1. Introduction

Rubber O-ring seals are one of the most commonly used sealing structures in mechanical systems [

1]. However, during the production of rubber rings, because of the instability of the manufacturing process, some undesirable problems can occur after plastic molding. Common problems include cracks (

Figure 1(a)), chips (

Figure 1(b)), impurities (

Figure 1(c)), and wear (

Figure 1(d)) [

2]. These defects can directly lead to the poor sealing of seals and cause leakage, which in turn can lead to major accidents [

3]. In the current industrial manufacturing landscape, the identification of flaws in O-rings mainly depends on manual inspection. This approach not only amplifies production expenses and augments the workload for laborers, but also leads to reduced efficiency in detection and substantial inaccuracies, thereby compromising the reliability of the results.

Machine vision inspection technology, characterized by its non-contact, online, objective, and automated attributes, presents significant advantages and is well-suited for product inspection in modern manufacturing industries [

4]. However, the machine vision-based approach is reliant on manually designed defect feature, rendering it principally appropriate for detecting surface defects in products with uniform shapes and singular coloration. Nonetheless, the manual extraction of surface defect features in practical production remains a challenging task, often impeding accurate detection. Although numerous sets of defect templates can be designed using manual defect feature extraction, it can still only describe a finite number of faults and is unable to identify new types of defects. When traditional methods encounter complex and irregular data, they are not only difficult to apply but may also require complex post-processing procedures. Therefore, the sole application of machine vision technology is not entirely suitable for the industrial inspection of rubber rings.

In recent years, deep learning algorithms based on Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) have gained considerable application in the field of detection [

5]. These methods are used for industrial defect detection when the defect types are known and sufficient labeled samples are available, or when the problem of the multi-classification of defect types needs to be solved. In an application of bridge defect detection using CNNs, Cha

et al. [

6] presented a two-stage detector based on the Faster R-CNN to improve detection accuracy and changed the backbone network to ZF-net to improve the check speed. He

et al. [

7] improved the detection accuracy of steel plate defects using a multilevel feature fusion network based on a CNN. Li

et al. [

8] detected steel surface defects based on a single-stage detector ("You Only Look Once [YOLO]) and fused shallow features to improve the detection of fine defects. Zhang

et al. [

9] used YOLOv3 [

10] to detect bridge defects and used migration learning, batch renormalization, and focal loss to improve detection performance. Chen

et al. [

11] combined DenseNet [

12] with YOLOv3 to detect LED defects.

According to the cited literature, the core developmental philosophy of CNNs in defect detection is centered on the use of multi-scale fusion and data enhancement to improve detection accuracy. Rubber rings are in great demand and produced in large quantities in various industries. Fast and precise rubber ring defect detection enables the timely rejection of defective products. Numerous researchers have concentrated on lightweight neural networks as a solution to the issue of how to increase the detection speed while maintaining the highest level of detection accuracy. Iandola

et al. [

13] proposed SqueezeNet, used a 1 × 1 filter to replace the 3 × 3 filter, reduced the number of input channels of the 3 × 3 filter, and used the Fire module, which made its network size 50 times smaller than that of AlexNet, but maintained the same accuracy. Zhang

et al. [

14] proposed ShuffleNet using point-by-point group convolution and channel shuffling to greatly reduce the computational cost while maintaining accuracy. Howard

et al. [

15] proposed MobileNets, which use deep separable convolution instead of normal convolution and greatly reduce the computational effort of neural networks. While universal lightweight networks have contributed to network size reduction, there exists a considerable scope for enhanced optimization in neural networks tailored to particular scenarios.

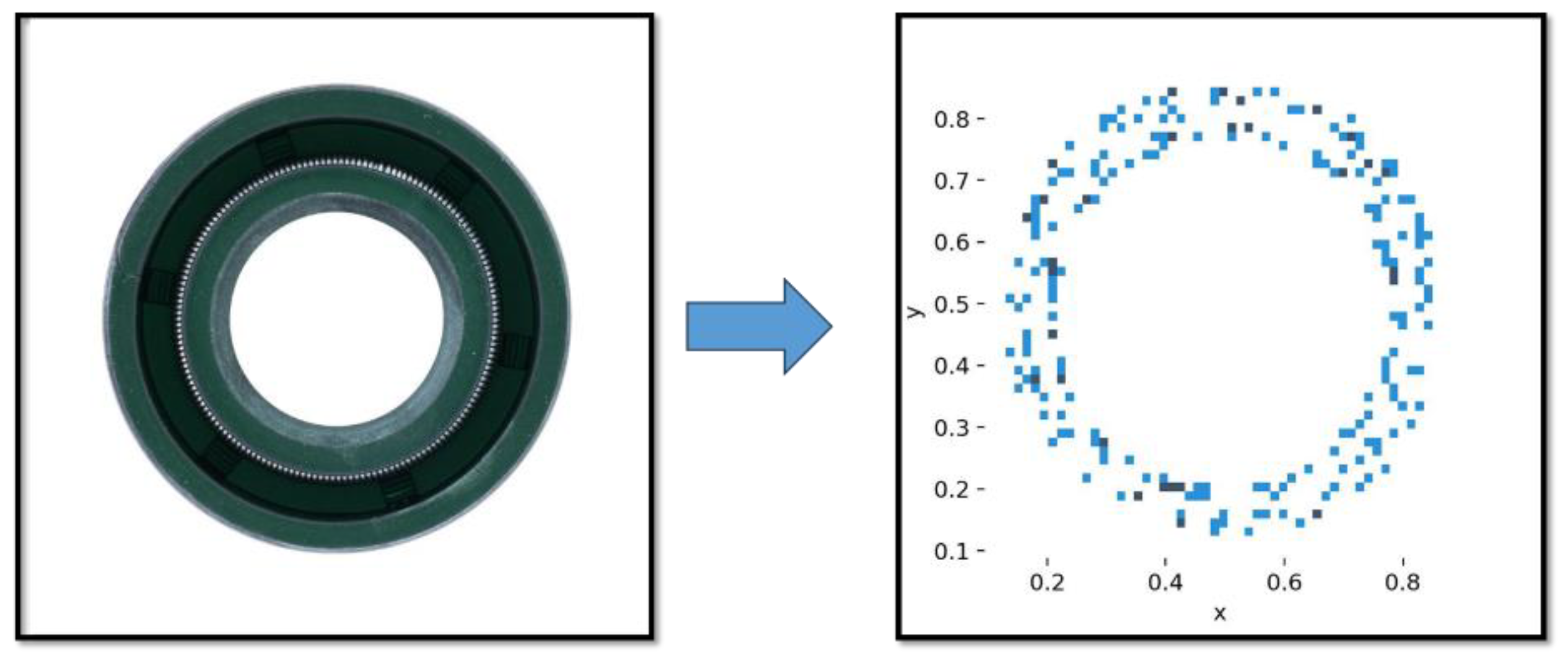

Unlike other industrial parts, the unique shape of rubber O-rings results in a notably regular distribution of defects. Standard convolution processes do not consider the targeted detection areas, they represent an inefficient use of resources in the detection of defects in rubber O-rings. Clearly, defects in rubber O-rings are confined to the surface, and the blank space in the center of the images does not require detection (

Figure 2). However, standard convolution processes involve convolving each pixel in an image. To mitigate this inefficiency, we have introduced preprocessing techniques, including image inversion, which have demonstrated considerable effectiveness.

In the meanwhile, Han

et al. [

16] discovered significant redundancy in the intermediate convolutional layers computed by CNN-based neural networks. As a result, they proposed GhostNet as a replacement for convolutional computation that uses partial linear transformations to minimize computational cost. However, replacing all the convolutional modules with Ghost modules in GhostNet does not exactly support their findings: only some of the convolutional layers have similar linear relationships between feature maps. Hence, we propose a YOLO (You only look once) network optimization method based on Ghost module to identify the most suitable replacement layers and replace the ordinary convolutional modules with Ghost modules, combining digital image processing technique, which greatly improves the detection efficiency. A formula has been proposed for assessing the network. Our methodology facilitates the identification of the most optimal positions for replacing convolutional layers. The optimized network thus achieved effectively balances efficiency with accuracy. Compared with the original network, the network size decreased by 30.5% and the computational cost decreased by 23.1% whereas average precision only decreased by 1.8%.

2. Related Work

The expression YOLO signifies that the neural network can generate results by examining the image only once. From YOLOv1 to YOLOv7, although it still requires a large number of images for training, its demand on an extensive dataset decreases significantly [

17,

18,

19,

20,

21]. The YOLO family's grandmaster, YOLOv5, is built on Python, which greatly expands its range of potential applications. To decrease the parameters and increase detection accuracy, respectively, YOLOv5 also uses the C3 module and Focus module. Because the use of algorithmic fusion is clearly increasing, YOLO's evolution will support more algorithmic fusion. In this paper, we attempt to reduce feature redundancy in the YOLOv5 model by employing the Ghost module. Specifically, we replace certain convolutional layers within YOLOv5 with Ghost modules, aiming to decrease the number of parameters.

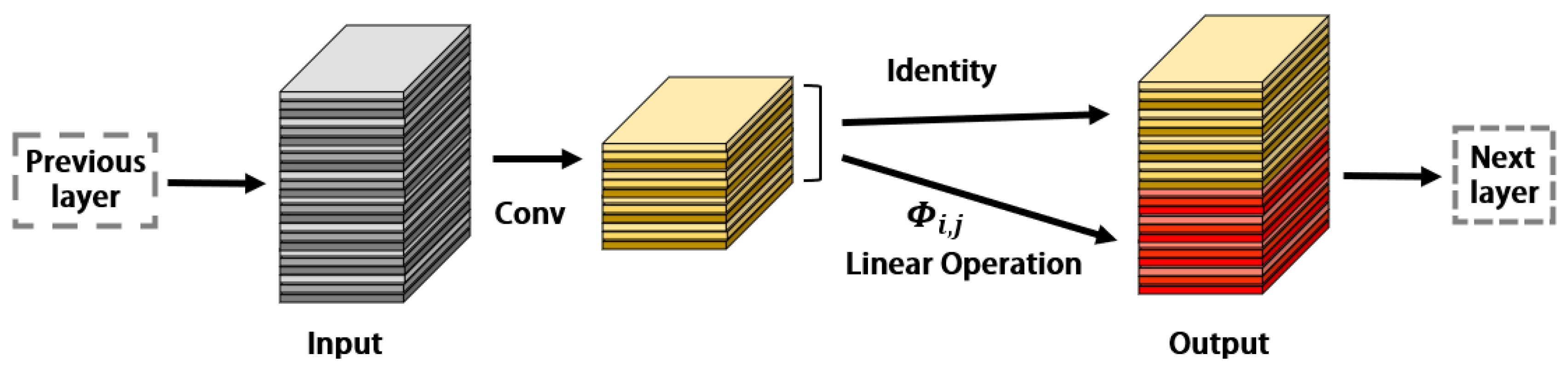

2.1. Ghost Module

Trained deep neural networks often integrate rich or even redundant feature maps to achieve a thorough understanding of the input data. This increases the computational load of the model and consequently reduces its processing speed. To remove extra feature information and minimize computation, GhostNet uses a partially linear operation as a replacement for convolution. The schematic is shown in

Figure 3. In practice, the GhostNet processes input data denoted by

, where

c is the number of input channels, and

h and

w are the height and width of the input data, respectively. Additionally, the first step of the operation is to generate m intrinsic feature maps

using a primary convolution:

where ∗ is the convolution operation, the bias term is omitted for simplicity, and

represents the convolution filters in this layer. Additionally,

and

are the height and width of the output data, respectively, and k × k is the kernel size of convolution filters

. To further obtain the n (n ≥ m) feature maps, a series of cheap linear operations are applied to each intrinsic feature in Y to generate s Ghost features according to the following function:

where

is the

-th intrinsic feature map in Y,

is the

-th (except the last) linear operation for generating the

-th Ghost feature map

.

can have one or more Ghost feature maps

. The last

is the identity mapping for preserving the intrinsic feature maps.

2.2. Process of Replacement

Using the Ghost module reduces computation; however, their team created a brand new network model and added a complicated residual structure. The new network structure only approximates the metrics of the original network after more convolutional layers are added, which is clearly contrary to the original finding. To obtain a slight decrease in accuracy but a substantial boost in training and detection performance, we believe that only a few crucial convolutional modules need to be altered while the original network topology is maintained. However, for various structures of CNNs, it is still unknown how many and which convolutional modules should be replaced to achieve the best results. Therefore, we propose a YOLO-based Ghost module replacement optimization method, which we use to find the optimal replacement scheme, and the best balance between accuracy and speed.

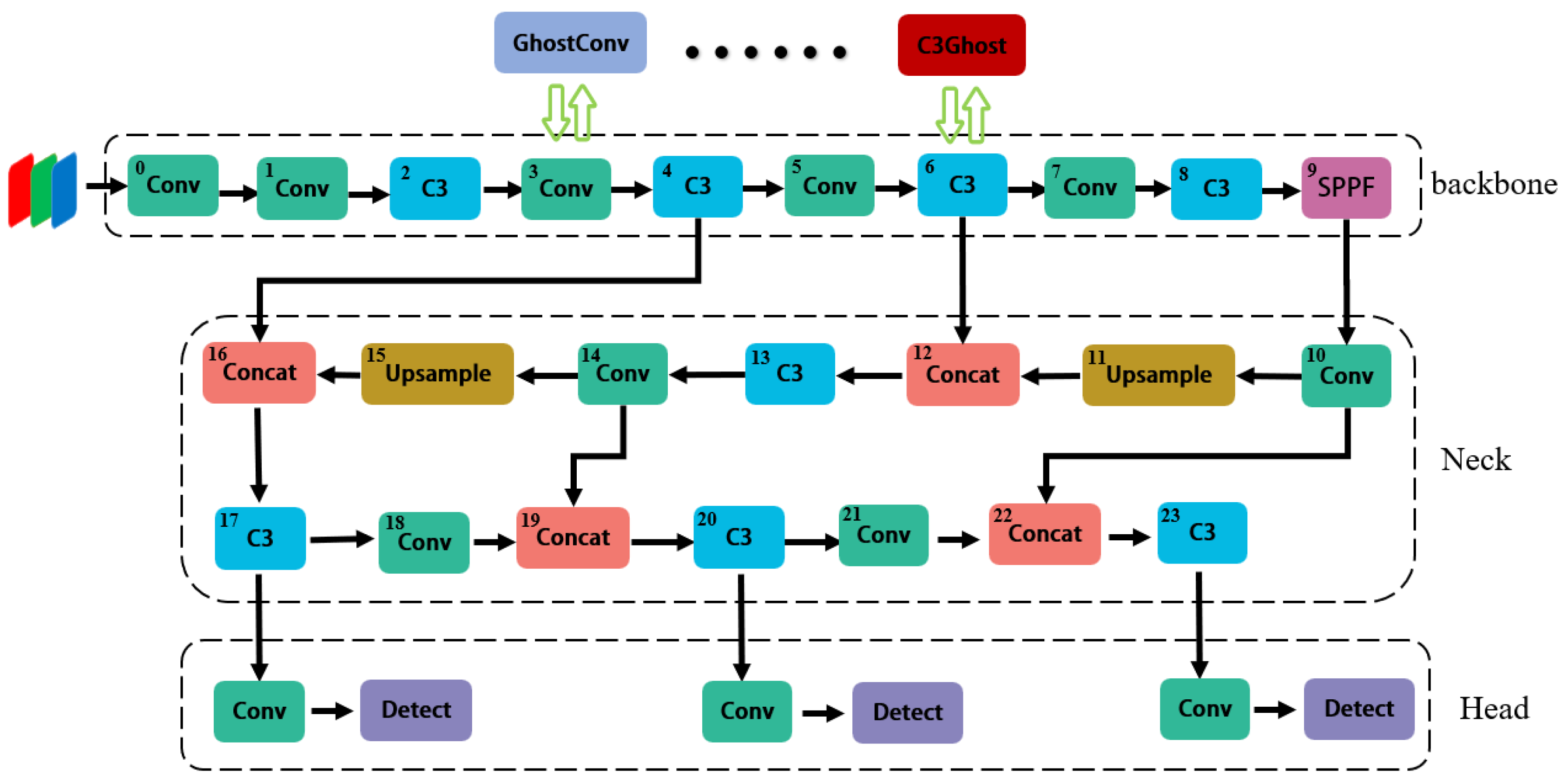

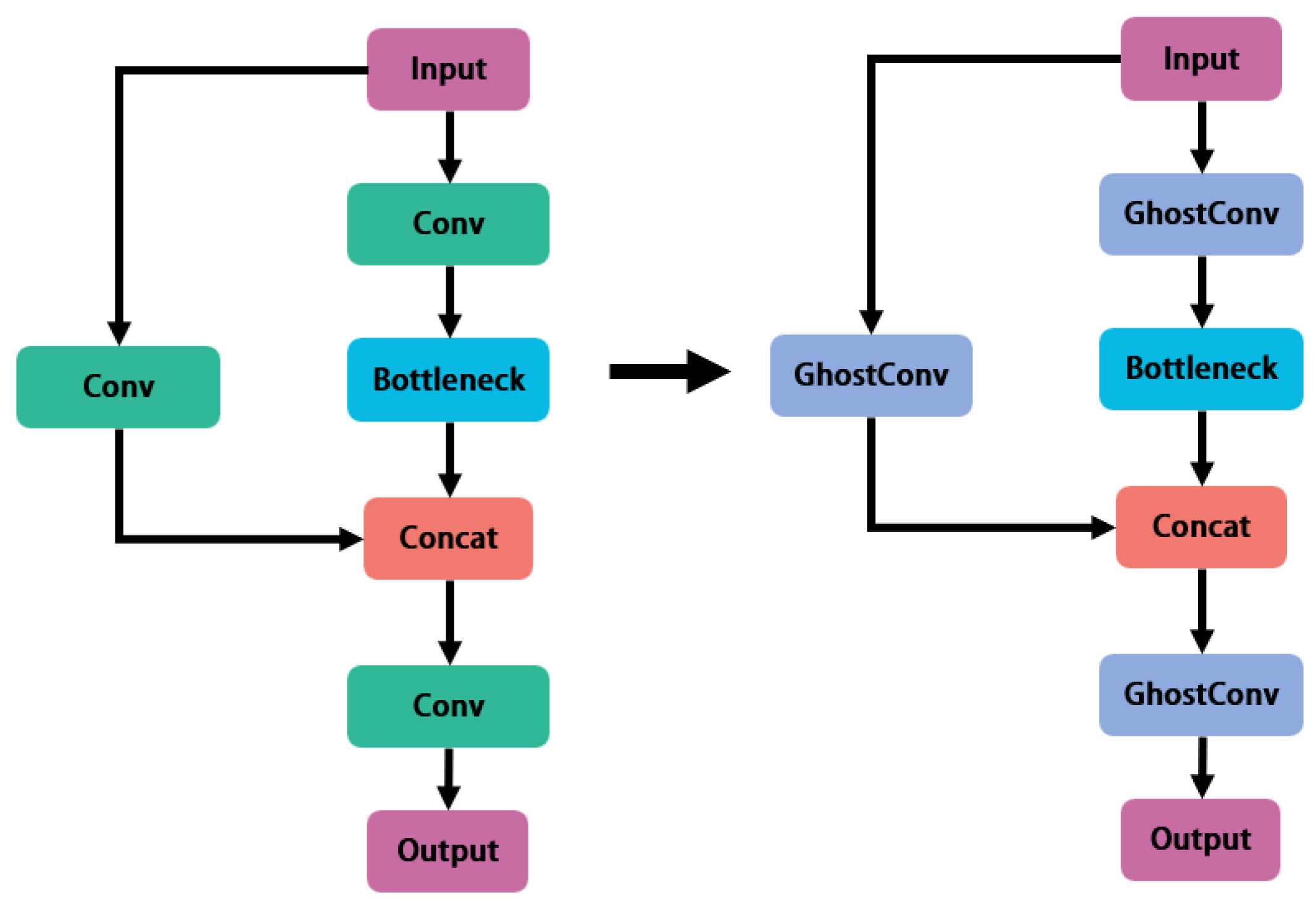

The schematic diagram of the operation is shown in

Figure 4. We use a layer-by-layer replacement method to find the optimal solution for Ghost module replacement in YOLOv5. We use the GhostConv and C3Ghost modules in place of the original Conv and C3 modules, respectively (

Figure 5). We split the experimental procedure into several rounds. We replace all the CNNs' convolutional layers once in each round by the matching Ghost modules, and grade the results using the weighted average of the replacement's mAP50 and mAP50-95, and the parameter ratios of the replaced and original networks. We reserve the best replacement with the highest score in a round of training. After several rounds, we optimize the CNNs. We split YOLOv5's network into 30 sections and label 24 of them from 0 to 23 so that we can discriminate between replacement rounds and convolutional layers.

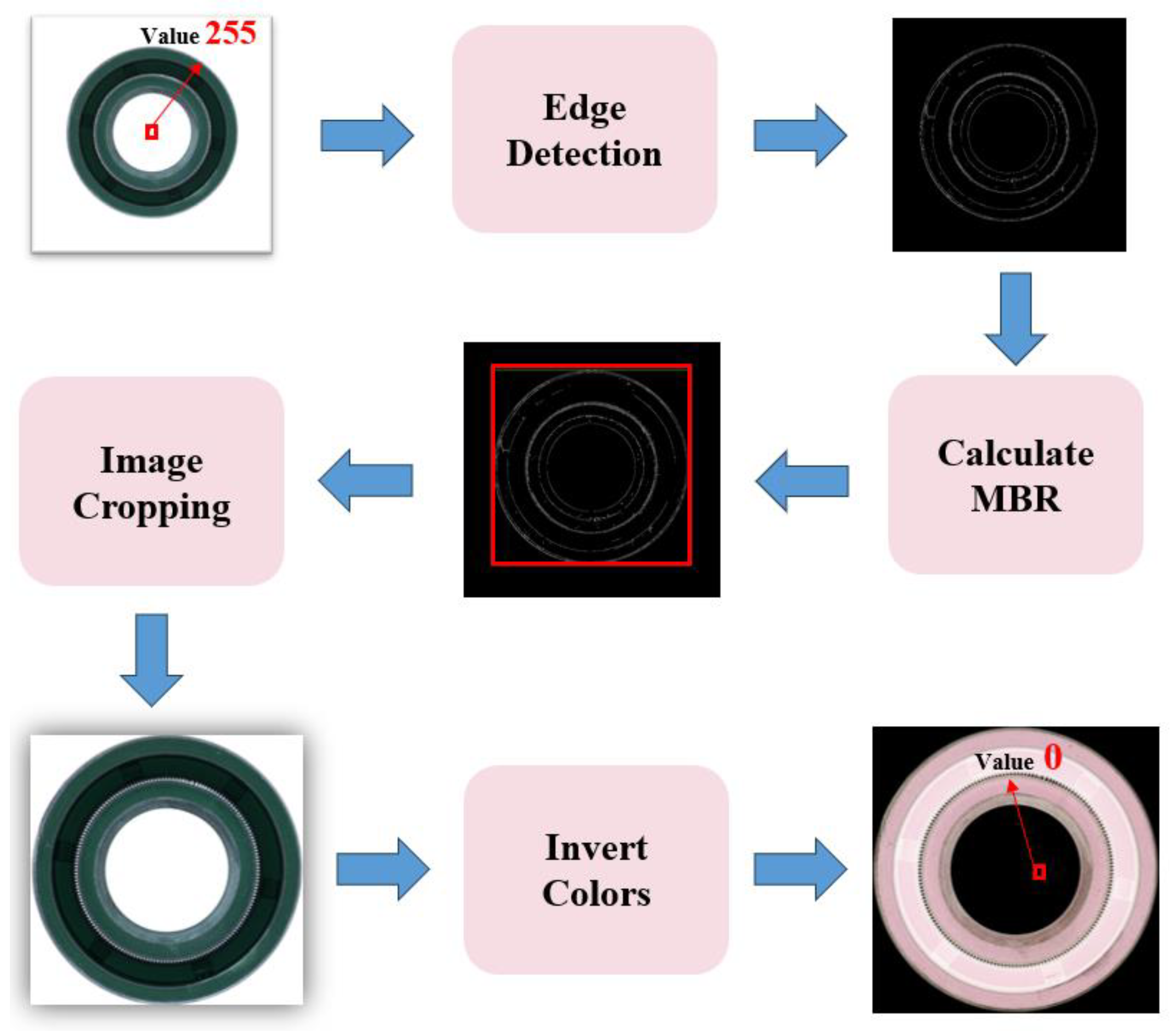

2.3. Preprocessing of an Image

In a practical production process, we obtained rubber ring images characterized by high resolution and minimal background noise, as shown in

Figure 6. We introduced a set of digital image processing algorithms for rubber rings to make them better suited for defect identification. First, we created grayscale images from the obtained rubber ring images. Subsequently, we used edge detection to identify the images' edges. Third, we cropped the images to remove the white background and enlarge the defect detection area within the standard image. Next, we inverted the image to lower the pixel value of the white background at the center to zero while maintaining the integrity of the original image. When the detection process was complete, we inverted the image back to its original state. The entire image processing procedure is illustrated in

Figure 7.

3. Experiment

3.1. Validating Feasibility on the COCO Dataset

To test our proposed novel network structure idea, we verified the feasibility of the method using the COCO dataset. We used AP to evaluate the accuracy of the network. The AP metric can be calculated as follows:

where TP, FP, and FN represent the numbers of true positive, false positive, and false negative samples, respectively.

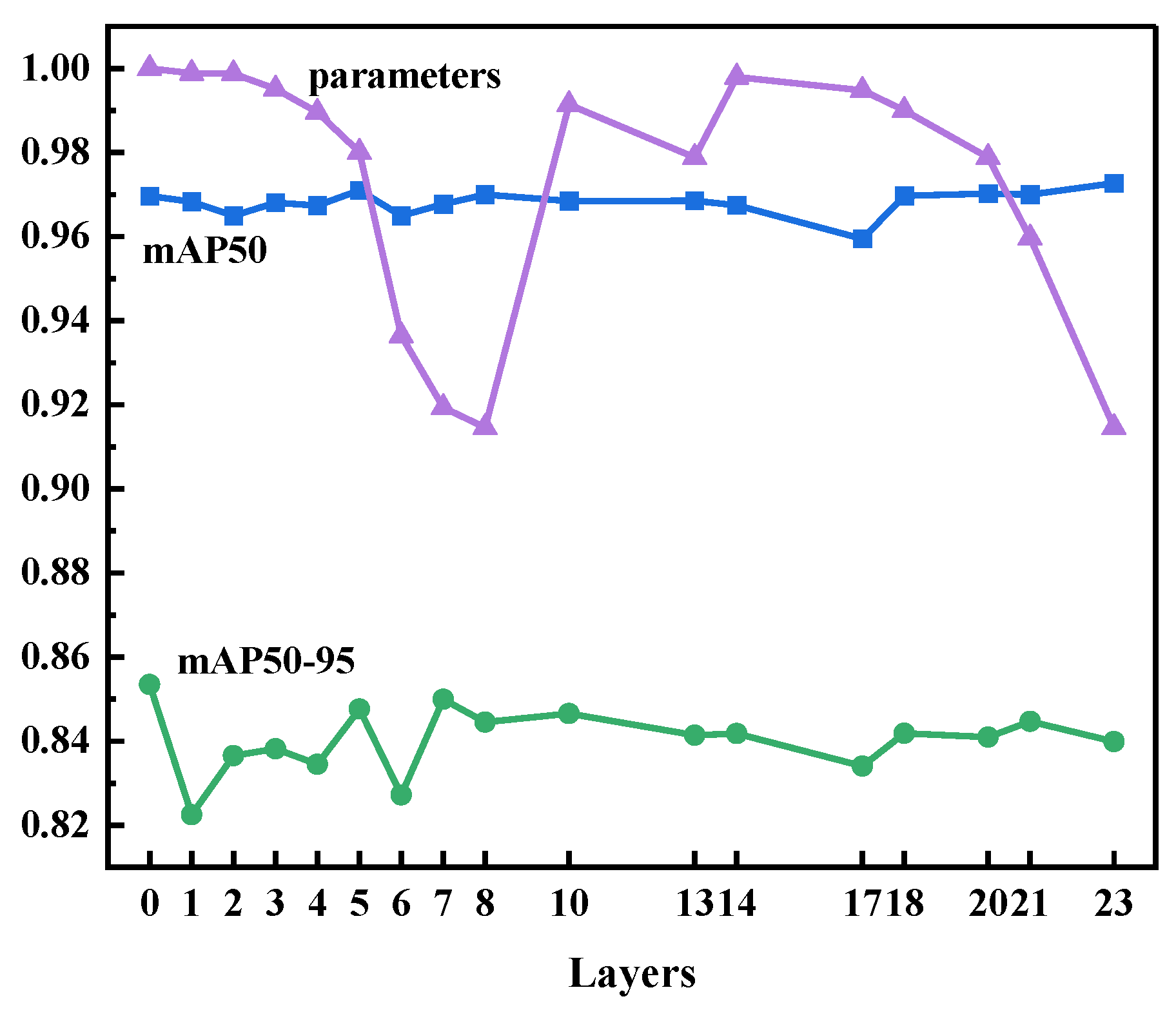

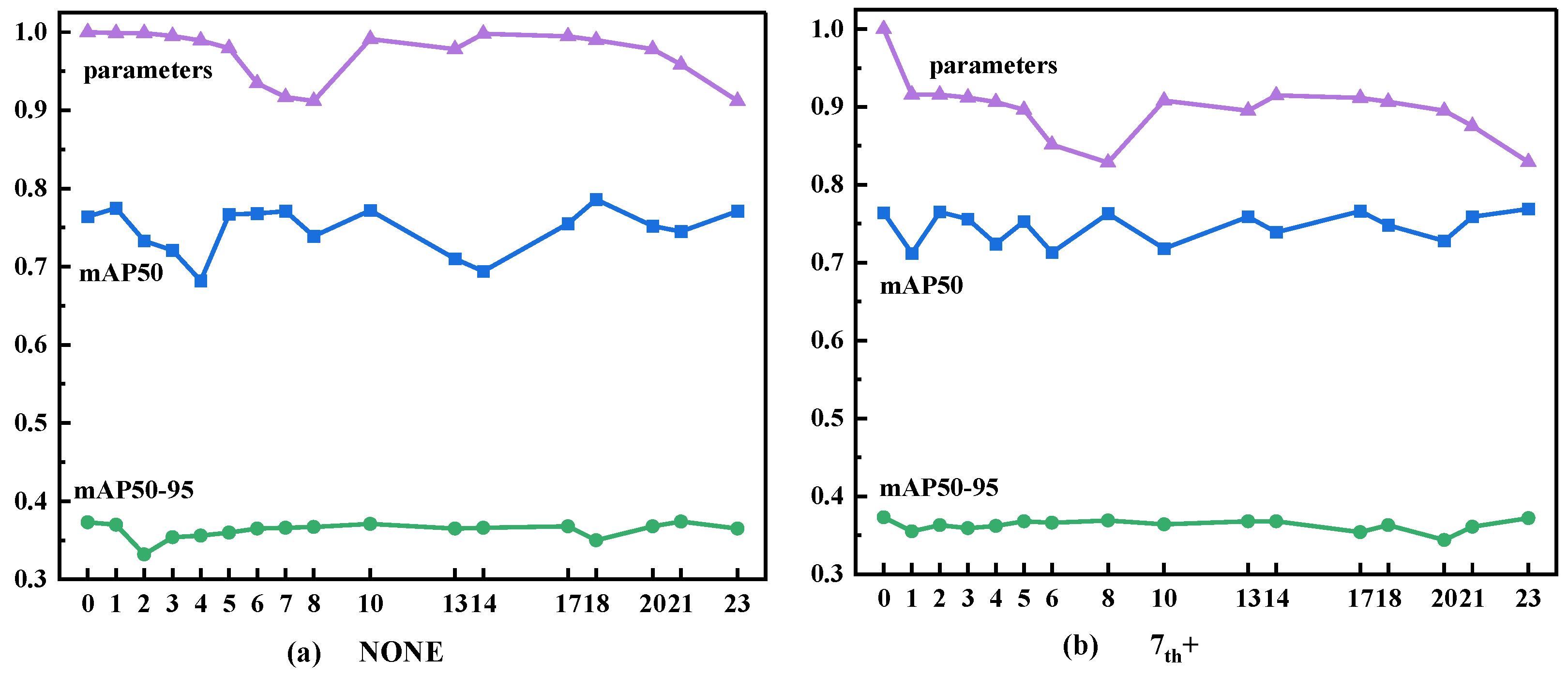

We did not choose to replace convolutional layer 0; hence, all the 0s in the

Figure 8,

Figure 9 and

Figure 10 correspond to data from the original network. Let the parameters of the original network equal 1. We proposed a formula to examine the performance of the optimized network. The

mAP50 and

mAP50-95 are considered equally important and therefore become the first term of the equation after averaging the two values. The second term is the

parameter, which has a negative coefficient since a smaller

parameter value results in a higher network

score. The formula for the performance score of each network in the replacement process is

where

parameter [0,1] represents the ratio of parameters of the optimized network to those of the original network, and

a and

b refer to two weighting factors obtained from the COCO dataset.

To test our network architecture optimization method based on the Ghost module, we verified its feasibility on the COCO dataset. We achieved a good result by replacing certain convolutional layers with the Ghost module in YOLOv5's neural network. The network's performance was on par with that of the original network.

Figure 8 shows the performance data of the network after we replaced each convolutional layer. Clearly, the number of parameters decreased the most when we replaced convolutional layers 7, 8, and 23. After we synthetically analyzed the factors of mAP50, mAP50-95, and

parameter, we decided to conduct the next experiment based on replacing convolutional layer 7.

When we replaced layer 8, the number of parameters decreased the most: it reached 83% of the original value. However, the other metrics did not perform as well as expected. The number of parameters also decreased to less than 84% of the original value when we replaced convolutional layer 23, while

mAP50-95 increased by 0.1% and

mAP50 decreased by 2.0% (

Figure 8). As a result, we chose convolutional layer 23 as the second replaced convolutional layer.

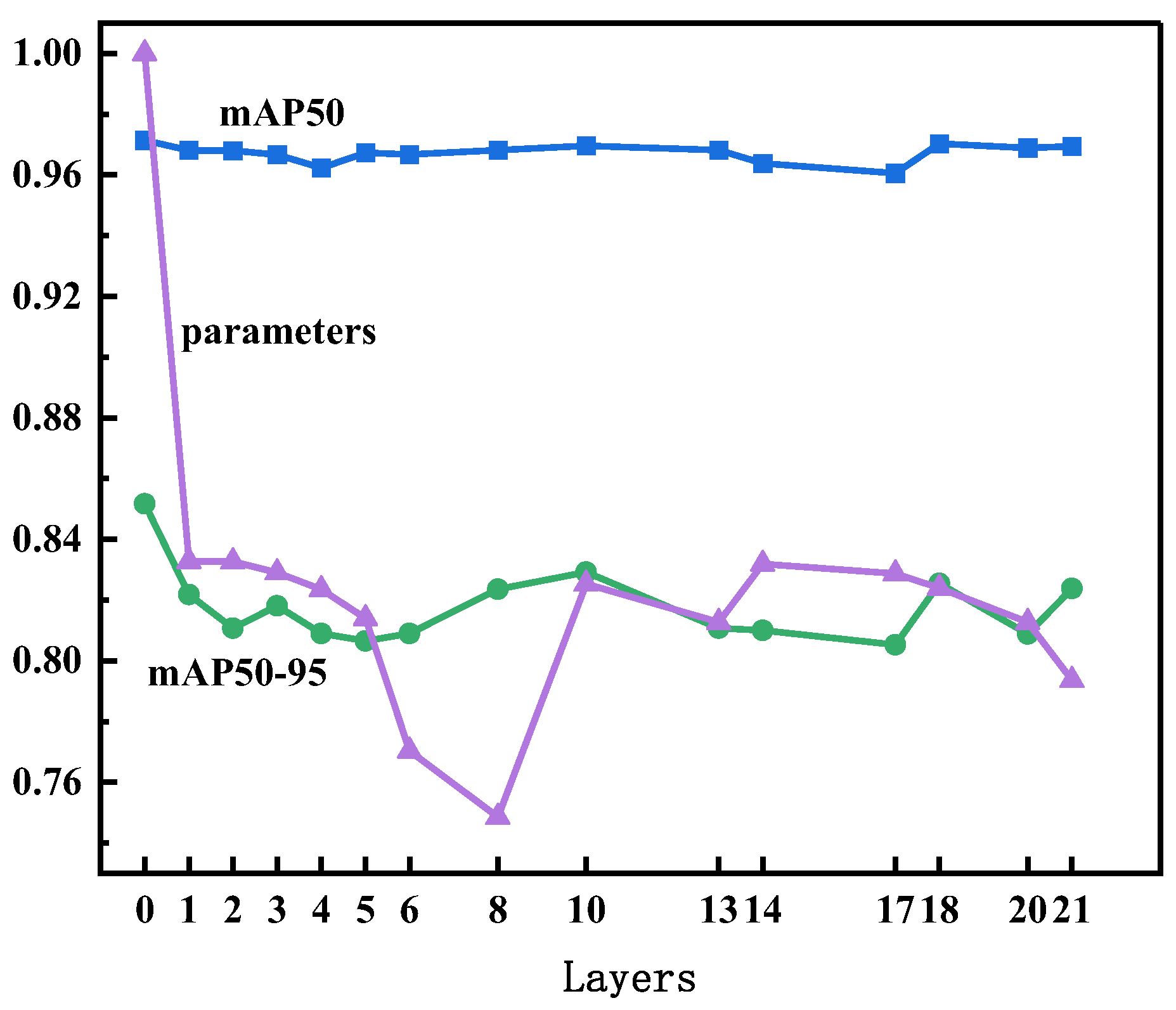

When we replaced three layers of the network, the findings were less surprising, as shown in

Figure 9. Because the remaining layers had fewer parameters compared with the two convolutional layers, the number of parameters did not reduce substantially. The results only became acceptable when we used the Ghost module to replace convolutional layer 8: mAP50 and mAP50-95 decreased by 0.3% and 2.2%, respectively. The total number of parameters decreased to 75% of the original value.

By replacing the three convolutional layers, we accomplished our aim of decreasing the number of network parameters while minimizing the impact on network performance. Our findings are supported by the results, which show that 1) the CNNs included redundant features; and 2) these redundancies were minimal. Therefore, we decided to finally optimize the structure of YOLOv5's neural network by replacing convolutional layers 7, 8, and 23 with the Ghost module.

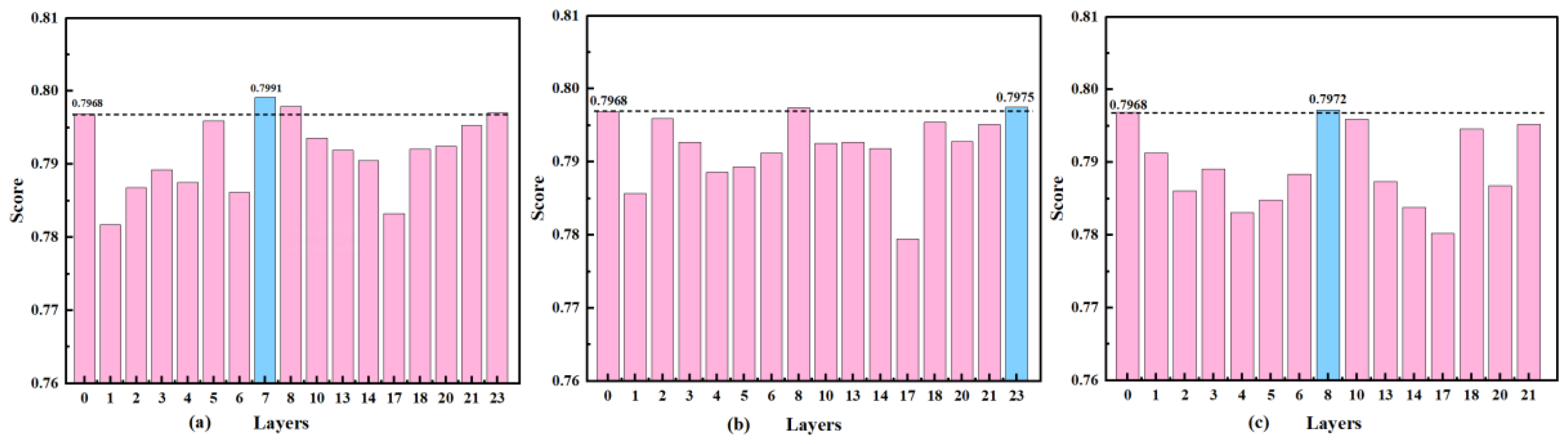

Our policy was that, when the score of the optimized network decreased below that of the original network, there was no more room for improvement in that specific network. According to the results for the optimized network and our optimization approach,

was 0.94 and

was -0.06. After we substituted the values of

and

into Eq. 6, we obtained the scores of the optimized networks (

Figure 11 (a), (b), (c)).

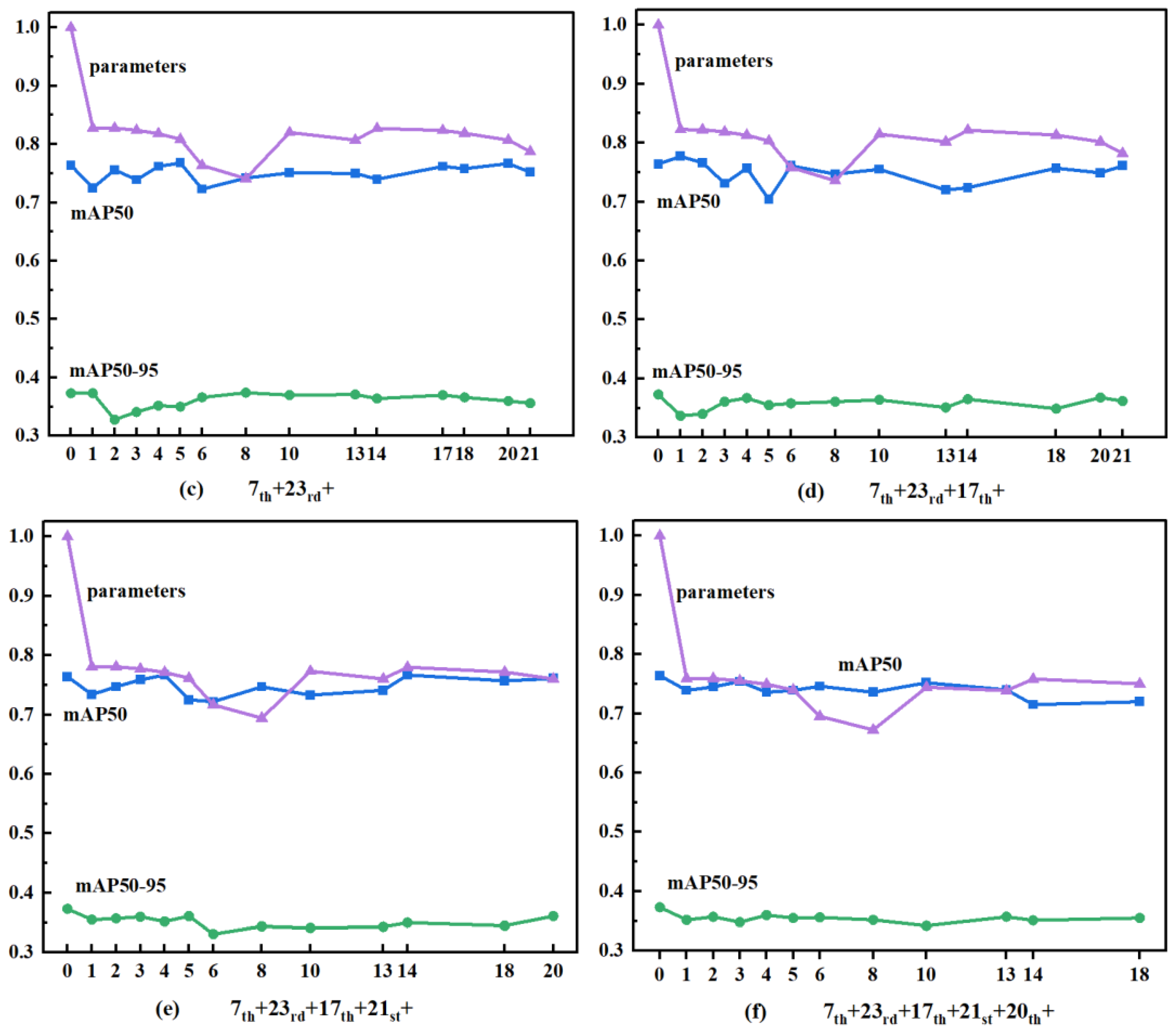

3.2. Experiment on the Rubber Ring Datasets

After we verified the feasibility of the network structure, we experimented on our own dataset using the same method. From the automatic optical inspection system, we collected 122 rubber ring images with defects. After applying preprocessing as outlined in Section 2.4 to the rubber ring image dataset, we used a layer-by-layer replacement approach to improve YOLOv5's neural network, as described in

Section 3.1. We trained the network for 300 epochs and selected the model with the highest score on the validation set as the final test model. We used the same method, but obtained slightly different results. The first replacement layer was still convolutional layer 7. The number of parameters decreased to 91.6% of those in the original network, with a mAP50-95 decrease of only 0.6% and mAP50 increase of 0.5% (

Figure 12(a)). We chose convolutional layer 23 again for the second replacement layer. The number of parameters decreased to 82.9% of the original network, with a mAP50-95 decrease of only 0.1% and mAP50 increase of 0.4% (

Figure 12(b)). The difference became visible with the third replacement layer. We choose convolutional layer 17 as the third replacement layer because it got the highest score. Although the number of parameters did not decrease substantially for this convolutional layer compared with those for the two previously replaced convolutional layers, the performance of the optimized network was comparable with that of the original network (

Figure 12(c)). We replaced the fourth convolutional layer because it was obvious that there was an opportunity to further optimize the network. When we used convolutional layer 21 as the fourth replacement layer, the number of parameters reduced to 78.2%, with a mAP50 and mAP50-95 decrease of 0.3% and 0.9%, respectively. We obtained the best results (

Figure 12(d)). We choose convolutional layer 20 as the fifth replacement layer and the number of parameters decreased to 76.0%, with a mAP50 and mAP50-95 decrease of 0.3% and 1.2%, respectively. We obtained the best results (

Figure 12(e)). We chose convolutional layer 6 for the sixth replacement layer and the number of parameters decreased to 69.5%, with a mAP50 and mAP50-95 decrease of 1.8% and 1.7%, respectively (

Figure 12(f)). We also intended to replace convolutional layer 8, which contained more parameters than other layers. Although replacing convolutional layer 8 can significantly reduce the number of parameters, its performance was not good according to the testing result. Therefore, for the rubber ring detection dataset, the replacement convolutional layers were convolutional layers 7, 23, 17, 21, 20, and 6. The scores after each round of network optimization are shown in

Table 1.

3.3. Analysis

Since this method is applicable to nearly all CNNs, we just compare the performance of the optimized network with that of the original network. The results of comparison are given in

Table 2. Because of the removal of the white background and the increase in the zero-pixel area, preprocessing can speed up the computation of the model. It took 0.156 hours instead of 0.186 hours to train 300 epochs after preprocessing, which highlights the improvement in training efficiency. The number of parameters remained the same, but training only consumed 83.9% of the initial time. Our network achieved a mAP of 0.746 when set the intersection over union (IoU) threshold at 0.5 (AP50) and an average AP of 0.356 when set IoU threshold from 0.5 to 0.95 with a step of 0.05 (AP50:95). Furthermore, our network only had 5.03 million parameters with 12.2 GFLOPs computational cost.

We believe that the variation in results for the same method was caused by differences in the datasets. When different datasets are processed, the same neural network does not exhibit the same level of redundancy, which is consistent with general knowledge. When complex datasets are processed, redundancy tends to be lower. When simple datasets are processed, there is more redundancy. Therefore, when the Ghost module is used to replace the convolutional layer, simpler datasets have a greater potential for network improvement. Additionally, we observed that, for YOLOv5 neural networks, redundancy was more likely to occur in the later or middle convolutional layers rather than the first few convolutional layers.

4. Conclusion

We proposed a neural network optimization method based on the Ghost module and combined it with pre-processed rubber rings. The main contributions of this study are as follows:

(a) We proposed a set of applicable image preprocessing methods for rubber ring surface defect detection, which reduced the training time of the network model.

(b) We proposed a method for neural network optimization based on the Ghost module to reduce the redundant information in the neural network. Then we determined the neural network's optimal balance of computing efficiency and accuracy.

(c) We found a qualitative relationship between the complexity of the dataset and neural network redundancy.

The test results for a dataset of 122 images of rubber ring defects show that our proposed method decreased the computational loss and computational time. The training time of the neural network discovered using our method reduced to 83.9% of that of the original network, the network size decreased by 30.5% and the computational cost decreased by 23.1%, whereas average precision only decreased by 1.8%. the network's training time decreased by 16.1% as a result of preprocessing. The 122 defective images were selected from a pool of 1,465 randomly acquired images. Thus, in an industrial inspection setting, a decline of 1.8% in average precision results in an increment of three misidentified images for every two thousand pictures analyzed. This loss is deemed entirely acceptable when weighed against the time and resource savings afforded by the network optimization.

Although the proposed network achieved good performance, there are still some limitations. For example, the quantitative relationship between network redundancy and dataset complexity is not clear; small datasets may weaken the performance of neural networks. In the future, we will collect more images to form larger datasets and continue to optimize the neural network.

References

- Liang, B.; Yang, X.; Wang, Z.; Su, X.; Liao, B.; Ren, Y.; Sun, B. Influence of Randomness in Rubber Materials Parameters on the Reliability of Rubber O-Ring Seal. Materials 2019, 12, 1566. [CrossRef]

- He Z, Liu J, Jiang L, et al. Oil seal surface defect detection using superpixel segmentation and circumferential difference[J]. International Journal of Advanced Robotic Systems, 2020, 17(6): 172988142097651. [CrossRef]

- Chandrasekaran, C.V. Rubber Seals for Fluid and Hydraulic Systems; William Andrew: Norwich, NY, USA, 2010; ISBN 978-0-8155-2075-7.

- Youcun Lu, Lin Duanmu, Zhiqiang (John) Zhai, Zongshan Wang, Application and improvement of Canny edge-detection algorithm for exterior wall hollowing detection using infrared thermal images, Energy and Buildings, Volume 274, 2022, 112421, ISSN 0378-7788. [CrossRef]

- CHEN J Q. Image recognition technology based on neural network[J]. IEEE Access, 2020, 8: 157161-157167. [CrossRef]

- Cha Y J, Choi W, Suh G, et al. Autonomous structural visual inspection using region-based deep learning for detecting multiple damage types. Comput-Aided Civil Infrastruct Eng, 2018, 33: 731–747. [CrossRef]

- He Y, Song K, Meng Q, et al. An end-to-end steel surface defect detection approach via fusing multiple hierarchical features. IEEE Trans Instrum Meas, 2020, 69: 1493–1504. [CrossRef]

- Li J, Su Z, Geng J, et al. Real-time detection of steel strip surface defects based on improved YOLO detection network. IFAC-Papers OnLine, 2018, 51: 76–81. [CrossRef]

- Zhang C, Chang C, Jamshidi M. Concrete bridge surface damage detection using a single-stage detector. Comput-Aided Civil Infrastruct Eng, 2020, 35: 389–409. [CrossRef]

- Redmon J, Farhadi A. Yolov3: an incremental improvement. 2018. ArXiv:1804.02767. [CrossRef]

- Chen S H, Tsai C C. SMD LED chips defect detection using a YOLOv3-dense model. Adv Eng Inf, 2021, 47: 101255. [CrossRef]

- Huang G, Liu Z, van der Maaten L, et al. Densely connected convolutional networks. In: Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 2017. 4700–4708.

- Iandola F N, Han S, Moskewicz M W, et al.SqueezeNet: AlexNet-level accuracy with 50x fewer parameters and <0.5MB model size[J]. 2016. [CrossRef]

- Zhang X, Zhou X, Lin M, et al. ShuffleNet: An Extremely Efficient Convolutional Neural Network for Mobile Devices[J]. 2017. [CrossRef]

- Diewald S, Mller A, Roalter L, et al. MobiliNet: A Social Network for Optimized Mobility[C]//Adjunct International Conference on Automotive User Interfaces & Interactive.

- K. Han, Y. Wang, Q. Tian, J. Guo, C. Xu and C. Xu, "GhostNet: More Features From Cheap Operations," 2020 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Seattle, WA, USA, 2020, pp. 1577-1586. [CrossRef]

- J. Redmon, S. Divvala, R. Girshick and A. Farhadi, "You Only Look Once: Unified, Real-Time Object Detection," 2016 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 2016, pp. 779-788. [CrossRef]

- J. Redmon and A. Farhadi, "YOLO9000: Better, Faster, Stronger," 2017 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Honolulu, HI, USA, 2017, pp. 6517-6525. [CrossRef]

- Redmon J, Farhadi A. YOLOv3: An Incremental Improvement[J]. arXiv e-prints, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Alexey Bochkovskiy, Chien-Yao Wang, Hong-Yuan Mark Liao; YOLOv4: Optimal Speed and Accuracy of Object Detection, arXiv preprint arXiv: 2004.10934. [CrossRef]

- Chien-Yao Wang, Alexey Bochkovskiy, Hong-Yuan Mark Liao: YOLOv7: Trainable bag-of-freebies sets new state-of-the-art for real-time object detectors, arXiv preprint arXiv: 2207.02696. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).