1. Introduction

Social and economic changes have led to different family patterns. Contemporary families have fewer members, women give birth to their first child later, and they combine motherhood with full-time work (Polianova, 2018). In economically developed countries, parenthood is considered a personal decision. The ideal of a family with two children has been maintained in Europe for decades (Sobotka & Beaujouan, 2014). However, the number of children in each family is influenced by numerous factors, such as social norms and the social structure of society (Bernardi & Klarner, 2014), as well as governmental support and religious beliefs. According to data from the National Bureau of Statistics, in Croatia, women give birth to their first child at the age of 30, and in 2011, the average household consisted of 2,80 members. The delay in starting a family appears to be partially rooted in financial insecurity (Mills & Blossfeld, 2005) since employed individuals are more inclined to have children, as well as those who are legally married (compared to non-official long-term relationships), according to Varas and Borsa (2021). Practising religion is associated with acceptance of family values (Miller & Pasta, 1995), and lower perceived costs of having children (Bein et al., 2020). Individuals in a romantic relationship tend to report higher positive motivation for parenthood. Similarly, legal marriage is also related to positive motivation, just like employment.

1.1. Motivation for Parenting

Motivation for parenting is based on an individual’s assessment of the possible consequences of having or not having children (Miller, 1995). Rabin (1965) defined parents’ expectations of their children and the needs their children will meet. He also suggested four parenting motivation categories: altruistic, fatalistic, narcissistic and instrumental. In one domestic research, altruistic motivation was the most prominent among Croatian students, especially females (Petani & Babačić, 2010). His theory, however, lacked the strength to elaborate on the reasons that deter individuals from having children. Hoffman and Hoffman (1973) further listed nine values of a child, which Kohlmann (2002) revised into three aspects: economic security, ensuring social position and emotional love.

Miller (1995) developed the T-D-I-B (Traits-Desires-Intentions-Behaviour) theoretical framework based on three assumptions. Firstly, our biological tendencies determine our reaction to children and nurturing. Secondly, parenting preferences are shaped by individual experiences in childhood and early adulthood, creating two general motivational forces (positive and negative attitudes towards the birth and upbringing of children). The third assumption is that these motivational forces influence behaviour, meaning parenting (Miller, 1995). Research by Mynarska and Rytel (2018) confirms the main assumptions of the model, but in different cultural context (see Irani & Khadivzadeh, 2018), this theory was not supported.

Another theoretical framework would be the Theory of Planned Behavior (Ajzen, 2001). According to this theory, behaviour can best be predicted by measuring intentions that consist of attitudes, subjective norms and perceived behavioural control. Thus, more positive attitudes and societal norms towards childbirth, accompanied by a higher level of perceived control over childbirth, will lead to higher motivation for parenting. According to research, the intentions against having children are a stronger predictor (Kuhnt & Trappe, 2013), partially because it is more difficult to conceive than to use contraception. Freitas & Testa (2021) find that positive intentions predict having children better than the use of contraception. The most significant determinants of positive intentions are a stable partner relationship, stable employment, and social pressure from family and friends. Morgan and Bachrach (2011) critiqued this notion, stating that the intention grows gradually and thus cannot be measured only once. Different personal constructs, such as attachment styles, emotional competencies, and religiousness, might predict the desire for offspring. We further describe their components and their relation to parental motivation.

1.2. Attachment Styles

Attachment develops through three stages, from non-discriminatory social interactions to separation anxiety and reciprocal relationships. Ainsworth (1969) developed a theory about three main attachment styles: anxious-avoidant, secure, and anxious-resistant. However stable, early attachment patterns can be changed through experiences in romantic and friendly relationships (Umemura et al., 2017). Attachment styles (AS) are vital for establishing and maintaining long-term romantic relationships in adulthood. Insecure Attachment leads to less satisfaction in romantic relationships, which is the main predictor of relationship quality (Conroy-Beam et al., 2015). Despite dissatisfaction in the relationship, insecurely attached people try to maintain their relationship and are more inclined to use negative partner retention strategies (Nascimento et al., 2022). Avoidance is negatively related to motivation for parenthood and the desired number of children (Međedović et al., 2022), while securely attached individuals show a greater interest in infants (Cheng et al., 2015).

1.3. Emotional Intelligence

As defined by Salovey and Mayer (1990), emotional intelligence (EI) represents the ability to recognise, express and monitor emotions and use them to facilitate cognitive processes. Their model includes four primary abilities, ordered according to the complexity of psychological processes: the ability to evaluate and express emotions, the ability to perceive and generate feelings that facilitate thinking, the ability to understand the knowledge about emotions, and the ability to regulate emotions for emotional and intellectual development (Mayer & Salovey, 1997). More complex abilities of EI develop with age and experience (Vučenović & Hajncl, 2018). EI is a significant predictor of individual adjustment in different aspects of life. Namely, emotional regulation predicts satisfaction in marriage (Bloch et al., 2014) and romantic relationships (Malouff et al., 2014). Emotionally intelligent mothers consider themselves more successful in their maternal role (Mammadov & Erenel, 2021). Future parents with higher emotional intelligence show fewer symptoms of depression and anxiety during pregnancy (Formica et al., 2020). The results by Apostolou et al. (2019) indicate that EI individuals are more committed to their partners (Kaur & Junnarkar, 2017). However, the relationship between EI and parenting motives remains unclear due to insufficient research.

1.4. Research Aims and Hypothesis

It is still unknown how individuals approach decisions related to reproductive behaviour and starting a family since individual differences contributing to developing positive and negative motivations for parenthood are not precisely defined. Having such sparse insight into what predicts motivation, especially for females in early adulthood, we set out to determine the increment value of predominantly personal factors to describe the motivation for parenthood among female students in Croatia, a Western upper middle-income country.

Specifically, we aim to examine the levels of positive and negative motivation for parenthood in our sample (1), test the relations between the dimensions of attachment, the abilities of emotional intelligence, religiosity and motivation for parenting (2), examine the intentions related to having children, such as the desired number, the ideal age for starting the family, contraception use and attitudes toward the women who choose a children-free lifestyle and enquire into possible dereferences regarding sexual orientation and relationship status (3). Finally, we asked participants to rate different demographic measures based on their importance in the decision to have a child (4). Based on the limited theoretical background, we assume that positive motivation for parenting will be linked to lower anxiety and avoidance, more prominent EI domains and religiousness. On the contrary, negative motivation is expected for more anxious and avoidant AS, low EI and non-religious tendencies. Regarding their intentions, we could hypothesise that participants will reflect current trends such as starting a family at the age of 30, having two children and being using contraception to prevent unwanted pregnancies.

2. Materials and Method

2.1. Participants

Data was collected from a total of 234 female students. We excluded male participants since females make most birth-related decisions in societies with a more equal approach to parenting. Over 90% of them studied at the University of Zagreb, predominantly social sciences (66.7%), followed by humanities (12.4%), biomedicine and healthcare (7.7%). The age range was 20 to 31 years, with an average age of 23.29 (SD = 2.34). Most of the participants (90.6%) were heterosexual, and the rest consisted of sexual minorities, such as bisexuals (8.1%) and homosexuals (1.3%). According to the relationship status, 47.4% of the participants were currently single, 43.2% were in a relationship longer than six months, 8.5% were in a relationship shorter than six months, and 0.9% were married. Around 34% of participants are residents of the Capital (Zagreb). They are estimated to have mostly average (39.3%) or slightly lower than average (23.9%) living standards. Around 45% are currently not employed. Around 32% of them are not very religious, while almost 28% are very religious.

2.2. Instruments

Socio-demographic data, including gender, age, sexual orientation, romantic status, study, residence (by number of inhabitants), place of birth (rural-urban), current work status and living standard, were set to determine the more general characteristics of our sample. Religiosity was assessed using a one-item measure (On a scale of 1 to 10, how would you rate yourself in terms of religiosity?), as seen in the European Social Survey, the basic questionnaire (sections C and F, 2020/2021).

The Revised Adult Attachment Scale (Collins, 1996) consists of 18 items evenly distributed in three subscales representing attachment dimensions: closeness, dependence and anxiety. Participants rate their answers on a Likert-type scale from 1 to 5. We used the version that refers to behaviour in all close relationships. The subscale results represent the average score. An alternative way of scoring allows the assessment of four attachment styles. Collins (2001) reports reliability between 0.77 and 0.85, while we found similar (0.73- 0.89).

Emotional competence questionnaire (UEK-45; Takšić, 2002) measures emotional competence based on the model of Mayer and Salovey (1999). It contains 45 items divided into three subscales: the ability to perceive and understand emotions (15 items), the ability to express and name emotions (14 items) and the ability to manage emotions (16 items). Participants rate their usual thoughts and feelings on a Likert scale from 1 to 5, and the total scores can be easily obtained by summing the scores. We encountered reliability coefficients between 0.77 and 0.93.

The Childbearing Motivation Scale (Guedes et al., 2015) consists of 47 items measuring positive and negative motivation levels for having children. The subscale of positive motivation includes 26 items (e.g., giving meaning to your life), which are grouped according to the factor model of four factors of positive motivation for having children: socioeconomic aspects, continuity, personal fulfilment and couple relationship. The negative motivation subscale includes 21 items (e.g., Feeling that I do not have the necessary qualities to become a mother) grouped according to the factor model of five factors: the burden of upbringing and immaturity, social and environmental concerns, marital stress, financial problems and economic constraints and physical suffering and concern about body appearance. The items are rated on a Likert scale (1-5), and the total scores represent the average value. Reliability coefficients range between 0.76 and 0.95. The scale was translated using a back-translation procedure (Sousa & Rojjanasrirat, 2011).

2.3. Procedure

The research was conducted online after we received ethical approval and permission from different authors from the Instrument’s section. Following a snowball method, we approached participants through social media and platforms such as Reddit. The instruction clearly stated the research aims and emphasized the scientific use of the collected data and data protection. After the formal content, we introduced two exclusion criteria questions about gender and student status. On average, participants responded within 20 minutes.

2.4. Ethical Considerations

The study was conducted following the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki after receiving approval from the Department for Psychology Council (Klasa: 640-16/23-2/000; Ur. broj: 380-58/506-23-0007). After clarifying the aims of the following study, all participants provided explicit informed consent.

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics

All analyses were conducted using SPSS V.22.

Table 1 presents the descriptive data collected in the research. The mean values obtained on the scales of positive and negative motivation for parenting were close to the middle of the theoretical ranges (PM=2.79, SD = 0.86, NM=2.89, SD=0.98). On the emotional competencies scale, they express above-average levels for 2 out of 3 abilities, and their religiosity is moderate. Participants’ emotional competencies are grouped at around 0-0,63 z value for the student population, and they exhibit average scores even for population norms (females only). Data show distribution deviations in all variables except positive motivation for parenting. Nevertheless, all variables’ asymmetry (skewness) and kurtosis values range from -1 to 1. Considering the sample size, this justifies the use of parametric tests (Field, 2013).

3.2. Correlation Analysis and Forecasting Parental Motivation

Pearson’s correlation coefficients are present in

Table 2 and

Table 3. Positive motivation for parenting is closely related to religiosity (r=0.49, p<0.01) and significantly lower with the ability to perceive and understand emotions (r=0.14, p<0.01). On the subscale level, personal fulfilment correlates to the management of emotions (r=0.24, p<0.05), along with continuity (r=0.19, p<0.05) and the couple relationship (r=0.25, p<0.05). Negative motivation yielded a more significant bivariate correlation, namely, with all three attachment dimensions and EI, and managing emotions as the strongest predictor (r=-0.38, p<0.05), similar to religiosity (r=-0.37, p<0.05).

The next step was to conduct a multiple linear regression analysis for all selected predictors and two separate criterion analyses. Given the absence of correlations between positive motivation for parenting and adult attachment dimensions, they were omitted from the regression model. The results are presented in

Table 4 and

Table 5, respectively.

The regression model for the positive motivation criterion was statistically significant, as it explained 27.7% of the variance (R²=0.277, F=21.907, p<0.05). The most significant predictor variable was religiosity, and management of emotions was the only EI ability that altered the effect size (β=0.159, p<0.05). The model for negative motivation was also statistically significant and explained 28.7% of the variance (R²=0.287, F=13.024, p<0.05). Not a single adult attachment dimension proved its predictive value. Again, emotional management (β=-0,235, p < 0,05) and religiosity were the most significant predictors (β = -0.339, p < 0.05). Differences based on relationship status will be address in the discussion section.

3.3. Planned Behavior, Parental Intentions, and the Role of Demographic Incentives

Most of our participants believe that the ideal age for a woman to become a mother for the first time is between 25 and 29 years (62.9%) or 30 to 35 years later. Only a minority believes there is

no such thing as an ideal age (9,8%). Almost 50% of participants plan to have two children, and almost 30% want three or more, while only 13% express no desire to have a child. Half of students use contraception during every intercourse (50.9%), opposite to 26.5% who never use contraceptives. They render sufficient support for females who choose not to have children (M=4.38, SD=1.06). When inspected, these variables show low or moderate but significant correlations (

Table 6).

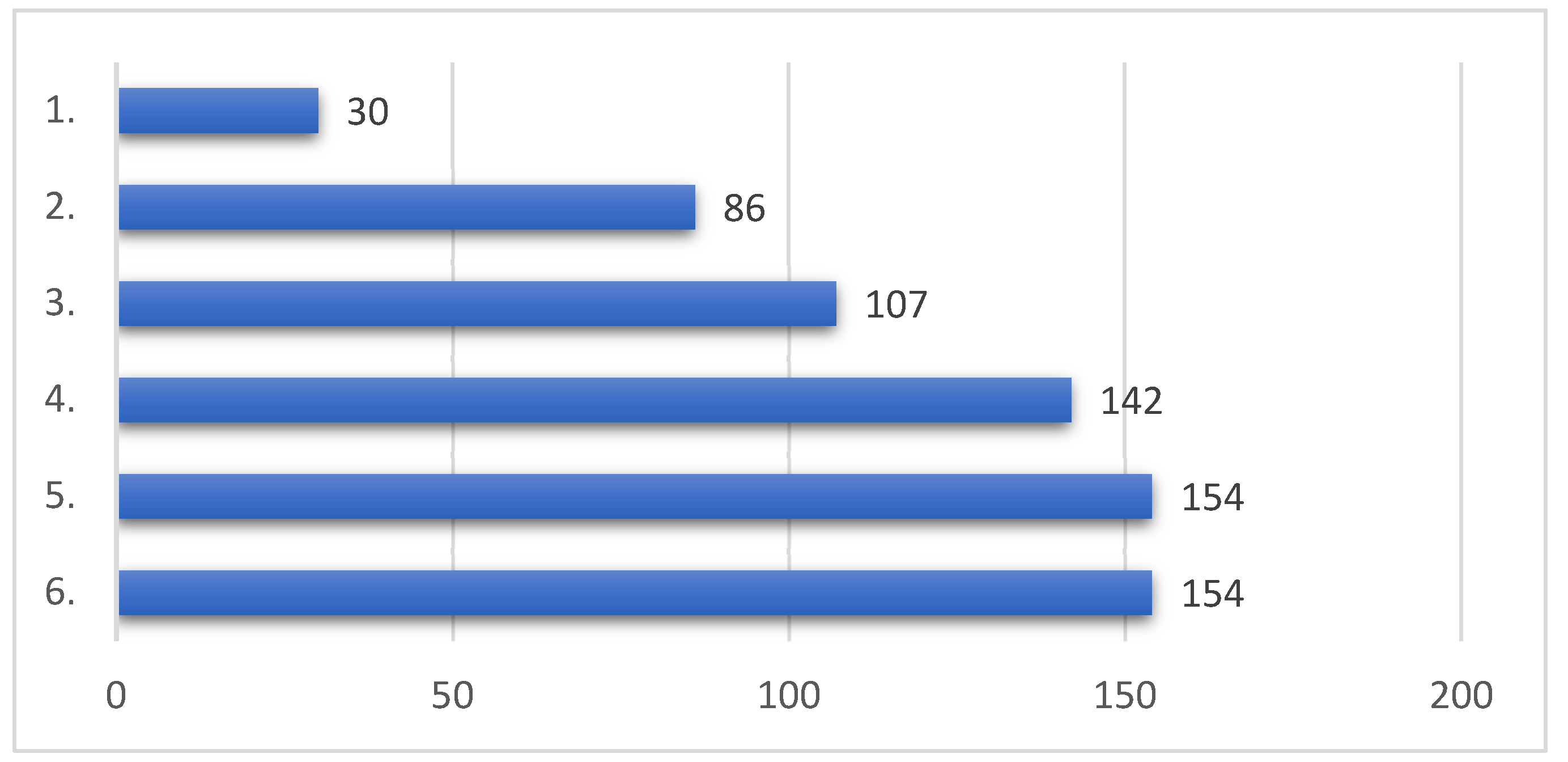

Lastly, we asked our participants to rate demographic policies and measures that would encourage them to have more children than planned, and the results are presented in

Figure 1.

4. Discussion

4.1. Addressing the Descriptive Parameters and Indicators

This research examined the role of adult attachment and emotional intelligence in predicting positive and negative motives for having offspring. According to our data, female students express moderate levels of positive and negative motivation to an equal extent, which contradicts prior research (Fiskin & Sari, 2021; Varas & Borsa, 2021). The most pronounced motives are personal fulfilment, such as the meaning of life (positive motivation), and social and environmental concerns, including environmental devastation and social dangers (negative motivation). This is aligned with a quote from Van der Walt (2019), stating that students were still exploring their sense of purpose and meaning in life, making it their priority. Over and above that, students are particularly interested in and dedicated to their mental health and well-being, which are forcibly related to finding meaning. On a more environmental note, results obtained by Rončević & Cvetković (2016) proclaim that most older and female students support slower economic development, accompanied by stronger environmental protection or holistic ethos type. The least prominent motives were socioeconomic aspects (positive motivation) and marital stress (negative motivation), corresponding to the fact that only 0.9% of female students are married. Socioeconomic concerns not being a vital influence on the verge of global recession is an unusual finding, particularly when combined with the fact that 44,4% of our sample is unemployed and 39,7% of students estimated their standard of living as below average. Sonield et al. (2013) speculate that positive motivation stems from having enough time to prepare for or plan for a child, in contrast to unexpected pregnancies. unplanned birth. However, few findings advocate a more pronounced negative motivation in women (Mynarska & Rytel, 2020) and emphasize the role of age and cultural context. This conclusion can be supported by claims made by Duvander et al. (2020), expressing how both partners influence the intent to have a child, but women are more influential in the decision on the number of children, interpreted in terms of cost and utility analysis.

4.2. Addressing the Correlation Analyses and Predictive Value of Personal Factors

Positive and negative motivation for parenting manifested strong correlations with self-reported religiosity, similar to another research (Varas & Borsa, 2021). Unexpected findings mostly refer to the nonsignificant relationship between adult attachment dimensions and positive motives for having a child, while the correlations between adult attachment dimensions and negative motivation are in the expected direction. Like Međedović et al. (2022), whose study involved both genders with an average age of 42, anxiety was negatively related to reproductive motivation as secure romantic bonding is evolutionarily adaptive. Two EI dimensions, the ability to express and name emotions and the ability to manage emotions, were significantly related to negative but not positive motivation for parenting. Although our initial hypothesis was partially rejected, it was based on a small amount of available research that indirectly assesses the relationship between emotional intelligence and parenting (Mammadov & Erenel, 2021). One plausible explanation relies on the notion that EI is vital when dealing with challenges, and the scale of negative motivation emphasizes possible difficulties when raising a child (Kaur & Junnarkar, 2017). Two EI dimensions, the ability to express and name emotions and the ability to manage emotions, were significantly related to negative but not positive motivation for parenting. This conclusion refutes the idea that self-report scales are often highly correlated due to shared method variance. Roberts et al. (2010) question self-assessment measures due to various biases and the problem of insight. Respondents do not have to be in contact with their emotions, so giving realistic assessments without overlapping personality traits is exigent. In other words, compared to attitudes about parenting, assessing our emotional abilities could be more challenging. Although our initial hypothesis was partially rejected, only a few available research indirectly assessed the relationship between emotional intelligence and parenting (Mammadov & Erenel, 2021). One plausible explanation relies on the notion that EI is vital when dealing with challenges, and the scale of negative motivation emphasizes possible difficulties when raising a child (Kaur & Junnarkar, 2017). Based on these results only, management of emotions could indicate an individual’s (im)maturity.

Searching for the best personal predictors of childbearing motivation, our expectations were grounded on research on sexual risk and attitudes (McElwain et al., 2015). Attachment dimensions may work to develop certain behaviours that predict parenting motivation. Emotion regulation and management are statistically significant predictors of both positive and negative parenting motivation. Given that the abilities to regulate and manage emotions are more complex abilities of emotional intelligence, we can assume that the most complex abilities are crucial when assessing our capabilities for being a parent since EI women are considered more successful in the role of mother (Mammadov & Erenel, 2021). Even without the experience, they could feel more prepared to face the challenges of parenthood or in general. Religiosity best predicts positive and negative parenting motivations, which aligns with other consistent findings (Varas & Borsa, 2021). Religious individuals report greater benefits and fewer costs associated with childbearing (Bein et al., 2015). They are socialized to accept family values, namely the importance of having children (Pearce & Davis, 2016). Women who practice religion, especially Catholic, give birth to more children than non-religious women (Peri-Rotem, 2016). After a more detailed dive into differences based on relationship status, positive motivation for those in a relationship or married can be predicted predominantly by religiosity. At the same time, the negative is contingent on religiosity and the dependence dimension of attachment, meaning that children could act as a closeness amplifier. For single females, positive motivation was marked by religiosity, sexual orientation, age, anxiety and emotional management, and similarly, negative motivation was antedated by religiosity, contraception usage and emotional management (

Table 6). Thus, the hypothesized model was more successful in predicting the motivation of single females.

4.3. Addressing the Parental Intentions in Early Adulthood and the Role of Demographic Incentives

The majority of our sample intends to have two children, a more prominent trend for decades (Sobotka & Beaujouan, 2014). Female students estimate that the ideal age to become a mother is between 25 and 29 years, similar to other reports (Lampic et al., 2006) and corresponds to the Croatian average (DZS, 2023). A combination of low levels of positive motivation and a higher level of negative motivation predicts contraception usage, compliant with previous research (Kuhnt & Trappe, 2014) and Miller’s theory (1995). One of the more optimistic findings, overall support for the decision to not have a child, contrasts the conclusion made by Maftei et al. (2023), where negative attitudes still prevailed among older citizens with children - perhaps due to mechanisms of cognitive dissonance. Correlation analysis reveals that more negative attitudes are expressed by more religious females and those who discern the positive sides of parenthood. The most popular demographic measures refer to ensuring the conditions for having children, that is, ensuring the health care of mother and child and subsidizing housing loans or subletting, which tells us that female students are focused on existential problems. The Republic of Croatia needs many primary care physicians, namely 257 family physicians, 110 gynaecologists and 90 paediatricians (HLJK, 2023).

Furthermore, female students also chose the measure of encouraging fathers to be more actively involved in the care of infants, and such results may be related to more traditional roles in Croatian society and the desire of Croatian female students to change this situation. Research shows that very few fathers take care of children while the mother works, i.e., 90% of fathers in the EU do not take parental leave (Borg, 2018). A small number of female students chose demographic measures related to specific problems related to the financial costs of a child, such as free extracurricular activities and exemption from paying the communal contribution, which may be a consequence of the fact that the female students are not yet familiar with such costs. A smaller number of female students believe that a single-child allowance would encourage them to have children or more children. A possible explanation for these answers is that female students are focused on long-term and higher costs and acquiring the primary conditions for having children.

4.4. Limitations and Future Research

There are several limitations, dilemmas and recommendations for future survey that we would like to express. First of all, religiosity was measured with a single-item scale. Single-item measures are generally not recommended because their reliability cannot be estimated (Wanous & Reichers, 1996). Spector (1991) states that they do tap into complex constructs and demonstrate higher correlations with other variables. Additionally, Allen et al. (2022) assert that single-item measures are parsimonious, less ambiguous, not tiresome, more accessible to administer and suitable for vulnerable or clinical populations. Although our sample was not clinical, due to the length of our questionnaire, we opted to shorten only the religiosity measures, assuming it would hold its face and construct validity. This decision unquestionably limits our conclusions. In respect of instruments, other available options with fewer items and different factor structure, such as Motivation to have a child scale (Brenning et al., 2015) could provide a more relevant data.

Secondly, Morgan and King (2001) speculate that childbearing incentives compete with other interests, making a parenting decision a complex product of biological predispositions, social coercion, and a rational decision-making process. Consequently, it is necessary to further explore the stages of this though-process and more complex social factors, such as family values, societal pressure etc. Thirdly, the analysis we excluded from the final manuscript due to the unequal distribution of categories based on sexual orientation is our next target, since studies show that LGBTIQ people have a significantly lower desire for parenthood than childless heterosexuals (Hank & Wetzel, 2018).

Whether it is suitable to measure childbearing motivation at such a young age remains unresolved. For females in our sample with an average age of 23, who are already invested in the educational process, and half of whom are not even in a romantic relationship, it could be too soon to delve into such intense life decisions. Average values range from 2.18 to 3.47 for positive motivation and 2.15 to 3.41 for negative motivation. Such a small range may indicate that the participants do not yet have a firmly defined attitude or intention regarding parenthood. Our decision not to separate different types of adult attachment (friendship vs. romantic partners) and include those currently not in a romantic relationship perhaps influenced such unexpected outcomes. Based on this assumption, other suggestions are to include variables related to the quality/satisfaction of the romantic relationship or shift towards dyadic measures, influenced by the evidence of how parenthood is, in most cases, a consensual decision. Likewise, the recommendations would be to investigate couples with children and inspect the motives for expanding the families.

5. Conclusions

Our students express positive and negative childbearing motivation at around the same levels, meaning there are no extreme levels since values do not exceed 3.5, nor do they go below 2. Parental intentions are linked to religiosity and emotional management abilities. Positive motives are not related to adult attachment dimensions, unlike negative motives with only low correlations. Both motivations scales can be predicted by religiosity and emotional management. The hypothesized model, including age, contraception usage, sexual orientation, attachment, EI, and religiosity was more successful in predicting the motivation of single females. Age is a significant predictor for positive, and contraception predicts negative motivation among single girls exclusively. Most female students want to have two children and believe that the ideal age for having their first child is between 25 and 29. Half of them use contraception during every intercourse, and about 25% never use it. The vast majority support other women’s decision not to have children. Participant report how having adequate healthcare for both mother and child, housing, and paternal participation in child-rearing practice is essential in their decision-making process.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D. V. and M.P.; Methodology, D.V.; Software, M. P.; Validation, K. J.; Formal Analysis, M.P., K. J.; Investigation, M.P.; Resources, D.V.; Data Curation, M.P. i K.J.; Writing – Original Draft Preparation, M.P.; Writing – Review & Editing, K.J.; Visualization, D.V.; Supervision, D.V.; Project Administration, D.V.

Funding

This research was partially funded by the grants for institutional funding of scientific activities in 2024 (University of Zagreb); project Emotional intelligence: development and application of measuring instruments (code: 2600513).

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We thank our colleagues from the Department of Demography and Croatian Diaspora for guidance on certain socio-demographic items.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Polivanova, K. N. (2018). Modern Parenthood as a Subject of Research. Russian Education & Society, 60(4), 334–347. [CrossRef]

- Sobotka, T.; Beaujouan, E.i. (2014). Two is best? The persistence of a two-child family ideal in Europe. Population and Development Review, 40, 391–419. [CrossRef]

- Bernardi, L.; Klärner, A. (2014). Social networks and fertility. Demographic research, 30, 641-670. [CrossRef]

- https://podaci.dzs.hr/media/fagflfgk/croinfig_2021.pdf.

- Mills, M. C. & Blossfeld, H. P. (2005). Globalization, uncertainty and the early life course: a theoretical framework. In H. P. Blossfeld, E. Klijzing, M. Mills, i K. Kurz (Ur.), Globalization, uncertainty and youth in society (str. 1-24). Routledge.

- Varas, G. V. V. & Borsa, J. C. (2021). Predictor variables of childbearing motivations in Brazilian women and men. Paidéia (Ribeirão Preto), 31, e3112. [CrossRef]

- Miller, W. B. & Pasta, D. J. (1995). Behavioral intentions: Which ones predict fertility behavior in married couples? Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 25(6), 530-555. [CrossRef]

- Bein, C.; Mynarska, M.; Gauthier, A.H. (2021). Do costs and benefits of children matter for religious people? Perceived consequences of parenthood and fertility intentions in Poland. Journal of Biosocial Science, 53(3), 419-435. [CrossRef]

- Miller, W. B. (1995). Childbearing motivation and its measurement. Journal of Biosocial Science, 27(4), 473- 487.

- Rabin, A. I. (1965). Motivation for Parenthood. Journal of Projective Techniques and Personality Assessment, 29(4), 405–413. [CrossRef]

- Petani, R. ; Babačić; A. (2010). Motivacija za roditeljstvom kod studenata Sveučilišta u Zadru。 Acta Iadertina, 7(1), 79-97.

- Hoffman, L. W. & Hoffman, M. L. (1973). The value of children to parents. In: Fawcett JT (ed). Psychological perspectives on population. New York: Basic Books, 19–76.

- Mynarska, M.; Rytel, J. (2018). From motives through desires to intentions: Investigating the reproductive choices of childless men and women in Poland. Journal of biosocial science, 50(3), 421-433. [CrossRef]

- Irani, M.; Khadivzadeh, T. (2018). The relationship between childbearing motivations with fertility preferences and actual child number in reproductive-age women in Mashhad, Iran. Journal of education and health promotion, 7, 175. [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. (2001). Nature and operation of attitudes. Annual review of psychology, 52(1), 27-58.

- Kuhnt, A. K. i Trappe, H. (2013). Easier said than done: Childbearing intentions and their realization in a short-term perspective. Rostock: Max Planck Institute for Demographic Research (MPIDR working paper WP-2013-018), 225-245. [CrossRef]

- Freitas R i Testa, M.R. (2017). Fertility desires, intentions and behaviour: A comparative analysis of their consistency (No. 04/2017). Vienna Institute of Demography Working Papers. [CrossRef]

- Morgan, S. P. i Bachrach, C. A. (2011). Is the Theory of Planned Behaviour an appropriate model for human fertility? Vienna yearbook of population research, 9, 11-18. http://www.jstor. 4134. [Google Scholar]

- Ainsworth, M. D. (1969). Object Relations, Dependency, and Attachment: A Theoretical Review of the Infant-Mother Relationship. Child Development, 40(4), 969–1025.

- Umemura, Y.; Koike, N.; Ohashi, M.; Tsuchiya, Y.; Meng, Q.J.; Minami, Y.; Hara, M.; Hisatomi, M.; Yagita, K. (2017). Involvement of posttranscriptional regulation of Clock in the emergence of circadian clock oscillation during mouse development. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 114(36), E7479–E7488. [CrossRef]

- Conroy-Beam, D.; Goetz, C.D.; Buss, D.M. (2015). Why do humans form long-term mateships? An evolutionary game-theoretic model. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 51, 1–39. [CrossRef]

- Nascimento, B.S.; Little, A.C.; Monteiro, R.P.; Hanel PH, P.; Vione, K.C. (2022). Attachment styles and mate-retention: Exploring the mediating role of relationship satisfaction. Evolutionary Behavioral Sciences, 16(4), 362–370. [CrossRef]

- Međedović, *!!! REPLACE !!!*; J, *!!! REPLACE !!!*; Anđelković, *!!! REPLACE !!!*; A i, L.u.k.i. Međedović; J; Anđelković; A i, L.u.k.i.ć.; J. (2022). Fitness costs of insecure romantic attachment: The role of reproductive motivation and long-term mating. Evolutionary Psychology, 20(4). [CrossRef]

- Cheng, G.; Zhang, D.; Sun, Y.; Jia, Y.; Ta, N. (2015). Childless adults with higher secure attachment state have stronger parenting motivation. Personality and Individual Differences, 87, 39-44. [CrossRef]

- Salovey, P.; Mayer, J.D. (1990). Emotional Intelligence. Imagination, Cognition, and Personality, 9, 185-211.

- Mayer, J.D.; Salovey, P. (1997). What is emotional intelligence? In P. Salovey & D. J. Sluyter (Eds.), Emotional development and emotional intelligence: Educational implications (pp. 3–34). Basic Books.

- Hajncl, L. Vučenović; D; Hajncl, L. (2018). Efekti dobi na međusobni odnos verbalnih i neverbalnih sposobnosti te emocionalne inteligencije. Suvremena psihologija, 21(2), 121-139. [CrossRef]

- Bloch, L.; Haase, C.M.; Levenson, R.W. (2014). Emotion regulation predicts marital satisfaction: More than a wives’ tale. Emotion, 14(1), 130. [CrossRef]

- Malouff, J.M.; Schutte, N.S.; Thorsteinsson, E.B. (2014). Trait Emotional Intelligence and Romantic Relationship Satisfaction: A Meta-Analysis. The American Journal of Family Therapy, 42, 53 - 66. [CrossRef]

- Mammadov, B.; Erenel, A.S. (2021). The Effect of Emotional Intelligence on Maternity Role. Medical Journal of Western Black Sea. [CrossRef]

- Apostolou, M.; Paphiti, C.; Neza, E.; Damianou, M.; Georgiadou, P. (2019). Mating performance: exploring emotional intelligence, the dark triad, jealousy and attachment effects. Journal of Relationships Research, 10. 10. [CrossRef]

- Kaur, J.; Junnarkar, M. (2017), Emotional Intelligence and Intimacy in Relationships, International Journal of Indian Psychology, 4(3).

- Collins, N. L. (1996). Working models of attachment: Implications for explanation, emotion, and behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 71(4), 810–832.

- Takšić, V. (2002). Questionnaires of emotional intelligence (competence). In: K. Lacković-Grgin, A. Bautović, V. Ćubela, Z. Penezić (Ed.), Collection of psychological scales and questionnaires, (pp. 27-45), Faculty of Philosophy, Zadar.

- Guedes, M.; Pereira, M.; Pires, R.; Carvalho, P.; Canavarro, M.C. (2015). Childbearing motivations scale: construction of a new measure and its preliminary psychometric properties. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 24, 180-194. [CrossRef]

- Sousa, V.D.; Rojjanasrirat, W. (2011). Translation, adaptation and validation of instruments or scales for use in cross-cultural health care research: a clear and user-friendly guideline. Journal of evaluation in clinical practice, 17(2), 268–274. [CrossRef]

- Fiskin G i Sari, E. (2021). Evaluation of the relationship between youth attitudes towards marriage and motivation for childbearing. Children and Youth Services Review, 121, 105856. [CrossRef]

- Van der Walt, C. (2019). The Relationships Between First-Year Students’ Sense of Purpose and Meaning in Life, Mental Health and Academic Performance. Journal of Student Affairs in Africa, 7, 2, 109-121. [CrossRef]

- N i, C.v.e.t.k.o.v.i. Rončević; N i, C.v.e.t.k.o.v.i.ć.; K. (2016). Students’ Attitudes and Behaviours in the Context of Environmental Issues. Socijalna ekologija, 25 (1-2), 11-37. [CrossRef]

- Sonfield, A.; Hasstedt, K.; Kavanaugh ML i Anderson, R. (2013). The Social and Economic Benefits of Women’s Ability to Determine Whether and When to Have Children. Guttmacher Institute.

- Duvander, A.-Z.; Fahlén, S.; Brandén, M.; Ohlsson-Wijk, S. (2019). Who makes the decision to have children? Couples’ childbearing intentions and actual childbearing. Advances in Life Course Research. 43. [CrossRef]

- Roberts, R.D.; MacCann, C.; Matthews, G.; Zeidner, M. (2010). Emotional intelligence: Toward a consensus of models and measures. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 4(10), 821–840. [CrossRef]

- McElwain, A.D.; Kerpelman JL i Pittman, J.F. (2015). The role of romantic attachment security and dating identity exploration in understanding adolescents’ sexual attitudes and cumulative sexual risk-taking. Journal of adolescence, 39, 70–81. [CrossRef]

- Pearce, L. D. i Davis, S. N. (2016). How early life religious exposure relates to the timing of first birth. Journal of Marriage and Family, 78(5). [CrossRef]

- Peri-Rotem, N. (2016). Religion and Fertility in Western Europe: Trends Across Cohorts in Britain, France and the Netherlands. European journal of population = Revue europeenne de demographie, 32(2), 231–265. [CrossRef]

- Lampic, C.; Svanberg, A.S.; Karlström P i Tydén, T. (2006). Fertility awareness, intentions concerning childbearing, and attitudes towards parenthood among female and male academics. Human reproduction, 21(2), 558-564. [CrossRef]

- https://dzs.gov. 1554.

- Maftei, A. Holman, A.C. i Marchiș, M. (2023). Choosing a life with no children. The role of sexism on the relationship between religiosity and the attitudes toward voluntary childlessness. Current Psychology. ( 42(14), 11486–11496. [CrossRef]

- https://www.hlk.hr/EasyEdit/UserFiles/priop%C4%87enja/2023/priopcenje-studija-hrvatskog-lijecnistva-pzz.pdf.

- Borg, A. (2018). Work-life balance: Public hearing: Work-life balance for parents and carers. Presentation at the European Parliament, Brussels.

- Wanous, J.P.; Reichers, A.E. (1996). Estimating the Reliability of a Single-Item Measure. Psychological Reports, 78(2), 631-634. [CrossRef]

- Spector, P. E. (1992). Summated rating scale construction. SAGE Publications, Inc. [CrossRef]

- Allen, M.S.; Iliescu, D.; Greiff, S. (2022). Single item measures in psychological science: A call to action [Editorial]. European Journal of Psychological Assessment, 38(1), 1–5. [CrossRef]

- Brenning, K.; Soenens B i Vansteenkiste, M. (2015). Whatâs your motivation to be pregnant? Relations between motives for parenthood and womens prenatal functioning. Journal of Family Psychology, 29(5), 755–765. [CrossRef]

- Morgan, S.P.; King, R.B. Why Have Children in the 21st Century? Biological Predisposition, Social Coercion, Rational Choice. European Journal of Population 17, 3–20 (2001). [CrossRef]

- Hank, K.; Wetzel, M. (2018). Same-sex relationship experiences and expectations regarding partnership and parenthood. Demographic Research. 39. 701-718. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).