Introduction

The tumor microenvironment (TME) typically comprises various immune cells, including tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs), which play a crucial role in cancer progression. TAMs within the TME can exist in two distinct phenotypes: M1 TAMs (regulatory) and M2 TAMs (trophic) [

1]. M1 macrophages produce proinflammatory cytokines like IL-12 and TNF-α, activating T cells to attack cancer cells and demonstrating antitumor activity. The presence of M1 macrophages in tumors is often linked to better clinical outcomes due to their ability to regulate tumor growth. However, as cancer advances, intrinsic and extrinsic factors usually drive the polarization of tumor-infiltrating M1 TAMs into the M2 phenotype. These M2-polarized TAMs secrete various pro-tumoral factors such as IL-10, TGF-β, and VEGF, contributing to an immunosuppressive environment that favors tumor survival.

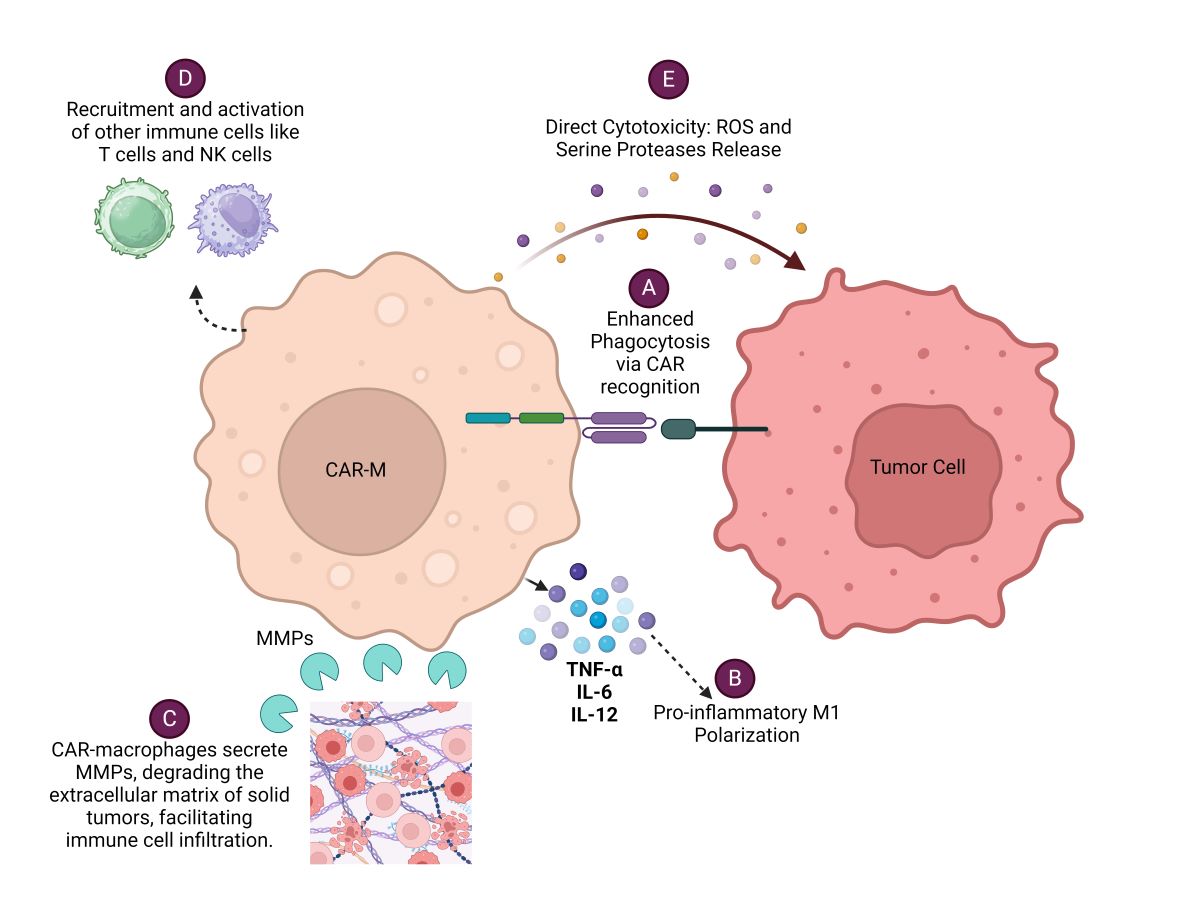

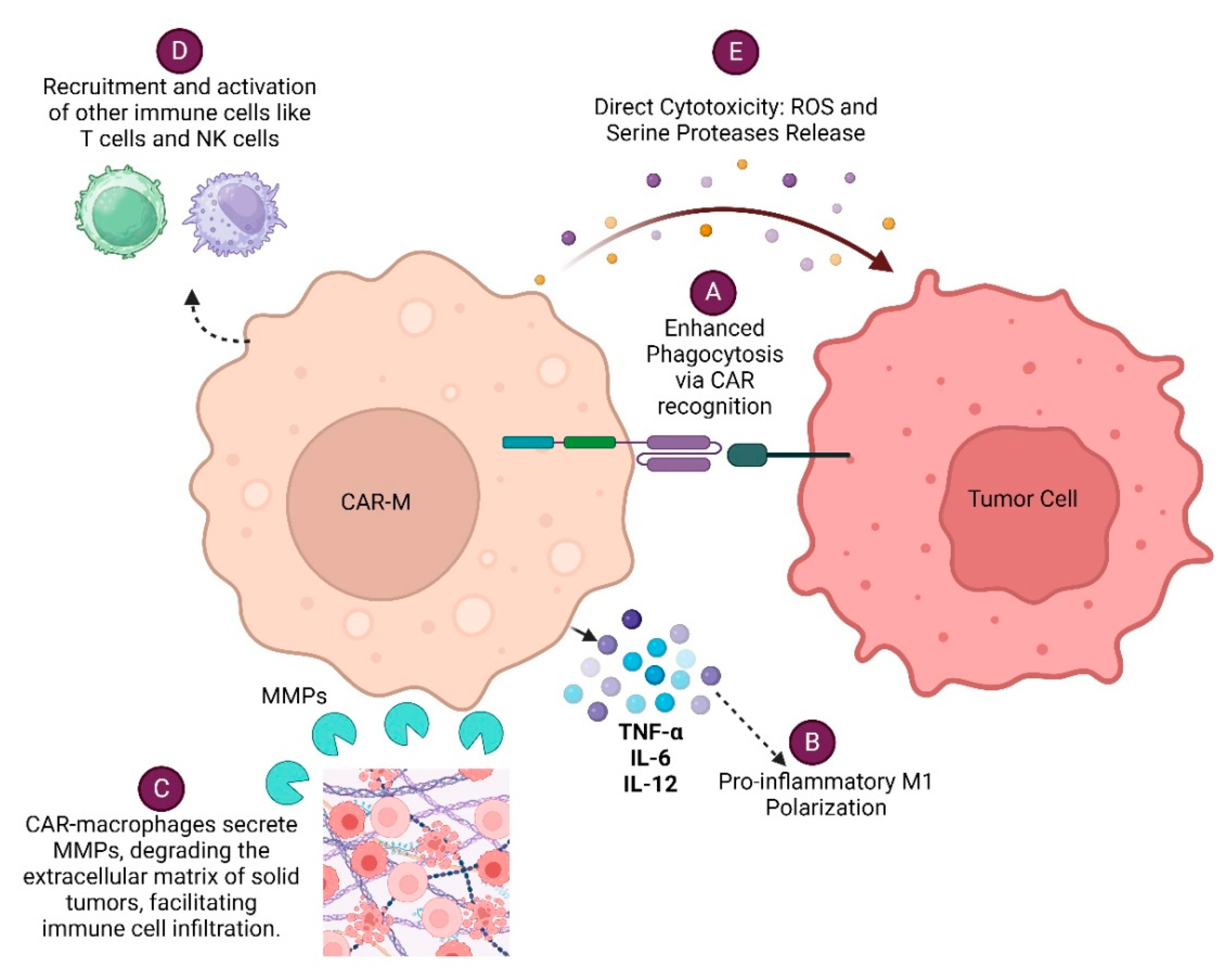

Various efforts of engineering macrophages to express receptors that recognize a range of tumor-associated antigens (TSA) are in the pipeline, allowing them to selectively target and destroy cancer cells. These engineered macrophages, known as Chimeric Antigen Receptor Macrophages (CAR-Macrophages), combine the specificity of CAR technology, traditionally used in T-cells, with the natural tumor-targeting ability of macrophages [

2,

3]. CAR-M eliminates tumor cells by various mechanisms. CAR-Macrophage (CAR-M) recognizes specific tumor antigens through its chimeric antigen receptor (CAR), leading to enhanced phagocytosis of the tumor cell. CAR-Ms can also modulate the tumor microenvironment by secreting various cytokines, metalloproteinases (MMPs), Reactive oxygen species (ROS) and serine proteases which facilitates immune cell infiltration and enhances anti-tumor responses of immune cells. Each of these mechanisms (

Figure 1) contributes to the overall effectiveness of CAR-Macrophages in targeting and eliminating cancer cells, making them a promising therapeutic approach in cancer immunotherapy.

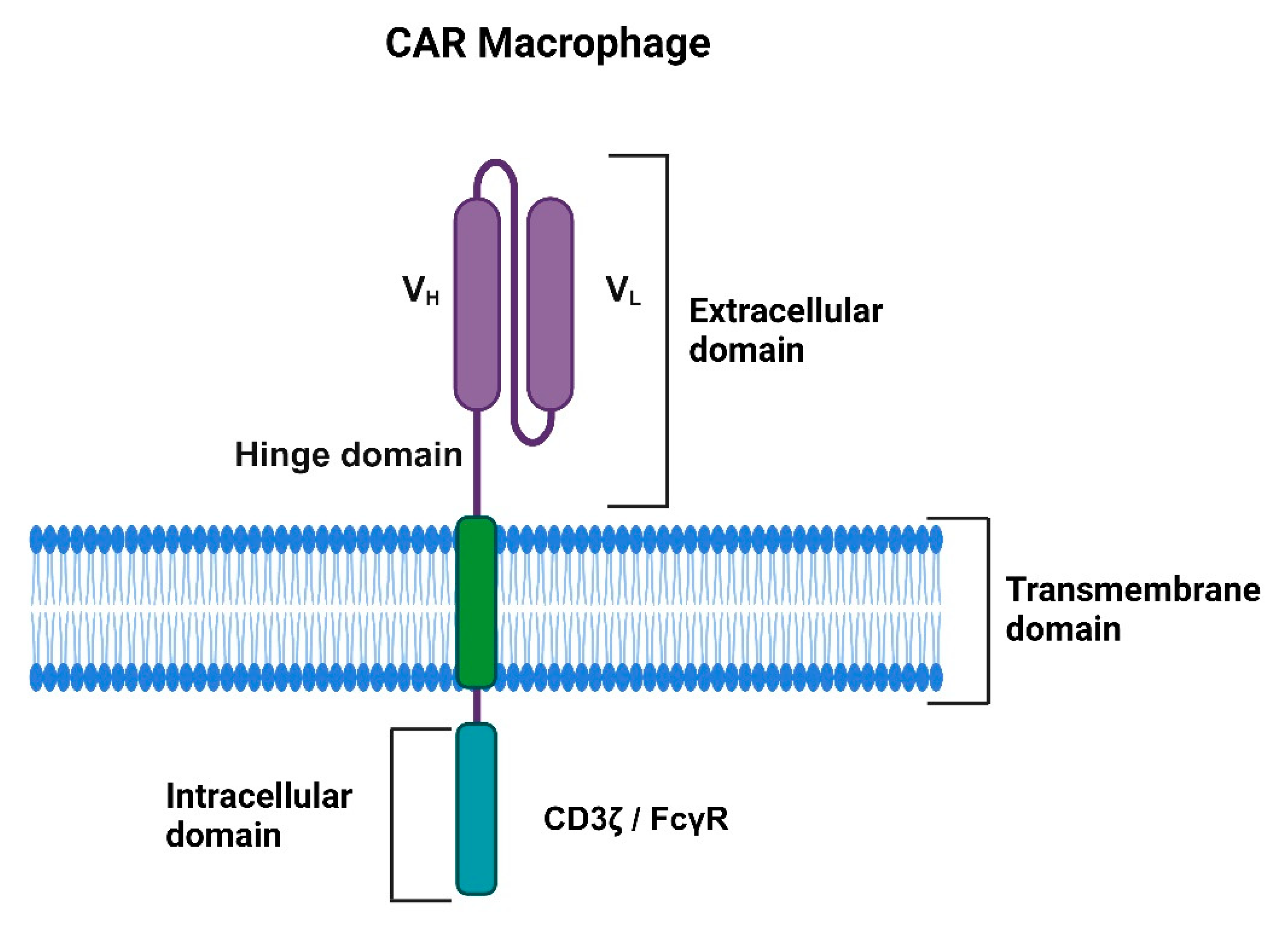

The structure of CAR-macrophages resembles CAR-T cells comprising an extracellular single-chain variable fragment (scFv), a hinge, trans-membrane, and intracellular signaling domains (

Figure 2). The scFv domain is responsible for recognizing and binding specific target antigens, including tumor-specific antigen (TSA), while the hinge domain provides flexibility and enhances the antigen-binding capacity of the scFv. The transmembrane domain connects the extracellular domains with the intracellular signaling domain, which is critical for downstream signaling and responsible for CAR macrophage antitumor activity [

3,

4]. Liu et. al compared the efficacy of CAR-M constructs incorporating various intracellular domains, including the Fc gamma receptor (CAR-MFcRγ), multiple EGF-like domains (CAR-MMegf10), and the CD19 cytoplasmic domain, which recruits the p85 subunit of phosphoinositide-3 kinase (CAR-MPI3K). The study found that CAR-M cells with the FcRγ signaling domain exhibited a significantly enhanced capacity for phagocytosis and cancer cell killing compared to those with the CAR-MPI3K or CAR-MMegf10 domains [

4].

Pre-Clinical Efficacy of CAR-Ms Therapy

Zhang et al. (2020) engineered CAR-Ms by expressing CD19 and mesothelin surface markers on induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) to investigate the effects of CAR-Ms on cancer cells. The study involved co-culturing CAR (CD19)-iMac cells, CAR (meso)-iMac cells, and control iMac cells with CD19-expressing K562 leukemia cells and mesothelin-expressing OVCAR3 and ASPC1 ovarian and pancreatic cancer cells, respectively. Their findings revealed that K562-CD19 cells are more susceptible to CAR (CD19)-iMacs clearance than K562 alone. Likewise, CAR (meso)-iMac cells exhibited increased phagocytic activity against OVCAR3 and ASPC1 cells as opposed to control cells [

5]. Furthermore, when exposed to their target antigens, these CAR-iMacs displayed elevated secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines, indicating a shift towards a pro-inflammatory phenotype. When tumor-infiltrating macrophages get appropriate stimuli from the tumor microenvironment, they get polarized to pro-tumoral M2 tumor-associated macrophages (M2 TAM) and contribute to tumor growth by releasing immunosuppressive molecules like TGF, VEGF, and EGF [

6].

Kang et al. (2021) tackled this challenge by reprogramming macrophages into CAR-expressing cells with an anti-tumoral M1 phenotype. They accomplished

in vivo reprogramming of M2 macrophages using a macrophage-targeting polymer nanocarrier to deliver genes encoding CAR and interferon-γ (IFN-γ). The researchers designed these nanocarriers with a mannose moiety, such as mannose-conjugated polyethyleneimine (MPEI), since macrophages typically have high mannose receptor expression on their surface. Furthermore, M2 macrophages treated with MPEI/pCAR were co-cultured with NIH3T3 (ALK−), B16 F10 (ALK−), or Neuro-2a (ALK+) cancer cells for two days. The primed macrophages demonstrated increased antigen-specific phagocytosis compared to the control macrophages treated with MPEI/pGFP [

7]. Furthermore, treatment with MPEI/pIFN-γ significantly upregulated M1 effectors such as iNOS and downregulated M2 effectors like Arginase-2. The study also demonstrated that transfection of macrophages with MPEI/pCAR-IFN-γ improved their phagocytic activity against ALK-expressing Neuro-2a cancer cells and maintained an M1 phenotype post-phagocytosis. The subsequent in vivo experiments with priming of Neuro-2a tumor-bearing A/J mice with MPEI/pCAR-IFN-γ revealed no toxicity after 48 hours. Notably, 50% of mice treated with MPEI/pCAR-IFN-γ survived for at least 100 days without detectable tumors. Histological analysis revealed a significant reduction in cancer cells and a concomitant increase in apoptotic cells in the MPEI/pCAR-IFN-γ-treated group. The study implies that the combined impact of CAR-mediated phagocytosis and IFN-γ-induced macrophage activation augmented anti-tumor response, with evidence of Th1 bright effector responses and Th2dim response in these mice [

7].

Liu et al. (2022) conducted a study to explore the combined impact of CAR-T and CAR-M therapies, aiming to demonstrate their synergistic anti-tumor effects. By exploiting CAR-M's superior tumor homing and infiltration capabilities and CAR-T's potent cytotoxicity, the researchers sought to enhance overall anti-tumor efficacy. Their method involved using a lentiviral vector to transfect CD19-FcRγ CAR for CAR-M and a retrovirus for CAR-T cell transfection. They evaluated the second-generation CAR-α-T cells alongside CAR-MFcR cells against Raji cells, with untransduced CAR-T and GFP-M cells as controls. The results revealed that while CAR-T cells exhibited significantly more cytotoxicity than CAR-MFcR cells alone, the combination of CAR-T and CAR-MFcR significantly enhanced cytotoxic effects compared to individual treatments [

8]. Moreover, combining half doses of CAR-T and CAR-MFcR demonstrated superior tumor-killing ability compared to either treatment alone, suggesting a synergistic effect. This was further supported by using other CAR-M types against murine cancer cells, indicating a promising and innovative combination strategy for cancer treatment. The study also uncovered that CAR-T-derived cytokines enhanced the cytotoxicity of CAR-MFcR by driving them towards a more M1 phenotype, significantly boosting their tumor-killing ability. This synergy between CAR-T and CAR-MFcR was associated with the upregulation of CD86 and CD80 on CAR-MFcR, promoting mutual activation and creating an inflammatory tumor microenvironment. Their study also found that CAR-MFcR substantially decreased CD62L expression in CAR-T cells, indicating heightened activation. Moreover, the presence of CAR-MFcR or macrophage cells reduced the expression of exhaustion markers PD-1, TIGIT, and LAG-3 on CAR-T cells, suggesting enhanced cell fitness. These results imply that CAR-MFcR cells amplify the tumor-killing potential of CAR-T cells by promoting their activation and fitness, potentially through the upregulation of CD86 and CD80 on macrophages. Although this research utilized cell lines, it sets the stage for investigating the combination of CAR-M with other immunotherapies to achieve improved outcomes [

8], as previously demonstrated by us on the Neuroendocrine tumors model of the pancreas [

9,

10,

11].

Chen et al. demonstrated the significance of HER2 and CD47-specific CAR-Ms in immunotherapy against ovarian cancer. The engineered CAR-Ms effectively phagocytize ovarian cancer cells and primed cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CD8+ T cells) to secrete cytokines such as IL-2, TNF-α, and IFN-γ . They demonstrated that CAR-MFcR or M cells reduced the expression of exhaustion markers PD-1, TIGIT, and LAG-3 on CAR-T cells, suggesting improved fitness. These findings indicate that CAR-MFcR cells enhance CAR-T cell tumor-killing efficacy by promoting their activation and fitness, likely due to the upregulation of CD86 and CD80 on macrophages [

12].

Challenges, Limitations, and Future Directions of CAR-Macrophage

CAR macrophages offer several advantages over CAR-T cells for immunotherapy against solid tumors. Still, significant challenges must be addressed before this approach can be successfully translated from the laboratory to clinical practice. One of the primary issues is that macrophages do not proliferate after being administered, and the amount that patients can tolerate is limited, which could reduce the treatment's overall effectiveness. Additionally, after administration, exogenous macrophages tend to accumulate in the liver after passing through the lungs, diminishing their potential impact on cancer treatment.

Another major challenge is the complexity of the human tumor microenvironment, which is far more intricate than animal models, making it difficult to achieve effective treatment. The high heterogeneity of tumor cells often leads to insufficient expression of target antigens. This problem has been observed with CAR-T therapy and is likely to pose a significant obstacle to CAR-M therapy. Ensuring the stability and durability of genetic modifications in macrophages is another hurdle. Advances in gene editing technologies, like CRISPR, are being explored to enhance the precision and stability of these genetic modifications.

Moreover, minimizing potential off-target effects and preventing excessive inflammation is crucial to regulating the immune response and maximizing anti-tumor effects. It is essential to develop strategies that enhance the infiltration and stability of CAR macrophages within the tumor microenvironment for them to be successful. The scalability and cost-effectiveness of producing CAR macrophages for widespread clinical use also present significant logistical and technical challenges. Efficient production processes must be established to generate sufficient quantities of high-quality CAR macrophages, making this therapy accessible to a broader patient population.

Future research directions for CAR macrophages include improving their specificity and targeting capabilities, exploring combination therapies to boost their effectiveness, and conducting extensive clinical trials to validate their safety and efficacy in treating various types of cancer. By addressing these challenges and deepening our understanding of CAR macrophage biology, this technology holds the promise of providing new hope for cancer patients.

Author Contribution

The author confirms their contribution to the paper as follows: Study conception and design: Aklank Jain and Hridayesh Prakash; Literature search, Shorting and Data collection: Dewan Chettri, Bibhu Prasad Satapathy, Rohit Yadav, Vivek Uttam; Draft manuscript preparations: Dewan Chettri, Bibhu Prasad Satapathy, Rohit Yadav, Vivek Uttam; Final Review and edition: Aklank Jain, Hridayesh Prakash and Vivek Uttam.

Funding

This work was supported by extramural funding from Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR) to HP ( 5/13/16/2022/NCD-III/138204).

Data Availability Statement

Not Applicable.

Institutional Review Board Statementl

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

Prof. Aklank Jain, Department of Zoology, is thankful to the Central University of Punjab and the DST-PURSE Scheme.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest to report.

References

- Zhang, Q. and M. Sioud, Tumor-Associated Macrophage Subsets: Shaping Polarization and Targeting. Int J Mol Sci, 2023. 24(8). [CrossRef]

- Hadiloo, K., et al., The CAR macrophage cells, a novel generation of chimeric antigen-based approach against solid tumors. Biomark Res, 2023. 11(1): p. 103. [CrossRef]

- Chen, K., et al., CAR-macrophage versus CAR-T for solid tumors: The race between a rising star and a superstar. Biomol Biomed, 2024. 24(3): p. 465-476. [CrossRef]

- Satapathy, B.P., et al., The synergistic immunotherapeutic impact of engineered CAR-T cells with PD-1 blockade in lymphomas and solid tumors: a systematic review. Front Immunol, 2024. 15: p. 1389971. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L., et al., Pluripotent stem cell-derived CAR-macrophage cells with antigen-dependent anti-cancer cell functions. J Hematol Oncol, 2020. 13(1): p. 153. [CrossRef]

- Hao, N.B., et al., Macrophages in tumor microenvironments and the progression of tumors. Clin Dev Immunol, 2012. 2012: p. 948098. [CrossRef]

- Kang, M., et al., Nanocomplex-Mediated In Vivo Programming to Chimeric Antigen Receptor-M1 Macrophages for Cancer Therapy. Adv Mater, 2021. 33(43): p. e2103258. [CrossRef]

- Liu, M., et al., CAR-Macrophages and CAR-T Cells Synergistically Kill Tumor Cells In Vitro. Cells, 2022. 11(22). [CrossRef]

- Prakash, H., et al., Low doses of gamma irradiation potentially modifies immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment by retuning tumor-associated macrophages: lesson from insulinoma. Carcinogenesis, 2016. 37(3): p. 301-313. [CrossRef]

- Nadella, V., et al., Low dose radiation primed iNOS + M1macrophages modulate angiogenic programming of tumor derived endothelium. Mol Carcinog, 2018. 57(11): p. 1664-1671. [CrossRef]

- Klug, F., et al., Low-dose irradiation programs macrophage differentiation to an iNOS(+)/M1 phenotype that orchestrates effective T cell immunotherapy. Cancer Cell, 2013. 24(5): p. 589-602. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y., et al., The application of HER2 and CD47 CAR-macrophage in ovarian cancer. J Transl Med, 2023. 21(1): p. 654. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).