Introduction

Abortion is the termination of pregnancy before fetal viability, which is usually taken to be less than 28 weeks from the last normal menstrual period or weight of less than 1000 g [

1]. Abortion can occur either spontaneously or induced. Induced abortion can be safe or unsafe. Induced abortion is described as the intentional termination of a pregnancy through medication or surgical procedure. This is in contrast to a spontaneous abortion, commonly known as a miscarriage, which occurs naturally and without any deliberate human intervention [

2].

Globally, around 210 million women become pregnant each year, with one out of every ten pregnancies ending in an unsafely induced abortion. Of the estimated 73.3 million induced abortions each year, nearly 45% are performed unsafely, and 98% of them occur in developing countries [

3]. Although the unintended pregnancy rate has declined from 2015 to 2019, the proportion of unintended pregnancies that ended in abortion has increased by 18% [

3]. According to recent estimates, in Sub-Saharan Africa, the overall annual abortion rate is 33 per 1,000 women. The vast majority of abortion related death occur in developing countries, with a high burden in Sub-Saharan countries [

4]. In the year 2015–2019, there were 4.92 million pregnancies every year in Ethiopia; of these, 42% (2.06 million) pregnancies were unintended and approximately 632,000 ended by abortion. More than half of the induced abortions in Ethiopia are performed

outside of the healthcare system [

5]

.

Although the maternal mortality ratio (MMR) in Ethiopia declined by 46% from 871 to 401 deaths per 100,000 live births during the period of 2000 to 2017, there is still much work to be done to reach the global Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) target of 70 maternal deaths per 100,000 live births. In Ethiopia, 8.6% of maternal deaths are attributed to abortion [

6]. Therefore, to mitigate the risk of maternal mortality and morbidity resulting from abortion, it is crucial to understand the status of abortion and the determining factors within the specific contexts of each region across the country.

In 2005, Ethiopia expanded its abortion law, which had initially permitted the procedure solely to save a woman's life or preserve her physical health. But now, abortion is legally permitted in Ethiopia under the following circumstances, including cases of rape, incest, or fetal impairment. Additionally, a woman has the legal right to terminate a pregnancy if it poses a danger to her life or the life of the child. Furthermore, a woman may choose abortion if she is a minor or if physical or mental health concerns make it challenging for her to raise the child [

7]. Despite the legalization of abortion and improved accessibility of safe abortion services, almost six in 10 abortions in Ethiopia are unsafe [

8].

Previous studies showed that factors associated with abortion can vary and be influenced by a range of social, economic, and individual considerations. Some of the common factors identified in the previous studies were age, place of residence, parity, educational level, economic status, relationship status, and the availability and accessibility of reproductive health services, including contraception and family planning resources [

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15].

Despite the study area, Sidama is one of the regions with the highest magnitude of maternal death in Ethiopia [

16], there is no study that assess the burden of abortion, and there is still limited understanding of the complex interplay between individual and community-level factors in determining abortion in Sidama region. Some studies on abortions in Ethiopia have been conducted at the facility level. Due to the limited utilization of health facility services in Ethiopia, assessing abortions based on the facility data may not accurately represent the actual situation on the ground. As a result, this study aimed to assess the prevalence of abortion and determinant factors among reproductive-age women in the Sidama regional state of Ethiopia, using a community-based cross-sectional study design.

Methods

Study Area

The study was done in the northern zone, which is one of the four zones located in the Sidama region of Ethiopia [

17]. It is approximately 273 kilometers south of Addis Ababa, Ethiopia's capital city. According to the Sidama Regional Health Bureau's 2022 report, the zone had a total population of 1.29 million. The total number of reproductive-age women was 300,570, with a total of 12,023 expected pregnancies. Zone has 162

Kebeles (the bottom administrative unit in the country) with 382,000 households, eight rural districts, and two town administrations.

The vast majority of people reside in rural areas, where agriculture is the primary source of income in the northern zone. For urban residents, trade is the primary source of income. The northern zone has four primary hospitals, one general hospital, 36 health centers, and 144 health posts that are currently functional and providing MHS. Based on the Regional Health Bureau 2022 report, the major cause of maternal mortality is hemorrhage and obstructed labuor [

19].

Study Design and Population

From October 21 to November 11, 2022, a community-based cross-sectional study was conducted among WRA in the Northern Zone of Sidama Region, Ethiopia. We included all randomly selected WRA who gave live birth in the last 12 months and resided in the zone for at least for 6 months. Women who were ill during the data collection period were excluded from the study since their participation and consent could be affected.

Sample Size Calculation

The sample size for this objective was taken from another study that was designed to assess maternal health service utilization in our project because it was larger to assess abortion as well. OpenEpi version 3 was used to calculate the sample size. According to the report of a previous study, the expected prevalence of abortion (24%), was taken into consideration when computing the sample size needed to estimate the prevalence of abortion [

20], a 95% confidence level, a margin of error of 5%, and a design effect of 2.0. The formula DEFF = 1+ (n-1)*ICC], where ICC is the intraclass correlation coefficient and 'n' is the average cluster size, was used to calculate the design effect. The minimum number of clusters required was calculated by multiplying the effective sample size by the ICC. Previous studies, however, did not report the ICC value. Based on Donner's recommendation, we chose 0.05 as the typical value of the ICC from a range of values (0.01 to 0.05) [

21]. Thus, 384*0.05 = 19.2 was the minimum number of clusters required. In order to have enough power and to keep the cluster numbers adequate, this study included 22 clusters, or

kebeles. By dividing the initial sample size by the expected response rate, the sample size was modified to account for the non-response rate. Based on the above data, the estimated sample size was 613. The factors that were found to be significantly associated with abortion in earlier research conducted in Northern Ethiopia [

10], rural Haramaya district, Eastern Ethiopia [

20], and Northwest Ethiopia [

22] were used to calculate the sample size for the determinants of abortion. As a result,

Table 1 of Supplementary File 1 provides an overview of the assumptions taken into account and the sample sizes that were determined. Because it was the maximum sample size that could be determined and would be sufficient to address both of the study's objectives, the sample size of 1,140 that was derived from the second objective was used.

Sampling Method

To select eligible women, we used a multi-stage sampling method. In the first stage, four districts were chosen at random from the zone's eight districts. In the second stage, 22 kebeles were drawn at random from each of the four districts. Households with WRA who gave birth in the previous 12 months were identified in each selected kebele through a house-to-house census, and a sampling frame was created. Finally, using a simple random sampling technique, 1,140 women were drawn from the selected kebeles. If the selected mother missed three consecutive visits to the household during the data collection time, she was regarded as a non-respondent.

Study Variables

The outcome variable was prevalence of abortion since five years of preceding survey. The outcome variable has a binary response and was measured using women’s self-report. We coded outcome variable as ‘1’ for those women experienced abortion and ‘0’ for non-experienced.

We categorized the covariate variables into individual and cluster-level covariate variables. The individual-level covariates were women's and their husband's age, educational status of the women and their spouses, occupational status of the women and their spouses, household wealth index, and exposure to mass media; obstetric characteristics like gravidity, parity, stillbirth, women's age at marriage, and pregnancy status. The cluster-level covariates were community-level women's literacy, community-level poverty, community-level social media use, and distance from the nearest HF. The details of the measurement of the variables used for this study are now provided in

Table 2 of supplementary file S1.

Data Collection Techniques

We used a pre-tested and structured questionnaire to collect data. It was adopted from earlier research of a similar nature [

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15]. The questionnaire was initially developed in English. To maintain its consistency and originality, it was translated into the Sidaamu Afoo language (the first language spoken in the research area) and then back to English. The forward and backward translations were carried out by two separate translators, both English experts and fluent Sidaamu Afoo speakers. The translated questionnaire was reviewed by the principal investigator (PI) and a third individual who was likewise fluent in both languages. Then, based on the issues identified during the evaluation, any inaccuracy or inconsistency between the two versions was addressed. The PI trained the data collectors and supervisors for two days before data collection on the significance of the study, data collection processes, aims, methodologies, and ethical considerations. Before data collection, the tool was pre-tested on 5% of the sample in the Dale district of the Sidama region and revised prior to actual data collection. The post-intervention data were collected after seven weeks of delivery. The health professionals with bachelor's degrees who were blinded about the intervention status collected the data through a face-to-face interviewer-administered questionnaire at the women's homes utilizing the Open Data Kit (ODK) smartphone application (see S2 file). To minimize the risk of bias, maximum efforts were exerted to maximize response, provision of training for the data collectors and supervisors. Daily, data was archived and uploaded to the KoboToolbox server. Every day, the data were checked for completeness and consistency. Data were exported from ODK to Stata version 17 and SPSS version 26 for additional processing and analysis. Before the major analyses, the exported data were thoroughly cleaned, coded, and categorized.

Data Analysis Procedure

All required variable recoding, calculations, and categorizations were completed before beginning the primary analysis. Absolute frequencies and percentages were used as summary measures for categorical variables, while the mean with standard deviation (SD) was used as a descriptive measure for numerical variables after the distribution's normality was confirmed.

We constructed a multi-level logistic model to account for our data's hierarchical nature, to reduce potential standard error underestimation using a conventional logistic regression model [

26], and to offer a robust standard error estimate result [

27].

Five models were evaluated: Model 0, which was empty; Models 1 through 4 each have a different set of predictors: those with only individual-level predictors, those with only community-level predictors, those with both individual and community-level predictors, and the model with a random coefficient. The median odds ratio (MOR) and ICC value were used to assess the random effect model [

28]. The MOR is a prediction of the unexplained kebele-level heterogeneity, while the ICC value was used to characterize the percentage of abortion variability that is attributable to the clustering variable (

kebele). When two areas are randomly selected, the MOR is defined as the average value of the odds ratio between the areas with the lowest and highest risk of abortion. It was calculated using the formula MOR= ~

[

29]. Based on the log-likelihood with likelihood ratio test, Akaike's information criteria (AIC), and Bayesian information criteria (BIC), the best-fitting model was selected. The best-fitting model may be indicated by the smallest value of these characteristics and/or a significant likelihood ratio test [

30] (

Table 7 of supplementary file 1).

For the adjusted analysis, the multi-level mixed-effect binary logistic regression model was used to account for variation both within and between clusters. A multivariable regression model contained variables whose bivariable analysis p-values were less than 0.25 and other variables of practical significance supported literatures [

31]. To account for potential confounding variables, multivariable analyses were used. Effect modification was assessed by entering interaction terms one at a time into the multivariable analysis model. A multiple linear regression model was used to assess multicollinearity among the independent variables. We declared that the effect of multicollinearity is less likely when the variance inflation factor for all variables is less than 5 [

32].

Adjusted odds ratios (AORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were used to evaluate the existence and strength of a statistically significant association. When there was no 1 in the 95% confidence interval (CI) of the AORs, there was a confirmed statistically significant association between the variables of interest.

Ethics Statement

Ethical clearance was obtained from the Institutional Review Board of Hawassa University, College of Medicine and Health Sciences with reference number IRB/076/15. All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations (Declaration of Helsinki). Informed written consent was obtained from each study participant, after a detailed explanation of the study objectives, and the right to withdraw from the study at any time. For under-aged participants (<18 years), the permission was taken from their legal guardians with informed written consent. To maintain confidentiality, interviews were conducted in private settings, and all information collected during the data collection process was kept anonymous.

Result

The study included 1,130 study respondents out of a total of 1,140 study respondents, with a response rate of 99.12%. Women's mean (+ SD) age was 28.33 (+ 6.26) years. Most of the respondents were between the ages of 25 and 29. The majority of study participants (92.7%) identified as Sidama ethnic group members, followed the protestant Christian faith (85.9%), were married (98.1%), and were enrolled in formal education (64.6%). More than half of the study participants, 577 (51.1%), had access to mass media via television, radio, and newspapers.

Reproductive Health Characteristics

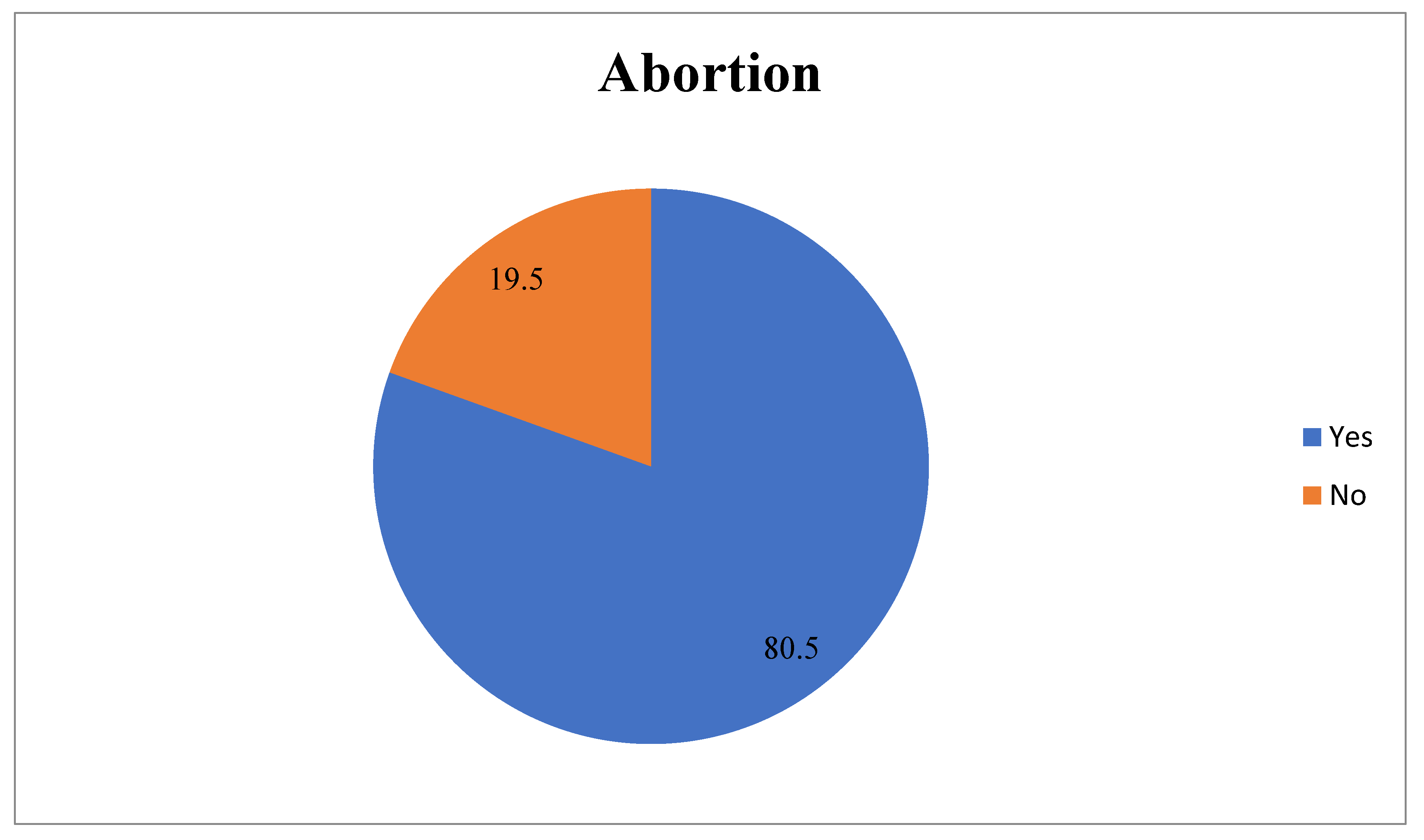

The women's mean (+ SD) age at first marriage was 18.41 + 2.33 years. Approximately 19% of the women had previously undergone an abortion. Sixty-seven percent (63.7%) of the study participants had given birth to two or more children. Of the women, 11% had given birth to a stillborn child at least once. In 68.9% of the cases, the previous pregnancy was intended.

Prevalence of Abortion

The overall prevalence of abortion was 19.5 (95% CI = 14.8-23.9) in the study area (

Figure 1).

Determinants of Abortion

Women who had attended formal education had 56% decreased odds of abortion (AOR = 0.44; 95% CI: 0.24-0.79) as compared to illiterate women. The odds of abortion were 59% lower among women who had planned pregnancy (AOR = 0.41; 95% CI: 0.28–0.61) than their counterparts, while urban residence increased the odds of abortion (AOR = 2.25; 95% CI: 1.20–4.20) as compared to rural residence (

Table 1).

Table 1.

Determinants of abortion among women of reproductive age in the Northern zone of Sidama region, Ethiopia, 2022 (N = 1,130).

Table 1.

Determinants of abortion among women of reproductive age in the Northern zone of Sidama region, Ethiopia, 2022 (N = 1,130).

| Variables |

Abortion |

COR (95% CI) |

AOR (95% CI) |

| Yes |

No |

|

|

| Individual level determinants |

|

| Women’s education status |

|

|

|

|

| Cannot read and write |

85 (28.5) |

213 (71.5) |

Ref |

Ref |

| Can read and write only (without formal education) |

24 (23.3) |

79 (76.7) |

0.64 (0.36, 1.13) |

0.55 (0.34, 1.24) |

| Have formal education |

111 (15.2) |

618 (84.8) |

0.62 (0.39, 0.89) |

0.44 (0.24, 0.79)** |

| Husband education status |

|

|

|

|

| Cannot read and write |

34 (21.5) |

124 (78.5) |

Ref |

Ref |

| Can read and write only (without formal education) |

53 (30.5) |

121 (69.5) |

1.07 (0.62, 1.85) |

1.05 (0.61, 2.17) |

| Have formal education |

133 (16.7) |

665 (83.3) |

0.62 (0.39, 0.98) |

0.45 (0.74, 2.83) |

| Women’s occupation status |

|

|

|

|

| Housewife |

161 (18.6) |

705 (81.4) |

Ref |

Ref |

| Farmer |

7 (15.5) |

32 (84.5) |

0.64 (0.21, 1.89) |

0.72 (0.23, 2.20) |

| Government employee |

22 (30.6) |

50 (69.4) |

1.32 (0.74, 2.37) |

2.47 (0.97, 6.27) |

| Merchant |

33 (21.6) |

120 (78.4) |

1.01 (0.63, 1.60) |

1.23 (0.72, 2.10) |

| Husband occupation status |

|

|

|

|

| Government employee |

32 (23.2) |

106 (76.8) |

Ref |

Ref |

| Merchant |

86 (21.6) |

313 (78.4) |

1.06 (0.64, 1.74) |

1.24 (0.56, 2.74) |

| Farmer |

85 (18.3) |

379 (81.7) |

1.02 (0.61, 1.71) |

1.08 (0.46, 2.50) |

| Daily labourer |

15 (16.1) |

78 (83.9) |

1.01 (0.48, 2.07) |

1.24 (0.47, 3.26) |

| Private organization employee |

6 (18.2) |

30 (82.8) |

0.33 (0.07, 1.53) |

0.49 (0.09, 2.45) |

| Use of mass media |

|

|

|

|

| No |

123 (22.2) |

430 (77.8) |

Ref |

Ref |

| Yes |

97 (16.8) |

480 (83.2) |

0.67 (0.48, 0.93) |

0.80 (0.53, 1.21) |

| Wealth quintile |

|

|

|

|

| Lowest |

177 (78.3) |

49 (21.7) |

Ref |

Ref |

| Second |

186 (81.2) |

43 (18.8) |

1.01 (0.61, 1.64) |

1.09 (0.64, 1.85) |

| Middle |

186 (83.4) |

37 (16.6) |

0.75 (0.45, 1.24) |

0.82 (0.47, 1.41) |

| Fourth |

188 (83.2) |

38 (16.8) |

0.60 (0.36, 1.01) |

0.79 (0.44, 1.42) |

| Highest |

173 (76.5) |

53 (23.5) |

0.79 (0.46, 1.35) |

0.97 (0.51, 1.87) |

| Age at first pregnancy© |

|

|

0.91 (0.85, 0.98) |

0.95 (0.88, 1.03) |

| Pregnancy status |

|

|

|

|

| Unplanned |

124 (35.3) |

227 (64.7) |

Ref |

Ref |

| Planned |

96 (12.3) |

683 (87.7) |

0.50 (0.31, 0.83) |

0.41 (0.28, 0.61**) |

| Road access |

|

|

|

|

| Inaccessible |

84 (25.6) |

244 (74.4) |

Ref |

Ref |

| Accessible |

136 (17.0) |

666 (83.0) |

1.98 (1.40, 2.80) |

1.46 (0.82, 2.57) |

| Woman’s decision-making power |

|

|

|

|

| Non-autonomous |

96 (31.9) |

205 (68.1) |

Ref |

Ref |

| Autonomous |

124 (15.0) |

705 (85.0) |

0.51 (0.36, 0.74) |

1.23 (0.66, 2.30) |

| Community-level determinants |

| Place of residence |

|

|

|

|

| Rural |

132 (16.0) |

692 (84.0) |

Ref |

Ref |

| Urban |

88 (28.8) |

218 (71.2) |

2.28 (1.16, 4.50) |

2.25 (1.20, 4.20)* |

| Community-level poverty |

|

|

|

|

| High |

392 (83.4) |

78 (16.6) |

Ref |

Ref |

| Low |

518 (78.5) |

142 (21.5) |

1.26 (0.64, 2.46) |

1.12 (0.63, 1.98) |

| Community-level distance to reach nearest health facility |

|

|

|

|

| Big problem |

598 (79.5) |

154 (20.5) |

Ref |

Ref |

| Not big problem |

312 (82.5) |

66 (17.5) |

0.80 (0.39, 1.64) |

0.69 (0.37, 1.29) |

| Community-level mass media use |

|

|

|

|

| Low |

491 (79.7) |

125 (20.3) |

Ref |

Ref |

| High |

419 (81.5) |

95 (18.5) |

0.91 (0.46, 1.77) |

0.82 (0.57, 1.83) |

| Community-level women literacy |

|

|

|

|

| Low |

89 (77.4) |

26 (22.6) |

Ref |

Ref |

| High |

821 (80.9) |

194 (19.1) |

0.68 (0.22, 2.06) |

0.56 (0.34, 2.30) |

Random Effect Model of Unsafe Abortion

Compared to the ordinary logistic regression model, the multi-level logistic regression model fit more accurately (p <0.001). The ICC value indicated that 12.61% of the variability in prevalence of unsafe abortion was related to membership in

kebeles. The final model, even after adjusting for all potential attributable factors, revealed that the disparity in prevalence of unsafe abortion across

kebeles continued to be statistically significant. Nearly 16.40% of the variability in prevalence of unsafe abortion across

kebeles was accounted for by

kebele membership. When the two individuals were randomly selected in separate residential areas, the MOR value showed that the residual heterogeneity between the areas was linked to 1.91 times the individual odds of unsafe abortion prevalence. The final model showed that the heterogeneity in unsafe abortion across residential areas remained statistically significant even after correcting for all possible attributable factors. Further, the effect of the women education on unsafe abortion prevalence showed significant variation across the

kebeles (variance = 0.04; 95% CI: 0.01-1.25)

Table 7 of the supplementary file 1.

Model Selection Criteria

The model fitness evaluation test of abortion showed that the empty model was the least fit (AIC = 1065.25, BIC =1075.31, and log-likelihood = -530.62). Yet, there was significant progress in the fitness of the models, particularly in the final model (AIC = 1038.90, BIC = 1070.77, and log-likelihood = -490.45). Thus, the final model is best fitted as compared to the other models.

Discussion

This study aimed to assess the magnitude of abortion and identify the associated factors in southern Ethiopia, using multilevel analysis. In this study, the magnitude of abortion was 19.5%. Lack of women’s formal education, unplanned pregnancy, and urban residence were determinants of abortion prevalence in this study area.

The magnitude of abortion found in our study is lower compared to studies conducted in Addis Ababa 39.6% [

14], Gurage zone 51.8% [

33], and Ghana 25% [

15]. This discrepancy may be attributed to the fact that the majority of our study participants resided in rural areas, whereas the aforementioned studies were conducted in urban settings and health facilities. Notably, the burden of abortion in our study is higher compared to studies conducted in Ethiopia 8.6% [

34], and Mozambique 9% [

15], which could be due to the higher rate of unintended pregnancies observed in our study population. In addition, around three-fourth of the study participants in our study were above the age of 25 years, which is a demographic known to be at a higher risk for medical and pregnancy-related complications that may lead to abortion.

This study showed that, the likelihood of having an abortion was lower for women who had attended formal education as compared with the illiterate women. This study was supported by previous study done in Gurage [

33]. This could be explained by; educated women tend to have better access to information and resources, including family planning methods and reproductive health services. They are more likely to understand the importance of Planned Parenthood and take steps to avoid unintended pregnancies. This finding underscores the importance of investing in education of women and girls. However, this finding contradicts previous studies conducted in Ethiopia and Nigeria (13,34), which reported that women with secondary education had a higher likelihood of experiencing an abortion compared to those with no formal education. This discrepancy may arise from the fact that previous studies only took into account induced abortions when measuring the outcome variable, whereas our study included both induced and spontaneous abortions in its analysis.

This study also showed that, the risk of abortion among women who had planned pregnancy was lower than their counterpart. These finding agrees with other studies conducted in Gondar, Gurage and Addis Ababa (12,14,33). A possible explanation for this finding is that women with planned pregnancies are more likely to use contraceptives consistently, and this proactive approach to family planning can significantly reduce the risk of unintended pregnancies and subsequently lowering the need for abortion. Additionally, women with planned pregnancies may experience higher levels of emotional well-being and preparedness to be a parent, which could positively influence their decision not to pursue abortion.

Women residing in urban area were more likely to experience abortion as compared to rural residence. Similar findings was reported from study conducted in Wolayita [

11]. The higher risk of abortion among women in urban areas compared to their rural counterparts is likely influenced by a complex interplay of healthcare access, socio-demographic factors, cultural influences and their vulnerability to risky sexual behavior. Despite urban women's tendency to delay childbearing for various reasons, such as career pursuits, numerous studies have shown that compared to rural women, urban women are more vulnerable to engaging in risky sexual behaviors that can lead to unintended pregnancies. In addition, on average women in urban areas have higher levels of education, leading to greater awareness of reproductive health. However, this could also mean that women in urban areas are more aware of and willing to consider abortion as a reproductive choice. In some urban settings, there might be a greater acceptance or normalization of abortion as a reproductive choice, influencing women's decisions.

Conclusions

This study revealed that the magnitude of abortion in the northern zone of the Sidama region was high. This indicated that several things remain to be done to improve the health status of women. Lack of women’s formal education, unplanned pregnancy, and urban residence were pertinent determinants of high abortion prevalence in this study setting. Therefore, any programs and intervention strategies should consider the needs of illiterate women, mothers who have unplanned pregnancies, and urban residents.

Education and having a planned pregnancy were negatively associated with abortion, while in contrast place of residence in urban area was positively associated with abortion. Therefore, to prevent the burden and consequence of abortion, it is better to implement targeted intervention on the identified factors.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org. S1 file: Some of important details in methods and results section (DOCX) S2 file: English version questionnaire (DOCX) S3 file: STROBE checklist (DOCX) S4 file: SPSS data set (SAV)

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: Amanuel Yoseph; Data curation: Amanuel Yoseph; Formal analysis: Amanuel Yoseph; Investigation: Amanuel Yoseph; Methodology: Amanuel Yoseph; Project administration: Amanuel Yoseph; Resources: Amanuel Yoseph; Software: Amanuel Yoseph; Supervision: Amanuel Yoseph; Validation: Amanuel Yoseph, Yilkal Simachew, Arsema Abebe, Asfaw Borsamo, Yohans Seifu, Mehretu Belayneh; Visualization: Amanuel Yoseph, , Yilkal Simachew, Arsema Abebe, Asfaw Borsamo, Yohans Seifu, Mehretu Belayneh; Writing – original draft: Amanuel Yoseph, , Yilkal Simachew, Arsema Abebe, Asfaw Borsamo, Yohans Seifu, Mehretu Belayneh; Writing – review & editing: Amanuel Yoseph, Yilkal Simachew, Arsema Abebe, Asfaw Borsamo, Yohans Seifu, Mehretu Belayneh

Acknowledgments

We are grateful for the financial support provided by the Sidama region president's office, NORAD project, and Hawassa University. We also express our gratitude to the district health office, supervisors, kebeles administrators, study participants, and data collectors for their invaluable contributions to the success of this research.

References

- Health, F.D. Technical and procedural guidelines for safe abortion services in Ethiopia second edition. 2013, FDRE-FHD Addis Ababa.

- World Health Organization Abortion care guideline. World Health Organization, 2022.

- Bearak, J.; Popinchalk, A.; Ganatra, B.; Moller, A.B.; Tunçalp, Ö.; Beavin, C.; et al. Unintended pregnancy and abortion by income, region, and the legal status of abortion: estimates from a comprehensive model for 1990–2019. Lancet Glob Health. 2020, 8, e1152–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bankole, A.; Remez, L.; Owolabi, O.; Philbin, J.; Williams, P. From unsafe to safe abortion in Sub-Saharan Africa: Slow but steady progress. 2020. Available online: https://www.guttmacher.org/report/from-unsafe-to-safe-abortion-in-subsaharan-africa (accessed on 25 November 2023).

- Moore, A.M.; Gebrehiwot, Y.; Fetters, T.; Wado, Y.D.; Bankole, A.; Singh, S.; et al. The Estimated Incidence of Induced Abortion in Ethiopia, 2014: Changes in the Provision of Services Since 2008. Int Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2016, 42, 111–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mekonnen, W.; Gebremariam, A. Causes of maternal death in Ethiopia between 1990 and 2016: systematic review with meta-analysis. Ethiop J Health Dev [Internet]. 2018, 32(4). Available online: https://www.ajol.info/index.php/ejhd/article/view/182583 (accessed on 25 November 2023).

- Medical society engagement in contentious policy reform: the Ethiopian Society for Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ESOG) and Ethiopia’s 2005 reform of its Penal Code on abortion - PubMed [Internet]. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29538641/ (accessed on 25 November 2023).

- The implementation of safe abortion services in Ethiopia - PubMed [Internet]. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30374983/ (accessed on 25 November 2023).

- Ahmed, R.; Sultan, M.; Abose, S.; Assefa, B.; Nuramo, A.; Alemu, A.; Demelash, M.; Eanga, S.; Mosa, H. Levels and associated factors of the maternal healthcare continuum in Hadiya zone, Southern Ethiopia: A multilevel analysis. PLoS One 2022, 17, e0275752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MA, A.A.; Assefa, H.; et al. Factors Associated with Maternal Health Care Services in Enderta District, Tigray, Northern Ethiopia: A Cross Sectional Study. American Journal of Nursing Science 2014, 3, 117–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abebe, M.; Mersha, A.; Degefa, N.; Gebremeskel, F.; Kefelew, E.; Molla, W. Determinants of induced abortion among women received maternal health care services in public hospitals of Arba Minch and Wolayita Sodo town, southern Ethiopia: unmatched case-control study. BMC Womens Health. 2022, 22, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oumer, M.; Manaye, A. Prevalence and Associated Factors of Induced Abortion Among Women of Reproductive Age Group in Gondar Town, Northwest Ethiopia. Sci J Public Health. 2019. [CrossRef]

- Yaya, S.; Amouzou, A.; Uthman, O.A.; Ekholuenetale, M.; Bishwajit, G.; Udenigwe, O.; et al. Prevalence and determinants of terminated and unintended pregnancies among married women: analysis of pooled cross-sectional surveys in Nigeria. BMJ Glob Health 2018, 3, e000707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mulatu, T.; Cherie, A.; Negesa, L. Prevalence of unwanted pregnancy and associated factors among women in reproductive age groups at selected health facilities in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. J Women’s Health Care. 2017, 6, 2167–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickson, K.S.; Adde, K.S.; Ahinkorah, B.O. Socio - economic determinants of abortion among women in Mozambique and Ghana: evidence from demographic and health survey. Arch Public Health Arch Belg Sante Publique. 2018, 76, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Variation in maternal mortality in Sidama National Regional State, southern Ethiopia: A population based cross sectional household survey - PubMed [Internet]. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36881577/ (accessed on 25 November 2023).

- Council ratify Ethiopian’s new ethnic-Sidama statehood. Borkena.com. Borkena Ethiopian News. 19 June 2020. Retrieved February 2022. . 2020. - Google Search.

- Sidama regional state council. Establishment of new zones structure and budget approval for 2015 EFY agendas report: Regional state council office, Hawassa, Ethiopia. 2022. Unpublished report. 2022.

- Sidama regional health bureau. Annual regional health and health-related report: Regional Health office, Hawassa, Ethiopia. Unpulished report. 2022.

- Kifle, D.; Azale, T.; Gelaw, Y.A.; Melsew, Y.A. Maternal health care service seeking behaviors and associated factors among women in rural Haramaya District, Eastern Ethiopia: a triangulated community-based cross-sectional study. Reprod Health. 2017, 14, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donner, A.; Birkett, N.; Buck, C. Randomization by cluster. Sample size requirements and analysis. Am J Epidemiol. 1981, 114, 906–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Getachew, T.A.A.; Aychiluhim, M. Focused Antenatal Care Service Utilization and Associated Factors in Dejen and Aneded Districts, Northwest Ethiopia. Primary Health Care 4, 170. [CrossRef]

- Central Statistical Agency (CSA) [Ethiopia] and ICF. Mini Ethiopia Demographic and Health Survey 2019: Key Indicators Report. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, and Rockville, Maryland, USA. CSA and ICF. 2019. 2019.

- Chaka, E.E. Multilevel analysis of continuation of maternal healthcare services utilization and its associated factors in Ethiopia: A cross-sectional study. PLOS Glob Public Health. 2022, 2, e0000517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoseph, M.; Abebe, S.M.; Mekonnen, F.A.; Sisay, M.; Gonete, K.A. Institutional delivery services utilization and its determinant factors among women who gave birth in the past 24 months in Southwest Ethiopia. BMC Health Serv Res. 2020, 20, 265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kleiman, E. Understanding and analyzing multilevel data from real-time monitoring studies: An easily- accessible tutorial using R [Internet]. PsyArXiv; 2017. Available from: psyarxiv.com/xf2pw. 2017.

- Snijders, T.A.B.; Bosker Roel, J. Multilevel Analysis: An Introduction to Basic and Advanced Multilevel Modeling, second edition. London etc.: Sage Publishers, 2012 1999.

- Koo, T.K.; Li, M.Y. A Guideline of Selecting and Reporting Intraclass Correlation Coefficients for Reliability Research. J Chiropr Med. Epub 2016 Mar 31. Erratum in: J Chiropr Med. 2017, 16, 346. 2016, 15, 155–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merlo, J.; Chaix, B.; Ohlsson, H.; Beckman, A.; Johnell, K.; Hjerpe, P.; Råstam, L.; Larsen, K. A brief conceptual tutorial of multilevel analysis in social epidemiology: using measures of clustering in multilevel logistic regression to investigate contextual phenomena. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2006, 60, 290–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dziak, J.J.; Coffman, D.L.; Lanza, S.T.; Li, R.; Jermiin, L.S. Sensitivity and specificity of information criteria. Brief Bioinform. 2020, 21, 553–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hosmer, D.W.; Lemeshow, S.; Sturdivant, R.X. Applied logistic regression; John Wiley & Sons, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Senaviratna, N.; Cooray, T. Diagnosing multicollinearity of logistic regression model. Asian Journal of Probability and Statistics 2019, 5, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tesfaye, G.; Hambisa, M.T.; Semahegn, A. Induced abortion and associated factors in health facilities of Guraghe zone, southern Ethiopia. J Pregnancy. 2014, 2014, 295732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yemane, G.D.; Korsa, B.B.; Jemal, S.S. Multilevel analysis of factors associated with pregnancy termination in Ethiopia. Ann Med Surg 2012, 80, 104120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).