+ Shared the first authorship.

1. Introduction

Severe burn injuries not only significantly diminish patients’ quality of life but also come with an average cost of approximately

$300,000 per patient [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7]. Recognized as a major health concern, severe burns inflict more distress than any other form of trauma [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8]. Deep burns, and especially third degree (3

o) burns, can destroy full thickness skin, including the epidermis, dermis, and hypodermis, as well as blood vessels [

9,

10,

11,

12], leading to scarring (causing morbidity and contracture/disfigurement) [

13] and delayed healing [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11]. Traditional treatment for 3

o burns involves skin grafts taken from unburned areas of the patient’s body. However, this harvesting of healthy skin creates additional wounds and can impair function at the donor sites. Moreover, the grafting procedures can be extensive, fraught with risks, expensive, and prone to causing further physical decline. Therefore, the development of a treatment that is safe, user-friendly, and effective in regenerating skin and repairing 3

o burns and that can overcome the drawbacks of currently available treatments—is of paramount importance. Despite the use of current treatment technologies, considerable shortcomings remain in achieving proper wound healing of 3

o burns, highlighting the critical need for more efficacious treatment methods [

14].

Wound healing depends on many factors, including amino acid-based growth factors and cytokines; however, the importance of specific lipid-derived molecules for tissue regeneration in wound healing, resolution of inflammation, and injury repair is now recognized [

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31]. These lipid factors, which include resolvins, neuroprotectins/protectins, maresins, and elovanoids, function as signaling molecules that resolve inflammation and injury, protect against infection, and/or induce the regeneration of cells and tissue [

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

32,

33,

34,

35,

36,

37,

38,

39,

40,

41]. We have identified the molecular structure, biogenesis pathways, and pro-regenerative functions of 14

S,21

R-dihydroxy-docosa-4

Z,7

Z,10

Z,12

E,16

Z,19

Z-hexaenoic acid (14

S,21

R-diHDHA), a docosahexaenoic acid-derived lipid mediator [

16,

17]. This small molecule is a specialized pro-resolving mediator (SPM) similar to resolvins and protectins/neuroprotectins, as it is produced by macrophages and possesses inflammation- and wound-resolving properties. 14

S,21

R-diHDHA is synthesized by conversion of the essential fatty acid docosahexaenoic acid through sequential catalysis involving 12-lipoxygenase and cytochrome P450, including CYP2E1 [

15,

16,

17]. 14

S,21-diHDHA has been shown to accelerate wound closure, re-epithelialization, granulation tissue growth, and blood vessel regeneration in murine excisional wounds and to promote the regenerative functions of mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) in the restoration of wound healing ability [

16] and recovery of renal injury [

19]. It also promotes microvascular endothelial cell angiogenesis, including migration, tubulogenesis, and production of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) [

16,

17], suggesting that this molecule recruits endothelial cells to wounds and stimulates the vascularization necessary for the provision of essential nutrients and O

2 to the newly forming neodermis [

15,

16]. Based on these functions, we have given 14

S,21-diHDHA the name

pro-

regenerative lipid

mediator 1 (PreM1).

MSCs from adipose tissue or bone marrow show substantial regenerative ability when applied to wounds [

1,

2,

5,

42]. Notably, adipose tissue contains

micro

vascular

fragments (MVFs), which are native vascularization units and a rich source of the MSCs, endothelial cells,

perivascular cells, and adipocytes needed to rebuild burn-destroyed skin [

43,

44,

45,

46,

47,

48]. MVFs are easily isolated from fat tissue collected by minimally invasive liposuction [

43], and compared to isolated MSCs, MVFs provide a physiological niche that boosts MSC regenerative power and promotion of vascular differentiation [

43,

44,

45,

46,

47,

48,

49,

50]. Sufficient vascularization is a major requirement for the survival and function of both grafted skin/cells and endogenous cells recruited into implanted constructs and burn wounds, as these cells may not survive solely on the O

2 and nutrients diffusing from nearby tissues [

43]. The grafting of MVFs to wounds or implanted constructs has shown promise in supporting grafted and recruited cells because MVFs reassemble into new blood-perfused microvascular networks and develop interconnections with vessels at the host’s wound margin [

43,

44,

45,

46,

47,

48,

49,

51,

52].

Unfortunately, in severe burn wound cases, patients with large burns are unlikely to have enough fat tissue to serve as an autologous source of fresh MVFs for use in burn treatment. Furthermore, cultivation to expand MVFs takes many days and is thus unlikely to meet an urgent treatment demand. We hypothesize that PreM1 has the potential to activate small numbers of MVFs to restore burn-destroyed blood vessels and heal deep burns. This would circumvent any need for MSC culture and make clinical treatment of large severe burns feasible using autologous uncultured MVFs at the bedside. This idea is supported by the following: PreM1 induces MSCs and Mφs to produce VEGF, IGF1, HGF, and/or PDGF, which are key MSC regenerative factors [

16,

53,

54,

55]. MSCs injured by oxidative stress show recovery when treated with PreM1, maintain cell viability, and show reduced apoptosis via PI3K signaling [

19]. PreM1 treatment of MSCs also markedly promotes the acceleration of blood vessel regrowth and the re-epithelialization of full-thickness excisional wounds [

16].

The ideal niche for MVF regenerative functions should provide PreM1 (due to the mentioned PreM1 bioactions) and a housing for MVFs. The half-life of PreM1 in wounds is 1 to 2 h, which limits its utility as a functionalizer for MVFs. However, the inclusion of PreM1 in hydrogels (gels) could conceivably provide protection from degradation, while also offering sustained PreM1 release to the wound. Hydrogels, which consist largely of biological fluid and structurally resemble the natural extracellular matrix, can provide three-dimensional (3D) networks that can function as 3D scaffolds for MVFs to promote wound healing [

56,

57,

58,

59,

60,

61,

62,

63,

64,

65,

66]. In addition, the gels may provide interim replacement of burn-destroyed dermis and promote neodermis growth, while also covering wounds as a conventional primary dressing for burns. We have developed ACgel1, a biodegradable amino acid–based protein-mimic gel, which is able to scaffold and deliver MSCs to promote accelerated healing of deep burns in mice [

67]. ACgel1 is synthesized from

unsaturated

arginine-based

poly(

ester

amide) (UArg-PEA) and a

chitosan derivative (glycidyl methacrylate [GMA] chitosan). ACgel1 has excellent biodegradability and biocompatibility without toxicity [

68,

69,

70,

71,

72] and is wound compatible [

67]. In this study, we report on further developments of ACgel1 obtained by incorporating PreM1 and fabricating the gel for MVF seeding and delivery to 3

o burn wounds and for wound coverage.

The ACgel1 can sustain PreM1 release because of the binding between the anionic PreM1 [

15,

16] and the cationic Arg and chitosan of ACgel1. The gradual breakdown of this binding together with UArg-PEA biodegradation, is consistent with our previous reports [

73,

74,

75,

76,

77]. Mouse 3

o burn wounds showed marked promotion of healing when treated with PreM1-containing and MVF-seeded ACgel1.

2. Results

2.1. PreM1 Release to 3o Burn Wounds from ACgel1 with and without MVF Seeding

PreM1 was loaded into ACgel1 networks, adsorbed by the ACgel1 matrix due to attraction between anionic PreM1 and cationic ACgel1. When PreM1-containing ACgel1 (PreM1-ACgel1) covered and directly contacted wounds, PreM1 was expected to show gradual release into the wounds due to diffusion and the biodegradation of the ACgel1. PreM1 released from ACgel1 in 3

o burn wounds at 3 and 7 dpb was authenticated because the chromatogram of aqueous reversed-phase chiral liquid chromatography coupled with tandem mass spectrometry (acLC-MS/MS) multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) (

Figure 1A, a typical one) and LC-MS/MS full scan spectrum (

Figure 1B, a typical one) acquired from wound extracts matched those of the molecular standard [

78]. As illustrated in

Figure 1B (insert), the tandem MS/MS spectrum of the chromatographic peak in

Figure 1A consisted of ions at

m/z 359 [M-H]

-, 341 [M-H-H

2O]

-, 323 [M-H-2H

2O]

-, 297 [M-H-CO

2-H

2O]

-, and 279 [M-H-CO

2-2H

2O]

-, demonstrating two hydroxyls and one carboxyl in the deprotonated molecular ion [M-H]

- m/z 359 (

Figure 1B). The 14-hydroxyl was indicated by ions

m/z 205, 234, 189, and 161, the 21-hydroxyl by ions

m/z 315, 271 and 253, which resulted from the breakage of the C20-C21 bond in the deprotonated molecular ion

m/z 359 [M-H]

- and a neutral loss of CH(O)CH

3 (44 au) from the terminal group of carbons at the tail of the molecular ion (

Figure 1B). PreM1 release into 3

o burn wounds from PreM1-ACgel1 or PreM1-MVFs-ACgel1 was sustained up to 7 dpb, whereas PreM1 was undetectable at 3 or 7 dpb in the saline control group based on quantification via LC-MS/MS-MRM (

Figure 1C). PreM1 release was still sustained to bioactive levels in 3

o burn wounds from the PreM1-ACgel1 or PreM1-MVFs-ACgel1 at 7 dpb based on prior studies [

17], although the levels were lower than those at 3 dpb (

Figure 1C). Notably, the PreM1 release to 3

o burn wounds was higher from the PreM1-ACgel1 than from the MVF-seeded PreM1-ACgel1 (PreM1-MVFs-ACgel1), although the differences were not statistically significant (

Figure 1C).

2.2. PreM1-Containing ACgel1 Markedly Enhanced MVF Promotion of Wound Closure and Re-Epithelialization of 3o Burn Wounds

Treatments with PreM1 [

15,

16,

17,

18], ACgel1 [

79], or MVFs [

43,

49,

50] individually are already known to promote wound healing. ACgel1 can sustain PreM1 release to burn wounds and promote the healing capacity of MSCs, a key component of MVFs [

43,

49,

50]. However, the effects of the incorporation of PreM1, MVFs, and ACgel1 on wound closure and re-epithelialization of 3

o burn wounds are unknown. Treatment of excision-debrided 3

o burn wounds with saline control, PreM1 alone, MVFs alone, ACgel1 alone, PreM1-ACgel1, MVF-seeded ACgel1 (MVFs-ACgel1), and PreM1-MVFs-ACgel1 showed that, by 7 days post burn (dpb), the wounds were closed from the initial 6 mm diameter circular full-thickness burns at 0 dpb with closure percentages in the following descending order: MVFs-PreM1-ACgel1, PreM1-ACgel1, MVFs-ACgel1, MVFs, PreM1, saline, and ACgel1 (

Figure 2). The wounds treated with PreM1-MVFs-ACgel1 were closed 65.5% in average, which was significantly faster than any other groups (

p < 0.01) except than PreM1-ACgel1 (

p < 0.05) (

Figure 2B). Wounds showed significantly greater closure following treatment with PreM1-ACgel, MVFs-ACgel, PreM1, or MVFs than with saline alone (

p < 0.01 or 0.05), whereas no significant difference was noted between the ACgel1 and saline treatments (

Figure 2B). Wound closure was greater following treatment with PreM1-ACgel1 than with PreM1 or ACgel1 alone (

p < 0.01). Wound closure was significantly greater following treatment with MVFs-ACgel1 than with MVFs or ACgel1 alone (

p < 0.05 or 0.01).

By 13 dpb, the wounds were closed from the initial burns of 0 dpb, with closure percentages in descending order: PreM1-MVFs-ACgel1, MVFs-ACgel1, PreM1-ACgel1, MVFs, PreM1, ACgel, and saline (

Figure 2). The wound closure following treatment with PreM1-MVFs-ACgel1 was 97% in average, which was significantly greater than in any other group (

p < 0.01) (

Figure 2B). Wound closure was significantly greater following treatment with PreM1-ACgel, MVF-ACgel1, PreM1, MVFs, or ACgel1 than with saline alone (

p < 0.05 or 0.01) (

Figure 2B). Wound closure was significantly greater following treatment with PreM1-ACgel1 than with PreM1 or ACgel1 alone (

p < 0.05). Wound closure was significantly greater following treatment with MVFs-ACgel1 than with MVFs or ACgel1 (

p < 0.05).

Wound re-epithelialization was assessed based on the relative epithelial gap (% of saline control) between neoepithelial edges determined by H&E histochemical analysis of the skin wounds harvested at 13 dpb after euthanasia of the mice (

Figure 3). The relative epithelial gaps of 3

o burn wounds were significantly reduced by each treatment compared to the saline control, including PreM1-MVFs-ACgel1, PreM1-ACgel1, MVFs-ACgel1, PreM1, MVFs, and ACgel1. Thus, each of these treatments is able to promote re-epithelialization of 3

o burn wounds. Moreover, the relative epithelial gap of 3

o burn wounds treated with PreM1-MVFs-ACgel1 was significantly smaller than in any of the other groups (

p < 0.05 or 0.01) (

Figure 3). Therefore, ACgel1 incorporated with both PreM1 and MVFs are more effective in promoting re-epithelialization of 3

o burn wounds than ACgel1 incorporated with just one (either PreM1 or MVFs), and more effective than ACgel, PreM1, or MVFs alone (

Figure 3). The data in Figs. 2 and 3 demonstrated that ACgel1 incorporated with PreM1 enhanced MVF promotion of wound closure and re-epithelialization of 3

o burn wounds.

2.3. PreM1 Enhanced MVFs-ACgel1 Promotion and MVFs Enhanced PreM1-ACgel1 Pro-Motion for Blood Vessel Regeneration in 3o Burn Wounds

To evaluate the treatments on blood vessel regeneration, we determine the CD31+ blood vessels of excision-debrided 3

o burn wounds under each treatment by immuno-fluorescent histology (

Figure 4). The cryosections of 3

o burn wounds possessed signifi-cantly higher mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of CD31+ vascularity (

Figure 4), mostly capillary blood vessels (

Figure 4A), for the treatment with PreM1-MVFs-ACgel1 (g), PreM1-ACgel1 (f), or MVFs-ACgel1 (e), than for saline control (

p < 0.01), indicating sig-nificantly more blood vessel regeneration of 3

o burn wounds under these treatments. Moreover, the wounds had a higher MFI for CD31+ vascularity in the PreM1-ACgel1 group (f) than in the ACgel1 group (b) (

p < 0.05) (

Figure 4B), suggesting that ACgel1 in-teracts with PreM1 to promote blood vessel regeneration in 3

o burn wounds. Addition-ally, the wounds had higher MFI of CD31+ vascularity for MVFs-ACgel1 group (e) than for MVFs group (c), although the significance of difference was marginal (

p < 0.059) (

Figure 4B), which implies that MVFs-ACgel1 could be somewhat more effective than MVFs alone in promoting blood vessel regeneration, and that ACgel1 could interact with MVFs in promoting vascularization in wounds. Furthermore, PreM1-MVFs-ACgel1 (g) was significantly more effective than PreM1-ACgel1 (f) or MVFs-ACgel1 (e) in promoting blood vessel regeneration, as the CD31+ vascularity in wounds was higher for PreM1-MVFs-ACgel1 group (g) than for PreM1-ACgel1 (f) or MVFs-ACgel1 (e) group (

p < 0.01) (

Figure 4). This reflects that PreM1 enhanced MVFs-ACgel1 promotion and MVFs enhanced PreM1-ACgel1 promotion for blood vessel regeneration in 3

o burn wounds.

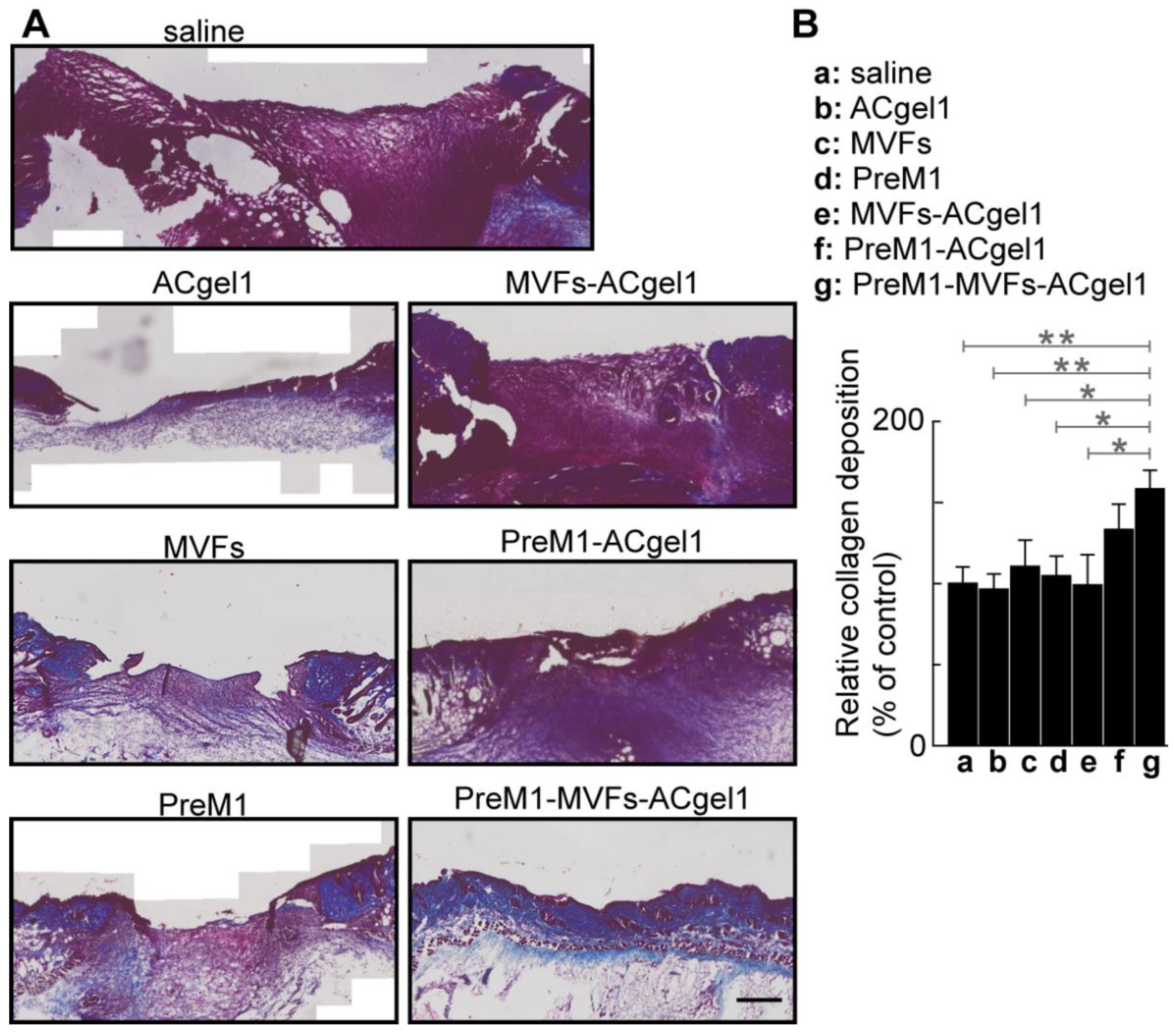

2.4. PreM1-MVFs-ACgel1 Treatment Increased the Collagen Level in 3o Burn Wounds

Collagen plays an important role in wound healing [

80] and skin functions; there-fore, it was evaluated by histochemical analysisin wound sections for each treatment and control. The 3

o burn wounds were filled with more collagen, presented as blue Masson-trichrome stain, in the MVFs-PreM1-ACgel1 (g) group than in saline control (a) and ACgel1 (b) groups (

p < 0.01), in the MVFs (c), PreM1 (d), and ACgel1+MVFs (e) (

p < 0.05) (

Figure 5). Burns treated with PreM1- MVFs-ACgel1 (g) also possessed better organized collagen and extracellular matrix when compared to wounds treated with saline or other treatments (

Figure 5A). The 3

o burn wounds of the saline control (a) exhib-ited poor collagen deposition and an immature extracellular matrix (

Figure 5A). These data indicate that the combined incorporation of PreM1, MVFs, and ACgel1 into a nov-el construct of PreM1-MVFs-ACgel1 can promote collagen formation, which is an im-portant response required for the healing of 3

o burns. Notably, the collagen levels in 3

o burn wounds were higher when treated with PreM1-ACgel1 or MVFs than with the saline control, although the difference was not statistically significant (

Figure 5).

2.5. No Behavior Abnormality Was Observed for Each Treatment Compared to Saline Control

There were no observed differences in mouse behavior, including drinking, for-aging, grooming, or eating from 0 dpb to 13 dpb (when mice were euthanized for wound tissue harvesting), between the saline control group and any of the treatment groups (PreM1-MVFs-ACgel1, PreM1-ACgel1, MVFs-ACgel1, PreM1, MVFs, and AC-gel1). This observation suggest that any of treatments was likely to be nontoxic at least for these behaviors.

3. Discussion

Severe deep burns are life-threatening and profoundly reduce quality of life [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7]. The current clinical treatment for severe deep burns is autologous skin grafts, but these grafts are limited due to donor site unavailability and substantial comorbidities, thereby underscoring the urgent need for more effective therapies [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8]. The present study was prompted by the existing knowledge regarding wound healing: 1) PreM1 is able to promote wound healing and the regenerative functions of MSCs, endothelial cells, and macrophages; 2) The healing of 3

o burns and regenerative functions of MSCs is also enhanced by treatment with ACgel1: our chitosan-coupled amino acid-based polymer hydrogel; and 3) Adipose-tissue derived MVFs, which function as native vascularization units that are enriched with MSCs, endothelial cells, and perivascular cells, and therefore have a high potential to promote the regeneration of deep burn-destroyed skin. Given this background knowledge, we developed an innovative primary hydrogel dressing, PreM1-MVF1-ACgel1, that incorporated PreM1 and MVFs into the ACgel1. In the present study, we tested its utility as a treatment for 3

o-burn wounds in mice.

The optimally designed and fabricated PreM1-ACgel1 and PreM1-MVFs-ACgel1 constructs were able to deliver PreM1 into 3

o burn wounds at approximately 31.5 ng/g of wound tissue up to at least 7 days post-burn when used as a covering that directly contacted the wounds (

Figure 1). This level of PreM1 is a prohealing level, as PreM1 promotes angiogenesis of microvascular endothelial cells at the tested dosage range of 1–1000 nM (equivalent to 0.36 to 360 ng/g of wound tissue) [

17]. The PreM1 delivered by PreM1-ACgel1 and PreM1-MVFs-ACgel1 was sustained at least up to 7 dpb, although the delivery was only 30%-40% of the levels delivered by these two constructs at 3 dpb. Since the half-life of PreM1 in wounds is only a few hours, the PreM1 delivered earlier was likely to be degraded by 7 dpb. MVFs may degrade PreM1 in the PreM1-MVFs-ACgel1 and/or in the 3

o burn wounds, although the amount of degradation is unlikely to be significant, since the reduction associated with MVFs on PreM1 delivery by ACgel1 to the 3

o burn wounds was not significant (

Figure 1C).

Effective wound closure after deep burns is pivotal for both survival and the best long-term functioning and appearance, as it is needed to prevent infection, fluid loss, and hypertrophic scarring [

81] while participating in and supporting other healing processes. Overall, PreM1-MVFs-ACgel1, PreM1-ACgel1, MVFs-ACgel1, PreM1, and MVFs accelerated wound closure at both 7 and 13 dpb, while the degree or quantity of improvement is associated with days post-burn for the observation of wound closure (

Figure 2). ACgel1 promoted wound closure at 13 dpb, but this action was not apparent at 7 dpb. The observation that PreM1-MVFs-ACgel1 was the most effective treatment for accelerating wound closure is reasonable because this construct contained three prohealing components, whereas the other treatment groups had only one or two of these components.

Re-epithelialization is the most crucial response required to rebuild the basic skin barrier in the wound healing process. It is primarily driven by keratinocyte regeneration (migration, proliferation, and differentiation), with participation by epidermal stem cells, fibroblasts, and immune cells [

82,

83]. Spontaneous re-epithelialization of deep burn wounds progresses slowly, with complete resurfacing in humans often requiring weeks [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8]. Re-epithelialization and other healing processes are typically induced in deep burns using treatments involving necrotic skin excision and skin grafting [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

84]. The aim of the present study was to provide an adjuvant or complementary therapeutic candidate that could reduce or surmount the need for skin grafting. Although all the treatments tested here could significantly accelerate re-epithelialization of 3

o burn wounds when compared to the saline control, the PreM1-MVFs-ACgel1 treatment outperformed all the other treatments, likely because it incorporated all three prohealing substances: PreM1, MVFs, and ACgel1. PreM1 delivery to 3

o burn wounds was sustained; the sustained release of PreM1 promoted MVF angiogenic and regenerative functions during the healing process while also directly accelerating the healing of 3

o burn wounds. These findings were reasonable, because PreM1 is able to promote the angiogenic and regenerative functions of mesenchymal stem cells and endothelial cells, which are both components of MVFs [

43,

49,

50].

Blood vessels destroyed by 3

o burning must be regenerated to supply oxygen, nutrients, molecular factors, and cells for efficient wound healing and normal skin function [

4,

5,

8]. Our results showed that treatment with PreM1-MVFs-ACgel1, PreM1-ACgel1, or MVFs-ACgel1 accelerated blood vessel regeneration in 3

o burn wounds (

Figure 4). This finding was consistent with the promotion of wound re-epithelization (

Figure 3) and wound closure (

Figure 2) by these gels, as the restoration of blood vessels should promote wound re-epithelization and subsequent wound closure. Notably, the 3

o burn wounds at 13 dpb appeared to have higher vascularity after treatment with PreM1, MVFs, or ACgel1 compared to the saline control, although the difference was not statistically significant (

Figure 4). These treatments could clearly manifest a significant promotion of blood vessel regrowth earlier in the inflammation or proliferation phase, as wound healing is a dynamic process and PreM1 [

15,

16,

17,

18], ACgel1 [

79], or MVFs [

43,

49,

50] are recognized as prohealing and/or pro-angiogenic factors. This warrants further investigation in the future.

Another feature of wound healing affected by our treatments was collagen production. Collagen serves both as a construction material during wound healing and as a regulatory signal for the healing process [

80]. PreM1-MVFs-ACgel1 treatment increased the collagen levels in the 3

o burn wounds, corresponding to its promotion of wound vessel regeneration, re-epithelization, and wound closure. The enhancement of collagen deposition in the 3

o burn wounds should increase re-epithelization, wound closure, and wound breaking strength. The PreM1-MVFs-ACgel1 integrates prohealing PreM1, MVFs, and ACgel1 factors so that ACgel1 sustains PreM1 release and scaffolds MVFs for their functioning, while the sustained release of PreM1 promotes MVF functions. Therefore, a logical expectation was that PreM1-MVFs-ACgel1 would outperform treatments consisting of only one or two of these factors in promoting collagen levels in 3

o burn wounds. The results confirmed this prediction except that the outperformance by PreM1-MVFs-ACgel1 over PreM1-ACgel1 in promoting collagen levels was not statistically significant. The regenerative or prohealing properties of PreM1, MVFs, and ACgel1 suggest the possibility that PreM1-ACgel1 or other treatments could significantly enhance the collagen levels in 3

o burn wounds at later time points when remodeling is further advanced.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Materials

The major chemicals purchased for use in the preparation of ACgel1 included the following: L-arginine (L-Arg), fumaryl chloride, ethylene glycol, and 1,4-butanediol (Alfa Aesar, Ward Hill, MA, USA); chitosan (75-85% deacetylated; molecular weight [MW] 150 kg mol

-1), and α-isonitrosopropiophenone, 4-(N,N-dimethylamino) pyridine (DMAP, 99%) (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA); glycidyl methacrylate (GMA, 97%) (VWR Scientific, West Chester, PA, USA);

p-toluene sulfonic acid monohydrate and

p-nitrophenol (J.T. Baker, Philipsburg, NJ, USA); triethylamine (Avantor Performance Materials, Center Valley, PA, USA); Irgacure 2959, Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium (DMEM), sterile saline (0.9% NaCl or phosphate-buffered saline [PBS]), cell/tissue strainer (500 µm), and solvents (toluene, isopropyl alcohol, N,N-dimethylacetamide, DMSO; ethyl acetate, and acetone) (Thermo-Scientific. Ward Hill, MA, USA). PreM1 (14

S,21

R-dihydroxy-docosa-4

Z,7

Z,10

Z,12

E,16

Z,19

Z-hexaenoic acid or 14

S,21

R-diHDHA) was prepared through total organic synthesis, and verified and quantified right before its usage for the validation of its structures, purities, and concentrations using our aqueous reversed-phase chiral liquid chromatography coupled with ultra-violet photodiode detector and tandem mass spectrometry (acLC-UV-MS/MS) as described in our previous publications [

15,

16,

19,

78,

85,

86].

4.2. Preparation of the PreM1-Containing ACgel1

Following the procedures described in our previous reports [

67,

72], we prepared ACgel1 from

unsaturated

arginine-based

poly(

ester

amide) (UArg-PEA) and a

chitosan derivative (glycidyl methacrylate [GMA] chitosan). We synthesized UArg-PEA via solution polycondensation of Arg alkylene diester monomer salt (I) and the di-

p-nitrophenyl ester of dicarboxylic acid monomer (II), as we presented in [

72,

87,

88], where the synthesis of I and II followed the procedures described in [

89]. The GMA-chitosan was prepared using our previously described protocol [

67]. The newly fabricated ACgel1 was soaked overnight in and rinsed thoroughly with deionized water to eliminate unreacted reactant residues. The ACgel1 was pre-cut into cylindrical rods (12 × 6 mm, length × diameter) and soaked in 70% ethanol/water in a tissue culture hood for 20 min for sterilization.

The rods were then cut into disks (6 mm diameter × 1.5 mm thickness) for subsequent experiments. The 70% ethanol used to soak the ACgel1 disks was replaced with saline (0.9% NaCl) by repeated soaking and rinsing. A 25 µL volume of the saline was then withdrawn from the ACgel1 using a pipette and replaced with 20 µL PreM1 solution (72 µg PreM1/mL in saline, pH 7.4). The solution was allowed to merge into the ACgel1 pores by capillary force and gravity as well as by gently drawing fluid with a pipette from the back side of the ACgel1. The anionic PreM1 was adsorbed by binding to the cationic Arg and chitosan moieties of the ACgel1.

4.3. Animals: General information

The IACUC committee at the Louisiana State University Health Science Center (LSUHSC) approved all animal procedures, ensuring adherence to the guidelines set by the American Veterinary Medical Association. C57BL/6J mice (Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME, USA) were housed at LSUHSC under controlled and specific patho-gen-free conditions, with a temperature of 25 ± 2°C, humidity levels between 50% and 65%, and a consistent 12:12 h light–dark cycle. The mice were fed a standard diet and tap water; both were sterilized.

4.4. Preparation of adipose tissue–derived microvascular fragments from mouse fat pads

Microvascular fragments (MVFs) were prepared from the epididymal fat pads of 8–15 month old C57/BL6 male mice under aseptic conditions, according to established protocols [

44,

45,

46,

47,

48]. Their body weights were more than 30 g/mouse, which provided sufficient amounts of MVFs for AC gel seeding. The mice were anesthetized to the level of no response to a toe pinch using 5% isoflurane inhalation. Their skin surface was sterilized thoroughly with 70% ethanol, and the animals were placed supinely on a sterile drape on a table and immobilized by taping their paws to the surface. The abdominal skin was separated free of the underlying muscle layer by cutting with scissors. We then performed a midline laparotomy with scissors, laterally unfolded the flaps of the abdominal wall, and collected the epididymal fat pads using small scissors and fine forceps. The fat pads were immediately submerged in DMEM (containing 10% fetal bovine serum [FBS], 100 U/mL penicillin and 0.1 mg/mL streptomycin) at 37°C. An approximate 3 mm margin was maintained between the epididymis and the fat to avoid unwanted epididymal gathering. The mouse, while still under anesthesia, was then euthanized by cervical dislocation.

The fat pads were rapidly processed after harvesting to minimize potential ex vivo tissue damage. The fat pads were washed with PBS, transferred to 15 mL polypropylene (PP) tubes, and minced with small scissors into a homogenous tissue suspension. The minced fat pads were transferred with two volumes of collagenase type 1 (6 mg/mL PBS, sterile), shaken well, and incubated for 8–15 min at 37°C and humidified atmospheric conditions with 5% CO2 for tissue digestion until the digestate mainly contained “free” MVFs next to single cells. The enzyme reaction was then neutralized by adding 2 volumes of 20% FBS/PBS. We pipetted out the remaining fat, which formed an upper layer due to gravity after incubation (37°C, 5 min) of the obtained suspension. We repeated this incubation–removal process three times and then removed the remaining fat clots in the suspension by passage through a 500 µm filter. The MVFs in the filtrate were counted using a microscope [

45], pelleted by centrifugation (120 g, 5 min), and then resuspended in sterile saline (0.9% NaCl) to 500 MVFs/µL saline for MVF seeding. The final suspension also contained ~9,600 single cells/µL saline. The single cells mainly include endothelial cells, α-smooth muscle actin (SMA)-positive perivascular cells, and MSCs based on the studies by other groups [

44,

45,

46,

47,

48].

4.5. MVF Seeding of PreM1-Containing ACgel1

Seeding was performed based on the methods established by others[

44,

45,

46,

47,

48] and on our method for seeding mesenchymal stem cells to ACgel1 [

67]. In brief, 20 µL saline was pipetted out from the PreM1-containing ACgel1 or control ACgel1, followed by the transfer of a 20 µL suspension, containing 500 MVFs/µL saline, to the front side of the gel. The MVFs seeded into the gels during the downward flow of saline carrier due to the capillary force of gel pores, gravity, and negative pressure drawing generated by pipetting at the back side of the gel.

4.6. Mouse Model of 3o Burn Wounds and Treatments

The experimental groups with 3

o burn wounds included a saline control, PreM1 alone, MVFs alone, ACgel1 alone, PreM1-containing ACgel1 (PreM1-ACgel1), MVF-seeded ACgel1 (MVFs-ACgel1), and MVF-seeded PreM1-ACgel1 (PreM1-MVFs-ACgel1). Each treatment group included four female C57BL/6J mice aged between 5 and 10 months (body weight: 22 to 25 g/mouse). The mice were acclimated more than a week before the procedure. We removed the hair from the mouse skin where burning was imposed, and the surrounding area, using a hair clipper (

https://thecutbuddy.com) followed by hair removal cream (VEET Gel Cream Sensitive Formula,

https://www.veet.us). The cream was washed completely from the skin using warm water. We moderately anesthetized the mice to minimize potential distress and mobility with 2% isoflurane inhalation, even though the hair removal procedures are painless. After 6 to 12 h, we anesthetized the mice using 3–5% isoflurane inhalation and administered sustained release buprenorphine (Wedgewood Pharmacy, Swedesboro, NJ, USA) (1 mg/kg, SQ) with analgesic action for up to 3 days.

A mouse model of a third-degree burn of the dorsal skin was employed using the published methodology and device design with modifications [

9,

10,

11,

90,

91]. Briefly, under sterile conditions, paired, circular, uniform 6 mm full-thickness 3

o burn wounds were created symmetrically along the midline of the dorsal skin of each mouse. We generated the two burns by sandwiching the dorsal skin fold of the mouse, at 55 g force perpendicularly to the fold for 40 seconds, with the flat 6 mm diameter ends of two brass cylindrical rods. The surface temperature of each end that contacted the skin was accurately and rapidly controlled to 110

oC for burning using a digital programmable mini-soldering iron (TS100, GtFPV, FL, USA). We obtained the skin fold by gently holding the full-thickness skin along the midline with our fingers (without stretching, as the skin is loose). The skin was unfolded, returned to the original position immediately after the burn, and then wrapped with Tegaderm waterproof film dressings (

www.3m.com, catalog number 16002) for protection and water loss prevention. Each mouse was housed singly in a pathogen-free cage with paper bedding.

At 48 h or 2 days post-burn (dpb), the mice were anesthetized and provided with analgesia again, as above for burning. We debrided the 3

o burns by excising a circle of coagulated or necrotic full-thickness skin 6 mm in diameter from each burned site using a biopsy punch and fine surgery scissors and forceps. This excision resembles the clinical practice of debriding deep burns. We then filled each excision-generated space with a specific 6 mm diameter piece of ACgel1, including ACgel1 alone, PreM1-ACgel1, MVFs-ACgel1, or PreM1-MVFs-ACgel1. For comparison, we injected MVFs (10,000/wound), PreM1 (0.5 nmol/wound/day), or saline vehicle (0.9% NaCl, 20 µl/wound) directly onto the wound margin (5 µL into tissue under the wound bed and 5 µL/site into 3 sites of the dermis along the wound edge). We wrapped the wound areas and the hair-removed skin of the mouse body trunk with Tegaderm films to maintain the position and hydration of the ACgel1 and wounds as well as to minimize wound contraction, as we have done previously [

63,

92]. This could assist wound closure through re-epithelialization, as described in prior studies [

93,

94,

95], thereby better resembling wound healing in humans.

2.7. Postoperative Care, Wound Closure Measurement, and Sampling

Fluid resuscitation was conducted by intraperitoneal injection of 1.7 mL 37

oC sterilized 0.9% NaCl saline within 1 h post-burn and 0.5 mL at 12 h post-burn to a mouse with a body weight ~24 g [

79]. The fluid resuscitation was continued at 1.2 mL/mouse/12 h until the mouse regained normal activity. We checked mouse health and behavior, including drinking, foraging, grooming, and eating, and we inspected all wounds twice per day to maintain the ACgel1 and dressing. We determined wound healing as performed previously [

16,

18,

86,

96,

97,

98]. To clearly observe the wounds, we changed the Tegaderm film at 7 dpb. The wounds were photographed with a ruler in the same focal plane as a reference for size measurement. Their areas were determined using ImageJ software (National Institute of Health, Bethesda, MA, USA). The wound closure was evaluated as the closed wound area (%) relative to the initial burn-wound area. The mice were euthanized at 13 dpb, and full-thickness wounds with 3–5 mm skin margins were excised and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS (pH7.4, 12h, ~4

oC on water ice and in refrigerator).

2.8. Determination of PreM1 Release to 3o Burn Wounds from ACgel1 with and without MVF Seeding

The PreM1-MVFs-ACgel1 treatment described in section 2.6 was also conducted specifically for this study in parallel to those for the histological assessment of wound healing. These mice were euthanized by decapitation with sharp scissors after deep anesthesia via 5% isoflurane inhalation (three mice at 3 dpb and three mice at 7 dpb). A piece of full-thickness skin containing an excision-debrided 3

o burn wound treated with PreM1-MVFs-ACgel1 was harvested using a 12 mm diameter circular biopsy puncture and microsurgery scissors and forceps, weighed, and then submerged in ice-cold 80% acetone containing butylated hydroxytoluene (0.005%) as an antioxidant and deuterium-labeled internal standard prostanglandin-D

2-d

4 (Cayman Chemical, Ann Arbor, MI, USA), and chilled immediately with liquid nitrogen. Each sample was minced with fine scissors to sub-millimeter pieces, homogenized, and sonicated in the harvesting solvent for extraction, as reported previously [

15,

16,

18,

86,

98,

99,

100]. The extracts were purified via C18-solid-phase extraction and then analyzed using aqueous reversed-phase chiral liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry (acLC-MS/MS), as detailed previously [

15,

16]. The acLC-MS/MS (TQ-S tandem mass spectrometer coupled to an Acquity LC [Waters, Milford, MA, USA]) used a chiral column (Chiralpak-IA, 150 mm × 2.1 mm × 5 μm; Chiral Technologies, West Chester, PA, USA). The mobile phase was pumped at 0.2 mL/min using the following gradient: 73% A (water:acetic acid = 99.99:0.01) + 27% B (methanol:acetic acid = 99.99:0.01) (0–1 min); ramped to 70.8% A + 29.2% B (1–5 min), to 14.6% A + 85.4% B (5–50 min), and then to 100% B (50–51 min); continued as 100% B (51–56 min); and a final return to 73% A + 27% B. The MeOH solutions from wound extracts were injected into the acLC-UV-MS/MS. The effluent of the chiral LC was atomized by electrospray, and the negatively ionized PreM1 from wound extracts was identified and quantified for comparison with a PreM1 standard using the LC-MS/MS system [

15,

16,

18,

86].

2.9. Histochemical and Immunohistological Studies of 3o Burn Wounds under Different Treatments

The fixed tissue samples were cryoprotected in PBS sucrose gradients (15 and 30%) at 4°C until the tissue settled at the bottom (usually overnight for each gradient), then embedded into OCT (optimum cutting temperature matrix, Tissue-Tec, Torrance, CA, USA) with their anatomic orientations annotated on the silicone molds, and then stored at -80°C for histological analysis, as previously [

15,

17]. Serial cryosections (10 µm thickness/section) of OCT-embedded wounds were made using a cryostat microtome (RWD Life Science Co., San Diego, CA, USA) and transferred to Superfrost slides. The sections were stained with a hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) kit to determine wound re-epithelization/epithelial gap, with a Masson’s trichrome stain kit (Tyr Scientific LLC, Austin, TX, USA) to assess the wound collagen deposition (where collagen was stained blue) and re-modeling, and with CD31 primary-antibody (host: rat, Thermo-Fisher), secondary antibody (host: goat, anti-rat Alexa Fluro 594 [red], Thermo-Fisher), and Hoechst-33342 (staining cell nuclei blue, Thermo-Fisher) to evaluate wound blood vessel regeneration, as described previously [

15,

17,

98,

101,

102]. The H&E stained sections were visualized using an OLYMPUS scanning microscope. The epithelial gap (i.e., the distance between the neoepithelium emerging from the wound edge) was determined using OLYMPUS OlyVIA software, as described previously [

16,

17,

67]. The capillary vascular density in the wound bed was determined using ImageJ as the mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of CD31

+ tissue (showing red fluorescence) in the microscope field of the wound bed in the wound cryosections.

2.10. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was conducted using t-tests or ANOVA followed by Turkey test via GraphPad Prism 9.0 software, and p < 0.05 was considered statistically signifi-cant. Data are presented as mean ± standard error of mean (SEM).

5. Conclusions and Ongoing and Future Studies

This study achieved a novel primary hydrogel-based dressing, PreM1-MVFs-ACgel1, that can effectively promote the healing of 3o burn wounds in mice. PreM1-MVFs-ACgel1 incorporates pro-regenerative lipid mediator 1 and microvascular fragments into an ACgel1 fabricated by covalent condensation coupling of arginine-based poly(ester amide) and a chitosan derivative. Both PreM1-MVFs-ACgel1 and PreM1-ACgel1 can provide sustained release of PreM1 to 3o burn wounds. PreM1-MVFs-ACgel1 accelerated wound closure, re-epithelialization, blood vessel regeneration, and collagen formation in 3o burn wounds. We are currently endeavoring to produce an even more effective modality to heal severe deep burn wounds by the development of other primary hydrogel-based dressings that incorporate different PreM molecules and by assessing PreM1-MVFs-ACgel1 and other gels fabricated using different PreM doses, different MVF doses, and/or different amino acid-based hydrogels. These studies include electron microscopy and mechanical characterizations of these constructs before and after application to wounds at different time points during the healing process, evaluations of the transmigration, proliferation, and expression of key healing-associate factors at protein/peptide and mRNA levels, exploration of the vascularization by MVFs that move from gels to wounds, verification of results using human MVFs in vitro, polarization of macrophages to a reparative phenotype, and resolution of excessive oxidative stress and chronic inflammation in 3o burn wounds. The major benefit of this new modality is the reduction or elimination of reliance on graft-donor requirements, meaning that these gels could be promising adjuvant therapies that can overcome the drawbacks of the grafting methods or skin substitutes currently used to treat severe deep burns.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.H., C.-C.C., Y.L.; Methodology, Y.L., S.S., C.-C.C., Y.K., A.-R.M., H.P., N.L., C.V., R.T., M.H., S.H.; Validation, Y.L., S.S., C.-C.C., Y.K., A.-R.M., H.P., N.L., C.V., R.T., M.H., S.H.; Formal analysis, Y.L., S.S., C.-C.C., A.-R.M., H.P., S.H.; Investigation, Y.L., S.S., C.-C.C., Y.K., A.-R.M., H.P., N.L., C.V., R.T., M.H., S.H.; Resources, S.H., C.-C.C.; Y.K.; Data curation, Y.L., S.S., A.-R.M., S.H.; Writing—original draft preparation, Y.L., C.-C.C., S.H.; Writing—review & editing, Y.L., S.S., C.-C.C., S.H.; Supervision, S.H., C.-C.C.; Project administration, S.H.; Funding acquisition, S.H., C.-C.C.. All authors have read and agreed to the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by LSU Health-New Orleans research enhancement fund (to S.H.) and USA National Institute of Health grant 1R01GM136874 (to S.H. and C.-C.C.), 1R21AG066119 (to S.H. and C.-C.C.), and by the Becky Q. Morgan Foundation for the research funds to C.-C.C..

Institutional Review Board Statement

The animal use protocol was authorized and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Louisiana State University (LSU), Health, New Orleans, USA (protocol code 4339, approved since July 07, 2022).

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Acknowledgments

We are very grateful to Nicholas G. Bazan, the director of Neuroscience Center of LSU Health and School of Medicine, LSU Health-New Orleans, USA for the strong support to make this research possible.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Viswanathan, S.; Keating, A.; Deans, R.; Hematti, P.; Prockop, D.; Stroncek, D.F.; Stacey, G.; Weiss, D.J.; Mason, C.; Rao, M.S. Soliciting strategies for developing cell-based reference materials to advance mesenchymal stromal cell research and clinical translation. Stem Cells Dev 2014, 23, 1157–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Veriter, S.; Andre, W.; Aouassar, N.; Poirel, H.A.; Lafosse, A.; Docquier, P.L.; Dufrane, D. Human Adipose-Derived Mesenchymal Stem Cells in Cell Therapy: Safety and Feasibility in Different "Hospital Exemption" Clinical Applications. PLoS One 2015, 10, e0139566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ibrahim, M.M.; Bond, J.; Bergeron, A.; Miller, K.J.; Ehanire, T.; Quiles, C.; Lorden, E.R.; Medina, M.A.; Fisher, M.; Klitzman, B.; et al. A novel immune competent murine hypertrophic scar contracture model: a tool to elucidate disease mechanism and develop new therapies. Wound repair and regeneration : official publication of the Wound Healing Society [and] the European Tissue Repair Society 2014, 22, 755–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Wei, X.; Liu, L.; Marti, G.P.; Ghanamah, M.S.; Arshad, M.J.; Strom, L.; Spence, R.; Jeng, J.; Milner, S.; et al. Association of increasing burn severity in mice with delayed mobilization of circulating angiogenic cells. Arch Surg 2010, 145, 259–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, C.J. Stem cell application in acute burn care and reconstruction. J Wound Care 2013, 22, 7-8, 10, 12-16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, R.K.; Zamora, D.O.; Wrice, N.L.; Baer, D.G.; Renz, E.M.; Christy, R.J.; Natesan, S. Development of a Vascularized Skin Construct Using Adipose-Derived Stem Cells from Debrided Burned Skin. Stem Cells Int 2012, 2012, 841203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Burn Repository Report of Data 2006–2015; Version 12. 0; American Burn Association: Chicago, IL, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Rogers, A.D.; Jeschke, M.G. Managing severe burn injuries: challenges and solutions in complex and chronic wound care. Chrnonic Wound Care Management and Research 2016, 3, 59–71. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, A.; Cheong, J.Z.A.; Hassan, S.; Wielgat, M.B.; Meudt, J.J.; Townsend, E.C.; Shanmuganayagam, D.; Kalan, L.R.; Gibson, A. The effect of anatomic location on porcine models of burn injury and wound healing. Wound repair and regeneration : official publication of the Wound Healing Society [and] the European Tissue Repair Society 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karim, A.S.; Yan, A.; Ocotl, E.; Bennett, D.D.; Wang, Z.; Kendziorski, C.; Gibson, A.L.F. Discordance between histologic and visual assessment of tissue viability in excised burn wound tissue. Wound repair and regeneration : official publication of the Wound Healing Society [and] the European Tissue Repair Society 2019, 27, 150–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, A.L.F.; Shatadal, S. A simple and improved method to determine cell viability in burn-injured tissue. The Journal of surgical research 2017, 215, 83–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, A.L.F.; Carney, B.C.; Cuttle, L.; Andrews, C.J.; Kowalczewski, C.J.; Liu, A.; Powell, H.M.; Stone, R.; Supp, D.M.; Singer, A.J.; et al. Coming to Consensus: What Defines Deep Partial Thickness Burn Injuries in Porcine Models? Journal of burn care & research : official publication of the American Burn Association 2021, 42, 98–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.Y.; Willard, J.J.; Supp, D.M.; Roy, S.; Gordillo, G.M.; Sen, C.K.; Powell, H.M. Burn Scar Biomechanics after Pressure Garment Therapy. Plast Reconstr Surg 2015, 136, 572–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone Ii, R.; Natesan, S.; Kowalczewski, C.J.; Mangum, L.H.; Clay, N.E.; Clohessy, R.M.; Carlsson, A.H.; Tassin, D.H.; Chan, R.K.; Rizzo, J.A.; et al. Advancements in Regenerative Strategies Through the Continuum of Burn Care. Front Pharmacol 2018, 9, 672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Tian, H.; Hong, S. Novel 14,21-dihydroxy-docosahexaenoic acids: structures, formation pathways, and enhancement of wound healing. Journal of lipid research 2010, 51, 923–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, H.; Lu, Y.; Shah, S.P.; Hong, S. 14S,21R-Dihydroxydocosahexaenoic Acid Remedies Impaired Healing and Mesenchymal Stem Cell Functions in Diabetic Wounds. J Biol Chem 2011, 286, 4443–4453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, H.; Lu, Y.; Shah, S.P.; Hong, S. Novel 14S,21-dihydroxy-docosahexaenoic acid rescues wound healing and associated angiogenesis impaired by acute ethanol intoxication/exposure. J Cell Biochem 2010, 111, 266–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, H.; Lu, Y.; Shah, S.P.; Hong, S. Autacoid 14S,21R-dihydroxy-docosahexaenoic acid counteracts diabetic impairment of macrophage prohealing functions. Am J Pathol 2011, 179, 1780–1791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, H.; Lu, Y.; Shah, S.P.; Wang, Q.; Hong, S. 14S,21R-dihydroxy-docosahexaenoic acid treatment enhances mesenchymal stem cell amelioration of renal ischemia/reperfusion injury. Stem Cells Dev 2012, 21, 1187–1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serhan, C.N.; Chiang, N.; Dalli, J. The resolution code of acute inflammation: Novel pro-resolving lipid mediators in resolution. Seminars in immunology 2015, 27, 200–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcheselli, V.L.; Hong, S.; Lukiw, W.J.; Tian, X.H.; Gronert, K.; Musto, A.; Hardy, M.; Gimenez, J.M.; Chiang, N.; Serhan, C.N.; et al. Novel docosanoids inhibit brain ischemia-reperfusion-mediated leukocyte infiltration and pro-inflammatory gene expression. J Biol Chem 2003, 278, 43807–43817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalli, J.; Vlasakov, I.; Riley, I.R.; Rodriguez, A.R.; Spur, B.W.; Petasis, N.A.; Chiang, N.; Serhan, C.N. Maresin conjugates in tissue regeneration biosynthesis enzymes in human macrophages. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 2016, 113, 12232–12237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calandria, J.M.; Bhattacharjee, S.; Kala-Bhattacharjee, S.; Mukherjee, P.K.; Feng, Y.; Vowinckel, J.; Treiber, T.; Bazan, N.G. Elovanoid-N34 modulates TXNRD1 key in protection against oxidative stress-related diseases. Cell death & disease 2023, 14, 819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, T.L.; Kakazu, A.H.; He, J.; Jun, B.; Bazan, N.G.; Bazan, H.E.P. Novel RvD6 stereoisomer induces corneal nerve regeneration and wound healing post-injury by modulating trigeminal transcriptomic signature. Scientific reports 2020, 10, 4582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazan, N.G.; Musto, A.E.; Knott, E.J. Endogenous signaling by omega-3 docosahexaenoic acid-derived mediators sustains homeostatic synaptic and circuitry integrity. Mol Neurobiol 2011, 44, 216–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, T.L.; He, J.; Kakazu, A.H.; Calandria, J.; Do, K.V.; Nshimiyimana, R.; Lam, T.F.; Petasis, N.A.; Bazan, H.E.P.; Bazan, N.G. ELV-N32 and RvD6 isomer decrease pro-inflammatory cytokines, senescence programming, ACE2 and SARS-CoV-2-spike protein RBD binding in injured cornea. Scientific reports 2021, 11, 12787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazan, N.G.; Calandria, J.M.; Serhan, C.N. Rescue and repair during photoreceptor cell renewal mediated by docosahexaenoic acid-derived neuroprotectin D1. Journal of lipid research 2010, 51, 2018–2031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Norling, L.V.; Spite, M.; Yang, R.; Flower, R.J.; Perretti, M.; Serhan, C.N. Cutting edge: Humanized nano-proresolving medicines mimic inflammation-resolution and enhance wound healing. Journal of immunology 2011, 186, 5543–5547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hellmann, J.; Tang, Y.; Spite, M. Proresolving lipid mediators and diabetic wound healing. Current opinion in endocrinology, diabetes, and obesity 2012, 19, 104–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panigrahy, D.; Kalish, B.T.; Huang, S.; Bielenberg, D.R.; Le, H.D.; Yang, J.; Edin, M.L.; Lee, C.R.; Benny, O.; Mudge, D.K.; et al. Epoxyeicosanoids promote organ and tissue regeneration. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 2013, 110, 13528–13533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, A.G.; Panigrahy, D. Targeting Angiogenesis via Resolution of Inflammation. Cold Spring Harbor perspectives in medicine 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, S.; Gronert, K.; Devchand, P.R.; Moussignac, R.L.; Serhan, C.N. Novel docosatrienes and 17S-resolvins generated from docosahexaenoic acid in murine brain, human blood, and glial cells. Autacoids in anti-inflammation. J Biol Chem 2003, 278, 14677–14687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serhan, C.N.; Hong, S.; Gronert, K.; Colgan, S.P.; Devchand, P.R.; Mirick, G.; Moussignac, R.L. Resolvins: a family of bioactive products of omega-3 fatty acid transformation circuits initiated by aspirin treatment that counter proinflammation signals. J Exp Med 2002, 196, 1025–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duffield, J.S.; Hong, S.; Vaidya, V.S.; Lu, Y.; Fredman, G.; Serhan, C.N.; Bonventre, J.V. Resolvin D series and protectin D1 mitigate acute kidney injury. Journal of immunology 2006, 177, 5902–5911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, S.; Porter, T.F.; Lu, Y.; Oh, S.F.; Pillai, P.S.; Serhan, C.N. Resolvin E1 metabolome in local inactivation during inflammation-resolution. Journal of immunology 2008, 180, 3512–3519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, H.; Lu, Y.; Sherwood, A.M.; Hongqian, D.; Hong, S. Resolvins E1 and D1 in choroid-retinal endothelial cells and leukocytes: biosynthesis and mechanisms of anti-inflammatory actions. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2009, 50, 3613–3620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurihara, T.; Jones, C.N.; Yu, Y.M.; Fischman, A.J.; Watada, S.; Tompkins, R.G.; Fagan, S.P.; Irimia, D. Resolvin D2 restores neutrophil directionality and improves survival after burns. Faseb J 2013, 27, 2270–2281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustafa, M.; Zarrough, A.; Bolstad, A.I.; Lygre, H.; Mustafa, K.; Hasturk, H.; Serhan, C.; Kantarci, A.; Van Dyke, T.E. Resolvin D1 protects periodontal ligament. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 2013, 305, C673–C679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohr, S.; Patel, S.J.; Sarin, D.; Irimia, D.; Yarmush, M.L.; Berthiaume, F. Resolvin D2 prevents secondary thrombosis and necrosis in a mouse burn wound model. Wound repair and regeneration : official publication of the Wound Healing Society [and] the European Tissue Repair Society 2013, 21, 35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Yang, H.; Pan, Z.; Wang, Z.; Wolosin, J.M.; Gjorstrup, P.; Reinach, P.S. Dependence of resolvin-induced increases in corneal epithelial cell migration on EGF receptor transactivation. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2010, 51, 5601–5609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckley, C.D.; Gilroy, D.W.; Serhan, C.N. Proresolving lipid mediators and mechanisms in the resolution of acute inflammation. Immunity 2014, 40, 315–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Burd, A. An update review of stem cell applications in burns and wound care. Indian J Plast Surg 2012, 45, 229–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laschke, M.W.; Menger, M.D. Adipose tissue-derived microvascular fragments: natural vascularization units for regenerative medicine. Trends Biotechnol 2015, 33, 442–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Acosta, F.M.; Gonzalez Porras, M.A.; Stojkova, K.; Pacelli, S.; Rathbone, C.R.; Brey, E.M. Three-Dimensional Culture of Vascularized Thermogenic Adipose Tissue from Microvascular Fragments. Journal of visualized experiments : JoVE 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frueh, F.S.; Spater, T.; Scheuer, C.; Menger, M.D.; Laschke, M.W. Isolation of Murine Adipose Tissue-derived Microvascular Fragments as Vascularization Units for Tissue Engineering. Journal of visualized experiments : JoVE 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acosta, F.M.; Stojkova, K.; Zhang, J.; Garcia Huitron, E.I.; Jiang, J.X.; Rathbone, C.R.; Brey, E.M. Engineering Functional Vascularized Beige Adipose Tissue from Microvascular Fragments of Models of Healthy and Type II Diabetes Conditions. Journal of tissue engineering 2022, 13, 20417314221109337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Acosta, F.M.; Stojkova, K.; Brey, E.M.; Rathbone, C.R. A Straightforward Approach to Engineer Vascularized Adipose Tissue Using Microvascular Fragments. Tissue engineering. Part A 2020, 26, 905–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shepherd, B.R.; Chen, H.Y.; Smith, C.M.; Gruionu, G.; Williams, S.K.; Hoying, J.B. Rapid perfusion and network remodeling in a microvascular construct after implantation. Arteriosclerosis, thrombosis, and vascular biology 2004, 24, 898–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDaniel, J.S.; Pilia, M.; Ward, C.L.; Pollot, B.E.; Rathbone, C.R. Characterization and multilineage potential of cells derived from isolated microvascular fragments. The Journal of surgical research 2014, 192, 214–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frueh, F.S.; Spater, T.; Lindenblatt, N.; Calcagni, M.; Giovanoli, P.; Scheuer, C.; Menger, M.D.; Laschke, M.W. Adipose Tissue-Derived Microvascular Fragments Improve Vascularization, Lymphangiogenesis, and Integration of Dermal Skin Substitutes. J Invest Dermatol 2017, 137, 217–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spater, T.; Frueh, F.S.; Menger, M.D.; Laschke, M.W. Potentials and limitations of Integra(R) flowable wound matrix seeded with adipose tissue-derived microvascular fragments. European cells & materials 2017, 33, 268–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinzierl, A.; Harder, Y.; Schmauss, D.; Menger, M.D.; Laschke, M.W. Microvascular Fragments Protect Ischemic Musculocutaneous Flap Tissue from Necrosis by Improving Nutritive Tissue Perfusion and Suppressing Apoptosis. Biomedicines 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, M.; Akhtar, S.; Mohsin, S.; N. Khan, S.; Riazuddin, S. Growth factor preconditioning increases the function of diabetes-impaired mesenchymal stem cells. Stem Cells Dev 2011, 20, 67–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, P.; Zhang, X.; Wu, Y.; Li, L.; Yin, Q.; Zheng, L.; Zhang, H.; Sun, C. Streptozotocin-induced diabetic rat-derived bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells have impaired abilities in proliferation, paracrine, antiapoptosis, and myogenic differentiation. Transplant Proc 2010, 42, 2745–2752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haider, H.; Ashraf, M. Strategies to promote donor cell survival: combining preconditioning approach with stem cell transplantation. J Mol Cell Cardiol 2008, 45, 554–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirker, K.R.; Luo, Y.; Nielson, J.H.; Shelby, J.; Prestwich, G.D. Glycosaminoglycan hydrogel films as bio-interactive dressings for wound healing. Biomaterials 2002, 23, 3661–3671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boucard, N.; Viton, C.; Agay, D.; Mari, E.; Roger, T.; Chancerelle, Y.; Domard, A. The use of physical hydrogels of chitosan for skin regeneration following third-degree burns. Biomaterials 2007, 28, 3478–3488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiyozumi, T.; Kanatani, Y.; Ishihara, M.; Saitoh, D.; Shimizu, J.; Yura, H.; Suzuki, S.; Okada, Y.; Kikuchi, M. The effect of chitosan hydrogel containing DMEM/F12 medium on full-thickness skin defects after deep dermal burn. Burns : journal of the International Society for Burn Injuries 2007, 33, 642–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, K.L.; Han, D.K.; Park, K.; Song, S.H.; Kim, J.Y.; Kim, J.M.; Ki, H.Y.; Yie, S.W.; Roh, C.R.; Jeon, E.S.; et al. Enhanced dermal wound neovascularization by targeted delivery of endothelial progenitor cells using an RGD-g-PLLA scaffold. Biomaterials 2009, 30, 3742–3748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madsen, J.; Armes, S.P.; Bertal, K.; Lomas, H.; Macneil, S.; Lewis, A.L. Biocompatible wound dressings based on chemically degradable triblock copolymer hydrogels. Biomacromolecules 2008, 9, 2265–2275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shepherd, J.; Sarker, P.; Rimmer, S.; Swanson, L.; MacNeil, S.; Douglas, I. Hyperbranched poly(NIPAM) polymers modified with antibiotics for the reduction of bacterial burden in infected human tissue engineered skin. Biomaterials 2011, 32, 258–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balakrishnan, B.; Mohanty, M.; Umashankar, P.R.; Jayakrishnan, A. Evaluation of an in situ forming hydrogel wound dressing based on oxidized alginate and gelatin. Biomaterials 2005, 26, 6335–6342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baravkar, S.B.; Lu, Y.; Masoud, A.R.; Zhao, Q.; He, J.; Hong, S. Development of a Novel Covalently Bonded Conjugate of Caprylic Acid Tripeptide (Isoleucine-Leucine-Aspartic Acid) for Wound-Compatible and Injectable Hydrogel to Accelerate Healing. Biomolecules 2024, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rustad, K.C.; Wong, V.W.; Sorkin, M.; Glotzbach, J.P.; Major, M.R.; Rajadas, J.; Longaker, M.T.; Gurtner, G.C. Enhancement of mesenchymal stem cell angiogenic capacity and stemness by a biomimetic hydrogel scaffold. Biomaterials 2012, 33, 80–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, X.; Lang, Q.; Yildirimer, L.; Lin, Z.Y.; Cui, W.; Annabi, N.; Ng, K.W.; Dokmeci, M.R.; Ghaemmaghami, A.M.; Khademhosseini, A. Photocrosslinkable Gelatin Hydrogel for Epidermal Tissue Engineering. Adv Healthc Mater 2016, 5, 108–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobolak, J.; Dinnyes, A.; Memic, A.; Khademhosseini, A.; Mobasheri, A. Mesenchymal stem cells: identification, phenotypic characterization, biological properties and potential for regenerative medicine through biomaterial micro engineering of their niche. Methods 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alapure, B.V.; Lu, Y.; He, M.; Chu, C.C.; Peng, H.; Muhale, F.; Brewerton, Y.L.; Bunnell, B.; Hong, S. Accelerate Healing of Severe Burn Wounds by Mouse Bone Marrow Mesenchymal Stem Cell-Seeded Biodegradable Hydrogel Scaffold Synthesized from Arginine-Based Poly(ester amide) and Chitosan. Stem Cells Dev 2018, 27, 1605–1620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Mutschler, M.A.; Chu, C.C. Synthesis and characterization of ionic charged water soluble arginine-based poly(ester amide). J Mater Sci Mater Med 2011, 22, 469–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, J.; Wu, D.; Mutschler, M.A.; Chu, C.C. Cationic Hybrid Hydrogels from Amino-Acid-Based Poly(ester amide): Fabrication, Characterization, and Biological Properties. Advanced Functional Materials 2012, 22, 3815–3823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, K.; Chu, C.C. Biodegradation of unsaturated poly(ester-amide)s and their hydrogels. Biomaterials 2007, 28, 3284–3294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, X.; Wu, J.; Deng, M.X.; Chu, C.C.; Chen, X. Synthesis and Characterization of Novel Cationic Hybrid Hydrogels from Pendant Functional Amino Acid-based Poly(ester amide)s. Acta Biomaterials 2014, 10, 3098–3107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, M.; Potuck, A.; Zhang, Y.; Chu, C.C. Arginine-based polyester amide/polysaccharide hydrogels and their biological response. Acta Biomater 2014, 10, 2482–2494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, K.; Chu, C.C. Biodegradable and injectable paclitaxel-loaded poly(ester amide)s microspheres: fabrication and characterization. J Biomed Mater Res B Appl Biomater 2009, 89, 491–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, M.; Wu, J.; Reinhart-King, C.A.; Chu, C.C. Biodegradable functional poly(ester amide)s with pendant hydroxyl functional groups: synthesis, characterization, fabrication and in vitro cellular response. Acta Biomater 2011, 7, 1504–1515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chu, C.C. Novel Biodegradable Functional Amino Acid-based Poly(ester amide) Biomaterials: Design, Synthesis, Property and Biomedical Applications. Journal of Fiber Bioengineering & Informatics 2012, 5, 1–31. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, J.; Chu, C.C. Water insoluble cationic poly(ester amide)s: synthesis, characterization and applications. Journal of Materials Chemistry B 2013, 1, 353–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Zhao, X.; Wu, D.; Chu, C.C. Development of a biocompatible and biodegradable hybrid hydrogel platform for sustained release of ionic drugs. Journal of Materials Chemistry B 2014, 2, 6660–6668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishimura, K.; Sakaguchi, T.; Nanba, Y.; Suganuma, Y.; Morita, M.; Hong, S.; Lu, Y.; Jun, B.; Bazan, N.G.; Arita, M.; et al. Stereoselective Total Synthesis of Macrophage-Produced Prohealing 14,21-Dihydroxy Docosahexaenoic Acids. J Org Chem 2018, 83, 154–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alapure, B.V.; Lu, Y.; Peng, H.; Hong, S. Surgical Denervation of Specific Cutaneous Nerves Impedes Excisional Wound Healing of Small Animal Ear Pinnae. Mol Neurobiol 2018, 55, 1236–1243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathew-Steiner, S.S.; Roy, S.; Sen, C.K. Collagen in Wound Healing. Bioengineering 2021, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singer, A.J.; Boyce, S.T. Burn Wound Healing and Tissue Engineering. Journal of burn care & research : official publication of the American Burn Association 2017, 38, e605–e613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pastar, I.; Stojadinovic, O.; Yin, N.C.; Ramirez, H.; Nusbaum, A.G.; Sawaya, A.; Patel, S.B.; Khalid, L.; Isseroff, R.R.; Tomic-Canic, M. Epithelialization in Wound Healing: A Comprehensive Review. Advances in wound care 2014, 3, 445–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, T.; Yan, Z.; Xiao, S.; Xia, Y. Proinflammatory cytokines regulate epidermal stem cells in wound epithelialization. Stem cell research & therapy 2020, 11, 232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tredget, E.E. The basis of fibrosis and wound healing disorders following thermal injury. J Trauma 2007, 62, S69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, S.; Lu, Y.; Morita, M.; Saito, S.; Kobayashi, Y.; Jun, B.; Bazan, N.G.; Xu, X.; Wang, Y. Stereoselective Synthesis of Maresin-like Lipid Mediators. Synlett 2019, 30, 343–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, S.; Lu, Y.; Tian, H.; Alapure, B.V.; Wang, Q.; Bunnell, B.A.; Laborde, J.M. Maresin-like lipid mediators are produced by leukocytes and platelets and rescue reparative function of diabetes-impaired macrophages. Chem Biol 2014, 21, 1318–1329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, J.; Chu, C.C. Block copolymer of poly(ester amide) and polyesters: synthesis, characterization, and in vitro cellular response. Acta Biomater 2012, 8, 4314–4323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Wu, D.Q.; Mutschler, M.A.; Chu, C.C. Cationic Hybrid Hydrogels from Amino-Acid-Based Poly(ester amide): Fabrication, Characterization, and Biological Properties. Advanced Functional Materials 2012, 22, 3815–3823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, S.; Chu, C.C. Synthesis and characterization of a new family of cationic amino acid-based poly(ester amide)s and their biological properties. Journal of Applied Polymer Science 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, A.; Ocotl, E.; Karim, A.; Wolf, J.J.; Cox, B.L.; Eliceiri, K.W.; Gibson, A.L.F. Modeling early thermal injury using an ex vivo human skin model of contact burns. Burns journal of the International Society for Burn Injuries 2021, 47, 611–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, J.; Cox, B.; Karim, A.; Liu, A.; Gibson, A.L.F.; Eliceiri, K. Burn Device for Reproducible Wound Generation on Ex-vivo Human Skin models. Morgridge Institute for Research. https://morgridge.org/research/labs/fablab/designs/burn-device-for-reproducible-wound-generation/.

- Hong, S.; Baravkar, S.B.; Lu, Y. Amphiphilic Conjugates of Fatty Acids or their Derivatives. US Provisional Patent No: 63617303 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Chung, T.Y.; Peplow, P.V.; Baxter, G.D. Laser photobiomodulation of wound healing in diabetic and non-diabetic mice: effects in splinted and unsplinted wounds. Photomed Laser Surg 2010, 28, 251–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, S.H.; Bae, Y.C.; Nam, S.B.; Choi, S.J. A skin fixation method for decreasing the influence of wound contraction on wound healing in a rat model. Arch Plast Surg 2012, 39, 457–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, Z.; Huang, Y.; Luo, G.; Wu, J.; He, W. A biological membrane-based novel excisional wound-splinting model in mice (With video). Burns Trauma 2014, 2, 196–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, S.; Alapure, B.V.; Lu, Y.; Tian, H.; Wang, Q. 12/15-Lipoxygenase deficiency reduces densities of mesenchymal stem cells in the dermis of wounded and unwounded skin. Br J Dermatol 2014, 171, 30–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, S.; Alapure, B.V.; Lu, Y.; Tian, H.; Wang, Q. Immunohistological localization of endogenous unlabeled stem cells in wounded skin. J Histochem Cytochem 2014, 62, 276–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, S.; Tian, H.; Lu, Y.; Laborde, J.M.; Muhale, F.A.; Wang, Q.; Alapure, B.V.; Serhan, C.N.; Bazan, N.G. Neuroprotectin/protectin D1: endogenous biosynthesis and actions on diabetic macrophages in promoting wound healing and innervation impaired by diabetes. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 2014, 307, C1058–C1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazan, H.A.; Lu, Y.; Thoppil, D.; Fitzgerald, T.N.; Hong, S.; Dardik, A. Diminished omega-3 fatty acids are associated with carotid plaques from neurologically symptomatic patients: Implications for carotid interventions. Vascul Pharmacol 2009, 51, 331–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Han, R.H.; Han, X. Fatty acidomics: global analysis of lipid species containing a carboxyl group with a charge-remote fragmentation-assisted approach. Anal Chem 2013, 85, 9312–9320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Chen, L.; Scott, P.G.; Tredget, E.E. Mesenchymal stem cells enhance wound healing through differentiation and angiogenesis. Stem Cells 2007, 25, 2648–2659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galiano, R.D.; Tepper, O.M.; Pelo, C.R.; Bhatt, K.A.; Callaghan, M.; Bastidas, N.; Bunting, S.; Steinmetz, H.G.; Gurtner, G.C. Topical vascular endothelial growth factor accelerates diabetic wound healing through increased angiogenesis and by mobilizing and recruiting bone marrow-derived cells. Am J Pathol 2004, 164, 1935–1947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).