Submitted:

12 September 2024

Posted:

13 September 2024

You are already at the latest version

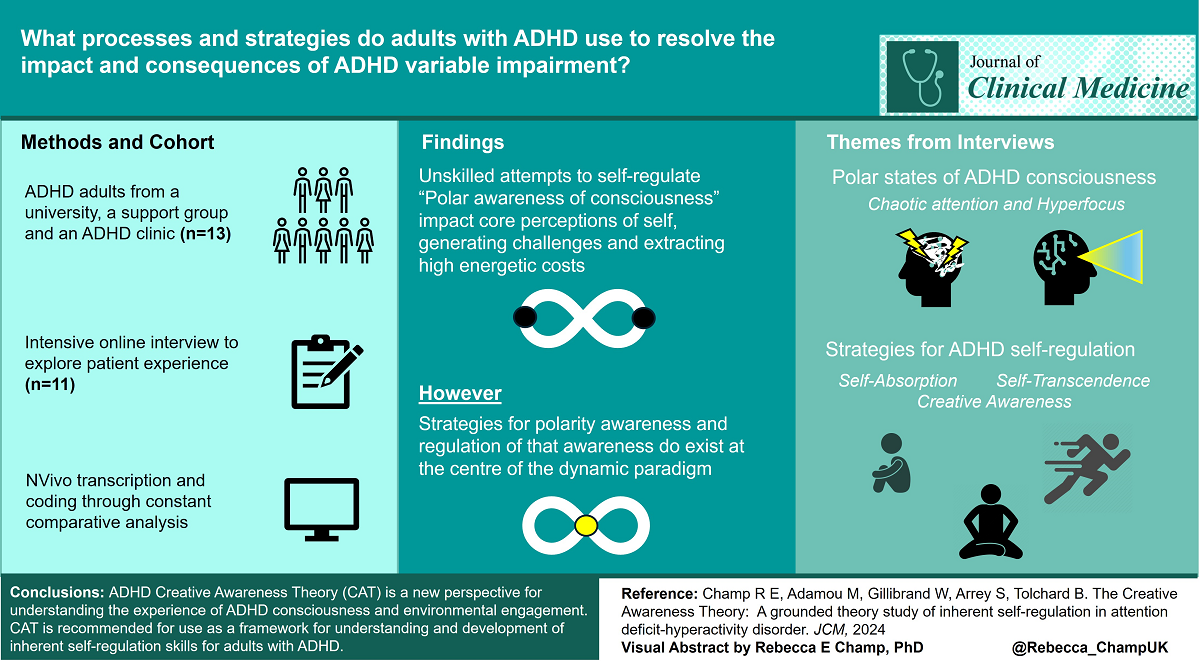

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials & Methods

2.1. Study Design and Data Collection Tools

2.1.1. Method

Philosophical Framework

Methodological Approach

2.1.2. Initial Phase

2.1.3. Conceptual-Theoretical Phase

2.1.4. Confirmatory-Selective Phase

2.1.5. Reflexive Phase

2.2. Data Collection and Analysis

2.2.1. Intensive Interviews

- Selection of participants who have first-hand experience

- In-depth exploration of participants’ experience and situations

- Objective of obtaining detailed responses

- Emphasis on understanding participants’ perspective, meanings, and experience

- Practice of following up on unanticipated areas of inquiry, hints, and implicit views and accounts of actions [56]

2.2.3. Memos or Field Notes

2.2.4. NVivo

2.2.5. Ethics and Permissions

2.2.6. Pre-Study Preparation

2.2.7. Data Protection and Data Storage

2.2.8. Sampling and Participants

2.2.9. Inclusion Criteria

- Confirmed diagnosis of ADHD

- Age 18 or older

- Access to computer or smartphone with an internet connection

2.2.10. Exclusion Criteria

- Comorbid diagnosis (e.g. Autism, Bi-polar, Intellectual Disabilities, Learning Difficulties, Traumatic Brain Injury, Psychosis or Tourette’s)

- Substance abuse disorders

- Other mental health disorders (e.g. PTSD, Oppositional Defiant Disorder)

- Personality Disorders

2.3. Procedure

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

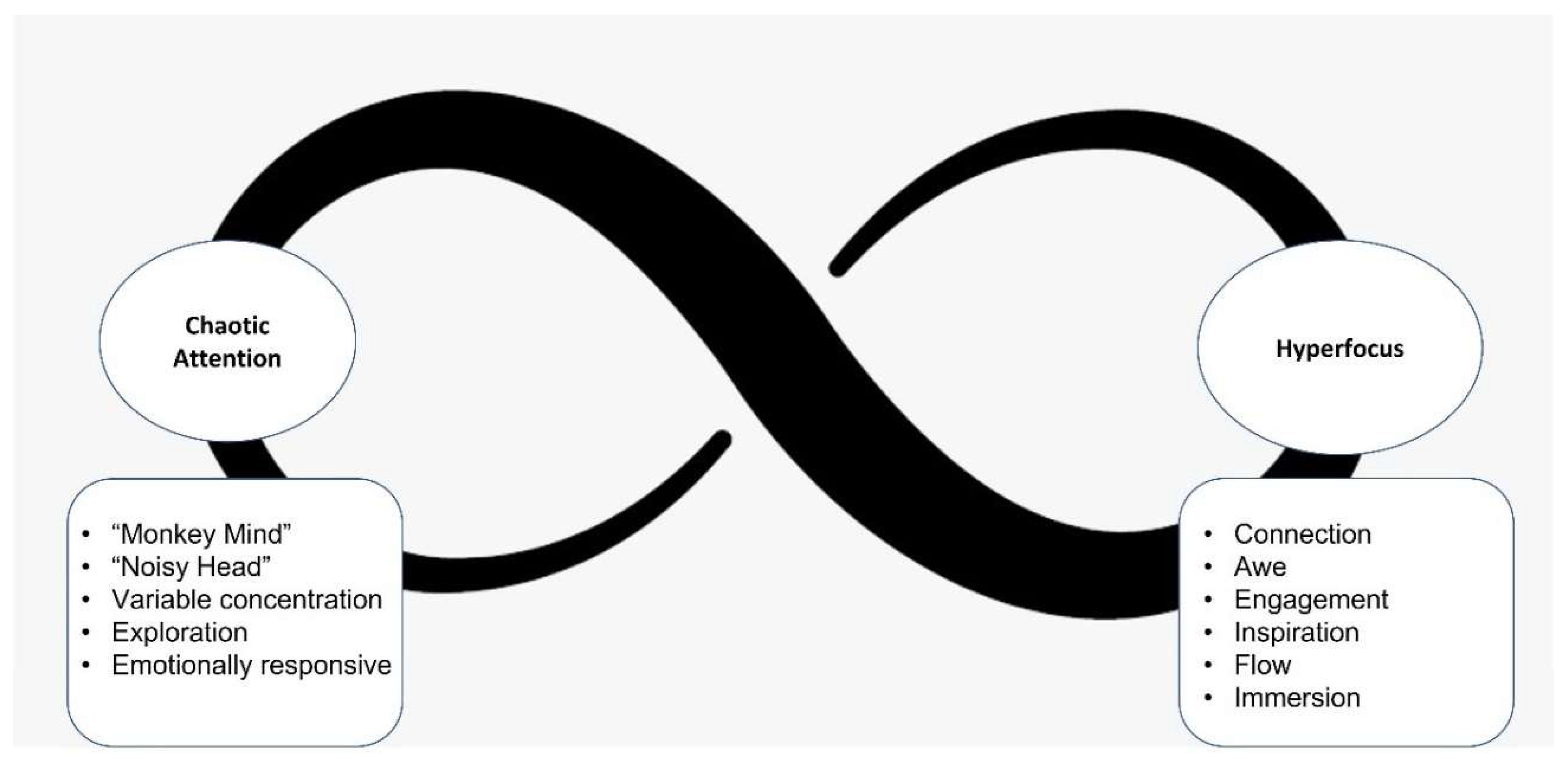

3.1. Polar Awareness of Difference

3.1.1. Environmental Engagement

3.1.2. Positive Characteristics of ADHD

3.2. Polar Awareness of ADHD Consciousness

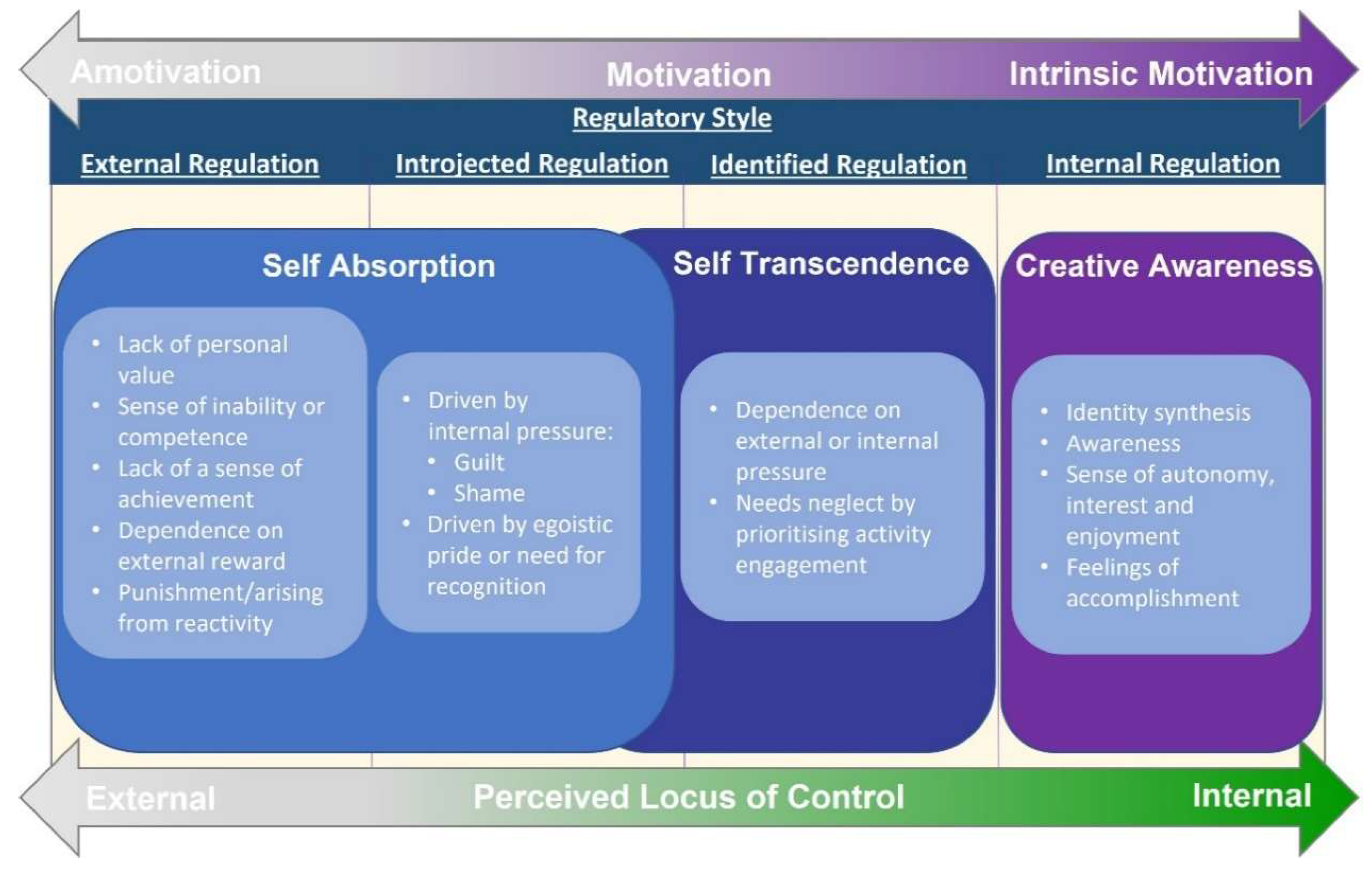

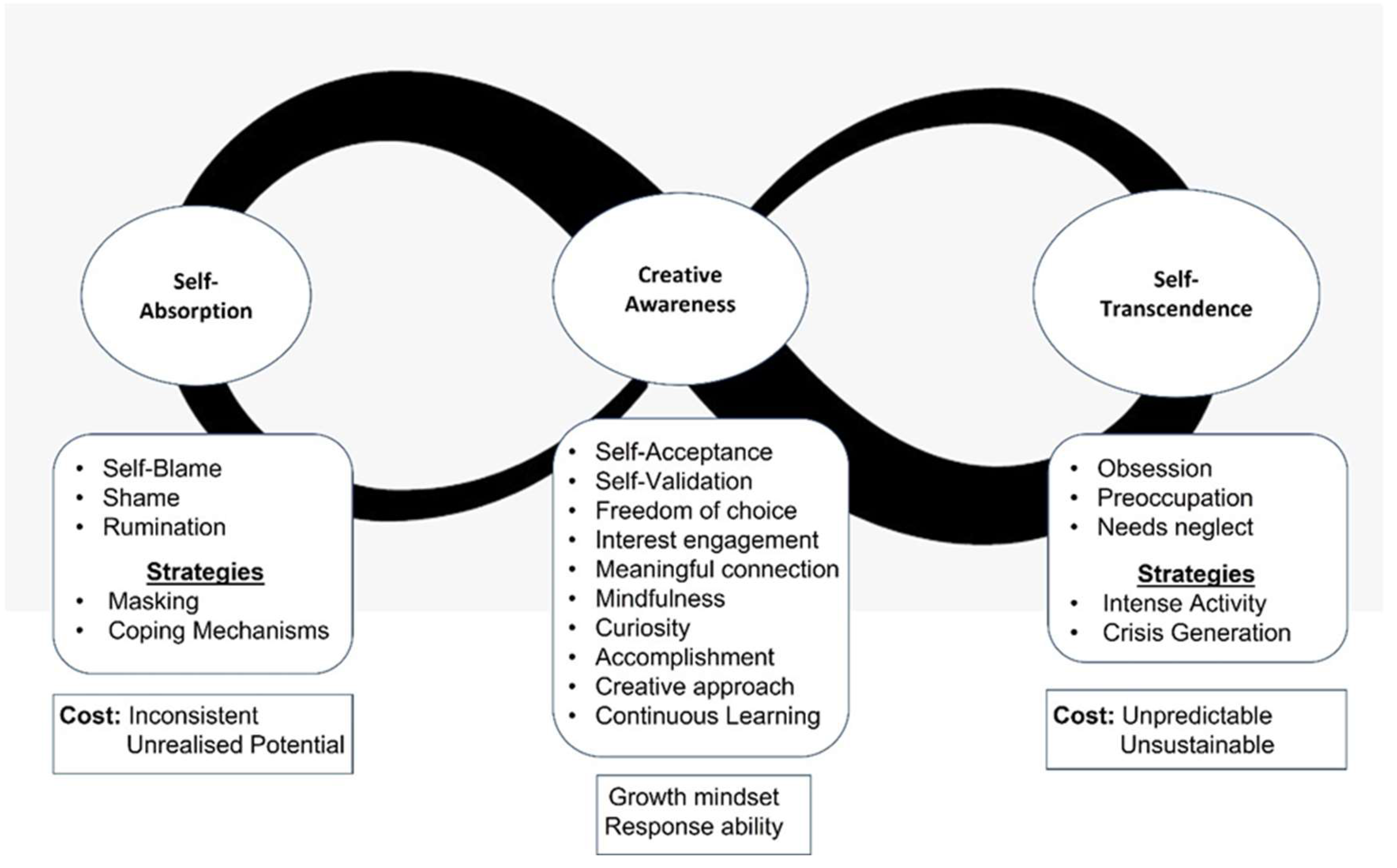

3.3. Self-Regulation of ADHD Consciousness

3.4. Self-Absorption

3.5. Self-Transcendence

3.6. Creative Awareness

4. Discussion

4.1. Challenges with ADHD Self-Regulation and Identity Construction

4.2. Resources for ADHD Self-Regulation

5. Limitations & Further Research

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Champ, R. E.; Adamou, M.; and Tolchard, B. “The impact of psychological theory on the treatment of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) in adults: A scoping review,” PLoS One, 2021, vol. 16, no. 12, p. e0261247. [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, T. The Power of neurodiversity: Unleashing the advantages of your differently wired brain. Philadelphia, PA: Da Capo Press, 2010.

- Barack, D. L.; Ludwig, V. U.; Parodi, F.; Ahmed, N.; Brannon, E. M.; Ramakrishnan, A.; & Platt, M. L. “Attention deficits linked with proclivity to explore while foraging.,” Proceedings. Biol. Sci., 2024, vol. 291, no. 2017, p. 20222584. [CrossRef]

- Barkley, R. A. Executive functions: What they are, how they work, and why they evolved. New York, NY: Guildford Press, 2012.

- Hartmann, T. ADD: A different perception. Grass Valley, California: Underwood Books, 1997.

- Issa, J.-P. J. “Distinguishing originality from creativity in ADHD: An assessment of creative personality, self-perception, and cognitive style among Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder adults,” Buffalo State College, 2015. [Online]. Available: http://digitalcommons.buffalostate.edu/creativetheses/25.

- Philipsen, A.; Richter, H.; Peters, J.; Alm, B.; Sobanski, E.; Colla, M.; Münzebrock, M.; Scheel, C.; Jacob, C.; Perlov, E.; Tebartz van Elst, L.; & Hesslinger, B. “Structured group psychotherapy in adults with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: Results of an open multicentre study.,” J. Nerv. Ment. Dis., 2007, vol. 195, no. 12, pp. 1013–9, Dec. [CrossRef]

- Sedgwick, J. A.; Merwood, A.; and Asherson, P. “The positive aspects of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: A qualitative investigation of successful adults with ADHD,” ADHD Atten. Deficit Hyperact. Disord., 2018, vol. 11, pp. 241–253. [CrossRef]

- Stein, D. J.; Fan, J.; Fossella, J.; and Russell, V. A. “Inattention and hyperactivity-impulsivity: Psychobiological and evolutionary underpinnings of ADHD,” CNS Spectr., 2007, vol. 12, no. 3, pp. 190–196. [CrossRef]

- Taylor H. and Vestergaard, M. D. “Developmental dyslexia: Disorder or specialization in exploration?,” Front. Psychol., 2022, vol. 13, no. June, pp. 1–19. [CrossRef]

- White H. A. and Shah, P. “Creative style and achievement in adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder,” Pers. Individ. Dif., 2011, vol. 50, no. 5, pp. 673–677. [CrossRef]

- Brooks, R. B. “Nurturing islands of competence: Is there really room for a strength-based model in the treatment of ADHD?,” ADHD Rep., 2001, vol. 9, no. 2, pp. 1–5. [CrossRef]

- Wilmshurst, L.; Peele, M.; and Wilmshurst, L. “Resilience and Well-being in College Students With and Without a Diagnosis of ADHD,” J. Atten. Disord., 2011, vol. 15, no. 1, pp. 11–17. [CrossRef]

- Barkley, R. A. “Executive functioning and self regulation viewed as an extended phenotype: Implications of the theory of ADHD and its treatment.,” in Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: A handbook for diagnosis and treatment, R. A. Barkley, Ed., New York: Guilford Press, 2014, ch. 16, pp. 405–434.

- Mueller, A. K.; Fuermaier, A. B. M.; Koerts, J.; and Tucha, L. “Stigma in attention deficit hyperactivity disorder,” ADHD Atten. Deficit Hyperact. Disord., 2012, vol. 4, no. 3, pp. 101–114. [CrossRef]

- Cook, J.; Knight, E.; Hume, I.; and Qureshi, A. “The self-esteem of adults diagnosed with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD): A systematic review of the literature,” ADHD Atten. Deficit Hyperact. Disord., 2014, vol. 6, no. 4, pp. 249–268. [CrossRef]

- Barkley, R. A.; Murphy, K. R.; and Fischer, M. ADHD in adults: What the science says. New York: Guilford Press, 2010.

- Newark, P. E.; Elsässer, M.; and Stieglitz, R.-D. “Self-esteem, self-efficacy, and resources in adults with ADHD,” J. Atten. Disord., 2016, vol. 20, no. 3, pp. 279–290. [CrossRef]

- Newark, P. E. and Stieglitz, R.-D. “Therapy-relevant factors in adult ADHD from a cognitive behavioural perspective,” ADHD Atten. Deficit Hyperact. Disord., 2010, vol. 2, no. 2, pp. 59–72. [CrossRef]

- Rostain, A. L. and Ramsay, J. R. “A combined treatment approach for adults with ADHD--results of an open study of 43 patients.,” J. Atten. Disord., 2006, vol. 10, no. 2, pp. 150–159. [CrossRef]

- Young, S. J. and Bramham, J. ADHD in adults: A psychological guide to practice. Chichester, West Sussex: John Wiley & Sons, Inc, 2007.

- Grawe, K. Psychological therapy. Cambridge, MA: Hogrefe & Huber, 2004.

- Ramsay, J. R. Rethinking adult ADHD. Washington D.C.: American Psychological Association, 2020.

- Bjerrum, M. B.; Pedersen, P. U.; and Larsen, P. “Living with symptoms of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in adulthood: A systematic review of qualitative evidence,” JBI Database Syst. Rev. Implement. Reports, 2017, vol. 15, no. 4, pp. 1080–1153. [CrossRef]

- Toner, M.; O’Donoghue, T.; and Houghton, S. “Living in chaos and striving for control: How adults with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder deal with their disorder,” Int. J. Disabil. Dev. Educ., 2006, vol. 53, no. 2, pp. 247–261. [CrossRef]

- Ramsay, J. R. and Rostain, A. L. “Adult ADHD research: Current status and future directions,” J. Atten. Disord., 2008, vol. 11, no. 6, pp. 624–627. [CrossRef]

- Ramsay, J. R.; Giwerc, D.; McGrath, R. E.; and Niemiec, R. “Are there virtues associated with adult ADHD?: Comparison of ADHD adults and controls on the VIA inventory of strengths,” in Poster presentation at the 2016 APSARD National Conference, 2016. [Online]. Available: https://www.academia.edu/22356984/Are_There_Character_Strengths_Associated_with_Adult_ADHD_Comparison_of_ADHD_Adults_and_Controls_on_the_VIA_Inventory_of_Strengths.

- Demontis, D.; Walters, R. K.; Martin, J.; Mattheisen, M.; Als, T. D.; Agerbo, E.; Baldursson, G.; Belliveau, R.; Bybjerg-Grauholm, J.; Bækvad-Hansen, M.; Cerrato, F.; Chambert, K.; Churchhouse, C.; Dumont, A.; Eriksson, N.; Gandal, M.; Goldstein, J. I.; Grasby, K. L.; Grove, J.; … Neale, B. M. “Discovery of the first genome-wide significant risk loci for attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder,” Nat. Genet., 2019, vol. 51, no. 1, pp. 63–75. [CrossRef]

- Dipeolu, A. O. “College students with ADHD: Prescriptive concepts for best practices in career development,” J. Career Dev., 2011, vol. 38, no. 5, pp. 408–427. [CrossRef]

- Hallowell, E. and Ratey, J. Driven to distraction. New York: Touchstone, 1994.

- Hartmann, T. and Popkin, M. ADHD: A hunter in a farmer’s world. Rochester, Vermont: Healing Arts Press, 2019.

- Weiss, L. ADD and Creativity. Lanham, MD: Taylor Trade Publishing, 1997.

- Hartmann, T. Living with ADHD. Rochester, Vermont: Healing Arts Press, 2020.

- Weiss, L. Embracing ADHD: A healing perspective. Lanham, MD: Taylor Trade Publishing, 2015.

- Hallowell, E. and Ratey, J. Delivered from Distraction: Getting the most out of life with Attention Deficit Disorder. New York: Ballentine Books, 2006.

- Hallowell, E. and Ratey, J. Answers to Distraction. New York: Anchor Books, 2010.

- Honos-Webb, L. The gift of adult ADHD: How to transform your challenges and build on your strengths. Oakland, CA: New Harbinger Publications, Inc., 2008.

- White, H. A. and Shah, P. “Uninhibited imaginations: Creativity in adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder,” Pers. Individ. Dif., 2006, vol. 40, no. 6, pp. 1121–1131. [CrossRef]

- White, H. A. and Shah, P. “Scope of semantic activation and innovative thinking in college students with ADHD,” Creat. Res. J., 2016, vol. 28, no. 3, pp. 275–282. [CrossRef]

- Boot, N.; Nevicka, B.; and Baas, M. “Creativity in ADHD: Goal-directed motivation and domain specificity,” J. Atten. Disord., 2017, vol. 24, no. 13, pp. 1–10. [CrossRef]

- Boot, N. The creative brain. UvA-DARE (Digital Academic Repository), 2017.

- Hupfeld, K. E.; Abagis, T. R.; and Shah, P. “Living ‘in the zone’: Hyperfocus in adult ADHD,” ADHD Atten. Deficit Hyperact. Disord., 2019, vol. 11, no. 2, pp. 191–208. [CrossRef]

- Lee, J. W.; Seo, K.; and Bahn, G. H. “The positive aspects of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder among famous people,” Psychiatry Investig., 2020, vol. 17, no. 5, pp. 424–431. [CrossRef]

- Wiklund, J.; Patzelt, H.; and Dimov, D. “Entrepreneurship and psychological disorders: How ADHD can be productively harnessed,” J. Bus. Ventur. Insights, 2016, vol. 6, pp. 14–20. [CrossRef]

- Dimic, N. and Orlov, V. “Entrepreneurial tendencies among people with ADHD,” Int. Rev. Entrep., 2014, vol. 13, no. 3, pp. 187–204. [CrossRef]

- Hoogman, M.; Stolte, M.; Baas, M.; and Kroesbergen, E. “Creativity and ADHD: A review of behavioral studies, the effect of psychostimulants and neural underpinnings,” Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev., 2020, vol. 119, no. March, pp. 66–85. [CrossRef]

- Schippers, L. M.; Horstman, L. I.; van de Velde, H.; Pereira, R. R.; Zinkstok, J.; Mostert, J. C.; Greven, C. U.; & Hoogman, M. “A qualitative and quantitative study of self-reported positive characteristics of individuals with ADHD,” Front. Psychiatry, 2022, vol. 13, p. article 922788. [CrossRef]

- Yu, W.; Wiklund, J.; and Pérez-Luño, A. “ADHD symptoms, entrepreneurial orientation (EO), and firm performance,” Entrep. Theory Pract., 2021, vol. 45, no. 1, pp. 92–117. [CrossRef]

- Mahdi, S.; Viljoen, M.; Massuti, R.; Selb, M.; Almodayfer, O.; Karande, S.; de Vries, P. J.; Rohde, L.; & Bölte, S. “An international qualitative study of ability and disability in ADHD using the WHO-ICF framework,” Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry, 2017, vol. 26, no. 10, pp. 1219–1231. [CrossRef]

- Nordby, E. S.; Guribye, F.; Nordgreen, T.; and Lundervold, A. J. “Silver linings of ADHD: A thematic analysis of adults’ positive experiences with living with ADHD,” BMJ Open, 2023, vol. 13, no. 10, p. e72052. [CrossRef]

- White, H. A. “Thinking ‘outside the box’: Unconstrained creative generation in adults with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder,” J. Creat. Behav., 2018, vol. 54, no. 2, pp. 472–483. [CrossRef]

- Fleischmann, A. and Fleischmann, R. H. “Advantages of an ADHD diagnosis in adulthood: Evidence from online narratives,” Qual. Health Res., 2012, vol. 22, no. 11, pp. 1486–1496. [CrossRef]

- Adamou, M. and Jones, S. L. “Quality of life in adult ADHD: A grounded theory approach,” Psychology, 2020, vol. 11, no. 11, pp. 1794–1812. [CrossRef]

- Champ, R. E.; Adamou, M.; and Tolchard, B. “Seeking connection, autonomy, and emotional feedback: A self-determination theory of self-regulation in attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder,” Psychol. Rev., 2022, pp. 1–34. [CrossRef]

- Flick, U. Doing grounded theory. London: SAGE Publications Ltd., 2018.

- Charmaz, K. Constructing Grounded Theory. London: SAGE Publications Ltd., 2014.

- Glaser, B. and Strauss, A. The discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research. New York, NY: Routledge, 1967. [CrossRef]

- Strauss, A. and Corbin, J. Basics of qualitative research: Grounded theory procedures and techniques. London: SAGE Publications Ltd., 1998. [CrossRef]

- Glaser, B. Basics of grounded theory analysis: Emergence vs. forcing. Mill Valley, California: Sociology Press, 1992.

- Gibbs, G. Analysing qualitative data. London: SAGE Publications Ltd., 2018.

- Lempert, L. B. “‘Asking Questions of the data: Memo writing in the grounded theory tradition,’” in The SAGE Handbook of Grounded Theory, Bryant, A. and Charmaz, K. Eds., London: SAGE Publications Ltd., 2007, pp. 245–265.

- Glaser, B. Theoretical sensitivity. Mill Valley, California: Sociology Press, 1978.

- Rogers, C. Client-centered therapy: Its current practice, implications and theory. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin, 1951.

- Bringer, J. D.; Johnston, L. H.; and Brackenridge, C. H. “Maximising transparency in a doctoral thesis: The complexities of writing about the use of QSR*NVIVO within a grounded theory study,” Qual. Res., 2004, vol. 4, no. 2, pp. 247–265.

- Hutchison, A. J.; Johnston, L. H.; and Breckon, J. D. “Using QSR - NVivo to facilitate the development of a grounded theory project : An account of a worked example,” Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol., 2010, vol. 13, no. 4, pp. 283–302. [CrossRef]

- Richards, L. “Qualitative computing--a methods revolution?,” Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol., 2002, vol. 5, no. 3, pp. 263–276. [CrossRef]

- Bazeley, P. Qualitative Data Analysis with NVivo. London: SAGE Publications Ltd., 2007.

- UK Council for Psychotherapy, “UKCP Code of Ethics and Professional Practice,” 2019, UK Council for Psychotherapy, London. [Online]. Available: https://www.psychotherapy.org.uk/media/bkjdm33f/ukcp-code-of-ethics-and-professional-practice-2019.pdf.

- Great Britain: Parliament, “Data Protection Act,” London: Stationary Office. Accessed: Dec. 29, 2014. [Online]. Available: http://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/1998/29/contents.

- Flick, U. An introduction to qualitative research. London: SAGE Publications Ltd., 2018.

- Morse, J. M. “‘Designing funded qualitative research,’” in Strategies of Qualitative Inquiry, N. Denzin and Y. Lincoln, Eds., London: SAGE Publications Ltd., 1998, pp. 56–85.

- HRA & MHRA, “Joint statement on seeking consent by electronic methods,” no. September, pp. 1–11, 2018, [Online]. Available: https://www.hra.nhs.uk/about-us/news-updates/hra-and-mhra-publish-joint-statement-seeking-and-documenting-consent-using-electronic-methods-econsent/.

- Ryan, R. M. and Deci, E. L. Self-determination theory: Basic psychological needs in motivation, development, and wellness. New York, NY: Guilford Press, 2017.

- Champ, R. E.; Adamou, M.; Gillibrand, W.; Arrey, S.; and Tolchard, B. “Dataset for: The Creative Awareness Theory: A grounded theory study of inherent self-regulation in attention deficit-hyperactivity disorder,” 2024, PsychArchives. [CrossRef]

- Young, S. J.; Bramham, J.; Gray, K.; and Rose, E. “The experience of receiving a diagnosis and treatment of ADHD in adulthood: a qualitative study of clinically referred patients using interpretative phenomenological analysis.,” J. Atten. Disord., 2008, vol. 11, no. 4, pp. 493–503. [CrossRef]

- Pelletier, L. G. and Rocchi, M. “Organismic integration theory,” in The Oxford Handbook of Self-Determination Theory, R. M. Ryan, Ed., Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2023, pp. 53–83.

- Bozhilova, N. S.; Michelini, G.; Kuntsi, J.; and Asherson, P. “Mind wandering perspective on attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder,” Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev., 2018, vol. 92, no. July, pp. 464–476. [CrossRef]

- Vansteenkiste, M. and Ryan, R. M. “On psychological growth and vulnerability: Basic psychological need satisfaction and need frustration as a unifying principle,” J. Psychother. Integr., 2013, vol. 23, no. 3, pp. 263–280. [CrossRef]

- Zimmerman, M. E. “Heidegger, Buddhism and deep ecology,” in The Cambridge Companion to Heidegger, 2nd ed., New York, NY: Cambridge University Press, 2006, pp. 293–325.

- Heidegger, M. Being and time. Tübingen: Max Neimeyer Verlag, 1953.

- Merleau-Ponty, M. Phenomenology of perception (D.Landes, Trans.). Abington, Oxon: Routledge, 1945.

- Perls, F. S.; Hefferline, R.;and Goodman, P. Gestalt therapy: Excitement and growth in the human personality. Gouldsboro, ME: The Gestalt Journal Press, 1951. [CrossRef]

- Varela, F. J.; Thompson, E.; and Rosch, E. The embodied mind: Cognitive science and human experience. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1991. [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R. M. and Deci, E. L. “Approaching and avoiding self-determination: Comparing cybernetic and organismic paradigms of motivation,” in Perspectives on Behavioural Self-Regulation, R. S. Wyer Jr., Ed., East Sussex: Routledge, 1999, pp. 193–215.

- Friedlander, S. Schopferische Indifferenz. Munchen: Georg Muller, 1918.

- Amendt-Lyon, N. “How can a void be fertile? Implications of Friedlaender’s creative indifference for Gestalt therapy theory and practice,” Gestalt Rev., 2020, vol. 24, no. 2, p. 142. [CrossRef]

- Frambach, L. “The Weighty World of Nothingness: Salomo Friedlaender’s ‘Creative Indifference,’” Creat. Licens., no. 1994, pp. 113–127, 2003. [CrossRef]

- Perls, F. S. Ego, hunger and aggression: A revision of Freud’s theory and method. Gouldsboro, ME: Gestalt Journal Press, 1969.

- Assor, A.; Benita, M.; and Geifman, Y. “The authentic inner compass as an important motivational experience and structure: Antecedents and benefits.,” in The Oxford Handbook of Self-Determination Theory, R. M. Ryan, Ed., New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2023, pp. 363–386.

- Assor, A. “The striving to develop an authentic inner compass as a key component of adolescents’ need for autonomy: Parental antecedents and effects on identity, well-being, and resilience.,” in Autonomy in Adolescent Development: Toward conceptual clarity, Soenens, B. and Vansteenkiste, M. Ed., 2018, pp. 119–144,.

- Ryan, R. M. and Vansteenkiste, M. “Self-Determination theory: Metatheory, methods and meaning,” in The Oxford handbook of self-determination theory, R. M. Ryan, Ed., Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2023, pp. 1–30.

- Nind, M. “The practical wisdom of inclusive research,” Qual. Res., 2017, vol. 17, no. 3, pp. 278–288. [CrossRef]

- Grant, A. and Kara, H. “Considering the Autistic advantage in qualitative research: The strengths of Autistic researchers,” Contemp. Soc. Sci., 2021, vol. 16, no. 5, pp. 589–603. [CrossRef]

- Broido, E. M. “Making disability research useful (Practice brief),” J. Postsecond. Educ. Disabil., 2018, vol. 33, no. 3, pp. 275–281.

- Arstein-Kerslake, A.; Maker, Y.; Flynn, E.; Ward, O.; Bell, R.; and Degener, T. “Introducing a human rights-based disability research methodology,” Hum. Rights Law Rev., 2020, vol. 20, no. 3, pp. 412–432. [CrossRef]

- Mason, M. “Sample size and saturation in PhD studies using qualitative interviews,” Forum Qual. Sozialforsch., 2010, vol. 11, no. 3.

| Patient ID | Age | Gender | Race | Year of diagnosis | Subgroup |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 38 | Female | White British | 2020 | Combined |

| 3 | 21 | Female | White British | 2018 | Combined |

| 4 | 35 | Male | White British | 2011 | Inattentive |

| 6 | 20 | Female | White British | 2021 | Combined |

| 7 | 24 | Male | White British | 2009 | Inattentive |

| 8 | 20 | Male | Hispanic American | 2021 | Inattentive |

| 9 | 52 | Female | White British | 2019 | Inattentive |

| 10 | 28 | Male | White British | 2021 | Inattentive |

| 11 | 50 | Male | South American | 2016 | Inattentive |

| 12 | 42 | Female | White British | 2016 | Inattentive |

| 13 | 36 | Female | White British | 2013 | Combined |

| SDT Basic Psychological Needs | ||

| Autonomy | Competence | Relatedness |

|

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).