Introduction

The mounting resistance in Escherichia coli, the commonest cause of community-acquired urinary tract infection (UTI) is concerning. It is being increasingly perceived that the drivers of antimicrobial resistance (AMR) may not only be antibiotic use and misuse but socioeconomic and environmental factors like ambient temperature, humidity, population density, gross domestic product, standard of living and water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH) facilities may also contribute (1–3).

A multicentric multidisciplinary research and programme initiative, Diagnostic and Antimicrobial StewardsHip (DASH) to protect antibiotics (http:dashuti.com) is currently promoting preparation of community based local antibiograms of urinary tract infections. Antimicrobial prescribing based on the local antibiograms will enable judicious antimicrobial use and promote antimicrobial stewardship in ambulatory patients. A comprehensive multicenter analysis of the antimicrobial susceptibility rates of E. coli in community acquired UTI across 38 centres spanning four continents located in the Indian subcontinent (IS), Middle East (ME), North and West Africa, Eurasia, Europe, and North America is presented here.

This broader scope enabled us to investigate not only regional variations in antimicrobial susceptibility patterns but also the potential influence of environmental factors such as temperature and humidity on these patterns. By exploring these geographic and climatic correlations, we aimed to deepen our understanding of the complex factors driving antimicrobial resistance and inform targeted strategies for improving treatment outcomes and combating resistance globally.

Methods

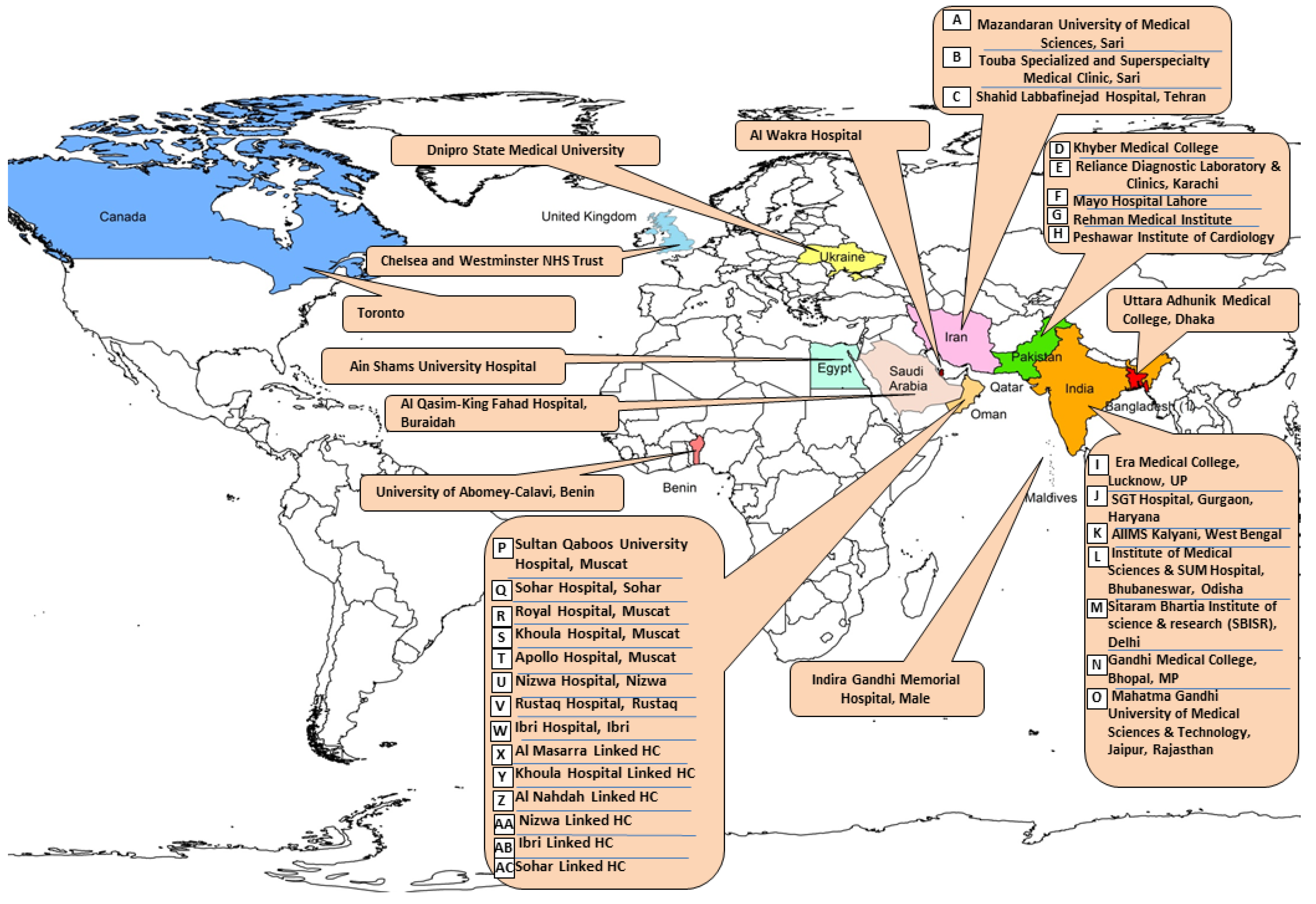

The susceptibility profile of E. coli isolated from adult cases of simple cystitis attending the outpatient departments or the Emergency Departments were analysed across 38 sites, (32 sites in the IS and the ME, one site each in Maldives, Egypt, Benin, Ukraine, UK and Canada) in 2023. The geographic spread and climate of these sites from east to west is as follows: Dhaka, Bangladesh (one site, tropical monsoon-type climate); India (7 centres): 3 in North (N.) India characterised by subtropical climate (Delhi, Gurugram, Lucknow), one in central (C.) India, (Bhopal, Madhya Pradesh), two in East (E.) India, (Kalyani, West Bengal and Bhubaneswar, Orissa) and one in, Jaipur, Rajasthan West (W) India (hot climate); Pakistan (5 centres, with temperate climate, three in Peshawar and one each in Lahore and Karachi); Iran (3 centres, two in Sari,(humid subtropical climate and one in Tehran, hot arid); Oman, 8 tertiary care centres, (4 in Muscat, one each in Suhar, Ibri and Rustaq) and 55 linked health centres. There was one centre each in Qatar, (Al Wakra), Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, (KSA), Buraydah; Egypt, Cairo. The climate is hot subtropical desert type in these countries. Centres lying further apart were: Benin, West Africa, (tropical), Male, Maldives (equatorial monsoon) in the Indian Ocean and three centers in the temperate region: Dnipro (Ukraine), London (United Kingdom), and Toronto (Canada). Five high income countries participated (Oman, Qatar, KSA, United Kingdom and Canada) while the others were low and medium income countries (LMICs).

The recruitment process was outlined in the previous paper (4). In short Fifty-five centers were approached, of which 38 (27 tertiary-care public and private hospitals) joined. Seventeen centers were academic while the remaining were non-academic. Processing of samples was done as mentioned in the previous study (4). Antimicrobial Susceptibility testing (AST) was performed according to CLSI guidelines M100-Ed33) 2023 (5). Twenty three sites largely used disc diffusion testing whilst 15 used automated systems, eleven used a mixture of both approaches. Quality control was practiced by all laboratories.

Efforts were made to include only clinical isolates from patients presenting with a symptomatic UTI (frequency, dysuria and urgency, with or without haematuria and abdominal pain) at out-patient or Emergency Department were included. However, one site (Buraydah, KSA) sent us combined data. Data from these patients were collated into site antibiograms if 30 or more non-duplicate isolates were tested at a site. Only data for routinely-tested antimicrobial agents were included. CLSI guideline M39A4E CLSI 2022 was used to prepare the antibiograms (6,7).

The Harmonic mean (HM) was calculated using the pooled averages. The mean proportion of E. coli susceptibility to each drug was calculated based on the GDP of the countries. The Kruskal-Wallis test was utilized to compare susceptibility means between the antimicrobials and the GDP. A two-way ANOVA was conducted to simultaneously analyze the impact of the antimicrobial and GDP on the proportion of susceptible E. coli while adjusting for other variables (low and high temperature, humidity [climate] and population density per sqkm). Regional subgroup analysis was performed by categorizing the countries into three regions. Furthermore, the Mann-Whitney test was used to compare susceptibilities between Pakistan and India. The data analysis was carried out using SPSS 29, and a significance level of p < 0.05 was established.

Results

The geographic location of the participating centers is provided in

Figure 1.

The southernmost, Maldives, lies on the Equator. Majority (29 centres) were situated between 200-300 latitude.The GDP per capita income ranged from

$1400 to

$82,000, (

Table 1), with the majority clustering around

$1000-3900 (LMICs), and

$20,000-

$29,000 (HICs). Population per square kilometer in the majority of our centers (15) ranged between 1000-9999/sq km. Five cities had a population density of less than 1000/ sq km. Apart from London, the capitals of the countries in our study (Delhi, Tehran, Cairo, Male, Dhaka) had a population density of more than 10,000/ sq km. The densest capital was Dhaka with 38,000/ sq km. The average humidity ranged from 79 in Male, Maldives to 75 (Dhaka, Bangladesh in the east, Abomey Calavi, Benin in the west, Dnipro, Ukraine in the north.) to 22.2 ( Buraydah, Saudi Arabia) and 58.9 ( Al Wakra, Qatar) in the Middle East.

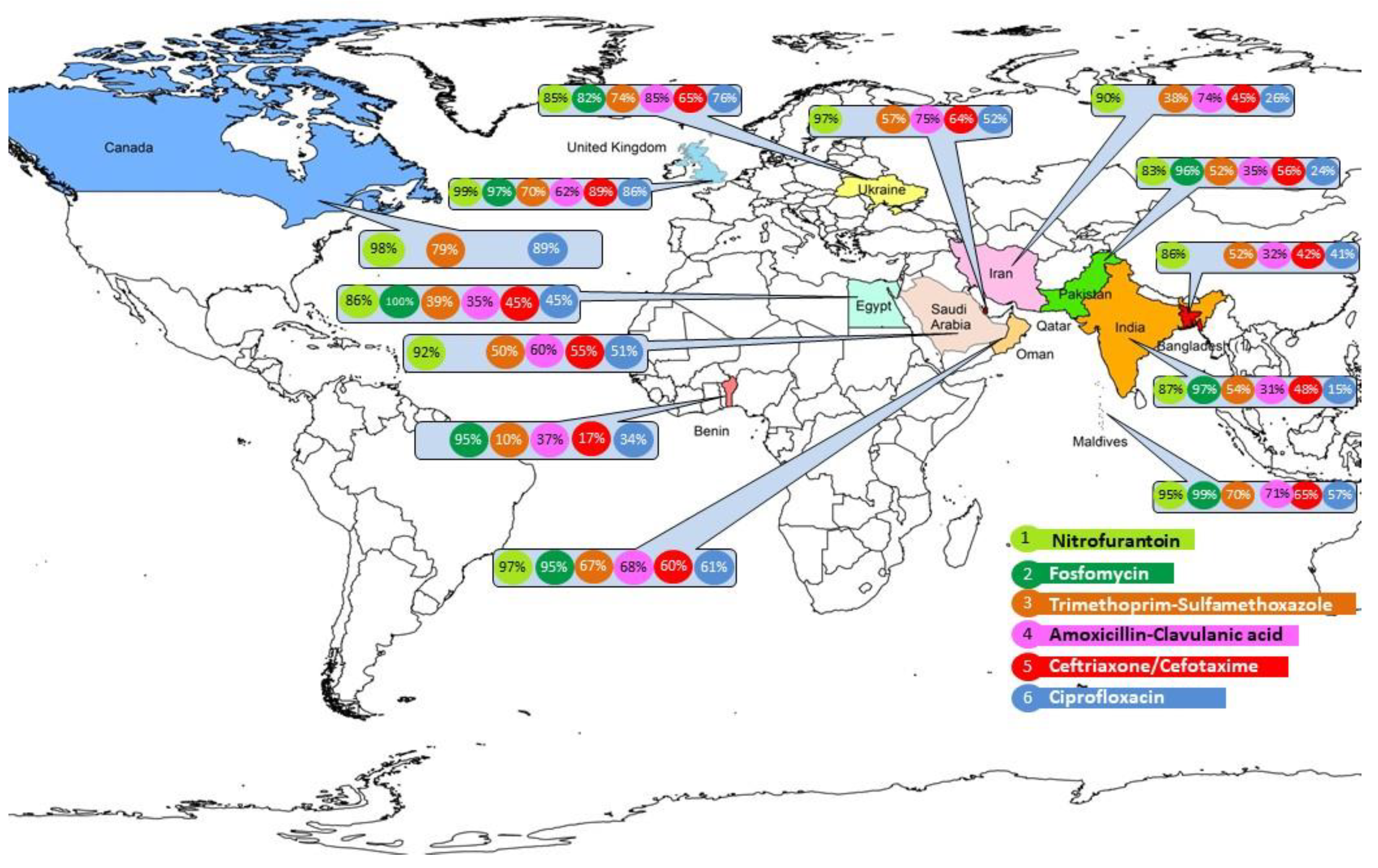

The susceptibility rates across all sites are shown in

Table 2. Regional rates by centers for major oral antibiotics are shown by site in

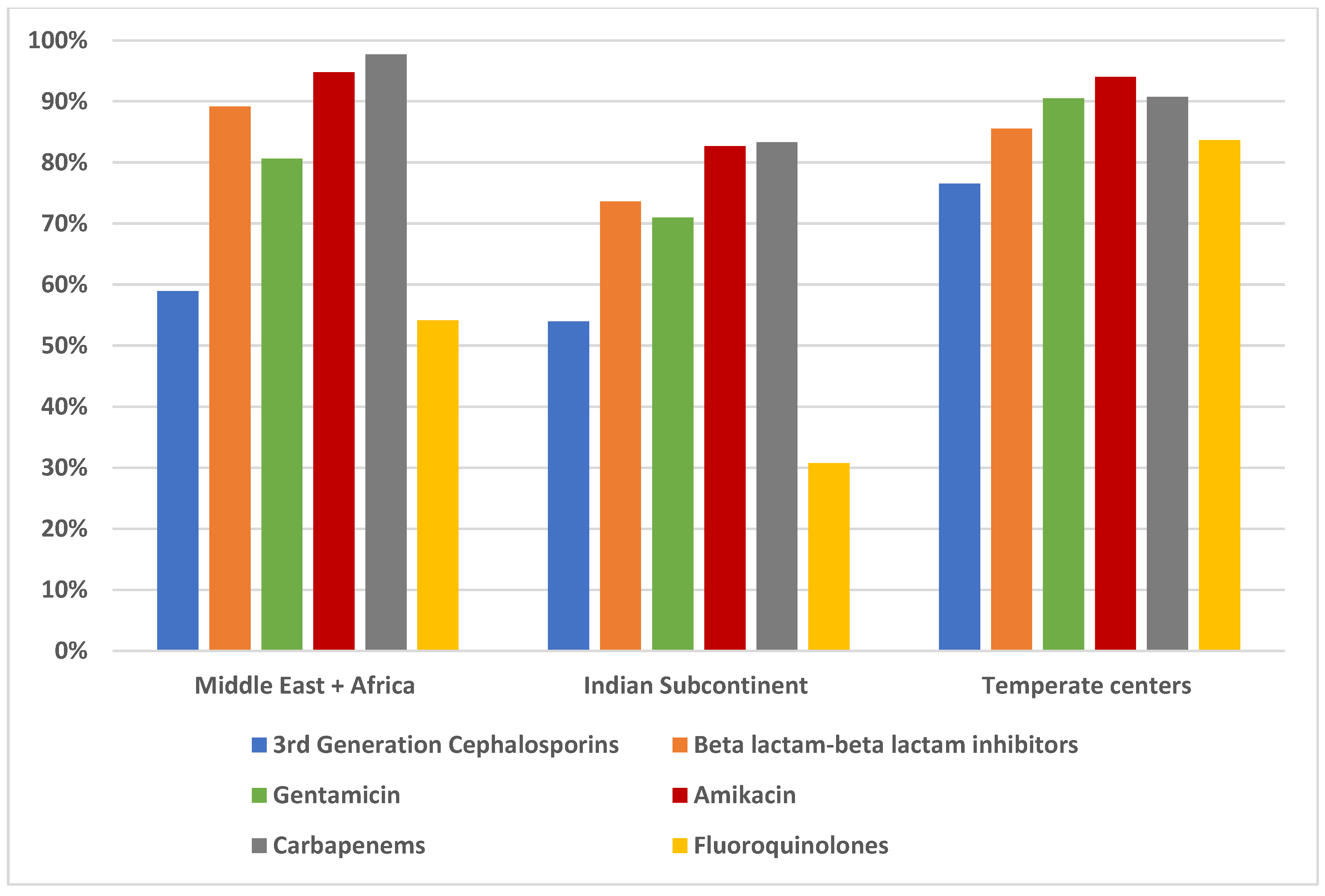

Figure 2, with regional rates of intravenous antimicrobial groups in

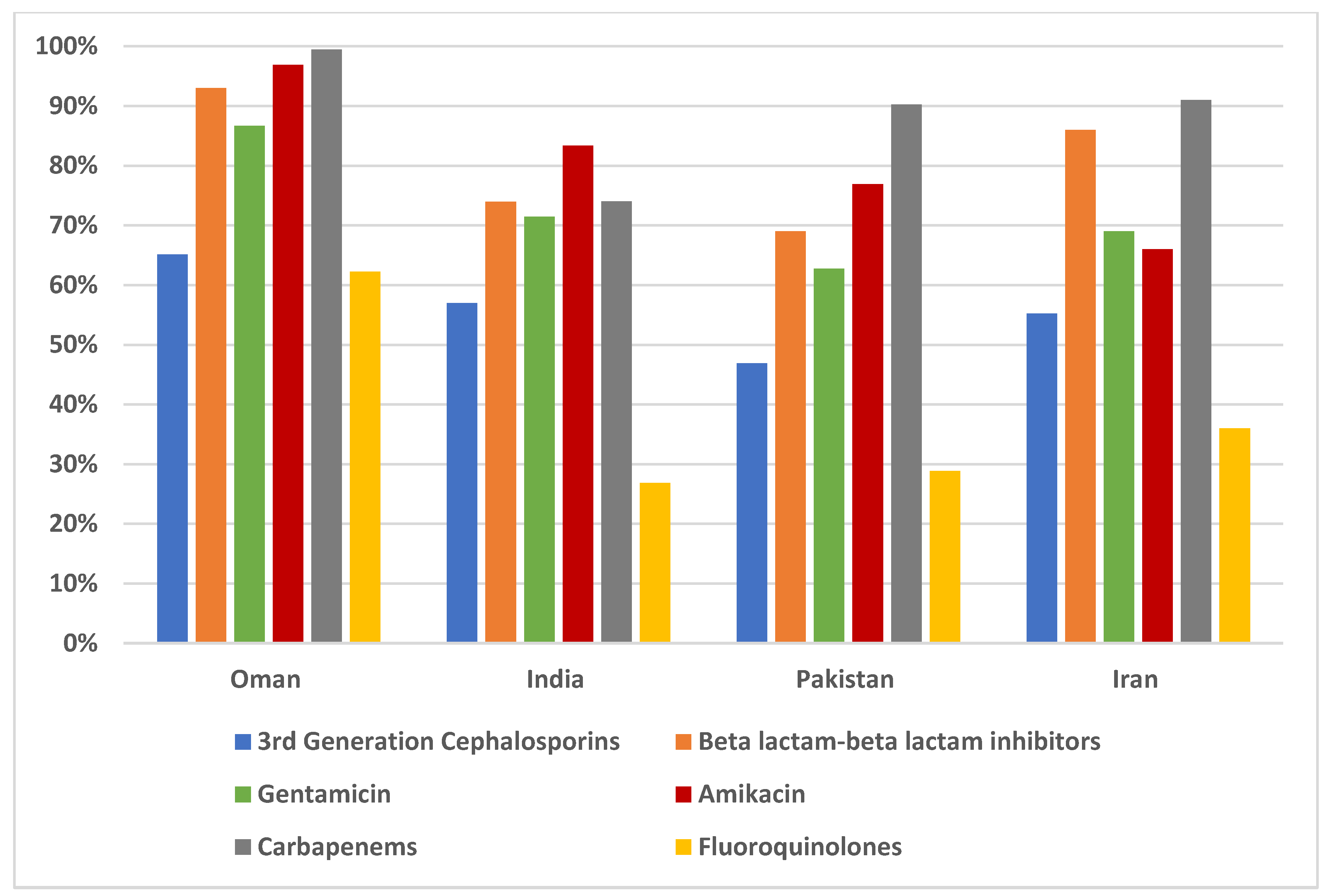

Figure 3 and between Oman, India, Pakistan and Iran in

Figure 4.

Supplementary Table S1 shows the range and HM of susceptibilities by regions. The susceptibilities discussed below among different drug classes are the HM.

3rd Generation Cephalosporins: average of ceftazidime and ceftriaxone. Beta lactam-beta lactam inhibitors: piperacillin-tazobactam. Carbapenems: average of imipenem and meropenem. Fluoroquinolones: ciprofloxacin.

3rd Generation Cephalosporins: average of ceftazidime and ceftriaxone. Beta lactam-beta lactam inhibitor: piperacillin-tazobactam. Carbapenems: average of imipenem and meropenem. Fluoroquinolones: ciprofloxacin.

Fosfomycin: In both India (91-100%) and Pakistan (84-100%), the overall susceptibility was 96%, with 100% susceptibility observed in W. India (Jaipur), three in Pakistan (two: Peshawar, one: Karachi). Two centers in E. India had a high susceptibility of 98-99%. Of the two centers in Oman who tested it, one reported 100% while the other 96% susceptibility and Al Wakra, Qatar reported 96%, Maldives: 99%, Cairo: 89%, Benin: 95%, Dnipro: 82%, London: 97%.

Overall, the susceptibility to nitrofurantoin was 89%. The susceptibility ranged from 96-98%, in Oman. The primary health centers linked to Al Nahda and Khoula hospitals, Muscat (98%) demonstrated the highest susceptibilities. In Al Wakra, and Buraydah, the susceptibilities were 97% and 92%, respectively. Amongst the LMICs in MENA, it was lower (86%) in Tehran, although in Sari, it was 91%. Cairo reported 86%.

In the Indian Subcontinent, the susceptibility in decreasing order was 95% in Maldives, 86% in Bangladesh, 85% (73-100%) in India, and 83% (77-97%) in Pakistan. Concerningly Bhopal (C. India) and Gurgaon, N. India demonstrated susceptibilities below 75%. In Pakistan, large variations were observed, from a high of 97% in Karachi to a low of 77% in Lahore.

In HIC temperate countries, London had higher susceptibility (99%) than Toronto (88%) while Ukraine, an LMIC, had 85%.

Co-trimoxazole: The antimicrobial susceptibility to co-trimoxazole was 64% (56-72%) in Oman. Al Wakra reported 57% and Buraydah, 50%. Mean in Iran was 42%,( 26% in Tehran, 51% in Sari), Cairo had 39% susceptibility and Benin,10%. In the IS, Maldives was high at 70%, others demonstrated low susceptibility: India: 55%; Bangladesh: 52%; Pakistan: 34% (22-84%); In temperate regions, Toronto susceptibility was 79%, Dnipro (74%) and London (70%).

The susceptibility was 32% in Oman (17-50%), 30% in Al Wakra, 22% in India (25-43%), 19 % in Iran, 17% in Pakistan, 9% in Cairo and Dnipro.

Cefazolin susceptibility was 43% in Oman (16-62%). Sari, Iran reported 22% and Cairo, 45%. Kalyani was 31%, Dnipro was 33% and London was high at 65%.

Third- and fourth- generation cephalosporins: Ceftazidime fared better than ceftriaxone. The highest susceptibility to ceftazidime was observed in London, 89%, Maldives (83%) in the IS and Al Wakra (80%) in MENA, and the lowest in Benin (3%). In Oman, India and Dnipro, similar susceptibility rates were observed (63%-65%), while it was 55% in Buraydah, 52% in Iran, 47% in Cairo, and 36% in Dhaka.

Cefepime susceptibility was again highest in Qatar (83%), and lowest in Iran (23%), while it ranged from 48%-68% in the Middle East and the Indian subcontinent. Dnipro and Buraydah reported the same susceptibility. (57%).

Beta-Lactam-beta-lactamase inhibitors: In MENA, piperacillin-tazobactam rates varied from 93% (92-100%) in Oman, 92% in Al Wakra, 85% (72-94%) in Iran to 75% in Buraydah, 67% in Cairo. In the IS, the susceptibility was 90% in Maldives, 80% (40-87%) in India, 77% in Bangladesh and 64% in Pakistan (41-88%). In the higher latitudes, Dnipro had 85%, London, 86%.

The median was 68% (41-96%) for amoxicillin-clavulanic acid in Oman; 62% (10-66%) in India, 33% (3-67%) in Pakistan, 32% in Dhaka and 75% (74-75%) in Iran. In Al Wakra, it was 75%, 60% in Buraydah. Cairo and Benin had similar susceptibility, 35% and 37%, respectively. London susceptibility was 62%, Dnipro was higher at 82%.

Carbapenems: In Oman, susceptibility was 99% (98-100%) each for meropenem and imipenem, 98.5% in Al Wakra; 97% in Buraydah; 91% in Iran; 86% in Cairo. In the IS, 100% was observed in Bangladesh and 94% in Maldives, followed by Pakistan 90% (84-96%); 76% (40-95%) in India; 99% in London, 88% in Dnipro, 95.5% in Benin.

Fluoroquinolones: Ciprofloxacin rate in Oman was 61% (48-83%), 51% and 52% in Buraydah and Al Wakra respectively, 39% in Cairo, 16% ( 6-47%) in Pakistan, 21% (9-52%) in India, 26% (14-48%) in Iran, 41% in Bangladesh and 57% in Maldives. It was very low in Benin (14%). In Dnipro, it was 76% and it was excellent in London, 86% and 89% in Toronto.

Aminoglycosides: Gentamicin rates were 87% (80-94%) in Oman, 85% in Al Wakra, 80% in Buraydah, 57% in Pakistan (43-80%), 65% (42-94%) in India, 85% in Bangladesh, 86% in Maldives, 62% (41-84%) in Iran, 79% in Cairo and 47% in Benin. In the colder countries, Dnipro reported 88%, London, 93%.

Amikacin susceptibility was much higher. It was 100% in Oman (98-100%), 99% in Al Wakra, 97% in Buraydah, 68% in Pakistan (53-87%), 79% in India (55-100%), 92% in Bangladesh, 97% in Maldives, 66% in Iran, 94% in Cairo. It was 100% in the London and 88% in Dnipro.

The influence of temperature, humidity, GDP, and population density on antimicrobial susceptibility is outlined in

Table 3. There was a notable correlation between the susceptibility of E. coli and GDP, with higher susceptibilities observed in high-income countries (p < 0.001), as well as with high temperature (p=0.03) and humidity (p=0.003). No significant association was found with population density or low temperature.

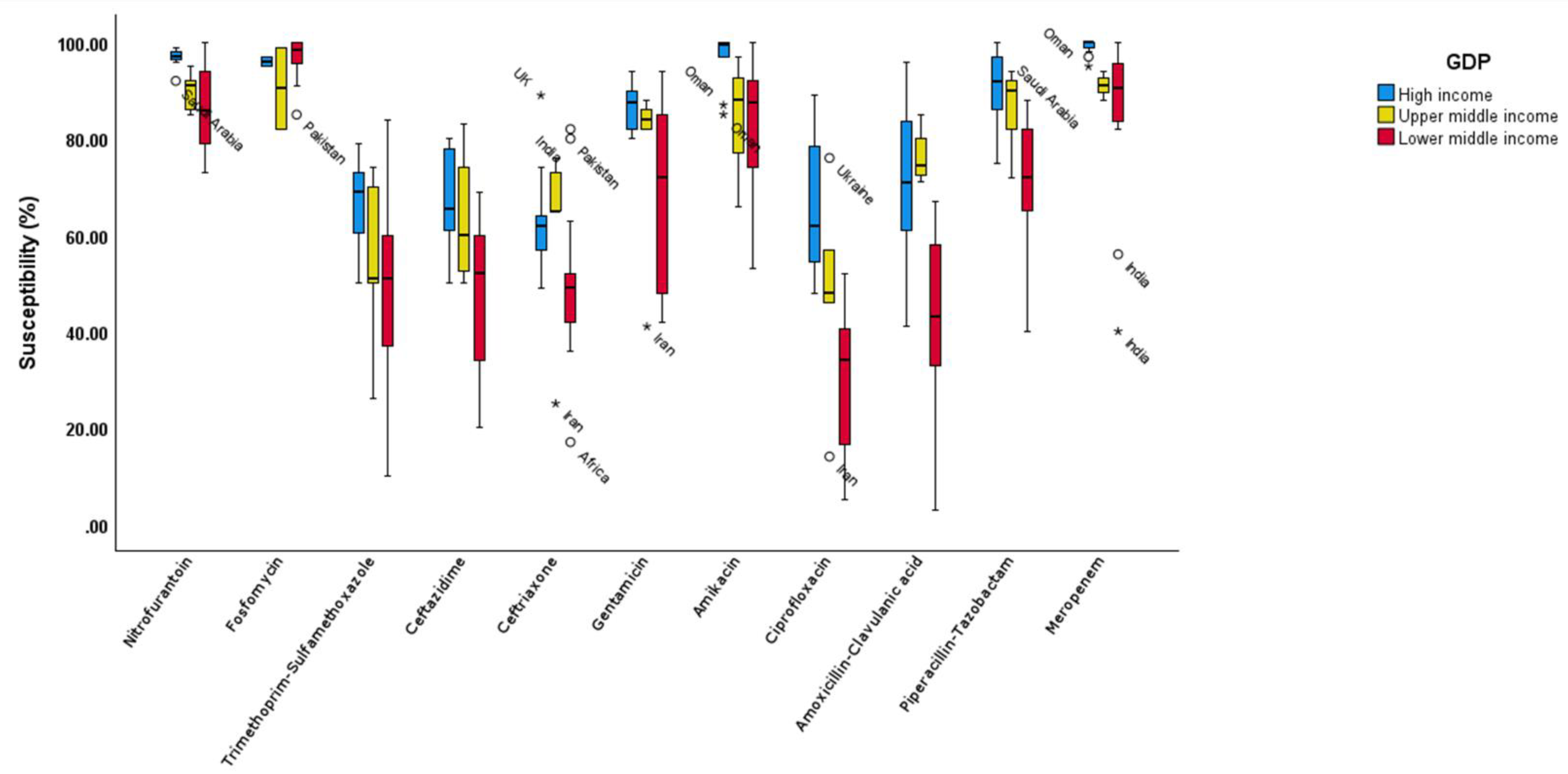

There was a significant difference between the three GDP groups within each drug (

Figure 5) and

Supplementary Table S2 (p <0.05), except for fosfomycin (p 0.432) and ceftriaxone (p = 0.081) . The post hoc analysis revealed significant susceptibility differences between lower-middle and high-income countries across all drugs (p <0.05) except the two mentioned drugs before.

The two-way ANOVA according to the subgroup of regions showed that the pattern in the specific areas differs from the overall pattern.

Table 4 shows that in the MENA region, both GDP and high temperature significantly affect

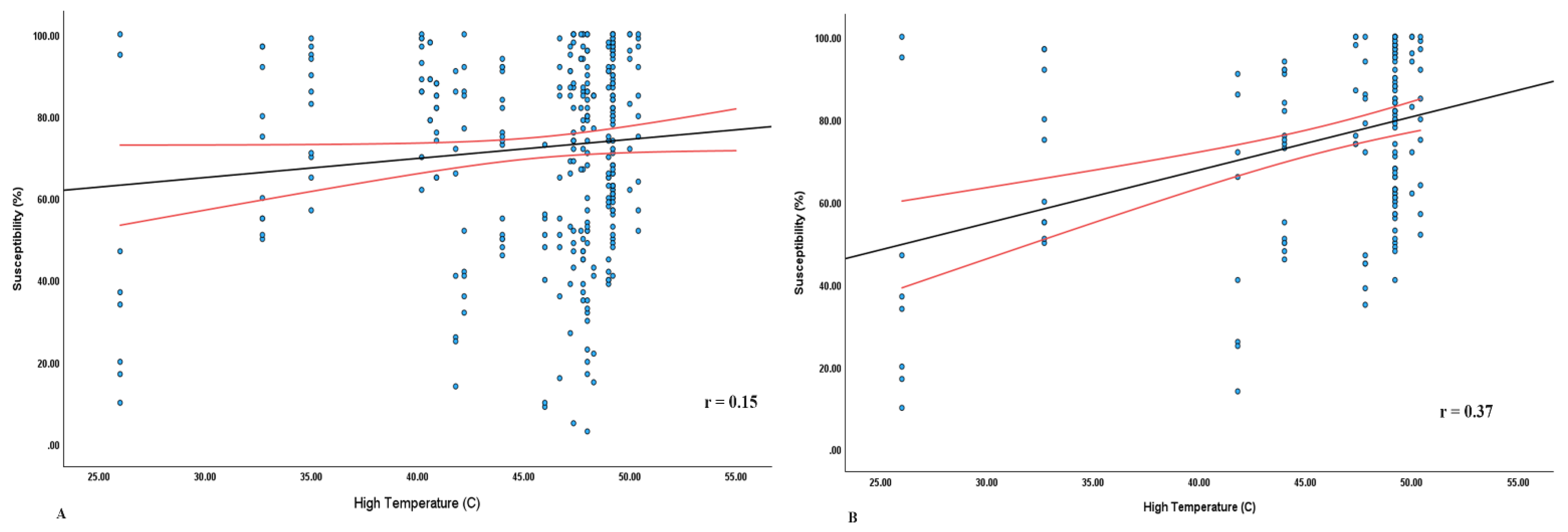

E.coli susceptibility (p < 0.001). The relationship between the high temperature and susceptibility is shown in

Figure 6, where a steeper slope (r =0.37) is seen in MENA than in the overall study sites (r=0.15).

When we looked at the relationship between GDP levels and drug susceptibility in different regions, we found significant differences in the MENA region. Specifically, we observed differences in the average susceptibility to nitrofurantoin (p = 0.014), ceftazidime (p = 0.029), and ciprofloxacin (p = 0.007) concerning GDP levels (

Supplementary Table S3).

In India, different antimicrobials and GPD have a significant effect on the proportion of E. coli susceptibility (p < 0.05). In temperate regions, the drug alone had a statistically significant effect on the proportion of susceptibility (P = 0.016) (

Table 4).

Furthermore, to investigate any differences between two large countries in the IS region, a comparison was performed between India and Pakistan. No significant differences were observed between them, although many antimicrobials had a higher mean in India. (

Supplementary Table S4).

Discussion

Management of simple UTI in the era of spiralling AMR must be supported by local antibiograms which reflect the community. Combined outpatient and in-patient antibiograms are not advised (8).

In this study, the antimicrobial susceptibility of community associated uropathogenic E. coli, is presented across 38 centres in 13 countries (8-LMICs and 5 HICs) in the Northern hemisphere. The southernmost, Maldives, lies on the Equator. Majority (29 centres) were situated between 200-300 latitude.

The susceptibility to all classes of antimicrobials was significantly higher in the high-income countries (HIC) compared to low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) (p < 0.001). The significant differences in susceptibility were notable between the three GDP groups for each drug. The association of higher GDP with better susceptibility suggests a higher standard of living, improved healthcare access, and more rational use of antimicrobials.

Moreover, the result showed that high temperature (p=0.03) and humidity (p=0.003) had statistically significant effects on the proportion of susceptible E. coli. There were no observable differences due to geographic locations or population density per sqkm, and low temperature had no significant effect. It is important to monitor the effects of high temperature and humidity on microbial populations in different geographical regions. Our results contrast with McFadden’s findings, where it was reported that increasing average minimum temperatures are associated with increasing AMR. However, that study assessed rise in temperatures over the last thirty years while we assessed impact of high and low temperatures across different locations in a single year. (9)

The subgroup analysis based on geographic regions showed that high temperatures had a positive impact on susceptibility in the MENA region (p<0.001). It appears that the high temperatures in MENA influence E. coli susceptibility. The extreme heat may inhibit bacterial proliferation and mutation, accounting for lower resistance. Further research is needed to clarify the mechanisms underlying the relationships between AMR and temperature (3).

In HICs, susceptibility rates to nitrofurantoin, fosfomycin (where tested) were ≥ 95%, aminoglycosides and carbapenems were ≥ 85% and piperacillin-tazobactam ≥ 79%. The ≤ 60% susceptibilities to cotrimoxazole, cephalosporins and fluoroquinolones in the majority of the Asian and African centres suggests they should not be prescribed empirically. Two temperate centres retained ≥ 85% susceptibility to fluoroquinolones and all three retained ≥ 70% susceptibility to cotrimoxazole.

Nitrofurantoin: The susceptibility was 89% overall. In both the ME and temperate HIC, nitrofurantoin susceptibility was high (97% and 98.5% respectively) which were corroborated by studies in Europe (100%) and Toronto (97.5%) (10,11). LMICs, were characterized by 10-15% lower rates than HIC (90% in Iran, 88% in India, 86% in Bangladesh, 85% in Ukraine, 78% in Pakistan, 75% in Egypt. Ebrahim Rezazadeh Zarandi et al 2023 (12) reported 86.5% susceptibility in Kerman, Iran. Mykhalko et al (13) in Ukraine reported rates close to ours. Islam et al, 2022 (14) reported lower, 70% susceptibility to E. coli from Bangladesh. AL Mamari et. al. (15) reported high susceptibility from Oman. Significant regional variations were observed in India and Pakistan. N. and E. India had high susceptibilities (94%-98%) as did Karachi (97%) in Pakistan while several centres had ≤ 80% susceptibilities. Higher susceptibilities were previously reported from Pakistan. (16,17).

The higher susceptibility of nitrofurantoin may be linked to lower consumption rates in some countries such as in Oman where consumption may be low due to G6PD (the prevalence of G6PD in Oman is 20-25 % (18).

Eleven out of thirteen participating countries tested fosfomycin. In the Middle East, it is usually not routinely tested. Fosfomycin emerged as the most active antimicrobial in vitro, with both India and Pakistan, reporting high HM ≥ 96%. Kalyani and Bhubaneswar in E. India reported 98-99% as did Maldives and Benin (95%), which were consistent with other reports (19–21). Cairo and three centres in Pakistan (two: Peshawar, one: Karachi) reported 100% susceptibility. Declining fosfomycin susceptibilities (94-92%) in E. coli causing uncomplicated UTI have been reported from Pakistan and Egypt (61.5%) (17,22–24). Dnipro at 82% was lower than previous reports (98%) from Ukraine (25). Thus, fosfomycin as a single oral dose of 3 grams is an alternative choice for uncomplicated cystitis for prescribers struggling with widespread resistance. Monitoring of resistance is essential, as reports of resistance are emerging (26). It is important to bear in mind that fosfomycin is a useful salvage drug for infections involving extremely- and pan- drug resistant bacteria.

However, higher clinical and microbiologic cure was observed with 5-day nitrofurantoin than single dose Fosfomycin (27). Multiple doses of fosfomycin have been considered in complicated UTI but not in simple cystitis (28).

Significant variations in cotrimoxazole susceptibility were observed between HIC and LMIC, (79% in Toronto to 10% in Benin), rates which were corroborated by Marchand-Austin et al.,2022 and Assouma et al., 2023 (11,29). Among the HIC, the susceptibility was ≥ 70% in the temperate ones and ≤ 60% in Qatar and Saudi Arabia. Oman fared better, 66% (74% in Ibri health centres to 56% in a centre in Muscat). Maldives, topped with (70%) in IS, followed by India (61%) and Pakistan (35%) Similar rates have been reported others (20,30).

Fluoroquinolone sensitivity in the temperate sites was excellent: Toronto (89%), London (86%) which are higher than a previous report from Toronto (83%) but lower than rates reported from England (7.6%) (11,31) followed by Dnipro, 76%. Salmanov et al have reported similar susceptibilities in Ukraine (25). In the HIC ME, ciprofloxacin susceptibility ranged between 51%-60%. Lower ciprofloxacin rates (35.86%) were reported by Sid et al among Gram negative bacilli (32). Rates from Maldives (57%), Cairo (45%) and Bangladesh (41%) were double that observed in Iran (26%) and India (21%). Similar rates have been reported previously. Benin was 34%. Lowest susceptibility (16%) was observed in Pakistan which was less than half that (35%) reported a decade earlier (33).

Ciprofloxacin rates were comparable to that of co-trimoxazole in Oman, Qatar, KSA (61% vs 64%), Doha, Qatar (52% vs 57%) and Buraydah, KSA (51%-50%), Iran (26% vs 38%) and Dhaka 41%-52%). Ebrahim Rezazadeh Zarandi et al 2023 (12) reported the reverse in Iran, 66.7% vs 77%. The difference was striking in India (21% vs 55%), Pakistan (16%-34%) and Maldives (57%-70%). These findings were corroborated by Khursheed N et al (17). In contrast, fluoroquinolones fared better in London (86% vs 70%) and Toronto (89% vs 79%) than co-trimoxazole which was borne out by others (11,31).

Augmentin rates were better than ciprofloxacin in Oman (71% vs 61%), India (29% vs 21%), Iran (74%-26%), as also in Qatar, KSA, Maldives and Ukraine. Similar results have been reported by others. Salmanov et al 2023 (25). The exceptions were London (62% vs 86%), Dhaka (32% vs 41%) and Cairo (35% vs 45%). Carter et al (31) and Tarek et al (34) reported better augmentin susceptibility.

Ceftriaxone susceptibility (65-45%) was lower than that of ceftazidime (83-52%) in Maldives, Qatar, Oman, India and Iran in that order, suggesting higher prevalence of CTX-M enzymes. London (89%) and Male (83%) had the highest susceptibilities to ceftazidime while Benin reported lowest (20%), which was corroborated by Assouma et al (29). A much lower susceptibility (51%) was reported from Qatar in Gram negative bacilli, (32). A study from Iran reported similar susceptibility (57.5%) to ceftazidime (12). In Dnipro susceptibility to both was 65% which contrasts with the higher rate (89-86%) in a previous study (25). Similar susceptibility to both was observed in Buraydah, (55% to both) and Cairo, (ceftriaxone-45% vs ceftazidime-47%). In Pakistan and Dhaka, ceftriaxone susceptibility was superior to ceftazidime’s (56% vs 30% and 42% vs 36% respectively). Despite low national averages, a site each in India and Pakistan had high ceftriaxone susceptibility rates ≥ 80%. Balochistan in Pakistan reported lower susceptibilities to ceftriaxone (35.65% ), cefotaxime (24.46%), ceftazidime (50.57%), cefepime (46.56 %) among uropathogenic E.coli. (35). Previously 70% susceptibility to ceftriaxone, 72% to ceftazidime and 73% to cefipime was reported from Oman (30).

Cefepime susceptibility largely mirrored ceftazidime susceptibility. It was highest in Qatar, 83% and lowest in Iran, 23%. Much higher susceptibility (53.2%) was reported from Isfahan, Iran. Buraydah and Dnipro both had 57% and Cairo, 50%. Tarek et al reported lower (45%) susceptibility from Egypt (34). In the Indian subcontinent, cefepime susceptibility varied widely: Maldives (75%), Pakistan (64%), Bangladesh 58% and India 57% which was higher than another report (10%) from N. India (36). This seems to be the first report from Maldives. In the ME HIC, the strict antimicrobial stewardship and its intravenous formulation make cefepime difficult to use routinely, thus accounting for its excellent susceptibility.

ESBL prevalence (as estimated by resistance to ceftriaxone) in countries with multiple sites in increasing order was as follows: 40% in Oman, 44% in Pakistan, 52% in India and 55% in Iran. In the period between 2013 and 2018, E. coli emerged as the largest ESBL producer (26%) in Oman (15). Among the single sites, Dnipro and Male had 35%, Qatar, 36%, Cairo 55%, Dhaka 58%, Benin 83% ESBL prevalence.

Excellent susceptibilities to piperacillin tazobactam (>90%) were observed in the ME HIC except for Al Buraydah, KSA (75%) Similar rates were reported by Ahmed et al (37) from Buraydah. Maldives too reported 90%. Susceptibility in Iran was similar to India and Bangladesh (near 80%), while Pakistan and Cairo both reported around 65%. Malik et al (38), from Rawalpindi, Pakistan reported 72.57% susceptibility of piperacillin tazobactam to uropathogenic Escherichia coli. Dnipro and London characterized with temperate climate reported 85% and 86% respectively, which was lower than that of Oman and Qatar. Population per square km is lower <500 in Oman and Qatar, which may play a role, as London and Dnipro have populations per sq km which are many fold higher.

Pakistan and Bangladesh had half the rates,33%-32% respectively, to amoxicillin-clavulanic acid than India (62%). Egypt and Benin had low susceptibilities, 35% and 37%, similar to Pakistan and Bangladesh. Ehsan et al (39) from Pakistan reported 83% susceptibility to amoxicillin-clavulanic acid among ESBL producing uropathogenic E.coli. Qatar and Iran both had 75% which was surprising considering the disparities in income. Susceptibility in London was 65%, while Dnipro, was higher at 82%. Thus interestingly, Oman (hot, low latitude) and Ukraine (temperate) susceptibilities (>80%) were similar and London (Temperate, high latitude) and Al Buraydah (hot, low latitude) were similar.

Our study highlights the importance of OPD based antibiograms to better understand the susceptibility in the community and promote evidence based prescribing.

Amongst aminoglycosides, gentamicin susceptibility was above 80% in the ME HIC and the temperate West, (Oman, 87%, Qatar, 85%, 80% in KSA, London, 93% Dnipro, 88%). El-Naggari et al (40) reported 90% susceptibility to gentamicin in E. coli causing recurrent UTI in children in Oman. In the IS, Maldives and Bangladesh had similarly high susceptibility of 86% and 85% respectively. Other reports from Bangladesh reveal 67.39% and 71.80% susceptibility to gentamicin (41,42). In the other LMICs,it ranged from 65% in India to 62% in Iran, 60% in Egypt and 57% in Pakistan. Ehsan et al (39) reported 79% susceptibility to gentamicin among ESBL producing E.coli in urinary isolates from Pakistan and 47% in Benin (12).

Amikacin displayed excellent rates in HICs and several LMICs with 100% in Oman, 99% London, 97% Qatar, and KSA, and Maldives, 92% in Bangladesh and 88% in Dnipro. Similar findings have been reported by others (41,42). It was between 65%- 80% in India (79%), Cairo (70%), Pakistan 68% followed by 66% in Iran. Jamil et al (Swabi, Pakistan) (43) reported higher sensitivity to amikacin (76%) among uropathogenic E.coli. Hesam alizade, 2018 (44) reported varying susceptibility to aminoglycosides across Iran.

Susceptibility to carbapenems was excellent in most HIC and LMIC sites: Dhaka,100%; Oman, and London,99%; Al Wakra, 98.5%; Buraydah, 97%; Benin 95.5%, Male 94%; Pakistan, 91% Iran. It was 89% in India (barring two outliers:40% in Gurugram and 56% in Bhopal) and Dnipro 88%. Saleem et al. (2018) (22) from Pakistan, reported 87.4% and 84.8% susceptibility to imipenem and meropenem respectively, while Sid et al reported 100% E. coli susceptibility to meropenem in ICUs in Qatar. Saied Bokaie et al 2021 (45) reported a lower susceptibility of 76% from Mashhad, Iran, while 92.5% and 95% susceptibilities were reported from Bangladesh (14,42). Prior studies from Oman report excellent carbapenem susceptibilities (40,46). Ahmed et al (37) reported similar rates from Buraydah, Al Qassim.

The same susceptibility in temperate and hot climate suggests that climate per se may not have a role but GDP was identified as a significant factor impacting susceptibility. High temperature was identified as a contributary factor in the MENA region. While studies have reported increased Gram negative infections in warmer seasons, we appear to be the first to compare temperature and humidity in different regions with susceptibility rates in uropathogenic E. coli.

Conclusions

There is a high degree of variability in E. coli susceptibility between and across regions. This can be at least partially explained by geographic (e.g., temperature) and economic (e.g., GDP) factors.

Our study reveals that GDP significantly impacts E. coli susceptibility in community associated UTI. HIC exhibited significantly higher susceptibilities compared to LMICs, reinforcing the importance of improving healthcare infrastructure, promotion of vaccination, WASH, public awareness, antimicrobial and diagnostic stewardship efforts in LMICs. The favourable impact of high temperatures in the Middle East on E. coli susceptibility points to the need of further study in this area. Despite the variability observed, nitrofurantoin and fosfomycin generally retain good activity against E. coli across the studied regions and characterised with low collateral damage, they may be recommended as first-line antibacterial agents for uncomplicated community-acquired UTIs.(27) Access to these agents should be balanced against the need for antimicrobial stewardship to limit their use to symptomatic infections and preserve their effectiveness. With rising resistance to the routine antimicrobials, ME may benefit with access to fosfomycin for management of simple cystitis. Sequential prescribing of the top three or four antimicrobials rather than reliance on one antimicrobial may stave off resistance.

Our data may be skewed towards resistance as samples from complicated, unresponsive and recurrent cases are more often sent for culture and susceptibility testing. (28) To obtain a more representative picture we need to collect samples from exclusively patients with simple cystitis.

Screening of Ante natal cases attending the Obstetrics and Gynaecology OPD clinics may provide a more representative data for understanding the community susceptibility profile of E. coli. It will be interesting to explore the evolving molecular modes of resistance keeping in mind the high level of travel amongst these countries.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on

Preprints.org.

Acknowledgement

We are grateful to Dr David M. Livermore for his superlative oversight and generous guidance to us since the inception of DASH to Protect Antibiotics. We have been enriched with his formidable wisdom and knowledge and have learnt tremendously under his able mentorship. We are indebted to Dr. Arjun Srinivasan retd US (CAPT), Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, Georgia, USA., for his constant support and guidance throughout the study.

References

- Falagas ME, Peppas G, Matthaiou DK, Karageorgopoulos DE, Karalis N, Theocharis G. Effect of meteorological variables on the incidence of lower urinary tract infections. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis Off Publ Eur Soc Clin Microbiol. 2009 Jun;28(6):709–12. [CrossRef]

- Minisha F, Mohamed M, Abdulmunem D, El Awad S, Zidan M, Abreo M, et al. Bacteriuria in pregnancy varies with the ambiance: a retrospective observational study at a tertiary hospital in Doha, Qatar. J Perinat Med. 2019 Dec 18;48(1):46–52. [CrossRef]

- Zeng Y, Li W, Zhao M, Li J, Liu X, Shi L, et al. The association between ambient temperature and antimicrobial resistance of Klebsiella pneumoniae in China: a difference-in-differences analysis. Front Public Health. 2023 Jun 8;11:1158762. [CrossRef]

- Rizvi M, Malhotra S, Agarwal J, Siddiqui AH, Devi S, Poojary A, et al. Regional variations in antimicrobial susceptibility of community-acquired uropathogenic Escherichia coli in India: Findings of a multicentric study highlighting the importance of local antibiograms. IJID Reg. 2024 Jun;11:100370.

- Clinical & Laboratory Standards Institute [Internet]. [cited 2024 Sep 6]. M100 Ed34 | Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing, 34th Edition. Available from: https://clsi.org/standards/products/microbiology/documents/m100/.

- Flores-Mireles AL, Walker JN, Caparon M, Hultgren SJ. Urinary tract infections: epidemiology, mechanisms of infection and treatment options. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2015 May;13(5):269–84. [CrossRef]

- Hindler JA, Simner PJ, Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, editors. Analysis and presentation of cumulative antimicrobial susceptibility test data. 5th ed. Wayne, PA: Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards; 2022. 176 p. (Documents / Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute).

- Calvo-Villamañán A, San Millán Á, Carrilero L. Tackling AMR from a multidisciplinary perspective: a primer from education and psychology. Int Microbiol Off J Span Soc Microbiol. 2023 Jan;26(1):1–9. [CrossRef]

- MacFadden DR, McGough SF, Fisman D, Santillana M, Brownstein JS. Antibiotic Resistance Increases with Local Temperature. Nat Clim Change. 2018 Jun;8(6):510–4.

- Tutone M, Bjerklund Johansen TE, Cai T, Mushtaq S, Livermore DM. SUsceptibility and Resistance to Fosfomycin and other antimicrobial agents among pathogens causing lower urinary tract infections: findings of the SURF study. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2022 May;59(5):106574. [CrossRef]

- Marchand-Austin A, Lee SM, Langford BJ, Daneman N, MacFadden DR, Diong C, et al. Antibiotic susceptibility of urine culture specimens in Ontario: a population-based cohort study. CMAJ Open. 2022;10(4):E1044–51. [CrossRef]

- Frequency of Extended-Spectrum Beta-Lactamases-Producing Escherichia coli Among Out- and In-patients in Rafsanjan City, Iran - ProQuest [Internet]. [cited 2024 Sep 6]. Available from: https://www.proquest.com/openview/d274105ca65f63a34fbfcc8804c9665e/1.pdf?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=55020.

- Mykhalko. SUSCEPTIBILITY OF THE UROPATHOGENIC ESCHERICHIA COLI STRAINS TO THE AMINOPENICILLINS AND NITROFURANS ANTIMICROBIALS IN 2015.

- Islam MA, Islam MR, Khan R, Amin MB, Rahman M, Hossain MI, et al. Prevalence, etiology and antibiotic resistance patterns of community-acquired urinary tract infections in Dhaka, Bangladesh. PloS One. 2022;17(9):e0274423. [CrossRef]

- Al Mamari Y, Sami H, Siddiqui K, Tahir HB, Al Jabri Z, Al Muharrmi Z, et al. Trends of antimicrobial resistance in patients with complicated urinary tract infection: Suggested empirical therapy and lessons learned from a retrospective observational study in Oman. Urol Ann. 2022;14(4):345–52. [CrossRef]

- Ali G, Riaz-Ul-Hassan S, Shah MA, Javid MQ, Khan AR, Shakir L. Antibiotic susceptibility and drug prescription pattern in uropathogenic Escherichia coli in district Muzaffarabad, Azad Jammu and Kashmir, Pakistan. JPMA J Pak Med Assoc. 2020 Nov;70(11):2039–42. [CrossRef]

- Khursheed N, Mal PB, Taimoor M. Frequency of isolation and susceptibility pattern of E. coli from in and outpatients over a period of five years at The Indus Hospital Network, Karachi Pakistan. JPMA J Pak Med Assoc. 2020 Sep;70(9):1587–90. [CrossRef]

- Al-Sheryani A, Al-Gheithi H, Al Moosawi M, Al-Zadjali S, Wali Y, Al-Khabori M. Molecular Characterization of Glucose-6-phosphate Dehydrogenase Deficiency in Oman. Oman Med J. 2023 Sep;38(5):e552. [CrossRef]

- Sugianli AK, Ginting F, Parwati I, de Jong MD, van Leth F, Schultsz C. Antimicrobial resistance among uropathogens in the Asia-Pacific region: a systematic review. JAC-Antimicrob Resist. 2021 Feb 27;3(1):dlab003. [CrossRef]

- Banerjee S, Sengupta M, Sarker TK. Fosfomycin susceptibility among multidrug-resistant, extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing, carbapenem-resistant uropathogens. Indian J Urol IJU J Urol Soc India. 2017;33(2):149–54. [CrossRef]

- Behera B, Mohanty S, Sahu S, Praharaj AK. In vitro Activity of Fosfomycin against Multidrug-Resistant Urinary and Nonurinary Gram-Negative Isolates. Indian J Crit Care Med Peer-Rev Off Publ Indian Soc Crit Care Med. 2018 Jul;22(7):533–6. [CrossRef]

- Saleem Z, Haseeb A, Abuhussain SSA, Moore CE, Kamran SH, Qamar MU, et al. Antibiotic Susceptibility Surveillance in the Punjab Province of Pakistan: Findings and Implications. Medicina (Mex). 2023 Jun 28;59(7):1215. [CrossRef]

- Abdelraheem WM, Mahdi WKM, Abuelela IS, Hassuna NA. High incidence of fosfomycin-resistant uropathogenic E. coli among children. BMC Infect Dis. 2023 Jul 17;23(1):475. [CrossRef]

- Bangash K, Mumtaz H, Mehmood M, Hingoro MA, Khan ZZ, Sohail A, et al. Twelve-year trend of Escherichia coli antibiotic resistance in the Islamabad population. Ann Med Surg. 2022 May 27;78:103855. [CrossRef]

- Salmanov AG, Artyomenko V, Susidko OM, Korniyenko SM, Kovalyshyn OA, Rud VO, et al. URINARY TRACT INFECTIONS IN PREGNANT WOMEN IN UKRAINE: RESULTS OF A MULTICENTER STUDY (2020-2022). Wiadomosci Lek Wars Pol 1960. 2023;76(7):1527–35. [CrossRef]

- Silver LL. Fosfomycin: Mechanism and Resistance. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2017 Feb 1;7(2):a025262. [CrossRef]

- Huttner A, Kowalczyk A, Turjeman A, Babich T, Brossier C, Eliakim-Raz N, et al. Effect of 5-Day Nitrofurantoin vs Single-Dose Fosfomycin on Clinical Resolution of Uncomplicated Lower Urinary Tract Infection in Women: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2018 May 1;319(17):1781–9. [CrossRef]

- Derington CG, Benavides N, Delate T, Fish DN. Multiple-Dose Oral Fosfomycin for Treatment of Complicated Urinary Tract Infections in the Outpatient Setting. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2020 Feb;7(2):ofaa034. [CrossRef]

- Assouma FF, Sina H, Adjobimey T, Noumavo ADP, Socohou A, Boya B, et al. Susceptibility and Virulence of Enterobacteriaceae Isolated from Urinary Tract Infections in Benin. Microorganisms. 2023 Jan 14;11(1):213. [CrossRef]

- Sharef SW, El-Naggari M, Al-Nabhani D, Al Sawai A, Al Muharrmi Z, Elnour I. Incidence of antibiotics resistance among uropathogens in Omani children presenting with a single episode of urinary tract infection. J Infect Public Health. 2015;8(5):458–65. [CrossRef]

- Carter C, Hutchison A, Rudder S, Trotter E, Waters EV, Elumogo N, et al. Uropathogenic Escherichia coli population structure and antimicrobial susceptibility in Norfolk, UK. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2023 Aug 2;78(8):2028–36. [CrossRef]

- Sid Ahmed MA, Petkar HM, Saleh TM, Albirair M, Arisgado LA, Eltayeb FK, et al. The epidemiology and microbiological characteristics of infections caused by Gram-negative bacteria in Qatar: national surveillance from the Study for Monitoring of Antimicrobial Resistance Trends (SMART): 2017 to 2019. JAC-Antimicrob Resist. 2023 Aug 3;5(4):dlad086. [CrossRef]

- Jafri SA, Qasim M, Masoud MS, Rahman MU, Izhar M, Kazmi S. Antibiotic resistance of E. coli isolates from urine samples of Urinary Tract Infection (UTI) patients in Pakistan. Bioinformation. 2014;10(7):419–22. [CrossRef]

- Tarek A, Abdalla S, Dokmak NA, Ahmed AA, El-Mahdy TS, Safwat NA. Bacterial Diversity and Antibiotic Resistance Patterns of Community-Acquired Urinary Tract Infections in Mega Size Clinical Samples of Egyptian Patients: A Cross-Sectional Study. Cureus. 16(1):e51838. [CrossRef]

- Hussain T, Moqadasi M, Malik S, Salman Zahid A, Nazary K, Khosa SM, et al. Uropathogens Antimicrobial Sensitivity and Resistance Pattern From Outpatients in Balochistan, Pakistan. Cureus. 2021 Aug;13(8):e17527. [CrossRef]

- Bhargava K, Nath G, Bhargava A, Kumari R, Aseri GK, Jain N. Bacterial profile and antibiotic susceptibility pattern of uropathogens causing urinary tract infection in the eastern part of Northern India. Front Microbiol. 2022;13:965053. [CrossRef]

- Ahmed SS, Shariq A, Alsalloom AA, Babikir IH, Alhomoud BN. Uropathogens and their antimicrobial resistance patterns: Relationship with urinary tract infections. Int J Health Sci. 2019;13(2):48–55.

- Malik J, Javed N, Malik F, Ishaq U, Ahmed Z. Microbial Resistance in Urinary Tract Infections. Cureus. 2020 May 14;12(5):e8110. [CrossRef]

- Ehsan B, Haque A, Qasim M, Ali A, Sarwar Y. High prevalence of extensively drug resistant and extended spectrum beta lactamases (ESBLs) producing uropathogenic Escherichia coli isolated from Faisalabad, Pakistan. World J Microbiol Biotechnol. 2023 Mar 24;39(5):132. [CrossRef]

- El-Naggari M, Al-Mulaabed S, Rabah F, Idrees AB, Muharrmi ZA, Nour IE. Urinary Tract Infection in Omani Children: Etiology and Antimicrobial Resistance. A Comparison between First Episode and Recurrent Infection. J Adv Microbiol. 2021 Mar 13;51–62. [CrossRef]

- Akter T, Fatema K, Nahar S, Sultana H, Alam S, Afrin S, et al. Spectrum of Antimicrobial Susceptibility of Escherichia coli Isolated from Urine Samples of a Tertiary Care Hospital of Bangladesh. 2020;24(03).

- Hossain G, Hossain E, Ahammed F, Mohammed R, Kabir MR, Karmaker G et al. Bacteriological profile and sensitivity pattern of urinary tract infection patients in north east part of Bangladesh. Int J Adv Med. 2020;7:1614-8. [CrossRef]

- Jamil J, Haroon M, Sultan A, Khan MA, Gul N, Kalsoom. Prevalence, antibiotic sensitivity and phenotypic screening of ESBL/MBL producer E. coli strains isolated from urine; District Swabi, KP, Pakistan. JPMA J Pak Med Assoc. 2018 Nov;68(11):1704–7.

- ALIZADE H. Escherichia coli in Iran: An Overview of Antibiotic Resistance: A Review Article. Iran J Public Health. 2018 Jan;47(1):1–12.

- Bokaie S, Demeshghieh AF, Farkhani EM, Shokri A. Antimicrobial Resistance Pattern of Escherichia Coli Isolated From Patients With Urinary Tract Infection in Tehran, Iran, in 2021. Epidemiol Health Syst J. 2022 Nov 6;9(4):160–3. [CrossRef]

- Al Rahmany D, Albeloushi A, Alreesi I, Alzaabi A, Alreesi M, Pontiggia L, et al. Exploring bacterial resistance in Northern Oman, a foundation for implementing evidence-based antimicrobial stewardship program. Int J Infect Dis IJID Off Publ Int Soc Infect Dis. 2019 Jun;83:77–82. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).