1. Introduction

Over the last decades, public spaces received a renovated attention as a major

locus of social life within cities. In particular, urban green spaces (UGS) such as greenways, gardens, squares and parks become preconditions to assure urban sustainability, improve citizens’ physical and mental health and enhance the overall urban life quality, especially after the unfolding of COVID-19 pandemic [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6]. The array of studies highlighting the benefits of UGS to local communities are diverse; from relating green space availability and well-being levels [

7,

8,

9], to the importance of UGS for sense of connection among people [

10], until its role in the alleviation of migrants homesick syndrome [

11].

In the specific case of China, the discussions addressing the topic of use of space within UGS have been focused in the role of perception mechanism, and how it can influence the use of space of UGS. Zhang et al [

12] investigated the reasons driving the behavior of urban residents to use UGS, aiming to discover not just the type of physical activities happening in a given UGS but also the variables affecting the perception of UGS as spaces for physical activities. Chen and colleagues [

13] also tried to access the perceived value of recreation and physical activities on Chinese UGS, showing that waterfronts and areas with green elements were perceived as highly dynamic and multi-functional. Similarly, Chen et al [

14] measured the perception of green space to promote health on the resident’s willingness to use parks. Xue and colleagues [

15], run a comparative study between Hong Kong and Singapore and identified that users prefer to use spaces related to natural plants, forest and tree lawns, while site facilities and man-made structures were perceived as less important. In the same way, Pan et al [

16] found that activities realized close to the greenery (sightseeing, collecting food, doing picnic or watching birds) were ranked as the most important ones among park users. These studies emphasizes the significance of perception mechanisms in influencing the use of UGS by elucidating how different elements, such as types of physical activity, perceived recreational value and natural assets influence populations' will (desire) to engage to these spaces.

Another group of studies focused on understanding how human behavior interacts with and is influenced by the physical environment. Rather than focusing in the perception, these studies investigated the diversity of actions, reactions, and interactions that individuals or groups exhibit in response to their surroundings, in our case UGS. Jia at al [

17] investigated the frequency of use of space in a comparative study among Chinese and users from Canada and USA, revealing that Chinese have a higher use frequency of UGS, especially in neighborhood parks. Wang and Wu [

18] conducted a study focusing to discover the specific design features that may influence UGS use in downtown Shanghai. Using behavior mapping and GIS techniques, they correlated the architectural settings and physical activities to conclude that plazas and lawns tend to attract active users, while pergolas and pavilions were used to sedentary behavior. Similarly, Liu and colleagues [

19] addressed the question of how UGS settings influences physical activity intensity in different demography groups. System for Observing Play and Recreation in Communities (SOPARC) was used to study Tianhe Park in Guangzhou to conclude that moderate-to-vigorous physical activities were more common on lawns and jogging trails, and adults, especially females, were the majority of users. Wang et al [

20] relied in on-site observation to reveal that variables associated to physical activity diversity were positively affected by green coverage area and shrub diversity, while the shape of paved areas, visible greenery and tree diversity seems to limit it. Our study follows this same theoretical perspective, trying to access the types of activities through direct observation at three urban parks in downtown Shanghai.

However, while the literature is rich in studies characterizing the types of use of space in Chinese UGS, there is an absence of studies investigating the nature of the use, or in another words, how the users engage with, modify or redefine a given spatiality. In our point of view, the analysis could be enhanced through the concept of appropriation of space. In this article, we will discuss UGS from the perspective of use and appropriation of the space. The distinction between use and appropriation of space highlights different levels of interaction with the urban environment. Henri Lefebvre [

21] considered use as the functional, intended utilization of space, following societal norms and planning. Appropriation, however, transforms space as individuals claim and adapt it for their own needs, often challenging its prescribed functions. De Certeau [

22] describes this through "tactics," where everyday actions subvert dominant uses. Sennett [

23] adds that appropriation redefines the social and cultural meanings of public spaces, going beyond mere use to reflect creativity. Other authors will use the concept of Place, to explain spaces transformed by the use and appropriation [

24,

25] and even non-place in the absence of appropriation [

26].

The significance of this work relies on the fact that appropriation nurtures a sense of ownership, emotional connection, and active participation, encouraging users to interact with the environment in more unrestricted and imaginative ways [

24,

25,

27,

28,

29,

30]. Therefore, investigating appropriation of space in UGS allows a deeper understanding about its socio-spatial dynamics and prompts information to enhance design and management decisions.

2. Theoretical Framework

In the field of urban studies, the term "space appropriation" refers to the different ways in which individuals or groups interact with, live in, and alter public and private areas in ways that were not initially planned or designed. This phenomenon involves a dynamic interaction in which residents engage with their surroundings, resulting in the creation of new meanings, behaviors, and social relationships through the use of space [

21]. Important aspects of space appropriation are the informal utilization and modification of space. This can be seen in activities like street vending, impromptu gatherings, or unscheduled performances, which deviate from the intended use of a spatial setting. Space appropriation ultimately emphasizes the proactive involvement of humans in altering their surroundings, emphasizing the dynamic and disputed characteristics of urban spaces [

23]

The notion of spatial appropriation appeared early in the field of environmental psychology, as an analytical category to explain territorial relationship, privacy and attachment to the space. The concept of appropriation has its foundations in the work of Leontyev [

31], who highlighted two major characteristics of appropriation; the shared experience of use, since it always happen under the mediation of other individuals (intercourse), and the existence of accumulated experience embodied into each object appropriated, implying that using something is always using under specific rules. Korosec-Serfaty later applied the concept to the urban context, observing that although public spaces operated under similar social norms, it was the morphological component—the design—that primarily dictated differences in use and function [

32]. She added that appropriation of an object does not mean property, or legal title of possession, but a moral, psychological and emotional control allowing the user to adapt a given object to his needs, turning it into a mean of self-expression, a social practice transforming public spaces into "customized" areas [

32]. Sansot reinforced this notion stressing that appropriation is also based on identification and what the individual recognizes as belonging to him. Although appropriation is essentially related to the action, the process must be put under perspective: to realize the action, it is necessary the existence of affection to the object and involvement between the subject and the object [

33]. Chombart De Lauwe complements this point stressing that appropriation is a psychological process related not just with perception and practices, but also with representations, desires, values and imaginary, situating the idea of appropriation as a dialectical subject-object process formed by the subject’s psychosocial process of appropriation, and the object, i.e., the spaces of everyday life [

34]. In this sense, Pol [

35] affirmed that space appropriation is the process that turns a meaningless space into a meaningful place. Basically a dual model which a transformed space (via appropriation) creates identification and therefore generates the feeling of well-being, driving the user’s actions towards more customization and leading the process to action-transformation cycle. Proshansky stated that appropriation is done by restructuring and rearranging things or objects to communicate through signs and marks that an individual or group are in control of such space, stablishing ownership. From his perspective, space appropriation is not just self-oriented, but also social-oriented in order to communicate power [

36]. Lara-Hernandez and Melis [

37] advance further in this idea conceiving the concept of Temporary Appropriation (TA), as a product of urban social inequalities. TA is characterized by unexpected and ephemeral activities (uses) performed on settings where these uses should not happen. Since these types of activities are deeply connected to the social context, they represents users’ tactics to stand as active subjects in the everyday life [

37].

In this study, appropriation will be adopted as a key analytical category for examining the use of space within UGS. According to the theoretical framework, appropriation is understood as a dynamic and evolving concept, rather than a fixed one, and as such, it will be treated as a progressive variable throughout the analysis, ranging from the utilitarian use, passing through identification, customization, ownership and undesirable level. The objective of this study is to explore the dynamic relationship between the physical design of UGS and the social practices of space appropriation: This would focus on how design features either facilitate or constrain appropriation and the resulting behaviors in these spaces, specifically the UGS at downtown area of Shanghai, China. The research questions driving this study are:

RQ1: How can the use of urban green spaces (UGS) in downtown Shanghai be characterized at a broad, systemic level?

RQ2: In the studied UGS, what is the relationship between the intensity and diversity of use and the appropriation of space?

RQ3: To what extent appropriation of space exists in the studied UGS?

3. Materials and Methods

The study adopts a mixed-methods research design to comprehensively examine space use in three major UGS in downtown Shanghai. This approach combines quantitative systematic behavior mapping with qualitative field observations, allowing the study to capture both the measurable patterns of human behavior and the contextual subtleties of space appropriation [

38].

Mixed-methods designs are particularly suitable in social sciences research, where understanding human interactions with the environment requires triangulating numerical data with interpretive insights [

39]. In this study, quantitative methods, such as systematic behavior mapping, allow for precise tracking and analysis of frequency, intensity, and diversity of space use. For instance, structured mapping can quantify how different sections of a UGS are used, how often specific activities (e.g., walking, sitting, playing) occur, and in what contexts. This data helps establish generalizable patterns [

38,

40].

At the same time, qualitative field observations provide an interpretative layer, capturing the underlying reasons behind these behaviors, including cultural practices, personal preferences, or socio-spatial dynamics. Observational notes and interactions can reveal how space is appropriated—how users modify spaces to fit their needs, such as by using seating areas for informal gatherings or converting walking paths into singing stages. Therefore, this dual approach enables the study to contextualize quantitative findings, helping to explain not just why certain spaces are used intensively while others remain underutilized, but also classify the uses according to how different groups interact with, adapt, and transforms the space [

40].

3.1. Study Area

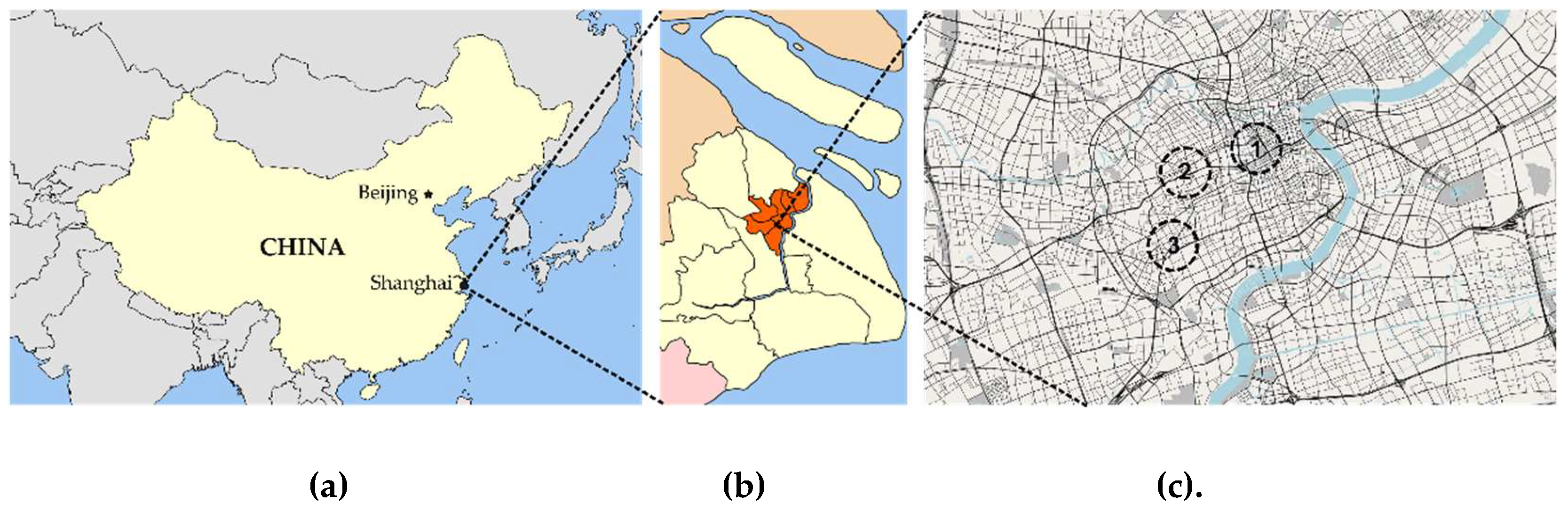

Shanghai, the largest city in China, holds the administrative status of a municipality directly under central government control, equivalent to that of a province. With a population of 26.3 million inhabitants (41), it spans a total land area of 6,340 square kilometers, strategically located at the confluence of the Yangtze River and the East China Sea. The metropolitan area consists of 17 districts, divided into the downtown core, inner suburbs, and outer suburbs.

Downtown Shanghai, known for its dense urbanization and dynamic economic activity, serves as the city’s commercial, cultural, and financial center. This area includes the districts of Huangpu, Jing’An, and Xuhui, which feature a mix of high-rise buildings, historical landmarks, and busy streets. Shanghai’s role as a leading financial hub in China and globally emphasizes the significance of its urban environment.

Due to the diversity of cultures and density of occupation, both from foreign and domestic migrants living in downtown, three parks in this area were selected as study cases: Renmin Park, Jing'An Park, and Xujiahui Park (

Figure 1). These parks were chosen as case studies to reflect the diversity of urban contexts and allow for comparative analysis of spatial use across different settings, improving the generalizability of findings [

39]. Despite each park having unique historical and design features, they are similar in terms of size and frequency of visitors, making them ideal for comparing patterns of human activity. By collecting data from multiple locations, the study reduces the risk of site-specific biases, providing more robust conclusions about the broader use and appropriation of public spaces [

39]. This approach enables the findings to extend beyond individual sites and reflect broader urban trends in space usage across the city's urban core.

Xujiahui Park, located in the Xuhui District, was inaugurated in 1999 on the site of a former industrial area, covering approximately 86,600 square meters. It is known for its ecological restoration efforts, featuring a large artificial lake and diverse vegetation. Renmin Park, or People's Park, is situated in the Huangpu District, adjacent to People's Square. It was built in 1952 on the grounds of a former horse racing track, covering around 98,200 square meters, and serves as a central space for public gatherings and cultural activities. Jing'An Park located in the Jing'An District next to Jing'An Temple, spans roughly 30,000 square meters and was reopened in 1954 after being repurposed from a former cemetery. All the three parks are categorized as Comprehensive Parks, which are designed for abundant recreational features, corresponding facilities, and large land scale, suitable for all kinds of public outdoor activities to meet the diverse needs of urban residents [

42,

43]. Parks in this category are typically situated in the core of cities, functioning as UGS for both active and passive recreation, often serving as hubs for social interaction and community activities, cultural events and exhibitions.

3.2. Preliminary Observation

In ethnography, observation constitutes a fundamental method for analyzing human behavior in its natural setting, offering insights into cultural, social, and behavioral practices. This method can be categorized into two primary types: participant and non-participant observation [

44]. Participant observation requires the researcher to actively engage in the community’s daily activities while balancing participation and detachment, thereby allowing for a firsthand comprehension of participants' perspectives alongside systematic observations of their behavior and interactions with spatial settings, which is important in this study [

45]. However, given the cultural constraints specially posed by language, participant observation was not suitable as a method. In contrast, non-participant observation involves the researcher observing without direct engagement, leading to less intrusive but potentially more objective data collection, though it might lack the depth achieved through firsthand experience [

45]. Non-participant observation is characterized by immersion, flexibility in focus adjustment, and contextual richness, where both observable behaviors and underlying cultural meanings can be explored in detail [

46]. This method is particularly valuable for uncovering implicit social norms, routines, and the ways people interact within their physical settings.

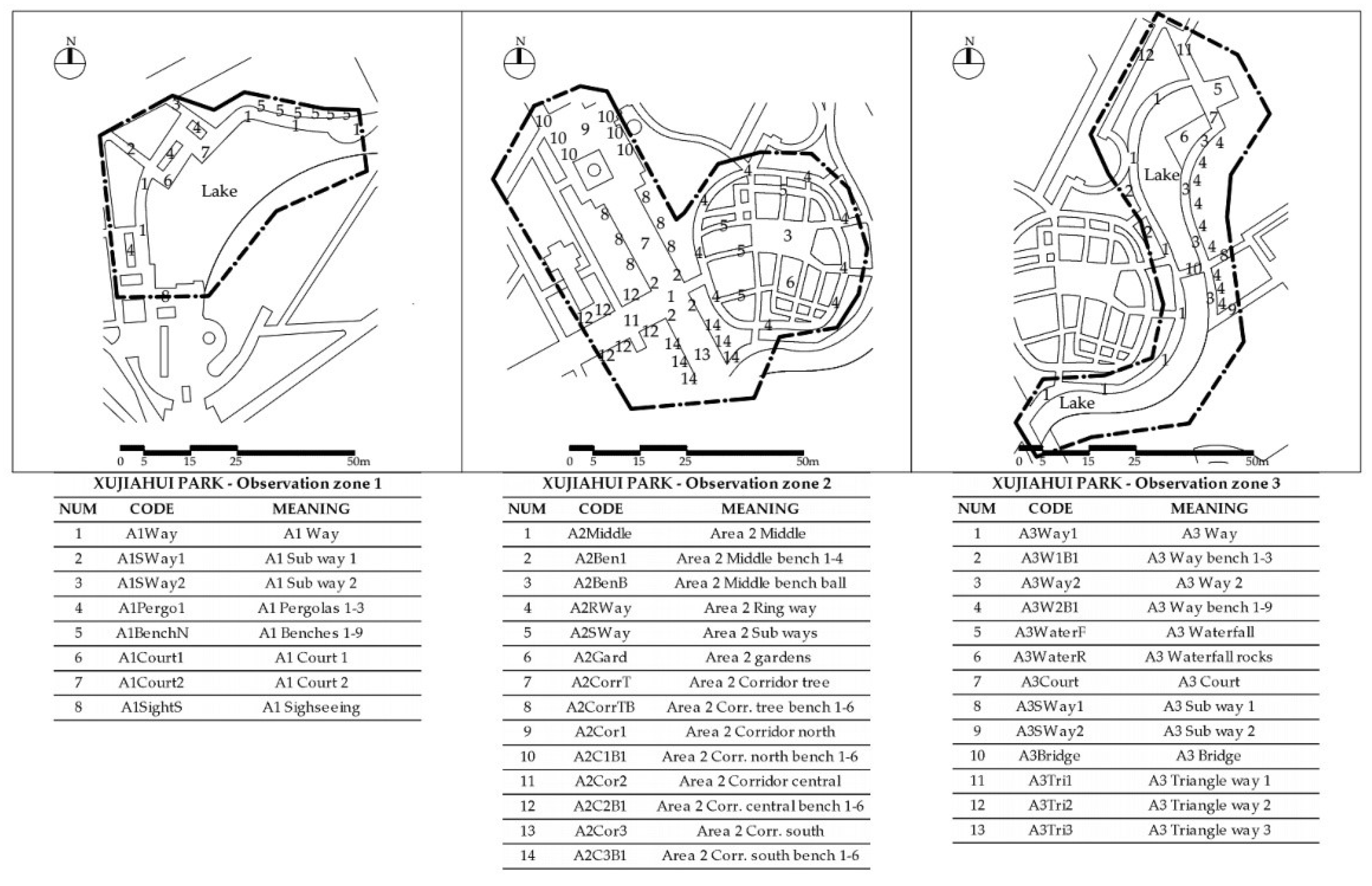

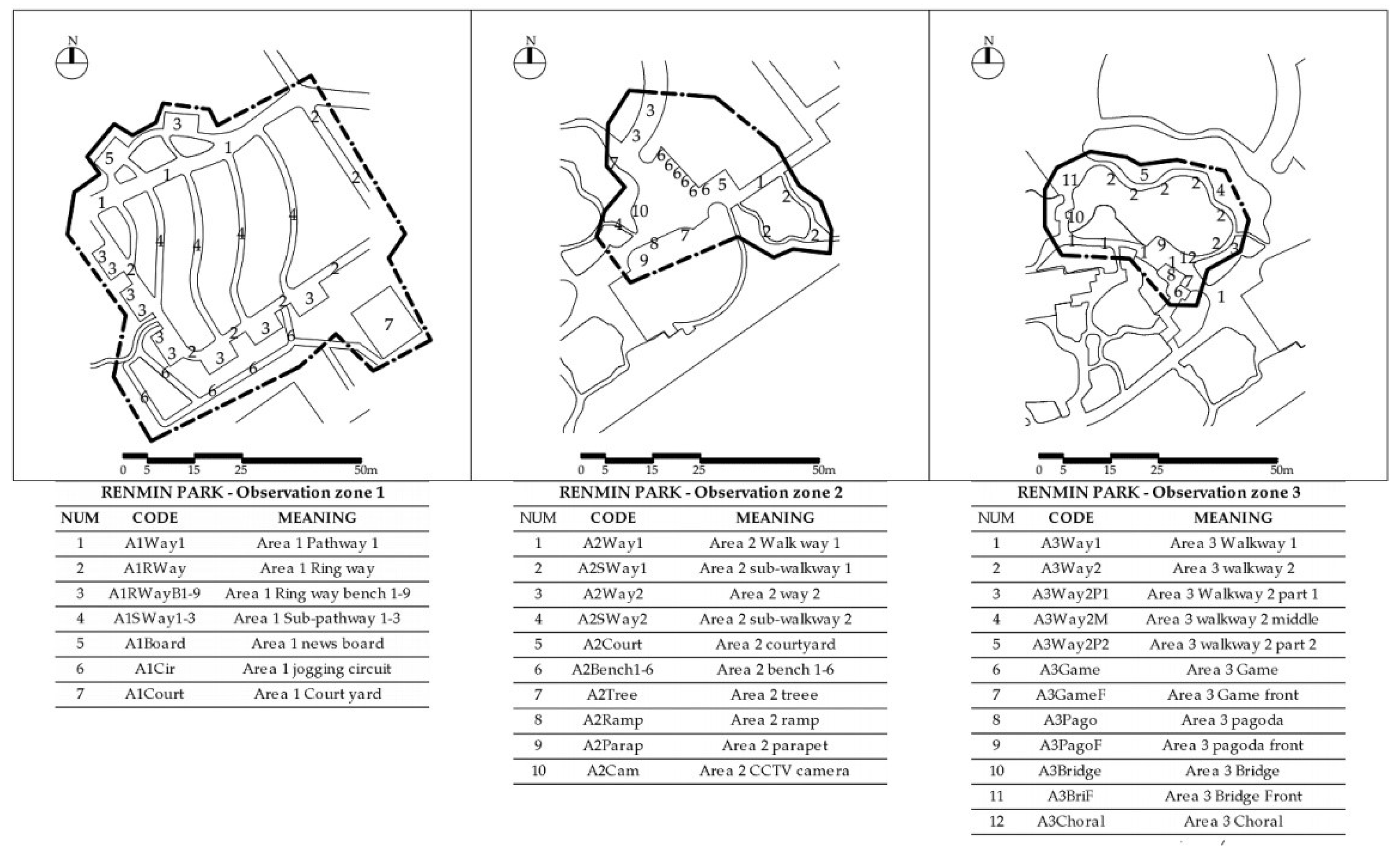

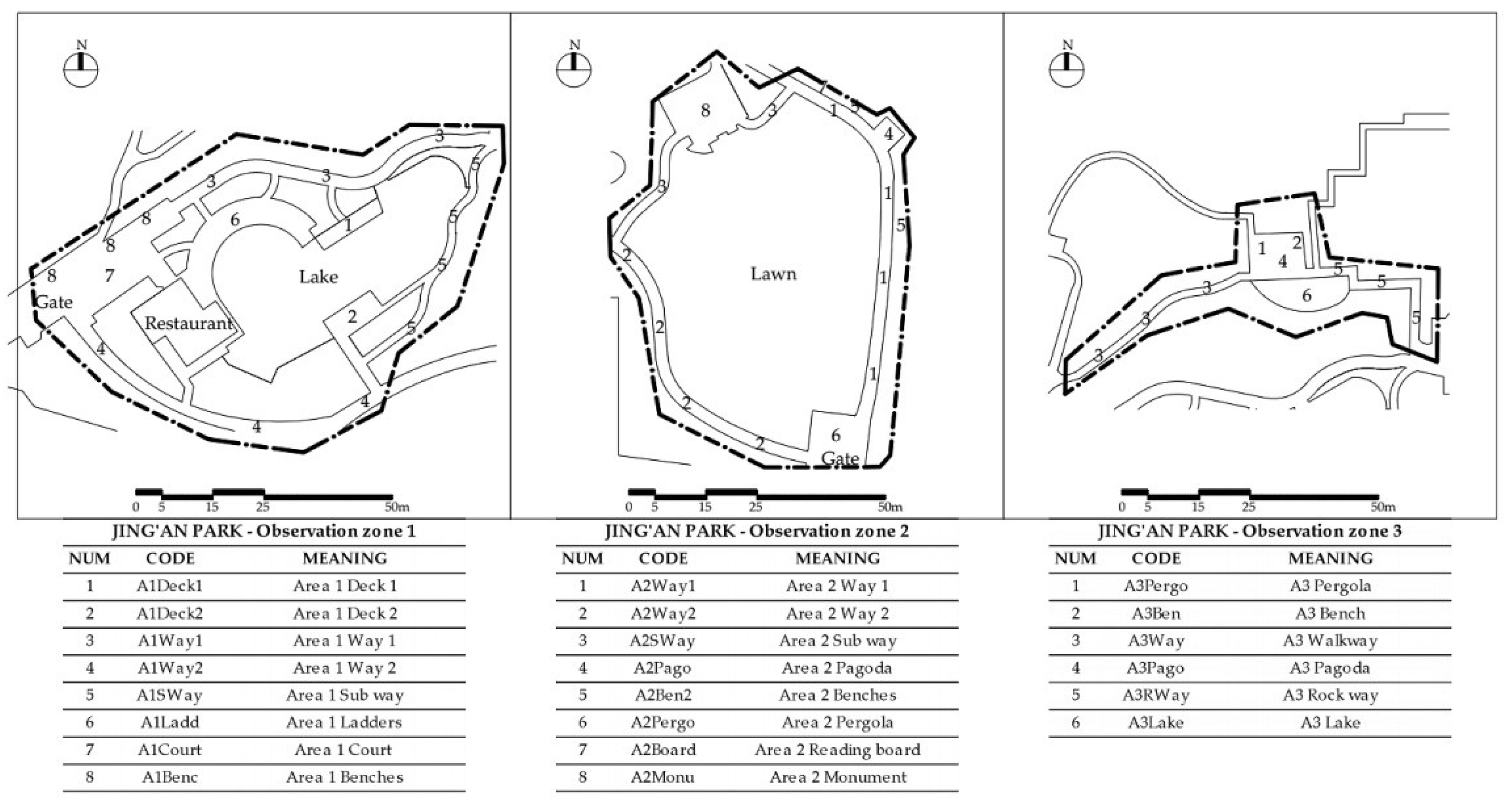

A preliminary observation was conducted in order to be familiar to the study area and to collect information aiming to produce a base map for each park and to code categories of activities. This observation consisted of walkthroughs, note taking, sketches and photographies, being 2 observation days for each park, during mornings and afternoons on 2019 May. As a first result, a map of each park was produced in CAD software, based in the official map showed in the park’s brochure provided by their in-park office and

in loco measurement when necessary. Each map were printed in scale of 1:1000. Based on this map and field notes, a smaller fraction of the park was selected, since to study the entire park with a single researcher was not feasible. The selection of each Zone was based in parameters such as diversity of activity, spatial settings and visibility range. The three Observation zones (Zone) were chosen to be observed in each park, receiving a general identification; Zone1, Zone2 and Zone3. For each Zone, a number and its correspondent setting code identify each spatial setting (

Figure 2,

Figure 3 and

Figure 4).

Subsequently, each Zone was investigated, following well know and stablished observation protocol [

46]. Each park was observed during 3 days, from 9 a.m. to 12 p.m. and 1 p.m. to 5 p.m. Both morning and afternoon sessions lasted 1h and 20 minutes in each zone, totalizing nine zones being observed for 4 hours (3 sessions) of note-taking for each zone. Note-taking focused on several key characteristics to ensure that the data collected was comprehensive and objective. Descriptive details about activity were prioritized, capturing observable behaviors, interactions, and environmental factors without interpretation. This includes who were involved, what activities were taking place, the physical setting, and any relevant contextual features. Temporal elements such as the timing, duration, and sequence of observed events were also observed since observation were done during the peak of temperatures in 2019 summer.

The notes were separated between objective descriptions and subjective impressions, ensuring that any interpretations or insights were clearly discernable as such. There was also noted reflections on how the observer presence could influence the observations and the potential biases could influence on interpretation of data. Also about the activities observed, we used a structured coding system to categorize behaviors aiming to improve reliability and to be added in the next stage of behavior mapping.

In addition to the park maps, the Zones and its spatial settings, another important outcome from the observation was a coded list of the observed behaviors, to be used as part of the behavior mapping protocol.

3.3. Behavior Mapping

Behavior mapping (BM) is recognized as a systematic observation method to record types of behavior, frequencies and the correlation between these activities within physical settings. Originally, Ittelson [

47] developed BM to study psychiatric wards in 1970 and since then, it is being used in other academic fields and for different purposes. Cooper-Marcus and Francis [

38] and Gehl [

48] added more details in the process, such as accurate location of each user on the map and stated the importance of time and weather condition. PPS [

49] developed a technique where the map is divided into a matrix of zones to record the uses on each zone, and later, Moore and Cosco [

50] introduced Geographic Information Systems (GIS) techniques into the BM protocol to improve accuracy and allow data manipulation through computational tools. Marušic and Marušic followed this approach as well [

51]. In general, BM is considered a major method to investigate spatial performance, especially the relation between the current uses at a given setting and its original function intended by design. The main questions that BM can answer relates to the intensity of use in different settings and which design features can produce social interactivity. In our data collection, we followed the original protocol stated by Ittelson [

47] with some minor adaptations.

A trained observer previously spent sufficient time studying the area and conducting note-taking, collected the data set in each Zone. Observations were conducted during summer of 2019 (July and August), in a total of 22 days of observation, 7 days on each park, in alternating days, excluding the rainy ones. Each Observation day (ODay) consisted of 5 Observation rounds (ORound): from 09 a.m. to 10 a.m., 11 a.m. to 12 a.m., 01 a.m. to 02 p.m., 03 p.m. to 04 p.m., 05 p.m. to 06 p.m. Each ORound consisted of 3 time-samplings of 15 minutes, one for each Zone and 5 minutes to rotate. During each time-sampling the observer was positioned in the best viewing location and eventually was moving in order to cover the whole zone.

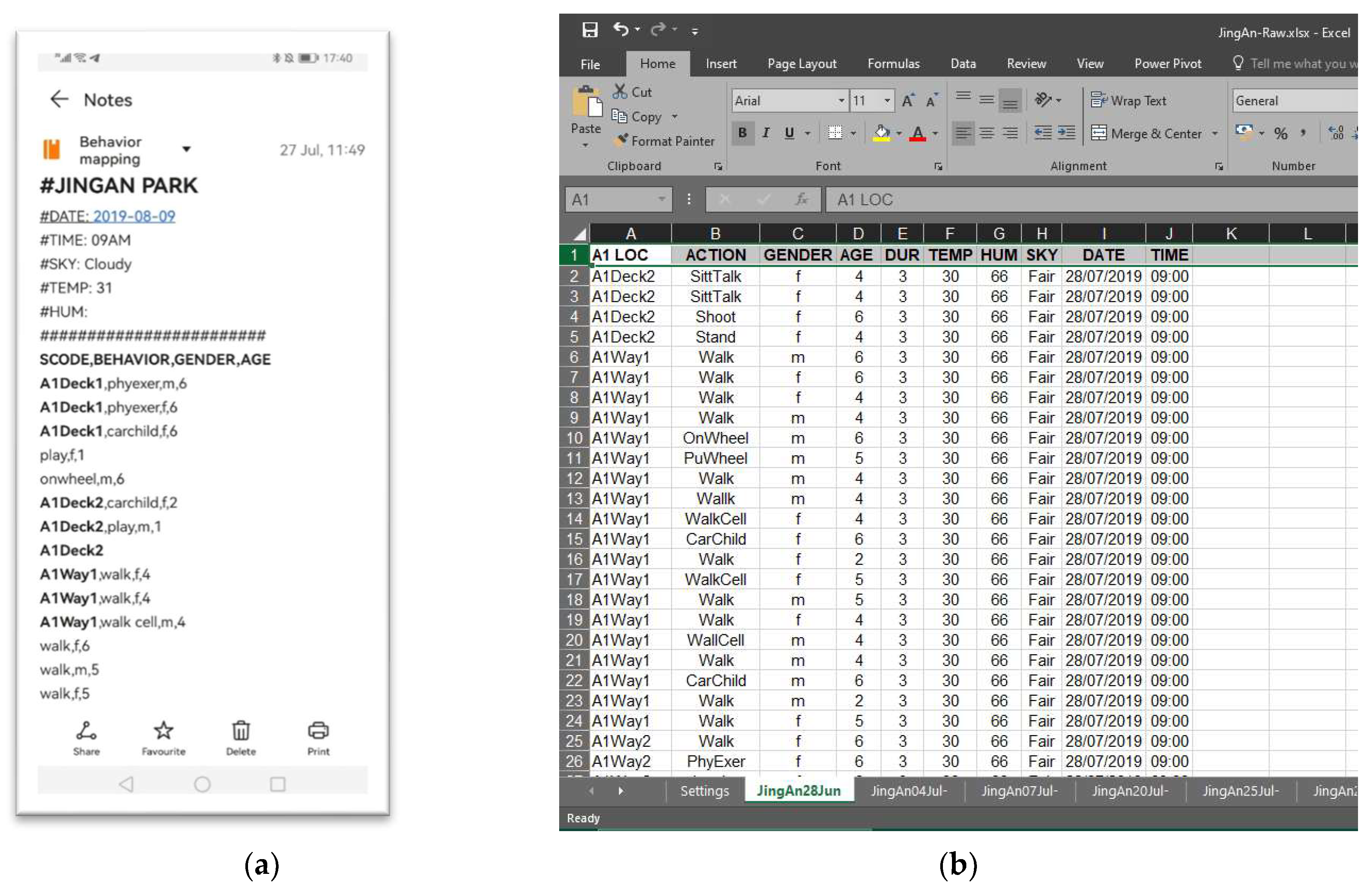

Observations were digitally recorded on a pre-formatted text note app in a smartphone, according to the figure 5a. Considering the density of users and therefore synchronic activities in the downtown parks during the summer, this method showed to be more suitable for fast and easy data collection than GIS applications. The pre-formatted note file for each park contained the site identification, context data (date, time, weather) and the settings for each zone represented by its respective setting code (SCode). Each user observed during the 15 minutes time-sampling represents one line in the text note, added in the form of the behavior category code, gender and age. In the example of figure 5, the behavior setting coded as “A1Deck1” and all others in bold, were part of pre-formatted note file. For example, the set of characters "phyexer,m,6" meant that a male user, aging 50-60 years old, was observed performing physical exercises in the architectural setting coded as A1Deck. In the note file each SCODE was written in 3 lines and activities that exceed 3 occurrences on a given setting were added through text typing a new line below. Later formatting was needed for a comprehensive tabulation of data in Microsoft Excel, as shown in figure 5b.

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Statistics of Behavior Mapping

The table 1 show the data collected through BM in all the nine Zones, grouped and named according to the name of its respective park. Behavior codes (BCodes) with its corresponding descriptions represents all types of behaviors observed, which summed 60 (sixty) different types. They range from extremely high occurrence activities such as walking, to extremely low ones, as listening a portable radio device or reading on a tablet. It is important to mention that, in this study, the behavior “walking” is an imprecise category, since it encompasses a diverse group of behavior, such as fast pace individuals using the park as a shortcut, slow walkers chatting to each other, appreciating the landscape or even doing a relaxing activity during a work break. In the case of other categories, they were straightforwardly interpreted and therefore, indubitable characterized.

The entire dataset collected comprises a total of 10801 observed activities, here divided as following; Xujiahui Park (n = 3409), Renmin Park (n = 4111) and Jing’An Park (n = 3280), being each observed activity corresponding to a single individual performing a type of activity at the 15 minute time-sampling. During this time interval, an individual can keep a single type of activity, or can start a different one, adding more occurrences to the observation note. Renmin Park presented the bigger number of incidences, counting with 38.10% of the activities. This can be explained by a variety of factors such as location in the core of downtown, touristic importance and cultural significance especially to domestic users. Xujiahui and Jing’An parks presented a lower number of occurrences with 31.60% and 30.40% respectively.

In our study, we observed a high variability of specific activities across the three distinct cases. Certain variables manifested consistently in some cases while being entirely absent in others. For instance, “SitBook” (sitting and reading a book) was present in in the zones observed in Xujiahui and Jing’An, but was not observed in Renmin. Conversely, “PFeedB” (playing of feeding birds) was unique to Xujiahui, and “FeedF” (feeding fish) was observed exclusively in Renmin, showing no occurrence in the others. This differential presence highlights the contextual dependencies and variability inherent in our study subjects, underscoring the need for a nuanced analysis of each case. “WaCall” (Walking while in a cellphone call) had considerable more occurrences in Jing’An Park while “CChild” (Taking care of a child) and “Play” (Playing) in Xujiahui has more than twice the number of occurrences observed in the other two parks. Nothing can be affirmed regarding the first case but the fact that Xujiahui presented not just more adults taking care of children but also more individuals playing (in the most cases children or young teenagers) contributes to the assumption of Xujiahui being more family friendly park. Another notable variability in the data regards to the number of individuals shooting the park area with photography cameras (digital single lens reflex or mirrorless). The extreme difference from Renmin to the others can be explained because during the observation days, the pond in the park is loaded with red lotus in full bloom, traditionally attracting large groups of photography hobbyists. Even though Xujiahui Park also has a water body with lotus flowers, occurrences on similar level were not observed. Some other occurrences in Renmin Park are clearly higher comparing to the others: singing, playing a music instrument, singing and recording with a cellphone, i.e., activities related to acoustic arts, which can be related with the existence of a street band, daily performing folk Chinese songs in the pond area. The variables to playing or watching table games and reading a news board (respectively “PTGa”, “WTGa” and “RNews”) were not observed on Xujiahui given that this type of news board was not found at the observed zones and there was not a specific settings to play cards, go or Chinese domino, such as the ones in Renmin and Jing’An. Inversely, just in Xujiahui was observed “PFeedG” (People playing to feed the gooses), as just there was observed gooses close to the water body. Also in Xujiahui, “ShootC”(Shooting cats) were much more frequently observed, and “Sleep” (Taking a nap) had more occurrences probably as a consequence of the subway station upgrade (Jing’An Station) happening close to the park and being used by occasional workers, specially the secluded and sheltered spot in the observation zone 3, located away from the crowded areas. The same case could be observed for Jing’An Park’s variable “SiTable” (Sitting at a table), due the existence of a restaurant with outdoor tables close to the lake, while in the other parks there were no restaurants or eatery venues close to the observed zones. Jing’An observation zones also were the only ones with the absence of dancing (dance), in this case, because dancing and most of artistic performances used to happen in another setting, not considered feasible for a single observer.

4.2. Demographic Characterization of Users: Age and Gender

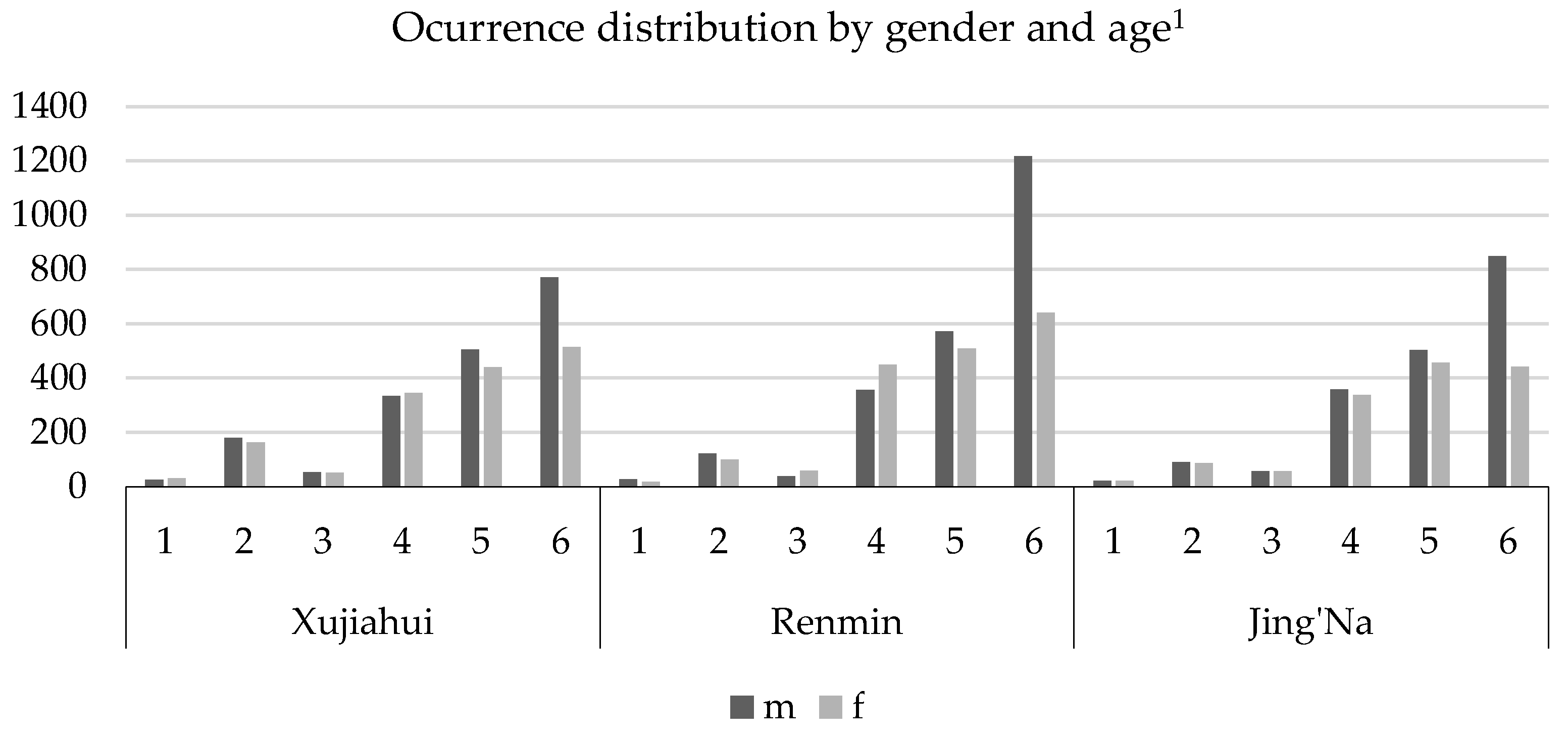

Figure 6 presents a demographic description of park users, specifically classified by age and gender, according to the data collected by BM in the nine Zones of the study area. The table consists of six age categories (1 to 6), with distinct columns for the frequency of male (m) and female (f) instances. The age group with the highest frequency in Xujiahui is category 6, with 770 males and 514 females. Conversely, the age category with the lowest frequency is category 1, with 25 males and 31 females. Renmin exhibits a comparable pattern, with the most frequent instances found in age group 6 (1218 men and 640 females) and the least frequent in age group 1 (27 males and 18 females). Jing'An exhibits a similar trend, with the most frequent instances observed among elders (849 males and 441 girls), and the least frequent instances observed in among infants (21 males and 22 females). This data illustrates the distribution of park utilization among different age groups and genders, revealing a greater predominance of older users in all the observed zones of the parks, and the predominance of females in through all the six categories. It is also worth to note that the number of users tend to grow with the age, with a clear exception for users in the category 3 (adolescents).

4.3. Temporal Characterization of Activities

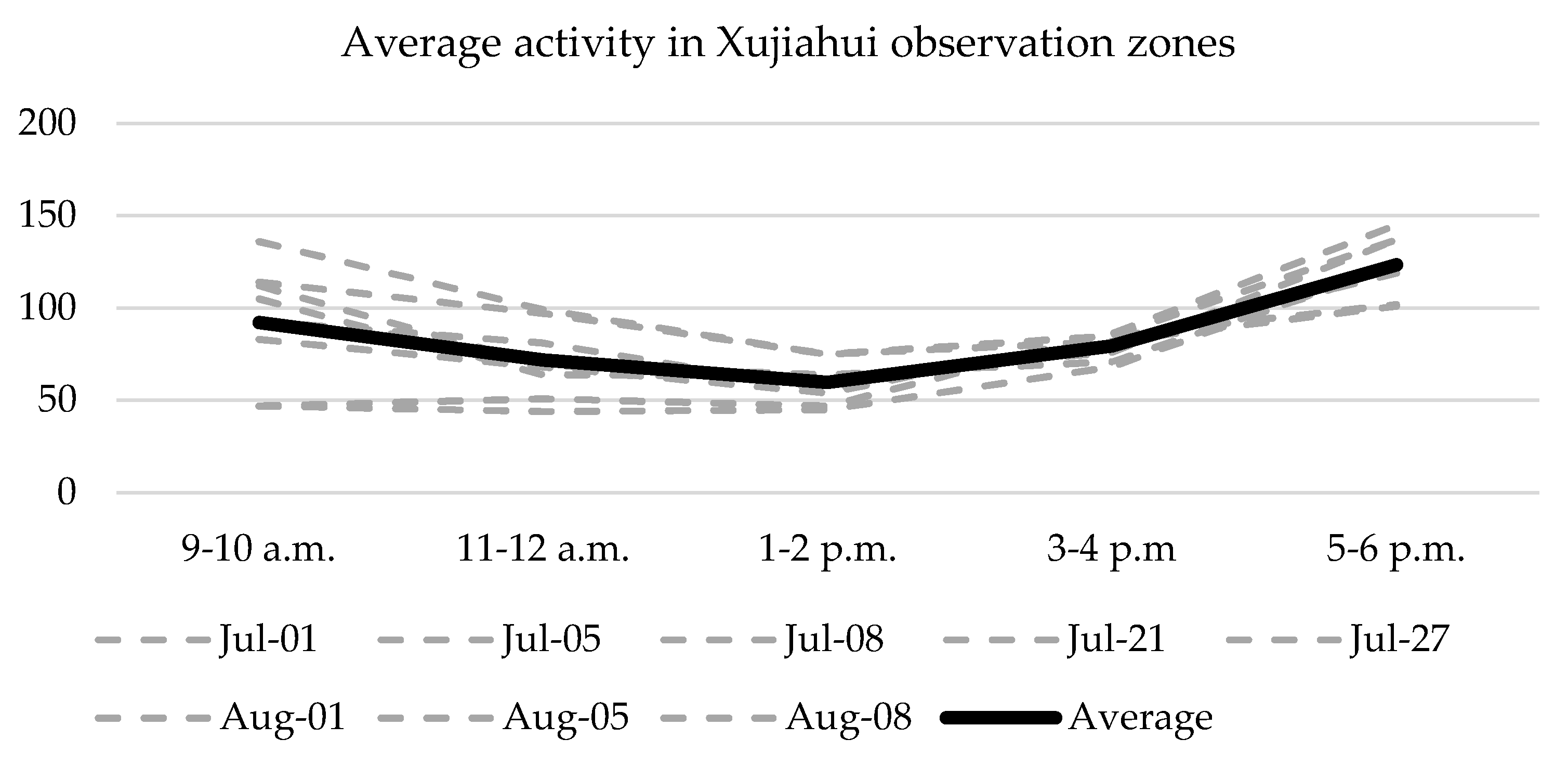

Figure 7 presents a detailed account of activity occurrences in the three observed zones of Xujiahui Park, recorded at five distinct observation sessions (9-10 a.m., 11-12 a.m., 1-2 p.m., 3-4 p.m., and 5-6 p.m.) across eight specific dates from July 1st to August 8th. The data reveal significant temporal variations in park attendance. The 9-10 a.m. interval shows an average of 92.125 users, with a notable peak of 136 users on July 5th and a low of 47 users on both August 5th and 8th. The 11-12 a.m. slot has a lower average of 71.625 users, with the highest count of 99 on July 5th and the lowest of 44 on August 5th. The 1-2 p.m. interval, which records the lowest average attendance at 59.875 users, shows relatively consistent low counts, peaking at 75 users on both July 1st and 5th. The 3-4 p.m. slot has a slightly higher average of 79.25 users, with counts ranging from 68 to 86 users. The 5-6 p.m. interval exhibits the highest average attendance at 123.375 users, with a peak of 145 users on August 8th and a low of 101 on July 5th. These findings suggest that user numbers in the observed zones are highest in the late afternoon, particularly from 5-6 p.m., and lowest during the early afternoon, from 1-2 p.m.

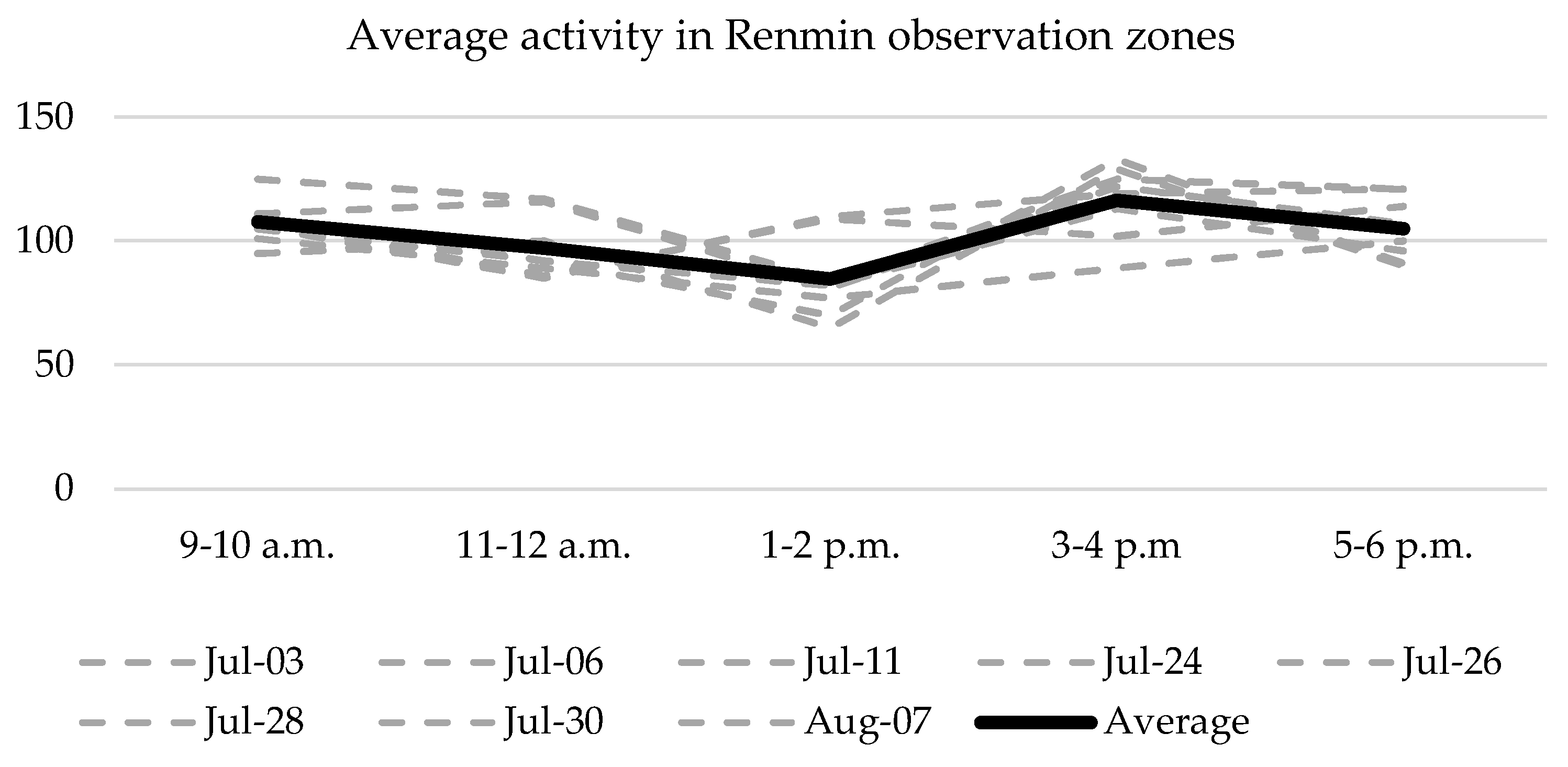

Figure 8 presents the recorded activity occurrences in the three observed zones of Renmin Park, recorded over a series of dates and specific one-hour intervals from July 3rd to August 7th. Data was collected at five distinct time slots: 9-10 a.m., 11-12 a.m., 1-2 p.m., 3-4 p.m., and 5-6 p.m. The data revealed temporal patterns in park usage. The 9-10 a.m. slot shows a consistent occurrence range of 95 to 125, with an average of 107.625, indicating steady morning attendance. The 11-12 a.m. slot exhibits greater variability, with counts from 85 to 117 and an average of 97.125, suggesting a slight decrease as the morning progresses. The 1-2 p.m. interval has the lowest average count at 84.75, possibly due to higher temperatures or lunchtime activities. In contrast, the 3-4 p.m. slot has the highest average count at 116.5, peaking at 133 on July 24th, indicating increased attendance in the late afternoon. The 5-6 p.m. interval shows a moderate average of 105, probably capturing the tendency to leave the park before evening. Overall, the data indicate distinct park usage patterns, with peak visitation in the late afternoon (3-4 p.m.) and the lowest during early afternoon (1-2 p.m.).

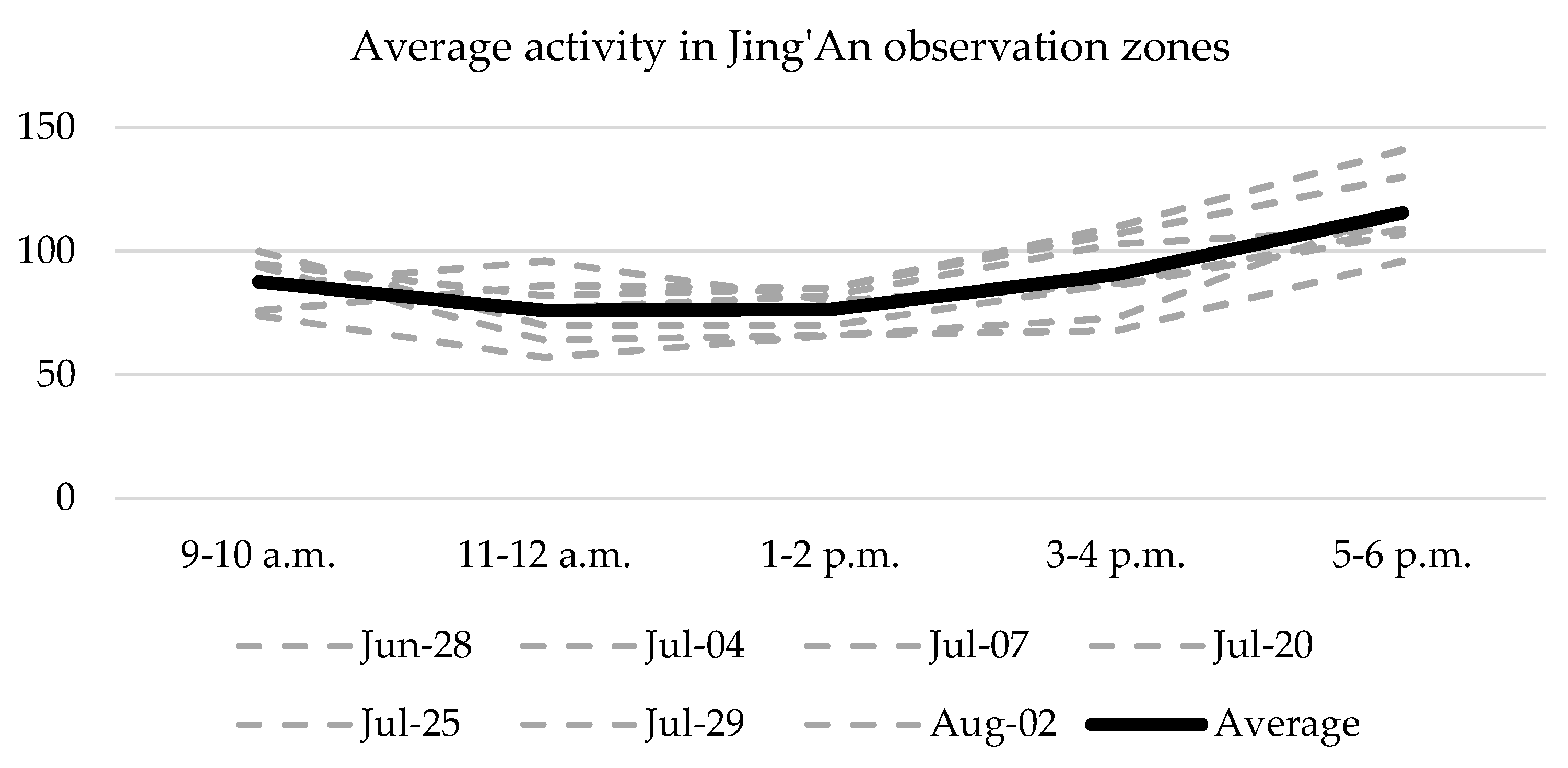

Figure 9 provides a detailed user counts in the three observation zones of Jing’An Park, recorded at five distinct one-hour intervals (9-10 a.m., 11-12 a.m., 1-2 p.m., 3-4 p.m., and 5-6 p.m.) across seven specific dates from June 28th to August 2nd. The data reveal the temporal variations in activity occurrences. The 9-10 a.m. interval shows an average of 87.57 users, with a peak of 100 users on July 25th and a low of 74 on August 2nd. The 11-12 a.m. slot has an average of 76 users, with the highest count of 96 on June 28th and the lowest of 57 on August 2nd. The 1-2 p.m. interval records an average attendance of 76.29 users, with consistent counts peaking at 85 on June 28th and July 4th. The 3-4 p.m. slot has a higher average of 90.57 users, with a peak of 110 on July 4th and a low of 68 on July 29th. The 5-6 p.m. interval exhibits the highest average attendance at 115.57 users, with a peak of 141 on July 4th and a low of 96 on July 29th. Similarly to Xujiahui, these findings suggest that activity is highest in the late afternoon, particularly from 5-6 p.m., and lowest around the mid-day, from 11-12 a.m., indicating potential patterns in park usage closed related to the daily average temperature, and possible to early evening activities like square dancing in Xujiahui.

4.4. Spatial Characterization of Activities

In order to better manage the information related to the physical characteristics of the study area, each spatial setting represented by its Setting Code, of all nine observed Zones, were methodically classified according to six basic functions (Setting Function): Walkway, Pathway, Rest, Scenic, IND (Indeterminate), and Inform.

Every category has a unique function; Walkway category includes environments specifically created to aid the conduct the users between the primary sections of the park. These spaces are sufficiently spacious to support a large number of people walking, and are generally equipped with benches, lights, and landscaping features that improve the overall walking experience. Pathways function as auxiliary connectors within the park, linking specific locations to the primary walkways or other important regions. Pathways, in contrast to wider walkways, are typically narrower and can encompass trails, footpaths, and bridges. These settings leads users into less frequented areas of the park. Pathways frequently cross through lawns, gardens or orchards, offering users the chance to interact with the park's features in a quieter setting. The Rest category comprises settings explicitly intended for rest, relax or recover from physical activities for example. These locations are furnished with amenities such as seats, pergolas, and picnic tables, encouraging people to stop, rest, and appreciate their environment. Scenic areas are intentionally created to emphasize the park's visual and aesthetic attractiveness. These settings are typically positioned to offer expansive views of prominent features such as lakes, gardens, lawns, monuments, and other notable sights. The scenic settings are carefully designed and located to improve the user's sensory experience and enhance the park's distinctiveness and appeal. They correspond to observation decks, terraces, seasonal gardens or viewing platforms. The IND (indeterminate) category consist of settings which functions are not precisely clear. These locations encompass courts, open spaces, plazas, and other multipurpose spaces. IND settings provide versatility in its use, accommodating a range of activities including physical exercise, group gathering or playing. The imprecise characteristics of these environments permit flexible utilization, accommodating the ever-changing requirements of diverse types of users and offering areas that can develop and transform as time progresses. Inform settings are specifically designed to facilitate the distribution of information within the park. These places commonly include features such as bulletin boards, information kiosks and signage. Information settings are carefully positioned at crucial entrances and crossroads around the park, guaranteeing that users may easily obtain essential information regarding park events, regulations, and mainly local news. The

Table 2 shows how the Setting Codes were classified into the six Setting Functions.

The

Table 3 presents observational data describing activities across the six different Settings categories showed in the table 6: Indeterminate (IND), Walkway, Pathway, Scenic, Rest and Inform areas. The activities observed are showed by the number of different activity occurrence and the overall number of occurrences in each group of three observed zones . Within Xujiahui Park, IND settings displayed a total of 26 unique observed activities, in a total of 379 occurrences. The Walkway areas had 21 different types of activities, with a significant number of 1,323 occurrences. In contrast, the Pathway areas had 18 forms of activities, with a significant small number of 261 occurrences. The Scenic locations in Xujiahui exhibited 17 different types of activity, with a total of 285 occurrences. On the other hand, the Rest areas, which are known for their high activity diversity, saw 36 types of behavior, totaling 1,161 occurrences. There were no identified activities in the Inform category for Xujiahui. Renmin Park has 20 distinct activity pattern and 253 instances in the IND scenario. The Walkway regions exhibited 17 distinct types, with a greater frequency of 1,381 incidences. The observation zones in Renmin also exhibited the greatest diversity in Pathway areas, with 33 distinct types of activities and a frequency of 1,132 occurrences. There were 20 different in Scenic settings, with a total of 273 instances. In contrast, Rest areas had a variety of 18 types of activities but a significantly higher number of occurrences, totaling 1,061. In the Renmin data set, the Inform category showed a single behavioral type that occurred 14 times. Finally, Jing'An Park exhibited a distinct configuration compared to the other two, where the IND setting displayed 4 distinct categories and 10 incidences. The Walkway areas were found to be the most busy location, with 41 different forms of activities observed and a total of 1,449 times. The Pathway areas consisted of 22 distinct types and were seen a total of 187 occurrences. The Scenic locations displayed a total of 29 distinct types, with a combined occurrence count of 539. On the other hand, the Rest areas consisted of 39 different types, with a total occurrence count of 1,094. For the Jing'An Park, the Inform setting is associated to 7 distinct activities, each occurring 14 times.

The data presented in the

Table 3 allows for the formulation of key assumptions regarding space appropriation in the studied UGS. A diverse range of activities indicates its flexibility and capacity to meet varying user needs, reflecting a high probability of appropriation. The presence of multiple activities demonstrates how individuals adapt the space to suit their own purposes, embedding it into their daily routines. Moreover, the total number of activity occurrences serves as an indicator of the frequency and intensity of use, with higher occurrences suggesting the space is deeply integrated into the social and cultural practices of the community, further reinforcing its significance to users.

5. Discussion

The objective of this research is characterize the use of space at UGS in downtown Shanghai from the perspective of space appropriation. The comprehensive analysis conducted mainly by non-participant observation and behavior mapping allowed to record a significant and consistent group of activities through the nine different Zones observed. This discussion will address the three research questions based on the data showed in the results section; 1) the characterization of uses based on user demographics, spatial and temporal description of activities, 2) try to establish a relationship between intensity, diversity and appropriation and 3) identify levels of appropriation in the studied area.

5.1. Characterization of Users

In relation to the demographic data collected about the users, all the three parks showed similar distribution between males and females along different age categories, with exception to the elder ones, showing a significant higher amount of males using the parks, specially the areas within Renmin Park. This corroborates the findings of Wang and Wu [

18] who showed a prevalence of elderly males in downtown parks, but diverge from the work of Liu [

19], who stated that adult females were the majority of users. Another notable finding common to all observed areas were the low levels of adolescent (10 to 19 years). The empirical observation showed that majority of adolescents in the study areas tend to engage with few settings, being their favorite the ones with appealing background or interesting subjects to compose a selfie. Further studies must be conducted in order to confirm the reasons, but since their behavior involves an electronic device as intermediary, possible design solutions based on hybrid and interactive spaces to attract adolescents could be a topic of inquiring for future research.

The observational data also provided valuable insights into the temporal patterns of use of space. The analysis of user counts across different time intervals and dates revealed distinct trends that can inform park management and resource allocation strategies. The data from all three parks consistently showed a peak of activity in the late afternoon, particularly during the 5-6 p.m. interval. This trend is evident in Xujiahui Park, where the highest average attendance of 123.375 users was recorded during this time slot, with a peak of 145 users on August 8th. Similarly, Renmin Park and Jing’An Park exhibit their highest average attendances during the 5-6 p.m. interval, with averages of 105 and 115.57 users, respectively. This late afternoon peak likely reflects a combination of factors, including more favorable weather conditions, especially if considering that the data collection happened in August and September of 2019, with temperatures reaching 33°C at midday. Other possible reasons contributing to the rise of users around 5-6 p.m. are the end of the workday and the availability of leisure time for park users. Conversely, the early afternoon period, particularly the 1-2 p.m. interval, consistently shows the lowest average user counts across all three parks. Xujiahui Park records an average of 59.875 users, Renmin Park 84.75 users, and Jing’An Park 76.29 users during this time slot. This decline in attendance may be attributed to higher midday temperatures, lunchtime activities, or other competing commitments that deter park visits during this period.

The analysis of the physical settings in the study area focused on how setting categories such as Walkway, Pathway, Rest, Scenic, IND (indeterminate), and Inform correlate with usage patterns. To compared with other studies can be a difficult task, since each author use its own categories, such as “Water”, “Plaza”, “Lawn”, “Architecture” [

18], or more specific terminologies [

17,

19], even though the overall structure of UGS are similar. In our case, grouping the different settings types into setting functions permitted to establish a common characteristic to each group, facilitating the analysis; Walkway and Pathway being the group essential active park movement and connectivity. Rest settings like benches afford passive activities as relaxation, while Scenic spots such as water fountain and bridges afford visual enjoyment. These spaces, though limited in number, encourage prolonged stays, promoting social interaction and mental restoration. IND (indeterminate) settings, such as courts in Xujiahui and in Renmin support multifunctional use, from recreational activities to social gatherings. Inform play a smaller but significant role in user orientation and information.

5.2. Appropriation Based on Diversity and Intensity of Activities

The analysis of the observational data revealed significant insights into how different settings are utilized by users. The ideas of spatial vitality and spatial appropriation are inextricably linked since appropriation frequently serves as a precursor to vitality in urban settings. Gehl affirms that appropriation typically results in vitality, or the active use of a space through a variety of activities and interactions [

52,

53].

Accordingly, we can affirm that a high number of occurrences and a diverse range of activity types in a given setting are an indicative of appropriation. Considering that vitality can be expressed as the ratio of the activity types to the number of occurrences, we can mathematically express it in a form of equation. Higher vitality values indicate settings where a diverse range of activities occurs frequently, suggesting these areas are more versatile and engaging for users. The weighted formula for calculating spatial vitality is designed to quantify the dynamic use of urban spaces by considering both the diversity and frequency of activities:

where (

Wi ) represents the vitality index for a given setting category (

i ), (

Ti ) is the number of activity types observed in the setting category (

i ), and (

Oi ) is the number of occurrences of these activities. (

Tmax ) and (

Omax ) are the maximum values of activity types and occurrences across all settings, respectively. The exponent (0.5) is a weighting factor that balances the influence of occurrences. This formula ensures that settings with a higher ratio of diverse activities to occurrences are assigned a higher vitality index, reflecting their greater potential to be appropriated in some level. The

Table 4 present the vitality indicators for each setting category.

Walkway settings shows the higher values of vitality in Jing’An but moderate values in Xujiahui and Renmin, despite their high number of occurrences. This suggests that in the case of these two parks, while walkways are heavily used, the range of activities is somewhat limited compared to the frequency of use. Walkways are essential for connectivity and movement, but their potential for diverse activities might be constrained by their primary function as transit routes. Rest settings exhibit higher vitality values, indicating a greater diversity of activities relative to their occurrences. These settings are multifunctional, providing spaces for relaxation, socialization, and passive recreation. The high vitality values highlight their versatility and importance in enhancing the user experience. Scenic settings show the mid-low vitality values. This indicates that these areas area limiting the variety of activities, probably due its lower number of occurrences. Scenic settings are designed for visual enjoyment and sightseeing, attracting diverse activities such as photography, contemplation, and social gatherings. Their low vitality values should be put in scrutiny, especially because these areas should create engaging and attraction. Pathway settings, particularly in Renmin Park, show high vitality values, while low in the others. This suggests that in Renmin, pathways, while primarily designed for connectivity, also support a diverse range of activities. Their narrower and more intimate nature compared to walkways might encourage varied uses, which can be confirmed by future comparative analysis such as Post-Occupancy Evaluation (POE) or Performance-based Evaluation [

38,

40]. IND settings are low and exceptionally very low in vitality at Jing’An probably because its small number of occurrences. Finally, as expected, Inform settings shows the lowest vitality values due its limited type of activity combined to low occurrences, which can be explained by the utilitarian nature of this settings.

Overall, the role of the vitality indicator in our work is two-folded: It can be understood as an indication of appropriation, as suggested by the literature, and as a tool to demonstrate validity. In this case, the analysis of appropriation in the observed area must be compared to the values of vitality for each setting category.

5.3. Analysis of Appropriation

According to the theoretical framework presented in the item 2, the idea of appropriation do not have a consensual interpretation [

30,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35,

36,

37]. Reviewing key authors whose works were related to this topic, we can conclude that the concept of appropriation ranges from a low level (Soft Appropriation) when psychological identification bonds the subject to the object, to a High Appropriation Level when the subject could take ownership of the object. In order to use the concept of appropriation as an analytical category within the study area, it is necessary to stablish a clear framework.

Table 5 presents our understanding of the concept of appropriation according to the authors studied. The range of interpretation permitted to categorize the concept into different classes of appropriation, as shown in the first column. The second column shows the corresponding authors for each type of appropriation and in the third column the main idea according to our interpretation. Following, we classified the types of appropriation from soft, moderate and high appropriation, corresponding to Appropriation Level (AL) 0 (utilitarian use), to AL7 (customized space). Temporary illegal ownership of the space (what many authors consider as an extreme case of appropriation, and in this study classified as “Undesirable” (UN), received a grade zero. Finally, the last column presents a rating to each appropriation level. The scale of this rating vary in geometric progression with a common ratio of three (

r = 3). This geometric progression offers an exponential way to represent the spread of levels, matching the theoretical notion of appropriation levels that starts with small changes between the initial levels, ending with significant gaps between the last levels.

With the types of use characterized as Appropriation Levels and their corresponding rating, we can classify the activity category according to an AL and assign values to each of them. For this classification, we stablished a structured method to ensure reliability and validity [

54]. The data was collected by note taking at the same time of running the behavior mapping (summer of 2019). Inter-Rater Reliability to minimize bias was achieved with the assistance of three trained researchers (one PhD and two master students). They first run a pilot test on a limited set of data where each activity was written in a card, with additional information such as frequency, duration and examples. The complete classification of the sample, totalizing the sixty different activities (n = 60) is represented in the

Table 6. It is worth to mention that the trained coders required to create a new intermediary class, (FuSa), representing activities considered in between the appropriation of Functional/Utilitarian space, and soft appropriation. This category was rated with the grade 1.5.

The table 7 is an effort to representing appropriation of space through an index called here “Appropriation Score.” The score is calculated straightforward utilizing the AL Grade from

Table 6, addressed to each of the activity type of a setting category. For the setting category IND in the observed zones of Xujiahui Park, it was observed 22 different types of activities, according to table 7. Each of these activities received a grade according to the classification represented by

Table 5. The appropriation score is the sum of all 22 grades. In Xujiahui, the biggest scores were in the Rest and IND, followed closely by Walkway settings, while Pathway showed the lower score. In Renmin, Pathway and IND settings presented the higher scores and Walkway the lower. In Jing’An, Walkway and Rest scored the highest number, as in Xujiahui, while IND settings scored as the lower.

The vitality indicator of

Table 4 validates the framework. It corroborates the scores presented in the

Table 7, since 4 out of 6 higher indicators match with the higher scores.

Our findings indicates a tendency, where users tend to appropriate settings with no clear function (courts, opens spaces, corners) and rest areas (pergolas, pagodas, seats, openings in the greenery). With the exception of the Walkway in Jing’An, both of them are not part of the main Walkways, where most of the users follows the main flow.

In general, it is possible to conclude that appropriation of space manifest in the study area under low to mid levels (FuSa to AL5). This can be explained by the fact of all nine Observation Zones being located within Comprehensive parks in downtown. These mostly ordered spaces, being massively visited in a daily basis, require regulations and norms to offer a sense of organized calm in the core of the metropolis, especially considering their symbolic capital as part of main touristic spots in Shanghai. Future research is needed in different types of UGS such as neighborhood and community parks, to keep testing the methodology and to understand which design strategies have been producing stronger bonds between the user and the space.

5.4. Methodological Considerations

Compared to similar works about the use of space in UGS [

17,

18,

19,

20], the current study unveiled several types of activities and occurrences as well. Even though this can be related to the effectiveness of behavior mapping as main source of data collection, we believe that how BM was applied had the main impact on the diversity and number of occurrences collected. Most of studies used GIS apps on tablets to collect data, while we run our data collection using a text editor in a mobile phone. A previous pilot round of BM using GIS app in a tablet showed to be less effective than collecting data through digital note taking in a mobile phone, since the study area is a crowded touristic spot. For this reason we decided to keep the original method of note taking, as preconized by Ittelson [

47].

Another point, related to the types of activities, which were considerable homogeneous through the three parks indicates a satisfactory level of research reliability, but also can be related to the fact that the observed parks were Comprehensive Parks. Therefore, the difference to previous studies relates to the difference of studies cases, since they can belong to different categories of UGS. For example, trim vegetables, embroidering or play Chinese swords were recurring activities in neighborhood parks [

17,

18], but not observed in our study area.

Finally, in the study of physical settings, categorizing spaces into Walkways, Pathways, Rest areas, Scenic spots, IND and Inform revealed a need for a structured classification system (or an ontology) not just for UGS settings but also types of activities. An ontology, in this context, refers to a formal framework that systematically defines and relates various concepts within a domain. For UGS, this would involve creating a comprehensive and common vocabulary, allowing researchers to conduct objective comparative studies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.M. and Z.W.; methodology, S.M.; software, S.M.; validation, S.M.; formal analysis, S.M.; investigation, S.M.; resources, Z.W.; writing—original draft preparation, S.M.; writing—review and editing, Z.W.; visualization, S.M.; supervision, Z.W.; project administration, Z.W.; funding acquisition, Z.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The RAW data supporting the conclusion of this article will be made available by the authors by request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Chen, L.; Liu, L.; Wu, H.; Peng, Z.; Sun, Z. Change of Residents’ Attitudes and Behaviors toward Urban Green Space Pre- and Post- COVID-19 Pandemic. Land 2022, 11, 1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, A.; Cenci, J.; Zhang, J. Links between the Pandemic and Urban Green Spaces, a Perspective on Spatial Indices of Landscape Garden Cities in China. Sustainable Cities and Society 2022, 85, 104046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noszczyk, T.; Gorzelany, J.; Kukulska-Kozieł, A.; Hernik, J. The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on the Importance of Urban Green Spaces to the Public. Land Use Policy 2022, 113, 105925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, S.; Xie, J.; Furuya, K. “We Need such a Space”: Residents’ Motives for Visiting Urban Green Spaces during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, J.; Luo, S.; Furuya, K.; Sun, D. Urban Parks as Green Buffers During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, C.; Sanesi, G. COVID-19 and the Importance of Urban Green Spaces. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening, 2765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertram, C.; Rehdanz, K. The Role of Urban Green Space for Human Well-Being. Ecological Economics 2015, 120, 139–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, P.; Banay, R. F.; Hart, J. E.; Laden, F. A Review of the Health Benefits of Greenness. Current Epidemiology Reports 2015, 2, 131–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shuvo, F. K.; Feng, X.; Akaraci, S.; Astell-Burt, T. Urban Green Space and Health in Low and Middle-Income Countries: A Critical Review. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening, 2666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jennings, V.; Bamkole, O. The Relationship between Social Cohesion and Urban Green Space: An Avenue for Health Promotion. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2019, 16, 452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.; Jia, Z.; Zhou, Z. Can Urban Green Space Cure Homesickness? Case Study on China Poverty Alleviation Migrants in Anshun, Guizhou. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening, 2747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Yang, J.; Ma, L.; Huang, C. Factors Affecting the Use of Urban Green Spaces for Physical Activities: Views of Young Urban Residents in Beijing. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening. [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Lu, S.; Hu, S. Assessing the Public Recreational Space in the Urban Park from the Psychological and Behavioral Aspects, a Case Study of Quyuan Park, Hangzhou, China. In: Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference On Systems Engineering and Modeling 2013. [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Luo, W.; Li, H.; Zhang, D.; Kang, N.; Yang, X.; Xia, Y. Impact of Perception of Green Space for Health Promotion on Willingness to Use Parks and Actual Use among Young Urban Residents. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2020, 17, 5560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xue, F.; Gou, Z.; Lau, S. The Green Open Space Development Model and Associated Use Behaviors in Dense Urban Settings: Lessons from Hong Kong and Singapore. URBAN DESIGN International 2017, 22, 287–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, L.; Cui, L.; Wu, M. Tourist Behaviors in Wetland Park: A Preliminary Study in Xixi National Wetland Park, Hangzhou, China. Chinese Geographical Science 2010, 20, 66–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, F. , Wu, C. , Wall, F., Li, Canada and China. In Proceedings of the 47th ISOCARP Congress, Wuhan, China, October 24-28, 2011., C. Comparison of Urban Resident’s Use and Perceptions of Urban Open Spaces in USA.

- Wang, X.; Wu, C. An Observational Study of Park Attributes and Physical Activity in Neighborhood Parks of Shanghai, China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 2080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, M.; Chen, C.; Yan, J. Identifying Park Spatial Characteristics That Encourage Moderate-to-Vigorous Physical Activity among Park Visitors. Land 2023, 12, 717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Qiu, M.; Chen, M.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, S.; Wang, L. How Does Urban Green Space Feature Influence Physical Activity Diversity in High-Density Built Environment? An On-Site Observational Study. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening, 2712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lefebvre, H. The Production of Space; Blackwell: London, England, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- De Certeau, M. The Practice of Everyday Life, 3rd ed.; University of California Press, 2011.

- Sennett, R. L: Uses of Disorder: Personal Identity and City Life; Verso Books, 2021.

- Tuan, Y.-F. Space and Place; University of Minnesota Press: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Relph, E. Place and placelessness. London: Pion, 1996.

- Augé, M. Non-Places: An Introduction to Supermodernity; Howe, J., Translator, *!!! REPLACE !!!*, Eds.; Verso Books: London, England, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Norberg-Schulz, C. Genius Loci: Towards a Phenomenology of Architecture; Rizzoli: New York, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Cresswell, T. Place: A Short Introduction; Blackwell Publishing: Malden, MA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Low, S. M.; Altman, I. (Eds.) Place Attachment; Springer: New York, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper-Marcus, C. House as a mirror of self: Exploring the deeper meaning of home. New York, Conari Press, 1995.

- Leontyev, A. N. The Development of Mind: Selected Works of Aleksi Nikolaevich Leontyev; Marxists Internet Archive Publications, 2019. Available online: https://www.marxists.org/admin/books/activity-theory/leontyev/development-mind.pdf (accessed on 18 February 2020).

- Korosec-Serfaty, P.; The Appropriation of Space. In P. Korosec-Serfaty (Ed.), Appropriation of space (Proceedings of the 3rd International Architectural Psychology Conference, Strasbourg, France, 1978. Available online: https://iaps.architexturez.net/documents/series/AP6 (accessed on 21 February 2020).

- Sansot, P.; Notes on the concept of appropriation. In P. Korosec-Serfaty (Ed.), Appropriation of space (Proceedings of the 3rd International Architectural Psychology Conference, Strasbourg, France, 1978. Available online: https://iaps.architexturez.net/documents/series/AP6 (accessed on 27 February 2020).

- Chombart de Lauwe, P.; Appropriation of Space and Social Change. In P. Korosec-Serfaty (Ed.), Appropriation of space (Proceedings of the 3rd International Architectural Psychology Conference, Strasbourg, France, 1978. Available online: https://iaps.architexturez.net/documents/series/AP6 (accessed on 28 February 2020).

- Pol, E. La apropiación del espacio. In L. Iñíguez, & E. Pol (Orgs.), Cognición, representación y apropiación del espacio. Barcelona: Universitat, 1996.

- Proshansky, H. M.; The appropriation and misappropriation of space. In P. Korosec-Serfaty (Ed.), Appropriation of space (Proceedings of the 3rd International Architectural Psychology Conference, Strasbourg, France, 1978. Available online: https://iaps.architexturez.net/documents/series/AP6 (accessed on 19 February 2020).

- Lara-Hernandez, J. A.; Melis, A. Understanding the Temporary Appropriation in Relationship to Social Sustainability. Sustainable Cities and Society 2018, 39, 366–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper Marcus, C.; Francis, C. People Places: Design Guidelines for Urban Open Space. Wiley and Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1997.

- Creswell, J.W. , & Clark, V.L. Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research, 2006.

- Bechtel, R.B.; Marans, R.; Michelson, W. Methods in Environmental and Behavioural Research; Van Nostrand Reinhold: New York, NY, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Shanghai Municipal Statistics Bureau. 2019 Shanghai Census Report; Shanghai Municipal People’s Government: Shanghai, China, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, S.; Du, S.; Yang, S.; Du, S. Functional Classification of Urban Parks Based on Urban Functional Zone and Crowd-Sourced Geographical Data. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2021, 10, 824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

-

Standard for Classification of Urban Green Space; China Building Industry Press: Beijing, China, 2019.

- Ciesielska, M. , Boström, K.W., Öhlander, M. Observation Methods. In Qualitative Methodologies in Organization Studies. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Smit, B. , & Onwuegbuzie, A.J. Observations in Qualitative Inquiry: When What You See Is Not What You See. International Journal of Qualitative Methods.

- Atkinson, P.; Hammersley, M. Ethnography: Principles in Practice, 3rd ed.; Routledge: London, England, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Ittelson, W.H.; Rivlin, L.G.; Proshansky, H.M. The use of behavioral maps in environmental psychology. In Environmental Psychology: Man and His Physical Setting; Proshansky, H.M., Ittelson, W.H., Rivlin, L.G., Eds.; Holt, Rinehart and Winston: New York, NY, USA, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Gehl, J.; Svarre, B. How to Study Public Life; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Project for Public Space (PPS). How to Turn a Place Around: A Handbook for Creating Successful Spaces; Project for Public Spaces, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Moore, R.C.; Cosco, N.G. Using behavior mapping to investigate healthy outdoor environments for children and families: Conceptual framework, procedures and applications. In Innovative Approaches to Researching Landscape and Health; Thompson, C.W., Aspinall, P., Bell, S., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Marušic, B.; Marušic, D. Behavioural maps and GIS in place evaluation and design. In Application of Geographic Information Systems; Alam, B.M., Ed. R: IntechOpen, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Gehl, J. Life between Buildings: Using Public Space, 6th ed.; Danish Architectural Press, 2008.

- Holland, C. , Clark, A., Katz, J., & Peace, S. Social interactions in urban public places, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Busetto, L.; Wick, W.; Gumbinger, C. How to use and assess qualitative research methods. Neurol. Res. Pract. 2020, 2020 2, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Location of the study area. (a) Location of Shanghai in China. (b) Location of downtown Shanghai. (c) Location of the three parks: 1) Renmin Park, 2) Jing’An Park and 3) Xujiahui Park.

Figure 1.

Location of the study area. (a) Location of Shanghai in China. (b) Location of downtown Shanghai. (c) Location of the three parks: 1) Renmin Park, 2) Jing’An Park and 3) Xujiahui Park.

Figure 2.

Observation Zones in Xujiahui Park.

Figure 2.

Observation Zones in Xujiahui Park.

Figure 3.

Observation Zones in Renmin Park.

Figure 3.

Observation Zones in Renmin Park.

Figure 4.

Observation Zones in Jing’An Park.

Figure 4.

Observation Zones in Jing’An Park.

Figure 5.

Data collection and tabulation. (a) Pre-formatted text note in a smartphone app. (b) Tabulated data in Microsoft Excel.

Figure 5.

Data collection and tabulation. (a) Pre-formatted text note in a smartphone app. (b) Tabulated data in Microsoft Excel.

Figure 6.

Distribution of users occurrences characterized by age and gender. 1Age categories: 1 = infant (0 - 1 year), 2 = children (2 - 9 years), 3 = adolescent (10 - 19 years), 5 = youth (15 - 24 years), 5 = adult (25 - 69 years), 6 = elderly (+65 years).

Figure 6.

Distribution of users occurrences characterized by age and gender. 1Age categories: 1 = infant (0 - 1 year), 2 = children (2 - 9 years), 3 = adolescent (10 - 19 years), 5 = youth (15 - 24 years), 5 = adult (25 - 69 years), 6 = elderly (+65 years).

Figure 7.

Activity level in Xujiahui Park in observation days.

Figure 7.

Activity level in Xujiahui Park in observation days.

Figure 8.

Activity level in Renmin Park in observation days.

Figure 8.

Activity level in Renmin Park in observation days.

Figure 9.

Activity level in Jing’An Park in observation days.

Figure 9.

Activity level in Jing’An Park in observation days.

Table 1.

Observed activities and their occurrence number in the study area.

Table 1.

Observed activities and their occurrence number in the study area.

| ACode1

|

Description |

All |

Xujiahui Park |

Renmin Park |

Jing’An Park |

| |

|

n=10,801 |

n=3,409 |

n=4,111 |

n=3,280 |

| |

|

Sum |

% |

Part.2

|

% |

Part. |

% |

Part. |

% |

| Walk |

Walking |

3,857 |

100.00% |

1,280 |

33.19% |

1,433 |

37.15% |

1,144 |

29.66% |

| Sit |

Sitting |

1,563 |

100.00% |

510 |

32.63% |

680 |

43.51% |

373 |

23.86% |

| SiCall |

Sitting + on a call |

743 |

100.00% |

273 |

36.74% |

260 |

34.99% |

210 |

28.26% |

| SiChat |

Sitting + chatting |

655 |

100.00% |

135 |

20.61% |

285 |

43.51% |

235 |

35.88% |

| Shoot |

Shooting with cell phone |

522 |

100.00% |

112 |

21.46% |

209 |

40.04% |

199 |

38.12% |

| WaCall |

Walking + on a call |

472 |

100.00% |

133 |

28.18% |

141 |

29.87% |

198 |

41.95% |

| CChild |

Taking care of child |

458 |

100.00% |

248 |

54.15% |

100 |

21.83% |

109 |

23.80% |

| Play |

Playing |

288 |

100.00% |

158 |

54.86% |

48 |

16.67% |

82 |

28.47% |

| Jog |

Jogging |

244 |

100.00% |

83 |

34.02% |

92 |

37.70% |

69 |

28.28% |

| PhExer |

Physical exercises |

198 |

100.00% |

61 |

30.81% |

41 |

20.71% |

96 |

48.48% |

| ShCam |

Shooting with camera |

198 |

100.00% |

8 |

4.04% |

188 |

94.95% |

2 |

1.01% |

| WTGa |

Watching table game |

169 |

100.00% |

0 |

0.00% |

101 |

59.76% |

68 |

40.24% |

| Stand |

Standing |

166 |

100.00% |

68 |

40.96% |

51 |

30.72% |

47 |

28.31% |

| ShSelf |

Shooting a selfie |

154 |

100.00% |

25 |

16.23% |

86 |

55.84% |

43 |

27.92% |

| PTGa |

Playing table game |

122 |

100.00% |

2 |

1.64% |

58 |

47.54% |

62 |

50.82% |

| Sing |

Singing |

108 |

100.00% |

6 |

5.56% |

102 |

94.44% |

0 |

0.00% |

| SiTable |

Sitting at a table |

86 |

100.00% |

0 |

0.00% |

15 |

17.44% |

71 |

82.56% |

| PFeedF |

Playing to feed fish |

78 |

100.00% |

53 |

67.95% |

25 |

32.05% |

0 |

0.00% |

| ChPr |

Child in a pram |

64 |

100.00% |

29 |

45.31% |

14 |

21.88% |

21 |

32.81% |

| PPram |

Pushing a pram |

61 |

100.00% |

26 |

42.62% |

14 |

22.95% |

21 |

34.43% |

| TaiChi |

Doing Tai Chi |

55 |

100.00% |

21 |

38.18% |

19 |

34.55% |

15 |

27.27% |

| Wheel |

On wheelchair |

51 |

100.00% |

7 |

13.73% |

16 |

31.37% |

28 |

54.90% |

| Portrait |

Shooting a portrait |

43 |

100.00% |

8 |

18.60% |

15 |

34.88% |

20 |

46.51% |

| Posing |

Posing to a portrait |

40 |

100.00% |

8 |

20.00% |

11 |

27.50% |

21 |

52.50% |

| PMInst |

Playing music instrument |

31 |

100.00% |

6 |

19.35% |

23 |

74.19% |

2 |

6.45% |

| PuWh |

Pushing someone's wheelchair |

31 |

100.00% |

6 |

19.35% |

7 |

22.58% |

18 |

58.06% |

| Sleep |

Sleeping/napping |

31 |

100.00% |

2 |

6.45% |

4 |

12.90% |

25 |

80.65% |

| StChat |

Standing + chatting to someone |

31 |

100.00% |

15 |

48.39% |

5 |

16.13% |

11 |

35.48% |

| PFeedG |

Playing to feed a goose |

27 |

100.00% |

27 |

100.00% |

0 |

0.00% |

0 |

0.00% |

| RNews |

Reading a news board |

25 |

100.00% |

0 |

0.00% |

14 |

56.00% |

11 |

44.00% |

| MoSco |

Moving on a scooter |

25 |

100.00% |

8 |

32.00% |

11 |

44.00% |

6 |

24.00% |

| Dance |

Dancing |

24 |

100.00% |

17 |

70.83% |

7 |

29.17% |

0 |

0.00% |

| SitBook |

Sitting + reading a book |

20 |

100.00% |

15 |

75.00% |

0 |

0.00% |

5 |

25.00% |

| PFeedB |

Playing to feed birds |

17 |

100.00% |

17 |

100.00% |

0 |

0.00% |

0 |

0.00% |

| ShFish |

Shooting a fish in the lake |

16 |

100.00% |

0 |

0.00% |

7 |

43.75% |

9 |

56.25% |

| StCell |

Standing on the cell phone |

15 |

100.00% |

3 |

20.00% |

3 |

20.00% |

9 |

60.00% |

| PScoot |

Playing with a scooter |

13 |

100.00% |

8 |

61.54% |

3 |

23.08% |

2 |

15.38% |

| FeedC |

Feeding cats |

11 |

100.00% |

2 |

18.18% |

0 |

0.00% |

9 |

81.82% |

| PLake |

Playing on lake margins |

9 |

100.00% |

1 |

11.11% |

2 |

22.22% |

6 |

66.67% |

| ShootC |

Shooting cats |

9 |

100.00% |

0 |

0.00% |

0 |

0.00% |

9 |

100.00% |

| SitMag |

Sitting + reading a magazine |

8 |

100.00% |

4 |

50.00% |

1 |

12.50% |

3 |

37.50% |

| Intx |

Interacting |

7 |

100.00% |

0 |

0.00% |

1 |

14.29% |

6 |

85.71% |

| PCFish |

Playing capturing fish |

7 |

100.00% |

4 |

57.14% |

1 |

14.29% |

2 |

28.57% |

| PlayRec |

Playing instr. + recording |

7 |

100.00% |

3 |

42.86% |

4 |

57.14% |

0 |

0.00% |

| SitLap |

Sitting + in laptop |

7 |

100.00% |

3 |

42.86% |

0 |

0.00% |

4 |

57.14% |

| FeedF |

Feeding fish |

5 |

100.00% |

0 |

0.00% |

5 |

100.00% |

0 |

0.00% |

| SinCell |

Singing + recording on phone |

5 |

100.00% |

1 |

20.00% |

4 |

80.00% |

0 |

0.00% |

| QiGong |

Practicing Qi Gong |

4 |

100.00% |

3 |

75.00% |

0 |

0.00% |

1 |

25.00% |

| SitWrit |

Sitting + writing |

4 |

100.00% |

0 |

0.00% |

0 |

0.00% |

4 |

100.00% |

| SitMus |

Sitting + listening to music |

3 |

100.00% |

0 |

0.00% |

3 |

100.00% |

0 |

0.00% |

| ExpoArt |

Exposing handcraft arts |

2 |

100.00% |

0 |

0.00% |

0 |

0.00% |

2 |

100.00% |

| FeedG |

Feeding the gooses |

2 |

100.00% |

2 |

100.00% |

0 |

0.00% |

0 |

0.00% |

| SitRdio |

Sitting + listening a radio device |

3 |

100.00% |

2 |

66.67% |

1 |

33.33% |

0 |

0.00% |

| WChild |

Walking + carrying child |

2 |

100.00% |

2 |

100.00% |

0 |

0.00% |

0 |

0.00% |

| WLawn |

On non-walkable lawn |

2 |

100.00% |

0 |

0.00% |

0 |

0.00% |

2 |

100.00% |

| DRCell |

Dancing + recording on phone |

1 |

100.00% |

1 |

100.00% |

0 |

0.00% |

0 |

0.00% |

| InfJob |

Informal job |

1 |

100.00% |

0 |

0.00% |

1 |

100.00% |

0 |

0.00% |

| CRecyc |

Collecting recyclable material |

1 |

100.00% |

1 |

100.00% |

0 |

0.00% |

0 |

0.00% |

| PFeedC |

Playing to feed the cats |

1 |

100.00% |

1 |

100.00% |

0 |

0.00% |

0 |

0.00% |

| SitTab |

Sitting + reading on tablet |

1 |

100.00% |

1 |

100.00% |

0 |

0.00% |

0 |

0.00% |

| |

|

All |

|

Xujiahui |

Renmin Park |

Jing'An Park |

| |

|

Total |

% |

ST3

|

% |

ST |

% |

ST |

% |

| |

|

10,801 |

100% |

3,409 |

31.60% |

4111 |

38.10% |

3280 |

30.40% |

Table 2.

Classification of Setting Codes according to Setting Function.

Table 2.

Classification of Setting Codes according to Setting Function.

| Setting Function |

Setting Code |

| Xujiahui |

Renmin |

Jing'An |

| Walkway |

A1Way, A2RWay, A2CorrT, A2Cor1, A2Cor2, A2Cor3, A3Way1, A3Way2 |

A1Way1, A1RWay, A2Way1, A2Way2, A3Way1 |

A1Way1, A1Way2, A2Way1, A2Way2, A3Way |

| Pathway |

A1SWay1, A1SWay2, A2SWay, A2Gard, A3SWay1, A3SWay2, A3Tri1, A3Tri2, A3Tri3 |

A1SWay1-3, A1Cir, A2SWay1, A2SWay2, A3Way2, A3Way2P1, A3Way2M, A3Way2P2, A3Bridge |

A1SWay, A2SWay, A3RWay |

| Rest |