Submitted:

14 September 2024

Posted:

17 September 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

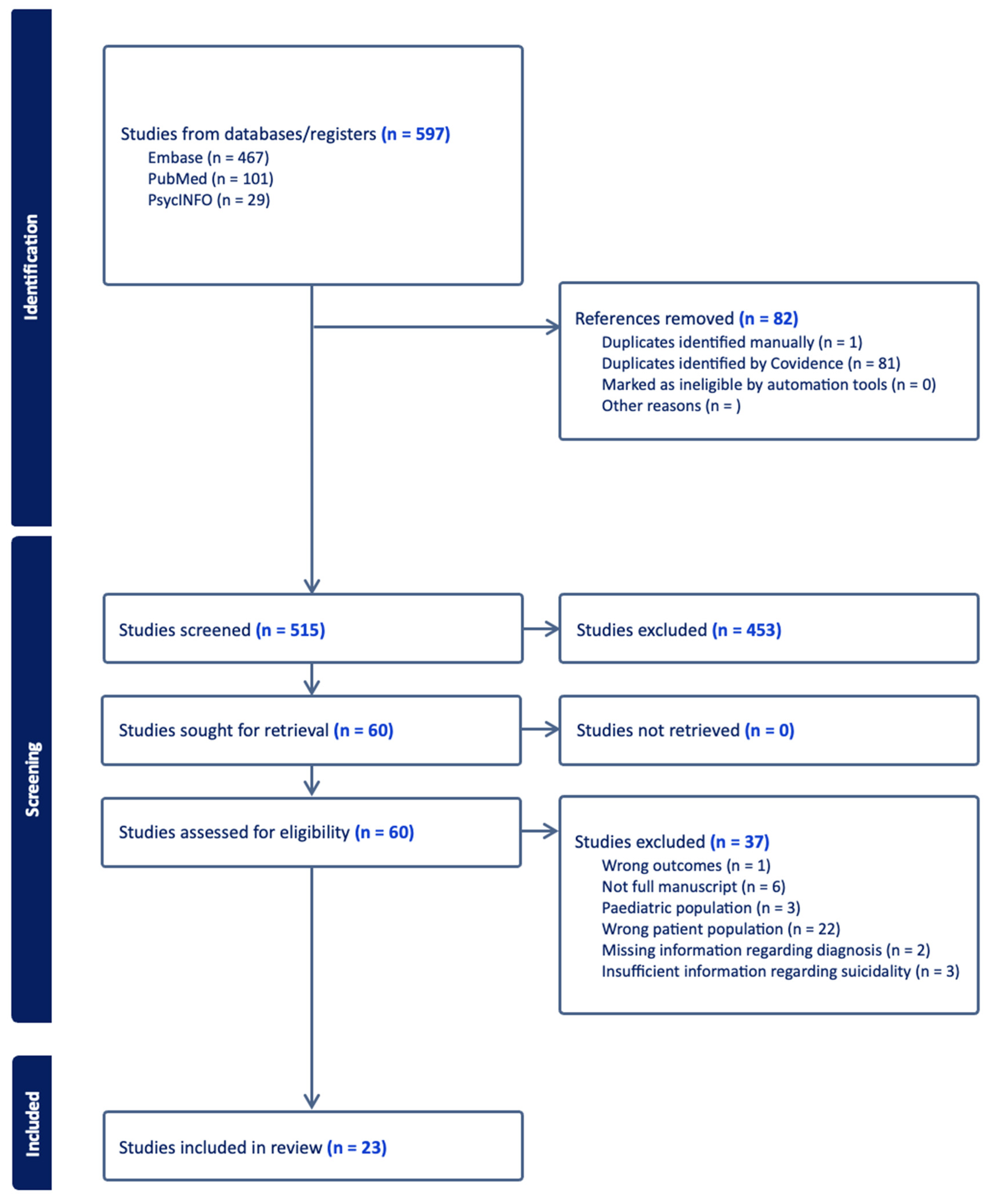

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Findings:

3.2. Key Findings

4. Discussion

Limitations

Implications

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Habtewold TD, Rodijk LH, Liemburg EJ, Sidorenkov G, Boezen HM, Bruggeman R, et al. A systematic review and narrative synthesis of data-driven studies in schizophrenia symptoms and cognitive deficits. Transl Psychiatry 2020, 10, 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Solmi M, Seitidis G, Mavridis D; et al. Incidence, prevalence, and global burden of schizophrenia - data, with critical appraisal, from the Global Burden of Disease (GBD) 2019. Mol Psychiatry 2023, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kendhari J, Shankar R, Young-Walker L. A Review of Childhood-Onset Schizophrenia. Focus J Life Long Learn Psychiatry 2016, 14, 328–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- HARVEY PD, STRASSING M. Predicting the severity of everyday functional disability in people with schizophrenia: cognitive deficits, functional capacity, symptoms, and health status. World Psychiatry 2012, 11, 73–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckley PF, Miller BJ, Lehrer DS, Castle DJ. Psychiatric Comorbidities and Schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull 2009, 35, 383–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullah HM, Azeb Shahul H, Hwang MY, Ferrando S. Comorbidity in Schizophrenia: Conceptual Issues and Clinical Management. FOCUS 2020, 18, 386–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hor K, Taylor M. Suicide and schizophrenia: a systematic review of rates and risk factors. J Psychopharmacol Oxf Engl 2010, 24 (Suppl. S4), 81–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bushe CJ, Taylor M, Haukka J. Mortality in schizophrenia: a measurable clinical endpoint. J Psychopharmacol Oxf Engl 2010, 24 (Suppl. S4), 17–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pompili M, Amador XF, Girardi P, Harkavy-Friedman J, Harrow M, Kaplan K, et al. Suicide risk in schizophrenia: learning from the past to change the future. Ann Gen Psychiatry 2007, 6, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai W, Liu ZH, Jiang YY, Zhang QE, Rao WW, Cheung T, et al. Worldwide prevalence of suicidal ideation and suicide plan among people with schizophrenia: a meta-analysis and systematic review of epidemiological surveys. Transl Psychiatry 2021, 11, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Sher L, Kahn RS. Suicide in Schizophrenia: An Educational Overview. Medicina (Mex) 2019, 55, 361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bornheimer, LA. Suicidal Ideation in First-Episode Psychosis (FEP): Examination of Symptoms of Depression and Psychosis Among Individuals in an Early Phase of Treatment. Suicide Life Threat Behav 2019, 49, 423–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carlborg A, Winnerbäck K, Jönsson EG, Jokinen J, Nordström P. Suicide in schizophrenia. Expert Rev Neurother 2010, 10, 1153–1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fatemi SH, Folsom TD. The Neurodevelopmental Hypothesis of Schizophrenia, Revisited. Schizophr Bull 2009, 35, 528–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bornheimer LA, Nguyen D. Suicide among individuals with schizophrenia: A risk factor model. Soc Work Ment Health 2016, 14, 112–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, AS. Prenatal Infection as a Risk Factor for Schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull 2006, 32, 200–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varese F, Smeets F, Drukker M, Lieverse R, Lataster T, Viechtbauer W, et al. Childhood adversities increase the risk of psychosis: a meta-analysis of patient-control, prospective- and cross-sectional cohort studies. Schizophr Bull 2012, 38, 661–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arseneault L, Cannon M, Fisher HL, Polanczyk G, Moffitt TE, Caspi A. Childhood trauma and children’s emerging psychotic symptoms: A genetically sensitive longitudinal cohort study. Am J Psychiatry 2011, 168, 65–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fusar-Poli P, Borgwardt S, Bechdolf A, Addington J, Riecher-Rössler A, Schultze-Lutter F, et al. The psychosis high-risk state: a comprehensive state-of-the-art review. JAMA Psychiatry 2013, 70, 107–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinberger, DR. Future of Days Past: Neurodevelopment and Schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull 2017, 43, 1164–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velthorst E, Fett AKJ, Reichenberg A, Perlman G, van Os J, Bromet EJ, et al. The 20-Year Longitudinal Trajectories of Social Functioning in Individuals With Psychotic Disorders. Am J Psychiatry 2017, 174, 1075–1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mathalon DH, Hoffman RE, Watson TD, Miller RM, Roach BJ, Ford JM. Neurophysiological Distinction between Schizophrenia and Schizoaffective Disorder. Front Hum Neurosci. 2010, 3, 70. [Google Scholar]

- Amann BL, Canales-Rodríguez EJ, Madre M, Radua J, Monte G, Alonso-Lana S, et al. Brain structural changes in s chizoaffective disorder compared to schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2016, 133, 23–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rostom A, Dubé C, Cranney A; et al. Appendix D. Quality Assessment Forms. In Celiac Disease [Internet]; Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US), 2004; Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.

- Liang M, Guo L, Huo J, Zhou G. Prevalence of sleep disturbances in Chinese adolescents: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLOS ONE 2021, 16, e0247333. [Google Scholar]

- Lyu J, Zhang J, Hennessy DA. Characteristics and Risk Factors for Suicide in People with Schizophrenia in Comparison to Those without Schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res. 2021, 304, 114166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olfson M, Stroup TS, Huang C, Wall MM, Crystal S, Gerhard T. Suicide Risk in Medicare Patients With Schizophrenia Across the Life Span. JAMA Psychiatry 2021, 78, 876–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xia H, Zhang G, Du X, Zhang Y, Yin G, Dai J, et al. Suicide attempt, clinical correlates, and BDNF Val66Met polymorphism in chronic patients with schizophrenia. Neuropsychology 2018, 32, 199–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang Q, Wu D, Rong H, Wu Z, Tao W, Liu H, et al. Suicide ideation, suicide attempts, their sociodemographic and clinical associates among the elderly Chinese patients with schizophrenia spectrum disorders. J Affect Disord 2019, 256, 611–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Morinigo JD, Fernandes AC, Chang CK, Hayes RD, Broadbent M, Stewart R, et al. Suicide completion in secondary mental healthcare: a comparison study between schizophrenia spectrum disorders and all other diagnoses. BMC Psychiatry 2014, 14, 213. [Google Scholar]

- Lang X, Trihn TH, Wu HE, Tong Y, Xiu M, Zhang XY. Association between TNF-alpha polymorphism and the age of first suicide attempt in chronic patients with schizophrenia. Aging 2020, 12, 1433–1445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acosta FJ, Navarro S, Cabrera B, Ramallo-Fariña Y, Martínez N. Painful insight vs. usable insight in schizophrenia. Do they have different influences on suicidal behavior? Schizophr Res. 2020, 220, 147–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bani-Fatemi A, Graff A, Zai C, Strauss J, De Luca V. GWAS analysis of suicide attempt in schizophrenia: Main genetic effect and interaction with early life trauma. Neurosci Lett. 2016, 622, 102–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nath S, Kalita KN, Baruah A, Saraf AS, Mukherjee D, Singh PK. Suicidal ideation in schizophrenia: A cross-sectional study in a tertiary mental hospital in North-East India. Indian J Psychiatry 2021, 63, 179–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu JH, Zhu C, Zheng K, Tang W, Gao LL, Trihn TH, et al. MTHFR Ala222Val polymorphism and clinical characteristics confer susceptibility to suicide attempt in chronic patients with schizophrenia. Sci Rep. 2020, 10, 5008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu J, Chan LF, Souza RP, Tampakeras M, Kennedy JL, Zai C, et al. The role of tyrosine hydroxylase gene variants in suicide attempt in schizophrenia. Neurosci Lett. 2014, 559, 39–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu CL, Kao YC, Thompson T, Brunoni AR, Hsu CW, Carvalho AF, et al. The association of total pulses with the efficacy of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation for treatment-resistant major depression: A dose-response meta-analysis. Asian J Psychiatry 2024, 92, 103891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- İngeç C, Evren Kılıçaslan E. The effect of childhood trauma on age of onset in patients with schizophrenia. Int J Soc Psychiatry 2020, 66, 763–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng P, Ju P, Xia Q, Chen Y, Li J, Gao J, et al. Childhood maltreatment increases the suicidal risk in Chinese schizophrenia patients. Front Psychiatry 2022, 13, 927540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aydın M, İlhan BÇ, Tekdemir R, Çokünlü Y, Erbasan V, Altınbaş K. Suicide attempts and related factors in schizophrenia patients. Saudi Med J. 2019, 40, 475–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadzadeh A, Azadi S, King S, Khosravani V, Sharifi Bastan F. Childhood trauma and the likelihood of increased suicidal risk in schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res. 2019, 275, 100–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prokopez CR, Vallejos M, Farinola R, Alberio G, Caporusso GB, Cozzarin LG, et al. The history of multiple adverse childhood experiences in patients with schizophrenia is associated with more severe symptomatology and suicidal behavior with gender-specific characteristics. Psychiatry Res. 2020, 293, 113411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kilicaslan EE, Esen AT, Kasal MI, Ozelci E, Boysan M, Gulec M. Childhood trauma, depression, and sleep quality and their association with psychotic symptoms and suicidality in schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res. 2017, 258, 557–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Etchecopar-Etchart D, Korchia T, Loundou A, Llorca PM, Auquier P, Lançon C, et al. Comorbid Major Depressive Disorder in Schizophrenia: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Schizophr Bull 2020, 47, 298–308. [Google Scholar]

- Ribeiro JD, Huang X, Fox KR, Franklin JC. Depression and hopelessness as risk factors for suicide ideation, attempts and death: meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Br J Psychiatry 2018, 212, 279–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor PJ, Gooding PA, Wood AM, Johnson J, Pratt D, Tarrier N. Defeat and entrapment in schizophrenia: The relationship with suicidal ideation and positive psychotic symptoms. Psychiatry Res 2010, 178, 244–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qin P, Agerbo E, Mortensen PB. Suicide risk in relation to family history of completed suicide and psychiatric disorders: a nested case-control study based on longitudinal registers. The Lancet 2002, 360, 1126–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janiri D, Rossi PD, Kotzalidis GD, Girardi P, Koukopoulos AE, Reginaldi D, et al. Psychopathological characteristics and adverse childhood events are differentially associated with suicidal ideation and suicidal acts in mood disorders. Eur Psychiatry 2018, 53, 31–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Study | Country | Study Design | Sample Size | Population characteristics | Developmental Predictors | SI metric | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acosta 2020 | Spain | Cross sectional | 133 | Outpatients Age: 46.7 (10.3) Gender: 69.2% M |

SES | CDS | SA and SI groups exhibited higher SES versus non-suicidal group. |

| Aydın 2019 | Turkey | Retrospective | 223 | Inpatients Age and Gender of suicide group: 41.0 ± 10.6 46% M |

Family hx of psychotic disorder, Lifetime traumatic event |

SA | No group difference in family hx. Significant difference in trauma type between SA and non-SA groups |

| Bani-Fatemi 2016 | Canada | Cross sectional | 121 | Inpatients Age: 45.3 ± 11.7 Gender: 65.5% M |

Ethnicity, CT; genetics/trauma interaction |

C-SSRS; BSSI | White Europeans higher likelihood of SA. General abuse strongly linked to suicidal behavior. GWAS suggests interaction between SNPs and early CT but no genome-wide significance for SA in SZ |

| Bani-Fatemi 2018 | Canada | Cross sectional | 123 | Outpatients Age: 44.7 ± 12.3 Gender: 70% M |

genetics | C-SSRS; BSSI | Methylation at various gene regions differed between SZ patients with and without a history of SA |

| Bani-Fatemi 2020 | Canada | Cross sectional | 107 | Outpatients Age: 44.58 ± 9.14 Gender: 63.2% M |

genetics | CDS | Increased methylation of the SMPD2 gene was observed among individuals with SI |

| Chang 2019 | China | Retrospective | 263 | Inpatients Age: 64.11 ± 3.87 Gender: 19.1% M |

SES/demographic; Other: Fam hx of serious psychiatric problem; CT; environmental factors |

SA | SA in SZ linked to poor family relationships. No connection to other SES factors. Traumatic life events higher among SA patients. |

| Cheng 2022 | China | Cross sectional | 91 | Inpatients Age: 31.00 ± 7.78 Gender: 51.2% M |

Childhood abuse/maltreatment; Early adversity |

Beck’s suicide intent scale, nurses’ global assessment of suicide risk | Emotional neglect predicted suicide risk and SI, influenced by BMI linked to SMI. Relapse patients exhibit more CT and stress, uniquely associated with increased SI |

| Hu 2014 | Canada | Case-control | 234 | Outpatients Age: 28.39 ± 9.1 Gender: 50% M |

Genetics; SES/demographic |

SA | TH gene TCAT[6] allele linked to 15-fold increased SA risk; TCAT[8] allele may be protective. |

| İngeç 2020 | Turkey | Cross sectional | 200 | patients Age: 31.00 ± 7.78 Gender: 51.2% M |

CT | MINI | All types of CT increase the risk of suicide |

| Kilicaslan 2017 | Turkey | Cross sectional | 200 | Inpatient and outpatient Age: 40.42 ± 11.20 Gender: 68.3% M |

Childhood abuse/maltreatment; Early adversity; Family history of SI; Family history of SZ |

MINI | CT predictive of SZ symptoms but not found significant predictor of SI. |

| Lang 2020 | China | Cross sectional | 1087 | Inpatient Age: 47.8 ± 10.2 Gender: 81.9% M |

Genetics |

SA | No significant association was found between TNF-alpha gene polymorphisms and SZ or SA. The -1031C>T polymorphism linked to the age of first SA |

| Liu 2020 | China | Cross sectional | 957 | Inpatients Age: 47.8 ± 10.2 Gender: 81.8% M |

Genetics | SA | The MTHFR polymorphism showed a weak correlation with SA in SZ. The Val/Val genotype was more prevalent among attempters. |

| Lopez-Morinigo 2014 | UK | Retrospective | 54 | Outpatient Age: 39.3 ± 11.9 Gender: 70.3% M |

demographic info | Death by suicide | SZ suicide deaths were often younger, of Black origin, English as a first language, and more socially deprived compared to non-SZ suicide deaths. |

| Lyu 2021 | China | Psychological Autopsy (PA) | 38 | Survey Age: 29.03±5.592 Gender: 39.5% M |

SES; environmental factors | Death by suicide | No significant differences in education, residence, marital status, living alone, or family size between SZ and non-SZ suicide groups, but significant differences in age and gender, with female patients more likely to die by suicide. Lower levels of social support in SA groups. |

| Mohammadzadeh 2019 | Iran | Cross sectional | 82 | Inpatient Age: 34.78 ± 9.10 Gender: 41.5% M |

CT | BDI; BSSI | High levels of CT linked to more severe SI. Genderual abuse was a unique predictor of lifetime SA, while physical neglect and depression unique predictors of current SI |

| Nath 2021 | India | Cross sectional | 140 | Inpatients Age: 31.17 ± 8.5 54.3% M |

fam hx, SES | ISST | SI was significantly associated with a family hx of psychiatric illness (especially SZ), and suicide. no relationship with SES factors |

| Olfson 2021 | United States | Retrospective | 668,836 | Medicare beneficiaries Gender: 52.5%M |

resources/medicare/ SES | Death by suicide | Medicare patients with SZ had a 4.5-fold increased risk of suicide, with higher risk for men, Whites. |

| Prokopez 2020 | Argentina | Cross sectional | 100 | Inpatients Age: 45.82 (±12.68) Gender: 50% M |

CT | C-SSRS | Women with ≥5 ACEs had higher death ideation, SA frequency, and SA median numbers. Emotional abuse most common ACE in SZ. |

| Taktak 2023 | Turkey | Cross sectional | 222 | Outpatients Age: 45.92 ± 12.31 Gender: 70.27% M |

SES | SBQ-R | Higher SI associated with high school education and lower income |

| Xia 2018 | Turkey | Retrospective | 223 | Inpatient Age: 48.1 9.6 years) Gender: 84% M |

SES/CT | SA | Marital status, gender, employment, education, family history of psychiatric illness, cohabitation, and living situation were not linked to SA. Traumatic life event history was higher in those with past SA. |

| Xie 2018 | China | Cross sectional | 216 | Outpatients Age: 27.78 ± 8.13 Gender: 55.5% M |

CT | SIOSS | SI positively correlated with CT severity and variety; inversely related to social support. |

| Yu 2024 | China | Cross sectional | 281 | Inpatients Gender: 58.7% M |

CT/environmental factors | PHQ-9; SIOSS | CT and psychological resilience influenced the onset of SI in SZ |

| Zhang 2021 | Canada | Cross sectional | 83 | Inpatients Age: 38.39 ± 10.23 Gender: 54% M |

CT/physical neglect | BSSI | SI was related to insomnia and CT, with physical neglect identified as an independent risk factor. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).