Submitted:

12 September 2024

Posted:

13 September 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Popular Summary

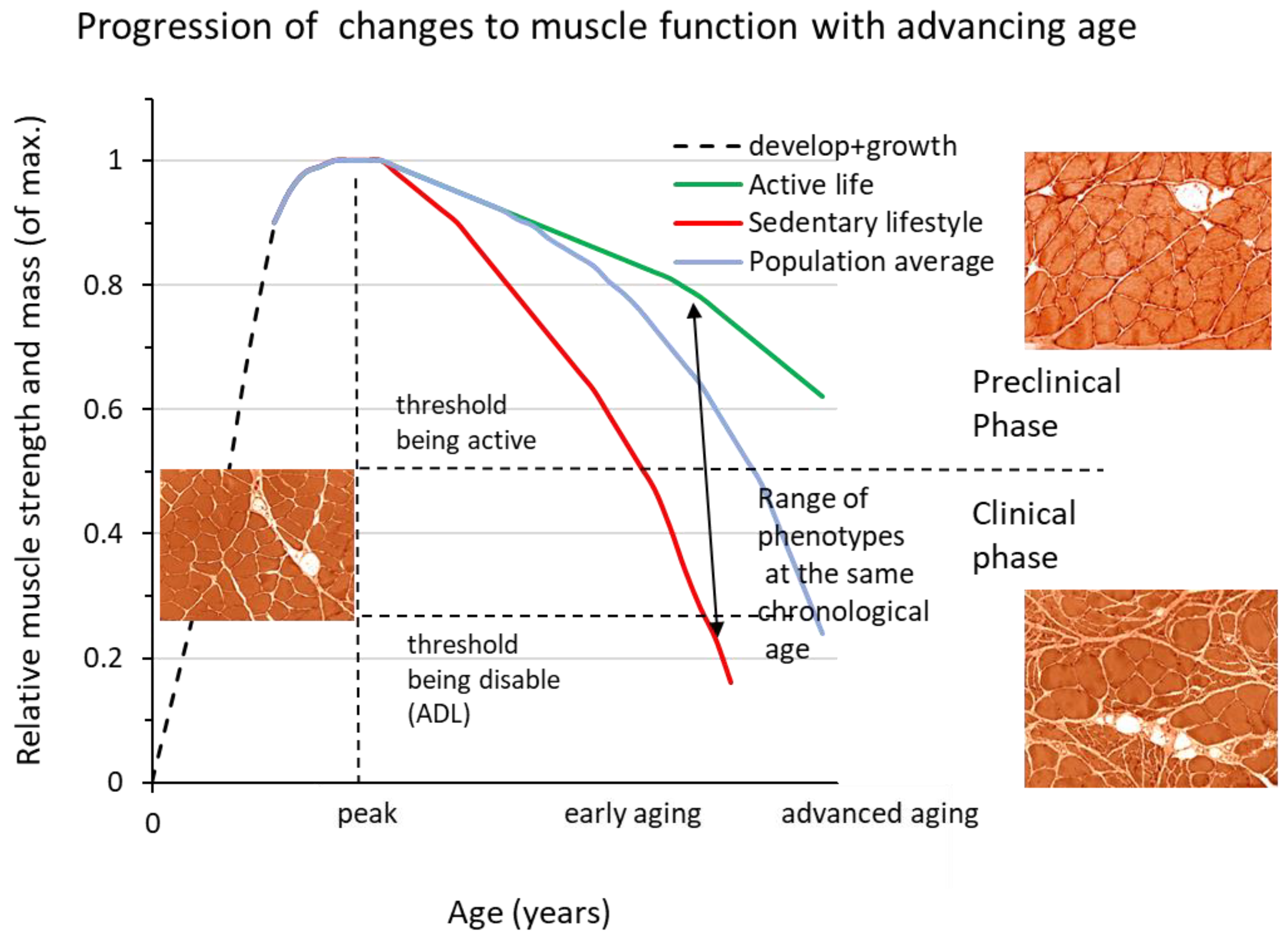

2. Growing Old

3. Loosing Muscle Strength and Mass

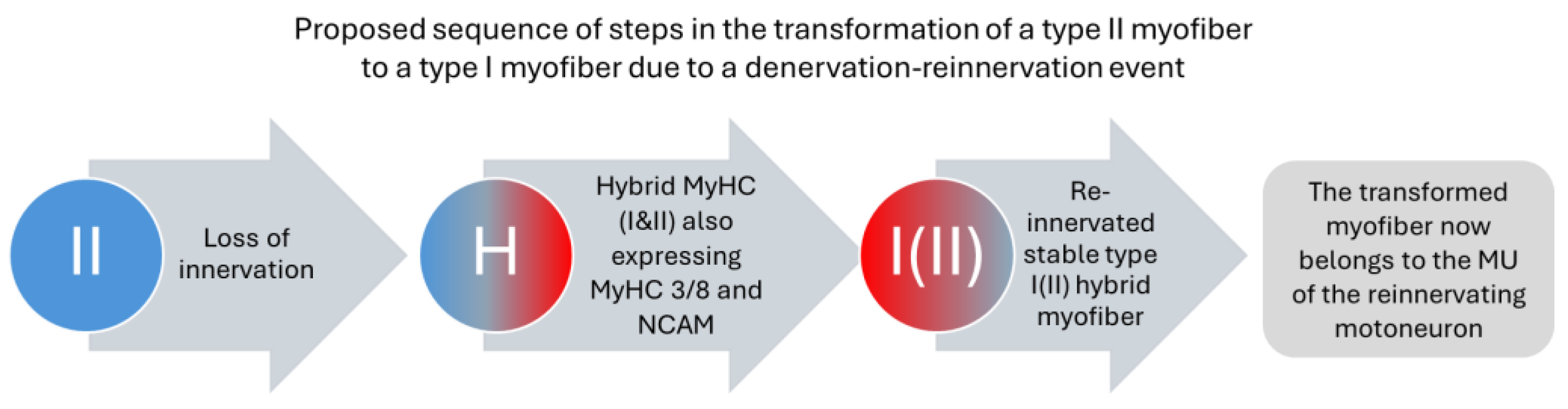

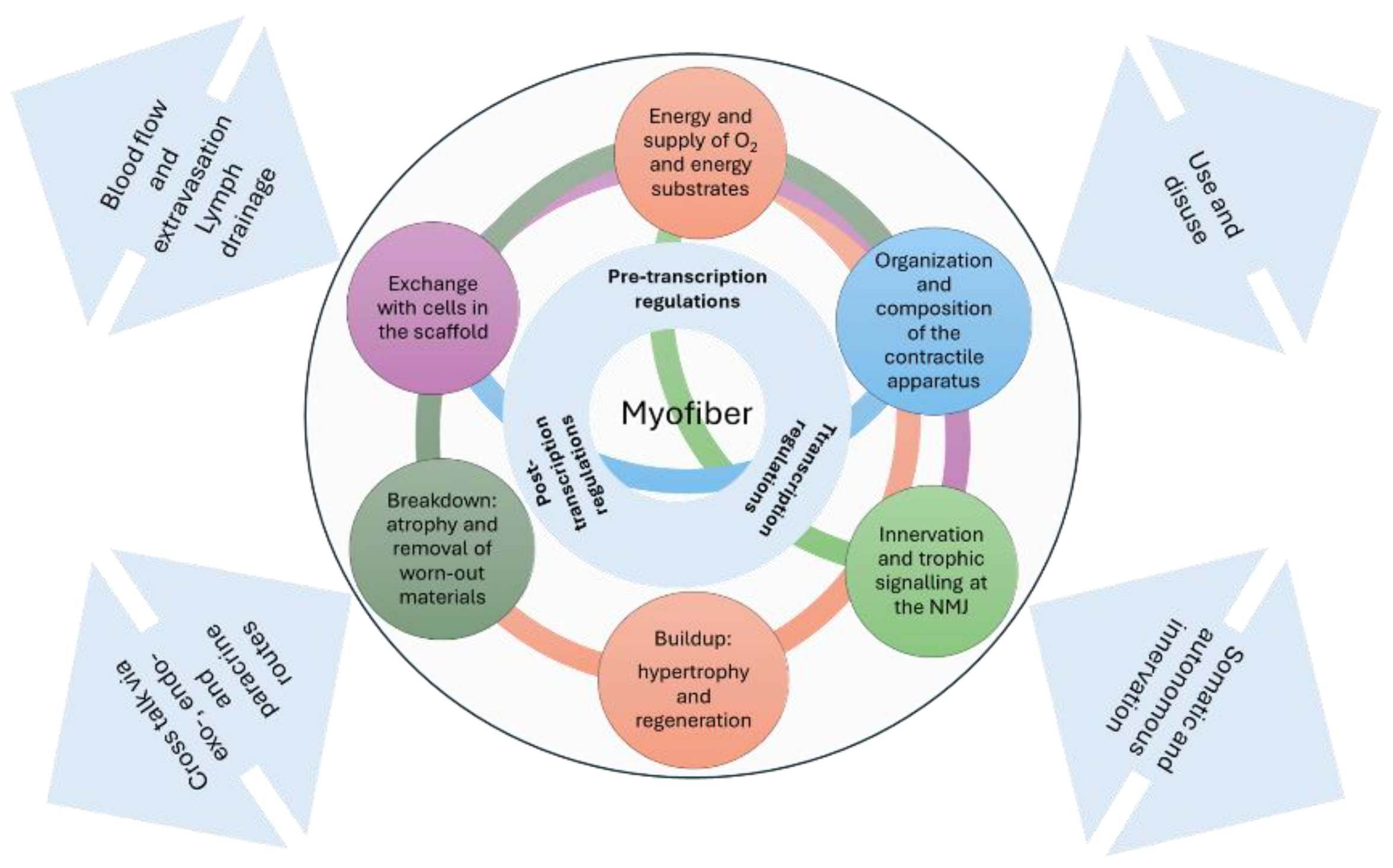

3.1. The Motor Unit

3.2. The Muscle Scaffold

4. Cellular Senescence

4.1. Interventions to Impede Sarcopenia

Exercise

4.2. Biochemical Approaches to Halt Sarcopenia

5. Concluding Remarks

Author Contributions

Funding

Competing Interests

References

- Gustafsson T, Ulfhake B. Sarcopenia: What Is the Origin of This Aging-Induced Disorder? Front Genet. 2021;12:688526. Epub 20210702. PubMed PMID: 34276788; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC8285098. [CrossRef]

- Wijsman CA, Rozing MP, Streefland TC, le Cessie S, Mooijaart SP, Slagboom PE, et al. Familial longevity is marked by enhanced insulin sensitivity. Aging Cell. 2011;10(1):114-21. Epub 2010/11/13. PubMed PMID: 21070591. [CrossRef]

- Kaplanis J, Gordon A, Shor T, Weissbrod O, Geiger D, Wahl M, et al. Quantitative analysis of population-scale family trees with millions of relatives. Science. 2018;360(6385):171-5. Epub 2018/03/03. PubMed PMID: 29496957; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC6593158. [CrossRef]

- Gustafsson T, Ulfhake B. Sarcopenia: What Is the Origin of This Aging-Induced Disorder? Frontiers in Genetics. 2021;12(914). [CrossRef]

- Etienne J, Liu C, Skinner CM, Conboy MJ, Conboy IM. Skeletal muscle as an experimental model of choice to study tissue aging and rejuvenation. Skelet Muscle. 2020;10(1):4. Epub 20200207. PubMed PMID: 32033591; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC7007696. [CrossRef]

- López-Otín C, Blasco MA, Partridge L, Serrano M, Kroemer G. The hallmarks of aging. Cell. 2013;153(6):1194-217. Epub 2013/06/12. PubMed PMID: 23746838; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC3836174. [CrossRef]

- Altun M, Grönholdt-Klein, M., Wang, L. and Ulfhake, B. Cellular Degradation Machineries in Age-Related Loss of Muscle Mass (Sarcopenia). 2012. In: Senescence [Internet]. InTech; [269-86]. Available from: http://www.intechopen.com/articles/show/title/cellular-degradation-machineries-in-age-related-loss-of-muscle-mass-sarcopenia.

- Altun M, Besche HC, Overkleeft HS, Piccirillo R, Edelmann MJ, Kessler BM, et al. Muscle wasting in aged, sarcopenic rats is associated with enhanced activity of the ubiquitin proteasome pathway. J Biol Chem. 2010;285(51):39597-608. Epub 2010/10/14. [CrossRef]

- M110.129718 [pii]. PubMed PMID: 20940294; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC3000941.

- Cruz-Jentoft AJ, Baeyens JP, Bauer JM, Boirie Y, Cederholm T, Landi F, et al. Sarcopenia: European consensus on definition and diagnosis: Report of the European Working Group on Sarcopenia in Older People. Age Ageing. 2010;39(4):412-23. Epub 2010/04/16. [CrossRef]

- 10.1093/ageing/afq034. PubMed PMID: 20392703; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC2886201.

- Cruz-Jentoft AJ, Bahat G, Bauer J, Boirie Y, Bruyère O, Cederholm T, et al. Sarcopenia: revised European consensus on definition and diagnosis. Age Ageing. 2019;48(1):16-31. Epub 2018/10/13. PubMed PMID: 30312372; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC6322506. [CrossRef]

- Chen LK, Woo J, Assantachai P, Auyeung TW, Chou MY, Iijima K, et al. Asian Working Group for Sarcopenia: 2019 Consensus Update on Sarcopenia Diagnosis and Treatment. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2020;21(3):300-7.e2. Epub 20200204. PubMed PMID: 32033882. [CrossRef]

- Studenski SA, Peters KW, Alley DE, Cawthon PM, McLean RR, Harris TB, et al. The FNIH Sarcopenia Project: Rationale, Study Description, Conference Recommendations, and Final Estimates. The Journals of Gerontology: Series A. 2014;69(5):547-58. [CrossRef]

- A LIFECOURSE APPROACH TO HEALTH. WHO/NMH/HPS/00.2.

- Cao L, Morley JE. Sarcopenia Is Recognized as an Independent Condition by an International Classification of Disease, Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-10-CM) Code. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2016;17(8):675-7. PubMed PMID: 27470918. [CrossRef]

- Trappe S. Master athletes. Int J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab. 2001;11 Suppl:S196-207. PubMed PMID: 11915921.

- Ganse B, Kleerekoper A, Knobe M, Hildebrand F, Degens H. Longitudinal trends in master track and field performance throughout the aging process: 83,209 results from Sweden in 16 athletics disciplines. Geroscience. 2020;42(6):1609-20. Epub 2020/10/14. PubMed PMID: 33048301. [CrossRef]

- Baker AB, Tang YQ. Aging performance for masters records in athletics, swimming, rowing, cycling, triathlon, and weightlifting. Exp Aging Res. 2010;36(4):453-77. PubMed PMID: 20845122. [CrossRef]

- Lazarus NR, Harridge SDR. Declining performance of master athletes: silhouettes of the trajectory of healthy human ageing? J Physiol. 2017;595(9):2941-8. Epub 20170118. PubMed PMID: 27808406; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC5407960. [CrossRef]

- Gava P, Kern H, Carraro U. Age-associated power decline from running, jumping, and throwing male masters world records. Exp Aging Res. 2015;41(2):115-35. PubMed PMID: 25724012. [CrossRef]

- Westerståhl M, Jansson E, Barnekow-Bergkvist M, Aasa U. Longitudinal changes in physical capacity from adolescence to middle age in men and women. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):14767. Epub 20181003. PubMed PMID: 30283061; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC6170499. [CrossRef]

- GrönholdtKlein M, Gorzi A, Wang L, Edström E, Rullman E, Altun M, et al. Emergence and Progression of Behavioral Motor Deficits and Skeletal Muscle Atrophy across the Adult Lifespan of the Rat. Biology (Basel). 2023;12(9). Epub 20230828. PubMed PMID: 37759577; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC10526071. [CrossRef]

- Larsson L, Degens H, Li M, Salviati L, Lee YI, Thompson W, et al. Sarcopenia: Aging-Related Loss of Muscle Mass and Function. Physiol Rev. 2019;99(1):427-511. Epub 2018/11/15. PubMed PMID: 30427277; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC6442923 drugs are held by Mayo Clinic. This work has been revised by the Mayo Clinic Conflict of Interest Review Board and was conducted in compliance with Mayo Clinic conflict of interest policies. No other conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors. [CrossRef]

- Hepple RT, Rice CL. Innervation and neuromuscular control in ageing skeletal muscle. J Physiol. 2016;594(8):1965-78. PubMed PMID: 26437581; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC4933121. [CrossRef]

- Tintignac LA, Brenner HR, Ruegg MA. Mechanisms Regulating Neuromuscular Junction Development and Function and Causes of Muscle Wasting. Physiol Rev. 2015;95(3):809-52. PubMed PMID: 26109340. [CrossRef]

- Willadt S, Nash M, Slater C. Age-related changes in the structure and function of mammalian neuromuscular junctions. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2018;1412(1):41-53. Epub 2018/01/02. PubMed PMID: 29291259. [CrossRef]

- Gutmann E. Age changes in the neuromuscular system [by] E. Gutmann and V. Hanzlikova. Hanzlikova V, editor. Bristol: Scientechnica; 1972.

- Edström E, Altun M, Bergman E, Johnson H, Kullberg S, Ramírez-León V, et al. Factors contributing to neuromuscular impairment and sarcopenia during aging. Physiol Behav. 2007;92(1-2):129-35. Epub 2007/06/26. PubMed PMID: 17585972. [CrossRef]

- Rowan SL, Rygiel K, Purves-Smith FM, Solbak NM, Turnbull DM, Hepple RT. Denervation causes fiber atrophy and myosin heavy chain co-expression in senescent skeletal muscle. PLoS One. 2012;7(1):e29082. Epub 20120103. PubMed PMID: 22235261; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC3250397. [CrossRef]

- Cowen T, Ulfhake B, King RHM. Aging in the Peripheral Neurvous System. Peripheral Neuropathy. 1. Philadelphia: Elsevier Saunders; 2005. p. 483-507.

- Johnson H, Ulfhake B, Dagerlind A, Bennett GW, Fone KC, Hökfelt T. The serotoninergic bulbospinal system and brainstem-spinal cord content of serotonin-, TRH-, and substance P-like immunoreactivity in the aged rat with special reference to the spinal cord motor nucleus. Synapse. 1993;15(1):63-89. Epub 1993/09/01. PubMed PMID: 7508641. [CrossRef]

- Kudina LP, Andreeva RE. Repetitive doublet firing in human motoneurons: evidence for interaction between common synaptic drive and plateau potential in natural motor control. J Neurophysiol. 2019;122(1):424-34. Epub 20190605. PubMed PMID: 31166815. [CrossRef]

- Fuglevand AJ, Dutoit AP, Johns RK, Keen DA. Evaluation of plateau-potential-mediated 'warm up' in human motor units. J Physiol. 2006;571(Pt 3):683-93. Epub 20060119. PubMed PMID: 16423860; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC1805803. [CrossRef]

- Alaburda A, Perrier JF, Hounsgaard J. Mechanisms causing plateau potentials in spinal motoneurones. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2002;508:219-26. PubMed PMID: 12171115. [CrossRef]

- Ramírez-León V, Kullberg S, Hjelle OP, Ottersen OP, Ulfhake B. Increased glutathione levels in neurochemically identified fibre systems in the aged rat lumbar motor nuclei. Eur J Neurosci. 1999;11(8):2935-48. PubMed PMID: 10457189. [CrossRef]

- Kullberg S, Ramírez-León V, Johnson H, Ulfhake B. Decreased axosomatic input to motoneurons and astrogliosis in the spinal cord of aged rats. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 1998;53(5):B369-79. PubMed PMID: 9754135. [CrossRef]

- Orssatto LBR, Borg DN, Pendrith L, Blazevich AJ, Shield AJ, Trajano GS. Do motoneuron discharge rates slow with aging? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Mech Ageing Dev. 2022;203:111647. Epub 20220223. PubMed PMID: 35218849. [CrossRef]

- Orssatto LBR, Rodrigues P, Mackay K, Blazevich AJ, Borg DN, Souza TRd, et al. Intrinsic motor neuron excitability is increased after resistance training in older adults. Journal of Neurophysiology. 2023;129(3):635-50. PubMed PMID: 36752407. [CrossRef]

- Gutman B, Hanzlikova V. Age changes in the neuromuscular system. Scientechnica Ltd, Bristol. 1972:1-20.

- Power GA, Allen MD, Gilmore KJ, Stashuk DW, Doherty TJ, Hepple RT, et al. Motor unit number and transmission stability in octogenarian world class athletes: Can age-related deficits be outrun? J Appl Physiol (1985). 2016;121(4):1013-20. Epub 2016/11/01. PubMed PMID: 27013605; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC5142311. [CrossRef]

- Korhonen MT, Cristea A, Alén M, Häkkinen K, Sipilä S, Mero A, et al. Aging, muscle fiber type, and contractile function in sprint-trained athletes. J Appl Physiol (1985). 2006;101(3):906-17. Epub 2006/05/13. PubMed PMID: 16690791. [CrossRef]

- Drey M, Sieber CC, Degens H, McPhee J, Korhonen MT, Müller K, et al. Relation between muscle mass, motor units and type of training in master athletes. Clin Physiol Funct Imaging. 2016;36(1):70-6. Epub 2014/10/28. PubMed PMID: 25345553. [CrossRef]

- Piasecki M, Ireland A, Coulson J, Stashuk DW, Hamilton-Wright A, Swiecicka A, et al. Motor unit number estimates and neuromuscular transmission in the tibialis anterior of master athletes: evidence that athletic older people are not spared from age-related motor unit remodeling. Physiol Rep. 2016;4(19). Epub 2016/10/04. PubMed PMID: 27694526; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC5064139. [CrossRef]

- Chakravarty EF, Hubert HB, Lingala VB, Fries JF. Reduced Disability and Mortality Among Aging Runners: A 21-Year Longitudinal Study. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2008;168(15):1638-46. [CrossRef]

- Franco I, Fernandez-Gonzalo R, Vrtacnik P, Lundberg TR, Eriksson M, Gustafsson T. Healthy skeletal muscle aging: The role of satellite cells, somatic mutations and exercise. Int Rev Cell Mol Biol. 2019;346:157-200. Epub 2019/05/28. PubMed PMID: 31122394. [CrossRef]

- Gopinath SD, Rando TA. Stem cell review series: aging of the skeletal muscle stem cell niche. Aging Cell. 2008;7(4):590-8. Epub 20080628. PubMed PMID: 18462272. [CrossRef]

- Joseph GA, Wang SX, Jacobs CE, Zhou W, Kimble GC, Tse HW, et al. Partial Inhibition of mTORC1 in Aged Rats Counteracts the Decline in Muscle Mass and Reverses Molecular Signaling Associated with Sarcopenia. Mol Cell Biol. 2019;39(19). Epub 20190911. PubMed PMID: 31308131; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC6751631. [CrossRef]

- Fuqua JD, Lawrence MM, Hettinger ZR, Borowik AK, Brecheen PL, Szczygiel MM, et al. Impaired proteostatic mechanisms other than decreased protein synthesis limit old skeletal muscle recovery after disuse atrophy. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. 2023;14(5):2076-89. Epub 20230714. PubMed PMID: 37448295; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC10570113. [CrossRef]

- Edstrom E, Altun M, Hagglund M, Ulfhake B. Atrogin-1/MAFbx and MuRF1 are downregulated in aging-related loss of skeletal muscle. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2006;61(7):663-74. PubMed PMID: 16870627.

- Magliulo L, Bondi D, Pini N, Marramiero L, Di Filippo ES. The wonder exerkines-novel insights: a critical state-of-the-art review. Mol Cell Biochem. 2022;477(1):105-13. Epub 20210923. PubMed PMID: 34554363; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC8755664. [CrossRef]

- Cornish SM, Bugera EM, Duhamel TA, Peeler JD, Anderson JE. A focused review of myokines as a potential contributor to muscle hypertrophy from resistance-based exercise. European Journal of Applied Physiology. 2020;120(5):941-59. [CrossRef]

- Mancinelli R, Checcaglini F, Coscia F, Gigliotti P, Fulle S, Fanò-Illic G. Biological Aspects of Selected Myokines in Skeletal Muscle: Focus on Aging. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(16). Epub 20210807. PubMed PMID: 34445222; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC8395159. [CrossRef]

- Kwon JH, Moon KM, Min KW. Exercise-Induced Myokines can Explain the Importance of Physical Activity in the Elderly: An Overview. Healthcare (Basel). 2020;8(4). Epub 20201001. PubMed PMID: 33019579; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC7712334. [CrossRef]

- Son JS, Chae SA, Testroet ED, Du M, Jun HP. Exercise-induced myokines: a brief review of controversial issues of this decade. Expert Rev Endocrinol Metab. 2018;13(1):51-8. Epub 20171219. PubMed PMID: 30063442. [CrossRef]

- Barbalho SM, Prado Neto EV, De Alvares Goulart R, Bechara MD, Baisi Chagas EF, Audi M, et al. Myokines: a descriptive review. J Sports Med Phys Fitness. 2020;60(12):1583-90. Epub 20200623. PubMed PMID: 32586076. [CrossRef]

- Kirk B, Feehan J, Lombardi G, Duque G. Muscle, Bone, and Fat Crosstalk: the Biological Role of Myokines, Osteokines, and Adipokines. Curr Osteoporos Rep. 2020;18(4):388-400. PubMed PMID: 32529456. [CrossRef]

- Plikus MV, Wang X, Sinha S, Forte E, Thompson SM, Herzog EL, et al. Fibroblasts: Origins, definitions, and functions in health and disease. Cell. 2021;184(15):3852-72. PubMed PMID: 34297930; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC8566693. [CrossRef]

- Chapman MA, Meza R, Lieber RL. Skeletal muscle fibroblasts in health and disease. Differentiation. 2016;92(3):108-15. Epub 20160606. PubMed PMID: 27282924; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC5079803. [CrossRef]

- Contreras O, Rossi FMV, Theret M. Origins, potency, and heterogeneity of skeletal muscle fibro-adipogenic progenitors-time for new definitions. Skelet Muscle. 2021;11(1):16. Epub 20210701. PubMed PMID: 34210364; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC8247239. [CrossRef]

- Esteves de Lima J, Relaix F. Master regulators of skeletal muscle lineage development and pluripotent stem cells differentiation. Cell Regen. 2021;10(1):31. Epub 20211001. PubMed PMID: 34595600; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC8484369. [CrossRef]

- McKee TJ, Perlman G, Morris M, Komarova SV. Extracellular matrix composition of connective tissues: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):10542. Epub 20190722. PubMed PMID: 31332239; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC6646303. [CrossRef]

- Birch HL. Extracellular Matrix and Ageing. Subcell Biochem. 2018;90:169-90. PubMed PMID: 30779010. [CrossRef]

- Csapo R, Gumpenberger M, Wessner B. Skeletal Muscle Extracellular Matrix - What Do We Know About Its Composition, Regulation, and Physiological Roles? A Narrative Review. Front Physiol. 2020;11:253. Epub 20200319. PubMed PMID: 32265741; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC7096581. [CrossRef]

- Karamanos NK, Theocharis AD, Piperigkou Z, Manou D, Passi A, Skandalis SS, et al. A guide to the composition and functions of the extracellular matrix. Febs j. 2021;288(24):6850-912. Epub 20210323. PubMed PMID: 33605520. [CrossRef]

- Kirkendall DT, Garrett WE. Function and biomechanics of tendons. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 1997;7(2):62-6. PubMed PMID: 9211605. [CrossRef]

- Kannus P. Structure of the tendon connective tissue. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2000;10(6):312-20. PubMed PMID: 11085557. [CrossRef]

- Wang X, Sathe AA, Smith GR, Ruf-Zamojski F, Nair V, Lavine KJ, et al. Heterogeneous origins and functions of mouse skeletal muscle-resident macrophages. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2020;117(34):20729-40. Epub 20200813. PubMed PMID: 32796104; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC7456122. [CrossRef]

- Buvinic S, Balanta-Melo J, Kupczik K, Vásquez W, Beato C, Toro-Ibacache V. Muscle-Bone Crosstalk in the Masticatory System: From Biomechanical to Molecular Interactions. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2020;11:606947. Epub 20210301. PubMed PMID: 33732211; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC7959242. [CrossRef]

- Chapman MA, Mukund K, Subramaniam S, Brenner D, Lieber RL. Three distinct cell populations express extracellular matrix proteins and increase in number during skeletal muscle fibrosis. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2017;312(2):C131-c43. Epub 20161123. PubMed PMID: 27881411; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC5336596. [CrossRef]

- Gumpenberger M, Wessner B, Graf A, Narici MV, Fink C, Braun S, et al. Remodeling the Skeletal Muscle Extracellular Matrix in Older Age-Effects of Acute Exercise Stimuli on Gene Expression. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21(19). Epub 20200925. PubMed PMID: 32992998; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC7583913. [CrossRef]

- Wan M, Gray-Gaillard EF, Elisseeff JH. Cellular senescence in musculoskeletal homeostasis, diseases, and regeneration. Bone Res. 2021;9(1):41. Epub 20210910. PubMed PMID: 34508069; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC8433460. [CrossRef]

- Hayflick L, Moorhead PS. Exp Cell Res. 1961;25. [CrossRef]

- Moiseeva V, Cisneros A, Sica V, Deryagin O, Lai Y, Jung S, et al. Senescence atlas reveals an aged-like inflamed niche that blunts muscle regeneration. Nature. 2023;613(7942):169-78. Epub 20221221. PubMed PMID: 36544018; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC9812788. [CrossRef]

- Zhu Y. Aging Cell. 2015;14. [CrossRef]

- Arora S. Med. 2021;2. [CrossRef]

- Twomey LT, Taylor JR. Old age and physical capacity: use it or lose it. Aust J Physiother. 1984;30(4):115-20. PubMed PMID: 25026448. [CrossRef]

- Churchward-Venne TA, Tieland M, Verdijk LB, Leenders M, Dirks ML, de Groot LC, et al. There Are No Nonresponders to Resistance-Type Exercise Training in Older Men and Women. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2015;16(5):400-11. Epub 20150221. PubMed PMID: 25717010. [CrossRef]

- Phu S, Boersma D, Duque G. Exercise and Sarcopenia. J Clin Densitom. 2015;18(4):488-92. Epub 20150610. PubMed PMID: 26071171. [CrossRef]

- McKendry J, Breen L, Shad BJ, Greig CA. Muscle morphology and performance in master athletes: A systematic review and meta-analyses. Ageing Res Rev. 2018;45:62-82. Epub 20180430. PubMed PMID: 29715523. [CrossRef]

- Kirkendall DT, Garrett WE, Jr. The effects of aging and training on skeletal muscle. Am J Sports Med. 1998;26(4):598-602. PubMed PMID: 9689386. [CrossRef]

- Deschenes MR, Kraemer WJ. Performance and physiologic adaptations to resistance training. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2002;81(11 Suppl):S3-16. PubMed PMID: 12409807. [CrossRef]

- Polito MD, Papst RR, Farinatti P. Moderators of strength gains and hypertrophy in resistance training: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Sports Sci. 2021;39(19):2189-98. Epub 20210512. PubMed PMID: 33977848. [CrossRef]

- Borde R, Hortobágyi T, Granacher U. Dose-Response Relationships of Resistance Training in Healthy Old Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Sports Med. 2015;45(12):1693-720. PubMed PMID: 26420238; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC4656698. [CrossRef]

- Wall BT, Dirks ML, van Loon LJ. Skeletal muscle atrophy during short-term disuse: implications for age-related sarcopenia. Ageing Res Rev. 2013;12(4):898-906. Epub 2013/08/21. PubMed PMID: 23948422. [CrossRef]

- McKendry J, Shad BJ, Smeuninx B, Oikawa SY, Wallis G, Greig C, et al. Comparable Rates of Integrated Myofibrillar Protein Synthesis Between Endurance-Trained Master Athletes and Untrained Older Individuals. Front Physiol. 2019;10:1084. Epub 20190830. PubMed PMID: 31543824; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC6728413. [CrossRef]

- Grosicki GJ, Gries KJ, Minchev K, Raue U, Chambers TL, Begue G, et al. Single muscle fibre contractile characteristics with lifelong endurance exercise. J Physiol. 2021;599(14):3549-65. Epub 20210615. PubMed PMID: 34036579. [CrossRef]

- Tseng BS, Marsh DR, Hamilton MT, Booth FW. Strength and aerobic training attenuate muscle wasting and improve resistance to the development of disability with aging. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 1995;50 Spec No:113-9. PubMed PMID: 7493203.

- Gu Q, Wang B, Zhang XF, Ma YP, Liu JD, Wang XZ. Chronic aerobic exercise training attenuates aortic stiffening and endothelial dysfunction through preserving aortic mitochondrial function in aged rats. Exp Gerontol. 2014;56:37-44. Epub 20140305. PubMed PMID: 24607516. [CrossRef]

- Mikkelsen UR, Couppé C, Karlsen A, Grosset JF, Schjerling P, Mackey AL, et al. Life-long endurance exercise in humans: circulating levels of inflammatory markers and leg muscle size. Mech Ageing Dev. 2013;134(11-12):531-40. Epub 20131125. PubMed PMID: 24287006. [CrossRef]

- Fleenor BS. Large elastic artery stiffness with aging: novel translational mechanisms and interventions. Aging Dis. 2013;4(2):76-83. Epub 20121211. PubMed PMID: 23696949; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC3659253.

- Marcell TJ, Hawkins SA, Wiswell RA. Leg strength declines with advancing age despite habitual endurance exercise in active older adults. J Strength Cond Res. 2014;28(2):504-13. PubMed PMID: 24263662. [CrossRef]

- Straight CR, Fedewa MV, Toth MJ, Miller MS. Improvements in skeletal muscle fiber size with resistance training are age-dependent in older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Appl Physiol (1985). 2020;129(2):392-403. Epub 20200723. PubMed PMID: 32702280; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC7473942. [CrossRef]

- Alian S, Baker RG, Wood S. Rural casualty crashes on the Kings Highway: A new approach for road safety studies. Accid Anal Prev. 2016;95(Pt A):8-19. PubMed PMID: 27372441. [CrossRef]

- Lundberg TR, Gustafsson T. Fibre hypertrophy, satellite cell and myonuclear adaptations to resistance training: Have very old individuals reached the ceiling for muscle fibre plasticity? Acta Physiol (Oxf). 2019;227(1):e13287. Epub 20190513. PubMed PMID: 31009166. [CrossRef]

- Ferketich AK, Kirby TE, Alway SE. Cardiovascular and muscular adaptations to combined endurance and strength training in elderly women. Acta Physiol Scand. 1998;164(3):259-67. PubMed PMID: 9853013. [CrossRef]

- Irving BA, Lanza IR, Henderson GC, Rao RR, Spiegelman BM, Nair KS. Combined training enhances skeletal muscle mitochondrial oxidative capacity independent of age. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2015;100(4):1654-63. Epub 20150119. PubMed PMID: 25599385; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC4399307. [CrossRef]

- Lundberg TR, Fernandez-Gonzalo R, Gustafsson T, Tesch PA. Aerobic exercise does not compromise muscle hypertrophy response to short-term resistance training. J Appl Physiol (1985). 2013;114(1):81-9. Epub 2012/10/30. PubMed PMID: 23104700. [CrossRef]

- Cadore EL, Izquierdo M. How to simultaneously optimize muscle strength, power, functional capacity, and cardiovascular gains in the elderly: an update. Age (Dordr). 2013;35(6):2329-44. Epub 20130104. PubMed PMID: 23288690; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC3825007. [CrossRef]

- Cadore EL, Menger E, Teodoro JL, da Silva LXN, Boeno FP, Umpierre D, et al. Functional and physiological adaptations following concurrent training using sets with and without concentric failure in elderly men: A randomized clinical trial. Exp Gerontol. 2018;110:182-90. Epub 20180613. PubMed PMID: 29908345. [CrossRef]

- Leuchtmann AB, Mueller SM, Aguayo D, Petersen JA, Ligon-Auer M, Flück M, et al. Resistance training preserves high-intensity interval training induced improvements in skeletal muscle capillarization of healthy old men: a randomized controlled trial. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):6578. Epub 20200420. PubMed PMID: 32313031; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC7171189. [CrossRef]

- Wilhelm EN, Rech A, Minozzo F, Botton CE, Radaelli R, Teixeira BC, et al. Concurrent strength and endurance training exercise sequence does not affect neuromuscular adaptations in older men. Exp Gerontol. 2014;60:207-14. Epub 20141113. PubMed PMID: 25449853. [CrossRef]

- Moghadam BH, Bagheri R, Ashtary-Larky D, Tinsley GM, Eskandari M, Wong A, et al. The Effects of Concurrent Training Order on Satellite Cell-Related Markers, Body Composition, Muscular and Cardiorespiratory Fitness in Older Men with Sarcopenia. J Nutr Health Aging. 2020;24(7):796-804. PubMed PMID: 32744578. [CrossRef]

- Zhao M, Veeranki SP, Magnussen CG, Xi B. Recommended physical activity and all cause and cause specific mortality in US adults: prospective cohort study. Bmj. 2020;370:m2031. Epub 20200701. PubMed PMID: 32611588; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC7328465. [CrossRef]

- Stanga S, Boido M, Kienlen-Campard P. How to Build and to Protect the Neuromuscular Junction: The Role of the Glial Cell Line-Derived Neurotrophic Factor. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;22(1). Epub 2020/12/31. PubMed PMID: 33374485; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC7794999. [CrossRef]

- Besse-Patin A, Montastier E, Vinel C, Castan-Laurell I, Louche K, Dray C, et al. Effect of endurance training on skeletal muscle myokine expression in obese men: identification of apelin as a novel myokine. Int J Obes (Lond). 2014;38(5):707-13. Epub 20130827. PubMed PMID: 23979219. [CrossRef]

- Zofkie W, Southard SM, Braun T, Lepper C. Fibroblast growth factor 6 regulates sizing of the muscle stem cell pool. Stem Cell Reports. 2021;16(12):2913-27. Epub 20211104. PubMed PMID: 34739848; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC8693628. [CrossRef]

- Cosgrove BD, Gilbert PM, Porpiglia E, Mourkioti F, Lee SP, Corbel SY, et al. Rejuvenation of the muscle stem cell population restores strength to injured aged muscles. Nat Med. 2014;20(3):255-64. Epub 20140216. PubMed PMID: 24531378; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC3949152. [CrossRef]

- Dorsey SG, Lovering RM, Renn CL, Leitch CC, Liu X, Tallon LJ, et al. Genetic deletion of trkB.T1 increases neuromuscular function. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2012;302(1):C141-53. Epub 20111005. PubMed PMID: 21865582; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC3328911. [CrossRef]

- Gyorkos AM, Spitsbergen JM. GDNF content and NMJ morphology are altered in recruited muscles following high-speed and resistance wheel training. Physiol Rep. 2014;2(2):e00235. Epub 20140225. PubMed PMID: 24744904; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC3966253. [CrossRef]

- Wan M, Gray-Gaillard EF, Elisseeff JH. Cellular senescence in musculoskeletal homeostasis, diseases, and regeneration. Bone Research. 2021;9(1):41. [CrossRef]

- Wong, Carissa (2024-05-15). "How to kill the 'zombie' cells that make you age". Nature. 629 (8012): 518–520.

- Becker C, Lord SR, Studenski SA, Warden SJ, Fielding RA, Recknor CP, et al. Myostatin antibody (LY2495655) in older weak fallers: a proof-of-concept, randomised, phase 2 trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2015;3(12):948-57. Epub 20151027. PubMed PMID: 26516121. [CrossRef]

- Leuchtmann AB, Furrer R, Steurer SA, Schneider-Heieck K, Karrer-Cardel B, Sagot Y, et al. Interleukin-6 potentiates endurance training adaptation and improves functional capacity in old mice. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. 2022. Epub 20220222. PubMed PMID: 35191221. [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury S, Schulz L, Palmisano B, Singh P, Berger JM, Yadav VK, et al. Muscle-derived interleukin 6 increases exercise capacity by signaling in osteoblasts. J Clin Invest. 2020;130(6):2888-902. PubMed PMID: 32078586; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC7260002. [CrossRef]

- Vinel C, Lukjanenko L, Batut A, Deleruyelle S, Pradere JP, Le Gonidec S, et al. The exerkine apelin reverses age-associated sarcopenia. Nat Med. 2018;24(9):1360-71. Epub 2018/08/01. PubMed PMID: 30061698. [CrossRef]

- Chen YY, Chiu YL, Kao TW, Peng TC, Yang HF, Chen WL. Cross-sectional associations among P3NP, HtrA, Hsp70, Apelin and sarcopenia in Taiwanese population. BMC Geriatr. 2021;21(1):192. Epub 20210320. PubMed PMID: 33743591; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC7980650. [CrossRef]

- Castan-Laurell I, Dray C, Valet P. The therapeutic potentials of apelin in obesity-associated diseases. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2021;529:111278. Epub 20210407. PubMed PMID: 33838166. [CrossRef]

- Saral S, Topçu A, Alkanat M, Mercantepe T, Akyıldız K, Yıldız L, et al. Apelin-13 activates the hippocampal BDNF/TrkB signaling pathway and suppresses neuroinflammation in male rats with cisplatin-induced cognitive dysfunction. Behav Brain Res. 2021;408:113290. Epub 20210415. PubMed PMID: 33845103. [CrossRef]

- Roh HT, Cho SY, So WY. A Cross-Sectional Study Evaluating the Effects of Resistance Exercise on Inflammation and Neurotrophic Factors in Elderly Women with Obesity. J Clin Med. 2020;9(3). Epub 20200320. PubMed PMID: 32244926; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC7141497. [CrossRef]

- Mrówczyński W. Health Benefits of Endurance Training: Implications of the Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor-A Systematic Review. Neural Plast. 2019;2019:5413067. Epub 2019/07/26. PubMed PMID: 31341469; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC6613032. [CrossRef]

- Carrero-Rojas G, Benítez-Temiño B, Pastor AM, Davis López de Carrizosa MA. Muscle Progenitors Derived from Extraocular Muscles Express Higher Levels of Neurotrophins and their Receptors than other Cranial and Limb Muscles. Cells. 2020;9(3):747. PubMed PMID:. [CrossRef]

- Petrocelli JJ, McKenzie AI, de Hart N, Reidy PT, Mahmassani ZS, Keeble AR, et al. Disuse-induced muscle fibrosis, cellular senescence, and senescence-associated secretory phenotype in older adults are alleviated during re-ambulation with metformin pre-treatment. Aging Cell. 2023;22(11):e13936. Epub 20230724. PubMed PMID: 37486024; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC10652302. [CrossRef]

- Stewart CE, Rittweger J. Adaptive processes in skeletal muscle: molecular regulators and genetic influences. J Musculoskelet Neuronal Interact. 2006;6(1):73-86. PubMed PMID: 16675891.

- Seeman E, Hopper JL, Young NR, Formica C, Goss P, Tsalamandris C. Do genetic factors explain associations between muscle strength, lean mass, and bone density? A twin study. Am J Physiol. 1996;270(2 Pt 1):E320-7. PubMed PMID: 8779955. [CrossRef]

- Huygens W, Thomis MA, Peeters MW, Vlietinck RF, Beunen GP. Determinants and upper-limit heritabilities of skeletal muscle mass and strength. Can J Appl Physiol. 2004;29(2):186-200. PubMed PMID: 15064427. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).