Submitted:

20 September 2024

Posted:

23 September 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Sample Size Calculation

2.2. Participants and Setting

2.3. Measurements

2.3.1. Medical Record for Sociodemographic Data Such as Age, Sex, and Axis I (Clinical Disorder)

2.3.2. The SCID-II Personality Disorder (Borderline PD)

2.3.3. Inner-Strength-Based Inventory (I-SBI)

2.3.4. Outcome Inventory-21

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

Implication of the Study and Future Research

Strengths and Limitation

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mosquera, D., A. Gonzalez, and A.M. Leeds, Early experience, structural dissociation, and emotional dysregulation in borderline personality disorder: the role of insecure and disorganized attachment.

- van Dijke, A. and J.D. Ford, Adult attachment and emotion dysregulation in borderline personality and somatoform disorders.

- Lohanan, T., et al., Development and validation of a screening instrument for borderline personality disorder (SI-Bord) for use among university students. BMC Psychiatry, 2020. 20(1): p. 479. [CrossRef]

- Brüne, M., Borderline Personality Disorder: Why 'fast and furious'? Evol Med Public Health, 2016. 2016(1): p. 52-66. [CrossRef]

- Urnes, O., [Self-harm and personality disorders]. Tidsskr Nor Laegeforen, 2009. 129(9): p. 872-6. [CrossRef]

- Nitkowski, D. and F. Petermann, [Non-suicidal self-injury and comorbid mental disorders: a review]. Fortschr Neurol Psychiatr, 2011. 79(1): p. 9-20. [CrossRef]

- Oumaya, M., et al., [Borderline personality disorder, self-mutilation and suicide: literature review]. Encephale, 2008. 34(5): p. 452-8. [CrossRef]

- Reichl, C. and M. Kaess, Self-harm in the context of borderline personality disorder. Curr Opin Psychol, 2021. 37: p. 139-144. [CrossRef]

- Martin, J.A. and K.N. Levy, Chronic feelings of emptiness in a large undergraduate sample: Starting to fill the void. Personal Ment Health, 2022. 16(3): p. 190-203. [CrossRef]

- Fulham, L., J. Forsythe, and S. Fitzpatrick, The relationship between emptiness and suicide and self-injury urges in borderline personality disorder. Suicide Life Threat Behav, 2023. 53(3): p. 362-371. [CrossRef]

- Herron, S.J. and F. Sani, Understanding the typical presentation of emptiness: a study of lived-experience. J Ment Health, 2022. 31(2): p. 188-195. [CrossRef]

- Miller, C.E., M.L. Townsend, and B.F.S. Grenyer, Understanding chronic feelings of emptiness in borderline personality disorder: a qualitative study. Borderline Personal Disord Emot Dysregul, 2021. 8(1): p. 24. [CrossRef]

- Klonsky, E.D., What is emptiness? Clarifying the 7th criterion for borderline personality disorder. J Pers Disord, 2008. 22(4): p. 418-26. [CrossRef]

- Elsner, D., J.H. Broadbear, and S. Rao, What is the clinical significance of chronic emptiness in borderline personality disorder? Australas Psychiatry, 2018. 26(1): p. 88-91. [CrossRef]

- Miller, C.E., et al., Measuring the shadows: A systematic review of chronic emptiness in borderline personality disorder. PLoS One, 2020. 15(7): p. e0233970. [CrossRef]

- D'Agostino, A., et al., The Feeling of Emptiness: A Review of a Complex Subjective Experience. Harv Rev Psychiatry, 2020. 28(5): p. 287-295. [CrossRef]

- Brickman, L.J., et al., The relationship between non-suicidal self-injury and borderline personality disorder symptoms in a college sample. Borderline Personality Disorder and Emotion Dysregulation, 2014. 1(1): p. 14. [CrossRef]

- Salgó, E., et al., Emotion regulation, mindfulness, and self-compassion among patients with borderline personality disorder, compared to healthy control subjects. PLoS One, 2021. 16(3): p. e0248409. [CrossRef]

- Kresznerits, S., Á. Zinner-Gérecz, and D. Perczel-Forintos, [Borderline personality disorder and non-suicidal self-injury: the role of mindfulness training in risk reduction]. Psychiatr Hung, 2023. 38(2): p. 142-152.

- Heath, N.L., et al., The Relationship Between Mindfulness, Depressive Symptoms, and Non-Suicidal Self-Injury Amongst Adolescents. Arch Suicide Res, 2016. 20(4): p. 635-49. [CrossRef]

- Wupperman, P., et al., Borderline personality features and harmful dysregulated behavior: the mediational effect of mindfulness. J Clin Psychol, 2013. 69(9): p. 903-11. [CrossRef]

- Shorey, R.C., et al., The relationship between dispositional mindfulness, borderline personality features, and suicidal ideation in a sample of women in residential substance use treatment. Psychiatry Res, 2016. 238: p. 122-128. [CrossRef]

- Feliu-Soler, A., et al., Fostering Self-Compassion and Loving-Kindness in Patients With Borderline Personality Disorder: A Randomized Pilot Study. Clin Psychol Psychother, 2017. 24(1): p. 278-286. [CrossRef]

- Keng, S.L. and J.X. Tan, Effects of brief mindful breathing and loving-kindness meditation on shame and social problem solving abilities among individuals with high borderline personality traits. Behav Res Ther, 2017. 97: p. 43-51. [CrossRef]

- Tortella-Feliu, M., et al., Relationship between effortful control and facets of mindfulness in meditators, non-meditators and individuals with borderline personality disorder. Personal Ment Health, 2018. 12(3): p. 265-278. [CrossRef]

- Didonna, F.a.G.Y., Mindfulness and Feelings of Emptiness. 2009. 125-151.

- Natividad, A., et al., What aspects of mindfulness and emotion regulation underpin self-harm in individuals with borderline personality disorder? J Ment Health, 2024. 33(2): p. 141-149. [CrossRef]

- Pongpitpitak, N., et al., Buffering Effect of Perseverance and Meditation on Depression among Medical Students Experiencing Negative Family Climate. Healthcare (Basel), 2022. 10(10). [CrossRef]

- Wongpakaran, N., T. Wongpakaran, and P. Kuntawong, Development and Validation of the inner Strength-Based Inventory (SBI). Mental Health, Religion & Culture, 2020. 23(3-4): p. 263-273. [CrossRef]

- Winzer, L., B. Samutachak, and R. Gray, Religiosity, Spirituality, and Happiness in Thailand from the Perspective of Buddhism. Journal of Population and Social Studies, 2018. 26: p. 332-343. [CrossRef]

- DeMaranville, J., et al., Meditation and Five Precepts Mediate the Relationship between Attachment and Resilience. Children (Basel), 2022. 9(3). [CrossRef]

- Kövi, Z., et al., Relationship between Personality Traits and the Inner Strengths. Psychiatr Danub, 2021. 33(Suppl 4): p. 844-849.

- Thavaro, V., Handbook of meditation practice. 1982, Chuanpim Bangkok, Thailand:.

- Desbordes, G., et al., Moving beyond Mindfulness: Defining Equanimity as an Outcome Measure in Meditation and Contemplative Research. Mindfulness (N Y), 2014. 2014(January): p. 356-72. [CrossRef]

- Maurer, B.T., Evaluating the patient with a measure of equanimity. JAAPA, 2009. 22(12): p. 56.

- Giluk, T.L., Mindfulness, Big Five personality, and affect: A meta-analysis. Personality and Individual Differences, 2009. 47(8): p. 805-811. [CrossRef]

- Ostafin, B.D., M.D. Robinson, and B.P. Meier, Introduction: The science of mindfulness and self-regulation. Handbook of mindfulness and self-regulation, 2015: p. 1-6. [CrossRef]

- Kwok, J.Y.Y., et al., Effects of Mindfulness Yoga vs Stretching and Resistance Training Exercises on Anxiety and Depression for People With Parkinson Disease: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Neurol, 2019. 76(7): p. 755-763. [CrossRef]

- Wongpakaran, N., et al., Role of Equanimity on the Mediation Model of Neuroticism, Perceived Stress and Depressive Symptoms. Healthcare (Basel), 2021. 9(10). [CrossRef]

- Mann, L.M. and B.R. Walker, The role of equanimity in mediating the relationship between psychological distress and social isolation during COVID-19. J Affect Disord, 2022. 296: p. 370-379. [CrossRef]

- Schoemann, A., A. Boulton, and S. Short, Determining Power and Sample Size for Simple and Complex Mediation Models. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 2017. 8: p. 194855061771506. [CrossRef]

- Wongpakaran, T., et al., Interrater reliability of Thai version of the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis II Personality Disorders (T-SCID II). J Med Assoc Thai, 2012. 95(2): p. 264-9.

- Wongpakaran, N., et al., Moderating role of observing the five precepts of Buddhism on neuroticism, perceived stress, and depressive symptoms. PLOS ONE, 2022. 17(11): p. e0277351. [CrossRef]

- Wongpakaran, N., T. Wongpakaran, and Z. Kövi, Development and validation of 21-item outcome inventory (OI-21). Heliyon, 2022. 8(6): p. e09682. [CrossRef]

| Variables | All (n=302) |

NSSI1 | Non-NSSI1 | Test Difference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (year) | 36.56 ±17.17 | 34.92 ±17.10 | 41.35 ±16.60 | t (296) = -2.85, p = 0.005 |

| Sex, female | 195 (65.4%) | 146 (65.8%) | 49 (64.5%) | χ2 (1) = 0.042, p = 0.838 |

| Education Lower Bachelor or higher |

135 (45.3%) 163 (54.7%) |

99 (44.6%) 123 (55.4%) |

36 (47.4%) 40 (52.6%) |

χ2 (1) = 0.176, p = 0.675 |

| Marital status Together Alone |

120 (40.3%) 178 (59.7%) |

91 (41%) 131 (59%) |

29 (38.2%) 47 (61.8%) |

χ2 (1) = 0.189, p = 0.664 |

| Emptiness | 242 (80.1%) | 212 (93.8%) | 30 (23.3%) | χ2 (1) = 105.45, p <0.001 |

| OI-Depress2 | 13.46 ±5.37 | 14.24 ±5.41 | 11.14 ±4.54 | t (300) = 4.48, p <0.001 |

| Variables | N(%) or mean SD | Emptiness | NSSI1 | OI-Dep2 | Precepts | Meditation | Equanimity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Emptiness | 242 (80.1%) | . | |||||

| NSSI1 | 226 (74.8%) | 0.591** | . | ||||

| OI-Dep2 | 13.46 ±5.4 | 0.309** | 0.251** | . | |||

| Precepts | 2.83 ±1.2 | -0.236** | -0.240** | -0.081 | . | ||

| Meditation | 1.72 ±1.0 | -0.250** | -0.240** | -0.162** | 0.420** | . | |

| Equanimity | 2.90 ±1.2 | -0.188** | -0.232** | -0.380** | 0.096 | 0.158** | . |

| Antecedent | Coeff. 1 | 95%CI | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| X (emptiness) | 0.565 | 0.507, 0.721 | <0.001 |

| Age | 0.002 | -0.002, 0.003 | 0.64 |

| OI-Dep2 | 0.080 | -0.002, 0.015 | 0.118 |

| R2= 0.35 | |||

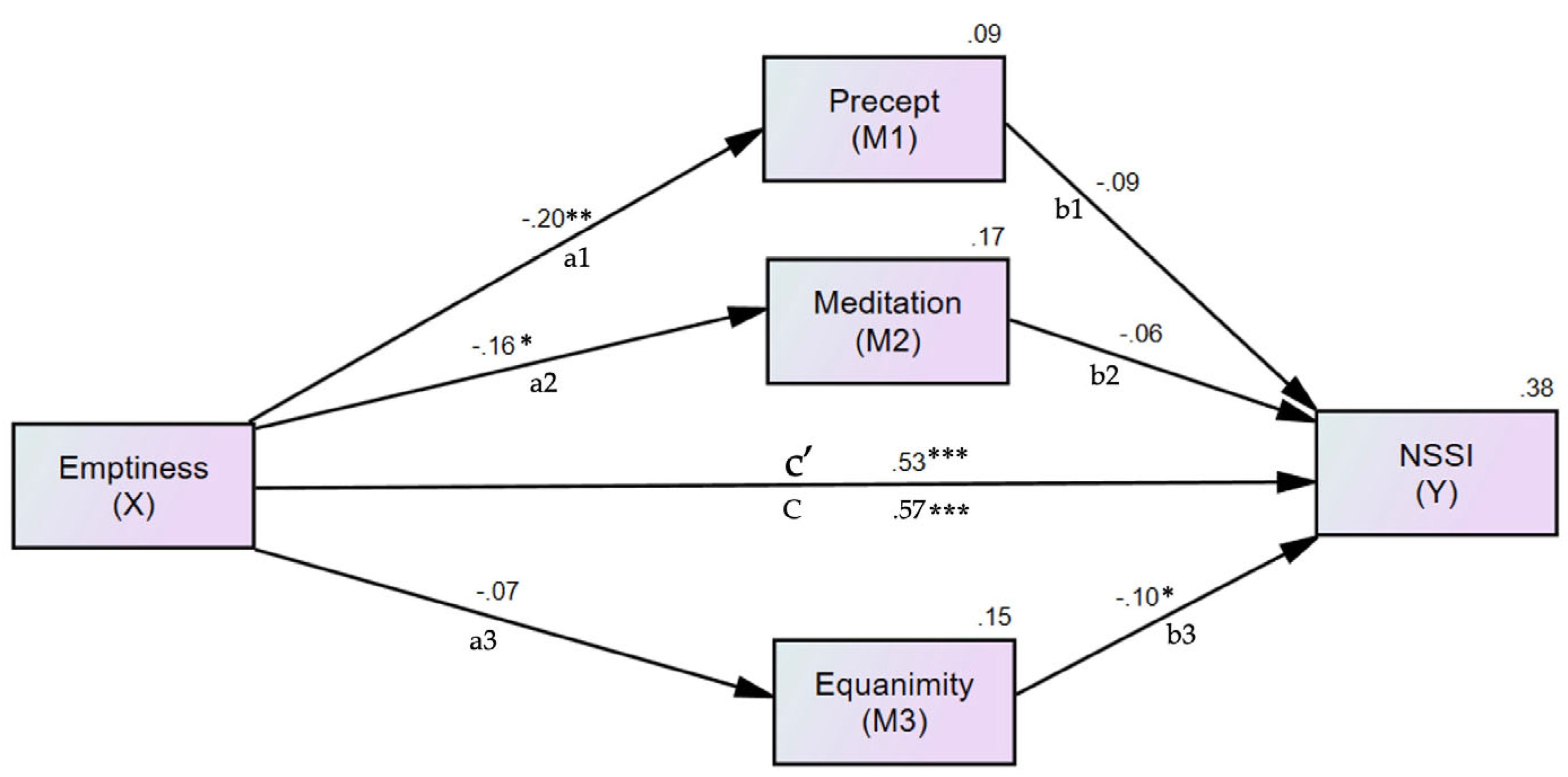

| Coeff. 1 ( 95%CI), p-value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antecedent | M1 (Precept) | M2 (Meditation) | M3 (Equanimity) | Y (NSSI2) |

| X (emptiness) | -0.200 (-0.319, -0.073), 0.001 | -0.164 (-0.303, 0.028), 0.018 | -0.071(-0.182, 0.039), 0.210 | 0.534, (0.417, 0.647), <0.001 |

| Precept | -0.085 (-0.179, 0.009), 0.077 | |||

| Meditation | -0.060 (-0.179, 0.055), 0.304 | |||

| Equanimity | -0.103 (-0.194, 0-.017), 0.016 | |||

| R2= 0.09 | R2= 0.17 | R2= 0.15 | R2= 0.38 | |

| Antecedent | Effect | 95%CI | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Emptiness | 0.034 | 0.009, 0.075 | 0.005 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).