Submitted:

10 September 2024

Posted:

12 September 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Isolation of Strain, Extraction of DNAg and Genome Sequencing

2.2. Genome Assembly, Annotation and Analysis Functional

2.3. Comparative Genome Analysis, Confirmation Molecular and Pan Genome

2.4. Prediction of Hydrocarbon-Degrading Genes and Enzymes

2.5. In Silico Protein-Protein Interaction and Subcellular Localization of Hydrocarbon-Degrading Proteins

2.6. Molecular Modeling, Model Validation, and Molecular Docking

3. Results

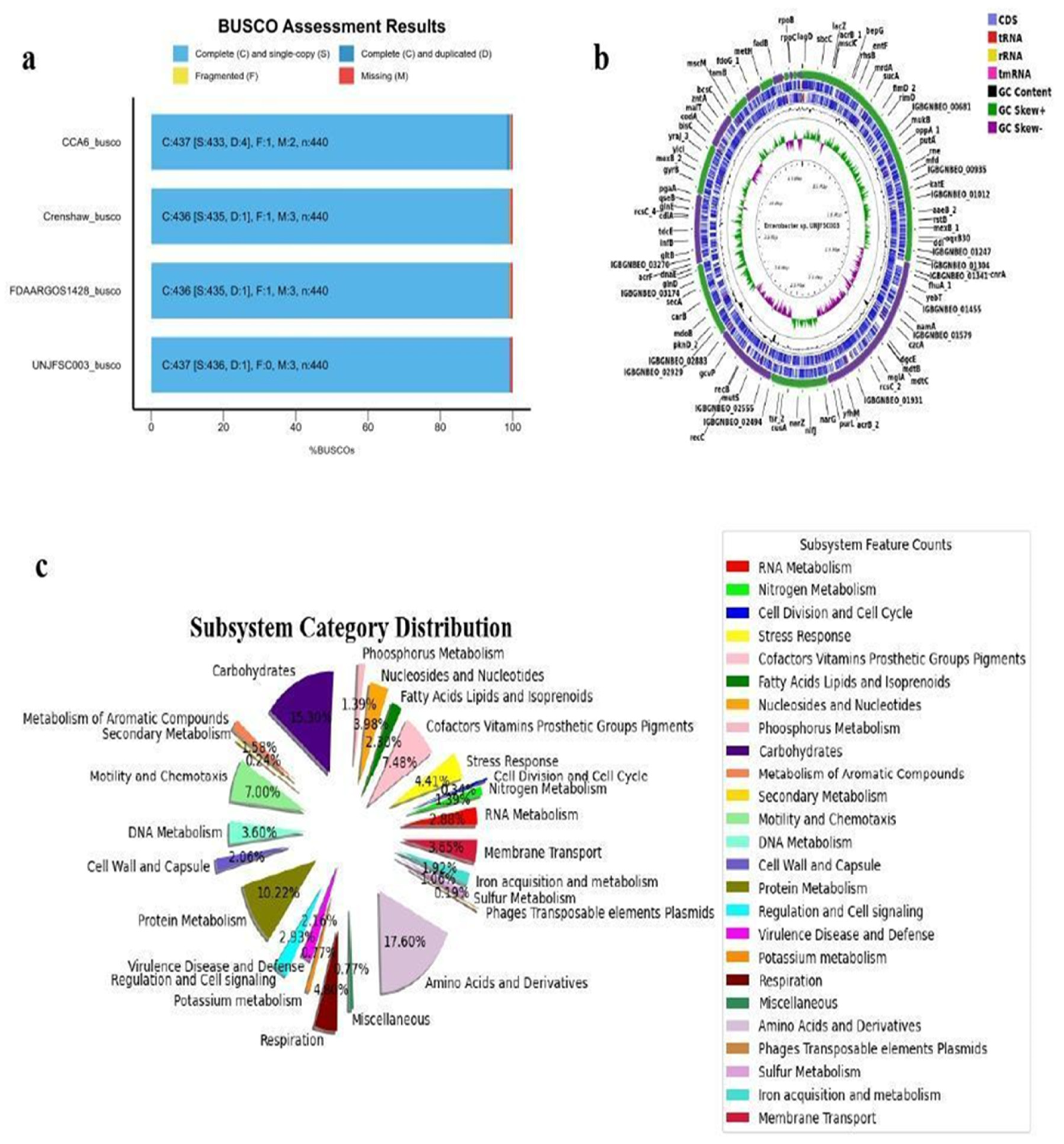

3.1. Isolation of the Strain and Genome Characteristics of Enterobacter sp. UNJFSC 003

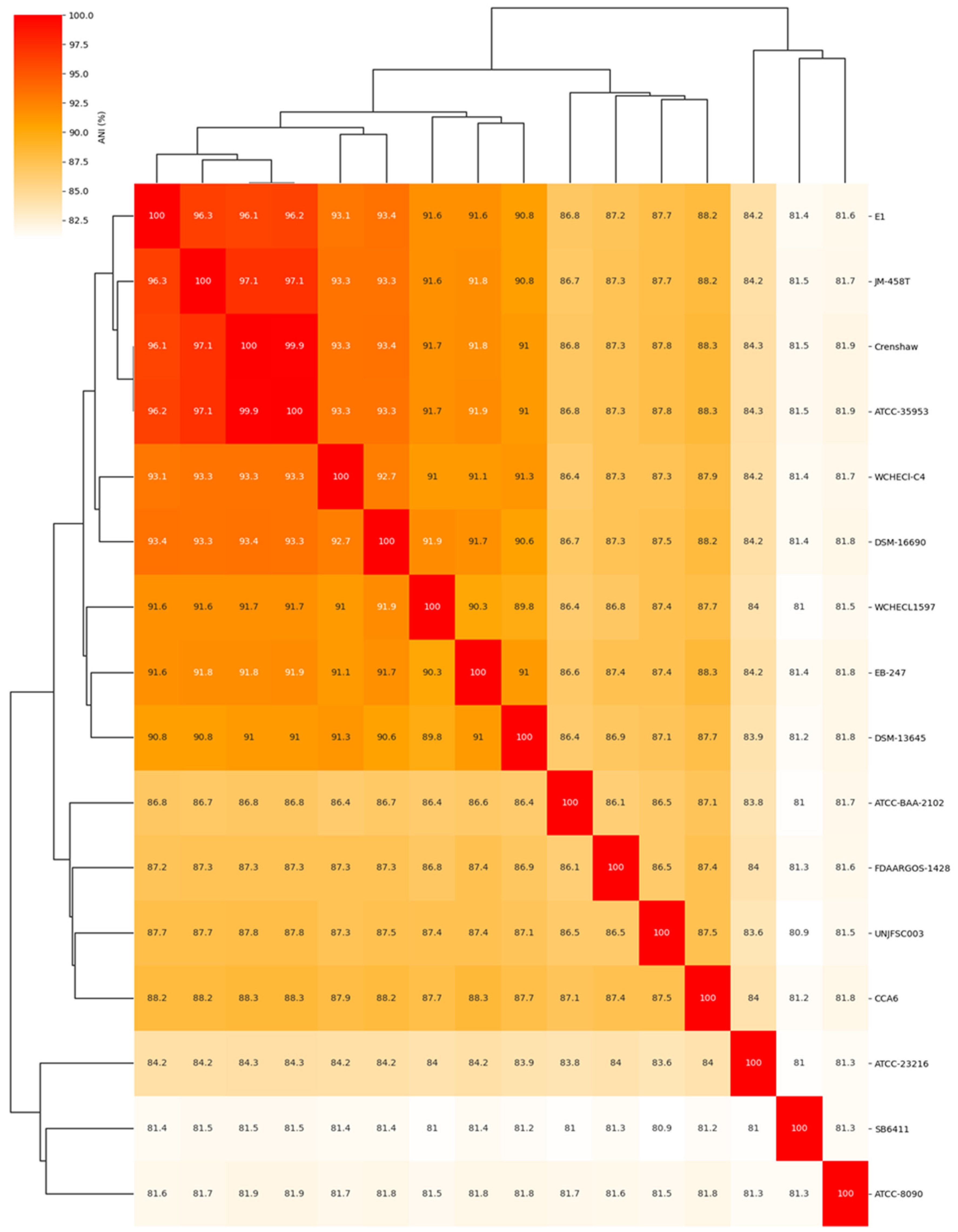

3.2. Comparative Analysis of the Complete Genome of Enterobacter sp. UNJFSC 003

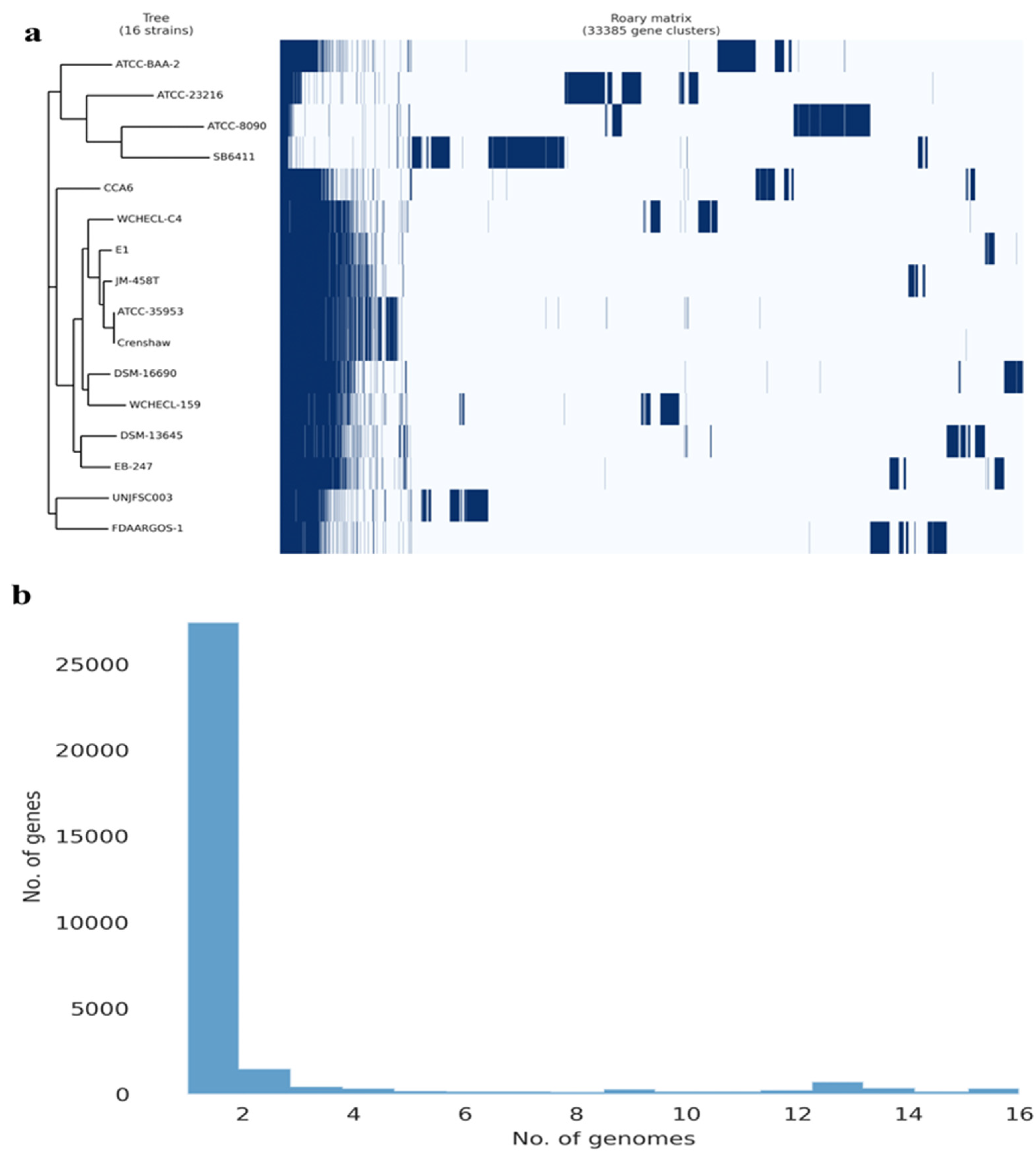

3.3. Analysis of the Pangenome of Enterobacter sp. UNJFSC 003

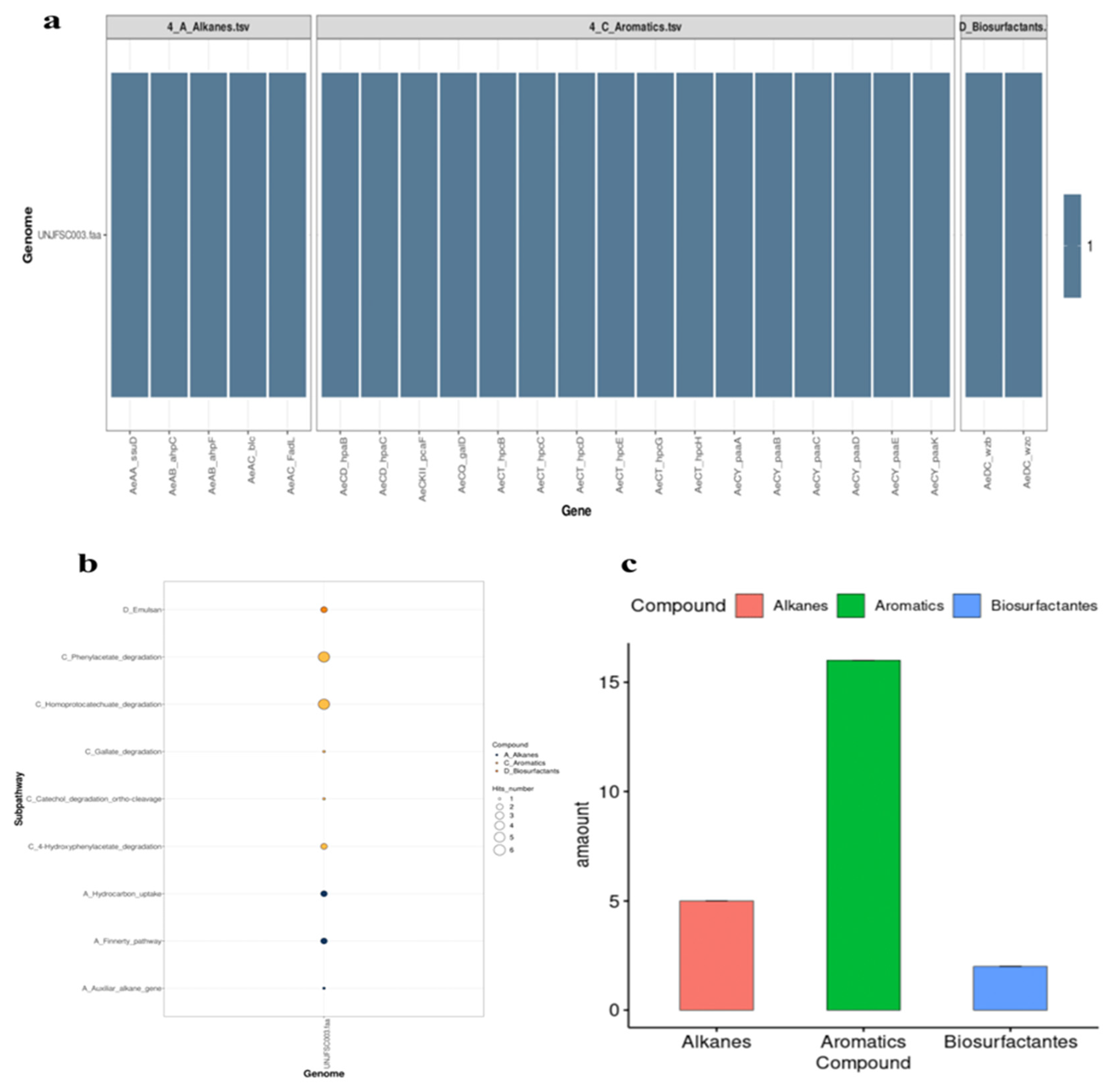

3.4. The Strain UNJFSC 003 Harbors Genes Encoding Enzymes for the Bioremediation of Hydrocarbons

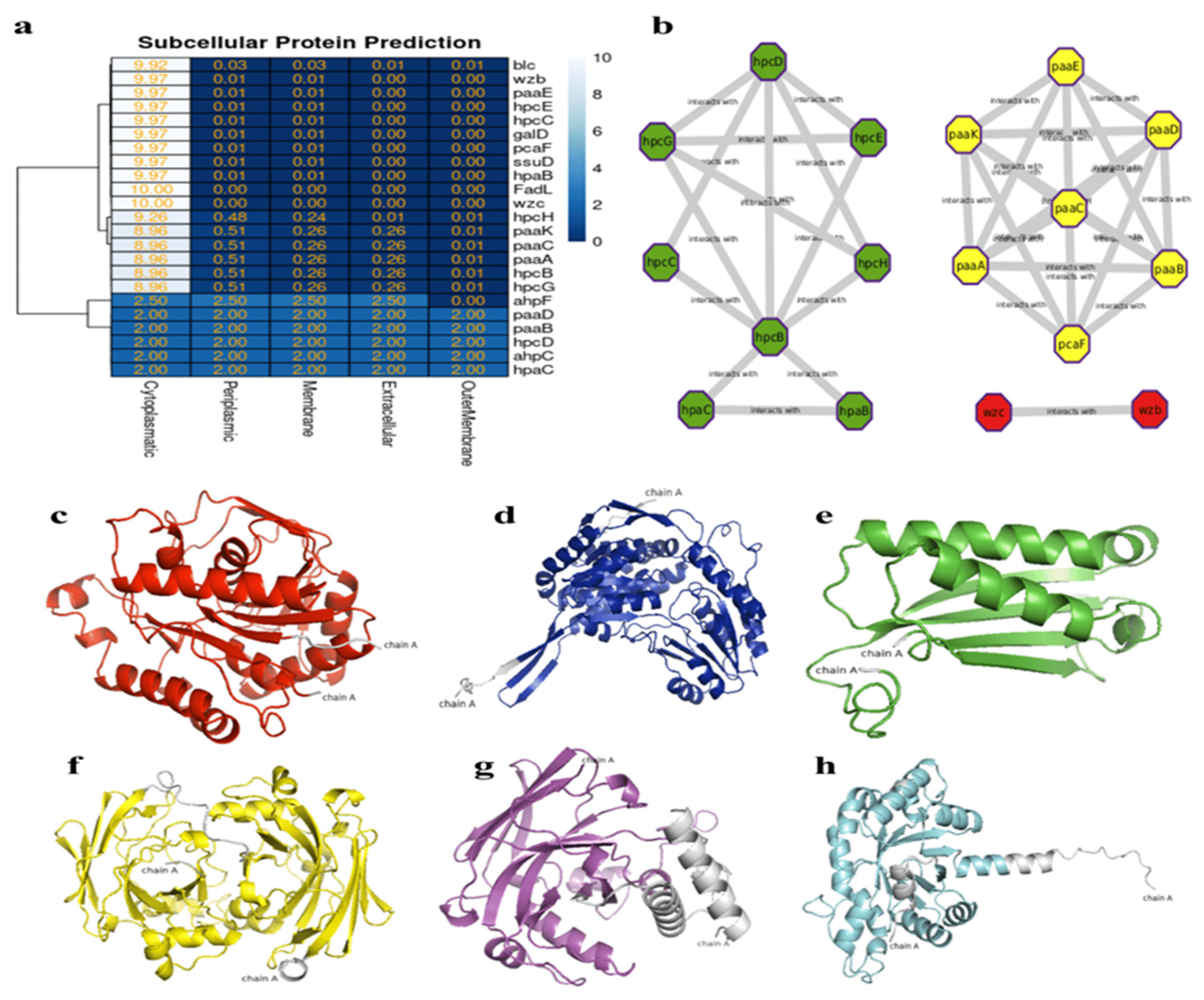

3.5. In Silico Interaction Protein-Protein and Heat-Map of Proteins Involved in Bioremediation

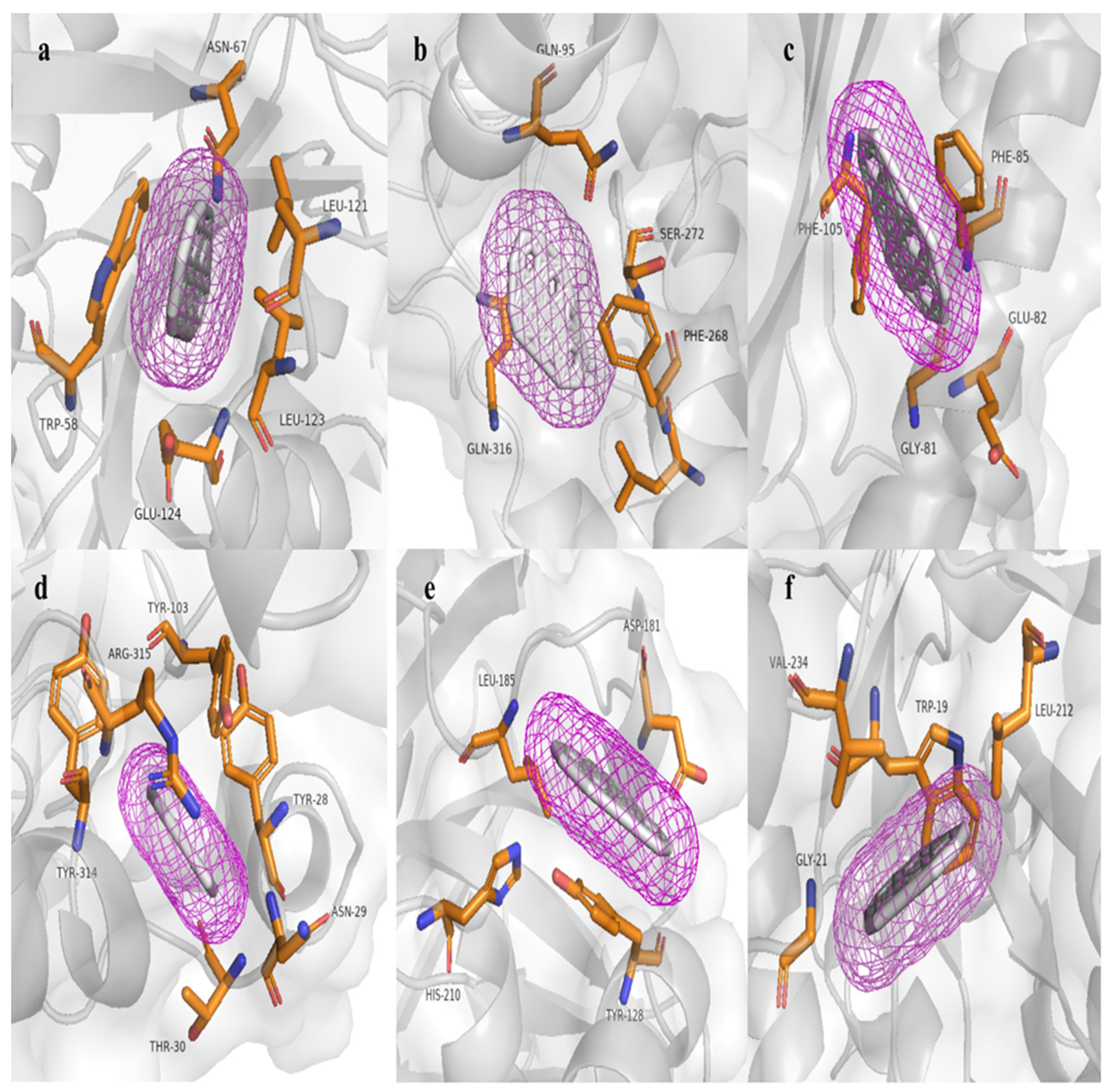

3.6. Molecular Modelling and Docking Analysis

| Modelling Server | Protein Modelling | Errat | Error/Warning/Plass | R. Plot% | Z-score | SignalP | Num. aa | pI | Mol Weight | GRAVY |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| trRosseta | hpcB | 97.87 | 2/4/3 | 95.4% | -11.36 | No | 283 | 5.72 | 31721.04 | -0.228 |

| trRosseta | hpcC | 93.38 | 2/4/3 | 94.0% | -11.41 | No | 488 | 6.25 | 53130.86 | -0.112 |

| trRosseta | hpcD | 83.49 | 1/3/4 | 94.6% | -4.79 | No | 126 | 5.82 | 14336.35 | -0.202 |

| trRosseta | hpcE | 92.44 | 3/2/4 | 90.6% | -9.65 | No | 425 | 5.03 | 46227.37 | -0.146 |

| trRosseta | hpcG | 93.44 | 0/4/4 | 91.8% | -6.87 | No | 267 | 5.69 | 29481.68 | -0.081 |

| trRosseta | hpcH | 96.85 | 0/4/5 | 94.7% | -8.81 | No | 265 | 5.73 | 28175.33 | 0.107 |

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Singh, K. & Chandra, S. (2014). Treatment of petroleum hydrocarbon polluted environment through bioremediation: a review. Pak J Biol Sci. 1:17. 1-8. [CrossRef]

- Tormoehlen, L.M., Tekulve, K.J. & Ñañagas, K.A. (2014). Hydrocarbon toxicityÑ A review. Clinical Toxiclogy. 52, 479-489.

- Volkman, J.K. (1998). Hydrocarbons . In: Geochemistry. Encyclopedia of Earth Science. Springer, Dordrecht. [CrossRef]

- Das, T. & Dash. H.R. (2014). Microbial Bioremediation: A Potential Tool for Restoraton of Contaminated Areas. Microbial Biodegradation and Biorremediation. Pages 1-21. [CrossRef]

- Ayilara, M.S. & Babalola, O.O. (2023). Bioremediation of environmental wastes: the role of microorganisms. Front. Agron., Plant-Soil Interactions. Vol5. [CrossRef]

- Castillo-Rogel, R.T., More-Calero, F.J., La-Torre, M.C., Fernandez-Ponce, J.N. & Mialhe-Matonnier, E.L. (2020). Aislamiento de bacterias con potencial biorremediador y analisis de comunidades bacterianas de zona impactada por derrame de petroleo encondorcanqui- Amazonas - Peru. Rev. invest. Altoand. Vol.22 no.3. [CrossRef]

- Emenike, C.U., Agamuthu, P., Fauziah, S.H. et al. Enhanced Bioremediation of Metal-Contaminated Soil by Consortia of Proteobacteria. Water Air Soil Pollut 234, 731 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Nyoyoko, V.F. (2022). Chapter 13 - Proteobacteria response to heavy metal pollution stress and their bioremediation potential. Cost Effective Technologies for Solid Waste and Wastewater Treatment. Pages 147-159. [CrossRef]

- Thacharodi, A., Hassan, S., Singh, T., Mandal, R., Chinnadurai, J., Khan, H.A., Hussain, M.A., Brindhadevi, K. & Pugazhendhi, A. (2023). Biormediation of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons: Anupdated microbiological review. Chemosphere. Vol328. 138498. [CrossRef]

- Andrews S. 2010. FastQC: una herramienta de control de calidad para datos de secuencias de alto rendimiento . Disponible en: http://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc/.

- Bolger AM, Lohse M, Usadel B. 2014. Trimmomatic: un recortador flexible para datos de secuencias de Illumina. Bioinformática 30:2114–2120.

- Chen. 2023. Ultrafast one-pass FASTQ data preprocessing, quality control, and deduplication using fastp. iMeta 2: e107. [CrossRef]

- Wick, R.R., Judd, L.M., Gorrie, C.L., & Holt, K.E. (2017). Unicycler: Resolving bacterial genome assemblies from short and long sequencing reads. PLOS Computational Biology, 13(6), e1005595. [CrossRef]

- Gurevich, A., Saveliev, V., Vyahhi, N., & Tesler, G. (2013). QUAST: quality assessment tool for genome assemblies. Bioinformatics, 29(8), 1072–1075. [CrossRef]

- Simao FA, Waterhouse RM, Ioannidis P, Kriventseva EV, Zdobnov EM. 2015. BUSCO online supplementary information: assessing genome assembly and annotation completeness with single-copy orthologs. Bioinformatics 31:3210–3212.

- Rodriguez-R, L. M., Gunturu, S., Harvey, W. T., Rosselló-Mora, R., Tiedje, J. M., Cole, J. R., & Konstantinidis, K. T. (2018). The Microbial Genomes Atlas (MiGA) webserver: taxonomic and gene diversity analysis of Archaea and Bacteria at the whole genome level. Nucleic Acids Research, 46(W1), W282–W288. [CrossRef]

- Seemann, T. (2014). Prokka: rapid prokaryotic genome annotation. Bioinformatics, 30(14), 2068–2069. [CrossRef]

- Aziz., R.K., Bartels, D., Best, A.A., DeJongh, M., Disz, T., Edwards, R.A., Formsma, K., Gerdes, S., Glass, E.M., Kubal, M., Meyer, F., Olsen, G.J., Olson, R., Osterman, A.L., Overbeek, R.A., McNeil, L.K., Paarmann, D., Paczian, T., Parrello, B., Pusch, G.D., Reich, C., Stevens, R., Vassieva, O., Vonstein, V., Wilke, A. & Zagnitko, O. (2008). The RAST Server: Rapid Annotations using Subsystems Technology. , 9(1), 75–0. [CrossRef]

- Grant, J.R., Enns, E., Marinier, E., Manda, A., Herman, E.K., Chen, C. Graham, M.,Domselaar, G.V., Stothard, P. & Notes, A. (2023). Proksee: in-depth characterization and visualization of bacterial genomes. Nucleic Acids Research. Vol 51. W484-W492. [CrossRef]

- Hunter, J.D. "Matplotlib: A 2D Graphics Environment", Computing in Science & Engineering, vol. 9, no. 3, pp. 90-95, 2007.

- Cantalapiedra, C.P., Hernandez-Plaza, A., Letunic, I., Bork, P., Jaime Huerta-Cepas. 2021. eggNOG-mapper v2: functional annotation, orthology assignments, and domain prediction at the metagenomic scale. Molecular Biology and Evolution, msab293. [CrossRef]

- Kanehisa, M. & Goto, S. (2000). KEGG: Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes, Nucleic Acids Research, Volume 28, Issue 1, 1 January 2000, Pages 27–30. [CrossRef]

- Kanehisa, M., Sato, Y. & Morishima, K. (2016) .BlastKOALA and GhostKOALA: KEGG Tools for Functional Characterization of Genome and Metagenome Sequences. Journal of Molecular Biology, Vol-428, 726-731. [CrossRef]

- Jain C, Rodriguez-R LM, Phillippy AM, Konstantinidis KT, Aluru S. High throughput ANI analysis of 90K prokaryotic genomes reveals clear species boundaries. Nat Commun. 2018;9:5114. [CrossRef]

- Shimoyama Y. ANIclustermap: a tool for drawing ANI clustermap between all-vs-all microbial genomes. 2022. https://github.com/moshi4/ANIclustermap.

- Page, A.J., Cummins, C.A., Hunt, M., Wong, V.K., Reuter, S., Holden-Matth T.G., Fookes, M., Falush, D., Keane, J.A. & Parkhill, J. (2015). Roary: rapid large-scale prokaryote pan genome analysis. Bioinformatics, 31(22), 3691–3693. [CrossRef]

- Rojas-Vargas, J., Castelán-Sánchez, H.G., Pardo-López, L. (2023) HADEG: A curated hydrocarbon aerobic degradation enzymes and genes database. Computational Biology and Chemistry. [CrossRef]

- Lechner, M., Findeisz, S., Steiner, L., Marz, M., Stadler, P. F., & Prohaska, S. J. (2011). Proteinortho: detection of (co-) orthologs in large-scale analysis. BMC bioinformatics, 12(1), 124.

- Szklarczyk, D., Kirsch, R., Koutrouli, M., Nastou, K., Mehryary, Hachilif, R., Gable, A.L., Fang, T., Doncheva, N.T., Pyysalo, S., Bork, P., Jensen, L.J. & Mering, C.v. (2023). The STRING database in 2023: protein–protein association networks and functional enrichment analyses for any sequenced genome of interest. Nucleic Acids Research, 51(W), W638-W646. [CrossRef]

- Otasek D, Morris JH, Bouças J, Pico AR, Demchak B. Cytoscape Automation: empowering workflow-based network analysis. Genome Biol. 2019 Sep 2;20(1):185. PMID: 31477170; PMCID: PMC6717989. [CrossRef]

- Yu, N.Y., Wagner, J.R., Laird, M.R., Melli, G., Rey, S., Lo, R. & Brinkman, F.S.L. (2010). PSORTb 3.0: improved protein subcellular localization prediction with refined localization subcategories and predictive capabilities for all prokaryotes. Bioinformatics, 26(13), 1608–1615. [CrossRef]

- Kolder R. (2018). pheatmap: Pretty Heatmaps. R package version 4.4.0.

- R Core Team (2024). _R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing_. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. <https://www.R-project.org/>.

- Blum, M., Chang, H.Y., Chuguransky, S., Grego, T., Kandasaamy, S., Mitchell, A. Nuka, G., Paysan-Lafosse, T., Qureshi, M., Raj, S., Richardson, L., Salazar, G.A., Williams, L., Bork, P., Bridge, A., Gough, J., Haft, D.H., Letunic, I., Marchler-Bauer, A., Mi, H., Natale, D.A., Necci, M., Orengo, C.A., Pandurangan, A.P., Rivoire, C., Sigrist, C.J.A., Sillitoe, I., Thanki, N., Thomas, P.D., Tosatto, S.C.E., Wu, C.H., Bateman, A. & Finn, R.D. (2020). The InterPro protein families and domains database: 20 years on. Nucleic Acids Research, (), gkaa977–. [CrossRef]

- Du Z, Su H, Wang W, Ye L, Wei H, Peng Z, Anishchenko I, Baker D, Yang J. The trRosetta server for fast and accurate protein structure prediction. Nat Protoc. 2021 Dec;16(12):5634-5651. [CrossRef]

- de Beer TA, Berka K, Thornton JM, Laskowski RA. PDBsum additions. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014 Jan;42(Database issue):D292-6. [CrossRef]

- Colovos, C. & Todd O.Y. (1993). Verification of protein structures: Patterns of nonbonded atomic interactions. , 2(9), 1511–1519. [CrossRef]

- Wiederstein, M., Sippl, M. J. (2007). ProSA-web: interactive web service for the recognition of errors in three-dimensional structures of proteins. Nucleic Acids Research, 35(Web Server), W407–W410. [CrossRef]

- Teufel, F., Armenteros, A.J.J., Johansen, A.R. et al. SignalP 6.0 predicts all five types of signal peptides using protein language models. Nat Biotechnol 40, 1023–1025 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Gasteiger E., Hoogland C., Gattiker A., Duvaud S., Wilkins M.R., Appel R.D., Bairoch A.; Protein Identification and Analysis Tools on the Expasy Server; (In) John M. Walker (ed): The Proteomics Protocols Handbook, Humana Press (2005). pp. 571-607.

- Trott, O., A. J. Olson, AutoDock Vina: improving the speed and accuracy of docking with a new scoring function, efficient optimization and multithreading, Journal of Computational Chemistry 31 (2010) 455-461.

- Morris, G. M., Huey, R., Lindstrom, W., Sanner, M. F., Belew, R. K., Goodsell, D. S. and Olson, A. J. (2009) Autodock4 and AutoDockTools4: automated docking with selective receptor flexiblity. J. Computational Chemistry 2009, 16: 2785-91.

- Hanwell, M.D., Curtis, D.E., Lonie, D.C. et al. Avogadro: an advanced semantic chemical editor, visualization, and analysis platform. J Cheminform 4, 17 (2012). [CrossRef]

- Schrödinger, L. & DeLano, W. (2024). PyMOL. Retrieved from http://www.pymol.org/pymol.

- Farmer JJ, Davis BR, Hickman-Brenner FW, McWhorter A, Huntley-Carter GP, Asbury MA, Riddle C, Wathen-Grady HG, Elias C, Fanning GR. 1985. Biochemical identification of new species and biogroups of Enterobacteriaceae isolated from clinical specimens. J Clin Microbiol 21:. [CrossRef]

- Rosselló-Móra R, Amann R. 2015. Past and future species definitions for bacteria and archaea. Syst Appl Microbiol 38:209–216.

- Anzuay, M.S., Prenollio, A., Ludueña, L.M. et al. Enterobacter sp. J49: A Native Plant Growth-Promoting Bacteria as Alternative to the Application of Chemical Fertilizers on Peanut and Maize Crops. Curr Microbiol 80, 85 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Tovar C, Sánchez Infantas E, Teixeira Roth V (2018) Plant community dynamics of lomas fog oasis of Central Peru after the extreme precipitation caused by the 1997-98 El Niño event. PLoS ONE 13(1): e0190572. [CrossRef]

- Muneeswari, R., Iyappan, S., Swathi, KV., Sudheesh, KP., Rajesh, T., Sekaran G. & Ramani, K. (2021). Genomic characterization of Enterobacter xiangfangensis STP-3: Application to real time petroleum oil sludge bioremediation. Microbiological Research, ScienceDirect. Vol-253. [CrossRef]

- Ya-Ming C., Li X. & Ling-Yun J. (2011). Analysis of PCBs degradation abilities of biphenyl dioxygenase derived from Enterobacter sp. LY402 by molecular simulation. , 29(1), 90–98. [CrossRef]

- Hošková, M., Ježdík, R., Schreiberová, O., Chudoba, J., Šír, M., Čejková, A., Masák, J., Jirků, V. & Řezanka, T. (2015). Structural and physiochemical characterization of rhamnolipids produced by Acinetobacter calcoaceticus, Enterobacter asburiae and Pseudomonas aeruginosa in single strain and mixed cultures. Journal of Biotechnology, 193(), 45–51. [CrossRef]

- Yousaf, S., Afzal, M., Reichenauer, T. G., Brady, C. L., & Sessitsch, A. (2011). Hydrocarbon degradation, plant colonization and gene expression of alkane degradation genes by endophytic Enterobacter ludwigii strains. Environmental Pollution, 159(10), 2675–2683. [CrossRef]

- Broderick, J.B. (1999). Catechol dioxygenases. Essays In Biochemestry, Vol. 34. [CrossRef]

- Baburam, C., Feto, N.A. Mining of two novel aldehyde dehydrogenases (DHY-SC-VUT5 and DHY-G-VUT7) from metagenome of hydrocarbon contaminated soils. BMC Biotechnol 21, 18 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Gangola, S., Bhandari, G., Joshi, S., Sharma, A., Simsek, H. & Bhatt, P. (2023). Esterase and ALDH dehydrogenase-based pesticide degradation by Bacillus brevis 1B from a contaminated environment. Environmental Research, ScienceDirect. Vol-231. [CrossRef]

- Winsor GL, Griffiths EJ, Lo R, Dhillon BK, Shay JA, Brinkman FS (2016). Enhanced annotations and features for comparing thousands of Pseudomonas genomes in the Pseudomonas genome database. Nucleic Acids Res. (2016). [CrossRef]

- Roper, D.I., Cooper, R.A. (1990). Purification, some properties and nucleotide sequence of 5-carboxymethyl-2-hydroxymuconate isomerase of Escherichia coli C. Febs Letters. Vol 266, Pages: 63-66. [CrossRef]

- Izumi, A., Rea, D., Adachi, T., Unzai, S., Sam-Yong, P., Roper, D.I. and Tame, J.R.H. (2007). Structure and Mechanism of HpcG, a Hydratase in the Homoprotocatechuate Degradation Pathway of Escherichia coli. JMB. Vol 370. Pages: 899-911. [CrossRef]

- Blum, M., Chang, H.Y., Chuguransky, S., Grego, T., Kandasaamy, S., Mitchel, A., Nuka, G., Lafosse, T.P., Qureshi, M., Raj, S., Richardson, L., Salazar, G.A., Williams, L., Bork, P., Bridge, A., Gough, J., Haft, D.H., Letunic, I., Marchler-Bauer, A., Mi, H., Natale, D.A., Necci, M., Orengo, C.A., Pandurangan, A., Rivoire, C., Sigrist, C.J.A., Silitoe, I., Thanki, N., Thomas, P.D., Tosatto, S.C.E., Wu, C.H., Bateman, A. & Finn, R.D. (2021). The InterPro protein families and domains database: 20 years on. Nucleic Acids Res. Vol, 49. Pages D344-D354. [CrossRef]

- Thompson, C.C., Chimetto, L., Edwards, R.A., Swings, J., Stackebrandt, E. & Thompson, F.L. (2013). Microbial genomic taxonomy. BMC Genomics, 14(1), 913–. [CrossRef]

- Wu, W., Feng, Y. & Zong, Z. (2018). Characterization of a strain representing a new Enterobacter species, Enterobacter chengduensis sp. nov.. Antonie van Leeuwenhoek, (), –. [CrossRef]

- Ho, N.R., Kondiah, K., De Maayer, P. & Putonti, C. (2018). Complete Genome Sequence of Enterobacter xiangfangensis Pb204, a South African Strain Capable of Synthesizing Gold Nanoparticles. Microbiology Resource Announcements, 7(22), –. [CrossRef]

- Schroeter, M,N., Gazali, S.J., Parthasarathy, A., Wadsworth, C.B. & Rezende, R. (2021). Isolation, Whole-Genome Sequencing, and Annotation of Three Unclassified Antibiotic-Producing Bacteria, Enterobacter sp. Strain RIT 637, Pseudomonas sp. Strain RIT 778, and Deinococcus sp. Strain RIT 780. ASM Journals, Microbiology Resource Announcements. Vol.10.

- Indugu, N., Sharma, L., Jackson, C.R. & Singh P. (2020). Whole-Genome Sequence Analysis of Multidrug-Resistant Enterobacter hormaechei Isolated from Imported Retail Shrimp. Microbiol Resour Announc. Vol.9. [CrossRef]

- Szczerba, H., Komon-Janczara, E., Krawczyk, M., Dudziak, K., Nowak, A., Kuzdraliński, A., Waśko, A. & Targónski, Z. (2020). Genome analysis of a wild rumen bacterium Enterobacter aerogenes LU2 - a novel bio-based succinic acid producer. Sci Rep 10, 1986 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Jahan, R., Bodratti, A.M., Tsianou, M. & Alexandridis, P. (2020). Biosurfactants, natural alternatives to synthetic surfactants: Physicochemical properties and applications. Advances in Colloid and Interface Science. Vol-275. 102061. [CrossRef]

- Peng, X., Zheng, Q., Liu, L., He, Y., Li, T. & Jia, X. Efficient biodegradation of tetrabromobisphenol A by the novel strain Enterobacter sp. T2 with good environmental adaptation: Kinetics, pathways and genomic characteristics. Journal of Hazardous Materials, ScienceDirect. Vol-429. [CrossRef]

- El-Beltagi, H.S., Halema, A., Almutairi, Z.M., Almutairi, H.H., Elarabi, N., Abdelhadi, A.A., Henawy, A.R. & Abdelhaleem, H.A.R. 2024. Draft genome analysis for Enterobacter kobei, a promising lead bioremediation bacterium. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnology. Vol-11. [CrossRef]

- Camacho, J., Mesen-Porras, E., Rojas-Gatjens, D., Perez-Pantoja, D., Puente-Sanchez, F. & Chavarria, M. (2024). Draft genome sequence of three hydrocarbon-degrading Pseudomonadota strains isolated from an abandoned century-old oil exploration well. ASM Journals, Environmental Microbiology, Vol. 13. [CrossRef]

- Amin, A., Naveed, M., Sarwar, A., Rasheed, S., Saleem, H.G.M., Latif, Z. & Bechthold, A. (2022). In vitro and in silico Studies Reveal Bacillus cereus AA-18 as a Potential Candidate for Bioremediation of Mercury-Contaminated Wastewater. Front. Microbiol. Vol-13. [CrossRef]

- Khan, A., Gupta, A., Singh, P., Mishra, A. K., Ranjan, R. K., & Srivastava, A. (2019). Siderophore-assisted cadmium hyperaccumulation in Bacillus subtilis. International Microbiology. [CrossRef]

- Gardy, J.L., Laird, M.R., Chen, F., Rey, S., Walsh, C.J., Ester, M. & Brinkman, F.S.L. (2005). PSORTb v.2.0: expanded prediction of bacterial protein subcellular localization and insights gained from comparative proteome analysis. Comparative Study. Vol, 21. Pages 617-623. [CrossRef]

- Peabody, M.A., Lau, W.Y.V., Hoad, G.R., Jia, B., Maguire, F., Gray, K.L., Beiko, R.G., Brinkman, F.S.L. (2020). PSORTm: a bacteria and archaeal protein subcellular localization prediction tool tor metagenomics data. Bioinformatics. Vol-36. Pages: 3043-3048. [CrossRef]

- Lou, Feiyue., Okoye, C.O.. Gao, L., Jiang, H., Wu, Y., Wang, Y., Li, X. & Jiang, J. (2023). Whole-genome sequence analysis reveals phenanthrene and pyrene degradation pathways in newly isolated bacteria Klebsiella michiganensis EF4 and Klebsiella oxytoca ETN19. Microbiological Research. Vol-273. 127410. [CrossRef]

- Louvado, A., Gomes, N.G.M., Simões, N.M.Q., Almeida, A., Cleary, D.F.R. & Cunha, A. (2015). Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in deep sea sediments: Microbe-pollutant interactions in a remote enviroment. Science of the Total Environment. Vol 526, Pages: 312-328. [CrossRef]

- Bukowska, B., Mokra, K. & Michalowicz, J. (2022). Benzo[a]pyrene—Environmental Occurrence, Human Exposure, and Mechanisms of Toxicity. Int J Mol Sci, 23, 6348. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.F. & Tam, N.F.Y. (2011). Microbial community dynamics and biodegradation of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in polluted marine sediments in Hong Kong. Marine Pollution Bulletin. Vol-63. Pages: 424-430. [CrossRef]

| Quality control FastQ | Results |

|---|---|

| High-quality readings | 10,613,744 (97,24%) |

| Readings due to low quality | 19.324 (0,18%) |

| Contained too much pollution | 336 reads (0,001539%) |

| Readings too short | 5.8520(0,026808%) |

| Cut-out adapters | Yes |

| Properties and characteristics | Total |

|---|---|

| Sequence size Genome | 4,798,267 |

| No of Scaffolds | |

| Contigs >= 0 bp/1000bp/50000bp | 51/28/12 |

| N50/L50 | 415,254/3 |

| No of CDS | 4460 |

| No of rRNA/tRNA/tmRNA | 2/77/1 |

| GC% | 54.38 |

| KEEG Mapper Reconstruction | |

| KEEG Orthology (KO) | 2671 |

| Metabolism protein | 1487 |

| Genetic information processing | 690 |

| Signaling and cellular processes | 829 |

| Carbohydrate Metabolism | 318 |

| Amino acid Metabolism | 157 |

| Nucleotide Metabolism | 104 |

| Metabolism of cofactors and vitamins | 134 |

| Energy Metabolism | 101 |

| EggNOG-Mapper | |

| COG | 4349 |

| Pfam | 4186 |

| GO | 2540 |

| CAZy | 77 |

| BIGG | 1064 |

| Genomes NCBI | FAST ANI | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Strain/ | GENBANK | SCIENTIFIC NAME | ANI score | Fragment lenght | Total Fragment |

| Crenshaw | GCA_016027695.1 | Enterobacter asburiae | 87.8055 | 1250 | 1586 |

| ATCC 35953 | GCA_001521715.1 | Enterobacter asburiae | 87.8536 | 1241 | 1586 |

| JM-458T.1 | GCA_900180435.1 | Enterobacter asburiae | 87.8124 | 1282 | 1586 |

| E1 | GCA_008364625.1 | Enterobacter dykesii | 87.8021 | 1262 | 1586 |

| DSM 16690 | GCA_001729805.1 | Enterobacter roggenkampii | 87.6385 | 1258 | 1586 |

| CCA6 | GCA_009176645.1 | Enterobacter oligotrophicus | 87.547 | 1218 | 1586 |

| WCHECL1597 | GCA_002939185.1 | Enterobacter sichuanensis | 87.326 | 1248 | 1586 |

| WCHECl-C4 | GCA_001984825.2 | Enterobacter chengduensis | 87.3321 | 1295 | 1586 |

| DSM-13645 | GCA_001729765.1 | Enterobacter kobei | 87.1635 | 1222 | 1586 |

| FDAARGOS 1428 | GCA_019047785.1 | Enterobacter cancerogenus | 86.5672 | 1214 | 1586 |

| EB-247 | GCA_900324475.1 | Enterobacter bugandensis | 87.4329 | 1290 | 1586 |

| ATCC BAA-2102 | GCA_001654845.1 | Enterobacter soli | 86.5295 | 1222 | 1586 |

| ATCC 23216 | GCA_000735515.1 | Leclercia adecarboxylata | 83.6121 | 1043 | 1586 |

| SB6411 | GCA_902158555.1 | Klebsiella spallanzanii | 80.9556 | 840 | 1586 |

| ATCC 8090 | GCA_011064845.1 | Citrobacter freundii | 81.5917 | 820 | 1586 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).