1. Introduction

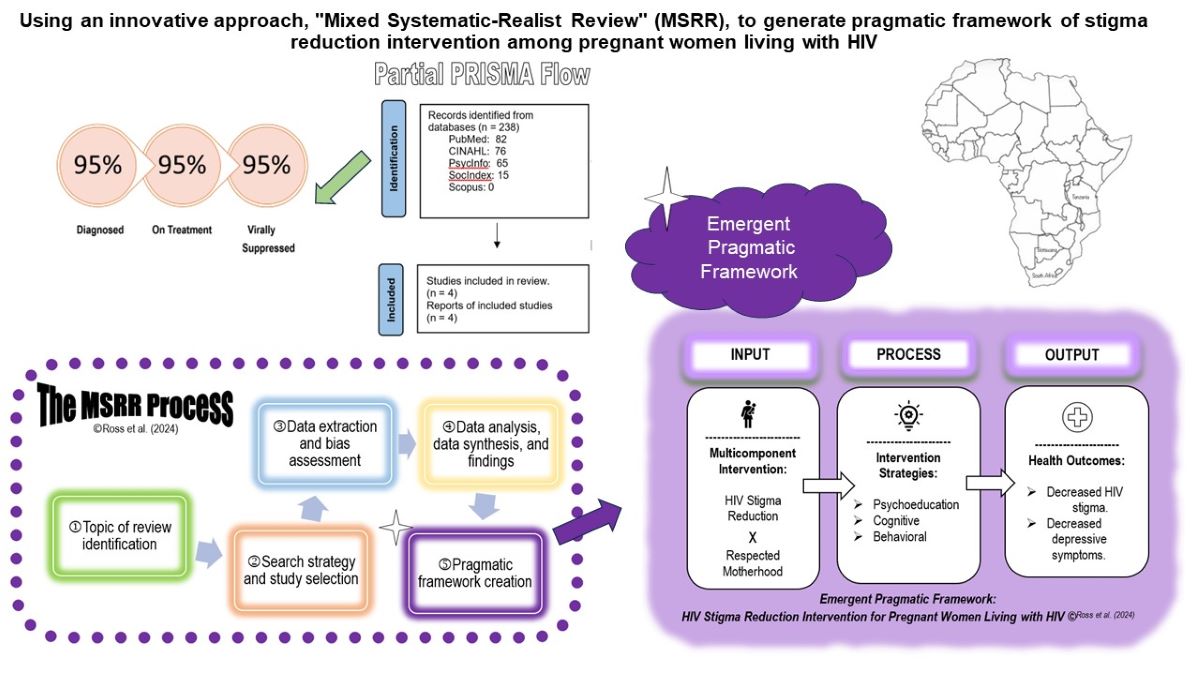

HIV stigma, the negative attitudes, beliefs, and discrimination directed toward people living with HIV, is widespread and is a crucial challenge for effective responses to the HIV and AIDS epidemic globally (UNAIDS, 2022). HIV stigma is a social process rooted in power differentials between groups of people, resulting in negative mentality and behaviors toward people living with HIV. This social stigma can leave HIV-infected individuals feeling traumatized and less likely to adhere to treatment plans (Link & Phelan, 2001). Rates of HIV stigma can range widely from 25% to 80% in Liberia, Thailand, and the USA (Centers for Diseases Prevention Centers [CDC], 2018; Bonnington et al., 2017; ICF, 2015; Peltzer et al., 2018; Ross et al., 2013). Pregnant women living with HIV (pregnant WLHIV) are particularly vulnerable to stigmatization, trauma, and depressive symptoms and are frequently blamed for continuing pregnancy despite the knowledge of their HIV status (Ross et al., 2009, 2013; Yang et al., 2022), potentially hindering antiretroviral therapy (ART) initiation and HIV adherence, leading to fastening HIV progression and HIV mother to child transmission, (Adam et al., 2021; Bonnington et al., 2017; Fauk et al., 2021; Ross, 2012; Sakyi et al., 2020a, 2020b). A scoping review reported that stigma reduction interventions were effective in reducing healthcare providers’ stigma attitudes towards individuals with HIV (Smith et al., 2020), and recent studies among diverse samples of individuals with HIV showed mixed results of stigma reduction interventions (Feyissa et al., 2012, 2019; Hartog et al., 2020; Smith et al., 2020; Stangl et al., 2013). However, a synthesis from such intervention studies among pregnant women living with HIV (pregnant WLHIV) does not exist. Understanding HIV stigma reduction programs among pregnant WLHIV can inform future HIV stigma reduction intervention for the target population, moving towards the ambitious goal of 95-95-95 as proposed by the UNAIDS (2022) to have 95% of individuals living with HIV know their HIV status, 95% of HIV-infected individuals on ART, and 95% of those on ART reach viral suppression. The present study synthesized research studies on stigma reduction interventions among pregnant WLHIV with three specific questions: 1) Are existing stigma reduction interventions effective in reducing HIV stigma and depressive symptoms? 2) Which mechanism promotes or prevents the effectiveness of stigma reduction interventions? 3) What is the emergent pragmatic framework for effective stigma reduction interventions?

2. Materials and Methods

Systematic review (SR) utilizes a rigorous process of analyzing and synthesizing research findings from existing literature (Joanna Briggs Institute, n.d.). SR is considered a positivist approach that emphasizes a quantitative, outcome-centric approach. SR does not create theories but provides a comprehensive summary of existing evidence. The SR technique helped answer the first question of whether existing HIV stigma reduction interventions are effective in reducing HIV stigma and depressive symptoms.

Conducting a realist review (RR) addressed the second question, exploring the mechanisms that promote or prevent these interventions' effectiveness. RR differs from SR by focusing on the interventions' mechanisms, contexts, and outcomes, going beyond assessing effectiveness to examine the "why," "how," and "when" of interventions while considering context and dosage. It utilizes a more flexible search strategy, purposive sampling, and data analysis that combines data extraction tables and thematic analysis to generate a pragmatic framework or midrange theory through the researcher’s reflexivity (Rycroft-Malone et al., 2012).

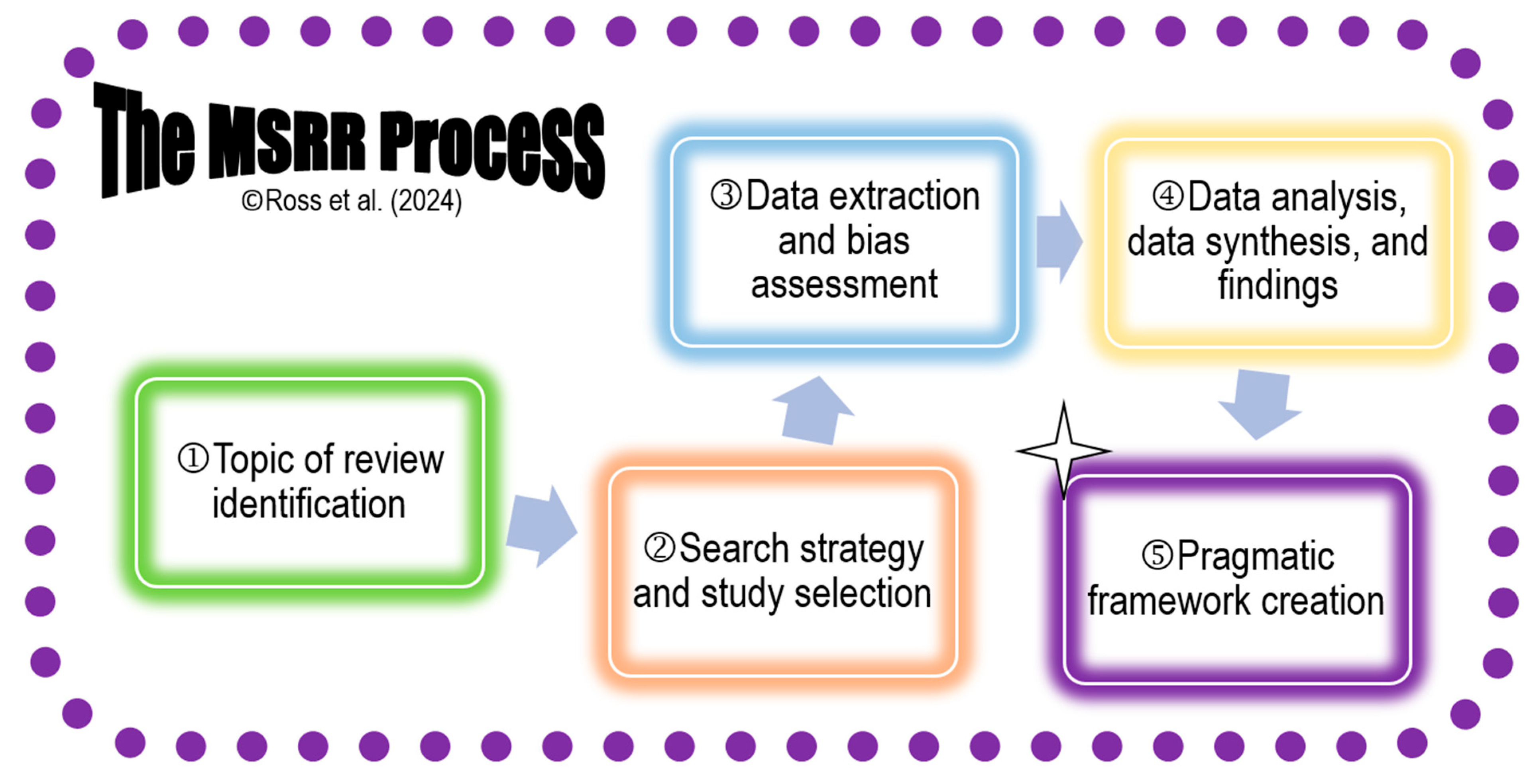

Neither systematic nor realist review could independently and comprehensively address research question # 3 in our literature synthesis, prompting the development of a new synthesis approach: the mixed systematic-realist review (MSRR). The innovative MSRR uses combined processes of SR and RR to analyze and synthesize complex and context-bound interventions, aiming to uncover not only the magnitudes but also the mechanisms, contexts, and outcomes of interventions. Grounded in pragmatism, MSRR utilizes structured tools (like SR) and purposive sampling (like RR).

Table 1 presents a comparative picture of SR, RR, and MSRR based on each method's objective, philosophy, search strategy, data analysis, synthesis, findings, and theory generation.

MSRR has five distinctive steps: 1) topic of review identification; 2) search strategy and study selection; 3) data extraction and bias assessment; 4) data analysis and synthesis; and 5) pragmatic framework creation (

Figure 1). Among these five steps, steps 3-5 are iterative, requiring repetitions until the final work is optimized. The findings generated by MSRR focus on effectiveness, mechanisms, and contextual factors, and provide a meaningful understanding of interventions. Additionally, MSRR can generate a pragmatic framework or practice theory while providing data-generated results, bridging the gap between SR and RR perspectives, and offering a holistic approach to evidence synthesis.

We selected stigma reduction interventions among pregnant WLHIV as the focus of our review. This decision was grounded in the issue's public health significance and background analysis, a literature review, and the identification of research gaps in our area of interest.

2.1. Search Strategy

Librarian involvement can enhance the effectiveness of literature searches. In this review, a university librarian (Lea Leininger) assisted with the literature search process. We adopted an iterative approach, refining search terms through exploratory searches for each concept (Aromataris & Riitano, 2014). Search terms were developed using the MeSH database and CINAHL headings. We employed relevant keywords (e.g., interventions, reduce, stigma, HIV, pregnancy and their synonyms) and combined them using Boolean operators (AND, OR, *) to optimize search results. No country or time restrictions were applied, but the search was limited to English-language journal articles. Databases searched included CINAHL, PubMed, SocIndex, PsycInfo, and Scopus. Due to pragmatic constraints, search terms were restricted to titles in PubMed and expanded to titles, abstracts, or keywords in Scopus. The final search was conducted in June 2024, yielding 238 articles. Further details of the search process are available in Leininger et al. (2022a, 2022b, 2022c, 2022d).

2.2. Study Selection

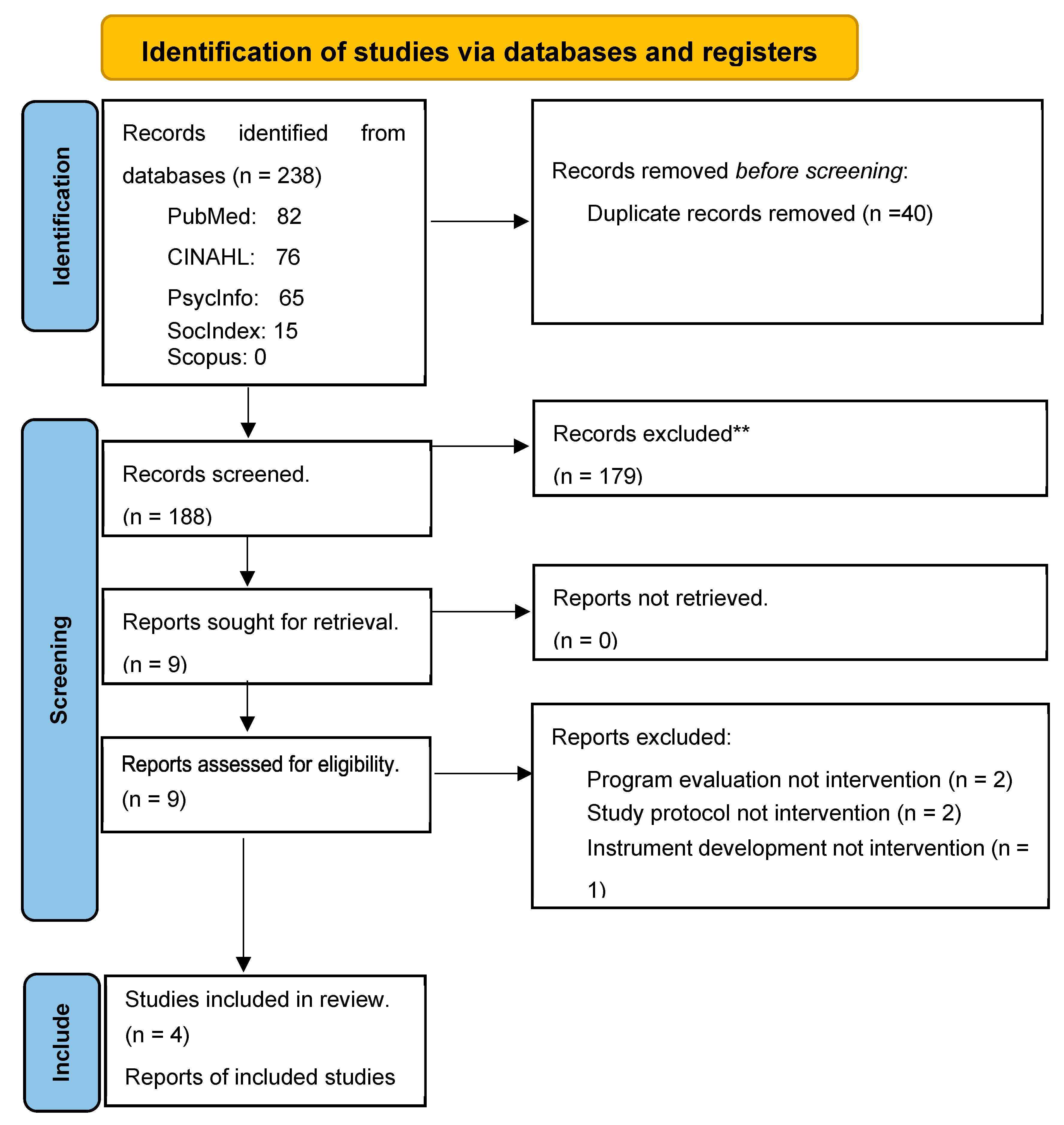

We utilized the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) flow diagram to document the process from study identification through selection, presented in

Figure 2 (Page et al., 2021). Of 238 articles initially identified through our search strategy, 188 remained after removing duplicates. Authors RR, SD, AA, and FA independently screened the titles and abstracts of the 188 articles, applying two inclusion criteria: (1) the study population must include pregnant WLHIV as the target population, and (2) the study’s intervention must focus on stigma reduction. The authors resolved discrepancies in article selection through discussions in team meetings. Following this step, nine articles were retained. Authors RR and FA then conducted independent full-text reviews, achieving 100% agreement to include four articles published between 2018 and 2022 for the final synthesis. The four studies were conducted exclusively in Sub-Saharan countries in Africa (

Figure 3), including Tanzania (Watt et al., 2022), South Africa (Peltzer et al., 2018, 2020), and Botswana (Yang et al., 2022). Botswana and South Africa are classified as high-middle-income countries, and Tanzania is a low-middle-income country (World Bank, 2023).

3.1. Data Extraction

The involvement of two or more team members is necessary to ensure high-quality data extraction and bias assessment. Author FA initially populated the data extraction table during the data extraction process. Author RR then reviewed the table for accuracy and made any necessary revisions. The finalized version of the table was discussed in a team meeting, where further input was incorporated before it was confirmed by all team members as complete (

Table 2).

3.2. Bias Assessment

To assess study bias, authors RR and FA independently evaluated each study using the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI, n.d.) guidelines, rating on 13 items with the options of yes or no. They found 100% agreement and presented the results at a group meeting (

Table 3). Since all studies were of good quality, they were included in developing pragmatic framework.

3. Results

Similar to the SR and RR processes, we present a synthesized narrative of the findings. Male partners were recruited in three of the studies (Peltzer et al., 2018, 2020; Watt et al., 2022). Two included articles are pilot studies that exclusively involved pregnant WLHIV (Watt et al., 2022; Yang et al., 2022). The remaining two articles (Peltzer et al., 2018, 2020) were based on one longitudinal project that included both HIV-negative and HIV-infected pregnant women. For this review, we only counted the pregnant WLHIV participants from Peltzer et al. (2018, 2020) as part of our total sample size, which amounted to 824 participants (n=417 intervention; n=407 control). All pregnant WLHIV participants were adults (≥ 18 years old). The synthesized findings are presented below and organized according to the research questions.

Question 1: Are existing stigma reduction interventions effective in reducing HIV stigma and depressive symptoms among pregnant WLHIV?

Overall, the stigma reduction interventions during pregnancy were found to be effective in reducing HIV stigma and depressive symptoms among pregnant WLHIV. Watt et al. (2022) reported that recipients of the Maisha intervention experienced a significant reduction in the moral judgment subscale of stigma attitudes (β= −3.5; 95% CI: −9.4, 2.4, p < .001), while Peltzer et al. (2018) demonstrated a decrease in stigma from baseline to 12 months (OR−1.391 [−2.128, −0.653], p < .001). Yang et al. (2022) also found significant reductions in HIV stigma (d = − 1.20; 95% CI − 1.99, − 0.39) from baseline to four months postpartum, with notable decreases across all stigma domains, including personalized stigma, disclosure concerns, negative self-image, and concerns with public attitudes. Additionally, Yang et al. (2022) reported that the intervention effectively reduced depressive symptoms among pregnant WLHIV. How stigma and depressive symptoms were measured is described below.

Stigma was measured as a critical outcome in all studies using various scales. The Botswana and South Africa studies (Peltzer et al., 2018; Yang et al., 2022) utilized the 40-item HIV Stigma Scale (Berger et al., 2001), which assesses four stigma dimensions: personalized stigma (internalized stigma), disclosure concerns, negative self-image, and concerns with public attitudes. In Tanzania, Watt et al. (2022) measured internalized stigma using Scale A of the HIV and Abuse Related Shame Inventory (Neufeld et al., 2012) and anticipated stigma with a 12-item scale developed by Turan et al. (2011) based on their personal and work experience in East Africa. Yang et al. (2022) also used the 20-item "What Matters Most" Cultural Stigma Scale for pregnant WLHIV to assess how cultural expectations intersect with HIV stigma, focusing on the notion of "respected motherhood." All four HIV stigma scales generated good internal consistency (α >.80). Spousal support effect was not reported, possibly due to low male partner participation and the fact that many male partners in Africa themselves stigmatize their spouse who is a pregnant WLHIV (Peltzer et al., 2018).

Depressive symptoms were measured across all studies at multiple time points. Yang et al. (2022) used the 20-item Center for Epidemiologic Studies of Depression Scale ([CES-D], Radloff, 1984) and found significant reductions in depressive symptoms from baseline to four months postpartum (d = − 1.96; 95% CI − 2.89, − 1.02). Peltzer et al. (2020) and Watt et al. (2022) used the 10-item Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS; Cox et al., 1987), with Peltzer et al. measuring depressive symptoms at baseline, six weeks, six months, and 12 months postpartum (T2: F (1, 704) = 6.7, p <.001) and Watt er al. measuring at baseline and three months later (β = −1.1; 95% CI: −4.2, 1.9). The EPDS showed good internal consistency in both studies (≥ .79). Across all studies, participants in the stigma reduction intervention groups experienced significantly fewer depressive symptoms than those in the control groups, and depressive symptoms decreased over time for those receiving the interventions.

Question 2: Which mechanism promotes or prevents the effectiveness of stigma reduction interventions among pregnant WLHIV?

Findings from the studies indicated that strategies aimed at reducing HIV stigma were most effective when delivered by healthcare providers, including lay healthcare workers and HIV-infected peers. However, spousal support did not demonstrate significant efficacy. The interventions across these studies utilized multicomponent modalities, including psycho-cognitive strategies, behavioral interventions, male partner support, and intersectional stigma reduction approaches. Notably, two studies were grounded in specific theoretical frameworks: Watt et al. (2022) applied the HIV Stigma Framework (Earnshaw et a., 2013), while Yang et al. (2022) employed the “What Matters Most” theory. Watt et al. (2022), working in Tanzania, used the HIV Stigma Framework, which posits that three types of stigmas hinder health-seeking behaviors among people living with HIV: internalized stigma (negative feelings and thoughts about oneself), anticipated stigma (the expectation of prejudice and discrimination from others); and enacted stigma (fears of prejudice and discrimination from others if HIV status becomes known). Watt et al. (2022) emphasized that concurrently reducing all three types of stigmas is critical for the intervention’s success. In contrast, Yang et al. (2022), working in Botswana, employed the “What Matters Most” theory, which frames HIV stigma as a threat to a woman’s identity as a “respected mother,” a central aspect of womanhood in the local context. The stigma is further exacerbated during pregnancy, as HIV is perceived as a sign of promiscuity and irresponsibility, potentially endangering the baby (Yang et al., 2022). This theory guided the interventions focus on addressing cultural and social stigmas related to motherhood. While Watt et al. (2022) and Yang et al. (2022) addressed HIV stigma, they conceptualized it differently based on their respective theoretical frameworks, leading to distinct approaches to stigma reduction. These findings underscore the importance of culturally and contextually tailored interventions to effectively reduce HIV stigma among pregnant WLHIV.

In Tanzania, Watt et al. (2022) described their Maisha intervention, which supplemented standard care with three sessions focused on reducing internalized and anticipated stigma using principles of cognitive behavioral therapy. The intervention, aimed at promoting HIV-care engagement, ART adherence, social support, and selective HIV disclosure, included counseling sessions for pregnant participants (n=31) and male partners (unclear number of participants). The sessions featured an 8-minute video including a case scenario about a couple experiencing HIV infection discovery at a prenatal clinic and psychoeducation about internalized and anticipated stigmas. The counselor then led the participants to reflect on HIV stigma attitudes aiming to encourage empathy toward HIV-infected individuals including oneself. In the final session, pregnant participants attended the session alone for an opportunity to discuss partner relationship issues with a facilitator and to receive reinforcement for HIV care, ART adherence, and stigma management. The control group (n=35) received standard care, including HIV testing and pre-test counseling, with block randomization used to assign participants.

In Botswana, Yang et al. (2022) implemented the 8-session Moving Mothers towards Empowerment (MME, meaning ‘respected woman’ in the Setswana language) program to address the intersectional stigma of HIV and threatened womanhood. Co-led by a trained counselor and a peer HIV-infected mother, the intervention combined psychoeducation, cognitive restructuring, and coping strategies (Yang et al., 2022). The psychoeducation sessions were designed to help pregnant WLHIV (n =44) reframe their thoughts to believe they could give birth to healthy newborns through ART adherence, preventing HIV transmission to the child and thereby achieving “respected motherhood.” Participants were pragmatically assigned to the intervention or control group based on clinic locations, with six high-volume clinics delivering the intervention and two others acting as control sites. The control condition (n=15) involved treatment as usual, though specific details were not provided.

Peltzer et al. (2018, 2020) developed a multi-session cognitive behavioral prevention of mother-to-child transmission (PMTCT) intervention in South Africa. While male involvement was encouraged, few male partners participated. The intervention was based on empirical evidence that social support could reduce depressive symptoms and improve ART adherence. This study used cluster randomization to place pregnant participants into either intervention (n=342) or control condition (n=357). Led by lay healthcare workers, four intervention sessions occurred before 36-week gestations, focusing on PMTCT, HIV status disclosure options, and medication adherence. The control group watched time-matched videos on unrelated health topics.

Question 3: What is the emergent pragmatic framework for effective HIV stigma reduction interventions among pregnant WLHIV?

This question was addressed via a direct content analysis using a pre-determined input-process-output (IPO) model (Hsieh & Shannon, 2005). Our team believed that the IPO model would provide a clear and logical framework for understanding HIV stigma reduction interventions among pregnant women living with HIV (WLHIV). First author, an experienced mixed-methods (qualitative and quantitative) researcher, led the analysis by iteratively organizing and combining text data from the four included articles into a structured and concise unit. She analyzed each article’s intervention description, implementation, and outcome evaluations, applying line-by-line coding to develop a concept map of key concepts and their interconnections. Notably, spousal support was excluded from the framework due to its ineffectiveness in reducing HIV stigma. The iterative analysis of each additional article built upon the original concept map until all four studies were fully incorporated into the pragmatic framework.

The preliminary framework was presented at a team meeting, where all members confirmed its clarity, logical flow, and representativeness. The team also confirmed the framework’s transferability, ensuring it captured all essential interconnected concepts (Elo et al., 2014). Minimal modifications were made to the framework, including eliminating an unnecessary equation, where MI = i(SR x RM) (a multicomponent intervention based on the interaction between stigma reduction and respected motherhood).

The final emergent pragmatic framework for a multi-component HIV stigma reduction intervention is grounded in the IPO model. The input includes a multicomponent intervention based on the intersection of two key concepts: HIV stigma reduction and respected motherhood. The HIV stigma reduction component follows the HIV Stigma Framework (Earnshaw et al., 2013), which posits that three types of stigmas (internalized, anticipated, and enacted) intersect to prevent the pregnant WLHIV from seeking HIV care. When this intersectional stigma is minimized, the HIV-infected woman will seek and adhere to ART treatment. The concept of respected motherhood is based on the “What Matters Most” theory, which asserts that a mother gains respect by taking care of herself and preventing mother-to-child HIV transmission (PMTCT) (Yang et al., 2022).

Given the intersection of these two concepts, the framework calls for a multicomponent intervention. The process involves delivering multiple psychoeducational, cognitive, and behavioral strategies- such as stigma reduction presentations by a healthcare team (including lay healthcare workers), viewing short videos, group discussions, and self-reflection. These sessions are typically spaced 2-4 weeks apart, based on counseling, education, and cognitive behavioral therapy principles. Stigma reduction strategies may include psycho-cognitive-behavioral modalities emphasizing the importance of being a respected mother by adhering to an ART regimen to decrease the chance of transmitting the virus to the newborn (psychoeducational-behavioral) and fostering a sense of empowerment by affirming that HIV-infected mothers are worthy, valuable, and should not feel ashamed (cognitive).

The

output consists of reductions in HIV stigma and depressive symptoms. It is hypothesized that the implementation of stigma reduction interventions will lead pregnant WLHIV to report 1) reductions in internalized, anticipated, and enacted HIV stigma and 2) decreases in depressive symptoms. These outcomes can be measured at baseline (before 24 weeks gestation) and at various follow-up points (4-6 weeks, 3 months, 6 months, and 12 months). The 40-item HIV Stigma Scale (Berger et al., 2001) can be used to assess stigma reduction, while the 20-item CES-D (Radloff, 1984) or the 10-item EPDS (Cox et al., 1987) can measure depressive symptoms, as both are valid and reliable tools. The finalized pragmatic framework is visually represented in

Figure 4, illustrating how this multi-component intervention could guide the development and evaluation of effective stigma reduction interventions for pregnant WLHIV.

4. Discussion

The novel MSRR approach emerged from our challenge to fit our research questions into existing literature review types. Utilizing MSRR has effectively facilitated our evidence analysis and synthesis, allowing us to answer our research questions comprehensively. One of the principal strengths of MSRR is its ability to integrate the advantages of multiple review methodologies. It follows the structured SR process while employing purposive sampling in the literature search, recognizing the constraints of labor and resources. This approach also enables a pragmatic assessment of study bias and encourages the development of an innovative, pragmatic framework.

We believe that the interdisciplinary efforts behind the creation of our multicomponent HIV stigma reduction intervention framework for pregnant WLHIV have resulted in a concise, informative, meaningful, and practical theory grounded in existing evidence and theories. The accompanying pictorial diagram vividly illustrates this framework, offering a visual representation that can be used to advance HIV research and practice. This framework can potentially guide future HIV stigma reduction research, serve as a component of interdisciplinary curriculum, be implemented in relevant healthcare settings, and inform health system policy. All of these applications are aimed at improving the mental health, quality of life, and Prevention of Mother-to-Child Transmission (PMTCT) uptake among traumatized pregnant WLHIV, ultimately contributing to achieving the 95-95-95 treatment targets in low- and middle-income countries across Africa and beyond (UNAIDS, 2014).

It is possible that relevant interventions exist but were not identified in our review. Although the team employed an iterative, multistep approach to operationalizing key concepts such as “interventions,” gaps may still arise from a search strategy focused solely on database searches. Additionally, with all the included studies conducted in Southern and Eastern Africa, the emergent framework may have limited practical applicability outside such sub-regions in the continent of Africa. Stigma reduction interventions targeting pregnant WLHIV remain relatively new. As more HIV stigma reduction interventions for this population are developed and studied, a future MSRR should be conducted to verify and, as necessary, modify the pragmatic framework, potentially enhancing its generalizability to other contexts.

5. Conclusions

The novel Mixed Systematic-Realist Review (MSRR) approach leverages the combined strengths of systematic and realist reviews. The results and the emergent pragmatic framework can be used for HIV stigma reduction education and research and clinical practice advancements. Although the emergent framework's applicability has limitations outside Africa, the MSRR offers broad utility and can be applied to various topics of interest to promote health equity and health promotion, including among traumatized individuals.

Contributions: Conceptualization, R.R.; methodology, R.R.; software, R.R., F.A., S. D., A. A., M.A., S.S., and J. H.; validation, R.R., F.A., S.D., A.A., and M.A.; formal analysis, R.R., F.A., S.D., A.A., and M.A.; resources, R.R., F.A., S. D., A. A., M.A., S.S., and J. H; data curation, R.R., F.A., S. D., and A. A.; writing—original draft preparation, R.R.; writing—review and editing F.A., S. D., A. A., M.A., S.S., and J. H.; visualization, R.R.; supervision, R.R.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Adam, A., Fusheini, A., Ayanore, M. A., Amuna, N., Agbozo, F., Kugbey, N., Kubi Appiah, P., Asalu, G. A., Agbemafle, I., Akpalu, B., Klomegah, S., Nayina, A., Hadzi, D., Afeti, K., Makam, C. E., Mensah, F., & Zotor, F. B. (2021). HIV stigma and status disclosure in three municipalities in Ghana. Annals of Global Health, 87(1). [CrossRef]

- Aromataris, E., & Riitano, D. (2014). Constructing a search strategy and searching for evidence. A guide to the literature search for a systematic review. The American Journal of Nursing, 114(5), 49–56. [CrossRef]

- Berger, B. E., Ferrans, C. E., & Lashley, F. R. (2001). Measuring stigma in people with HIV: psychometric assessment of the HIV stigma scale. Research in nursing & health, 24(6), 518–529. [CrossRef]

- Bonnington, O., Wamoyi, J., Ddaaki, W., Bukenya, D., Ondenge, K., Skovdal, M., Renju, J., Moshabela, M., & Wringe, A. (2017). Changing forms of HIV-related stigma along the HIV care and treatment continuum in sub-Saharan Africa: A temporal analysis. Sexually Transmitted Infections, 93. [CrossRef]

- Centers for Diseases Prevention Centers. (2023). Internalized HIV-related stigma. https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/statistics/mmp/cdc-hiv-internalized-stigma.pdf#:~:text=Nearly%202%20out%20of%203%20say%20that%20it,feeling%20guilty%20or%20ashamed%20of%20their%20HIV%20status.

- Cox, J. L., Holden, J. M., & Sagovsky, R. (1987). Detection of postnatal depression. Development of the item Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale. British Journal of Psychiatry, 150, 782-786. [CrossRef]

- Earnshaw, V. A., & Chaudoir, S. R. (2009). From conceptualizing to measuring HIV stigma: a review of HIV stigma mechanism measures. AIDS and behavior, 13(6), 1160–1177. [CrossRef]

- Elo, S., Kääriäinen, M., Kanste, O., Pölkki, T., Utriainen, K., & Kyngäs, H. (2014). Qualitative Content Analysis: A Focus on Trustworthiness. Sage Open, 4(1). [CrossRef]

- Evers, A. W., Kraaimaat, F. W., van Lankveld, W., Jongen, P. J., Jacobs, J. W., & Bijlsma, J. W. (2001). Beyond unfavorable thinking: The illness cognition questionnaire for chronic disease. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 12(6), 1026-1036.

- Fauk, N. K., Hawke, K., Mwanri, L., & Ward, P. R. (2021). Stigma and discrimination towards people living with hiv in the context of families, communities, and healthcare settings: A qualitative study in indonesia. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(10). [CrossRef]

- Feyissa, G. T., Abebe, L., Girma, E., & Woldie, M. (2012). Stigma and discrimination against people living with HIV by healthcare providers, Southwest Ethiopia. BMC public health, 12, 522. [CrossRef]

- Feyissa, G. T., Lockwood, C., Woldie, M., & Munn, Z. (2019). Reducing HIV-related stigma and discrimination in healthcare settings: A systematic review of quantitative evidence. PloS one, 14(1), e0211298. [CrossRef]

- Hartog, K., Hubbard, C. D., Krouwer, A. F., Thornicroft, G., Kohrt, B. A., & Jordans, M. J. D. (2020). Stigma reduction interventions for children and adolescents in low- and middle-income countries: Systematic review of intervention strategies. Social science & medicine (1982), 246, 112749. [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, H. F., & Shannon, S. E. (2005). Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative health research, 15(9), 1277–1288. [CrossRef]

- ICF. (2015). The DHS Program STATcompiler. http://www.statcompiler.com.

- Joanna Briggs Institute. (n.d.). Checklist for Randomized Controlled Trials: Critical appraisal tools for us in systematic reviews. Retrieved July 26, 2023, https://jbi.global/sites/default/files/2020-07/Checklist_for_RCTs.pdf.

- Leininger, L. & Avorgbedor, F. & Ross, R. (2022a). Interventions reduce stigma for pregnant or postpartum women with HIV (SocINDEX with Full Text). searchRxiv. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Leininger, L. & Avorgbedor, F. & Ross, R. (2022b). Interventions reduce stigma for pregnant or postpartum women with HIV (PsycInfo). searchRxiv. 2022.

- Leininger, L. & Avorgbedor, F. & Ross, R. (2022c). Interventions reduce stigma for pregnant or postpartum women with HIV. searchRxiv. 2022. 10.1079/searchRxiv/20220130328. 10.1079/searchRxiv/20220193226.

- Leininger, L. & Avorgbedor, F. & Ross, R. (2022d). Interventions to reduce stigma for pregnant or postpartum women with HIV (PubMed). searchRxiv. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., Shamseer, L., Tetzlaff, J. M., Akl, E. A., Brennan, S. E., Chou, R., Glanville, J., Grimshaw, J. M., Hróbjartsson, A., Lalu, M. M., Li, T., Loder, E. W., Mayo-Wilson, E., McDonald, S., McGuinness, L. A., … Moher, D. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ (Clinical research ed.), 372, n71. [CrossRef]

- Peltzer, K., Babayigit, S., Rodriguez, V. J., Jean, J., Sifunda, S., & Jones, D. L. (2018). Effect of a multicomponent behavioural PMTCT cluster randomised controlled trial on HIV stigma reduction among perinatal HIV positive women in mpumalanga province, south africa. Sahara J, 15(1), 80–88. [CrossRef]

- Peltzer, K., Abbamonte, J. M., Mandell, L. N., Rodriguez, V. J., Lee, T. K., Weiss, S. M., & Jones, D. L. (2020). The effect of male involvement and a prevention of mother-to-child transmission (PMTCT) intervention on depressive symptoms in perinatal HIV-infected rural South African women. Archives of women's mental health, 23(1), 101–111. [CrossRef]

- Radloff, L. S. (1977). The CES-D Scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement, 1(3), 385-401. [CrossRef]

- Ross, R., Sawatphanit, W., Draucker, C., & Suwansujarid, T. (2007). The lived experiences of HIV-positive, pregnant women in Thailand. Health Care for Women International, 28(8), 731-744. [CrossRef]

- Ross, R., Sawatphanit, W., & Zeller, R. (2009). Depressive symptoms among HIV-positive pregnant women in Thailand. Journal of nursing scholarship: An official publication of Sigma Theta Tau International Honor Society of Nursing, 41(4), 344–350. [CrossRef]

- Ross, R., Sawatphanit, W., Suwansujarid, T., Stidham, A. W., Drew, B. L., & Creswell, J. W. (2013). The effect of telephone support on depressive symptoms among HIV-infected pregnant women in Thailand: an embedded mixed methods study. The Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care: JANAC, 24(5), e13–e24. [CrossRef]

- Ross, R., Stidham, A. W., & Drew, D. (2012). HIV disclosure by perinatal women in Thailand. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing, 26(3), 232-239. [CrossRef]

- Rycroft-Malone, J., McCormack, B., Hutchinson, A. M., DeCorby, K., Bucknall, T. K., Kent, B.,.

- Schultz, A., Snelgrove-Clarke, E., Stetler, C. B., Titler, M., Wallin, L., & Wilson, V. (2012). Realist synthesis: Illustrating the method for implementation research. Implementation Science: IS, 7, 33. [CrossRef]

- Sakyi, K. S., Lartey, M. Y., Kennedy, C. E., Denison, J. A., Sacks, E., Owusu, P. G., Hurley, E. A., Mullany, L. C., & Surkan, P. J. (2020a). Stigma toward small babies and their mothers in Ghana: A study of the experiences of postpartum women living with HIV. PLoS ONE, 15(10 October 2020). [CrossRef]

- Sakyi, K. S., Lartey, M. Y., Kennedy, C. E., Dension, J. A., Mullany, L. C., Owusu, P. G., Sacks, E., Hurley, E. A., & Surkan, P. J. (2020b). Barriers to maternal retention in HIV care in Ghana: Key differences during pregnancy and the postpartum period. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 20(1). [CrossRef]

- Smith, M. K., Xu, R. H., Hunt, S. L., Wei, C., Tucker, J. D., Tang, W., Luo, D., Xue, H., Wang, C., Yang, L., Yang, B., Li, L., Joyner, B. L. jr, & Sylvia, S. Y. (2020). Combating HIV stigma in low- and middle-income countries healthcare settings: A scoping review. Journal of the International AIDS Society, 23: e25553. [CrossRef]

- Stangl, A. L., Lloyd, J. K., Brady, L. M., Holland, C. E., & Baral, S. (2013). A systematic review of interventions to reduce HIV-related stigma and discrimination from 2002 to 2013: how far have we come? Journal of the International AIDS Society, 16(3 Suppl 2), 18734. [CrossRef]

- UNAIDS. (2014). On the Fast-Track to an AIDS-free generation Retrieved from Fast-Track - Ending the AIDS epidemic by 2030 | UNAIDS.

- Watt, M. H., Knettel, B. A., Mwamba, R. N., Osaki, H., Ngocho, J. S., Kisig, G. A., Renju, J., Sao, S., & Vissoci, J., & Mmbaga, B. T. (2022). Pilot outcomes of Maisha: An HIV stigma reduction intervention developed for antenatal care in Tanzania. AIDS and Behavior, 25(4), 1171-1184. [CrossRef]

- World Bank. (2023). New World Bank country classifications by income level: 2022-2023. https://blogs.worldbank.org/opendata/new-world-bank-country-classifications-income-level-2022-2023.

- Yang, L.H., Eschliman, E.L., Mehta, H., Misra, S., Poku, O.B., Entaile, P., Becker, T.D., Melese, T., Brooks, M.J., Eisenberg, M.M., Stockton, M., Choe, K., Tal, D., Li, T., Go, V.F., Link, B.G., Rampa, S., Jackson, V., Manyeagae, G.D., Arscott-Mills, T., Goodman, M.S., Opondo, P., Ho-Foster, A.R., & Blank, M.B. (2022). A pilot pragmatic trial of a “what matters most”-based intervention targeting intersectional stigma related to being pregnant and living with HIV in Botswana. AIDS Research and Therapy, 19. [CrossRef]

- Yang, L. H., Ho-Foster, A. R., Becker, T. D., Misra, S., Rampa, S., Poku, O. B., Entaile, P., Goodman, M., & Blank, M. B. (2021). Psychometric validation of a scale to assess culturally-salient aspects of HIV stigma among women living with HIV in Botswana: Engaging "What Matters Most" to resist stigma. AIDS and behavior, 25(2), 459–474. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).