1. Introduction

This study centres on the interplay between formative traits, those that characterise agencies, avatars of the complex adaptive systems that operate as living systems with an adaptive capacity for autonomous intentional action in their changing environments [

1]. Navigating an era of complex social phenomena and rapid technological advance, it becomes increasingly important to understand how these formative traits mutually interact. They are susceptible to environmental change, including technological advancements that have revolutionised access to information and connectivity. The traits, which define agency character, also determine agency potential for action, are subject to the transformative effects in a changing environment that includes digital tools and platforms.

The paper employs Mindset Agency Theory (MAT) to examine how agency traits, influenced by affective and cognitive factors, interact to shape behaviour. MAT views agency through a cybernetic lens, suggesting that traits exist in dynamic and polar states, responding reflexively to environmental stimuli. This framework is used to explore how new technologies can impact core beliefs and self-efficacy beliefs, thereby influencing agents' agency.

MAT posits that agency traits are adaptive and can evolve in response to environmental changes like the emergence of new technologies. These technologies have the potential to reshape foundational traits underlying agency, affecting how agents perceive and respond to their environment. Core beliefs (fundamental assumptions about oneself and the world) and self-efficacy beliefs (confidence in one's ability to perform tasks) are critical aspects of agency that can be significantly influenced by technological advancements. By integrating beliefs into MAT, the paper enhances the theory's explanatory scope. Traditionally, MAT has focused on traits without explicitly considering beliefs as configurable aspects. By formally configuring MAT to include beliefs, the theory becomes more comprehensive, allowing for a detailed exploration of how beliefs interact with other formative traits and values in a digitally interconnected world. MAT's perspective on the adaptive capacity of agencies suggests that agents can self-organise and adapt their beliefs and behaviours in response to technological changes. For example, exposure to new technologies may bolster self-efficacy beliefs by providing tools and platforms for skill development and achievement. Conversely, technological advancements could challenge existing core beliefs by introducing new paradigms or disrupting established norms. This illustrates the importance of explicitly treating beliefs as formative traits with formal relationships to other traits. Such an approach is essential for comprehensively examining how agents navigate and adapt to the complexities of a modern, technology-driven society.

Agency may be considered to be composed of a population of agents together creating a complex web of mutual interactions able to adaptively respond to their environments. This is a characteristic complexity that reflect the theoretical underpinnings of complex adaptive systems. Such systems are composed of numerous interacting agents, each possessing unique traits and motivations, and they exhibit emergent properties – unforeseen consequences that arise from the collective behaviour of the system's constituent elements. These elements are distinguished through two dualities, the tangible-intangible duality and the affect-cognition duality. By exploring these dualities within the framework of the MAT framework, a deeper understanding of how agents interact with their environment can emerge explain how their internal states influence their behaviour and the trajectory of the agency structure they inhabit.

MAT, as a trait theory, is capable of characterising the interactive intangible properties of agency that influence behaviour. It currently has twelve traits to do this that influence agency behaviour within the two domains of affect and cognition, but it lacks a clear framework for incorporating beliefs. To bridge this gap, this study seeks to assimilate established candidate belief theories into MAT. Configuring selected theories for this will consume much of this paper. By selecting theories that align with MAT’s structure, a clearer understanding of the interplay between technology, beliefs, values, and their subsequent effects can develop. Two belief theories are relevant, that relating to Bandura’s [

2] notion of self-efficacy beliefs which are fundamentally cognitive processes, and core beliefs which fall between cognition and affect. Core beliefs inherently contain a cognitive component. This is because they are essentially cognitive constructs—they are the fundamental convictions and assumptions we hold about ourselves, others, and the world around us [

3]. These beliefs are formed through experiences and interpretations of those experiences, which are cognitive processes, and are formed through learning, reasoning, and interpreting experiences. They are maintained by cognitive biases that filter information to confirm these beliefs [

4]. They influence the cognitive appraisal of situations, which in turn affects emotional responses. The appraisal process is cognitive and involves evaluating whether something is a threat, loss, or challenge, based on one’s core beliefs. While core beliefs can trigger emotional responses, it is the cognitive interpretation of events, filtered through these beliefs, that often gives rise to emotions.

However, core beliefs can be assigned to the affect domain due to their impact on emotional well-being [

5]. This can be rationalised by understanding the intrinsic link between core beliefs and affect. Core beliefs are fundamental perceptions about oneself, others, and the world that are developed early in life and are central to our emotional well-being [

6]. They are often automatic and can significantly influence emotional reactions in various situations. The nature of this is that core beliefs are important for emotional regulation, able to trigger emotional responses and influence the intensity and duration of these emotions [

7]. The affective domain encompasses emotions and feelings, and core beliefs are often the underlying cause of affective responses. Negative core beliefs can predispose agents to experience negative emotions more frequently and intensely [

8]. Core beliefs can predict affective states, so that someone with a pessimistic core belief about the future (“Things will never work out for me”) is more likely to experience anxiety and hopelessness [

9]. While self-efficacy beliefs are assigned to the cognitive domain due to their relation to perceived capabilities and decision-making, core beliefs are more aligned with the affect domain because they are closely tied to one’s emotional experiences and self-concept. By assigning core beliefs to the affect domain, the significant impact these deeply held convictions have on emotions and feelings is acknowledged, which is consistent with the domain’s focus on emotional processes and states. This alignment facilitates a more comprehensive understanding of the interplay between beliefs and emotions, which is essential for development and psychological interventions. The e affective domain involves how agents internalise beliefs and allow them to guide behaviour. As beliefs become more deeply ingrained, they move from simple awareness to becoming a part of the agent’s value system, ultimately influencing and characterising consistent behaviour [

10].

Through MAT, the paper seeks to elucidate how technology intersects with agency core beliefs, self-efficacy beliefs, and cognitive values. Through a comprehensive examination of empirical research, theoretical frameworks, and practical illustrations, the study aims to uncover the intricate mechanisms through which technology influences affective and cognitive processes, shapes belief systems, and impacts agency behaviour. To do this a structured approach will be followed in this paper that explores the influence of technology on agency. After this introductory overview, emphasis will be assigned to considering the role of technology in shaping beliefs, values, and agency. Moving on, a narrative will be offered on the nature of the new technologies of social media and AI, followed by looking at the nature of core beliefs and how they different from self-efficacy beliefs. MAT and its developmental trajectory will then be examined, delineating its foundational elements and highlighting the absence of explicit consideration for belief within its framework. The configuration of belief theories will then be undertaken. Subsequently, the paper explores how technology indirectly impacts fundamental beliefs and values, distinguishing between core beliefs and self-efficacy beliefs. It elucidates the mechanisms through which technology shapes perceptions, social dynamics, and societal norms, paving the way for the proposed integration of these insights into the MAT framework. This integration, facilitated through a configuration approach, is posited to enhance our comprehension of agency in the digital era. Finally, some consideration is given to pragmatic contexts prior to a conclusion. This will look at Hungary, identifying its background, and exploring how it has used social media and AI to promote its illiberal political regime.

3. Mindset Agency Theory

Complex adaptive systems operate through agency, the ability to act with intention, make choices, and exert influence within an environment. MAT, grounded in cybernetics, is designed to represent agency through a metatheoretical framework designed to analyse and diagnose agency issues. It conceptualises agencies and their population of agents as diverse and recognises its capacity to adapt and maintain stability within a changing environment. MAT I a trait theory that started with 10 formative traits that defined agency character across affective and cognitive domains [

1]. These included two sociocognitive traits (cognitive style and cognitive values), and three dispositional traits. This as amended by Yolles and Rautakivi [

28] (2024) to include in cognition with cognitive style the trait of social organisation. Then Yolles [

29] upgraded the affect domain to include physiological arousal and cognitive interpretation. Despite the interconnectedness between cognition and affect, the current framework lacks explicit consideration of belief. Here we address this gap by examining how technology influences fundamental beliefs and values, ultimately shaping agency.

By distinguishing between core beliefs and self-efficacy beliefs and integrating them into MAT, we can achieve a more holistic understanding of the environmental factors influencing agency. Core beliefs can align with specific cognitive styles. For example, a person with a core belief in openness may exhibit a more exploratory cognitive style. Confirmation bias, where agents favour information that confirms existing beliefs, can also be influenced by core beliefs. Self-efficacy beliefs interact with cognitive styles in various ways. Agents with high self-efficacy are more likely to approach tasks with confidence, aligning with a proactive cognitive style. Conversely, low self-efficacy can lead to task avoidance, fostering a more passive approach. Similarly, core beliefs and self-efficacy beliefs shape social organization traits. Core beliefs emphasising individualism may lead towards Gesellschaft, while those emphasizing community may resonate with Gemeinschaft.

To this framework Yolles and Fink then applied the ideas of Sagiv and Schwartz [

38], transforming CAT into MAT. Sagiv and Schwartz’s work is pivotal in understanding values and their impact on behaviour and well-being. Their research explores the direct relationships between different types of values and subjective well-being, and postulate that well-being is influenced not only by the types of values an agent holds but also by the congruence between personal values and the prevailing value environment. This, in the context of Maruyama’s Mindscape theory, contribute to a trait theory perspective by providing a structured way to categorise and understand how values influence agency dispositions. Thus, values are not just abstract ideals but have concrete implications for how agencies and their agents perceive the world and react to it. This aligns with the holistic cybernetic approach of Mindscape theory [

39] which seeks to model and analyse the complex interplay between psychological factors, sociopolitical dynamics, and organisational change. The outcome from these theoretical configurations has been a formalised trait theory that accounts for the dynamic nature of values within agencies. This allows for a more flexible representation of agency dispositions, acknowledging that values and the contexts in which they operate are crucial in shaping behaviour and decision-making processes within complex adaptive systems. Additionally, the four essentially cognitive mindscape distinctions that Maruyama identified have been shown to be directly derivable from MAT, together with four additional Mindset distinctions.

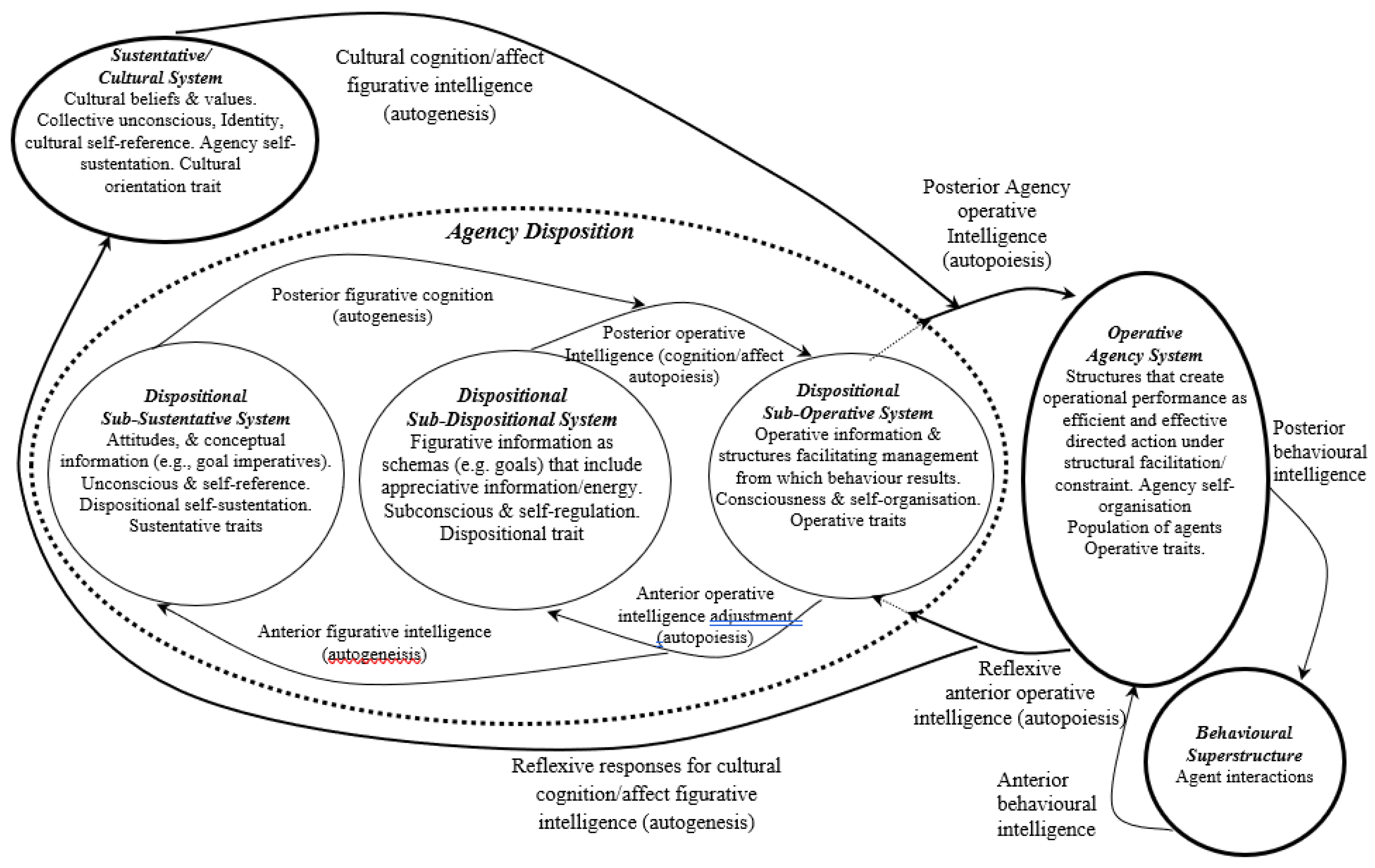

Figure 1 offer a framework that captures the dynamic and recursive nature of complex adaptive systems that can also be recognised as general living systems when expressed in terms of Varela’s [

40] concept of autopoiesis. Autopoiesis is a self-production process that operates as a process intelligence, this referring to the networks within an agency that select, process, and manifest elements from one system into another, facilitating an agency flow of information and energy. The model is substructural in the sense that its contents are intangible and their interactions create imperatives for superstructural behaviour. Thus, complex systems arise from the interaction of sub-agencies, which are part of a larger fractal structure. The fractal metaphor suggests that these systems repeat across different levels, each defining a specific sub-context of agency. The operative system is a fabric of information that parametrically describes the relationship between agency internal and external parameters. Behaviour is determined when any of its attributes are activated given the appropriate conditions, thereby delivering agency responses to external stimuli and is part of the process intelligences that facilitate action. The dispositional system is a strategic and regulatory structure that represents how the agency processes information and expresses emotions. It shapes social relationships and interactions, influencing agency regulation and behaviour. This system is also a key component of process intelligences, as it involves transforming information into meaningful patterns. The sustentative system supports agency sustainability. This model incorporates the concepts of operative and figurative intelligence, which are derived from Piaget’s theory of cognitive development [

41]. Piaget described operative intelligence as responsible for the representation and manipulation of the dynamic aspects of reality. Operative intelligence is a representation autopoiesis, which refers to the self-creation and maintenance of living systems, and Schwarz’s autogenesis, which describes the self-organising processes of systems. For Piaget, figurative intelligence deals with the static aspects of reality, though here it is regarded as a second order form of autopoiesis. By autopoiesis is meant the system’s ability to maintain and recreate itself, while figurative intelligence relates to the system’s structure and information processing (autogenesis). This integration allows the theory to model complex, real-world situations and anticipate patterns of behaviour, providing a comprehensive framework for understanding the dynamics of agency dispositions within a holistic cybernetic approach.

Figure 1.

Mindset Agency Theory Substructural Model (with appended superstructure), where Agency Fractal is embedded in the Dispositional Sys.

Figure 1.

Mindset Agency Theory Substructural Model (with appended superstructure), where Agency Fractal is embedded in the Dispositional Sys.

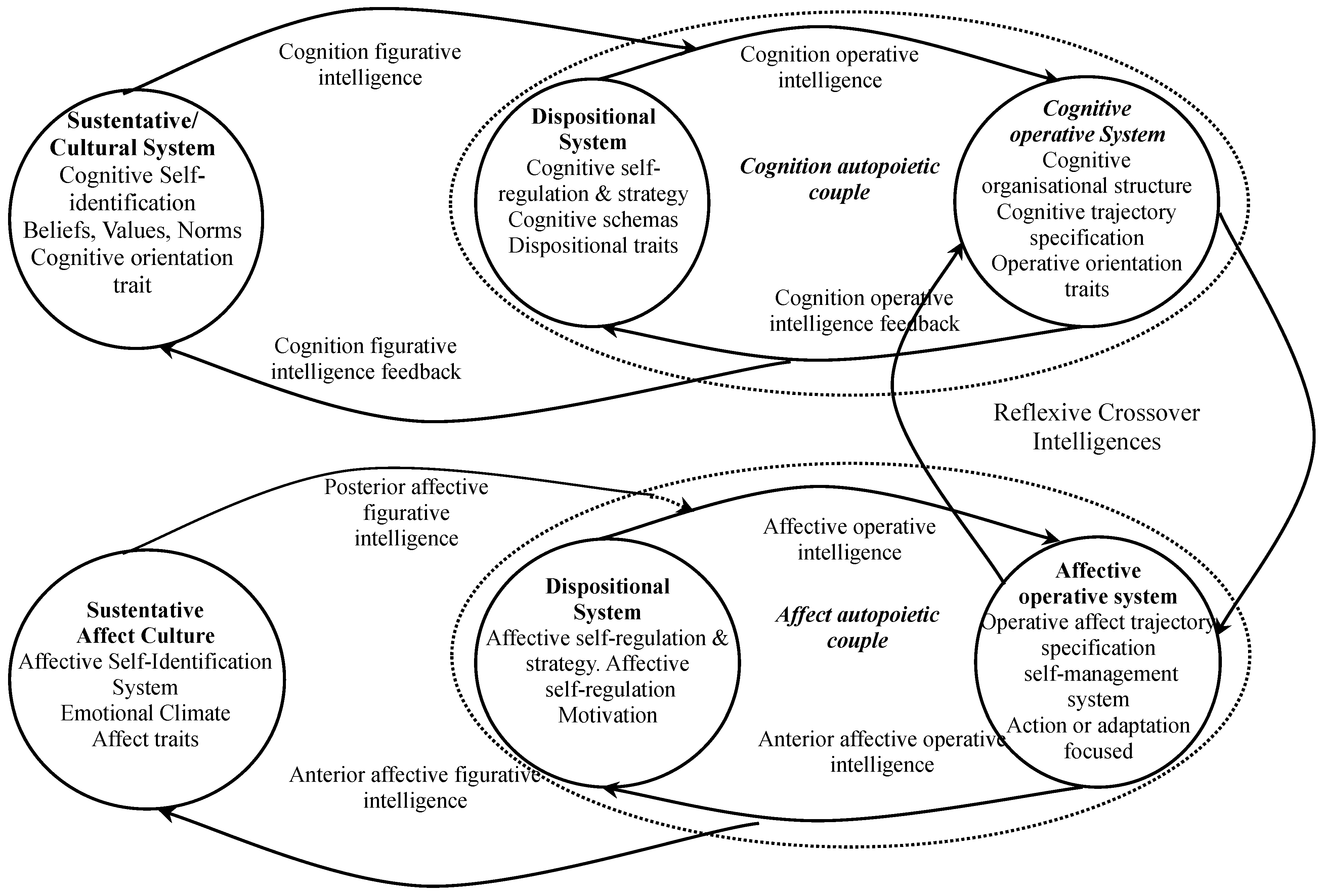

This figure may be seen as a model of cognition, where the process intelligences provide information flow between the different systems indicated, thus satisfying Maruyama’s primary interest in cognition, while essentially neglecting affect. Drawing on the ideas of Gross [

42] there should be a similar structure as in

Figure 1 relating to affect. In

Figure 2 we show the relationship between the affect and cognition systems where cognition and affect exchange information an energy through their affective-cognition intelligences.

The intelligences that connect the affect operative system to the cognitive operative system are referred to as Crossover Intelligence that Gross has indicated refers to the affect-cognition interrelationship. This form of intelligence represents the processes that bridge affect processes with cognition ones enabling cross-over to develop. It encapsulates the dynamic and reciprocal influence of emotions on cognitive operations within an agency, highlighting the integral role of affect in shaping cognitive responses to environmental stimuli. MAT may be seen as belonging to the realm of organisational psychology. This framework identifies the intricacies of how agencies acquire and process information. At its heart lies the cognitive style trait, characterized by bipolar values of Patterning and Dramatising. This trait serves as a lens through which to understand how agencies perceive and interpret information, shedding light on the myriad cognitive approaches that shape their decision-making processes. Whether agencies lean towards structured patterns or thrive in the realm of dynamic narratives, MAT unveils the cognitive diversity that permeates organizational dynamics. Its scope also extends beyond agent cognition to encompass the broader social fabric within which agencies operate. Drawing upon Ferdinand Tönnies' [

43] theory of social organisation, MAT distinguishes between Gemeinschaft (community) and Gesellschaft (society) as types of social relationships. By integrating these concepts, MAT unveils the intricate social dynamics that underpin agency interactions, offering insights into the forces that shape their coherence and functionality.

Figure 2.

MAT Model Showing Interactions between Cognition and Affect.

Figure 2.

MAT Model Showing Interactions between Cognition and Affect.

As a diagnostic tool, MAT emerges as a beacon of clarity amidst the complexities of organisational behaviour. By linking trait instabilities with agency pathologies such as narcissism and paradoxical behaviour, MAT enables practitioners to pinpoint dysfunctions within agencies and chart a course towards coherence and functionality. Whether grappling with issues of leadership efficacy or grappling with cultural clashes, MAT provides a roadmap for navigating the labyrinthine landscape of organisational psychology. Its applicability transcends cultural boundaries, making it an invaluable tool for diagnosing complex agencies with diverse cultural milieus. By offering insights into how cultural diversity impacts agency behaviour, MAT empowers practitioners to navigate the nuances of cross-cultural dynamics with finesse and precision. In the ever-evolving landscape of agency psychology, MAT stands as a testament to the power of cognitive exploration. With its incorporation of cognitive styles, its integration of social organisation theory, and its diagnostic capabilities, MAT becomes more than useful in exploring agency coherence and functionality in complex environments.

MAT is a formative trait theory so far identifying 6 traits for cognition, 1 of which is cultural values, 3 are cognition dispositional traits, and the last 2 are operative traits designated as cognitive style, and social organisation. Cognitive style refers to an agent’s preferred way of processing information, making decisions, and approaching problem-solving, and within MAT it is characterized by the bipolar values of Patterning–Dramatising. Patterning emphasises structured tangible systematic thinking, while the Dramatising leans toward intuitive intangible creative thinking. Cognitive style influences how agencies acquire, process, and interpret information, shaping their trajectory formation (decision-making and strategic planning processes). Social organisation focuses on an agency’s relationships with others and its position within social structures. It considers how agencies interact with their environment, collaborate with other entities, and navigate social dynamics. It also plays an important role in determining an agency’s influence, access to resources, and ability to achieve its goals. Within MAT, understanding an agency’s social organisation sheds light on its network of connections, alliances, and affiliations. These two traits—cognitive style and social organisation—provide valuable insights into an agency’s mindset, behaviour, and capacity for purposeful action. By examining how agencies acquire information and navigate social contexts, MAT contributes to a deeper understanding of human agency within diverse cultural settings.

3.2. Beliefs and Values as Traits

The sustentative dimension of agency underscores the significance of beliefs which, along with cognitive values and emotional climate, are foundational to culture. Of the two classes of belief that our interest extends to, consideration will first be applied to cognition self-efficacy. The Active polar value state influences dispositional tendencies, structural organization, and behavioural patterns. These beliefs, reflecting an ability to manage tasks and face challenges, are important to processes of adaptation under change. Its interaction with Sensate cognitive values can lead to direct and measurable results. In contrast, when aligned with Ideational values, which emphasise abstract and intangible concepts, Active self-efficacy can promote intellectual enrichment and a deeper grasp of ideas.

Latent self-efficacy beliefs [

44] are posited as a repository for prospective development and adaptation. Though not manifest, they possess the capacity to exert considerable influence and direct behaviour when catalysed by specific situational exigencies or impediments. They encapsulate a plethora of unrealized possibilities, each with its own likelihood of manifestation contingent upon the agent’s encounters with novel exigencies. Upon the advent of such exigencies, these latent beliefs may surface, proffering alternative modalities of cognition and action that resonate with the agent’s evolving self-schema and proficiencies. The dynamic nature of this latent potential is underscored by its susceptibility to a multitude of determinants, including intrinsic personal attributes, extrinsic environmental factors, and the trajectory of experiential accumulation. The actualisation of these latent beliefs is a probabilistic occurrence, sculpted by the intricate interplay of these multifarious influences. It is through this probabilistic prism that the transformative capacity of Latent self-efficacy beliefs in fostering agent growth and cultural progression can be comprehended.

The affect domain has core beliefs and emotional climate as formative traits. The polar value states of core belief are Active and Latent which are interactive and dynamic. Those of emotional climate are tangible Security, which nurtures an environment that bolsters Active core beliefs, and which leads to a proactive and confident approach to change. These beliefs, when engaged, propel agencies to embrace new challenges with assurance and vigour. Conversely, in a climate dominated by intangible Fear, Latent core beliefs may come to the forefront, prompting a more cautious and strategic approach. This emotional state encourages a reflective stance that contributes to an effective adaptation process.

Core beliefs, deeply rooted and affectively charged, play a pivotal role in shaping emotional responses and self-concept. These beliefs, through their synergy, direct behaviour, mould environmental engagement, and mediate the internalization of events, thereby informing the analytical process and enhancing diagnostic acumen. This dynamic is crucial in guiding strategic life trajectories and behaviours as noted by Madsen [

45]. The interplay between Sensate and Ideational value states within an agency belief system is marked by a fluidity that allows for shifts in dominance, reflecting evolutionary progressions. This fluidity is underpinned by the epistemological independence of the bipolar value states, which enables the coexistence of both reinforcing and contradictory beliefs within the same mental framework.

Beliefs, much like values, are fundamental components of culture. Affective core beliefs and cognitive self-efficacy beliefs provide agencies with the ability to hold contrasting belief states simultaneously. This dual capability, whether these beliefs are aligned synergistically or opposed antisynergistically, grants agencies the flexibility to navigate complex situations and reconcile conflicting information. It enables them to adapt their beliefs in response to changing circumstances and integrate diverse perspectives, fostering both affective and cognitive flexibility and enhancing creativity in problem-solving. By understanding the dynamic and multifaceted nature of affect and cognition, as well as considering the concept of epistemological independence, we gain insight into how agencies manage beliefs and shape future trajectories.

Beliefs, whether self-efficacy or core, embody dynamic characteristics that shape our cognitive landscape. When in a Latent state, beliefs demonstrate a fluid responsiveness to our interactions with the external environment. Not being static entities, they remain malleable and evolve with the accumulation of novel experiences and insights. Analogous to quantum superposition, beliefs can simultaneously embody multiple potential states, awaiting activation through lived encounters. Upon manifestation, they solidify into definitive convictions that not only influence but actively determine behaviour.

There are distinctions, however, with self-efficacy and core beliefs, where they each have distinct patterns. Self-efficacy beliefs exhibit a more transient nature, transitioning from potentiality to certainty in response to specific tasks or challenges. In contrast, core beliefs are deeply entrenched and resistant to swift alteration. Serving as the bedrock of our cognitive architecture, they shape our perceptions and responses on a fundamental level. Unlike self-efficacy beliefs, which may adapt relatively quickly, core beliefs often persist as enduring narratives, deeply etched into our psyche. These foundational convictions, once established, require sustained and transformative experiences to recalibrate. Thus, while self-efficacy beliefs teeter on the precipice of possibility, adapting to the intricacies of our lived experiences, core beliefs anchor us to our fundamental worldview, shaping the contours of our existence and guiding our interpretation of the world around us.

Returning to epistemological independence, this informs our understanding of trajectory forming processes (like decision-making in human societies), as agencies process competing beliefs and information. It highlights the importance of cognitive flexibility in adapting beliefs and strategies to fit the context. Epistemological independence has cultural implications, as it reflects cultural norms and values regarding belief diversity and tolerance for ambiguity. It underscores the importance of cultivating affective and cognitive flexibility and openness, both at the agency and agent levels, to navigate pragmatic complexities. By promoting an appreciation for diverse perspectives and encouraging critical thinking, epistemological independence lays the foundation for intellectual growth, innovation.

3.3. The Interplay Between Beliefs, Values, and Cultural Dynamics

The MAT framework provides a comprehensive lens through which to analyse the interplay between agency as created and defined by its population of agents, and the environment. Within this framework, agency traits, cognitive styles, and social organization are dissected across three distinct systems: Operative, Figurative, and Sustentative. The operative system encompasses traits related to an agent's cognitive style and social organization. Cognitive style, characterized by bipolar values such as tangible Dramatising and intangible Pattering, influences how agents process information and form trajectories. Social Organization, represented by values like tangible Gesellschaft and intangible Gemeinschaft, reflects the nature of an agent's social interactions and relationships. The pairing of these traits within the operative system indicates the coherence or incoherence of an agent's cognitive and social functioning. The figurative system comprises traits that shape agent disposition and character. While specific traits within this system are not elaborated on here, they contribute to the overall psychological agency makeup, influencing its attitudes, emotions, and behavioural tendencies. The sustentative (or cultural) system focuses on cultural values and norms that inform agent and collective behaviour. Originally featuring a cultural trait, the system primarily functions as a Values trait derived from Sorokin's distinction between Sensate and Ideational values. These values represent fundamental principles and ideals that guides agency behaviour and shapes cultural dynamics that impact its agents.

The MAT framework gains further depth by explicitly incorporating the concept of beliefs. This dynamic model recognises both tangible Active and intangible Latent beliefs, offering valuable insights into how agents perceive and interact with environmental influences. By examining the interaction between beliefs and values, we can identify patterns that influence agent and collective well-being and viability. The relationship between core/self-efficacy beliefs and cognitive values is intricate and bidirectional, playing pivotal roles in shaping an agent’s cultural identity and influencing their actions within society. Self-efficacy beliefs as an agency confidence to cognitively succeed at something. In contrast, core beliefs are deeply ingrained assumptions about oneself, others, and the world, and they serve as the affective foundation upon which agents build their perceptions and interpretations of reality. These beliefs form the lens through which agents view themselves and navigate their environments.

Beliefs may influence the formation and prioritisation of cognitive values, as an agent's perceptions of themselves and its abilities shape its moral and ethical frameworks. Positive beliefs can align closely with cognitive values, reinforcing and amplifying them [

46]. For example, beliefs in one's capability and competence can align with values such as perseverance and achievement, leading agents to prioritise goals and behaviours that reflect these values. Cognitive values can serve as validators for beliefs. When agents succeed in aligning their actions with their values and achieve desired outcomes, it reinforces their belief in their capabilities. This positive reinforcement strengthens both their core beliefs and cognitive values, creating a reinforcing cycle. Strong beliefs can also lead agents to reevaluate their cognitive values. For instance, strong agency belief strongly in an ability to overcome challenges and achieve success may result in the prioritising of values related to personal growth and resilience. Beliefs can also influence the selection of cognitive values. Agents with strong beliefs in their ability to lead and influence others may prioritize values related to leadership, such as integrity and responsibility. Their confidence in their capabilities may lead them to adopt and prioritize values that align with their perceived strengths.

Understanding the dynamic interaction between beliefs and cognitive values is essential for comprehending the complexities of cultural systems and their impact on agent agency and societal structures [

47]. It elucidates how beliefs and values contribute to the development of cultural identity and influence collective behaviours, attitudes, and social dynamics. Moreover, Recognising the bidirectional nature of this relationship informs interventions aimed at promoting adaptive beliefs and values that foster agent and societal well-being.

Core beliefs and self-efficacy beliefs are intertwined constructs that significantly influence an agent's cognitive processes, affective responses, and behavioural tendencies. Understanding their interaction within cultural dynamics provides valuable insights into identity formation, societal norms, and collective behaviours. The formation of self-efficacy as core beliefs often begins early in life, rooted in foundational experiences during childhood and adolescence. These experiences, such as successes, failures, and interactions with significant others, lay the groundwork for an agent's beliefs about their capabilities and worth. Self-efficacy intertwines with core beliefs, influencing and being influenced by deeply ingrained assumptions about oneself, others, and the world. Over time, positive self-efficacy beliefs can reinforce positive core beliefs, while negative self-efficacy beliefs may contribute to the formation of negative core beliefs. There exists dynamic reflexivity between self-efficacy and core beliefs, wherein each aspect continually informs and shapes the other. Positive experiences that affirm one's abilities bolster self-efficacy, reinforcing positive core beliefs, while negative experiences may challenge and potentially alter both self-efficacy and core beliefs.

The development of self-efficacy into core beliefs is intricately tied to environmental factors, spanning familial, social, cultural, and institutional contexts. Environments that cultivate encouragement, validation, and avenues for skill enhancement play a pivotal role in nurturing positive self-efficacy beliefs, which in turn bolster corresponding core beliefs. Both self-efficacy and core beliefs are dynamic constructs that evolve over time, shaped by ongoing experiences and shifting circumstances. Agents continually adjust their perceptions of their abilities and self-worth in response to environmental feedback and personal interpretations of their encounters. While self-efficacy can stem from core beliefs, it represents just one pathway among others. Core beliefs profoundly shape an individual's self-view and perspective on the world, while self-efficacy beliefs specifically revolve around confidence in accomplishing tasks and achieving goals. While core beliefs indirectly influence self-efficacy by shaping how agents interpret their experiences and assess their capabilities, self-efficacy beliefs can also develop autonomously, influenced by diverse factors such as past experiences, social interactions, and environmental cues. Thus, while core beliefs contribute to the formation of self-efficacy, they do not exclusively determine it, as self-efficacy can emerge through a blend of influences [

48].

Understanding the interconnectedness between core beliefs, self-efficacy beliefs, and cultural dynamics can likely provide valuable insights into human behaviour and societal norms. It underscores the importance of creating environments that support the development of positive self-efficacy beliefs and core beliefs, fostering resilience, well-being, and adaptive functioning in agents and communities. Additionally, Recognising the dynamic nature of these constructs informs culturally sensitive interventions aimed at promoting positive identity formation and psychological flourishing across diverse cultural contexts.

3.4. Polar State Interaction

Given that a formative trait exists that has bipolar value state, that are interactive and epistemically independent, then the relationship between the states in that interaction determines the properties adopted by that trait, and this contributes to agency character. We are aware that agency has 7 affect and 7 cognition traits, this giving 28 different polar states that, through mutual if indirect interaction, generates a highly complex matrix of influences. This paper has centred on 2 of new belief traits and their interaction with cognitive values to create the sustentative agency domain culture. It has been shown that the interaction between core and self-efficacy beliefs provides a number of possibilities that enable culture to be coherent. Coherence is required of culture is to perform its sustentative agency function. This is made much more complex when the considering the relationship between the bipolar value states. These can impart stability to the trait when the states are synergistic, but instability when they are antisynergistic, i.e., in conflict. As an illustration we can consider the very well-studied values trait originally proposed by Sorokin (1985) that was introduced in MAT at an early stage of its development.

The values trait in MAT is bipolar with two epistemically independent polar states, Sensate and Ideational. Pitirim Sorokin spent decades exploring the relationship between these values states, applying them to long-range temporal aspects of socioculture. But they are also relevant for short term. Their relationship may be synergistic when Sensate and Ideational values work together benefiting a sociocultural environment. They may also be or antisynegistic, when Sensate and Ideational values work against each other creating conflict. In the former case, the cultural values trait is stable, while in the latter it indicates instability. This trait has until now formed the basis of the sustentative mechanism in MAT, and value trait instabilities have been deemed to result in a lack of sustentative functionality that works against any possibility of agency homeostasis. In other words, agency becomes instrumental.

Sorokin’s theory suggests that agencies oscillate between Sensate and Ideational cultural states due to the ascendency and decline of each of the value states as they dynamically interact. A Sensate culture is one that values the material and the empirical, focusing on the here and now, with an emphasis on sensory experience [

49,

50,

51,

52]. It is characterised by a pursuit of material wealth, empirical knowledge, and sensory pleasure. On the other hand, an Ideational culture places value on the spiritual and the transcendent. It is less concerned with material possessions and more with moral and spiritual matters, seeking meaning beyond the physical world.

When these two value states are in balance, Sorokin referred to this as an Idealistic culture, which combines elements of both Sensate and Ideational cultures. This balance allows for a society that appreciates the material without losing sight of the spiritual, potentially leading to a stable and harmonious sociocultural environment. However, when there is a dominance of one value state over the other, or when the two are in conflict, it can lead to cultural instability. For instance, an overemphasis on Sensate values might lead to materialism and moral decay, while an overemphasis on Ideational values might result in neglect of practical concerns and a retreat from the world [

53].

Sorokin’s analysis of cultural dynamics is not just a historical or philosophical inquiry; it has practical implications for understanding societal changes and conflicts. It suggests that for a society to thrive, there must be a dynamic balance between the Sensate and Ideational values. This balance is crucial for the sustentative functionality of a society, which in turn supports agency homeostasis—the ability of agents and institutions to act effectively within their environment. In modern times, the relevance of Sorokin’s theory can be seen in the ongoing debates about the role of technology, the pursuit of economic growth versus sustainability, and the tension between individualism and community values. By understanding the interplay between Sensate and Ideational values, we can better navigate the complexities of our contemporary world and work towards a more balanced and stable society.

The relationship between Active and Latent self-efficacy beliefs, as well as Active and Latent core beliefs, can be understood in a similar interactive manner as the Sensate and Ideational aspects, though self-efficacy has been explored much more deeply. Active self-efficacy beliefs are those that are currently influencing behaviour; they are the beliefs that an agent is consciously aware of and is using to guide their actions. For example, a student who believes they are capable of achieving a high score on an exam (active self-efficacy belief) is likely to study diligently and approach the exam with confidence. Latent self-efficacy beliefs, on the other hand, are not currently active but can be activated by certain triggers or situations. These beliefs are part of an agency belief system but are not always at the forefront of their thoughts or actions. They can become active when the agency encounters a situation that calls for a specific belief to be applied.

Similarly, Active core beliefs are those that are currently shaping agency perception of itself and the world. These are deeply held beliefs that are actively influencing one’s thoughts and behaviours. For instance, if someone has an Active core belief that they are competent, this belief will colour their interactions and self-perception in various situations. Latent core beliefs are deeply held beliefs that are not currently influencing behaviour because they are not part of agency conscious awareness. However, they can become Active when triggered by specific events or emotional states. For example, someone may have a latent core belief of being unlovable, which may not usually affect their daily interactions but can become active and influence their behaviour during times of relationship stress. Latent core beliefs can deliver coping strategies during times of distress, which can in turn impact psychological health [

54].

Applying the same principles as used to examine the way in which values shift over time, it is feasible to consider the dynamic interaction between Active and Latent beliefs. Latent beliefs can become active depending on the context, and active beliefs can recede into latency when they are not relevant to the current situation. This dynamic is similar to the interplay between sensate (concrete, observable) and ideational (abstract, conceptual) aspects, where both influence an agent’s experience and behaviour, but their prominence can shift based on the context and demands of the environment. Understanding the interplay between Active and Latent self-efficacy and core beliefs is important since it can assist to design interventions that not only address the beliefs that are currently influencing behaviour but also those that may become influential in the future. It can also ensure a more comprehensive understanding of an agent’s belief system and how it affects their motivation, behaviour, and overall well-being.

\The connection between cultural values, emotional climate, and self-efficacy beliefs is complex and multifaceted, reflecting the intricate relationships between these factors. Specifically, cultural values can shape the way agents perceive and experience emotions, which in turn influences their self-concept and sense of agency [

59]. This dynamic interplay between cultural values, emotional climate, and self-efficacy beliefs can lead to a labyrinth of coherent/incoherent and stable/unstable relationships, ultimately impacting the capacity of culture to have an adequate sustentative influence on agency.

Here we can try to conceptualise the interplay between agency core belief systems, self-efficacy beliefs, and the cultural and emotional climate milieus within which they operate. The focus is on two key dynamics: synergy and antagonism. Synergy emerges when these elements converge to facilitate a smooth and efficacious course of action. Conversely, antagonism arises when they clash, leading to internal dissonance and hindering agency effectiveness.

3.5. Belief as a Trait and its Stability

When discussing belief within a cognitive context, we are specifically referring to self-efficacy belief. When considered as a formative trait, this can be said to have stability which is determined from the interaction between its bipolar states, i.e., between Active self-efficacy and Latent self-efficacy beliefs. These belief states contribute to agency stability and coherence within the cognitive framework. Active self-efficacy beliefs reflect agency's active, present belief in itself or others, and are concerned with immediate confidence in its abilities. When Active and Latent self-efficacy beliefs mutually interact, their relationship can vary depending on the alignment or divergence of their orientations and expressions. Conflict arises when their orientations towards action and potential are discordant. This happens when agencies exhibit a disparity between their outward expressions of confidence and their underlying, perhaps unacknowledged, beliefs about their capabilities. For instance, agencies may outwardly project confidence and competence in a task or situation (Active self-efficacy), but internally harbour doubts or insecurities (Latent self-efficacy), leading to cognitive dissonance and potentially undermining their performance or decision-making. Conversely, Active and Latent self-efficacy beliefs can find balance when they are aligned and mutually reinforcing. This occurs when agencies demonstrate coherence between their outward expressions of confidence and their internal beliefs about their capabilities. In such cases, agencies not only project confidence and competence in action but also genuinely believe in an ability to succeed, leading to enhanced performance, resilience, and adaptive behaviour. This alignment fosters a sense of congruence and authenticity, enabling agencies or their agents to navigate challenges with confidence and efficacy. This interaction between Active and Latent self-efficacy beliefs can lead to either conflict or synergy depending on the congruence or incongruence between their outward expressions and internal orientations towards action and potential.

Overall, the stability of self-efficacy belief depends on the alignment between Latent beliefs and Active self-efficacy. When self-efficacy belief is aligned with Sensate values (emphasising tangible experiences and practical outcomes), Active self-efficacy can lead to cultural synergy. Similarly, when aligned with Ideational values (focusing on abstract ideas and conceptual understanding), intellectual growth is fostered. Latent self-efficacy beliefs represent an agent’s underlying beliefs—a reservoir of potential and possibility. This may not be immediately visible but can influence behaviour when activated by specific contexts or challenges. Congruence and assurance occur when agency perceived potential (Latent self-efficacy) aligns harmoniously with their current experiences or performance (Active self-efficacy), cultivating a sense of balance and assurance. For example, agency believing strongly in its inherent capabilities (Latent) and consistently achieves intended goals (Active) experiences this alignment. Discordance and instability arise when there is discord between Latent and Active self-efficacy, leading to instability and uncertainty. Misalignment between perceived potential and current abilities may result in fluctuations in confidence, motivation, and self-assurance. Such discord can hinder effective navigation of challenges. The term cultural synergy has been used to describe either of these conditions. This refers to the seamless integration of an agent’s cognition beliefs and values with those of their cultural context.

Let us now consider affect, where interest lies in core beliefs. These play a pivotal role in shaping emotional responses and behavioural tendencies. Similar to the cognitive domain, the stability of affect core beliefs relies on the interaction between two dimensions: Active core beliefs and Latent core beliefs. Active core beliefs represent the immediate, consciously-held convictions about oneself and the world, influencing emotional reactions and responses to external stimuli. On the other hand, Latent core beliefs are the underlying, often subconscious, convictions that influence emotional experiences and responses, emerging in specific contexts or triggered by certain situations.

When Active and Latent core beliefs interact, their relationship can either be stable or unstable. Conflict arises when there is a discordance between Active and Latent core beliefs. This occurs when agents outwardly express confidence, security, or fearlessness (Active core beliefs) but internally harbour doubts, insecurities, or anxieties (Latent core beliefs). For example, someone may project confidence and bravado in social situations (Active core beliefs) while secretly feeling anxious or inadequate (Latent core beliefs). This internal conflict can lead to emotional turmoil, inconsistency in behaviour, and difficulty in managing emotions effectively [

60]. Conversely, stability in affective responses occurs when there is alignment between Active and Latent core beliefs. This alignment occurs when agents authentically embody their outward expressions of confidence, security, or optimism (Active core beliefs) with their internal beliefs and convictions (Latent core beliefs). For instance, someone who genuinely feels secure, confident, and hopeful (Latent core beliefs) tends to exhibit consistent behaviours and emotional responses that reflect these positive convictions (Active core beliefs). This alignment fosters emotional resilience, authenticity, and a sense of emotional well-being [

61].

Overall, the stability of affect core beliefs depends on the congruence between Active and Latent core beliefs. When Active core beliefs align with prevailing emotional states and experiences, agents are better equipped to manage their emotions, navigate challenges, and maintain emotional equilibrium. Conversely, conflict between Active and Latent core beliefs can lead to emotional instability, inconsistency in behaviour, and difficulties in emotional regulation. This instability can be argued as equivalent to cognitive dissonance, defined as a state of tension that occurs when a person holds two cognitions that are psychologically inconsistent with one another [

62]. However, this notion of cognitions defined to include ideas, attitudes, beliefs, behaviours as well as emotions [

63,

64], so that the definition bundles cognition with affect. Since affect and cognition are strictly speaking distinct, Cooper’s definition might be better adjusted to define dissonance as the misalignment between two psychological conditions within or across cognition and affect, indicative of when they are inconsistent with one another, resulting in psychological tension. Thus, cognitive dissonance can occur with misalignment between self-efficacy belief and cognitive values, while affective dissonance occurs with a misalignment between core beliefs and emotional climate.

In the discourse of psychology, a clear distinction between cognitive and affective dissonance aids in understanding the intricacies of human behaviour and emotional experiences. Cognitive dissonance, a concept rooted in Festinger's [

65] theory, delineates a state of mental discomfort arising from the simultaneous presence of conflicting beliefs, ideas, or values within an agent's cognitive framework [

66]. Such incongruence engenders feelings of unease, prompting agents to seek resolution to alleviate the discomfort. Key facets of cognitive dissonance encompass the recognition of inconsistency, ensuing discomfort, and the deployment of various strategies for resolution.

The core of cognitive dissonance lies in the existence of conflicting thoughts, beliefs, or behaviours, whether internally generated or externally influenced. This incongruity manifests as a state of mental tension or unease, compelling agents to strive for equilibrium by resolving the conflict. Strategies to mitigate cognitive dissonance include modifying beliefs or behaviours, rationalising actions to justify them, or evading dissonant information altogether [

65]. Illustrated through an example involving environmental beliefs and driving habits, cognitive dissonance elucidates how agents grapple with conflicting ideals and endeavour to restore cognitive harmony through behaviour change, rationalization, or information avoidance. In contrast, affective dissonance [

67], while sharing conceptual parallels with cognitive dissonance, focuses specifically on incongruities between outwardly expressed emotions and latent emotional states rooted in core beliefs. This discrepancy engenders emotional discord, impeding agents' ability to authentically navigate emotional experiences. Affective dissonance emanates from the misalignment between actively expressed emotions and underlying, often subconscious, emotional convictions [

68]. This mismatch evokes feelings of discomfort, potentially hindering agents' capacity to respond authentically to situations. Strategies to mitigate affective dissonance encompass adjusting expressed emotions to align with inner feelings, addressing the root causes of emotional incongruence, or reframing situations to facilitate emotional authenticity. Exemplified through a scenario involving social anxiety and the pressure to appear confident, affective dissonance illuminates the challenges agents encounter when reconciling outwardly projected emotions with internal emotional states. Strategies such as expressing true feelings, addressing underlying anxiety, or reframing social expectations demonstrate efforts to alleviate affective dissonance and foster emotional congruence.

Understanding affective and cognitive dissonance serves and under what conditions is might arise (

Table 1) is valuable in navigating social interactions, fostering emotional authenticity, and enhancing emotional self-regulation. By acknowledging and addressing discrepancies between expressed emotions and latent emotional states, agents can cultivate greater emotional resilience and authenticity in their interactions with others and themselves [

69].

3.6. Interaction between Beliefs and Values

Beliefs and values are interconnected [

70], whether referring to affect-based core beliefs or cognition-based self-efficacy beliefs. When both Active and Latent self-efficacy beliefs align with prevailing cultural norms, it fosters a sense of coherence and unity. In cultures characterised by balance, agent self-efficacy beliefs resonate with overarching agency values, reinforcing collective identity and ethos. Cultural coherence arises when there is alignment between agency self-efficacy and cultural (cognitive) values, while conflicts between dispositional aspirations and societal norms can lead to feelings of estrangement and cultural fragmentation. Thus, the interplay between self-efficacy beliefs and cultural values significantly impacts both personal development and cultural evolution. Stability, congruence, and cultural synergy contribute to resilient and cohesive cultural identities, while discordance may hinder progress and cohesion. Coherence indicates alignment or compatibility between self-efficacy beliefs and cultural values, defining a measure of cultural synergy that constitutes stability and functionality in the cultural system. For example, when Active self-efficacy beliefs align with Sensate values, there is coherence, as both emphasise practical outcomes and tangible results. Similarly, coherence is observed when Latent self-efficacy beliefs align with Ideational values, fostering intellectual growth and conceptual understanding. In these cases, the cultural system functions effectively as an anchor, providing a cohesive framework for agent behaviour and agency dynamics.

Beliefs and values are interconnected [

70], whether referring to affect-based core beliefs or cognition-based self-efficacy beliefs. When both Active and Latent self-efficacy beliefs align with prevailing cultural norms, it fosters a sense of coherence and unity. In cultures characterised by balance, agent self-efficacy beliefs resonate with overarching agency values, reinforcing collective identity and ethos. Cultural coherence arises when there is alignment between agency self-efficacy and cultural (cognitive) values, while conflicts between dispositional aspirations and societal norms can lead to feelings of estrangement and cultural fragmentation. Thus, the interplay between self-efficacy beliefs and cultural values significantly impacts both personal development and cultural evolution. Stability, congruence, and cultural synergy contribute to resilient and cohesive cultural identities, while discordance may hinder progress and cohesion. Coherence indicates alignment or compatibility between self-efficacy beliefs and cultural values, defining a measure of cultural synergy that constitutes stability and functionality in the cultural system. For example, when Active self-efficacy beliefs align with Sensate values, there is coherence, as both emphasise practical outcomes and tangible results. Similarly, coherence is observed when Latent self-efficacy beliefs align with Ideational values, fostering intellectual growth and conceptual understanding. In these cases, the cultural system functions effectively as an anchor, providing a cohesive framework for agent behaviour and agency dynamics.

Moving on to affect, when an agent’s Active core beliefs align with an emotional climate of Fear, it means that their beliefs about their abilities are in harmony with feelings of fear or anxiety. Here, Fear results in the need to seek isolation, be non-cooperative due to insecurity and anxiety, create a potential for aggression, and the feeling of being scared [

71]. Conversely, Security is the condition of trusting, being confident, satisfied with a situation, supporting solidarity with others, and feeling hopeful. In this scenario, agency cautious behaviour and risk avoidance are in line with a perception of their capabilities, contributing to a coherent mindset. For example, an agency with a Fear of failure may have core beliefs that align with this fear, leading to approach tasks cautiously and avoid taking risks. Conversely, when core beliefs do not align with Security, conflict arises. This lack of alignment can hinder trajectory formation or action-taking processes. For instance, if agency belief lies in an ability to succeed but is surrounded by a climate of Security and comfort, it may struggle to take risks or make bold decisions that could lead to improved viability. This conflict weakens agency ability to adapt and respond effectively to challenges, leading to incoherence.

Conflict arises when Latent core beliefs are at odds with an emotional climate of Fear. This means that agency's underlying beliefs about ability do not align with feelings of fear or anxiety. This lack of alignment may manifest as hesitation, anxiety, or self-doubt in trajectory formation processes. For example, an agency with Latent beliefs in its abilities may still feel anxious or hesitant when faced with challenges, leading to incoherence between their beliefs and emotions [

72]. Conversely, when Latent core beliefs align with an emotional climate of Security, it promotes confidence and proactive behaviour. This alignment reinforces agency resilience and adaptability, facilitating effective coping strategies in the face of adversity. For instance, if agency belief is invested in abilities and is surrounded by a climate of Security and support, they are more likely to approach challenges with confidence and resilience, leading to coherence.

This explanation is summarised in

Table 2, where incoherence refers to a lack of harmony or consistency between different elements within a system. Incoherence signifies a scenario where there is a conflict or mismatch between agency self-efficacy beliefs and the cultural values they are embedded within. This conflict undermines the coherence of the cultural system, as the values that typically serve as guiding principles for behaviour may not align with agency beliefs about their capabilities or worth. As a result, the cultural system may not effectively serve as an agency anchor leading to potential instability or dysfunction. The table illustrates how the alignment or misalignment of Active and Latent self-efficacy beliefs with Sensate and Ideational values can lead to either a synergistic or conflicting outcome, significantly impacting personal development and cultural evolution. Synergy fosters a stable and coherent culture, while conflict can challenge progress and cohesion.

To explore the table, consider that agency comprises a diverse population of agents, each embodying a unique blend of beliefs and values. These agents navigate through a complex and diverse cultural landscape and emotional climate. Within this intricate terrain, there is a framework akin to a map, facilitating comprehension of the intricate interplay between agency self-efficacy beliefs, core beliefs, cultural values, and the prevailing emotional climate.

Within the domain of cognition, agency possesses self-efficacy beliefs that are either Active or Latent or some balance between them. Active self-efficacy beliefs are consciously acknowledged and utilised by agents in their daily endeavours. They represent the conviction that one can effectively execute behaviours to achieve desired outcomes. When these beliefs harmonise with Sensate values, which prioritise tangible, sensory experiences, a seamless resonance ensues, leading to practical outcomes. This coherence fosters a cultural environment where problem-solving and trajectory formation are rooted in practicality, valuing immediate results. Conversely, when Active self-efficacy beliefs encounter Ideational values, emphasising abstract principles and ideals, discord emerges (Jin et al., 2023). This incoherence can impede conceptual development and intellectual growth, as the practical approach of agents clashes with the aspirational vision of their culture, potentially hindering collective progress.

Latent self-efficacy beliefs, lying dormant until activated, play a pivotal role in shaping agency dynamics. When these Latent beliefs conflict with Sensate values, tension arises within the cultural fabric. The agency's untapped potential is stifled by a culture that fails to nurture or recognise it, leading to a disconnect between dispositional growth and cultural expectations. In contrast, when Latent self-efficacy beliefs align with Ideational values, a fertile ground for intellectual and conceptual development is cultivated. This alignment strengthens the cultural framework, encouraging agents to explore and commit to abstract ideals and long-term goals, fostering a culture of innovation and deep understanding.

This conceptual framework, embodied by the table, serves as a guide through agency cultural and emotional climate landscape. It offers insights into how the alignment or misalignment of beliefs and values can influence cognitive processes, affective responses, and behaviours, shaping agency journeys within their cultural milieu. It is a tale of coherence and incoherence, of harmony and discord, and of the continuous quest for understanding and adaptation in the complex tapestry of human society. The table also provides a structured approach to comprehending the interplay between an agent’s self-efficacy beliefs, core beliefs, cultural values, and emotional climate. It is therefore a useful resource for both theoretical exploration and practical application in understanding agency behaviour within cultural contexts.

Furthermore, in examining agency attributes of self-efficacy beliefs and cognitive values, as well as core beliefs and emotional affect, it becomes apparent how cognitive and affect dimensions interact to shape agency dynamics. This conceptual framework delineates eight distinct scenarios, each representing potential intersections between types of belief and values for cognition and emotion. These scenarios offer a structured approach to understanding how agencies cognitively appraise information and emotionally respond to internal and external stimuli, illuminating the complex interplay between belief systems and value orientations within group contexts.

While cognition primarily deals with internal processes such as perception, reasoning, and memory, it also interacts with external attributes albeit indirectly. These external attributes are internalised, and encompass environmental stimuli, contextual factors, and social influences that impact cognitive processes and trajectory formation. For instance, sensory input from the environment and inter-agent social interactions provides context, guide attention, and shape mental representations of reality, thereby influencing cognitive processes. So, this holistic framework provides a comprehensive understanding of how cognition, emotion, action, and coherence intersect to shape agent behaviour and outcomes within agency dynamics, offering valuable insights for both analysis and application.

In discussing Active and Latent beliefs within the affective context, we refer to core beliefs, and within cognition, we refer to self-efficacy beliefs. However, it's important to recognise that both affect and cognition play interactive roles in shaping and interpreting beliefs. Affect influences how agents emotionally respond to and prioritise certain cultural values, while cognition determines how agents interpret and make sense of those values. Synergy between Active and Latent beliefs with Sensate and Ideational value states depends on their alignment. When these beliefs resonate with respective values, coherence is fostered, leading to a harmonious mindset and behaviour. For instance, if an agent holds Latent beliefs that prioritises tangible achievements and empirical evidence, these beliefs may resonate well with Sensate values, fostering coherence. Conversely, if beliefs conflict with Sensate values, discordance may lead to cognitive dissonance or internal conflict, potentially causing confusion or ambivalence. Similarly, synergy between Active and Latent beliefs with Ideational values depends on alignment. When beliefs resonate with Ideational values, a coherent cognitive framework is established. However, contradictions may lead to cognitive dissonance or tension, causing internal conflict or uncertainty. Thus, the synergy between Active and Latent self-efficacy beliefs with Sensate and Ideational value states depends on their alignment and congruence, influencing agency behaviour and outcomes.

Agency culture, consisting of shared beliefs, values, norms, practices, and behaviours, is shaped by the interaction between cognitive values and self-efficacy beliefs. In a coherent culture, values and beliefs are synchronized, fostering unity and purpose. Consistency creates a reinforcement between them, leading to stability over time. Conversely, incoherent cultures experience disconnects between values and beliefs, leading to confusion and instability. Partly coherent cultures exhibit a blend of alignment and misalignment, demonstrating adaptability but posing challenges in maintaining balance.

Disposition, encompassing both cognitive and affective personality traits, serves as a foundational element shaping agency behavioural patterns and character within various contexts. As Yolles and Rautakivi [

28] note, cognitive disposition influences agency intellectual autonomy, figurative mastery, and operative hierarchy, while affective disposition encompasses traits such as stimulation, ambition, and dominance. These dispositional traits provide a lens through which agency perceives and interacts with its environment, guiding its responses to internal and external stimuli.

In understanding the function of disposition, it becomes evident that these inherent qualities play an important role in guiding agency behaviour and trajectory formation processes. Cognitive disposition, for instance, influences agency orientations with respect to individualism, hierarchy, and social patterning, thereby shaping its organisational structure, leadership style, and communication practices. Similarly, affective disposition influences agency emotional responses, motivational drives, and interpersonal dynamics, impacting its overall emotional climate and social interactions. However, despite the significance of disposition in shaping agency character, there are instances where it may be temporarily disregarded or overridden, particularly in the context of interactions with sociocultural traits. This temporary disregard can be attributed to several factors.

Firstly, the influence of sociocultural factors on behaviour can sometimes outweigh disposition. Cultural beliefs, cognitive values and norms with emotional climates within a given context may exert a strong influence on agency behaviour, leading it to prioritise collective interests or societal expectations over agent predispositions. Social organisation (with bipolar value states of Gesellschaft and Gemeinschaft) and cognitive style (with value states Dramatising and Patterning) will also be important to indicate functional coherence.

Secondly, agencies may adapt their behaviours and attitudes to align with the prevailing sociocultural context, demonstrating a degree of flexibility and responsiveness to external demands. This adaptation reflects the agency's ability to navigate diverse environments and adjust its strategies to fit the cultural nuances and expectations of different contexts. Finally, goal alignment may also influence the temporary disregard of disposition. In pursuit of specific objectives or outcomes, agencies may prioritise actions or attitudes that align with the desired goals, even if they diverge from their inherent disposition. This goal-oriented behaviour underscores agency strategic orientation and its pragmatic willingness to adjust its approach to achieve desired results.

Thus, while disposition serves as a fundamental aspect of agency character, its influence may be subject to temporary disregard or modification in response to the complexities of the sociocultural environment. This adaptive capacity highlights the dynamic nature of agency behaviour and the importance of considering both dispositional traits and contextual factors in understanding organisational dynamics and trajectory formation processes.

3.7. Cognitive and Affective Trait Dimensions

Exploring the cognitive and affective dimensions of agency sheds light on how agents navigate their environments and make decisions. Cognitive disposition encompasses how they process information, make judgments, and approach tasks, while affective disposition involves their emotional attitudes and responses. Together, these dimensions shape agents' behaviours, motivations, and interactions with others.

Within cognitive disposition, agents may exhibit tendencies towards collectivism, prioritising group goals and social harmony, or towards intellectual autonomy, valuing agent achievement and self-reliance. This cognitive orientation intertwines with concepts such as figurative mastery, where agents seek external control and accomplishment, and affective autonomy, where they strive for balance and peaceful coexistence. Additionally, cognitive disposition can be influenced by operative hierarchy, leading agents to adhere to social norms and structures or advocate for equality and justice.

In the domain of affective disposition, agents may display emotional attitudes of containment, emphasizing self-control and delayed gratification, or stimulation, seeking emotional arousal that can vary in polarity. Figurative motivation activation further influences their behaviour, with some driven by ambition and others by a desire for protection and security. Operative emotion management plays a significant role in regulating agents' emotional responses, with some seeking dominance and influence over others while others value submission and respect for authority. Affect cultural aspects, such as emotional climate, contribute to creating either secure and trusting environments or insecure and uncooperative ones.

Exploring both the tangible and intangible dimensions of cognitive and affective traits offers profound insights into human behaviour and decision-making processes.

Table 3 and

Table 4 serve as a comprehensive guide, delineating the traits along with their inherent characteristics. This facilitates an improved appreciation of how these traits impact agency stability, responsiveness to environmental stimuli, and interactions within social contexts.

The relationships between different traits play a significant role in shaping the overall character of the agency. These relationships can be both complementary and conflicting, influencing how traits interact and manifest in various contexts. Complementary relationships occur when traits reinforce or support each other, leading to a cohesive and harmonious agency character. For example, if agency exhibits traits of intellectual autonomy, such as prioritising independent thought and agent achievement, and also demonstrates traits of Active self-efficacy, believing in achieving tangible goals through action and initiative, these traits may complement each other. Agency ability to think independently may align with its proactive approach to goal achievement, resulting in a character characterised by self-reliance and initiative. Conversely, conflicting relationships between traits can lead to tensions and inconsistencies within the agency character. For instance, if agency displays traits of dominance, seeking control and influence over others, and also exhibits traits of empathy, understanding, and acceptance of others' perspectives, these trait value states may conflict with each other. Agency desire for control may also clash with its capacity for empathy, leading to internal conflicts and challenges in interpersonal interactions.

The dynamic interplay between the polar cognitive values states that traits can adopt can collectively give rise to emergent properties that shape the overall agency character. These emergent properties arise from the complex interactions and synergies between different trait values states, resulting in unique patterns of behaviour, trajectory formation processes, and responses to the environment. For example, agency characterised by a combination of dominance and ambition may exhibit emergent properties such as assertiveness, goal-oriented behaviour, and a drive for success. Overall, the relationships between different traits are integral to understanding the overall character of the agency. Whether complementary or conflicting, these relationships contribute to the complexity and richness of agency behaviour, influencing its interactions with the environment and shaping its identity and functioning over time.

Understanding the stability of agency traits involves examining the interplay between tangible and intangible polar value states. This interplay is important since it determines whether traits are synergistic, contributing to stability, or antagonistic, leading to instability. For instance, cognitive disposition traits such as cognitive embeddedness are influenced by the balance between tangible values like intellectual autonomy and intangible values like social embeddedness. Stability in this domain is achieved when there is a harmonious balance between valuing independent thought and personal achievement (tangible) and prioritizing social harmony and cooperation (intangible). When these value states are aligned, they foster trait stability, nurturing personal growth and societal cohesion [

73].

Within the cognitive cultural framework, both cognitive values and self-efficacy beliefs significantly influence the formation of a stable cultural identity. Cognitive values, categorised as Sensate (prioritising tangible material possessions and sensory experiences) or Ideational (focusing on knowledge and intangible attributes), define an agent's value orientation. Self-efficacy beliefs, further distinguished as Active (representing current capabilities) or Latent (indicating potential), contribute to the perception of agency within a cultural context. Ultimately, a stable cultural identity is achieved when there is congruence between these cognitive values (encompassing both tangible and intangible aspects) and an agent's sense of agency. Affective cultural traits, including emotional climate and core beliefs, also rely on the interaction between tangible and intangible polar value states. Stability in affective disposition ensues when an agency’s emotional attitudes and responses align with both tangible and intangible values within its social and cultural context. Trait stability is deeply rooted in the synergy between tangible and intangible polar value states within each trait domain. When these states are congruent, they enhance stability by promoting consistent behaviour, attitudes, and beliefs. Conversely, a mismatch between tangible and intangible aspects can lead to instability, cognitive dissonance, and emotional turmoil within an agency. Thus, a thorough understanding of the interplay between these value states is essential for predicting trait stability in various areas of agency operation.