Introduction

Neurofibroma is the most common benign peripheral nerve sheath tumor in the US. 90% of cases occur sporadically, while the remaining 10% are related to hereditary disorders, such as neurofibromatosis 1 (NF1) and 2 (NF2) [

1]. The underlying reason behind genetic and sporadic neurofibroma is the deletion of the NF1 gene. The NF1 gene is critical in forming and maintaining the connective tissue surrounding peripheral nerve sheaths and the endoneurium, essential nervous system components. If inappropriately deleted, a resulting benign tumor composed of Schwann cells, mast cells, perineural cells, and fibroblasts with a variable myxoid to the collagenous matrix can form. Specifically, sporadic neurofibromas occur when a de novo mutation in the NF1 gene takes place exclusively in lesioned cells. In contrast, neurofibromatosis-associated neurofibroma arises from a germline mutation in the NF1 gene located on chromosome 17q11.2. This gene encodes neurofibromin, a GTPase-activating protein crucial in tumor suppression [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5].

The most predominant subtype of neurofibroma is localized neurofibroma; diffuse and plexiform neurofibromas compose around 10% of cases [

1,

2]. Localized neurofibroma usually presents in middle-aged populations as a well-circumcised, unencapsulated, grey-tan solitary mass predominately in the dermis [

1]. Contrarily, diffuse neurofibroma is a unique subtype of neurofibroma often observed on adolescents' neck, head, and trunk skin and subcutaneous tissue [

2,

3]. The subtype presents as a poorly defined plaque-like infiltrative unencapsulated lesion, like a localized neurofibroma [

1,

2,

3]. Localized neurofibromas tend to present as small masses. Diffuse neurofibroma can grow significantly with possible infiltration to the fascia level and rarely present as painful lesions in middle-aged individuals [

2]. There are a minimal number of diffuse neurofibroma cases presenting as painful lesions in middle-aged individuals.

Here, we report a unique case of diffuse neurofibroma located on the scalp of a 45-year-old female that presented as a slowly enlarging subcutaneous mass for twelve years and a comprehensive review of diffuse neurofibroma and its differential diagnosis.

Case Report

Twelve years ago, a female who is now 45 years old noticed a painless bump enlarging subcutaneous nodule on her scalp. During that time, the patient did not undergo any clinical examination. Around three years ago, the patient presented to an outpatient neurology clinic with an insidious onset of debilitating headaches in the left temporal/occipital/parietal region that radiated to her neck. The patient experienced intermittent sharp pains and constant pressure in her head for several days, accompanied by nausea, dizziness, blurred vision, and sensitivity to light. She did not report any autonomic symptoms. During the neurological examination, the patient exhibited mild active hand tremors and tenderness in the left occipital area. The neurologist ordered an MRI without contrast of the brain to exclude secondary causes of headaches. The MRI revealed a nodular and irregular thickening in the parietal scalp's soft tissue that infiltrated and replaced the deep fat layer. The neurologist treated her cervicogenic headaches and occipital neuralgia with propranolol, nerve block injections, and physical therapy, which provided minimal relief for two years. The neurologist referred the patient to a dermatologist for further evaluation after finding no improvement in treatment response.

During a dermatology clinic check-up, a fatty, soft, and fleshy subcutaneous nodule measuring 9.0 x 5.0 cm was discovered on the patient's left parietal and occipital scalp. The dermatologist determined the nodule to be a neoplasm with uncertain behavior and conducted a punch biopsy to rule out lipoma or cutis verticis gyrata. The pathologist later diagnosed the nodule as a large and slow-growing neurofibroma. The patient asked for additional evaluation even though the dermatologist didn't think it was the reason for their headaches. Consequently, the dermatologist referred the patient for surgery to assess the possibility of wedge resection or excision of the mass.

The surgeon performed a resection and deemed that excision would not be feasible as the lesion involved half of her skull. Resection revealed an ill-defined soft tissue mass located predominately in the dermis. It was revealed that the region underneath the resected margin was highly vascularized, which could have been an underlying cause of her headache.

On gross examination, the resected lesion was a 5.3 x 3.8 x 1.5 cm aggregate of heavily congested red-brown lobulated soft tissue with an elliptical and elongated segment of hair-bearing tan-brown lobulated skin. The lobulated surface of the skin also contained two raised nodules that measured 0.5 cm. The lobulated soft tissue sectioning revealed normal and mottled rubbery tissue with no apparent mass or lesion. Sectioning of the skin demonstrated no apparent mass or lesion.

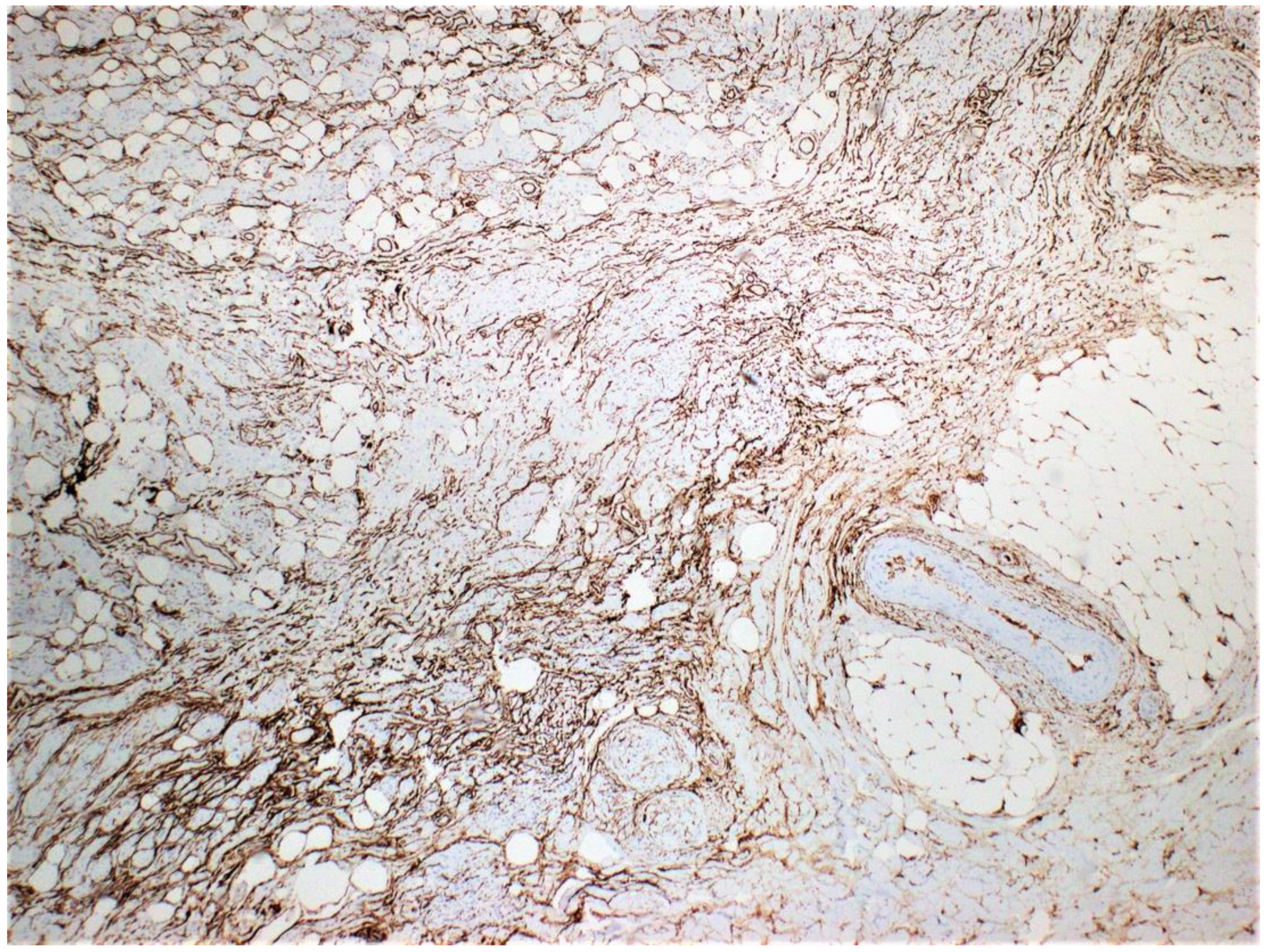

Microscopically, the lesion diffusely involved the skin dermis and subcutaneous soft tissue. Numerous vascularized areas were interspersed throughout the lesion, consistent with surgical findings. Loosely arranged spindle cells with hyperchromatic nuclei were arranged irregularly within the background of the collagenous stroma. Spindle cells had prominent infiltration of adipose tissue (

Figure 1 and

Figure 2) with the proliferation and entrapping of cutaneous adnexa structures (

Figure 3).

Due to the atypical presentation, gross examination, and microscopic examination, immunohistochemistry stains were ordered to characterize the lesion. The results were positive for HMB45, S100 (

Figure 4), CD34 (

Figure 5), and Melanin A and negative for neurofilament.

Multiple soft tissue pathologists and dermatopathologists diagnosed the resected lesion as diffuse neurofibroma. After the surgery, the patient communicated a significant reduction in the frequency and severity of her headaches, substantially improving her quality of life.

Discussion:

Localized neurofibromas are a prevalent subtype of neurofibroma commonly found in individuals aged between 20 and 40. These nodules, plaques, or solitary subcutaneous masses are typically painless and appear in a skin-colored to violaceous shade. These growths are small, measuring less than two centimeters, and can be found on various body parts, including the trunk, head, neck, and limbs. If a nerve is involved, the mass might take on a fusiform or ovoid shape. A localized neurofibroma displays a unique characteristic, the "buttonhole sign," which occurs when the mass retracts when palpated and reappears when pressure is removed. Clinicians may mistake localized neurofibromas for acrochordons or nevi, resulting in an incorrect diagnosis. If someone has numerous localized neurofibromas, it may be necessary to undergo genetic testing for NF1 to rule out the possibility of having neurofibromatosis [

1].

In contrast, diffuse neurofibroma presents on the scalp of adolescents as an ill-defined plaque with associated induration and thickened skin. Occasionally, a large diffuse neurofibroma presents with overlying numbness and tingling [

1,

2,

3]. Kumar et al. present a case of a 12-year-old male who developed diffuse neurofibroma with associated alopecia. The patient had mild tenderness in the occipital region but lacked the persistent headaches seen in our patient [

2]. Lee et al. describe the case of a 32-year-old male who developed diffuse neurofibroma on the scalp with associated alopecia. Notably, he did not experience any pain or itching in relation to the growth even though he was closer in age to our patient [

6]. Yoo et al. describe the case of a 10-year-old male with a 7.0 ×8.0 cm diffuse neurofibroma on the scalp for four years with no associated pain or headaches [

7]. Although our patient's headache was resolved through resection, it is still unclear whether diffuse neurofibroma played a role in causing her headaches. Clinicians cannot confirm this definitively.

Plexiform neurofibromas have varying presentations depending on the extension depth and location site. They arise from deeply located spinal nerve roots and have a highly ill-defined hyperpigmented and torturous appearance. Common symptoms include pain, numbness, and mass effect. Similar to diffuse neurofibroma, they can grow immensely, often surrounding multiple nerve fascicles [

1,

4]. The subtype is found in approximately 30-40 % of patients with NF1 and is considered pathognomonic for the hereditary disorder [

1,

4]. Diffuse neurofibroma is differentiated from plexiform neurofibroma subtypes by its defining characteristic of dermal and subcutaneous proliferation that irregularly entraps adnexa structures (

Figure 3) and invades underlying adipose tissue (

Figure 1 and

Figure 2). Pseudomeissenerian bodies (Wagner-Meissner bodies), composed of eosinophilic fibrillary and whorled Schwann cells, are a unique characteristic feature of diffuse neurofibroma [

1,10]. S100 is a sensitive but nonspecific marker for Schwann cells in neurofibromas (

Figure 4). In diffuse neurofibromas, CD34 staining is fingerprint-like (

Figure 5) because it stains admixed spindled fibroblasts in between collagen bundles [

1]. Plexiform neurofibroma can be differentiated from diffuse neurofibroma due to its serpentine growth pattern, possible atypia, and irregular hypertrophic nerve fascicles [

1,

4]. The patient’s clinical presentation of headache and tenderness is more in line with a plexiform neurofibroma. However, histopathological findings were consistent with a diffuse neurofibroma as microscopic examination did not reveal nuclear atypia or hypertrophic nerve fascicles. Additionally, she did not exhibit the usual alternative traits associated with NF1. The neurofibroma subtypes are microscopically similar because they comprise loosely arranged ovoid to spindle cells with hyperchromatic buckled to wavy nuclei within a background of myoxid to pale pink collagenous matrix [

1,

8,

9].

If cutaneous neurofibroma lesions are small and superficial, clinicians can perform an excisional biopsy with a microscopic examination for evaluation. However, assessing larger masses requires biopsy and CT or MRI imaging to evaluate underlying tissue involvement and guidance of possible surgical treatment [

1,

2,

3]. The preferred treatment for localized neurofibromas is surgical excision, which involves a low local recurrence rate. Minor complications of surgical excision include bleeding, pain, scar formation, and infection [

1,

5]. Surgical excision is feasible in most diffuse and plexiform neurofibromas. In the case of resection, clinicians should closely monitor for possible recurrence [

1,

8].

Before diagnosing diffuse neurofibroma, clinicians must eliminate any other possible differential diagnoses. These include malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors (MPNST), dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans, schwannoma, perineuronal, ganglioneuroma, and plexiform fibrohistiocytic tumors [

1]. Clinicians should take special care to exclude the malignant etiologies of MPNST and dermatofibromasarcoma protuberans.

MPNST is present in 8-13% of NF1 patients, with about half of the confirmed cases being those with a history of NF1 [

10,

11,13,14]. Furthermore, approximately 2% of sarcomas are identified as MPNST [13]. This type of sarcoma is more likely to occur in younger individuals, with the typical age range being between 30 and 60 years for sporadic MPNST and between 20 and 40 years for MPNST in individuals with NF1. This distinguishes it from other types of sarcomas [13].

It often arises from the sciatic nerve roots and is a rapid and painful growing mass [

10,

11,13]. MPNST can also lead to paresthesia and weakness [

1,

10,

11,13]. In approximately 50% of patients, it can spread to the lungs [

10]. MPNST is different from diffuse neurofibroma in several ways. It is a deep tumor larger than 5.0 cm with nuclear atypia, mitotic figures, necrosis, and high cellularity. [

1,

10,

11,13]. The tissue is made up of spindle cells that are organized in intersecting fascicles, as observed through histology [13]. The best treatment option is surgical removal, but it has a 65% chance of recurring which depends on the size, location, and margin status of the tumor [15]. The presenting patient did not have a history of NF1 and did not present with the characteristic café au lait spots, axillary freckling, or additional typical features present in NF1. Microscopic examination was not prominent for nuclear atypia, necrosis, or mitotic figures.

Dermatofibromasarcoma protuberans, an indolent soft tissue sarcoma, presents as a small, slow-growing, skin-colored dermal plaque with associated subcutaneous thickening and infiltration of adipose tissue, was also a top differential diagnosis in the presenting patient [

1,16]. Dermatofibromasarcoma protuberans have a predilection for the trunk of males with a median age of 39. It differs from diffuse neurofibroma and MPNST in that its size is typically less than 5.0 cm [17]. The condition results from rearrangements in chromosomes 17 and 22, which leads to the fusion of COL1A1 and PDGFB genes [17]. It can be differentiated from diffuse neurofibroma due to its honeycomb pattern of infiltration and negative S100 and Melan A and diffuse rather than fingerprint CD34 positivity [

1,16]. The initial approach to treatment involves resection, which has a lower likelihood of recurring, at less than 10%, compared to the recurrence rate of MPNST. Additionally, radiation therapy can lower the possibility of a recurrence [17].

Conclusion

To properly diagnose diffuse neurofibroma, it is essential to identify its distinct histopathological features, as the condition's clinical presentation can vary. Although diffuse neurofibroma is less prevalent than localized neurofibroma in middle-aged populations, it is an important differential diagnosis in individuals with an infiltrative subcutaneous nodule on the scalp.

Author Contributions

Michelle R. Anthony, BS : conception and design, or analysis and interpretation of data, drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content, final approval of the version to be published, agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work. Dory Esther Arevalo Salazar, MD, conception and design, or analysis and interpretation of data, drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content, final approval of the version to be published, agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work. Christopher Farkouh, BS: conception and design, or analysis and interpretation of data, drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content, final approval of the version to be published, agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work. Parsa Abdi, BSc: conception and design, or analysis and interpretation of data, drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content, final approval of the version to be published, agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work. Faiza Amatul-Hadi: conception and design, or analysis and interpretation of data, drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content, final approval of the version to be published, agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work. Achyut K. Bhattacharya, MD: conception and design, or analysis and interpretation of data drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content, final approval of the version to be published, agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Conferences

The case report was presented as a poster at the ASDP 59th Annual Meeting

Acknowledgments

No funding sources were utilized in the composition of this research.

Statements and Declarations

The authors report no conflicts of interest. No funding sources were utilized in the composition of this research. The authors warrant that the described work is original, has not been published previously or under consideration by another journal, does not infringe upon any copyright of a third party, and will not be published elsewhere, whether online or in print, once accepted.

References

- Messersmith L, Krauland K. Neurofibroma. [Updated 2021 Aug 22]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2022 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK539707/.

- Kumar BS, Gopal M, Talwar A, Ramesh M. Diffuse neurofibroma of the scalp presenting as a circumscribed alopecic patch. Int J Trichology. 2010;2(1):60-62. [CrossRef]

- Hassell DS, Bancroft LW, Kransdorf MJ, Peterson JJ, Berquist TH, Murphey MD, Fanburg-Smith JC. Imaging appearance of diffuse neurofibroma. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2008 Mar;190(3):582-8. PMID: 18287425. [CrossRef]

- Staser K, Yang FC, Clapp DW. Pathogenesis of plexiform neurofibroma: tumor-stromal/hematopoietic interactions in tumor progression. Annu Rev Pathol. 2012;7:469-495. [CrossRef]

- Allaway RJ, Gosline SJC, La Rosa S, et al. Cutaneous neurofibromas in the genomics era: current understanding and open questions. Br J Cancer. 2018;118(12):1539-1548. [CrossRef]

- Lee IT, Chang JM, Fu Y. Diffuse Neurofibroma: An Uncommon Cause of Alopecia. Skin Appendage Disord. 2020;6(3):151-154. [CrossRef]

- Yoo KH, Kim BJ, Rho YK, et al. A case of diffuse neurofibroma of the scalp. Ann Dermatol. 2009;21(1):46-48. [CrossRef]

- Serletis D, Parkin P, Bouffet E, Shroff M, Drake JM, Rutka JT. Massive plexiform neurofibromas in childhood: natural history and management issues. J Neurosurg. 2007 May;106(5 Suppl):363-7.

- Woodruff JM. Pathology of tumors of the peripheral nerve sheath in type 1 neurofibromatosis. Am J Med Genet. 1999 Mar 26;89(1):23-30. [CrossRef]

- Shiurba RA, Eng LF, Urich H. The structure of pseudomeissnerian corpuscles. An immunohistochemical study. Acta Neuropathol. 1984;63(2):174-6. [CrossRef]

- A C S, Sridharan S, Mahendra B, Chander V. Malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumour-A case report. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2019;64:161-164. [CrossRef]

- Evans D.G., Baser M.E., McGaughran J. Malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors in neurofibromatosis 1. J. Med. Genet. 2002;39:311–314.

- Farid M., Demicco, E.G., Garcia R. Malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors. Oncologist. 2014;19(2):193–201.

- Spurlock G, Knight SJ, Thomas N, Kiehl TR, Guha A, Upadhyaya M. Molecular evolution of a neurofibroma to malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor (MPNST) in an NF1 patient: correlation between histopathological, clinical and molecular findings. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2010 Dec;136(12):1869-80. Epub 2010 Mar 15. PMID: 20229272. [CrossRef]

- Rawal G, Zaheer S, Ahluwalia C, Dhawan I. Malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor of the transverse colon with peritoneal metastasis: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2019;13(1):15. Published 2019 Jan 18. [CrossRef]

- Hao X, Billings SD, Wu F, et al. Dermatofibrosarcoma Protuberans: Update on the Diagnosis and Treatment. J Clin Med. 2020;9(6):1752. Published 2020 Jun 5. [CrossRef]

- Mendenhall WM, Zlotecki RA, Scarborough MT. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans. Cancer. 2004;101(11):2503-2508. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).