Submitted:

19 September 2024

Posted:

20 September 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

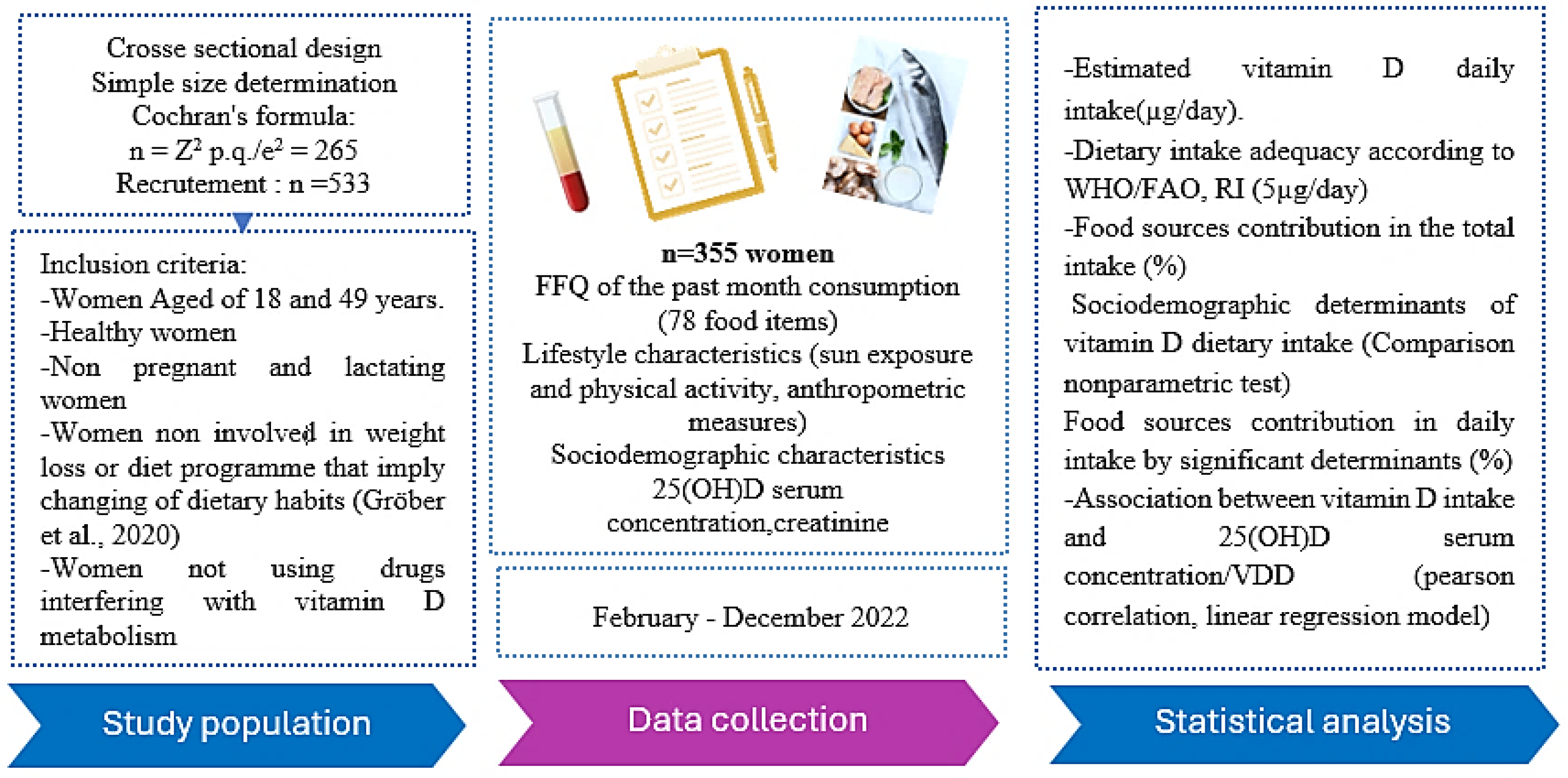

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Population

2.3. Questionnaires

2.3. Measures

2.3. Ethics

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

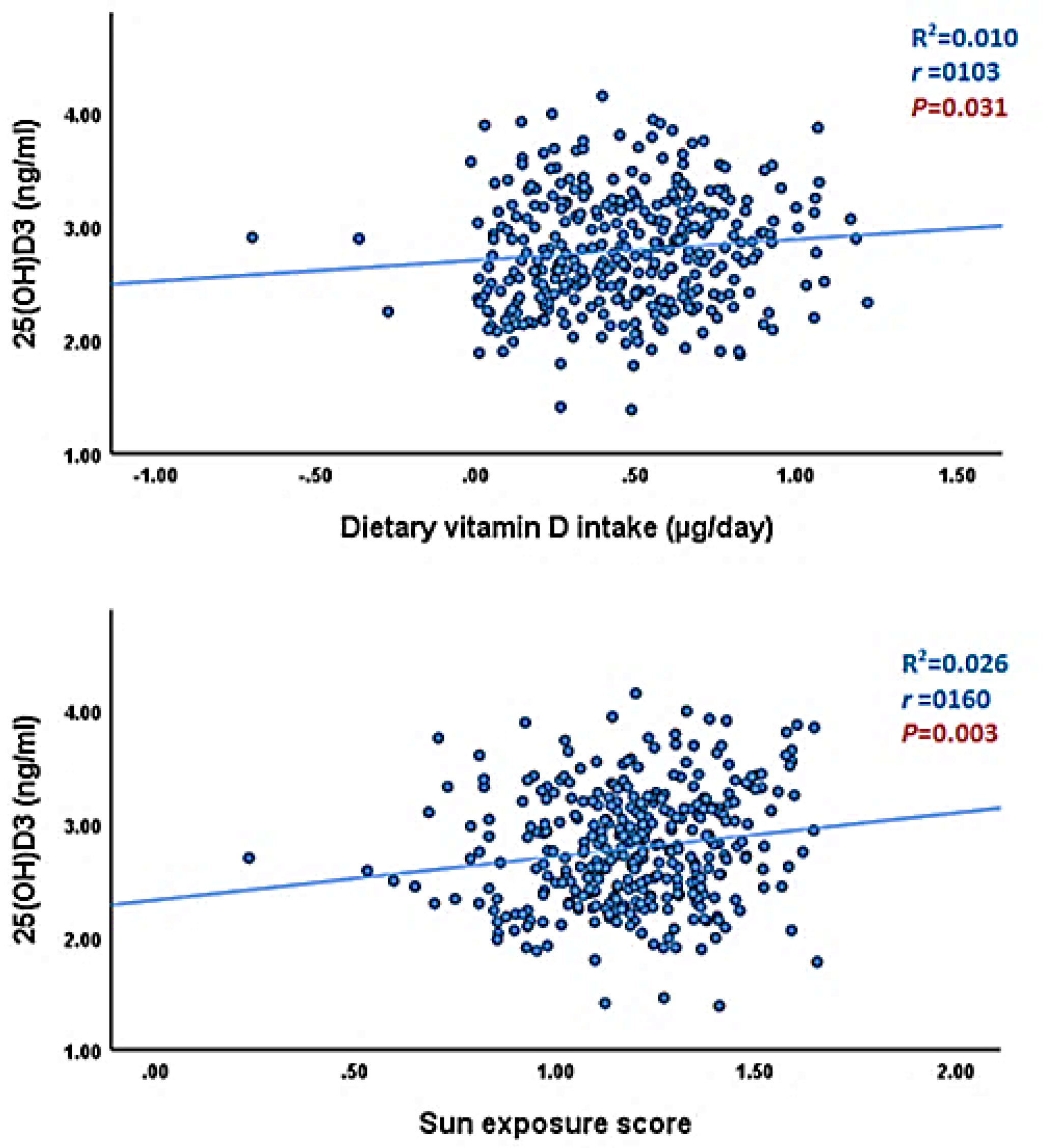

| Predicators | Unstandardized Coefficients | 95.0% Confidence Interval for β | t | P value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | Std. Error | Lower Bound | Upper Bound | |||

| Dietary vitamin D intake (µg/day) | 0.155 | 0.094 | 1.108 | 1.204 | 0.030 | 0.340 |

| Sun exposure score | 0.343 | 0.128 | 0.092 | 0.595 | 2.683 | 0.008 |

| IMC (kg/m2) | −1.128 | 0.337 | −1.790 | −0.466 | −3.350 | 0.001 |

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Janoušek, J.; Pilařová, V.; Macáková, K.; Nomura, A.; Veiga-Matos, J.; Silva, D.D.D.; Remião, F.; Saso, L.; Malá-Ládová, K.; Malý, J.; et al. Vitamin D: Sources, Physiological Role, Biokinetics, Deficiency, Therapeutic Use, Toxicity, and Overview of Analytical Methods for Detection of Vitamin D and Its Metabolites. Crit. Rev. Clin. Lab. Sci. 2022, 59, 517–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeLuca, H.F. Vitamin D. In Vitamins & Hormones; Elsevier, 2016; Vol. 100, pp. 1–20 ISBN 978-0-12-804824-5.

- Bergwitz, C.; Jüppner, H. Regulation of Phosphate Homeostasis by PTH, Vitamin D, and FGF23. Annu. Rev. Med. 2010, 61, 91–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bouillon, R.; Marcocci, C.; Carmeliet, G.; Bikle, D.; White, J.H.; Dawson-Hughes, B.; Lips, P.; Munns, C.F.; Lazaretti-Castro, M.; Giustina, A.; et al. Skeletal and Extraskeletal Actions of Vitamin D: Current Evidence and Outstanding Questions. Endocr. Rev. 2019, 40, 1109–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanel, A.; Carlberg, C. Time-Resolved Gene Expression Analysis Monitors the Regulation of Inflammatory Mediators and Attenuation of Adaptive Immune Response by Vitamin D. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creo, A.L.; Thacher, T.D.; Pettifor, J.M.; Strand, M.A.; Fischer, P.R. Nutritional Rickets around the World: An Update. Paediatr. Int. Child Health 2017, 37, 84–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berridge, M.J. Vitamin D Deficiency and Diabetes. Biochem. J. 2017, 474, 1321–1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghaseminejad-Raeini, A.; Ghaderi, A.; Sharafi, A.; Nematollahi-Sani, B.; Moossavi, M.; Derakhshani, A.; Sarab, G.A. Immunomodulatory Actions of Vitamin D in Various Immune-Related Disorders: A Comprehensive Review. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 950465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuomo, A.; Maina, G.; Bolognesi, S.; Rosso, G.; Beccarini Crescenzi, B.; Zanobini, F.; Goracci, A.; Facchi, E.; Favaretto, E.; Baldini, I.; et al. Prevalence and Correlates of Vitamin D Deficiency in a Sample of 290 Inpatients With Mental Illness. Front. Psychiatry 2019, 10, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jorge, A.J.L.; Cordeiro, J.R.; Rosa, M.L.G.; Bianchi, D.B.C. Vitamin D Deficiency and Cardiovascular Diseases. Int. J. Cardiovasc. Sci. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCullough, M.L.; Zoltick, E.S.; Weinstein, S.J.; Fedirko, V.; Wang, M.; Cook, N.R.; Eliassen, A.H.; Zeleniuch-Jacquotte, A.; Agnoli, C.; Albanes, D.; et al. Circulating Vitamin D and Colorectal Cancer Risk: An International Pooling Project of 17 Cohorts. JNCI J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2019, 111, 158–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernando, M.; Ellery, S.J.; Marquina, C.; Lim, S.; Naderpoor, N.; Mousa, A. Vitamin D-Binding Protein in Pregnancy and Reproductive Health. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Binkley, N.; Bikle, D.D.; Dawson-Hughes, B.; Plum, L.; Sempos, C.; DeLuca, H.F. Nonskeletal Effects of Vitamin D. In Principles of Bone Biology; Elsevier, 2020; pp. 757–774 ISBN 978-0-12-814841-9.

- Grant, W.B.; Cross, H.S.; Garland, C.F.; Gorham, E.D.; Moan, J.; Peterlik, M.; Porojnicu, A.C.; Reichrath, J.; Zittermann, A. Estimated Benefit of Increased Vitamin D Status in Reducing the Economic Burden of Disease in Western Europe. Prog. Biophys. Mol. Biol. 2009, 99, 104–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holick, M.F. Ultraviolet B Radiation: The Vitamin D Connection. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2017, 996, 137–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clemens, T.L.; Henderson, S.L.; Adams, J.S.; Holick, M.F. INCREASED SKIN PIGMENT REDUCES THE CAPACITY OF SKIN TO SYNTHESISE VITAMIN D3. The Lancet 1982, 319, 74–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chakhtoura, M.; Rahme, M.; Chamoun, N.; El-Hajj Fuleihan, G. Vitamin D in the Middle East and North Africa. Bone Rep. 2018, 8, 135–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarty, C.A. Sunlight Exposure Assessment: Can We Accurately Assess Vitamin D Exposure from Sunlight Questionnaires? Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2008, 87, 1097S–1101S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cashman, K.D.; Dowling, K.G.; Škrabáková, Z.; Gonzalez-Gross, M.; Valtueña, J.; De Henauw, S.; Moreno, L.; Damsgaard, C.T.; Michaelsen, K.F.; Mølgaard, C.; et al. Vitamin D Deficiency in Europe: Pandemic? Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2016, 103, 1033–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holick, M.F. The Vitamin D Deficiency Pandemic: Approaches for Diagnosis, Treatment and Prevention. Rev. Endocr. Metab. Disord. 2017, 18, 153–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mogire, R.M.; Mutua, A.; Kimita, W.; Kamau, A.; Bejon, P.; Pettifor, J.M.; Adeyemo, A.; Williams, T.N.; Atkinson, S.H. Prevalence of Vitamin D Deficiency in Africa: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Lancet Glob. Health 2020, 8, e134–e142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lips, P.; Cashman, K.D.; Lamberg-Allardt, C.; Bischoff-Ferrari, H.A.; Obermayer-Pietsch, B.; Bianchi, M.L.; Stepan, J.; El-Hajj Fuleihan, G.; Bouillon, R. Current Vitamin D Status in European and Middle East Countries and Strategies to Prevent Vitamin D Deficiency: A Position Statement of the European Calcified Tissue Society. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 2019, 180, P23–P54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brannon, P.M.; Picciano, M.F. Vitamin D in Pregnancy and Lactation in Humans. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 2011, 31, 89–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cashman, K.D. Global Differences in Vitamin D Status and Dietary Intake: A Review of the Data. Endocr. Connect. 2022, 11, e210282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ganji, V.; Shi, Z.; Al-Abdi, T.; Al Hejap, D.; Attia, Y.; Koukach, D.; Elkassas, H. Association between Food Intake Patterns and Serum Vitamin D Concentrations in US Adults. Br. J. Nutr. 2023, 129, 864–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Armas, L.A.G.; Hollis, B.W.; Heaney, R.P. Vitamin D 2 Is Much Less Effective than Vitamin D 3 in Humans. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2004, 89, 5387–5391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holick, M.F.; Biancuzzo, R.M.; Chen, T.C.; Klein, E.K.; Young, A.; Bibuld, D.; Reitz, R.; Salameh, W.; Ameri, A.; Tannenbaum, A.D. Vitamin D2 Is as Effective as Vitamin D3 in Maintaining Circulating Concentrations of 25-Hydroxyvitamin D. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2008, 93, 677–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roseland, J.M.; Phillips, K.M.; Patterson, K.Y.; Pehrsson, P.R.; Taylor, C.L. Vitamin D in Foods. In Vitamin D; Elsevier, 2018; pp. 41–77 ISBN 978-0-12-809963-6.

- Niedermaier, T.; Gredner, T.; Kuznia, S.; Schöttker, B.; Mons, U.; Lakerveld, J.; Ahrens, W.; Brenner, H. On behalf of the PEN-Consortium Vitamin D Food Fortification in European Countries: The Underused Potential to Prevent Cancer Deaths. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 2022, 37, 309–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usual Nutrient Intake from Food and Beverages, by Gender and Age, What We Eat in America, NHANES 2013-2016. 2019. Available online: http://Www.Ars.Usda.Gov/Nea/Bhnrc/Fsrg.

- Vatanparast, H.; Patil, R.P.; Islam, N.; Shafiee, M.; Whiting, S.J. Vitamin D Intake from Supplemental Sources but Not from Food Sources Has Increased in the Canadian Population Over Time. J. Nutr. 2020, 150, 526–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spiro, A.; Buttriss, J.L. Vitamin D: An Overview of Vitamin D Status and Intake in E Urope. Nutr. Bull. 2014, 39, 322–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrenya, N.; Lamberg-Allardt, C.; Melhus, M.; Broderstad, A.R.; Brustad, M. Vitamin D Status in a Multi-Ethnic Population of Northern Norway: The SAMINOR 2 Clinical Survey. Public Health Nutr. 2020, 23, 1186–1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raulio, S.; Erlund, I.; Männistö, S.; Sarlio-Lähteenkorva, S.; Sundvall, J.; Tapanainen, H.; Vartiainen, E.; Virtanen, S.M. Successful Nutrition Policy: Improvement of Vitamin D Intake and Status in Finnish Adults over the Last Decade. Eur. J. Public Health 2016, ckw154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvo, M.S.; Whiting, S.J.; Barton, C.N. Vitamin D Intake: A Global Perspective of Current Status. J. Nutr. 2005, 135, 310–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- PNN, Enquête Nationale sur la Nutrition, Diversité alimentaire, Carence en Fer, Carence en Vitamine A, Carence en Iode, 2019. Available online: https://www.sante.gov.ma/Documents/2022/07/rapport%20ENN%202019-2020%20ajout%20preface%20(1).pdf.

- Allali, F.; El Aichaoui, S.; Khazani, H.; Benyahia, B.; Saoud, B.; El Kabbaj, S.; Bahiri, R.; Abouqal, R.; Hajjaj-Hassouni, N. High Prevalence of Hypovitaminosis D in Morocco: Relationship to Lifestyle, Physical Performance, Bone Markers, and Bone Mineral Density. Semin. Arthritis Rheum. 2009, 38, 444–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baki, S.; El Mghari, G.; El Ansari, N.; Harkati, I.; Tali, A.; Chabaa, L. Statut de la vitamine de la vitamine D chez les femmes marocaines vivant a Marrakech. Ann. Endocrinol. 2015, 76, 490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dadda, S.; Azekour, K.; Sebbari, F.; El Houate, B.; El Bouhali, B. Sun Exposure, Dressing Habits, and Vitamin D Status in Morocco. E3S Web Conf. 2021, 319, 01097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benhammou, S.; Heras-González, L.; Ibáñez-Peinado, D.; Barceló, C.; Hamdan, M.; Rivas, A.; Mariscal-Arcas, M.; Olea-Serrano, F.; Monteagudo, C. Comparison of Mediterranean Diet Compliance between European and Non-European Populations in the Mediterranean Basin. Appetite 2016, 107, 521–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glenn, D.I.; Glenn, D.; Israel. Determining Sample Size 1. University of Florida IFAS Extension. pp. 1–5. Available online: Http://Edis.Ifas.Ufl.Edu (accessed on 10 February 2019).

- Zouine, N.; Lhilali, I.; Menouni, A.; Godderis, L.; El Midaoui, A.; El Jaafari, S.; Zegzouti Filali, Y. Development and Validation of Vitamin D- Food Frequency Questionnaire for Moroccan Women of Reproductive Age: Use of the Sun Exposure Score and the Method of Triad’s Model. Nutrients 2023, 15, 796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization (WHO)and Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO). Vitamin and Mineral Requirments in Human Nutrition.Second Edition [Cited 2023 Oct 15]; Available from: Https://Iris.Who.Int/Bitstream/Handle/10665/42716/9241546123.PDF Sequence=1; WHO and FAO, Ed.; 2. ed.; Geneva, 2004; ISBN 978-92-4-154612-6.

- Lhilali, I.; Zouine, N.; Menouni, A.; Godderis, L.; Kestemont, M.-P.; El Midaoui, A.; El Jaafari, S.; Filali-Zegzouti, Y. Sun Exposure Score and Vitamin D Levels in Moroccan Women of Childbearing Age. Nutrients 2023, 15, 688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graig et al Craig, C., Marshall, A., Sjostrom, M.; et al. International Physical Activity Questionnaire-Short Form. J Am Coll Health, 2017, Vol. 65, No 7, p. 492-501.; 2017.

- Forde Forde, C. Scoring the International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ); University of Dublin: Dublin, Ireland, 2018; p. 3I. [Google Scholar]

- Holick, M.F. The Vitamin D Deficiency Pandemic: Approaches for Diagnosis, Treatment and Prevention. Rev. Endocr. Metab. Disord. 2017, 18, 153–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouillon, R.; Van Schoor, N.M.; Gielen, E.; Boonen, S.; Mathieu, C.; Vanderschueren, D.; Lips, P. Optimal Vitamin D Status: A Critical Analysis on the Basis of Evidence-Based Medicine. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2013, 98, E1283–E1304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holick, M.F. Vitamin D Status: Measurement, Interpretation, and Clinical Application. Ann. Epidemiol. 2009, 19, 73–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, J.; Qiu, Y.; Li, Y.; Li, J.; Liao, R.; Du, H.; Jiang, L.; Wang, L.; Qin, Z.; Yang, Q.; et al. Associations Between 25-Hydroxyvitamin D, Kidney Function, and Insulin Resistance Among Adults in the United States of America. Front. Nutr. 2022, 8, 716878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levey, A.S. A More Accurate Method To Estimate Glomerular Filtration Rate from Serum Creatinine: A New Prediction Equation. Ann. Intern. Med. 1999, 130, 461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spiro, A.; Buttriss, J.L. Vitamin D: An Overview of Vitamin D Status and Intake in E Urope. Nutr. Bull. 2014, 39, 322–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouillon, R. Comparative Analysis of Nutritional Guidelines for Vitamin D. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2017, 13, 466–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benazouz, E.M.; Majdi, M.; Aguenaou, H.; Benazouz, E.M.; Majdi, M.; Aguenaou, H. Référentiel Législatif et Réglementaire Relatif à La Fortification Des Denrées Alimentaires Par l’adjonction de Vitamines et de Minéraux, ONSSA/MS/GAIN/UNICEF: Maroc, 2006; 2006.

- Gannagé-Yared; Chemali; Sfeir; Maalouf; Halaby Dietary Calcium and Vitamin D Intake in an Adult Middle Eastern Population: Food Sources and Relation to Lifestyle and PTH. Int. J. Vitam. Nutr. Res. 2005, 75, 281–289. [CrossRef]

- Zareef, T.A.; Jackson, R.T.; Alkahtani, A.A. Vitamin D Intake among Premenopausal Women Living in Jeddah: Food Sources and Relationship to Demographic Factors and Bone Health. J. Nutr. Metab. 2018, 2018, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faid, F.; Nikolic, M.; Milesevic, J.; Zekovic, M.; Kadvan, A.; Gurinovic, M.; Glibetic, M. Assessment of Vitamin D Intake among Libyan Women—Adaptation and Validation of Specific Food Frequency Questionnaire. Libyan J. Med. 2018, 13, 1502028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naifar, M.; Jerbi, A.; Turki, M.; Fourati, S.; Sawsan, F.; Bel Hsan, K.; Elleuch, A.; Chaabouni, K.; Ayedi, F. Valeurs de référence de la vitamine D chez la Femme du Sud Tunisien. Nutr. Clin. Métabolisme 2020, 34, 169–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrade, J.M.; Grandoff, P.G.; Schneider, S.T. Vitamin D Intake and Factors Associated With Self-Reported Vitamin D Deficiency Among US Adults: A 2021 Cross-Sectional Study. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 899300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Public health Englend and food standard agency. National nutrition and diet survey (NNDS): Yeras 9 to 11 of the rolling programme (2016-2017) to (2018-2019). Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/ndns-results-from-years-9-to-11-2016-to-2017-and-2018-to-2019.

- Aguenaou, H.; Rahmani, M. Dossier Technique de la Fortification du Lait. 2007.

- Anses Anses et Rapport d’expertise Collective Saisine 2014-SA-0234 « Etude INCA3 » Étude Individuelle Nationale Des Consommations Alimentaires 3 (INCA 3); 2014.

- Brouzes, C.M.; Darcel, N.; Tomé, D.; Dao, M.C.; Bourdet-Sicard, R.; Holmes, B.A.; Lluch, A. Urban Egyptian Women Aged 19–30 Years Display Nutrition Transition-Like Dietary Patterns, with High Energy and Sodium Intakes, and Insufficient Iron, Vitamin D, and Folate Intakes. Curr. Dev. Nutr. 2020, 4, nzz143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Rodríguez, L.G.; Estaire, P.; Peñas-Ruiz, C.; Ortega, R.M. UCM Research Group VALORNUT (920030) Vitamin D Intake and Dietary Sources in a Representative Sample of Spanish Adults. J. Hum. Nutr. Diet. Off. J. Br. Diet. Assoc. 2013, 26 Suppl 1, 64–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naji, M.; Fatih, M.; Ebndaoud, G. Moroccan Canned Sardines Value Chain: Governance and Value Added Distribution. Int. J. Dev. Econ. Sustain. 2015, 3(2), 11–24. [Google Scholar]

- Lehmann, U.; Gjessing, H.R.; Hirche, F.; Mueller-Belecke, A.; Gudbrandsen, O.A.; Ueland, P.M.; Mellgren, G.; Lauritzen, L.; Lindqvist, H.; Hansen, A.L.; et al. Efficacy of Fish Intake on Vitamin D Status: A Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2015, 102, 837–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Del Brutto, O.H.; Mera, R.M.; Rumbea, D.A.; Arias, E.E.; Guzmán, E.J.; Sedler, M.J. On the Association between Dietary Oily Fish Intake and Bone Mineral Density in Frequent Fish Consumers of Amerindian Ancestry. The Three Villages Study. Arch. Osteoporos. 2024, 19, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nindrea, R.D.; Aryandono, T.; Lazuardi, L.; Dwiprahasto, I. Protective Effect of Omega-3 Fatty Acids in Fish Consumption Against Breast Cancer in Asian Patients: A Meta-Analysis. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2019, 20, 327–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendivil, C.O. Fish Consumption: A Review of Its Effects on Metabolic and Hormonal Health. Nutr. Metab. Insights 2021, 14, 117863882110223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Utri, Z.; Głąbska, D. Vitamin D Intake in a Population-Based Sample of Young Polish Women, Its Major Sources and the Possibility of Meeting the Recommendations. Foods 2020, 9, 1482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abourazzak, F.E.; Khazzani, H.; Mansouri, S.; Ali, S.; Alla, O.; Allali, F.; Maghraoui, A.E.; Larhrissi, S.; Rachidi, W.; Ichchou, L. Recommandations de la Société Marocaine de Rhumatologie sur la vitamine D chez l’Adulte. 2016.

- Agodi, A.; Maugeri, A.; Magnano San Lio, R.; Favara, G.; Vinciguerra, M.; Barchitta, M. How Does Education Affect Diet in Women? A Comparison between Central and Southern Europe Cohorts. Eur. J. Public Health 2019, 29, ckz185.386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso-Cabezas, M.; Pollán, M.; Alonso-Ledesma, I.; Fernández De Larrea-Baz, N.; Lucas, P.; Sierra, Á.; Castelló, A.; Pino, M.N.; Pérez-Gómez, B.; Martínez-Cortés, M.; et al. Sociodemographic and Lifestyle Determinants of Adherence to Current Dietary Recommendations and Diet Quality in Middle-Aged Spanish Premenopausal Women. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 904330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amaya-Montoya, M.; Duarte-Montero, D.; Nieves-Barreto, L.D.; Montaño-Rodríguez, A.; Betancourt-Villamizar, E.C.; Salazar-Ocampo, M.P.; Mendivil, C.O. 100 YEARS OF VITAMIN D: Dietary Intake and Main Food Sources of Vitamin D and Calcium in Colombian Urban Adults. Endocr. Connect. 2021, 10, 1584–1593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Rhazi, K.; Nejjari, C.; Romaguera, D.; Feart, C.; Obtel, M.; Zidouh, A.; Bekkali, R.; Gateau, P.B. Adherence to a Mediterranean Diet in Morocco and Its Correlates: Cross-Sectional Analysis of a Sample of the Adult Moroccan Population. BMC Public Health 2012, 12, 345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shahrokhabadi, M.; Abbasnezhad, A.; Kazemnejad, A.; Ghaheri, A.; Zayeri, F. Dietary Intake of Vitamin D Pattern and Its Sociodemographic Determinants in the Southwest of Iran, Khuzestan: An Application of Marginalised Two-Part Model. Adv. Hum. Biol. 2019, 9, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabdi, S.; Boujraf, S.; Benzagmout, M. Evaluation of Rural-Urban Patterns in Dietary Intake: A Descriptive Analytical Study—Case Series. Ann. Med. Surg. 2022, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haut Commissariat au Plan du Maroc RépeRcussions de La Pandémie Covid-19 suR La Situation Économique Des Ménages.2ème panel sur l’impact du coronavirus sur la situation économique, sociale et psychologique des ménages; 2022.

- Lhilali, I.; Zouine, N.; Godderis, L.; El Midaoui, A.; El Jaafari, S.; Filali-Zegzouti, Y. Relationship between Vitamin D Insufficiency, Lipid Profile and Atherogenic Indices in Healthy Women Aged 18–50 Years. Eur. J. Investig. Health Psychol. Educ. 2024, 14, 2337–2357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Institute of Medicine (US) Committee to Review Dietary Reference Intakes for Vitamin D and Calcium. Dietary Reference Intakes for Calcium and Vitamin D; Ross, A.C., Taylor, C.L., Yaktine, A.L., Del Valle, H.B., Eds.; The National Academies Collection: Reports funded by National Institutes of Health; National Academies Press (US): Washington, DC, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Aloia, J.F.; Patel, M.; DiMaano, R.; Li-Ng, M.; Talwar, S.A.; Mikhail, M.; Pollack, S.; Yeh, J.K. Vitamin D Intake to Attain a Desired Serum 25-Hydroxyvitamin D Concentration. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2008, 87, 1952–1958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansibang, N.M.M.; Yu, M.G.Y.; Jimeno, C.A.; Lantion-Ang, F.L. Association of Sunlight Exposure with 25-Hydroxyvitamin D Levels among Working Urban Adult Filipinos. Osteoporos. Sarcopenia 2020, 6, 133–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asakura, K.; Etoh, N.; Imamura, H.; Michikawa, T.; Nakamura, T.; Takeda, Y.; Mori, S.; Nishiwaki, Y. Vitamin D Status in Japanese Adults: Relationship of Serum 25-Hydroxyvitamin D with Simultaneously Measured Dietary Vitamin D Intake and Ultraviolet Ray Exposure. Nutrients 2020, 12, 743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wortsman, J.; Matsuoka, L.Y.; Chen, T.C.; Lu, Z.; Holick, M.F. Decreased Bioavailability of Vitamin D in Obesity. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2000, 72, 690–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehdad, S.; Belghiti, H.; Zahrou, F.E.; Guerinech, H.; Mouzouni, F.Z.; El Hajjab, A.; El Berri, H.; El Ammari, L.; Benaich, S.; Benkirane, H.; et al. Vitamin D Status and Its Relationship with Obesity Indicators in Moroccan Adult Women. Nutr. Health 2022, 2601060221094376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguiar, M.; Andronis, L.; Pallan, M.; Högler, W.; Frew, E. The Economic Case for Prevention of Population Vitamin D Deficiency: A Modelling Study Using Data from England and Wales. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2020, 74, 825–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benjeddou, K.; Qandoussi, L.; Mekkaoui, B.; Rabi, B.; El Hamdouchi, A.; Raji, F.; Saeid, N.; Belghiti, H.; Elkari, K.; Aguenaou, H. Effect of Multiple Micronutrient Fortified Milk Consumption on Vitamin D Status among School-Aged Children in Rural Region of Morocco. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 2019, 44, 461–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variables | All Participants (n = 355) |

|---|---|

| Age (year). median (IQR) | 29.0(11.0) |

| Age classe (n. %) 18-25 26-36 37-49 |

90(25.4) 197(55.5) 68(19.2) |

| Education (n. %) Illiterate ≤10 years (secondary college) ≥11years (university or higher) |

64(18.0) 166(46.8) 125(35.2) |

| Marital status (n. %) Married Unmarried |

227(63.9) 128(36.1) |

| Employment (n. %) Yes No |

157(44.2) 198(55.8) |

| Localization (n. %) Urban Rural |

239(67.3) 116(32.7) |

| Vitamin D intake (µg/day) Mean (SD) Median (IQR) |

3.63(2.73) 2.87(2.76) |

| Intake adequacy (WHO/FAO RI) (n.%) Adequate (≥5µg/day) Low (<5µg/day) |

70 (19.72) 285 (88.28) |

| BMI (Kg/m2) Normal weight Underweight Overweight Obese |

25.7(6.2) 145 (40.8) 5(1.4) 133(37.5) 72(20.3) |

| 25(OH)D (ng/ml) Mean (SD) Median (IQR) |

18.2(9.4) 15.7(12.4) |

| VD deficiency (25(OH)D<20ng.ml) VD Insufficiency (20≤25(OH)D<30ng/ml) VD Sufficiency (25(OH)D≥30ng/ml) |

231(65.1) 82(23.1) 42(11.8) |

| Sun exposure score Median (IQR) | 15.9(10.5) |

| Sun exposure categories (n.%) Insufficient-moderate Sufficient-high |

156 (43.9) 199(56.1) |

| Physical activity MET min/week, Median (IQR) Physical activity level categories (n.%) Moderate-low High |

1778.2(1765.0) 330(93.2) 24(6.8) |

| Season (n.%) Summer Autumn Winter Spring |

143(40.9) 86(24.2) 60(16.9) 66(18.6) |

| Food sources | Items | Never or less than once per month | 1-3 times per month | 1time per Week | 2-4 days per week | 5-6 days per week | Every day |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fish and sea products | Fatty fish fresh and frozen (Sardin) | 18.76 | 54.2 | 27.04 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Fatty fish fresh and frozen (Mackerel) | 87.32 | 8.16 | 4.52 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| White fish fresh and frozen (sole, whiting, sea bream…) | 85.35 | 0 | 12.39 | 2.26 | 0 | 0 | |

| Sardine, canned in tomato sauce | 42.83 | 50.98 | 6.19 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Tuna and mackerel, canned in vegetable oil | 87.32 | 12.68 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Shellfish (calmer, scampi. Shrimps, mussels) | 91.54 | 8.46 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Meat products | Red meat (Beef, veal. sheep...,), eaten with or without fat | 43.66 | 20.56 | 14.36 | 16.61 | 4.81 | 0 |

| Organ meats (kidney) | 93.53 | 4.22 | 2.25 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Organ meats (liver) | 81.14 | 16.61 | 2.25 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Poultry (chicken and turkey) | 14.36 | 6.19 | 45.53 | 22.53 | 12.38 | 0 | |

| Smoked meats or charcuterie (chorizo, salami, Ham, casheer, mortadella. etc.) | 84.79 | 8.45 | 3.50 | 3.26 | 0 | 0 | |

| Entire eggs | Eggs (Pan-fried, crambled and boiled) | 38.6 | 18.6 | 28.16 | 4.22 | 10.42 | 0 |

| Dairy Products and beverages | Cow milk vitamin D fortified. farm-fresh cow’s milk | 12.4 | 0 | 2.25 | 24.5 | 20.85 | 40 |

| Milk drink. or drinking yogurt. flavored or with fruit. sweetened | 52.11 | 25.07 | 18.58 | 1.97 | 2.27 | 0 | |

| Yogurt flavored or with fruit. sweetened. non-reduced fat | 25.07 | 22.25 | 27.04 | 18.6 | 7.04 | 0 | |

| Semi-hard cheese (Gouda. Edam. Munster) | 81.12 | 8.16 | 8.16 | 2.56 | 0 | 0 | |

| Fresh cheese (ricotta. Mozarelle.) | 95.8 | 4.2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Soft cheese (Camembert. Brie) | 87.6 | 4.22 | 6.47 | 1.71 | 0 | 0 | |

| Melted cheese in portions or spreadable cubes | 0 | 22.81 | 25.07 | 4.22 | 29.28 | 18.62 | |

| Cottage cheese natural or aromatic | 93.8 | 2.25 | 2.25 | 0 | 1.7 | 0 | |

| Fat Products | Vegetable oil vitamin D fortified | 22.82 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 77.18 |

| Margarine vitamin D fortified | 45.63 | 0 | 4.22 | 24.78 | 4.22 | 21.15 | |

| Butter | 42.81 | 4.22 | 2.25 | 22.81 | 4.22 | 23. 66 | |

| Breakfast cereals | Cereal vitamin D fortified | 87.32 | 6.19 | 6.49 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Chocolate | chocolate bars (with milk or dark 70% cocoa minimum or with dried fruits) | 66.47 | 14.64 | 10.42 | 4.22 | 4.25 | 0 |

| Cacao | Sweet cocoa or chocolate powder for drinks, enriched with vitamins and minerals | 87.32 | 0 | 8.16 | 4.52 | 0 | 0 |

| Backery and Moroccan biscuit | Ordinary homemade cake or prepackaged Madeleine. Viennoiserie (krachel. chocolate bread, raisin bread, croissant. brioche) Moroccan biscuits (thee dry biscuit, Fekkas, date biscuit) |

18.87 |

10.42 |

41.7 |

6.47 |

22.54 |

0 |

| Characteristics | Dietary intake (µg/d) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | Median(IQR) | P value | Below RI (n, %) |

P Value d | |

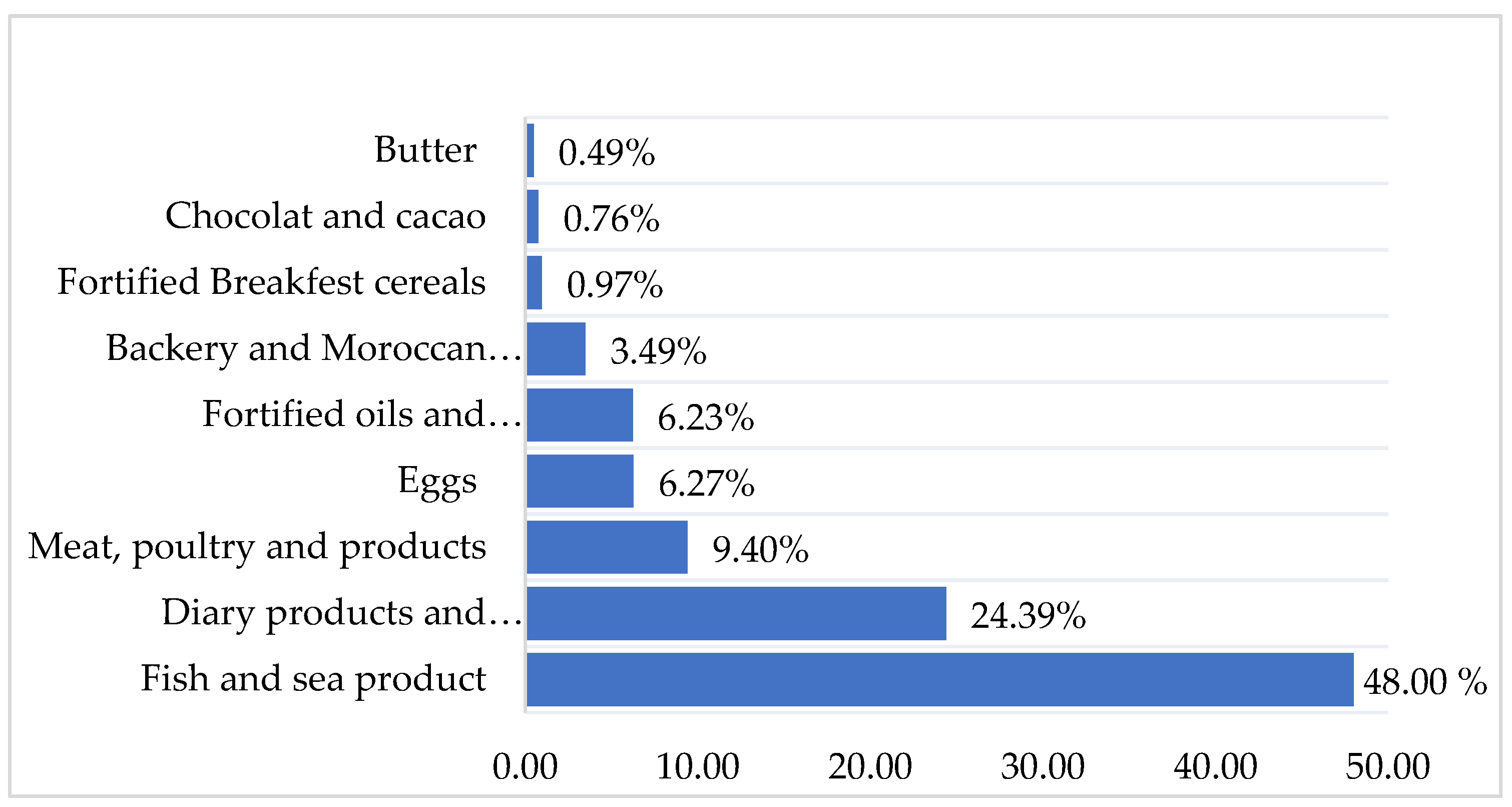

| Age (years) | 0.004a | ||||

| Age classes (n. %) 18-25 26-36 37-49 |

3. 32(2.58) 3.58(2.73) 4.16(2.84) |

2.62(2.30) 2.79(2.68) 3.67(3.25) |

0.029b 0.027C |

67(23.50) 160(56.10) 58(20.40) |

0.146 |

| Education (%) Illiterate ≤10 years (Secondary -college) ≥11years (University or higher) |

3.70(3.39) 3.86(2.84) 3.28(2.11) |

2.79(2.92) 2.93(2.11) 2.87(2.64) |

0.351 | 53(18.60) 125(43.90) 103(37.50) |

0.219 |

| Marital status Married Unmarried |

3.73(2.85) 3.44(2.48) |

2.93(2.84) 2.63(2.73) |

0.471 | 177(62.1) 108(37.9) |

0.219 |

| Employment (%) Yes No |

3.57(2.57) 3.67(2.84) |

2.82(2.83) 2.93(2.75) |

0.982 | 122(42.80) 163(57.20) |

0.278 |

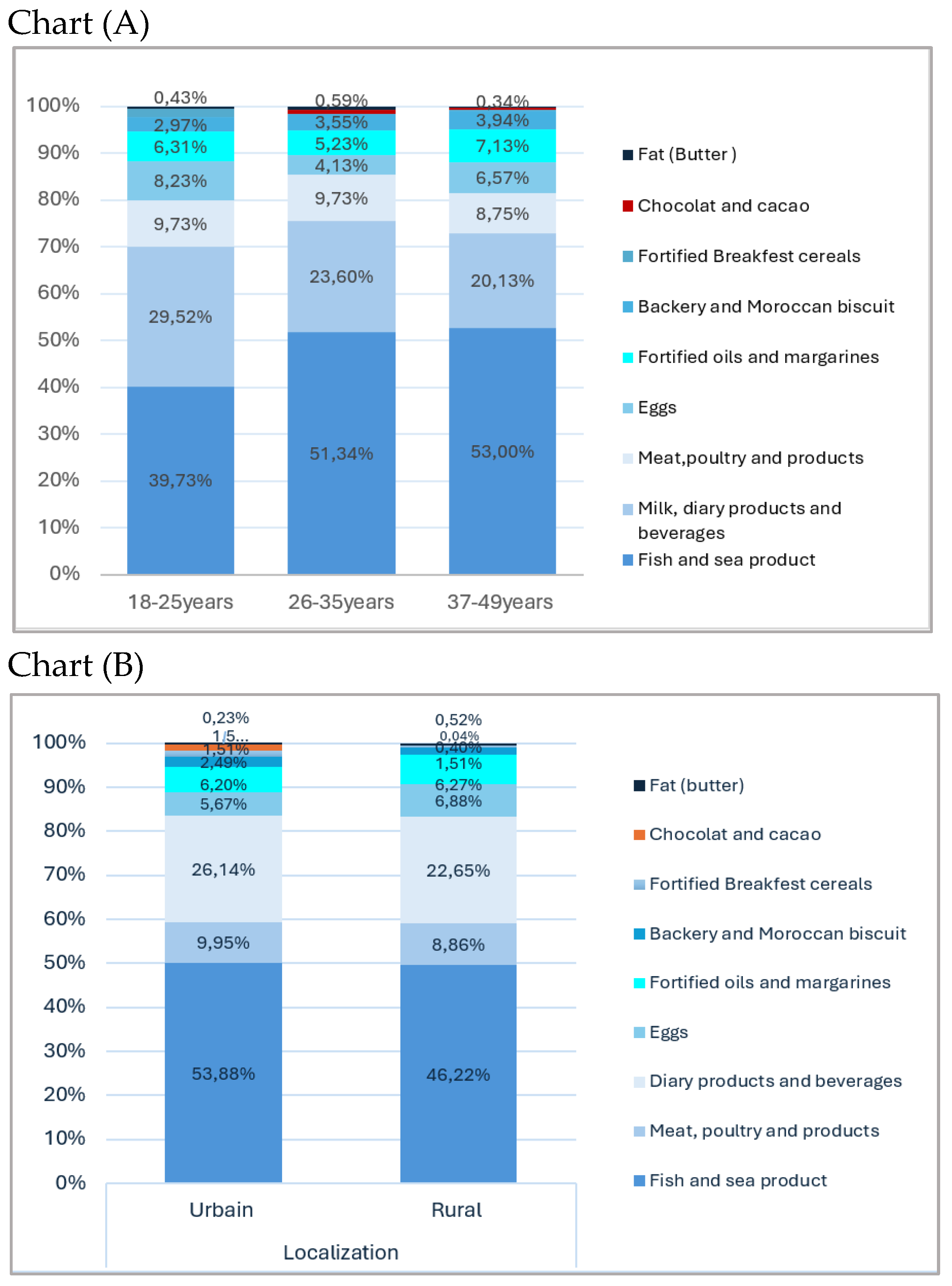

| Localization Rural Urban |

3.27(2.33) 4.25(3.22) |

2.73(2.46) 3.18(3.93) |

0.014 b | 193(67.70) 92(32.30) |

0.204 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).