Submitted:

23 September 2024

Posted:

25 September 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results and Discussion

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Meynard, J.M.; Jeuffroy, M.H.; Le Bail, M.; Lefèvre, A.; Magrini, M.B.; Michon, C. Designing coupled innovations for the sustainability transition of agrifood systems. Agric. Syst. 2017, 15, 330–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunori, G.; Branca, G.; Cembalo, L.; D’Haese, M.; Dries, L. Agricultural and Food Economics: the challenge of sustaina-bility. Agric. Food Econ. 2020, 8, 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rockström, J.; Edenhofer, O.; Gaertner, J.; DeClerck, F. Planet-proofing the global food system. Nat. Food. 2020, 1, 3–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hebinck, A.; Klerkx, L.; Elzen, B.; Kok, K.P.; König, B.; Schiller, K.; Tschersich, J.; van Mierlo, B.; von Wirth, T. Beyond food for thought–Directing sustainability transitions research to address fundamental change in agri-food systems. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transitions 2021, 41, 81–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. Final report for the international symposium on agroecology for food security and nutrition; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- FAO. The 10 Elements of Agroecology Guiding the Transition to Sustainable Food and Agricultural Systems, 2018. Available online: https://www.fao.org/3/i9037en/i9037en.pdf.

- Bernard, B.; Lux, A. How to feed the world sustainably: an overview of the discourse on agroecology and sustainable intensification. Reg. Environ. Chang. 2016, 5, 1279–1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wezel, A.; Herren, B.G.; Kerr, R.B.; Barrios, E.; Gonçalves, A.L.R.; Sinclair, F. Agroecological principles and elements and their implications for transitioning to sustainable food systems. A review. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2020, 40, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsner, F.; Herzig, C.; Strassner, C. Agri-food systems in sustainability transition: A systematic literature review on recent developments on the use of the multi-level perspective. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2023, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wezel, A.; Bellon, S.; Doré, T.; Francis, C.; Vallod, D.; David, C. Agroecology as a science, a movement and a practice. Sustain. Agric. 2009, 2, 27–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gliessman, SR. Defining Agroecology. Agroecol. Sustain. Food Syst. 2018, 42, 599–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tittonell, P. Assessing resilience and adaptability in agroecological transitions. Agric. Syst. 2020, 184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peeters, A.; Dendoncker, N.; Jacobs, S. Enhancing Ecosystem Services in Belgian Agriculture through Agroecology: A Vision for a Farming with a Future. Elsevier 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duru, M.; Therond, O.; Fares, M.H. Designing agroecological transitions; A review. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2015, 35, 1237–1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansen, K. The debate on food sovereignty theory: agrarian capitalism, dispossession and agroecology. J. Peasant Stud. 2015, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wezel, A.; Brives, H.; Casagrande, M.; Clement, C.; Dufour, A.; Vandenbroucke, P. Agroecology territories: places for sustainable agricultural and food systems and biodiversity conservation. Agroecol. Sustain. Food Syst. 2016, 40, 132–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beudou, J.; Martin, G.; Ryschawy, J. Cultural and territorial vitality services play a key role in livestock agroecological transition in France. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2017, 37, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinrichs, C.C. Transitions to sustainability: a change in thinking about food systems change? Agric. Human Values 2014, 31, 143–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rotmans, J.; Kemp, R.; van Asselt, M.; Geels, F.; Verbong, G.; Molendijk, K. Transities en Transitiemanagement: De Casus Van Een Emissiearme Energievoorziening; ICIS: Maastricht, Netherlands, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Rip, A.; Kemp, R. Technological change. In Human Choice and Climate Change; Rayner, S., Majone, E.L., Eds.; Battelle Press: Columbus, USA, 1998; Volume 2, pp. 327–399. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, A. Transforming technological regimes for sustainable development: a role for alternative technology niches? Science and Public Policy 2003, 30, 127–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moors, E.; Rip, A.; Wiskerke, J.S. The dynamics of innovation: a multilevel co-evolutionary perspective. In Seeds of transition: essays on novelty production, niches and regimes in agriculture; Wiskerke, J.S., Van der Ploeg, J.D., Eds; Royal Van Gorcum, Assen, Netherlands, 2004, pp. 31–56. https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/29288494.

- Seyfang, G.; Smith, A. Community action: A neglected site of innovation for sustainable development? In Proccedings of CSERGE - The Centre for Social and Economic Research on the Global Environment /EDM - Environmental Decision Making, Norwich, England (2006). https://www.econstor.eu/bitstream/10419/80279/1/513781323.

- Durand, M.H.; Désilles, A.; Saint-Pierre, P.; Angeon, V.; Ozier-Lafontaine, H. Agroecological transition: A viability model to assess soil restoration. Nat. Resour. Model. 2017, 30, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merot, A.; Belhouchette, H.; Saj, S.; Wery, J. Implementing organic farming in vineyards. Agroecol. Sustain. Food Syst 2020, 44, 164–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stratton, A.E.; Wittman, H.; Blesh, J. Diversification supports farm income and improved working conditions during agroecological transitions in southern Brazil. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2021, 41, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chizallet, M.; Prost, L.; Barcellini, F. Comprendre l’activité de conception d’agriculteurs en transition agroécologique: vers un modèle trilogique de la conception. Psychol. Française 2019, 64, 119–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plateau, L.; Roudart, L.; Hudon, M.; Maréchal, K. Opening the organisational black box to grasp the difficulties of agroecological transition. An empirical analysis of tensions in agroecological production cooperatives. Ecol. Econ. 2021, 185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albort-Morant, G.; Ribeiro-Soriano, D. A bibliometric analysis of international impact of business incubators. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 1775–1779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donthu, N.; Kumar, S.; Mukherjee, D.; Pandey, N.; Lim, W.M. How to conduct a bibliometric analysis: An overview and guidelines. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 133, 285–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zupic, I.; Čater, T. Bibliometric methods in management and organization. Organ. Res. Methods 2020, 18, 429–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Eck, N.J.; Waltman, L. Bibliometric mapping of the computational intelligence field. Int. J. Uncertainty, Fuzziness Knowledge-based Syst. 2007, 15, 625–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nobanee, H.; Al Hamadi, F.Y.; Abdulaziz, F.A.; Abukarsh, L.S.; Alqahtani, A.F.; AlSubaey, S.K.; Alqahtani, S.M.; Almansoori, H.A. A bibliometric analysis of sustainability and risk management. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- das Chagas Oliveira, F.; Calle Collado, A.; Carvalho Leite, L.F. Peasant Innovations and the Search for Sustainability: The Case of Carnaubais Territory in Piauí State, Brazil. J. Sustain. Agric. 2012, 36, 523–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salin, T.C.; Ferreira, R.L.C.; Albuquerque, S.D.; Silva, J.D.; Alves Junior, F.T. Productive agricultural systems characterization in the Brazilian semiarid as subsidy to agroforestry planning. Rev. Caatinga 2012, 25, 109–118. [Google Scholar]

- Skonieski, F.R.; Viégas, J.; Cruz, P.; Nornberg, J.L.; Bermudes, R.F.; Gabbi, A.M. Dynamics of nitrogen concentration on intercropped ryegrass. Acta Scientiarum. Anim. Sci. 2012, 34, 01–06. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, S.B.; MacRae, R.J. Conceptual Framework for the Transition from Conventional to Sustainable Agriculture J. Sustain. Agric. 1996, 7, 81–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geels, F.W. Technological transitions as evolutionary reconfiguration processes: A multi-level perspective and a case-study. Res. Policy 2002, 31, 1257–1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geels, F.W. From sectoral systems of innovation to socio-technical systems: Insights about dynamics and change from sociology and institutional theory. Res. Policy 2004, 33, 897–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geels, F.W.; Schot, J. Typology of sociotechnical transition pathways. Res. Policy 2007, 36, 399–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polita, F.S.; Madureira, L. Transition Pathways of Agroecological Innovation in Portugal’s Douro Wine Region. A Multi-Level Perspective. Land 2021, 10, 0322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polita, F.S.; Madureira, L. Evolution of Short Food Supply Chain Innovation Niches and its Anchoring to the Socio-Technical Regime: The Case of Direct Selling through Collective Action in North-West Portugal. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wigboldus, S.; Klerkx, L.; Leeuwis, C.; Schut, M.; Muilerman, S.; Jochemsen, H. Systemic perspectives on scaling agricultural innovations. A review. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2016, 36, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Ricketts, T.H.; Kremen, C.; Carney, K.; Swinton, S.M. Ecosystem services and dis-services to agriculture. Ecological economics 2007, 4, 0–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caron, P.; Biénabe, E.; Hainzelin, E. Making transition towards ecological intensification of agriculture a reality: the gaps in and the role of scientific knowledge. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2014, 8, 44–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonaudo, T.; Bendahan, A.B.; Sabatier, R.; Ryschawy, J.; Bellon, S.; Leger, F.; Magda, D.; Tichit, M. Agroecological principles for the redesign of integrated crop–livestock systems. Eur. J. Agron. 2014, 57, 43–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wezel, A.; Casagrande, M.; Celette, F.; Vian, J.F.; Ferrer, A.; Peigné, J. Agroecological practices for sustainable agriculture. A review. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2014, 34, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kremen, C.; Iles, A.; Bacon, C. Diversified Farming Systems: An Agroecological, Systems-based Alternative to Modern Industrial Agriculture. Ecol. Soc. 2012, 17, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumont, B.; Fortun-Lamothe, L.; Jouven, M. , Thomas, M.; Tichit, M. Prospects from agroecology and industrial ecology for animal production in the 21st century. Animal 2013, 7, 1028–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wezel, A.; Bellon, S.; Doré, T.; Francis, C.; Vallod, D.; David, C. Agroecology as a Science, a Movement and a Practice. In Sustainable Agriculture; Lichtfouse, E.; Hamelin, M.; Navarrete, M.; Debaeke, P. Eds. Springer: Dordrecht, Netherlands 2011, 2, 27–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altieri, M.A.; Toledo, V.M. The agroecological revolution in Latin America: rescuing nature, ensuring food sovereignty and empowering peasants ensuring food sovereignty and empowering peasants. J. Peasant Stud. 2011. [CrossRef]

- Rosset, P.M.; Machín Sosa, B.; Roque Jaime, A.M.; Ávila Lozano, D.R. The Campesino-to-Campesino agroecology movement of ANAP in Cuba: social process methodology in the construction of sustainable peasant agriculture and food sovereignty. J. Peasant Stud. 2010, 161–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Méndez, V.E.; Bacon, C.M.; Cohen, R. Agroecology and sustainable food systems agroecology as a transdisciplinary, participatory, and action-oriented approach. Agroecology and Sustainable Food Systems 2013, 3565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Méndez, V.E.; Caswell, M.; Gliessman, S.R.; Cohen, R. Integrating agroecology and participatory action research (PAR): Lessons from Central America. Sustainability 2017, 9, 705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levidow, L.; Pimbert, M.; Vanloqueren, G. Agroecological research: conforming — or transforming the dominant agro-food regime? Agroecol. Sustain. Food Syst. 2014, 38, 1127–1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez de Molina, M. Agroecology and politics. how to get sustainability? About the Necessity for a political agroecology. Agroecol. Sustain. Food Syst. 2013, 37, 45–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giraldo, O.F.; Rosset, P.M. Agroecology as a territory in dispute: between institutionality and social movements. J. Peasant Stud. 2018, 45, 545–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosset, P.M.; Martínez-Torres, M.E. Rural social movements and agroecology: context, theory, and process. Ecology and Society 2012, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holt-Giménez, E.; Altieri, M.A. Agroecology and Sustainable Food Systems Agroecology, Food Sovereignty, and the New Green Revolution. Agroecol. Sustain. Food Syst. 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mier y Terán Giménez Cacho, M. , Giraldo, O.F., Aldasoro, M., Morales, H., Ferguson, B.G., Rosset, P., Khadse, A.; Campos, C. Bringing agroecology to scale: key drivers and emblematic cases. Agroecol. Sustain. Food Syst. 2018, 42, 637–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholls, C.I.; Altieri, M.A. Pathways for the amplification of agroecology. Agroecol. Sustain. Food Syst. 2018, 42, 1170–1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seufert, V.; Ramankutty, N.; Foley, J.A. Comparing the yields of organic and conventional agriculture. Nature 2012, 485, 229–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. TAPE Tool for Agroecology Performance Evaluation 2019 – Process of development and guidelines for application. Test version. FAO: Rome, Italy, 2019. https://www.fao.org/3/ca7407en/ca7407en.

- HLPE Agroecological and Other Innovative Approaches for Sustainable Agriculture and Food Systems That Enhance Food Security and Nutrition; A Report by the High Level Panel of Experts on Food Security and Nutrition of the Committee on World Food Security. HLPE: Rome, Italy, 2019.

- Gliessman, S. Building a global network for agroecology at FAO. Agroecol. Sustain. Food Syst. 2024, 48, 917–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Union. Farm to Fork Strategy. For a Fair, Healthy and Environmentally-Friendly Food System. Available online: https://food.ec.europa.eu/horizontal-topics/farm-fork-strategy_en (accessed on 20 June 2024).

- European Comission. European Green Deal. Available online: https://commission.europa.eu/strategy-and-policy/priorities-2019-2024/european-green-deal_en (accessed on 20 June 2024).

- Wrzaszcz, W.; Prandecki, K. Agriculture and the European Green Deal. Zagadnienia Ekon. Rolnej/Problems Agric. Econ. 2020.

- Riccaboni, A.; Neri, E.; Trovarelli, F.; Pulselli, R.M. Sustainability-oriented research and innovation in ‘farm to fork’ value chains. Curr. Opin. Food Sci. 2021, 42, 102–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boix-Fayos, C.; de Vente, J. Challenges and potential pathways towards sustainable agriculture within the European Green Deal. Agric. Syst. 2023, 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caporal, F.R.; Costabeber, J.A. Agroecologia: alguns conceitos e princípios; MDA/SAF/DATER: Distrito Federal, Brasil, 2004; pp. 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Gliessman, S. A Framework for the Conversion to Food System Sustainability. J. Sustain. Agric. 2009, 33, 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bui, S.; Cardona, A.; Lamine, C.; Cerf, M. Sustainability transitions: Insights on processes of niche-regime interaction and regime reconfiguration in agri-food systems. J. Rural Stud. 2016, 48, 92–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

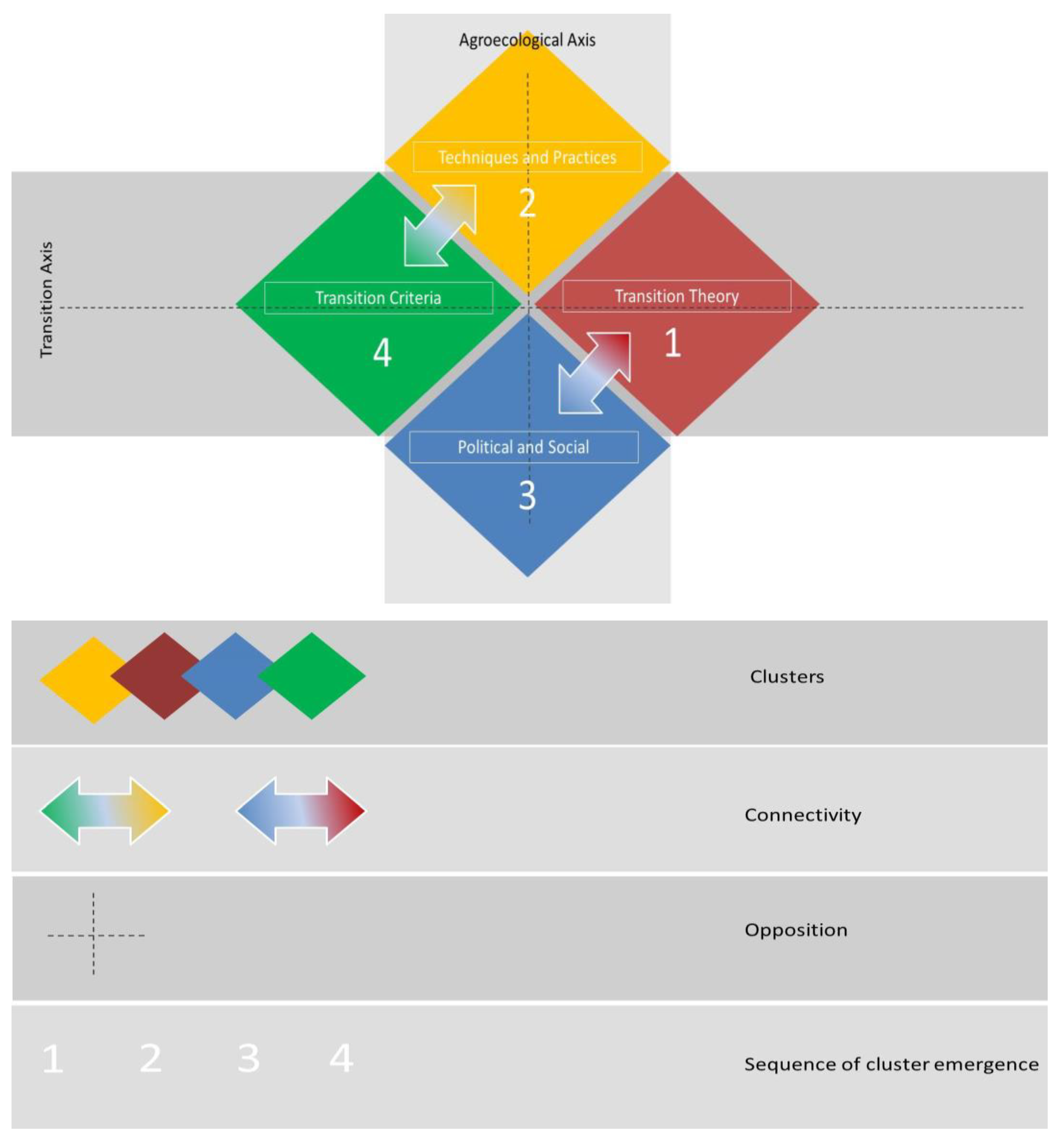

| Cluster and its denomination | Description of the main contents obtained from more frequently used keywords |

|---|---|

|

Agroecology (red color cluster) |

Agroecology is the main descriptor of the documents (98 appearances). It has related to the innovation topic (8) and organic farming and conservation agriculture (organic farming - 5, conservation agriculture - 5). |

|

Sustainability (blue color cluster) |

The articles mobilise sustainability (22) together with concepts like practices (7), systems (6), and food safety (6). |

|

Transition (green color cluster) |

It groups publications that focus on agroecological transition as a main descriptor (60), which, in turn, relates to agroecological practices (6), participative research (5), and the sustainability of the whole food system (5). |

|

Ecosytemic services (purple cluster) |

It mobilises concepts pertaining to ecosystemic services (13), the agroecosystem (6), and biodiversity (5). |

|

Food sovereignty (yelow cluster) |

The main descriptor in this cluster is food sovereignty (13). The subject is connected with family farming (8) and public policies (7). |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).