Submitted:

11 September 2024

Posted:

12 September 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Alternative Explanations

Diet

Genetics

Comorbid Disorders and Risk Factors.

Did Neighboring Towns Have High Rates of CVD?

Outmigration and Birthplace

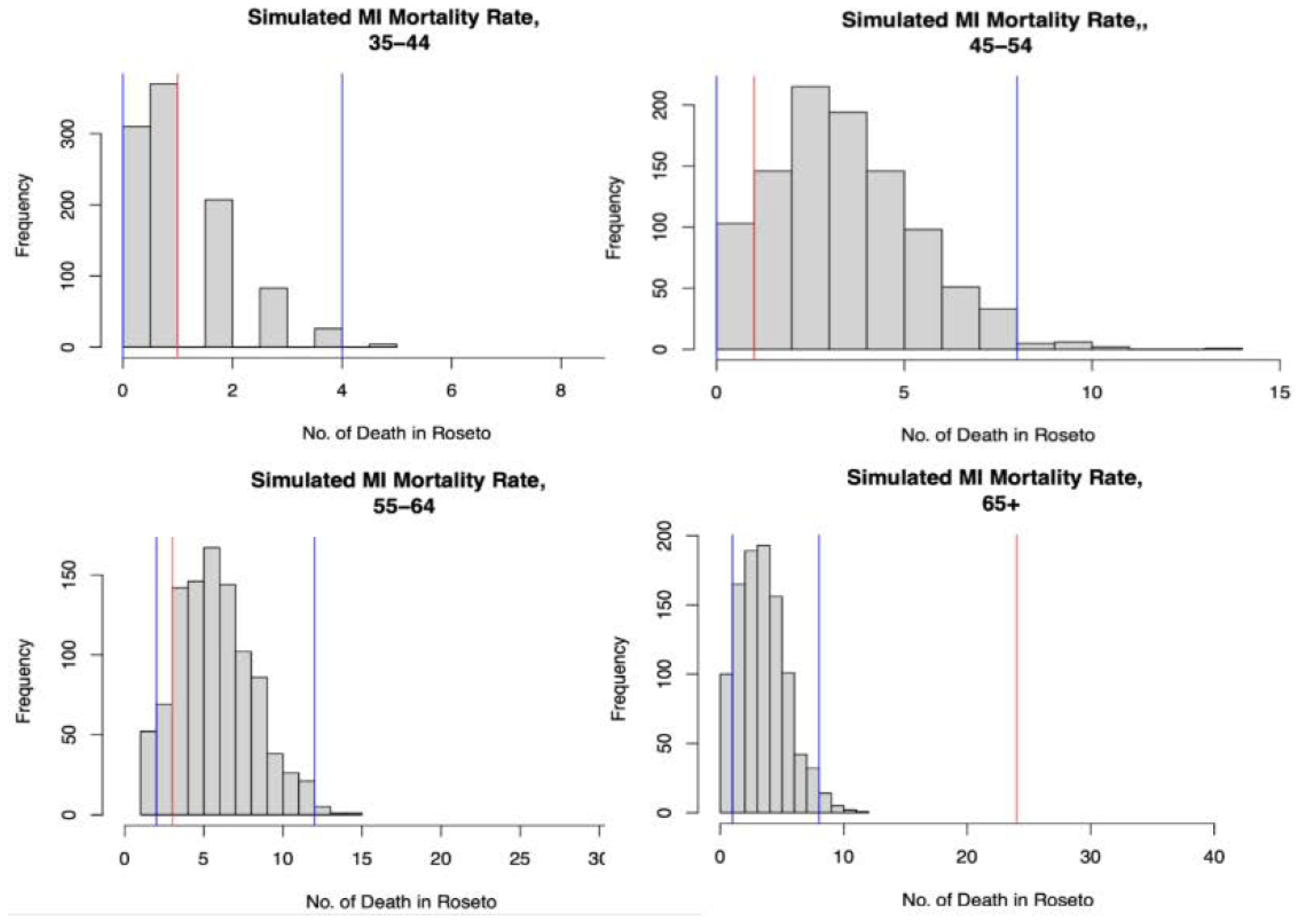

Chance

Discussion

Authors’ Contributions

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Stout C, Morrow J, Brandt EN, Wolf S. Unusually low incidence of death from myocardial infarction: study of an Italian American community in Pennsylvania. JAMA. 1964, 188, 845–849. [Google Scholar]

- Kannel WB, Dawber TR, Kagan A, Revotskie N, Stokes III J. Factors of risk in the development of coronary heart disease—six-year follow-up experience: the Framingham Study. Annals of internal medicine. 1961, 55, 33–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keys, A. Arteriosclerotic heart disease in Roseto, Pennsylvania. JAMA. 1966, 195, 93–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keys A. Seven countries. Seven Countries. Harvard University Press; Cambridge, MA, 2013.

- Page IH, Allen EV, Chamberlain FL, Keys A, et al. Central Committee for Medical and Community Program of the American Heart Assiciation. Dietary fat and its relation to heart attacks and strokes. Circulation. 1961, 23, 133–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sacks FM, Lichtenstein AH, Wu JH, et al. Dietary fats and cardiovascular disease: a presidential advisory from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2017, 136, e1–e23. [Google Scholar]

- Bruhn JG, Wolf S. The Roseto Story: An Anatomy of Health. Lippincott Williams Wilkins, Philadelophia; 1980.

- Wolf S, Grace KL, Bruhn J, Stout C. Roseto revisited: further data on the incidence of myocardial infarction in Roseto and neighboring Pennsylvania communities. Trans Amer Clinical Climatol Assoc. 1974, 85, 100. [Google Scholar]

- Tough H, Siegrist J, Fekete C. Social relationships, mental health and wellbeing in physical disability: a systematic review. BMC public health. 2017, 17, 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Coughlin, SS. Social determinants of colorectal cancer risk, stage, and survival: A systematic review. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2020, 35, 985–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gladwell M. Outliers: The story of success. Little, Brown; 2002.

- Keys, A. Arteriosclerotic heart disease in Roseto, Pennsylvania. JAMA 1966, 195, 137–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pressler M, Devinsky J, Duster M, et al. Dietary transitions and health outcomes in four populations – Systematic Review. Front Nutr 2022, 9, 748305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National diabetes statistics report: Estimates of diabetes and its burden in the United States, 2014.Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services; 2014.

- Tversky, A and Kahneman, D. Belief in the low of small numbers. Psychological Bulletin 1971, 76, 105–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lew, EA. Some implications of mortality statistics relating to coronary artery disease. J Chron Dise. 1957, 6, 192–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page IH, Stare FJ, Corcoran A, et al. Atherosclerosis and the fat content of the diet. Circulation. 1957, 16, 163–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keys, A. Atherosclerosis: a problem in newer public health. J Mt Sinai Hosp NY 1953, 20, 118–39. [Google Scholar]

- Lee JH, Duster M, Roberts T, Devinsky O. United States dietary trends since 1800, Lack of association between saturated fatty acid consumption and non-communicable diseases. Front Nutr 2022, 8, 748847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keys A, Anderston JT, Grande F. Serum cholesterol response in man: diet fat and intrinsic responsiveness. Circulation 1959, 19, 201–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haneuse, S. Distinguishing selection bias and confounding bias in comparative effectiveness research. Medical Care. 2016, 54, e23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel SS. The eclipse of the community study: The Roseto study in historical context. PhD Dissertation, Univ of Pennsylvania, 2007.

- Wolf S, Bruhn JG. The Power of Clan. The influences of human relationships on heart disease. Transaction Pubs, New Brunswick, NJ, 1993.

- Roman GC, Jackson RE, Reis J, et al. Extra-virgin olive oil for potential prevention of Alzheimer disease. Rev Neurol 2019, 175, 705–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Roseto_effect.

- Mann, GV. Diet-Heart: end of an era. New Engl J Med 1977, 297, 644–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yerushalmy J, Hilleboe HE. Fat in the diet and mortality from heart disease; a methodological note. NY State Med J 1957, 57, 2343–54.

- Taubes G. Good calories, bad calories. Knopf, NY 2007.

- Ramsden CE, Zamora D, Majchrzak-Hong S, et al. Re-evaluation of the traditional diet-heart hypothesis: analysis of recovered data from Minnesota Coronary Experiment (1968-73). Brit Med J 2016, 353, i1246. [Google Scholar]

- Kannel WB, Gordon T. The Framingham Study. Section 24. The Framingham Diet Study. US Government Printing, 1968.

- Mann GV. A short history of the Diet/Heart Hypothesis. In: Mann GV, ed. Coronary Heart Disease. The Dietary Sense and Nonsense. Janus Pub Co., London, England. 1993, pp 1-17.

| Age group | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cohort | Year | Sex | 35-44 | 45-54 | 55-64 | 65+ |

| Framingham Heart study | 1955-1964 | M | 5.6 | 35.2 | 81.5 | 31.5 |

| F | 2.5 | 7.6 | 20.2 | 32.8 | ||

| Total | 4.3 | 23.5 | 55.6 | 32.1 | ||

| 1965-1974 | M | 0 | 11.7 | 42.9 | 87.1 | |

| F | 0 | 4.2 | 19.8 | 68 | ||

| Total | 0 | 8.1 | 31.9 | 78 | ||

| Roseto study | 1955-1964 | M | 8.3 | 9.8 | 29 | 211.3 |

| F | 0 | 0 | 15.9 | 120 | ||

| Total | 8.3 | 9.8 | 22.5 | 165.7 | ||

| 1965-1974 | M | 33.3 | 55 | 92.8 | 268.7 | |

| F | 0 | 0 | 15.9 | 181.8 | ||

| Total | 33.3 | 55 | 54.4 | 225.3 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).