Submitted:

22 September 2024

Posted:

23 September 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

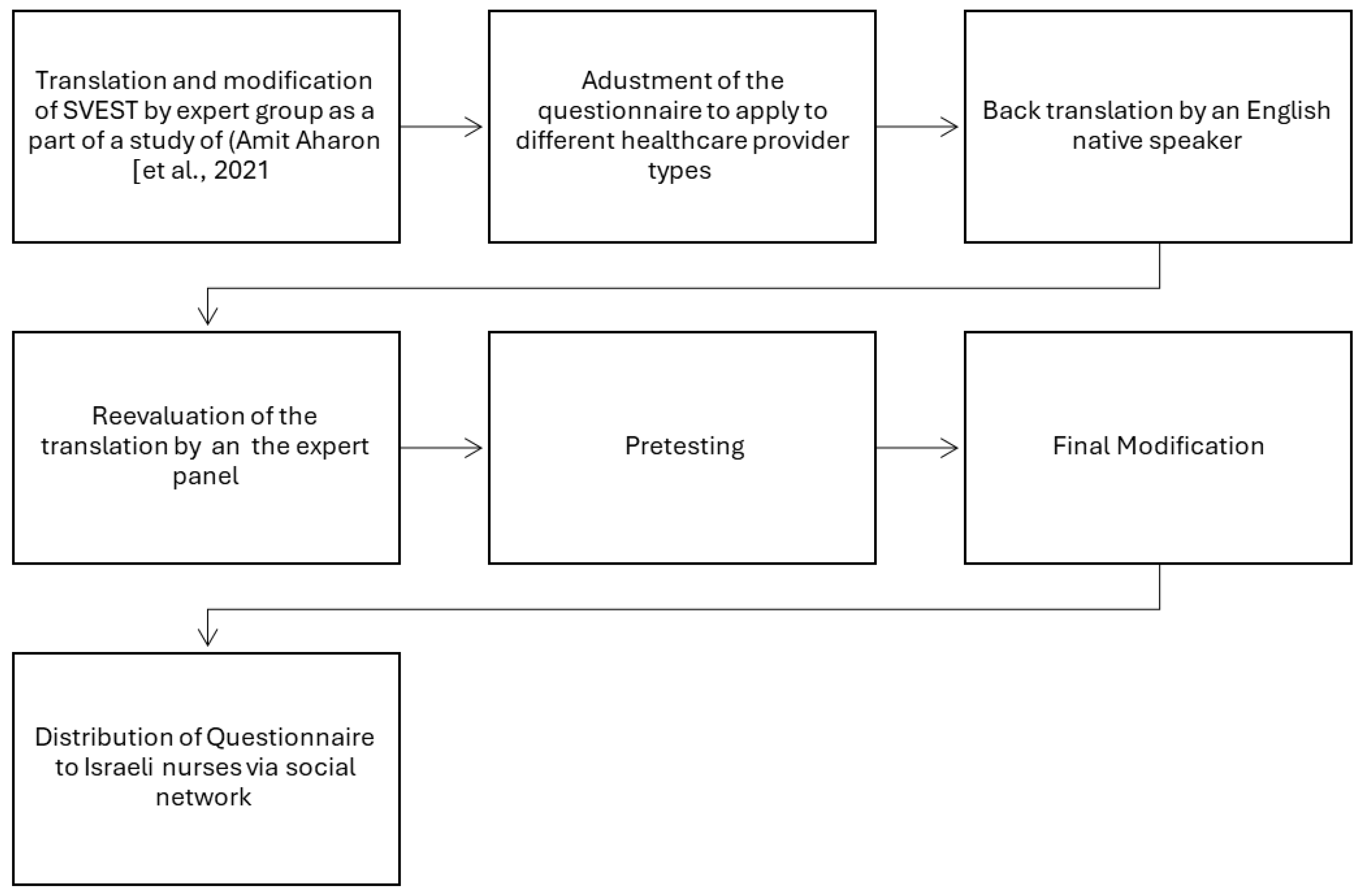

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA)

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Public Involvement Statement

Guidelines and Standards Statement

Use of Artificial Intelligence

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- de Vries, E.N., Ramrattan. The incidence and nature of in-hospital adverse events: A systematic review. Qual Saf Health Care 2008, 17, 216–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winning, A.M.; Merandi, J.; Rausch, J.R.; Liao, N.; Hoffman, J.M.; Burlison, J.D.; Gerhardt, C.A. Validation of the Second Victim Experience and Support Tool—Revised in the neonatal intensive care unit. J Patient Saf 2021, 17, 531–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, I.; Schuster, A.; Smith, K.; Pronovost, P.; Wu, A. Patient safety incident reporting: a qualitative study of thoughts and perceptions of experts 15 years after ‘To Err is Human’. BMJ Qual Saf 2016, 25, 92–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lane, M.A.; Newman, B.M.; Taylor, M.Z.; O'Neill, M.; Ghetti, C.; Woltman, R.M.; Waterman, A.D. Supporting clinicians after adverse events: development of a clinician peer support program. Patient Saf 2018, 14, e56–e60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valencia-Martín, J.L. , Vicente-Guijarro, D., San Jose-Saras, P., Moreno-Nunez, P., Pardo-Hernández, A., Aranaz-Andrés, J.A., ESHMAD Director Group and external advisers. Prevalence, characteristics, and impact of Adverse Events in 34 Madrid hospitals. The ESHMAD Study. Eur J Clin Invest 2022, 52, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Gerven, E.; Vander Elst, T.; Vandenbroeck, S.; Dierickx, S.; Euwema, M.; Sermeus, W.; De Witte, H.; Godderis, L. Vanhaecht, K. Increased risk of burnout for physicians and nurses involved in a patient safety incident. Med Care 2016, 54, 937–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, A. Medical error: The second victim. BMJ 2000, 320, 726–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seys, D.; Wu, A.W.; Van Gerven, E.; Vleugels, A.; Euwema, M.; Panella, M.; Scott, S.D.; Conway, J.; Sermeus, W.; Vanhaecht, K. Health care professionals as second victims after adverse events: A systematic review. Eval Health Prof 2013, 36, 135–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganahl, S.; Knaus, M.; Wiesenhuetter, I.; Klemm, V.; Jabinger, E.M.; Strametz, R. Second victims in intensive care-emotional stress and traumatization of intensive care nurses in Western Austria after adverse events during the treatment of patients. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2022, 19, 3611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanhaecht, K.; Seys, D.; Russott, S.; Strametz, R.; Mira, J.; Sigurgeirsdóttir, S.; Wu, A.W.; Polluste, K.; Popovici, D.G.; Sfetcu, R.; Kurt, S. An evidence and consensus-based definition of second victim: a strategic topic in healthcare quality, patient safety, person-centeredness and human resource management. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2022, 19, 16869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strametz, R.; Fendel, J.C.; Koch, P.; Roesner, H.; Zilezinski, M.; Bushuven, S.; Raspe, M. Prevalence of second victims, risk factors, and support strategies among German nurses (SeViD-II Survey). Int J Environ Res Public Health 2021, 18, 10594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finney, R.E. Implementation of a second victim peer support program in a large anesthesia department. AANA J 2021, 89, 235–244. [Google Scholar]

- Haung, R.; Sun, H.; Chen, G.; Li, Y.; Wang, J. Second-victim experience and support among nurses in mainland China. J Nurs Manag 2021, 30, 260–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, S.D.; Hirschinger, L.E.; Cox, K.R.; McCoig, M.; Brandt, J.; Hall, L.W. The natural history of recovery for the healthcare provider “second victim” after adverse patient events. Qual Saf Health Care 2009, 18, 325–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, C.L.; Abreu, L.C.; Ramos, J.L.S.; Castro, C.F.; Smiderle, F.R.; Santos, J.A.; Bezerra, I.M. Influence of burnout on patient safety: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicina 2019, 55, 553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busch, I.M.; Moretti, F.; Purgato, M.; Barbui, C.; Wu, A.W.; Rimondini, M. Psychological and psychosomatic symptoms of second victims of adverse events: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Patient Saf 2020, 16, 61–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sachs, C.J.; Wheaton, N. Second Victim Syndrome. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing, 2023.

- Leinweber, J.; Creedy, D.K.; Rowe, H.; Gamble, J. Responses to birth trauma and prevalence of posttraumatic stress among Australian midwives. Women Birth 2017, 30, 40–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baas, M.A.; Scheepstra, K.W.; Stramrood, C.A.; Evers, R.; Dijksman, L.M.; van Pampus, M.G. Work-related adverse events leaving their mark: A cross-sectional study among Dutch gynecologists. BMC Psychiatry 2018, 18, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutheil, F.; Aubert, C.; Pereira, B.; Dambrun, M.; Moustafa, F.; Mermillod, M.; Baker, J.S.; Trousselard, M.; Lesage, F.X.; Navel, V. Suicide among physicians and health-care workers: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0226361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seys, D.; Panella, M.; Russotto, S.; Strametz, R.; Joaquín Mira, J.; Van Wilder, A.; Godderis, L.; Vanhaecht, K. In search of an international multidimensional action plan for second victim support: A narrative review. BMC Health Serv Res 2023, 23, 816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hauk, L. Support strategies for health care professionals who are second victims. AORN J 2018, 107, P7–P9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rinaldi, C.; Leigheb, F.; Vanhaecht, K.; Donnarumma, C.; Panella, M. Becoming a “second victim” in health care: Pathway of recovery after adverse event. Rev Calid Asist 2016, 31, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panella, M.; Rinaldi, C.; Leigheb, F.; Donnarumma, C.; Kul, S.; Vanhaecht, K.; Di Stanislao, F. The determinants of defensive medicine in Italian hospitals: The impact of being a second victim. Rev Calid Asist 2016, 31, 20–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozeke, O.; Ozeke, V.; Coskun, O.; Budakoglu, I.I. Second victims in health care: Current perspectives. Adv Med Educ Pract 2019, 10, 593–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amit Aharon, A.; Fariba, M.; Shoshana, F.; Melnikov, S. Nurses as “second victims” to their patients’ suicidal attempts: A mixed-method study. J Clin Nurs 2021, 30, 3290–3300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busch, I.M.; Moretti, F.; Campagna, I.; Benoni, R.; Tardivo, S.; Wu, A.W.; Rimondini, M. Promoting the psychological well-being of healthcare providers facing the burden of adverse events: A systematic review of second victim support resources. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2021, 18, 5080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, A.A.; Brock, D.M.; McCotter, P.I.; Hofeldt, R.; Edrees, H.H.; Wu, A.W.; Shannon, S.; Gallagher, T.H. Risk managers' descriptions of programs to support second victims after adverse events. J Healthc Risk Manag 2015, 4, 30–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, R.; Sela, Y.; Nissanholtz-Gannot, R. Addressing the second victim phenomenon in Israeli health care institutions. Isr J Health Policy Res 2023, 12, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, R.; Sela, Y.; Halevi Hochwald, I.; Nissanholz-Gannot, R. Nurses' silence: Understanding the impacts of second victim phenomenon among Israeli nurses. Healthcare 2023, 11, 1961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rassin, M.; Kanti, T. The “Second Victim”: Nurses’ coping with medication errors comparison of two decades (2005-2018). J Nur Healthcare 2019, 4, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shor, *!!! REPLACE !!!*; S, *!!! REPLACE !!!*; Tal, O.; Maymon, R. The second victim: Treating the health care providers. Harefuah, 2017; 156, 38–40. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, R.; Sela-Vilensky, Y.; Greenberg, K.; Nissanholz-Gannot, R. Nurses’ silence: The second victim phenomenon in Israel. Guf Yeda 2024, 24, 7. [Google Scholar]

- Burlison, J.D.; Scott, S.D.; Browne, E.K.; Thompson, S.G.; Hoffman, J.M. The second victim experience and support tool: validation of an organizational resource for assessing second victim effects and the quality of support resources. J Patient Saf 2017, 13, 93–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, E.M.; Kim, S.A.; Lee, J.R.; Burlison, J.D.; Oh, E.G. Psychometric properties of Korean version of the Second Victim Experience and Support Tool (K-SVEST). J. Patient Saf 2020, 16, 179–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Yang, Q.; Zhao, Q.; Zheng, S.; Xiao, M. Psychometric validation of the Chinese version of the Second Victim Experience and Support Tool (C-SVEST). J Nurs Manag 2019, 27, 1416–1422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scarpis, E.; Castriotta, L.; Ruscio, E.; Bianchet, B.; Doimo, A.; Moretti, V.; Cocconi, R.; Farneti, F.; Quattrin, R. The Second Victim Experience and Support Tool: A cross-cultural adaptation and psychometric evaluation in Italy (IT-SVEST). J Patient Saf 2022, 18, 88–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koca, A., Elhan. Validation of the Turkish version of the Second Victim Experience and Support Tool (T-SVEST). Heliyon 2022, 8, e10553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santana-Domínguez, I.; González-de la Torre, H.; Verdú-Soriano, J.; Nolasco, A.; Martín-Martínez, A. Validation and psychometric properties of the Spanish version of the Second Victim Experience and Support Tool Questionnaire. J Patient Saf 2022, 18, 692–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunelli, M.V.; Estrada, S.; Celano, C. Cross-cultural adaptation and psychometric evaluation of a Second Victim Experience and Support Tool (SVEST). J Patient Saf 2021, 17, e1401–e1405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strametz, R.; Siebold, B.; Heistermann, P.; Haller, S.; Bushuven, S. Validation of the German version of the Second Victim Experience and Support Tool-Revised. J Patient Saf 2022, 18, 182–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knudsen, T.; Abrahamsen, C.; Jørgensen, J.S.; Schrøder, K. Validation of the Danish version of the Second Victim Experience and Support Tool. Scand J Public Health 2022, 50, 497–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keshet, Y.; Popper-Giveon, A. Language practice and policy in Israeli hospitals: the case of the Hebrew and Arabic languages. Isr J Health Policy Res 2019, 8, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalagy, T.; Abu-Kaf, S.; Braun-Lewensohn, O. Effective ways to encourage health-care practices among cultural minorities in Israel during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2021, 18, 9563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Process of Translation and Adaptation of Instruments. WHO Website 2020. Available online: http://www.who.int/substance_abuse/research_tools/translation/en/ (accessed on 14 April 2022).

- Soper, D. A-priori Sample Size Calculator for Structural Equation Models [stats calculator website]. 14 April. Available online: https://www.danielsoper.com/statcalc/calculator.aspx?id=89 (accessed on 14 April 2022).

- Westland, J.C. Lower bounds on sample size in structural equation modeling. Electron Commer Res Appl 2010, 9, 476–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranatunga, R.V.S.P.K.; Priyanath, H.M.S.; Megama, R.G.N. Methods and rule-of-thumbs in the determination of minimum sample size when applying Structural Equation Modelling: A review. JSSR 2020, 15, 102–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthén, B.O.; Muthén, L.K. How to use a Monte Carlo study to decide on sample size and determine power. Struct Equ Modeling 2002, 9, 599–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Vet, H.C.W. , Mokking, L.B., Knol, D.L. Measurement in medicine: A practical guide. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011.

- Rosseel, Y. Iavaan: An R package for structural equation modeling. J Stat Softw 2012, 48, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bland, M.; Altman, D.G. Cronbach's alpha. BMJ 1997, 314, 572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavakol, M.; Dennick, R. Making sense of Cronbach's alpha. Int J Med Educ 2011, 2, 53–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Y. , Yang, Y. RMSEA, CFI, and TLI in structural equation modeling with ordered categorical data: The story they tell depends on the estimation methods. Behav Re Methods 2019, 51, 409–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Survey Items | Dimensions & Outcome Variables |

|---|---|

| I have experienced embarrassment from these instances. | Psychological Distress |

| My involvement in these types of instances has made me fearful of future occurrences. | |

| My experiences have made me feel miserable. | |

| I feel deep remorse for my past involvements in these types of events. | |

| The mental weight of my experience is exhausting. | Physical Distress |

| My experience with these occurrences can make it hard to sleep regularly. | |

| The stress from these situations has made me feel queasy or nauseous. | |

| Thinking about these situations can make it difficult to have an appetite. | |

| I appreciate my coworkers’ attempts to support me, but their efforts can come at the wrong time. | Colleague Support |

| Discussing what happened with my colleagues provides me with a sense of relief. | |

| My colleagues can be indifferent to the impact these situations have had on me. | |

| My colleagues help me feel that I am still a good healthcare provider despite any mistakes I have made. | |

| I feel that my supervisor treats me appropriately after these occasions. | Supervisor Support |

| My supervisor’s responses are fair. | |

| My supervisor blames individuals. | |

| I feel that my supervisor evaluates these situations in a manner that considers the complexity of patient care practices. | |

| My organization understands that those involved may need help to process and resolve any effects they may have on care providers. | Institutional Support |

| My organization offers a variety of resources to help me get over the effects of involvement with these instances. | |

| The concept of concern for the well-being of those involved in these situations is not strong at my organization. | |

| I look to close friends and family for emotional support after one of these situations happens. | Non-Work-Related Support |

| The love from my closest friends and family helps me get over these occurrences. | |

| Following my involvement, I experienced feelings of inadequacy regarding my patient care abilities. | Professional Self-Efficacy |

| My experience makes me wonder if I am not really a good healthcare provider. | |

| After my experience, I became afraid to attempt difficult or high-risk procedures. | |

| These situations do not make me question my professional abilities. | |

| My experience with these events has led to a desire to take a position outside of patient care. | Turnover Intentions |

| Sometimes the stress from being involved with these situations makes me want to quit my job. | |

| My experience with an adverse patient event or medical error has resulted in me taking a mental health day. | Absenteeism |

| I have taken time off after one of these instances occurs. | |

| The ability to immediately take time away from my unit for a little while. | Desired Forms of Support |

| A specified peaceful location that is available to recover and recompose after one of these types of events. | |

| A respected peer to discuss the details of what happened. | |

| An employee assistance program that can provide free counseling to employees outside of work. | |

| A discussion with my manager or supervisor about the incident. | |

| The opportunity to schedule a time with a counselor at my hospital to discuss the event. | |

| A confidential way to get in touch with someone 24 hours a day to discuss how my experience may be affecting me. |

| Standardized Factor Loadings | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factors / Items | Min | Max | M | SD | Model 1 | Model 2 |

| Psychological Distress | 1.00 | 5.00 | 3.46 | 1.22 | ||

| 1. I have felt embarrassment from these events. | 1.00 | 5.00 | 3.44 | 1.51 | .694 | .698 |

| 2. My involvement in these types of events has made me fearful of future occurrences. | 1.00 | 5.00 | 3.67 | 1.48 | .734 | .733 |

| 3. My experiences have made me feel miserable. | 1.00 | 5.00 | 3.12 | 1.50 | .792 | .791 |

| 4. I feel deep remorse for my past involvement in these types of events. | 1.00 | 5.00 | 3.65 | 1.40 | .824 | .823 |

| Physical Distress | 1.00 | 5.00 | 3.16 | 1.20 | ||

| 5. The mental weight of my experience is exhausting. | 1.00 | 5.00 | 3.38 | 1.35 | .866 | .861 |

| 6. My experience with these occurrences can make it difficult to sleep regularly. | 1.00 | 5.00 | 3.13 | 1.49 | .786 | .790 |

| 7. The stress from these situations has made me feel queasy or nauseated. | 1.00 | 5.00 | 3.46 | 1.42 | .758 | .761 |

| 8. Thinking about these situations has sometimes affected my appetite. | 1.00 | 5.00 | 2.65 | 1.43 | .676 | .677 |

| Colleague Support | 1.00 | 5.00 | 3.65 | 1.01 | ||

| 9. I appreciate my coworkers’ attempts to console me, but their efforts can come at the wrong time. | 1.00 | 5.00 | 2.94 | 1.24 | NA | |

| 10. Discussing what happened with my colleagues provides me with a sense of relief. | 1.00 | 5.00 | 3.54 | 1.23 | NA | .749 |

| 11. My colleagues can be indifferent to the impact these situations have had on me. | 1.00 | 5.00 | 3.00 | 1.26 | NA | |

| 12. My colleagues help me feel that I am still a good healthcare provider despite any mistakes I have made. | 1.00 | 5.00 | 3.76 | 1.17 | NA | .549 |

| Supervisor Support | 1.00 | 5.00 | 3.29 | 1.19 | ||

| 13. I feel that my supervisor treats me appropriately after these occasions. | 1.00 | 5.00 | 3.33 | 1.38 | .893 | .897 |

| 14. My supervisor’s responses are fair. | 1.00 | 5.00 | 3.29 | 1.40 | .959 | .954 |

| 15. My supervisor blames individuals. | 1.00 | 5.00 | 3.33 | 1.47 | .687 | .687 |

| 16. I feel that my supervisor evaluates these situations in a manner that considers the complexity of patient care practices. | 1.00 | 5.00 | 3.20 | 1.34 | .658 | .661 |

| Institutional Support | 1.00 | 5.00 | 2.36 | 1.05 | ||

| 17. My organization understands that those involved may need help to process and resolve any effects they may have on care providers. | 1.00 | 5.00 | 2.45 | 1.30 | .832 | .833 |

| 18. My organization offers a variety of resources to help me get over the effects of involvement with these instances. | 1.00 | 5.00 | 1.96 | 1.10 | .802 | .802 |

| 19. The concept of concern for the well-being of those involved in these situations is not strong at my organization. | 1.00 | 5.00 | 2.67 | 1.39 | .585 | .584 |

| Non-Work-Related Support | 1.00 | 5.00 | 3.68 | 1.12 | ||

| 20. I look to close friends and family for emotional support after one of these situations happens. | 1.00 | 5.00 | 3.44 | 1.27 | 1.038 | .834 |

| 21. The love from my closest friends and family helps me recover from these occurrences. | 1.00 | 5.00 | 3.91 | 1.21 | .607 | .756 |

| Professional Self-Efficacy | 1.00 | 5.00 | 2.41 | 1.24 | ||

| 22. Following my involvement, I experienced feelings of inadequacy regarding my patient care abilities. | 1.00 | 5.00 | 2.17 | 1.32 | .858 | .857 |

| 23. My experience makes me wonder if I am not really a good healthcare provider. | 1.00 | 5.00 | 2.46 | 1.39 | .846 | .848 |

| 24. After my experience, I became afraid to attempt difficult or high-risk procedures. | 1.00 | 5.00 | 2.61 | 1.46 | .786 | .786 |

| 25. These situations do not make me question my professional abilities. | 1.00 | 5.00 | 2.48 | 1.42 | -.002 | |

| Turnover Intentions | 1.00 | 5.00 | 2.60 | 1.45 | ||

| 26. My experience with these events has led to a desire to take a position outside of patient care. | 1.00 | 5.00 | 2.53 | 1.48 | .939 | .941 |

| 27. Sometimes the stress from being involved with these situations makes me want to quit my job. | 1.00 | 5.00 | 2.66 | 1.51 | .945 | .944 |

| Absenteeism | 1.00 | 5.00 | 2.42 | 1.26 | ||

| 28. My experience with an adverse patient event or medical error has resulted in me taking a mental health day. | 1.00 | 5.00 | 1.96 | 1.39 | .552 | .558 |

| 29. I have taken time off after one of these instances occurs. | 1.00 | 5.00 | 2.89 | 1.52 | .903 | .894 |

| Desired Forms of Support | 1.00 | 5.00 | 3.98 | 0.99 | ||

| 30. The ability to immediately take time away from my unit for a little while | 1.00 | 5.00 | 3.36 | 1.45 | .498 | |

| 31. A specified peaceful location that is available to recover and recompose after one of these types of events | 1.00 | 5.00 | 3.55 | 1.40 | .588 | .567 |

| 32. A respected peer to discuss the details of what happened | 1.00 | 5.00 | 4.18 | 1.10 | .707 | .706 |

| 33. An employee assistance program that can provide free counseling to employees outside of work | 1.00 | 5.00 | 4.01 | 1.28 | .864 | .865 |

| 34. A discussion with my manager or supervisor about the incident | 1.00 | 5.00 | 3.77 | 1.36 | .431 | |

| 35. The opportunity to schedule a time with a counselor at my hospital to discuss the event | 1.00 | 5.00 | 4.01 | 1.23 | .839 | .843 |

| 36. A confidential way to get in touch with someone 24 hours a day to discuss how my experience may be affecting me | 1.00 | 5.00 | 4.20 | 1.20 | .672 | .683 |

| This study | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factors | Model 1 | Model 2 | Original | Turkish | Italian | Korean | Chinese | Argentinian |

| Psychological Distress | .85 | .85 | .83 | .86 | .72 | .83 | .83 | .74 |

| Physical Distress | .86 | .86 | .87 | .83 | .69 | .87 | .92 | .70 |

| Colleague Support | .27 | .58 | .61 | .78 | .73 | .61 | .59 | .56 |

| Supervisor Support | .87 | .87 | .87 | .86 | .77 | .87 | .80 | .44 |

| Institutional Support | .76 | .76 | .64 | .88 | .75 | .64 | .60 | .79 |

| Non-Work-Related Support | .77 | .77 | .84 | .87 | .74 | .84 | .84 | .84 |

| Professional Self-Efficacy | .66 | .86 | .79 | .84 | .71 | .79 | .61 | .85 |

| Turnover Intentions | .94 | .94 | .89 | .89 | .74 | .81 | .92 | .71 |

| Absenteeism | .66 | .66 | .86 | .86 | .73 | .88 | .88 | .73 |

| Desired Forms of Support | .84 | .84 | ||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).