clin Med Res 2019, 11, 484–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).