Friendship Through a Narcissistic Lens: The Role of Narcissism in Perceived Humor Similarity Among Friends in Germany and the US

Human social relationships have long been recognized as a cornerstone of both individual well-being and societal cohesion, fundamental in shaping emotional, cognitive, and behavioral outcomes. Research has consistently underscored the idea that strong social connections are linked to a plethora of positive outcomes, including enhanced mental health, increased life satisfaction, and greater resilience against stress and adversity (Baumeister & Leary, 1995). Conversely, social isolation and poor-quality relationships are often associated with both psychological and physical health issues, clearly highlighting the profound impact of social networks on overall health (Holt-Lunstad et al., 2015).

Social relationships encompass a broad spectrum of connections, including professional associations, familial ties, romantic partnerships, and the frequently overlooked realm of platonic friendships. Although often perceived as less prominent than family or romantic bonds, platonic friendships are instrumental in numerous relational and individual outcomes. These relationships serve as vital sources of emotional support, avenues for personal growth, and significant contributors to life satisfaction (Antonucci et al., 2001; Baumeister & Leary, 1995). Recent research has increasingly highlighted the profound impact of platonic friendships on individual well-being. These studies have revealed that healthy and supportive friendships not only provide substantial positive affect but also play a crucial role in buffering against negative emotions and stressors (Argyle, 2001; Burger & Milardo, 2016; Cohen & Wills, 1985).

Friendships offer unique benefits that are distinct from other types of social relationships. Unlike familial ties, which are often obligatory, or romantic relationships, which may carry intense emotional expectations, platonic friendships typically arise from mutual interests and voluntary interactions, thus fostering a sense of freedom and acceptance. The voluntary nature of friendships allows for genuine emotional connections and a reliable source of social support that may be unique among different kinds of social relationships (Demir & Davidson, 2012). Research has suggested that friends often provide a context for individuals to engage in intimate self-disclosure, develop important social skills, and experience valuable companionship, all of which contribute to a more nuanced sense of self and a greater capacity to cope with life's challenges (Hartup & Stevens, 2016). Furthermore, friendships are essential in various life stages, from childhood through adulthood, as they support developmental processes such as identity formation in adolescence and provide continuity and stability in older adulthood (Parker & Asher, 1993).

Healthy friendships are an integral part of people’s everyday lives and often serve to facilitate desirable outcomes such as health and happiness (DeScioli et al., 2011). Recent research has found that people will choose to voluntarily spend significant amounts of free time with their friends, although this tendency often peaks in adolescence and declines in adulthood, likely because of the increasing importance of other relationships and responsibilities (Larson & Bradney, 1988).

A number of factors may impact the overall health and functioning of a friendship, but several recent studies have suggested that perceived similarity may be one particular feature that influences friendship perceptions, such as the likelihood of initiating or maintaining a friendship (Izard, 1960; Selfhout et al., 2009). Although researchers have continued to examine the extent to which similarity may matter in friendships, less attention has been given to the factors that will potentially impact these perceptions of similarity. Thus, although research may suggest that two friends believe they are similar in some category, exactly why they think they are similar has yet to be adequately examined. One such factor that may impact how likely someone is to view their friends as similar or dissimilar to themselves is their individual personality, specifically traits that shape interpersonal perception, such as the narcissistic personality traits.

The Construct of Narcissism

Narcissism may present with a variety of expressions, but the core of narcissism is typically characterized by an inflated sense of grandiosity, vanity, self-absorption, and entitlement (Morf & Rhodewalt, 2001). These clusters of traits are thought to be closely linked to the individual’s efforts to sustain a grandiose self-image through a complex interplay of internal mechanisms (e.g., maintaining positive illusions about one's abilities) and external behaviors (e.g., a propensity to demean others; Morf & Rhodewalt, 2001). Essentially, narcissistic individuals believe that they are more special than other people, but the strategies that they employ to verify their specialness may differ greatly depending on the individual and their particular cluster or expression of personality traits. Generally, the modern research literature has recognized at least two forms of narcissism: grandiose narcissism and vulnerable narcissism.

Grandiose narcissism is typically thought to be characterized by more overt expressions of superiority, entitlement, dominance, and a lack of empathy (Miller et al., 2011). Individuals with personality traits typical of grandiose narcissism tend to exhibit high self-esteem and often seek attention and admiration from others. They also tend to overestimate their abilities and achievements and often engage in behaviors that are intended to reinforce their overly inflated self-image (Krizan & Herlache, 2018). These individuals typically present as confident and charismatic, often successfully leveraging their social skills to achieve their goal of ego validation. Grandiose narcissism is often associated with traits such as extraversion and low agreeableness (Paulhus & Williams, 2002), thus accounting for why individuals presenting with grandiose narcissism are often referred to as “disagreeable extraverts.” Their interpersonal relationships are frequently marked by manipulation and a willingness to exploit others for personal gain (Jones & Paulhus, 2014). Essentially, these individuals believe they are special, and they often try (sometimes with a surprising amount of success) to convince other people of this fact.

By contrast, vulnerable narcissism is typically thought to be marked by traits such as hypersensitivity, defensiveness, and feelings of inadequacy, despite the same underlying sense of entitlement and grandiosity (Pincus et al., 2009). Individuals with personality traits consistent with vulnerable narcissism often harbor deep-seated insecurities and are highly reactive to perceived slights or criticisms. Unlike their grandiose counterparts who may occasionally present themselves as fairly charming, individuals with vulnerable narcissistic traits may exhibit social withdrawal, anxiety, and a preoccupation with their own perceived shortcomings (Miller et al., 2011). Vulnerable narcissism is typically characterized by a tendency to oscillate between extreme feelings of grandiosity and shame, leading to low and unstable self-esteem as well as chronic self-doubt (Atlas & Them, 2008). Individuals with these traits often have social interactions characterized by a need for reassurance and validation, and they may use passive-aggressive tactics or emotional manipulation to garner sympathy and support (Cain et al., 2008). This form of narcissism is frequently associated with other undesirable personality traits, such as neuroticism and introversion (Miller et al., 2011), which are thought to reflect the more covert and fragile nature of these individuals’ overly inflated self-views. Essentially, like their grandiose counterparts, individuals with vulnerable narcissism believe they too are special, but they are often unable to convince others of this fact, and it may create a sense of internal turmoil and defensiveness.

Narcissism in Friendship Interactions and Friendship Perceptions

The clusters of personality traits associated with narcissism present intriguing implications for the dynamics and outcomes of friendships. Friendships are often rooted in perceived similarity, where individuals seek out and maintain relationships with others who share their interests, values, and attitudes (Montoya et al., 2008). However, narcissistic individuals might deviate from this pattern due to their propensity for grandiosity and self-perceived superiority (Morf & Rhodewalt, 2001). Narcissistic individuals often view themselves as exceptional and uniquely deserving of admiration, which can create an uncomfortable sense of dissonance when forming and maintaining friendships, as they may perceive others as inferior or unworthy of comparison (Campbell et al., 2002). Essentially, they may tend to seek “high value” friends because they perceive themselves to be similar in some regard, but their tendency to think of others as inferior may create a ceiling effect for their perceptions of similarity, leading to significant discomfort in their friendships or other social relationships.

This inherent sense of superiority may lead narcissistic individuals to be less inclined to acknowledge or appreciate similarities with their peers, instead focusing on how they differ or excel (Konrath et al., 2009). This tendency may manifest in a reluctance to view friends as equals, potentially resulting in a preference for relationships where they can maintain a sense of dominance, control, or superiority (Back et al., 2013). Moreover, whereas most people derive satisfaction from mutual respect and shared experiences in friendships, narcissistic individuals may instead prioritize the validation of their own self-worth over genuine connection, intimacy, or reciprocity (Miller et al., 2011). Consequently, they might seek friends who enhance their status or reinforce their self-concept, rather than those who offer genuine similarity or support (Brunell et al., 2013). This dynamic may potentially lead to several different outcomes in the context of friendships. For instance, narcissistic individuals might experience higher turnover in friendships due to the perceived inadequacies of their friends or conflicts arising from their self-centered behavior (Wright et al., 2010). Additionally, the quality of friendships involving narcissistic individuals might suffer and be characterized by less emotional intimacy and mutual support, as narcissistic individuals may struggle to engage in the intimate and vulnerable give-and-take essential for sustaining close, healthy relationships (Campbell & Foster, 2007). These patterns underscore the complexity of narcissism's impact on social relationships and highlight the potential challenges narcissistic traits pose to the development and maintenance of meaningful, long-lasting friendships.

Although narcissistic individuals may view friendships through a particular lens because of the traits associated with the core of narcissism, it is also entirely possible that different facets of narcissism may be associated with divergent and unique ways of viewing friends and friendship. Grandiose narcissists, typified by elevated self-esteem, assertiveness, and a pronounced sense of superiority, may tend to engage in friendships that are superficial and status-driven (Miller et al., 2011). These individuals often seek admiration and validation, dominate social interactions, and exhibit a lack of empathy, resulting in relationships that are shallow and frequently conflictual (Kaufman et al., 2020). Conversely, vulnerable narcissists, characterized by underlying insecurity, hypersensitivity, and defensiveness, may face challenges in building trust and intimacy within friendships (Pincus & Lukowitsky, 2010). Their tendency to oscillate between idealizing and devaluing friends creates instability and emotional volatility in their relationships (Dickinson & Pincus, 2003). Additionally, their constant need for reassurance and fear of rejection can lead to dependent or manipulative behaviors, further complicating the maintenance of stable and healthy friendships (Besser & Priel, 2010). This dichotomy underscores the necessity for nuanced approaches in studying narcissistic traits and their impact on social relationships.

Humor Styles

With this study, we aim to develop a more nuanced understanding of the complexities of perceived similarity in friendships involving narcissistic individuals by focusing on one particular category where perceptions of similarity may be particularly important in friendships: shared humor styles. Just as perceived similarity in values, interests, and personality traits often underpins the formation and quality of friendships (Altmann, 2022; Harris & Vazire, 2016), humor style similarity also plays a significant role in relational cohesion. Humor not only serves as a means of entertainment but also acts as a powerful tool for bonding and social connection (Martin et al., 2003). In friendships, similar humor styles can enhance mutual enjoyment, facilitate deeper emotional connections, and strengthen an overall sense of camaraderie (Cann & Calhoun, 2001). This alignment in humor preferences can be particularly influential in navigating social exchanges, as shared humor fosters an environment of mutual understanding and comfort, promoting positive affect and reducing interpersonal tension (Bressler & Balshine, 2006). Therefore, understanding how perceived similarity in humor styles contributes to friendship dynamics provides valuable insights into the mechanisms that underpin successful social relationships. Recognizing how individual differences, such as narcissistic traits, influence perceptions of similarity in humor styles will offer significant insights into the foundations of this complex dynamic in friendships.

Martin et al. (2003) proposed a comprehensive framework of humor styles, delineating four distinct approaches to humor that individuals may employ across different social interactions. The first style, affiliative humor, involves using humor to enhance relationships, reduce tension, and foster camaraderie through positive and inclusive jokes and anecdotes. By contrast, self-enhancing humor revolves around the ability to maintain a humorous outlook on life's challenges and setbacks, allowing individuals to maintain a resilient and optimistic perspective. The third style, aggressive humor, is characterized by a use of humor that mocks, belittles, or disparages others, often at their expense. This style serves to assert dominance or gain social status through sarcasm, teasing, or ridicule. Lastly, self-defeating humor involves humor that targets oneself with the intention to gain approval or acceptance from others, often through self-deprecation or by highlighting one’s own personal flaws. The first two types (i.e., affiliative and self-enhancing) can be summarized as adaptive types, which are typically positively correlated with constructs such as agreeableness, extraversion, well-being, and self-esteem. The last two types (i.e., aggressive and self-defeating) can be summarized as maladaptive types, which are typically negatively correlated with the same constructs but positively correlated with neuroticism and aggressiveness (Greengross et al., 2012; Martin et al., 2003). Martin et al.'s taxonomy provides a nuanced framework for understanding how humor may serve a wide variety of interpersonal functions, often influencing social dynamics, emotional expression, and relational satisfaction across different contexts and different kinds of relationships.

The Current Research

Understanding these dynamics is crucial, especially in friendships, where shared humor provides a myriad of benefits to the relationship, and friendships may therefore create a natural expectation for humor style symmetry. Individuals typically perceive their friends’ humor as similar to their own (Cann & Calhoun, 2001), fostering emotional connections and strengthening relational bonds (Bressler & Balshine, 2006). However, narcissistic individuals’ tendency to view themselves as superior and unique introduces a potential conflict in how they perceive humor similarity with their friends. Narcissistic individuals, characterized by their grandiosity and sense of entitlement, often exhibit unique patterns in evaluating and interacting with their friends, and this tendency may also apply to how they view their friends’ humor styles in relation to their own humor styles.

Narcissistic individuals may feel a need to see their friends as extensions of their own excellence and superiority (Campbell & Foster, 2007), thus evaluating their friends very positively—that is, viewing their friends as similar to themselves. However, narcissistic individuals may also experience difficulty in acknowledging similarities with their friends, especially in areas where they see themselves as exceptional, such as humor. Whereas most people are likely to rate their own humor similarly to that of their closest friends, narcissistic individuals may uniquely diverge from this pattern. They are prone to viewing themselves as superior, reflecting their need for self-enhancement and validation. Consequently, they might evaluate their friends’ humor as less sophisticated or effective compared with their own, thereby reinforcing their grandiose self-perception and entitlement (Wright et al., 2010). Essentially, narcissistic individuals may share the human tendency to perceive their friends as similar to themselves, but their need to feel superior may place a limit on this effect such that more narcissistic individuals will be less likely to rate their friends as similar to themselves in terms of humor because their inherent need to feel superior does not allow them to view their friends as similar to themselves in any capacity. Although humor typically serves as a bridge for connection and mutual enjoyment, for narcissistic individuals, it can become a tool for self-enhancement and a mechanism for maintaining perceived superiority over their friends (Back et al., 2013). The current work was intended to gain insight into this complex dynamic by investigating the relationships between narcissistic traits and perceived similarity in humor styles.

Study 1

The goal of Study 1 was to explore the effects of narcissism on perceived humor similarity in close friendship relationships. To do so, we posed four general hypotheses. First, on the basis of previous studies showing perceived similarity in personality (Lee et al., 2009; van Zalk & Denissen, 2015), we expected to find perceived similarity in all four humor styles (Hypothesis 1). Second, because narcissistic individuals see themselves as unique and may thereby report less similarity between themselves and their friends as the strength of their narcissistic traits increases, we expected this perceived similarity to depend on the individual’s level of narcissism (Hypothesis 2). Third, we expected grandiose narcissism to be associated with a self-enhanced and therefore higher evaluation of one’s own adaptive (i.e., affiliative and self-enhancing) humor styles compared with one’s evaluation of the same humor styles in a close friend (Hypothesis 3). Fourth, vulnerable narcissism can be expected to use the same mechanism of assumed uniqueness but in a maladaptive fashion. Thus, we expected vulnerable narcissism to be associated with a higher evaluation of one’s own maladaptive (i.e., aggressive and self-defeating) humor styles compared with one’s evaluation of the same humor styles in a close friend (Hypothesis 4).

Method

Sample and Procedure

Participants were invited to take part in the study using flyers, email-forwarding, and social media posts. The invitations included a URL to the online assessment tool (Unipark) where the study was hosted. As a reward for their participation, participants either took part in a lottery or received partial course credit if applicable.

A sample size of at least N = 108 was identified as necessary to detect a small to medium moderating effect (R2 increase) of .10, given a power of .90 and an alpha of .05, calculated with G*Power 3.1 (Faul et al., 2009). The final sample comprised 129 participants (69% women). The mean age was 36.3 years (SD = 15.4). Level of education was based on the German schooling system: 5% reported basic education (10 years), 76% reported further education (12 years), and 19% reported an academic degree.

Upon accessing the online study, participants gave informed consent, provided their sociodemographic data, and completed the two narcissism questionnaires and the self-report humor styles questionnaire described below. They were then instructed to think of one of their best same-sex friends and to provide this person’s given name, initials, nickname, or something similar, which was used in the subsequent friend-report version of the humor styles. The data are available at

https://osf.io/9tn35/?view_only=78313346eed14c63b1aa862d8539b9d7.

Measures

Grandiose Narcissism. Grandiose narcissism was measured with the 13-item brief version (Gentile et al., 2013) of the Narcissistic Personality Inventory (NPI; Raskin & Hall, 1979). The German version was taken from Brailovskaia, Bierhoff, et al. (2019). The NPI uses a forced-choice format in which participants select the statement that describes them best (out of two). For instance, participants are asked to choose between Statement A “I insist upon getting the respect that is due me” and Statement B “I usually get the respect that I deserve.” Cronbach’s alpha was .50, which is not uncommon (Brailovskaia, Teismann, et al., 2019) and still acceptable given its sufficient temporal stability (Brailovskaia, Bierhoff, et al., 2019) especially when using group statistics (Gosling et al., 2003; Ziegler et al., 2014).

Vulnerable Narcissism. The 10-item Hypersensitive Narcissism Scale (HSNS; Hendin & Cheek, 1997) was used to measure vulnerable narcissism. The German translation was taken from Jauk et al. (2017). A sample item reads “My feelings are easily hurt by ridicule or the slighting remarks of others.” We used a 5-point scale ranging from 1 (does not apply to me) to 5 (applies to me). Cronbach’s alpha was .71.

Humor Styles – Self-Report. We used the 12-item brief version (Altmann, 2024a) of the Humor Styles Questionnaire (HSQ; Martin et al., 2003). The German translation was taken from Ruch and Heintz (2016). The HSQ assesses four styles of humor: affiliative (e.g., “I usually don't like to tell jokes or amuse people,” reverse scored), self-enhancing (e.g., “If I am feeling depressed, I can usually cheer myself up with humor”), aggressive (e.g., “If someone makes a mistake, I will often tease them about it”), and self-defeating humor (e.g., “Letting others laugh at me is my way of keeping my friends and family in good spirits”). We used a 5-point scale ranging from 1 (does not apply to me) to 5 (applies to me). Cronbach’s alphas were .61, 70, .62, and 78, respectively.

Humor Styles – Friend-Report. The HSQ was also administered in a friend-report version (i.e., a report about the friend the participant chose at the beginning of the study). For the friend reports, the instructions and items of the inventory were adjusted to include the name of the friend as provided by the participant at the beginning. For instance, if the participant provided “Peter” as the friend’s name, the self-report item “I usually don't laugh or joke around much with other people” was changed to “Peter usually doesn't laugh or joke around much with other people.” We used a 5-point scale ranging from 1 (does not apply) to 5 (does apply). Cronbach’s alphas were .62, .68, 75, and .77.

Results

Preliminary Analyses

Table 1 presents descriptive statistics and bivariate correlations. Grandiose and vulnerable narcissism were found to be unrelated (

r = -.02,

p = .823), which is in line with the initial conceptualization of grandiose and vulnerable narcissism as orthogonal dimensions (Wink, 1991). Regarding the links between narcissism and humor styles, previous research was inconsistent (Altmann, 2024b). In the present study, grandiose narcissism was positively related to both affiliative (

r = .27,

p = .002) and aggressive humor (

r = .30,

p < .001). These findings are in line with studies by Besser and Zeigler-Hill (2011) and Lobbestael and Freund (2021) in again showing the seemingly contradictory behavioral expressions of grandiose narcissism being positively related to both adaptive and maladaptive humor alike (Altmann, 2024b). Vulnerable narcissism was negatively related to the self-enhancing humor style (

r = -.23,

p = .008) and positively related to the self-defeating humor style (

r = .36,

p < .001), thus supporting previous findings reported by Altmann (2024b) and Hollandsworth (2019). Regarding narcissism’s relationship with participants’ perceptions of a best friend’s humor (i.e., friend-reports of humor styles), grandiose narcissism was positively related to the aggressive (

r = .22,

p = .014) and self-defeating humor styles (

r = .21,

p = .019) and thus related to both maladaptive humor styles. Vulnerable narcissism was unrelated to friend-reports of humor.

Main Analyses

Partial support was found for Hypothesis 1 (perceived similarity in the four humor styles). As

Table 1 shows, self-reports of humor styles were positively correlated with the respective friend-reports for the self-enhancing (

r = .30,

p < .001), aggressive (

r = .59,

p < .001), and self-defeating humor styles (

r = .33,

p < .001) but not the affiliative (

r = .14,

p = .127). Interestingly, perceived similarity was highest for the aggressive style and was significantly higher (

z = 2.658,

p = .008) than for the self-defeating style (which had the second-largest correlation).

To test Hypothesis 2 (lower perceived similarity with higher levels of narcissism), we examined the effects of the interactions between self-reports of the four humor styles and (grandiose and vulnerable) narcissism on friend-reports of these humor styles. The PROCESS macro by Hayes (2022) Model 1 was used for the calculations.

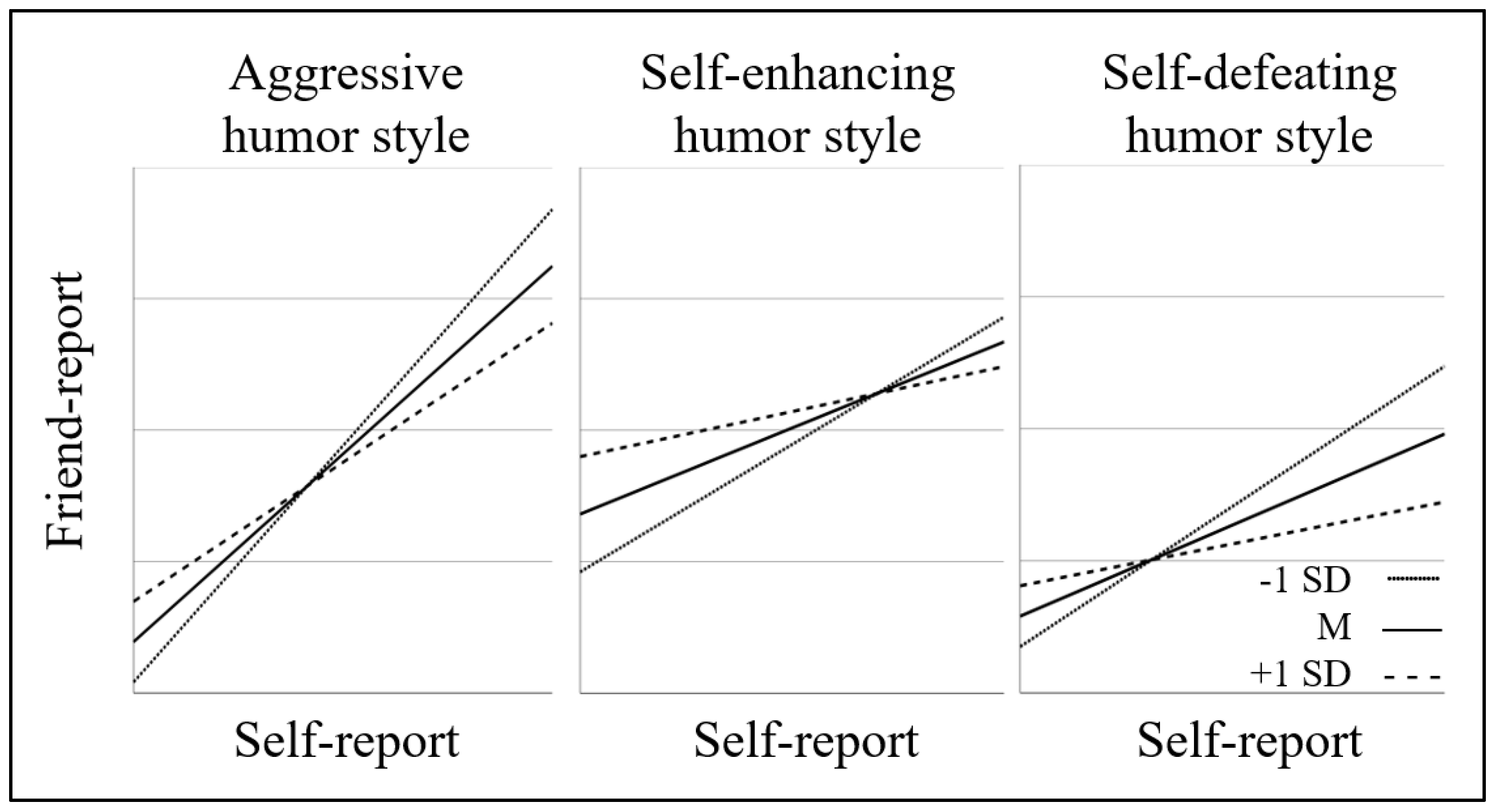

Table 2 and

Table 3 show that, for grandiose narcissism, only the interaction involving the aggressive humor style was significant. For vulnerable narcissism, the interaction involving self-enhancing humor just missed being significant (

p = .065) and the interaction involving self-defeating humor was significant. The negative effect sizes in all three cases indicated that narcissism weakened the relationship between self-reports and friend-reports (i.e., perceived similarity).

For the three effects mentioned above, we conducted subsequent analyses of the conditional effects of the predictor at different values of the moderator (see

Table 4). These effects consistently showed that the relationships between self-reports and friend-reports of humor styles were highest at low levels of narcissism. Stated another way, higher narcissism is related to a greater tendency to assume that the other person is different from oneself. As mentioned above, this finding held for grandiose narcissism for the aggressive humor style and for vulnerable narcissism for the self-enhancing and self-defeating humor styles.

Figure 1 depicts these conditional effects.

For Hypotheses 3 and 4, we expected that people in general would not rate themselves on the four humor styles as higher or lower than their best friends but that people high in narcissism would systematically rate their best friends as different from themselves to express their uniqueness. Thus, for Hypothesis 3, we expected to find higher mean levels for the self-reports than for the friend-reports regarding adaptive (i.e., affiliative and self-enhancing) humor styles in people high in grandiose narcissism but not in people low in grandiose narcissism (effect of the interaction between humor style self-reports and grandiose narcissism on humor style friend-reports).

As a preliminary finding, we calculated paired t tests comparing mean levels of self-reports with friend-reports for each of the four humor styles. Findings only partially supported our general hypothesis because the self-enhancing and aggressive humor styles did not show any mean differences, t(128) < 0.05, p > .957. However, against our expectations, we found mean differences for both the affiliative and self-defeating humor styles, t(128) > 2.68, p < .008, d = 0.24/0.31.

To be able to test Hypothesis 3, we first split the sample into participants with low and high grandiose narcissism (with 64 and 65 participants, respectively) using the median grandiose narcissism score from the NPI (see

Table 5 for mean scores). We calculated repeated-measures ANOVAs using self-reports and friend-reports as repeated measurements and the median split variable as the between-subjects factor. Regarding the affiliative humor style, we found main effects of the within-subjects factor (self- vs. friend-report;

F(1, 127) = 7.30,

p = .008) and the between-subjects factor (low vs. high grandiose narcissism;

F(1, 127) = 5.52,

p = .020). We found the hypothesized interaction too,

F(1, 127) = 4.38,

p = .038, η

2 = .03. Post hoc tests confirmed that self-reports were larger than friend-reports in the high-narcissism group (Δ

M = 0.45,

SE = 0.13,

p = .001), but the two were not significantly different in the low-narcissism group (Δ

M = 0.06,

SE = 0.13,

p = .669). Regarding the self-enhancing humor style, there was no significant interaction effect,

F(1, 127) = 2.51,

p = .116.

For Hypothesis 4, we expected to find higher mean levels for self-reports than for friend-reports for maladaptive (i.e., aggressive and self-defeating) humor styles in people high in vulnerable narcissism but not in people low in vulnerable narcissism (effect of the interaction between humor style self-reports and vulnerable narcissism on humor style friend-reports). We used the same median split procedure used for vulnerable narcissism (with 64 and 65 participants in the low and high groups, respectively; see

Table 5 for mean scores). For the aggressive humor style, there was no significant interaction,

F(1, 127) = 0.12,

p = .727. However, for the self-defeating humor style, main effects were found for the within-subjects factor (self- vs. friend-report),

F(1, 127) = 13.05,

p < .001, and the between-subjects factor (low vs. high vulnerable narcissism),

F(1, 127) = 7.47,

p = .007. The hypothesized interaction was found as well,

F(1, 127) = 5.56,

p = .020, η

2 = .04. Post hoc tests confirmed that the means were higher for self-reports than friend-reports in the high-narcissism group (Δ

M = 0.60,

SE = 0.14,

p < .001) and did not differ significantly in the low-narcissism group (Δ

M = 0.13,

SE = 0.14,

p = .379).

Discussion

The correlational findings replicated previous studies in showing that grandiose narcissism was positively related to both the affiliative and aggressive humor styles. Vulnerable narcissism was negatively related to the self-enhancing humor style but positively related to the self-defeating humor style. These findings are in line with the theoretical conceptualizations of grandiose and vulnerable narcissism (Krizan & Herlache, 2018; Wink, 1991) and previous studies (Altmann, 2024b; Besser & Zeigler-Hill, 2011; Hollandsworth, 2019). Our findings indicate that higher narcissism is associated with a greater tendency to devaluate close friends as shown by the positive associations with friend-reports for the aggressive and self-defeating humor styles. Essentially, individuals high in grandiose narcissism tended to report that their friends had maladaptive humor styles.

The results partially supported our hypotheses. For Hypothesis 1, evidence of perceived similarity was found for all styles except the affiliative humor style. The affiliative style has typically been rated highest by participants in previous studies, suggesting that most people describe themselves as having affiliative humor. The large endorsement of this humor style across different types of people may explain the small correlation coefficient. By contrast, the aggressive humor style showed particularly low mean scores but the highest level of perceived similarity.

For Hypothesis 2, we found that higher narcissism was related to a greater tendency to assume that the other person is different from oneself. This finding is in line with previous conceptualizations of narcissism that suggest that striving for uniqueness may be a central aspect of narcissism in social relationships (Back et al., 2013; Krizan & Herlache, 2018). This relationship was found for three out of four expected effects: for grandiose narcissism regarding the aggressive humor style and for vulnerable narcissism regarding the self-enhancing and self-defeating humor styles. To better understand these effects, we tested for mean differences with Hypotheses 3 and 4. As expected, we found that people high in grandiose narcissism tended to rate their own affiliative humor higher than their close friends’, but people low in narcissism did not. Similarly, we found that people high in vulnerable narcissism tended to rate their own self-defeating humor higher than their close friends’, but people low in narcissism did not. However, these effects were not found for self-enhancing and aggressive humor. In sum, we found evidence that specific facets of narcissism uniquely moderated perceived similarity of humor styles in the context of friendship.

Study 2

For Study 2, the design and methodology were the same as in Study 1, but the sample was different. Study 1 was conducted in Germany, which may be described as a western, educated, industrialized, rich, and democratic (WEIRD) country (Henrich et al., 2010). To gain a more generalizable understanding of the results of Study 1, we used a U.S. sample in Study 2. Although both countries may be considered WEIRD, we were interested in whether the results would differ as a result of language and cultural differences. We used the same hypotheses as in Study 1 and preregistered the hypotheses and analysis plan prior to data assessment (

https://osf.io/9tn35/?view_only=78313346eed14c63b1aa862d8539b9d7).

Method

Sample and Procedure

We used the same recruitment process and study procedure as in Study 1. Participants were invited to take part in the study via flyers, email-forwarding, and social media posts. The invitations included a URL to the online assessment tool Unipark where the study was hosted. As a reward for participating, student participants received partial course credit. The final sample comprised 131 participants (35% women). Their mean age was 19.5 years (

SD = 1.5). The data are available at

https://osf.io/9tn35/?view_only=78313346eed14c63b1aa862d8539b9d7.

Measures

We administered the same inventories as in Study 1 but in their original English versions. The 13-item brief version (Gentile et al., 2013) of the Narcissistic Personality Inventory (NPI; Raskin & Hall, 1979) was used to measure grandiose narcissism (Cronbach’s α = .61). The Hypersensitive Narcissism Scale (HSNS; Hendin & Cheek, 1997) was used to measure vulnerable narcissism (α = .61). The 12-item brief version (Altmann, 2024a) of the Humor Styles Questionnaire (HSQ; Martin et al., 2003) was used to measure humor styles (self-reports: .71 < α < .76; friend-reports: .65 < α < .70; the only exception was the self-reported aggressive humor style: α = .48). As discussed above, such a low alpha may be tolerable when calculating group statistics (Gosling et al., 2003; Ziegler et al., 2014), but the results based on it need to be treated with caution.

Results

Preliminary Analyses

Table 6 presents descriptive statistics and bivariate correlations. Grandiose and vulnerable narcissism were positively correlated (

r = .20,

p = .020). Regarding the links between narcissism and humor styles, only vulnerable narcissism and the self-defeating humor style were correlated (

r = .31,

p < .001). Regarding how narcissism is related to the perceptions of a best friend’s humor styles (i.e., friend-reports of humor styles), only grandiose narcissism was negatively related to the self-enhancing style (

r = -.20,

p = .022) and positively related to the aggressive style (

r = .17,

p = .047).

Main Analyses

Partial support was found for Hypothesis 1 (perceived similarity in the four humor styles). As

Table 6 shows, self-reports of humor styles were positively correlated with the respective friend-reports only for the affiliative (

r = .29,

p < .001) and aggressive humor styles (

r = .62,

p < .001). As in Study 1, perceived similarity was highest for the aggressive style and significantly higher (

z = -3.41,

p < .001) than for the affiliative style.

To test Hypothesis 2 (perceived similarity is lower with higher levels of narcissism), we conducted a set of moderator analyses to examine the effects of the interactions between self-reports of the four humor styles and (grandiose and vulnerable) narcissism on friend-reports of these humor styles. The PROCESS macro by Hayes (2022) Model 1 was used for the calculations. As shown in

Table 7 and

Table 8, the only interaction that was found was for the self-enhancing humor style moderated by vulnerable narcissism. The negative effect sizes indicate that narcissism weakened the relationship between self-reports and friend-reports: Essentially, individuals with stronger narcissistic traits tended to rate their friends as less similar to themselves. We conducted a subsequent analysis of the conditional effects of the predictor at different values of the moderator (see

Table 9). It showed that the relationship between self-reports and friend-reports of humor styles was highest at low levels of narcissism.

With Hypothesis 3, we expected to find larger mean levels for self-reports than friend-reports for the adaptive humor styles (i.e., affiliative and self-enhancing) in people high in grandiose narcissism but not in people low in grandiose narcissism. Preliminary paired t tests comparing mean levels of self-reports with friend-reports for each of the four humor styles did not show mean differences in the affiliative and self-enhancing humor styles, t(130) < 1.45, p > .151. However, differences were found for the aggressive and self-defeating humor styles, t(130) > 2.49, p = .014, d = -0.24/0.22, indicating that participants gave lower ratings for their own aggressive humor style than for their friends’ and higher ratings for their own self-defeating humor style than for their friends’.

As in Study 1, we split the sample into participants with low and high grandiose narcissism scores (with 65 and 66 participants, respectively) using the median of the NPI (see

Table 10 for descriptive statistics). We conducted repeated-measures ANOVAs using self-reports and friend-reports as repeated measurements and the median split variable as the between-subjects factor. For the affiliative humor style, no main effects were found for the within-subjects factor (self- vs. friend-report),

F(1, 129) = 0.04,

p = .840, or the between-subjects factor (low vs. high grandiose narcissism),

F(1, 129) = .41,

p = .524. However, the hypothesized interaction was found,

F(1, 129) = 7.46,

p = .007, η

2 = .06. Post hoc tests showed that self-reports were larger than friend-reports in the high-narcissism group but just failed to reach significance (Δ

M = 0.18,

SE = 0.10,

p = .075), and friend-reports were larger than self-reports in the low-narcissism group (Δ

M = 0.21,

SE = 0.10,

p < .041). Regarding the self-enhancing humor style, there was no significant interaction effect,

F(1, 129) = 1.99,

p = .161.

With Hypothesis 4, we expected to find larger mean levels for self-reports than friend-reports for the maladaptive humor styles (i.e., aggressive and self-defeating) in people high in vulnerable narcissism but not in people low in vulnerable narcissism. We used the same median split procedure as used before (with 65 and 66 participants in the low and high groups, respectively; see

Table 10 for descriptive statistics). For the aggressive humor style, a main effect was found for the within-subjects factor,

F(1, 129) = 7.84,

p = .006, but not the between-subjects factor,

F(1, 129) = 0.02,

p = .882. We found the hypothesized interaction,

F(1, 129) = 3.96,

p = .049, η

2 = .03. Post hoc tests showed that self-reports and friend-reports did not differ in the high-narcissism group (Δ

M = 0.06,

SE = 0.10,

p < .566), but friend-reports were larger than self-reports in the low-narcissism group (Δ

M = 0.33,

SE = 0.10,

p = .001). For the self-defeating humor style, main effects were found for the within-subjects factor,

F(1, 129) = 6.41,

p < .013, and the between-subjects factor,

F(1, 129) = 5.77,

p = .018. The hypothesized interaction was found as well,

F(1, 129) = 6.67,

p = .011, η

2 = .05. Post hoc tests confirmed that self-reports were larger than friend-reports in the high-narcissism group (Δ

M = 0.52,

SE = 0.14,

p < .001) and were not significantly different in the low-narcissism group (Δ

M = 0.01,

SE = 0.14,

p = .972).

Discussion

For Hypothesis 1, we found evidence of perceived similarity only for the affiliative and aggressive humor styles. This finding contrasts with Study 1, which found perceived similarity in all but the affiliative style. For Hypothesis 2, we found that the self-enhancing humor style was negatively moderated by vulnerable narcissism, indicating that narcissism weakens relationships between self-reports and friend-reports, thus suggesting lower rates of perceived similarity. Essentially, higher vulnerable narcissism is related to a greater tendency to assume that the other person is different from oneself in self-enhancing humor.

For Hypotheses 3 and 4, we found tendential support for the assumption that people high in grandiose narcissism rate themselves as possessing higher levels of affiliative humor compared with their close friends. A similar pattern was also found for the aggressive humor style. In addition, the expected effect was also found in people scoring higher in vulnerable narcissism, who gave higher ratings to their own use of self-defeating humor than their close friends’, but people low in vulnerable narcissism did not. These findings further substantiate the concept that people high in narcissism seek to express their uniqueness (Back et al., 2013; Krizan & Herlache, 2018) even if it means devaluing their close friends in the case of grandiose narcissism or devaluing themselves in the case of vulnerable narcissism.

General Discussion

Previous research has found that individuals tend to perceive their friends’ personalities as similar to themselves in a variety of domains (Lee et al., 2009; van Zalk & Denissen, 2015). In this study, we investigated whether individuals high in narcissism may deviate from this general pattern because of their desire to see and present themselves as unique (Krizan & Herlache, 2018; Miller et al., 2011). Essentially, we wanted to explore whether narcissistic individuals were less likely to rate their friends as similar to themselves with the hypothesis being that perceived similarity would be incompatible with perceived uniqueness, which is consistent with previous research concerning the nature and expression of narcissism (Campbell et al., 2002; Morf & Rhodewalt, 2001). We tested this premise in two countries (Germany and the US), an approach that allowed us to identify and distinguish universal and culture-specific effects and also increases the study’s generalizability by ensuring that the replicated findings are robust and are not artifacts of a particular sample or setting.

Narcissism Affects Perceived Similarity

The results partially supported our hypotheses and underlying assumptions. Higher narcissism was related to a greater tendency to assume that the other person is different from oneself. However, unique patterns of association did emerge for each facet of narcissism and the different humor styles, and differences between the two samples were also apparent.

In our German sample, perceived similarity in the aggressive humor style was lower for grandiose narcissism, and perceived similarity in the self-enhancing and the self-defeating humor styles was lower for vulnerable narcissism. In comparison, in the U.S. sample, only perceived similarity in the self-enhancing humor style was lower for vulnerable narcissism. However, despite these differences, the Study 2 results largely replicated the Study 1 results.

Specifically, in both samples, we found that individuals high in grandiose narcissism tended to rate their friends as showing less affiliative humor compared with themselves, and individuals high in vulnerable narcissism tended to rate their friends as showing less self-defeating humor compared with themselves. The affiliative humor style is generally seen as an adaptive and desirable style, whereas the self-defeating humor style is generally seen as a maladaptive and less desirable style (Greengross et al., 2012; Martin et al., 2003), suggesting that these unique associations with particular humor styles may suggest that grandiose narcissism is related to a tendency to engage in self-enhancement and other-devaluation, but vulnerable narcissism is related to a tendency to engage in self-devaluation and other-enhancement (Altmann, 2024b; Besser & Zeigler-Hill, 2011; Lobbestael & Freund, 2021). These findings are in line with previous work on the general relationships between narcissism and humor (Altmann, 2024b; Besser & Zeigler-Hill, 2011; Hollandsworth, 2019) as well as the distinction between grandiose and vulnerable narcissism and their relationships with interpersonal behavior and perception (Krizan & Herlache, 2018; Miller et al., 2011; Wink, 1991).

We interpret the present findings as indicative of how individuals high in narcissism perceive their friends’ humor styles. However, we cannot rule out the possibility that individuals high in narcissism are, for a number of possible reasons, actually friends with individuals who tend to have higher or lower levels of certain types of the humor styles. Data from friendship dyads would be needed to control for the actual traits (Körner & Altmann, 2023), but it is entirely possible that narcissistic individuals attract or are attracted to individuals with certain humor styles.

Narcissism in Social Interactions

The current work provides significant insights into how narcissism influences perceptions of humor similarity in the context of platonic friendships, revealing nuanced differences that appear to be linked to the type of narcissism. Specifically, individuals with high levels of grandiose narcissism tend to devalue their friends' humor, suggesting a dismissive attitude toward traits they perceive as inferior or different from their own. This behavior and perspective is aligned with these individual’s overarching need for admiration, superiority, and a sense of uniqueness (Back et al., 2013; Krizan & Herlache, 2018). By downplaying their friends' humor, particularly their friends’ desirable or adaptive humor, these individuals reinforce their self-image as the central figure in their social circle, minimizing any qualities that could threaten their perceived dominance or special position.

Conversely, individuals with high levels of vulnerable narcissism exhibit a contrasting pattern by enhancing their friends' humor relative to their own. This tendency may stem from their internal struggles with self-esteem and anxiety (Jauk et al., 2017; Miller et al., 2011; Wink, 1991). Vulnerable narcissists might overcompensate by idealizing their friends’ humor, possibly to bolster their sense of security and social acceptance. This behavior underscores a fundamental aspect of vulnerable narcissism: the deep-seated need for reassurance and validation, which may drive them to elevate the perceived value of those around them (Back et al., 2013; Morf & Rhodewalt, 2001), even if it means distorting their own self-assessment. Additionally, it is possible that individuals with elevated levels of vulnerable narcissism may overly inflate their friends’ value in an effort to make themselves also seem or feel more valuable.

Overall, narcissistic individuals, regardless of the particular facet of narcissism, tend to perceive their friends as less similar to themselves in humor styles but through different lenses. These findings highlight a critical dynamic in friendships: Narcissism not only alters the way individuals see themselves but also fundamentally shapes their social interactions and relationships (Dehaghi & Zeigler-Hill, 2021; Sauls & Zeigler-Hill, 2020; Sauls et al., 2019). For grandiose narcissists, this phenomenon manifests in a tendency to isolate or belittle friends who do not match their idealized self-image, potentially straining social bonds. By contrast, vulnerable narcissists may cultivate relationships in which they are overly dependent on the approval and validation of others, potentially leading to unbalanced or superficial connections.

These dynamics underscore the complex interplay between narcissistic traits and social perception, suggesting that narcissism can significantly impact the quality and nature of interpersonal relationships. Understanding these patterns is crucial for developing strategies to support individuals with narcissistic tendencies in fostering healthier, more balanced friendships. Future research could further explore the mechanisms behind these behaviors and their long-term effects on social functioning, offering valuable insights for both psychological theory and practical interventions in the realm of social relationships and mental health.

Limitations

Although the present research has a number of strengths (e.g., a multifaceted conceptualization of narcissism, samples from multiple cultures), it has some limitations that need to be mentioned. First, we instructed our participants to think of one best same-sex friend. This approach limits the generalizability of the present findings because same-sex friendships differ from cross-sex friendships (Altmann, 2021; O'Meara, 1989) and thus need to be tested separately. In addition, we did not differentiate our samples into women and men because doing so would have left our study underpowered. However, differentiating between women and men may be a fruitful approach in future studies (Altmann, 2020).

Second, the two samples in our study from Germany and the US were not perfectly comparable in several respects. The gender composition differed, and the mean age was lower in the U.S. sample. A younger sample may be associated with different kinds of friendships, as the majority of younger participants’ friends are likely classmates from school. This restrained setting may cause young adults to become friends by chance simply because they were placed next to each other in classrooms (Back et al., 2008), creating the possibility that these friendships may differ in some way from friendships formed elsewhere. By contrast, older students may have found new friends on a university campus, which offers more options and thus a higher chance of finding a person with similar personality traits and use of humor.

Third, the use of self-reports may introduce biases. They typically show socially desirable response patterns, which may reduce variability, compromise validity, and potentially even differ between countries. In addition, using self-reports and friend-reports made by the same person does not allow for a distinction between perception and selection.

Conclusion

The current work found that individuals generally tend to view their friends as similar to themselves in terms of humor styles. As expected, this association was affected by narcissism such that higher levels of narcissism were associated with lower levels of perceived similarity. Specifically, individuals high in grandiose narcissism tended to devalue their close friends’ humor, and individuals high in vulnerable narcissism tended to enhance their friends’ humor compared with themselves. These findings suggest that narcissistic individuals view their friends through a particular lens related to their need to feel unique.

Funding

There was no funding for this research.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- Altmann, T. (2020). Distinctions in friendship research: Variations in the relations between friendship and the big five. Personality and Individual Differences, 154. [CrossRef]

- Altmann, T. (2021). Avoiding cross-sex friendships: The separability of people with and without cross-sex friends. Current Psychology. [CrossRef]

- Altmann, T. (2022). Sex differences partially moderate the relationships between personal values and the preference for cross-sex friendships (heterosociality). Journal of Individual Differences. [CrossRef]

- Altmann, T. (2024a). Development and validation of three brief versions of the humor styles questionnaire. Acta Psychologica, 243, 104141. [CrossRef]

- Altmann, T. (2024b). The narcissist’s sense of humor: A correlational and an experimental ego threat study on the links between narcissism and adaptive and maladaptive styles of humor. Current Psychology. [CrossRef]

- Antonucci, T. C., Lansford, J. E., & Akiyama, H. (2001). Impact of positive and negative aspects of marital relationships and friendships on well-being of older adults. Applied Developmental Science, 5(2), 68-75. [CrossRef]

- Argyle, M. (2001). The psychology of happiness. Routledge.

- Atlas, G. D., & Them, M. A. (2008). Narcissism and sensitivity to criticism: A preliminary investigation. Current Psychology, 27(1), 62-76. [CrossRef]

- Back, M. D., Küfner, A. C. P., Dufner, M., Gerlach, T. M., Rauthmann, J. F., & Denissen, J. J. A. (2013). Narcissistic admiration and rivalry: Disentangling the bright and dark sides of narcissism. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 105(6), 1013–1037. [CrossRef]

- Back, M. D., Schmukle, S. C., & Egloff, B. (2008). Becoming friends by chance. Psychological Science, 19(5), 439-440. [CrossRef]

- Baumeister, R. F., & Leary, M. R. (1995). The need to belong: Desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychological Bulletin, 117(3), 497-529. [CrossRef]

- Besser, A., & Priel, B. (2010). Grandiose narcissism versus vulnerable narcissism in threatening situations: Emotional reactions to achievement failure and interpersonal rejection. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 29(8), 874-902. [CrossRef]

- Besser, A., & Zeigler-Hill, V. (2011). Pathological forms of narcissism and perceived stress during the transition to the university: The mediating role of humor styles. International Journal of Stress Management, 18(3), 197-221. [CrossRef]

- Brailovskaia, J., Bierhoff, H. W., & Margraf, J. (2019, Jun). How to identify narcissism with 13 items? Validation of the german narcissistic personality inventory-13 (g-npi-13). Assessment, 26(4), 630-644. [CrossRef]

- Brailovskaia, J., Teismann, T., Zhang, X. C., & Margraf, J. (2019). Grandiose narcissism, depression and suicide ideation in chinese and german students. Current Psychology, 40(8), 3922-3930. [CrossRef]

- Bressler, E. R., & Balshine, S. (2006). The influence of humor on desirability. Evolution and Human Behavior, 27(1), 29-39. [CrossRef]

- Brunell, A. B., Davis, M. S., Schley, D. R., Eng, A. L., van Dulmen, M. H., Wester, K. L., & Flannery, D. J. (2013). A new measure of interpersonal exploitativeness. Frontiers in Psychology, 4:299. [CrossRef]

- Burger, E., & Milardo, R. M. (2016). Marital interdependence and social networks. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 12(3), 403-415. [CrossRef]

- Cain, N. M., Pincus, A. L., & Ansell, E. B. (2008). Narcissism at the crossroads: Phenotypic description of pathological narcissism across clinical theory, social/personality psychology, and psychiatric diagnosis. Clinical Psychology Review, 28(4), 638–656. [CrossRef]

- Campbell, W. K., & Foster, J. D. (2007). The narcissistic self: Background, an extended agency model, and ongoing controversies. In C. Sedikides & S. J. Spencer (Eds.), The self (pp. 115-138). Psychology Press.

- Campbell, W. K., Rudich, E. A., & Sedikides, C. (2002). Narcissism, self-esteem, and the positivity of self-views: Two portraits of self-love. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 28(3), 358-368. [CrossRef]

- Cann, A., & Calhoun, L. G. (2001). Perceived personality associations with differences in sense of humor: Stereotypes of hypothetical others with high or low senses of humor. Humor: International Journal of Humor Research, 14(2), 117-130. [CrossRef]

- Cohen, S., & Wills, T. A. (1985). Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis. Psychological Bulletin, 98(2), 310-357. [CrossRef]

- Dehaghi, A. B. M., & Zeigler-Hill, V. (2021). Narcissistic personality features and social trust. Psihologijske Teme, 30(1), 57-75. [CrossRef]

- Demir, M., & Davidson, I. (2012). Toward a better understanding of the relationship between friendship and happiness: Perceived responses to capitalization attempts, feelings of mattering, and satisfaction of basic psychological needs in same-sex best friendships as predictors of happiness. Journal of Happiness Studies, 14(2), 525-550. [CrossRef]

- DeScioli, P., Kurzban, R., Koch, E. N., & Liben-Nowell, D. (2011). Best friends: Alliances, friend ranking, and the myspace social network. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 6(1), 6-8. [CrossRef]

- Dickinson, K. A., & Pincus, A. L. (2003). Interpersonal analysis of grandiose and vulnerable narcissism. Journal of Personality Disorders, 17(3), 188-207. [CrossRef]

- Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Buchner, A., & Lang, A. G. (2009, Nov). Statistical power analyses using g*power 3.1: Tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behavior Research Methods, 41(4), 1149-1160. [CrossRef]

- Gentile, B., Miller, J. D., Hoffman, B. J., Reidy, D. E., Zeichner, A., & Campbell, W. K. (2013, Dec). A test of two brief measures of grandiose narcissism: The narcissistic personality inventory-13 and the narcissistic personality inventory-16. Psychological Assessment, 25(4), 1120-1136. [CrossRef]

- Gosling, S. D., Rentfrow, P. J., & Swann, W. B. (2003). A very brief measure of the big-five personality domains. Journal of Research in Personality, 37(6), 504-528. [CrossRef]

- Greengross, G., Martin, R. A., & Miller, G. (2012). Personality traits, intelligence, humor styles, and humor production ability of professional stand-up comedians compared to college students. Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts, 6(1), 74-82. [CrossRef]

- Harris, K., & Vazire, S. (2016). On friendship development and the big five personality traits. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 10(11), 647-667. [CrossRef]

- Hartup, W. W., & Stevens, N. (2016). Friendships and adaptation across the life span. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 8(3), 76-79. [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A. F. (2022). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis. Guilford Press.

- Hendin, H. M., & Cheek, J. M. (1997). Assessing hypersensitive narcissism: A reexamination of murray's narcism scale. Journal of Research in Personality, 31(4), 588–599. [CrossRef]

- Henrich, J., Heine, S. J., & Norenzayan, A. (2010). Most people are not weird. Nature, 466(7302), 29. [CrossRef]

- Hollandsworth, A. (2019). Behind the laughs: The relationship between narcissism and humor styles in an individualistic culture (Publication Number 1) [Master's thesis, Middle Tennessee State University]. Available online: http://jewlscholar.mtsu.edu/xmlui/handle/mtsu/6029.

- Holt-Lunstad, J., Smith, T. B., Baker, M., Harris, T., & Stephenson, D. (2015). Loneliness and social isolation as risk factors for mortality: A meta-analytic review. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 10(2), 227-237. [CrossRef]

- Izard, C. (1960, Jul). Personality similarity and friendship [Empirical Study]. The Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 61(1), 47-51. [CrossRef]

- Jauk, E., Weigle, E., Lehmann, K., Benedek, M., & Neubauer, A. C. (2017). The relationship between grandiose and vulnerable (hypersensitive) narcissism. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 1600. [CrossRef]

- Jones, D. N., & Paulhus, D. L. (2014). Introducing the short dark triad (sd3): A brief measure of dark personality traits. Assessment, 21(1), 28-41. [CrossRef]

- Kaufman, S. B., Weiss, B., Miller, J. D., & Campbell, W. K. (2020). Clinical correlates of vulnerable and grandiose narcissism: A personality perspective. Journal of Personality Disorders, 34(1), 107-130. [CrossRef]

- Konrath, S., Bushman, B. J., & Grove, T. (2009). Seeing my world in a million little pieces: Narcissism, self-construal, and cognitive-perceptual style. Journal of Personality, 77(4), 1197-1228. [CrossRef]

- Körner, R., & Altmann, T. (2023). Personality is related to satisfaction in friendship dyads, but similarity is not: Understanding the links between the big five and friendship satisfaction using actor-partner interdependence models. Journal of Research in Personality, 107. [CrossRef]

- Krizan, Z., & Herlache, A. D. (2018, Feb). The narcissism spectrum model: A synthetic view of narcissistic personality. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 22(1), 3-31. [CrossRef]

- Larson, R. W., & Bradney, N. (1988). Precious moments with family members and friends. In R. M. Milardo (Ed.), Families and social networks (pp. 107-126). Sage.

- Lee, K., Ashton, M. C., Pozzebon, J. A., Visser, B. A., Bourdage, J. S., & Ogunfowora, B. (2009). Similarity and assumed similarity in personality reports of well-acquainted persons. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 96(2), 460-472. [CrossRef]

- Lobbestael, J., & Freund, V. L. (2021). Humor in dark personalities: An empirical study on the link between four humor styles and the distinct subfactors of psychopathy and narcissism. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 548450. [CrossRef]

- Martin, R. A., Puhlik-Doris, P., Larsen, G., Gray, J., & Weir, K. (2003). Individual differences in uses of humor and their relation to psychological well-being: Development of the humor styles questionnaire. Journal of Research in Personality, 37(1), 48-75. [CrossRef]

- Miller, J. D., Hoffman, B. J., Gaughan, E. T., Gentile, B., Maples, J., & Campbell, W. K. (2011, Oct). Grandiose and vulnerable narcissism: A nomological network analysis. Journal of Personality, 79(5), 1013-1042. [CrossRef]

- Montoya, R. M., Horton, R. S., & Kirchner, J. (2008). Is actual similarity necessary for attraction? A meta-analysis of actual and perceived similarity. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 25(6), 889-922. [CrossRef]

- Morf, C. C., & Rhodewalt, F. (2001). Unraveling the paradoxes of narcissism: A dynamic self-regulatory processing model. Psychological Inquiry, 12(4), 177-196. [CrossRef]

- O'Meara, J. (1989, Oct). Cross-sex friendship: Four basic challenges of an ignored relationship. Sex Roles, 21(7-8), 525-543. [CrossRef]

- Parker, J. G., & Asher, S. R. (1993). Friendship and friendship quality in middle childhood: Links with peer group acceptance and feelings of loneliness and social dissatisfaction. Developmental Psychology, 29(4), 611-621. [CrossRef]

- Paulhus, D. L., & Williams, K. M. (2002). The dark triad of personality: Narcissism, machiavellianism, and psychopathy. Journal of Research in Personality, 36(6), 556-563. [CrossRef]

- Pincus, A. L., Ansell, E. B., Pimentel, C. A., Cain, N. M., Wright, A. G. C., & Levy, K. N. (2009). Initial construction and validation of the pathological narcissism inventory. Psychological Assessment, 21(3), 365–379. [CrossRef]

- Pincus, A. L., & Lukowitsky, M. R. (2010). Pathological narcissism and narcissistic personality disorder. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 6, 421-446. [CrossRef]

- Raskin, R. N., & Hall, C. S. (1979). A narcissistic personality inventory. Psychological Reports, 45(2), 590. [CrossRef]

- Ruch, W., & Heintz, S. (2016). The german version of the humor styles questionnaire: Psychometric properties and overlap with other styles of humor. Europe's Journal of Psychology, 12(3), 434-455. [CrossRef]

- Sauls, D., & Zeigler-Hill, V. (2020). The narcissistic experience of friendship: The roles of agentic and communal orientations toward friendship. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 37(10-11), 2693-2713. [CrossRef]

- Sauls, D., Zeigler-Hill, V., Vrabel, J. K., & Lehtman, M. J. (2019). How do narcissists get what they want from their romantic partners? The connections that narcissistic admiration and narcissistic rivalry have with influence strategies. Personality and Individual Differences, 147, 33-42. [CrossRef]

- Selfhout, M., Denissen, J., Branje, S., & Meeus, W. (2009). In the eye of the beholder: Perceived, actual, and peer-rated similarity in personality, communication, and friendship intensity during the acquaintanceship process. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 96(6), 1152-1165. [CrossRef]

- van Zalk, M., & Denissen, J. (2015). Idiosyncratic versus social consensus approaches to personality: Self-view, perceived, and peer-view similarity. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 109(1), 121-141. [CrossRef]

- Wink, P. (1991). Two faces of narcissism. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 61(4), 590–597. [CrossRef]

- Wright, A. G., Lukowitsky, M. R., Pincus, A. L., & Conroy, D. E. (2010). The higher order factor structure and gender invariance of the pathological narcissism inventory. Assessment, 17(4), 467-483. [CrossRef]

- Ziegler, M., Kemper, C. J., & Kruyen, P. (2014). Short scales: Five misunderstandings and ways to overcome them. Journal of Individual Differences, 35(4), 185-189. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).