Submitted:

18 September 2024

Posted:

19 September 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Population

2.2. Measurement of d-ROMs and BAP Levels

2.3. Assessment of d-ROM and BAP Levels

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Patient Characteristics

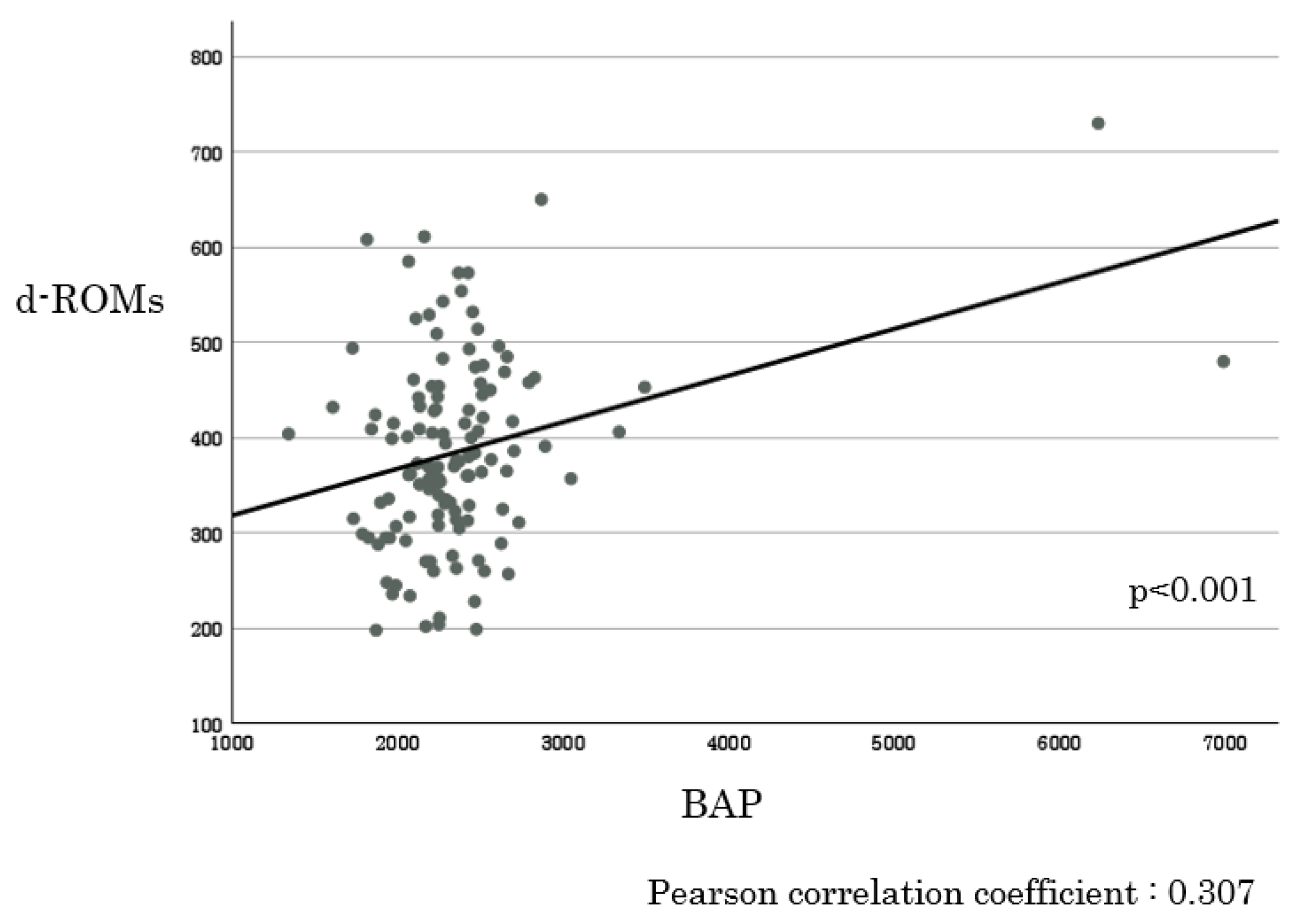

3.2. Comparison of Preoperative d-ROM and BAP Levels with Clinicopathological Factors in Patients with CRC

3.3. Comparison of Postoperative d-ROM and BAP Levels with Clinicopathological Factors in Patients with CRC

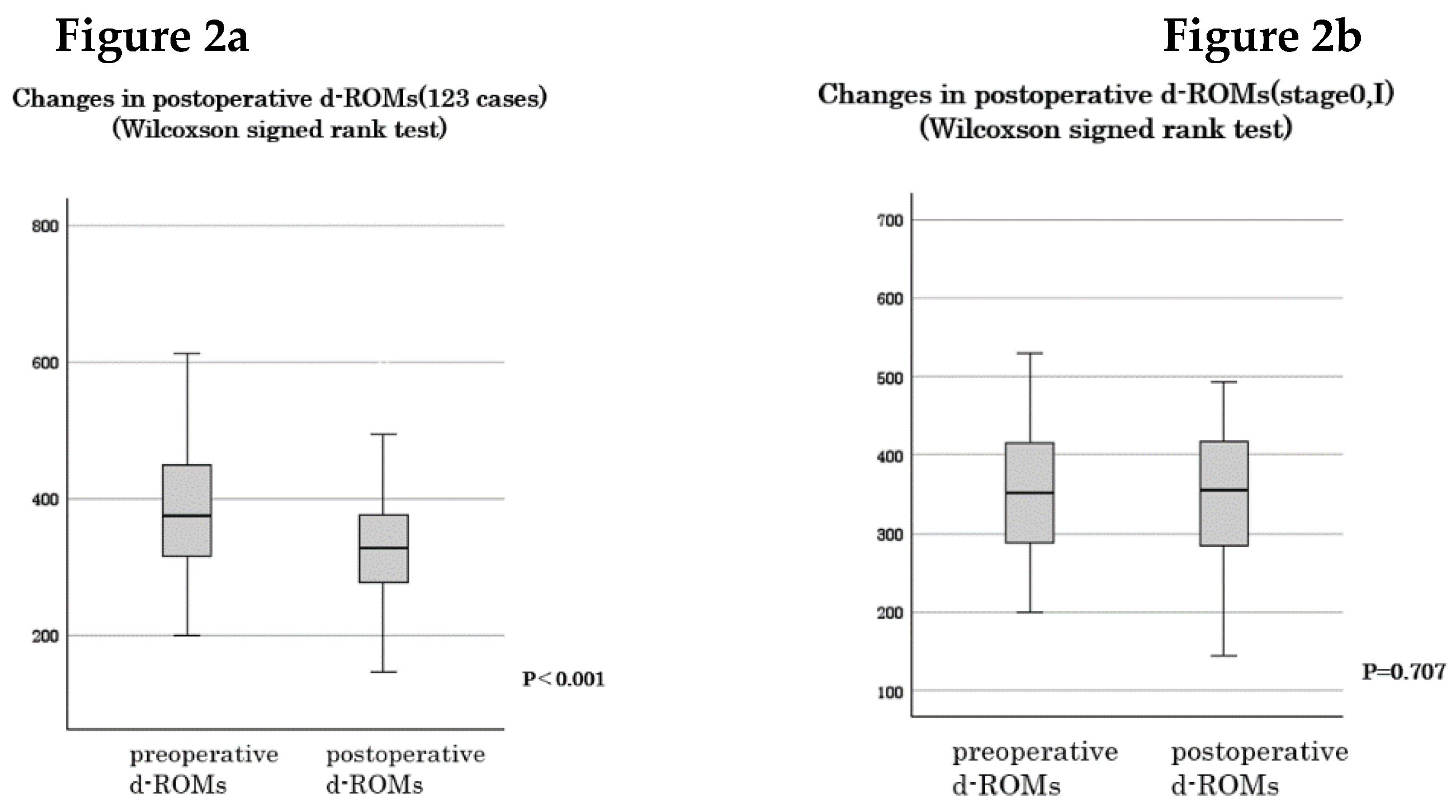

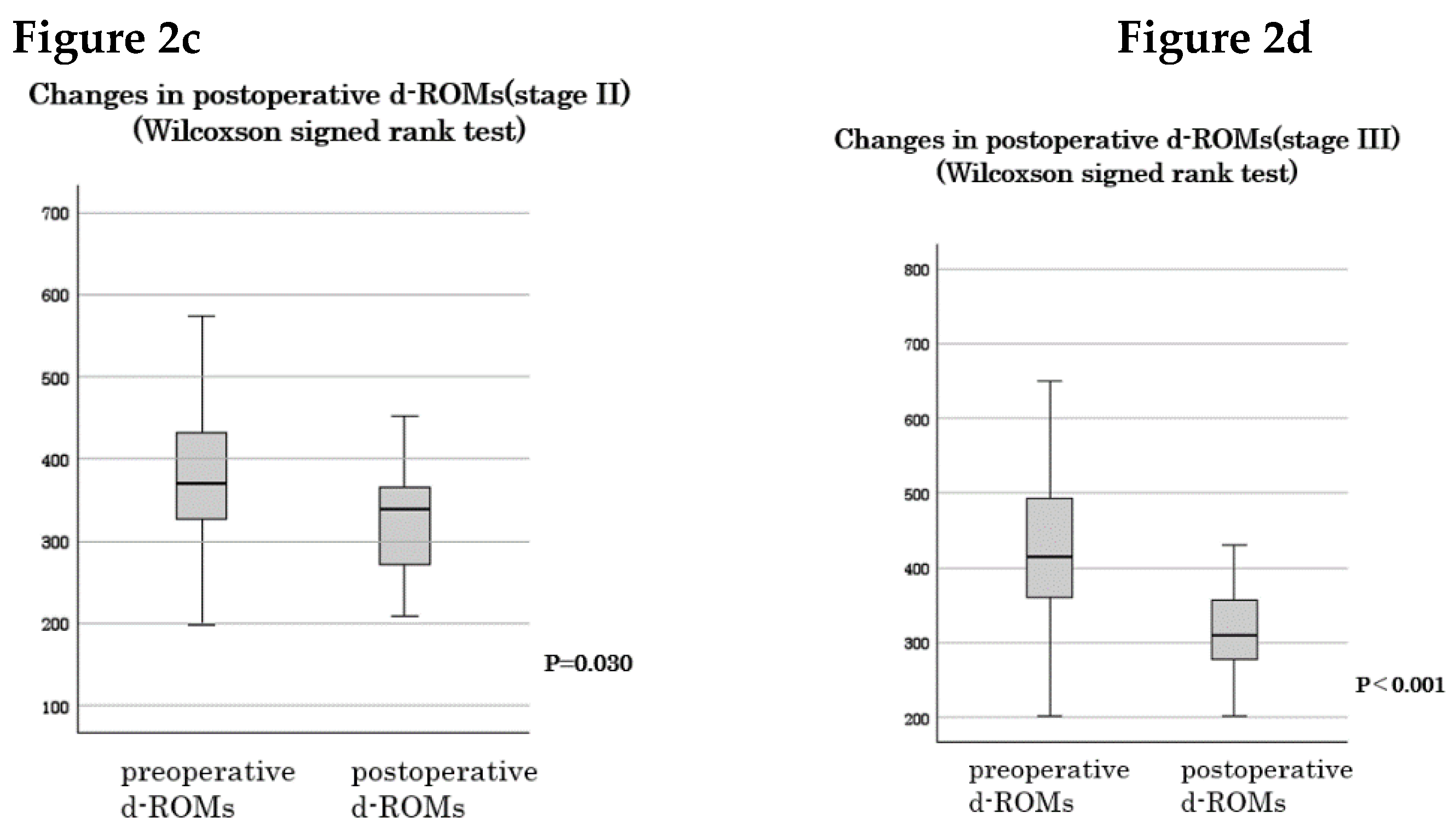

3.4. Changes in d-ROM and BAP Levels Following Resection

3.5. Comparison of Preoperative d-ROM and BAP Ratios with Clinicopathological Factors in Patients with CRC

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Morgan, E.; Arnold, M.; Gini, A.; Lorenzoni, V.; Cabasag, C.J.; Laversanne, M.; Vignat, J.; Ferlay, J.; Murphy, N.; Bray, F. Global burden of colorectal cancer in 2020 and 2040: incidence and mortality estimates from GLOBOCAN. Gut 2023, 72, 338–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hashiguchi, Y.; Muro, K.; Saito, Y.; Ito, Y.; Ajioka, Y.; Hamaguchi, T.; Hasegawa, K.; Hotta, K.; Ishida, H.; Ishiguro, M.; Ishihara, S.; Kanemitsu, Y.; Kinugasa, Y.; Murofushi, K.; Nakajima, T.E.; Oka, S.; Tanaka, T.; Taniguchi, H.; Tsuji, A.; Uehara, K.; Ueno, H.; Yamanaka, T.; Yamazaki, K.; Yoshida, M.; Yoshino, T.; Itabashi, M.; Sakamaki, K.; Sano, K.; Shimada, Y.; Tanaka, S.; Uetake, H.; Yamaguchi, S.; Yamaguchi, N.; Kobayashi, H.; Matsuda, K.; Kotake, K.; Sugihara, K.; Japanese Society for Cancer of the Colon and Rectum. Japanese Society for Cancer of the Colon and Rectum (JSCCR) guidelines 2019 for the treatment of colorectal cancer. Int. J. Clin. Oncol. 2020, 25, 1–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vona, R.; Pallotta, L.; Cappelletti, M.; Severi, C.; Matarrese, P. The impact of oxidative stress in human pathology: focus on gastrointestinal disorders. Antioxidants (Basel) 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juan, C.A.; Pérez de la Lastra, J.M.; Plou, F.J.; Pérez-Lebeña, E. The chemistry of reactive oxygen species (ros) revisited: outlining their role in biological macromolecules (DNA, lipids and proteins) and induced pathologies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carini, F.; Mazzola, M.; Rappa, F.; Jurjus, A.; Geagea, A.G.; Al Kattar, S.; Bou-Assi, T.; Jurjus, R.; Damiani, P.; Leone, A.; Tomasello, G. Colorectal carcinogenesis: role of oxidative stress and antioxidants. Anticancer Res. 2017, 37, 4759–4766. [Google Scholar]

- Bardelcíková, A.; Šoltys, J.; Mojžiš, J. Oxidative stress, inflammation and colorectal cancer: an overview. Antioxidants (Basel) 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perše, M. Oxidative stress in the pathogenesis of colorectal cancer: cause or consequence? BioMed Res. Int. 2013, 2013, 725710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, M.; Jeong, S.; Park, S.; Nam, S.; Chung, J.W.; Kim, K.O.; An, J.; Kim, J.H. Significance of 8-OHdG Expression as a Predictor of Survival in Colorectal Cancer. Cancers 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawai, K.; Goi, T.; Kimura, Y.; Koneri, K. Monitoring metastatic colorectal cancer progression according to reactive oxygen metabolite derivative levels. Cancers 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delimaris, I.; Faviou, E.; Antonakos, G.; Stathopoulou, E.; Zachari, A.; Dionyssiou-Asteriou, A. Oxidized ldl, serum oxidizability and serum lipid levels in patients with breast or ovarian cancer. Clin. Biochem. 2007, 40, 1129–1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zabirnyk, O.; Liu, W.; Khalil, S.; Sharma, A.; Phang, J.M. Oxidized low-density lipoproteins upregulate proline oxidase to initiate ros-dependent autophagy. Carcinogenesis 2010, 31, 446–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crespo-Sanjuán, J.; Calvo-Nieves, M.D.; Aguirre-Gervás, B.; Herreros-Rodríguez, J.; Velayos-Jiménez, B.; Castro-Alija, M.J.; Muñoz-Moreno, M.F.; Sánchez, D.; Zamora-González, N.; Bajo-Grañeras, R.; García-Centeno, R.M.; Largo Cabrerizo, M.E.; Bustamante, M.R.; Garrote-Adrados, J.A. Early detection of high oxidative activity in patients with adenomatous intestinal polyps and colorectal adenocarcinoma: myeloperoxidase and oxidized low-density lipoprotein in serum as new markers of oxidative stress in colorectal cancer. Lab. Med. 2015, 46, 123–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zettler, M.E.; Prociuk, M.A.; Austria, J.A.; Massaeli, H.; Zhong, G.M.; Pierce, G.N. Oxldl stimulates cell proliferation through a general induction of cell cycle proteins. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2003, 284, H644–H653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bitorina, A.V.; Oligschlaeger, Y.; Shiri-Sverdlov, R.; Theys, J. Low profile high value target: the role of oxLDL in cancer. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Cell Biol. Lipids 2019, 1864, 158518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inokuma, T.; Haraguchi, M.; Fujita, F.; Tajima, Y.; Kanematsu, T. Oxidative stress and tumor progression in colorectal cancer. Hepato-Gastroenterology 2009, 56, 343–347. [Google Scholar]

- Inokuma, T.; Haraguchi, M.; Fujita, F.; Torashima, Y.; Eguchi, S.; Kanematsu, T. Suppression of reactive oxygen species develops lymph node metastasis in colorectal cancer. Hepato-Gastroenterology 2012, 59, 2480–2483. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, R.; Feng, J.F.; Yang, Y.W.; Dai, C.M.; Lu, A.Y.; Li, J.; Liao, Y.; Xiang, M.; Huang, Q.M.; Wang, D.; Du, X.B. Significance of serum total oxidant/antioxidant status in patients with colorectal cancer. PLOS ONE 2017, 12, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Afanas’ev, I. Reactive oxygen species signaling in cancer: comparison with aging. Aging Dis. 2011, 2, 219–230. [Google Scholar]

- Rodic, S.; Vincent, M.D. Reactive oxygen species (ros) are a key determinant of cancer’s metabolic phenotype. Int. J. Cancer 2018, 142, 440–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, S.H.; Ammori, B.J.; Holmfield, J.; Larvin, M.; McMahon, M.J. Intestinal hypoperfusion contributes to gut barrier failure in severe acute pancreatitis. J. Gastrointest. Surg. 2003, 7, 26–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.Y.; Wu, M.L.; Wang, J.; Sui, Y.L.; Liu, S.L.; Shi, D.Y. Nac selectively inhibit cancer telomerase activity: A higher redox homeostasis threshold exists in cancer cells. Redox Biol. 2016, 8, 91–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Floyd, R.A. The role of 8-hydroxyguanine in carcinogenesis. Carcinogenesis 1990, 11, 1447–1450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, S.P.; Aguilar, F.; Amstad, P.; Cerutti, P. Oxy-radical induced mutagenesis of hotspot codons 248 and 249 of the human p53 gene. Oncogene 1994, 9, 2277–2281. [Google Scholar]

- Collado, R.; Oliver, I.; Tormos, C.; Egea, M.; Miguel, A.; Cerdá, C.; Ivars, D.; Borrego, S.; Carbonell, F.; Sáez, G.T. Early ros-mediated DNA damage and oxidative stress biomarkers in monoclonal B lymphocytosis. Cancer Lett. 2012, 317, 144–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelicano, H.; Carney, D.; Huang, P. Ros stress in cancer cells and therapeutic implications. Drug Resist. Update. 2004, 7, 97–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiang, F.F.; Chao, T.H.; Huang, S.C.; Cheng, C.H.; Tseng, Y.Y.; Huang, Y.C. Cysteine regulates oxidative stress and glutathione-related antioxidative capacity before and after colorectal tumor resection. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strzelczyk, J.K.; Wielkoszyński, T.; Krakowczyk, Ł.; Adamek, B.; Zalewska-Ziob, M.; Gawron, K.; Kasperczyk, J.; Wiczkowski, A. The activity of antioxidant enzymes in colorectal adenocarcinoma and corresponding normal mucosa. Acta Biochim. Pol. 2012, 59, 549–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ozdemirler, G.; Pabuççuoglu, H.; Bulut, T.; Bugra, D.; Uysal, M.; Toker, G. Increased lipoperoxide levels and antioxidant system in colorectal cancer. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 1998, 124, 555–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skrzydlewska, E.; Sulkowski, S.; Koda, M.; Zalewski, B.; Kanczuga-Koda, L.; Sulkowska, M. Lipid peroxidation and antioxidant status in colorectal cancer. World J. Gastroenterol. 2005, 11, 403–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rainis, T.; Maor, I.; Lanir, A.; Shnizer, S.; Lavy, A. Enhanced oxidative stress and leucocyte activation in neoplastic tissues of the colon. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2007, 52, 526–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kekec, Y.; Paydas, S.; Tuli, A.; Zorludemir, S.; Sakman, G.; Seydaoglu, G. Antioxidant enzyme levels in cases with gastrointesinal cancer. Eur. J. Intern. Med. 2009, 20, 403–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Demple, B.; Harrison, L. Repair of oxidative damage to DNA: enzymology and biology. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 1994, 63, 915–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bansal, A.; Simon, M.C. Glutathione metabolism in cancer progression and treatment resistance. J. Cell Biol. 2018, 217, 2291–2298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugimoto, K.; Sakamoto, K.; Kawai, M.; Kawano, S.; Munakata, S.; Ishiyama, S.; Takahashi, M.; Kojima, Y.; Tomiki, Y. Serum oxidative stress is an independent prognostic marker in colorectal cancer. Transl. Cancer Res. 2019, 8, 1699–1708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilk, K.; Meitern, R.; Härmson, O.; Soomets, U.; Hõrak, P. Assessment of oxidative stress in serum by d-roms test. Free Radic. Res. 2014, 48, 883–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sawai, K.; Goi, T.; Sakamoto, S.; Matsunaka, T.; Maegawa, N.; Koneri, K. Oxidative stress as a biomarker for predicting the prognosis of patients with colorectal cancer. Oncology 2022, 100, 612–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trotti, R.; Carratelli, M.; Barbieri, M. Performance and clinical application of a new, fast method for the detection of hydroperoxides in serum. Panminerva Med. 2002, 44, 37–40. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Strzelczyk, J.K.; Wielkoszyński, T.; Krakowczyk, Ł.; Adamek, B.; Zalewska-Ziob, M.; Gawron, K.; Kasperczyk, J.; Wiczkowski, A. The activity of antioxidant enzymes in colorectal adenocarcinoma and corresponding normal mucosa. Acta Biochim. Pol. 2012, 59, 549–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kekec, Y.; Paydas, S.; Tuli, A.; Zorludemir, S.; Sakman, G.; Seydaoglu, G. Antioxidant enzyme levels in cases with gastrointesinal cancer. Eur. J. Intern. Med. 2009, 20, 403–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salehi, S.S.; Mirmiranpour, H.; Rabizadeh, S.; Esteghamati, A.; Tomasello, G.; Alibakhshi, A.; Najafi, N.; Rajab, A.; Nakhjavani, M. Improvement in redox homeostasis after cytoreductive surgery in colorectal adenocarcinoma. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2021, 2021, 8864905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acevedo-León, D.; Gómez-Abril, S.Á.; Sanz-García, P.; Estañ-Capell, N.; Bañuls, C.; Sáez, G. The role of oxidative stress, tumor and inflammatory markers in colorectal cancer patients: A one-year follow-up study. Redox Biol. 2023, 62, 102662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yücel, A.F.; Kemik, O.; Kemik, A.S.; Purisa, S.; Tüzün, I.S. Relationship between the levels of oxidative stress in mesenteric and peripheral serum and clinicopathological variables in colorectal cancer. Balk. Med. J. 2012, 29, 144–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hendrickse, C.W.; Kelly, R.W.; Radley, S.; Donovan, I.A.; Keighley, M.R.; Neoptolemos, J.P. Lipid peroxidation and prostaglandins in colorectal cancer. Br. J. Surg. 1994, 81, 1219–1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skrzydewska, E.; Stankiewicz, A.; Michalak, K.; Sulkowska, M.; Zalewski, B.; Piotrowski, Z. Antioxidant status and proteolytic-antiproteolytic balance in colorectal cancer. Folia Histochem. Cytobiol. 2001, 39 (Suppl. 2), 98–99. [Google Scholar]

- Acevedo-León, D.; Monzó-Beltrán, L.; Gómez-Abril, S.Á.; Estañ-Capell, N.; Camarasa-Lillo, N.; Pérez-Ebri, M.L.; Escandón-Álvarez, J.; Alonso-Iglesias, E.; Santaolaria-Ayora, M.L.; Carbonell-Moncho, A.; Ventura-Gayete, J.; Pla, L.; Martínez-Bisbal, M.C.; Martínez-Máñez, R.; Bagán-Debón, L.; Viña-Almunia, A.; Martínez-Santamaría, M.A.; Ruiz-Luque, M.; Alonso-Fernández, J.; Bañuls, C.; Sáez, G. The effectiveness of glutathione redox status as a possible tumor marker in colorectal cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hristozov, D.; Gadjeva, V.; Vlaykova, T.; Dimitrov, G. Evaluation of oxidative stress in patients with cancer. Arch. Physiol. Biochem. 2001, 109, 331–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okur, H.K.; Yuksel, M.; Lacin, T.; Baysungur, V.; Okur, E. Detection of reactive oxygen metabolites in malignant and adjacent normal tissues of patients with lung cancer. World J. Surg. Oncol. 2013, 11, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colon Cancer Laparoscopic or Open Resection Study Group. Buunen, M.; Veldkamp, R.; Hop, W.C.J.; Kuhry, E.; Jeekel, J.; Haglind, E.; Påhlman, L.; Cuesta, M.A.; Msika, S.; Morino, M.; Lacy, A.; Bonjer, H.J. Survival after laparoscopic surgery versus open surgery for colon cancer: long-term outcome of a randomised clinical trial. Lancet Oncol. 2009, 10, 44–52. [Google Scholar]

| Independent variables | d-ROM | BAP | |||

| N | Median (IQR) | p-value | Median (IQR) | p-value | |

| Age (years) | 0.428 | 0.897 | |||

| <70 | 54 | 376.0 (311.5, 476.8) | 2269.5 (2109.3, 2444.8) | ||

| ≥70 | 69 | 370.0 (319.0, 430.0) | 2255.0 (2128.0, 2481.0) | ||

| Sex | 0.478 | 0.933 | |||

| Male | 66 | 361.0 (314.3, 439.8) | 2275.0 (2128.3, 2463.5) | ||

| Female | 57 | 391.0 (319.0, 453.0) | 2245.0 (2107.0, 2481.0) | ||

| Location | 0.063 | 0.613 | |||

| Right | 19 | 401.5 (349.0, 457.3) | 2302.5 (2073.3, 2486.8) | ||

| Left | 104 | 365.0 (306.0, 429.0) | 2249.0 (2125.5, 2456.0) | ||

| Tumor size (mm) | <0.001 | 0.928 | |||

| <45 | 75 | 357.0 (293.5, 406.0) | 2246.0 (2143.5, 2477.5) | ||

| ≥45 | 48 | 426.0 (359.3, 493.3) | 2275.5 (2085.8, 2454.0) | ||

| Tumor invasion depth | <0.001 | 0.281 | |||

| T1, T2 | 42 | 352.5 (289.8, 426.0) | 2318.5 (2138.5, 2516.8) | ||

| T3, T4 | 81 | 400.0 (332.0, 457.0) | 2249.0 (2107.0, 2429.0) | ||

| Lymph node metastasis | 0.004 | 0.674 | |||

| No | 81 | 361.0 (306.0, 416.0) | 2286.0 (2128.5, 2476.5) | ||

| Yes | 42 | 422.5 (359.3, 493.3) | 2240.5 (2086.8, 2454.0) | ||

| Stage | 0.005 | 0.398 | |||

| 0-I | 41 | 351.0 (289.0, 415.0) | 2351.0 (2129.0, 2504.0) | ||

| II-III | 82 | 400.5 (332.8, 470.8) | 2252.0 (2109.3, 2477.8) |

| Independent variables |

Multivariate linear regression analysis | ||

| β | eβ (95%CI) | p-value | |

| Age | 1.57 e-3 | 0.998 (-5.58e-3, 2.42e-3) | 0.436 |

| Sex (men vs. female) | 3.13 e-2 | 1.032 (-6.15e-2, 1.24e-1) | 0.505 |

| Location (left vs. right) | 4.34 e-2 | 0.958 (-1.42e-1, 5.52e-2) | 0.385 |

| Tumor size | 4.77 e-3 | 1.005 (1.87e-3, 7.68e-3) | < 0.001 |

| Serosa invasion (no vs. yes) | -1.67 e-2 | 0.983 (-1.35e-1, 1.010e-1) | 0.778 |

| Lymph node metastasis (no vs. yes) | 6.54 e-2 | 1.068 (-4.15e-2 ~1.72e-1) | 0.436 |

| Independent variables |

Multivariate linear regression analysis | ||

| β | 95%CI | p-value | |

| Age | -3.071 | -13.404, 7.262 | 0.557 |

| Sex (men vs. female) | -157.11 | -396.781, 82.551 | 0.197 |

| Location (left vs. right) | -232.823 | -487.596, 21.949 | 0.072 |

| Tumor size | -0.146 | -7.644, 7.353 | 0.969 |

| Serosa invasion (no vs. yes) | 6.101 | -298.201, 310.404 | 0.968 |

| Lymph node metastasis (no vs. yes) | -48.655 | -324.804, 227.495 | 0.728 |

| Independent variables | d-ROM ratio | BAP ratio | ||||

| case | Median (IQR) | p-value | Median (IQR) | p-value | ||

| Age (years) | 0.123 | 0.697 | ||||

| <70 | 54 | 0.831 (0.708, 0.986) | 1.034 (0.903, 1.137) | |||

| ≥70 | 69 | 0.924 (0.765, 1.072) | 1.007 (0.932, 1.148) | |||

| Sex | 0.018 | 0.982 | ||||

| Male | 66 | 0.828 (0.682, 0.828) | 1.007 (0.914, 1.138) | |||

| Female | 57 | 0.941 (0.781, 1.079) | 1.008 (0.923, 1.148) | |||

| Location | 0.242 | 0.766 | ||||

| Right | 19 | 0.870 (0.741, 1.020) | 1.017 (0.946, 1.164) | |||

| Left | 104 | 0.896 (0.735, 1.103) | 1.008 (0.907, 1.137) | |||

| Tumor size (cm) | <0.001 | 0.754 | ||||

| <45 | 75 | 0.978 (0.804, 1.107) | 1.008 (0.917, 1.154) | |||

| ≥45 | 48 | 0.777 (0.687, 0.891) | 1.006 (0.919, 1.112) | |||

| Tumor invasion depth | <0.001 | 0.599 | ||||

| T1, T2 | 42 | 1.037 (0.839, 1.110) | 0.981 (0.905, 1.133) | |||

| T3, T4 | 81 | 0.832 (0.711, 0.970) | 1.035 (0.924, 1.140) | |||

| Lymph node metastasis | <0.001 | 0.369 | ||||

| No | 81 | 0.978 (0.786, 1.107) | 0.990 (0.904, 1.135) | |||

| Yes | 42 | 0.769 (0.685, 0.897) | 1.042 (0.938, 1.153) | |||

| Stage | 0.005 | 0.241 | ||||

| 0-I | 41 | 1.046 (0.883, 1.111) | 0.970 (0.901, 1.111) | |||

| II-III | 82 | 0.829 (0.708, 0.967) | 1.044 (0.926, 1.146) |

| Independent variables |

Multivariate linear regression analysis | ||

| β | eβ (95%CI) | p-value | |

| Age | 2.68 e-3 | 1.003 (-1.42e-3, 6.79e-3) | 0.198 |

| Sex (men vs. female) | 1.27e-1 | 1.135 (3.18e-2, 2.22e-1) | 0.009 |

| Location (left vs. right) | 7.58 e-2 | 1.079 (-2.53e-2, 1.77e-1) | 0.140 |

| Tumor size | -3.57 e-3 | 0.996 (-6.551e-3, -5.963e-3) | 0.019 |

| Serosa invasion (no vs. yes) | -2.86 e-2 | 0.972 (-1.49e-1, 9.22e-2) | 0.640 |

| Lymph node metastasis (no vs. yes) | -1.13e-1 | 0.893 (-0.223, -0.003) | 0.044 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).