Submitted:

19 September 2024

Posted:

19 September 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Background

1.2. Literature Review

1.3. Purpose of the Study and Research Method

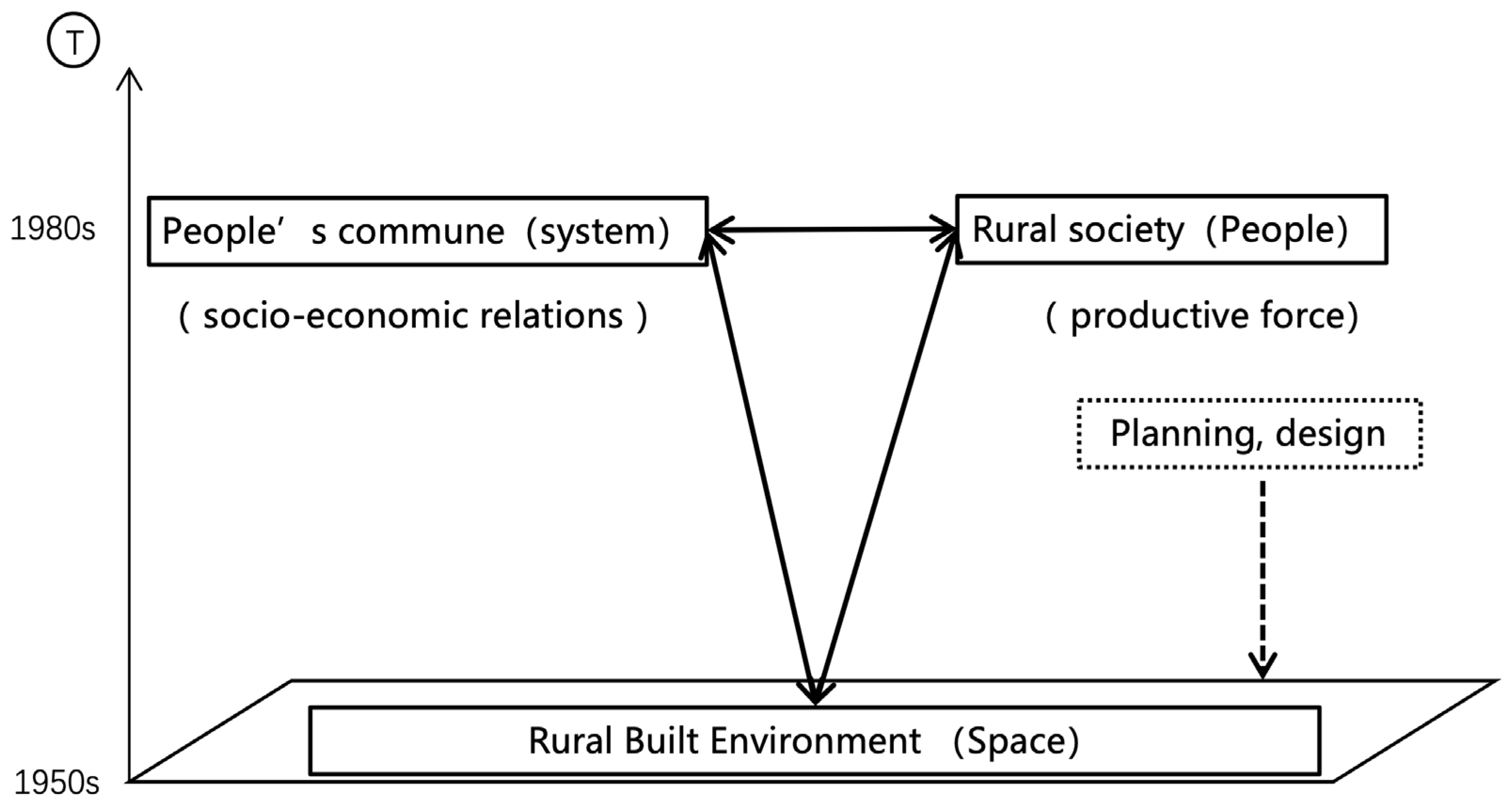

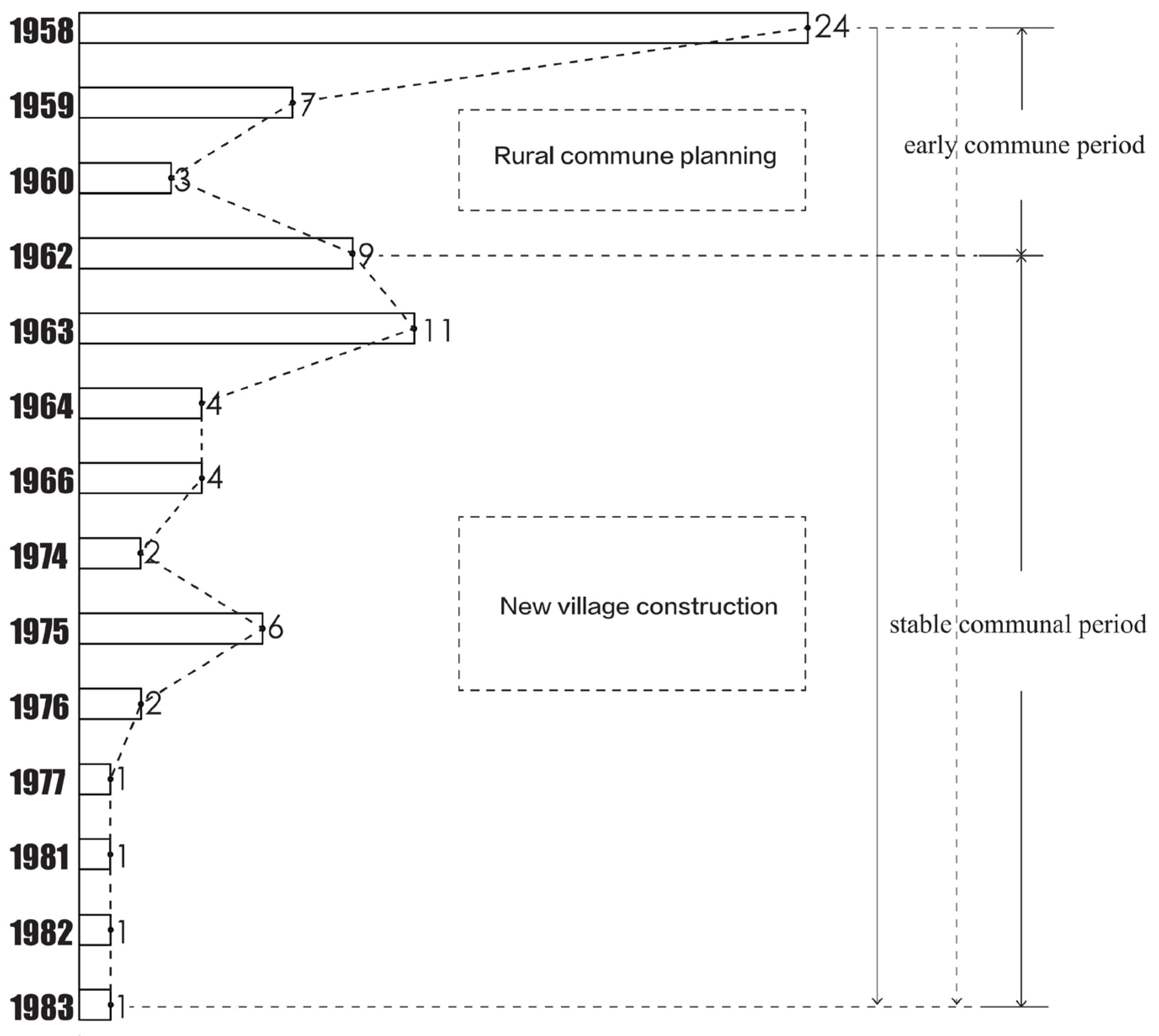

2. The General Strategies of Rural Housing Design of People’s Commune

2.1. The Characteristics of Chinese Rural Lifestyle under the People’s Commune System

2.2. The General Strategies of Rural Housing Design

- (a)

- Except for No.4, No.11, No.14, and No.16, the other commune housings had no kitchen in each household; they relied on the public canteen.

- (b)

- Compared with the traditional bungalow, the two-story house were thought to be the ideal proposal to solve the contradiction between population concentration and limited economic condition.

- (c)

- The living space per rural resident was specified and was no more than 10 m2.

- (d)

- Except for No.10 and No.15, public residence plans were almost entirely linear shaped, which was easier to extend in the ground and had the advantage of easy construction. (Figure 4)

- (e)

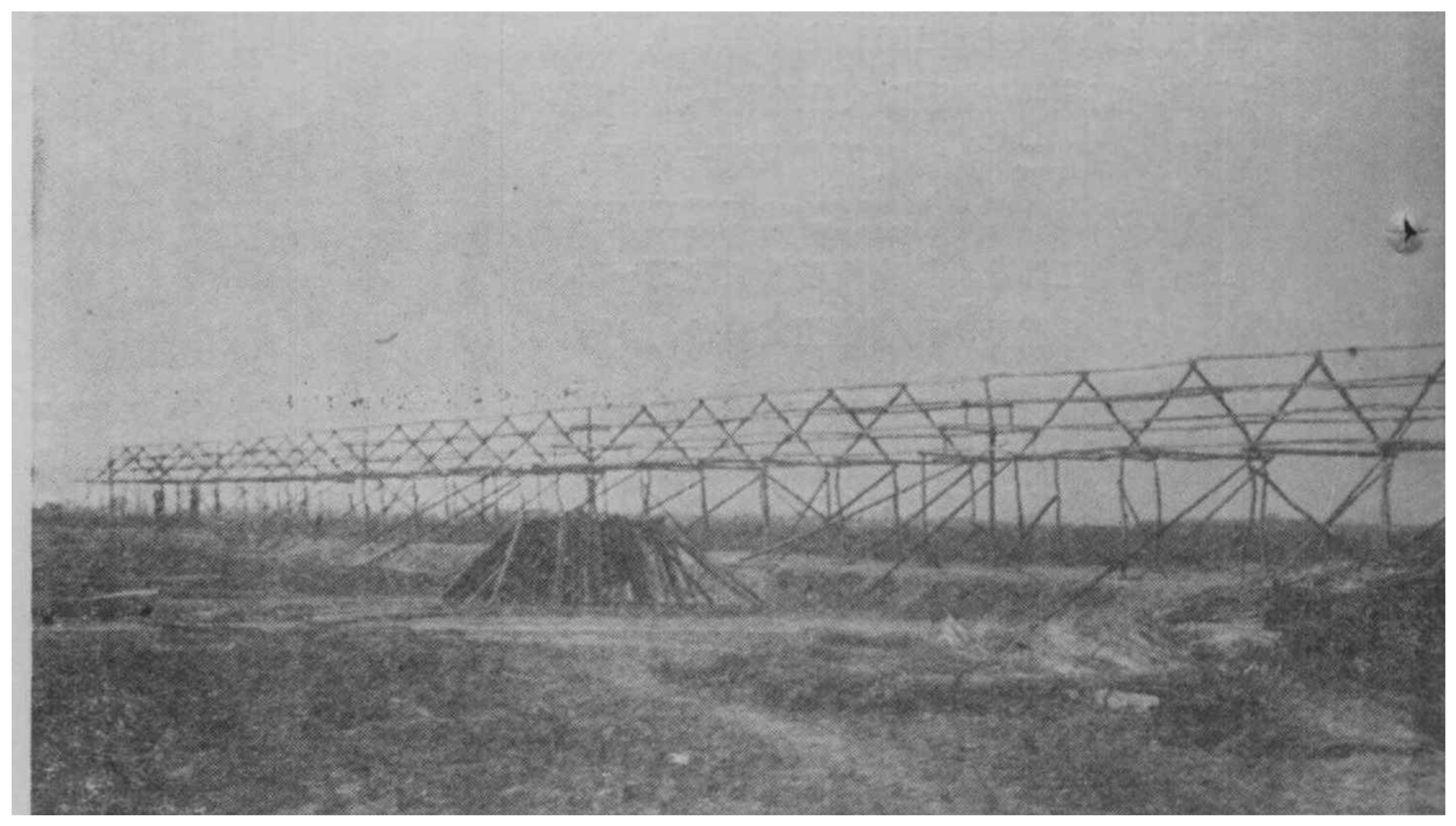

- In terms of building structure and materials, most of the commune housing adopted the simple method with cheap, local materials such as brick, wood and mud to build, which was the result of the lower economic conditions at that time.

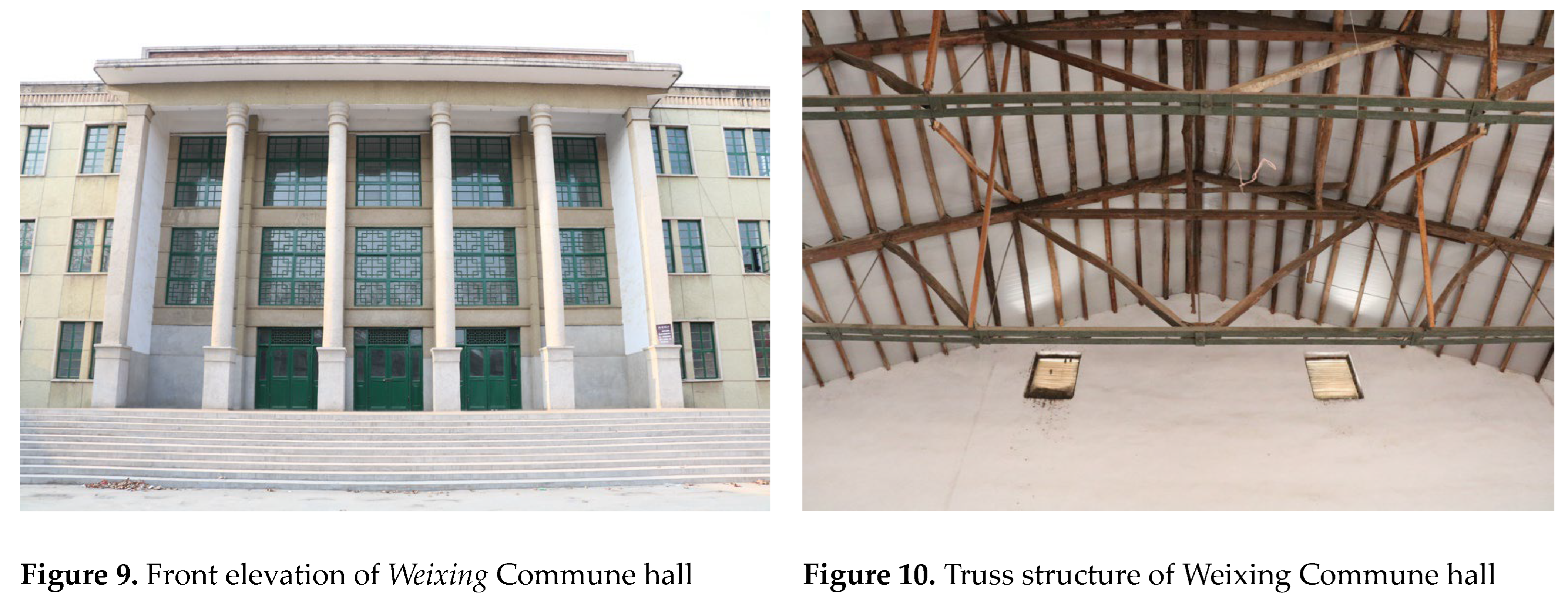

3. The Investigation of Existing Local Houses of the Weixing Commune

3.1. Vernacular House of Qianwan Village

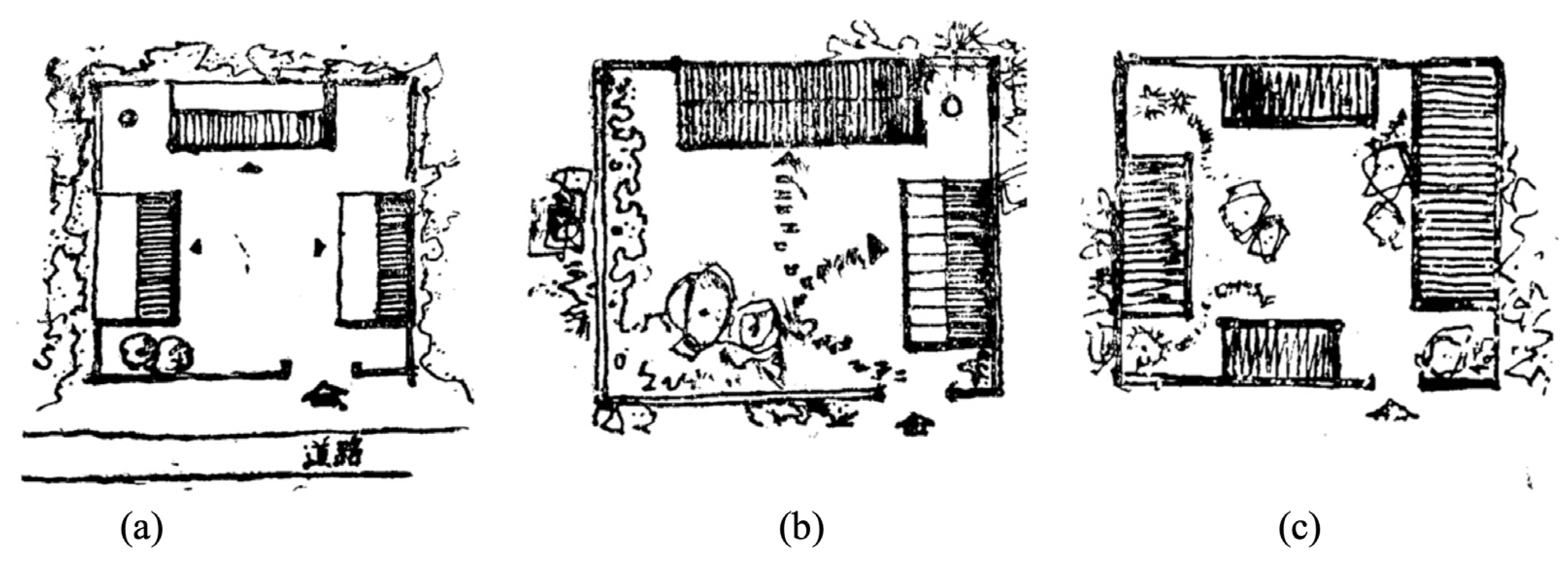

- Layout and space composition: As Figure 5 illustrates, there are three types of houses in Qianwan village. They are all courtyard houses with a garden in the center surrounded by independent rooms. There is a fence around the houses. This design was the result of top-down patriarchy under feudal society, as concluded by SCIT.

- Location of entrance: Among the houses above, almost all the entrances are located at the east of the central garden, deviated from the central axis. This can effectively prevent dust from being blown into rooms by strong wind, wrote by SCIT.

- A pigsty, chicken coop, and toilet were set in one corner of the courtyard.

- The yard was generally used as a place for washing and drying clothes, and also a place for raising poultry and people to have a rest.

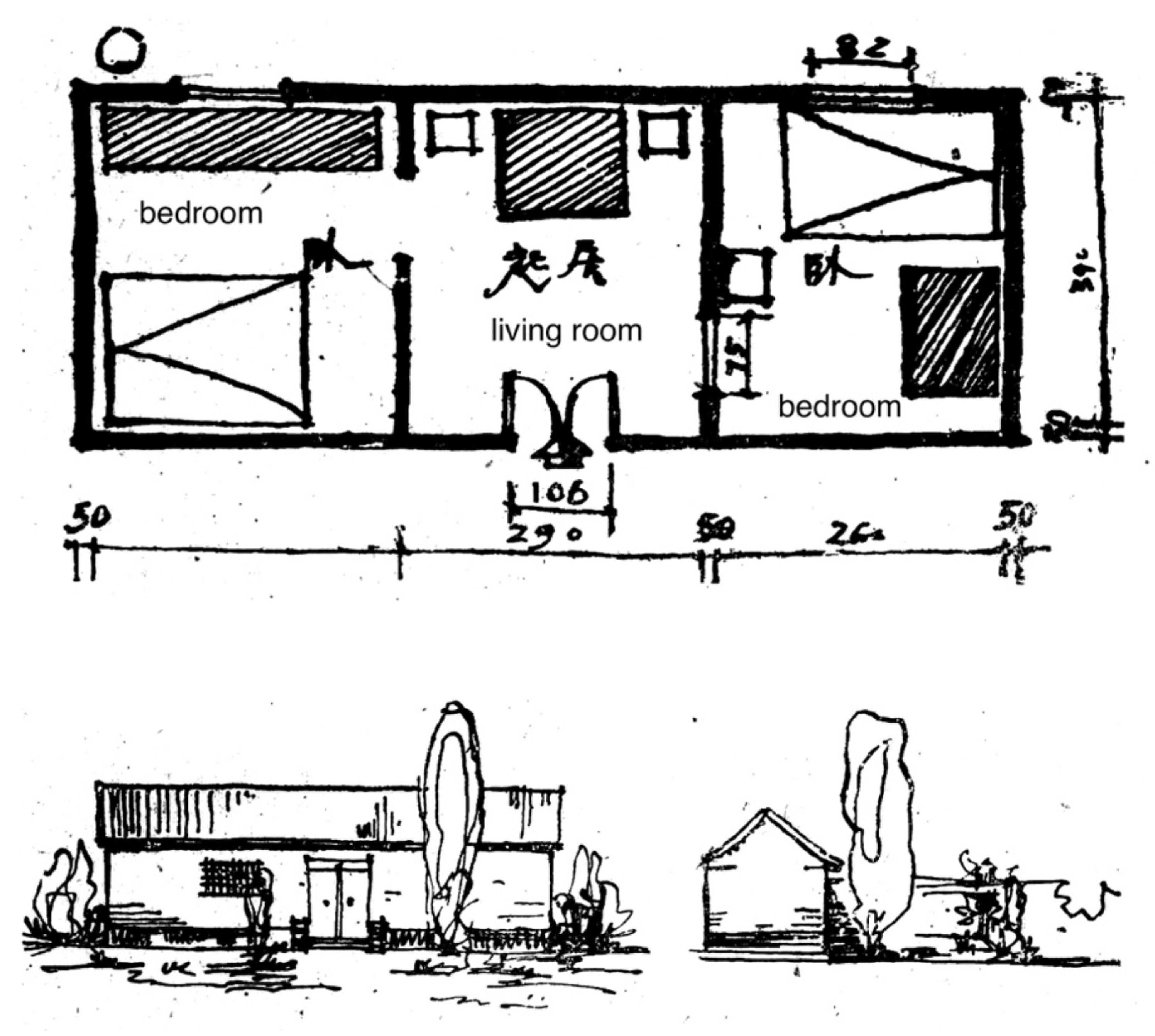

- In general, the size of the room was around 10m in length, 4.5-5.5m in width, and the plan was divided into two or three areas with a kitchen in the corner.

- The façade had simple axial symmetry and a gable roof. (Figure 6)

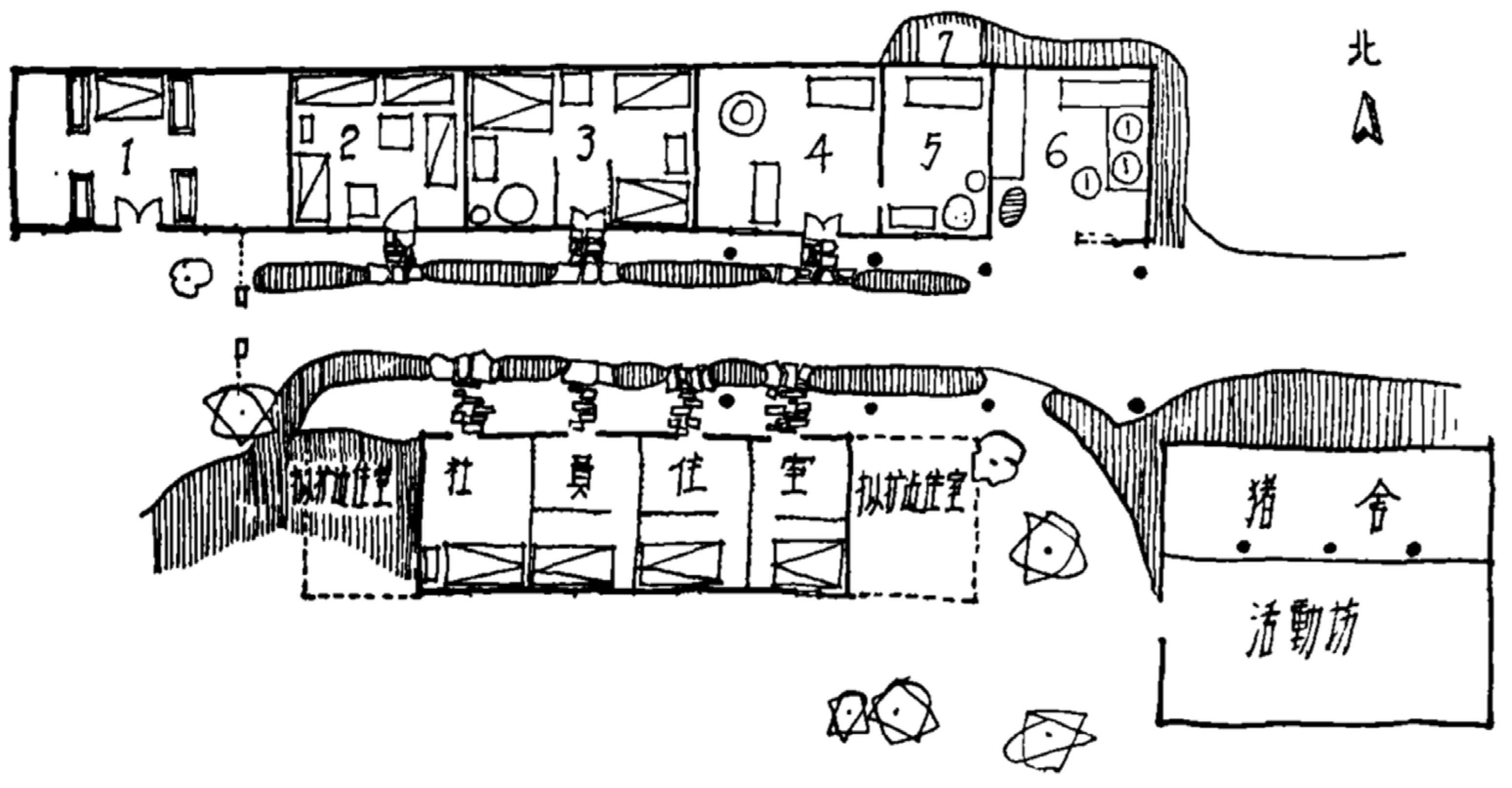

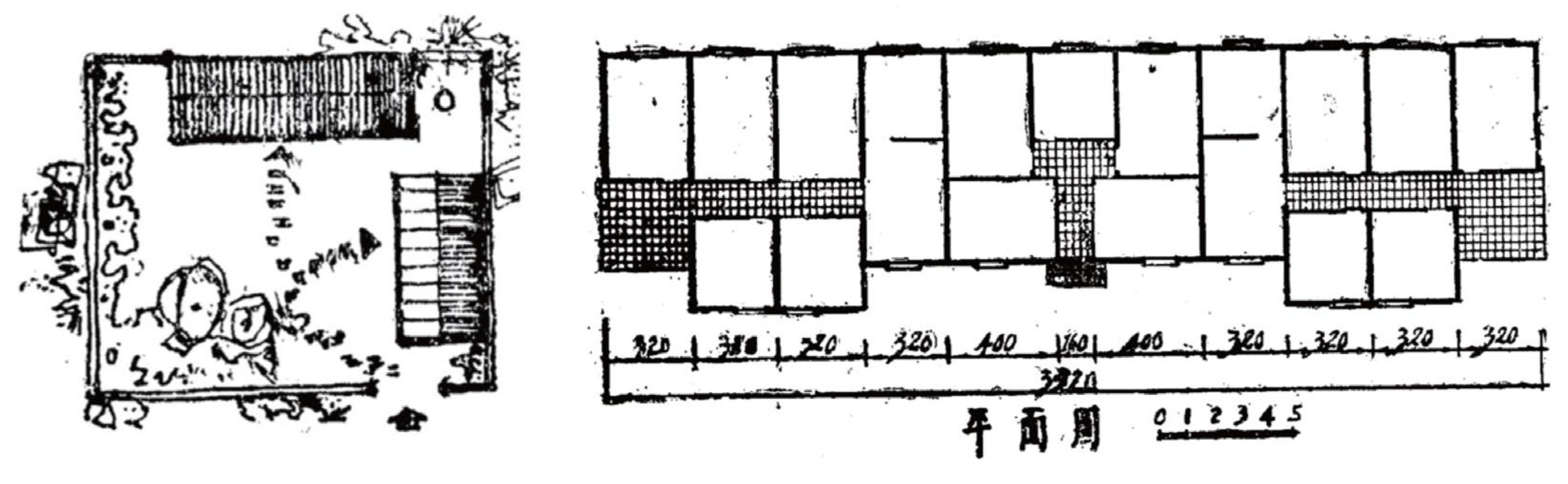

3.2. Collective house of the Longgou production brigade

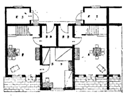

3.3. The Rural Commune Housing Design by the South China Institute of Technology

- 7.

- All the rooms have their own entrance, which ensures an independent life.

- 8.

- All the rooms are connected by a public corridor.

- 9.

- The final house building can have a flexible combination of different types of units.

- 10.

- As apparent from the perspective drawing, the building has a gable roof and the facade is simple, and manitains axial symmetry, akin to the traditional house in Qianwan village.

4. Discussion

4.1. What Disappeared in the Design Blueprints for a Modern Rural Residential Building?

- Cultivate private plots allocated by collectives.

- Raise pigs, sheep, rabbits, chickens, ducks, geese and other livestock and poultry, as well as sows and large livestock.

- Carry out household handicraft production such as knitting, sewing and embroidery.

- Engage in collection, fishing and hunting, sericulture, beekeeping, and other sideline production.

- Plant fruit trees, mulberry trees, and bamboo trees in front of and behind the house or in other places designated by the production team. These things belong to the members forever.

4.2. What Kind of “Rural Modernity” Is Reflected in the Design of People's Commune Housing?

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rural Revitalization Strategy (2018-2022). Council, C. C. C. a. t. S., Ed.; 2018.

- Zhao, C. Re-discussion on the view of time and space for studies of Chinese modern architecture. The Architect 2020, 92–95. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, G.; Gao, Y.; Xue, C. Q. L.; Xu, L. ‘Third Front’ construction in China: planning the industrial towns during the Cold War (1964–1980). Planning Perspectives 2021, 36, 1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Schoonjans, Y.; Gantois, G. The emergence and evolution of workers’ villages in early New China. Planning Perspectives 2023, 39, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H. Soviet specialists’s urban planning technical assistance to China, 1949. Planning Perspectives 2022, 37, 815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, B.; Zhao, M. A Brief Review of the Residential Planning of Chinese People's Commune. Journal of Urban and Regional Planning 2020, 12, 93–106. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, F.; Nakatani, N. Research on the Methodology of Regional Planning in the Design of People's Commune. Journal of Architecture and Planning (Transactions of AIJ) 2019, 84, 2669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Xue, C. Q. L.; Tan, G.; Chen, Y. From South China to the Global South: tropical architecture in China during the Cold War. The Journal of Architecture 2023, 27, 979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacoby, S.; Cheng, J. Collective Forms in China: An Architectural Analysis of the People’s Commune, Danwei, and Xiaoqu. In The Socio-spatial Design of Community and Governance: Interdisciplinary Urban Design in China; Jacoby, S., Cheng, J., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2020; pp. 17–69. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, D. Remaking Chinese urban form: Modernity, scarcity and space, 1949-2005; Routledge, 1949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, D. Third world modernism: architecture, development and identity; Routledge, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, D. The SAGE Handbook of Architectural Theory; SAGE Publications Ltd, 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y. The covers of Architectural Journal and the socialist fantasy during the Great Leap Forward. Architectural Journal 2014, 58–63. [Google Scholar]

- Ye, L.; Huang, Y. Design down to village again: A study of rural construction in the early years of reform and opening period, 1978. Architectural Journal 2016, 10–15. [Google Scholar]

- Ye, L.; Huang, Y. Process study of design-down-to-village from 1958 to 1966 and the influence analysis of subject and object. The Architect 2017, 91–99. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y. The planning and construction of the People’s commune in Xushui in 1958: historical records of the practice of rural construction by the department of architecture of Tsinghua University during the Great Leap Forward. Time + Architecture 2019, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, J. Spatial design as political manifesto: The design proposals of China’s People’s commune 1958. New Architecture 2018, 29–33. [Google Scholar]

- Jacoby, S.; Cheng, J. Collective forms in China: People’s commune and Danwei. New Architecture 2018, 5–11. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, J.; Cao, H. Eating together, meeting together: canteens and assembly halls in rural southern China during the era of the People’s commune. Time Architecture 2021, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shinichiro, S. People's Commune; Hagane Press, 1959. [Google Scholar]

- Strong, A. L. The rise of the Chinese People’s communes; Iwanamishinsyo Press, 1960. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, L. Farewell Ideal-Research on the System of People’s Commune; Shanghai Renmin Press, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Architectural history teaching and research group, N. I. o. T. Make do with whatever is available, from local to foreign, building new residential areas on the original basis. Architectural Journal 1959, 7–9. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Architecture, S. C. I. o. T. The planning and design of the first grassroots community of Weixing commune, Suiping county, Henan province; Guangdong People’s Publishing House, 1958. [Google Scholar]

- People's commune planning and construction investigation and research team, D. o. A., South China Institute of Technology. The planning and design of the first grassroots community of Weixing commune, Suiping county, Henan province. Architectural Journal 1958, 9–13.

- Committee, P. L. R. C. o. C. P. In Selected compilation of important documents since the founding of PRC; Central Party Literature Press, 1994; Vol. 11.

- Committee, P. L. R. C. o. C. P. In Selected compilation of important documents since the founding of PRC; Central Party Literature Press, 1996; Vol. 13.

- Committee, P. L. R. C. o. C. P. In Selected compilation of important documents since the founding of PRC; Central Party Literature Press, 1997; Vol. 15.

- Jia, Y. Apotheosis of the politics in rural area during the Great Leap Forward period-research on the Chayashan Weixing Commune, Henan Province; Intellectual Property Publishing House, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, O. Discussion on several problems in current rural housing design. Architectural Journal 1962, 09, 4–8. [Google Scholar]

| No. | Title of the commune | Design institution | Location | Summary of housing design strategy | Design plan | General information | Publication | |||||

| m2/people | floor | kitchen | pattern | |||||||||

| 01 | Hongqi commune | Tsinghua university | Beijing |

|

— | 4 | 2 | — | — | 195809 | ||

| 02 | Xiaozhan commune | Tianjing university | Tianjing |

|

1st floor 2nd floor 1st floor 2nd floor |

3.7~5 | 2 | — | Villa | 195810 | ||

| 03 | Caoyang New village | Shanghai urban construction bureau | Shanghai |

|

facade |  |

8.5 | 1&2 | — | Row house | 195810 | |

| plan | ||||||||||||

| 04 | Qiyi commune | Civil Architecture Design Institute of Shanghai | Shanghai |

|

PlanⅠ |  |

PlanⅥ | 5.3~7.5 | 2 | Some has | Linear shaped plan | 195810 |

| 05 | Xianfeng commune | Tongji University | Shanghai |

|

|

5.8 | 2 | — | Row house | 195810 | ||

| 06 | Hongqi commune of Qingpu country | Tongji University | Shanghai |

|

1st floor 2nd floor 1st floor 2nd floor |

— | 1&2 | — | Row house | 195810 | ||

| 07 | Longtan commune | Southwest Industrial Architecture Design Institute | Chengdu |

|

|

4 | 2 | — | Row house | 195811 | ||

| 08 | Puzhuang commune | Nanjing Institute of Technology | Jiangsu Province |

|

|

— | 1&2 | — | Row house | 195811 | ||

| 09 | Suicheng commune | Planning and Construction Bureau of Hebei province | Hebei Province |

|

|

4~6 | 1&2 | — | Linear shaped plan | 195811 | ||

| 10 | Weixing commune | South China Institute of Technology | Henan Province |

|

|

3.5~4 | 1&2 | — | Rectangle T-shaped r-shaped plan | 195811 | ||

| 11 | Gongzhuang commune | Urban Architecture Design Institute of Guangdong province | Guangdong Province |

|

|

4.5~7 | 1&2 | Has | Linear shaped plan | 195812 | ||

| 12 | Jinyang Village commune | Planning and Construction Bureau of Gansu province | Gansu Province |

|

— | 6 | 2 | — | — | 195812 | ||

| 13 | Dingji commune | Nanjing Institute of Technology | Jiangsu Province |

|

|

— | 1 | — | Row house | 195901 | ||

| 14 | Zhonggong commune | China Academy of building Research | Shandong Province |

|

|

— | 1&2 | Has | Linear shaped plan | 195901 | ||

| 15 | Panyu commune | South China Institute of Technology | Guangdong Province |

|

|

8~10 | 2 | — | Standard unit assembly housing with various types | 195902 | ||

| 16 | Changzheng commune | Eastern China Industrial Architectural Design Institute | Shanghai |

|

|

7.6 | 2 | Has | Linear shaped plan | 196003 | ||

| 17 | Xushui commune | Tsinghua university | Hebei Province |

|

|

— | 2 | — | Linear shaped plan | 196004 | ||

| Residential Unit Plan | Collective housing plan | Types | House houlds | Living area(m2) | Average living space(m2) | Collective housing plan | Types | House houlds | Living area(m2) | Average living space(m2) |

|

|

Ⅰ+Ⅴ | 17 | 205.8 | 12.1 |  |

Ⅰ+Ⅲ | 15 | 205.8 | 13.7 |

| Ⅳ+Ⅳ | 12 | 152 | 12.7 | Ⅵ+Ⅵ | 12 | 175 | 14.5 | |||

| Ⅰ+Ⅱ | 15 | 181.8 | 12.1 | Ⅰ+Ⅵ | 17 | 236.2 | 13.9 | |||

| Ⅰ+Ⅲ+Ⅵ | 27 | 380.8 | 14.1 | Ⅰ+Ⅵ | 22 | 297.4 | 13.5 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).