Submitted:

15 September 2024

Posted:

17 September 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

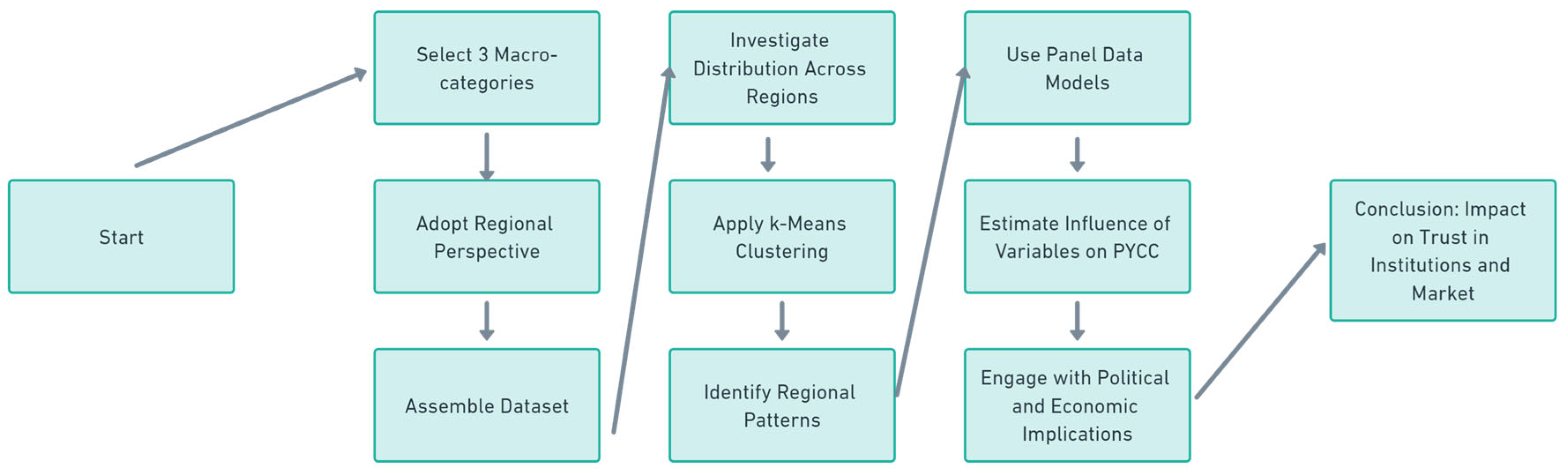

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

3. Data, Variables and Methodology

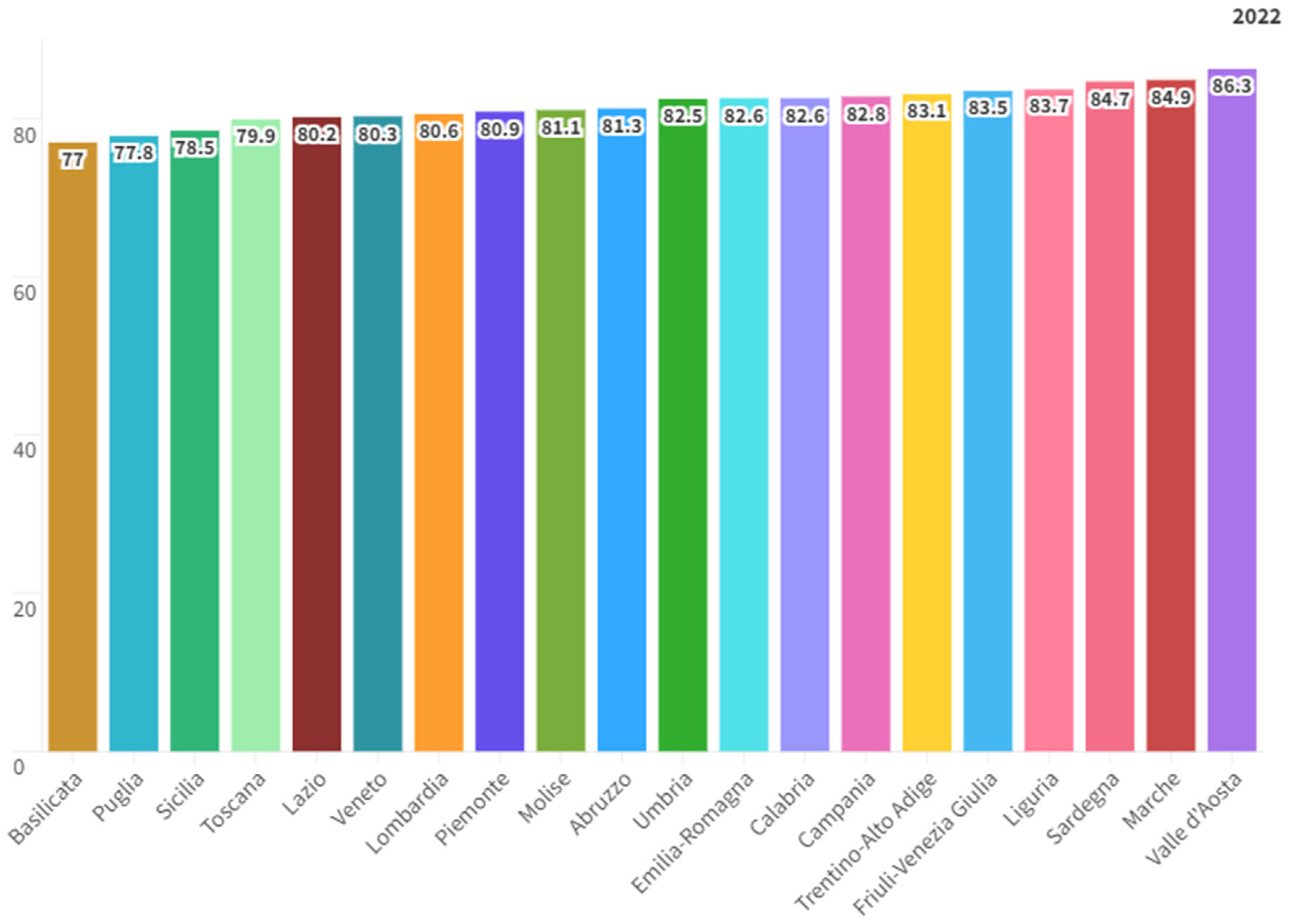

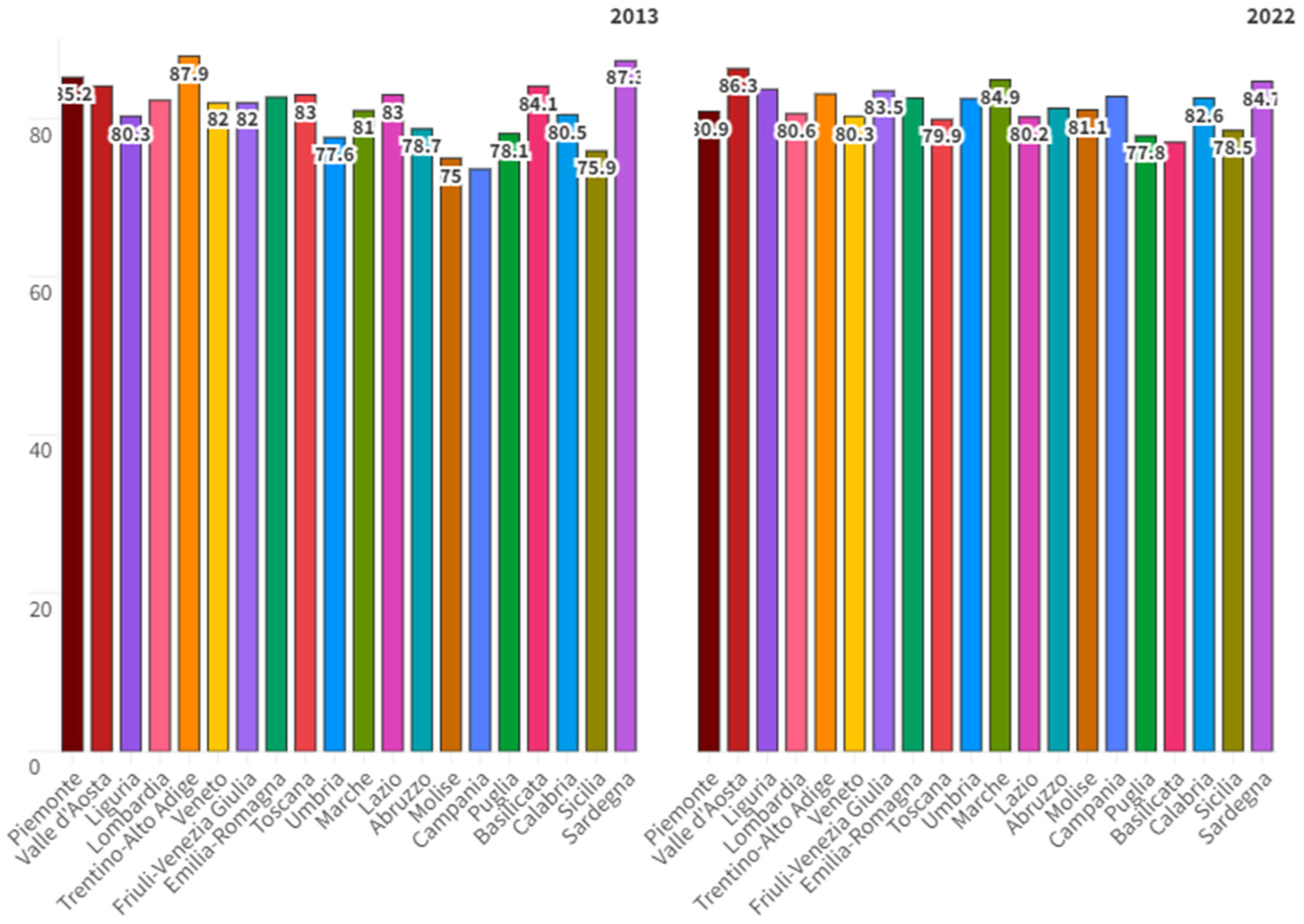

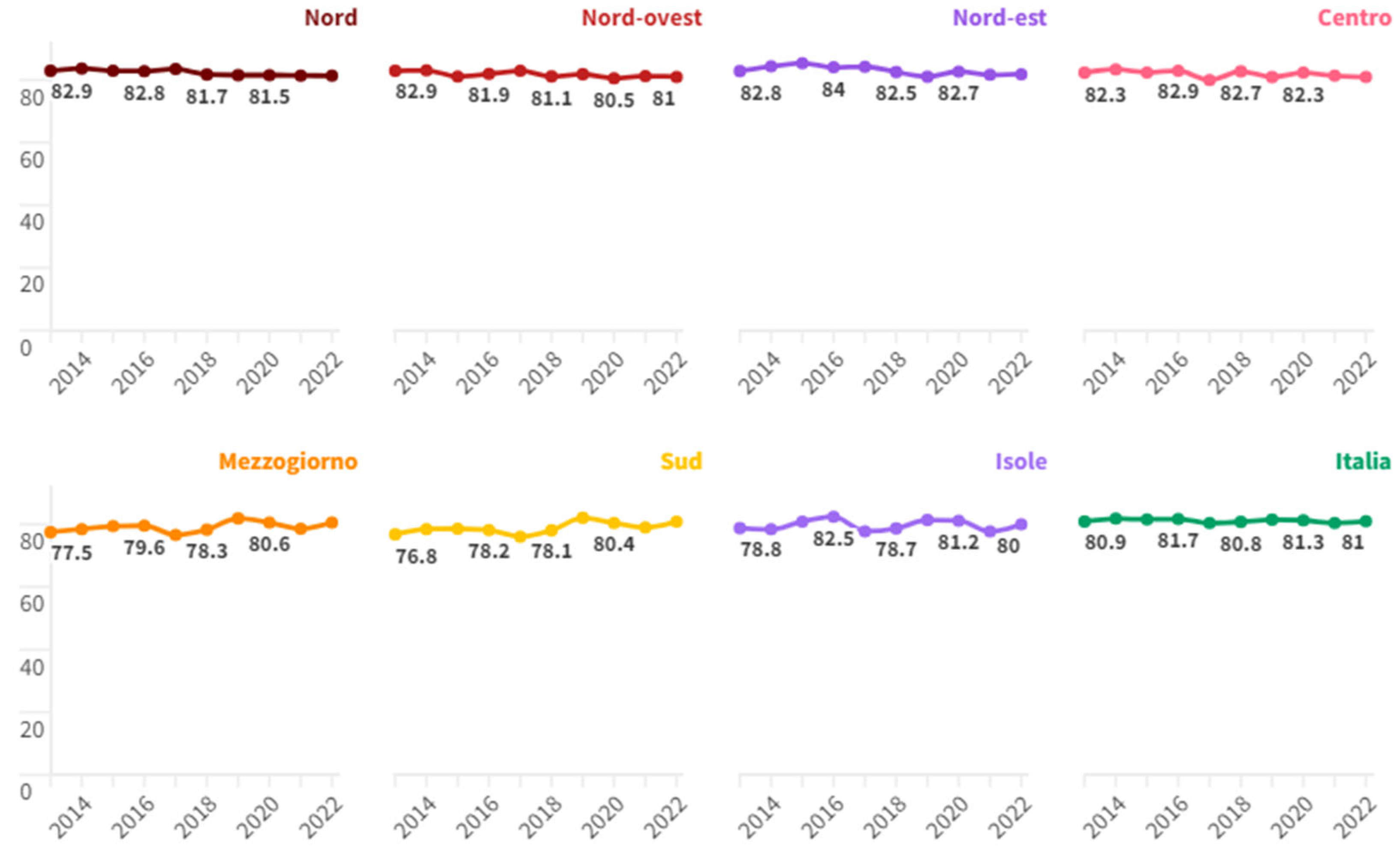

4. Rankings of Regions and Macro-Regions in the Sense of PYCC

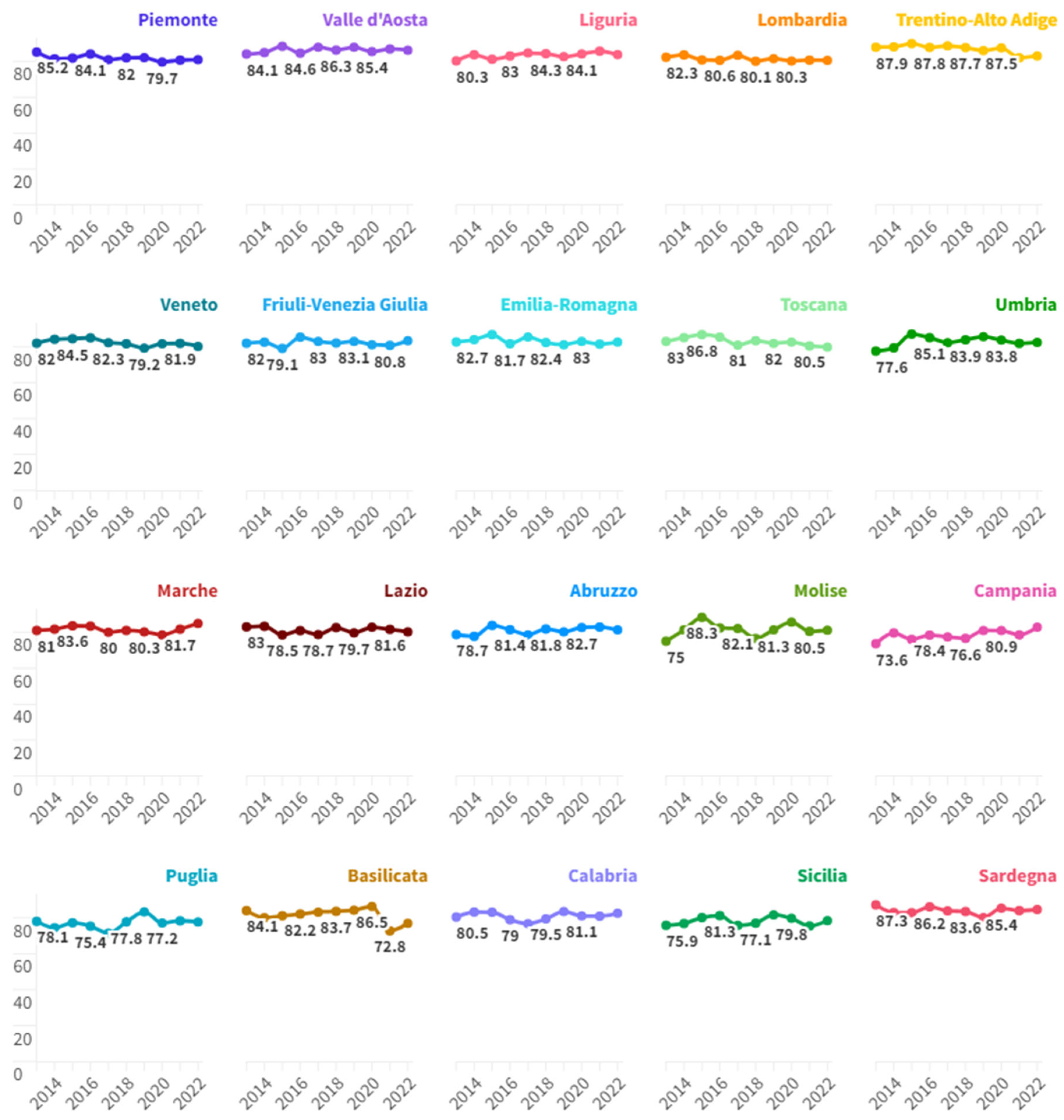

- A summary of the trend of the PYCC variable at regional level is shown in Figure 5.

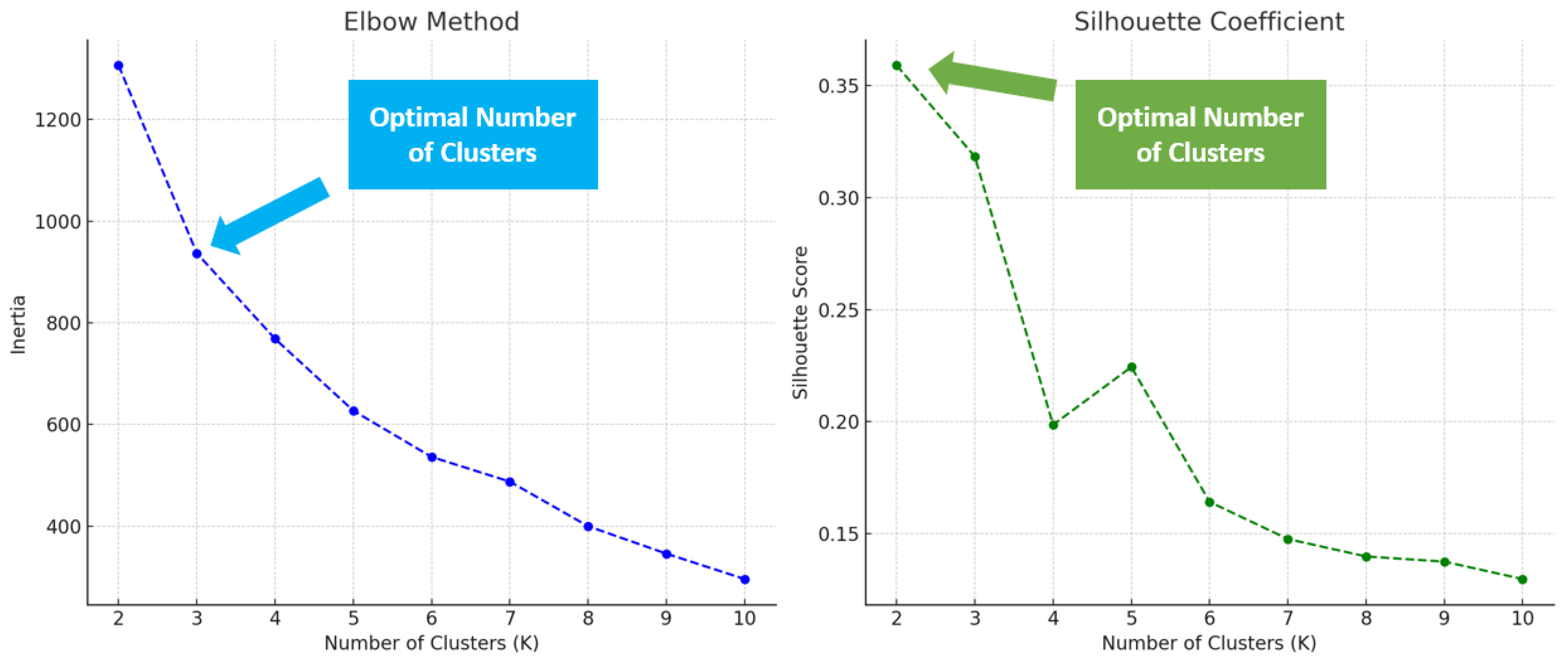

5. Clusterization with k-Means Algorithm

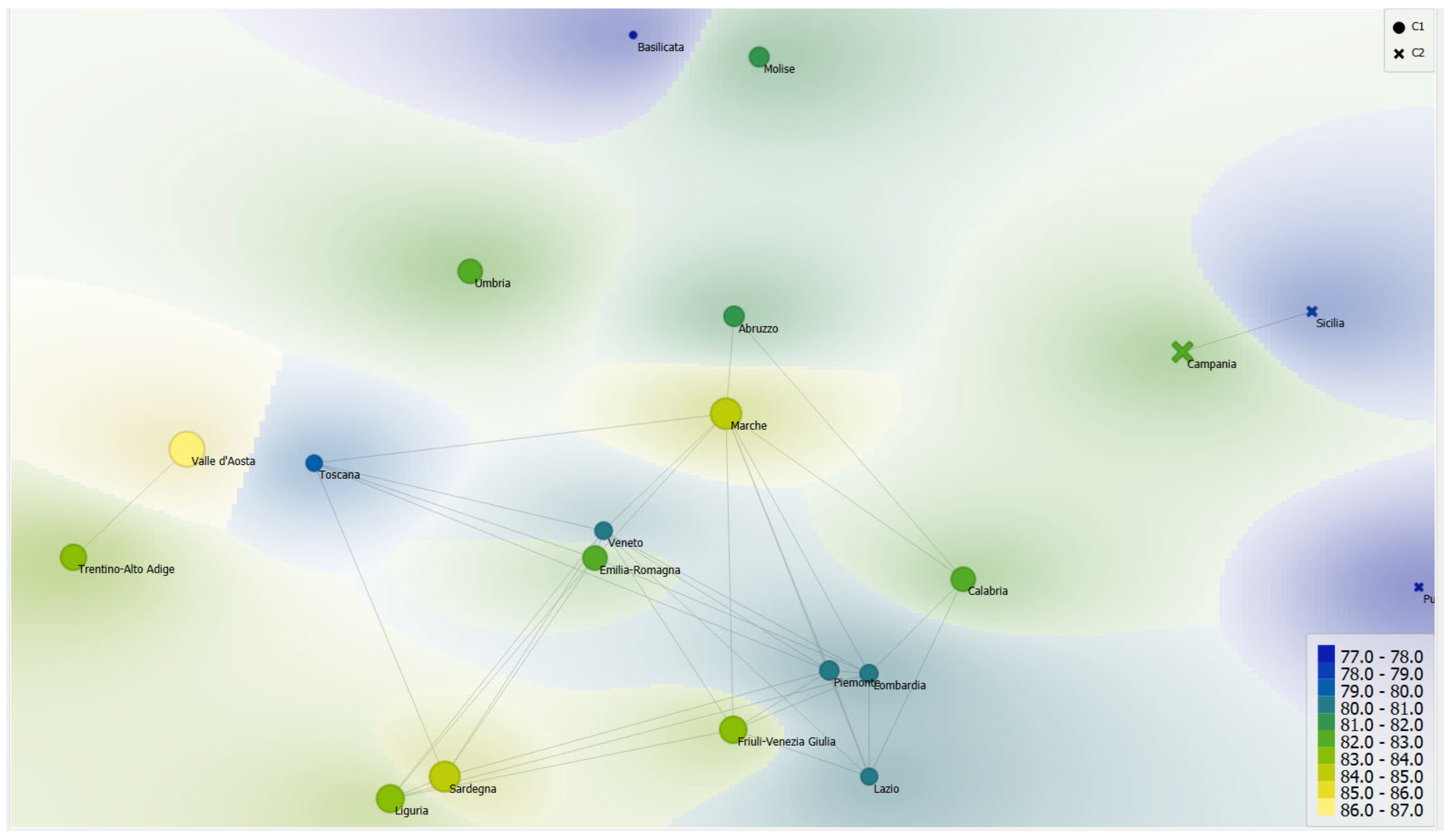

- Cluster 1 includes: Piemonte, Valle d'Aosta, Liguria, Lombardia, Trentino-Alto Adige, Veneto, Friuli-Venezia Giulia, Emilia-Romagna, Toscana, Umbria, Marche, Lazio, Abruzzo, Molise, Basilicata, Calabria, and Sardegna. These regions are characterized by relatively higher levels of economic development, more robust welfare systems, and stronger social safety nets compared to other parts of Italy. Over the years, these factors have likely contributed to a more consistent sense of social trust and reliability. People in these regions may feel more confident that they can rely on others in their community, whether through formal institutions or informal social networks. From 2013 to 2022, this trend of higher trustworthiness persisted, likely underpinned by steady employment rates, lower levels of poverty, and better access to public services, which all strengthen social cohesion (D’Adamo and Gastaldi, 2023; Algieri and Álvarez, 2023; Cattivelli, 2021).

- Cluster 2 includes: Campania, Puglia, and Sicilia. These regions have historically faced higher levels of unemployment, greater income inequality, and more fragile social structures, which may contribute to a weaker sense of trust among individuals. The differences in economic and social conditions across Italy's regions are significant, particularly between the more prosperous north and the less developed south. Southern Italy has long grappled with economic challenges, including a weaker labor market, lower levels of investment in public services, and higher rates of poverty. These structural issues likely erode the social bonds that foster trust and reliability within communities, as people may feel less supported by both formal institutions and informal social networks (Gentile et al., 2022; Petraglia and Scalera, 2021; Drago, 2021).

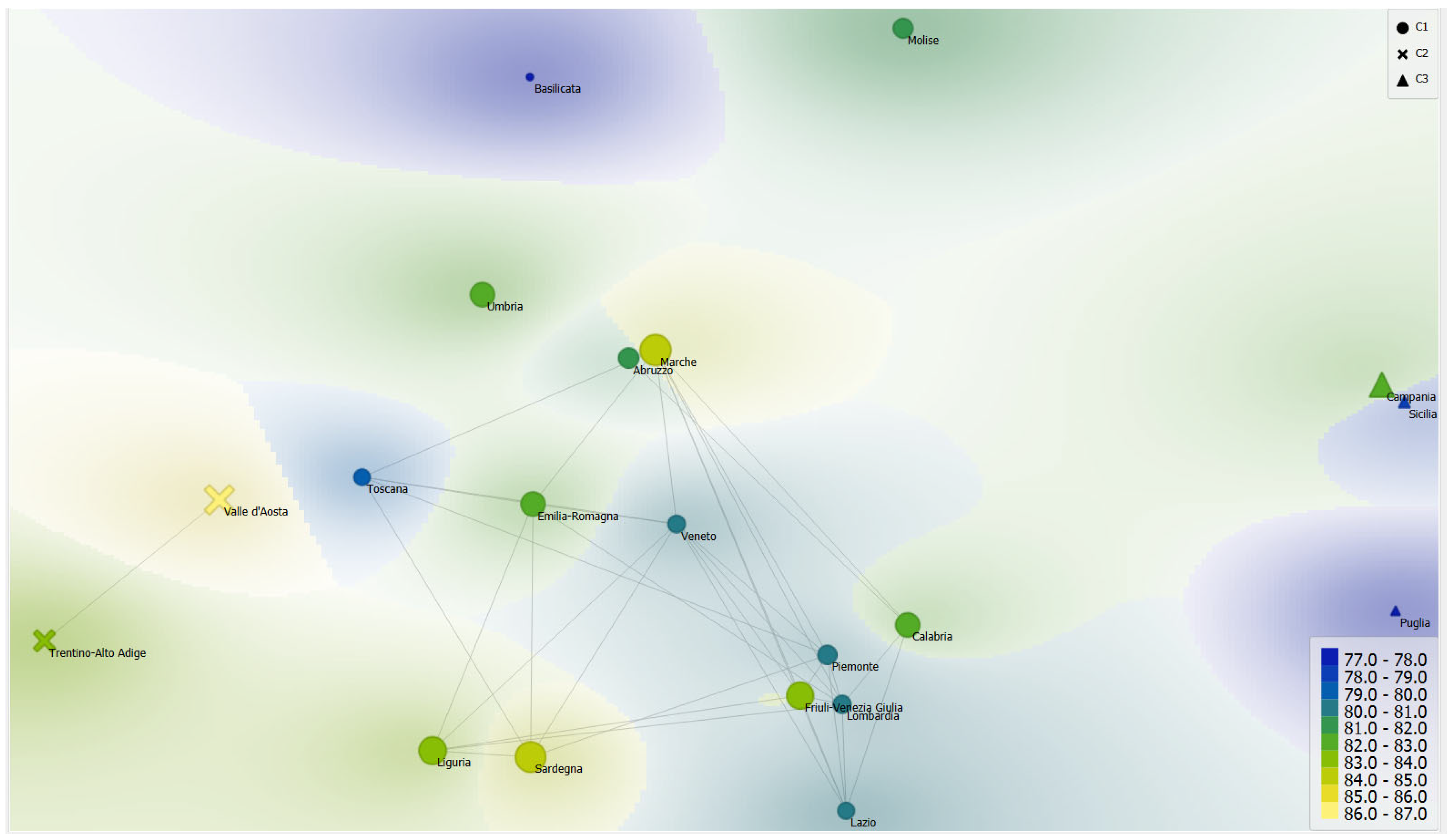

- C1: Piedmont, Liguria, Lombardy, Veneto, Friuli-Venezia Giulia, Emilia-Romagna, Tuscany, Umbria, Marche, Lazio, Abruzzo, Molise, Basilicata, Calabria, Sardinia. Cluster 1 (C1), comprising regions such as Piedmont, Liguria, Lombardy, Veneto, and Emilia-Romagna, reflects a group of regions predominantly located in northern and central Italy. These regions are often associated with higher levels of economic development, stronger welfare systems, and more robust social safety nets. This could explain why the median value for trust and social support in C1 is relatively high, at 81.3. While not the highest of the three clusters, this score suggests that people in these regions generally feel they can rely on others, which could be due to the presence of well-functioning public institutions, higher levels of employment, and a strong tradition of community engagement. These regions also benefit from a long history of industrialization and integration into European markets, which may contribute to a stable social environment that fosters trust (Maugeri et al., 2021; Bocci et al., 2021).

- C2: Aosta Valley, Trentino-Alto Adige. In contrast, Cluster 2 (C2) stands out for its composition and particularly high median value of 84.7. This cluster includes only two regions: Aosta Valley and Trentino-Alto Adige. Both regions are unique within Italy for their geographic isolation and special autonomous status. Their high scores in social trust could be attributed to several factors, including their relatively small populations, which may foster tighter-knit communities where individuals are more likely to rely on each other. Additionally, these regions benefit from higher levels of local governance and economic stability, thanks in part to their autonomy. Trentino-Alto Adige, in particular, has a strong tradition of local government and economic prosperity, which likely plays a role in the high level of social trust. The relative wealth and strong public services in these regions, including education and healthcare, also contribute to a sense of reliability and support among residents (Fazari and Musolino, 2023; Baroncelli, 2022, Rosini, 2022).

- C3: Campania, Apulia, Sicily. Cluster 3 (C3), which includes Campania, Apulia, and Sicily, represents the southernmost regions of Italy, and it has the lowest median value of 78.5. The social and economic challenges faced by southern Italy are well-documented, and these factors likely contribute to the lower levels of trust and perceived social support in C3. High levels of unemployment, lower educational attainment, and weaker public institutions all undermine social cohesion in these regions. In addition, the historical prevalence of organized crime and corruption in some parts of southern Italy may further erode trust in both formal institutions and informal social networks. Residents of these regions may feel that they cannot rely on either their fellow citizens or the government, leading to a lower sense of social trust. These issues are compounded by the fact that the southern regions have experienced high rates of emigration, particularly among young people, which can weaken community ties and further reduce the sense of social support (Savona et al., 2020; Falcone et al., 2020).

6. Econometric Model

- There is a positive relationship between PYCC and the following variables namely:

- LPE: the positive relationship between PYCC and LPE can be explored through the lens of social support networks and solidarity that often form in work contexts characterized by less favourable economic conditions. This positive link suggests that, despite economic challenges, there are positive social and relational dynamics emerging in work environments with a prevalence of low wages. In work contexts where employees face similar economic conditions, often characterized by low wages, a strong sense of solidarity can develop. Sharing common challenges can foster a supportive environment, where workers tend to help each other both professionally and personally. People working under conditions of low pay may be more inclined to build social support networks at the workplace and beyond. These networks can provide practical assistance, such as sharing caregiving responsibilities or support in financial emergencies, as well as offering emotional support. Working in low-wage contexts can also lead to shared values and a sense of belonging. This collective identity can strengthen interpersonal relationships and promote a culture of mutual support. People experiencing similar economic conditions tend to have higher levels of empathy and mutual understanding. This can translate into closer and more meaningful relationships, where there is a greater inclination to offer and receive support. In low-wage contexts, support can extend beyond the workplace, involving families and local communities. Communities may organize shared resources or mutual aid initiatives to help those facing economic difficulties. Despite economic challenges, LPE can benefit from robust and meaningful social support networks, highlighting how shared difficulties can act as a catalyst for forming strong interpersonal bonds and support networks. This demonstrates the importance of social and relational dimensions in mitigating the negative impacts of economic hardships and in promoting individual and collective well-being (Shook et al., 2020; Benassi and Vlandas, 2022, Sobering, 2021).

- SWWD: the positive relationship between PYCC and SWWD highlights how having a supportive network at work can significantly enhance an individual's satisfaction with their job. This connection suggests that when employees feel supported by their colleagues and superiors, they are more likely to experience higher levels of job satisfaction. The presence of supportive colleagues and managers can provide a buffer against workplace stress and challenges. Emotional support from co-workers can foster a sense of belonging and well-being, contributing to overall job satisfaction. A work environment where employees can rely on each other encourages collaboration and effective teamwork. When people feel they are part of a cohesive team, working towards common goals, their engagement and satisfaction with their job increase. Having mentors and supportive peers can facilitate opportunities for learning and professional growth. Employees who feel supported in their career development are more likely to be satisfied with their job, as they see a path for progression and improvement. A supportive network contributes to a positive work culture, where individuals feel valued and recognized. This positive environment can significantly boost job satisfaction, as employees feel their contributions are appreciated and that they are an integral part of the organization. When employees have a reliable support system at work, they are less likely to consider leaving their job. High job satisfaction, fostered by supportive relationships, contributes to higher retention rates within organizations. Support from co-workers and supervisors can enhance job performance. Employees who feel supported are more motivated and engaged, leading to better outcomes and further increasing job satisfaction. In essence, the positive correlation between having PYYC and experiencing SWWD underscores the importance of fostering supportive relationships in the workplace. Organizations that prioritize building a collaborative and supportive culture can enhance employee satisfaction, which in turn can lead to improved performance, reduced turnover, and a more positive work environment (Cardiff et al., 2020; Sabet et al. 2021; Jiang et al. 2020).

- RP: a positive relationship between PYYC and RP might seem counterintuitive at first glance, as it suggests that having a supportive network is associated with a higher risk of poverty. However, this interpretation might need clarification or a different perspective to fully understand the underlying dynamics. Typically, one would expect that having a strong network of support would decrease the risk of poverty by providing individuals with resources, emotional support, and opportunities that could help them avoid or escape poor economic conditions. In communities or groups where the risk of poverty is high, strong social support networks might develop as a necessary means of survival and mutual aid. In these contexts, the presence of PYYC is crucial and more prevalent because of the shared challenges. Therefore, the positive relationship does not imply that support networks cause poverty but rather that in environments where poverty risk is high, supportive networks are essential and become more visible or necessary. Individuals facing economic hardships often rely on extended family, friends, and community networks for support. This could include financial assistance, sharing of resources, or providing care services for each other. The strong presence of these support networks among those at risk of poverty highlights how essential they are for mitigating the immediate impacts of economic challenges. In areas with high poverty risks, the development of social capital—reflected in networks of mutual support and solidarity—can be particularly strong. People in these communities may often rely on one another to navigate economic difficulties, leading to a positive correlation between having people to rely on and experiencing a higher risk of poverty. It is important to clarify that the positive relationship here does not suggest that supportive networks increase the risk of poverty; rather, it reflects the importance and prevalence of support networks within communities where the risk of poverty is already high. These networks play a critical role in providing emotional, financial, and practical support, helping individuals and families cope with economic challenges and potentially aiding in poverty alleviation efforts (Lubbers et al., 2020; Gonzalez et al., 2020; Hill et al., 2021).

- SP: A positive relationship between PYCC and SP indicates that individuals who have a strong support network are more likely to be involved in social activities and community engagement. This correlation highlights the significant role that interpersonal relationships and social support play in encouraging active participation in social, cultural, and community events. Having supportive people in one's life can boost confidence and motivation to engage in social activities. Knowing that they have others to rely on for encouragement or companionship can make individuals more inclined to participate in social events and community activities. Social networks often serve as a valuable source of information about social activities, volunteer opportunities, and community events. People embedded in a network of supportive relationships are more likely to be informed about and encouraged to take part in these activities. Supportive networks frequently consist of individuals with shared interests and values. This common ground can foster group participation in social and community activities, leading to higher levels of social participation among the network's members. For some, participating in social activities can be challenging due to logistical, financial, or emotional barriers. Having people to rely on can provide the necessary support to overcome these obstacles, whether it is through sharing transportation, helping with costs, or offering emotional encouragement. Participation in community and social activities often leads to the strengthening of community ties and the building of new supportive relationships. This, in turn, creates a positive feedback loop where increased social participation enhances community cohesion, which further supports individual engagement. Engaging in social participation contributes to personal resilience and well-being, aspects that are supported and reinforced by having a reliable social network. The sense of belonging and purpose gained through active participation can improve mental health and overall life satisfaction. In summary, the positive correlation between having PYCC and SP underscores the importance of social support networks in fostering an active, engaged lifestyle. Supportive relationships not only encourage individuals to partake in social and community activities but also enhance the collective vibrancy and cohesiveness of communities as a whole (Singh and Moody, 2022; Zhao et al., 2022; Hu et al., 2022).

- There is a negative relationship between PYCC and the following variables namely:

- GT: A negative relationship between PYCC and GT suggests that in environments where individuals have strong, reliable support networks, there might be a lower level of trust towards society. When people have close-knit support networks, they may develop strong in-group bonds that inadvertently lead to reduced trust outside of their immediate circle. This "us vs. them" mentality strengthens ties within the group but can erode generalized trust in broader society. Individuals who rely heavily on a tight support network might feel less need to trust or engage with those outside their immediate circle. This self-sufficiency can reduce the perceived necessity to build trust with others in the wider community, leading to lower levels of generalized trust. In some cultures or communities, the emphasis on strong familial or community ties may come with an inherent wariness of external entities or individuals. This cultural norm can foster deep trust within specific groups while simultaneously lowering trust in broader society. Support networks often function as protective entities. When such networks are strong, individuals within them may become more risk-averse, viewing external interactions as unnecessary or potentially threatening, thereby reducing their level of generalized trust. In situations where individuals have experienced betrayal or exploitation by those outside their immediate support network, there may be a tendency to retreat into more trusted inner circles. Such experiences can significantly diminish one's propensity to trust people in general. Strong reliance on personal networks might be more pronounced in communities facing economic or social challenges, where trust in institutions and societal structures is low. In these contexts, the reliance on PYCC becomes a necessity rather than a choice, reflecting broader issues of systemic distrust. To address this negative relationship and promote generalized trust, interventions might focus on building bridges between different social groups, fostering inclusivity, and encouraging positive interactions across community divides. Efforts to strengthen social cohesion and trust in institutions, alongside promoting the benefits of diverse and open social networks, could also help counteract the tendency towards insularity and enhance generalized trust within the broader society (Igarashi and Hirashima, 2021; Growiec et al., 2022; Alecu, 2021).

- ER: a negative relationship between PYCC and the ER might initially seem counterintuitive, as strong social networks are often thought to contribute positively to job opportunities through connections and information sharing. However, this correlation could highlight underlying social and economic dynamics that merit closer examination. In communities with robust support systems, individuals might rely more on their network for financial and material support, possibly reducing the immediate necessity or urgency to seek employment. This could be particularly true in cultures or contexts where family or community support is expected and normalized over individual economic independence. Individuals with strong support networks might be more inclined to withdraw from the job market, especially after prolonged periods of unsuccessful job searching. The emotional and sometimes financial support they receive can afford them the luxury of not participating in the labour force, inadvertently affecting the employment rate. In some cases, strong support networks facilitate engagement in informal or non-traditional employment sectors not captured by standard employment statistics. For instance, individuals might participate in family businesses, informal caregiving, or community-based work, which may not be reflected in the official employment rate for ages 20-64. The relationship could also reflect regional economic conditions where strong community bonds are essential for survival due to a lack of formal employment opportunities. In such areas, the employment rate might be lower, not because social networks directly discourage work, but because the economy offers fewer formal job opportunities, and people rely more on each other for support. Areas with lower employment rates might see a higher out-migration of individuals seeking work elsewhere, leaving behind a population with stronger ties to the local community. These individuals may have a greater reliance on their social networks due to reduced economic opportunities in their locality. In societies with generous social welfare systems, individuals might not feel as compelled to find employment due to the availability of social support. This could lead to a situation where strong social networks exist alongside a lower employment rate, as the pressure to seek employment is mitigated by the welfare support. Addressing this negative relationship requires a multifaceted approach, focusing on enhancing economic opportunities, providing targeted employment services, and encouraging the positive aspects of social networks in facilitating job search and employment. Policies aimed at economic development, education, and training programs, as well as incentives for entrepreneurship, could help transform the potential of social networks into a driving force for increasing employment rates among the 20-64 age group (Zarova and Dubravskaya, 2020; Galbis et al., 2020).

- NII: a negative relationship between PYCC and NII suggests that in communities or societies where individuals have strong support networks, there tends to be lower income inequality. In societies with strong support networks, there is often a culture of sharing resources and providing mutual aid. This can help mitigate financial disparities by ensuring that those who are less well off receive support from their community, thereby reducing the gap between the highest and lowest earners. Strong social networks foster social cohesion, which can lead to more collective action aimed at addressing issues of inequality. Communities that are tightly knit are more likely to advocate for policies and practices that benefit the broader society, including welfare programs, progressive taxation, and other redistributive measures. Individuals with reliable support networks have better resilience in the face of economic downturns. The ability to rely on others for temporary financial assistance, job leads, or even entrepreneurial opportunities can prevent people from falling into poverty, which, on a larger scale, can contribute to reducing overall income inequality. Social networks increase an individual's social capital, providing access to information, resources, and opportunities that can lead to better employment and income prospects. When widespread across a society, this can lead to a more equitable distribution of economic resources, as more people can improve their socioeconomic status. Support networks often play a crucial role in educational achievement and occupational success by providing mentorship, advice, and connections. This support can level the playing field, especially for individuals from less privileged backgrounds, contributing to reduced income inequality. Societies with strong social bonds may also show higher levels of engagement in political and policy-making processes. This engagement can lead to the support and implementation of policies that aim to reduce income inequality, as there is a collective understanding of the importance of supporting every member of the community. In summary, the negative relationship between PYCC and NII highlights the role of social support networks in fostering economic equity. By sharing resources, advocating for fair policies, and providing individual support, these networks can help reduce the disparities in income distribution, contributing to a more balanced and cohesive society (Jackson, 2021; Ortiz and Bellotti, 2021).

- NRE: A negative relationship between PYCC and NRE suggests that in contexts where individuals have strong and reliable support networks, there tends to be a lower presence of irregular employment. Having a solid network can facilitate access to more stable and regular job opportunities through recommendations and information sharing. People with extensive social supports might be better positioned to find jobs with long-term contracts or full-time positions thanks to the shared information and opportunities within their networks. Support networks provide not just practical assistance in job searching but also emotional support throughout the process. This can reduce the level of stress associated with job precarity and increase individual resilience, making people less inclined to accept irregular jobs out of desperation or immediate necessity. Individuals supported by a robust network of contacts might have greater opportunities to access educational and training resources that enhance their employability in more stable and higher-quality jobs. Family or community support can facilitate investment in education and ongoing training, key elements for accessing more stable job opportunities. People with strong support networks might have a lower tolerance for precarious and irregular working conditions, feeling more secure in rejecting unsatisfactory job offers. The economic and emotional security provided by their social support could allow them to actively seek jobs that offer greater stability and satisfaction. In some cultures or social contexts, there is a strong expectation towards job stability as a social norm and a sign of success. Support networks in these contexts can, therefore, encourage and facilitate the pursuit of regular employment as the desirable path. However, it is important to note that this relationship can vary significantly depending on the socio-economic context, local labour market dynamics, and prevailing social policies. Interventions aimed at strengthening social support networks, along with inclusive labour policies that promote regular and quality employment, can help mitigate the negative effects of irregular employment on social cohesion and individual well-being (Belvis et al., 2022; Galanis et al., 2022; Yuan et al., 2022).

7. Policy Implications

8. Conclusions

References

- Akhtar, S. (2023). Behavioral economics and the problem of altruism: The review of Austrian economics. The Review of Austrian Economics, 1-20. [CrossRef]

- Aksoy, C. G., Cabrales, A., Dolls, M., Durante, R., & Windsteiger, L. (2021). Calamities, Common Interests, Shared Identity: What Shapes Altruism and Reciprocity? (No. tax-mpg-rps-2021-07). Max Planck Institute for Tax Law and Public Finance.

- Albanese, V. (2020). Il sentimento della crisi: un’analisi spaziale tra la Puglia e l’Emilia-Romagna. Semestrale di studi e ricerche di Geografia, 32(2), 23-37. [CrossRef]

- Alecu, A. I. (2021). Exploring the role of network diversity and resources in relationship to generalized trust in Norway. Social Networks, 66, 91-99. [CrossRef]

- Algieri, B., & Álvarez, A. (2023). Assessing the ability of regions to attract foreign tourists: The case of Italy. Tourism Economics, 29(3), 788-811. [CrossRef]

- Amati, V., Rivellini, G., & Zaccarin, S. (2015). Potential and effective support networks of young Italian adults. Social Indicators Research, 122, 807-831. [CrossRef]

- Anwar, S., Supriyanto, S., Budiarto, W., & Hargono, R. (2020). Relationship between Social Capital and Mental Health among the Older Adults in Aceh, Indonesia. Indian Journal of Forensic Medicine & Toxicology, 14(3). [CrossRef]

- Baldassarri, D., & Abascal, M. (2020). Diversity and prosocial behavior. Science, 369(6508), 1183-1187. [CrossRef]

- Baroncelli, S. (2022). How Fluid is the Special Statute of Autonomy of Trentino Alto Adige/South Tyrol? The influence of the Court of Justice of the EU, the Council of Europe and the Italian Constitutional Court on the Process of Implementation. europa ethnica-Zeitschrift für Minderheitenfragen, 79(1+ 2), 69-80. [CrossRef]

- Bartoll, X., & Ramos, R. (2020). Worked hours, job satisfaction and self-perceived health. Journal of Economic Studies, 48(1), 223-241. [CrossRef]

- Bartscher, A. K., Seitz, S., Siegloch, S., Slotwinski, M., & Wehrhöfer, N. (2021). Social capital and the spread of Covid-19: Insights from European countries. Journal of health economics, 80, 102531. [CrossRef]

- Bayer, Y. A. M. (2022). Age and Social Trust: Evidence from the United States. Available at SSRN 3596456.

- Beckmannshagen, M., & Schröder, C. (2022). Earnings inequality and working hours mismatch. Labour Economics, 76, 102184. [CrossRef]

- Belvis, F., Bolíbar, M., Benach, J., & Julià, M. (2022). Precarious employment and chronic stress: do social support networks matter?. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(3), 1909. [CrossRef]

- Benassi, C., & Vlandas, T. (2022). Trade unions, bargaining coverage and low pay: a multilevel test of institutional effects on low-pay risk in Germany. Work, Employment and Society, 36(6), 1018-1037. [CrossRef]

- Benner, C., & Pastor, M. (2021). Solidarity economics: Why mutuality and movements matter. John Wiley & Sons.

- Bertogg, A., & Koos, S. (2021). Socio-economic position and local solidarity in times of crisis. The COVID-19 pandemic and the emergence of informal helping arrangements in Germany. Research in Social Stratification and Mobility, 74, 100612. [CrossRef]

- Biggeri, M., Braito, L., Caloffi, A., & Zhou, H. (2022). Chinese entrepreneurs and workers at the crossroad: the role of social networks in ethnic industrial clusters in Italy. International Journal of Manpower, 43(9), 1-18. [CrossRef]

- Blasetti, E., & Garzonio, E. (2022). La representación social de los migrantes durante la pandemia de covid-19. Un estudio de caso italiano sobre narrativas hostiles y comunicación política visual. Perspectivas de la comunicación, 15(2), 139-185. [CrossRef]

- Bocci, L., D’Urso, P., & Vitale, V. (2021). Clustering of the Italian Regions Based on Their Equitable and Sustainable Well-Being Indicators: A Three-Way Approach. Social Indicators Research, 155(3), 995-1043. [CrossRef]

- Borraccino, A., Lazzeri, G., Kakaa, O., Bad’Ura, P., Bottigliengo, D., Dalmasso, P., & Lemma, P. (2020). The contribution of organised leisure-time activities in shaping positive community health practices among 13-and 15-year-old adolescents: results from the health behaviours in school-aged children study in italy. International journal of environmental research and public health, 17(18), 6637. [CrossRef]

- Börsch-Supan, A., Hunkler, C., & Weiss, M. (2021). Big data at work: Age and labor productivity in the service sector. The Journal of the Economics of Ageing, 19, 100319. [CrossRef]

- Bosch, M., González, S., & Silva Porto, M. T. (2021). Chasing Informality: Evidence from Increasing Enforcement in Large Firms in Peru (No. 11114). Inter-American Development Bank. [CrossRef]

- Canale, N., Vieno, A., Lenzi, M., Griffiths, M. D., Borraccino, A., Lazzeri, G., ... & Santinello, M. (2017). Income inequality and adolescent gambling severity: Findings from a large-scale Italian representative survey. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 1318. [CrossRef]

- Cappelen, A. W., Falch, R., Sørensen, E. Ø., & Tungodden, B. (2021). Solidarity and fairness in times of crisis. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 186, 1-11. [CrossRef]

- Cappiello, G., Giordani, F., & Visentin, M. (2020). Social capital and its effect on networked firm innovation and competitiveness. Industrial Marketing Management, 89, 422-430. [CrossRef]

- Cardiff, S., Sanders, K., Webster, J., & Manley, K. (2020). Guiding lights for effective workplace cultures that are also good places to work. International Practice Development Journal, 10(2). [CrossRef]

- Cattivelli, V. (2021). Planning peri-urban areas at regional level: The experience of Lombardy and Emilia-Romagna (Italy). Land use policy, 103, 105282. [CrossRef]

- Cerami, C., Santi, G. C., Galandra, C., Dodich, A., Cappa, S. F., Vecchi, T., & Crespi, C. (2020). Covid-19 outbreak in Italy: are we ready for the psychosocial and the economic crisis? Baseline findings from the PsyCovid study. Frontiers in psychiatry, 11, 556. [CrossRef]

- Chongyu, L. (2021). The influence of work salary and working hours on employee job satisfaction. In E3S Web of Conferences (Vol. 253, p. 02078). EDP Sciences. [CrossRef]

- Choquette-Levy, N., Wildemeersch, M., Santos, F. P., Levin, S. A., Oppenheimer, M., & Weber, E. U. (2024). Prosocial preferences improve climate risk management in subsistence farming communities. Nature Sustainability, 7(3), 282-293. [CrossRef]

- Cimagalli, F. (2020). Is there a place for altruism in sociological thought?. Human Arenas, 3(1), 52-66. [CrossRef]

- Corvo, E., & De Caro, W. (2020). COVID-19 and spontaneous singing to decrease loneliness, improve cohesion, and mental well-being: An Italian experience. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 12(S1), S247.

- Cugnata, F., Salini, S., & Siletti, E. (2021). Deepening well-being evaluation with different data sources: a Bayesian networks approach. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(15), 8110. [CrossRef]

- Cui, M. (2020). Introduction to the k-means clustering algorithm based on the elbow method. Accounting, Auditing and Finance, 1(1), 5-8.

- D’Adamo, I., & Gastaldi, M. (2023). Monitoring the performance of Sustainable Development Goals in the Italian regions. Sustainability, 15(19), 14094. [CrossRef]

- D’Urso, P., Alaimo, L. S., De Giovanni, L., & Massari, R. (2020). Well-being in the Italian regions over time. Social Indicators Research, 1-29. [CrossRef]

- D'Angelo, E., & Lilla, M. (2011). Social networking and inequality: the role of clustered networks. cambridge Journal of regions, economy and Society, 4(1), 63-77. [CrossRef]

- Deleidi, M., Paternesi Meloni, W., Salvati, L., & Tosi, F. (2021). Output, investment and productivity: the Italian North–South regional divide from a Kaldor–Verdoorn approach. Regional Studies, 55(8), 1376-1387. [CrossRef]

- Di Martino, P., Felice, E., & Vasta, M. (2020). A tale of two Italies:‘access-orders’ and the Italian regional divide. Scandinavian Economic History Review, 68(1), 1-22. [CrossRef]

- Di Nicola, P. (2011). Family, Personal Networks and Social Capital. Italian Sociological Review, 1(2), 11-11. [CrossRef]

- Drago, C. (2021). The analysis and the measurement of poverty: An interval-based composite indicator approach. Economies, 9(4), 145. [CrossRef]

- Dudziński, M., & Kaleta, J. (2021). An application of the interval estimation for the At-Risk-of-Poverty Rate assessment. Metody Ilościowe w Badaniach Ekonomicznych, 22(1), 14-28. [CrossRef]

- Erauskin, I. (2020). The labor share and income inequality: Some empirical evidence for the period 1990-2015. Applied Economic Analysis, 28(84), 173-195. [CrossRef]

- Eriawaty, E. T. D., Widjaja, S. U. M., & Wahyono, H. (2022). Rationality, Morality, Lifestyle And Altruism In Local Wisdom Economic Activities Of Nyatu Sap Artisans. Journal of Positive School Psychology, 5781-5797.

- Espi-Sanchis, G., Leibbrandt, M., & Ranchhod, V. (2022). Age, employment and labour force participation outcomes in COVID-era South Africa. Development Southern Africa, 39(5), 664-688. [CrossRef]

- Et-Taleby, A., Boussetta, M., & Benslimane, M. (2020). Faults Detection for Photovoltaic Field Based on K-Means, Elbow, and Average Silhouette Techniques through the Segmentation of a Thermal Image. International Journal of Photoenergy, 2020(1), 6617597. [CrossRef]

- Falcone, P. M., D'Alisa, G., Germani, A. R., & Morone, P. (2020). When all seemed lost. A social network analysis of the waste-related environmental movement in Campania, Italy. Political Geography, 77, 102114. [CrossRef]

- Fazari, E., & Musolino, D. (2023). Social farming in high mountain regions: The case of the Aosta Valley in Italy. Economia agro-alimentare, (2022/3). [CrossRef]

- Fazio, G., Giambona, F., Vassallo, E., & Vassiliadis, E. (2018). A measure of trust: The Italian regional divide in a latent class approach. Social Indicators Research, 140, 209-242. [CrossRef]

- Fernández GG, E., Lahusen, C., & Kousis, M. (2021). Does organisation matter? Solidarity approaches among organisations and sectors in Europe. Sociological Research Online, 26(3), 649-671. [CrossRef]

- Furfaro, E., Rivellini, G., & Terzera, L. (2020). Social support networks for childcare among foreign women in Italy. Social Indicators Research, 151, 181-204. [CrossRef]

- Galanis, P., Katsiroumpa, A., Vraka, I., Siskou, O., Konstantakopoulou, O., Katsoulas, T., & Kaitelidou, D. (2022). Relationship between social support and resilience among nurses: A systematic review. medRxiv, 2022-09. [CrossRef]

- Galbis, E. M., Wolff, F. C., & Herault, A. (2020). How helpful are social networks in finding a job along the economic cycle? Evidence from immigrants in France. Economic Modelling, 91, 12-32. [CrossRef]

- Gatto, M., Bertuzzo, E., Mari, L., Miccoli, S., Carraro, L., Casagrandi, R., & Rinaldo, A. (2020). Spread and dynamics of the COVID-19 epidemic in Italy: Effects of emergency containment measures. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 117(19), 10484-10491. [CrossRef]

- Gentile, I., Iorio, M., Zappulo, E., Scotto, R., Maraolo, A. E., Buonomo, A. R., ... & Federico II COVID-Team. (2022). COVID-19 Post-Exposure Evaluation (COPE) study: assessing the role of socio-economic factors in household SARS-CoV-2 transmission within Campania Region (Southern Italy). International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(16), 10262. [CrossRef]

- Giambona, F., Khalawi, A., Buzzigoli, L., Grassini, L., & Martelli, C. (2021). Big data analysis and labour market: an analysis of Italian online job vacancies data. ASA 2021, 105. [CrossRef]

- Gianmoena, L., & Rios, V. (2024). The diffusion of COVID-19 across Italian provinces: a spatial dynamic panel data approach with common factors. Regional Studies, 58(2), 285-305. [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez De La Rocha, M. (2020). Of morals and markets: Social exchange and poverty in contemporary urban Mexico. The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 689(1), 26-45. [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, R., Fuentes, A., & Muñoz, E. (2020). On social capital and health: the moderating role of income inequality in comparative perspective. International Journal of Sociology, 50(1), 68-85. [CrossRef]

- Growiec, K., Growiec, J., & Kamiński, B. (2022). it matterS whom you Know: mapping the linKS between Social capital, truSt and willingneSS to cooperate. Studia Socjologiczne, (2), 59-83. [CrossRef]

- Gualda, E. (2022). Altruism, solidarity and responsibility from a committed sociology: contributions to society. The American Sociologist, 53(1), 29-43. [CrossRef]

- Hill, K., Hirsch, D., & Davis, A. (2021). The role of social support networks in helping low income families through uncertain times. Social Policy and Society, 20(1), 17-32. [CrossRef]

- Hu, G., Wang, J., Laila, U., Fahad, S., & Li, J. (2022). Evaluating households’ community participation: Does community trust play any role in sustainable development?. Frontiers in Environmental Science, 10, 951262. [CrossRef]

- Igarashi, T., & Hirashima, T. (2021). Generalized trust and social selection process. Frontiers in Communication, 6, 667082. [CrossRef]

- Ilmakunnas, I. (2022). The magnitude and direction of changes in age-specific at-risk-of-poverty rates: an analysis of patterns of poverty trends in Europe in the mid-2010s. Journal of International and Comparative Social Policy, 38(1), 71-91. [CrossRef]

- Ippolito, M., & Cicatiello, L. (2019). Political instability, economic inequality and social conflict: The case in Italy. Panoeconomicus, 66(3), 365-383. [CrossRef]

- Islam, S., & Safavi, M. (2020). Wage inequality, firm size and Gender: The case of Canadá. Archive of Business research, 8(2), 27-37. [CrossRef]

- Jackson, M. O. (2021). Inequality's economic and social roots: the role of social networks and homophily. Available at SSRN 3795626.

- Janietz, C., Bol, T., & Lancee, B. (2023). Temporary employment and wage inequality over the life course. European Sociological Review. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z., Di Milia, L., Jiang, Y., & Jiang, X. (2020). Thriving at work: A mentoring-moderated process linking task identity and autonomy to job satisfaction. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 118, 103373. [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, S., Oliveira, M., Vassillo, C., Orlandini, G., & Zucaro, A. (2022). Social and Environmental Assessment of a Solidarity Oriented Energy Community: A Case-Study in San Giovanni a Teduccio, Napoli (IT). Energies, 15(4), 1557. [CrossRef]

- Kalland, M., Salo, S., Vincze, L., Lipsanen, J., Raittila, S., Sourander, J., Salvén-Bodin, M., & Pajulo, M. (2022). Married and cohabiting Finnish first-time parents: Differences in wellbeing, social support and infant health. Social Sciences. [CrossRef]

- Kawano, E. (2020). Solidarity economy: Building an economy for people and planet. In The new systems reader (pp. 285-302). Routledge.

- Kebe, M., Kpanzou, T. A., Manou-Abi, S. M., & Sisawo, E. (2023). Kernel estimation of the Quintile Share Ratio index of inequality for heavy-tailed income distributions. European Journal of Pure and Applied Mathematics, 16(4), 2509-2543. [CrossRef]

- Khatskevich, A., & Alexandrov, P. (2021). Comparative analysis of the cultural preferences of Orthodox and student (secular) youth. Nauka. me, (4), 42-48. [CrossRef]

- Konarik, V., & Melecky, A. (2022). Religiosity as a Driving Force of Altruistic Economic Preferences. International Journal of Business and Applied Social Science, 10-29. [CrossRef]

- Laureti, L., Costantiello, A., & Leogrande, A. (2022). Satisfaction with the Environmental Condition in the Italian Regions between 2004 and 2020. Available at SSRN 4061708. [CrossRef]

- Leogrande, A., Costantiello, A., & Leogrande, D. (2023). The Socio-Economic Determinants of the Number of Physicians in Italian Regions. Available at SSRN 4560149.

- Leogrande, A., Costantiello, A., Leogrande, D., & Anobile, F. (2023). Beds in Health Facilities in the Italian Regions: A Socio-Economic Approach. Available at SSRN 4577029.

- Li, X., Tian, L., & Xu, J. (2020). Missing social security contributions: the role of contribution rate and corporate income tax rate. International Tax and Public Finance, 27(6), 1453-1484. [CrossRef]

- Lubbers, M. J., García, H. V., Castaño, P. E., Molina, J. L., Casellas, A., & Rebollo, J. G. (2020). Relationships stretched thin: Social support mobilization in poverty. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 689(1), 65-88. [CrossRef]

- Lum, T. Y. (2022). Social capital and geriatric depression in the Asian context. International Psychogeriatrics, 34(8), 671-673. [CrossRef]

- Mangone, E. (2020). Beyond the dichotomy between altruism and egoism: Society, relationship, and responsibility. IAP.

- Mangone, E. (2022). A new sociality for a solidarity-based society: the altruistic relationships. Derecho y Realidad, 20(40), 15-32. [CrossRef]

- Marinescu, I., Qiu, Y., & Sojourner, A. (2021). Wage inequality and labor rights violations (No. w28475). National Bureau of Economic Research.

- Matricano, D. (2022). Economic and social development generated by innovative startups: Does heterogeneity persist across Italian macro-regions?. Economics of Innovation and New Technology, 31(6), 467-484. [CrossRef]

- Matthaei, J. (2020). Thinking beyond capitalism: social movements, revolution, and the solidarity economy. In A Research Agenda for Critical Political Economy (pp. 209-224). Edward Elgar Publishing. [CrossRef]

- Maugeri, A., Barchitta, M., Basile, G., & Agodi, A. (2021). Applying a hierarchical clustering on principal components approach to identify different patterns of the SARS-CoV-2 epidemic across Italian regions. Scientific reports, 11(1), 7082. [CrossRef]

- Milani, F. (2021). COVID-19 outbreak, social response, and early economic effects: a global VAR analysis of cross-country interdependencies. Journal of population economics, 34(1), 223-252. [CrossRef]

- Milano, M., & Cannataro, M. (2020). Statistical and network-based analysis of Italian COVID-19 data: communities detection and temporal evolution. International journal of environmental research and public health, 17(12), 4182. [CrossRef]

- Monte, A., & Schoier, G. (2022). A multivariate statistical analysis of equitable and sustainable well-being over time. Social Indicators Research, 161(2), 735-750. [CrossRef]

- Nwaubani, J. C., Ohia, A. N., Peace, O., Adaugo, U. C., Ezeji, U. M., & Ezechukwu, C. U. (2020). Evaluation of Total Employment Rate Aged 15-64 in EU15. European Journal of Business and Management Research, 5(5). [CrossRef]

- Ødegård, G., & Fladmoe, A. (2020). Are immigrant youth involved in voluntary organizations more likely than their non-immigrant peers to be engaged in politics? Survey evidence from Norway. Acta sociologica, 63(3), 267-283. [CrossRef]

- Ortiz, F., & Bellotti, E. (2021). The impact of life trajectories on retirement: socioeconomic differences in social support networks. Social Inclusion, 9(4), 327-338. [CrossRef]

- Palmentieri, S. (2023). Post-pandemic scenarios. The role of the Italian National Recovery and Resilience Plan (NRRP) in reducing the gap between the Italian Central-Northern regions and southern ones. AIMS Geosciences, 9(3), 555-577. [CrossRef]

- Pearlman, S. (2023). Solidarity Over Charity: Mutual Aid as a Moral Alternative to Effective Altruism. Kennedy Institute of Ethics Journal, 33(2), 167-199. [CrossRef]

- Pedersen, K., Jensen, R. R., Hall, L. K., Cutler, M. C., Transtrum, M. K., Gee, K. L., & Lympany, S. V. (2023). K-means clustering of 51 geospatial layers identified for use in continental-scale modeling of outdoor acoustic environments. Applied Sciences, 13(14), 8123. [CrossRef]

- Petraglia, C., & Scalera, D. (2021). Economy and industry in Campania: which policy for lasting growth?. Rivista internazionale di scienze sociali: 2, 2021, 221-251. [CrossRef]

- Porreca, A., Cruz Rambaud, S., Scozzari, F., & Di Nicola, M. (2019). A fuzzy approach for analysing equitable and sustainable well-being in Italian regions. International Journal of Public Health, 64, 935-942. [CrossRef]

- Power, S. (2020). Civil Society through the lifecourse. In Civil Society through the Lifecourse (pp. 203-214). Bristol University Press. [CrossRef]

- Preetz, R. (2022). Dissolution of non-cohabiting relationships and changes in life satisfaction and mental health. Frontiers in Psychology, 13. [CrossRef]

- Rapp, I., & Stauder, J. (2020). Mental and physical health in couple relationships: Is it better to live together? European Sociological Review. [CrossRef]

- Rocha, J. L. M., Zela, M. A. C., Torres, N. I. V., & Medina, G. S. (2021). Analogy of the application of clustering and K-means techniques for the approximation of values of human development indicators. International Journal of Advanced Computer Science and Applications, 12(9). [CrossRef]

- Rosini, M. (2022). Statute of Trentino-Alto Adige/Südtirol and "major favour clause": More or less autonomy? An evaluation 20 years after the reform of Title V of the Constitution. Europa Ethnica.

- Sabbatucci, M., Odone, A., Signorelli, C., Siddu, A., Silenzi, A., Maraglino, F. P., & Rezza, G. (2022). Childhood immunisation coverage during the COVID-19 epidemic in Italy. Vaccines, 10(1), 120. [CrossRef]

- Sabet, S., Goodarzvand Chegini, M., Rezaei Klidbari, H., & Rezaei Dizgah, M. (2021). Designing a Model of Human Resource Mentoring System Based on a Mixed Approach, With the Aim of Increasing Productivity. Journal of System Management, 7(2), 205-229. [CrossRef]

- Salem, M. B. (2020). “God loves the rich.” The economic policy of Ennahda: liberalism in the service of social solidarity. Politics and Religion, 13(4), 695-718. [CrossRef]

- Salustri, A. (2021). Social and solidarity economy and social and solidarity commons: Towards the (re) discovery of an ethic of the common good?. Annals of Public and Cooperative Economics, 92(1), 13-32. [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Sánchez, N., & Fernández Puente, A. C. (2021). Public versus private job satisfaction. Is there a trade-off between wages and stability?. Public Organization Review, 21(1), 47-67. [CrossRef]

- Sanfelici, M. (2021). The impact of the COVID-19 crisis on marginal migrant populations in Italy. American Behavioral Scientist, 65(10), 1323-1341. [CrossRef]

- Savona, E. U., Calderoni, F., Campedelli, G. M., Comunale, T., Ferrarini, M., & Meneghini, C. (2020). The criminal careers of Italian mafia members. Understanding recruitment to organized crime and terrorism, 241-267. [CrossRef]

- Shahapure, K. R., & Nicholas, C. (2020, October). Cluster quality analysis using silhouette score. In 2020 IEEE 7th international conference on data science and advanced analytics (DSAA) (pp. 747-748). IEEE. [CrossRef]

- Shook, J., Goodkind, S., Engel, R. J., Wexler, S., & Ballentine, K. L. (2020). Moving beyond poverty: Effects of low-wage work on individual, social, and family well-being. Families in Society, 101(3), 249-259. [CrossRef]

- Siemoneit, A. (2023). Merit first, need and equality second: hierarchies of justice. International Review of Economics, 70(4), 537-567. [CrossRef]

- Singh, M. K., & Moody, J. (2022). Do social capital and networks facilitate community participation?. International Journal of Sociology and Social Policy, 42(5/6), 385-398. [CrossRef]

- Slobodenyuk, E. D., & Mareeva, S. V. (2020). Relative poverty in Russia: Evidence from different thresholds. Social Indicators Research, 151(1), 135-153. [CrossRef]

- Sobering, K. (2021). Survival finance and the politics of equal pay. The British Journal of Sociology, 72(3), 742-756. [CrossRef]

- Spaulonci Chiachia Matos de Oliveira, B. C. (2022). Homo Colaboratus Birth Within Complex Consumption. In The Palgrave Handbook of Global Social Problems (pp. 1-10). Cham: Springer International Publishing. [CrossRef]

- Stansfeld, S., & Khatib, Y. (2011). Social Support and Social Networks. In International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences (pp. 119-123).

- Stanzani, S. (2020). Trust and civic engagement in the Italian COVID-19 Lockdown. Italian Sociological Review, 10(3S), 917-935.

- Surinov, A., & Luppov, A. (2020). Income inequality in Russia. Measurement based on equivalent income. HSE Economic Journal, 24(4), 539-571. [CrossRef]

- Travlou, P., & Bernát, A. (2022). Solidarity and care economy in times of ‘crisis’: A view from Greece and Hungary between 2015 and 2020. In The Sharing Economy in Europe: Developments, Practices, and Contradictions (pp. 207-237). Cham: Springer International Publishing. [CrossRef]

- Tuominen, M., & Haanpää, L. (2022). Young people’s well-being and the association with social capital, ie Social Networks, Trust and Reciprocity. Social indicators research, 159(2), 617-645. [CrossRef]

- van Geest, P. (2021). The Indispensability of Theology for Enriching Economic Concepts. In Morality in the Marketplace (pp. 68-88). Brill. [CrossRef]

- Ventura, L. (2023). The social enterprise movement and the birth of hybrid organisational forms as policy response to the growing demand for firm altruism. The international handbook of Social Enterprise Law. Cham: Springer, 9-26. [CrossRef]

- Volosevici, D., & Grigorescu, D. (2021). Individual, employers and organizational citizenship behaviour. A Journal of Social and Legal, 43, 50. [CrossRef]

- Yuan, C. T., Lai, A. Y., Benishek, L. E., Marsteller, J. A., Mahabare, D., Kharrazi, H., & Dy, S. M. (2022). A double-edged sword: The effects of social network ties on job satisfaction in primary care organizations. Health care management review, 47(3), 180-187. [CrossRef]

- Yucel, D., & Latshaw, B. A. (2022). Mental health across the life course for men and women in married, cohabiting, and living apart together relationships. Journal of Family Issues. [CrossRef]

- Zambon, I., Rontos, K., Reynaud, C., & Salvati, L. (2020). Toward an unwanted dividend? Fertility decline and the North–South divide in Italy, 1952–2018. Quality & Quantity, 54, 169-187. [CrossRef]

- Zarova, E. V., & Dubravskaya, E. I. (2020). The Random Forest Method in Research of Impact of Macroeconomic Indicators of Regional Development on Informal Employment Rate. ÂÎÏÐÎÑÛ ÑÒÀÒÈÑÒÈÊÈ, 27(6), 38. [CrossRef]

- Zhao: D., Li, G., Zhou, M., Wang, Q., Gao, Y., Zhao, X., ... & Li, P. (2022). Differences according to sex in the relationship between social participation and well-being: a network analysis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(20), 13135. [CrossRef]

| Macro-themes | References |

|---|---|

| Behavioral Economics and Altruism | Akhtar (2023); Aksoy et al. (2021); Eriawaty et al. (2022); Konarik and Melecky (2022); Mangone (2020); Mangone (2022) |

| Solidarity Economics and Social Movements | Benner and Pastor (2021); Matthaei (2020); Kawano (2020); Salustri (2021); Pearlman (2023); Ventura (2023) |

| Diversity, Reciprocity, and Prosocial Behavior | Baldassarri and Abascal (2020); Cimagalli (2020); Cappelen et al. (2021); Choquette-Levy et al. (2024); Spaulonci Chiachia Matos de Oliveira (2022) |

| Socioeconomic Position and Solidarity in Times of Crisis | Bertogg and Koos (2021); Fernández et al. (2021); Travlou and Bernát (2022); Salem (2020) |

| Economic Philosophy and Homo Economicus | Albanese (2021); Johnson (2020); Silvestri and Kesting (2021) |

| Morality and Economics | van Geest (2021); Volosevici and Grigorescu (2021); Siemoneit (2023); Gualda (2022) |

| Variables | Acronym | Definition | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| People you can count on | PYCC | Percentage of people aged 14 and over who have non-cohabiting relatives (in addition to parents, children, brothers, sisters, grandparents, grandchildren), friends or neighbors they can count on out of all people aged 14 and over. In contemporary society, non-cohabiting relationships serve an equally vital function in providing emotional, social, and practical support. The statistic on the percentage of people aged 14 and over who have non-cohabiting relatives, friends, or neighbors they can rely on reflects the broader network of interpersonal connections that extend beyond immediate family members, such as parents, children, or siblings. These relationships often contribute significantly to individuals’ mental well-being and promote greater community cohesion. A higher percentage of individuals with such connections could be interpreted as indicative of stronger community bonds and increased social capital, both of which are essential for fostering a sense of belonging and collective security. Those with access to non-cohabiting relatives or friends are likely to demonstrate greater resilience when facing personal challenges or crises, as they can draw upon a more extensive range of resources for support. Conversely, a lower percentage may signal rising social isolation, a condition associated with negative health outcomes, including depression and anxiety. Furthermore, as family structures evolve and urbanization progresses, friendships and neighborhood ties become increasingly critical sources of support. Nevertheless, this statistic does not fully capture the quality or depth of these relationships, which can vary considerably. Simply knowing someone who can be relied upon does not necessarily guarantee active, reciprocal support. Despite these limitations, the statistic remains a valuable indicator of social well-being, underscoring the importance of fostering wider community connections in a time of shifting familial dynamics (Kalland et al., 2022; Preetz, 2022; Yucel and Latshaw, 2022; Rapp and Stauder, 2020). | ISTAT-BES |

| Low paid employees | LPE | Percentage of employees with an hourly wage lower than 2/3 of the median hourly wage out of all employees. This measure is essential for evaluating wage inequality and understanding the degree to which certain segments of workers face economic vulnerability. A high percentage of employees earning less than two-thirds of the median wage signals significant income disparity, potentially reflecting systemic issues in wage distribution. From an economic standpoint, a higher proportion of low-wage workers often correlates with diminished employee bargaining power, which may stem from labor market deregulation, limited union representation, or an increase in precarious employment arrangements. Such workers are more likely to experience financial instability, with restricted access to essential services such as healthcare, housing, and education. This dynamic can perpetuate cycles of poverty and exacerbate social inequality. Moreover, the prevalence of low-wage employment has broader implications for overall economic productivity. Employees earning lower wages may suffer from reduced job satisfaction and motivation, potentially leading to higher turnover rates and lower organizational efficiency. Employers, in turn, may face difficulties in retaining skilled workers, thereby hindering long-term business growth and competitiveness. Conversely, a lower percentage of employees earning below this threshold suggests a more equitable wage distribution, with a larger portion of workers receiving compensation that reflects fair market value. This statistic thus serves as a critical indicator for policymakers and economists, emphasizing the need for interventions to address wage disparities and foster more inclusive economic growth (Islam and Safavi, 2020; Marinescu and Sojourner, 2021; Janietz et al., 2023; Beckmannshagen and Schröder, 2022). | ISTAT-BES |

| Satisfaction with the work done | SWWD | Percentage of employed people who expressed an average satisfaction score between 8 and 10 for the following aspects of their work: earnings, career opportunities, number of hours worked, job stability, distance from home to work, interest in work. The aspects evaluated—earnings, career opportunities, working hours, job stability, commute, and interest in work—are fundamental elements that shape the quality of an individual's work experience and, by extension, their broader life satisfaction. A high percentage of workers expressing satisfaction in these areas suggests that the labor market is effectively addressing employees' needs and expectations. Satisfaction with earnings and career opportunities, for instance, reflects not only financial security but also the potential for upward mobility and professional development, both of which are critical to sustaining motivation and retaining talent over the long term. Similarly, high satisfaction with working hours and job stability points to a healthy work-life balance and a sense of economic security, factors closely linked to improved mental and emotional well-being.ΦMoreover, satisfaction with the commute, particularly the distance from home to work, is a key determinant of job satisfaction. Shorter or more manageable commutes are associated with reduced stress levels and greater overall job contentment. Additionally, high levels of interest in one's work indicate that employees find their roles meaningful and engaging, which can foster increased productivity and a stronger sense of purpose within the organization. Conversely, a lower percentage of satisfaction across these dimensions may indicate underlying structural deficiencies in the workplace, such as inadequate compensation, limited career advancement opportunities, or poor work-life balance. Addressing these issues is crucial for improving workforce morale and enhancing organizational performance. Consequently, this statistic offers valuable insights for both employers and policymakers, guiding efforts to create more supportive and fulfilling work environments (Chongyu, 2021; Bartoll and Ramos, 2020; Sánchez-Sánchez and Fernández Puente, 2021). | ISTAT-BES |

| Risk of poverty | RP | Percentage of people who live in families with an equivalent net incomeΦlower than a risk-of-poverty threshold, set at 60% of the median of the individual distribution of equivalent net income. The income reference year is the calendar year preceding the survey year. This threshold measures the proportion of people at risk of poverty relative to the median income, offering a nuanced understanding of relative deprivation within a society. A high percentage of individuals falling below this threshold points to significant income disparities and socioeconomic stratification. Families with incomes below this level frequently face challenges in meeting essential needs such as housing, healthcare, and education, restricting their access to resources that facilitate social mobility. The use of "equivalent net income," which adjusts for household size and composition, allows for a more precise reflection of financial well-being compared to the median income standard. Living below this threshold often entrenches families in cycles of poverty, as limited financial resources hinder investments in critical areas like education and health, thereby reducing future earnings potential. Prolonged exposure to these conditions can result in negative long-term outcomes, including poorer health, lower educational attainment, and diminished overall life quality. Addressing the high proportion of individuals living in poverty requires targeted social policies aimed at wealth redistribution and the provision of comprehensive social safety nets. This statistic provides essential insights for policymakers, highlighting the need for interventions that promote a more equitable distribution of income and reduce the risk of poverty within the population (Ilmakunnas, 2022; Dudziński and Kaleta, 2021; Slobodenyuk and Mareeva, 2020; Surinov and Luppov, 2020). | ISTAT-BES |

| Social participation | SP | People aged 14 and over who in the last 12 months have carried out at least one social participation activity out of the total number of people aged 14 and over. The activities considered are: participating in meetings or initiatives (cultural, sports, recreational, spiritual) organized or promoted by parishes, congregations or religious or spiritual groups; participating in meetings of cultural, recreational or other associations; participating in meetings of environmental, civil rights, peace associations; participating in meetings of trade union organizations; participating in meetings of professional or trade associations; participating in meetings of political parties; carrying out free activities for a party; paying a monthly or periodic fee for a sports club. Social participation, encompassing activities such as involvement in cultural, recreational, spiritual, political, and trade organizations, plays a pivotal role in promoting social cohesion, enhancing civic responsibility, and fostering individual well-being. Participation in such activities reflects the degree to which individuals engage in collective actions that contribute to the formation and maintenance of social capital. A high percentage of individuals involved in these activities suggests a robust civil society characterized by active civic engagement and the presence of strong social networks. Participation in organized events, such as religious gatherings, trade union meetings, or political party activities, allows individuals to forge social connections, share collective values, and collaborate in pursuit of common objectives. This fosters a sense of belonging, strengthens communal bonds, and contributes to the overall stability of the social and political environment. Conversely, a low level of social participation may indicate social disengagement, which can erode social capital and diminish individuals' sense of belonging and collective efficacy. Barriers such as economic inequality, time constraints, or geographic inaccessibility may inhibit participation, further contributing to social isolation. This statistic provides critical insights for policymakers and social organizations, highlighting the importance of fostering inclusive opportunities for civic engagement. Developing policies and initiatives that promote broader social participation is crucial for cultivating a more cohesive, engaged, and resilient society (Power, 2020; Ødegård and Fladmoe, 2020; Borraccino et al., 2020; Khatskevich and Alexandrov, 2021). | ISTAT-BES |

| Generalized trust | GT | Percentage of people aged 14 and over who believe, that most people are trustworthy out of the total number of people aged 14 and over. Trust in others underpins the development of strong interpersonal relationships, community cohesion, and the accumulation of social capital. A high percentage of individuals expressing trust in others suggests the presence of robust social bonds, enhanced cooperation, and a lower likelihood of social fragmentation. Social trust is a fundamental element in the effective functioning of democratic institutions and economic systems. In societies where trust is prevalent, there tends to be greater cooperation in collective efforts, smoother economic transactions, and increased civic participation. This high level of trust reduces the need for costly oversight and enforcement mechanisms, thereby promoting efficiency and mutual respect within both public and private sectors. Additionally, social trust is positively correlated with mental health and well-being, as individuals in high-trust environments often feel more secure and supported by their communities. In contrast, a low percentage of individuals perceiving others as trustworthy may indicate rising social fragmentation, individualism, or growing skepticism towards institutions. This lack of trust can result in heightened social tensions, reduced community engagement, and an increased reliance on regulatory mechanisms to maintain social order. Moreover, diminished trust can undermine civic and political participation, weakening democratic institutions over time (Tuominen and Haanpää, 2022; Bayer, 2022; Lum, 2022; Anwar et al, 2020). | ISTAT-BES |

| Employment rate (20-64 years) | ER | Percentage of employed people aged 20-64 on the population aged 20-64. This indicator provides an understanding of the proportion of the working-age population actively engaged in employment, thereby offering valuable insights into both employment levels and overall economic productivity. A high percentage reflects a robust labor market with significant employment opportunities, suggesting favorable economic conditions. Conversely, a low percentage may point to labor market challenges, such as high unemployment rates, underemployment, or structural barriers that inhibit individuals from securing stable employment. The 20-64 age group represents the prime working years, making their employment rate essential for economic performance and growth. Employment within this demographic is not only a driver of economic output but also supports the sustainability of social security systems, as employed individuals contribute to pensions, healthcare, and other public services. High employment rates within this age group are especially critical in aging societies, where a smaller working population must support a growing number of retirees. Moreover, employment within this age group is strongly associated with social inclusion and individual well-being. Stable employment contributes to financial security, access to healthcare, and a sense of purpose and societal contribution. A decline in employment rates among this demographic can increase dependency ratios, placing pressure on public resources and social welfare systems, as fewer workers support a larger non-working population (Börsch-Supan, et al. 2021; Nwaubani et al., 2020; Espi-Sanchis et al., 2022). | ISTAT-BES |

| Net income inequality (s80/s20) | NII | Ratio between the total equivalent income received by the 20% of the population with the highest income and that received by the 20% of the population with the lowest income. This ratio, often referred to as the income quintile share ratio, provides insight into the distribution of wealth and the degree of economic disparity between the wealthiest and the poorest segments of the population. A higher ratio indicates greater inequality, where the top 20% of earners capture a disproportionately large share of the total income relative to the bottom 20%. This form of economic imbalance can have profound implications for social cohesion, political stability, and long-term economic growth. Income inequality, as reflected in this ratio, often results from a combination of structural factors, including disparities in education, access to employment, capital accumulation, and the concentration of wealth. High inequality can lead to reduced social mobility, where individuals in lower-income brackets face significant barriers to improving their economic status. It may also exacerbate social divisions, fostering distrust and resentment, which can destabilize political institutions and erode democratic processes. Furthermore, extreme income inequality has been shown to negatively impact economic performance. Concentrated wealth limits overall consumer demand, as lower-income households spend a larger share of their income on consumption. This disparity can hinder economic growth, as wealthier individuals tend to save or invest, reducing immediate economic activity. Thus, this ratio serves as a vital tool for policymakers to assess the need for redistributive policies, such as progressive taxation or social welfare programs, to mitigate inequality and promote more inclusive economic development (Kebe et al., 2023; Erauskin, 2020). | ISTAT-BES |

| Non-regularly employed | NRE | Percentage of employed people who do not comply with the current legislation on labor, tax and social security contributions on the total employed people. This non-compliance has significant economic, social, and legal implications. A high percentage of non-compliance suggests widespread informal employment, where workers and employers evade labor laws, tax obligations, and social security contributions. This phenomenon undermines the formal economy by depriving governments of essential tax revenues and social security contributions, which are vital for funding public services and welfare programs. From a social perspective, non-compliance affects both workers and the broader population. Workers who operate outside formal regulations often lack access to critical protections such as health benefits, pension schemes, and unemployment insurance. This lack of coverage increases their vulnerability to economic shocks and long-term poverty, especially in cases of illness, unemployment, or old age. In addition, non-compliant employment exacerbates income inequality, as informal workers typically earn lower wages and have less job security than their counterparts in the formal sector. Furthermore, widespread non-compliance creates unfair competition in the labor market, where businesses that adhere to legal standards face disadvantages compared to those that avoid taxes and regulations. This can lead to a "race to the bottom," where businesses are incentivized to cut costs through non-compliance rather than improving productivity or working conditions (Li et al., 2020; Bosch et al., 2021). | ISTAT-BES |

| Estimation of the Value of PYCC | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | const | ER | LPE | SWWD | NII | RP | NRE | SP | GT | |

| Pooled OLS | Coefficient | 30.482 | −0.523337 | 1.85435 | 0.941618 | −3.29518 | 0.284913 | −1.29779 | 2.29992 | −0.859506 |

| Std. Error | 3.30334 | 0.238503 | 0.207111 | 0.321446 | 1.01386 | 0.129974 | 0.412513 | 0.076236 | 0.119062 | |

| p-value | <0.0001 | 0.0288 | <0.0001 | 0.0036 | 0.0013 | 0.029 | 0.0018 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | |

| *** | ** | *** | *** | *** | ** | *** | *** | *** | ||

| Fixed Effects | Coefficient | 34.2525 | −0.650720 | 2.21164 | 1.08443 | −4.09917 | 0.485842 | −1.70579 | 2.37634 | −1.03985 |

| Std. Error | 4.00646 | 0.260433 | 0.217229 | 0.353539 | 1.30129 | 0.199375 | 0.539081 | 0.075975 | 0.124273 | |

| p-value | <0.0001 | 0.0129 | <0.0001 | 0.0023 | 0.0018 | 0.0153 | 0.0017 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | |

| *** | ** | *** | *** | *** | ** | *** | *** | *** | ||

| Random Effects | Coefficient | 33.7664 | −0.595876 | 2.08993 | 1.01667 | −3.72735 | 0.37483 | −1.60997 | 2.35364 | −0.976760 |

| Std. Error | 3.78998 | 0.245898 | 0.20925 | 0.332295 | 1.14466 | 0.157082 | 0.477984 | 0.074682 | 0.119853 | |

| p-value | <0.0001 | 0.0154 | <0.0001 | 0.0022 | 0.0011 | 0.017 | 0.0008 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | |

| *** | ** | *** | *** | *** | ** | *** | *** | *** | ||

| WLS | Coefficient | 31.0799 | −0.516237 | 1.86797 | 0.920011 | −3.40669 | 0.313577 | −1.33956 | 2.33801 | −0.902347 |

| Std. Error | 3.1949 | 0.237616 | 0.199949 | 0.321138 | 0.958205 | 0.122202 | 0.385256 | 0.07431 | 0.118442 | |

| p-value | <0.0001 | 0.0304 | <0.0001 | 0.0044 | 0.0004 | 0.0107 | 0.0006 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | |

| *** | ** | *** | *** | *** | ** | *** | *** | *** | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).