1. Introduction

Economic inequality has been a subject of extensive study in recent decades, particularly in the wake of the 2008 global financial crisis. The effects of economic inequality on growth and social cohesion have garnered significant interest from economists and policymakers (Balakrishnan, Steinberg, and Syed, 2013). Studies have shown that inequality can lead to slower economic growth while also creating conditions conducive to political and social instability (Dabla-Norris et al., 2015; Keeley, 2015). Specifically, income inequality, combined with austerity policies implemented in many countries, including Greece, has deepened the economic crisis and increased poverty. Greece’s experience during the crisis and the memorandum periods serves as a case study for understanding how inequality impacts economic growth (Ostry, Berg, and Tsangarides, 2014).

The study of income inequalities in Greece is of paramount importance, particularly when analyzed over distinct economic periods. The term “inequality” itself, derived from the Greek word “ανισότητα” (anisotita), underscores the imbalance and disparity in the distribution of wealth and resources within a society. Income inequality, as captured by the Gini coefficient, reflects the concentration of income across various segments of the population. The study of Fasianos and Tsoukalis (2023) reveals significant wealth asymmetries in Greece, with the richest 1% holding as much wealth as the poorest 50%, and wealth inequality worsening between 2009 and 2017.

This research seeks to investigate the evolution of income inequality in Greece during three critical periods: 2003-2008, the pre-crisis era; 2009-2014, the period dominated by economic memoranda; and 2015-2020, the post-memoranda phase. The primary purpose of this study is to explore the correlation between the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) and the Gini coefficient over these periods. By employing linear regression analysis, the research aims to uncover the extent to which economic growth or contraction impacts income distribution. This investigation is significant, as it provides insights into how macroeconomic policies and external shocks, such as financial crises and austerity measures, have influenced economic disparity in Greece. Understanding these dynamics is crucial not only for economists but also for policymakers who seek to design interventions that mitigate inequality.

This study contributes to the existing literature by offering a comprehensive analysis of income inequality trends in Greece over nearly two decades. While previous studies have focused on specific periods or factors influencing inequality, this research provides a longitudinal perspective, bridging the gap between pre-crisis, crisis, and post-crisis Greece. Moreover, by focusing on the Greek economy—a case study that epitomizes the challenges of economic adjustment under external constraints—this research contributes to broader discussions on inequality in economies facing similar structural challenges.

By examining the relationship between GDP and the Gini coefficient across different periods, this study also addresses the ongoing debate regarding the efficacy of economic growth as a mechanism for reducing inequality. While some scholars argue that growth inherently leads to more equitable income distribution, others contend that without targeted policies, growth may exacerbate disparities. This research will shed light on these divergent hypotheses within the context of the Greek economy. Furthermore, the findings of this study are expected to provide valuable insights into the factors driving income inequality in Greece, thereby informing future policy decisions aimed at fostering both economic growth and social equity.

Income inequality is a multifaceted phenomenon that has gained significant attention in both academic and policy circles over the past few decades. Stiglitz (2012) argues that income inequality is not merely a symptom of economic disparity but a driver of economic instability itself. Research has shown that high levels of inequality can impede growth, weaken social cohesion, and lead to political unrest (Piketty, 2014; Atkinson, 2015). The work of Kuznets (2019) laid the foundation for understanding the relationship between economic development and income distribution, famously hypothesizing the “Kuznets Curve,” where inequality initially increases during economic development but decreases after a certain level of income is reached. However, recent panel data analysis of OECD countries from 1990 to 2019 challenges this hypothesis, revealing a U-shaped relationship between economic growth and income inequality. The study of Alves et al. (2022) suggests that countries prioritizing GDP growth over GNI have contributed more to rising inequality, and promoting GNI growth policies could help achieve economic growth while reducing disparities.

The global financial crisis of 2008 exacerbated income disparities worldwide, as noted by Milanovic (2016), who emphasizes that globalization and technological changes have led to an increased concentration of wealth. Inequality has become a global concern, with scholars like Bourguignon (2015) and Coffey et al. (2020) highlighting the growing divide between the rich and the poor. However, the effects of inequality are not uniformly distributed across countries, as factors such as policy responses, social safety nets, and labor market structures play critical roles (OECD, 2011).

Within the European context, studies have shown that the economic crisis and subsequent austerity measures had profound impacts on income distribution. Darvas and Wolff (2016) found that Southern European countries, particularly Greece, Spain, and Portugal, experienced sharp increases in income inequality during the crisis. Meanwhile, Collignon (2012) argues that the Eurozone’s institutional design exacerbated the crisis, leading to uneven recovery and heightened disparities. Income inequality in Europe presents a complex landscape influenced by various factors, including regional disparities, perceptions, and historical contexts. Research indicates that actual income inequality, measured by indices such as the Gini coefficient, shows a relatively even distribution across most EU countries, with Bulgaria as a notable exception exhibiting higher inequality levels (Kolluru and Semenenko, 2021).

However, perceptions of inequality often diverge from reality; individuals in regions with low actual inequality may overestimate inequality, while those in high-inequality areas may underestimate it (Faggian et al., 2023). Furthermore, the concept of income fairness reveals a consensus on perceived inequities, particularly between top and bottom income earners, which intensifies in countries with greater income disparities (Kalleitner and Bohmann, 2023). Historical analyses of Eastern Europe highlight how institutional and political factors have shaped income inequality over time, with significant shifts occurring post-1945 (Nicolic et al., 2024). Overall, these findings underscore the necessity of integrating both objective and subjective measures to fully understand income inequality in Europe.

The article is structured into five main sections as follow.

Section 1: Introduction, outlines the issue of income inequality in Greece, divided into subsections covering the pre-crisis, crisis, and post-crisis periods.

Section 2: Results, presents findings for each period, supported by statistical analysis.

Section 3: Discussion, interprets these results in the context of existing literature.

Section 4: Materials and Methods, explains the econometric models, data sources, and variables used in the analysis. Finally,

Section 5: Conclusion, summarizes the key insights and suggests policy recommendations to address income inequality in Greece.

1.1. Income inequality in Greece

1.1.1. Pre-Crisis Period (2003-2008)

Greece’s economic trajectory during the pre-crisis period was characterized by rapid growth, largely fueled by public spending and external borrowing (Featherstone, 2008). However, as noted by Koutsoukis and Roukanas (2014), this growth was not accompanied by significant improvements in income distribution. On the contrary, the Gini coefficient remained relatively high, reflecting persistent inequality despite the economic boom.

During the pre-crisis period in Greece (2003-2008), income inequality exhibited notable characteristics influenced by various socio-economic factors. Research indicates that while the overall income distribution was relatively stable, underlying disparities were present, particularly across different socio-economic groups. The geographical analysis revealed that income inequality varied significantly by municipality, suggesting that urban areas experienced different economic dynamics compared to rural regions (Psycharis et al., 2023a). Moreover, the relationship between economic growth and income distribution was complex; growth often exacerbated inequality, with benefits not equitably shared among the population (Petrakos et al., 2023). The pre-crisis period also saw a decline in the relative position of the unemployed, while pensioners maintained a more favorable status, indicating a shift in income dynamics that would later be exacerbated by the economic crisis (Andriopoulou et al., 2018). Overall, the pre-crisis landscape set the stage for the significant increases in inequality and poverty that followed the onset of the crisis in 2009 (Giannitsis, and Zografakis, 2018).

1.1.2. Crisis and Memoranda Period (2009-2014)

The Greek debt crisis, triggered by excessive borrowing and structural weaknesses, led to severe austerity measures imposed by the International Monetary Fund (IMF), European Central Bank (ECB), and European Commission—collectively known as the “Troika” (Arghyrou and Tsoukalas, 2011). These measures, as pointed out by Matsaganis and Leventi (2014), had a devastating impact on income distribution, with the Gini coefficient increasing sharply. Social safety nets were eroded, unemployment skyrocketed, and poverty levels reached unprecedented heights. According to Mitrakos (2014), income inequality and relative poverty have risen modestly during the crisis, but the composition of the poor has shifted significantly. The sharp drop in disposable income and the surge in unemployment, however, have led to a substantial decline in economic well-being and a marked increase in absolute poverty, with the poverty line held constant in real terms from the pre-crisis period.

Research by Christopoulou and Monastiriotis (2019) underscores that the austerity measures disproportionately affected low-income households, exacerbating existing inequalities. The period was marked by a deep recession, with GDP contracting by nearly 25%. In this context, studies by Papanastasiou and Papatheodorou (2018) suggest that the Greek crisis was not just a fiscal crisis but also a social crisis, with long-lasting effects on income inequality.

1.1.3. Post-Memoranda Period (2015-2020)

Following the third economic adjustment program, Greece officially exited the bailout programs in 2018. However, as Kaplanoglou (2022) argues, the recovery has been slow and uneven. The Gini coefficient, while showing signs of improvement, remains elevated compared to pre-crisis levels. Inequality during this period has been shaped by several factors, including labor market reforms, tax policies, and changes in social welfare provisions (Matsaganis, 2020). The post-memoranda period led to the implementation of various austerity measures in Greece. These measures aimed to stabilize the economy and reduce the country’s debt burden but also had implications for income inequalities. Research has shown that austerity policies can have adverse effects on income distribution, with the burden often falling disproportionately on the lower-income groups (Mavromaras et al., 2017; Matsaganis et al., 2019).

Income inequalities in Greece during the post-memoranda period (2015-2020) have been characterized by significant disparities exacerbated by economic policies and social conditions. Research indicates that income inequality, as measured by the Gini coefficient, has reached unprecedented levels, surpassing previous assessments by international organizations (Kotsios, 2022). The economic crisis and austerity measures have led to a marked increase in health-related quality of life (HRQoL) inequalities, particularly affecting lower-income groups, with the Theil index showing a 222.3% increase in income-related HRQoL disparities (Yfantopoulos et al., 2023). Furthermore, the geographical analysis reveals that income inequalities are more pronounced in urban areas like Attica compared to rural regions, highlighting a growing socio-economic divide (Psycharis et al., 2023a). The impact of inflation and austerity measures has further intensified these inequalities, with the poorest segments of the population experiencing severe hardships (Missos et al. 2024).

Despite the extensive literature on income inequality in Greece, there is a noticeable gap in longitudinal analyses that compare the evolution of inequality across different economic periods. Most studies focus on specific time frames, such as the crisis years or the post-crisis recovery, but few provide a comprehensive comparison that spans pre-crisis, crisis, and post-crisis periods. This research aims to fill this gap by examining the relationship between GDP and the Gini coefficient across three distinct periods: 2003-2008 (pre-crisis), 2009-2014 (memoranda), and 2015-2020 (post-memoranda).

The research question guiding this study is:

“How has income inequality, as measured by the Gini coefficient, evolved in Greece during the pre-crisis, crisis, and post-crisis periods, and what role has GDP played in this evolution?”

1.1.1.4. Research Hypotheses

Based on the literature and preliminary analysis, the study will test the following hypotheses:

H1: The relationship between GDP and income inequality was positive during the pre-crisis period, indicating that economic growth was accompanied by increasing inequality.

H2: During the crisis period, austerity measures and economic contraction led to a significant increase in income inequality, independent of GDP trends.

H3: In the post-crisis period, while GDP recovery is expected to reduce inequality, structural factors may continue to hinder equitable distribution, leading to a weaker relationship between GDP and inequality.

The article is structured as follows: In

Section 2,

Results, we present the key findings of the econometric analysis, detailing the relationship between GDP and income inequality across the three studied periods: pre-crisis, crisis, and post-crisis.

Section 3,

Discussion, interprets these findings and compares them with existing literature. In

Section 4,

Materials and Methods, we describe the data sources, econometric models, and statistical techniques used in the analysis, providing a clear framework for the study. Finally, in

Section 5,

Conclusions, we summarize the main outcomes of the research, propose policy recommendations based on the findings, and suggest directions for future research while acknowledging the study’s limitations.

2. Results

In this section, we will present the findings from the analysis of the relationship between GDP and income inequality, as measured by the Gini coefficient, across the three distinct periods: 2003-2008 (pre-crisis), 2009-2014 (memoranda), and 2015-2020 (post-memoranda). The results are organized by period, and we include statistical tables and graphs to illustrate the key trends and outcomes to exanimate the research hypotheses.

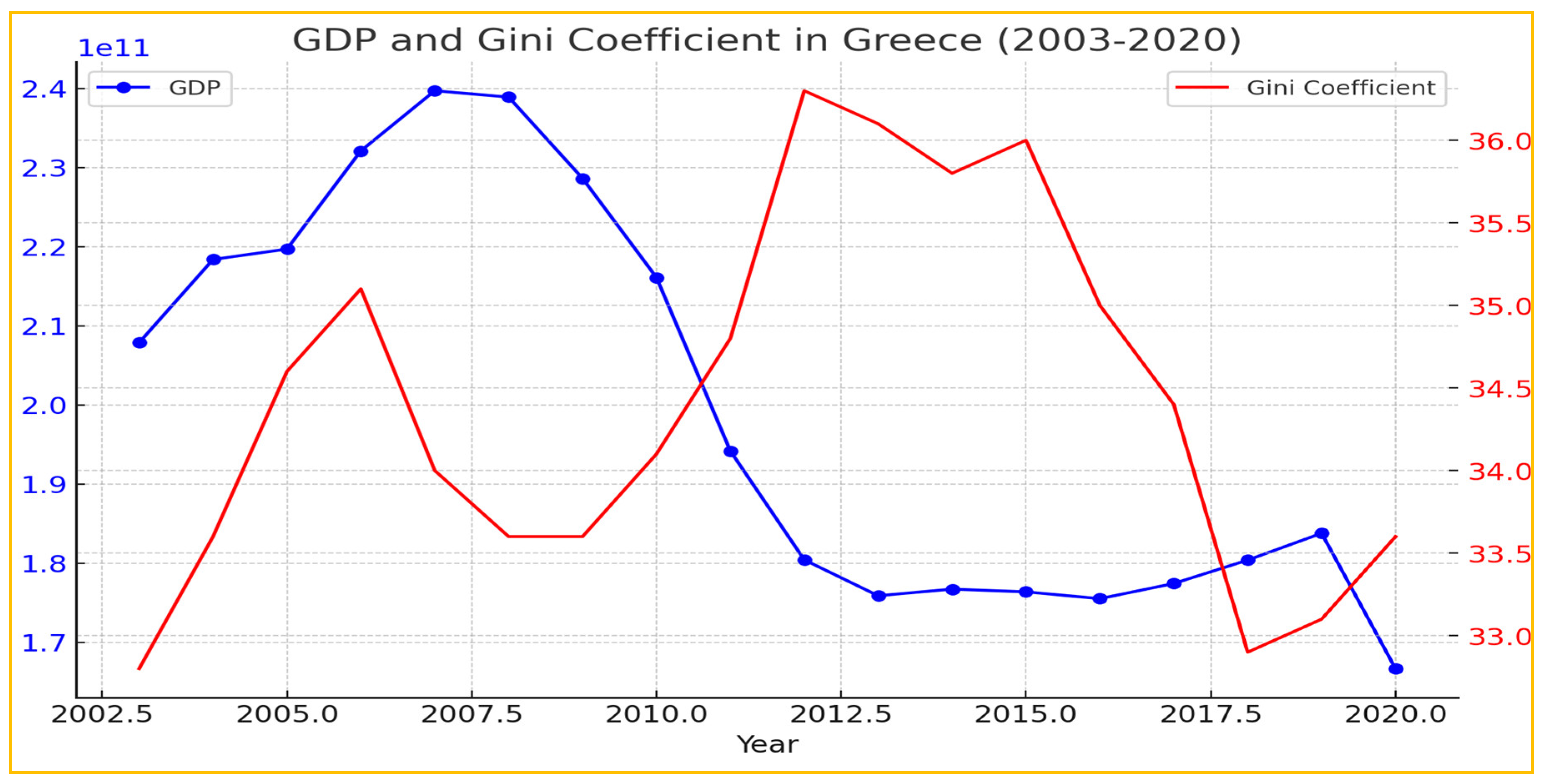

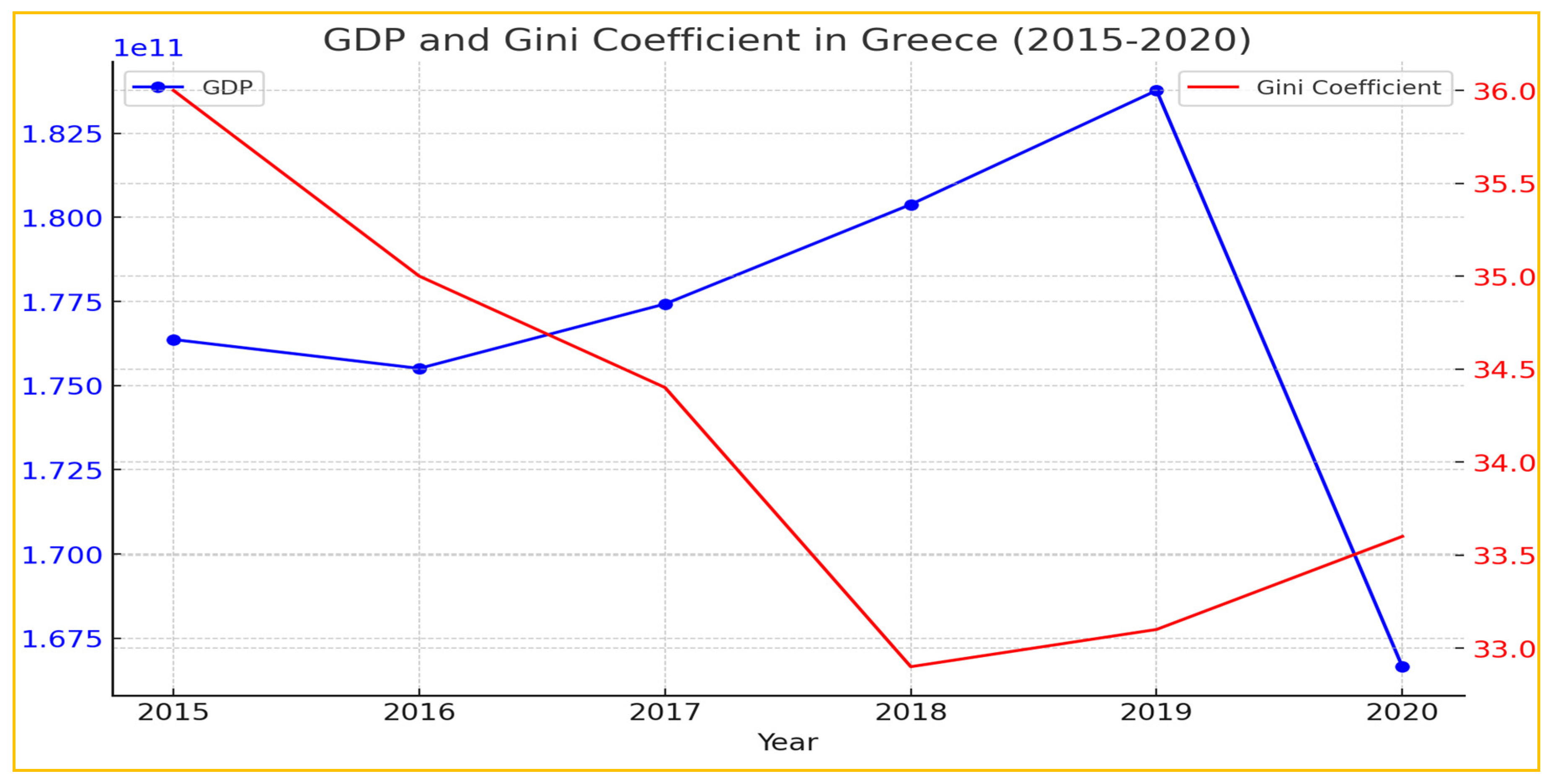

Initially, presented the graph which shows the GDP and Gini coefficient in Greece from 2003 to 2020. The blue line represents the GDP, while the red line represents the Gini coefficient (see

Figure 1).

The graph provides a preliminary overview of the trajectory of the Greek economy from 2003 to 2020, highlighting the relationship between GDP and income inequality as measured by the Gini coefficient. During the pre-crisis years (2003-2008), we observed steady GDP growth, accompanied by a gradual increase in the Gini coefficient, suggesting that economic expansion did not lead to a reduction in inequality. The period of the economic crisis (2009-2014) is marked by a sharp decline in GDP, while the Gini coefficient continues to rise, reflecting the severe social impact of austerity measures. In the post-crisis period (2015-2020), GDP began to recover, but the reduction in inequality is slow, indicating that structural challenges remain.

This graph serves as a foundation for a more detailed analysis that will follow, focusing on each of the three distinct periods (pre-crisis, crisis/memoranda, and post-crisis) to better understand the dynamics between GDP and inequality during these critical phases of Greece’s economic history.

2.1. Pre-Crisis Period (2003-2008)

During the pre-crisis period, Greece experienced economic growth driven by increased public spending and external borrowing. However, our analysis shows a positive correlation between GDP and the Gini coefficient during this period, indicating that economic growth was accompanied by rising income inequality.

R (Correlation Coefficient = 0.434): This indicates a moderate positive correlation between GDP and the Gini coefficient. A positive R value suggests that as GDP increased, the Gini coefficient also tended to increase, indicating rising income inequality during this period. However, the strength of this correlation is moderate.

R Square (0.189): This value indicates that approximately 18.9% of the variation in the Gini coefficient can be explained by changes in GDP during this period. While there is some explanatory power, the majority of the variation in income inequality is due to other factors not captured by GDP alone.

Adjusted R Square (-0.014): The adjusted R square is slightly negative, suggesting that when adjusting for the number of predictors, the model does not fit the data well. This indicates that GDP alone may not be a strong predictor of changes in the Gini coefficient during this period, while additional variables may be needed to explain the variation in income inequality.

Standard Error of the Estimate (0.8201): This value represents the average distance that the observed values fall from the regression line. The higher this value, the less accurate the model’s predictions.

Durbin-Watson (1.142): This statistic tests for the presence of autocorrelation in the residuals. A value close to 2 indicates no autocorrelation, while a value closer to 0 or 4 suggests positive or negative autocorrelation, respectively. A Durbin-Watson value of 1.142 suggests some positive autocorrelation in the residuals, meaning that the residuals are not completely independent.

The analysis for this period indicates a moderate positive relationship between GDP and income inequality, as measured by the Gini coefficient. However, the relatively low R-squared and adjusted R-squared values suggest that GDP alone does not fully explain the changes in income inequality during these years. The model’s fit is limited, and other factors likely contributed to the variation in inequality during this period of economic growth in Greece.

Regression Sum of Squares (0.625): This value represents the variation explained by the regression model (i.e., the effect of GDP on the Gini coefficient). It shows how much of the total variability in the Gini coefficient can be attributed to changes in GDP during the 2003-2008 period.

Residual Sum of Squares (2.690): This value represents the variation that is not explained by the model. It indicates the amount of variability in the Gini coefficient that remains unexplained after accounting for the GDP variable.

Mean Square (Regression = 0.625, Residual = 0.672): The mean squares are calculated by dividing the sum of squares by their respective degrees of freedom. The mean square for the regression reflects the average amount of variation explained by the model, while the mean square for the residual reflects the average amount of unexplained variation.

F-statistic (0.929): The F-statistic tests the overall significance of the regression model. A higher F-value indicates that the model is a better fit for the data. In this case, the F-value of 0.929 suggests that the model does not significantly explain the variance in the Gini coefficient.

Significance (p-value = 0.390): This p-value indicates the probability that the observed relationship between GDP and the Gini coefficient is due to chance. A p-value greater than 0.05 suggests that the relationship is not statistically significant. In this case, the p-value of 0.390 indicates that the model does not significantly predict the Gini coefficient based on GDP for this period.

The ANOVA table for the 2003-2008 period suggests that the regression model does not significantly explain the variation in the Gini coefficient. Although there is a positive correlation between GDP and inequality, as indicated by the earlier model summary, this relationship is not statistically significant, meaning that GDP alone may not be a strong predictor of income inequality during this period.

Unstandardized Coefficients (B):

Constant (27.702): This is the intercept of the regression equation. It represents the predicted value of the Gini coefficient when GDP is zero. However, since GDP cannot realistically be zero in this context, this value mainly serves as a starting point for the regression equation.

GDP (2.763E-11): This coefficient represents the change in the Gini coefficient for each one-unit change in GDP. Although this value is very small (essentially zero when considering GDP in larger scales), it still indicates a positive relationship between GDP and the Gini coefficient.

Standardized Coefficients (Beta = 0.434): The standardized coefficient allows us to compare the relative importance of GDP in predicting the Gini coefficient. A Beta of 0.434 indicates a moderate positive relationship between GDP and the Gini coefficient. This matches the earlier findings that suggest as GDP increases, so does income inequality.

t-statistic (0.964): The t-value tests whether the coefficient is significantly different from zero. A t-value of 0.964 indicates that the coefficient for GDP is not significantly different from zero, meaning GDP may not be a strong predictor of the Gini coefficient during this period.

Significance (p-value = 0.390): The p-value indicates the probability that the observed relationship occurred by chance. A p-value greater than 0.05 suggests that the relationship is not statistically significant. In this case, the p-value of 0.390 confirms that the relationship between GDP and the Gini coefficient is not statistically significant for this period.

Correlations:

Zero-order (0.434): This represents the simple correlation between GDP and the Gini coefficient, without controlling for any other variables.

Partial and Part correlations (0.434): These are the same in this case because there is only one predictor variable (GDP). These values indicate the strength of the relationship between GDP and the Gini coefficient, controlling for other factors (if any were present).

Collinearity Statistics (Tolerance = 1.000, VIF = 1.000): These values indicate whether multicollinearity is a concern in the model. A tolerance value close to 1 and a VIF value of 1 indicate that there is no multicollinearity in this model, which is expected since there is only one predictor variable.

The coefficients table reinforces the earlier findings: while there is a moderate positive relationship between GDP and the Gini coefficient during the 2003-2008 period, this relationship is not statistically significant. The positive Beta value suggests that as GDP increased, income inequality also increased, but the lack of statistical significance means we cannot confidently state that GDP is a strong predictor of inequality during this time.

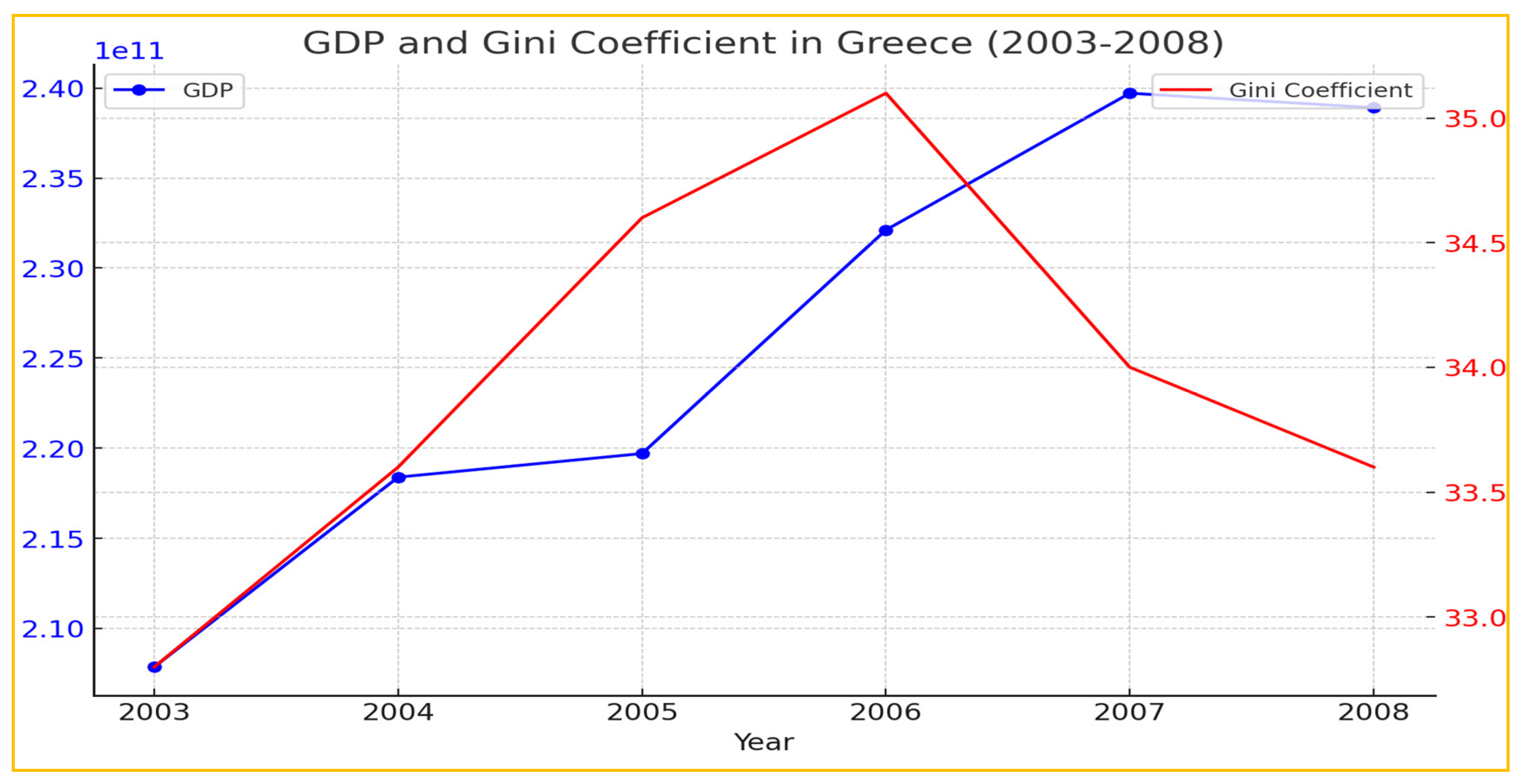

The following graph (see

Figure 2) is showing the GDP and Gini coefficient in Greece for the period 2003-2008. The blue line represents GDP, while the red line represents the Gini coefficient.

GDP Growth: There is a steady increase in GDP during this period, reflecting the economic expansion that Greece experienced before the financial crisis.

Gini Coefficient: The Gini coefficient also shows an upward trend initially, indicating rising income inequality. However, it begins to decline slightly towards the end of the period (2007-2008), suggesting some leveling off in inequality as the economic conditions changed.

This graph provides a visual representation of the moderate positive relationship between GDP and income inequality that was observed in the statistical analysis. The detailed analysis for this period, as discussed earlier, indicates that while GDP growth contributed to rising inequality, the relationship was not statistically significant.

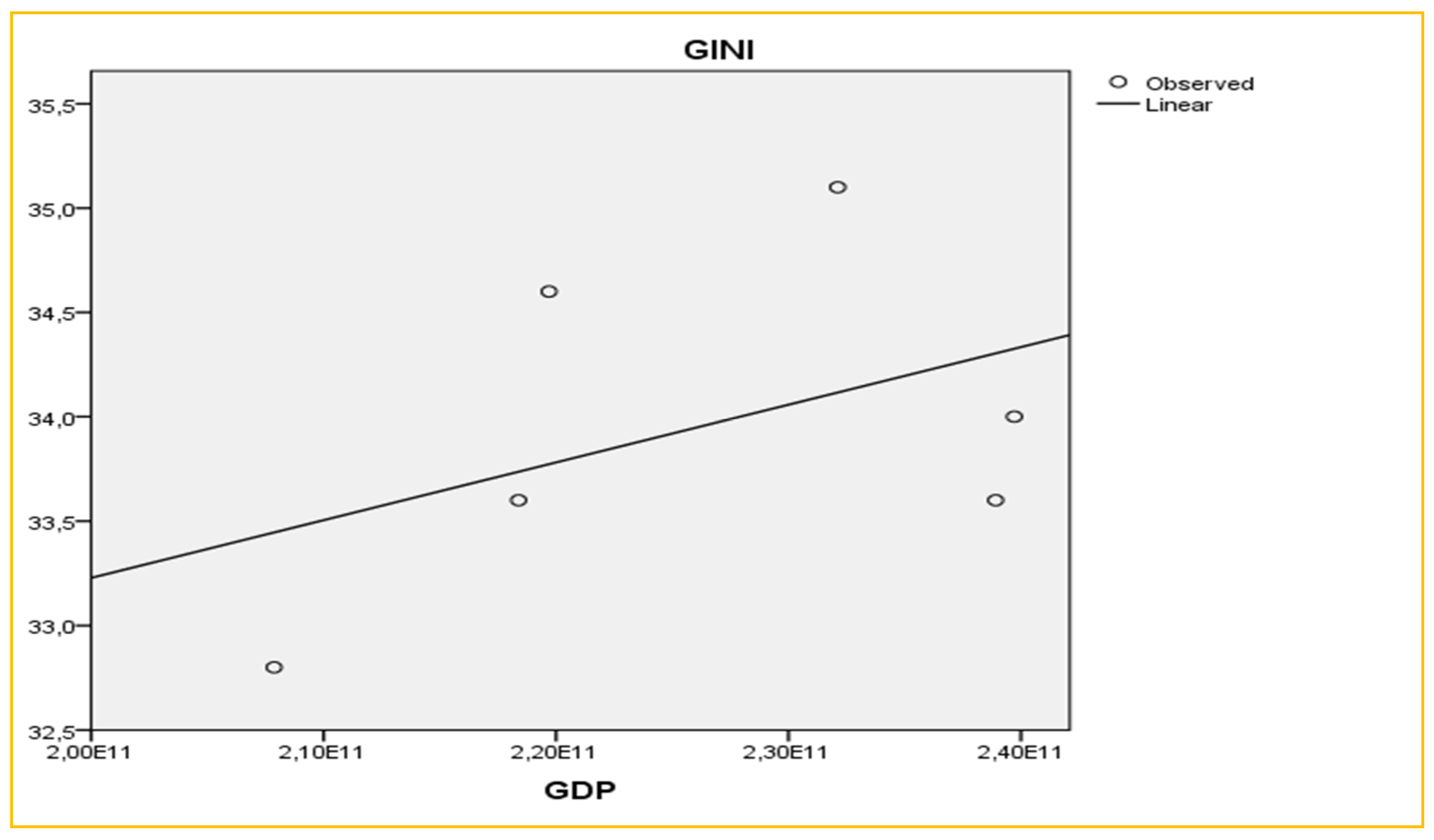

Next, is the graph (see

Figure 3) with the fitted curve for the relationship between GDP and the Gini coefficient in Greece during the period 2003-2008.

The fitted line shows a positive trend, consistent with the earlier analysis, indicating that as GDP increased, the Gini coefficient also tended to rise, reflecting increased income inequality. The actual data points are spread around the fitted line, illustrating that while there is a trend, there is also variability that the model does not fully capture, which is consistent with the moderate R-squared value observed in the earlier analysis.

2.2. Crisis and Memoranda Period (2009-2014)

The economic crisis, which began in 2009, led to severe austerity measures under the guidance of the Troika. This period was characterized by a sharp contraction in GDP and a significant increase in income inequality.

R (0.967): This indicates a very strong negative correlation between GDP and the Gini coefficient during the 2009-2014 period. As GDP decreased, the Gini coefficient increased, reflecting worsening income inequality as the economy contracted.

R Square (0.935): This value indicates that 93.5% of the variation in the Gini coefficient can be explained by changes in GDP during this period. This is a very high explanatory power, suggesting that GDP is a strong predictor of income inequality during this period.

Adjusted R Square (0.918): This value, slightly lower than R Square, still confirms the model’s strong explanatory power, even after adjusting for the number of predictors.

Standard Error of the Estimate (0.3202): This represents the average distance that the observed values fall from the regression line. The smaller this value, the better the model fits the data.

Durbin-Watson (2.636): This value is slightly above 2, suggesting that there may be some negative autocorrelation in the residuals.

Regression Sum of Squares (5.858): This value represents the variation in the Gini coefficient that is explained by GDP.

Residual Sum of Squares (0.410): This value represents the variation that is not explained by the model.

F-statistic (57.149): The high F-value suggests that the model significantly explains the variation in the Gini coefficient.

Significance (p-value = 0.002): The very low p-value indicates that the relationship between GDP and the Gini coefficient is statistically significant.

As far as the coefficients of

Table 6 is concerned:

Constant (44.591): This is the intercept of the regression line, representing the predicted Gini coefficient when GDP is zero.

GDP Coefficient (-4.851E-11): This negative coefficient suggests that as GDP decreases, the Gini coefficient increases. The magnitude of the coefficient reflects the rate of change in the Gini coefficient relative to changes in GDP.

t-statistic (-7.560): The t-value indicates that the GDP coefficient is significantly different from zero.

Significance (p-value = 0.002): The low p-value confirms that GDP is a significant predictor of the Gini coefficient during this period.

Collinearity Statistics:

Tolerance (1.000) and VIF (1.000): These values indicate that there is no multicollinearity in the model, which is expected since there is only one predictor variable.

The regression analysis for the 2009-2014 period indicates a very strong and statistically significant negative relationship between GDP and the Gini coefficient. As the Greek economy contracted due to the financial crisis and austerity measures, income inequality worsened significantly. The model explains a substantial portion of the variation in income inequality during this period, highlighting the profound impact of the economic downturn on the distribution of income.

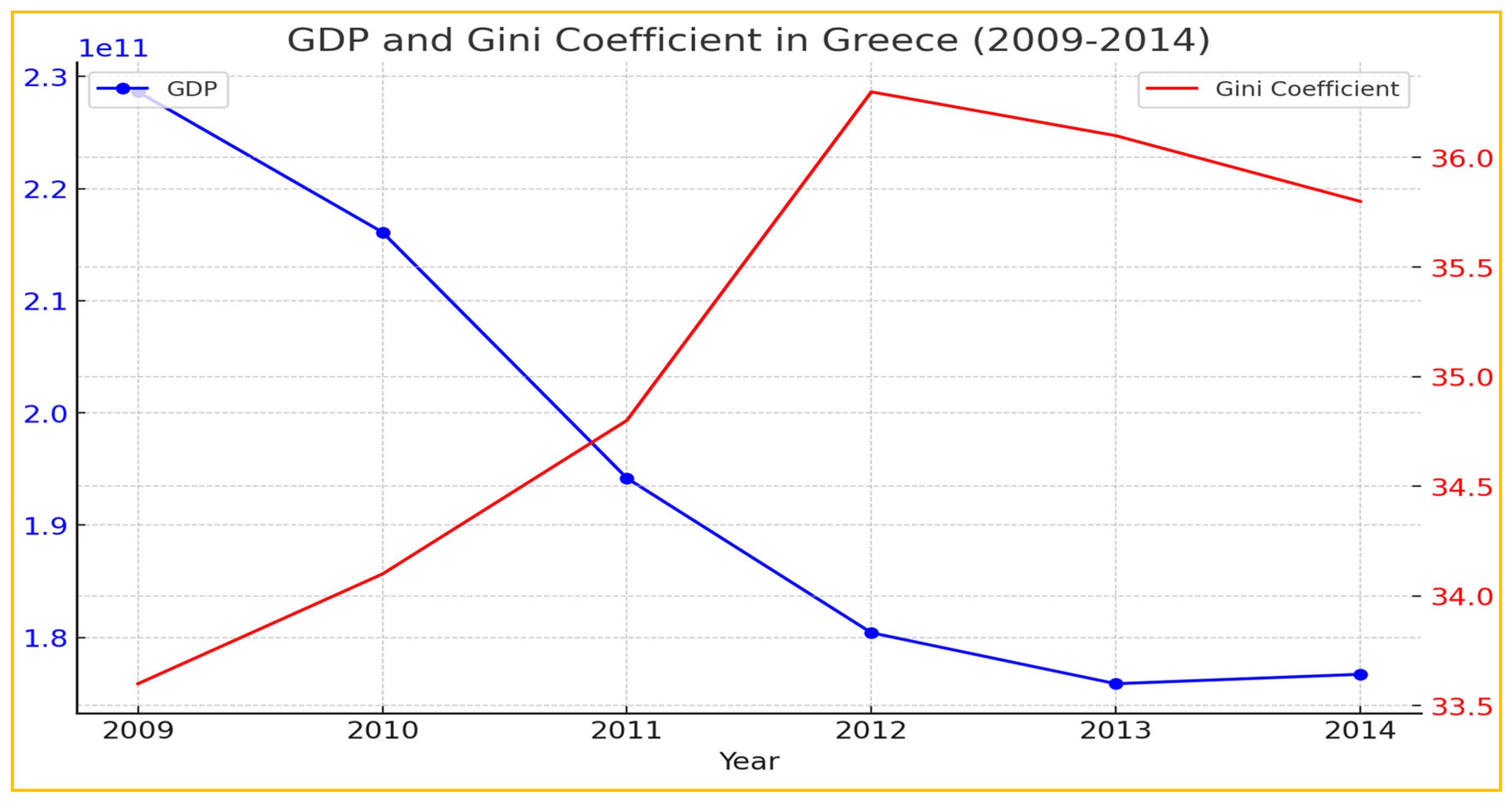

Figure 4 is the graph showing the GDP and Gini coefficient in Greece for the period 2009-2014. The blue line represents GDP, while the red line represents the Gini coefficient.

GDP Contraction: During this period, GDP significantly declined, reflecting the severe economic crisis that Greece faced. This sharp decline illustrates the impact of austerity measures and the broader economic recession.

Gini Coefficient Increase: In contrast to GDP, the Gini coefficient increased during the same period, peaking around 2012-2013. This suggests that as the economy contracted, income inequality worsened, with a larger share of income concentrated among fewer individuals.

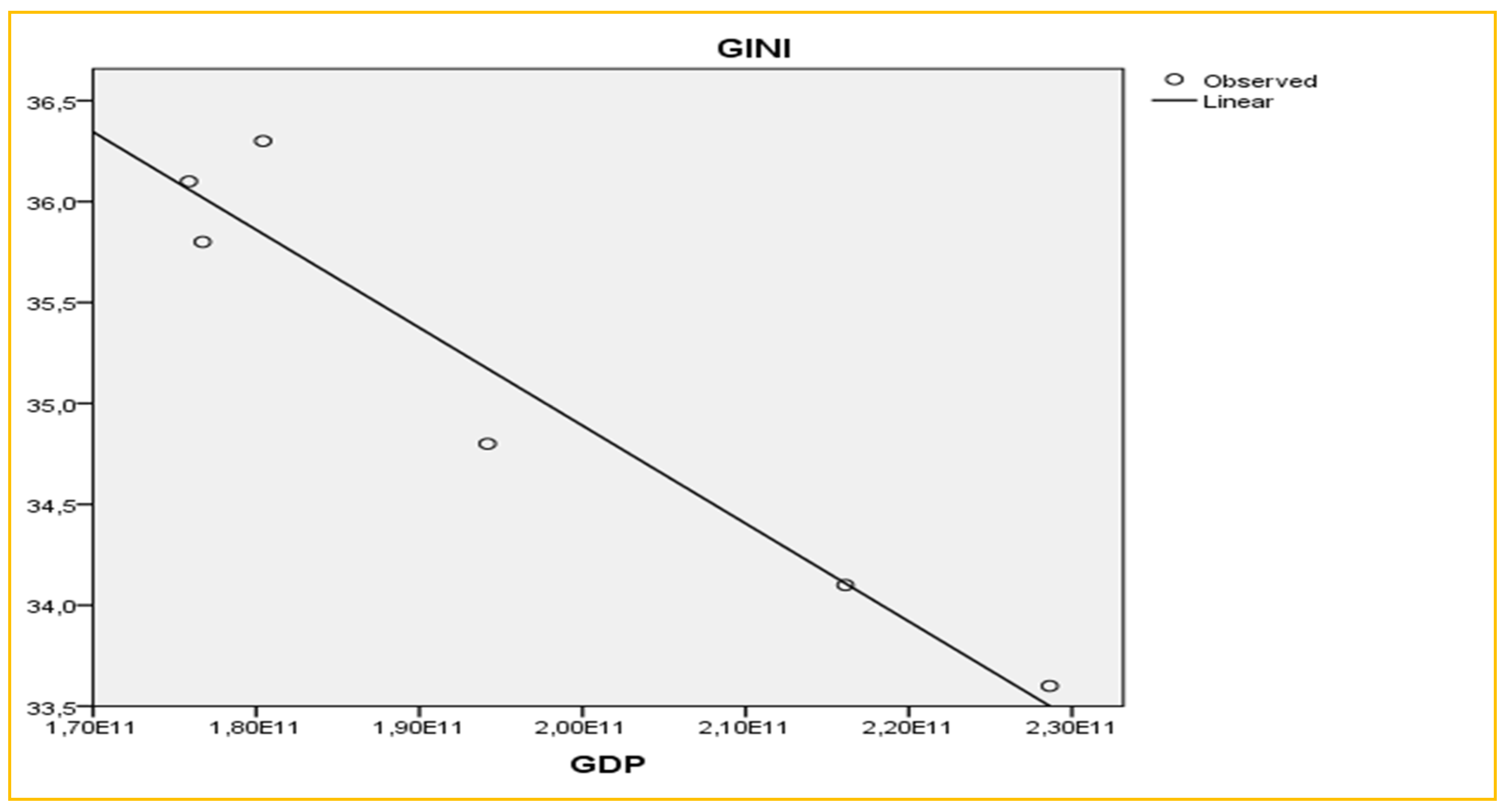

The trends observed in this graph (see

Figure 4) align with the earlier discussions about the negative relationship between GDP and income inequality during this period. The economic downturn disproportionately affected lower-income groups, leading to a rise in inequality. Next is the fitted curve for the relationship between GDP and the Gini coefficient in Greece during the period 2009-2014 (see

Figure 5).

The fitted line shows a clear negative trend, which is consistent with the earlier analysis that suggested a negative relationship between GDP and income inequality during this period. As GDP decreased, the Gini coefficient increased, indicating that the economic contraction led to worsening income inequality. The data points are well-aligned with the fitted line, illustrating that the model captures the trend quite effectively for this period.

2.3. Post-Memoranda Period (2015-2020)

Following the end of the economic adjustment programs, Greece entered a period of slow economic recovery. However, the effects of the crisis lingered, and inequality remained a persistent issue.

R (0.230): This indicates a weak negative correlation between GDP and the Gini coefficient during the 2015-2020 period. The relationship between GDP and income inequality appears to be weak for this period.

R Square (0.053): This value indicates that only 5.3% of the variation in the Gini coefficient can be explained by changes in GDP during this period. This suggests that GDP is not a strong predictor of income inequality in this time frame.

Adjusted R Square (-0.184): The negative adjusted R square value indicates that the model does not fit the data well. After adjusting for the number of predictors, the model’s explanatory power is even lower.

Standard Error of the Estimate (1.3032): This represents the average distance that the observed values fall from the regression line. The higher this value, the less accurate the model’s predictions.

Durbin-Watson (0.503): This value indicates a high level of positive autocorrelation in the residuals. A value closer to 2 would suggest no autocorrelation, so this value suggests that the residuals are not independent.

Regression Sum of Squares (0.380): This value represents the variation in the Gini coefficient that is explained by GDP.

Residual Sum of Squares (6.793): This value represents the variation that is not explained by the model.

F-statistic (0.224): The low F-value suggests that the model does not significantly explain the variation in the Gini coefficient.

Significance (p-value = 0.661): The high p-value indicates that the relationship between GDP and the Gini coefficient is not statistically significant for this period.

Constant (42.604): This is the intercept of the regression line, representing the predicted Gini coefficient when GDP is zero.

GDP Coefficient (-4.775E-11): This negative coefficient suggests that as GDP decreases, the Gini coefficient increases, but the relationship is very weak and not statistically significant.

t-statistic (-0.473): The low t-value indicates that the GDP coefficient is not significantly different from zero.

Significance (p-value = 0.661): The high p-value confirms that GDP is not a significant predictor of the Gini coefficient during this period.

Collinearity Statistics:

Tolerance (1.000) and VIF (1.000): These values indicate that there is no multicollinearity in the model, which is expected since there is only one predictor variable.

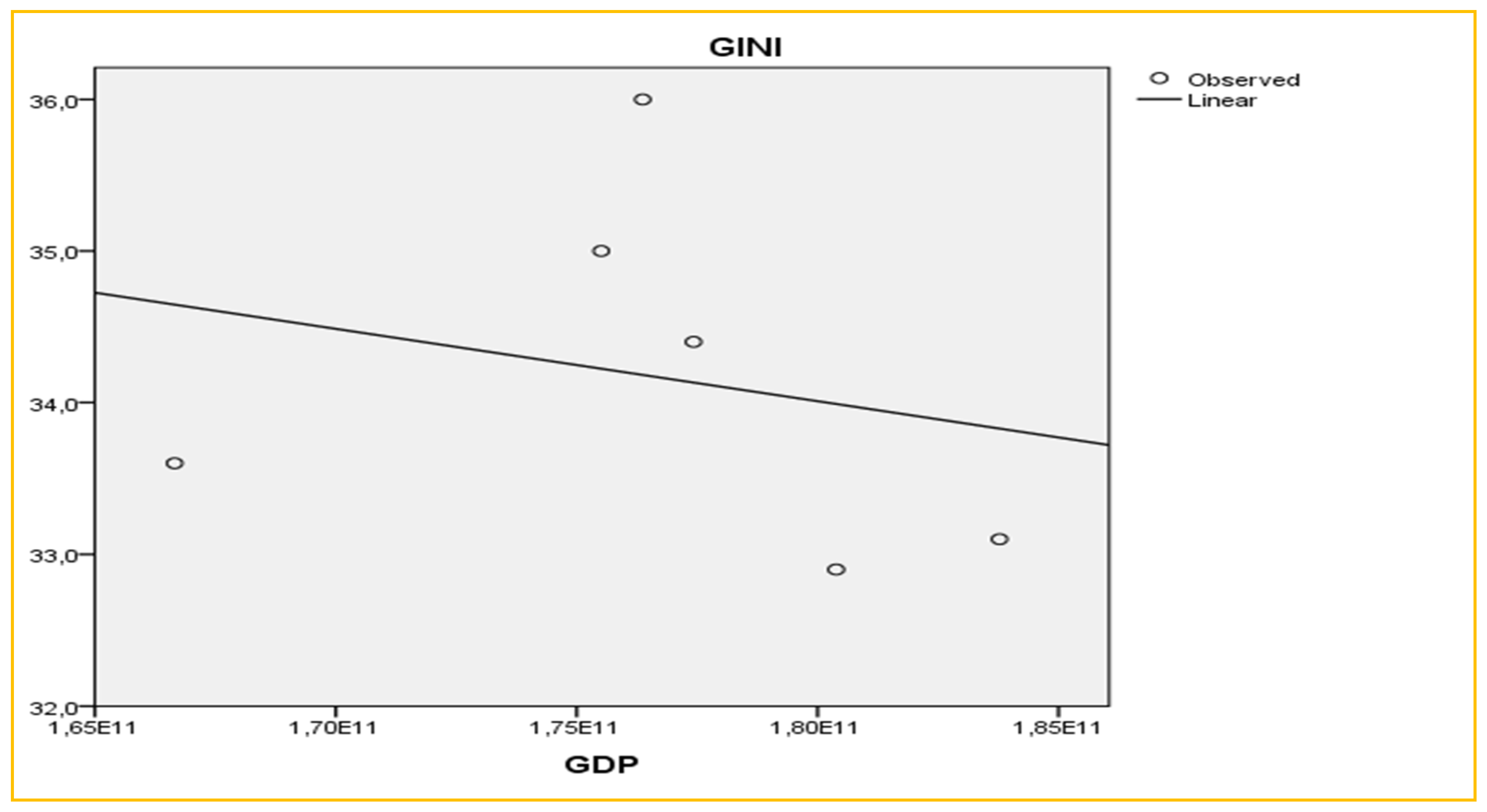

The regression analysis for the 2015-2020 period indicates a weak and statistically insignificant relationship between GDP and the Gini coefficient. The model explains only a small fraction of the variation in income inequality, suggesting that other factors may have played a more significant role in determining inequality during this period. This aligns with the earlier observations that, while GDP showed some recovery, its impact on reducing inequality was limited. Then, in

Figure 6, the graph is presented showing the GDP and Gini coefficient in Greece for the period 2015-2020. The blue line represents GDP, while the red line represents the Gini coefficient.

GDP Recovery: During this period, GDP shows a mixed trend, with a slight recovery in 2019, followed by a sharp decline in 2020, likely due to the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Gini Coefficient: The Gini coefficient generally decreases from 2015 to 2018, indicating a reduction in income inequality. However, it begins to rise again slightly in 2019 and stabilizes in 2020.

This graph highlights the challenges faced by the Greek economy in the post-memoranda period. While there were signs of economic recovery, the COVID-19 pandemic had a significant impact on GDP, and income inequality remains a persistent issue, though it did improve slightly in the earlier part of this period. Finally, in

Figure 7, the fitted curve for the relationship between GDP and the Gini coefficient in Greece during the period 2015-2020 is presented.

The fitted line shows a slight negative trend, suggesting that as GDP increased during this period, the Gini coefficient tended to decrease. This indicates a potential reduction in income inequality as the economy starts to recover, although the relationship appears weaker compared to previous periods.

The spread of the actual data points around the fitted line indicates some variability in the relationship between GDP and the Gini coefficient during this period. This analysis aligns with the earlier observations that, while there was some economic recovery during this period, the reduction in income inequality was not as strong or consistent as might have been expected.

2.4. Examination of research hypotheses

The statistical findings provide mixed support for the hypotheses. While the positive relationship between GDP and inequality in the pre-crisis period is observed, it is not statistically significant. The crisis period shows strong evidence supporting the hypothesis that economic contraction led to increased inequality, driven by austerity measures. In the post-crisis period, the expected weak relationship between GDP and inequality is confirmed, with structural factors likely playing a significant role in maintaining persistent inequality.

-

Findings:

- (i)

R (0.434): A moderate positive correlation between GDP and the Gini coefficient was found during this period.

- (ii)

R-Square (0.189): Approximately 18.9% of the variation in income inequality can be explained by changes in GDP.

- (iii)

Standardized coefficient Beta (0.434): A moderate positive correlation between GDP and the Gini.

- (iv)

P-value (0.390): The relationship is not statistically significant.

Conclusion: While there is a positive relationship between GDP and income inequality during this period, the lack of statistical significance suggests that GDP alone may not be a strong predictor of rising inequality. This hypothesis is partially supported, but the evidence is not strong enough to confirm it definitively.

Hypothesis 3: In the post-crisis period (2015-2020), while GDP recovery is expected to reduce inequality, structural factors may continue to hinder equitable distribution, leading to a weaker relationship between GDP and inequality.

-

Findings:

- (i)

R (-0.230): A weak negative correlation between GDP and the Gini coefficient was observed, suggesting that GDP recovery had a limited impact on reducing inequality.

- (ii)

R-Square (0.053): Only 5.3% of the variation in income inequality can be explained by changes in GDP.

- (iii)

Standardized coefficient Beta (-0.230): A weak negative correlation between GDP and the Gini coefficient.

- (iv)

P-value (0.661): The relationship is not statistically significant.

Conclusion: This hypothesis is supported. The weak and statistically insignificant relationship between GDP and inequality during this period suggests that while there was some economic recovery, structural issues continued to hinder significant reductions in inequality. This aligns with the idea that GDP growth alone was not enough to address the underlying factors contributing to income inequality.

These results highlight the complexity of the relationship between economic growth and income inequality in Greece across different economic periods. While GDP is a significant factor during periods of economic contraction, its role in reducing inequality during recovery periods appears limited, suggesting the need for targeted policies to address structural issues.

3. Discussion

The analysis of the pre-crisis period (2003-2008) reveals that economic growth in Greece was accompanied by a moderate increase in income inequality. The positive correlation between GDP and the Gini coefficient, although not statistically significant, suggests that the benefits of economic expansion were not equitably distributed. This finding aligns with critiques of “trickle-down” economics, which posit that economic growth does not necessarily lead to reductions in inequality without deliberate policy interventions. The lack of statistical significance in this period indicates that other factors, beyond GDP, may have played a more significant role in determining income distribution.

Comparing this period with other studies, the findings resonate with Piketty’s (2014) argument that capital accumulation tends to increase inequality unless countered by progressive taxation. Similarly, Stiglitz (2012) emphasizes that economic growth often fails to benefit the lower-income segments of society without appropriate policies in place. Milanovic (2016) also supports this view, highlighting that globalization and technological changes during growth periods can exacerbate income disparities. Featherstone (2008) further corroborates this, noting that Greece’s growth during this period was unsustainable and unevenly distributed, setting the stage for the subsequent crisis.

The crisis period (2009-2014) is marked by a significant contraction in GDP and a corresponding increase in income inequality. The strong and statistically significant negative correlation between GDP and the Gini coefficient during this period indicates that the economic downturn, compounded by austerity measures, disproportionately affected lower-income households, leading to a sharp rise in inequality. This finding highlights the adverse effects of austerity policies, which exacerbated income disparities at a time when social protection was most needed. The results underscore the vulnerability of marginalized groups during economic crises and the importance of maintaining robust social safety nets.

This conclusion is consistent with research by Matsaganis and Leventi (2014), who found that poverty and inequality in Greece increased significantly during the recession, primarily due to the erosion of social safety nets. The findings also resonate with Stiglitz’s (2012) argument that austerity measures, rather than stabilizing economies, often deepen economic downturns and exacerbate inequality.

In the post-crisis period (2015-2020), the analysis reveals a weak and statistically insignificant relationship between GDP and income inequality. While the Greek economy showed signs of recovery, the benefits of this growth did not translate into substantial reductions in inequality. This finding suggests that structural factors, such as labor market segmentation and persistent unemployment, continued to hinder equitable growth. The limited impact of GDP on reducing inequality during this period highlights the need for comprehensive structural reforms to address the underlying causes of income disparity.

The conclusions drawn from this period align with Atkinson’s (2015) argument that economic recovery alone is insufficient to reduce inequality without targeted policies that address structural issues. Milanovic (2016) also points out that inequality tends to persist even during periods of economic recovery unless deliberate efforts are made to redistribute income more equitably.

Our study, focusing on the periods before, during, and after the crisis, aligns with the findings of Andriopoulou et al. (2018), which examine the impact of the crisis on inequality and poverty in Greece from 2007 to 2014. Both studies observe a significant increase in inequality, particularly driven by rising unemployment. However, while our research highlights the correlation between GDP and inequality, Andriopoulou et al. (2018) provide a deeper analysis of the differential impact on various socio-economic groups, noting that pensioners improved their relative position, whereas households headed by unemployed individuals faced severe deterioration, contributing markedly to the rise in poverty. This comparison underscores the complex and varied effects of the crisis across different population segments.

In our study, we identify a significant increase in income inequality in Greece during the economic crisis, driven by economic contraction and austerity measures at the national level. This finding aligns with the results of Psycharis et al. (2023a), who also observe a rise in inequality the period 2002-2014, but focus on the geographical variation across different regions. While we emphasize the uniform national trends in inequality, Psycharis et al. (2023b), highlight that metropolitan areas experienced a sharp increase in inequality, whereas non-metropolitan regions saw a decrease, primarily due to tax policies and the broader distribution of lower incomes. This distinction underscores that the impact of the crisis on inequality was not homogeneous across all regions. Nonetheless, both studies concur on the overall detrimental effect of the crisis on income distribution, particularly in urban areas.

The findings of our study align with those of Petrakos et al. (2023), which demonstrate that the economic crises of the 2010s significantly exacerbated income inequality and poverty in Greece. Both studies confirm that income inequality worsened during the crisis period, with the economically disadvantaged being disproportionately affected. While our analysis emphasizes the correlation between GDP and inequality across different periods, highlighting that economic growth alone did not suffice to reduce inequality, Petrakos et al. extend this by incorporating additional measures such as the quintile share ratio (S80/S20) and the at-risk-of-poverty rate, further illustrating the broader negative social impacts of the crises. Both studies call for more effective policy interventions, particularly in the areas of labor market reforms and social protection, to mitigate the persistent inequalities that have emerged. This convergence in findings underscores the need for targeted and sustained policy efforts to address the structural challenges in the Greek economy.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Data Collection and Sources

Data Sources: The primary data used in this study were obtained from the World Bank Open Data database (World Bank, 2024). The data include annual figures for GDP (in constant US dollars) and the Gini coefficient for Greece. The data were processed with the IBM SPSS STATISTICS 23 statistical program.

Variables:

Dependent Variable: Income inequality, measured by the Gini coefficient, which represents the distribution of income across the population. A higher Gini coefficient indicates greater income inequality.

Independent Variable: GDP, measured in constant US dollars, which represents the overall economic output of Greece.

-

Time Period: The study spans three distinct periods:

- (i)

2003-2008: Pre-crisis period characterized by economic growth.

- (ii)

2009-2014: Crisis and memoranda period marked by economic contraction and austerity measures.

- (iii)

2015-2020: Post-crisis period involving economic recovery and structural reforms.

4.2. Data Analysis and Model Specification

Correlation Analysis: To explore the relationship between GDP and the Gini coefficient, Pearson correlation coefficients were calculated for each period. This step provided insight into the direction and strength of the relationship between economic growth and income inequality.

Linear Regression Analysis: A linear regression model was used to quantify the relationship between GDP (independent variable) and the Gini coefficient (dependent variable) across the three periods. The model was specified as follows:

where Gini

t is the Gini coefficient at time t, GDP

t is GDP at time t, α (alpha) is the intercept, β (beta) is the coefficient representing the impact of GDP on the Gini coefficient, and ε

t (epsilon) is the error term.

Hypothesis Testing: The regression analysis was used to test the study’s hypotheses by examining the statistical significance of the β (beta) coefficient for each period. The significance of the relationship was determined using p-values, with a threshold of p<0.05 indicating statistical significance.

4.3. Period-Specific Analysis

2003-2008 (Pre-Crisis): This period involved analyzing the relationship between economic growth and rising income inequality, as Greece experienced a phase of economic expansion before the financial crisis.

2009-2014 (Crisis/Memoranda): The focus here was on the impact of the economic crisis and austerity measures on income inequality. The strong negative relationship observed between GDP and the Gini coefficient during this period highlighted the exacerbation of inequality due to economic contraction.

2015-2020 (Post-Crisis): In this period, the analysis explored the effects of economic recovery on inequality, with particular attention to the weaker relationship between GDP and the Gini coefficient, reflecting ongoing structural challenges in the Greek economy.

4.4. Evaluation of Results

Model Fit: The model fit was evaluated using R-square and Adjusted R-square values, along with the F-statistic from the ANOVA table. These metrics provided insights into how well the model explained the variation in income inequality for each period.

Residual Analysis: Residual statistics and the Durbin-Watson statistic were used to check for autocorrelation and validate the assumptions of the regression model.

4.5. Limitations

Data Limitations: The analysis is limited by the availability of data for certain years and periods. Additionally, while GDP is a key indicator of economic activity, it may not capture all the factors affecting income inequality, such as tax policies, labor market conditions, and social safety nets.

Model Assumptions: The linear regression model assumes a linear relationship between GDP and the Gini coefficient, which may not fully capture the complexity of the relationship in different economic contexts.

The methodological framework outlined above provides a structured approach to analyzing the relationship between GDP and income inequality in Greece over three distinct periods. By combining descriptive statistics, correlation analysis, and linear regression, the study sheds light on how economic growth and contraction have impacted income distribution in Greece, offering valuable insights for policymakers and researchers alike.

4.6. Methodological Rationale and Variable Justification

Correlation Analysis: Pearson correlation coefficients were applied to assess the strength and direction of the relationship between GDP and income inequality, offering a clear view of whether a positive or negative relationship exists between these two variables across different time periods.

Linear Regression Models: Linear regression was selected to provide a deeper understanding of how changes in GDP influence income inequality, allowing the study to measure the extent to which variations in GDP explain fluctuations in the Gini coefficient. This method was well-suited to test the hypotheses related to the economic conditions of each period.

Gross Domestic Product (GDP): GDP was chosen as the independent variable because it represents the overall economic performance of Greece and provides insight into how economic growth or contraction influences income distribution. As a key economic indicator, GDP allows for the examination of macroeconomic trends that directly impact inequality.

Gini Coefficient: The Gini coefficient was selected as the dependent variable due to its established role as a reliable measure of income inequality. This coefficient reflects the distribution of income within the population, making it the ideal metric for tracking changes in inequality over time.

2003-2008 (Pre-Crisis): This period was characterized by significant economic growth driven by public spending and borrowing. It is important to analyze this phase to understand how periods of economic expansion influence income distribution, particularly before the onset of financial instability.

2009-2014 (Crisis/Memoranda): Marked by the global financial crisis and austerity measures, this period is critical for studying the impact of economic contraction on income inequality. The financial hardships and high unemployment rates during this time offer a unique opportunity to evaluate how inequality shifts during economic downturns.

2015-2020 (Post-Crisis): Following Greece’s recovery from the bailout programs, this period examines whether the resumption of GDP growth led to meaningful reductions in income inequality or if structural issues persisted. The analysis of this recovery phase helps assess the long-term effects of economic crises on inequality.

5. Conclusions

The primary purpose of this study was to examine the diachronic relationship between Gross Domestic Product (GDP) and income inequality, as measured by the Gini coefficient, in Greece over three distinct periods: the pre-crisis period (2003-2008), the crisis and memoranda period (2009-2014), and the post-crisis period (2015-2020). By analyzing these different economic phases, this research aimed to uncover how economic growth, contraction, and recovery have impacted income distribution in Greece and to draw relevant conclusions for both academic understanding and policy formulation.

The main findings of the study reveal that the relationship between GDP and income inequality varies significantly across the three periods. In the pre-crisis period, while GDP growth was moderate, it was accompanied by rising income inequality, although this relationship was not statistically significant. This suggests that the economic expansion did not equitably benefit all segments of society, and the benefits of growth were unevenly distributed. During the crisis and memoranda period, the study identified a strong and statistically significant negative relationship between GDP and the Gini coefficient. The economic contraction, driven by austerity measures, significantly exacerbated income inequality, disproportionately affecting lower-income households. In the post-crisis period, despite the resumption of GDP growth, the relationship between GDP and inequality weakened and became statistically insignificant. This indicates that the recovery was insufficient to address the deep-rooted structural inequalities that persisted in the Greek economy.

Based on these findings, several policy recommendations emerge. First, to address the persistent income inequality observed across different periods, policymakers should prioritize social protection measures that target the most vulnerable populations. Strengthening social safety nets, such as unemployment benefits and social assistance programs, can help mitigate the adverse effects of economic downturns on lower-income households. Second, structural reforms that promote inclusive growth are essential. Policies that reduce labor market segmentation, promote job creation, and enhance access to education and training can help ensure that the benefits of economic recovery are more widely shared. Third, progressive taxation should be considered as a means of redistributing income and reducing inequality. By implementing tax policies that target wealthier individuals and corporations, the government can generate the necessary revenue to fund social programs and reduce income disparities.

Tsitouras and Papapanagos’s (2022) study concludes that economic freedom should be viewed as a significant long-term goal for policymakers aiming to reduce income inequality. However, in the short term, economic growth is found to be more effective in promoting income equality. This distinction is crucial for developing targeted economic policies that address both immediate and long-term challenges. According to Mitrakos (2004) addressing educational inequalities is crucial for mitigating economic disparities in Greece and other EU-15 countries. By implementing targeted educational policies, it may be possible to foster a more equitable economic landscape.

To effectively address income inequality in Greece, policymakers should adopt a dual strategy that focuses on both short-term and long-term goals (Migkos et al., 2022). In the short term, promoting economic growth is crucial for immediate reductions in income disparities. However, for sustained improvements, increasing economic freedom should be a significant long-term objective. Additionally, addressing educational inequalities through targeted policies is essential for fostering a more equitable economic landscape. By improving access to quality education and enhancing economic freedom, Greece can create the conditions necessary for reducing income inequality both now and in the future.

The significance of this study lies in its comprehensive analysis of the complex relationship between economic performance and income inequality in Greece across different economic phases. By providing a diachronic examination of this relationship, the study contributes to a deeper understanding of how economic policies and external shocks impact income distribution. This research also highlights the need for targeted policy interventions to address inequality, particularly during periods of economic crisis and recovery. The findings of this study have broader implications for other countries facing similar economic challenges, as they underscore the importance of balancing economic growth with social equity.

Looking ahead, future research should focus on exploring the impact of specific policy measures on income inequality in Greece. For instance, examining the effects of labor market reforms, tax policies, and social welfare programs on income distribution could provide valuable insights for policymakers. Additionally, more granular analyses that consider regional disparities and the experiences of different demographic groups would offer a more nuanced understanding of inequality in Greece. Longitudinal studies that track the impact of economic policies over time would also be beneficial in assessing the effectiveness of various interventions.

Despite the contributions of this study, certain limitations must be acknowledged. The analysis primarily relied on GDP and the Gini coefficient as the key indicators of economic performance and inequality. While these measures provide valuable insights, they may not capture all aspects of inequality, such as wealth distribution or access to essential services. Furthermore, the study’s focus on Greece may limit the generalizability of the findings to other contexts. However, the choice to focus on Greece is justified given the country’s unique economic trajectory during the past two decades, making it a particularly valuable case study for examining the effects of economic crises and austerity measures on inequality. Additionally, the statistical methods employed, such as linear regression, assume a linear relationship between GDP and the Gini coefficient, which may not fully capture the complexity of the relationship. Despite these limitations, the study offers a robust analysis that contributes to the ongoing discourse on economic inequality and provides actionable insights for policymakers.

In conclusion, this study underscores the critical need for policies that address income inequality, particularly in times of economic crisis and recovery. By prioritizing social equity alongside economic growth, policymakers can help ensure that the benefits of economic progress are shared more broadly across society. Future research should continue to explore the intersection of economic performance and inequality, with a focus on identifying effective policy interventions that promote both growth and fairness.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org. Mendeley Data Base (Karountzos, 2024).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.K., N.T.G., D.P.S., S.P.M., and K.I.E.; methodology, P.K., N.T.G., D.P.S., S.P.M., and K.I.E.; software, P.K., N.T.G., D.P.S., S.P.M., and K.I.E.; validation, P.K., N.T.G., D.P.S., S.P.M., and K.I.E.; formal analysis, P.K., N.T.G., D.P.S., S.P.M., and K.I.E.; investigation, P.K., N.T.G., D.P.S., S.P.M., and K.I.E.; resources, P.K., N.T.G., D.P.S., S.P.M., and K.I.E.; data curation, P.K., N.T.G., D.P.S., S.P.M., and K.I.E.; writing—original draft preparation, P.K., N.T.G., D.P.S., S.P.M., and K.I.E.; writing—review and editing, P.K., N.T.G., D.P.S., S.P.M., and K.I.E.; visualization, P.K., N.T.G., D.P.S., S.P.M., and K.I.E.; supervision, P.K., N.T.G., D.P.S., S.P.M., and K.I.E.; project administration, P.K., N.T.G., D.P.S., S.P.M., and K.I.E.; funding acquisition, P.K., N.T.G., D.P.S., S.P.M., and K.I.E. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Dataset available on request from the authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Alves, José, Coelho, Jose C., and Roxo, Alexandre. 2022. How Economic Growth Impinges on Income Inequalities? CESifo Working Paper No. 10154: 1-27. [CrossRef]

- Andriopoulou, Eirini, Karakitsios, Alexandros, and Tsakloglou, Panos. 2018. Inequality and poverty in Greece: Changes in times of crisis. In: Katsikas, D., Sotiropoulos, D., Zafiropoulou, M. (eds) Socioeconomic Fragmentation and Exclusion in Greece under the Crisis. New Perspectives on South-East Europe. Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 23-54, Cham. [CrossRef]

- Arghyrou, Michael G., and Tsoukalas, John D. 2011. The Greek debt crisis: Likely causes, mechanics and outcomes. The World Economy 34(2): 173-191. [CrossRef]

- Atkinson, Anthony B. 2015. Inequality: What Can Be Done? Harvard University Press.

- Balakrishnan, Ravi, Steinberg, Chad, and Syed, Murtaza H. 2013. The elusive quest for inclusive growth: Growth, poverty, and inequality in Asia. International Monetary Fund.

- Bourguignon, Francois. 2015. The Globalization of Inequality. Princeton University Press.

- Christopoulou, Rebekka, and Monastiriotis, Vassilis. 2019. Sectoral returns in the Greek labour market over 2002–2016: Dynamics and determinants. In Horen Voskeritsian, Panos Kapotas, Christina Niforou (eds.) Greek Employment Relations in Crisis, 59-82. Routledge. [CrossRef]

- Christopoulou, Rebekka, and Monastiriotis, Vassilis. 2016. The Greek Public Sector Wage Premium before and after the Crisis: Size, Selection and Relative Valuation. British Journal of Industrial Relations 52(3): 579-602. [CrossRef]

- Coffey, Clare, Espinoza Revollo, Patricia, Harvey, Rowan, Lawson, Max, Parvez Butt, Anam, Piaget, Kim, Sarosi, Diana, and Thekkudan, Julie. 2020. Time to Care: Unpaid and underpaid care work and the global inequality crisis. Oxfam. Available online: https://fly.jiuhuashan.beauty/https/dx.doi.org/10.21201/2020.5419 (accessed on 12 June 2024).

- Collignon, Stefan. 2012. Macroeconomic imbalances and comparative advantages in the Euro Area. ETUI.

- Dabla-Norris, Era, Kochhar, Kalpana, Suphaphiphat, Nujin, Ricka, Frantisek, and Tsounta, Evridiki. 2015. Causes and consequences of income inequality: A global perspective. International Monetary Fund.

- Darvas, Zsolt, and Wolff, Guntram B. 2016. An anatomy of inclusive growth in Europe. Bruegel Blueprint Series 26, October 2016. Available online: chrome-extension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/https://www.bruegel.org/system/files/wp_attachments/BP-26-26_10_16-final-web.pdf (accessed on 10 June 2024).

- Faggian, Alessandra, Michelangeli, Alessandra, and Tkach, Kateryna. 2023. Income inequality in Europe: Reality, perceptions, and hopes. Research in Globalization 6: 100118. [CrossRef]

- Fasianos, Apostolos, and Tsoukalis, Panos. 2023. Decomposing wealth inequalities in the wake of the Greek debt crisis. The Journal of Economic Asymmetries 28: e00307. [CrossRef]

- Featherstone, Kevin. 2008. Varieties of Capitalism and the Greek Case: Explaining the Constraints on Domestic Reform? Hellenic Observatory Papers on Greece and Southeast Europe No. 11. Available online: chrome-extension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/https://eprints.lse.ac.uk/5608/1/GreeSE%2520No11.pdf (accessed on 17 June 2024).

- Giannitsis, Tassos, and Zografakis, Stavros. 2018. Crisis management in Greece, 58-2018. IMK at the Hans Boeckler Foundation, Macroeconomic Policy Institute.

- Kalleitner, Fabian, and Bohmann, Sandra. 2023. The inequity Z: Income fairness perceptions in Europe across the income distribution. Socius 9: 23780231231167138. [CrossRef]

- Kaplanoglou, Georgia. 2022. Consumption inequality and poverty in Greece: Evidence and lessons from a decade-long crisis. Economic Analysis and Policy 75: 244-261. [CrossRef]

- Karountzos, Panagiotis 2024. Econometric Analysis of GDP and Income Inequality in Greece: A Diachronic Study Across Pre-Crisis, Crisis, and Post-Crisis Periods, Mendeley Data, V1, doi: 10.17632/3nv5hcvy45.1.

- Kolluru, Mythili, and Semenenko, Tetiana. 2021. Income inequalities in EU countries: GINI indicator analysis. Economics 9(1): 125-142.

- Kotsios, Panagiotis. 2022. Income Inequality Measurements through Tax Data: the case of Greece. Bulletin of Applied Economics 9(2): 175-187. [CrossRef]

- Koutsoukis, Nikitas S., and Roukanas, Spyros A. 2014. The GrExit Paradox. Procedia Economics and Finance 9: 24-31. [CrossRef]

- Kuznets, Simon. 2019. Economic Growth and Income Inequality. Routledge, 1. 25-37.

- Matsaganis, Manos. 2020. Safety nets in (the) crisis: The case of Greece in the 2010s. Social Policy and Administration 54(4), 587-598. [CrossRef]

- Matsaganis, Manos, and Leventi, Chrysa. 2014. Poverty and Inequality during the Great Recession in Greece. Political Studies Review 12(2): 209-223. [CrossRef]

- Migkos, Stavros P., Damianos P. Sakas, Nikolaos T. Giannakopoulos, Georgios Konteos, and Anastasia Metsiou. 2022. Analyzing Greece 2010 Memorandum’s Impact on Macroeconomic and Financial Figures through FCM. Economies 10(8): 178. [CrossRef]

- Milanovic, Branko. 2016. Global Inequality: A New Approach for the Age of Globalization. Harvard University Press.

- Missos, Vlassis, Blunt, Peter, Domenikos, Charalampos, and Pontis, Nikolaos. 2024. Inflated inequality or unequal inflation? A case for sustained ‘two-sided’austerity in Greece. European Journal of Economics and Economic Policies 1(aop): 1-20. [CrossRef]

- Mitrakos, Theodore. 2004. Education and economic inequalities. Bank of Greece Economic Bulletin 23(2): 1-20. https://ssrn.com/abstract=4163610.

- Mitrakos, Theodore. 2014. Inequality, poverty and social welfare in Greece: Distributional effects of austerity. Bank of Greece Working Paper No. 174: 1-36. [CrossRef]

- Nikolić, Stefan, Novokmet, Filip, and Larysz, Piotr P. 2024. Income inequality in Eastern Europe: Bulgaria and Czechoslovakia in the twentieth century. Explorations in Economic History 94: 101594. [CrossRef]

- Ostry, Jonathan D., Berg, Andrew, and Tsangarides, Charalambos G. 2014. Redistribution, inequality, and growth. International Monetary Fund.

- Papanastasiou, Stefanos, and Papatheodorou, Christos. 2018. The Greek depression: Poverty outcomes and welfare responses. Journal of Economics and Business, 21(1-2): 205-222.

- Petrakos, George, Konstantinos Rontos, Chara Vavoura, and Ioannis Vavouras. 2023. The impact of recent economic crises on income inequality and the risk of poverty in Greece. Economies, 11(6): 166. [CrossRef]

- Piketty, Thomas. 2014. Capital in the Twenty-First Century. Harvard University Press.

- Psycharis, Yannis, Georgiadis, Thomas, and Nikolopoulos, Panagiotis. 2023a. The geographical dimension of income and consumption inequality: Evidence from the Attica Metropolitan Region of Greece. Region: the journal of ERSA, 10(1): 183-197.

- Psycharis, Yannis, Tselios, Vassilis, and Pantazis, Panagiotis. 2023b. The geographical dimension of income inequality in Greece: evolution and the ‘turning point’ after the economic crisis. Regional Studies, Regional Science, 10(1): 798-819.

- OECD. (2011). An overview of growing income inequalities in OECD countries: main findings. Divided we stand: Why inequality keeps rising, 21-45. Available online: chrome-extension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/http://www.i-red.eu/resources/publications-files/oecd-divided-we-stand.pdf (accessed on 15 June 2024).

- Stiglitz, Joseph E. 2012. The Price of Inequality: How Today’s Divided Society Endangers Future. W.W. Norton and Company.

- Tsitouras, Antonis, and Papapanagos, Harry. 2022. Income Inequality, Economic Freedom, and Economic Growth in Greece: A Multivariate Analysis. In International Conference on Applied Economics: 485-503. Cham: Springer International Publishing. [CrossRef]

- World Bank. 2024. World bank open data. Available online: https://data.worldbank.org/ (accessed on 10 June 2024).

- Yfantopoulos, John, Chantzaras, Athanasios, and Yfantopoulos, Platon. 2023. The health gap and HRQoL inequalities in Greece before and during the economic crisis. Frontiers in Public Health 11: 1138982. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).