1. Introduction

Depression is a major problem that is often overlooked in the older population. Alarmingly, nearly fifty percent of these cases go undiagnosed, negatively impacting the well-being of older adults [

1]. According to the World Health Organization, approximately 10 to 20% of seniors suffer from depressive disorders [

2]. Many cases go unrecognized because people are reluctant to seek help or misinterpret the symptoms as typical signs of aging. The causes of depression in older people are complex and include chronic health problems such as diabetes, heart disease, or musculoskeletal disorders, as well as social and emotional challenges such as the loss of loved ones or the transition to retirement. Depression in this population promotes feelings of powerlessness and reduces physical activity. The transition to retirement can be particularly stressful as it requires adjustment to a changed life that can affect autonomy and financial stability. The loss of family members or friends can lead to deep grief, which may result in social isolation. Symptoms such as feelings of sadness, emptiness, disinterest in previously enjoyed activities, or appetite fluctuations often go unnoticed by those affected and their support systems [

3]. The first signs of depression in older adults are often mistakenly attributed to the normal aging process or confused with other health conditions, such as dementia. Irregularities in sleep, including insomnia or excessive sleeping, are commonly regarded as normal age-related changes. The causative factors contributing to depression in older age are extensive, as is the impact on the prevalence of comorbidities. Depression may worsen the clinical presentation of chronic diseases and increase the risk of additional health complications, including cardiovascular or cerebrovascular events. Research by Frank et al. shows that depression significantly increases hospital admissions, making it a significant public health problem and an urgent socioeconomic issue [

4]. Depression impairs older people's ability to experience life satisfaction, maintain social relationships, and participate in daily activities [

5,

6]. In addition, depression in older people significantly increases the risk of suicide, and this likelihood increases with age, particularly in men [

7,

8]. Given that suicide occurs approximately every 40 seconds worldwide and the increased lethality of suicide attempts in older adults, the need to address this problem with increased urgency is becoming increasingly apparent [

9,

10]. Treatment options for depression in older people include psychotherapy, pharmacological approaches, or a combined strategy integrating different modalities, with an emphasis on tailoring therapeutic interventions to the specific needs and limitations of older people. Nonetheless, strengthening social relationships with family and friends, combined with educational programs targeting both older people and their support networks, is crucial to combat depression in older age, as it can reduce incidence rates and promote timely detection of depressive symptoms for appropriate intervention [

11,

12,

13]. Identifying the prevalence of depressive symptoms in each area is crucial as each community has unique cultural, geographic, public health, and sociological characteristics that may influence mental health.

This study examines the incidence of depression and the impact of depression on the functional abilities of geriatric rehabilitation patients in Switzerland over six years. The results may provide valuable insights into the prevalence of depression in the elderly population and potentially inform timely interventions that improve recovery and the effectiveness of such rehabilitation, which could offer significant health and socioeconomic benefits.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

The retrospective review of hospital records yielded data on 1,159 patients admitted to the geriatric department of the Lucerne Cantonal Hospital Wolhusen in Switzerland between 2015 and 2020. The exclusion criteria included people with cognitive impairment and persons who previously signed a form at the time of admission in which they objected to the use of their data. The subjects were divided into four different age groups: 65-70 years, 71-80 years, 81-90 years, and over 90 years.

2.2. Ethical Considerations

The investigation was conducted following ethical standards on an international level and received endorsement from the Ethics Committee (2020-01051). Furthermore, the research adhered rigorously to the tenets outlined in the Helsinki Declaration.

2.3. Procedure and Materials

Depression was assessed using the standardized Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS) Short Form, which was developed by Yesavage et al. to assess depressive symptoms in the geriatric population [

14,

15]. A GDS short-form score of more than 5 requires a further psychological assessment as it is indicative of depression. The GDS has shown a sensitivity of 92% and a specificity of 89% in detecting depressive symptoms. In a validation study comparing the long and short forms of the GDS, both versions were found to be highly productive in discriminating between individuals with and without depression and showed a robust correlation [

14].

The Functional Independence Measure (FIM) is used to assess disabilities with different diagnoses. It was developed by a task force sponsored by the American Academy of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation and the American Congress of Rehabilitation Medicine and published in 1987 by Keith, Granger, Hamilton, and Sherwin [

16]. The FIM assesses six functional domains using 18 items. Assessment of functional status with the FIM is based on the level of support a person requires, ranging from complete independence to complete support. A higher score indicates greater independence. The cumulative score ranges from 18 to 126, with 18 indicating complete dependence and 126 indicating complete independence. The FIM is used to assess a patient’s level of disability and to monitor changes in condition in response to rehabilitative or medical interventions [

17,

18,

19,

20].

The Tinetti test, formally known as the Performance-Oriented Mobility Assessment, assesses a person’s perception of balance and stability during activities of daily living as well as their fear of falling. It is a credible measure for assessing the risk of falling. The Tinetti test consists of two different components: an assessment of gait and an assessment of balance on a 3-point ordinal scale (0, 1, and 2). A maximum total score of 28 can be achieved, with 12 points awarded for gait and 16 points for balance. Lower scores correlate with an increased risk of falling. A score of 18 indicates a high risk of falling, scores between 19 and 23 indicate a medium risk and a score of 24 indicates a lower risk of falling [

21,

22].

2.4. Statistical Analysis

The collected data was analyzed using TIBCO Statistica 13.3, a software for the statistical analysis of data sets. The basic socio-demographic characteristics of the participants were analyzed using descriptive frequency analysis.

Assessment of the prevalence of depression in different age groups, genders, and marital statuses was performed using the χ² test, with statistical significance set at p > 0.05. The non-parametric Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used to determine the variance of FIM scores at admission and discharge.

3. Results

This study clarifies the prevalence of depressive disorders and their impact on the functional status of patients undergoing geriatric rehabilitation. The main characteristics of the subjects involved are listed in

Table 1. A total of 1,159 patients with an age of 83.1 years were included in the study. The majority of participants were female (63.6%), while male participants made up more than a third (36.4%) of the sample. A large proportion of participants (56.3%) were between 81 and 90 years old.

The majority of respondents (84.2%) came to the geriatric ward from their place of residence, while a minority (15.8%) came from care facilities. A significant proportion of respondents (47.7%) stated that they were widowed. Examination of the mean body mass index (BMI) (see

Table 2) shows that participants tended to be slightly outside the healthy weight spectrum. On average, people in the sample participated in rehabilitation for 20.2±7.1 days.

3.1. The Frequency of Depression in General in the Geriatric Population

A total of 266 respondents, i.e. 22.9% of the sample, were diagnosed with depressive symptoms. Of these individuals, 177 (66.5%) reported being female, while 89 (23.5%) were classified as male. However, the analysis revealed no statistically significant difference in the prevalence of depression according to gender (p = 0.230), as shown in

Table 3.

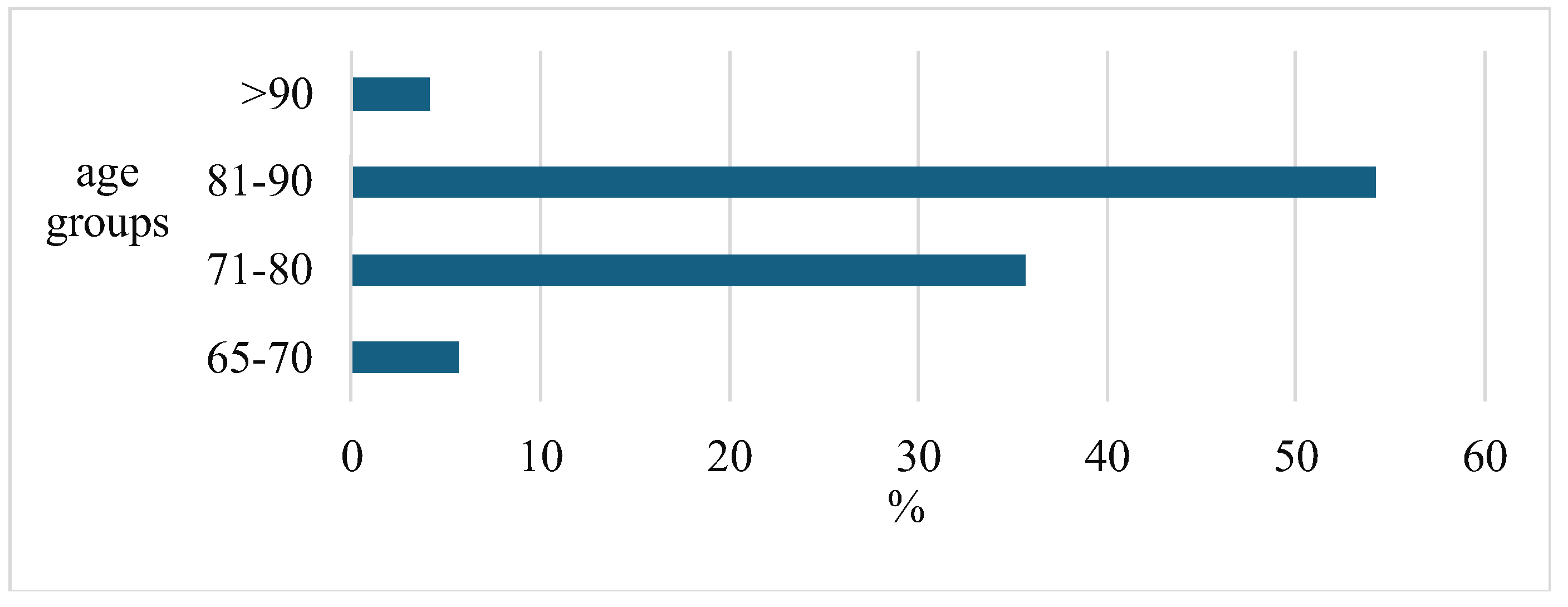

The results derived from the statistical analysis, however, indicate considerable differences in the incidence of depressive disorders in the various age cohorts: The highest incidence of depression is found in the demographic segment of 81- to 90-year-olds, while the lowest prevalence is found in the population over the age of 90 (

Figure 1).

However, no statistically significant difference was found in the prevalence of depression between women and men across different age cohorts (p=0.997).

At the same time, the analysis shows that 19.2% of people diagnosed with depression live in care facilities, while 80.8% live at home (see

Table 3). These results mean that depression is slightly, but statistically significantly (p=0.043) more common in people living in care homes than in people living at home. Furthermore, depressive symptoms are observed in about one-third (29%) of participants from nursing homes, while 22% of people living in private households show similar symptoms.

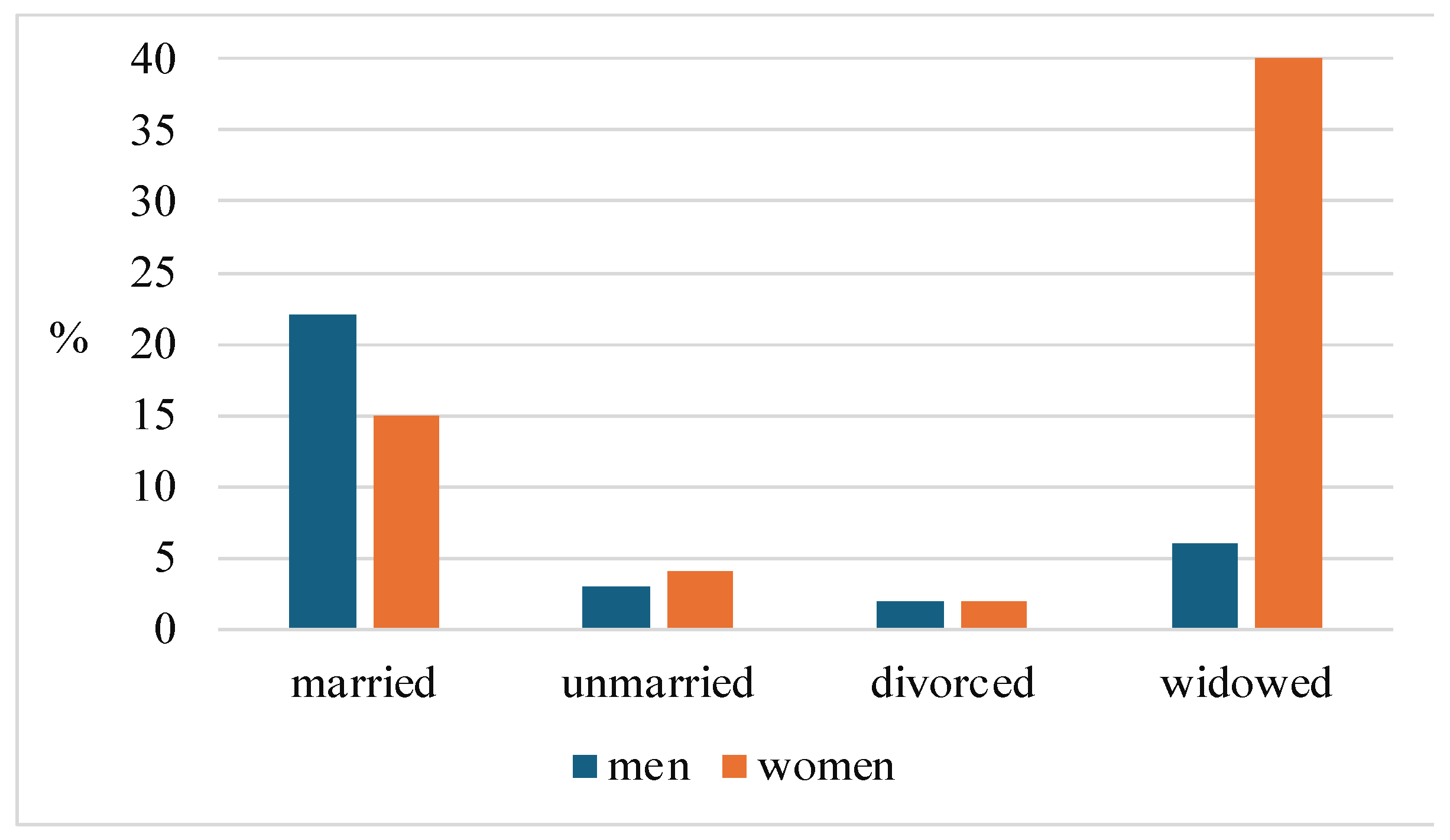

Further analysis shows that there are no significant differences between the groups in terms of depression in the categories of respondents' marital status (see

Table 3). However, when comparing depressed men and women according to marital status, it is noticeable that the female cohort contains a significantly larger proportion of widows, while the male cohort is predominantly characterized by married people (

Figure 2).

The analysis of the duration of rehabilitation in patients with depressive symptoms (N=266) compared to patients without this diagnosis (N=893) shows that the duration of rehabilitation was about two days longer in people with depression (

Table 4).

3.2. The Correlation between Depression and Functional Status

The study found that there was no significant correlation between the Functional Independence Measure (FIM) at the time of admission and the Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS). Nevertheless, a modest but statistically significant correlation was found between these two measures at the time of discharge (p = 0.043, r = -0.06). This inverse correlation implies that an improvement in functional status is associated with a reduction in GDS score, which inversely implies a reduction in depression.

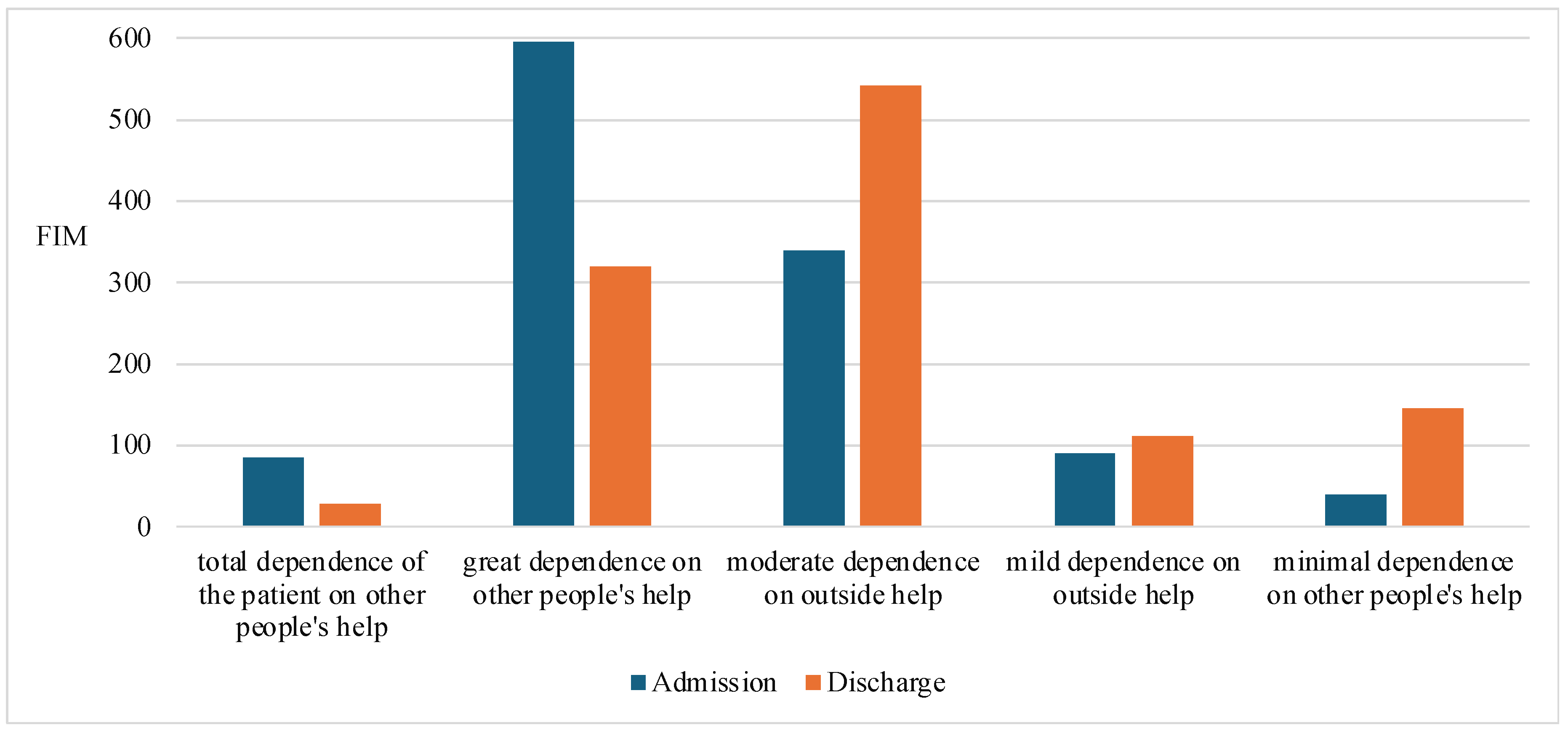

In addition, the non-parametric Wilcoxon matched-pairs test revealed a significant difference in FIM scores from admission to discharge (p < 0.001) across a variety of patient dependency classifications. Of note, individuals categorized in the first two classifications (total dependence and severe dependence on external help) showed deterioration in functional status at the time of hospital discharge, whereas those in the following three classifications (moderate, mild, and minimal dependence on external help) showed improvement in functional status at discharge (

Figure 3).

Conversely, no significant relationship (p = 0.288) was found between Functional Independence Measure (FIM) scores at admission and scores at discharge in individual patients, and there was also no correlation between FIM scores in the cohorts of depressed and non-depressed individuals. This suggests that there is no significant association between depression and functional assessment scores (p = 0.288).

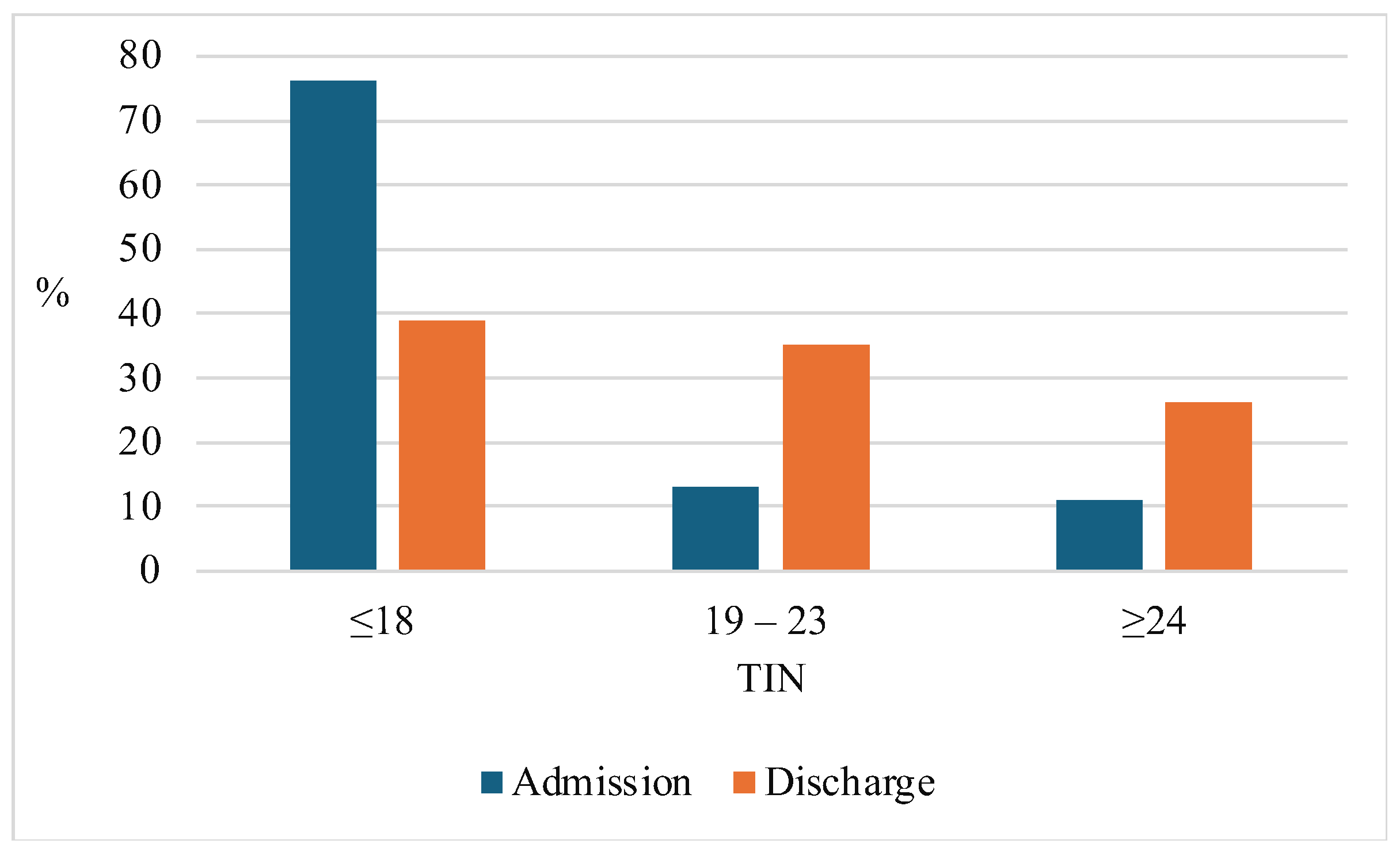

The relationship between depression and the Tinetti score was then examined, as 76% of all participants were classified as being at high risk of falling. First, a statistically significant difference was found between the Tinetti scores at admission and those at discharge (p < 0.001). As can be seen in

Figure 4, the proportion of patients who fell into the "high fall risk" category fell by fifty percent after rehabilitation.

Further analysis showed that in the subgroup of participants who had a Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS) score of 6 or higher, there was no statistically significant association between the results of the mobility test performed at the time of admission (p = 0.835) or discharge (p = 0.336) and the GDS score. This indicates that depressive symptoms do not have a measurable impact on the Tinetti score, which is used to assess the mobility abilities of older people.

Furthermore, no statistically significant difference was found in the results of the Tinetti mobility assessment between the cohorts of participants diagnosed with depression and those not diagnosed with this condition (

Table 5).

4. Discussion

Age is a crucial and highly influential dimension of the human experience. The challenges associated with aging are becoming increasingly important as societies change and technological innovation advances. The unprecedented increase in the global population of older people will accelerate in the coming decades, especially in developing countries [

23].

Today's society is faced with a complex dilemma resulting from the increasing incidence of physical and mental illness combined with the extension of life expectancy. The phenomenon of an aging population is only one facet of this problem; it is also influenced by lifestyle changes, environmental factors, and other factors [

23]. In our study, the average age of participants was 83.1 years, with an overwhelming proportion (56.3%) falling into the 81- to 90-year-old age group. The vast majority of respondents (84.2%) were referred to the geriatric unit from home, while only 15.8% were referred to assisted living facilities. This interaction raises critical questions about the support mechanisms and overall quality of life for older people in their home environment, as well as the accessibility and standard of services offered in care homes.

Depression is the second most common mental disorder in the older population. According to the World Health Organization, the overall prevalence of depression is estimated at 10-20%, which is consistent with the results of our study, in which depressive symptoms were found in 266 (22.9%) of respondents. Both mild and severe forms of depression, which are recognized as serious mental health problems in nursing home residents, affect up to 30% of this population [

24,

25]. In general, a lower incidence of depression correlates with higher economic status [

26,

27]. A meta-analysis by Zenebe et al. shows that the prevalence of depression in older people is higher in developing countries (40.78%) than in industrialized countries (17.05%) [

1]. The prevalence in older adults varies widely between studies due to differences in regional cultures and screening tools. The global prevalence of depression in older adults was 28.4%, with large heterogeneity between studies, as reported in a meta-analysis by Hu et al [

28].

Although Switzerland is one of the countries with the highest gross domestic product in the world, our study found a relatively high prevalence of depression (22.9%) in older people. More than 80% of people who show pronounced depressive symptoms come from their home environment. The importance of caring for and supporting older people in their home environment cannot be overstated. Although care homes are an alternative for some older people, most prefer to live in their own homes. It is essential to ensure that older people receive the necessary psychosocial support and care in their home environment, including regular medical check-ups, therapeutic interventions, activities to promote social engagement, and opportunities for physical activity.

Despite the seemingly different figures, the analysis shows that depression is slightly, but statistically significant (p=0.043) more common in people living in care facilities than in people living in their own homes, despite the high standards of care. Many residents face emotional and social loss when they move into a care home, which can lead to feelings of isolation and a sense of losing control of their lives. In addition, older people's mental well-being can be affected by changes in their environment, limited opportunities to actively participate in social activities, and reduced autonomy. The fundamental consideration is to address the different needs and challenges of individual residents and adapt care approaches accordingly. These include emotional support, access to activities and social contact, and the promotion of autonomy and control over one's own life. 54.2% of participants fell into the 81- to 90-year-old age group, supporting the contention that the prevalence of depression increases with age. This data highlights the need to recognize and support the older population. In the context of people living independently, these measures become even more important.

Significant discrepancies were found in the prevalence of depression with marital status. Emotional support and a sense of belonging can be fostered by a stable and nurturing marital relationship, which can reduce the risk of depression [

29]. The majority of people who showed depressive symptoms in our study were women, especially widows. The loss of a partner can cause feelings of isolation and grief, which may increase the risk of depression. Previous research by Zhou et al. has shown that middle-aged and older women are more prone to depression than their male counterparts and that middle-aged and older married individuals are less likely to suffer from depression than those who were separated, divorced, widowed, or never married [

30].

Despite the numerical differences, we find no significant variance in the frequency of depression depending on gender (p = 0.230). In the female cohort, the proportion of widows is higher, while the male cohort contains a larger number of married men.

Insterenstgly, we found a higher percentage of depressive symptoms in married men, than a single. Depression in married men may be influenced by several factors, including family expectations, marital and family stressors, economic adversity, and social conventions that prevent men from articulating their emotional weakness or seeking help. Nevertheless, these factors can also contribute to depressive symptoms in younger men. Married men are often responsible for their families, which can lead to feelings of overwhelm and diminished self-esteem as they cope with the pressures of everyday life. This is especially true for older men, whose physical and mental health deteriorates faster than their female counterparts [

31].

In terms of the impact of depression on rehabilitation outcomes, an analysis of rehabilitation duration in those diagnosed with depression found that participants with depressive symptoms took approximately two days longer to complete rehabilitation than their non-depressed counterparts. Although no significant correlation was found between FIM scores on admission and GDS scores, there was a small but statistically significant correlation at discharge (p = 0.043, r = -0.06). The negative correlation observed means that better functional status correlates with lower GDS scores, indicating lower levels of depression, and vice versa. Allen et al. demonstrated a statistically significant association between changes in FIM scores and a reduction in depressive symptoms from admission to discharge; however, no such association was observed from discharge to follow-up [

32]. Patients who had suffered a stroke or myocardial infarction showed lower efficacy of functional recovery compared to patients without depressive symptoms. This suggests that these patients should be provided with more psychological resources that include early assessment and effective interventions for depression [

33,

34].

Our study found that FIM scores showed significant differences between admission and discharge in patients categorized by level of dependence on external help (p = 0.001). However, it was found that the functional status of patients at the time of hospital discharge was worse in the first two classifications (total dependence and severe dependence on external help), while patients in the remaining three categories (moderate, mild, and minimal dependence on external help) had a better functional status when leaving the hospital. The correlation between depression and FIM score (p = 0.288) was found to be insignificant. Improving rehabilitation protocols is crucial, especially for individuals with impaired functional status who often have more acute disease manifestations. These rehabilitation protocols should be tailored to the specific needs and abilities of each individual and include a comprehensive strategy that incorporates the physical, psychological, and social dimensions of health. For individuals with low functional status, modification and expansion of the rehabilitation program may be necessary to achieve optimal results. A gradual increase in training intensity, individualized therapeutic interventions, and assistance with daily activities may be essential to achieve maximum functional independence. After discharge, people with impaired functional status are often admitted to temporary or permanent care facilities.

The effectiveness of rehabilitation measures in older people characterized by a better functional status on admission, which continues to develop during hospitalization, has been proven. People with higher functional status generally have greater autonomy and competence in performing everyday tasks, which can promote a sense of self-worth and self-actualization. Conversely, decreased functional status can limit a person’s ability to perform basic activities, leading to feelings of powerlessness and frustration, thus increasing the risk of depressive states. To ensure appropriate post-discharge care, it is important to assess the functional status of elderly patients before they return home. Adjustments to the living environment, provision of medical equipment or therapeutic interventions, and assistance with daily tasks may be required. In addition, emotional support and education are essential to ensure that individuals have the necessary resources and skills to skillfully navigate the transitions and adversities associated with returning home. By taking a comprehensive approach that considers the functional status, psychological well-being, and specific needs of each older person, exemplary care can be provided after discharge from the hospital that improves overall well-being and clinical outcomes, minimizes distress, and enhances the quality of life [

35,

36].

Finally, fall prevention is a key element of elderly care, as falls are one of the biggest challenges for older people. Such falls can lead to serious injuries such as fractures and can significantly impair the quality of life and functional ability of older people. The correlation between depressive symptoms and the Tinetti score was investigated as 76% of our subjects were classified as increased fall risk. A statistically significant difference in Tinetti score was found between the time of admission and discharge (p<0.001). The Tinetti mobility assessment showed no statistically significant differences between the cohorts of subjects with depression and those without depressive symptoms. Falls prevention involves a variety of strategies and methods, such as risk assessment, environmental adaptations, systematic physical activity, educational initiatives, and appropriate medical interventions. Together, these strategies can reduce the likelihood of falls and improve the safety and quality of life of older people. Holistic elderly care should include fall prevention measures to enable safe and independent aging.

5. Conclusions

Aging is a central part of human existence. As the population of older adults continues to grow worldwide, the phenomenon of aging is becoming increasingly important, particularly in terms of demographic change, healthcare systems, and economic viability.

Depression is a common mental health problem among older people, with prevalence rates varying according to geographical and socio-cultural factors. Support and timely interventions are essential to mitigate the impact of depression on older people's quality of life. The mental health of older people is highly influenced by their functional abilities, particularly depressive disorders. Improving functional abilities can help to reduce the likelihood of depression and improve overall well-being.

Given the potentially serious consequences that falls can have, fall prevention is of paramount importance for older people. The likelihood of falls can be effectively reduced through regular risk assessments, environmental modifications, and the promotion of physical activity, thereby increasing the safety of older people.

In summary, a comprehensive strategy that includes mental health support, functional status improvement, and fall prevention is essential to ensure quality care and improve the quality of life for older adults.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.M., and U.C..; methodology, B.M.; software, L.J..; validation, L.J.; formal analysis, L.J.; investigation, U.C.; data curation, B.M.; writing—original draft preparation, B.M., S.S.; writing—review and editing, B.M., and S.S.; supervision, S.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.”.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted following the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of Northwest and Central Switzerland (protocol code 2020-01051 from 26.05.2020).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was not obtained from patients as this was a retrospective data analysis. The study was conducted with the approval of the ethics committee and under internal hospital supervision.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the author: bojan.miletic@uniri.hr (B.M.).

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Mr. Leo Jankovic (California University of Technology, Pasadena, USA) and Matea Miletic (Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences, Rijeka, Croatia) for their collaboration and assistance in linguistically refining the articles, and utilizing artificial intelligence software to improve the readability and language of the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Zenebe, Y.; Akele, B.; W/Selassie, M.; Necho, M. Prevalence and determinants of depression among old age: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Gen Psychiatry 2021, 20, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Assembly 69. Multisectoral action for a life course approach to healthy aging: draft global strategy and plan of action on aging and health: report by the Secretariat. Available online: https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/252671 (accessed on day month year).

- Trivedi, MH. The link between depression and physical symptoms. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry 2004, 6, 12–6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Frank, P.; Batty, G.D.; Pentti, J.; Jokela, M.; Poole, L.; Ervasti, J.; Vahtera, J.; Lewis, G.; Steptoe, A.; Kivimäki, M. Association Between Depression and Physical Conditions Requiring Hospitalization. JAMA Psychiatry 2023, 80, 690–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goodwin, G.M. Depression and associated physical diseases and symptoms. Dialogues Clin Neurosci 2006, 8, 259–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, Y; Lee, JK; Kim, DH; Park, JH; Choi, M; Kim, HJ; Nam, MJ; Lee, KU; Han, K; Park, YG. Factors associated with quality of life in patients with depression: A nationwide population-based study. PLoS One 2019, 14, e0219455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obuobi-Donkor, G; Nkire, N; Agyapong, VIO. Prevalence of Major Depressive Disorder and Correlates of Thoughts of Death, Suicidal Behaviour, and Death by Suicide in the Geriatric Population-A General Review of Literature. Behav Sci. 2021, 11, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Leo, D. Late-life suicide in an aging world. Nat Aging 2022, 2, 7–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crestani, C; Masotti, V; Corradi, N; Schirripa, ML; Cecchi, R. Suicide in the elderly: a 37-years retrospective study. Acta Biomed 2019, 90, 68–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minayo, MCS; Figueiredo, AEB; Mangas, RMDN. Study of scientific publications (2002-2017) on suicidal ideation, suicide attempts and self-neglect of elderly people hospitalized in Long-Term Care Establishments. Cien Saude Colet 2019, 24, 1393–1404. [CrossRef]

- Kok, RM; Reynolds, CF 3rd. Management of Depression in Older Adults: A Review. JAMA 2017, 317, 2114–2122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casey, DA. Depression in Older Adults: A Treatable Medical Condition. Prim Care 2017, 44, 499–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steffens, DC. Treatment-Resistant Depression in Older Adults. N Engl J Med 2024, 390, 630–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yesavage, JA; Brink, TL; Rose, TL; Lum, O; Huang, V; Adey, M; Leirer, VO. Development and validation of a geriatric depression screening scale: a preliminary report. J Psychiatr Res 1982, 17, 37–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krishnamoorthy, Y; Rajaa, S; Rehman, T. Diagnostic accuracy of various forms of geriatric depression scale for screening of depression among older adults: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Gerontol Geriatr 2020, 87, 104002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keith, RA; Granger, CV; Hamilton, BB; Sherwin, FS. The functional independence measure: a new tool for rehabilitation. Adv Clin Rehabil 1987, 1, 6–18. [Google Scholar]

- Linacre, JM; Heinemann, AW; Wright, BD; Granger, CV; Hamilton, BB. The structure and stability of the Functional Independence Measure. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1994, 75, 127–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grimby, G; Gudjonsson, G; Rodhe, M; Sunnerhagen, KS; Sundh, V; Ostensson, ML. The functional independence measure in Sweden: experience for outcome measurement in rehabilitation medicine. Scand J Rehabil Med 1996, 28, 51–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernandes, S; Bula, C; Krief, H; Carron, PN; Seematter-Bagnoud, L. Unplanned transfer to acute care during inpatient geriatric rehabilitation: incidence, risk factors, and associated short-term outcomes. BMC Geriatr 2024, 24, 456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morandi, A; Bellelli, G; Vasilevskis, EE; Turco, R; Guerini, F; Torpilliesi, T; Speciale, S; Emiliani, V; Gentile, S; Schnelle, J; et al. Predictors of rehospitalization among elderly patients admitted to a rehabilitation hospital: the role of polypharmacy, functional status, and length of stay. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2013, 14, 761–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borowicz, A; Zasadzka, E; Gaczkowska, A; Gawłowska, O; Pawlaczyk, M. Assessing gait and balance impairment in elderly residents of nursing homes. J Phys Ther Sci 2016, 28, 2486–2490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scura, D.; Munakomi, S. Tinetti Gait and Balance Test. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK578181/ (assessed on 08.07.2024).

- Li, A; Wang, D; Lin, S; Chu, M; Huang, S; Lee, CY; Chiang, YC. Depression and Life Satisfaction Among Middle-Aged and Older Adults: Mediation Effect of Functional Disability. Front Psychol 2021, 12, 755220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tesky, VA; Schall, A; Schulze, U; Stangier, U; Oswald, F; Knopf, M; König, J; Blettner, M; Arens, E; Pantel, J. Depression in the nursing home: a cluster-randomized stepped-wedge study to probe the effectiveness of a novel case management approach to improve treatment (the DAVOS project). Trials 2019, 20, 424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matos Queirós, A; von Gunten, A; Martins, M; Wellens, NIH; Verloo, H. The Forgotten Psychopathology of Depressed Long-Term Care Facility Residents: A Call for Evidence-Based Practice. Dement Geriatr Cogn Dis Extra 2021, 11, 38–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, S; Gao, L; Liu, F; Tian, W; Jin, Y; Zheng, ZJ. Socioeconomic status and depressive symptoms in older people with the mediation role of social support: A population-based longitudinal study. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2021; 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, Y; Lu, J; Zheng, X; Zhang, J; Lin, H; Qin, Z; Zhang, C. The relationship between socioeconomic status and depression among the older adults: The mediating role of health promoting lifestyle. J Affect Disord 2021, 285, 22–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, T; Zhao, X; Wu, M; Li, Z; Luo, L; Yang, C; Yang, F. Prevalence of depression in older adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res. Prevalence of depression in older adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res 2022, 311, 2022; 311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulloch, AGM; Williams, JVA; Lavorato, DH; Patten, SB. The depression and marital status relationship is modified by both age and gender. J Affect Disord 2017, 223, 65–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L; Zhang, K; Gao, Y; Jia, Z; Han, S. The relationship between gender, marital status and depression among Chinese middle-aged and older people: Mediation by subjective well-being and moderation by degree of digitization. Front Psychol 2022, 13, 923597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nair, S; Sawant, N; Thippeswamy, H; Desai, G. Gender Issues in the Care of Elderly: A Narrative Review. Indian J Psychol Med 2021, 43, S48–S52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, BP; Agha, Z; Duthie, EH Jr; Layde, PM. Minor depression and rehabilitation outcome for older adults in subacute care. J Behav Health Serv Res 2004, 31, 189–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wada, Y; Otaka, Y; Yoshida, T; Takekoshi, K; Takenaka, R; Senju, Y; Maeda, H; Shibata, S; Kishi, T; Hirano, S. Effect of Post-stroke Depression on Functional Outcomes of Patients With Stroke in the Rehabilitation Ward: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Arch Rehabil Res Clin Transl. 2023; 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, L; Li, L; Liu, W; Yang, J; Wang, Q; Shi, L; Luo, M. Prevalence of depression in myocardial infarction: A PRISMA-compliant meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore). 2019; 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinquart, M; Duberstein, PR. Depression and cancer mortality: a meta-analysis. Psychol Med 2010, 40, 1797–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mössinger, H; Kostev, K. Depression Is Associated with an Increased Risk of Subsequent Cancer Diagnosis: A Retrospective Cohort Study with 235,404 Patients. Brain Sci 2023, 13, 302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).