1. Introduction

The detection of drivable areas (DA) is a fundamental and indispensable component in the development of autonomous vehicle technology. Autonomous vehicles in the road (called ego-vehicle) rely on their ability to perceive and understand their surroundings to safely navigate through complex environments. The primary function of DA detection is to identify safe zones on the road that are free of obstacles, ensuring reliable navigation, path planning, and decision-making. This capability becomes particularly crucial in dynamic driving scenarios involving varying weather conditions, unpredictable traffic situations, and diverse road geometries. Accurate DA detection is essential for avoiding collisions, maintaining lane discipline, and executing safe maneuvers in both urban and highway settings.

Traditional methods for DA detection have predominantly relied on camera-based systems that use image data to identify drivable regions [

1,

2,

3]. While cameras provide rich color and texture information, they suffer from several limitations that impede their effectiveness in real-world scenarios. One significant challenge is their performance degradation under adverse lighting conditions, such as low light, shadows, glare, and nighttime driving [

4]. Additionally, camera-based approaches often project images onto a Bird’s Eye View (BEV) map for a better understanding of the spatial layout [

2]. However, this projection process can introduce distortions, especially near the image’s vanishing point, leading to inaccuracies in DA localization. Such distortions become more pronounced in environments with irregular lighting, wet road surfaces, or complex shadows, compromising the reliability of camera-based DA detection [

4,

5].

To overcome the limitations of camera-based methods, LiDAR (Light Detection and Ranging) has been increasingly utilized for DA detection. LiDAR systems generate precise 3D point clouds that represent the vehicle’s surroundings, offering significant advantages such as robustness against varying lighting conditions and the elimination of projection distortions associated with BEV maps [

6]. LiDAR’s ability to provide accurate depth information makes it well-suited for detecting obstacles and defining road boundaries in challenging scenarios. Despite these advantages, current LiDAR-based DA detection techniques are predominantly based on point-wise segmentation methods. These methods, however, struggle to perform effectively in highly complex environments where road boundaries may be obscured or occluded by objects such as vehicles, pedestrians, or vegetation. The point-wise segmentation often lacks the global context needed for coherent DA detection in such cases, limiting its practical utility.

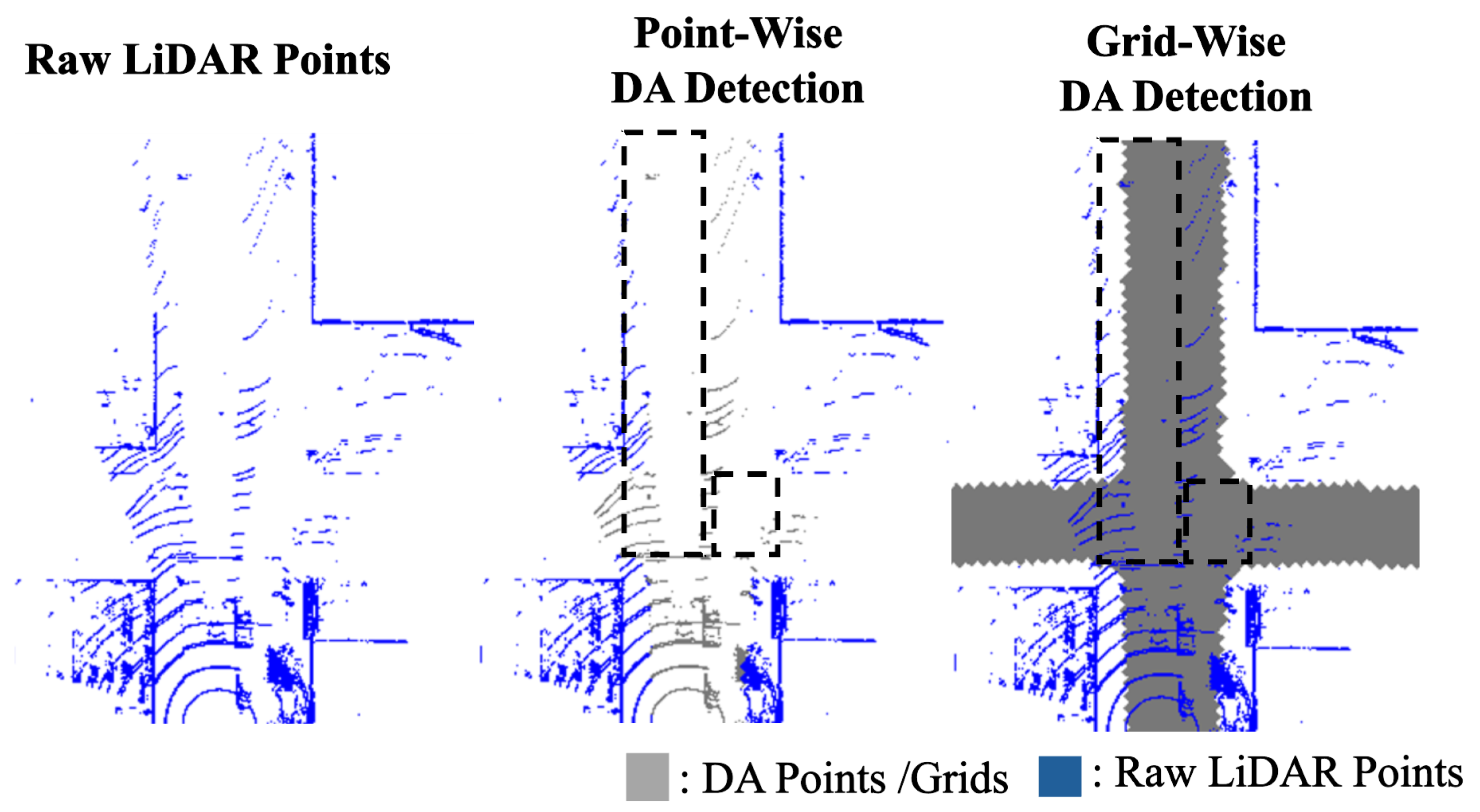

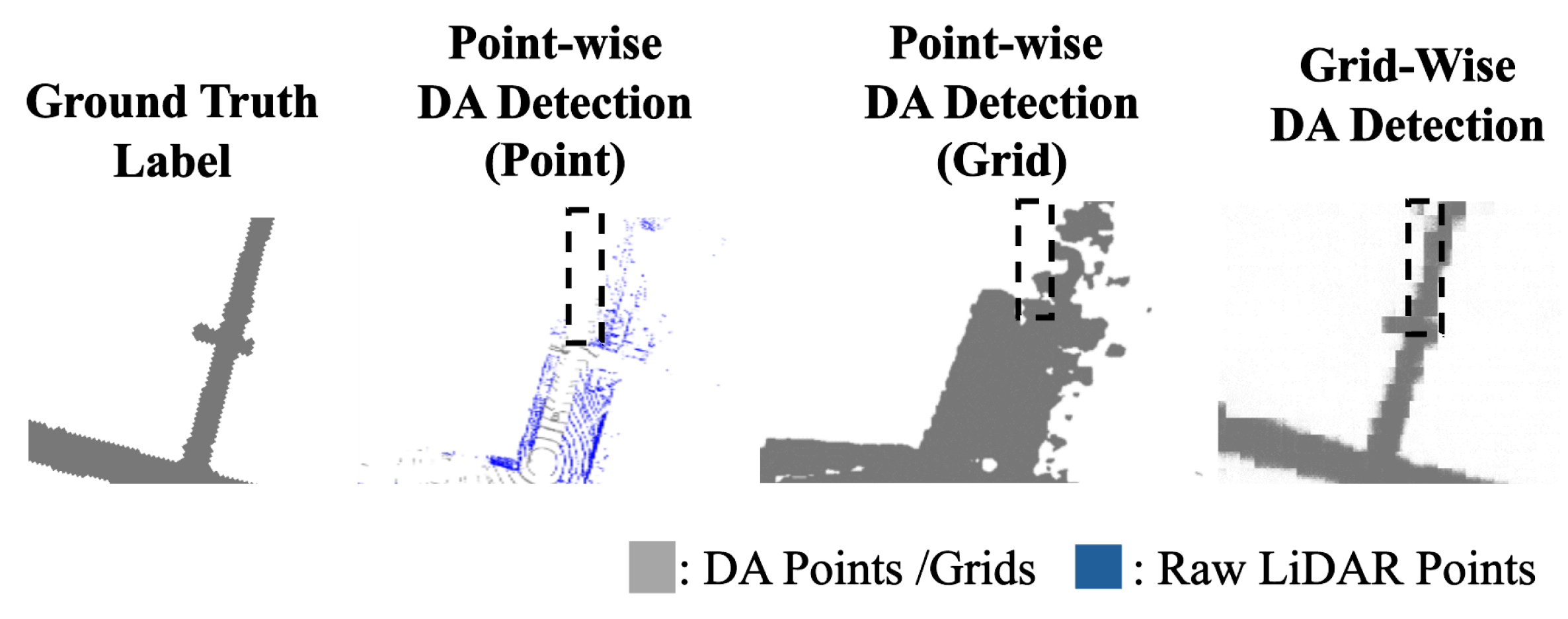

Given the limitations of both camera-based and LiDAR-based approaches, there is a need for more advanced DA detection methods that can provide comprehensive and accurate coverage of the entire driving environment. To address these challenges, we propose a novel grid-wise DA detection approach that extends beyond the point-wise segmentation paradigm. Our method involves dividing the BEV map into a grid and detecting DA at the grid level, thereby covering all regions and enhancing the robustness of DA detection, as illustrated in

Figure 1. This grid-wise approach provides a more holistic view of the drivable space and is better suited for handling occlusions and complex road geometries. However, the advancement of grid-wise DA detection has been hindered by the lack of large-scale open-source datasets with appropriate grid-wise labels, which are essential for training and benchmarking deep learning models.

To address the dataset gap and enable rigorous benchmarking of grid-wise DA detection methods, we generate training labels directly from the Argoverse dataset [

7], leveraging its multimodal data and Rasterized Road Map. By utilizing these rich data sources, we create a diverse training dataset specifically tailored for grid-wise DA detection, which we call Argoverse-grid. This new dataset includes high-resolution BEV maps with detailed annotations and accurate calibration parameters, providing a comprehensive foundation for developing and evaluating DA detection algorithms.

Our objective is to develop a technology that significantly improves the precision and recall of road detection compared to existing methods. The grid-wise approach, facilitated by Argoverse-grid, holds substantial promise for enhancing the accuracy and reliability of DA detection. This improvement is pivotal for ensuring the safety and efficiency of autonomous driving systems in real-world scenarios.

In this paper, we introduce Argoverse-grid, the first large-scale dataset specifically designed for grid-wise DA detection, derived from the original Argoverse dataset. Argoverse-grid is characterized by detailed DA maps and precise calibration data, which are crucial for accurate DA detection. In addition, we propose Grid-DATrNet, a novel deep learning model designed as a baseline for grid-wise DA detection. Grid-DATrNet leverages transformer architecture with global attention mechanisms, enabling it to effectively capture both contextual and semantic information necessary for accurate DA detection, especially in far-field regions. We demonstrate that Grid-DATrNet achieves superior performance compared to existing camera-based or LiDAR-based DA detection methods, thereby establishing a new benchmark for the field.

In summary, the key contributions of this paper are as follows:

A novel DA detection scheme termed grid-wise DA detection, which enhances the robustness and accuracy of DA detection across varied driving environments.

Argoverse-grid, a newly proposed large-scale dataset specifically curated for training and benchmarking grid-wise DA detection models.

A Grid-wise DA detection network, termed Grid-DATrNet, that utilizes global attention mechanisms to detect DAs effectively, especially in distant regions where conventional methods often falter.

This paper is organized as follows.

Section 2 provides a comprehensive overview of related work and situates our study within the broader context of DA detection research.

Section 3 details the Argoverse-grid dataset and introduces our proposed baseline model, Grid-DATrNet. In

Section 4, we present the experimental setup and the results obtained. Finally, we conclude our findings and discuss future directions in

Section 5.

2. Related Works

2.1. Camera-Based DA Detection

Early methods for DA (DA) detection in autonomous vehicles relied on heuristic techniques applied to camera images. These methods, including edge detection, lane detection, and vanishing point analysis, often struggled in challenging scenarios due to their reliance on handcrafted rules. With the rise of deep learning, there has been a shift towards using Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) for DA detection, treating it as a semantic segmentation task [

1,

8,

9,

10]. Notable models include ENet [

11], HDCNet [

12], PPNet [

13], and ESPNet [

14], which have improved performance by effectively capturing contextual information from images using various architectures and techniques such as dilated convolutions and spatial pyramid pooling. While HDMapNet [

5] using multi-view cameras to detect DA edge for generating online map using CNN. Attention mechanisms have also been incorporated to enhance feature encoding, resulting in models like Dual Attention Modules [

15], YOLO Panoptic [

16], and TwinLiteNet [

17], which excel in capturing semantic information for DA detection.Lately, some attention-based architectures, such as VectorMapNet [

3] and MapTrNet [

4], have been used for predicting DA edge detection using multiple cameras to detect the map around autonomous vehicles. Some approaches also use temporal multi-camera systems to achieve more accurate DA (DA) edge detection, such as StreamMapNet [

18], but these require significant computation as they need to process features from multiple camera frames. Some research efforts have also explored predicting DA edge detection using multi-camera systems with Bezier Curve representation [

19] [

20] or Douglas-Peucker point representation [

21] [

22].However, predicting DA edges as vectors does not provide information on whether there are objects on the road, and it also requires considerable computation. Other methods attempt to predict DA using multi-view cameras and a prior known city map [

23]. Despite significant advancements in multi-camera DA (DA) detection research, current methods still struggle to predict DA accurately in poor lighting conditions and in distant areas [

24].

2.2. Point-Wise DA Detection

While advancements in camera-based DA detection [

17] have made significant progress, these methods still rely on BEV (Bird’s-Eye View) projection, which can introduce distortion in the resulting DA. This distortion limits the range for motion planning, as shorter distances are required to ensure reliable navigation [

25]. Moreover, camera sensors are sensitive to conditions like low light or strong glare [

26]. As a result, LiDAR has become a promising alternative for accurately detecting DAs in 3D space. One common method for LiDAR-based DA detection is point-wise detection, where the system determines whether each LiDAR point corresponds to a DA or not.

Initially, researchers attempted to use heuristic methods for DA detection using LiDAR. For instance, [

27] introduced an angular method to detect whether the DA and obstacles are on the road. [

28] proposed DA detection by employing linear regression to minimize the standard deviation of road height and obstacle height. However, heuristic-based DA detection performs robustly under normal and sparse road conditions but poorly in complex situations such as occlusions, traffic jams, and construction. Therefore, DL-based DA detection emerged as it did for camera-based methods.

[

6] is a pioneering point-wise DA detection method that utilizes PointPillars [

29] on LiDAR data and processes pillar features with CNNs to capture global features of LiDAR points and predict whether a LiDAR point corresponds to the DA or not. Some researchers have also proposed methods to combine camera images and LiDAR points for DA detection. Nagy et al. utilized LiDAR as an additional sensor with a camera for DA detection by using LiDAR points as guidance for DA segmentation in the camera with low confidence scores [

30]. Similarly, Raguraman et al. proposed DA detection using LiDAR when DA detection using camera images fails to identify any ego lane [

31]. Meanwhile, Lele Wang et al. introduced a novel DA detection method using both LiDAR and camera by combining predictions from camera-based DA detection and LiDAR-based DA detection using the Conditional Random Field method [

32].

2.3. Grid-Wise DA Detection

In contrast with point-wise DA (DA) detection, grid-wise DA detection divides the area surrounding the autonomous vehicle into grid cells and performs detection on each cell in a Bird’s Eye View (BEV) perspective. BEV is a top-down view of the environment around the vehicle, providing a more intuitive representation for navigation and planning tasks. Hanzhang Xue et al. proposed a method for detecting grid-wise DA around autonomous vehicles using predefined ground height and employing a Bayesian Gaussian Kernel method to predict whether a grid cell is a DA or not [

33]. The LoDNN model stands as one of the pioneers of LiDAR-based grid-wise DA detection, utilizing the BEV map of LiDAR points and a simple CNN architecture [

34].

Nagy et al. introduced a method to convert 3D LiDAR data into 2D panoramic data and employed a U-Net backbone [

35] or SegNet backbone [

36] to capture local and global semantic information [

30]. However, the performance of this method diminishes significantly when the road is distant from the autonomous vehicle. Zhong et al. proposed LRTI by converting LiDAR points into a BEV image containing texture, height, intensity, and a fusion of texture and height to detect DA using the Mask R-CNN architecture [

25]. They improved the accuracy of DA detection by combining the predictions from multiple LiDAR frames, taking advantage of the temporal consistency of the DA.

Some methods utilize more than one LiDAR frame to detect DA, as the DA around the autonomous vehicle remains largely unchanged over short periods. BEVNet, for example, proposes detecting DA using multiple LiDAR point frames by extracting features of LiDAR frames using sparse 3D convolution [

37] and extracting temporal information from LiDAR point features [

33].

Despite the plethora of proposed methods for DA detection using LiDAR, each validated on different datasets, researchers face challenges in comparing the performance of their methods due to the lack of a unified and open-source benchmark grid-wise DA dataset. This highlights the need for standardized datasets to facilitate fair comparisons and drive further advancements in the field.

3. Methods

3.1. Argoverse-Grid

As discussed earlier Argoverse 1 dataset is one of the biggest autonomous vehicle dataset initially specialized for 3D object detection, object tracking and motion forecasting [

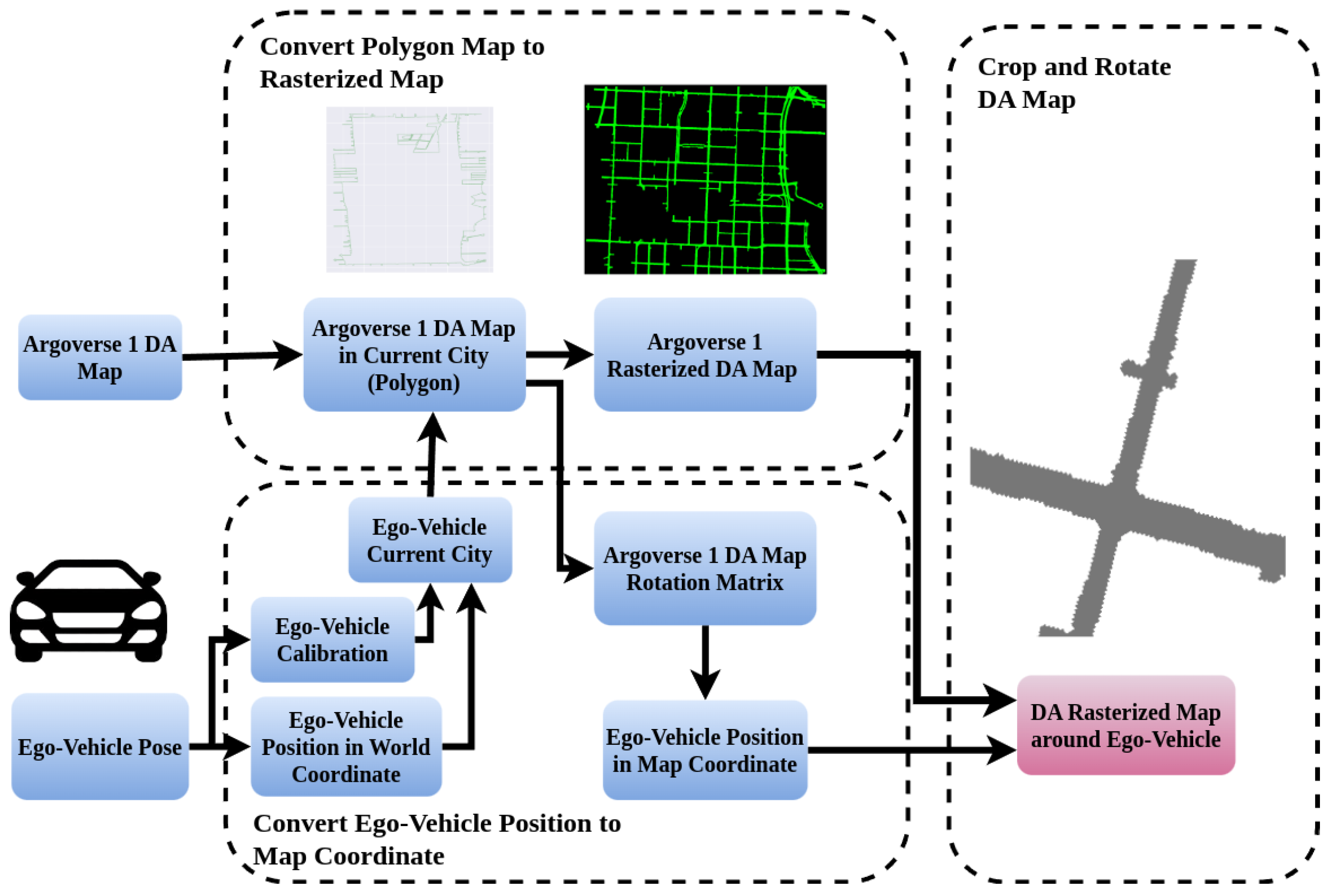

7]. Argoverse 1 dataset is taken in 2 cities : Miami and Pittsburgh and contains DA map for both cities. Argoverse 1 dataset DA map is provided in polygon files where line is the edge of DA. Argoverse 1 dataset also contains calibration file for each of the LiDAR frame and camera image in the dataset that ensure accurate location and time of both LiDAR frames and camera images. Hence we proposed to make first big-scale open- source BEV grid- wise DA detection using Argoverse 1 dataset and its HD Maps by leveraging ego-vehicle position in Argoverse 1 dataset. The complete process of converting the Argoverse 1 dataset into a grid-wise DA detection dataset Argoverse-Grid is illustrated in

Figure 2. This process involves the following three steps:

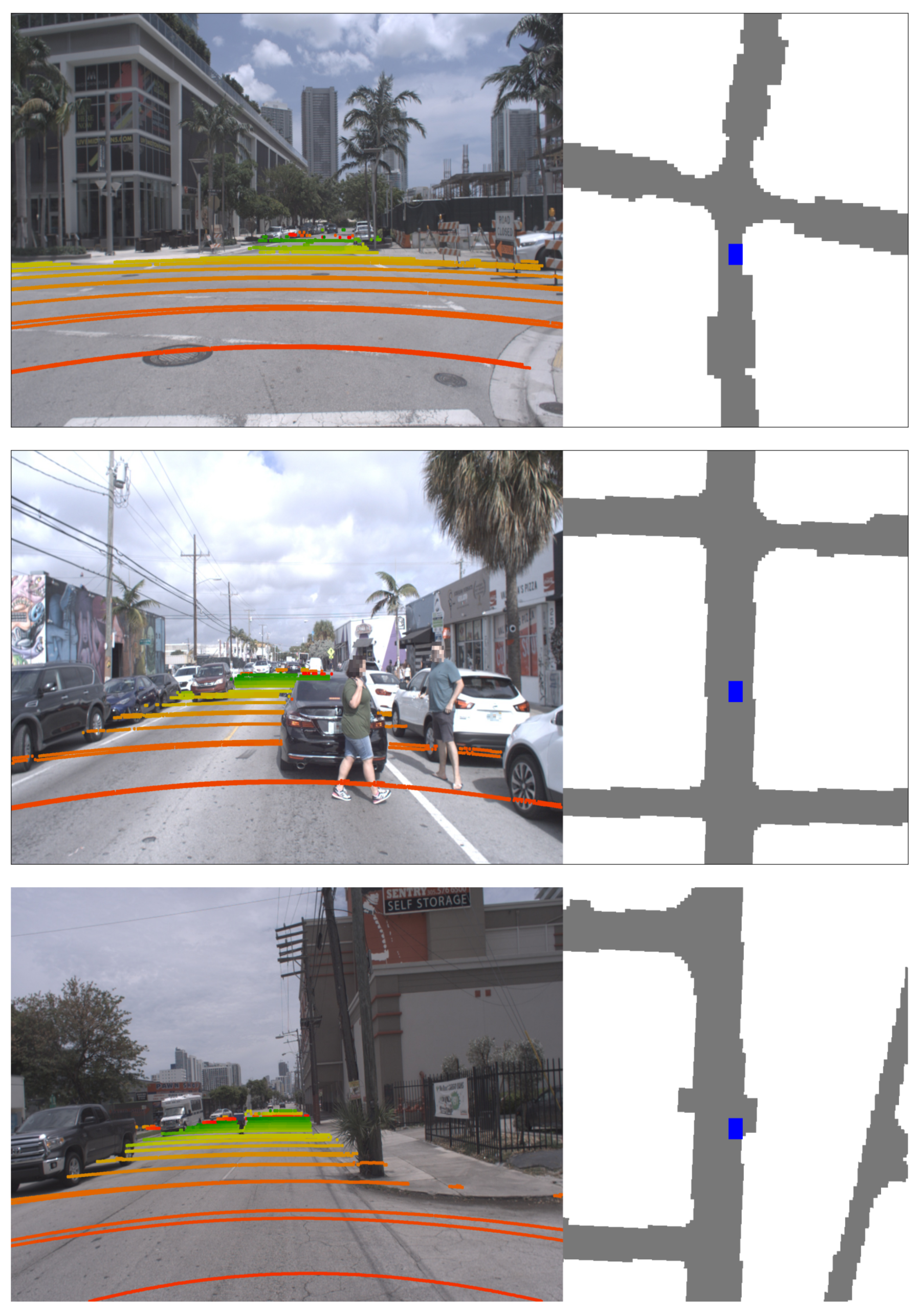

Convert Polygon Map to Rasterized Map: Since the Argoverse 1 dataset provides DA maps as polygon files, we need to convert the Drivable Area (DA) map from polygon files into a rasterized map. The process involves labeling all grids between the polygon lines, which represent the edge of the DA, as DA grid, and labeling the area outside the polygon lines as non-DA grid. The results of converting polygons into rasterized DA map can be seen in the

Figure 3.

-

Convert Ego-Vehicle Position to Ego-Vehicle Position in DA Map Coordinate: Next, we need to convert the ego-vehicle position from world coordinates into map coordinates and measure the yaw orientation of the ego-vehicle in DA map coordinates. This transformation process is achieved by using the translation and rotation matrix information in the Argoverse 1 dataset calibration files. The process of transforming the ego-vehicle position to the ego-vehicle coordinate in the DA map can be described as follows:

Here,

represents the ego-vehicle position in the DA map coordinate,

represents the ego-vehicle position in world coordinates,

represents the rotation matrix from ego-vehicle position to DA map position, and

represents the translation matrix from ego-vehicle position to DA map position. The yaw orientation of the ego-vehicle in DA map coordinates can be extracted using a basic rotation matrix to yaw orientation transformation as follows:

Here, represents the ego-vehicle position in world coordinates to DA map coordinate column 0 row 0, and represents the ego-vehicle position in world coordinates column 0 row 1.

-

Crop and Rotate DA Map Around Ego-Vehicle: Finally, we need to crop the DA map around the ego-vehicle based on the ego-vehicle coordinate in the DA map. The process of rotating and cropping the DA map around the ego-vehicle can be described as follows:

Here, represents the whole DA rasterized map in the ego-vehicle city, is a function that rotates the DA map by an angle in the counterclockwise direction, and is a function that crops the DA map at . Since the Argoverse dataset doesn’t provide the angle rotation offset from ego-vehicle world coordinates to DA map coordinates, we adjusted the value of to find the angle offset that makes the DA label around the ego-vehicle have an upward orientation. The value of we found is approximately .

The processed DA map label results in a fine-grained DA map label with a grid size of 1 m × 1 m. We conducted quality checks on the processed DA map label across the entire Argoverse 1 train and test dataset. An example of the result of the DA map label can be seen in

Figure 3.

3.2. Metrics Evaluation

To evaluate DA detection in the Argoverse 1 dataset, we propose using the a F1 score as the main evaluation metric. This choice is motivated by the fact that the cost of predicting a DA as non-drivable (false negative) is far more severe than predicting a non-DA as drivable, as the former can significantly affect the planning system of the autonomous vehicle and decrease its performance.

If the output of the DA detection is a probability array

, representing the likelihood of each grid in the BEV map being a DA (ranging from 1 to 0), we can convert the DA detection prediction into binary prediction (

) using a probability threshold

, where

, as follows:

We can then calculate the F1 score of the DA detection as follows:

Where represents true positives (the number of DA grids predicted as DA), represents false positives (the number of non-DA grids predicted as DA), and represents false negatives (the number of DA grids predicted as non-DA grids).

3.3. Proposed Network: Grid-DATrNet

To address DA detection using LiDAR point clouds, we introduce

Grid-DATrNet (Grid-wise DA Transformer Network), designed to predict DAs around autonomous vehicles. Motivated by the growing use of attention mechanisms in Transformer networks [

38] for analyzing feature correlations in computer vision, we leverage attention-based Transformers to establish correlations between areas in a BEV map and predict DA detection around autonomous vehicles. The end-to-end architecture of Grid-DATrNet is illustrated in

Figure 4.

BEV Encoding: Initially, LiDAR point cloud data is encoded into a 2D BEV tensor, representing geometric information, using a deep learning-based or statistical-based model. We primarily employ the fast encoder PointPillars [

29] due to its efficient detection of geometric and semantic information from point clouds. We also experiment with the point projector encoder [

39,

40], which projects point clouds onto a BEV map grid and utilizes CNNs to extract features. However, due to its longer processing time and higher computational demand, we favor PointPillars for real-time DA detection. Our experiments demonstrate that using the point projector does not significantly enhance performance compared to PointPillars. The output is a BEV map sized

representing the region of interest (ROI) of the processed LiDAR point cloud.

Apart from deep learning-based approaches, we explore statistic-based models for BEV encoding. These models utilize statistical point cloud data (e.g., average point coordinates, minimum point height) to generate a BEV tensor swiftly with minimal computation. However, our experiments indicate that statistic-based approaches perform notably worse than deep learning-based BEV encoders.

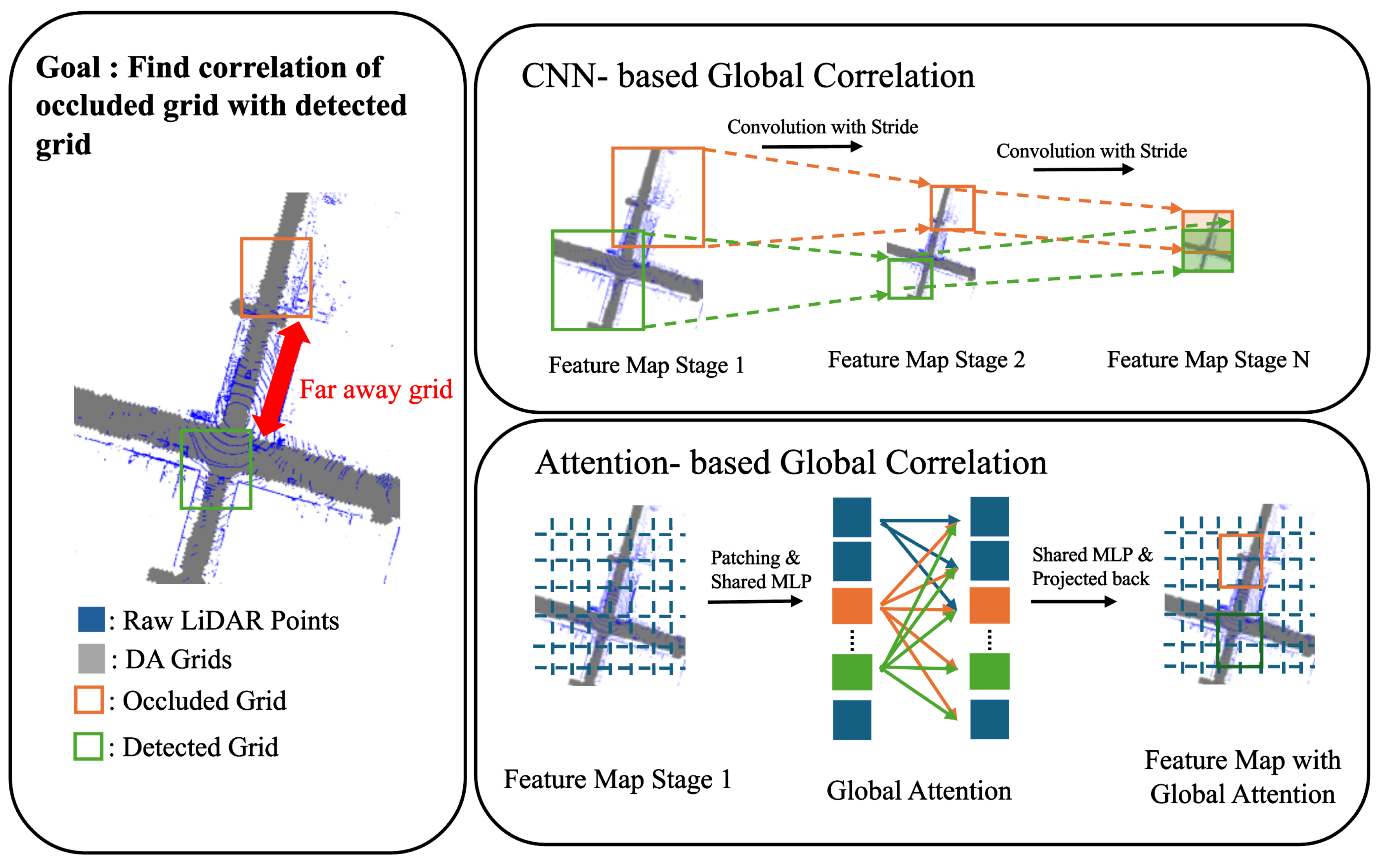

Global ttention using Transformer: Given the challenges of grid-wise DA detection due to LiDAR occlusions and surrounding obstacles, we employ a global attention mechanism based on Transformers. Inspired by recent work on attention mechanisms in computer vision [

38] and Global Feature Correlators (GFC) in LiDAR-based lane detection [

26], our global attention Transformer identifies correlations between patches in the BEV map, aiding in DA prediction even in occluded regions without point cloud data. The BEV tensor is divided into

patches, each flattened into a tensor

of dimensions

. We then compute patch correlations using a Transformer-based mechanism [

41]. Explanation of using global attention and CNN to find spatial features and semantic features of DA around ego-vehicle can be seen in

Figure 5.

We iterate the attention mechanism multiple times to capture global correlations in the BEV map, preparing the data for the grid-wise detection head. We also encode the position of location-wise BEV feature map patch by using usual learnable position encoding inspired by Visual Transformer [

41].

Grid-Wise Detection Head and Loss Function: The detection head of Grid-DATrNet consists of convolutional layers (CNNs) with downsampling and upsampling operations, accompanied by batch normalization , ReLU activation functions and fully connected layers , treating DA prediction as a segmentation problem. For each grid in the BEV map, we predict whether it represents a DA (1) or not (0). This grid-wise detection head follows an encoder-decoder architecture leveraging CNN layers and non-linear activations to learn significant BEV features, benefiting from the global attention mechanism to capture feature correlations across neighboring grids. The output of the grid-wise detection head is a BEV grid matching the ROI of the DA.

Given the critical importance of correctly identifying DAs (i.e., minimizing false negatives), we use focal loss [

42] to train Grid-DATrNet. This approach addresses class imbalance in BEV labels (typically containing more non-DA grids than DA grids), encouraging the model to prioritize DA predictions and mitigate the imbalance issue. To enhance the detection of DA edges and ensure DA presence in neighboring areas, we propose training Grid-DATrNet using

Spatial L2 Loss. Inspired by [

6], Spatial L2 Loss enables Grid-DATrNet to predict DA around the ego-vehicle within a specific spatial area and accurately identify DA edges. The formula for Spatial L2 Loss is as follows:

Here, represents the ground truth DA (DA) BEV at row i and column j, and is the DA prediction of Grid-DATrNet for the corresponding grid. The term N denotes the total number of grids in the DA BEV map. Therefore, the final loss is a weighted combination of focal loss and Spatial L2 Loss, where the weights for each loss component are chosen based on the specific requirements of the DA detection task. For instance, to prioritize accurate DA predictions over non-DA areas, the weight for focal loss would be higher, whereas a higher weight for Spatial L2 Loss would emphasize accurate DA edge detection.

4. Experiment and Discussion

In this section, we present a detailed description of the experimental setup and results obtained from grid-wise DA detection using LiDAR trained on the Argoverse-grid dataset. We compare the proposed DA detection model, Grid-DATrNet, with other widely-used methods for DA detection employing different modalities.

4.1. Experiment Setup

For the baseline comparison, we evaluated Grid-DATrNet against state-of-the-art DA detection methods from various modalities, including camera-based DA detection, heuristic-based grid-wise DA detection, and point-wise DA detection.

Camera-based DA Detection: We utilized the TwinLiteNet model [

17], originally designed for DA and lane detection using images and MapTrNet model [

4] that originally used to detect DA edge detection using multi-cameras. The DAs detected in all 7 images from the Argoverse-grid dataset from TwinLiteNet model were projected onto the BEV map using calibration information while MapTrNet predicted from 7 cameras input.

Heuristic-based Grid-wise DA Detection: Grid-wise DA detection using Gaussian Bayesian Kernel [

31] was used to assess the performance of Grid-DATrNet compared to rule-based detection.

Point-wise DA Detection: Comparison was also made with point-wise DA detection as proposed in GndNet [

6], a state-of-the-art LiDAR-based method for DA detection.

Additionally, we experimented with various configurations of BEV encoders (e.g., PointPillar, point projection) and backbones (e.g., global attention, MLP Mixer) for feature extraction to benchmark the performance of Grid-DATrNet against other state-of-the-art methods. We evaluated the proposed method within a default Region of Interest (ROI) of , emphasizing predictions of DAs ahead of the ego-vehicle for planning and object detection purposes. We trained the all the models in Argoverse-Grid dataset processed form Argoverse 1 Dataset training data of more than LiDAR frames and test in the Argoverse 1 Dataset testing data of more than LiDAR frames. Additionally, we analyzed the impact of different ROI settings on the method’s performance. We trained all the models in data of Argoverse-grid to make training and experiment time faster.

4.2. Implementation Details

Our network training on the Argoverse-grid dataset was conducted over 35 epochs using RTX3070 GPUs, employing the Adam optimizer with a batch size of 4 and a learning rate of 0.0002. The training and evaluation processes were implemented using PyTorch version 2.0.0 on a machine running Ubuntu 18.04. We used loss weight of 1 for focal loss weight and Spatial L2 Loss weight.

4.3. Comparison with Heuristic DA Detection using LiDAR

In this experiment, we compared the performance of Grid-DATrNet using different BEV encoders (PointPillar, point projection) and backbones (global attention, MLP Mixer). The quantitative results are presented in

Table 1. Grid-DATrNet achieved significantly higher accuracy (97.3%) and F1-score (0.952) with the PointPillar encoder and global attention feature extractor compared to the heuristic-based DA detection method [

31] (accuracy 82.33%, F1-score 0.6255). The heuristic method relies solely on the height of LiDAR points around grid BEV, whereas Grid-DATrNet leverages contextual and semantic information from the point cloud. Additionally, Grid-DATrNet demonstrated faster inference times, benefiting from deep learning techniques accelerated by GPU.

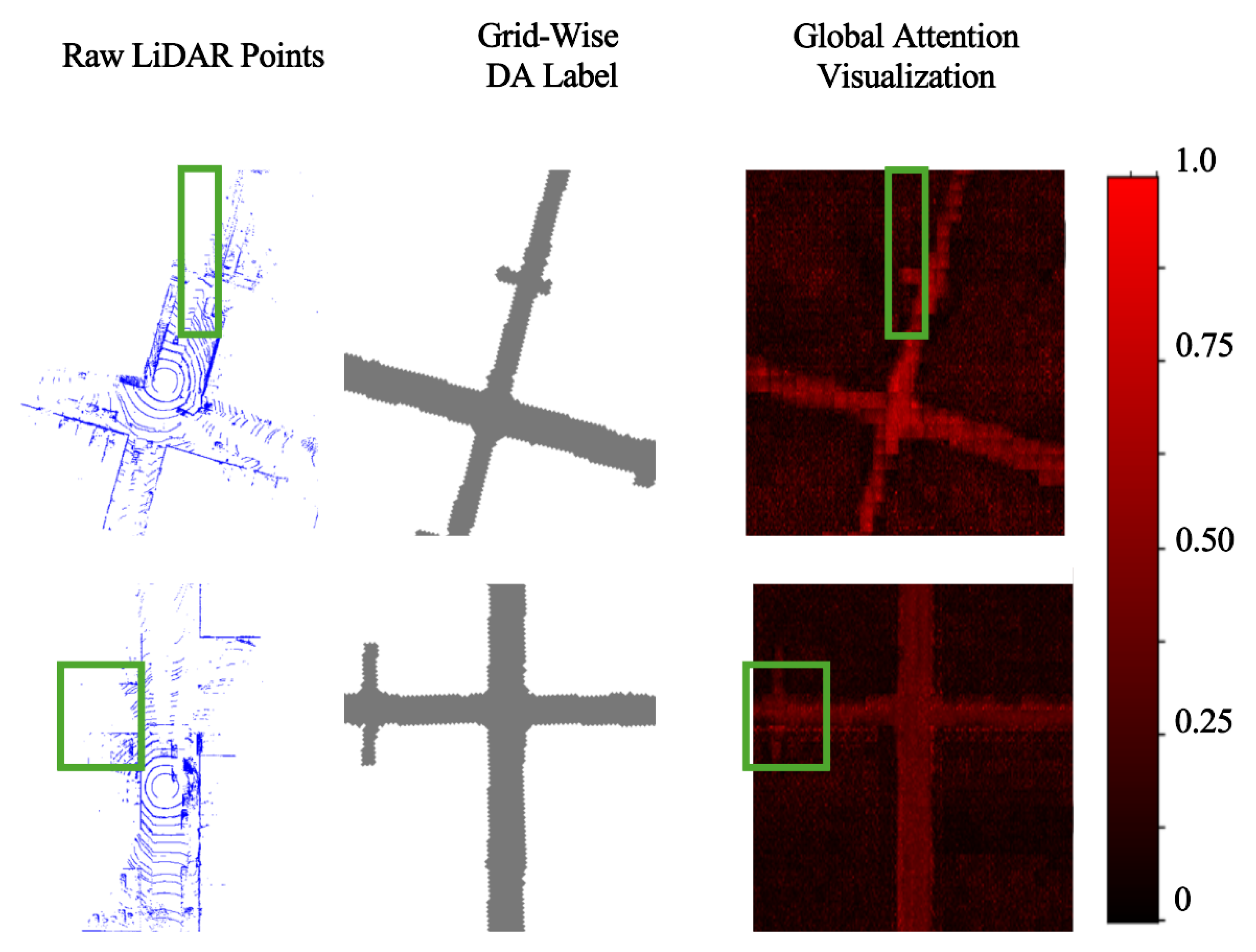

4.4. Comparison of Grid-DATrNet using Various BEV Encoders and Feature Extractors

Next, we compared the performance of the proposed method Grid-DATrNet using various BEV encoders and feature extractors. We observed a slight improvement in DA detection performance when using the point projection BEV encoder compared to the PointPillar encoder, with both global feature extractors. This can be explained by the point projection BEV encoder employing a more complex CNN and processing the LiDAR point cloud as a 2D feature. As a result, point projection can capture more complex geometric information but with longer prediction times. Additionally, we found that Grid-DATrNet using the Transformer global feature extractor outperformed the MLP mixer. The Transformer’s global attention mechanism enables it to capture detailed correlations between BEV grids in both near and far areas, whereas the MLP mixer fails to capture correlations between distant BEV grids [

26]. The visualization of the proposed method’s global attention using the Transformer can be seen in Figure 8. Thus, Grid-DATrNet with the MLP mixer can be used when a faster model is needed for DA detection around autonomous vehicles.

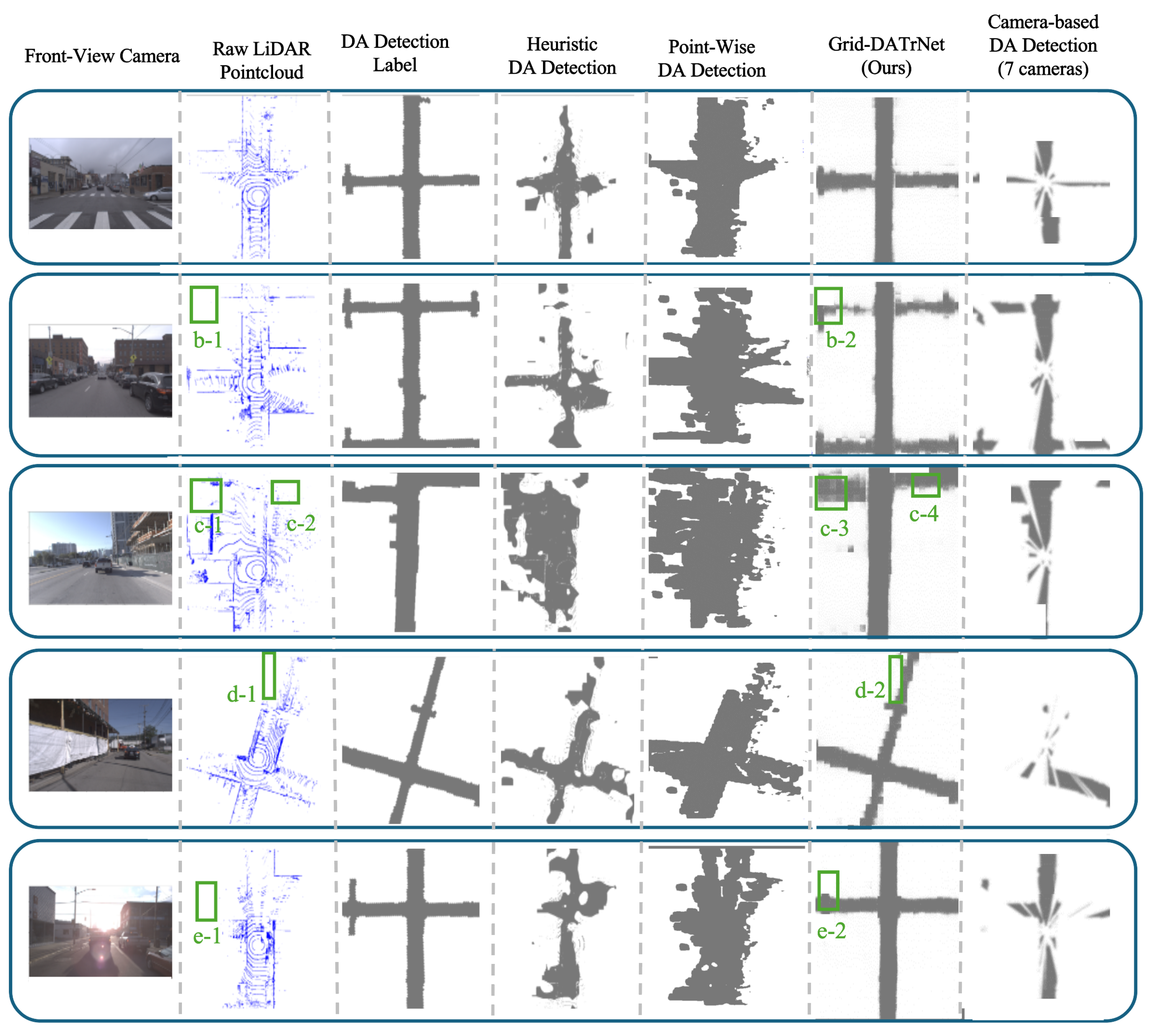

4.5. Comparison with Point-Wise DA Detection using LiDAR

We also compared Grid-DATrNet with point-wise DA detection methods. The results demonstrated that Grid-DATrNet achieves superior performance in grid-wise DA detection tasks. Point-wise DA detection relies on LiDAR point measurements, which limits its ability to detect DA in areas with no point cloud measurements. As shown in

Figure 6, Grid-DATrNet can detect DA even in areas without point cloud measurements. See also

Figure 7 on box b-1, b-2, c-1, c-2, c-3, d-1, d-2, e-1 and e-2. This is because grid-wise DA detection predicts DA areas in all BEV grids around the autonomous vehicle. Predictions of grid-wise DA detection in BEV grids without LiDAR point measurements can enhance motion planning and localization performance for autonomous vehicles.

Furthermore, Grid-DATrNet can detect DA areas even without measurements very well. This is because Grid-DATrNet uses a global attention mechanism through the Transformer, allowing it to find global contextual and semantic information better than CNN-based global feature learning. The experiment also showed that the prediction speed of Grid-DATrNet is not very different from that of point-wise DA detection using GndNet, which employs CNN and achieves better DA detection performance. Therefore, this experiment demonstrates the superior performance of Transformer-based DA detection over CNN-based DA detection. The global attention for DA detection can be seen in

Figure 8.

4.6. Comparison with Camera-Based Methods

We compared the performance of grid-wise DA detection in the Argoverse-grid dataset with state-of-the-art camera-based DA detection methods. The quantitative results highlighted the superior performance of Grid-DATrNet utilizing LiDAR-based approaches (e.g., PointPillar and point projection with Transformer and MLP Mixer) over camera-based methods. Camera-based methods can capture semantic information better than LiDAR-based DA detection, but they lack 3D and depth information. Camera-based DA detection excels in image-based DA segmentation but struggles with grid-wise DA prediction due to the lack of 3D information, particularly in occluded areas. Performance of camera-based will be significantly worse when there is occlusion and few light exposure like in night time as demonstrated by [

26]. We can also see DA detection using camera can only predict DA accurately in short distance around autonomous vehicle

Figure 7 while proposed DA detection using LiDAR network Grid-DATrNet can detect DA even in far area around autonomous vehicle.

4.7. Comparison of Grid-DATrNet in Various ROI

Finally, we analyzed the performance of Grid-DATrNet trained on the Argoverse-grid dataset using various ROI settings, providing insights into the method’s effectiveness under different spatial configurations. The accuracy and F1 scores of the proposed Grid-DATrNet in various ROIs are presented in

Table 2. We observed a slight decrease in the performance of Grid-DATrNet on an ROI size of

, as the LiDAR points in this ROI are sparser compared to those in the

ROI. Consequently, Grid-DATrNet finds it more challenging to detect DA in the

ROI. Additionally, we noticed a significant performance decrease when trained on an ROI size of

, due to the even sparser LiDAR points in this size compared to the

range. We also observed a significant increase in prediction time for ROI sizes of

and

, as the attention mechanism’s computation grows quadratically with the number of BEV image sizes [

41]. The performance of DA detection using the proposed Grid-DATrNet was less effective at very long distances because the LiDAR points become increasingly sparse over larger ranges. However, the performance of Grid-DATrNet on the standard range of the proposed Argoverse-Grid dataset (

) was excellent, significantly outperforming other DA detection methods such as those in [

6] and [

4], which only predict DA within an ROI of

. Therefore, improving networks for DA detection in larger ROIs remains an open research area, as detecting DA in larger regions is crucial for autonomous vehicle motion planning and localization.

5. Conclusions

In this paper, we introduce Argoverse-grid, an open-source, large-scale dataset for grid-wise DA (DA) detection using LiDAR. Argoverse-grid includes over LiDAR frames with detailed grid-wise DA labels across a range of challenging scenarios and time frames. We also present Grid-DATrNet, a grid-wise DA detection model that leverages LiDAR and employs global attention through transformers to detect DA around the ego-vehicle.Our results show that Grid-DATrNet outperforms other DA detection models in terms of accuracy and F1 score, achieving accuracy and an F1 score of . We demonstrate that grid-wise DA detection can identify DA even in occluded areas, significantly enhancing the performance of autonomous vehicle motion planning and localization. Additionally, Grid-DATrNet effectively detects DA over a long range of , compared to previous models that detect areas within .We also discuss how incorporating more complex architectures or novel attention mechanisms could further improve the performance and speed of DA detection, enabling real-time detection over long ranges. We believe this work will advance research in DA detection and contribute to the development of autonomous driving technologies.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korea government (MSIT) (No. 2021R1A2C3008370)

References

- Álvarez, J.M.; López, A.M.; Gevers, T.; Lumbreras, F. Combining Priors, Appearance, and Context for Road Detection. IEEE Transactions on Intelligent Transportation Systems 2014, 15, 1168–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Zhang, H.; Yang, M.; Wang, X.; Ye, L.; Guo, C. Automatic parking based on a bird’s eye view vision system. Advances in Mechanical Engineering 2014, 6, 847406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Yuan, T.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, H. Vectormapnet: End-to-end vectorized hd map learning. International Conference on Machine Learning. PMLR, 2023, pp. 22352–22369.

- Liao, B.; Chen, S.; Wang, X.; Cheng, T.; Zhang, Q.; Liu, W.; Huang, C. MapTR: Structured Modeling and Learning for Online Vectorized HD Map Construction. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2208.14437. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Q.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, H. HDMapNet: An Online HD Map Construction and Evaluation Framework. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2107.06307. [Google Scholar]

- Paigwar, A.; Erkent, O.; Sierra-Gonzalez, D.; Laugier, C. GndNet: Fast Ground Plane Estimation and Point Cloud Segmentation for Autonomous Vehicles. 2020 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS), 2020, pp. 2150–2156. [CrossRef]

- Chang, M.F.; Lambert, J.; Sangkloy, P.; Singh, J.; Bak, S.; Hartnett, A.; Wang, D.; Carr, P.; Lucey, S.; Ramanan, D.; Hays, J. Argoverse: 3D Tracking and Forecasting with Rich Maps. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1911.02620. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, Y.; Jiang, Z.; Wang, Q. Video-based road detection via online structural learning. Neurocomputing 2015, 168, 336–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aly, M. Real time detection of lane markers in urban streets. 2008 IEEE Intelligent Vehicles Symposium. IEEE, 2008. [CrossRef]

- Kong, H.; Audibert, J.Y.; Ponce, J. General Road Detection From a Single Image. IEEE Transactions on Image Processing 2010, 19, 2211–2220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paszke, A.; Chaurasia, A.; Kim, S.; Culurciello, E. ENet: A Deep Neural Network Architecture for Real-Time Semantic Segmentation. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1606.02147. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, P.; Chen, P.; Yuan, Y.; Liu, D.; Huang, Z.; Hou, X.; Cottrell, G. Understanding Convolution for Semantic Segmentation. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1702.08502. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, H.; Shi, J.; Qi, X.; Wang, X.; Jia, J. Pyramid Scene Parsing Network. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1612.01105. [Google Scholar]

- Mehta, S.; Rastegari, M.; Caspi, A.; Shapiro, L.; Hajishirzi, H. ESPNet: Efficient Spatial Pyramid of Dilated Convolutions for Semantic Segmentation. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1803.06815. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, J.; Liu, J.; Tian, H.; Li, Y.; Bao, Y.; Fang, Z.; Lu, H. Dual Attention Network for Scene Segmentation. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1809.02983. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, D.; Liao, M.W.; Zhang, W.T.; Wang, X.G.; Bai, X.; Cheng, W.Q.; Liu, W.Y. YOLOP: You Only Look Once for Panoptic Driving Perception. Machine Intelligence Research 2022, 19, 550–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Che, Q.H.; Nguyen, D.P.; Pham, M.Q.; Lam, D.K. TwinLiteNet: An Efficient and Lightweight Model for Driveable Area and Lane Segmentation in Self-Driving Cars. 2023 International Conference on Multimedia Analysis and Pattern Recognition (MAPR). IEEE, 2023, pp. 1–6.

- Yuan, T.; Liu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, H. StreamMapNet: Streaming Mapping Network for Vectorized Online HD Map Construction. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2308.12570. [Google Scholar]

- Qiao, L.; Ding, W.; Qiu, X.; Zhang, C. End-to-End Vectorized HD-Map Construction With Piecewise Bezier Curve. Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), 2023, pp. 13218–13228.

- Blayney, H.; Tian, H.; Scott, H.; Goldbeck, N.; Stetson, C.; Angeloudis, P. Bezier Everywhere All at Once: Learning Drivable Lanes as Bezier Graphs. Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), 2024, pp. 15365–15374.

- Liu, R.; Yuan, Z. Compact HD Map Construction via Douglas-Peucker Point Transformer. Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence 2024, 38, 3702–3710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, T.; Leng, J.; Zhong, J.; Zhang, Z.; Sun, C. LaneMapNet: Lane Network Recognization and HD Map Construction Using Curve Region Aware Temporal Bird’s-Eye-View Perception. 2024 IEEE Intelligent Vehicles Symposium (IV), 2024, pp. 2168–2175. [CrossRef]

- Jia, P.; Wen, T.; Luo, Z.; Yang, M.; Jiang, K.; Lei, Z.; Tang, X.; Liu, Z.; Cui, L.; Sheng, K.; Zhang, B.; Yang, D. DiffMap: Enhancing Map Segmentation with Map Prior Using Diffusion Model. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2405.02008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, X.; Wei, M.; Yang, Y.; Zhao, H.; Zhang, H.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, Q.; Li, W.; Kong, L.; Zhang, J. Is Your HD Map Constructor Reliable under Sensor Corruptions? arXiv 2024, arXiv:2406.12214. [Google Scholar]

- Zhong, C.; Li, B.; Wu, T. Off-Road Drivable Area Detection: A Learning-Based Approach Exploiting LiDAR Reflection Texture Information. Remote Sensing 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paek, D.H.; Kong, S.H.; Wijaya, K.T. K-lane: Lidar lane dataset and benchmark for urban roads and highways. Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 2022, pp. 4450–4459.

- Ali, A.; Gergis, M.; Abdennadher, S.; El Mougy, A. Drivable Area Segmentation in Deteriorating Road Regions for Autonomous Vehicles using 3D LiDAR Sensor. 2021 IEEE Intelligent Vehicles Symposium (IV), 2021, pp. 845–852. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W. LIDAR-based road and road-edge detection. 2010 IEEE Intelligent Vehicles Symposium, 2010, pp. 845–848. [CrossRef]

- Lang, A.H.; Vora, S.; Caesar, H.; Zhou, L.; Yang, J.; Beijbom, O. Pointpillars: Fast encoders for object detection from point clouds. Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2019, pp. 12697–12705.

- Nagy, I.; Oniga, F. Free Space Detection from Lidar Data Based on Semantic Segmentation. 2021 IEEE 17th International Conference on Intelligent Computer Communication and Processing (ICCP), 2021, pp. 95–100. [CrossRef]

- Raguraman, S.J.; Park, J. Intelligent Drivable Area Detection System using Camera and Lidar Sensor for Autonomous Vehicle. 2020 IEEE International Conference on Electro Information Technology (EIT), 2020, pp. 429–436. [CrossRef]

- Lele Wang, Y.P. "LiDAR–camera fusion for road detection using a recurrent conditional random field model". "Nature : Scientific Reports", 2022.

- Shaban, A.; Meng, X.; Lee, J.; Boots, B.; Fox, D. Semantic Terrain Classification for Off-Road Autonomous Driving. Proceedings of the 5th Conference on Robot Learning; Faust, A.; Hsu, D.; Neumann, G., Eds. PMLR, 2022, Vol. 164, Proceedings of Machine Learning Research, pp. 619–629.

- Caltagirone, L.; Scheidegger, S.; Svensson, L.; Wahde, M. Fast LIDAR-based Road Detection Using Fully Convolutional Neural Networks. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1703.03613. [Google Scholar]

- Ronneberger, O.; Fischer, P.; Brox, T. U-net: Convolutional networks for biomedical image segmentation. International Conference on Medical image computing and computer-assisted intervention. Springer, 2015, pp. 234–241.

- Badrinarayanan, V.; Kendall, A.; Cipolla, R. SegNet: A Deep Convolutional Encoder-Decoder Architecture for Image Segmentation. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1511.00561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, B. Sparse 3D convolutional neural networks. arXiv 2015, arXiv:1505.02890. [Google Scholar]

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N. ; Kaiser,.; Polosukhin, I. Attention is all you need. Advances in neural information processing systems, 2017, pp. 5998–6008.

- Ku, J.; Mozifian, M.; Lee, J.; Harakeh, A.; Waslander, S.L. Joint 3d proposal generation and object detection from view aggregation. 2018 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS). IEEE, 2018, pp. 1–8.

- Simony, M.; Milzy, S.; Amendey, K.; Gross, H.M. Complex-yolo: An euler-region-proposal for real-time 3d object detection on point clouds. Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV) Workshops, 2018, pp. 0–0.

- Dosovitskiy, A.; Beyer, L.; Kolesnikov, A.; Weissenborn, D.; Zhai, X.; Unterthiner, T.; Dehghani, M.; Minderer, M.; Heigold, G.; Gelly, S.; Uszkoreit, J.; Houlsby, N. An Image is Worth 16x16 Words: Transformers for Image Recognition at Scale. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2010.11929. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, T.Y.; Goyal, P.; Girshick, R.; He, K.; Dollár, P. Focal Loss for Dense Object Detection. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1708.02002. [Google Scholar]

Figure 1.

Examples of grid-wise and point-wise DA detection. Grid-wise DA detection can detect DA even in occluded region (black dashed box) while point-wise DA detection can not.

Figure 1.

Examples of grid-wise and point-wise DA detection. Grid-wise DA detection can detect DA even in occluded region (black dashed box) while point-wise DA detection can not.

Figure 2.

End-to-end process of making DA dataset using Argoverse 1 dataset.

Figure 2.

End-to-end process of making DA dataset using Argoverse 1 dataset.

Figure 3.

Example of DA (DA) Labeling using the Argoverse 1 Dataset. Left: The DA is projected onto the image, where green indicates distant areas, and red indicates areas closer to the ego-vehicle. The projection returns to red beyond the LiDAR visualization range of 50m. The top visualization shows the ego-vehicle at a complex four-way intersection. The second visualization depicts the ego-vehicle in a heavily congested area surrounded by cars. The bottom visualization represents the ego-vehicle in a narrow urban area. Right: The labeled DA in the Argoverse dataset, where gray represents the DA, and white represents non-DAs. The blue rectangle indicates the ego-vehicle, with its yaw orientation facing upward.

Figure 3.

Example of DA (DA) Labeling using the Argoverse 1 Dataset. Left: The DA is projected onto the image, where green indicates distant areas, and red indicates areas closer to the ego-vehicle. The projection returns to red beyond the LiDAR visualization range of 50m. The top visualization shows the ego-vehicle at a complex four-way intersection. The second visualization depicts the ego-vehicle in a heavily congested area surrounded by cars. The bottom visualization represents the ego-vehicle in a narrow urban area. Right: The labeled DA in the Argoverse dataset, where gray represents the DA, and white represents non-DAs. The blue rectangle indicates the ego-vehicle, with its yaw orientation facing upward.

Figure 4.

End-to-end architecture of Grid-DATrNet: (1) LiDAR BEV features are encoded using a LiDAR encoder, such as PointPillar. (2) BEV features are divided into location-wise patches. (3) A global attention mechanism is applied using layers of a Transformer. (4) The BEV feature patches, now with global attention, are reassembled into the BEV feature map. (5) Finally, dense DA is predicted using layers of CNN, batch normalization, and activation functions.

Figure 4.

End-to-end architecture of Grid-DATrNet: (1) LiDAR BEV features are encoded using a LiDAR encoder, such as PointPillar. (2) BEV features are divided into location-wise patches. (3) A global attention mechanism is applied using layers of a Transformer. (4) The BEV feature patches, now with global attention, are reassembled into the BEV feature map. (5) Finally, dense DA is predicted using layers of CNN, batch normalization, and activation functions.

Figure 5.

Comparison of CNN-based and attention-based global correlation in DA detection. In the example, CNN-based global correlation (top right diagram) uses a feature map with very low spatial resolution to find correlations between distant grids. In contrast, attention-based global correlation (bottom right diagram) uses a feature map with the same spatial resolution as the original feature map.

Figure 5.

Comparison of CNN-based and attention-based global correlation in DA detection. In the example, CNN-based global correlation (top right diagram) uses a feature map with very low spatial resolution to find correlations between distant grids. In contrast, attention-based global correlation (bottom right diagram) uses a feature map with the same spatial resolution as the original feature map.

Figure 6.

Visualization result of Point-wise DA detection result compare to Grid-wise DA detection. Point-wise DA detection could not detect DA in occluded area in black dashed box while grid-wise DA detection could.

Figure 6.

Visualization result of Point-wise DA detection result compare to Grid-wise DA detection. Point-wise DA detection could not detect DA in occluded area in black dashed box while grid-wise DA detection could.

Figure 7.

Visualization result of Point-Wise DA detection compared to Grid-Wise DA detection trained on Argoverse-grid dataset. Blue is lidar points, gray grid is DA grid and white grid is non- DA grid. Proposed method Grid-DATrNet can detect DA area around ego-vehicle even in occluded and unmeasured area in green box b-1, b-2, c-1, c-2, c-3, c-4, d-1, d-2, e-1, and e-2.

Figure 7.

Visualization result of Point-Wise DA detection compared to Grid-Wise DA detection trained on Argoverse-grid dataset. Blue is lidar points, gray grid is DA grid and white grid is non- DA grid. Proposed method Grid-DATrNet can detect DA area around ego-vehicle even in occluded and unmeasured area in green box b-1, b-2, c-1, c-2, c-3, c-4, d-1, d-2, e-1, and e-2.

Figure 8.

Visualization of global attention using the Transformer in the proposed Grid-DATrNet method. Blue points represent LiDAR points, gray grids represent DA, and white grids represent non-DA. The intensity of the global attention correlation is indicated by the color of the grid, with higher correlation shown in red and lower correlation in nearly black. The global attention mechanism in the proposed Grid-DATrNet can detect correlations between DA grids even in occluded and undetected areas in green box of the image.

Figure 8.

Visualization of global attention using the Transformer in the proposed Grid-DATrNet method. Blue points represent LiDAR points, gray grids represent DA, and white grids represent non-DA. The intensity of the global attention correlation is indicated by the color of the grid, with higher correlation shown in red and lower correlation in nearly black. The global attention mechanism in the proposed Grid-DATrNet can detect correlations between DA grids even in occluded and undetected areas in green box of the image.

Table 1.

Experimental results of DA Detection on Argoverse-grid dataset. C means detector using modalities cameras while L means detector using sensor LiDAR.

Table 1.

Experimental results of DA Detection on Argoverse-grid dataset. C means detector using modalities cameras while L means detector using sensor LiDAR.

| Detector |

Sensor |

Accuracy(%) ↑ |

F1-Score ↑ |

Speed (ms) ↓ |

| TwinLiteNet (7 cameras) [17] |

C |

72.88 |

0.5273 |

125 |

| MapTr (7 cameras) [4] |

C |

74.88 |

0.5324 |

182 |

| Gaussian Bayes Kernel [31] |

L |

82.33 |

0.6255 |

2400 |

| GndNet [6] |

L |

88.65 |

0.7225 |

200 |

| Grid-DATrNet (Ours) |

L |

|

|

| - Transformer + PointPillar |

|

93.28 |

0.8328 |

231 |

| - Transformer + Point Projection |

|

93.40 |

0.8321 |

280 |

| - MLP Mixer + PointPillar |

|

91.40 |

0.8145 |

205 |

| - MLP Mixer + Point Projection |

|

91.63 |

0.8233 |

213 |

Table 2.

Experimental results of Grid-DATrNet in Argoverse-grid dataset using various ROI size

Table 2.

Experimental results of Grid-DATrNet in Argoverse-grid dataset using various ROI size

| ROI Size |

Accuracy(%) |

F1 Score |

Inference Time (ms) |

|

93.28 |

0.8328 |

231 |

|

88.35 |

0.7732 |

324 |

|

75.42 |

0.6588 |

502 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).