1. Introduction

In today's fast-paced corporate environment, the outdated management paradigm that puts an emphasis on maximization of profit and productivity is completely out of place. Innovation and capitalizing on changes in the environment are critical to a company's sustainability viability and competitiveness. Companies in today's uncertain business climate need to be creative, resilience and well-informed to thrive.

Recently, a growing trend for businesses reconsidering social responsibility and acknowledgement that financial gain is not necessarily the most critical indicator of sustainability. The integration of sustainable development (SDG) goals into the footing of business decision-making has thus been the subject of much recent research on sustainable business models. The purpose of present study is to add to existent literature, outlining a theory and practice-based framework that can help organizations move towards a more sustainable development paradigm. The framework will highlight the key elements that businesses need to align their competitive performance with sustainability goals.

In addition to focusing on economic goals, governments are increasingly concerned with environmental protection and meeting social needs. Thus, many companies have put a premium on enhancing their capacity for innovation to fortify their positions in the market and ensure their long-term viability [

1,

2]. The capacity of a company to meet consumer demands through the introduction of innovative or enhanced goods, services, processes, and marketing strategies is defined as innovation in the literature [

3,

4,

5]. Hanaysha and Hilman [

6] state that companies are confronted with significant problems on sustainability policies, and that innovation is the key to overcoming these problems, even as it helps businesses stay and even increase their long-term performance.

According to Fernández et al. [

7], environmentally conscious businesses prioritize processes and goods that reduce resource use and increase energy efficiency. In addition, they discovered that companies that prioritize innovation to reduce environmental impact often aim to improve energy efficiency through their innovations. Despite the widespread belief that an organization's capacity to innovate is a critical factor in its success or failure, few studies have really examined the correlation between innovation and the long-term viability of businesses, especially in the context of small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). Few empirical studies on innovation capacities have limited focus on product, process, or service development as the only few areas where companies can expand their innovation capabilities [

8,

9], as it relates to sustainability [

10,

11]. Therefore, this study would add to the existing body of knowledge by considering the influence of innovation capability on the sustainability viability of SMEs.

Furthermore, companies in today's fast-paced business world face a multitude of obstacles that require constant adaptation if they want to competitive and constantly survive. To adapt in a sustainable way, organizations have been looking to the environment more and more in the last two decades [

12,

13]. The existing literature has made some progress, but it still lacks answers to important concerns about how to best foster ecosystems for innovation and resilience. Further exploration and embedding factors such as environmental dynamism, resilience, sustainable competitive advantage, and innovation (creation, improvement, expansion, contraction, or change) are required to ensure sustainability in business operations, particularly among SMEs on a developing nation like Nigeria.

2. Review of Relevant Literature

2.1. Theoretical Framework

2.1.1. Contingency Theory

The core tenet of contingency theory is that an organization's internal strategies and resources must be compatible with external factors that the organization cannot control. A multitude of factors, including its internal processes, external environment, and structure, determine a corporation's success, according to the contingency method. In response to challenges like these, companies often take on new stances that better suit the communities in which they do business. Adopting the tenets of contingency theory means realizing that a company can't control its external environment; thus, it must pay great attention to competitors’ products, customer demands, and market conditions if it wants to be successful. Organizational success and improved performance are outcomes of paying attention to the outside world and adjusting plans appropriately [

14,

15]. Considering the importance of comprehending the effects of an organization's exposure to an uncertain external environment on its structure, strategy, and context, this study employs contingency theory grounded in the research of Rauch et al. [

14] and Yeoh & Jeong [

15].

2.1.2. Capability-Based Theory

Several studies in the field of strategy have presented SCA's capability-based theory as a means by which a company can gain an advantage over its rivals. These studies include [

16,

17], who adapt more quickly to changing market dynamics and capitalize on emerging possibilities. The term "capabilities" emphasizes the role of strategic management in Capability-Based Theory (CBT) in reshaping an organization’s resources, competencies, and functional competences to match the needs of a dynamic and unpredictable environment. Teece et al. [

18] assert that a company's competitive advantage stems from its unique and hard-to-replicate resources, which originate "upstream" from product markets. Companies require the capacity to "integrate, build, and reconfigure internal and external competencies to address rapidly changing environments"[

18]. When it comes to sustainability, the current industrial mindset is deficient in identifying potential problems and solutions. Despite a substantial deal of literature on sustainable business model theory development, our knowledge of how to combine sustainability with competitive advantage strategies is lacking [

19,

20,

21].

In recent years, strategy research has seen a rise in the CBT of Sustainable Competitive Advantage, which proposes that a company can gain an advantage in the market by capitalizing on its unique strengths. By giving important decision-makers a proactive and dominating role, CBT elucidates the value generation process. Capability-based theory gives a compelling rationalization of value creation by placing the firm's most important decision-makers in leadership and initiative positions.

2.1. Conceptual review and Hypothesis Development

2.2.1. Innovation Capabilities

Innovative capabilities, which in turn foster innovation, are responsible for companies' exceptional performance and ability to remain competitive in their respective industries [

22,

23]. For companies to adapt and stay afloat in ever-changing marketplaces, they continuously look for ways to enhance their innovation capabilities when they've been up against intense competition [

24,

25]. Innovation capacity defines an organization's ability to consistently transform domain and application specific knowledge into novel outcomes [

26].

An organizational innovation capability consists of its internal capacity to consistently generate new ideas and increase firm and stakeholder value [

27]. Firms' capacity to innovate can also be defined in terms of the factors that influence their innovation management [

28]. According to Ballor and Claar [

29], entrepreneurs place an emphasis on pushing people in the organization to develop the current knowledge system through innovation and propagation of those innovation traits. All businesses can achieve higher levels of innovation when they use all four skills, and the actual strength of this classification led us to adopt it [

30]. Empirical studies from a variety of economic and industrial backgrounds have previously examined and validated it [

22,

31,

32]. According to Zawislak et al. [

33], a firm's ability to innovate relies on the people, systems, and processes it employs to transform existing bodies of knowledge into marketable products and services. In a turbulent environment, a corporation must be innovative. Innovative performance requires innovative capabilities.

2.2.2. Environmental Dynamism

Environmental dynamism denotes the inherent unpredictability of the frequency at which changes occur in the external environment [

34]. Organisations are promptly managing environmental instability and other risks while also seeking new commercial prospects in reaction to the more unpredictable climate changes [

10,

35]. According to Hou et al. [

36] and Schilke [

37], a dynamic environment involves uncontrollable factors that impact the firm. In times of uncertainty, companies must be extremely nimble with their funds, individuals, and opinions, and they must be dead set on making decisions. The dynamic environment remains unstable and unpredictable with the market's product offerings, technological changes, and client demand. Extremely dynamic and unpredictable environments accruable to situations, such as abrupt demand changes, short-lived competitive advantages, and low-slung barriers to entry and exit, foster a climate of uncertainty and unpredictability [

38]. In most emerging nations, SMEs have had to get creative with their financial problems due to economic unpredictability and severe industry competition.

2.2.3. Sustainable Competitive Advantage

Going by international competitiveness, two distinct forms of competitive advantage exist. The first is the transitory competitive advantage, which has a large profit margin but doesn't last forever. A second type of competitive advantage is one that can last as long as the source of the advantage remains unchanged [

39].

Organizations, even in the face of agile situations and rapid changes in technology life cycles, can benefit from a sustainable competitive advantage to maintain smooth business operations. Consequently, it helps organizations reap benefits in the long run while warding off strategic competitors [

40]. In conclusion, firms realize continuous competitive advantage by focusing on their strengths rather than trying to emulate their competitors' strategies [

41,

42].

2.2.4. Organizational Resilience

A resilience organization tends to sustain operations of their enterprise using innovative ideas in creating product, process, structure and market [

4,

43]. In today's uncertain and volatile business climate, it is essential for organisations to cultivate resilience. This will help them deal with failures, recover quickly, and ultimately succeed in the future. To thrive in unpredictable situations and ensure long-term sustainability, companies need to be prepared to deal with all these unforeseen twists and turns.

Golgeci and Ponomarov [

44] describe organizational resilience as a crucial component of firm stability, with innovation being the main factor that drives its adaptability. Results from their study on supply chain management show a strong correlation between innovativeness and resilience. Other researchers use a capability-based understanding of resilience, viewing it as a capacity or ability [

45,

46]. Carvalho et al. [

47], Rose [

48], Sheffi and Rice Jr. [

49], Teixeira and Werther [

50], referring to organizational resilience" as being able to anticipate and deal with disruptions and surprises, both internal and external, through strategic awareness and related operational management. A company's resilience can be either static, based on preemptive actions to lessen the likelihood of threats and their effects, or dynamic, based on responsiveness to interruptions and surprises, mitigating negative effects as quickly as possible and maximizing the company's capacity to maintain status quo. Hence, companies that are resilient are better able to take advantage of opportunities and compete with others throughout time [

51].

2.2.5. Business Sustainability

According to earlier definitions [

52,

53], sustainability is the capacity to meet social and economic demands without negatively impacting the environment. According to Akadiri and Fadiya [

54], business sustainability encompasses elements, features, or aspects related to a firm's functioning. Furthermore, business sustainability refers to the consistency in business conditions. This occurs when a company continues to grow and develop, employs strategies to ensure its continued existence, and creates new products and services [

55,

56].

Aninkan and Oyewole [

57] and Eccles, Ioannou, and Serafeim [

58] both noted that the construct; organizational sustainability has received increased awareness from academia, and business executives in the past 20 years. Long-term success, however, depends on organizational sustainability, which in turn boosts short-term performance (such as earnings) and employee attitudes and behaviors (such as engagement, knowledge sharing, and creativity) at the workplace. According to Hart and Milstein [

59] and Spreitzer, Porath, and Gibson [

60], sustainable businesses can simultaneously improve their efficiency in three different areas: financial, ecological, and societal (or human). To attain and sustain growth, firms must have a comprehensive strategy that considers the financial, social, and environmental (i.e., human) components of expansion.

In relation to sustainability, businesses ought not to limit their concentration to creating shareholder value; rather, they should think about how their operations will affect society, environment, and their employees [

61]. Finally, benefits of sustainability practices will manifest in increasing profit, better products and satisfaction, increased organizational commitment, a better brand reputation, the possibility of receiving government funding, savings from more environmentally friendly logistics and supply chains, and less money spent on environmental liability and regulation.

2.2.6. Innovation Capability and Business Sustainability

Businesses prosper in today's market because they are constantly inventing new, technologically improved items through R&D efforts. Within the context of innovative capacities, [

62,

63] evaluated the impact of product, marketing, and process innovation on company performance all at once. According to Li et al. [

64], and Durge and Sangle [

65], when organizations follow a sustainability perspective in their research and development, they can create products that are competitive, environmentally friendly, socially responsible, technically advanced, compliant globally, and efficient with resources.

In the study of Rauter et al. [

11], it was found that sustainable firms and creative goods both had strong relationships. Another crucial organizational strategy that has received a lot of attention is service innovation, which is a component of innovation capability. Sundbo and Gallouj [

66] used the term "service innovation" to describe the process by which businesses innovate to improve service delivery and customer support. Innovative service offering increases customer satisfaction and value [

1,

67]. Several studies have shown that innovation boosts business sustainability and performance [

10,

11], and market positions and competition [

8,

68].

Also, everyone knows that process innovation is a beneficial way for businesses to reach their goals. Advances to operational procedures, tools, and technologies used by businesses are essential to process innovation. Companies innovate their processes to provide customers with faster service and more value [

5]. Consequentially, process innovations that meet regulatory standards may lead to better environmental sustainability. When they said that process innovation helps entrepreneurs improve the sustainability of their firms as affirmed by [

11].

Additionally, marketing innovation is a critical type of innovation that significantly impacts business growth. According to the research, marketing innovation is when a company can successfully plan and execute marketing campaigns that address not only consumer wants but also business objectives and greater social concerns. An organization is involved in innovative marketing when it finds new ways to connect with customers, alters their perceptions of its offerings, and expands into untapped markets. A company's ability to innovate is an important part of effective marketing, which boosts the company's sustainability [

69]. Thus, the idea implies that

Hypothesis 1: Innovation capability has a positive effect on business sustainability.

2.2.7. Innovation Capability and Sustainable Competitive Advantage

Within the broader framework of capability-based theory, a company gained sustainable competitive advantage (SCA) when it possesses unreplaceable financial and strategic advantages over its rivals. There may be a connection between encouraging innovation and striving for a competitive advantage. To stay ahead of the competition, organizations must constantly innovate and find new ways to improve consumer value [

70]. Proponents of the idea that innovation helps businesses gain an edge in the market and boost their performance include [

71,

72]. One could argue that thriving SMEs are characterized by their ability to innovate.

Some have hypothesized an intimate connection between the processes of innovation and competitive advantage. Firms get a competitive edge when they create new ways to carry out tasks within the value chain to increase customers’ value [

70]. Innovative capabilities are what separate the successful, growing SMEs from the unsuccessful ones. According to a recent Australian study [

73], SMEs leverage both technical and non-technical innovations to derive competitive edge in market both locally and internationally. Consequently, it is hypothesized that

Hypothesis 2: Innovation capability has a positive and significant effect on Sustainable Competitive Advantage.

2.2.8. Sustainable Competitive Advantage and Business Sustainability

Developing and sustaining a competitive advantage is of crucial significance in today's corporate environment. One way to think about SCA is as a better "marketplace position," enabling businesses to provide better customer value and/or achieve lower relative costs [

74]. According to capability-based theory, a sustainable firm has a competitive advantage when its financial and market returns become unmatched by its competitors, as well as if it cannot replicate the competitive strategy that has given it these advantages [

75].

Companies in today's fast-paced markets need to constantly evaluate their internal and external environments to understand their customers' needs and wants, as well as how to best use their resources to tackle new problems and stay ahead of the competition [

76]. Adopting sustainability practices is seen as a strategy for a corporation to boost consumer loyalty, attain competitiveness, and improve a company's reputation [

77]. Certain research on corporate sustainability suggests that a company's adoption of sustainable business practices positively impacts brand value attributed to a specific competitor [

78,

79]. Dyllick and Muff [

80] assert that sustainable organizations possess superior competitive advantages, which include a more developed brand reputation, lower risks, and a greater interest among talent. The investigation foregrounds the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 3: Sustainable Competitive Advantage has a positive and significant effect on Business Sustainability

2.2.9. Roles of Organizational Resilience and Environmental Dynamism

Nowadays, the idea of sustainability is gaining prominence all over the world [

81,

82]. Ever since then, companies have shifted their attention from solely focusing on financial gains to also taking social and environmental issues into account. If customers require adjustments or competitors quickly modify the product offered, it will be critical to adapt quickly. Firms must be alert and adaptable enough to quickly respond to changing conditions. According to Jansen et al. [

83], companies increase product innovation in high-stakes, dynamic environments by fostering a new way of thinking about and doing things. Put simply, businesses can turn external environmental disruptions into gains.

There has been a lot of scholarly focus on the ways in which factors external to organizations affect innovation [

83,

84,

85]. The level of dynamism is an integral part of the external environment that affects how well an organization operates. Technologies, consumer tastes, and material demand and supply are all examples of variables that can quickly change in a dynamic context. In such a setting, present goods and services often become stale. Businesses can't help but innovate and enhance their offerings in response to the constant shifts in consumer demand and industry standards. Uncertainty is a hallmark of dynamic ecosystems. Companies frequently have little data and make inaccurate forecasts about what will work since their environment is changing at such a rapid pace. Consequently, innovation is riskier in dynamic environment.

According to Bolton, Habib and Landells [

86], in their study envisage that when people and institutions encounter extraordinary difficulties, resilience is typically thought of as the capacity to bounce back and continue operating normally, as being a major challenge considering the complicated and continuing instability that people in different cultural and sectoral contexts experience, taking Philippines microfinance institution as a case study. The findings outlined that to foster transformative resilience behaviors in ever-changing ecosystems, it is crucial to uphold cultural consistency in purpose, values, and capabilities.

A company's resilience depends on its capacity to restructure and improve its operations in response to unexpected changes in the market [

87]. Meanwhile, to build resilience capacities in these situations, firms should participate in practice drills that mimic future market scenarios. These drills will assist them in assessing their resilience levels, identifying the type of resilience they require, and identifying the areas where it is most critical. Companies may only achieve resilience as a sustainability strategy if they comprehend its importance and begin to cultivate it early on; however, these exercises will eventually make adaptability an integral aspect of the firm's business culture [

87].

Given that various firms have diverse cultural approaches to resilience, one could wonder if building resilience is easier said than done when considering resilience as a corporate sustainability strategy. The intricate nature of grasping resilience depends on what traits enable an organisation to maintain its core operations and, thus, its capacity to resist or recuperate from upheavals. A company's ability to weather future storms depends on its capacity for resilience. The researchers have derived these assumptions from the premise:

H4: Environmental Dynamism (EVD) significantly mediates the relationship innovation capability and business sustainability.

H5: Organizational Resilience (OGR) significantly mediates the relationship innovation capability and business sustainability.

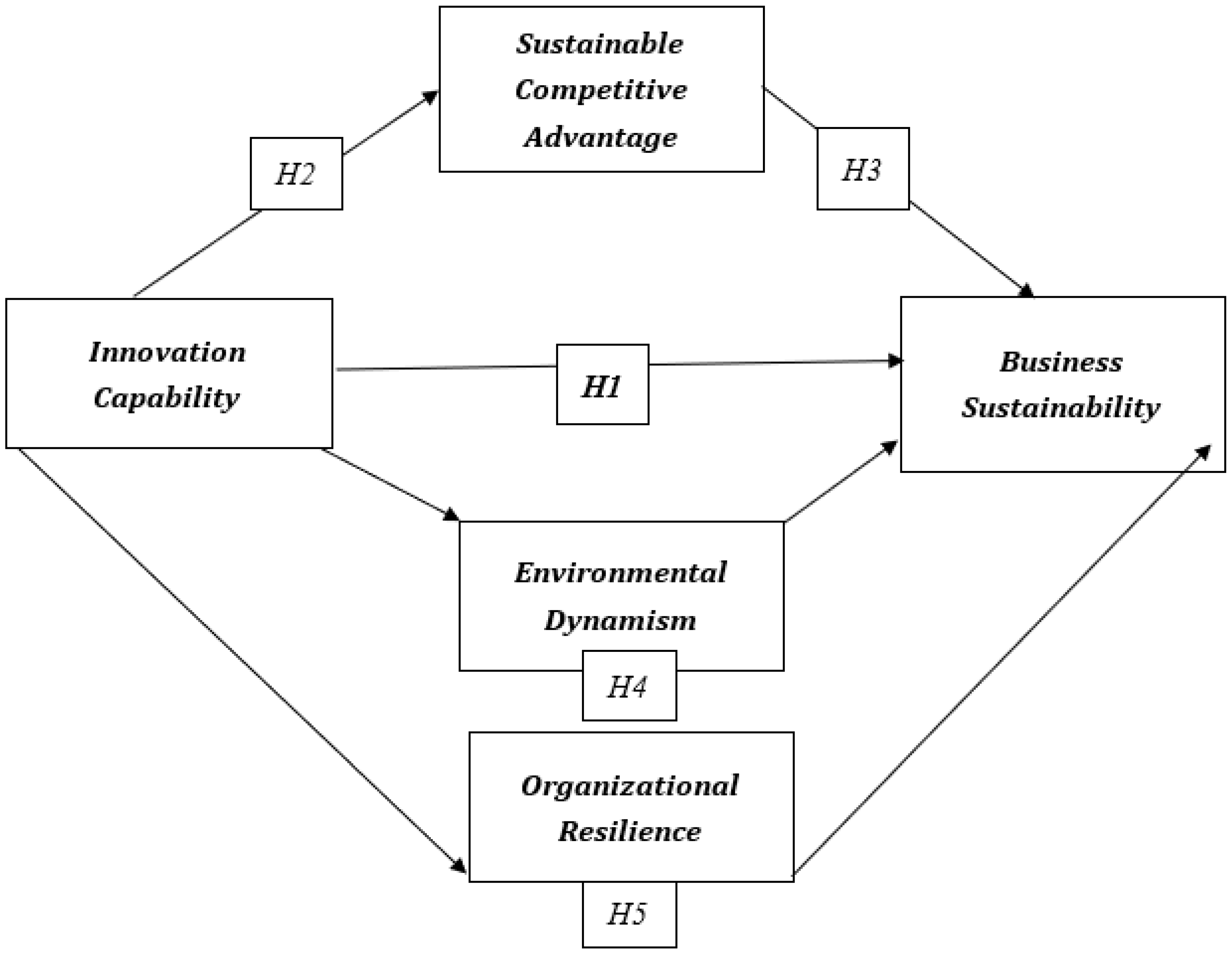

To achieve sustainable development, it is required to build a framework of interrelationships between the various variables, as shown in

Figure 1.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Sampling Procedure and Characteristics

This research focuses on Lagos State Metropolis because it is the most industrialized center in the country and has the highest number of SMEs in Nigeria. This study employed a cross-sectional method to explore on the effect of INV on BUSS in SMEs in Lagos Metropolis, Nigeria. The researcher acquired data through a structured quantitative survey. Specifically, the SMEs which were selected as sampling frame include respondents from diverse business sectors such as manufacturing, services, restaurants, wholesale, and retailing. The researcher surveyed 401 respondents using a simple random sampling technique, targeting them as managers and owners of SMEs. Once a list of responses from the chosen businesses was generated, the researcher approached them about participating in the study. The researcher used the following processes to acquire the data, spanning from July to December 2023. (a) Two business professionals in the field and two professors from different universities reviewed and approved the questionnaires to make sure they were clear and relevant; (b) Before sending the surveys, the researcher contacted the participants to explain the study's aims and get their consent to participate; (c) The participants were guaranteed complete anonymity and the utmost confidentiality of their data; and (d) A few recommendations on how to fill out the surveys were included to minimize possible errors.

The study sample comprises 46.6% males and 53.4% females, as shown in

Table 1. On average, the majority are married and fall within the age range of 41–50 years, with the youngest being under 30 years old. The analysis of their educational qualifications showed that the majority (51.6%) had a bachelor's degree, followed by a diploma or NCE (26%), and the least had a postgraduate degree as their highest qualification. Finally, regarding business operation experience, it was established that most respondents had operated a small trade business for quite a period (5-10 years), while 22.9% of the respondents had less than 5 years’ experience. The remaining participants affirmed that they had more than ten years of experience in the business line.

3.2. Measures and Analytical Technique

To develop the questionnaire, the researcher reviewed the existing literature on the chosen constructs. The researcher adopted nine items from the scale developed by [

88], as cited by [

89], to assess business sustainability. Furthermore, the researcher measured innovation capability using 5 items from the studies of [

10,

43,

90]. Hou et al. [

36] cited the four validated items developed by Jansen et al. [

91] to measure environmental dynamism. Prahalad [

41], Snow and Hrebiniak [

42], and Rahmat [

92] developed a six-item assessment of sustainable competitive advantage, viewing it across core competencies and distinctive competencies. Finally, we adopt a 5-item scale to assess organisational resilience using the research of [

93,

94,

95]. The researchers employed and adapted a five-point Likert scale from previous research, where 1 signifies a strongly disagree option and 5 indicates a strongly agree option. Finally, the researchers used descriptive statistics and "Partial Least Square Structural Equation Modelling" (PLS-SEM) to check basic assumptions and describe the data that was gathered. This study analyzed the model fit using metrics such as the "standardized root mean square residual" (SRMR), the "normal fit index," and others to determine how well the research model matches the data.

4. Results

4.1. Analysis of Results

This study used the full collinearity test, available in the next part, as well as Harman's CFA and single factor test (1960) to confirm the potential presence of common method variance bias among constructs. When all 29 measurement items for the constructs were put on a single common factor, the general latent variable's overall variance explanation fell below Harmin's threshold value of 50%, which means that there was no common method bias in the final model.

4.2. Multicollinearity Test and Correlations

Establishing confidence, the data is free of major flaws requires testing for multicollinearity before proceeding on to further analysis. If the correlation between two or more variables in the model is 0.9 or higher, we consider them multicollinear [

96]. We can examine it using several techniques. But we focused on the VIF—the most popular metric—to compare things. The statistical analysis in

Table 2 shows no indications of multicollinearity, as the VIF values in the whole collinearity test fall within the allowed range (less than 5). Previous research [

97] supports this finding.

4.3. Assessing Measurement Model

Previous studies extensively employ Cronbach's alpha coefficient, known for its precision in assessing internal consistency across measurement items, to evaluate the reliability of measurement scales. The present study also employed this reliability estimate. Business sustainability (0.923), environmental dynamism (0.850), innovation capability (0.818), organizational resilience (0.918), and sustainable competitive advantage (0.867), all had Cronbach's alpha values greater than the lowest threshold of 0.7, as established by [

98,

99]. In addition, we tested the reliability assumptions using composite reliability, and the results demonstrated that all structures have acceptable range values.

Furthermore, the PLS algorithm was used to perform confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) after eliminating surveys with missing data or incomplete responses. We conducted a CFA analysis to ensure the error-free nature of items used for measurement. We used a CFA to guarantee that each construct's items were one-dimensional and to estimate the measurement model before moving on to the structural model and hypothesis testing. To accomplish this, we verified that each measurement component had a factor loading greater than 0.5, as shown in table 3. Furthermore, table 3 reveals that AVEs of all constructs are greater than 0.5, implying that convergent validity is present. Therefore, the end results of CFA have met convergent validity.

4.4. Discriminant Validity

Following the advice of Fornell and Larcker criterion, researchers also conducted a discriminant validity test across all constructs. The authors stress that discriminant validity is reached when the square root of the AVE values for each construct are higher than the correlations between constructs. Hessenler et al. [

100] state that the Fornell-Larcker [

101] criterion was criticized, prompting the development of the heterotrait-monotrait (HTMT) correlation ratio as an alternative. Following Kline's [

102] recommendation, all measurement model structures displayed in

Table 4 have HTMT values below 0.9. According to

Table 4, the assumptions regarding discriminant validity are valid.

4.5. Assessing Structural Model

We used SmartPLS software to extract statistical findings from the structural model, which we then used to test our hypotheses. After maintaining acceptable item factor loadings in the measurement model, as indicated above, it was possible to verify the assumptions.

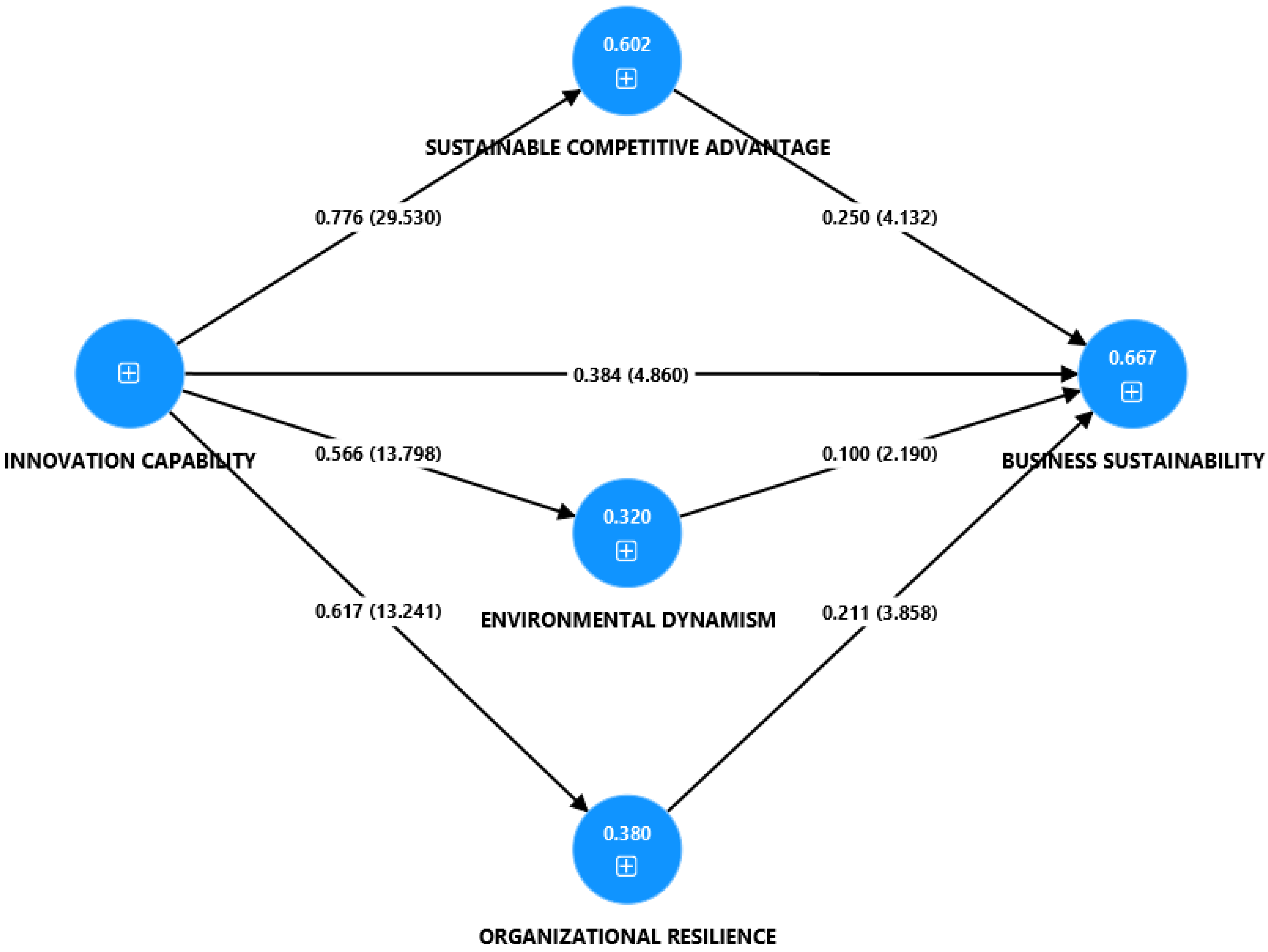

Table 5 displays the results of all tests pertaining to the structural model and the hypothesis relationship. H1 is accepted because, as shown in

Table 5, innovation capability positively affects business sustainability (β = 0.384, t-value = 4.860, p <.05), and significantly impacted sustainable competitive advantage (β = 0.776, t-value = 29.530, p <.05), supporting the acceptance of H2. In conclusion, H3 is approved because the results show that sustainable competitive advantage significantly improves BUSS (β = 0.250, t-value = 4.132, p <.05). Both innovation capability and sustainable competitive advantage can explain a total of 66.7% of the variation in business sustainability, while INV accounted for 60.2 percent of SCA. Thus, it implies that the variables had a high explanatory predictive power (see figure 2).

Environmental dynamism is said to have a large effect on the link between innovation and business sustainability (H4: β = 0.057, t = 2.194, p< 0.05), and organizational resilience is said to fully mediate the relationship (INV→ORG→BUSS) (H5: β = 0.130, t = 3.389, p< 0.05). Reporting the substantive significance (F

2) alongside the beta coefficients (β), statistical significance (p-value), and variance explained (R

2) was lastly suggested by Sullivan and Feinn (2012) [

103]. Cohen [

104] said that path (INV→SCA) had a very high antecedent effect of innovation capability on sustainable competitive advantage because its F

2 value is higher than the high effect threshold (>0.35). On the other hand, paths (BUSS→INV) and (BUSS→SCA) recorded low effect sizes, since the F

2 value fell within the threshold of 0.02-0.15

Finally, when SRMR is below 0.08 and NFI falls within zero and one, indicators like these become essential for evaluating overall goodness-of-fit (GoF). With an SRMR of 0.076 and an NFI of 0.760, the data matches the study model closely. Therefore, the model's correlation coefficient is sufficiently accurate to validate the hypothesis.

5. Discussion

In the context of SMEs, this finding sets out to determine whether innovation capabilities specifically impact company sustainability. Previous studies [

105,

106], have highlighted the importance of innovation in achieving business sustainability. Numerous studies have shown that firms that provide groundbreaking products, comply with acceptable operational norms, and fulfil diverse market demands by enhancing product characteristics have a higher likelihood of long-term success and resilience while competing. Hallstedt et al. [

107] presented further evidence supporting the notion that innovation, namely in terms of product development, has a significant influence on the long-term viability of firms. This is especially true when companies introduce novel products that include distinctive environmentally friendly attributes. This study's findings corroborated the first hypothesis, which postulated that innovation contributes to the long-term viability of businesses. Therefore, we recommend that SMEs prioritize investing in innovations in four domains: product, process, structure, and market. This is because improving their capability is critical to attaining a long-term competitive advantage and sustainability.

Furthermore, the study's results provided support for the second hypothesis, which posited that innovation enhances the sustained competitive advantage of SMEs. The statistical analysis validated that the ability to innovate enhances a company's strategic competitive advantage. The findings are consistent with those of [

69], who examined the relationship between innovation (marketing) and its potential to promote sustainable development. Teguh et al. [

108] conducted a study that analysed the relationship between entrepreneurial marketing and long-term competitive advantage in food and beverage MSMEs through the lens of innovation capability. They discovered that doing good work in this area of innovative capability gives them a long-term advantage over their competitors. Furthermore, [

109,

110] cited prior research that corroborated the requirement for innovation in helping businesses better understand their target markets and consumers' wants and needs to provide superior products and services. Hence, this is required to effectively compete with competitors within the same business line.

In relation to the second hypothesis and affirmation from previous studies, Lee and Hsich [

111] discovered a direct correlation between a firms’ innovation capability and its competitive advantage. Research by [

112,

113,

114], all came to the same conclusion: innovation greatly impacts performance and competitive advantage. [

115] demonstrated that the company's age significantly influences the benefits of innovation on competitive advantage. Innovations in processes and products positively impact organizational competitive advantage [

116]. In conclusion, businesses and SMEs that are continuously seeking out innovative approaches to sustainable design and quality will be the first to reap the rewards. Thus, the capacity to innovate in the areas of design, product, process, marketing, and service will foster excellence in performance and long-term competitive advantage.

Hypothesis 3 asserted that a firm can sustain a competitive edge over an extended period, receives more logical support from the study. Supporting the claims made by Baker et al. [

117] and Porter [

118], there is evidence that a sustainable competitive advantage promotes business sustainability, according to Porter [

119], who calls competitive advantages a companion for competitive strategy. On the contrary, [

120] argues that unfavourable attitudes and values might greatly hinder a company's capacity to sustain its competitive advantage in the foreseeable future. However, the study's findings do not fully corroborate the literature, they do provide credence to capital-based theory, which has relied on scant research to date in its quest to define competitive advantage in business environments.

The fourth hypothesis posits that environmental dynamism serves as a mediator between the capacity for innovation and the long-term sustainability of enterprises. The mediation effect leads to a more evident manifestation of the innovation dimension and the ability of small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) to leverage environmental measures for their long-term business success. Small and medium-sized firms (SMEs) operating in highly dynamic environments had far higher returns from innovation. This unexpected finding underscores the significance of employing flexible strategies to address evolving environmental conditions and demonstrates how small and medium-sized firms (SMEs) can use environmental issues to achieve sustained success.

Effective management of environmental dynamism is critical for an organization's long-term performance because it guides the company to acquire, adapt to, and implement dynamic changes in the environment [

121]. Extending beyond the initial assumptions, the findings indicate that environmental dynamism plays a mediating role. Environmental dynamism, which brings to light the environmental challenges faced by firms, can help in meeting customer demand, maximizing profitability, and ensuring a sustainable future [

122]. Conversely, firms face the possibility of financial losses if they disregard changes in their environment. Therefore, if SMEs fail to consider environmental dynamic factors while pruning, sustainability is at risk. Despite the growing awareness among businesses about the long-term social and environmental consequences, firms often fail to consider how they may contribute to addressing sustainability issues at the local, national, or global scale [

80]. Nevertheless, businesses that are truly sustainable aim to positively impact society and the environment through innovation.

The study fully supported H5, which examines the mediating role of organizational resilience on innovation capability to business sustainability. Enterprises can demonstrate resilience and implement the necessary modifications as part of their sustainability strategy. Even though business failure is an unanticipated and unavoidable interruption to their economic activity, resilience can empower them to provide results (solutions) regardless of the intensity of the disruption they face. Firms may enhance their ability to withstand unpredictable change and thrive in the new normal market environment by redirecting their focus from the concentration of disruptions they encounter to the level of tolerance they can maintain. To promote resilience as a sustainable strategy for enterprise transformation, modern firms, such as SMEs, must avoid complacency and integrate agility and flexibility into their resilience culture. Hence, resilience and sustainability have become critical issues for a sustainable future amid extraordinarily difficult financial conditions.

6. Conclusion

The present study majorly focusses on sustainable business performance among Nigerian SMEs. This study aims to investigate the roles of environmental dynamism and organizational resilience in achieving a sustainable competitive advantage and sustainable business performance, with innovation capability serving as a crucial antecedent. The results show that models for sustainable development want to improve the "business as usual" view by using a more axiological and systemic approach. For example, this study is based on SDG 9 (industry, innovation, and infrastructure). Therefore, innovation capability plays a crucial role in enhancing the positive impact of SCA on BUSS. Finally, the presence of environmental dynamics and resilience in organizations like SMEs ensures innovation capability, which increases SMEs' sustainable business performance. Therefore, we urge businesses to implement these sustainable practices to stay competitive and meet the growing customer demand for high-quality products and services.

6.1. Implications of the Study

Present findings offer foremost inferences for managers and business practitioners. Firstly, managers need to understand that for their companies to gain unique competitive advantages, business sustainability is crucial. To achieve their goals, business professionals may use the suggested framework to try to incorporate innovation tactics and sustainability practices into their companies. To recap, the most effective strategy for a company to achieve long-term success and survival is to innovate. With competition heating up in today's fast-paced business world, companies are under pressure to innovate to stay ahead of the competition.

This study contributes to the repository of literature on sustainable business practices as they pertain to SMEs by expanding our grasp of the interplay between innovation capacity, organizational resilience, sustainable competitive advantage, and environmental dynamism. We empirically validate our conceptual framework and provide practical insights for small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) seeking to integrate environmental concerns into their strategic agenda. This will help them better handle complex environmental challenges and achieve long-term sustainability in their business.

Furthermore, we think this study adds to what is already known about the connections between SME innovation capabilities and the sustainability of the company. With any luck, this study will pave the way for additional theoretical elaboration and empirical investigation in this important area of study. Firms should prioritize strengthening their innovation capabilities while implementing sustainable practices, according to the statistical data. This tends to be valid when launching new products and building or improving production processes to boost performance. An important asset of any company is its capacity to create new and useful things, whether that's through improvements to its processes, services, marketing, or products. Accordingly, business owners and practitioners can use the research's practical implications to better understand how to invest in innovation to boost sustainability performance. Considering the foregoing, we are of the opinion that SMEs benefit greatly from innovative skills, which allow them to achieve their economic, social, and environmental performance goals. We also advise business practitioners to form fruitful partnerships with supply chain participants, which could aid them in developing innovative, environmentally friendly goods. To reduce costs and environmental impact, they should adopt new marketing strategies that make use of internet technologies and implement efficient operational procedures.

6.2. Limitations and Future Research

Several caveats should be considered for potential future expansions of this study. The main rationale of this research was to investigate the impact of innovation capability on business sustainability. We expect further study to analyse BUSS (economic, environmental, and social) and INV (product, process, service, and market) as second-order constructs, explicitly addressing their dimensions. Secondly, future research can expand geographical location to a developed nation and scope to include related and larger competitive industries, such as manufacturing, FMCG, and agro-allied companies.

Furthermore, consideration of the intervening variables as a mediator or moderator seems to be a novel idea in establishing sustainability, as well as introducing control variables like age of enterprise, monthly income, and educational background. In addition, we restricted this study's sample size to SME owners and managers. Hence, to avoid violating the validity and trustworthiness of the results, future studies should use larger samples and focus on reactions from an employee perspective in the context of employee resilience and employee co-innovation. Finally, the study's data originated from Nigeria (a developing nation); future researchers can always try to replicate the model in other parts of the world to see if it works, most especially in an undeveloped nation.

Acknowledgments:

Thanks to all Anonymous reviewers for their academic effort in ascertaining quality research.

Conflict of Interests

In the present study, the authors have not identified any potential conflicts of interest.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, BRO and TJS; Methodology, BRO; Validation, JNL and NK; Formal analysis, BRO and AAWA; Investigation, NK and TJS; Resources, TJS and JNL; Data curation, BRO and AAWA; Project administration, AAWA, NK, TJS and JNL. The final published version of the manuscript has the unanimous approval of all authors.

Informed Consent Statement

Before participating in the study, all participants gave their informed consent.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to restrictions, but can be made available upon reasonable request

References

- Hanaysha, J. R.; Al-Shaikh, M. E.; Joghee, S.; Alzoubi, H. M. Impact of innovation capabilities on business sustainability in small and medium enterprises. FIIB Business Review, 2022, 11(1), 67-78. [CrossRef]

- Adams, R.; Jeanrenaud, S.; Bessant, J.; Denyer, D.; Overy, P. Sustainability-oriented innovation: A systematic review. International Journal of Management Reviews, 2016, 18(2), 180-205. [CrossRef]

- Mustapha, B.; Olaleye, B. R.; Yetunde, O. B.; Olanike, O. O.; Akindele, G.; Abdurrashid, I.; Adedokun, J. O.; Bamidele, J. A.; Owoniya, B. O. Risk Management Practice and Organizational Performance: The Mediating Role of Business Model Innovation. Journal of Law and Sustainable Development, 2023, 11(4), e892. [CrossRef]

- Olaleye, B. R.; A, Herzallah; O. N. Anifowose. Innovation Capability and Strategic Agility: Contributory Role on Firms’ Resilience among Tertiary Institutions in Nigeria. Modern Perspectives in Economics, Business and Management, 2021, 6, 78-88.

- Lawson, B.; Samson, D. Developing innovation capability in organisations: a dynamic capabilities approach. International journal of innovation management, 2021, 5(03), 377-400. [CrossRef]

- Hanaysha, J.; Hilman, H. Product innovation as a key success factor to build sustainable brand equity. Management Science Letters, 2015, 5(6), 567-576. [CrossRef]

- Fernández, Y. F.; López, M. F.; Blanco, B. O. Innovation for sustainability: the impact of R&D spending on CO2 emissions. Journal of cleaner production, 2018, 172, 3459-3467. [CrossRef]

- Expósito, A.; Sanchis-Llopis, J. A. The relationship between types of innovation and SMEs’ performance: A multi-dimensional empirical assessment. Eurasian Business Review, 2019, 9(2), 115-135. [CrossRef]

- Gunday, G.; Gunduz, U; Kemal, K; Lutfihak, A. Effects of innovation types on firm performance. International Journal of Production Economics, 2011, 133 (2): 662–76.

- Olaleye, B. R.; Lekunze, J. N.; Sekhampu, T. J. Examining structural relationships between innovation capability, knowledge sharing, environmental turbulence, and organisational sustainability. Cogent Business & Management, 2024, 11(1), 2393738. [CrossRef]

- Rauter, R.; Globocnik, D.; Perl-Vorbach, E.; Baumgartner, R. J. Open innovation and its effects on economic and sustainability innovation performance. Journal of Innovation & Knowledge, 2019, 4(4), 226-233. [CrossRef]

- Jennings, P. D.; Zandbergen, P. A. Ecologically sustainable organizations: An institutional approach. Academy of management review, 1995, 20(4), 1015-1052.

- Winn, M. I.; Pogutz, S. Business, ecosystems, and biodiversity: New horizons for management research. Organization & Environment, 2013, 26(2), 203-229.

- Rauch, A.; Wiklund, J.; Lumpkin, G.T.; Frese, M. Entrepreneurial orientation and business performance: An assessment of past research and suggestions for the future. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2009, 33, 761–787. [CrossRef]

- Yeoh, P. L.; Jeong, I. Contingency relationships between entrepreneurship, export channel structure and environment: a proposed conceptual model of export performance. European journal of marketing, 1995, 29(8), 95-115.

- Bari, N.; Chimhundu, R.; Chan, K. C. Dynamic capabilities to achieve corporate sustainability: a roadmap to sustained competitive advantage. Sustainability, 2022, 14(3), 1531. [CrossRef]

- Prahalad, C. K.; Hamel, G. The Core Compefence offhe Corporofion. Harvard Business Review, 1990.

- Teece, D.J.; G. Pisano; A. Shuen. Dynamic capabilities and strategic management. Strategic Management Journal, 1997, 18, 509-33.

- Amui, L.B.L.; Jabbour, C.J.C.; Jabbour, A.B.L.S.; Kannan, D. Sustainability as a dynamic organizational capability: A systematic review and a future agenda toward a sustainable transition. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 142, 308–322. [CrossRef]

- Bocken, N.M.P.; Short, S.W.; Rana, P.; Evans, S. A literature and practice review to develop sustainable business model archetypes. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 65, 42–56. [CrossRef]

- Geissdoerfer, M.; Vladimirova, D.; Evans, S. Sustainable business model innovation: A review. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 198, 401–416. [CrossRef]

- Ostermann, C. M.; Nascimento, L. D. S.; Lopes, C. M. C. F.; Camboim, G. F.; Zawislak, P. A. Innovation capabilities for sustainability: a comparison between Green and Gray companies. European Journal of Innovation Management, 2022, 25(4), 1200-1219. [CrossRef]

- Saunila, M.; Ukko, J. Intangible aspects of innovation capability in SMEs: Impacts of size and industry. Journal of Engineering and Technology Management, 2014, 33, 32-46. [CrossRef]

- Teece, D. J. Explicating dynamic capabilities: the nature and micro foundations of (sustainable) enterprise performance. Strategic Management Journal, 2007, 28(13), 1319-1350.

- Olaleye, B. R. Influence of eco-product innovation and firm reputation on corporate social responsibility and competitive advantage: A mediation-moderation analysis. Journal of Public Affairs, 2023, 23(4), e2878 . [CrossRef]

- Saunila, M. Innovation capability in SMEs: A systematic review of the literature. Journal of Innovation & knowledge, 2020, 5(4), 260-265. [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.; Jiang, W.; Zhao, W. Proactive environmental strategy, innovation capability, and stakeholder integration capability: a mediation analysis. Business Strategy and the Environment, 2019, 28(8), 1534-1547. [CrossRef]

- Le, P.B.; Lei, H. Determinants of innovation capability: the roles of transformational leadership, knowledge sharing and perceived organizational support. Journal of Knowledge Management, 2019, 23(3). [CrossRef]

- Ballor, J. J.; Claar, V. V. Creativity, innovation, and the historicity of entrepreneurship. Journal of Entrepreneurship and Public Policy, 2019, 8(4), 513-522.

- Nascimento, L. D. S.; da Rosa, J. R.; da Silva, A. R.; Reichert, F. M. Social, environmental, and economic dimensions of innovation capabilities: theorizing from sustainable business. Business Strategy and the Environment, 2024, 33(2), 441-461.

- Daniel, V. M.; de Lima, M. P.; Dambros, Â. M. F. Innovation capabilities in services: A multi-cases approach. Academia Revista Latinoamericana de Administración, 2017, 30(4), 490-507. [CrossRef]

- Schiavi, G. S.; Momo, F. D. S.; Maçada, A. C. G.; Behr, A. On the Path to Innovation: Analysis of Accounting Companies› Innovation Capabilities in Digital Technologies. Revista Brasileira de gestão de negócios, 2020, 22, 381-405. [CrossRef]

- Zawislak, P. A.; Cherubini Alves, A.; Tello-Gamarra, J.; Barbieux, D.; Reichert, F. M. Innovation capability: From technology development to transaction capability. Journal Of Technology Management & Innovation, 2012, 7(2), 14-27. [CrossRef]

- Yu, D.; Tao, S.; Hanan, A.; Ong, T.S.; Latif, B.; Ali, M. Fostering Green Innovation Adoption through Green Dynamic Capability: The Moderating Role of Environmental Dynamism and Big Data Analytic Capability. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 10336. [CrossRef]

- Azadegan, A.; Patel, P.C.; Zangoueinezhad, A.; Linderman, K. The effect of environmental complexity and environmental dynamism on lean practices. J. Oper. Manag. 2013, 31, 193–212. [CrossRef]

- Hou, B.; Hong, J.; Zhu, K.; Zhou, Y. Paternalistic leadership and innovation: the moderating effect of environmental dynamism. European Journal of Innovation Management, 2019, 22(3), 562–582. [CrossRef]

- Schilke, O. On the contingent value of dynamic capabilities for competitive advantage: The nonlinear moderating effect of environmental dynamism. Strategic Management Journal, 2014, 35(2), 179-203. [CrossRef]

- Dess, G. G.; Davis, P. S. Porter's (1980) generic strategies as determinants of strategic group membership and organizational performance. Academy Of Management Journal, 1984, 27(3), 467-488.

- Barney, J. B.; Hesterly, W. S. Strategic management and competitive advantage: Concepts and cases. 2006, Harlow: Pearson.

- Ge, B.; Yang, Y.; Jiang, D.; Gao, Y.; Du, X.; Zhou, T. An empirical study on green innovation strategy and sustainable competitive advantages: Path and boundary. Sustainability, 2018, 10(10), 3631. [CrossRef]

- Prahalad, C. K. The Role of Core Competencies in the Corporation. Research-Technology Management, 1993, 36(6), 40–47. [CrossRef]

- Snow, C. C.; Hrebiniak, L. G. Strategy, Distinctive Competence, and Organizational Performance. Administrative Science Quarterly, 1980, 25(2), 317–336. [CrossRef]

- Olaleye, B. R.; Anifowose, O. N.; Efuntade, A. O.; B. S. Arije. Role of Innovation and Strategic Agility on Firms’ Resilience: A Case Study of Tertiary Institutions in Nigeria. Management Science Letters, 2021, 11(1), 297-304. [CrossRef]

- Golgeci, I.; Ponomarov, S. Y. Does firm innovativeness enable effective responses to supply chain disruptions? An empirical study. Supply Chain Management: An International Journal, 2013, 18(6), 604-617. [CrossRef]

- Richtnér, A.; Löfsten, H. Managing in turbulence: How the capacity for resilience influences creativity. R&D Management, 2014, 44, pp. 137–151. [CrossRef]

- Lengnick-Hall, C.A.; Beck, T.E.; Lengnick-Hall, M.L. Developing a capacity for organizational resilience through strategic human resource management. Human Resource Management Review, 2011, 21, 243–255. [CrossRef]

- Carvalho H.; Cruz-Machado, V.; Tavares JG. A mapping framework for assessing supply chain resilience. International Journal of Logistics Systems and Management 2012;12(3):354–73.

- Rose A. Defining and measuring economic resilience to disasters. Disaster Prevention and Management 2004;13(4):307–14. [CrossRef]

- Sheffi Y, Rice Jr JB. A supply chain view of the resilient enterprise. MIT Sloan Management Review 2005;47(1):41–48þ94.

- Teixeira E. D. O.; Werther, W. B. Resilience: continuous renewal of competitive advantages. Business Horizons, 2013;56(3):333–42.

- Nkonoki, E. What are the factors limiting the success and/or growth of small businesses in Tanzania? An empirical study on small business growth. unpublished thesis, 2010. International Business, Arcada University of Applied Sciences, Helsinki.

- Mullens, D. Entrepreneurial orientation and sustainability initiatives in family firms. Journal of global responsibility, 2018, 9(2), 160-178. [CrossRef]

- Drexhage, J.; Murphy, D. Sustainable development: From Brundtland to Rio 2012: Background paper prepared for consideration by the High-Level Panel on Global Sustainability at its first meeting, 2010. New York, NY: United Nations Headquarters.

- Oluwole Akadiri, P.; Olaniran Fadiya, O. Empirical analysis of the determinants of environmentally sustainable practices in the UK construction industry. Construction Innovation, 2013, 13(4), 352-373. [CrossRef]

- Mullan, K. Technology and children’s screen-based activities in the UK: The story of the millennium so far. Child Indicators Research, 2018, 11(6), 1781-1800. [CrossRef]

- Cosbey, A.; Drexhage, J.; Murphy, D. Market mechanisms for sustainable development: How do they fit in the various post-2012 climate efforts? Winnipeg: International Institute for Sustainable Development, 2007.

- Aninkan, D. O.; Oyewole, A. A. The influence of individual and organizational factors on employee engagement. International Journal of Development and Sustainability, 2014, 3(6), 1381-1392.

- Eccles, R. G.; Ioannou, I.; Serafeim, G. The impact of a corporate culture of sustainability on corporate behavior and performance, 2012, 17950,(1), 2835-2857). Cambridge, MA, USA: National Bureau of Economic Research.

- Hart, S. L.; Milstein, M. B. Creating sustainable value. Academy of Management Perspectives, 2003, 17(2), 56-67.

- Spreitzer, G.; Porath, C. L.; Gibson, C. B. Toward human sustainability: How to enable more thriving at work. Organizational Dynamics, 2012, 41(2), 155-162.

- Meng, J. Sustainability: a framework of typology based on efficiency and effectiveness. Journal of Macromarketing, 2015, 35(1), 84-98.

- Lin, R. J.; Chen, R. H.; Kuan-Shun Chiu, K. Customer relationship management and innovation capability: an empirical study. Industrial Management & data Systems, 2010, 110(1), 111-133. [CrossRef]

- Atalay, M.; Anafarta, N.; Sarvan, F. The relationship between innovation and firm performance: An empirical evidence from Turkish automotive supplier industry. Procedia-social and behavioral sciences, 2013, 75, 226-235. [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Li, G.; Tsai, F.S.; Lee, H.Y.; Lee, C.H. The Effects of Corporate Social Responsibility on Service Innovation Performance: The Role of Dynamic Capability for Sustainability. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2739. [CrossRef]

- Durge, V.C.; Sangle, S. Technology, sustainable development, and corporate growth—Striking a balance. World Rev. Sci. Technol. Sustain. Dev. 2020, 16, 105–121.

- Sundbo, J.; Gallouj, F. Innovation as a loosely coupled system in services. International Journal of Services Technology and Management, 2000, 1(1), 15-36.

- Kindström, D.; Kowalkowski, C. Service innovation in product-centric firms: A multidimensional business model perspective. Journal of Business & Industrial Marketing, 2014, 29(2), 96-111.

- Walker, R. M. Internal and external antecedents of process innovation: A review and extension. Public Management Review, 2014, 16(1), 21-44. [CrossRef]

- Mariadoss, B. J.; Tansuhaj, P. S.; Mouri, N. Marketing capabilities and innovation-based strategies for environmental sustainability: An exploratory investigation of B2B firms. Industrial Marketing Management, 2011, 40(8), 1305-1318. [CrossRef]

- Porter, M. E. Competitive Strategy, Free Press, New York. 1980.

- Hyvarinen, L. Innovativeness and Its Indicators in Small and Medium-Sized Industrial Enterprises. International Small Business Journal, 1980, 9(1), 64–74 . [CrossRef]

- Lengnick-Hall, C. A.; Lengnick-Hall, M. L.; Abdinnour-Helm, S. The role of social and intellectual capital in achieving competitive advantage through enterprise resource planning (ERP) systems. Journal of Engineering and Technology Management, 2004, 21(4), 307-330. [CrossRef]

- Australian Manufacturing Council [AMC]. Leading the Way– A Study of Best Manufacturing Practices in Australia and New Zealand, Australian Manufacturing Council, Melbourne, 1994.

- Hunt, S. D.; Morgan, R. M. The comparative advantage theory of competition. Journal of marketing, 1995, 59(2), 1-15.

- Day, G. S.; Wensley, R. Assessing advantage: A framework for diagnosing competitive superiority. Journal of Marketing, 1988, 52, 1–20.

- Kamboj, S.; Rahman, Z. Market orientation, marketing capabilities and sustainable innovation: The mediating role of sustainable consumption and competitive advantage. Management Research Review, 2017, 40(6), 698-724.

- Martínez, P.; Rodríguez del Bosque, I. Sustainability dimensions: A source to enhance corporate reputation. Corporate Reputation Review, 2014, 17, 239-253.

- Ng, A. C.; Rezaee, Z. Business sustainability performance and cost of equity capital. Journal of Corporate Finance, 2015, 34, 128-149. [CrossRef]

- Yusoff, Y. M.; Omar, M. K.; Zaman, M. D. K.; Samad, S. Do all elements of green intellectual capital contribute toward business sustainability? Evidence from the Malaysian context using the Partial Least Squares method. Journal of Cleaner Production, 2019, 234, 626-637. [CrossRef]

- Dyllick, T.; Muff, K. Clarifying the meaning of sustainable business: Introducing a typology from business-as-usual to true business sustainability. Organization & Environment, 2016, 29(2), 156-174.

- Olaleye, B. R.; Abdurrashid, I.; Mustapha, B. Organizational sustainability and TQM practices in hospitality industry: employee-employer perception. The TQM Journal, 2024, 36(7), 1936-1960. [CrossRef]

- Olaleye, B. R.; B. O. Babatunde; J. N. Lekunze; A. R. Tella. Attaining Organizational Sustainability Through Competitive Intelligence: The Roles of Organizational Learning and Resilience. Journal of Intelligence Studies in Business, 2023, 13(3), 39-54.

- Jansen, J.J.; Vera, D.; Crossan, M. Strategic leadership for exploration and exploitation: the moderating role of environmental dynamism. The Leadership Quarterly, 2009, 20(1), 5-18. [CrossRef]

- Marta, S.; Leritz, L.E.; Mumford, M.D. Leadership skills and the group performance: situational demands, behavioral requirements, and planning. The Leadership Quarterly, 2005, 16(1), 97-120. [CrossRef]

- Yang, T.T.; Li, C.R. Competence exploration and exploitation in new product development: the moderating effects of environmental dynamism and competitiveness. Management Decision, 2011, 49(9), 1444-1470.

- Bolton, D.; Habib, M.; Landells, T. Resilience, Dynamism and Sustainable Development: Adaptive Organisational Capability Through Learning in Recurrent Crises", Seifi, S. and Crowther, D. (Ed.) Corporate Resilience. Developments in Corporate Governance and Responsibility, 2023, 21,3-32. [CrossRef]

- Curatolo, M. B. Resilience as a Sustainability Strategy for Businesses in the Post-Covid Era. Sustainability a way forward. Surender Mor, Bloomsbury Publishing India Pvt. Ltd. 2022, 34-40.

- Yong, J.Y.; Yusliza, M.Y.; Ramayah, T.; Chiappetta Jabbour, C.J.; Sehnem, S.; Mani, V. Pathways towards sustainability in manufacturing organizations: Empirical evidence on the role of green human resource management. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2020, 29, 212–228. [CrossRef]

- Tekala, K.; Baradarani, S.; Alzubi, A.; Berberoğlu, A. Green Entrepreneurship for Business Sustainability: Do Environmental Dynamism and Green Structural Capital Matter? Sustainability, 2024, 16(13), 5291. [CrossRef]

- Robledo, V.; López, C.; Zapata, W.; Pérez, J. Desarrollo de una Metodología de evaluación de capacidades de innovación. Revista Perfil de Coyuntura Económica, 2010, 15, 133–148.

- Jansen, J.J.; Van Den Bosch, F.; Volberda, H.W. Exploratory innovation, exploitative innovation, and performance: effects of organizational antecedents and environmental moderators. Management Science, 2006, 52(11), 1661-1674. [CrossRef]

- Rahmat, M. W. Revealing the power play: Unraveling the dynamic environment's influence on intangible resources and sustainable competitive advantage. Jurnal Siasat Bisnis, 2024.

- Zulfiqar, A.; Hongyi, S.; Murad, A. The impact of managerial and adaptive capabilities to stimulate organizational innovation in SMEs: A complementary PLS–SEM approach. Sustainability, 2017, 9, 1-23.

- Gunasekaran, A.; Rai, B. K.; Griffin, M. Resilience and competitiveness of small and medium size enterprises: An empirical research. International Journal of Production Research, 2011, 49(18), 5489-5509. [CrossRef]

- Ates, A.; Bititci, U. Change Process: A key enabler for building resilient SMEs. International Journal of Production Research, 2011, 49, 5601-5648. [CrossRef]

- Tabachnick, B. G.; Fidell, L. S.; Ullman, J. B. Using multivariate statistics, 2013, 6, 497-516. Boston, MA: Pearson.

- Podsakoff, P. M.; MacKenzie, S. B.; Lee, J. Y.; Podsakoff, N. P. Common method biases in behavioral research: a critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 2003, 88(5), 879. [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM), 2nd ed., Sage, Thousand Oaks, CA. 2017.

- Dijkstra, T.K.; Henseler, J. Consistent partial least squares path modeling. MIS Quarterly, 2015, 39(2), 297-316. [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 2015, 43(1) 115-135. [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error: Algebra and statistics. Journal of Marketing Research, 1981, 18, 382-388.

- Kline, R.B. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling, 2nd ed., Guilford Press, New York, 2005.

- Sullivan, G.M.; Feinn, R. Using effect size-or why the P-value is not enough. Journal of Graduate Medical Education, 2012, 4(3), 279-282.

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Hillsdale, MI., 1988.

- Eggert, A.; Thiesbrummel, C.; Deutscher, C. Differential effects of product and service innovations on the financial performance of industrial firms. Journal of Business Market Management, 2014, 7(3), 380-405.

- Kim, J. H.; Lennon, S. J. Descriptive content analysis on e-service research. International Journal of Service Science, Management, Engineering, and Technology (IJSSMET), 2017, 8(1), 18-31. [CrossRef]

- Hallstedt, S.I., Thompson, A.W. and Lindahl, P. (2013), “Key elements for implementing a strategic sustainability perspective in the product innovation process”, Journal of Cleaner Production, Elsevier Ltd, Vol. 51, pp. 277–288. [CrossRef]

- Teguh, S.; Hartiwi, P.; Ridho, B. I.; Bachtiar, S. H.; Synthia, A. S.; Noor, H. A. Innovation capability and sustainable competitive advantage: An entrepreneurial marketing perspective. The Journal of Asian Finance, Economics and Business, 2021, 8(5), 127-134.

- Akhisar, İ.; Tunay, K. B.; Tunay, N. The effects of innovations on bank performance: The case of electronic banking services. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 2015, 195, 369–375. [CrossRef]

- Galli, B. J. (2019). Reflection of literature on using lean innovation models for start-up ventures. The Journal of Modern Project Management, 7(2).

- Lee, J. S.; Hsieh, C. J. A research in relating entrepreneurship, marketing capability, innovative capability and sustained competitive advantage. Journal of Business & Economics Research, 2010, 8(9), 109. [CrossRef]

- Anning-Dorson, T. Innovation and competitive advantage creation: The role of organisational leadership in service firms from emerging markets. Int. Mark. Rev. 2018, 35, 580–600.

- Nasifoglu Elidemir, S.; Ozturen, A.; Bayighomog, S. W. Innovative behaviors, employee creativity, and sustainable competitive advantage: A moderated mediation. Sustainability, 2020, 12(8), 3295. [CrossRef]

- Sulistyo, H.; Ayuni, S. Competitive advantages of SMEs: The roles of innovation capability, entrepreneurial orientation, and social capital. Contaduría y administración, 2020, 65(1). [CrossRef]

- Higón, D. A. The impact of ICT on innovation activities: Evidence for UK SMEs. International Small Business Journal, 2012, 30(6), 684-699.

- Chatzoglou, P.; Chatzoudes, D. The role of innovation in building competitive advantages: An empirical investigation. Eur. J. Innov. Manag. 2018, 21, 44–69. [CrossRef]

- Baker, E.W.; Al-Gahtani, S.S.; Hubona, G.S. The effects of gender and age on new technology implementation in a developing country: Testing the theory of planned behavior (TPB). Inf. Technol. People 2007, 20, 352–375.

- Porter, M.E. Competitive Advantage: Creating and Sustaining Superior Performance; Simon and Schuster: New York, NY, USA, 2008.

- Porter, M.E. Competitive Advantage: Creating and Sustaining Superior Performance; FreePress: New York, NY, USA, 1985; 43, 214.

- Haseeb, M.; Hussain, H. I.; Kot, S.; Androniceanu, A.; Jermsittiparsert, K. Role of social and technological challenges in achieving a sustainable competitive advantage and sustainable business performance. Sustainability, 2019, 11(14), 3811. [CrossRef]

- Yu, D.; Tao, S.; Hanan, A.; Ong, T. S.; Latif, B.; Ali, M. Fostering green innovation adoption through green dynamic capability: The moderating role of environmental dynamism and big data analytic capability. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 2022, 19(16), 10336. [CrossRef]

- Simerly, R.L.; Li, M. Environmental dynamism, capital structure and performance: A theoretical integration and an empirical test. Strateg. Manag. J. 2000, 21, 31–49.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).