Submitted:

23 September 2024

Posted:

24 September 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1.0 Introduction

2.0 Literature Review

2.1. Instructional Design Competency Development

2.2. Adult Motivation in Learning

2.2.1. Adult Learning Theory

- Clearly stating the purpose of the awareness creation system and the values it offers them.

- Reawaken their intrinsic motivation by showing them ‘what is in it for them’ and getting them curious and challenged by painting them a beautiful picture of what it feels like to be an ID in the corporate world through the welcome video.

- Making the content of the experience relevant to them. This is why the audience of this experience is clearly defined and was limited to them.

- Give them control over the learning experience by making it self-paced and individualized.

- Include practical exercises that ensure they learn by doing through mentoring, peer interactions, and solving relevant case studies and scenarios.

- Make connections and build on their wealth of experience through the content of the experience.

- Use scenarios and case studies poscourse completion to put them in context of the job, and many more.

2.2.2. Engineering Motivation into IDSSAS System

- The goal to be achieved from the learning experience was clearly stated from the onset of the experience to condition their mind at a target to reach.

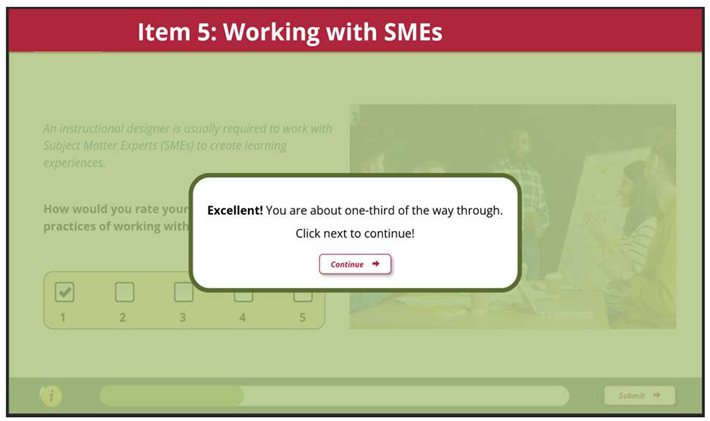

- I provided personalized encouragement at every point necessary (but not superfluously).

- Facilitated Peer-Based recognition by offering them a badge for awareness and competence.

- Used a progression bar to drive them to complete the sections.

- Provide assessment feedback and use praise that rewards effort and improvement.

- Offer support through email and calls to the users. My contact details are provided to them to ensure they are not deterred by any difficulty they may encounter during the experience.

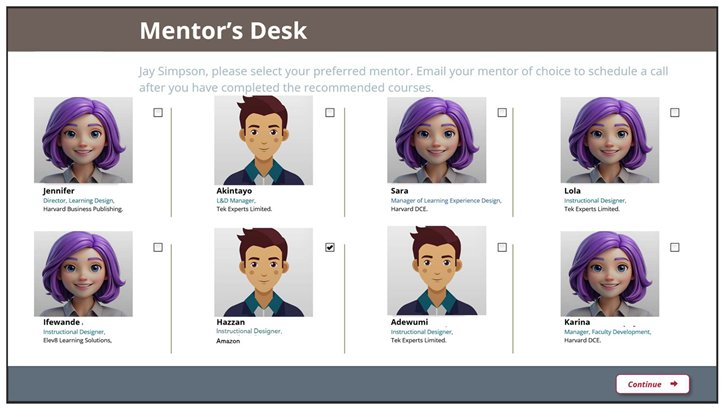

- Provided them with established mentors who were mostly professionals, who also transitioned into the field, to show them transitioning to the field can be done successfully.

2.3. Mentoring in Professional Development

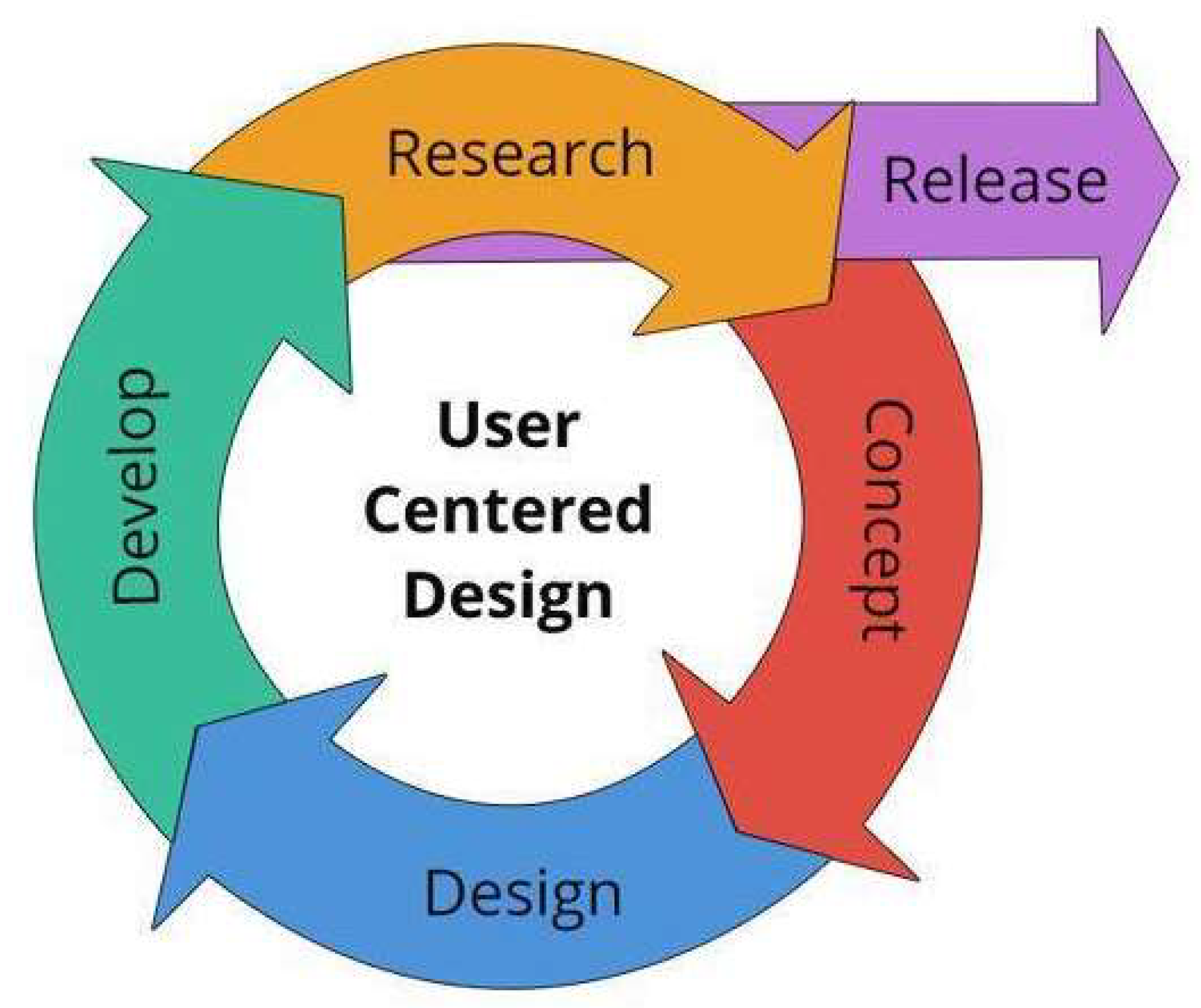

2.4. User-Centered Design (UCD)

3.0 ID Strength Assessment System Design

3.1. Overview of the Interactive Computer-Based Design

- Individual’s intrinsic motivation as our users want to be corporate IDs.

- Extrinsic motivation affordances like instant feedback, progression, badges, and the possibility of eventually getting the desired job.

- Protégé effect through access to mentors.

- Self-Determination Theory (SDT) through Relatedness, Competence, and Autonomy to make some choices.

- Growth mindset and self-efficacy.

3.2. Design Method and Approach

3.2.1. Research

3.2.2. Concept

3.2.3. Design

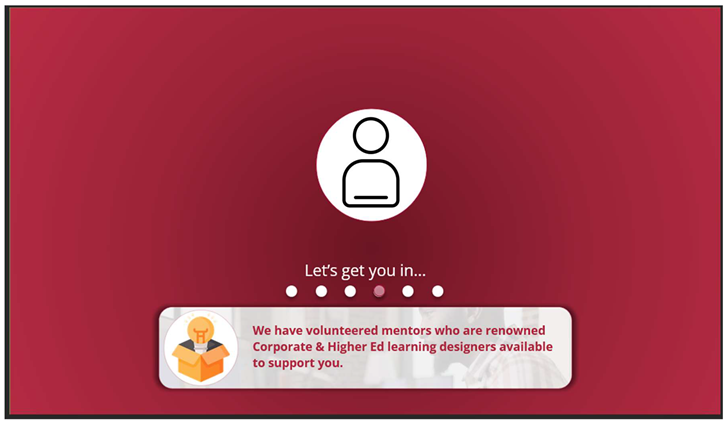

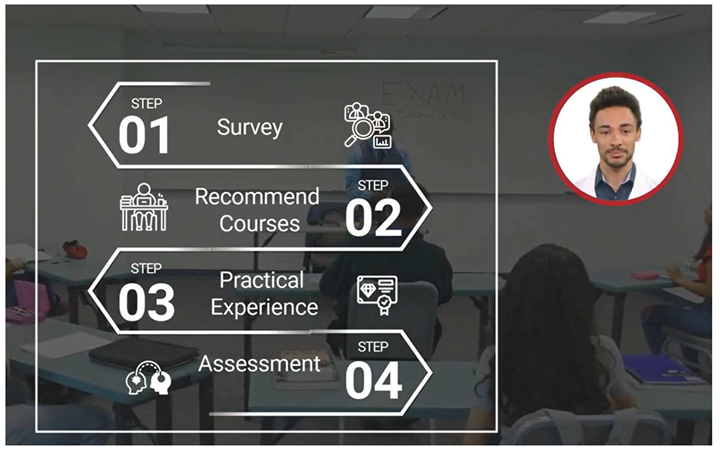

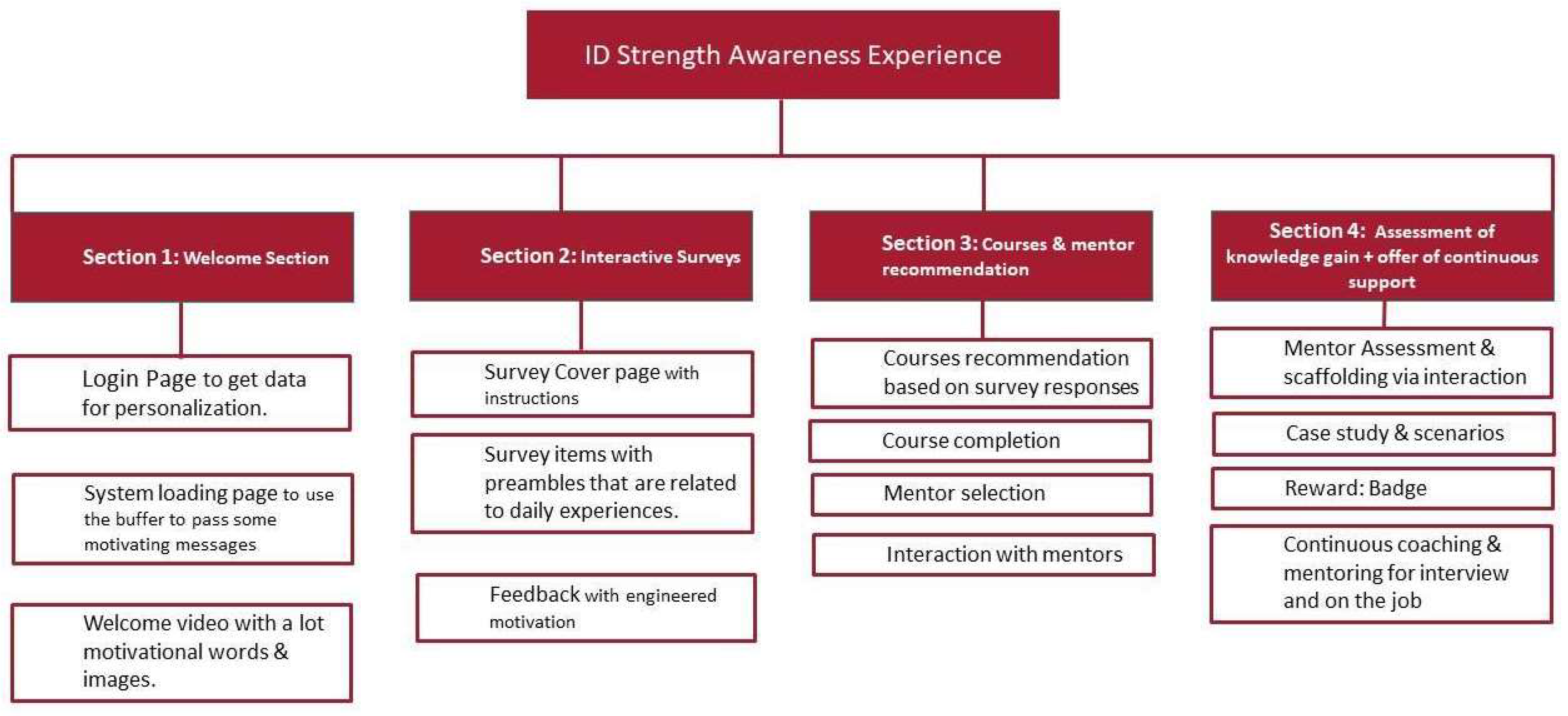

- Cover & login page: Allows the users to log in. This is an attempt to personalize the experience.

- Loading buffer: While the page loads, more motivational texts are displayed under a moving buffer to encourage users and break the ice.

- Welcome video: A video further breaking the ice and making the system more appealing to the users by validating the experience they bring into the system, sharing its importance and selling the field of Corporate Instructional Design to them. This video provides a brief on what to expect while also motivating them.

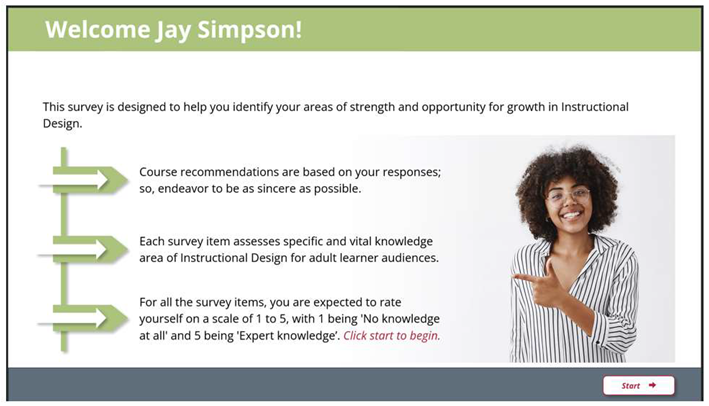

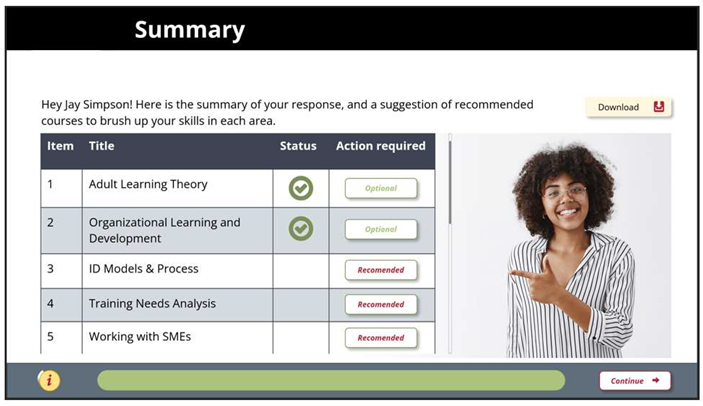

- Survey cover page: This page provides a personalized welcome message to the users and provides a summarized guidance about the survey.

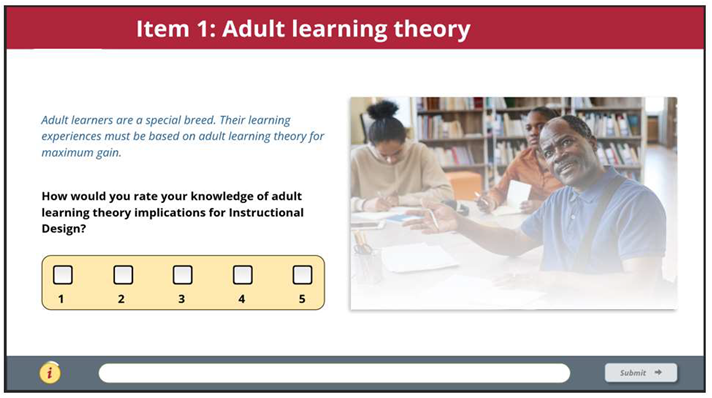

- Present the interactive survey items one after the other.

- Recommend courses based on the responses provided.

- Mentor selection page

- Interaction with mentors and fellow users after some courses are completed. This is done via physical or virtual meetings with mentors and interactions with peers via a discussion forum. Both the mentors and mentee are provided guides on their responsibilities during the mentoring process.

- Present some scenarios, case studies,and mock projects after completing all courses and meeting with a mentor at least twice to evaluate the progress made by the users — what they have learned and gaps they have filled.

- A reward based on completion, performance, and skill mastery (Golden, Silver or Bronze Badge was used as rewards for performance in assessment after they have completed the courses). This can be shared on social media if they choose to.

- Offer of continuous coaching and mentoring for interviews and on the job by myself and other experienced IDs.

3.2.4. Develop

4.0 Overall Assessment

4.1. Strengths

4.2. Limits

4.3. Suggestions for Improving Future Design

- Conduct a broader needs assessment to determine the specific needs and interests of learners before designing the system.

- Integrate all the components of the system into one.

- Improve the motivation affordances of the system.

- Provide more opportunities for learners to collaborate and learn from one another, either through online discussion forums, group projects, or peer mentoring.

- Develop offline materials, such as printed manuals or guides, to cater to learners who may not have access to technology or the Internet.

- Increase practice to ensure learners are equipped with both practical experience and theoretical knowledge.

- Conduct regular evaluations of the system to identify areas for improvement, by considering learners’ feedback and needs.

5.0 Conclusion

References

- Abuhassna, H.; Alnawajha, S. Instructional design made easy! Instructional design models, categories, frameworks, educational context, and recommendations for future work. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education 2023, 13, 715–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aljohani, O.H.; Alajlan, S.M. Motivating adult learners to learn at adult-education schools in Saudi Arabia. Adult Learning 2020, 31, 150–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumeister, R.F. Toward a general theory of motivation: Problems, challenges, opportunities, and the big picture. Motivation and Emotion 2016, 40, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, J.M. Making use: Scenario-based design of human-computer interactions; MIT Press: location, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- DeMaria, A.N. Mentorship. Journal of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography 2020, 14, 451–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eby, L.T.; Allen, T.D.; Evans, S.C.; Ng, T.; DuBois, D.L. Does mentoring matter? A multidisciplinary meta-analysis comparing mentored and non-mentored individuals. Journal of Vocational Behavior 2013, 83, 106–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evolving Educators. Teachers vs Instructional Designer. 2014. Available online: https://evolvingeducator.wordpress.com/2014/07/21/teacher-vs-instructional-designer/#:~:text=Three%20major%20differences%20between%20a,%2C%20podcasting%2C%20and%20interactive%20media (accessed on 1 May 2024).

- Gee, J.P. Learning and games. In The ecology of games: Connecting youth, games, and learning; Salen, K., Ed.; Massachusetts Institute of Technology Press: location, 2008; pp. 21–40. [Google Scholar]

- Hobson, L. So you want to become an Instructional Designer. DrLukeHobson.com. Retrieved September 14 2023, 2024. Available online: https://drlukehobson.com/blog1/so-you-want-to-become-an-instructional-designer (accessed on 1 May 2024).

- Lepper, M.R.; Henderlong, J. Turning “play” into “work” and “work” into “play”: 25 years of research on intrinsic versus extrinsic motivation. In Intrinsic and extrinsic motivation: The search for optimal motivation and performance; Sansone, C., Harackiewicz, J.M., Eds.; Academic Press, Inc.: San Diego, CA, USA, 2000; pp. 257–307. [Google Scholar]

- Merrill, M.D. First principles of instruction. Educational Technology Research and Development 2002, 50, 43–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, H. (2018 – 2022). Personal Instructional Design Mentoring Experience. Unpublished.

- North, C. North, C. (2021). Fake Instructional Design Academy. Available online: https://www.linkedin.com/feed/update/urn:li:activity:6881591025048129536?updateEntityUrn=urn%3Ali%3Afs_feedUpdate%3A%28V2%2Curn%3Ali%3Aactivity%3A6881591025048129536%29 (accessed on 1 May 2024).

- Norman, D.A. (2013). The design of everyday things (Revised and expanded ed.). Basic Books.

- Peck, D. (2024). From teacher to Instructional Designer: A guide to career transition. Devlin Peck. Available online: https://www.devlinpeck.com/content/teacher-to-instructional-designer (accessed on 1 May 2024).

- Peck, D. (2024). The top 15 instructional design skills you need in 2024. Devlin Peck. Available online: https://www.devlinpeck.com/content/instructional-design-skills (accessed on 1 May 2024).

- Reiser, R.A. A history of instructional design and technology: Part I: A history of instructional media. Educational Technology Research and Development 2001, 49, 53–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reiser, R.A.; Dempsey, J.V. Trends and issues in instructional design and technology, 4th ed.; Pearson: location, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. American Psychologist 2000, 55, 68–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, P.L.; Ragan, T.J. Instructional design, 3rd ed.; Wiley: location, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Yeager, D.S.; Dweck, C.S. What can be learned from growth mindset controversies? American Psychologist 2020, 75, 1269–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).