1. Introduction

Making any decision has its consequences. In business, it is necessary to consider costs as well as benefits. In the simplest terms, benefits relate to the financial sphere, but they extend beyond this obvious sphere into environmental aspects of business and social responsibility. This means taking into account macroeconomic issues in microeconomic decisions and there is a plenty of factors that influence the background of such decisions. Circular economy (CE) as a part of the broader “Environmental-Social-Governance” approach (ESG) is an important component of today's economic reality, as reflected in government interest and regulatory requirements. It is interesting when, from the economic perspective of a single organization, such actions have benefits. The circular economy offers various benefits from an economic perspective, particularly in terms of competitive advantages and economic performance [

1,

2]. Some researchers indicate that implementing CE requires the introduction of legal regulations and subsidies at the macroeconomic level. They point out that businesses may prioritize economic benefits over environmental benefits, and thus, it is crucial to mobilize organizations from the top down to undertake sustainable development actions. However, the analysis of the main assumptions of the circular economy suggests a reversal of this claim. The main goal of CE is to develop management strategies for companies to separate revenue growth from the growth in the use of materials and primary resources as much as possible. Primarily, at the microeconomic level, CE aims to contribute to the development and increased competitiveness of enterprises while simultaneously protecting non-renewable resources. Various bottom-up actions within companies, considering process and product innovations, eco-design, and circular business models supported by top-down actions such as subsidies and financial incentives, can achieve effective and efficient changes in the economic system toward a circular economy. In addition to short-term economic benefits, companies are focusing on the possibility of achieving their long-term goals. Therefore, a strategic element to increase organizational resilience (OR) will be reducing dependence on critical resources as well as resources in general.

There is a bidirectional relationship between the actions of individual actors and environmental macroeconomics. On the one hand, the collection of activities of individual organizations affects the environment. On the other hand, as a result of the identification of the negative aggregate impact on the environment, legal requirements are created to force certain actions in the sphere of microeconomic activities. In the management process, every organization faces changes – evolutionary as well as revolutionary. At the core of the response to change is organizational resilience, most often defined as the ability to function during a shock and then return to normal function [

3]. The vast majority of OR definitions in the literature point to the role of organizational resilience in responding to an emergency event [

4,

5,

6,

7]. The concept of strengthening OR has received increasing attention over the years [

8] owing to the dynamic nature of the business landscape. The high dynamics of economic change have influenced the analysis of OR from an evolutionary (calm) and revolutionary (sudden) perspective [

9,

10,

11]. In a different light, there are two movements: one that consists of defending oneself to ensure continuity, and another that concerns the change necessary to bounce back [

12].

The theoretical and practical issue is to link the macroeconomic topic of circular strategy with microeconomic and practical activities in the organization. The purpose of the article is to evaluate selected organizational solutions in metal industry factory in the area of circular economy and their impact on strengthening organizational resilience.

2. Research Problem & Protocol

Companies with a higher circularity score have a significantly higher resilience score during crises and during normal times, compared to less circular companies and the size of the company does not matter during a crisis to adapt and react flexibly, while it is important when there is no crisis [

13]. The CE framework is rising as a feasible option to transit to a more resource-efficient system in which economic growth is decoupled from material and resource depletion and supply risk, and to achieve resilience at a company and system level [

14]. The circular economy is a systemic change whereby economic and business opportunities can be combined with environmental and social benefits and generate long-term resilience [

15,

16]. By overlooking resilience, circular economy research is currently in danger of advocating business practices that are ineffective at strengthening the ability of firms, industries, and social-ecological systems to manage shocks and disturbances. Moreover, business practices pursued in the name of circularity without consideration of resilience may even be harming the capacity of actors to ably adapt and transform [

14].

There are quite a few papers in the literature describing individual circular economy or organizational resilience aspects, but few that combine the two issues. Lopes de Sousa Jabbour et al. recommended that future studies should focus on identifying mediating factors that could enhance the relationship between CE and OR, as well as checking whether some control variables may affect this relationship [

17]. This reflects not only the research gap in the area of theoretical relationships between CE and OR but also the search for practical relationships, especially as a case study in a specific organization.

Therefore the problem concerns the interrelations between CE and OR in the level of management in an organization and effects of decisions in that area of business. The goal of the paper is to evaluate selected organizational solutions in metal industry factory in the area of circular economy and their impact on strengthening organizational resilience. The research path consists of two stages: a systematic literature review and a case study of a manufacturing company. Economic-environmental analysis of forge maintain (as a department/production cell/building/process) was done through the prism of circular economy and organizational resilience structure used as criteria of assessing.

A literature review article provides an overview of literature related to some subject and there are many methods and tools to achieve the planned goal [

18]. A systematic literature review (SLR) was adopted as the method of study, due to the thematically specific scope of the review and the relatively small number of articles, facilitating manual analysis of their content [

19]. For that study, Scopus database was selected, as the most inclusive database to identify relevant studies and conducted a simultaneous search focusing only on the Title to identify the most thematically relevant articles possible (indicated further, depending on the search area). According to the process delineated by the SLR method [

20], strict inclusion criteria were defined for the articles in that review (shown in

Table 1.). To be included in the study, the articles had to meet eight criteria: (1) include indicated words in the title, (2) published in the last five years between 01.01.2019-19.04.2024 (due to the increased prevalence of the subject in those years), (3) studies in English, (4) in a scientific journal, (5) indexed in Scopus, (6) open-access, (7) full-text article, (8) subject area limited to Business, Management and Accounting. In all, we identified 763 articles.

In the next step, we read the abstracts in searching for content to help achieve the stated research goal. We used the IMO framework (“inputs-mediators-outputs”) to identify relevant articles and practically rank the results. Using this framework can highlight multiple levels of inputs and mediators that influence outcomes of interest [

21]. As a result of this process, we selected 48 articles for in-depth analysis and read them as a whole.

The organizational resilience issue grew in importance as a result of the emergence of COVID-19, which disrupted the operations of many companies all around the world. Zapłata and Kwiatek indicated, after the literature review process, that between 2003–2022 were published 304 articles, however, 46% of all of them were published from 2020 [

22].

The interest of CE burned out between 2020 and 2021 mainly as an answer to the European Union activity (EU) in the field of waste management and CE. The CE transition nowadays is fostered by different groups of stakeholders including global organizations, science, the whole private sector, and even consumers. The circular economy is gaining attraction also because it is related strictly to the sustainability concept [

23]. The CE is present in all EU documents somehow related to sustainable development e.g., has been included in the EU Taxonomy, where one of the points that organizations have to make as part of the environmental impact reduction is the transition to a circular economy [

24]. The SLR limitation in the CE concept was set due to an enormous number of articles that relate to CE economy or strategy e.g., a Scopus query in late 2021 returned more than 13,000 documents containing the term “circular economy” [

25].

3. Circular Economy & Strategy

The circular economy is no longer the idea of resource management, but it is an inevitable path to sustainability. It will gradually displace the traditional model of a linear economy based on the extraction of raw materials [

26]. Currently, this concept has been well explored and comprehended by researchers worldwide. Over 200 definitions of the Circular Economy (CE) have emerged based on the same paradigm of closing material loops in the economy [

25]. Nobre & Tavares researched the understanding of the CE concept from the perspective of PhD specialist researchers [

27]. Based on this, they developed a CE definition encompassing all its essential elements. Primarily, CE is an economic system concerning the entire life cycle of materials circulating in the economy, from extraction to the final disposal stage by the consumer. It is pointed out that developing a CE model should occur in all three dimensions of sustainable development, namely environmental, economic, and social. However, it is noteworthy that the most crucial element of CE is rational resource management, focusing on environmental and economic aspects. One of the CE definitions presented by the Ellen MacArthur Foundation is “an industrial economy that is supportive or regenerative by expectation and framework” [

28]. This definition is also supported by three key principles: preserving resources, optimizing resources, and eliminating negative externalities [

28].

Circular strategy (CS) refers to the various approaches and methods that companies can employ to transition to a circular economy (CE) and improve sustainability. Circular strategies are essential for achieving global sustainable production and consumption goals by preserving the value of finite resources through the extension and renewal of products' lifecycles [

29]. A circular strategy may encompass action plans regarding resource utilization, eco-economy, eco-efficiency, sustainable projects, lean production, and product lifecycle management [

30]. The key components of a circular strategy include the integration of circular economy principles into product design, which opens strategic implications for organizations, such as new business models and re-arrangement of operations [

31]. The transition towards a circular economy requires new business models that challenge the linear logic of value creation, involving the rethinking of strategic decision-making processes and the development of new organizational capabilities [

32]. The implementation of CE-related actions provides competitive advantages for companies or entire supply chains, helping to alleviate cost and risk-related barriers. This implies that organizations can gain a competitive edge by adopting a circular economy-based strategy, which in turn can positively impact the financial performance of the company [

33]. A circular strategy also brings benefits to financial institutions, including greater loan diversification opportunities, increased lending to circular economy clients, and the promotion of responsible and sustainable banking [

34].

The implementation of a circular strategy in an organization should include integration with the corporate strategy and with the organization's business processes. CE implementation should not only take place at the management level but should start at the product or service design stage. This means that new business models (CBMs), operational reorganization, and significant use of digital infrastructure will be required [

35]. Furthermore, these actions need to be considered throughout the supply chain. CE supply network management is a complex system of relationships occurring in three configurations: closed loop, open loop, and hybrid loop [

36]. Successful implementation of CE in a company only takes place when the entire supply chain is taken into account.

Circular business models belong to a sub-category of sustainable business models [

37]. They are therefore based on elements of sustainable management e.g. Triple Bottom Line concept, sustainable supply chains, product lifecycle approach and long-term perspective [

38]. CBMs, however, have their specifications focusing primarily on the closed loops [

39]. Several main solutions can be distinguished in terms of CBMs [

39]:

reverse logistics which enables retention of value in product return flow,

cascading and multiple cycles of value creation,

adoption of circular strategies: cycling (preserving the material and energy within the system); extending the product life; intensifying the use of a given product; dematerialization of a product (services, digitalization),

networks of independent but interlinked stakeholders.

The most commonly used management model in the circular economy is the industrial symbiosis. Industrial symbiosis plays a crucial role in implementing a circular economy. It can be one of the circular management strategies to achieve a higher degree of circularity in the enterprise. Industrial symbiosis involves the collaborative management of resources among multiple companies, focusing on the reuse of secondary materials, such as industrial by-products [

40]. To develop circular strategies organizations can leverage strategic management methods, develop frameworks for circular business models, diagnose current business perspectives, build experimentation capability, and focus on circular design capacity and capability to develop circular strategies.

Increasingly, researchers are pointing to links between the implementation of lean management methods and the drive to increase levels of circularity within companies. Lean is mainly about reducing waste in the production process, which can indirectly influence the implementation of circularity strategies [

41]. However, there is still little empirical research related to the direct impact of lean on CE goals [

41]. In addition, some researchers take the lean, which contradicts the basic idea of CE that there is no waste in the economy, only raw materials [

42]. Boldrini and Antheaume claim that there are still few examples in the literature about methodology and empirical studies of adapting organizations’ BMs to a circular economy and operationalizing CE principles [

39]. They decided to present their methodology of the multi-actor, multi-level, circular, and collaborative business model framework [

39].

One of the CBMs that should also be developed is reverse logistics. It is based on the forward flow of materials. This means that the direction of the main flow is in the opposite direction, from many points to centralized locations. This CBM allows for more sustainable management of resources through the use of recycling processes, reduction of raw materials, and reuse. On the other hand, it is a very complex system that involves a high degree of uncertainty and difficult decisions that affect supply chain performance. In reverse logistics, products travel often in smaller quantities, at a less predictable pace, and with manual tracking systems [

43]. Reverse logistics fits into the circular economy by closing the product life cycle starting from the beginning of the design process to the end of the production process [

44]. Effective reverse logistics can also help to reuse, recycle and dispose of waste [

45]. The life-cycle design stage of a product is also an important part of CE implementation. How a product is designed will largely result from the business model adopted by the organization. Decisions taken in the design process influence the future circularity performance of the product [

46]. Whether this model will be oriented towards recycling or perhaps refurbishment and reuse or repair.

Implementing circular strategies in companies requires developing thoughtful strategic decision-making processes and developing new organizational capabilities, and to engage multiple organizational functions, collaborating with multiple stakeholders, and consider specific contextual aspects of the business [

47].

4. Organizational Resilience

Resilience is one of those words that everyone associates, but the problem is with concretizing it. In general, resilience means the capacity to withstand or to recover quickly from difficulties, which relates to various aspects of existence. In this context, it is possible to point to ecology, safety and reliability, engineering, positive psychology, and organizational development, thus different disciplines have influenced the understanding and application of the organizational resilience concept [

4]. Organizational resilience is most often defined as the ability to function during a shock and then return to normal function [

3]. The concept of strengthening organizational resilience has received increasing attention over the years [

8] owing to the dynamic nature of the business landscape. In a normative way, organizational resilience is defined as the “ability of an organization to absorb and adapt in a changing environment” [

48]. The issue of adaptation can apply to the macro scale like the geopolitical crisis of war in Ukraine [

49], worldwide pandemic Covid-19 [

6,

50], cultural differences among countries [

51] as well as micro scales regarding industries: pharmaceutical [

52], banking [

53], and automotive [

54]. Macro and microeconomic factors have an impact on the performance of individual organizations, and conversely, the activities of individual entities affect global achievements.

Every organization operates in an environment that affects its functioning and also its resilience. On the one hand, creating the conditions for its creation, on the other hand, providing a source of threats that can trigger the need to mobilize this resilience in normal and emergencies. Strengthening organizational resilience in normal times (BAU – business as usual) is related to taking preventive activities. In contrast, in a crisis, organizational resilience is the basis for making decisions and taking actions to minimize losses, acting in a crisis aimed at returning to normality. Therefore, both active and passive resilience are important in day-to-day operations as well for longevity [

55]. Organizational resilience is characterized by its dynamic approach and indicated four categories [

56]:

resilience as a proactive attribute, before (t-1) an event,

resilience as absorptive and adaptive attributes, during (t) an event,

resilience as a reactive attribute, after (t + 1) an event,

resilience as a dynamic attribute, before during, and after an event.

At the root of all action are people, thus human resources are very influential on organizational resilience [

57]. Management strategy in that organizational area in combination with leadership and commitment are key factors for building organizational resilience [

58]. The importance of connecting organizational learning strategies to organizational resilience [

59] cannot be overestimated because the positive effect of this combination is noticeable [

60,

61,

62]. Human resource management in connection with knowledge management is the most important factor of organizational resilience, which was noticed by a literature review of 304 articles concerning organizational resilience [

22].

From a practical point of view, the actions taken in a single organization to strengthen organizational resilience are the most important and useful. Hillmann & Guenther indicated: time of recovery, survival, stability (severity of loss), flexibility (time for recovery), avoidance, and resource access and created a conceptual model of OR with four elements: resilient behavior, resilience resources, resilience capabilities and that three factors influence resilient response [

63]. Eleven categories as a holistic framework of OR were proposed [

64]: 1) collaboration; 2) planning; 3) procedures; 4) training; 5) infrastructure; 6) communication; 7) governance; 8) learning lessons; 9) situation understanding (awareness); 10) resources; 11) evaluation. Because of many interactions organizational resilience is not a static term [

65], therefore Wiig & Fahlbruch pointed out three broad “moments” of resilience: 1) Situated resilience (activities focus on detecting, adjusting to, and recovering from disruptive events); 2) Structural resilience (connected with monitoring of operational activities and involves the purposeful redesign and restructuring of resources to adapt to or accommodate disruptive events); 3) Systemic resilience (strategic configuration of system) [

66]. Other authors [

67] analyzed the influencing factors of organizational resilience and listed twenty factors influencing organizational resilience: 1) organizational resources; 2) organizational competencies; 3) organizational relationship; 4) organizational communication; 5) social capital; 6) organizational strategy; 7) organizational learning; 8) work passion; 9) business model; 10) organizational leadership; 11) organizational trust; 12) threat perception; 13) cognitive competence; 14) emotional competence; 15) organizational efficiency; 16) organizational culture; 17) organizational commitment; 18) organizational change; 19) social responsibility; 20) organizational structure. Four key factors in achieving resilience: (a) collective sense-making, (b) team decision-making, (c) harmonizing work-as-imagined (WAI) and work-as-done (WAD), and (d) interaction and coordination [

68].

5. Circular Resilience – Research Framework

Organizational resilience can be analyzed from two points of view, depending on the form of activation of actions in response to the initiating factor: reactive and preventive. Taking action at the onset of a crisis means a reactive (emergency) operational approach [

69]. Taking preventive action (e.g., by addressing just sustain issues) means a calm, strategic approach [

70] to strengthening organizational resilience.

The term “circular strategy” (CS) has not been clearly defined in the literature. However, it can be inferred that circular strategy can refer to specific plans, policies, and measures formulated to implement the principles of a CE [

71]. The phrase “circular economy” relates rather to the broader concept of replacing the linear economy and all that it entailed with a closed-loop approach in macroeconomic terms. Whereas “circular strategy” refers more to the implementation of CE principles in organizations, the development of circular business models, and thus a microeconomic approach. CE refers to the overarching system and principles of reuse and maximization of resource use, while CS can include specific activities and plans designed to achieve circular economy goals.

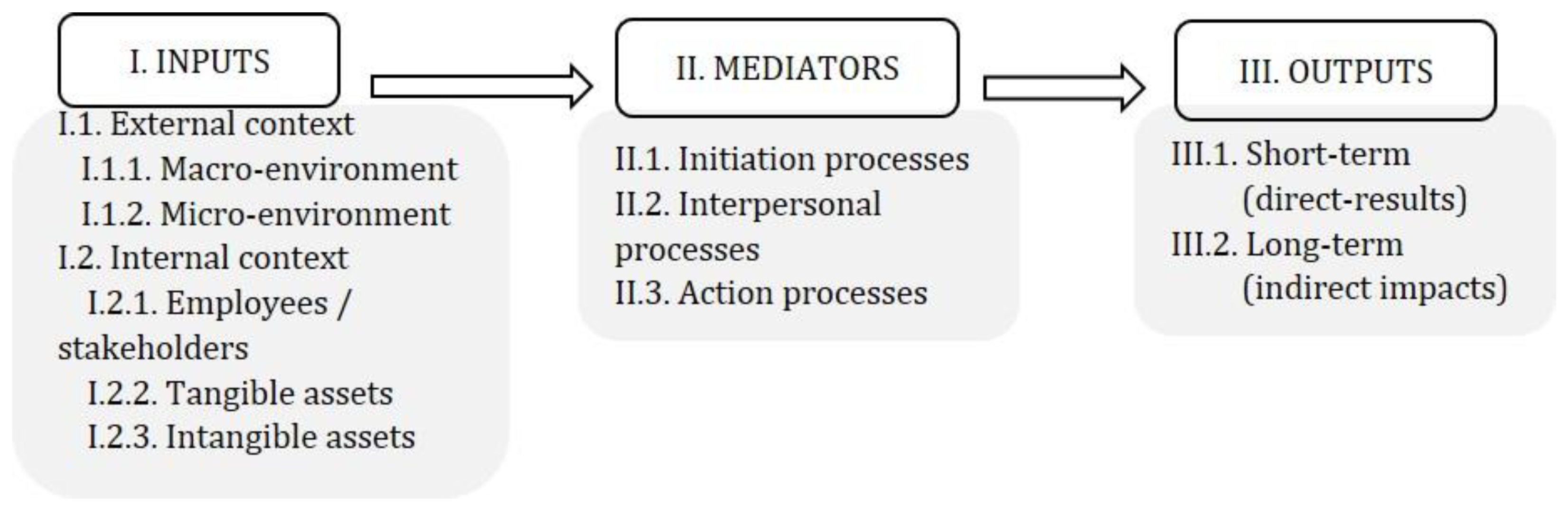

During the literature review, we analyzed abstracts of articles through the prism of the IMO model (“inputs-mediators-outputs”), to identify elements that suit that model in an aim to approach knowledge practically. “Inputs” are everything that constitutes the base of decision-making regarding organizational activities. As a result of completing tasks, results are achieved (“outputs”). Between inputs and outputs are “mediators”, relations (processes) that link the causes with effects, interactions (processes), or transient products of interactions (emergent states) that translate inputs into ‘outputs’ [

72].

Organizational resilience seems to be a fuzzy concept due to its multifaceted nature and diversity in different organizations. The conceptualizations of OR address local matters and guide actions to strengthen resilience but are difficult to capture (like knowledge, skills, and level of preparedness) but are crucial aspects of resilience [

73]. It is impossible to create a universal checklist for determining the level of organizational resilience because many elements built “the ability to function” – a case-by-case issue for each organization. The IMO framework structure for identifying these issues is indicated in

Figure 1.

Inputs are the elements underlying resilience-enhancing activities, e.g., in the macro context are legal requirements, and from the micro context are market issues in the industry. Internal context refers to requirements and expectations from stakeholders and actions taken by employees in interaction with assets. Mediators, are activities that transform inputs into results, and are carriers of employee activities using inputs. Initiating processes are concerned with planning goals and tasks, the assignment of which belongs to interpersonal processes, in addition to training issues and also motivation. Action processes are real activities aimed at achieving planned goals. Effects in the area of OR are its strengthening, which can be considered in the short term and the long term. The first effects are direct, e.g. training employees to take action in the event of a power failure in the company, which relates to the preventive area. The long-term results are related to the possibility of real use of practiced situations – that is, the reactionary sphere, verification in real crisis conditions.

The individual element of the model can be reinforced by various factors both inside and outside the organization due to its uniqueness, which is related, among other things, to the scale of operations, the location of implementation, and the profile of activities. The topic of sustainability, which covers issues relating to CE, is one of the contributions in the field of macroeconomics. As a result, the analysis focuses solely on the problem of CE, as well as on the transition from macroeconomic assumptions to microeconomic activities and their consequences. Due to the long-term measures taken, primarily to safeguard the company's raw materials, and in the course of conducting business on the market, engaging in the CE activity is part of the preventive strengthening of the OR. The authors suggest combining these two approaches to gain insight into the interaction of concepts and decision-making processes in this management domain.

Table 2 presents the results of the study from the literature review. Nevertheless, it is not possible to categorize specific categories of inputs with both direct and indirect outputs. This is because numerous outputs can have many causes that are different factors or components of the inputs. Thus, by reversing the layout of

Table 2, a reversed table of the literature review was created in the form of an IMO model showing CE elements that strengthen the organization's resilience, taking into account these factors.

Implementing the CE strategy in enterprises can have both a short-term and long-term impact on increasing an organization's resilience. The short-term benefits of circular resilience include, above all, reducing operating costs [

35], increasing production efficiency [

86], improving the brand image [

32], enhancing compliance with environmental regulations [

24], and accessing new forms of funding [

34]. Long-term benefits include increased resilience to regulatory, economic, and climate change changes [

14]; innovation development [

87]; building long-term relationships with customers and suppliers [

80]; and reducing waste disposal risks [

44]. Undoubtedly, regulatory changes at the macro level, along with a shift in consumer awareness and the need to adapt to new market trends, serve as the most significant triggers for the implementation of the CE strategy in organizations. Individual "mediators" support the implementation of the above requirements in the company's strategy, with particular attention to interpersonal processes such as open communication between management and employees, conflict management skills, training program implementation, good leadership [

62], knowledge exchange [

10], and fostering a culture of openness, innovation, and cooperation. Companies can also use several management solutions, such as lean management and ecodesign [

41], supply chain management, or standardized management systems [

79].

6. The Metal Industry Factory – Case-Study’s Results

The organization described in the case study is a worldwide company, operating in the metal industry. The company has delivered to customers ready solutions for many different industries such as automotive, wind, industrial, food, and beverage. The company was established at the beginning of the 20th century and has operated in over 100 countries employing more than 40,000 people. In Poland, the company has its important production plant in this part of Europe, located in Greater Poland. The manufacturing unit in Poznan has had a long history that started in the 1960s. The government-owned company was equipped with all the operations needed not only to manufacture final products but also to manufacture and regenerate tolling etc., not to mention the social and medical facilities for its employees. With the privatization of the company, at the beginning of the ’90s, some operations and activities started to be outsourced (not product manufacturing-related processes) and recently there has been a focus on product production, not on the supporting processes.

The manufacturing process starts with the forging and turning processes that are followed then by the grinding and assembly process. However, depending on the customers, the factory serves them with final products (ready to be used in certain applications – external customers) and components, that are sold to other factories of the company (understood as internal customers), subjected to further processes.

From the company’s global perspective, due to worldwide expansion to emerging markets, the structure of income but also external capacities opening, the company has changed its strategy to manufacturing. As a result, the company started to disinvest its non-strategic or capital-intensive assets. One of the manufacturing areas affected strongly by disinvestment is related to forging activities. Changing company strategy has had a direct influence on the manufacturing plant in Poland. In addition to the global strategy shift, there has been also market uncertainty regarding the delivery of raw materials (steel) and related costs of materials, high energy prices, and the goal of being carbon neutral. Considering those factors as well as additional internal factors (such as working conditions, and local branding) the company’s management started to discuss the future of the local forging process. Thus, the case study is based on the forging department, which the company has been analyzing in terms of its closure or development that would require heavy investments.

The forging process has been performed from the beginning of the manufacturing plant establishment, in a dedicated and separate large building of the factory. The process has operated on three (depending on the product range) forging presses, operating at 45% efficiency. Within the last years, the presses have been upgraded to fulfill the minimum safety requirements and achieve CE marking (according to the regulations). Nevertheless, the presses have required regular maintenance due to their condition not mentioning about heading many breakdowns. The condition mentioned, of course, has also influenced the quality level of parts manufactured on the presses. Even if the scrap level, calculated at 2%, has been at an acceptable level, the rework level, calculated at 8%, has been considered very high. It means that the following production steps must put additional effort into making the parts according to the specifications. The forging process, due to its nature, has been also the most significant, for the factory, from the energy usage perspective. On top of that it is important to mention that the building for the forging process, constructed in 60’s, has not been renovated for years and has required heavy investments. On top of that company’s management has thought that it is necessary to adjust the building to current needs both from employees, branding as well as health, safety, energy, and environmental perspectives.

The decision-making process about the future of the forging department has taken a long time for the management however recent events like the war in Ukraine have just caused higher priority for creating the conclusion. Steel, as a raw material, purchased mainly from Russia, no longer has been on the agenda for the company, not only for the plant in Poland but for all other factories of the company. New sources of steel from China or Europe started to cause logistics issues (China) and cost implications (Europe).

Within the decision-making process, the company’s management decided to follow the IMO model according to

Table 3.

The multidimensional analysis included seven categories of inputs and six categories of mediators – criteria for the analysis. Each of the mediators has its weight, as decided by the organization’s management, depending on the mediator’s importance. The weights were needed at the time of the multidimensional analysis summary and designing the final decision regarding strategy for the forging department.

Each mediator has been evaluated in terms of impact presence (score 1) or lack of impact (0). The main question asked was whether full investment, partial investment, or closure has an impact on finance, suppliers, HR, EHS, and quality divided into internal and supplier quality as well as the OTD and facility management.

Once the inputs and mediators have been defined detailed analysis has been performed. Presence of impact or lack of impact was multiplied by the weight and a sum was calculated in each of the three scenarios. Detailed analysis has been presented in

Table 4.

Discussing the results of the analysis the highest sum (0.775) has been assigned to the closure of the forging production area. It means that this is the most desired result of the strategy for the forging area. From the financial point of view, the closure of the forging shop is economically the best solution considering the investment needed (building, process, CO2 decarbonization, etc.) and lower costs of the components on the external market. From the suppliers’ perspective, there is also an important impact as the company would increase the purchasing volumes at them so the negotiation position would also be better. On top of that, the company will not need to take care of the raw materials that have recently been issued. Of course, the company needs to take care of suppliers’ management but it does not seem, for the company, to be an issue.

The decision to invest (fully or partially) would impact the HR processes as the forging process can be perceived as a tough process and would require changes to the expectations of employees and to attract newcomers. Closure of the forging area would not have an impact in a longer perspective in terms of personal processes. The group dismissal process would require to proceed but this is a one-time activity. Looking at other HR aspects, the closure of forging does not influence it as there will be no recruitment and employee retention processes involved.

As forging is a high energy-demanding process, the closure of this production department will have an important influence on the manufacturing unit energy usage and the same situation is with the waste generation. On top of that such decision will impact positively the organization’s achievement of CO2 neutrality. From the quality point of view, outsourcing forging production will play an important role in the external quality area. Supplier quality management processes will need to be at a higher level, allowing solving quality issues immediately to continue production at the factory. Suppliers’ on-time delivery results will be important for assuring the production schedule according to a plan. There will be much less possibility to change the schedule once not all the production steps will be under the company’s dependence. From the facility management point of view closure of the forging shop has no impact as no modernization activities will be in place. There will need to be a decision on how to proceed with the building itself, but it is a result of the closure rather than a factor influencing the decision.

Changes that are happening in the business environment have influenced the organization (as a capital group) from many angles. Strengthening business results (e.g. new markets, higher margin) together with societal and environmental expectations made the company rethink the operating model. Reshaping this operating model has had a direct impact on the Polish Factory with its rich legacy. The impact has been mainly associated with the low-efficient and high-energy production process, which is the forging process. Unexpectedly the war in Ukraine caused issues with the availability of materials and delays in the deliveries. On top of that the price of materials increased heavily. The organization, having contingency plans, has been able to recover quickly from difficulties and continue its production. The production was continued however at much higher costs, that not always have been covered by customers through higher product prices. All those circumstances caused the organization to finally decide (as some attempts at the decision were taken in the past) how to move forward to achieve long-term results and be more resilient and agile in the changing World. The organization decided to use the IMO model for the decision-making process regarding the future of the forging production area. Many aspects were considered in this model and as a result, the forging shop will be closed. CE strategy in the organization will firstly allow to mitigate the risk through buying components for its production (not as raw material) from different regions, such as Europe, China, USA. Secondly, increasing the purchasing power of suppliers will positively impact the organization in the scope of negotiation processes, quality, and service received. Resources, that would be needed for investment into a forging shop, might be used differently, supporting the development of other organization areas. The investments can be more effective for the desired company’s production processes, which are assembly processes (e.g. automatization, robotization). In a long-term perspective organization will be more energy efficient and will operate with no usage of fossil fuels. This has been one of the most important environmental declarations from the company’s top management. It has been expected that such a strategy, towards decarbonization, will not only support the environment as such but also will open a new business opportunity. We can expect that more and more companies and people will start buying components and products from the suppliers taking care of the environment (in the scope of being CO2-free).

7. Conclusions, Limitation and Future Research

The issue of circular resilience in organization includes several aspects that emphasize the complexity and novelty of the approach while pointing out its limitations and potential further directions of research. The article presents various CE strategies while using the IMO model to identify aspects of the circular economy at the micro and macro levels that have a positive impact on the resilience of the organization. One of the biggest problems with implementing circular strategies is the complexity and opacity of requirements and guidelines, which in turn affects the lack of detailed understanding by managers of the impact of circular strategies on organizational resilience in the microeconomic context. Lopes de Sousa Jabbour et al. analyzed and conceptualized the impact of circular business models on operational decision-making in various areas of the entire product life cycle [

17]. It indicates that the resilience of an organization is primarily influenced by the adoption of an appropriate CE business model based primarily on 4.0 technologies and the integration of stakeholders in the supply chain [

17]. This allows you to take advantage of opportunities and sense market threats and properly prepare resources to achieve resilience through business circularity. Also, Borms et al. emphasized that companies with a higher degree of circularity show greater resilience both during crises and under normal operating conditions [

13]. Kennedy and Linnenluecke, on the other hand, argued that CE research sometimes ignores aspects related to resilience, which can lead to the promotion of business practices that do not strengthen companies' ability to cope with disruption, which in turn can lead to problems with adaptability [

14]. When analyzing empirical data, it should also be emphasized after Bressanelli et al. that CE can also be a catalyst for both product and process innovation, which in turn can also strengthen the resilience of the organization [

85]. Results indicate that corporate sustainability, organizational resilience, and corporate purpose merge to achieve long-term corporate survival [

88].

The literature review in this article allows, based on the IMO model used, to identify the key factors influencing the implementation of circular strategies in industry. On the other hand, focusing on the external and internal context of the organization made it possible to understand the dynamics between these factors and the company's activities in the context of CE. The results of the study only confirm the claim of Diaz and Baumgartner and Alonso-Almeida et al., who consider it crucial to have European policies and global regulations in promoting circular practices [

26,

35].

This article also provides important empirical data that allows for a deeper understanding of how theory can be effectively transformed into business practices. The results of the study show that the metal industry, which is a highly resource- and energy-intensive sector, can also apply specific circular strategies that not only have a positive impact on the efficiency of resource management but above all increase resilience to market and environmental changes at the microeconomic level.

The closure of the forging shop was preceded by a multifaceted analysis. The analysis was part of the evolutionary management in the metal parts manufacturing unit, in a preventive and long-term manner. It was therefore a measure to strengthen organizational resilience from a short- and long-term perspective. From one side organization has had already some level of resilience to be able to recover quickly from the start of the war in Ukraine, which was a major event in recent years (delivery and costs of steel as raw material to the organization’s forging process). On the other hand, it caused the organization to make a final decision regarding the future of the challenging (from different perspectives, mentioned before) process. The activities decided by the organization’s management (as IMO model outputs) will only strengthen the resilience and bring some new business opportunities soon. Nevertheless, the organization needs to focus now more on the proper management of a chain of suppliers, as will be more dependent on them going forward. This is the area that shall be considered from the resilience point of view.

That study is not without limitations, calling for future research. The limitation of the study was the analysis of the practice of only one company, which on the other hand allows for a deeper understanding of the specifics and challenges related to the implementation of such strategies in the industrial reality, of the metal industry. Future research should focus on a deeper recognition of intermediaries that could strengthen the link between the circular economy and organizational resilience. In addition, there is a need for further research on the practical application of circular strategies in different industrial contexts and their impact on different aspects of companies' operations, which can include both micro and macroeconomic perspectives.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.Z.; methodology, S.Z., M.M., and P.F.; software, S.Z., M.M., and P.F.; validation, S.Z., M.M., and P.F.; formal analysis, S.Z.; investigation, M.M. and P.F.; resources, P.F.; data curation, P.F.; writing—original draft preparation, S.Z., M.M., P.F., and J.K.B.; writing—review and editing, J.K.B., and K.S.; visualization, S.Z., M.M., P.F., J.K.B., and K.S.; supervision, S.Z., M.M., and J.K.B.; project administration, J.K.B.; funding acquisition, J.K.B., and K.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding, and the APC was funded by University of Warmia and Mazury in Olsztyn (project No. 22.610.100-110).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original data presented in the study are openly available in references [21, 72]. Due to legal and proprietary restrictions, data taken from metal industry company are not publicly available. The data presented in this study are available on request from the Patryk Feliczek (patryk.feliczek@ue.poznan.pl)

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Aspelund, A.; Olsen, M.F.; Michelsen, O. Simultaneous adoption of circular innovations: A challenge for rapid growth of the circular economy. In Research Handbook of Innovation for a Circular Economy; 2021; pp. 160–173.

- Nowicki, P.; Ćwiklicki, M.; Kafel, P.; Niezgoda, J.; Wojnarowska, M. The circular economy and its benefits for pro-environmental companies. Bus. Strateg. Environ. 2023, 32, 4584–4599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruickshank, N. He who defends everything, defends nothing: proactivity in organizational resilience. Transnatl. Corp. Rev. 2020, 12, 94–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillmann, J. Disciplines of organizational resilience: contributions, critiques, and future research avenues; Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 2020; ISBN 0123456789.

- Rannane, Y.; Mharzi, H.; El Oualidi, M.A. A systematic review of the supply chain resilience measurement literature. 2022 IEEE 14th Int. Conf. Logist. Supply Chain Manag. LOGISTIQUA 2022 2022, 1–6. [CrossRef]

- Paeffgen, T.; Lehmann, T.; Feseker, M. Comeback or evolution? Examining organizational resilience literature in pre and during COVID-19. Contin. Resil. Rev. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ketelaars, E.; Gaudin, C.; Flandin, S.; Poizat, G. Resilience training for critical situation management. An umbrella and a systematic literature review. Saf. Sci. 2024, 170, 106311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baghersad, M.; Zobel, C.W. Organizational Resilience to Disruption Risks: Developing Metrics and Testing Effectiveness of Operational Strategies. Risk Anal. 2021, 0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawson, P.M. Change Management. In The Blackwell Encyclopedia of Sociology; Ritzer, G., Ed.; Blackwell Publishing Ltd, 2006; pp. 427–431 ISBN 9781405124331.

- Herbane, B. Rethinking organizational resilience and strategic renewal in SMEs. Entrep. Reg. Dev. 2019, 31, 476–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, T.; Edgeman, R.; AlNajem, M.N. Exploring the Intellectual Structure of Research in Organizational Resilience through a Bibliometric Approach. Sustain. 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokline, B.; Anis, M.; Abdallah, B. Organizational resilience as response to a crisis : case of COVID-19 crisis. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borms, L.; Brusselaers, J.; Vrancken, K.C.; Deckmyn, S.; Marynissen, P. Toward resilient organizations after COVID-19: An analysis of circular and less circular companies. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2023, 188, 106681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, S.; Linnenluecke, M.K. Circular economy and resilience: A research agenda. Bus. Strateg. Environ. 2022, 31, 2754–2765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellen, M.; Company, M. & Towards the Circular Economy : Accelerating the scale-up across global supply chains; 2014; ISBN 8788757587.

- Di Stefano, C.; Elia, S.; Garrone, P.; Piscitello, L. The Circular Economy as a New Production Paradigm to Enhance Resilience of MNEs and the Economic System. AIB Insights 2023, 23, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes de Sousa Jabbour, A.B.; Latan, H.; Chiappetta Jabbour, C.J.; Seles, B.M.R.P. Does applying a circular business model lead to organizational resilience? Mediating effects of industry 4.0 and customers integration. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2023, 194, 122672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, J.; Rialp, A. The art of writing literature review : What do we know and what do we need to know ? 2020, 29.

- Donthu, N.; Kumar, S.; Mukherjee, D.; Pandey, N.; Lim, W.M. How to conduct a bibliometric analysis: An overview and guidelines. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 133, 285–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kushwah, S.; Dhir, A.; Sagar, M.; Gupta, B. Determinants of organic food consumption. A systematic literature review on motives and barriers. Appetite 2019, 143, 104402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paul, J.; Khatri, P.; Kaur Duggal, H. Frameworks for developing impactful systematic literature reviews and theory building: What, Why and How? J. Decis. Syst. 2023, 00, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zapłata, S.; Kwiatek, P. Organizational Resilience - THEMATIC GROUPS IN THE LITERATURE. In: Contemporary challenges of science and business in a turbulent environment; 2023; pp. 221–238 ISBN 9781713848370 (in Polish).

- Geisendorf, S.; Pietrulla, F. The circular economy and circular economic concepts-a literature analysis and redefinition. Thunderbird Int. Bus. Rev. 2017, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission EU Taxonomy Climate Delegated Act; 2021.

- Kirchherr, J.; Yang, N.-H.; Schulze-Spüntrup, F.; Heerink, M.; Hartley, K. Conceptualizing the Circular Economy (Revisited): An Analysis of 221 Definitions. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2023, 194, 107001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso-Almeida, M. del M.; Rodríguez-Antón, J.M.; Bagur-Femenías, L.; Perramon, J. Sustainable development and circular economy: The role of institutional promotion on circular consumption and market competitiveness from a multistakeholder engagement approach. Bus. Strateg. Environ. 2020, 29, 2803–2814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nobre, G.; Tavares, E. The quest for a circular economy final definition: A scientific perspective. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 314, 127973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellen MacArthur Foundation Towards the Circular Economy. Vol 1. Economic and business rationale for an accelerated transition.; 2013.

- Blomsma, F.; Pieroni, M.; Kravchenko, M.; Pigosso, D.C.A.; Hildenbrand, J.; Kristinsdottir, A.R.; Kristoffersen, E.; Shabazi, S.; Nielsen, K.D.; Jönbrink, A.-K.; et al. Developing a circular strategies framework for manufacturing companies to support circular economy-oriented innovation. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, A. Circular Economy. In Management for Professionals; 2022; Vol. Part F527, pp. 375–399.

- Alamerew, Y.A.; Brissaud, D. Modelling reverse supply chain through system dynamics for realizing the transition towards the circular economy: A case study on electric vehicle batteries. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benfer, M.; Gartner, P.; Klenk, F.; Wallner, C.; Jaspers, M.-C.; Peukert, S.; Lanza, G. A Circular Economy Strategy Selection Approach: Component-based Strategy Assignment Using the Example of Electric Motors. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the Conference on Production Systems and Logistics; 2022; pp. 22–31.

- McDougall, N.; Wagner, B.; MacBryde, J. Competitive benefits & incentivisation at internal, supply chain & societal level circular operations in UK agri-food SMEs. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 144, 1149–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozili, P.K. Circular Economy, Banks, and Other Financial Institutions: What’s in It for Them? Circ. Econ. Sustain. 2021, 1, 787–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaz, A.; Baumgartner, R.J. A managerial approach to product planning for a circular economy: Strategy implementation and evaluation support. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braz, A.C.; Marotti de Mello, A. Circular economy supply network management: A complex adaptive system. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2022, 243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geissdoerfer, M.; Morioka, S.N.; de Carvalho, M.M.; Evans, S. Business models and supply chains for the circular economy. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 190, 712–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geissdoerfer, M.; Pieroni, M.P.P.; Pigosso, D.C.A.; Soufani, K. Circular business models: A review. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 277, 123741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boldrini, J.-C.; Antheaume, N. Designing and testing a new sustainable business model tool for multi-actor, multi-level, circular, and collaborative contexts. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashton, W.S.; Chertow, M.R.; Althaf, S. Industrial symbiosis: Novel supply networks for the circular economy. In Circular Economy Supply Chains: From Chains to Systems; 2022; pp. 29–48.

- Reke, E.; Sørumsbrenden, J.; Hareide, E.; Halfdanarson, J.; Iakymenko, N.; Powell, D. A Lean Framework for Developing Circular Business Models. In Proceedings of the Lecture Notes in Mechanical Engineering; 2024; pp. 259–266.

- Reke, E.; Iakymenko, N.; Kjersem, K.; Powell, D. Lean & Green: Aligning Circular Economy and Kaizen Through Hoshin Kanri. In Proceedings of the IFIP Advances in Information and Communication Technology; 2022; Vol. 664 IFIP, pp. 399–406.

- Alarcón, F.; Cortés-Pellicer, P.; Pérez-Perales, D.; Mengual-Recuerda, A. A Reference Model of Reverse Logistics Process for Improving Sustainability in the Supply Chain. Sustainability 2021, 13.

- Butt, A.S.; Ali, I.; Govindan, K. The role of reverse logistics in a circular economy for achieving sustainable development goals: a multiple case study of retail firms. Prod. Plan. Control 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.C.; Sepasgozar, S.M.E.; Wang, M.; Sun, J.; Ning, X. Green performance evaluation system for energy-efficiency-based planning for construction site layout. Energies. 2019, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saidani, M.; Kim, H. Design for product circularity: Circular economy indicators with tools mapped along the engineering design process. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the ASME Design Engineering Technical Conference; 2021; Vol. 5.

- Sousa-Zomer, T.T.; Magalhães, L.; Zancul, E.; Cauchick-Miguel, P.A. Exploring the challenges for circular business implementation in manufacturing companies: An empirical investigation of a pay-per-use service provider. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2018, 135, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Organization for Standardization ISO 22316; Geneva, 2017.

- Avioutskii, V.; Roth, F. Doing business in Russia: normative organizational resilience, organizational identity and exit decisions. Manag. Decis. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahari, A.I.; Abdul Manan, D.I.; Mohamed, N.; Said, J. Impact of Dynamic Leadership and Marketing Planning on Organizational Resilience During Covid-19: Higher Learning Institutions. SAGE Open 2023, 13, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fietz, B.; Hillmann, J.; Guenther, E. Cultural Effects on Organizational Resilience : Evidence from the NAFTA Region. Schmalenbach J. Bus. Res. 2021, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerdpitak, C.; Kerdpitak, N.; Heuer, K.; Li, L. Factors affecting of business continuity planning on sustainability performance for Thailand’s pharmaceutical industry. Int. J. Learn. Divers. Identities 2023, 30. [Google Scholar]

- Juliana, B.M.; Prabowo, H.; Alamsjah, F.; Hamsal, M. Building Organizational Resilience by developing Customers Orientation, Digital Adoption and Organizational Agility: An Empirical Study in The Indonesian Banking Industry. Qual. - Access to Success 2023, 24, 75–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamauchi, N.; Sato, H. The relationship between top management team diversity and organizational resilience: Evidence from the automotive industry in Japan. J. Gen. Manag. 2023, 48, 184–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burnard, K.J.; Bhamra, R. Challenges for organisational resilience. Contin. Resil. Rev. 2019, 1, 17–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conz, E.; Magnani, G. A dynamic perspective on the resilience of firms: A systematic literature review and a framework for future research. Eur. Manag. J. 2020, 38, 400–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurniawan, F.W.; Rianto, M.R. THE INFLUENCE OF EMPLOYEE ENGAGEMENT , EMPLOYEE JOB SATISFACTION , INNOVATIVE WORK BEHAVIOR ON THE ORGANIZATIONAL RESILIENCE OF PT MITSUBISHI. 2023, 1, 429–436.

- Khuan, H. Strategies and Best Practices Membangun Ketahanan Organisasi di Era Ketidakpastian : Strategi dan Praktik Terbaik. 2024, 1, 1–11.

- Douglas, S.; Haley, G. Connecting organizational learning strategies to organizational resilience. Dev. Learn. Organ. 2024, 38, 12–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orth, D.; Schuldis, P.M. Organizational learning and unlearning capabilities for resilience during COVID-19. Learn. Organ. 2021, 28, 509–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evenseth, L.L.; Sydnes, M.; Gausdal, A.H. Building Organizational Resilience Through Organizational Learning: A Systematic Review. Front. Commun. 2022, 7, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koh, S.C.L.; Suresh, K.; Ralph, P.; Saccone, M. Quantifying organisational resilience: an integrated resource efficiency view. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillmann, J.; Guenther, E. Organizational Resilience: A Valuable Construct for Management Research? Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2020, 00, 1–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adini, B.; Cohen, O.; Eide, A.W.; Nilsson, S.; Aharonson-Daniel, L.; Herrera, I.A. Striving to be resilient: What concepts, approaches and practices should be incorporated in resilience management guidelines? Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2017, 121, 39–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tasic, J.; Amir, S.; Tan, J.; Khader, M. A multilevel framework to enhance organizational resilience. J. Risk Res. 2020, 23, 713–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiig, S.; Fahlbruch, B. Exploring Resilience: A Scientific Journey from Practice to Theory; 2019; ISBN 978-3-030-03188-6 978-3-030-03189-3.

- Liu, Y.; Chen, R.; Zhou, F.; Zhang, S.; Wang, J. Analysis of the Influencing Factors of Organizational Resilience in the ISM Framework : An Exploratory Study Based on Multiple Cases. Sustain. 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Son, C.; Sasangohar, F.; Neville, T.; Peres, S.C.; Moon, J. Investigating resilience in emergency management: An integrative review of literature. Appl. Ergon. 2020, 87, 103114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Essuman, D.; Boso, N.; Annan, J. Operational resilience, disruption, and efficiency: Conceptual and empirical analyses. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2020, 229, 107762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verreynne, M.L.; Ford, J.; Steen, J. Strategic factors conferring organizational resilience in SMEs during economic crises: a measurement scale. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2023, 29, 1338–1375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, H.-W.; Shih, H.-C.; Liao, M.-I. Circular Economy and New Research Directions in Sustainability. In International Series in Operations Research and Management Science; 2021; Vol. 301, pp. 141–168.

- Rosen, M.A.; Dietz, A.S.; Yang, T.; Priebe, C.E.; Pronovost, P.J. An integrative framework for sensor-based measurement of teamwork in healthcare. J. Am. Med. Informatics Assoc. 2014, 22, 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Dé, L.; Wairama, K.; Sath, M.; Petera, A. Measuring resilience: by whom and for whom? A case study of people-centred resilience indicators in New Zealand. Disaster Prev. Manag. An Int. J. 2021, 30, 538–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bocken, N.M.P.; de Pauw, I.; Bakker, C.; van der Grinten, B. Product design and business model strategies for a circular economy. J. Ind. Prod. Eng. 2016, 33, 308–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walters, J.P.; Véliz, K.; Vargas, M.; Busco, C. A systems-focused assessment of policies for circular economy in construction demolition waste management in the Aysén region of Chile. Sustain. Futur. 2024, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arranz, C.F.A.; Sena, V.; Kwong, C. Dynamic Capabilities and Institutional Complexity: Exploring the Impact of Innovation and Financial Support Policies on the Circular Economy. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 2023, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardini, L.; Fahlevi, M. Circular economy from an environmental accounting perspective: Strengthening firm performance through green supply chain management and import regulation in Indonesia’s plastic recycling industry. Uncertain Supply Chain Manag. 2024, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parchomenko, A.; Nelen, D.; Gillabel, J.; Rechberger, H. Measuring the circular economy - A Multiple Correspondence Analysis of 63 metrics. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sgambaro, L.; Chiaroni, D.; Lettieri, E.; Paolone, F. Exploring industrial symbiosis for circular economy: investigating and comparing the anatomy and development strategies in Italy. Manag. Decis. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Bueren, B.J.A.; Argus, K.; Iyer-Raniga, U.; Leenders, M.A.A.M. The circular economy operating and stakeholder model “eco-5HM” to avoid circular fallacies that prevent sustainability. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherrington, R.; Manolchev, C.; Edwards, K.; Housni, I.; Alexander, A. Enabling circular economy practices in regional contexts: Insights from the UK Southwest. Int. J. Entrep. Innov. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segarra-Blasco, A.; Teruel, M.; Tomàs-Porres, J. Circular economy and public policies: A dynamic analysis for European SMEs. Bus. Strateg. Environ. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skare, M.; Gavurova, B.; Kovac, V. Investigation of selected key indicators of circular economy for implementation processes in sectorial dimensions. J. Innov. Knowl. 2023, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ford, P.; Fisher, J. Designing consumer electronic products for the circular economy using recycled Acrylonitrile Butadiene Styrene (ABS): A case study. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bressanelli, G.; Pigosso, D.C.A.; Saccani, N.; Perona, M. Enablers, levers and benefits of Circular Economy in the Electrical and Electronic Equipment supply chain: a literature review. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, O.; Watson, N.; Escrig Escrig, J.; Gomes, R. Intelligent Resource Use to Deliver Waste Valorisation and Process Resilience in Manufacturing Environments. 2020, 64, 93–99. [CrossRef]

- Kristoffersen, E.; Blomsma, F.; Mikalef, P.; Li, J. The smart circular economy: A digital-enabled circular strategies framework for manufacturing companies. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 120, 241–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Florez-Jimenez, M.P.; Lleo, A.; Danvila-del-Valle, I.; Sánchez-Marín, G. Corporate sustainability, organizational resilience and corporate purpose: a triple concept for achieving long-term prosperity. Manag. Decis. 2024, ahead-of-p. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).