1. Introduction

Recently, with the swift advancement of renewable energy, effectively integrating these energy sources has become a significant challenge for power systems [

1,

2,

3,

4]. Particularly in China, thermal power continues to dominate the energy mix [

5]. Achieving the goals of carbon peaking and carbon neutrality as part of the energy transition [

6] makes advanced deep peak-shaving technologies in coal-fired power plants specifically critical [

7,

8,

9,

10]. This technology facilitates the stable operation of coal-fired power units at reduced load capacities, thereby enabling the electrical grid to integrate a higher proportion of renewable energy sources while concurrently ensuring grid stability [

11,

12,

13].

Supercritical and ultra-supercritical boilers, as core equipment in modern thermal power generation, have hydrodynamic characteristics and combustion efficiency that directly affect the operational safety and economic performance of the entire power plant [

14,

15,

16,

17]. During low-load operations, the water-cooled wall bears the full process from subcooled to superheated states of the working fluid, ensuring that the wall temperature remains within the permissible range for metal materials, which is crucial for the safe operation of the boiler [

18,

19,

20].

Previous studies [

21,

22,

23] indicate that when supercritical units operate under deep load-following conditions, their load response speed is slow, and coal consumption per unit of electricity significantly increases. Additionally, the water-cooled walls of the boiler face challenges in flow stability and thermal deviation, as the boiler load decreases, the high temperature area and flame move toward the side wall [

24], which can lead to overheating of metal tube walls and equipment damage [

25,

26]. Consequently, an exhaustive investigation into the hydrodynamic properties and wall temperature distribution within boiler systems under reduced-load conditions is crucial to guarantee the safety of operational units during such scenarios, enhance energy efficiency, and mitigate environmental pollution through the reduction of contaminant emissions.

Currently, numerous researchers [

23,

24,

27,

28,

29,

30] have conducted investigations into the hydrodynamic characteristics of boilers under low loads. Zhu et al. [

28] designed an orifice situated at the 50% threshold of the boiler's maximum continuous rating (BMCR), with the intention of enhancing the hydrodynamic performance of the water-cooled walls within an ultra-supercritical pressure boiler. The implemented design was found to facilitate consistent heat transfer efficacy across a spectrum of boiler loading scenarios, concurrently guaranteeing the integrity of the water-cooled wall's metallic temperature for safe operational parameters. Wan et al. [

29] investigated the hydrodynamic characteristics of the water-cooled walls in a 1000 MW ultra-supercritical boiler under 30% and 75% BMCR loads, finding that flow distribution was influenced by pipeline length and the horizontal non-uniformity of heat flux. Furthermore, the study showed that the outlet steam temperature exhibited an inverse relationship with flow rate. Zhou et al. [

30] explored the hydrodynamic behavior of a supercritical boiler at 30% BMCR load. When subjected to a 1.2 times heat flux disturbance, the flow pulsation within the furnace eventually stabilized, indicating that no flow instability occurs when operating at low loads. Chen et al. [

23] studied the hydrodynamic characteristics of the water-cooled wall system within a 600 MW supercritical boiler under 60%, 80%, and 100% BMCR loads. Their findings indicated that at 80% BMCR load, water temperature approached the boundary of the high specific heat capacity region, suggesting a risk of heat transfer deterioration. This condition requires careful monitoring to prevent overheating of the water-cooled wall tubes.

However, previous studies [

23,

24,

27,

28,

31] have mostly focused on conditions above 30% BMCR load, with limited research on the hydrodynamic characteristics at 30% BMCR load. Therefore, this study not only examines the mass flow distribution and pressure loss behavior of the water-cooled wall at 30% BMCR load but also delves into the correlation between wall temperature variation and the material's safe operating limits.

Additionally, the hydrodynamic computational model formulated in this study treats the water-cooled wall flow network as an interconnected system of flow channels, pressure junctions, and connecting conduits. A series of pressure equations for each component is established based on the principles of mass conservation, momentum conservation, energy conservation, and the fundamental equations of fluid mechanics [

16,

32,

33,

34].

This study investigates a 1000 MW supercritical boiler by developing a mathematical model to analyze the hydrodynamic behavior and wall temperature distribution in its water-cooled walls. The model evaluates the hydrodynamic behavior and wall temperature safety at 30% BMCR load. The findings are significant for enhancing the peak-shaving capability of the boiler.

2. Mathematical Model

2.1. Hydrodynamic Calculation Method

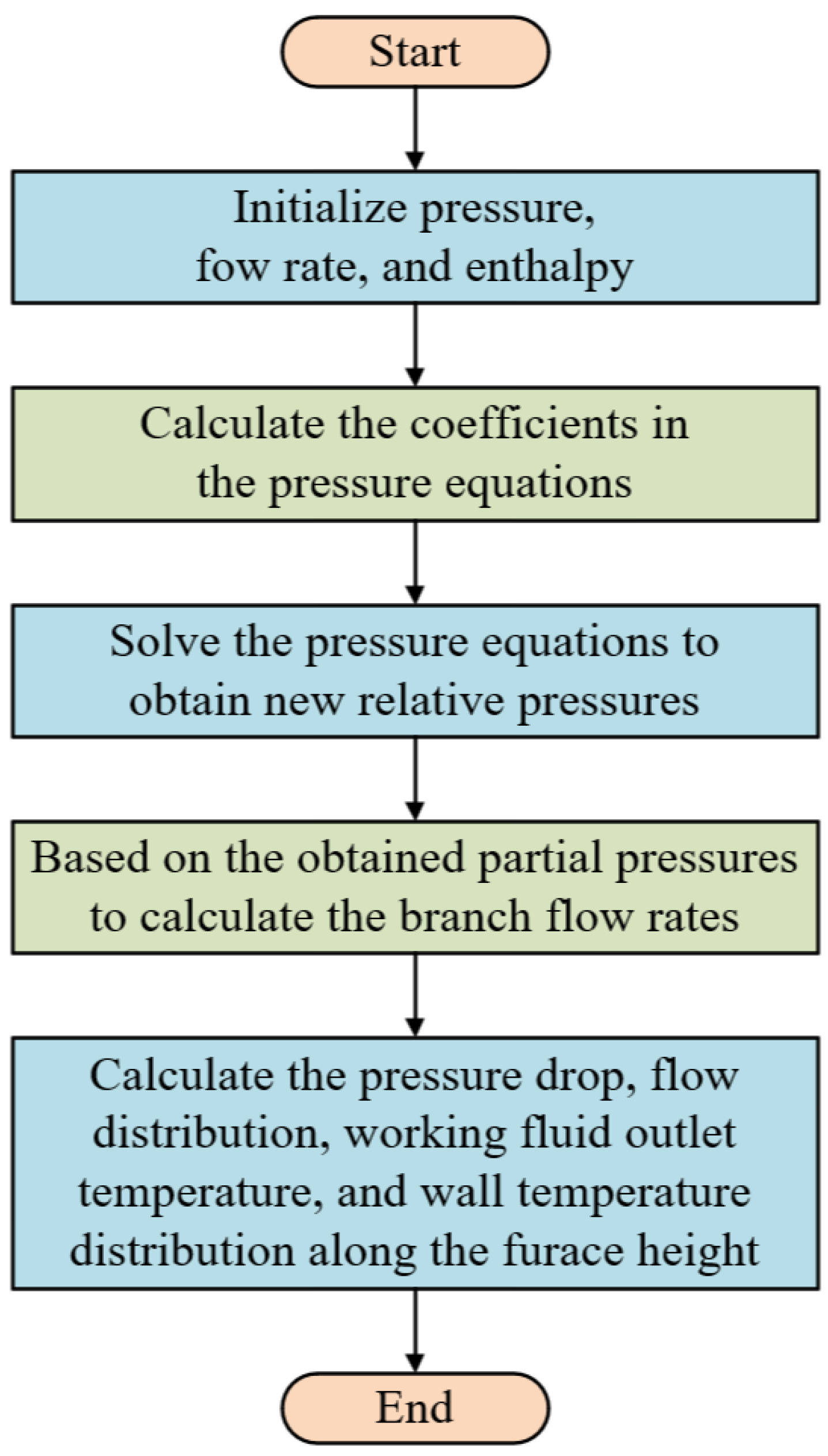

Fig. 1 outlines the calculation process used to determine the boiler's hydrodynamic characteristics in this study. The water-cooled wall flow network system can be viewed as consisting of flow paths, pressure nodes, and interconnecting pipelines. Adhering to the tenets of conservation of mass, momentum, and energy, a suite of pressure equations is formulated for each constituent element. [

16,

32,

33,

34]. By formulating and solving the nonlinear pressure loss balance equations, the branch flow rates are calculated utilizing the obtained partial pressures. The iterative calculation continues until the solution meets the predetermined accuracy requirements, ultimately yielding the pressure loss, flow distribution, working fluid outlet temperature, and wall temperature distribution along the furnace height.

2.2. Analysis of Pressure Equation

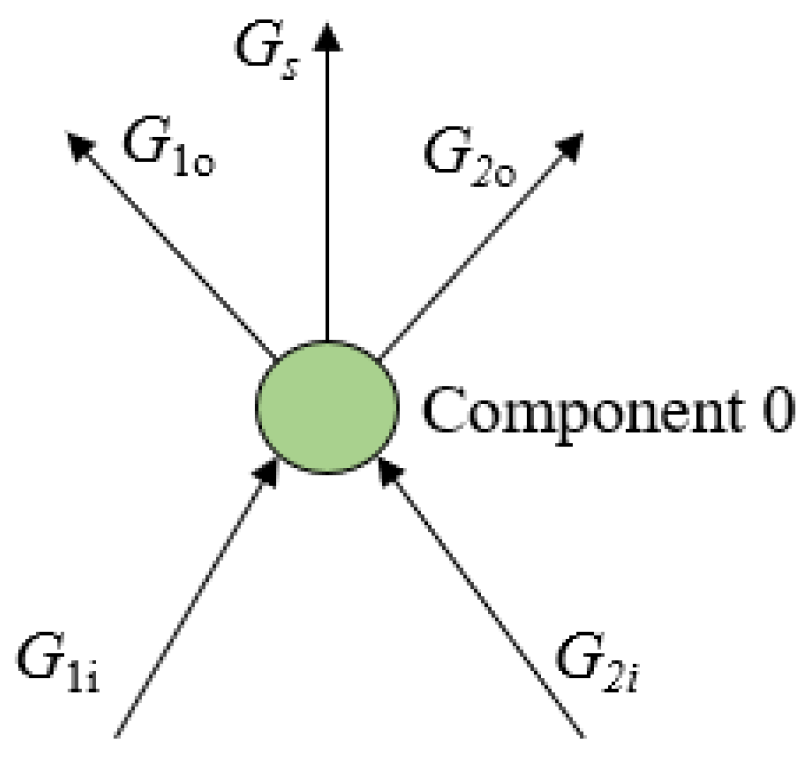

In order to uphold the principle of mass conservation, it is imperative that the mass flow rate influx into each component is equivalent to the mass flow rate efflux from that component. The inflow and outflow situation of the target component is displayed in

Fig. 2, where

and

(kg s

-1) represent the mass flow rates of the two branches flowing into component 0,

and

(kg s

-1) represent the mass flow rates of the two branches flowing out of component 0,

(kg s

-1) denotes the water flow source term in the specified component 0.

Assuming that a target component possesses

m entrances and

n exits, the mass conservation equation can be formulated as

where

(kg s

-1) represents the mass flow rate of the

i-th stream entering the target component, while

(kg s

-1) represents the mass flow rate of the

j-th stream leaving the target component.

The equation for determining the pressure loss during fluid flow through a tube is given by

where

(kg

2 s

-2) denotes the pressure losses in the tube due to local effects, friction, and acceleration. The gravity pressure loss is separately mentioned here because the first three types of pressure losses are all proportional to

(kg

2 s

-2), while the gravity pressure loss can be considered as a constant for mass flow rate

(kg s

-1).

is the coefficient of

in resistance calculation, which is similar to resistance in an electrical circuit.

Define

(kg s

-1) as the value superior to

(kg s

-1), where

represents the flow rate to be solved at the current level, pressure loss-flow relationship equation can be obtained using

The substitution of Equation (3) into the mass flow balance equation (1), considering the upward flow of the working fluid, yields the following result.

Taking into account the pressure loss across the target element, with the inlet pressure serving as a reference point, the following expression is obtained.

where

denotes the pressure loss due to the fluid flow between the intake of Component I and the designated target component (Pa),

indicates the pressure at the inlet of component I (Pa),

refers to the pressure loss generated internally within component I (Pa),

represents the pressure at the intake of the target component (Pa). The nomenclature for the determinants involved in the computation of pressure loss at the outlet of the component is analogous to that of the inlet.

Combining Equations (4), (5), and (6), the pressure equation can be obtained as

where the symbol before

(kg s

-1) is '-' indicating that this flow is exiting the component. If

represents the flow entering the component, the symbol before

should be '+'.

2.3. Heat Transfer Calculation Model

Moreover, the heat transfer coefficient is of paramount importance for the efficacy of water-cooled walls. Corroborated by empirical research into the thermal exchange properties of helical and vertical conduits, precise correlations pertaining to the heat transfer coefficient have been meticulously formulated.

For vertical tubes, the convective heat transfer coefficient of the fluid contained within the lumen is determined in accordance with the subsequent formula [

35].

In the lower-enthalpy zone

In the higher-enthalpy zone

where

is Reynolds number which calculated based on the temperature of the inner tube wall,

is enthalpy of the fluid at the tube wall surface (J kg

–1),

is enthalpy of bulk fluid (J kg

–1),

is metal temperature corresponds to the outer tube wall (°C),

is fluid temperature (°C),

is dynamic viscosity which determined by the temperature at the inner tube wall (N s m

–2),

is thermal conductivity of tube (W m

–1 K

–1),

is average density of fluid (kg m

–3),

is density while the inner tube wall temperature being a key parameter (kg m

–3).

For helical tubes, the heat transfer coefficient pertaining to the fluid contained within the lumen is determined by means of the subsequent formula [

36]

where

is Reynolds number which calculated based on the temperature of the inner tube wall,

is average Prandtl number which calculated using the inner wall temperature as the reference temperature,

is average density of fluid (kg m

–3),

is density while the inner tube wall temperature being a key parameter (kg m

–3).

2.4. Wall Temperature Calculation Model

When the boiler functions at low load, the flame distribution is uneven, resulting in significant differences in flue gas temperature, velocity, and combustion products. Additionally, the differences in the structure of the heating surfaces and the degree of ash deposition lead to uneven heat intensity distribution within the furnace.

As per the requirements of Russian Standard 98 [

37] for thermal calculation, by introducing the concept of the heat split coefficient, the temperature of the tube wall subjected to non-uniform heating can be ascertained through derivation.

where

is the mean temperature between the inner and outer walls, i.e., the calculated wall temperature (°C),

is the average temperature of the medium in the evaluated section component (°C),

is the wall thickness of the tube (m),

is the ratio of the tube’s outer to inner diameter, given by structural dimensions,

,

is the heat split coefficient,

is the maximum unit heat absorption of the deviation tube at the calculated section (calculated at the outer wall surface) (kW m

-2),

is the thermal conductivity of the tube wall metal (W m

-1 K

-1),

is the rate of heat transfer from the wall surface to the heated medium (W m

-2 K

-1).

It is readily ascertainable from the formula for calculating wall temperatures that the thermal state of the heating surface is contingent upon an array of factors, including but not limited to the conditions of heat load, the temperature of the medium undergoing heating, the heat transfer properties between the medium and the wall, the thermal conductivity of the material, as well as the geometric configuration.

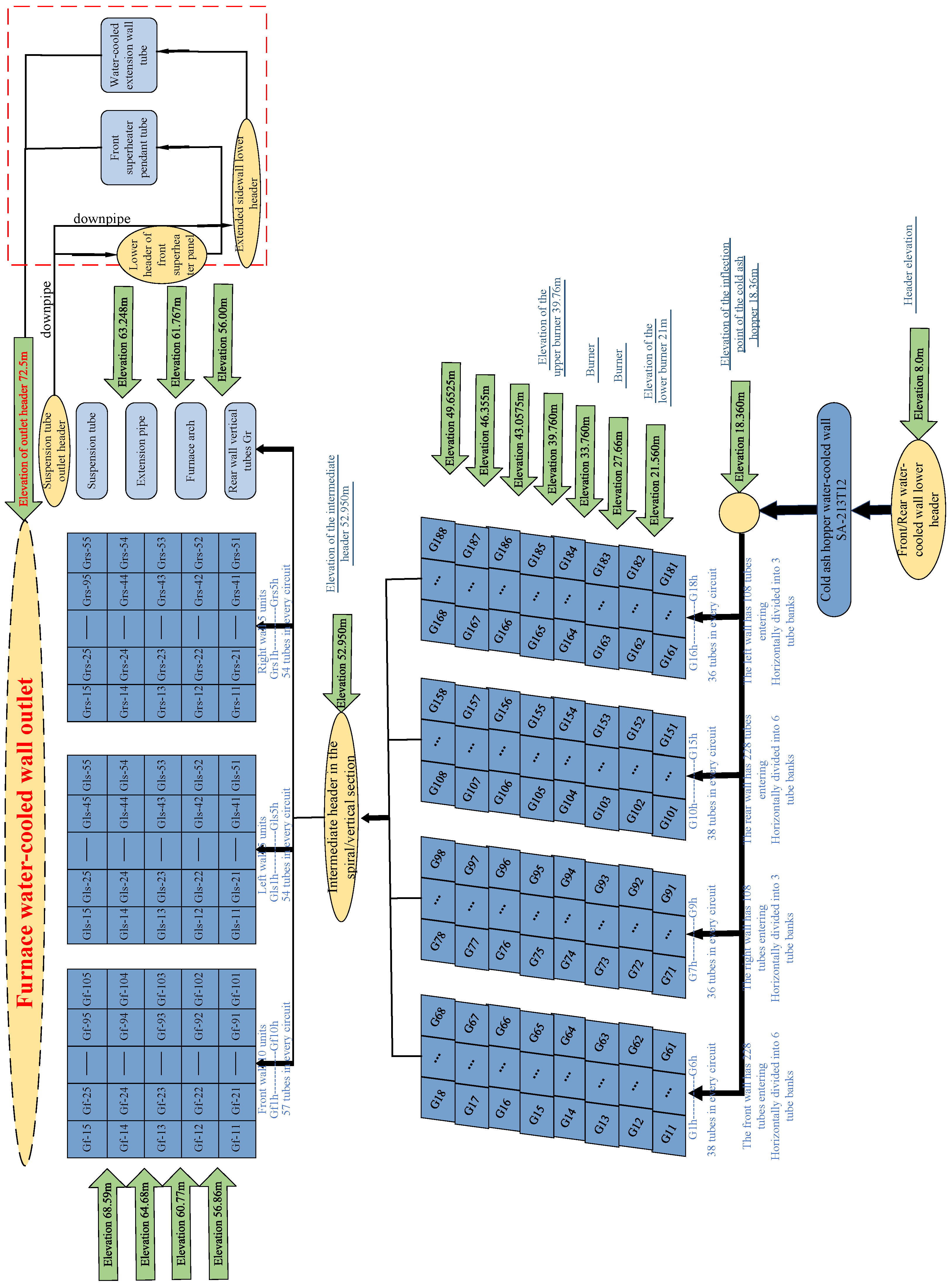

2.5. Calculation Loop Division

Based on the geometric characteristics of the furnace and the burner arrangement, the lower helical section of the water-cooled wall structure improves the uniformity of heat absorption. The distribution of heat flux density in the vertical direction necessitates meticulous examination. Horizontally, the heat flux is compartmentalized into spiral patterns at the inlet headers situated at the periphery of the four corners. This is consistent with the actual working fluid flow pattern. The vertical section is divided into five sections in the height direction, and is equally divided circumferentially according to the wall surface, with the calculation results corresponding to each divided pipe section. The distribution of the computational loop for the water-cooled wall is delineated in

Fig. 3.

3. Case Study

The boiler of a certain power plant is a 1000 MW ultra-supercritical, spiral furnace, single reheat, balanced ventilation, dry ash extraction, all-steel framed, outdoor-arranged π-type opposed firing boiler. The furnace depth of the boiler is 15,728.7 mm, the width is 33,128.7 mm, and the total height is 64,500 mm, spanning from the central axis of the lower header of the anterior water-cooled wall to the central axis of the furnace ceiling tube. The primary design specifications of the boiler are delineated in

Table 1.

The operational and combustion parameters of the boiler are inherently intricate, encompassing a complex array of factors such as fluid dynamics, heat transfer mechanisms, chemical reactions, and the interplay amongst these variables. The models employed in this study are reported in

Table 2. These models have been tested by many scholars and have been proven to be applicable to the combustion simulation of coal-fired boilers.

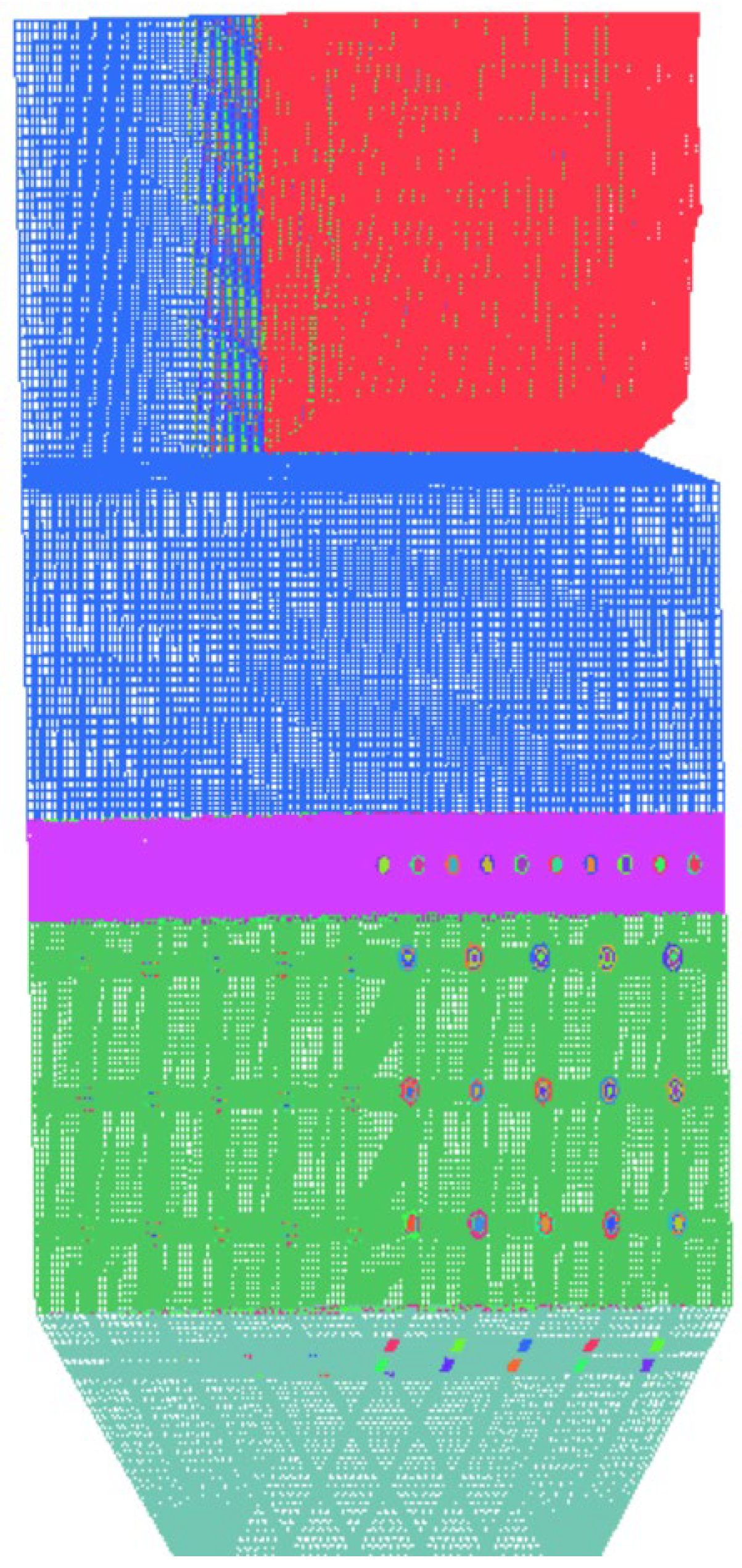

In practical engineering, unstructured grids are more adaptable to complex models and yield better prediction results. Therefore, FLUENT MESHING is applied for grid generation. To improve the connectivity within the boiler, the entire boiler is selected as a single unit for grid generation. The burner area, furnace area, heat exchanger area, and ash hopper area have complex structures and high turbulence intensity, so unstructured tetrahedral grids are employed to adapt to their complex physicochemical processes. For the burner area, considering the presence of many small-scale structures, the grid size is reduced to achieve grid refinement and minimize computational errors. The grid improvement function in FLUENT MESHING is utilized to enhance the initially generated grids, thereby improving grid quality and computational accuracy. The grid model is presented in

Fig. 4.

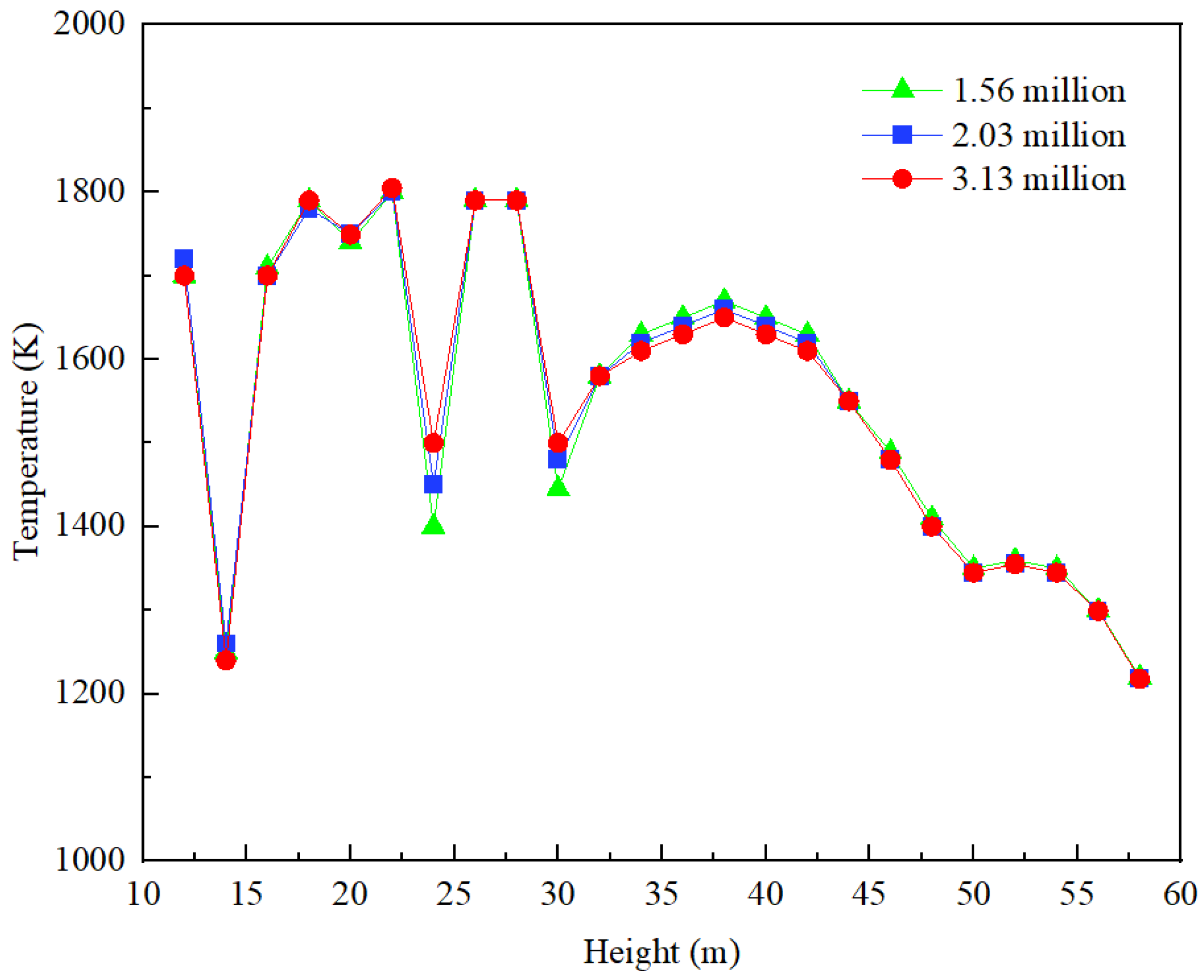

To balance computational speed and accuracy, this study sets up three grid systems with different grid counts, namely 1.56, 2.03, and 3.13 million. The increase in grid count is achieved by refining the grids in areas such as the burner based on the previous grid system.

In the course of executing grid independence assessments, the mean cross-sectional temperature gradient across the furnace's vertical axis is adopted as a critical metric.

Fig. 5 illustrates the comparative distribution of this average cross-sectional temperature profile along the furnace height for three distinct grid configurations, all under uniform operational parameters. The swirling air from the secondary air nozzle within the burner yields a diminished temperature gradient at the core of the burner layer. It is readily observable that the temperature distribution across the vertical axis of the furnace is generally consistent across all three grid systems, with the temperature profiles of the 2.03 and 3.13 million models showing greater similarity. The 2.03 million grid system can ensure good computational accuracy while reducing computational costs. All numerical simulation studies in this study are conducted on this grid system.

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Model Verification

To validate the reliability of the numerical simulation outcomes, the present investigation conducts a comparative analysis between the empirical measurements or thermodynamic computations of parameters at 100% BMCR conditions and the results derived from numerical simulations, as delineated in

Table 4. The table illustrates that the relative discrepancy between the numerical simulation outcomes and the empirical or thermodynamic computational values for the boiler remains within a 3% threshold. Considering the actual industrial production scale, the selected numerical model can be considered reliable.

4.2. 30% BMCR Load Hydrodynamic Characteristics

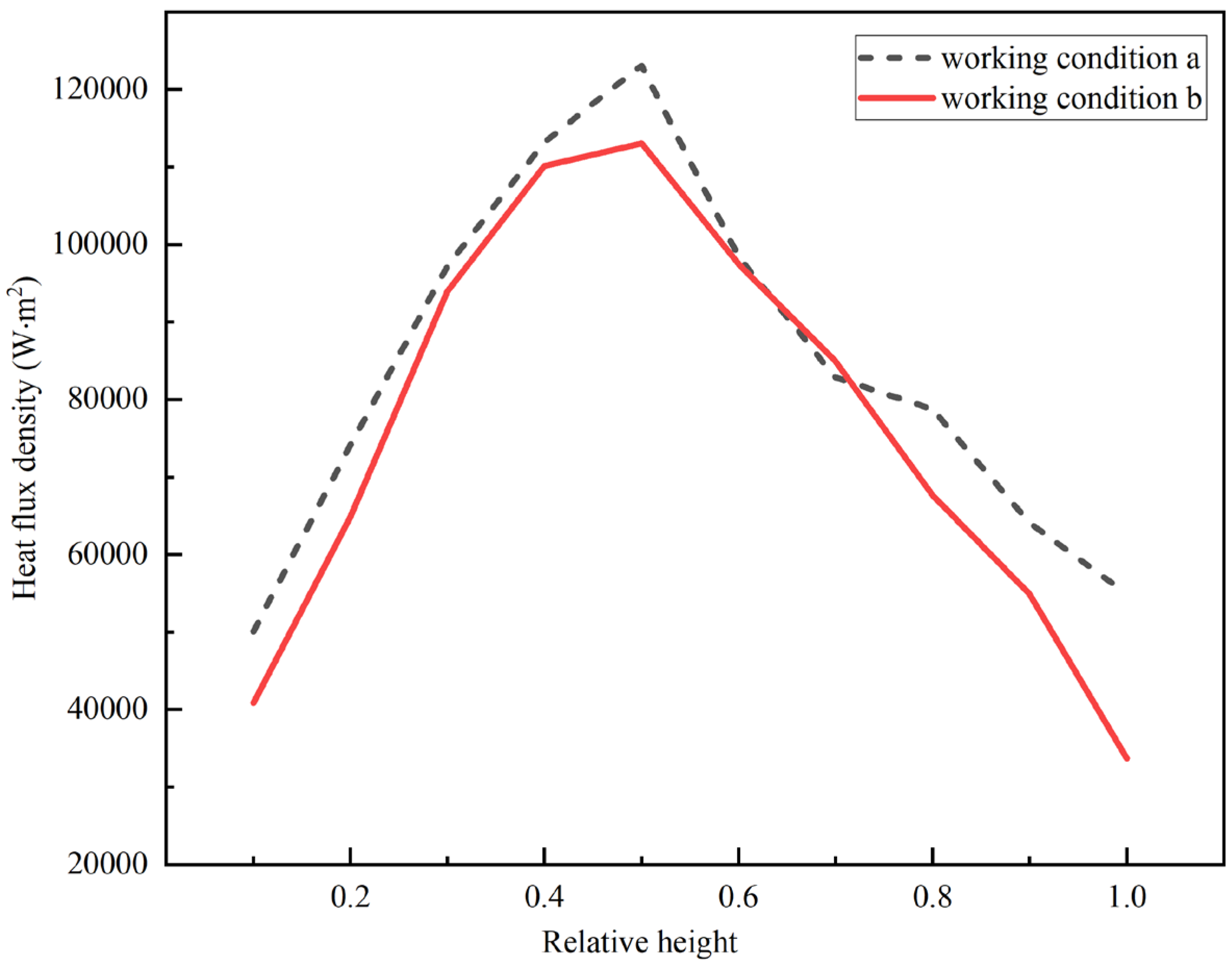

The distribution of the average heat flux density along the furnace height direction of the boiler's four walls under the 30% BMCR load obtained from the numerical simulation is illustrated in

Fig. 6, including two working conditions. It is evident that the highest heat flux density for both scenarios is concentrated in the central region of the furnace. Specifically, under condition b, the thermal load in the central region of the furnace varies more smoothly along the furnace height. This is attributed to the enhanced airflow filling and a more consistent velocity distribution within the furnace, thereby yielding an expanded high-temperature region at the furnace's core.

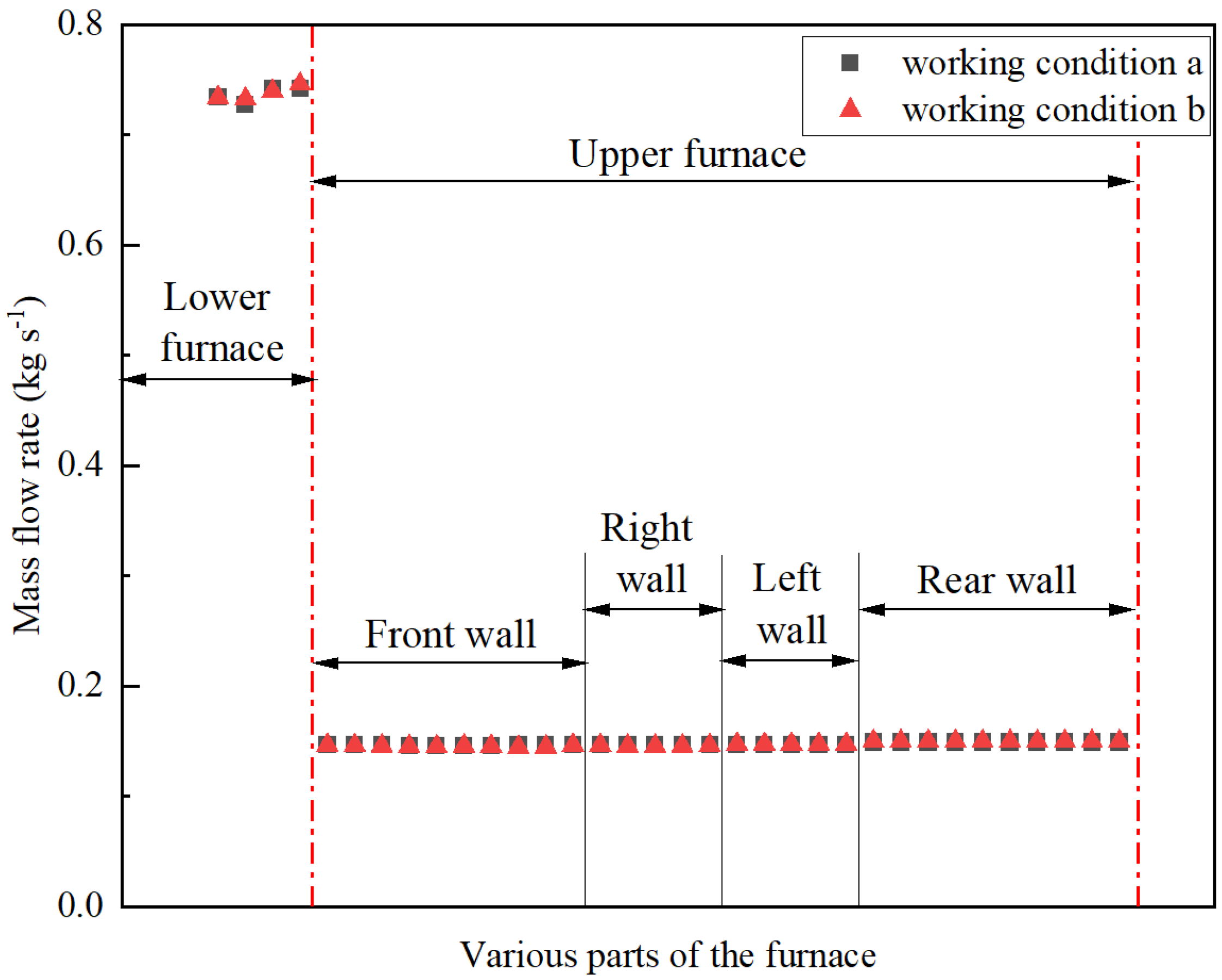

Fig. 7 clarifies the mass flow distribution circuit under the 30% BMCR load. The maximum mass flow rates of helical tube section and the vertical tube section are 0.746 and 0.147 kg s

-1, respectively. The imbalance in water-cooled wall loop flow primarily stems from several key factors. Firstly, heat absorption deviation is a significant contributor, resulting in uneven heat absorption across water-cooled wall tubes at different locations during the heat exchange process. Secondly, the arrangement of introduced tubes also impacts flow distribution, as different arrangement strategies lead to variations in fluid flow within the pipelines [

38]. Additionally, differences in the lengths of water-cooled wall tubes themselves are also a significant factor contributing to flow imbalance.

For helical tube loops, due to their design characteristics, the vertical height difference between each tube is essentially the same, indicating a relatively minor influence of gravity on fluid pressure loss. Simultaneously, these tubes are uniformly arranged around the furnace in a helical ascent manner, ensuring uniform heating surface. However, in this structure, even with uniform heating, significant flow resistance is induced due to factors such as the positions of burner nozzles and flue gas outlet nozzles, leading to a reduction in mass flow of the working fluid.

For the vertical tube sections, the distribution of flow in each tube loop is not solely determined by tube length, in fact, the total heat absorption within the tube is also a crucial factor. By observing

Fig. 7, we can observe that the mass flow rates at the front, right, and left walls are relatively close, indicating a relatively balanced flow distribution. Nonetheless, the mass flow rate at the rear wall is comparatively diminished, primarily due to the relatively complex design of the rear wall and significant influence from the flame bending angle. Due to the presence of the flame bending angle, the heat absorption at the rear wall is lower, which in turn results in a drop in gas content within the tube, thereby an increase in the working fluid's density. As a result of this density increase, the hydrostatic head also increases, ultimately leading to a reduction in flow within the loop [

39].

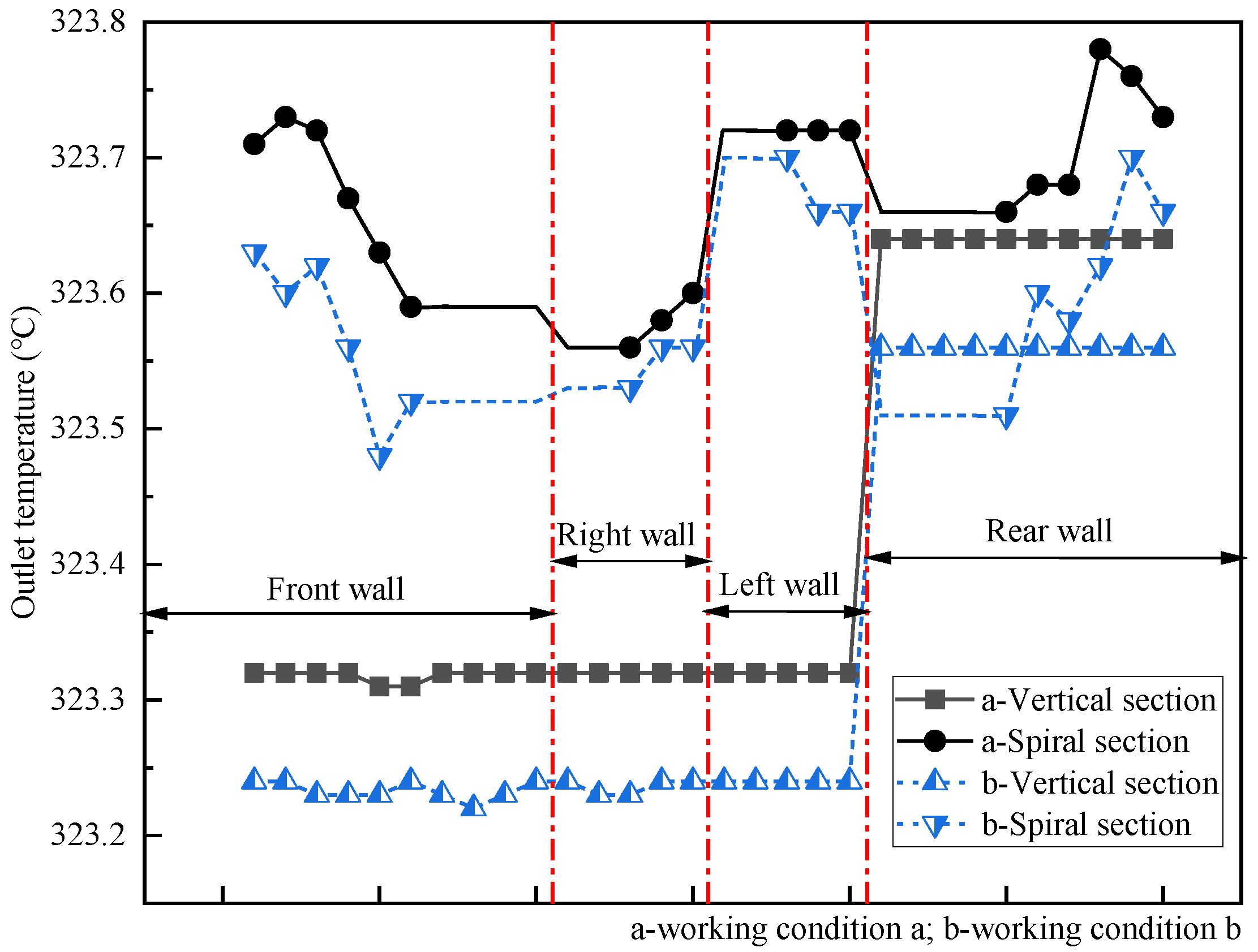

Fig. 8 illuminates the outlet temperature of the working fluid in the helical and vertical sections under the 30% BMCR load. At this point, the dryness of the working fluid at the effluent of the water-cooled wall boundary remains below 1, indicating that it is not superheated steam. From

Fig. 8, it can be observed that the helical section manifests the minimum outlet steam temperature at 323.5 °C, while the maximum recorded temperature at the outlet is 323.8 °C. The temperature deviation is 0.3 °C, which is consistent with the characteristic of small thermal deviation in helical tubes [

22]. The outlet steam temperature deviation in the vertical section is relatively large. The maximum outlet steam temperature is invariably recorded at the rear wall, whereas the front wall consistently manifests the minimum outlet steam temperature. Moreover, the distribution of outlet steam temperatures on the lateral walls, both to the left and right, exhibits a comparable pattern, whereas the rear wall typically exhibits outlet steam temperatures that surpass those on the front wall. This discrepancy is attributed to variations in flow rates resulting from differing flow cross-sections between the front and rear walls.

Table 5 delineates the computed pressure loss metrics within the water-cooled wall system under 30% BMCR operating conditions. The cumulative pressure loss across the water-cooled wall spans from the inlet header to the steam-water separator. The pressure loss in the helical coil covers the section from the inlet header to the intermediate header, while the pressure loss in the vertical tube panel occurs between the intermediate header and the furnace top outlet header. The computational outcomes reveal that the deployment of helical tube coils within the water-cooled wall of the lower furnace, coupled with the increased length of the helical tubes and the augmented flow rate of the operating fluid, predominantly contributes to the concentration of system pressure loss within the helical tube coil segment [

40]. The diminished flow velocity of the working fluid within the vertical conduits, coupled with their relatively reduced length, results in a significantly smaller proportion of pressure loss attributed to these conduits within the context of the overall pressure loss in the water-cooled wall system.

4.3. Wall Temperature Characteristics

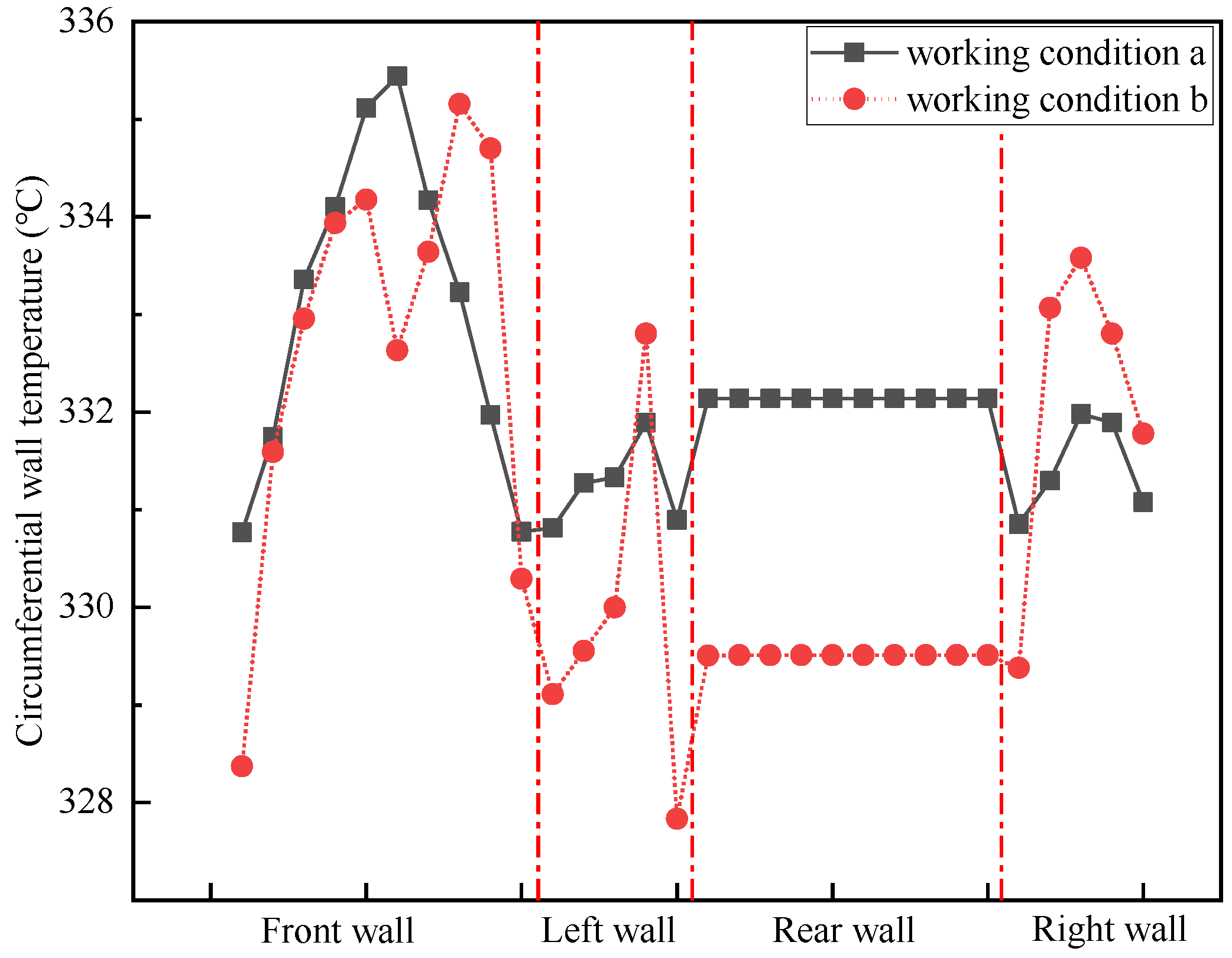

Fig. 9 demonstrates the circumferential wall temperature distribution along the vertical segment of the water-cooled wall. The high-temperature section appears near the centerline of each wall, with the highest wall temperature occurring on the front side wall. The wall temperature distribution across the boiler's front wall, left wall, and right wall demonstrates a relative homogeneity, whereas the temperature of the rear wall exhibits less fluctuation compared to the other walls. This is due to the smaller heating region of the rear wall's water-cooled wall and the presence of suspension tubes, resulting in more uniform heat distribution.

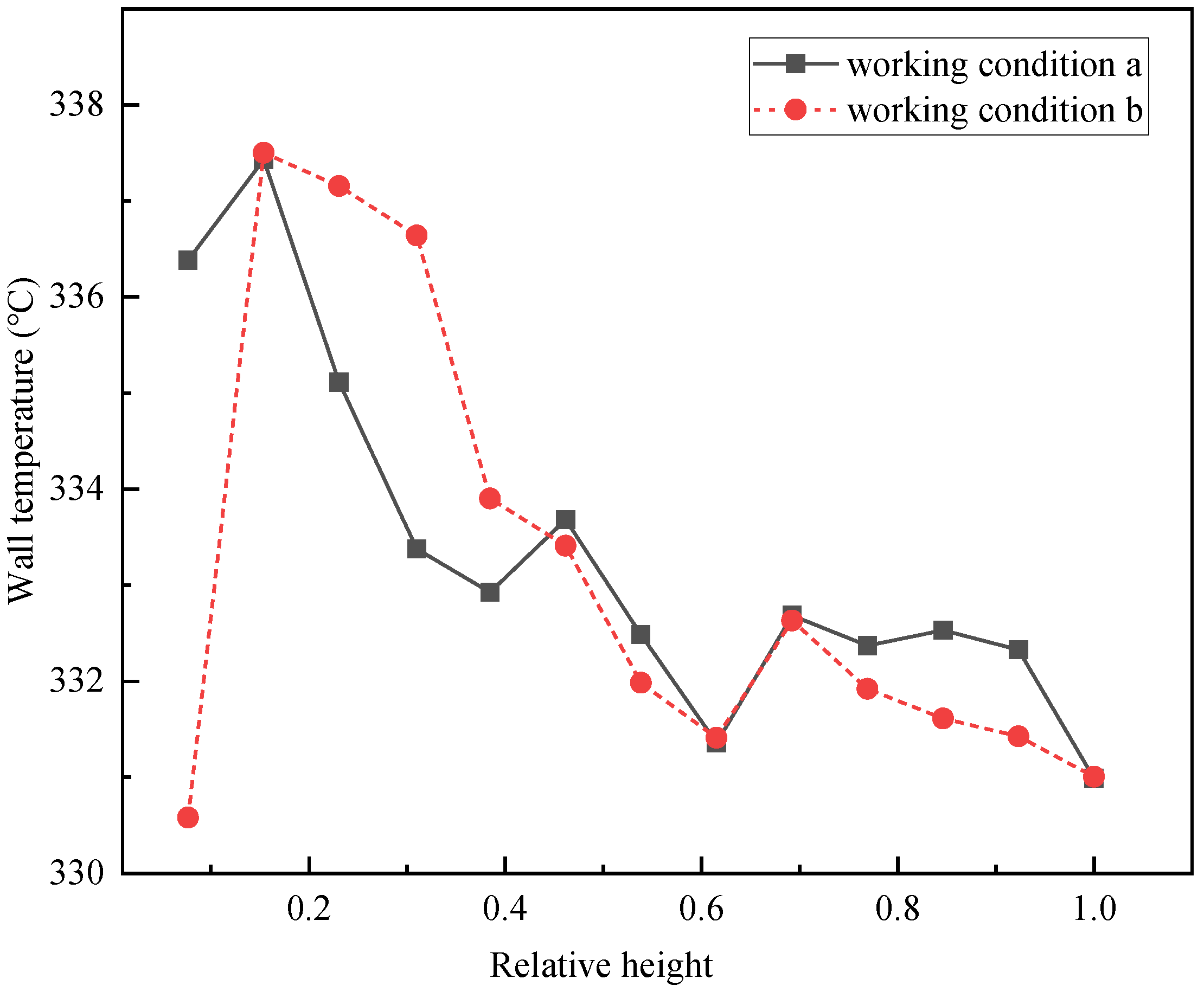

Fig. 10 illustrates the distribution of wall temperatures along the vertical axis of the furnace. Due to the increase of heat flux density, the wall temperature rises rapidly. Then, with the decrease of heat flux along the height of the furnace, the wall temperature shows a decreasing trend as a whole. Additionally, as the working medium traverses into the biphasic zone, the fluid's heat transfer coefficient increases substantially, leading to an overall reduction in wall temperature, with the maximum reaching 337.5°C.

5. Conclusions

In this study, an analysis is conducted on the hydrodynamic performance and wall temperature of the water-cooled wall within a 1000 MW supercritical boiler under low-load conditions. Moreover, computations are performed to ascertain the mass flow distribution, the temperature of the effluent working fluid at the outlet, the pressure drop, and the wall temperature at a load corresponding to 30% BMCR. The conclusions can be described as follows:

To ascertain the credibility of the numerical simulation outcomes, a comparative analysis was conducted between the empirical measurements and the thermodynamic computations for parameters, including the flue gas temperature at the outlet of the platen superheater, under conditions corresponding to 100% BMCR. The comparison results demonstrate that the established numerical model is correct and reliable.

At 30% BMCR load, the flow distribution across the quartet of walls within the water-cooled wall is basically balanced. The flow distribution characteristics of the helical section and the vertical section are similar, with the maximum mass flow rates of 0.746 and 0.147 kg s-1 respectively, and the maximum mass flow deviations of 1.95% and 3.47% respectively, indicating small flow deviations and reasonable distribution. The flow deviation in the helical section is mainly influenced by uneven tube length, while the flow deviation in the vertical section is primarily affected by differences in heat load.

At 30% BMCR load, the lowest outlet steam temperature of the uniformly heated helical section is 323.5 °C, and the highest outlet steam temperature is 323.8 °C, with a temperature deviation of 0.3 °C, which is consistent with the characteristic of low thermal deviation in helical tubes. The heat absorption deviation causes a larger temperature deviation at the outlet of the vertical section. However, it remains within the safe range.

At 30% BMCR load, the comprehensive pressure loss across the system amounts to 0.4 MPa, while the peak wall temperature recorded on the water-cooled wall reaches 337.5 °C. The tube wall temperature remains within the material's allowable safety limits, with no degradation in heat transfer observed, indicating that the water-cooled wall design is both achievable and effective.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Guangdong Administration for Market Regulation Science and Technology Project [grant numbers 2014CT12].

Nomenclature

|

mass flow rate (kg s-1) |

|

mass flow rate of the i-th stream entering the target component (kg s-1) |

|

mass flow rate of the j-th stream leaving the target component (kg s-1) |

|

water flow source term in the specified component (kg s-1) |

|

mass flow rate of the previous level for the same branch flow (kg s-1) |

|

mass flow rate of the previous level of the i-th inlet branch of the component (kg s-1) |

|

mass flow rate of the previous level of the j-th outlet branch of the component (kg s-1) |

|

mass flow rate of the previous level of the I-th branch of the component (kg s-1) |

|

mass flow rate of the previous level of the I-th outlet branch of the component (kg s-1) |

|

mass flow rate of the previous level of the I-th inlet branch of the component (kg s-1) |

|

gravitational acceleration (m s-²) |

|

length of the tube segment (m) |

|

enthalpy of bulk fluid (J kg-1) |

|

enthalpy of the fluid at the tube wall surface (J kg-1) |

|

number of branches where the working fluid enters component 0 |

|

number of branches where the working fluid flows out of component 0 |

|

Nusselt number |

|

pressure at the inlet of the target component (Pa) |

|

pressure loss is due to the working fluid flow between the component inlet and the target component inlet (Pa) |

|

pressure loss is due to the working fluid flow between the component outlet and the target component outlet (Pa) |

|

pressure at the inlet of component (Pa) |

|

pressure at the outlet of component (Pa) |

|

pressure loss generated internally within component (Pa) |

|

pressure loss of the target component (Pa) |

|

pressure of the I-th branch of the component (Pa) |

|

pressure loss of the component 0 (Pa) |

|

pressure loss of the I-th branch of the component (Pa) |

|

average Prandtl number is calculated using the inner wall temperature as the reference temperature |

|

pressure of the I-th branch of the component 0 (Pa) |

|

ratio of the tube’s outer to inner diameter (kW m-2) |

|

resistance coefficient |

|

resistance coefficient at the I-th branch of component |

|

resistance coefficient of the I-th outlet branch of the component |

|

resistance coefficient of the I-th inlet branch of the component |

|

resistance coefficient at the inlet of component |

|

resistance coefficient at the outlet of component |

|

Reynolds number is calculated based on the temperature of the inner tube wall |

|

mean temperature between the inner and outer walls (°C) |

|

fluid temperature (°C) |

|

metal temperature corresponds to the outer tube wall (°C) |

|

average temperature of the medium in the evaluated section component (°C) |

| Greek symbols |

|

|

rate of heat transfer from the wall surface to the heated medium (W m-2 K-1) |

|

ratio of the tube’s outer to inner diameter |

|

wall thickness of the tube (m) |

|

heat split coefficient |

|

thermal conductivity of the tube wall metal (W m-1 K-1) |

|

average density of fluid (kg m-3) |

|

density while the inner tube wall temperature being a key parameter (kg m-3) |

|

thermal conductivity of tube (W m-1 K-1) |

|

dynamic viscosity is determined by the temperature at the inner tube wall (N s m-2) |

| Abbreviations |

|

| BMCR |

boiler maximum continuous rating |

| OFA |

over fire air |

References

- Luo, G.; Zhang, X.; Liu, S.; Dan, E.; Guo, Y., Demand for flexibility improvement of thermal power units and accommodation of wind power under the situation of high-proportion renewable integration—taking North Hebei as an example. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 2019, 26, 7033-7047. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhao, M.; Chang, J.; Wang, X.; Tian, Y., Study on the combined operation of a hydro-thermal-wind hybrid power system based on hydro-wind power compensating principles. Energy Conversion and Management 2019, 194, 94-111. [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Hu, B.; Tai, N.; Zhao, L.; Vafai, K., Peak shaving auxiliary service analysis for the photovoltaic and concentrating solar power hybrid system under the planning-dispatch optimization framework. Energy Conversion and Management 2023, 295, 117609. [CrossRef]

- Spiru, P., Assessment of renewable energy generated by a hybrid system based on wind, hydro, solar, and biomass sources for decarbonizing the energy sector and achieving a sustainable energy transition. Energy Reports 2023, 9, 167-174. [CrossRef]

- Xu, G.Q.; FENG, S.W., Spatial-temporal Evolution Characteristics of Carbon Emissions from Energy Consumption in China’s Thermal Power Industry. Ecological Economy. 2024; 40, 30-8. (in Chinese).

- Xi Jinping delivered an important speech at the general debate of the 75th session of the United Nations General Assembly. 2020. (in Chinese).

- Jin, W.; Si, F.; Cao, Y.; Yu, C.; Wang, J., Numerical research on ammonia-coal co-firing in a 1050 MW coal-fired utility boiler under ultra-low load: Effects of ammonia ratio and air staging condition. Applied Thermal Engineering 2023, 233, 121100. [CrossRef]

- Jin, W.; Si, F.; Kheirkhah, S.; Yu, C.; Li, H.; Wang, Y. o., Numerical study on the effects of primary air ratio on ultra-low-load combustion characteristics of a 1050 MW coal-fired boiler considering high-temperature corrosion. Applied Thermal Engineering 2023, 221, 119811. [CrossRef]

- Ma, D.; Zhang, S.; He, X.; Ding, X.; Li, W.; Liu, P., Combustion stability and NOx emission characteristics of three combustion modes of pulverized coal boilers under low or ultra-low loads. Applied Energy 2024, 353, 121998. [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Jin, H.; Yang, Z.; Deng, S.; Wu, X.; An, J.; Sheng, R.; Ti, S., CFD modeling of flow, combustion and NOx emission in a wall-fired boiler at different low-load operating conditions. Applied Thermal Engineering 2024, 236, 121824.

- Wang, W.; Gong, J., New relaxation function and age-adjusted effective modulus expressions for creep analysis of concrete structures. Engineering Structures 2019, 188, 1-10. [CrossRef]

- Qiu, S.; Song, R.; Wang, Z.; Du, Z.; Zhan, Y., Research and application of AGC whole process automatic control for thermal power units under low load deep peak shaving conditions. 2022 IEEE 10th Joint International Information Technology and Artificial Intelligence Conference (ITAIC) 2022, 484-488.

- Jian, L.; Jianguo, X.; Jialin, T.; Hongkun, L., Study on Ultra-low Load Stable Combustion Technology of Boiler in Deep Peak Shaving. Zhejiang Electric Power, 2018, 37, 62-66.

- Wang, X.; Yang C.; Zhang Z., Online Tracking Simulation System of a 660 MW Ultra-Supercritical Circulating Fluidized Bed Boiler. Journal of Thermal Science 2023, 32, 1819-1831. [CrossRef]

- Lichota, J., Modeling of supercritical boiler by neural network. Rynek Energii 2023, 167, 64-69.

- Zhang, W.; Wang, H.; Yan, K.; Zhou, T.; Wang, C. a.; Chen, K.; Che, D., Mathematical modeling and thermal-hydrodynamic analysis of vertical water wall in a SCFB boiler with annular furnace. Applied Thermal Engineering 2016, 102, 742-748. [CrossRef]

- Tucakovic, D. R.; Stevanovic, V. D.; Zivanovic, T.; Jovovic, A.; Ivanovic, V. B., Thermal-hydraulic analysis of a steam boiler with rifled evaporating tubes. Applied Thermal Engineering 2007, 27, 509-519. [CrossRef]

- Dev Choudhury, S.; Khan, W. N.; Lyu, Z.; Li, L., Failure analysis of blowholes in welded boiler water walls. Engineering Failure Analysis 2023, 153, 107560. [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Wang, Y.; Zou, L.; Bai, Y.; Shen, T.; Wei, Y.; Li, F.; Zhao, Q., Numerical investigation of stable combustion at ultra-low load for a 350 MW wall tangentially fired pulverized-coal boiler: Effect of burner adjustments and methane co-firing. Applied Thermal Engineering 2024, 246, 122980.

- Yang, C.; Zhang, T.; Sun, L.; Huang, S.; Zhang, Z., Piecewise affine model identification and predictive control for ultra-supercritical circulating fluidized bed boiler unit. Computers & Chemical Engineering 2023, 174, 108257. [CrossRef]

- Xin, N.; Ke, Z.; Honggang, L.; ZHANG, G.; Huanhuan, L.; Nan, W. Hydrodynamic Analysis and Metal Temperature Calculation for the Water Wall of a 660MW Supercritical Boiler at Severe Peak Load Regulation. 2019 IEEE 2nd International Conference on Power and Energy Applications (ICPEA) 2019, 188-196.

- Wang, W.; Zhao, P.; Chen, G.; Bi, Q.; Gu, H., Hydrodynamic characteristics of vertical water-wall in ultra-supercritical pressure boiler. Huagong Xuebao/CIESC Journal 2013, 64, 3213-3219.

- Chen, Y.; Lu, X.; Zhang, W.; Wang, Q.; Chen, S.; Fan, X.; Li, J., An experimental study on the hydrodynamic performance of the water-wall system of a 600 MW supercritical CFB boiler. Applied Thermal Engineering 2018, 141, 280-287. [CrossRef]

- Chang, J.; Zhou, Z.; Ma, X.; Liu, J., Computational investigation of hydrodynamics, coal combustion and NOx emissions in a tangentially fired pulverized coal boiler at various loads. Particuology 2022, 65, 105-116. [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Xia, L.; Zhao, G.; Wei, G.; Wang, Y.; Yin, Y.; Guo, J.; Ren, X., Steam Temperature Characteristics in Boiler Water Wall Tubes Based on Furnace CFD and Hydrodynamic Coupling Model. Energies 2022, 15, 4745. [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zeng, L.; Zhang, N.; Chen, Z.; Li, Z.; Qin, Y., Effects of the air-staging degree on performances of a supercritical down-fired boiler at low loads: Air/particle flow, combustion, water wall temperature, energy conversion and NOx emissions. Fuel 2022, Vol.308, 121896. [CrossRef]

- Chang, J.; Wang, X.; Zhou, Z.; Chen, H.; Niu, Y., CFD modeling of hydrodynamics, combustion and NOx emission in a tangentially fired pulverized-coal boiler at low load operating conditions. Advanced Powder Technology 2021, 32, 290-303. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Wang, W.; Xu, W., A study of the hydrodynamic characteristics of a vertical water wall in a 2953t/h ultra-supercritical pressure boiler. International Journal of Heat and Mass Transfer 2015, 86, 404-414. [CrossRef]

- Wan, L.; Yang, D.; Zhou, X.; Dong, L.; Li, J., Thermal-hydraulic calculation and analysis on evaporator system of a 1000 MW ultra-supercritical pulverized combustion boiler with double reheat. Journal of thermal science 2021, 30, 807-816. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, K.; He, M.Q.; Niu, T.T., Study on hydrodynamic characteristics of supercritical 660 MW lignite boiler with deep peak load. Thermal Power Generation 2022, 51, 88-95. (in Chinese).

- Liu, H.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, W.; Wang, H.; Deng, L.; Che, D., Coupled modeling of combustion and hydrodynamics for a 1000 MW double-reheat tower-type boiler. Fuel 2019, 255, 115722. [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Zhang, W.; Wang, H.; Zhang, Y.; Deng, L.; Che, D., Coupled combustion and hydrodynamics simulation of a 1000MW double-reheat boiler with different FGR positions. Fuel 2020, 261. [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Che, D., Positive Flow Response Characteristic in Vertical Tube Furnace of Supercritical Once-Through Boiler. Journal of Thermal Science and Engineering Applications 2014, 6. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Yan, K.; Wang, H.; Che, D., Research on Thermal hydrodynamic Performance of Water Wall Pipes for Ultra-supercritical Double Reheat Once-through Boiler. Journal of Engineering for Thermal Energy and Power 2016, 31, 75-80.

- Wang, W.; Liang, Z.; Wan, L.; Liu, D.; Yang, D., Experimental investigation on heat transfer characteristics of smooth water wall tube of an ultra-supercritical CFB boiler. ASME International Mechanical Engineering Congress and Exposition 2018.

- Wang, S.; Yang, D.; Zhao, Y.; Qu, M., Heat transfer characteristics of spiral water wall tube in a 1000 MW ultra-supercritical boiler with wide operating load mode. Applied Thermal Engineering 2018, 130, 501-514. [CrossRef]

- A.M.Gurvich, N.V.Kuzneshov. Standard method for thermal calculation of boiler units 1963. (in Chinese).

- Ni, X.B.; Zhou, K.Y.; Xu, Q.L., Hydrodynamic Calculation and Safe Evaporation for the Water Wall in a Supercritical Boiler 30% BMCR. POWER EQUIPMENT 2021, 35, 149-156. (in Chinese).

- Ge, X.L.; Zhang, Z.X.; Fan, H.J., Study on the influence of thermal deviation and flow deviation on the water-cooled wall temperature of 1000 MW ultra-supercritical boiler. Proceedings of the CSEE 2018, 38, 2348-2357, 544. (in Chinese).

- Pang, L.P.; Yuan, H.; Qiu, W.S., Hydrodynamic characteristics during peaking operation in utility boiler. Chemical Industry and Engineering Progress 2023, 42, 1708-1718. (in Chinese).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).