1. Introduction

Communication allows individuals to share messages, ideas, meanings, and feelings that influence each other’s behaviors and elicit specific responses according to their social imaginaries, thus ensuring coexistence [

1]. In the health context, communication is crucial because it conditions the outcome of the health–disease process [

2]. Particularly, patient-centered therapeutic communication—a growing approach in health care—is essential for appropriate care quality, increased satisfaction [

3], and better health outcomes [

4].

Communication skills help nursing professionals establish and keep quality therapeutic communication with patients and their families, focusing on improving their biological, emotional, and social well-being [

5]. These skills are relevant to build a nurse–patient therapeutic relationship and provide comprehensive care, thereby guaranteeing patient safety [

3,

4].

Concerning psychometric instruments, some studies have validated scales to measure nurse–patient communication as a competency. A study conducted in Mexico validated a scale that identifies communication behaviors from the patients’ perspective [

6], but measuring only two factors: empathy and respect. In contrast, the Interpersonal Communication Assessment Scale (ICAS) developed in the United States assesses three factors: advocacy, therapeutic use of self y validation [

7]. Since then, the ICAS has been validated in other countries such as Spain [

8].

Most of the nurse–patient communication scales have been based on patient-centered humanistic approaches [

9]. Along these lines, the Communication Skills Scale (CSS) was designed in Spain for nursing professionals to self-assess their communication and social skills when they interact with individuals who need health care. Thus, the CSS contributes to achieving specific diagnoses of reality and identifying opportunities for improvement (4). Therefore, it has been used in studies that have identified the relationship between communication skills with the burnout syndrome [

10], job satisfaction [

11], self-efficacy [

4], and job insecurity [

12,

13].

Furthermore, job insecurity—defined as the perceived fear of unemployment—is considered as a stressor agent of a worrying job situation [

14]. During the COVID-19 pandemic, a study conducted in Peru validated a scale that measures this construct as the degree of concern related to the possibility of not being able to keep a job in the future [

15]. The factors that have an impact on the perception of this fear include social aspects of work, social relationships within organizations, connection to meaningful work, indirect problems with family [

16], perception of health risks, and negative economic consequences [

17]. This construct has gained relevance because moderate levels of job insecurity can motivate nurses to adopt constructive behaviors, resulting in successful coping [

18]. However, job insecurity can unfavorably impact the efficiency and efficacy of the organization [

14], health, and well-being [

17]. In this regard, mental health issues, such as stress, anxiety, and depression, aggravated over the course of the pandemic in Peru [

19].

Studies that develop and validate communication skills scales in Peru have not been found, but there are studies that apply the CSS to Peruvian nurses [

20], without properly adapting the scale to the culture. We consider that the CSS objectively assesses the communication skills of nursing professionals in the clinical environment during their interaction with patients, based on a patient-centered model. Therefore, it could be useful to identify areas of improvement in the communication skills of Peruvian nursing professionals and thus improve care quality. In addition, since a study conducted in Peru during the COVID-19 pandemic found that a third of interviewees reported job insecurity [

19], we decided to analyze the psychometric properties of the CSS among Peruvian nurses and explore its association with job insecurity in times of crisis.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Type of Study, Sample and Procedures

This psychometric study consisted of three phases. The first one was the cultural adaptation of the CSS to the Peruvian context. The second one consisted in determining the psychometric properties of the CSS and its subscales by generating five models of confirmatory factor analysis (CFA). The third one entailed the verification of the criterion validity of the scale by exploring its connection with job insecurity during the COVID-19 pandemic.

We expected to obtain a root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) for the CFA of less than 0.08 with the probability of making a type I error equal to 0.05 and a statistical power of at least 80%. Therefore, the minimum necessary sample size was 113 participants. However, considering our non-probability sampling strategy, we gathered 225 participants.

We included nursing professionals working in primary healthcare facilities or hospitals in Peru and having access to electronic devices. We excluded nurses residing in other countries.

2.2. Measurement Tools and Processes

The Communication Skills Scale

The original CSS was developed and validated for Spanish nurses by Leal-Costa et al. [

4]. Its model has adequate goodness-of-fit indexes [χ²(128) = 213.17; p < 0.001; χ²/df = 1.665; RMSEA = 0.053 (90% CI: 0.040 - 0.065); standardized root mean square residual (SRMR) = 0.048; Tucker–Lewis index (TLI) = 0.938; comparative fit index (CFI) = 0.949; incremental fit index = 0.949]. In addition, the scale is optimally reliable (α = 0.88) and was externally validated with self-efficacy scales. The CSS is a Likert scale whose response options range from 1 = almost never to 6 = very frequently. It comprises 18 items grouped into four subscales: empathy, communication, respect, and social skills.

Cultural Adaptation Process

Since we did not find studies exploring the psychometric properties of the CSS with Peruvian nurses, we firstly submitted the scale to a cultural adaptation process through a virtual focus group. In that way, we examined the cultural relevance of the items, identified equivocal or culturally unsuitable terms, obtained feedback on the clarity and understandability of the questions, and discussed possible alternatives or modifications to adapt the scale to the Peruvian context [

21]. The focus group was made up of ten nurses from different regions of Peru who were studying their last subspecialty year in a Peruvian university (intensive care, emergencies and disasters, public health, nephrology, and others).

The focus group interview was conducted via Zoom version 6.0 because in 2021 there were still restrictions in Peru on in-person meetings due to the COVID-19 pandemic. The session was carried out according to the focus group guide prepared by the research team. The moderator (main researcher of this study) and the facilitator (nurse experienced in conducting focus group interviews) interacted with the participants for one hour and a half. At the beginning of the session, the participants provided verbal informed consent and authorization to record. Then, the researchers explained the purpose of the meeting and the theoretical model supporting the scale and its dimensions. Subsequently, discussion of each item of the CSS was encouraged, focusing on clarity, relevance, and cultural appropriateness. The participants were also asked to explain what they understood by the terms considered in the questions and to identify words or expressions that might be problematic or confusing in the Peruvian context. Finally, participants suggested to improve the wording or content of the items and include two items in the respect subscale because, unlike the other subscales, it only had three items. Therefore, we reworded 12 items (see

Supplementary Material 1) and added one item to the respect subscale [19. Escucho a mis pacientes sin prejuicios, independientemente de mis creencias (19. I listen to my patients without prejudices, regardless of my beliefs)] and one item to the social skills subscale [20. Al interactuar con los pacientes/familiares en situación de crisis, busco regular emociones y resolver conflictos (20. When interacting with patients/relatives in crisis, I try to regulate emotions and resolve conflicts)].

The Perceived Job Insecurity Scale (LABOR-PE-COVID-19)

This scale was validated for Peruvian population by Mamani et al. in 2020 [

15]. Its content validity was confirmed through expert judgment (all items reported an Aiken’s V coefficient for EFA > 0.70) and its goodness-of-fit indexes were appropriate for the Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) model [Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin = 0.780 and Bartlett’s test (654.24; df = 6; p < 0.001)]. This unifactorial scale comprises four items with response options ranging from 1 = strongly disagree to 4 = strongly agree. The reliability analysis performed with the data collected in this study indicated a McDonald’s omega value of 0.88, a high level of reliability.

In addition to communication and its dimensions, the possible factors associated with job insecurity included sex, age, place of work, contract type, remote work, history of COVID-19 infection, and job satisfaction. This last factor was assessed with the question: En general, ¿cómo calificarías tu nivel de satisfacción con tu trabajo o centro laboral? (Overall, how would you rate your level of satisfaction with your job or place of work?).

For the psychometric phase of the study—carried out between March 2021 and September 2022—we collected data by means of a Google Forms survey. We distributed the survey through WhatsApp groups made up of nurses working in healthcare facilities and graduate nursing students enrolled in public universities.

2.3. Analysis

We initially carried out a series of exploratory and descriptive analyses for each of the variables in the sample. Subsequently, since the original scale had an adequate theoretical construct, we determined whether the factor structure of the CSS had an adequate fit. To that end, we estimated five CFA models, of which four were for each of the communication subscales and one was for the whole scale. Given the ordinal nature of the items of the instrument, we used the weighted least squares mean and variance (WLSMV) estimator. A model is considered to have a good fit when it has a non-significant chi-square or when the CFI and TLI (relative fit indicators) are greater than 0.95. Likewise, the RMSEA must be less than 0.05 and the SRMR must be less than 0.08. To determine the reliability of the scale and subscales, once their factor models were estimated, we calculated the McDonald’s omega index for each model.

Finally, to determine the criterion validity of the instrument, we estimated multiple regression models to predict job insecurity. For such estimation, we employed a stepwise selection algorithm, which allowed us to estimate the model with the highest predictive capacity from the input variables. For the first model, we included the following variables: sex, marital status, place of work, contract type, job satisfaction, remote work, history of COVID-19 infection, COVID-19 patient care, age, and overall communication. For the second model, we replaced overall communication by the four subscales to avoid multicollinearity problems in the model estimation. We checked the assumptions of all models for normality of residuals, homogeneity of variances, multicollinearity, and outliers. We carried out all statistical analyses in R v4.2.1 [

22].

3. Results

A total of 225 nurses completed the survey, of which 93.3% were women. The mean age was 37 years (SD = 11.25). Overall, 58.8% of the participants reported being single, while 36.1% were married, 4.3% were separated, and 0.8% were widowed. Regarding professional characteristics, the respondents reported a mean time of work experience of 10.29 years (SD = 11.01). As for place of work, 56.9% of the nurses reported working in a hospital, 23.1% in a healthcare center, 7.1% in a polyclinic, and 12.9% in another type of healthcare facility. According to the contract type reported by the participants, 53.3% had a temporary administrative service contract; 25.5%, a tenured-employee contract; 7.5%, a permanent contract; 6.3%, a fixed-term contract; and 7.4%, a fee-for-service contract. Most of the respondents (85.1%) were working in person at the time of the assessment. In addition, 61.9% felt satisfied with their job, 32.2% felt neither satisfied nor dissatisfied, and 5.9% felt dissatisfied. Finally, 50.9% of the nurses reported not having history of COVID-19 infection.

Description of the psychometric properties of the Communication Skills Scale

Table 1 shows the descriptive statistics for each of the items of the CSS. Particularly, the highest mean was for item 18 (M = 4.75, SD = 1.10), while the lowest mean was for item 16 (M = 3.87, SD = 1.09).

Given the ordinal nature of the items, we were able to identify when estimating the WLSMV that items 16 and 18 did not have significant factor loadings in their respective scales or in the complete factor model. As a result, we decided to remove them from the analysis, leaving the CSS with 18 items (see

Supplementary Material 2).

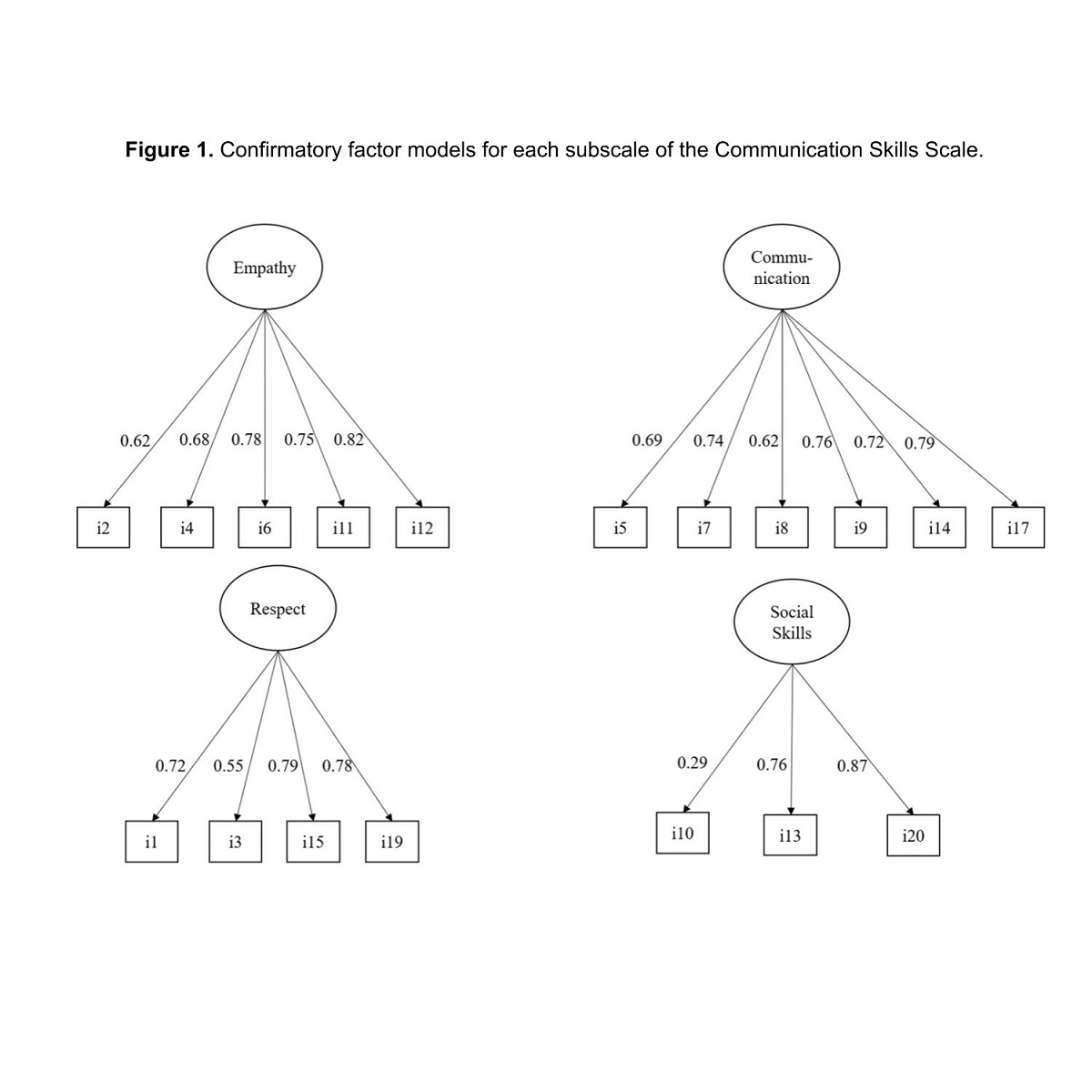

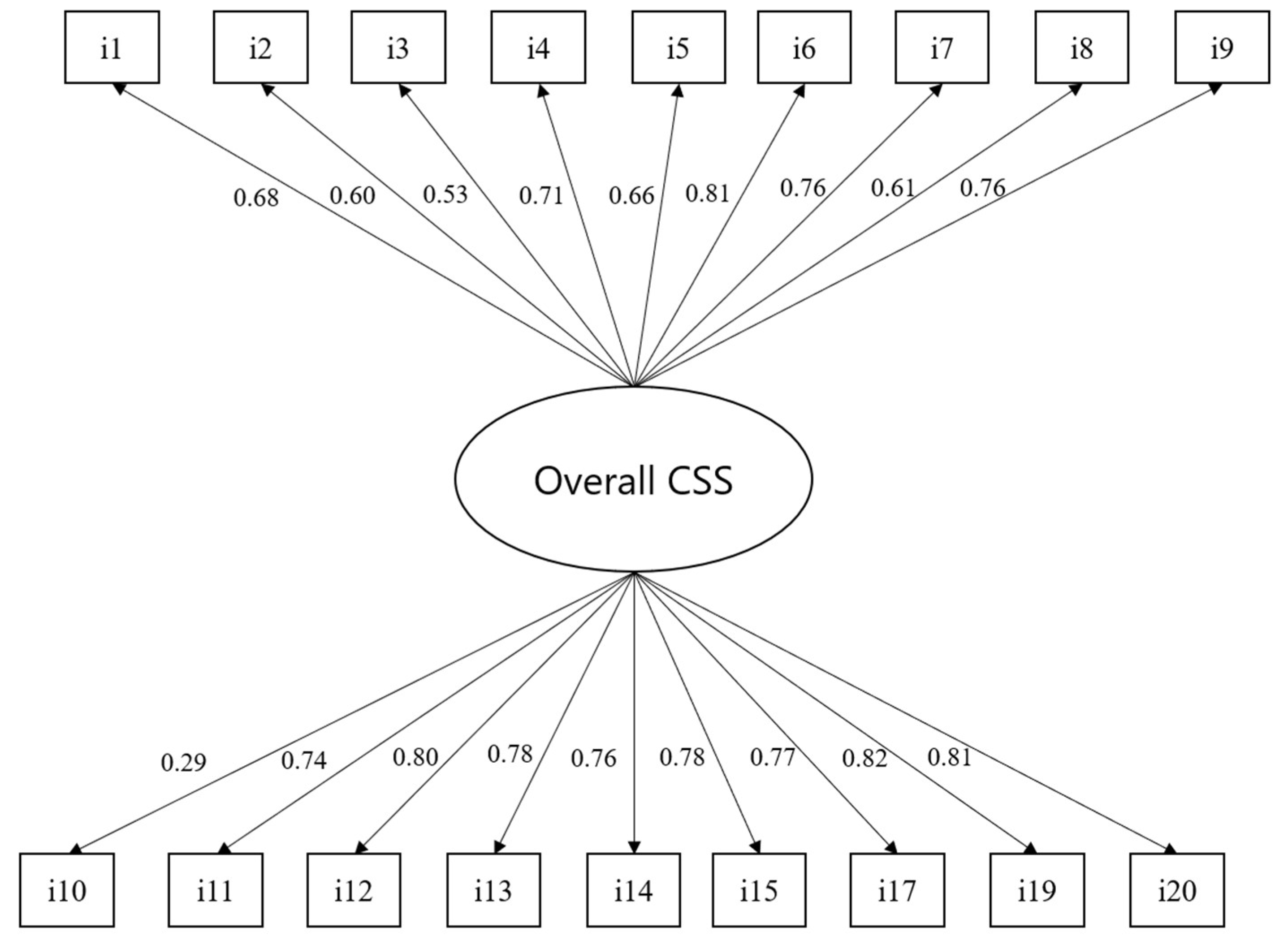

Figure 1 shows the four confirmatory models estimated for each subscale. We found that all the models achieved an adequate level of fit. For the empathy subscale model, we obtained a non-significant chi-square index (X2 = 6.82, df = 5, p = 0.24), which indicated a good fit of the model. We observed a similar scenario with the confirmatory model for the communication subscale, which also showed a non-significant chi-square index (X2 = 4.09, df = 9, p = 0.91). The model for the respect subscale also obtained a non-significant chi-square index (X2 = 5.04, df = 2, p = 0.08). Lastly, in the confirmatory model for social skills, we identified a significant chi-square index (X2 = 104.55, df = 3, p < 0.001), suggesting that this model does not have a good fit in absolute terms. However, the relative fit indicators of this model revealed that its level of fit was adequate (CFI = 1, TLI = 1, RMSEA = 0.00, SRMR = 0.00).

All the factor loadings of the models were statistically significant (p < 0.001). Notably, all the loadings for empathy were greater than 0.62, confirming that the subscale is highly reliable. A subsequent analysis estimated the McDonald’s omega index for this subscale, resulting in a value of 0.82 and confirming also the high reliability of the subscale. Similarly, all the factor loadings for the communication subscale were above 0.62, obtaining a McDonald’s omega index of 0.84. These two values indicate a high reliability of the subscale. Furthermore, it was observed that item 3 of the respect subscale had a factor load of 0.55, which was the lowest in the model, and the McDonald’s omega index of this subscale was 0.77. These indicators suggest an adequate fit of the subscale. Finally, the social skills model showed that item 10 had a value of 0.29, which is considered low, although still significant. The McDonald’s omega index for this subscale was 0.60, indicating an acceptable level of reliability. In summary, the empathy and communication subscales obtained the highest levels of reliability, while the social skills subscale received the lowest.

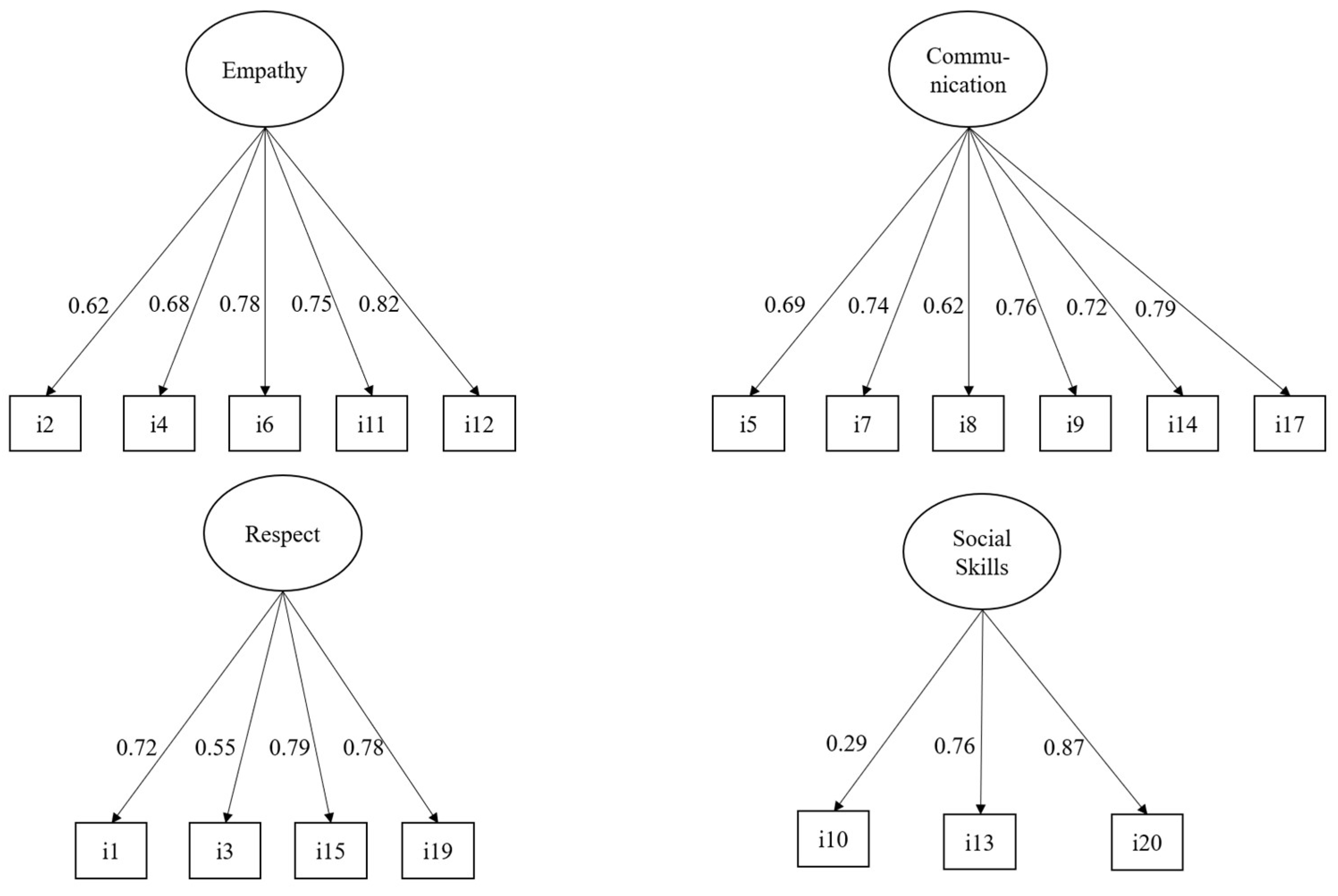

Figure 2 shows the overall confirmatory model for the CSS. The scale has a good absolute fit according to the chi-square index (X2 = 84.44, df = 135, p = 1.00), indicating a correct factor structure. All the factor loadings of the model were statistically significant (p < 0.001) and most of them had scores above 0.60. Only items 3 and 10 had factor loadings of 0.53 and 0.29, respectively, which are low but still significant. Finally, the McDonald’s omega index for the scale was 0.94, indicating excellent reliability.

Table 2 shows the first stepwise regression model that we used to predict job insecurity scores from the participants’ sociodemographic variables and the entire CSS. For this model, the variables included in the selection algorithm were contract type, overall communication, and job satisfaction. Regarding the contract type, the participants with a temporary administrative service contract had a higher perception of insecurity than those with a tenured-employee contract (b = 0.84, p < 0.001). This difference is considered to be strong according to the standardized regression coefficient (B = 0.53). In addition, the participants with a fixed-term contract also reported higher scores in job insecurity than those with a tenured-employee contract (b = 0.56, p < 0.01). Nevertheless, this difference is mild according to the standardized regression coefficient (B = 0.17).

Lastly, the participants with a fee-for-service contract perceived greater job insecurity than those with a tenured-employee contract (b = 0.84, p < 0.001). This difference is moderate according to the standardized regression coefficient (B = 0.28). Concerning the levels of communication, we found that higher scores on the CSS were connected with lower scores on job insecurity (b = −0.01, p < 0.01). This effect is mild according to the standardized regression coefficient (B = −0.17). As for job satisfaction, the participants who felt dissatisfied also reported higher levels of job insecurity than those who felt satisfied (b = 0.40, p < 0.05). This difference is mild according to the standardized regression coefficient (B = 0.12). Lastly, when observing the overall fit of the model, we found that all the variables included accounted for 25% of the total variability of job insecurity (adjusted R² = 0.25, p < 0.01).

Table 3 shows the stepwise regression model that we employed to predict the participants’ levels of job insecurity. For this model, we took the sociodemographic variables of the participants as predictors and used the subscales of the CSS separately to identify which subscales were most related to job insecurity. The stepwise selection algorithm identified that the variables that significantly contributed to explaining the variance of job insecurity were contract type, the empathy subscale, and job satisfaction. Regarding the contract type, the results were very similar to those presented in

Table 2, that is, the participants with temporary administrative service contracts, fixed-term contracts, and fee-for-service contracts had higher levels of job insecurity than those with tenured-employee contracts.

Moreover, the algorithm only chose the empathy subscale for the present model, showing that higher scores in empathy were associated with lower levels of job insecurity (b = −0.04, p < 0.01). This effect is considered mild according to the standardized regression coefficient (B = −0.18). No other subscales were chosen by the algorithm. Similarly, the participants with higher levels of job dissatisfaction scored higher on the job insecurity scale than satisfied participants. This model had a 26% explained variance in the response variable (adjusted R² = 0.26, p < 0.001).

4. Discussion

Based on a CFA, this study reports that the CSS applied to a sample of Peruvian nurses has a similar internal structure to the original questionnaire developed in Spain [

4]. Furthermore, this study shows that the CSS has excellent reliability (ω = 0.094), proving that the psychometric properties of the scale are suitable to the Peruvian context. In addition, the scale has criterion validity because its association with job dissatisfaction was confirmed. Similarly, an adequate fit was found for each of the confirmatory models estimated for the different subscales of this construct (communication skills), revealing that the subscales can be applied independently if necessary. It is worth noting that the social skills subscale showed an acceptable level of reliability (ω = 0.60), but lower than that found in the other subscales. This finding is in line with another psychometric study that validated the CSS for health professionals [

23]. The reason behind this result could be the small number of items in this subscale compared to the other subscales.

The cultural adaptation of the CSS for its application to Peruvian nurses proved to be a crucial step in our study. This process made it possible to pinpoint and address subtle but significant linguistic and cultural differences, thereby improving the content validity and conceptual equivalence of the instrument in Peru [

24]. Conducting the focus group interview according to the recommendations by Squires et al. [

25] entailed an in-depth exploration of the relevance and understandability of the items. Moreover, the perspective of the experienced professionals in the focus group was crucial considering that they were pursuing their subspecialty studies. This participatory approach not only enriched the instrument with specific cultural perspectives, but also potentially increased its acceptability among the target population, which is essential for its effective implementation in clinical practice [

26].

Regarding the analysis of criterion validity, this study evidences the existence of an indirect relationship between the communication score and job insecurity among nursing professionals during the COVID-19 pandemic. This finding is consistent with a study conducted in the United States during the early outbreaks of the pandemic. It found that effective and frequent organizational communication was crucial in mitigating job insecurity and improving employee well-being in times of crisis [

13]. Other study from Belgium found a negative association between organizational communication and job insecurity [

12].

This could mean that clear communication with employees concerning their expectations is key in the development of organizational commitment and the employee–organization relationship [

14]. Thus, organizational measures, such as establishing efficient communication channels, fostering a supportive climate, and adjusting the organizational practices and policies, indirectly mitigate the stressing nature of job insecurity among employees [

27], strengthening their commitment to the organization.

Unexpectedly, as we did not find previous reports in the literature, the score for the empathy subscale was a predictor of job insecurity. A couple of reasons behind this could be that empathy is one of the factors that mitigate exhaustion in health staff and is a unique psychological means having an impact not only on them but also on patients [

28]. Alignment with institutional objectives allows employees to better understand the aspects involved in achieving them, leading them to strengthen their work commitment and improve their job performance [

29].

One finding across all the regression models performed was the indirect association of job satisfaction with job insecurity. This result coincides with a study conducted in the United States, South Africa, and Croatia, reporting that there is an inverse relationship between both variables [

30]. Nevertheless, a study carried out with workers of a mining company in Indonesia pointed out that job insecurity had a positive effect on job satisfaction [

31]. The authors of such study explain that, under certain conditions, job insecurity could motivate workers to see the positive side of their work as a way of adapting to uncertainty.

In contrast, other study highlighted that stress, and not the working conditions and job insecurity, impacts nursing professionals’ job satisfaction [

32]. In addition, another finding of the present study was that unstable contracts are connected with job insecurity, which confirms previous results showing that temporary contracts weaken the quality of life and increase job insecurity among nurses [

33]. This is linked to research establishing positive relationships between job and life satisfaction among professionals in the nursing field [

34]. Therefore, although the evidence from this study supports the indirect relationship between the two variables, further research is needed to elucidate the connection of these variables with intervening variables, such as working conditions, mental health issues, and motivation, in other contexts.

From a theoretical perspective, this study is a significant advance in the understanding of the CSS in the specific Peruvian cultural context. Particularly, this contribution is valuable considering the lack of validated scales measuring this construct in Peru. Furthermore, exploring the relationship of this scale with other variables in future studies may be the opportunity to identify unique aspects of communication in the nursing profession. Cultural, socioeconomic, and health system factors may play a pivotal role in these investigations. This scale can also facilitate the assessment of communication skills training programs, allowing for a more accurate alignment between theory and practice in the Peruvian environment.

The practical implications of this study are substantial for human resource management in nursing. The proven association of job dissatisfaction with factors such as communication, empathy, contract type, and job satisfaction encourage multidimensional interventions. This study underlines the importance of healthcare institutions implementing training programs in communication skills and empathy, while also offering more stable contracts and improving working conditions with recognition programs and professional development opportunities. In this way, the health staff will have a better quality of life, favorably impacting institutional indicators and improving the quality of patient care.

We identified four limitations in this study that are worth noting. First, since we relied solely on the existing theoretical framework for the factor structure, we may have overlooked specific cultural or contextual aspects that could affect the structure of the CSS in the study population. While this theoretical model is widely used across various contexts, we implemented a thorough process of cultural adaptation to counteract this bias. Second, given that we used a non-probability sampling, caution is advised when applying the results of this study to different demographic or cultural groups. Third, we did not perform a factor invariance analysis because due to a considerable imbalance in the sex dimension, with women representing 93.3% of the participants. This limits the ability to determine whether the reported factor structure is consistent across different sex subgroups. Lastly, the self-reporting of the CSS without direct observation of behaviors may have limited the accuracy of measurement, as the skills assessed are complex and often manifest in face-to-face interactions. In addition, being based solely on self-reports through an online form due to COVID-19 pandemic restrictions, the study may be subject to biases of self-perception and social desirability, which could affect the results. Nevertheless, during the collection process, participants were informed about the importance of the study and assured of the confidentiality of their responses.

5. Conclusions

This study analyzed the psychometric properties of the CSS among Peruvian nurses. After a process of cultural adaptation and validation, we conclude that this four-factor scale has a similar structure to the original scale. Similarly, its strong psychometric properties and adequate reliability allows for its applicability among Peruvian nurses. We can also confirm that the subscales of the CSS (empathy, respect, communication, and social skills) can be used independently.

Additionally, the regression analysis evidenced that the nurses’ perception of job insecurity during the COVID-19 pandemic may be preceded by contract type, job satisfaction, communication skills, and empathy. This supports the criterion validity of the CSS because its association with job dissatisfaction was confirmed. Lastly, we recommend further validations of this scale, considering nursing specialties or types of healthcare facility.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org: Supplementary Material 1 (Items before and after the cultural adaptation process of the communication skills scale applied to Peruvian nurses) and Supplementary Material 2 (Communication Skills Scale).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.S., J.A.Z., E.F., O.M. and Z.J.R.; methodology, J.A.Z., E.F., R.Z., I.M. and Z.J.R.; validation, G.S. and J.A.Z.; formal analysis, J.A.Z., E.F. and R.Z.; investigation, I.M. and Z.J.R.; data curation, J.A.Z. and G.S.; Resources, R.Z.; Visualization, I.M. and Z.J.R.; writing—original draft preparation, J.A.Z., G.S., and E.F.; writing—review and editing, R.Z., I.M. and Z.J.R.; project administration, G.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was financed by the authors themselves.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The Ethics and Research Committee of Universidad María Auxiliadora approved the study (Minutes No. 003-2021, date 15 March 2021). The participants provided verbal authorization in the cultural adaptation phase and completed a virtual informed consent form in the psychometric phase. To protect the privacy of the information and give the researchers exclusive access to the data, the survey data were coded to remove any identifying information. In addition, the use of the CSS in this study was authorized by Dr. César Leal-Costa, author of the original scale.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained online from all study participants.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Pereira, T.J.; Puggina, A.C. Validation of the self-assessment of communication skills and professionalism for nurses. Rev. Bras. Enferm. 2017, 70, 588–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mendoza Maldonado, Y.; Barría Pailaquilén, M. Health communication and the need for interdisciplinary integration. Rev. cuba. inf. cienc. salud. 2021, 32. Available online: https://acimed.sld.cu/index.php/acimed/article/view/1692/1129 (accessed on 29 June 2024).

- Giménez-Espert, M.D.C.; Maldonado, S.; Pinazo, D.; Prado-Gascó, V. Adaptation and Validation of the Spanish Version of the Instrument to Evaluate Nurses’ Attitudes Toward Communication With the Patient for Nursing Students. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 736809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leal-Costa, C.; Tirado González, S.; Ramos-Morcillo, A.J.; Díaz Agea, J.L.; Ruzafa-Martínez, M.; Van-der Hofstadt Román, C.J. Validation of the Communication Skills Scale in nursing professionals. An. Sist. Sanit. Navar. 2019, 42, 291–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Granados-Gámez, G.; Sáez-Ruiz, I.M.; Márquez-Hernández, V.V.; Rodríguez-García, M.C.; Aguilera-Manrique, G.; Cibanal-Juan, M.L.; Gutiérrez-Puertas, L. Development and validation of the questionnaire to analyze the communication of nurses in nurse-patie nt therapeutic communication. Patient. Educ. Couns. 2022, 105, 145–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müggenburg, C.; Robles, R.; Valencia, A.; Hernández Guillén, M.D.C.; Olvera, S.; Riveros Rosas, A. Evaluación de la percepción de pacientes sobre el comportamiento de comunicación del personal de enfermería: diseño y validación en población mexicana. Salud mental 2015, 38, 273–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klakovich, M.D.; De la Cruz, F.A. Validating the Interpersonal Communication Assessment Scale. J. Prof. Nurs. 2006, 22, 60–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascual Fernández, M.C.; Ignacio Cerro, M.C.; Cervantes Estevez, L.; Moro Tejedor, M.N.; Medina Torres, M.; García Pozo, A. Comunicación de las enfermeras con los pacientes. Validación de la escala «Interpersonal Communication Assessment Scale» (ICAS). Index de Enfermería 2019, 28, 209–213. Available online: https://ciberindex.com/index.php/ie/article/view/e12381a (accessed on 29 June 2024).

- Granados-Gámez, G.; Sáez-Ruiz, I.M.; Márquez-Hernández, V.V.; Ybarra-Sagarduy, J.L.; Aguilera-Manrique, G.; Gutiérrez-Puertas, L. Systematic review of measurement properties of self-reported instruments for evaluating therapeutic communication. West. J. Nurs. Res. 2021, 43, 791–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leal-Costa, C.; Díaz-Agea, J.L.; Tirado-González, S.; Rodríguez-Marín, J.; van-der Hofstadt, C.J. Communication skills: a preventive factor in Burnout syndrome in health professionals. An. Sist. Sanit. Navar. 2015, 38, 213–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leal-Costa, C.; Tirado-González, S.; van-der Hofstadt, C.J.; Rodríguez-Marín, J. Creation of the communication skills scale in health professionals, CSS-HP. Anales de Psicología 2016, 32, 49–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vander Elst, T.; Baillien, E.; De Cuyper, N.; De Witte, H. The role of organizational communication and participation in reducing job insecurity and its negative association with work-related well-being. Economic and Industrial Democracy. 2010, 31, 249–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, I.M.; Keith, M.G.; Gallagher, C.M. Informational Justice, Organizational Communication, and Job Insecurity in the Early Stages of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Journal of Personnel Psychology 2024, 23, 23–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López Bohle, S.A.; Chambel, M.J.; Muñoz Medina, F.; Silva Da Cunha, B. The role of perceived organizational support in job insecurity and performance. Rev. Adm. Empres. 2018, 58, 393–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamani-Benito, Ó.; Apaza Tarqui, E.E.; Carranza Esteban, R.F.; Rodríguez-Alarcón, J.F.; Mejía, C.R. Inseguridad laboral en el empleo percibida ante el impacto del COVID-19: validación de un instrumento en trabajadores peruanos (LABOR-PE-COVID-19). Rev. Asoc. Esp. Espec. Med. Trab. 2020, 29, 184–193. Available online: http://www.aeemt.com/Revista_AEEMT_NF/VOL_29_N03_2020_SEP/Original%201.pdf (accessed on 29 June 2024).

- Mahmoud, A.B.; Reisel, W.D.; Fuxman, L.; Hack-Polay, D. Locus of control as a moderator of the effects of COVID-19 perceptions on job insecurity, psychosocial, organisational, and job outcomes for MENA region hospitality employees. European Management Review 2022, 19, 313–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, H.; Dhar, R.L. Job insecurity amid the COVID-19 pandemic and beyond: a systematic review and research agenda. Employee Relations 2024, 46, 1141–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Yang, C.; Zou, G. Self-esteem, job insecurity, and psychological distress among Chinese nurses. BMC Nurs. 2021, 20, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palomino-Ruiz, N.; Alvarez-Risco, A.; Guzman-Loayza, J.; Mamani-Benito, O.; Vilela-Estrada, M.A.; Serna-Alarcón, V.; Del Aguila-Arcentales, S.; Yañez, J.A.; Mejía, C.R. Job Insecurity According to the Mental Health of Workers in 25 Peruvian Cities during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Sustainability 2022, 14, 14799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huaman, N.; Morales-García, W.C.; Castillo-Blanco, R.; Saintila, J.; Huancahuire-Vega, S.; Morales-García, S.B.; Calizaya-Milla, Y.; Palacios-Fonseca, A. An Explanatory Model of Work-family Conflict and Resilience as Predictors of Job Satisfaction in Nurses: The Mediating Role of Work Engagement and Communication Skills. J. Prim. Care Community Health 2023, 14, 21501319231151380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaton, D.E.; Bombardier, C.; Guillemin, F.; Ferraz, M.B. Guidelines for the process of cross-cultural adaptation of self-report measures. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2000, 25, 3186–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. 2022. Available online: https://www.r-project.org/ (accessed on 29 July 2024).

- Leal-Costa, C.; Tirado-González, S.; Rodríguez-Marín, J.; Vander-Hofstadt-Román, C.J. Psychometric properties of the Health Professionals Communication Skills Scale (HP-CSS). Int. J. Clin. Health Psychol. 2016, 16, 76–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gjersing, L.; Caplehorn, J.R.; Clausen, T. Cross-cultural adaptation of research instruments: language, setting, time and statistical considerations. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2010, 10, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Squires, A.; Aiken, L.H.; van den Heede, K.; Sermeus, W.; Bruyneel, L.; Lindqvist, R.; Schoonhoven, L.; Stromgseng, I.; Busse, R.; Brzostek, T.; et al. A systematic survey instrument translation process for multi-country, comparative health workforce studies. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2013, 50, 264–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, V.D.; Rojjanasrirat, W. Translation, adaptation and validation of instruments or scales for use in cross-cultural health care research: a clear and user-friendly guideline. J. Eval. Clin. Pract. 2011, 17, 268–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sora, B.; Caballer, A.; Peiró, J.M. The consequences of job insecurity for employees: The moderator role of job dependence. International Labour Review 2010, 149, 59–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, Z.; Qin, Y.; Li, Y.; Wang, J.; Nicholas, S.; Maitland, E.; Cai, L. Empathy and burnout in medical staff: mediating role of job satisfaction and job commitment. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chong, S.; Van Dyne, L.; Kim, Y.J.; Oh, J.K. Drive and Direction: Empathy with Intended Targets Moderates the Proactive Personality–Job Performance Relationship via Work Engagement. Applied Psychology 2021, 70, 575–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Probst, T.M.; Tomas, J.; Roll, L.; Maslić Seršić, D.; Jiang, L.; Jenkins, M.R. Attenuating the relationship between job insecurity and job satisfaction: An examination of the role of organizational learning climate in three countries. Economic and Industrial Democracy 2023, 45, 304–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunawan, H.; Pala, R.; Tijjang, B.; Razak, M.; Qur’ani, B. Global challenges of the mining industry: Effect of job insecurity and reward on turnover intention through job satisfaction. SA Journal of Human Resource Management 2024, 22, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selan, D.A.; Abadiyah, R. Job Insecurity, Work Environment, and Job Satisfaction: An Investigation with a Mediating Role of Job Stress. Academia Open. 2024, 9, 1021070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsaouni, M.; Tripsianis, G.; Constantinidis, T.; Vadikolias, K.; Kontogiorgis, C.; Serdari, A.; Arvaniti, A.; Theodoruo, E. Assessment of quality of life, job insecurity and work ability among nurses, working either under temporary or permanent terms. Int. J. Occup. Med. Environ. Health 2024, 37, 98–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, M.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, L.; Xia, L.; Zhang, S.; Kaslow, N.J.; Liu, T.; Liu, Y.; Jiang, F.; Tang, Y.; et al. Mental health, job satisfaction, and quality of life among psychiatric nurses in China during the COVID-19 pandemic: A cross-sectional study. Clinical Epidemiology and Global Health 2024, 26, 101540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).