Submitted:

25 September 2024

Posted:

26 September 2024

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

“taking utmost account in energy planning, and in policy and investment decisions, of alternative cost-efficient energy efficiency measures to make energy demand and energy supply more efficient, in particular by means of cost-effective end-use energy savings, demand response initiatives and more efficient conversion, transmission and distribution of energy, whilst still achieving the objectives of those decisions” (EU, 2018b, p. 15).

“adopting a holistic approach, which takes into account the overall efficiency of the integrated energy system, security of supply and cost effectiveness and promotes the most efficient solutions for climate neutrality across the whole value chain, from energy production, network transport to final energy consumption, so that efficiencies are achieved in both primary energy consumption and final energy consumption. That approach should look at the system performance and dynamic use of energy, where demand-side resources and system flexibility are considered to be energy efficiency solutions” (EU, 2023, p. 4).

- Which problems and policy options were presented, by who and why? How were these problems and policy options framed??

- How did the policy window open?

- Which strategies were used by the policy entrepreneurs, and why were they successful?

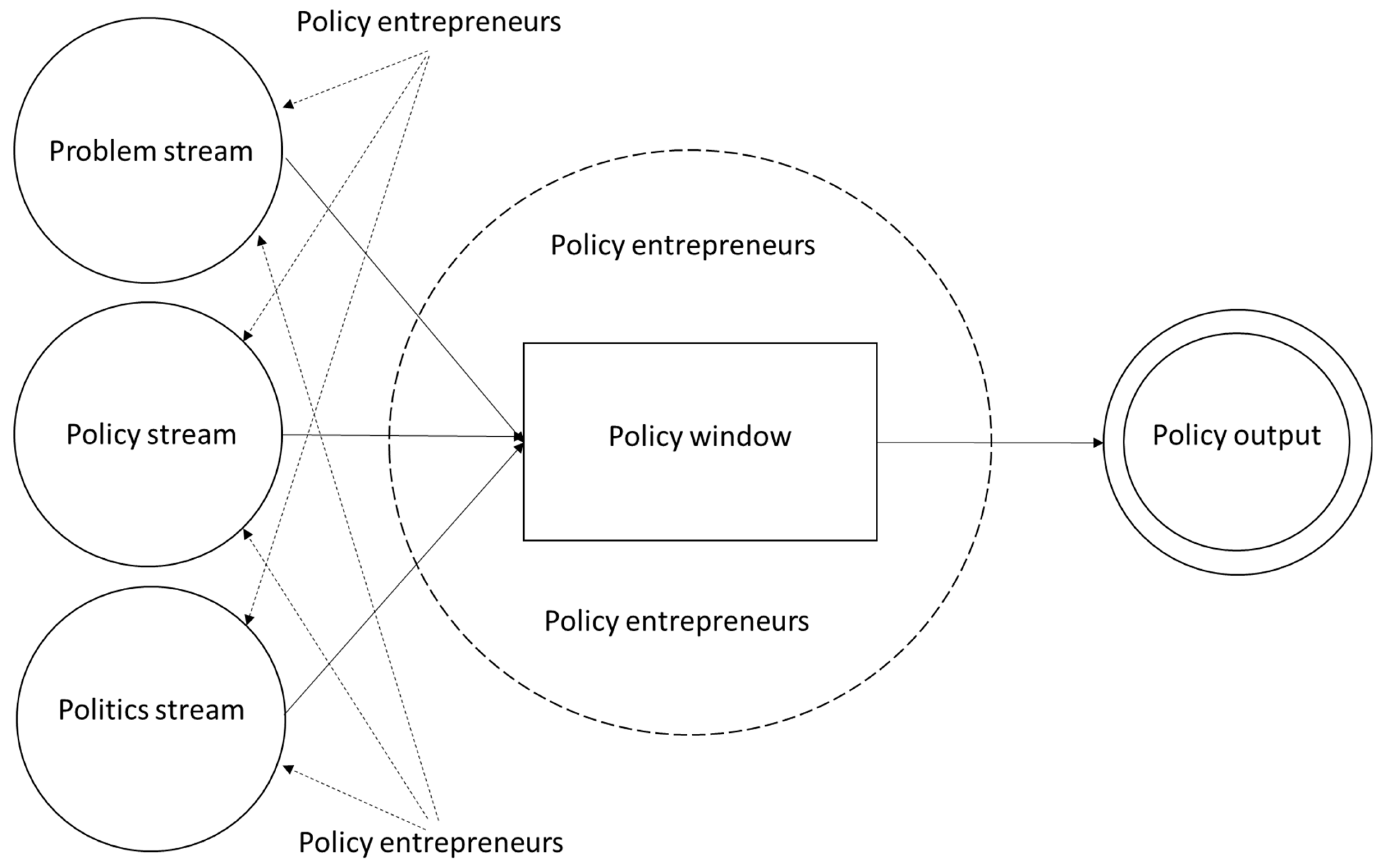

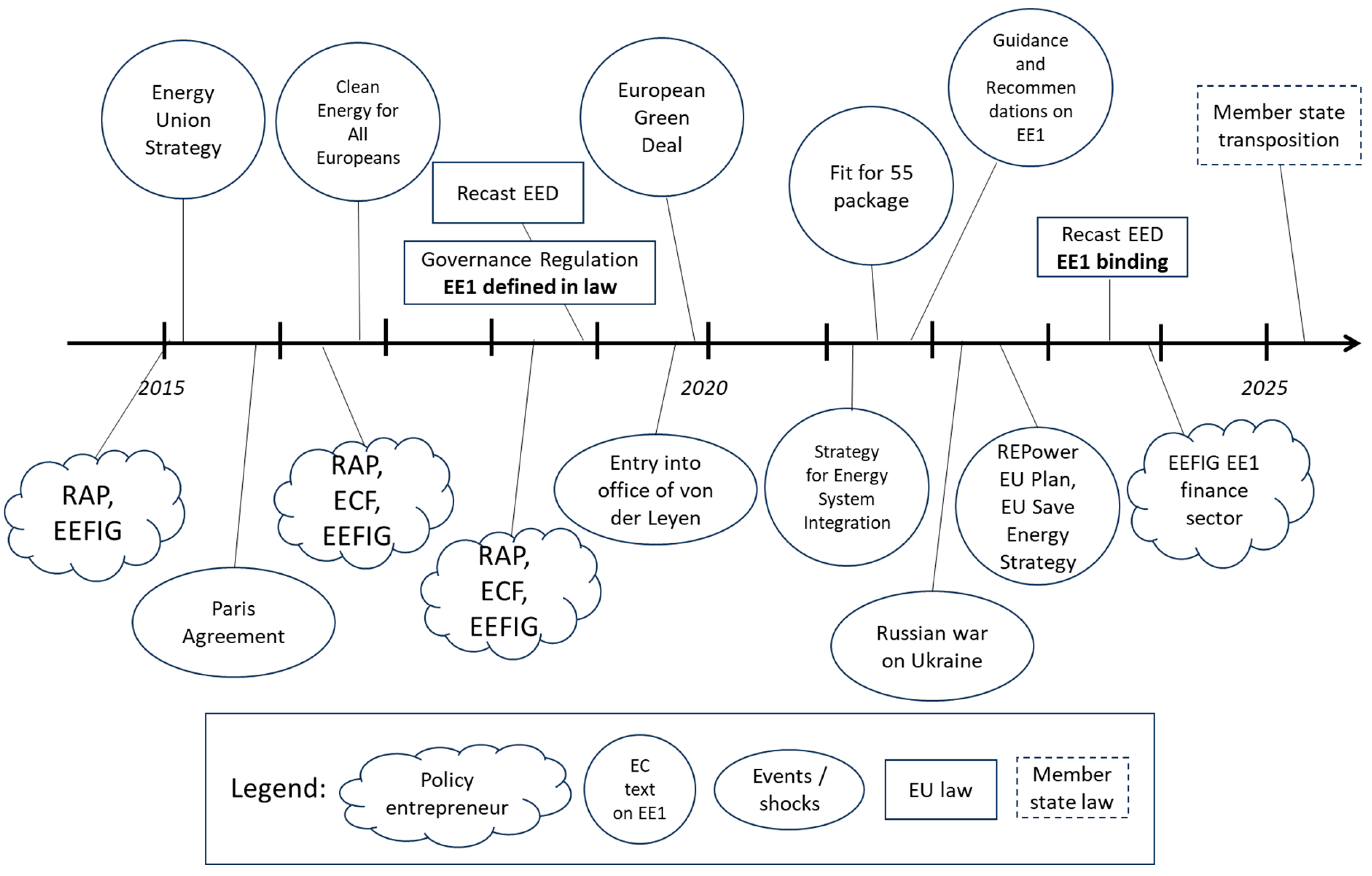

2. Theory and Previous Research

2.1. Multiple Streams Framework

2.2. Policy Entrepreneurs

- Structural entrepreneurship: acts aimed at overcoming structural barriers to enhancing governance influence by altering the distribution of formal authority and factual and scientific information; and

- Cultural-institutional entrepreneurship: acts aimed at altering or diffusing people’s perceptions, beliefs, norms and cognitive frameworks, worldviews, or institutional logics.

2.3. Previous Research on EE1 and Policy Entrepreneurs in EU Climate and Energy Policy

3. Method and Material

- One marker of significant resource investment (time or money),

- AND: at least one entrepreneurial goal,

- AND: at least one entrepreneurial strategy or characteristics,

- AND: at least one network partner.

- The European Commission,

- Regulatory Assistance Project (RAP)1,

- European Climate Foundation (ECF)2, and

- Energy Efficiency Financial Institutions Group (EEFIG)3

4. Results

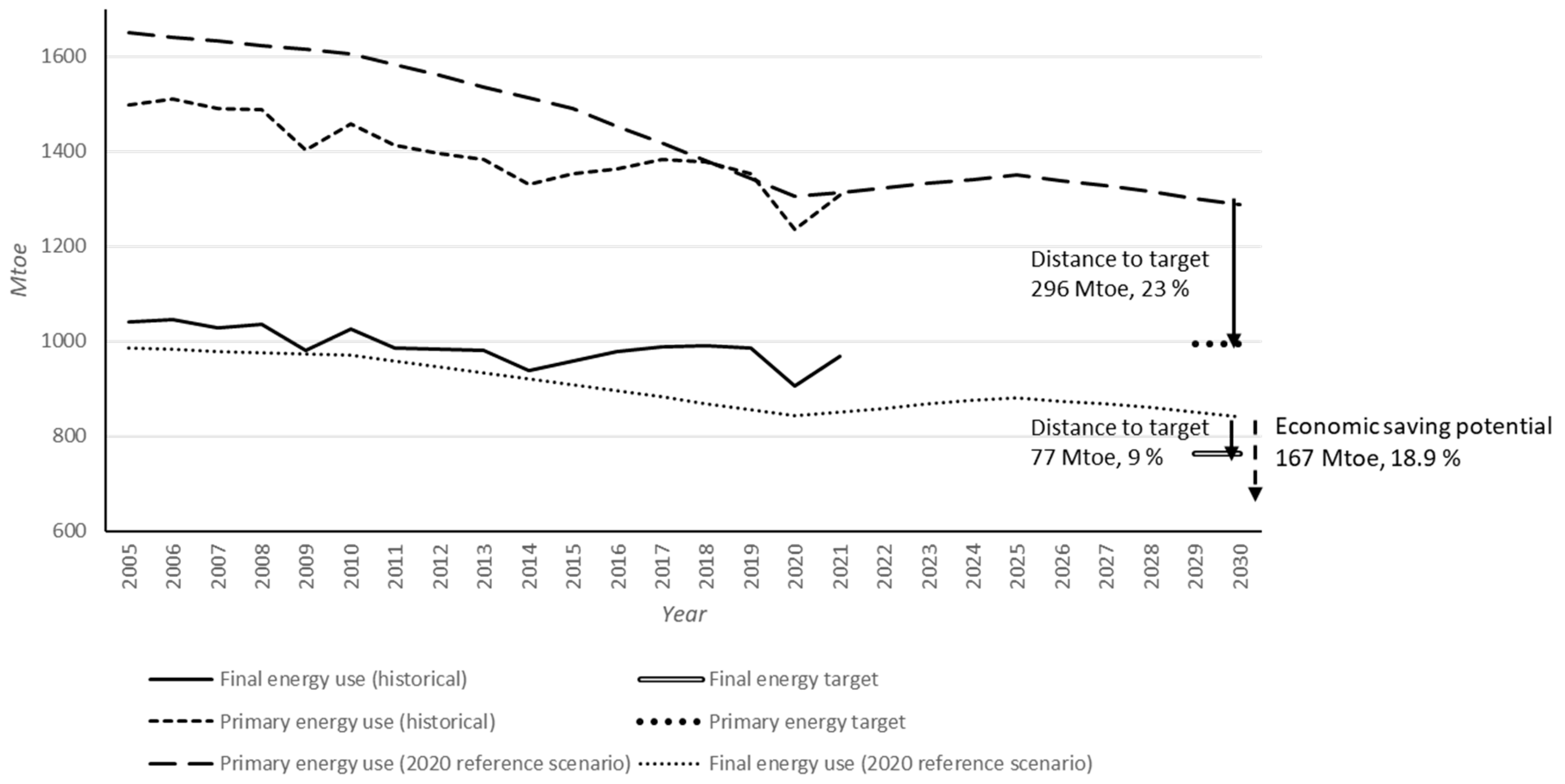

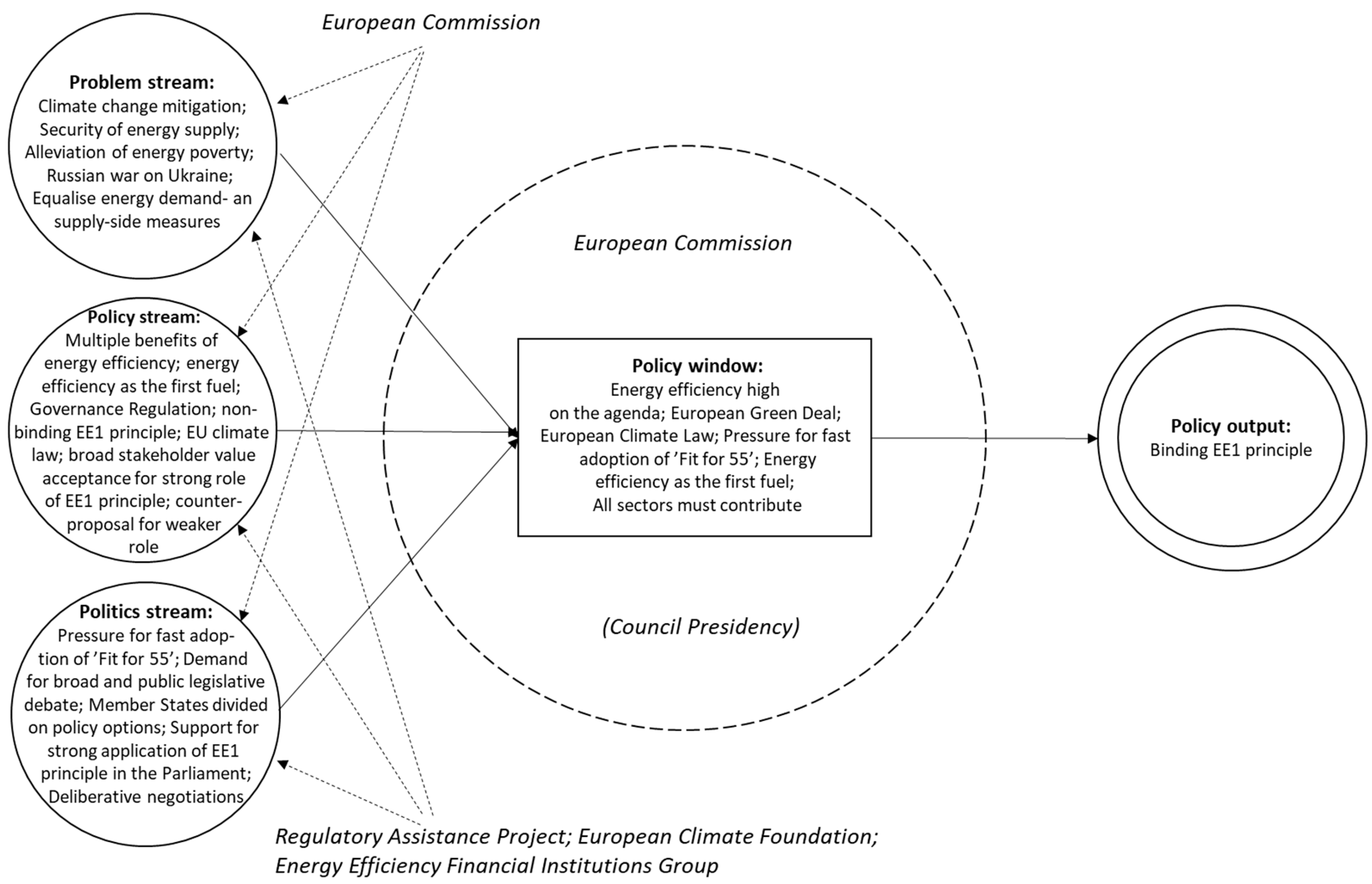

4.1. The Problem Stream

“Improving energy efficiency throughout the full energy chain, including energy generation, transmission, distribution and end-use, will benefit the environment, improve air quality and public health, reduce GHG emissions, improve energy security by reducing dependence on energy imports from outside the EU, cut energy costs for households and companies, help alleviate energy poverty, and lead to increased competitiveness, more jobs and increased economic activity throughout the economy, thus improving citizens’ quality of life”.

4.2. The Policy Stream

4.2.1. The Commission Proposal

“The energy efficiency first principle is an overarching principle that should be taken into account across all sectors, going beyond the energy system, at all levels, including in the financial sector. Energy efficiency solutions should be considered the first option in policy, planning and investment decisions when setting new rules for the supply side and other policy areas. The Commission should ensure that energy efficiency and demand-side response can compete on equal terms with generation capacity. Energy efficiency improvements need to be made whenever they are more cost-effective than equivalent supply-side solutions. This should help the Union exploit the multiple benefits of energy efficiency, particularly for citizens and businesses. Implementing energy efficiency improvement measures should also be a priority in alleviating energy poverty.”

4.2.2. Views of Interest Groups and Citizens

4.3. The politics Stream

“Given the higher climate target, Union action will supplement and reinforce national and local action towards increasing efforts in energy efficiency. The Governance Regulation already foresees the obligation for the [EC] to act in case of a lack of ambition by the [MSs] to reach the Union targets, thus de facto formally recognising the essential role of Union action in this context, and EU action is thus justified on grounds of subsidiarity in line with Article 191 of [TFEU]” (EC, 2021a, p. 10).

“The Energy Efficiency Directive essentially sets the overall energy efficiency objective but leaves the majority of actions to be taken to achieve this objective to the Member States. The application of the [EE1] principle leaves flexibility to the Member States” (EC, 2021a, p. 12).

4.3.1. Council Negotiations

4.3.2. European Parliament Negotiations

4.3.3. Trilogue Negotiations

5. Analysis and Discussion

5.1. Opening the Policy Window

5.2. Strategies and Success of Policy Entrepreneurs

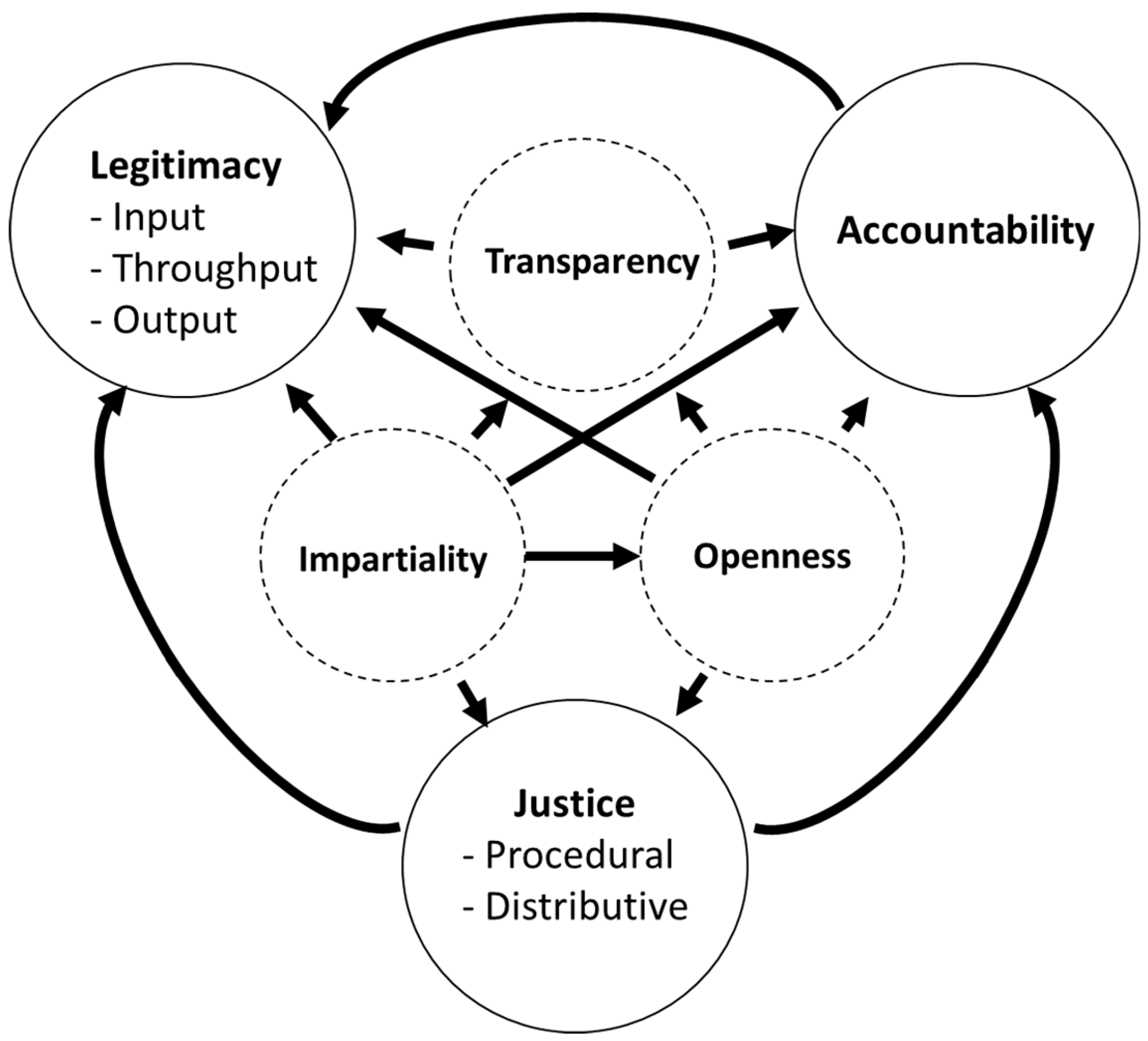

5.3. Ethics of Policy Entrepreneurs

6. Conclusions and Policy Implications

Funding

Acknowledgements

Abbreviations

| ACF | Advocacy Coalition Framework |

| CfES | Coalition for Energy Savings |

| EC | European Commission |

| ECF | European Climate Foundation |

| ECL | European Climate Law |

| EE1 | Energy Efficiency First Principle |

| EED | Energy Efficiency Directive |

| EEFIG | Energy Efficiency Financial Institutions Group |

| EGD | European Green Deal |

| ENVI | EP’s Committee on the Environment, Public Health and Food Safety |

| EP | European Parliament |

| EPP | European Peoples Party |

| EU-ASE | European Alliance to Save Energy |

| Greens/EFA | Greens/European Free Alliance (green parties) |

| IEA | International Energy Agency |

| IG | Interest Group |

| IPCC | Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change |

| ITRE | EP’s Committee on Industry, Research and Energy |

| MS | Member State |

| MSF | Multiple Streams Framework |

| NGO | Nongovernmental Organisation |

| RAP | Regulatory Assistance Project |

| S&D | Progressive Alliance of Socialists and Democrats (social democrats) |

References

- Ackrill, R.; Kay, A. Multiple streams in EU policy-making: the case of the 2005 sugar reform. Journal of European Public Policy 2011, 18, 72–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ackrill, R.; Kay, A.; Zahariadis, N. Ambiguity multiple streams, and EU policy. Journal of European Public Policy 2013, 20, 871–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, S.E.; DeLeo, R.A.; Taylor, K. Policy entrepreneurs legislators, and agenda setting: Information and influence. Policy Studies Journal 2020, 48, 587–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnold, G. Does entrepreneurship work? Understanding what policy entrepreneurs do and whether it matters. Policy Studies Journal 2021, 49, 968–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnold, G. A threat-centered theory of policy entrepreneurship. Policy Science 2022, 55, 23–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnold, G.; Nguyen Long, L.A.; Gottlieb, M. Social networks and policy entrepreneurship: How relationships shape municipal decision making about high-volume hydraulic fracturing. Policy Studies Journal 2017, 45, 414–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnold, G.; Klasic, M.; Wu, C.; Schomburg, M.; York, A. Finding distinguishing, and understanding overlooked policy entrepreneurs. Policy Sciences 2023, 56, 657–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aviram, N.F.; Cohen, N.; Beeri, I. Wind(ow) of change: A systematic review of policy entrepreneur characteristics and strategies. Policy Studies Journal 2020, 48, 612–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bache, I. Measuring quality of life for public policy: an idea whose time has come? Agenda-setting dynamics in the European Union. Journal of European Public Policy 2013, 20, 21–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakir, C. Policy entrepreneurship and institutional change: Multilevel governance of central banking reform. Governance 2009, 22, 571–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakir, C.; Jarvis, D.S.L. Contextualising the context in policy entrepreneurship and institutional change. Policy & Society 2017, 36, 465–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, M.W.; Becker, S. The unexpected winner of the crisis: The European Commission’s strengthened role in economic governance. Journal of European Integration 2014, 36, 213–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayer, E. Efficiency First: Key points for the Energy Union Communication. Brussels: Regulatory Assistance Project 2015. https://www.raponline.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/rap-efficiencyfirstmemo-2015-feb-12.pdf.

- Bayer, E. Energy Efficiency First: A Key Principle for Energy Union Governance. Brussels: Regulatory Assistance Project 2018. https://www.raponline.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/rap-bayer-key-principle-for-energy-union-governance-2018-april-17.pdf.

- Becker, P. The reform of European cohesion policy or how to couple the streams successfully. Journal of European Integration 2019, 41, 147–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, S. Supranational entrepreneurship through the administrative backdoor: The Commission the Green Deal and the CAP 2023–2027. JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies 2024, 62, 13522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Béland, D.; Cox, R.H. Ideas as coalition magnets: coalition building policy entrepreneurs, and power relations. Journal of European Public Policy 2016, 23, 428–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binderkrantz, A.S.; Krøjer, S. Customising strategy: Policy goals and interest group strategies. Interest Groups & Advocacy 2012, 1, 115–138. [Google Scholar]

- Bitonti, A. The role of lobbying in modern democracy: A theoretical framework. In: Bitonti, A 2017, & Harris, P. (eds.), Lobbying in Europe: Public Affairs and the Lobbying Industry in 28 EU Countries, London: Palgrave Macmillan; 17-30.

- Bitonti, A.; Harris, P. (2017) Lobbying in Europe: Public Affairs and the Lobbying Industry in 28 EU Countries, London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Bitonti, A.; Mariotti, C. Beyond transparency: The principles of lobbying regulation and the perspective of professional lobbying consultancies. Italian Political Science Review 2023, 53, 143–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, J. Constructing and contesting legitimacy and accountability in polycentric regulatory regimes. Regulation & Governance 2008, 2, 137–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boasson, E.L.; Huitema, D. Climate governance entrepreneurship: Emerging findings and a new research agenda. Environment and Planning C: Politics and Space 2017, 35, 1343–1361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bocquillon, P. (De)Constructing coherence? Strategic entrepreneurs. policy frames and the integration of climate and energy policies in the European Union, Environmental Policy and Governance 2018, 28, 339–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boscarino, J.E. Surfing for problems: Advocacy group strategy in U.S. forestry policy. Policy Studies Journal 2009, 37, 415–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandsma, G.J. Codecision after Lisbon: The politics of informal trilogues in European Union lawmaking. European Union Politics 2015, 16, 300–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brouwer, S. (2015) Policy Entrepreneurs in Water Governance, Cham: Springer.

- Brouwer, S.; Huitema, D. Policy entrepreneurs and strategies for change. Regional Environmental Change 2018, 18, 1259–1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bürgin, A. (2023) The European Commission: A climate policy entrepreneur, In: Rayner, T.; Szulecki, K.; Jordan, A.J.; Oberthür, S. (eds.), Handbook on European Union Climate Change Policy and Politics, Cheltenham: Edward Elgar; 23-37.

- Cairney, P. Standing on the shoulders of giants: How do we combine the insights of multiple theories in public policy studies. Policy Studies Journal 2013, 41, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cairney, P. (2023) The politics of policy analysis: theoretical insights on real world problems, Journal of European Public Policy, 30. [CrossRef]

- Caramani, D. Will vs. reason: The populist and technocratic forms of political representation and their critique to party government. Americal Political Science Review 2017, 111, 54–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassegård, C.; Thörn, H. (2017) Climate justice, equity and movement mobilization, In: Cassegård, C.; Soneryd, L.; Thörn, H.; Wettergren, Å. (eds.), Climate Action in a Globalizing World, London: Routledge; 33-56.

- CfES (2021) Consultation on the Review and the Revision of Directive 2012/27/EU on Energy Efficiency, Brussels: Coalition for Energy Savings. https://energycoalition.eu/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/20210209_EED-public-consultation-feedback-CfES-2.pdf.

- CfES (2022) Coalition for Energy Savings: Feedback to EED recast proposal, Brussels: Coalition for Energy Savings. https://energycoalition.eu/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/20211123_Coalition-feedback-to-Commission-EED-recast-proposal-final.pdf.

- Cini, M.; Borragán, N.P.S. (2022) European Union Politics, 7th ed., Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Chlechowitz, M.; Reuter, M.; Eichhammer, W. How first comes energy efficiency? Assessing the energy efficiency first principle in the EU using a comprehensive indicator-based approach. Energy Efficiency 2022, 15, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. (1996) Procedure and substance in deliberative democracy. In: Benhabib, S. (ed.), Democracy and Difference: Contesting the Boundaries of the Political, Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press; 95-119.

- Considine, M.; Lewis, J.; Alexander, D. (2009) Networks, Innovation and Public Policy: Politicians, Bureaucrats and the Pathways to Change Inside Government, New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Copeland, P. The Juncker Commission as a politicising bricoleur and the renewed momentum in Social Europe. JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies 2022, 60, 1629–1644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Copeland, P.; James, S. Policy windows ambiguity and Commission entrepreneurship: Explaining the relaunch of the European Union’s economic reform agenda. Journal of European Public Policy 2014, 21, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Council (2022) Council general approach on the proposal for a directive of the European Parliament and of the Council on energy efficiency (recast), 10697/22 2021/0203(COD), Brussels: Council of the European Union. https://data.consilium.europa.eu/doc/document/ST-10697-2022-INIT/en/pdf.

- Cram, L. The European commission as a multi-organization: Social policy and IT policy in the EU. Journal of European Public Policy 1994, 1, 195–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crespy, A.; Menz, G. Commission entrepreneurship and the debasing of ‘Social Europe’ before and after the Eurocrisis. JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies 2015, 53, 753–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crespy, A.; Munta, M. Lost in transition? Social justice and the politics of the EU green transition. Transfer: European Review of Labour and Research 2023, 29, 235–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crow, D.A. Policy entrepreneurs issue experts, and water rights policy change in Colorado. Review of Policy Research 2010, 27, 299–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahl, R.A. (1961) Who Governs? Democracy and Power in an American City, New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

- Dewulf, A.; Bouwen, R. Issue framing in conversations for change: Discursive interaction strategies for ‘doing differences’. Journal of Applied Behavioral Science 2012, 48, 168–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dreger, J. (2014) The European Commission’s Energy and Climate Policy. A Climate for Expertise? Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Dunlop, T. Energy efficiency: The evolution of a motherhood concept. Social Studies of Science 2022, 52, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dunlop, T.; Völker, T. The politics of measurement and the case of energy efficiency policy in the European Union. Energy Research & Social Science 2023, 96, 102918. [Google Scholar]

- Dupont, C. Defusing contested authority: EU energy efficiency policymaking. Journal of European Integration 2020, 42, 95–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dupont, C.; Moore, B.; Boasson, E. L. Gravey, V.; Jordan, A.; Kivimaa, P.; Kulovesi, K.; Kuzemko, C.; Oberthür, S.; Panchuk, D.; Rosamond, J.; Torney, D.; Tosun, J.; & von Homeyer, I. (2023). Three decades of EU climate policy: Racing toward climate neutrality? WIREs Climate Change, 15, e863. [CrossRef]

- EC (2015) Energy Union package: A Framework Strategy for a Resilient Energy Union with a Forward-Looking Climate Change Policy, COM/2015/080 final. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/resource.html?uri=cellar:1bd46c90-bdd4-11e4-bbe1-01aa75ed71a1.0001.03/DOC_1&format=PDF.

- EC (2016) Clean energy for all Europeans package, Brussels: European Commmission https://energy.ec.europa.eu/topics/energy-strategy/clean-energy-all-europeans-package_en.

- EC (2019) The European Green Deal, COM(2019) 640 final, Brussels: European Commission. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:52019DC0640&from=EN.

- EC (2020a) Analysis to support the implementation of the energy efficiency first principle in decision-making, Brussels: European Commission. https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/b9cc0d80-c1f8-11eb-a925-01aa75ed71a1/language-en/format-PDF/source-292832016.

- EC (2020b) Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions: Powering a climate-neutral economy: An EU Strategy for Energy System Integration¸COM(2020) 299 final. Brussels: European Commission. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:52020DC0299t.

- EC (2020c) Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions: Stepping up Europe’s 2030 climate ambition. Investing in a climate-neutral future for the benefit of our people, COM(2020) 562 final, Brussels: European Commission. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:52020DC0562&from=en.

- EC (2020d) EU reference scenario 2020. Energy, transport and GHG emissions: trends to 2050, Brussels: European Commission. https://energy.ec.europa.eu/data-and-analysis/energy-modelling/eu-reference-scenario-2020_en.

- EC (2021a) Proposal for a directive of the European Parliament and the Council on energy efficiency (recast), COM(2021) 558 final, Brussels: European Commission. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:52021PC0558.

- EC (2021b) Commission Staff Working Document: Impact Assessment, Accompanying the document Proposal for a Directive of the European Parliament and of the Council amending Directive 2012/27/EU on Energy Efficiency, SWD/2016/0405 final–2016/0376 (COD), Brussels: European Commission. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A52016SC0405.

- EC (2021c) Fit for 55: Delivering on the proposals, Brussels: European Commission. https://commission.europa.eu/strategy-and-policy/priorities-2019-2024/european-green-deal/delivering-european-green-deal/fit-55-delivering-proposals_en.

- EC (2021d) EU energy efficiency directive (EED) – evaluation and review, Brussels: European Commission. https://ec.europa.eu/info/law/better-regulation/have-your-say/initiatives/12552-EU-energy-efficiency-directive-EED-evaluation-and-review/public-consultation_en.

- EC (2021e) Technical assistance services to assess the energy savings potentials at national and European level: Summary of EU results, Brussels: European Commission. https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/b259632c-f8ba-11eb-b520-01aa75ed71a1/language-en.

- EC (2021f) Commission recommendation of 28.9.2021 on Energy Efficiency First: from principles to practice. Guidelines and examples for its implementation in decision-making in the energy sector and beyond, C(2021) 7014 final, Brussels: European Commission. https://ec.europa.eu/energy/sites/default/files/eef_recommendation_ref_tbc.pdf.

- EC (2021g) Annex to the Commission recommendation on Energy Efficiency First: from principles to practice. Guidelines and examples for its implementation in decision-making in the energy sector and beyond, C(2021) 7014 final, Brussels: European Commission. https://ec.europa.eu/energy/sites/default/files/eef_guidelines_ref_tbc.pdf.

- EC (2021h) Regulatory scrutiny board: Proposal for a directive of the European Parliament and of the Council on energy efficiency (recast), SEC(2021) 558, Brussels: European Commission. https://ec.europa.eu/.

- EC (2022a) Update on energy price assumptions on economic potential savings: Final Report, Brussels: European Commission. https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/70520469-a5da-11ed-b508-01aa75ed71a1.

- EC (2022b) Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the European Council, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions – REPowerEU Plan, COM(2022) 230 final, Brussels: European Commission. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/resource.html?uri=cellar:fc930f14-d7ae-11ec-a95f-01aa75ed71a1.0001.02/DOC_1&format=PDF.

- EC (2022c) Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the European Council, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committeee of the Regions – EU ‘Save Energy’, COM(2022) 240 final, Brussels: European Commission. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:52022DC0240&from=EN.

- ECF (2016) Efficiency First: A new paradigm for the European energy system: Driving competitiveness, energy security and decarbonisation through increased energy productivity, Brussels: European Climate Foundation. https://www.raponline.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/ecf-efficiency-first-new-paradigm-eruopean-energy-system-june-2016.pdf.

- Eckersley, R. Ecological democracy and the rise and decline of liberal democracy: Looking back looking forward. Environmental Politics 2019, 29, 214–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edler, J.; James, A.D. Understanding the emergence of new science and technology policies: Policy entrepreneurship agenda setting and the development of the European Framework Programme. Research Policy 2015, 44, 1252–1265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EEFIG (2015) Energy Efficiency – The First Fuel for the EU Economy, Brussels: Energy Efficiency Financial Institutions Group. https://ec.europa.eu/energy/sites/ener/files/documents/Final%20Report%20EEFIG%20v%209.1%2024022015%20clean%20FINAL%20sent.pdf.

- EEFIG (2023) Applying the Energy Efficiency First principle in sustainable finance: Final report, Brussels: Energy Efficiency Financial Institutions Group. https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/20330c99-7df5-11ee-99ba-01aa75ed71a1/language-en?WT.mc_id=Searchresult&WT.ria_c=37085&WT.ria_f=3608&WT.ria_ev=search&WT.URL=https%3A%2F%2Fenergy.ec.europa.eu%2F.

- Elgström, O. (2003) The honest broker? In: Elgström, O. (ed.), European Union Council Presidencies: A comparative analysis, London: Routledge; 39-56. [CrossRef]

- EP (2022) Amendments adopted by the European Parliament on 14 September 2022 on the proposal for a directive of the European Parliament and of the Council on energy efficiency (recast) (COM(2021)0558 – C9-0330/2021 – 2021/0203(COD), Brussels: European Parliament. https://www.europarl.europa.eu/doceo/document/TA-9-2022-0315_EN.html#top.

- EU (2012a) Directive 2012/27/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 25 October 2012 on energy efficiency, amending Directives 2009/125/EC and 2010/30/EU and repealing Directives 2004/8/EC and 2006/32/EC, Official Journal of the European Union, OJ L 315/1 14.11.2012. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=OJ:L:2012:315:FULL&from=EN.

- EU (2012b) Consolidated version of Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union, Official Journal of the European Union, OJ C 328/210 26.10.2012. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=CELEX:12012E/TXT:en:PDF.

- EU (2018a) Directive (EU) 2018/2002 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 11 December 2018 amending Directive 2012/27/EU on energy efficiency, Official Journal of the European Union, OJ L 328/210 21.12.2018. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32018L2002&from=EN.

- EU (2018b) Regulation (EU) 2018/1999 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 11 December 2018 on the Governance of the Energy Union and Climate Action, Official Journal of the European Union, OJ L 328/52 21.12.2018. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32018R1999&from=EN.

- EU (2021) Regulation (EU) 2021/1119 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 30 June 2021 establishing the framework for achieving climate neutrality and amending Regulations (EC) No 401/2009 and (EU) 2018/1999 (‘European Climate Law’), Official Journal of the European Union, OJ L 243/1 9.7.2021. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32021R1119&from=EN.

- EU (2023) Directive (EU) 2023/1791 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 13 September 2023 on energy efficiency and amending Regulation (EU) 2023/955 (recast) (EED), Official Journal of the European Union, OJ L 231/1 20.9.2023. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32023L1791.

- Eurobarometer (2024) Attitudes of Europeans towards the Environment, Special Eurobarometer 550, Brussels: European Commission. https://europa.eu/eurobarometer/api/deliverable/download/file?deliverableId=92303.

- European Environment Agency (2023) Primary and final energy consumption in Europe, Copenhagen: European Environment Agency. https://www.eea.europa.eu/ims/primary-and-final-energy-consumption.

- Eurostat (2023) Energy indicators: Energy efficiency, Brussels: European Commission. https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/nrg_ind_eff/default/bar?lang=en.

- Fawcett, T.; Killip, G. Rethinking energy efficiency in European policy: Practitioners’ use of ‘multiple benefits’ arguments. Journal of Cleaner Production 2019, 210, 1171–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldman, M.S. (1989) Order Without Design: Information Production and Policy Making, Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

- Filipović, S.; Lior, N.; Radovanović, M. The green deal—Just transition and sustainable development goals Nexus Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews. 168, 112759 2022. [CrossRef]

- Fligstein, N. Social skill and the theory of fields. Sociological Theory 2001, 19, 105–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, E. (2020) The impact of the Lisbon Treaty on the EU’s ‘competence creep’, North East Law Review, 7, 8-14. https://heinonline.org/HOL/LandingPage?handle=hein.journals/neastlr7&div=8&id=&page=.

- Fuglsang, N. (2022) Draft report on the proposal for a directive of the European Parliament and of the Council on energy efficiency (recast), COM(2021)0558 – C9-0330/2021 – 2021/0203(COD), Brussels: European Parliament. https://www.europarl.europa.eu/doceo/document/ITRE-PR-703281_EN.pdf.

- Gabehart, K.M.; Nam, A.; Weible, C.M. Lessons from the advocacy coalition framework for climate change policy and politics. Climate Action 2022, 1, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garben, S. Competence creep revisited. JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies 2019, 57, 205–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garben, S. From sneaking to striding: Combatting competence creep and consolidating the EU legislative process. European Law Journal 2022, 26, 429–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, J.F. Policy entrepreneurship in climate governance: Toward a comparative approach. Environment and Planning C: Politics and Space 2017, 35, 1471–1482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunn, A. (2017) Policy entrepreneurs and policy formulation, In: Howlett, M.; Mukherjee, I.; eds., Handbook of Policy Formulation, Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar; 265-284.

- Gutmann, A.; Thompson, D. (1996) Democracy and Disagreement, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Heikkila, T.; Cairney, P. (2018) Comparison of theories of the policy process, In: Weible, C.M.; Sabatier, P.A. (eds.), Theories of the Policy Process, 4th ed. Routledge, New York, NY, pp. 301-327.

- Heldt, E.C.; Müller, T. Bringing independence and accountability together: Mission impossible for the European Central Bank? Journal of European Integration. 44, 837-853 2022. [CrossRef]

- Herranz-Surralés, A. (2019) Energy policy and European Union politics, Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Politics, Oxford: Oxford University Press. [CrossRef]

- Herranz-Surralés, A.; Solorio, I. (2022) Energy and climate crises, In: Graziano, P.R.; Tosun, J.; editors, Elgar Encyclopedia of European Union Public Policy, Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar, 377-388.

- Herweg, N. Explaining European agenda-setting using the multiple streams framework: the case of European natural gas regulation. Policy Sciences 2016, 49, 13–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herweg, N. (2017) European Union Policy Making, The regulatory shift in the natural gas market policy, Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Herweg, N.; Huß, C.; Zohlnhöfer, R. Straightening the three streams: Theorising extensions of the multiple streams framework. European Journal of Political Research 2015, 54, 435–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herweg, N.; Zahariadis, N.; Zohlnhöfer, R. (2018) The multiple streams framework: Foundations, refinements, and empirical, In: C.M.; Sabatier, P.A.; eds., Theories of the Policy Process, 4th ed, New York, NY: Routledge; 17-53.

- Herweg, N.; Zohlnhöfer, R. (2022) Analysing EU policy processes: applying the multiple streams framework, In: Graziano, P.R.; Tosun, J.; editors, Elgar Encyclopedia of European Union Public Policy, Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar, 485-494.

- Herweg, N.; Zahariadis, N.; Zohlnhöfer, R. (2023) The multiple streams framework: Foundations, refinements, and empirical applications, In: Weible, C.M.; ed., Theories of the Policy Process, 5th ed, New York, NY: Routledge; 29-64.

- Hix, S. (2007) The European Union as a polity (I), In: Joergensen, K.; Pollack, M.; Rosamond, B.; eds., The Sage Handbook of European Union Politics, London: Sage; 141-158.

- Hutchinson, L. (2019) ‘Europe’s man on the moon moment’: Von der Leyen unveils EU Green Deal, The Parliament, 11 December 2019. https://www.theparliamentmagazine.eu/news/article/europes-man-on-the-moon-moment-von-der-leyen-unveils-eu-green-deal.

- (2019) Multiple Benefits of Energy Efficiency: From “Hidden Fuel” to “First Fuel”, Paris: International Energy Agency. https://www.iea.org/reports/multiple-benefits-of-energy-efficiency.

- IEA (2021) How Energy Efficiency Will Power Net Zero Climate Goals, Paris: International Energy Agency. https://www.iea.org/commentaries/how-energy-efficiency-will-power-net-zero-climate-goals.

- IPCC (2023) Climate Change 2023: Synthesis Report, Geneva, Switzerland: Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. [CrossRef]

- Jayachandran, M.; Gatla, R.K.; Rao, K.P.; Rao, G.S.; Mohammed, S.; Milyani, A.H.; Azhari, A.A.; Kalaiarasy, C.; Geetha, S. (2022) Challenges in achieving sustainable development goal 7: Affordable and clean energy in light of nascent technologies, Sustainable Energy Technologies and Assessment, 53(C), 102692. [CrossRef]

- Jordan, A.; Huitema, D. Policy innovation in a changing climate: Sources patterns and effects. Global Environmental Change 2014, 29, 387–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kastner, L. ‘Much ado about nothing? ’ Transnational civil society. consumer protection and financial regulatory reform. Review of International Political Economy 2014, 21, 1313–1345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerr, N.; Gouldson, A.; Barrett, J. The rationale for energy efficiency policy: Assessing the recognition of the multiple benefits of energy efficiency retrofit policy. Energy Policy 2017, 106, 212–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kettner, C.; Kletzan-Slamanig, D. Is there climate policy integration in European Union energy efficiency and renewable energy policies? Yes. no, maybe. Environmental Policy and Governance 2020, 30, 141–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, L.A. Deliberation legitimacy, and multilateral democracy. Governance 2003, 16, 23–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kingdon, J. (1984) Agendas, Alternatives and Public Policies, New York, NY: Harper Collins.

- Kingdon, J.W. (2002) Agendas, Alternatives and Public Policies, 2nd ed., New York, NY: Longman.

- Knaggård, Å. (2015). The multiple streams framework and the problem broker, European Journal of Political Research, 54, 450-465. [CrossRef]

- Knoop, K.; Lechtenböhmer, S. The potential for energy efficiency in the EU Member States – A comparison of studies. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2017, 68, 1097–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreienkamp, J.; Pegram, T.; Coen, D. Explaining transformative change in EU climate policy: multilevel problems policies, and politics. Journal of European Integration 2022, 44, 731–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuzemko, C.; Blondeel, M.; Dupont, C.; Brisbois, M.C. Russia’s war on Ukraine European energy policy responses & implications for sustainable transformations. Energy Research & Social Science 2023, 100, 102842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lafferty, W. M.; Ruud, A. (2009) Promoting Sustainable Electricity in Europe: Challenging the path dependence of dominant energy systems, Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

- Mackenzie, C. Policy entrepreneurship in Australia: A conceptual review of application. Australian Journal of Political Science 2010, 39, 367–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maltby, T. European Union energy policy integration: A case of European Commission policy entrepreneurship and increasing supranationalism. Energy Policy 2013, 55, 435–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandel, T.; Pató, Z.; Broc. , J.S.; Eichhammer, W. Conceptualising the energy efficiency first principle: insights from theory and practice. Energy Efficiency 2022, 15, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazey, S.; Richardson, J. (2006) Interest groups and EU policy-making: Organisational logic and venue shopping, In: Richardson, J.; ed., European Union: Power and Policy-Making, 3rd ed., New York, NY: Routledge; 247-267.

- Meijerink, S.; Huitema, D. Policy entrepreneurs and change strategies: Lessons from sixteen case studies of water transitions around the world. Ecology and Society 2010, 15, 21–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minto, R.; Mergaert, L. Gender mainstreaming and evaluation in the EU: Comparative perspectives from feminist institutionalism. International Feminist Journal of Politics 2018, 20, 204–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mintrom, M. Policy entrepreneurs and the diffusion of innovation. American Journal of Political Science 1997, 41, 738–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mintrom, M. (2000) Policy Entrepreneurs and School Choice, Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press.

- Mintrom, M. (2019a) Policy Entrepreneurs and Dynamic Change, New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Mintrom, M. (2020) Policy Entrepreneurs and Dynamic Change, Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Mintrom, M.; Vergari, S. Advocacy coalitions policy entrepreneurs, and policy change. Policy Studies Journal 1996, 24, 420–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mintrom, M.; Norman, P. Policy entrepreneurship and policy change. Policy Studies Journal 2009, 37, 649–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mintrom, M.; Luetjens, J. Policy entrepreneurs and problem framing: The case of climate change. Environment and Planning C: Politics and Space 2017, 35, 1362–1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mollona, E.; Faldetta, G. Ethics in corporate political action: Can lobbying be just? Journal of Management and Governance. 26, 1245-1276 2022. [CrossRef]

- Moravcsik, A. A new statecraft? Supranational entrepreneurs and international cooperation. International Organisation 1999, 53, 267–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neyer, J. Justice not democracy: Legitimacy in the European Union. JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies 2010, 48, 903–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olabi, A.G.; Abdelkareem, M.A. Renewable energy and climate change. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2022, 158, 112111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmer, J.R. How do policy entrepreneurs influence policy change? Framing and boundary work in EU transport biofuels policy. Environmental Politics 2015, 24, 270–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pató, Z.; Mandel, T. Energy Efficiency First in the power sector: incentivising consumers and network companies. Energy Efficiency 2022, 15, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petridou, E. (2017) Political Entrepreneurship in Swedish: Towards a (Re)theorisation of Entrepreneurial Agency, Doctoral dissertation, Östersund, SE: Mid-Sweden University. http://miun.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:1057901/FULLTEXT02.pdf.

- Petridou, E.; Mintrom, M. A research agenda for the study of policy entrepreneurs. Policy Studies Journal 2021, 49, 943–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pickering, J.; Bäckstrand, K.; Schlosberg, D. Between environmental and ecological democracy: Theory and practice at the democracy-environment nexus. Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning 2020, 22, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pircher, B. The Council of the EU in times of economic crisis: A policy entrepreneur for the internal market. Journal of Contemporary European Research 2020, 16, 65–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- RAP (2016) Governance for Efficiency First: “Plan, finance, and deliver”: Ten near-term actions the European Commission should take to make Efficiency First a reality, Brussels: Regulatory Assistance Project/European Climate Foundation. https://www.raponline.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/ecf-governance-efficiency-first-plan-finance-deliver-2016.pdf.

- Radaelli, C.M. Measuring policy learning: regulatory impact assessment in Europe. Journal of European Public Policy, 1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reh, C.; Héritier, A.; Bressanelli, E.; Koop, C. The informal politics of legislation: Explaining secluded decision making in the European Union. Comparative Political Studies 2013, 46, 1112–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ringel, M.; Bruch, N.; Knodt, M. Is clean energy contested? Exploring which issues matter to stakeholders in the European Green Deal. Energy Research & Social Science 2021, 77, 102083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, N.; King, P.J. Policy entrepreneurs: Their activity structure and function in the policy process. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 1991, 1, 147–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roederer-Rynning, C. Passage to bicameralism: Lisbon’s ordinary legislative procedure at ten. Comparative European Politics 2019, 17, 957–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roederer-Rynning, C.; Greenwood, J. Black boxes and open secrets: trilogues as ‘politicised diplomacy’. West European Politics 2021, 44, 485–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenow, J.; Bayer, E.; Rososińska, B.; Genard, Q.; Toporek, M. (2016) Efficiency first: From principle to practice. Real world examples from across Europe, Brussels: Regulatory Assistance Project. https://www.raponline.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/efficiency-first-principle-practice-2016-november.pdf.

- Rosenow, J.; Cowart, R.; Bayer, E.; & Fabbri, M. Assessing the European Union’s energy efficiency policy: Will the winter package deliver on ‘Efficiency First’? Energy Research & Social Science. 26, 72-79 2017. [CrossRef]

- Sabatier, P.A. An advocacy coalition framework of policy change and the role of policy-oriented learning therein. Policy Sciences 1988, 21, 129–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabatier, P.A.; Jenkins-Smith, H. (1999) The advocacy coalition framework, In: Sabatier, P.A. (ed.), Theories of the Policy Process, Boulder, CO: Westview Press; 117-168.

- Schlosberg, D. (1999) Environmental Justice and the New Pluralism: The Challenge of Difference for Environmentalism. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Schneider, M.; Teske, P.; Mintrom, M. (1995) Public Entrepreneurs: Agents for Change in American Government, Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Sugiyama, M.; Akashi, O.; Wada, K.; Kanudia, A.; Li, Y.; Weyant, J. Energy efficiency potentials for global climate change mitigation. Climatic Change 2013, 123, 397–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swinkels, M. How ideas matter in public policy: a review of concepts mechanisms, and methods. International Review of Public Policy 2020, 2, 281–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teske, P.; Schneider, M. The bureaucratic entrepreneur: The case of city managers. Public Administration Review 1994, 54, 331–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tosun, J.; Tobin, P.; Farstad, F. Intermediating climate change: Conclusions and new research directions. Policy Studies 2023, 44, 687–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Malmborg, F. Exploring advocacy coalitions for energy efficiency: Policy change through internal shock and learning in the European Union. Energy Research & Social Science 2021, 80, 102248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Malmborg, F. Theorising member state lobbying on European Union policy on energy efficiency. Energy Policy 2022, 167, 113057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Malmborg, F. (2023a) First and last and always: Politics of the ’energy efficiency first’ principle in EU energy and climate policy, Energy Research & Social Science, 101, 103126. [CrossRef]

- (2023b) Tales of creation: Advocacy coalitions, beliefs and paths to policy change on the ‘energy efficiency first’ principle in EU, Energy Efficiency, 16, 10168. [CrossRef]

- von Malmborg, F. (2024a) Explaining differences in policy learning in the EU ‘Fit for 55’ climate policy package, European Policy Analysis, 10, 412-448. [CrossRef]

- von Malmborg, F. (2024b) At the controls: Politics and policy entrepreneurs in EU policymaking to decarbonise maritime transport, Review of Policy Research, 42, 12609. [CrossRef]

- von Malmborg, F. (2024c) Strategies and impacts of policy entrepreneurs: Ideology, democracy, and the quest for a just transition to climate neutrality, Sustainability, 16, 5272. [CrossRef]

- von Malmborg, F. (2024d) Tapping the conversation on the meaning of decarbonization: Discourses and discursive agency in EU politics on low-carbon fuels for maritime shipping, Sustainability, 16, 5589. [CrossRef]

- von Malmborg, F.; Strachan, P.A. Advocacy coalitions and paths to policy change for promoting energy efficiency in European industry. Energies 2023, 16, 3785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Malmborg, F.; Björklund, M.; Nordensvärd, J. (2023a) Framing the benefits of European Union policy expansion on energy efficiency of buildings: A Swiss knife or a trojan horse? European Policy Analysis, 9, 219-243. [CrossRef]

- von Malmborg, F.; Rohdin, P.; Wihlborg, E. (2023b) Climate declarations for buildings as a new policy instrument in Sweden: A multiple streams perspective, Building Research & Information, 51, 2222320. [CrossRef]

- Weiss, J.A. The power of problem definition: The case of government paperwork. Policy Sciences 1989, 22, 97–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wettestad, J.; Eikeland, P.O.; Nilsson, M. (2012). EU climate and energy policy: A hesitant supranational turn, Global Environmental Politics, 12, 67-86. [CrossRef]

- Wihlborg, E. (2018). Political entrepreneurs as actors in governance networks: conceptualising political entrepreneurs through the actor-network approach. In Karlsson, C.; Silander, C.; Silander, D. (eds.), Governance and Political Entrepreneurship in Europe, Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar; 25-41.

- Willis, R.; Curato, N.; Smith, G. Deliberative democracy and the climate crisis. WIREs Climate Change, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winkel, G.; Leipold, S. Demolishing dikes: Multiple streams and policy discourse analysis. Policy Studies Journal 2016, 44, 108–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, S.; Mandel, T.; Thomas, S.; Brugger, H. Applying the Energy Efficiency First principle based on a decision-tree framework. Energy Efficiency 2022, 15, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahariadis, N. (2003) Ambiguity and Choice in Public Policy: Manipulation in Democratic Societies, Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press.

- Zahariadis, N. (2007) Ambiguity and multiple streams, In: Sabatier, P.A. (ed.), Theories of the Policy Process, 2nd ed., Boulder, CO: Westview Press; 65-92.

- Zahariadis, N. Ambiguity and choice in European public policy. Journal of European Public Policy, 15, 514–530 2008. [CrossRef]

- Zakari, A.; Khan, I.; Tan, D.; Alvarado, R.; Dagar, V. Energy efficiency and sustainable development goals (SDGs). Energy 2022, 239, 122365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zito, A.R. (2000) Creating Environmental Policy in the European Union, London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Zito, A.R. (2017) Expert networks and epistemic communities: articulating knowledge and collective entrepreneurship, In: Howlett, M.; Mukherjee, I. (eds., Handbook of Policy Formulation, Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar; 304-319.

- Zohlnhöfer, R.; Herweg, N.; Rüb, F. Theoretically refining the multiple streams framework: An introduction. European Journal of Political Research 2015, 54, 412–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Approach to policy change | Strategies used by policy entrepreneurs |

|---|---|

| Attention- and support seeking strategies | Problem framing; Idea generation Strategic dissemination of information Lead by example; Use demonstration projects. |

| Rhetorical persuasion; Media attention | |

| Exploitation of focusing event(s) | |

| Linking strategies | Coalition and team building with bureaucratic insiders and policy influencers outside of government |

| Issue linking | |

| Game linking | |

| Relational management strategies | Networking by using social acuity |

| Trust building | |

| Arena strategies | Venue shopping |

| Timing |

| Data sources | EE1 principle |

|---|---|

| Interviews | IP1. Head of Unit, Energy efficiency, European Commission, DG ENER (March 2023) IP2. Policy officer, Energy efficiency, European Commission, DG ENER (March 2023) IP3. Deputy director/associate, Regulatory Assistance Project (August 2022) IP4. Energy counsellor, Swedish Permanent Representation to the EU (March 2023) |

| Documents |

|

| Policy entrepreneur | Attention- and support seeking strategies | Linking strategies | Relational management strategies | Arena strategies |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RAP, ECF and EEFIG | ||||

| 2015–2023(change) | Problem framing, idea generation, strategic use of information, using demonstration projects, rhetorical persuasion | Coalition and team building with bureaucratic insiders and policy influencers outside of government, linking energy efficiency to issues such as energy systems perspectives, demand-response, climate change mitigation, multiple benefits | Networking by using social acuity | Timing, venue shopping, influencing EC as well as MEPs |

| EC (DG ENER) | ||||

| 2021–2023(change) | Problem framing, idea generation, strategic use of information, rhetorical persuasion | Linking energy efficiency to issues such as energy systems perspectives, demand-response, climate change mitigation, multiple benefits | n/a | Timing |

1 RAP is a global private sector think-tank based in Brussel, dedication to accelerate the clean energy transition through thought leadership. https://www,raponline.org

|

|

2 ECF is an international environmental NGO, working to save the world from climate catastrophes. https://www.europeanclimate.org

|

|

3 EEFIG is a hybrid sector expert group comprising over 200 organisations working with energy efficiency investments in EU. It was set up by the EC and the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) Finance Initiative in 2013. https://eefig.ec.europa.eu

|

|

4 For the Council to take a decision on legislation, qualified majority (>65 % of the votes) is needed. A group of member states counting >35 % of the votes can block a decision, hence a ‘blocking minority’. |

|

5 The responsible committee of the EP appoints a Member of the EP (MEP) as a so-called rapporteur, to draft a report with amendments to the EC proposal. The rapporteur is also acting as the EP’s lead negotiator in trilogue negotiations between the EP, the Council and the EC. |

|

6 So-called salami tactics means breaking favoured policies into modest segments and presenting them sequentially, steering policymakers toward the desired outcome without raising alarm at any one stage. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).